Abstract

The current study examined school variations in academic engagement norms and whether such norms affect those most susceptible to peer influence. We presumed that behaviors associated with perceived popularity make norms salient and are most likely to affect socially marginalized (rejected) youth. Focusing on differences across 26 middle schools, the main aim was to test whether academic engagement norms moderate the association between peer rejection and subsequent academic difficulties. The U.S. public school sample included 5,991 youth (52% girls): 32% Latino/a, 20% White, 14% East/Southeast Asian, 12% African American, and 22% from other specific ethnic groups. Multilevel models were used to examine whether engagement norms moderated the association between sixth grade peer rejection and changes in grade point average (GPA) and academic engagement across middle school (i.e., from sixth to eighth grade). Consistent with our contextual moderator hypothesis, the association between peer rejection and academic engagement was attenuated-- and in the case of GPA eliminated-- in schools where higher engagement was a salient norm. The study findings suggest that the behaviors of popular peers affect those on social margins, and that academic difficulties are not inevitable for rejected youth.

Susceptibility to peer influence is a hallmark of adolescence (Allen & Antonishak, 2008; Brechwald & Prinstein, 2011; Steinberg & Monahan, 2007). Driven by the desire to gain peer approval (Blakemore & Mills, 2014), adolescents are especially attuned to the behaviors of their high status peers, and modify their conduct to align with those at the top of the social hierarchy (Cohen & Prinstein, 2006; Dijkstra & Gest, 2015). Given the fundamental need to be a part of a group (Baumeister & Leary, 1995), youth on the social margins-- who are rejected by their peers-- may be particularly susceptible to emulate the behaviors associated with high status classmates in middle school. To examine such peer influence processes, the current study focuses specifically on academic behaviors because peer rejection is frequently associated with lower grades and test scores in middle school (Bellmore, 2011; Mikami & Hinshaw, 2006; Wentzel, 2003). Our goal is to shed light on how school level variations in the academic (dis)engagement of popular peers moderates the academic vulnerability of rejected youth during middle school.

Following the transition to middle school, academic achievement and engagement tend to decline (Akos, Rose, & Orthner, 2015; Juvonen, Le, Kaganoff, Augustine, & Constant, 2004). Such declines are often attributed to developmentally insensitive environmental changes, including larger school size and departmentalized instruction, which misalign with the needs of young adolescents (Eccles & Roeser, 2009). However, academic declines might also reflect changing social norms and youth’s greater sensitivity to norms set by high status peers. Indeed, anti-academic behaviors (e.g., tardiness, disengagement) appear to become socially valued in mi ddle school (Galván, Spatzier, & Juvonen, 2011; Merten, 1996). At this developmental phase when young adolescents are seeking independence from adult authority (Collins & Laursen, 2004), academic effort and hard work can signal compliance with authority in ways that jeopardize social status among classmates (Juvonen & Murdock, 1993).

Although, on average, academic engagement may be less socially valued in middle school compared to elementary school, the relevant norms are likely to vary across schools. In some middle schools, academic behaviors may be unrelated to popularity, while there may be some schools where the most popular youth are academically engaged. Little is known about such setting-level variability because that requires large samples recruited across multiple schools. One of the few exceptions is a study by Dijkstra and Gest (2015) where data were available for 164 classrooms across 30 Dutch secondary schools. Correlations between an academic reputation (“good learner”) and popularity ranged from −.42 to .27 across the classrooms, suggesting substantial variability in both the valence (negative vs. positive) and salience (strength) of academic norms. Although in most classrooms popularity was negatively associated with a good student reputation, contextual variations in the strength and valence of the classroom level correlations contributed to who was socially accepted in that setting. Also, a smaller U.S.-based study revealed that when coolness was positively associated with academic disengagement, slacking off was related to improved social status (Galván et al., 2011). Together, these findings suggest that the behaviors associated with perceived popularity make particular norms salient (cf. Cialdini, Kallgren, & Reno, 1991) and the degree to which individuals emulate norms is related to their subsequent position in the social hierarchy.

Not all youth are equally likely to be swayed by the norms promoted by popular peers. We presume that youth on the social margins have the greatest need to boost their social status. This assumption is consistent with the idea that the motivation to be part of a group is heightened when belonging is threatened (Williams & Sommer, 1997). Indeed, experimentally induced rejection (i.e., Cyberball) increases adult participants’ effort on group tasks, presumably as a strategy to regain social acceptance (Williams & Sommer, 1997). Research on adolescents, in turn, demonstrates that rejected youth are more susceptible to peer influence than those who are accepted by their classmates (Dishion, Piehler, & Myers, 2008; Dishion & Tipsord, 2011). However, relevant adolescent research has been studied mainly in the context of negative peer influence (e.g., deviance training; Snyder et al., 2010). Hence, little is known about whether rejected youth can be influenced in positive ways.

It is particularly important to examine academic norms and behaviors because in middle school peer rejection is associated with poor school adjustment and academic achievement (Bellmore, 2011; Mikami & Hinshaw, 2006; Ollendick, Weist, Borden, & Greene, 1992; Wentzel, 2003). To gauge whether such findings capture the achievement potential or orientation of peer rejected youth versus their desire to boost their social status in settings where it is “cool” not to engage or do well in school, it is necessary to examine academic correlates of peer rejection across settings where academic norms vary. The key question is whether the link between peer rejection and lower academic performance can be attenuated in settings where perceived popularity is associated with high engagement.

