Abstract

Purpose

To develop a photoacoustic imaging (PAI) reporter gene that has high translational potential. Previous research has shown that human organic anion–transporting polypeptide 1b3 (OATP1B3) promotes the uptake of the near-infrared fluorescent dye indocyanine green (ICG). In this study, the authors have established OATP1B3 and ICG as a reporter gene–probe pair for in vivo PAI.

Materials and Methods

Human breast cancer cells were engineered to express OATP1B3. Control cells (not expressing OATP1B3) or OATP1B3-expressing cells were incubated with or without ICG, placed in a breast-mimicking phantom, and imaged with PAI. Control (n = 6) or OATP1B3-expressing (n = 5) cells were then implanted orthotopically into female mice. Full-spectrum PAI was performed before and 24 hours after ICG administration. One-way analysis of variance was performed, followed by Tukey posthoc multiple comparisons, to assess statistical significance.

Results

OATP1B3-expressing cells incubated with ICG exhibited a 2.7-fold increase in contrast-to-noise ratio relative to all other controls in vitro (P < .05). In mice, PAI signals after ICG administration were increased 2.3-fold in OATP1B3 tumors relative to those in controls (P < .05).

Conclusion

OATP1B3 operates as an in vivo PAI reporter gene based on its ability to promote the cellular uptake of ICG. Benefits include the human derivation of OATP1B3, combined with the use of wavelengths in the near-infrared region, high extinction coefficient, low quantum yield, and clinical approval of ICG. The authors posit that this system will be useful for localized monitoring of emerging gene- and cell-based therapies in clinical applications.

© RSNA, 2019

Keywords: Animal Studies, Molecular Imaging, Molecular Imaging-Clinical Translation, Molecular Imaging-Reporter Gene Imaging, Optical Imaging

Summary

The human organic anion–transporting polypeptide 1b3 gene can operate as a fluorescent and photoacoustic imaging reporter gene based on its ability to selectively take up indocyanine green.

Key Points

■ Imaging reporter genes can provide noninvasive measures for monitoring gene and cellular therapies in patients, but clinical reporter genes that operate on cost-effective and safe imaging modalities are currently not well established.

■ Cells engineered to synthetically express the organic anion–transporting polypeptide 1b3 transporter can take up indocyanine green (ICG) in vivo and can be detected with both fluorescent and photoacoustic imaging systems.

■ The human derivation of the organic anion–transporting polypeptide 1b3 transporter, combined with widespread clinical utility of ICG, paves a path toward potential clinical translation for this new imaging reporter gene system.

Introduction

Imaging reporter genes encode for proteins that can be used to visualize cellular and molecular processes in living systems (1). Unlike traditional contrast agents, reporter genes provide unique information on cellular viability because only living cells express the reporter. Furthermore, reporter expression can be linked to a gene of interest for dynamic tracking of its spatial and temporal expression patterns. Reporter genes have been developed for various imaging modalities, contributing extensively to monitoring the fates of various engineered cell types such as cancer, immune, and stem cells in preclinical models (2–4). Moreover, clinical studies have applied reporter genes for monitoring gene-based (5) and cell-based (6) therapies in patients with cancer by using PET. Although PET produces whole-body images with high sensitivity, it has limitations, including cost, availability, and ionizing radiation concerns for longitudinal studies. Reporter genes for affordable, portable, and safer imaging modalities are sought for continued localized monitoring of gene and cell therapies in humans.

Photoacoustic imaging (PAI), or optoacoustic imaging, detects acoustic waves from optically excited sources and is considerably more affordable than PET. On the basis of the photoacoustic effect, endogenous molecules such as deoxyhemoglobin and oxyhemoglobin can absorb light and convert a fraction of that energy into heat. This heat energy leads to a transient thermoelastic expansion, resulting in the emission of ultrasonic waves that can be detected with transducers to produce images. PAI thus combines the benefits of optical contrast with the resolution and depth detection of US. Clinical PAI systems currently provide substantial contrast at depths of several centimeters and with resolutions of a few hundred micrometers (7,8), and PAI is increasingly being applied to a growing number of biomedical applications, from sentinel lymph node imaging to vertebrae imaging for guiding spine surgery (9–11). Reporter genes for PAI would enable contrast enhancement of cell populations that would not otherwise produce PAI signals, thus potentially extending the utility of PAI for in vivo monitoring of gene-based or cell-based therapies. PAI reporter genes that operate in the near-infrared (NIR) window are particularly desirable owing to the minimal absorption of endogenous photoacoustic molecules at these wavelengths (12).

Although several PAI reporter genes have been developed and have shown substantial value in preclinical studies, their clinical utility is potentially limited owing to their nonhuman origin or undesirable toxicity (12). We sought to develop a PAI reporter gene system that overcomes these issues to increase the potential for clinical translation. As such, a member of the organic anion–transporting polypeptide (OATP) family of proteins, namely OATP1B3, is endogenously expressed in the human liver and is responsible for hepatocyte uptake of the NIR fluorescent dye indocyanine green (ICG) during liver function tests. Previous research has also shown that OATP1B3 can take up ICG into cells that express it and can be used as a fluorescence reporter gene system (13,14). In this study, we extended these previous studies to establish the combined use of OATP1B3 and ICG as a PAI human reporter gene and NIR fluorescent reporter–probe system.

