Abstract

For decades, researchers have been interested in humans’ ability to quickly detect threat-relevant stimuli. Here we review recent findings from infant research on biased attention to threat, and discuss how these data speak to classic assumptions about whether attention biases for threat are normative, whether they change with development, and what factors might contribute to this developmental change. We conclude that while there is some stability in attention biases in infancy, various factors—including temperamental negative affect and maternal anxiety—also contribute to shaping the development of biased attention.

Keywords: Infancy, attention to threat, attention bias, development

For decades, researchers from cognitive, social, and clinical backgrounds have been interested in humans’ ability to quickly detect threat-relevant stimuli. As a result, two separate literatures have emerged on the topic. One literature suggests that because of its adaptive nature, biased attention to threat—which we define as prolonged or rapid attention to a perceived threat—should be normative, early emerging, and stable within individuals across development (Öhman & Mineka, 2001). Indeed, adults detect threat-relevant animals (e.g. snakes/spiders) and threat-relevant human faces (e.g. fearful/angry) more quickly than benign control stimuli (Öhman, Flykt, & Esteves, 2001; Öhman, Lundqvist, & Esteves, 2001). Further, developmental work demonstrates that children as young as ages 3 to 5 years detect snakes and spiders more quickly than a variety of non-threat-relevant animals, and detect angry and fearful faces more quickly than happy, sad, and neutral faces (see LoBue & Rakison, 2013, for a review).

However, despite a large literature showing stability in attention biases for threat over the lifespan, a second and equally large literature links variations in attention biases for threat to fearful temperament, anxiety symptoms, and disorder. For example, adults with snake and spider phobias detect the object of their fears faster than non-phobic individuals (Öhman, Flykt, & Esteves, 2001). Similarly, anxious individuals detect threat-relevant faces more quickly than non-anxious controls (see Van Bockstaele et al., 2014 for a review). Further, several studies suggest a potential causal link between attention biases for threat and anxiety by demonstrating that systematically training individuals’ attention away from threat decreases self-reported anxiety levels (see Heeren et al., 2015 for review, but see Cristea, Mogoase, David, & Cuijpers, 2015). In fact, the link between attention bias and anxious behavior has been established in children as young as 2 to 5 years (LoBue & Pérez–Edgar, 2014; Pérez-Edgar et al., 2011). Together, this second literature suggests that attention biases for threat might be linked to individual differences and experiences related to fear or anxiety, hinting at the potential for change across the lifespan.

To disentangle these seemingly divergent lines of research, Field and Lester (2010) posed a critical question: Is there room for development in attention biases for threat? Further, they proposed several models of how attention biases for threat-relevant stimuli might develop over the first few years of life, and how these biases may be linked to anxiety. The integral bias model, like the traditional normative model described above, posits that development plays no role in attentional biases for threat; individuals who initially have an attention bias maintain that bias over time. The moderation model predicts that development moderates the expression of existing attention biases, suggesting that attention biases for threat are normative early in life, wane across development for most people, and persist only in a select group who go on to develop anxiety in adulthood. Finally, the acquisition model predicts that attentional biases are caused by specific events during development, and are the result of direct experiences.

These models pointedly frame several critical questions for research: Are attention biases for threat present early in life? Do they diminish in some people over time, while persisting, or becoming exacerbated, in others who then develop greater risk for anxiety? In addition, do these patterns develop primarily based on individual differences or specific life experiences?

Until recently, there were very little data to speak to these questions, given that methodological limitations (e.g. tasks requiring button press responses) prevented researchers from studying attention biases in children under the age of 3. However, recent advances in eye-tracking technology have allowed researchers to modify traditional attention bias paradigms, like the adult visual search and dot-probe tasks, into passive viewing paradigms that are appropriate for infants (for review see Burris et al., 2019). Here, we review recent findings from the infancy literature on attention biases for various threats, and reflect on how we might use these data to test classic questions about whether attention biases for threat are normative, whether and for whom biases change over the course of development, and if so, what factors might contribute to this developmental change.

Is there room for development in attention biases for threat?