Current Study

Focusing on early adolescence— a time when peer influence peaks (Steinberg & Monahan, 2007) and academic achievement tends to decline (Akos et al., 2015; Juvonen et al., 2004) – we examine whether school level academic norms moderate the association between peer rejection and academic functioning in middle school. Specifically, we test the contextual moderator effects of academic engagement norms during the first year in middle school on changes in academic engagement and performance by the end of middle school (i.e., Grades 6–8). We hypothesized that in schools where low academic engagement is a salient norm, peer rejection is academically costly, predicting greater declines in engagement and grades across middle school. In contrast, schools where higher engagement predicts greater perceived popularity (“coolness”), the typically documented negative association between peer rejection and academic adjustment (i.e., engagement and GPA) is expected to be attenuated.

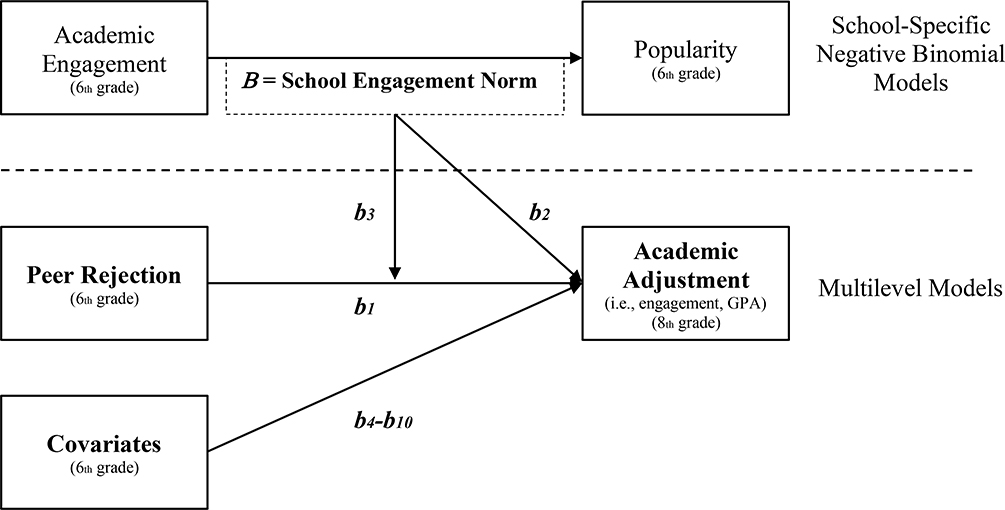

We capture school-specific academic norms --that vary in valence (negative vs. positive) and salience (strength) --by relying on two independently assessed constructs: perceived popularity (“coolness”) and teacher-reported academic engagement. Extending prior research that captures academic norms with setting-specific bivariate correlations (e.g., Correia, Brendgen, & Vitaro, 2019; Dijkstra & Gest, 2015; Galvan et al., 2011; Laninga-Wijnen, Ryan, Harakeh, Shin, & Vollebergh, 2018), we rely on a more advanced regression approach. Figure 1 provides a conceptual diagram of our index of the school level academic norms and the tested associations (cf. Juvonen, Lessard, Schacter, & Enders, 2018; Smith, Schacter, Enders, & Juvonen, 2018). The top part of the figure depicts how we assess academic norms by relying on the school-specific regression coefficients of academic engagement predicting perceived popularity. Assuming that this engagement norm estimate (B) functions as a contextual moderator, we then test a cross-level interaction between peer rejection (measured at individual level) and school level engagement norms (that vary in valence and salience, indicated by b3) on subsequent academic performance.

Figure 1.

Conceptual diagram of associations between school level (above dashed line) engagement norms (popularity regressed on academic engagement within schools; B) and individual level (below dashed line) peer rejection and other relevant covariates predicting academic adjustment (b4-b10).

The present study contributes to the existing research in several ways. First, we use a school-contextual moderation approach which sheds light on how norm salience of academic engagement varies across schools. That is, rather than assuming that all middle schools have similar (anti-academic) norms, we are interested in the heterogeneity across schools. Second, we consider how individual susceptibility (i.e., rejected status) interacts with engagement norms signaled by high status peers. Third, we are particularly interested in positive peer influence processes (cf. Choukas-Bradley, Giletta, Cohen, & Prinstein, 2015; van Hoorn, van Dijk, Meuwese, Rieffe, & Crone, 2016). In other words, we test whether the academic risks associated with peer rejection can be attenuated in schools with salient positive engagement norms.

Method

Participants

The present investigation relies on data from a large, longitudinal study of adolescents recruited from 26 urban public middle schools in California (N = 5,991; 52% girls). Based on self-reported ethnicity in sixth grade, the sample was 32% Latino/a, 20% Caucasian/White, 14% East/Southeast Asian, 12% African American/Black, and 22% from other ethnic groups, including biracial and multiethnic. The proportion of students eligible for free or reduced lunch price (a proxy for school socioeconomic status) ranged from 18% to 86% (M = 47.6, SD = 18.3) across the 26 schools. The average number of sixth-grade participants across the schools was 220 (SD = 106).