Materials and Methods

All animal experiments were performed in compliance with an approved protocol of the University of Western Ontario’s Council on Animal Care (Animal Use Protocol 2016-026) and in accordance with the standards of the Canadian Council on Animal Care.

Generation of Stable Cells

Human (MDA-MB-231) and murine (4T1) triple-negative breast cancer cells were transduced with lentivirus encoding tdTomato fluorescent protein overnight in the presence of 4–8 mg/mL polybrene. Transduced cells were washed, collected, and sorted by using a FACSAria III fluorescence-activated cell sorter (BD Biosciences, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) for positive tdTomato fluorescence, generating tdTomato control cells. A subset of these cells was then transduced with a second lentivirus co-encoding zsGreen fluorescent protein and OATP1B3 and sorted for equivalent tdTomato fluorescence intensity relative to the original tdTomato control cells, as well as for positive zsGreen fluorescence. The resulting population was named tdTomato OATP1B3 cells.

Immunofluorescence Staining

Cells were grown on glass coverslips, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes, permeabilized in 0.02% Tween 20 (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, Mo) for 20 minutes, and incubated overnight at 4°C with rabbit anti-SLCO1B3 (OATP1B3) primary antibody (2 μg/mL working concentration; HPA004943, Sigma-Aldrich Canada, Oakville, Ontario, Canada). Goat antirabbit AlexaFluor 647–conjugated secondary antibody was then applied (1:500 dilution, 4 μg/mL working concentration; ab150079, lot E114795, Abcam, Cambridge, Mass). Cells on coverslips were counterstained with 4ʹ,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole and imaged by using an LSM Meta 510 microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

In Vitro Fluorescence Imaging

Human (MDA-MB-231) and murine (4T1) tdTomato control and tdTomato OATP1B3 cells were incubated for 90 minutes at 37°C and 5% CO2 in media containing either 35 µg/mL ICG or an equivalent volume of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) solvent. Cells were then washed three times with DMSO-containing phosphate-buffered saline (10% vol/vol), harvested from plates, and counted; 1 × 106 cells were pelleted and subsequently transferred into the wells of a custom-built 1% agarose and 0.5% intralipid phantom, designed to be asymmetric in its distribution of wells. In addition, a well containing 35 µg/mL ICG and a well containing media without ICG were included as positive and negative controls, respectively. An IVIS Lumina XRMS In Vivo Imaging System (PerkinElmer, Waltham, Mass) was used to measure ICG fluorescence intensity by using a 0.5-second exposure time, 780-nm excitation filter, and 845-nm emission filter.

In Vitro PAI

PAI of the cell phantoms was then performed by using a custom-built photoacoustic tomography system (refer to Appendix E1 [supplement] for details). The phantom was sealed with water in a modified Ziploc-type bag and submerged in a water tank along with the transducer array. The imaging array was raster scanned in three dimensions with 4-mm steps in the x-y plane and 5-mm steps in the z direction to image the entire phantom. At each scan point, signal averaging was performed over 16 laser pulses to increase the signal-to-noise ratio. Following imaging, image reconstruction was performed by using universal back-projection (15). A maximum intensity projection image of the three-dimensional stack was then acquired by using ImageJ software (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/) (16). Average signal intensity was measured from each well, and the contrast-to-noise ratio was calculated relative to an equal-sized region of interest positioned at the center of the maximum intensity projection image.

In Vivo Fluorescence Imaging

tdTomato control (n = 6) or tdTomato OATP1B3 (n = 5) MDA-MB-231 cells (3 × 105) were implanted orthotopically into the right-bearing fourth mammary fat pad of 6–8-week-old female immunodeficient nude mice (NU-Foxn1nu; Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, Mass). Fluorescence imaging (FLI) was performed with the IVIS Lumina XRMS In Vivo Imaging System, starting 48 hours after cellular implantation. Mice were anesthetized with 1%–2% isoflurane by using a nose cone attached to an activated carbon charcoal filter for passive scavenging. FLI for tdTomato was performed by using 520-nm excitation and 570-nm emission filters, and images were acquired with a 5-minute exposure time. FLI for ICG was performed by using 780-nm excitation and 845-nm emission filters, and images were acquired with a 5-minute exposure time.

In Vivo PAI

Mice were anesthetized as described earlier, and US and PAI were performed by using the Vevo LAZR-X System (Fujifilm VisualSonics, Toronto, Ontario, Canada). An LZ550 transducer was used to acquire US and PAI images with an axial resolution of 40 µm. Acoustic signals at each wavelength were measured 10 times for signal averaging. The total acquisition time per wavelength was 2.0 seconds, and a total time of approximately 1.93 minutes was required to image each section across all wavelengths. US images of tumors were first acquired, followed by NIR spectrum (680–970 nm) PAI in 5-nm increments. For each tumor, a central section, along with adjacent sections 800 μm on either side, was acquired. Regions of interest around the perimeter of each tumor in US images were outlined and subsequently overlaid onto corresponding photoacoustic images. Tumor regions of interest were processed with Vevo Laboratory Image Software (Fujifilm VisualSonics) to generate a full-spectrum photoacoustic plot for each tumor both before and 24 hours after administration of ICG. Vevo Laboratory Image Software (Fujifilm VisualSonics) was used to spectrally unmix ICG signals from tumor data to generate ICG localization images within tumors, as previously described (17).