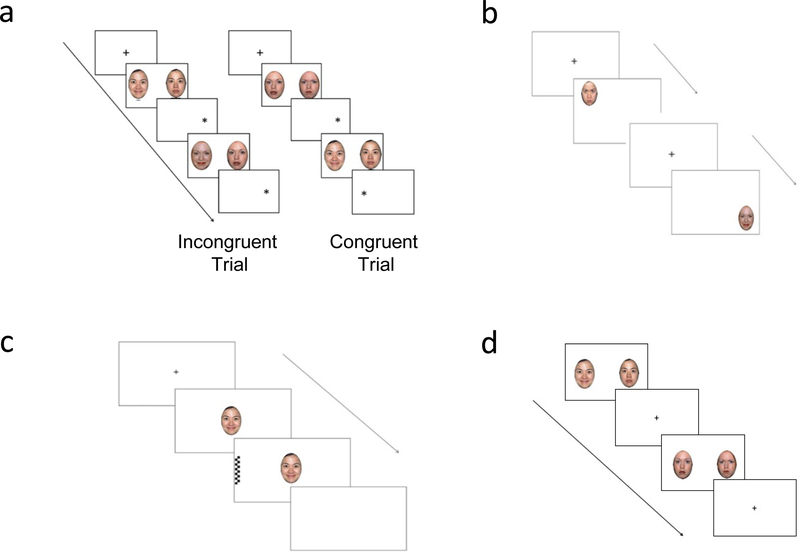

Using new passive-viewing eye-tracking methodologies for capturing attention biases in infants (see Figure 1), several studies have demonstrated that attention biases for threat begin to develop between 5 and 7 months of age, and are relatively stable over the first two years of life. For example, 5-month-old infants do not differentially allocate attention to fearful versus happy faces based on both looking and ERP measures (e.g., Peltola, Leppänen, Mäki, & Hietanen, 2009). However, by 7 months of age, infants look longer at fearful faces (Peltola et al., 2009) and show greater difficulty disengaging from fearful faces versus other facial expressions (Peltola et al., 2013). Further, Burris et al. (2017) recently showed that infants and young children ranging from 9- to 48- months of age show group-level attention biases towards emotion in general, indicating cross-sectional stability of these biases from infancy to early childhood.

Figure 1.

Summary of passive-viewing eye-tracking tasks used to measure attention biases for threat in infancy. For a comprehensive review of these tasks and how they were modified from classic adult visual attention tasks for use with infants, see Burris et al. (2019).

However, there is little correlation between within-subject biased attention patterns in earlier and later infancy, suggesting that change might be taking place on an individual level (e.g., Burris & Rivera, 2019; Peltola, Yrttiaho, & Leppänen, 2018). For example, Peltola at el. (2018) reported that biased attention to fearful faces in 7-month-olds declines over time, and there is no correlation between attention biases at 7 months and 24 months. Burris and Rivera (2019) also tested infants longitudinally across a two-year period and found that while group level biases existed between 9–48 months and again two years later, they were not correlated. These recent longitudinal studies suggest attention biases for threat are present early in development, but can change at the individual level sometime during the first two years of life.

Other recent work suggests that patterns of age-related changes vary across different types of threats. In a cross-sectional study of 4- to 24-month-old infants, LoBue and colleagues (2017) reported that an attention bias for snakes is evident by 4 months of age, it is evident at a group level across the age range, and is unrelated to negative affect (LoBue, Buss, Taber-Thomas, & Pérez-Edgar, 2017). However, these infants showed age-related differences in their responses to angry faces, with a general increase in looking time to angry faces with age. Further, for infants temperamentally high in negative affect, attending longer to angry faces was related to slower subsequent fixations to a neutral probe (Pérez-Edgar et al., 2017). These findings suggest that attention biases for different kinds of threat-relevant stimuli might have different developmental trajectories, and perhaps, different underlying processes.

What factors drive change in biased attention over the course of development?