Procedure

The study was approved by the relevant Institutional Review Board and school districts. During recruitment, all sixth grade students and families received informed consent and informational letters. Parental consent rates averaged 81% across the schools. Only students who turned in signed parental consent and provided written assent participated. Data collection was conducted in schools, where trained researchers read aloud the survey in each classroom. Students received $5 in sixth grade and $10 in eighth grade for completion of the surveys.

Measures

Individual level variables

We rely on multiple sources of data: peer-reports to assess social reputations (i.e., popularity, rejection), teacher-reports of academic engagement, as well as school records of grades.

Peer nominations

As part of a larger peer nomination protocol, students completed two peer nomination items assessing perceived popularity and peer rejection. The current analyses rely on peer nominations received in the spring of sixth grade when reputations have been formed. Although we recognize the potential of reputations to vary across years, meta-analytic data indicate a high degree of stability in peer nominations (Jiang & Cillessen, 2005).

Nominations were unlimited, and other-sex nominations were allowed because these procedures result in scores with superior psychometric properties (i.e., reliability, discriminant validity; Terry & Coie, 1991). For each participant, the number of nominations received for each construct was totaled.1

Students were instructed to write the names of their grademates who fit a particular description. To assess perceived popularity, students responded to an ecologically valid question of “who is cool?” (Juvonen & Ho, 2008). The number of nominations received ranged from 0 to 81 (M = 1.31; SD = 3.28). These nominations were used to compute academic engagement norms within each school (see below). Peer rejection was based on students’ nominations of students who they “do not like to hang out with” (Graham & Juvonen, 1998). The number of rejection nominations received ranged from 0 to 41 (M = 1.14; SD = 2.00). To account for school size differences on peer rejection (e.g., 10 nominations in a school of 100 versus a school of 400), z scores for the rejection nominations received were computed within schools for each participant (Cairns, Cairns, Neckerman, Gest, & Gariepy, 1988).

Teacher-rated academic engagement

One teacher completed the Short Form of the Teacher Report of Engagement Questionnaire (TREQ; Connell & Wellborn, 1991) with six items in the sixth and eighth grades. The items assess the degree to which students were perceived as engaged, as opposed to disaffected from school activities (e.g., “This student works hard in my class”; α6th grade = 0.91; α8th grade = 0.93). Items were rated on a 4-point scale (1 = not at all characteristic of this student to 4 = very characteristic), with higher mean values indicating higher levels of academic engagement (M6th = 2.70, SD6th = .76; M8th = 2.75, SD8th = .76). These scores at sixth grade were used as a baseline assessment of engagement, while the eighth grade scores were used as one of the two academic adjustment outcomes. The sixth grade scores were also used to compute the school-specific indicator of norm salience (see below).

Grade point average

Students’ grade point average (GPA) was calculated using school transcripts during sixth grade (baseline) as well as at eighth grade (outcome). End-of-year grades for all courses were coded on a 5-point scale (A = 4 and F = 0) and then averaged to create a composite GPA for each student (M6th = 3.11, SD6th = .78; M8th = 3.01, SD8th = .85).

Control variables

Several individual level control variables linked to academic adjustment were used in the analyses. Students reported their sex and ethnicity in the sixth grade. In addition, parent level of education was used as a proxy for student socioeconomic status. The parent/guardian who completed informed consent indicated his/her highest level of education on a 6-point scale (1 = elementary/junior high school to 6 = graduate degree) in the beginning of the study.

School level variables

Between school differences were captured with our index of academic engagement norms, assessed at sixth grade.

Academic engagement norms

As mentioned earlier, to capture the valence and salience of academic engagement norms, we relied on two independent sources of data: teacher-rated academic engagement as well as peer nominations of perceived popularity (“coolness”) at each school. Because most youth do not receive any nominations for perceived popularity and the majority of nominations are received by a relatively small proportion of students, the popularity variable is highly skewed and overdispersed (i.e., standard deviation is larger than the mean; Gazelle, Faldowski, & Peter, 2015). As such, the highest values are greater than what would be predicted by a Poisson distribution, which uses a common parameter for the mean and variance. To accommodate the low modal score and long tail, we therefore used negative binomial regression to estimate the slope of academic engagement on popularity (Hilbe, 2011). Estimates of the negative binomial regression slopes were computed separately at each school. Higher negative slope values indicate a strong negative association between academic engagement and popularity, whereas positive values capture schools where it is cool to be academically engaged.