Statistical Analysis

For all in vivo data, a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was performed to test for normality. One-way analysis of variance was performed, followed by Tukey posthoc multiple comparisons (Table E1 and Table E2 [supplement]) by using Graphpad Prism software (version 7.00 for Mac OS X; GraphPad Software, La Jolla, Calif, www.graphpad.com). For time-course experiments, repeated measures analysis of variance was performed, followed by Tukey posthoc multiple comparisons. For all tests, nominal P < .05 was considered indicative of a statistically significant difference.

Results

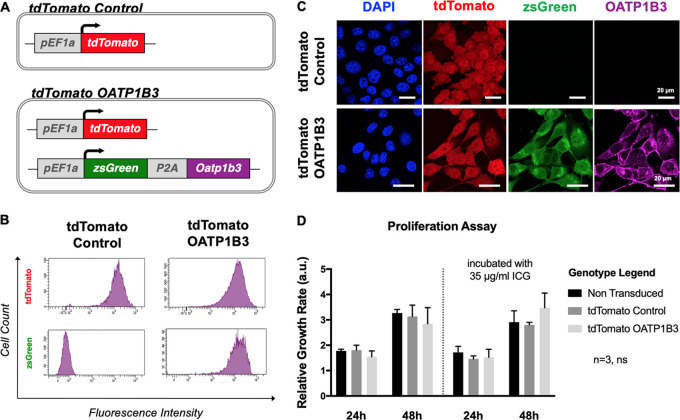

Generation of Breast Cancer Cells Expressing Fluorescent Reporters and Oatp1b3

Human (MDA-MB-231) and murine (4T1) cells were transduced first with lentivirus encoding the fluorescence reporter, tdTomato, and were subsequently sorted for tdTomato fluorescence with greater than 95% purity to generate tdTomato control cells. A subset of these was then transduced with a second lentivirus co-encoding the fluorescence reporters, zsGreen1 (zsG) and OATP1B3 (Fig 1, A). This second cell population was sorted for both tdTomato intensity equivalent to the tdTomato control cell population and zsGreen intensity with more than 95% purity to generate tdTomato OATP1B3 cells (Fig 1, B). Immunofluorescence staining validated the absence of OATP1B3 expression in tdTomato control cells, whereas positive staining was present in tdTomato OATP1B3 cells (Figs 1, C, E1, A [supplement]). Proliferation assays showed no significant difference in growth rates between nontransduced cells, tdTomato control cells, and tdTomato OATP1B3 transduced cells or between cell populations incubated in 35 μg/mL ICG for 60 minutes (Figs 1, D, E1, B [supplement]).

Figure 1:

Cell engineering and characterization. A, Diagram shows reporter gene constructs used to engineer cells that include the fluorescence reporter tdTomato (top; tdTomato control) or tdTomato in addition to the fluorescence reporter zsGreen (zsG) with organic anion–transporting polypeptide 1b3 (OATP1B3) separated by the self-cleaving peptide (P2A; bottom; tdTomato OATP1B3), each under control of the human elongation factor 1 promoter (pEF1a). B, Flow cytometry plots after lentivirus transduction of MDA-MB-231 cells with tdTomato control transfer plasmids or tdTomato OATP1B3 transfer plasmids. Fluorescence intensity is measured in relative fluorescent units. C, Confocal microscopy images of engineered MDA-MB-231 cells for nuclear staining (4, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole [DAPI], blue), tdTomato fluorescence (red), zsGreen fluorescence (green), and immunofluorescence staining for OATP1B3 expression (purple). Scale bar = 20 µm. D, Bar charts show relative growth rates (in arbitrary units [a.u.]) of nontransduced, tdTomato control, and tdTomato OATP1B3 cells grown in the presence or absence of 35 μg/mL indocyanine green (ICG). Error bars represent 1 standard deviation. ns = not significant.