The research reviewed above suggests that attention biases for threat—and social threats in particular—can change over time. Several key factors may drive these changes in the first two years of life. As mentioned above, several studies have reported a relation between rapid attention to threat and fear or anxiety. Further, difficulty disengaging from threat-relevant faces has also been linked to higher negative affect (Pérez-Edgar et al., 2017; Nakagawa et al., 2012). Importantly, there is evidence that negative temperamental traits in early infancy may impact future attentional patterns in some individuals. For example, attention biases to threat measured at age 5 mediate the relation between infants’ behaviorally inhibited temperaments and social withdrawal at age 5 (Pérez-Edgar et al., 2011). Moreover, as discussed above, negative affect in infancy has been linked to concurrent measures of attention bias for angry faces (Pérez-Edgar et al., 2017).

There is also evidence that maternal psychopathology—a known risk factor for anxiety—can impact biased attention to threat. Several studies have shown that older children (aged 6 to 14) of anxious mothers demonstrate heighted attention to threat-relevant faces (Mogg, Wilson, Hayward, Cunning, & Bradley, 2012; Montagner et al., 2016). Recently, Morales et al. (2017) reported that this relation begins in infancy, as maternal anxiety is associated with difficulty disengaging from angry, but not happy faces, for 4- to 24-month-old infants.

Beyond individual factors such as negative affect and maternal psychopathology, attention bias to threat in infancy is also associated with social processes. For example, one recent study showed that disengagement from threat-relevant faces at 7 months was related to later attachment security (Peltola et al., 2015). Another reported that increased attention to emotional faces at 7 months was related to more frequent helping behavior at 24 months and reduced callous‐unemotional traits at 48 months, suggesting that there may be social benefits to having early attentional systems tuned to emotion in general (Peltola et al., 2018). Finally, cognitive mechanisms, like attentional control, may play an increasingly influential role in modulating attentional responses to threat, particularly in infants high in negative affect (Fu et al., 2019). Although this work is relatively new and requires replication, it suggests that various factors can influence the development of biased attention over the first few years of life.

Future research

Altogether, emerging research with infants has begun to shed light on some of the classic questions surrounding attention biases for threat and their development. The tentative conclusion that we can begin to draw from this work is that there is some stability in attention biases for threat over the first two years of life, supporting the normative perspective. However, research reviewed here also suggests that there is indeed room for development in attention biases for threat, particularly in the development of biases for social threats like angry and fearful faces. Factors like negative affect and maternal anxiety, as well as attachment and attentional control, might play a role in shaping biased attention. In turn, biased attention might play a role in shaping the trajectory of children’s socioemotional development. These findings (most consistent with Field and Lester’s (2010) moderation model) suggest that attentional biases for threat are normative early in life, but infants who have a persistent bias for threat-relevant social information might be at the most risk for anxiety.

Despite the promise of this new work, a great deal of future research is still needed. First and foremost, to study how early attention biases develop and interact with other factors, longitudinal studies are particularly needed. One recent longitudinal study on attention biases for angry faces shows that there is instability in attention biases to threat across early childhood, but that group level biases persist from at least the first to fourth year of life (Burris & Rivera, 2019). Importantly, this study also shows that infants who exhibit a persistent bias towards threat across early childhood also show significantly higher levels of anxiety, again consistent with Field and Lester’s moderation model.

Second, while some researchers have reported relations between attention biases for threat, negative affect, and maternal anxiety, others have not (e.g. negative affect: Morales et al., 2017, Burris et al., 2017, Pérez-Edgar et al., 2017; maternal anxiety: Leppänen et al., 2018, Morales et al., 2017). It is possible that measurement differences, or additional mediating variables could explain these inconsistent findings. However, future longitudinal research is needed to disambiguate inconsistencies in this emerging literature.

One problem is that across studies, researchers have lumped together different types of threat (e.g., snakes/spiders, fearful/angry faces), each of which might have attention biases that develop differently, and importantly, different studies have used different indices to measure biased attention. For example, some studies have used vigilance to threat as their primary index, as measured by latency to detect a threat-relevant target (e.g., Öhman et al., 2001; LoBue & DeLoache, 2008). Alternatively, others have used disengagement from threat, or the amount of time it takes an individual to look away from a threat-relevant stimulus (e.g., Morales et al., 2017; Nakagawa et al., 2012; Peltola et al., 2008, 2013). Further, other researchers have used visual engagement with threat, or the duration of time that a person remains fixated on a threat-relevant stimulus, and how the presence of threat influences subsequent processing, such as the detection of a neutral probe (e.g., LoBue et al., 2017; Pérez-Edgar et al., 2017) (see Figure 1, and Burris et al., 2019 for a detailed review).