Multilevel Analysis Plan

The data were analyzed in Mplus 8.0 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2019) using a standard multilevel linear model to account for the nested data (i.e., students nested within 26 middle schools; Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002) and to examine school level effects (i.e., academic engagement norms). In all analyses, we took into account sex, ethnicity (four dummy coded variables with Latinos, the largest ethnic group, as the reference group), SES, and baseline levels of each of the academic adjustment indicators. A cross-level interaction term between peer rejection and engagement norms was included to test our main contextual-moderator hypothesis (i.e., the association between sixth grade peer rejection and eighth grade academic adjustment varies as a function of school level academic engagement norms). For statistically significant interactions, tests of simple slopes were conducted to compare the academic functioning of youth at schools one standard deviation below, at, and one standard deviation above the average academic engagement norm. The equation below depicts the prototype for the final model tested, wherein each indicator of academic adjustment (AAij) was examined as a function of peer rejection (PRij), within-school academic engagement norms (AENj), their cross-level interaction (PRij) (AENj), and the aforementioned set of individual and school level covariates.

| (1) |

Full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation was used to address missing data. FIML treats all observed predictors as single-item latent variables, allowing each individual to contribute whatever data they have to the likelihood function and is preferable to listwise deletion (Little, Jorgensen, Lang, & Moore, 2014). FIML is also frequently utilized in longitudinal studies, as it allows for generalizing research findings to the sample population (Enders, 2010).

Results

The results are reported in two sections. Before the multilevel analyses testing our main hypothesis, we provide descriptive information about the school level indicator of academic engagement norms.

Engagement Norms

Academic engagement norms (reflecting both the valence and salience of engagement) were computed within each of our 26 middle schools by regressing popularity reputation on teacher-rated academic engagement scores. Negative values indicate that popular students are less engaged, whereas positive values indicate that popular students are more academically engaged. Consistent with past research, at the majority of schools there was a negative association between popularity and academic engagement (M = −0.27; SD = 0.40). The schoollevel academic engagement norm values ranged from −0.79 to 0.94, demonstrating wide variation.

Multilevel Models

Intraclass correlations (ICC) were estimated by testing intercept-only models and calculating the proportion of variance at Level 2 (school level) separately for each dependent variable. The ICC for GPA was .16 and .03 for academic engagement. Thus, 16% and 3% of the variation in the indicators of GPA and academic engagement respectively, were due to differences between the 26 middle schools.

Model 1 and Model 2 effects are displayed in Table 1. We interpret first the main effects models (Model 1) by describing the effects of the covariates, followed by the main predictor effects across the two outcomes. Thereafter, the hypothesized contextual moderator effects are described in Model 2.

Table 1.

Multilevel models predicting eighth-grade academic engagement and grade point average.

| 8th Grade Outcomes |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academic Engagement | Grade Point Average | |||||||

| Predictors | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||||

| Individual level | b | 95% CI | b | 95% CI | b | 95% CI | b | 95% CI |

| Girl | 0.11** | 0.03, 0.18 | 0.10** | 0.03, 0.18 | 0.11*** | 0.08, 0.14 | 0.11*** | 0.07, 0.14 |

| African American | −0.06 | −0.17, 0.04 | −0.06 | −0.17, 0.04 | −0.07 | −0.14, 0.00 | −0.07 | −0.14, 0.00 |

| Asian | 0.35*** | 0.26, 0.44 | 0.35*** | 0.26, 0.44 | 0.26*** | 0.20, 0.32 | 0.26*** | 0.20, 0.32 |

| White | 0.17*** | 0.11, 0.23 | 0.17*** | 0.10, 0.23 | 0.10** | 0.04, 0.15 | 0.10** | 0.04, 0.15 |

| Other | 0.11*** | 0.05, 0.17 | 0.11*** | 0.05, 0.17 | 0.04 | −0.01, 0.08 | 0.04 | −0.01, 0.08 |

| SES | 0.04*** | 0.02, 0.06 | 0.04*** | 0.02, 0.06 | 0.04*** | 0.03, 0.05 | 0.04*** | 0.03, 0.05 |

| Baseline Outcome | 0.39*** | 0.34, 0.44 | 0.39*** | 0.34, 0.44 | 0.71*** | 0.68, 0.74 | 0.71*** | 0.68, 0.74 |

| Peer Rejection | −0.08*** | −0.10, −0.06 | −0.08*** | −0.10, −0.06 | −0.04*** | −0.05, −0.02 | −0.03*** | −0.05, −0.02 |

| School level | ||||||||

| Engagement Norm | 0.03 | −0.12, 0.17 | 0.03 | −0.12, 0.18 | 0.01 | −0.13, 0.14 | 0.01 | −0.12, 0.14 |

| Cross-level interaction | ||||||||

| Rejection X Engagement Norm | 0.07* | 0.01, 0.12 | 0.06† | 0.00, 0.12 | ||||

Note. N = 5991. CI = Confidence interval. Sex reference group = boy; Ethnicity reference group = Latino.

p < .001

p < .01

p < .05

p <.07.

Main effects models

Table 1 displays the summary of the multilevel models testing our contextual moderation hypothesis. Individual level covariates revealed that girls were rated by teachers as more academically engaged (b = .11, p = .004) and received higher grades (b = .11, p < .001) relative to boys in the eighth grade. Ethnic differences emerged, such that compared to Latino students, Asian (engagement: b = .35, p < .001; GPA: b = .26, p < .001) and White (engagement: b = .17, p < .001; GPA: b = .10, p = .001) students received higher scores. Higher levels of parental education were associated with higher academic outcomes (engagement: b = .04, p < .001; GPA: b = .04, p < .001). In addition, sixth grade (baseline) academic adjustment was a robust predictor of eighth grade engagement (b = .39, p < .001) and GPA (b = .71, p < .001), indicating the relative stability of academic adjustment.