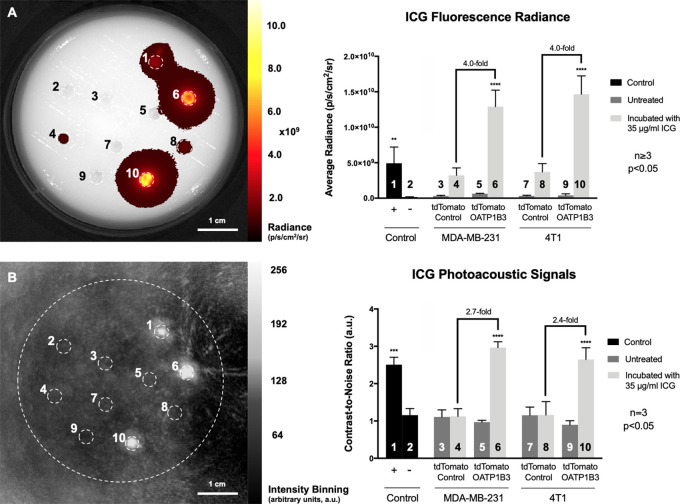

In Vitro ICG-enhanced FLI and PAI of Breast Cancer Cells Expressing OATP1B3

Next, we evaluated FLI and PAI contrast of both human and murine cells expressing OATP1B3 incubated with or without ICG. Both MDA-MB-231 and 4T1 tdTomato OATP1B3-expressing cells incubated with 35 μg/mL ICG, and subsequently washed, exhibited significantly increased fluorescence radiance (in photons/sec/cm2/sr) at ICG wavelengths relative to ICG-incubated tdTomato control cells (4.0-fold increase, P < .05; Fig 2, A). Fluorescence radiance from ICG-incubated tdTomato OATP1B3 cells was also significantly increased relative to an equivalent volume of 35 μg/mL ICG alone as the positive control (2.6-fold increase; P < .05). No significant difference in fluorescence radiance was observed at ICG wavelengths between tdTomato control and tdTomato OATP1B3 cells not incubated with ICG, ruling out any contribution of zsGreen to signals at NIR wavelengths. PAI of the same phantom at 780 nm was performed by using a custom-built PAI system. Photoacoustic contrast-to-noise ratio (arbitrary units [au]) was significantly increased for both MDA-MB-231 (2.7-fold increase; P < .05) and 4T1 (2.4-fold increase; P < .05) tdTomato OATP1B3 cells incubated with 35 μg/mL ICG, relative to contrast-to-noise ratio of ICG-incubated tdTomato control cells and all untreated controls (Fig 2, B). PAI of tdTomato control cells incubated with ICG did not exhibit a significant difference in contrast-to-noise ratio relative to untreated control cells. In addition, it is important to note that both MDA-MB-231 and 4T1-treated control cells exhibited an average fluorescence radiance that was greater than the fluorescence radiance from untreated controls, indicating that there was marginal uptake of ICG by control cells. However, at PAI, these same treated control cells did not demonstrate contrast enhancement greater than that for untreated controls, suggesting that the threshold for the detection for ICG using PAI is greater than that for ICG using fluorescence imaging. Furthermore, OATP1B3 has been previously established as an MRI reporter gene at high field strengths based on its ability to take up the positive contrast material, that is, the clinically used paramagnetic contrast agent gadolinium ethoxybenzyl diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (13). To evaluate this in our cells on a clinical 3-T system, we performed an inversion recovery experiment of tdTomato control and tdTomato OATP1B3 MDA-MB-231 cells and found significantly increased spin-lattice relaxation rates (4.9-fold increase; P < .05) from tdTomato OATP1B3 cells incubated with 6.4 mmol/L gadolinium ethoxybenzyl diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid for 1 hour, compared with all other control conditions (Fig E2 [supplement]).

Figure 2:

In vitro fluorescence imaging (FLI) and photoacoustic imaging (PAI). A, Image from FLI (left) acquired with 780-nm excitation and 845-nm emission filters in asymmetric custom-built phantom with well containing (1) 35 µg/mL indocyanine green (ICG) in media, (2) media alone, (3) human breast cancer (MDA-MB-231) tdTomato control cells, (4) MDA-MB-231 tdTomato control cells incubated with 35 μg/mL ICG, (5) MDA-MB-231 tdTomato OATP1B3 cells, (6) MDA-MB-231 tdTomato OATP1B3 cells incubated with 35 µg/mL ICG, (7) murine breast cancer (4T1) tdTomato control cells, (8) 4T1 tdTomato control cells incubated with 35 μg/mL ICG, (9) 4T1 tdTomato OATP1B3 cells, and (10) 4T1 tdTomato OATP1B3 cells incubated with 35 μg/mL ICG. Bar chart (right) shows fluorescence radiance (in photons/sec/cm2/sr) for each numbered region of interest. Error bars represent 1 standard deviation. B, Image from PAI of same phantom (left) acquired with optical excitation at 780 nm. Bar chart (right) shows contrast-to-noise ratios relative to the center of the phantom (in arbitrary units [a.u.]) for each numbered region of interest. Error bars represent 1 standard deviation.