Importantly, it is not clear that these different components of attention are related to the same underlying process. Indeed, different components of visual attention are innervated by subtly different neural pathways and mechanisms, and may differentially impact the overall attentional profile of an infant and/or whether that infant is at risk for developing anxiety. For example, based on the findings reviewed here, it is possible that vigilance in infancy is normative, but problems disengaging from threat develop over time in consort with other factors like temperamental negative affect or maternal anxiety. The infant literature is currently too sparse to draw any concrete conclusions in this domain, so future work that disambiguates the components of attention as they relate to biased attention patterns is needed.

Another important avenue for future work is investigating the underlying neural processes at play in the development of attention to threat. A number of studies have reported that infants show differential neural responses to threat-relevant stimuli (Hoehl et al., 2008; Leppänen et al., 2007), these differences are evident as young as 7 months of age (Peltola et al., 2009), and may be influenced by environmental factors like parenting (Taylor-Colls & Fearon, 2015). What we currently lack is an understanding of how different attentional patterns to threat in infancy relate to concurrent changes in the brain, and how different neural patterns may relate to other factors that influence biased attention. Future research investigating how neural responses to threat are related to attention might help elucidate the mechanisms for developmental change in infancy and early childhood.

In conclusion, we hope that this review inspires new developmental research on biased attention to threat in infancy so that we can more clearly disambiguate how normative biases diverge into potentially maladaptive pathways of socioemotional development. To do so, we recommend that future research take a more nuanced approach to studying biased attention and considers different types of threat (social, nonsocial), different mechanisms of attention (e.g., vigilance, difficulty disengaging), and of course, development. These avenues of investigation are invaluable for current theories of human threat perception, and for the practical development and implementation of empirically supported and developmentally appropriate treatments for anxiety.

Recommended Readings.

-

Field and Lester (2010). See reference list

A thorough theoretical analysis of patterns of attention to threat across development.

-

Leppänen et al., 2018. See reference list

An example of a study that aimed to link infant attention to threat to maternal anxiety and depression

-

Burris, Barry-Anwar, and Rivera (2017). See reference list.

A representative study that illustrates original research about attention bias to threat early in life.

-

Perez-Edgar et al., 2017. See reference list.

A representative study that illustrates original research on relations between attention to threat and temperamental negative affect.

-

Morales, S., Fu, X., & Pérez-Edgar, K. E. (2016). A developmental neuroscience perspective on affect-biased attention. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 21, 26–41.

A comprehensive review of affect-biased attention from a developmental neuroscience perspective.

References

- Burris JL, Barry-Anwar RA, Rivera SM (2017). An eye tracking investigation of attentional biases towards affect in young children. Developmental Psychology, 53, 1418–1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burris JL, Rivera SM (2019, under invited resubmission). A longitudinal investigation of attentional biases toward affect and their link to anxiety symptomology in early childhood. [Google Scholar]

- Burris J, Buss KA, LoBue V, Pérez-Edgar K, Field AP (2019, in press). Biased attention to threat and anxiety: On taking a developmental approach. Journal of Experimental Psychopathology. [Google Scholar]

- Cristea IA, Mogoase C, David D, & Cuijpers P. (2015). Practitioner review: cognitive bias modification for mental health problems in children and adolescents: a meta‐analysis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 56, 723–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field AP, & Lester KJ (2010). Is there room for ‘development’ in developmental models of information processing biases to threat in children and adolescents? Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 13, 315–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu X, Morales S, Brown KM, LoBue V, Buss KA, Pérez-Edgar KE (2019, under invited resubmission). Temperament moderates developmental changes in vigilance to emotional faces in infants: Evidence from an eye-tracking study. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeren A, Mogoase C, Philippot P, & McNally RJ (2015). Attention bias modification for social anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical psychology review, 40, 76–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoehl S, & Striano T. (2008). Neural processing of eye gaze and threat‐related emotional facial expressions in infancy. Child Development, 79, 1752–1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leppänen JM, Cataldo JK, Enlow MB, & Nelson CA (2018). Early development of attention to threat-relevant facial expressions. PLOS ONE, 13, e0197424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leppänen JM, Moulson MC, Vogel-Farley VK, & Nelson CA (2007). An ERP study of emotional face processing in the adult and infant brain. Child Development, 78, 232–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LoBue V, Buss KA, Taber-Thomas BC, & Pérez-Edgar K. (2017). Developmental differences in infants’ attention to social and nonsocial threats. Infancy, 22, 403–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LoBue V. & DeLoache JS (2008). Detecting the snake in the grass: Attention to fearrelevant stimuli by adults and young children. Psychological Science, 19, 284–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LoBue V, & Rakison D. (2013). What we fear most: A developmental advantage for threat-relevant stimuli. Developmental Review, 33, 285–303. [Google Scholar]