Controlling for the covariates, we turn to the main effects of the predictors of interest: peer rejection and academic engagement norms. Even after accounting for baseline academic differences, students who more rejected by their peers in the sixth grade were rated as less academically engaged (b = −.08, p < .001) and received lower grades (b = −.04, p < .001) two years later (i.e., eighth grade). Finally, the main effect of academic engagement norms (interpreted at average levels of peer rejection) was non-significant for each academic outcome (engagement: b = .03, p = .713; GPA: b = .01, p = .914), suggesting that the norm valence and salience of academic engagement did not, on average, predict changes in engagement and grades from sixth to eighth grade.

Contextual moderation models

We turn next to the hypothesized contextual moderator effects of engagement norms. The findings are presented separately for teacher-rated engagement and GPA. Cross-level interactions were interpreted with follow-up analyses examining the simple slopes between peer rejection and the academic outcomes at one SD below (i.e., low engagement norms), and one SD above (i.e., high engagement norms) the mean of academic engagement norm across schools.

Academic engagement

The analyses for academic engagement yielded a significant cross-level interaction between peer rejection and school engagement norms (b = .07, p = .013), suggesting that the association between sixth grade peer rejection and academic engagement at eighth grade varies across schools depending on the valence and salience of academic engagement. Analyses of simple slopes (see Figure 2) showed that while rejection predicted lower academic engagement at eighth grade, the effect was stronger in schools where perceived popularity was associated with lower engagement (i.e., −1 SD; b = −.11, p < .001), as opposed to schools where perceived popularity was related to higher academic engagement (i.e., +1 SD; b = −.05, p < .001). In other words, when youth attended schools where popularity was associated with higher academic engagement at sixth grade, peer rejection took less of a toll on students’ engagement (e.g., classroom attention, effort) across middle school, compared to schools where popularity was associated with lower engagement.

Figure 2.

The moderating role of engagement norms on the association between peer rejection and academic engagement. The values presented reflect academic engagement scores for students in schools with average, negative or positive engagement norms (± one standard deviation above or below the mean), and at the mean on all other variables.

Note. N = 5991. *** p < .001.

GPA

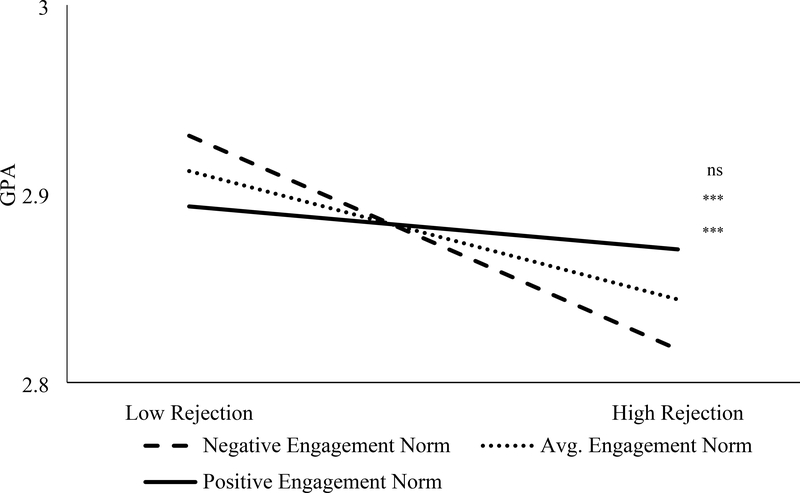

A marginally significant rejection by engagement norm interaction was obtained for GPA (b = .06, p = .066), and probed according to Aiken and West (1991). Simple slopes tests, depicted in Figure 3, revealed that at schools where perceived popularity was associated with lower engagement (i.e., −1 SD), sixth grade peer rejection predicted lower GPA at eighth grade (b = −.06, p < .001). However, at schools where perceived popularity was associated with higher engagement (i.e., +1 SD), sixth grade peer rejection was unrelated to GPA at eighth grade (b = −.01, p = .574).

Figure 3.

The moderating role of engagement norms on the association between peer rejection and GPA. The values presented reflect GPA scores for students in schools with average, negative or positive engagement norms (± one standard deviation above or below the mean), and at the mean on all other variables.

Note. N = 5991. GPA = grade point average. *** p < .001.

In sum, the association between peer rejection during the first year in middle school and subsequent academic performance varied across schools depending on the engagement behaviors of those with high social status. At schools where lower engagement was associated with perceived popularity, youth rejected by their peers at the beginning of middle school did increasingly worse academically across middle school. However, the association between peer rejection and academic engagement was attenuated, and in the context of grades – eliminated, in schools where higher engagement was associated with perceived popularity.