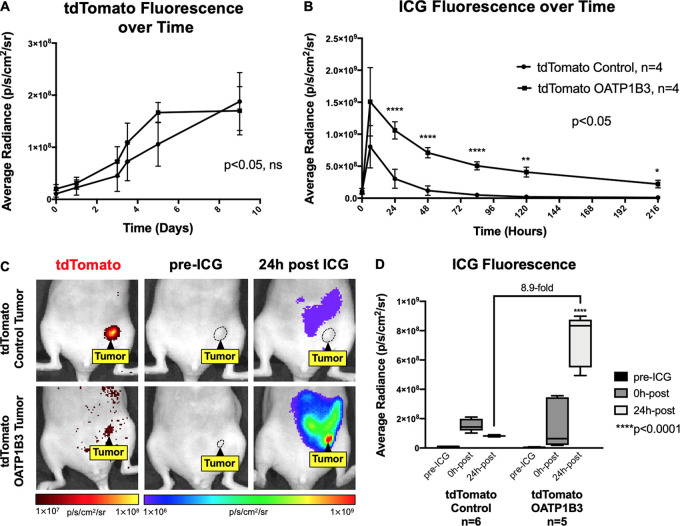

ICG-enhanced FLI Signal from OATP1B3-expressing Tumors

No significant difference in fluorescence radiance (in photons/sec/cm2/sr) at tdTomato wavelengths was found between tdTomato control (n = 4) and tdTomato OATP1B3 (n = 4) tumors over time, suggesting comparable tumor growth rates (Fig 3, A). Longitudinal FLI for ICG fluorescence after intraperitoneal administration of 8 mg/kg ICG showed that the largest significant difference in ICG signals between tdTomato control and tdTomato OATP1B3 tumors occurred 24 hours after ICG (Fig 3, B). Accordingly, a second cohort of animals was imaged before ICG administration and 24 hours after ICG. Neither tdTomato control (n = 6) nor tdTomato OATP1B3 (n = 5) tumors generated FLI radiance at ICG wavelengths before ICG administration, confirming no possible contribution by zsGreen (Fig 3, C, middle column). Before ICG administration, the mean fluorescence radiance measures (± standard deviation) for ICG were not significantly different between tdTomato control tumors (9.14 × 106 photons/sec/cm2/sr ± 3.49) and tdTomato OATP1B3 tumors (7.41 × 106 photons/sec/cm2/sr ± 1.86). In contrast, 24 hours after ICG administration, tdTomato OATP1B3 tumors exhibited significantly increased (8.9-fold) fluorescence (7.36 × 108photons/sec/cm2/sr ± 1.77) relative to tdTomato control tumors (8.22 × 107photons/sec/cm2/sr ± 0.527; P < .05; Fig 3, D). FLI signals at ICG wavelengths were also detected from the abdomen of mice with tdTomato control and tdTomato OATP1B3 tumors 24 hours after ICG administration, likely from the physiologic hepatobiliary clearance of ICG (18) (Fig 3, C).

Figure 3:

In vivo fluorescence imaging (FLI) of engineered tumors. A, Graph shows tdTomato fluorescence radiance (in photons/sec/cm2/sr) of tdTomato control (n = 4) and tdTomato OATP1B3 (n = 4) tumors over time. B, Graph shows ICG fluorescence radiance (in photons/sec/cm2/sr) of tdTomato control (n = 4) and tdTomato OATP1B3 (n = 4) tumors for up to 9 days after administration of 8 mg/kg ICG. C, Images from FLI for tdTomato (first column) and indocyanine green (ICG) average radiance (in photons/sec/cm2/sr) before (pre-ICG, second column) and 24 hours after (24h post, third column) administration of 8-mg/kg ICG in a representative mouse with a human breast cancer (MDA-MB-231) tdTomato control tumor (top) or an MDA-MB-231 tdTomato OATP1B3 tumor (bottom). Tumors are outlined with dashed lines. tdTomato signal is directly proportional to tumor size. D, Bar chart shows fluorescence radiance (in photons/sec/cm2/sr) of tdTomato control (n = 6) and tdTomato OATP1B3 (n = 5) tumors before administration of ICG (pre-ICG), immediately after intraperitoneal injection of ICG (0h-post), and 24 hours after ICG administration (24h-post). Error bars represent 1 standard deviation. Whiskers represent the range of observed values.

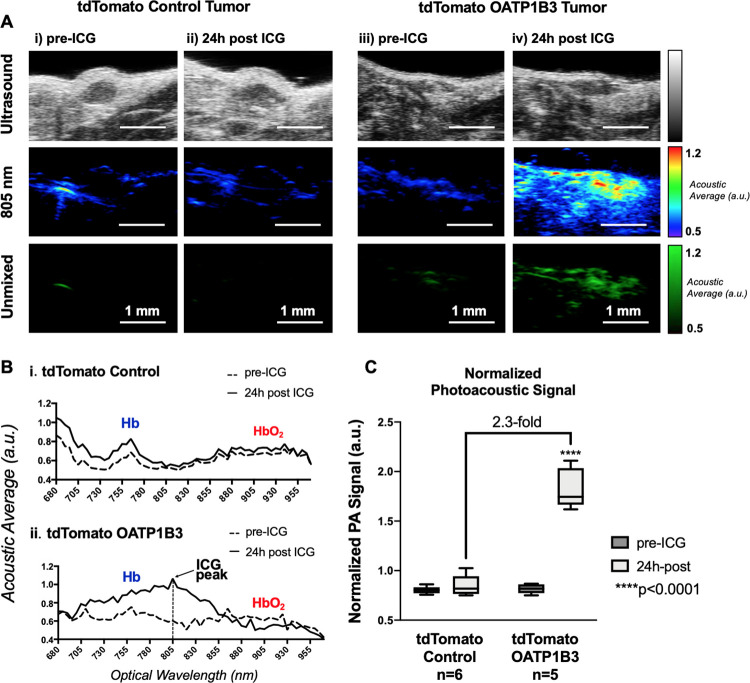

ICG-enhanced PAI Signal from OATP1B3-expressing Tumors

Before ICG administration, tdTomato control and tdTomato OATP1B3 tumor morphology was discernible on US, enabling the acquisition of PAI baseline signals in field of views encompassing tumor boundaries (Fig 4, A). As there was variance in tumor size, background signals, and tumor morphology within and across tdTomato control and tdTomato OATP1B3 tumor groups, the mean hemoglobin (HbO2) PA signals, measured from acoustic average as λ ε (855, 955), Δλ = 5 nm, was calculated for each acquired spectrum and used to normalize the signal acquired at 805 nm. This ICG-to-HbO2 signal ratio, referred to as normalized PA signal (arbitrary units), was not statistically different between tdTomato control (mean, 0.72 au ± 0.09 [standard deviation]) and tdTomato OATP1B3 (mean, 0.85 au ± 0.16) tumors before injection of ICG. Normalized PA signal was also not significantly different between images of tdTomato control tumors obtained before and after ICG administration (mean, 0.75 au ± 0.13; Fig 4, C). Conversely, 24 hours after ICG administration, tdTomato OATP1B3 tumors demonstrated significantly increased normalized PA signals (mean, 1.92 au ± 0.40) relative to all other groups (P < .05). Importantly, tdTomato OATP1B3 tumors exhibited increased PAI signal within a narrow absorption band spanning from 695 to 855 nm, with a consensus maximum peak at 805 nm across all tdTomato OATP1B3 tumors 24 hours after ICG.