- LoBue V, & Pérez-Edgar K. (2014). Sensitivity to social and non-social threats in temperamentally shy children at-risk for anxiety. Developmental Science, 17, 239–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogg K, Wilson KA, Hayward C, Cunning D, & Bradley BP (2012). Attentional biases for threat in at-risk daughters and mothers with lifetime panic disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 121, 852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montagner R, Mogg K, Bradley BP, Pine DS, Czykiel MS, Miguel EC, … Salum GA (2016). Attentional bias to threat in children at-risk for emotional disorders: Role of gender and type of maternal emotional disorder. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 25, 735–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales S, Brown KM, Taber-Thomas BC, LoBue V, Buss KA, & Pérez-Edgar KE (2017). Maternal anxiety predicts attentional bias towards threat in infancy. Emotion, 17, 874–883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa A, & Sukigara M. (2012). Difficulty in disengaging from threat and temperamental negative affectivity in early life: A longitudinal study of infants aged 12–36 months. Behavioral and Brain Functions, 8, 40–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öhman A, Flykt A, & Esteves F. (2001). Emotion drives attention: detecting the snake in the grass. Journal of experimental psychology: general, 130, 466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öhman A, Lundqvist D, & Esteves F. (2001). The face in the crowd revisited: a threat advantage with schematic stimuli. Journal of personality and social psychology, 80, 381–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öhman A, & Mineka S. (2001). Fears, phobias, and preparedness: Toward and evolved module of fear and fear learning. Psychological Review, 108, 483–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peltola MJ, Leppänen JM, Palokangas T, & Hietanen JK (2008). Fearful faces modulate looking duration and attention disengagement in 7-month-old infants. Developmental Science, 11, 60–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peltola MJ, Leppänen JM, Mäki S, & Hietanen JK (2009). Emergence of enhanced attention to fearful faces between 5 and 7 months of age. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 4, 134–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peltola MJ, Hietanen JK, Forssman L, & Leppänen JM (2013). The emergence and stability of the attentional bias to fearful faces in infancy. Infancy, 18, 905–926. [Google Scholar]

- Peltola MJ, Forssman L, Puura K, van IJzendoorn MH, & Leppänen JM (2015). Attention to faces expressing negative emotion at 7 months predicts attachment security at 14 months. Child Development, 86, 1321–1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peltola MJ, Yrttiaho S, & Leppänen JM (2018). Infants’ attention bias to faces as an early marker of social development. Developmental Science, 21, e12687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Edgar K, Morales S, LoBue V, Taber-Thomas BC, Allen EK, Brown KM, & Buss KA (2017). The impact of negative affect on attention patterns to threat across the first two years of life. Developmental Psychology, 53, 2219–2232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Edgar K, Reeb-Sutherland BC, McDermott JM, White LK, Henderson HA, Degnan KA, Hane AA, Pine DS, & Fox NA (2011). Attention biases to threat link behavioral inhibition to social withdrawal over time in very young children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39, 885–895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor‐Colls S, & Pasco Fearon RM (2015). The effects of parental behavior on infants’ neural processing of emotion expressions. Child Development, 86, 877–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bockstaele B, Verschuere B, Tibboel H, De Houwer J, Crombez G, & Koster EH (2014). A review of current evidence for the causal impact of attentional bias on fear and anxiety. Psychological Bulletin, 140, 682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]