Discussion

The developmental need to gain acceptance and avoid rejection by peers is a potentially potent motivator in adolescence (Blakemore & Mills, 2014). To engage in socially valued behaviors by emulating the conduct of those at the top of the social hierarchy is one particularly relevant strategy to gain status (e.g., Balsa, Homer, French, & Norton, 2011; Juvonen & Ho, 2008). Presuming that peer rejection increases susceptibility to the norms conveyed by popular youth, and that such norms vary across schools, we examined the contextual moderation of norm salience (Dijkstra & Gest, 2015; Smith et al., 2018). Consistent with our main hypothesis, the results demonstrate that academic engagement norms at sixth grade moderate the association between peer rejection (during the first year in middle school) and academic functioning by the end of middle school. Emphasizing the potential of positive peer influence, our findings show that in middle schools where popularity is associated with higher (as opposed to lower) engagement, students rejected at sixth grade were no longer at risk for lower academic grades at eighth grade. These findings extend the evidence on contextual moderation of social norms and shed light on heightened susceptibility to peer influence among socially rejected youth.

Consistent with mounting evidence that popular peers are particularly influential (e.g., Cohen & Prinstein, 2006; Dijkstra & Gest, 2015; Rambaran, Dijkstra, & Stark, 2013), we captured engagement norms by focusing on the behaviors associated with perceived popularity. Although research has largely characterized popular adolescents as disengaged (Bellmore, 2011; Galvan et al., 2011), our findings indicate that the engagement behaviors of students perceived to be popular vary across schools. That is, while popularity and engagement were inversely related on average, there was substantial differences between the schools. At some schools, popular students were more likely to be actively engaged in the classroom. Such heterogeneity in engagement norms aligns with Dijkstra and Gest’s (2015) analysis of Dutch secondary schools, in which the correlation between having a popular and academic reputation ranged from largely negative to positive across classrooms.

It could be expected that such variability in engagement norms would affect most students’ academic functioning, given that publically observable behaviors associated with popularity are potentially powerful motivators in adolescence (Dijkstra & Gest, 2015; Galvan et al., 2011). However, our results showed that the engagement behaviors of popular peers did not contribute on average to changes in academic adjustment across middle school. From a motivational perspective, one can speculate that most youth do not experience threat to their social belonging (Williams & Sommer, 1997). Instead, the achievement goals of high status peers have been shown to broadly affect whom youth affiliate (Laninga-Wijnen et al., 2018). While rejected youth are likely to lack close or stable affiliates, others who share close relational bonds are more likely to be similar in achievement to their friends. That is, most youth may be more motivated to select friends whose academic behaviors align with theirs and are in turn influenced over time by the academic behaviors of these friends (see Laursen, 2017).

The main contribution of this study pertains to our findings that the influence of popular peers’ engagement behaviors may be limited mainly to those who are socially marginalized. In particular, the current results highlight differential susceptibility to peer influence based on peer rejection. Those who were more rejected appeared to modify their behaviors to be consistent with the academic norms signaled by those perceived to be popular. Based on variation in the academic norm valance and salience, peer rejection was then more academically consequential in schools where perceived popularity was negatively associated with engagement. Such results emphasize that the academic risks of peer rejection are at least partially contextually dependent. This is important because rejection is often presumed to function as a marker for individual risk factors (e.g., emotion dysregulation) that can negatively affect functioning across social and academic domains (Wentzel & Asher, 1995). The current findings suggest that a relevant individual difference captured by rejection may have to do with greater motivation to gain status and higher susceptibility to certain peer influence mechanisms.

It is important to keep in mind that the documented contextual moderation effects are relatively small, but that the tests were also quite conservative. Not only did we control for baseline indicators of academic functioning (which are quite stable over time and in turn likely to contribute to the small effect sizes), but also engagement norms across the schools in our sample were skewed in the negative direction (cf. Dijkstra, & Gest 2015). Therefore, when probing significant cross-level interactions (i.e., simple slopes), we were examining the academic risks of rejection at schools with a strong negative association between popularity and engagement (−1 SD) to schools with a weak positive association (+1 SD). We expect the academic risks of rejection would be even weaker at schools where perceived popularity is more strongly associated with higher engagement. Future studies with greater engagement norm variability across schools are needed to test this hypothesis.

In addition to considering the academic outcomes of rejected youth in more “proacademic” schools, it would be important for future work to model peer influence processes more dynamically than in the current investigation. We assessed engagement norms only at one time point –the end of the first year of middle school – to examine the effects of such norms on academic functioning across grades. However, it is possible that schools vary in the degree of norm (in)stability across grade levels. Although modeling such time-varying norms was beyond the scope of the current study, longitudinal growth modelling analyses may yield further insights about how engagement norms develop within a school. Additionally, future research is needed to consider whether behavioral characteristics or social identities of the popular peers matter. For example, given the increased salience of gender (Galambos, Almeida, & Petersen, 1990) and ethnicity (Phinney & Ong, 2007) in particular during adolescence, samegender and same-ethnicity popular peers may be especially powerful social referents.

Implications

One of the questions raised by the current findings is whether it is possible to promote positive academic norms within middle schools. While modifying peer culture is no easy task, there are relevant interventions that have shown promise in transforming problematic social norms. One such approach targets teachers specifically. For example, the Supporting Early Adolescents’ Learning and Social Success (SEALS) intervention (Hamm, Farmer, Lambert, & Gravelle, 2014) trains teachers to carefully observe and consider differences in social status and reputations of their students. Evaluation of the SEALS program showed that academic effort was more strongly associated with social prominence in middle schools where teachers learned to manage peer dynamics in a way that minimized disruptive classroom behavior (see Hamm, et al., 2014). Collaborative instructional practices (as opposed to competitive or individualistic) may be particularly likely to cultivate high engagement norms by motivating students to work together towards a common goal (Johnson, 2008).