Figure 4:

In vivo near-infrared spectral photoacoustic imaging (PAI). A, US scans (top), PAI image at 805 nm (middle), and spectrally unmixed image of indocyanine green (ICG) distribution across all wavelengths (bottom) of a representative human breast cancer (MDA-MB-231) tdTomato control tumor and tdTomato OATP1B3 tumor before and 24 hours after administration of 8 mg/kg ICG. Contrast enhancement at PAI is seen in tdTomato OATP1B3 tumors 24 hours after ICG administration, whereas tdTomato control tumors do not exhibit increased signals 24 hours after ICG administration. B, Near-infrared PAI spectra of a representative tdTomato control tumor (top) and tdTomato OATP1B3 tumor (bottom) before and 24 hours after administration of 8 mg/kg ICG, each labeled with hemoglobin (HbO2) and deoxyhemoglobin (Hb) peaks. Increased photoacoustic signals are observed exclusively within tdTomato OATP1B3 tumors 24 hours after ICG, with a maximum at 805 nm (ICG peak). C, Bar chart shows ICG-to-HbO2 ratio, referred to as the normalized photoacoustic signal, across tumor and treatment groups. a.u. = arbitrary units. Error bars represent 1 standard deviation. Whiskers represent the range of observed values.

Ex Vivo FLI Confirms Selective ICG Retention in OATP1B3-expressing Tumors

zsGreen fluorescence (10-second exposure, 480-nm excitation filter, and 520-nm emission filter) was absent in tdTomato control tumor sections but present in tdTomato OATP1B3 tumor sections. Importantly, ICG FLI signal (10-second exposure, 780-nm excitation filter, and 845-nm emission filter) was visible only in tdTomato OATP1B3 tumor sections. Fluorescence microscopy was also conducted, which further validated the presence and/or absence of tdTomato and zsGreen signals from FLI of tumors (Fig E3 [supplement]).

Discussion

In this study, we established OATP1B3 and ICG as a reporter gene–probe system for in vivo PAI of engineered cell populations. We generated a lentiviral vector encoding OATP1B3, allowing for engineering of cell lines to stably express this ICG transporter. Cells engineered to express OATP1B3 demonstrated significantly increased fluorescence signals at NIR wavelengths after incubation with ICG, which was not observed in control cells. At PAI, OATP1B3-expressing cells incubated with ICG exhibited significantly increased signals in vitro, whereas ICG-incubated control cells were virtually undetectable. We also demonstrated that OATP1B3-expressing breast cancer cells can be implanted to grow orthotopic tumors in vivo, and a significantly increased FLI and PAI signal was seen in small tumors (<1 mm3) 24 hours after administration of ICG. Importantly, we demonstrated that the increase in PAI detection was specific to the 695–855-nm wavelength range, with a consensus maximal peak at 805 nm, allowing for accurate in vivo identification of a reporter gene–enhanced PAI signal. We further validated selective retention of ICG by OATP1B3-expressing tumors.

Our study extends previous work on OATP1B3, establishing it as a multimodality reporter for numerous clinically relevant modalities such as FLI, and now PAI, and also introduces the potential for OATP1B3 reporter gene imaging on a clinical 3-T MRI scanner. OATP1B3-enhanced PAI uniquely offers a nonionizing and cost-effective method to detect engineered cell populations with high sensitivity and relatively high resolution. Clinical PAI systems can image up to 7 cm (19); thus, future work should establish how many OATP1B3-expressing cells can be detected at specific depths in larger animal models. A caveat of this system is that the engineered cells to be imaged at PAI should not be located beyond optical-scattering material, for example, within the adult human skull, where the light needed to excite ICG would be largely reflected by bone before getting to the engineered cells. However, this issue may be solved with the use of more penetrative PAI systems that are being developed (20,21). The ability to evaluate the status of a gene or cell population by using whole-body (MRI) (22), localized (PAI), and microscopic (fluorescence) imaging techniques with a single reporter gene system could be broadly useful for many biomedical applications, such as tracking the viability and migration of therapeutic cells in patients (23,24). Rat-derived Oatp1a1 and the tracer indium 111 ethoxybenzyl diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid have also been established as a reporter gene–probe pair for SPECT (25). Studies evaluating human OATP1B3 as a SPECT reporter gene are warranted to further extend the potential utility of this human reporter beyond FLI, PAI, and MRI and improve cellular detectability because of the higher probe sensitivity offered by SPECT.

The ideal PAI reporter gene would be specific to the biologic process of interest, exhibit an absorption maximum within the NIR window for deep tissue in vivo imaging, and be nontoxic to the cell. Although other reporter genes for PAI have been described (eg, NIR fluorescent proteins and photo-switchable fluorescent proteins), the PAI reporter gene arguably considered to have the highest translational potential is human TYR (tyrosinase), which initiates the conversion of endogenous tyrosine into detectable melanin (17,26–28). Although TYR presents desirable properties, including human origin, signal amplification due to enzymatic action, and a detectible product with high photostability, it is not without limitations (7). For instance, the melanin photoacoustic profile displays a broadband, featureless absorption spectrum, making it difficult to differentiate ectopic melanin from other intrinsic signals with accuracy (12). Our OATP1B3-ICG system, conversely, features a distinct band within the NIR region that is easy to identify and unmix from hemoglobin and deoxyhemoglobin spectra and from spectra of other PAI reporters added to the biologic system for more complex functional imaging. It is also interesting to note that wells in the in vitro experiments containing a sample of ICG-incubated OATP1B3-engineered cells exhibited greater fluorescence radiance (2.6-fold increase) and PAI signals (1.19-fold increase) relative to the positive control well containing a sample of ICG at the treatment concentration. This suggests that the uptake of ICG by OATP1B3 occurs in an active or active-coupled process, rather than simple diffusion, which is in agreement with current theories describing the uptake mechanisms of the OATP1 family of transporters (29). Although TYR exhibits signal amplification due to enzymatic action, OATP1B3 may provide signal amplification through active or active-coupled uptake of many ICG molecules. In addition, altered cell phenotype and toxicity associated with ectopic TYR activity have been documented (26,30,31), in so much that TYR-encoding plasmid distributors (eg, Imanis Life Sciences, Rochester, Minn) recommend inducible promoters to minimize undesired biologic effects during imaging studies. Although documented experiments are limited in number, ectopic OATP1B3 overexpression has not been reported to cause cellular toxicity or confer observable phenotypic changes (14,32), and we did not observe any quantitative or qualitative differences in cell proliferation rates and/or morphology in our own work—even when engineered cells were incubated in the presence of ICG. As performed in this study, it was important to assess the effectiveness of this system at the preclinical stage by using doses of ICG equivalent to current clinical guidelines. Although ICG is safe to inject at these doses, further safety evaluation may be warranted on the intracellular toxicity of ICG once it is internalized by the OATP1B3 transporter. It should also be noted that the detection of engineered cells near the hepatobiliary system would be difficult, as clearance of ICG within that pathway obscures the ability to detect OATP1B3-engineered cells retaining ICG.

In the clinic, PET reporter genes have currently been used for imaging of adenoviral gene therapy (5) and cytotoxic T-cell immunotherapies (6) in patients with cancer. These studies mark major milestones in reporter gene imaging, but limited access and costs owing to associated infrastructure and operation, in combination with concerns over ionizing radiation, may hinder broad applicability and longitudinal imaging with PET reporter genes. These limitations highlight the need for alternative reporter gene systems for safe, cost-effective, and accessible imaging modalities within the clinic. Although nuclear imaging (PET/SPECT) is capable of whole-body visualization and photoacoustics is limited to localized imaging, reporter gene imaging with PAI should be applicable for a variety of clinical problems that only require imaging of specific tissues (33). For example, including the OATP1B3 reporter gene in the genetic engineering protocol of chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapies targeting prostate cancer stem cells (34) would allow for longitudinal monitoring of these cells in the prostate by using an intraperitoneal laser/transrectal transducer system (35). We expect this technology to be particularly useful in clinical trials that involve the localized injection of a gene or cellular therapy into a specific tissue, as it allows for obtaining real-time information on how a particular therapy is operating in the patient. Questions of interest are as follows: Is the therapy getting to the target site? Is it activating at the target site? For how long does it persist? Does reporter expression correlate with patient response? However, until more gene-based and cell-based therapeutics make their way into the clinic, we expect that this multimodality reporter system will be more rapidly used for tracking of gene expression and cell populations in preclinical animal models.

APPENDIX

SUPPLEMENTAL FIGURES

Authors declared no funding for this work.

Disclosures of Conflicts of Interest: N.N.N. disclosed no relevant relationships. L.C.M.Y disclosed no relevant relationships. J.J.L.C disclosed no relevant relationships. T.J.S. disclosed no relevant relationships. J.A.R. disclosed no relevant relationships.

Abbreviations:

- FLI

- fluorescence imaging

- ICG

- indocyanine green

- NIR

- near infrared

- OATP

- organic anion–transporting polypeptide

- PAI

- photoacoustic imaging

References

- 1.James ML, Gambhir SS. A molecular imaging primer: modalities, imaging agents, and applications. Physiol Rev 2012;92(2):897–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dubey P. Reporter gene imaging of immune responses to cancer: progress and challenges. Theranostics 2012;2(4):355–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu H, Yang H, Zhu D, et al. Systematically labeling developmental stage-specific genes for the study of pancreatic β-cell differentiation from human embryonic stem cells. Cell Res 2014;24(10):1181–1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fesnak AD, June CH, Levine BL. Engineered T cells: the promise and challenges of cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2016;16(9):566–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jacobs A, Voges J, Reszka R, et al. Positron-emission tomography of vector-mediated gene expression in gene therapy for gliomas. Lancet 2001;358(9283):727–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keu KV, Witney TH, Yaghoubi S, et al. Reporter gene imaging of targeted T cell immunotherapy in recurrent glioma. Sci Transl Med 2017;9(373):eaag2196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weber J, Beard PC, Bohndiek SE. Contrast agents for molecular photoacoustic imaging. Nat Methods 2016;13(8):639–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi W, Park EY, Jeon S, Kim C. Clinical photoacoustic imaging platforms. Biomed Eng Lett 2018;8(2):139–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stoffels I, Morscher S, Helfrich I, et al. Metastatic status of sentinel lymph nodes in melanoma determined noninvasively with multispectral optoacoustic imaging. Sci Transl Med 2015;7(317):317ra199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shubert J, Lediju Bell MA. Photoacoustic imaging of a human vertebra: implications for guiding spinal fusion surgeries. Phys Med Biol 2018;63(14):144001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jose J, Grootendorst DJ, Vijn TW, et al. Initial results of imaging melanoma metastasis in resected human lymph nodes using photoacoustic computed tomography. J Biomed Opt 2011;16(9):096021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brunker J, Yao J, Laufer J, Bohndiek SE. Photoacoustic imaging using genetically encoded reporters: a review. J Biomed Opt 2017;22(7):070901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu MR, Liu HM, Lu CW, et al. Organic anion-transporting polypeptide 1B3 as a dual reporter gene for fluorescence and magnetic resonance imaging. FASEB J 2018;32(3):1705–1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Graaf W, Häusler S, Heger M, et al. Transporters involved in the hepatic uptake of (99m)Tc-mebrofenin and indocyanine green. J Hepatol 2011;54(4):738–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu M, Wang LV. Universal back-projection algorithm for photoacoustic computed tomography. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys 2005;71(1 Pt 2):016706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods 2012;9(7):671–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paproski RJ, Heinmiller A, Wachowicz K, Zemp RJ. Multi-wavelength photoacoustic imaging of inducible tyrosinase reporter gene expression in xenograft tumors. Sci Rep 2014;4(1):5329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cusin F, Fernandes Azevedo L, Bonnaventure P, Desmeules J, Daali Y, Pastor CM. Hepatocyte concentrations of indocyanine green reflect transfer rates across membrane transporters. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2017;120(2):171–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Valluru KS, Willmann JK. Clinical photoacoustic imaging of cancer. Ultrasonography 2016;35(4):267–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nie L, Cai X, Maslov K, Garcia-Uribe A, Anastasio MA, Wang LV. Photoacoustic tomography through a whole adult human skull with a photon recycler. J Biomed Opt 2012;17(11):110506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nasiriavanaki M, Xia J, Wan H, Bauer AQ, Culver JP, Wang LV. High-resolution photoacoustic tomography of resting-state functional connectivity in the mouse brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014;111(1):21–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nyström NN, Hamilton AM, Xia W, Liu S, Scholl TJ, Ronald JA. Longitudinal visualization of viable cancer cell intratumoral distribution in mouse models using Oatp1a1-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Invest Radiol 2019;54(5):302–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li M, Wang Y, Liu M, Lan X. Multimodality reporter gene imaging: construction strategies and application. Theranostics 2018;8(11):2954–2973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kircher MF, de la Zerda A, Jokerst JV, et al. A brain tumor molecular imaging strategy using a new triple-modality MRI-photoacoustic-Raman nanoparticle. Nat Med 2012;18(5):829–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patrick PS, Hammersley J, Loizou L, et al. Dual-modality gene reporter for in vivo imaging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014;111(1):415–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thangasamy T, Sittadjody S, Limesand KH, Burd R. Tyrosinase overexpression promotes ATM-dependent p53 phosphorylation by quercetin and sensitizes melanoma cells to dacarbazine. Cell Oncol 2008;30(5):371–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krumholz A, Vanvickle-Chavez SJ, Yao J, Fleming TP, Gillanders WE, Wang LV. Photoacoustic microscopy of tyrosinase reporter gene in vivo. J Biomed Opt 2011;16(8):080503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zheng H, Zhou L, Shi Y, Tian J, Wang F. Tyrosinase-bsed reporter gene for photoacoustic imaging of microRNA-9 regulated by DNA methylation in living subjects. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2018;11:34–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stieger B, Hagenbuch B. Organic anion-transporting polypeptides. Curr Top Membr 2014;73:205–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Greggio E, Bergantino E, Carter D, et al. Tyrosinase exacerbates dopamine toxicity but is not genetically associated with Parkinson’s disease. J Neurochem 2005;93(1):246–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hasegawa T. Tyrosinase-expressing neuronal cell line as in vitro model of Parkinson’s disease. Int J Mol Sci 2010;11(3):1082–1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Monks NR, Liu S, Xu Y, Yu H, Bendelow AS, Moscow JA. Potent cytotoxicity of the phosphatase inhibitor microcystin LR and microcystin analogues in OATP1B1- and OATP1B3-expressing HeLa cells. Mol Cancer Ther 2007;6(2):587–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steinberg I, Huland DM, Vermesh O, Frostig HE, Tummers WS, Gambhir SS. Photoacoustic clinical imaging. Photoacoustics 2019;14:77–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deng Z, Wu Y, Ma W, Zhang S, Zhang YQ. Adoptive T-cell therapy of prostate cancer targeting the cancer stem cell antigen EpCAM. BMC Immunol 2015;16:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lediju Bell MA, Kuo NP, Song DY, Kang JU, Boctor EM. In vivo visualization of prostate brachytherapy seeds with photoacoustic imaging. J Biomed Opt 2014;19(12):126011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.