Interventions can also target more directly the most influential peers. Relying on social referents (i.e., central peers identified through social network assessments), Paluck and colleagues developed a program where high status peers were instructed to publically disapprove hostile behaviors to reduce school level aggression (Paluck, Shepherd, & Aronow, 2016; Paluck & Shepherd, 2012). Based on the success of this program, it may be possible to utilize a similar intervention strategy to encourage outward displays of engagement among popular youth. That is, capitalizing on popular peers as agents of change may represent a promising approach to change engagement norms in ways that may be particularly helpful in attenuating the academic costs of peer rejection in middle school.

Footnotes

We account for across school variation in the number of nominators in two ways. For perceived popularity, nominations received are used only in within-school analyses (i.e., to calculate school-specific academic engagement norms) and there is therefore no between-school variance. Peer rejection nominations, in turn, were transformed to z-scores within each school to adjust for the number of nominators that reflect school size.

References

- Aiken LS, & West SG (1991) Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Akos P, Rose RA, & Orthner D (2015). Sociodemographic moderators of middle school transition effects on academic achievement. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 35, 170–198. 10.1177/0272431614529367 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, & Antonishak J (2008). Adolescent peer influences: Beyond the dark side. In Prinstein MJ & Dodge KA (Eds.), Understanding peer influence in children and adolescents (pp. 141–160). New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Balsa AI, Homer JF, French MT, & Norton EC (2011). Alcohol use and popularity: Social payoffs from conforming to peers’ behavior. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21, 559–568. 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00704.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, & Leary MR (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 497–529. 10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellmore A (2011). Peer rejection and unpopularity: Associations with GPAs across the transition to middle school. Journal of Educational Psychology, 103, 282–295. 10.1037/a0023312 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore SJ, & Mills KL (2014). Is adolescence a sensitive period for sociocultural processing? Annual Review of Psychology, 65, 187–207. 10.1146/annurevpsych-010213-115202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brechwald WA, & Prinstein MJ (2011). Beyond homophily: A decade of advances in understanding peer influence processes. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21, 166–179. 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00721.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns RB, Cairns BD, Neckerman HJ, Gest SD, & Gariépy J-L (1988). Social networks and aggressive behavior: Peer support or peer rejection? Developmental Psychology, 24, 815–823. 10.1037/0012-1649.24.6.815 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choukas-Bradley S, Giletta M, Cohen GL, & Prinstein MJ (2015). Peer influence, peer status, and prosocial behavior: an experimental investigation of peer socialization of adolescents’ intentions to volunteer. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44, 2197–2210. 10.1007/s10964-015-0373-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini RB, Kallgren CA, & Reno RR (1991). A focus theory of normative conduct: A theoretical refinement and reevaluation of the role of norms in human behavior. In Zanna MP (Ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 24, pp. 201–234). 10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60330-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen GL, & Prinstein MJ (2006). Peer contagion of aggression and health risk behavior among adolescent males: An experimental investigation of effects on public conduct and private attitudes. Child Development, 77, 967–983. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00913.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, & Laursen B (2004). Changing relationships, changing youth: Interpersonal contexts of adolescent development. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 24, 55–62. 10.1177/0272431603260882 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Connell JP, & Wellborn JG (1991). Competence, autonomy and relatedness: A motivational analysis of self-system processes. In Gunnar M & Sroufe LA (Eds.), Minnesota Symposium on Child Psychology: Vol. Vol. 23: Self processes in development. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Correia S, Brendgen M, & Vitaro F (2019). The role of norm salience in aggression socialization among friends: Distinctions between physical and relational aggression. International Journal of Behavioral Development. Advanced online publication. 10.1177/0165025419854133 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra JK, & Gest SD (2015). Peer norm salience for academic achievement, prosocial behavior, and bullying: Implications for adolescent school experiences. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 35, 79–96. 10.1177/0272431614524303 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, & Tipsord JM (2011). Peer contagion in child and adolescent social and emotional development. Annual Review of Psychology, 62, 189–214. 10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Piehler TF, & Myers MW (2008). Dynamics and ecology of adolescent peer influences. In Prinstein MJ & Dodge KA (Eds.) Understanding peer influence in children and adolescents. (pp. 72–93). New York, NY: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JS, & Roeser RW (2009). Schools, academic motivation, and stage-environment fit. In Handbook of Adolescent Psychology. 10.1002/9780470479193.adlpsy001013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK (2010). Applied missing data analysis. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Galambos NL, Almeida DM, & Petersen AC (1990). Masculinity, femininity, and sex role attitudes in early adolescence: Exploring gender intensification. Child Development, 61, 1905–1914. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb03574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galván A, Spatzier A, & Juvonen J (2011). Perceived norms and social values to capture school culture in elementary and middle school. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 32, 346–353. 10.1016/j.appdev.2011.08.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gazelle H, Faldowski RA, & Peter D (2015). Using peer sociometrics and behavioral nominations with young children. In Saracho ON (Ed.), Handbook of research methods in early childhood education: Review of research methodologies (Vol. 1, pp. 27–70). Charlotte, NC: Information Age. [Google Scholar]

- Graham S, & Juvonen J (1998). Self-blame and peer victimization in middle school: an attributional analysis. Developmental Psychology, 34, 587–599. 10.1037/0012-1649.34.3.587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamm JV, Farmer TW, Lambert K, & Gravelle M (2014). Enhancing peer cultures of academic effort and achievement in early adolescence: Promotive effects of the SEALS intervention. Developmental Psychology, 50, 216–228. 10.1037/a0032979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilbe JM (2011). Negative binomial regression. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang XL, & Cillessen AHN (2005). Stability of continuous measures of sociometric status: a meta-analysis. Developmental Review, 25, 1–25. 10.1016/j.dr.2004.08.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson LS (2008). Relationship of instructional methods to student engagement in two public high schools. American Secondary Education, 36, 69–87. [Google Scholar]

- Juvonen J, & Ho AY (2008). Social motives underlying antisocial behavior across middle school grades. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37, 747–756. 10.1007/s10964-008-9272-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Juvonen J, Lessard LM, Schacter HL, & Enders C (2018). The effects of middle school weight climate on youth with higher body weight. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 29, 466–479. 10.1111/jora.12386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juvonen J, & Murdock TB (1993). How to promote social approval: Effects of audience and achievement outcome on publicly communicated attributions. Journal of Educational Psychology, 85, 365–376. 10.1037/0022-0663.85.2.365 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Juvonen J, Le V-N, Kaganoff T, Augustine CH, & Constant L (2004). Focus on the wonder years: Challenges facing the American middle school. Rand Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Laninga-Wijnen L, Ryan AM, Harakeh Z, Shin H, & Vollebergh WAM (2018). The moderating role of popular peers’ achievement goals in 5th- and 6th-graders’ achievement-related friendships: a social network analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 110, 289–307. 10.1037/edu0000210 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laursen B (2017). Making and keeping friends: the importance of being similar. Child Development Perspectives, 11, 282–289. 10.1111/cdep.12246 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Jorgensen TD, Lang KM, & Moore EWG (2014). On the joys of missing data. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 39, 151–162. 10.1093/jpepsy/jst048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merten DE (1996). Visibility and vulnerability: Responses to rejection by nonaggressive junior high school boys. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 16, 5–26. 10.1177/0272431696016001001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mikami AY, & Hinshaw SP (2006). Resilient adolescent adjustment among girls: Buffers of childhood peer rejection and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 34, 823–837. 10.1007/s10802-006-9062-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998–2019). Mplus user’s guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Ollendick TH, Weist MD, Borden MC, & Greene RW (1992). Sociometric status and academic, behavioral, and psychological adjustment: a five-year longitudinal study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 60, 80–87. 10.1037/0022-006X.60.1.80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paluck EL, & Shepherd H (2012). The salience of social referents: a field experiment on collective norms and harassment behavior in a school social network. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 103, 899–915. 10.1037/a0030015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paluck EL, Shepherd H, & Aronow PM (2016). Changing climates of conflict: a social network experiment in 56 schools. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113, 566–571. 10.1073/pnas.1514483113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, & Ong AD (2007). Conceptualization and measurement of ethnic identity: Current status and future directions. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54, 271–281. 10.1037/0022-0167.54.3.271 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rambaran AJ, Dijkstra JK, & Stark TH (2013). Status-based influence processes: the role of norm salience in contagion of adolescent risk attitudes. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 23, 574–585. 10.1111/jora.12032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, & Bryk AS (2002). Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Smith DS, Schacter HL, Enders C, & Juvonen J (2018). Gender norm salience across middle schools: Contextual variations in associations between gender typicality and socioemotional distress. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47, 947–960. 10.1007/s10964-017-0732-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder J, McEachern A, Schrepferman L, Just C, Jenkins M, Roberts S, & Lofgreen A (2010). Contribution of peer deviancy training to the early development of conduct problems: Mediators and moderators. Behavior Therapy, 41, 317–328. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2009.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, & Monahan KC (2007). Age differences in resistance to peer influence. Developmental Psychology, 43, 1531–1543. 10.1037/0012-1649.43.6.1531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry R, & Coie JD (1991). A comparison of methods for defining sociometric status among children. Developmental Psychology, 27, 867–880. 10.1037/0012-1649.27.5.867 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Hoorn J, van Dijk E, Meuwese R, Rieffe C, & Crone EA (2016). Peer influence on prosocial behavior in adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 26, 90–100. 10.1111/jora.12173 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wentzel KR, & Asher SR (1995). The academic lives of neglected, rejected, popular, and controversial children. Child Development, 66, 754–763. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00903.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wentzel KR (2003). Sociometric status and adjustment in middle school: a longitudinal study. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 23, 5–28. 10.1177/0272431602239128 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams KD, & Sommer KL (1997). Social ostracism by coworkers: Does rejection lead to loafing or compensation?. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23, 693–706. [Google Scholar]