Abstract

Objective

We aim to explain why salivary lactoferrin (Lf) levels are reduced in patients suffering mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and sporadic Alzheimer's disease (sAD).1 We also will discuss if such Lf decrease could be due to a downregulation of the sAD associated systemic immunity.

Background

Several non‐neurological alterations have been described in sAD, mainly in skin, blood cell, and immunological capacities. We reviewed briefly the main pathophysiological theories of sAD (amyloid cascade, tau, unfolder protein tau, and amyloid deposits) emphasizing the most brain based hypotheses such as the updated tau‐related neuron skeletal hypothesis; we also comment on the systemic theories that emphasize the fetal origin of the complex disorders that include the low inflammatory and immunity theories of sAD.

New/updated hypothesis

Lf has important anti‐infectious and immunomodulatory roles in health and disease. We present the hypothesis that the reduced levels of saliva Lf could be an effect of immunological disturbances associated to sAD. Under this scenario, two alternative pathways are possible: first, whether sAD could be a systemic disorder (or disorders) related to early immunological and low inflammatory alterations; second, if systemic immunity alterations of sAD manifestations could be downstream of early sAD brain affectations.

Major challenges for the hypothesis

The major challenge of the Lf as early sAD biomarker would be its validation in other clinical and population‐based studies. It is possible the decreased salivary Lf in early sAD could be related to immunological modulation actions, but other different unknown mechanisms could be the origin of such reduction.

Linkage to other major theories

This hypothesis is in agreement with two physiopathological explanations of the sAD as a downstream process determined by the early lesions of the hypothalamus and autonomic vegetative system (neurodegeneration), or as a consequence of low neuroinflammation and dysimmunity since the early life aggravated in the elderly (immunosenescence).

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, amyloid, biomarkers, brain‐immunity interactions, hypothalamus; immunity, lactoferrin, saliva

1. OBJECTIVE

Here we aimed to discuss the hypotheses that low salivary lactoferrin (Lf) reflects dysfunctions in the immune system in sporadic Alzheimer's disease (sAD). These immunity alterations could be secondary to the early hypothalamic lesions within the neurodegenerative process, or a primary systemic disorder related to early immunological and low inflammatory alterations mainly involving the brain. The second alternative cannot be discarded, but the former seems more comprehensible and supported by the evidence.

We will analyze if sAD biomarkers and particularly salivary Lf could mirror systemic sAD alterations. Brain resilience masks the classical brain burden of protein aggregates hindering the detection of AD pathology at early stages through detection of such aggregates. Currently used preclinical biomarkers such as amyloid beta (Aβ) and tau levels in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and neuroimaging do not have high prediction validity in clinical series and are expensive and invasive. Therefore, we think that the evaluation of sAD biomarkers, such as Lf, could be a new pathway to explore.

2. BACKGROUND

2.1. Historical evolution

Genetic studies in the last century determined a clear distinction between familiar Alzheimer's disease (fAD) caused by mutations in three well‐known genes and sAD, in which genetic, epigenetic, and environmental interplay may determine the phenotype of disease. 2 , 3 fAD is commonly presented with early clinical manifestations (<5% of the AD cases) while sAD is presented with late clinical manifestations representing the majority of cases (>95% of AD cases). 2 , 3 In the evolution of AD research, predementia state definition as mild cognitive impairment (MCI) was considered a hot spot. This helped to focus the research on biomarkers in the last decade to detect sAD in early prodromic stages. It is important to detect the early manifestations of sAD by specific biomarkers to prevent the evolution of the predementia‐possible sAD to an established sAD‐dementia, in which no therapy is able to modify its fatal evolution. An increasing number of new drugs are under investigation; also, lifestyle modifications are in surveillance to accomplish this objective. 2 But, it is becoming clear that the main classical pathophysiological lesions, the folded brain proteins accumulation (tau and Aβ), detected by any method (blood, saliva, CSF, or neuroimaging) are not reliable enough for the diagnosis of this predementia phase of sAD with precision. The brain resilience to the sAD lesions over decades and the complicated detection of brain lesions impeach the early detection of the predementia phase with sufficient clinical confidence. Therefore, sAD, included in its early phases, generates several systemic body changes (skin, blood, plasma, cells, saliva, etc.) 4 that could determine biomarkers that possibly allow the sAD initial diagnosis more easily and cheaply, and with higher confidence.

In this scenario, we describe that saliva Lf could be an early biomarker for sAD. 1 This discovery, in some way serendipitous, is biologically funded. For this explanation we will first describe very briefly the “state of the art” of sAD biological causation and pathophysiology.

sAD is a complex disorder caused by the interplay of several genetic risk alleles (≈ 20), epigenetic modifications, and multiple environmental factors along with aging. 2 Among the genetic risk, apolipoprotein Eε4(APOE ε4) could be prominent in the majority of ethnic groups accompanied by ≈ 20 risk alleles (there are also 3 protective alleles). 2 , 3 The best twin study estimates approximately 50% genetic risk, 5 which is greater than the genetic risk assumed by genome‐wide association study (GWAS) and future sophisticated genetic studies may identify additional hidden genetic risk. This situation and the brain neurons’ genetic mosaicism that may contribute to sAD 6 preclude the use of genetic evaluation as a sAD biomarker tool, apart from APOE ε4, in the diagnosis of sAD. Many studies demonstrated that early epigenetic (soft heredity) clues, including DNA methylation or demethylation, histone modifications, and non‐coding RNAs, may modify the DNA (hard heredity) and the risk for sAD. To our knowledge, only one study to the date of the present publication, quantifies such sAD risk concluding that this risk is modest. 7

Hundreds of environmental, individual circumstances have been evaluated as modifiable risk/protective factor for sAD. 8 This risk contribution to sAD has been estimated between 30% to 66% in several studies. 2 , 8 It is apparent that these environmental factors have a clinical diagnostic importance but have no biomarker utility. The importance of environmental factors is clear, with the evidence in the last two decades of the decrease of sAD incidence in affluent countries. 2 , 9

A very brief summary of the pathophysiology of sAD seems is important. The most credited pathophysiology of sAD in the last three decades is the “amyloid cascade hypothesis,” determined by analogy from the genetic errors in familial AD, but in the last decade this theory has increasingly been discarded mainly due to the negative results of anti‐amyloid trials and the previously unknown biochemical role of this protein. 2 , 10 However, it has been recently demonstrated that there is another possible role of Aβ in the sAD physiopathology. Aβ is a highly conserved effector molecule in innate immunity and its role in sAD could be due to its antimicrobial action as proposed in the antimicrobial protection hypothesis. 11 The amyloid cascade hypothesis blurred the fact that phosphorylated tau deposition is the first lesion of AD type observed in normal brains since early childhood, as demonstrated in different studies. 12 , 13 These works showed that several decades prior to allocortex phosphorylated tau deposition in the locus coeruleus and other brain stem nuclei interconnected with the allocortical entorhinal and transentorhinal regions showed accumulated pre‐tangles representing early sAD tau‐related cytoskeletal alterations. Although the basic molecular mechanisms of sAD are not known, many authors accept that the degenerative process of the AD‐related cytoskeletal pathology follows the anatomical pathways for its brain propagation initiated in brain stem nuclei that could lead transneuronally to the specific brain distribution pattern of tau pathology. This is in agreement with the hypothesis showing sAD as a chronic prion‐like neurodegenerative disease. This more recent tau hypothesis explanation for sAD, gives the opportunity to find long‐term preventive strategies (drugs or lifestyle modifications) as represented in Figure 1.

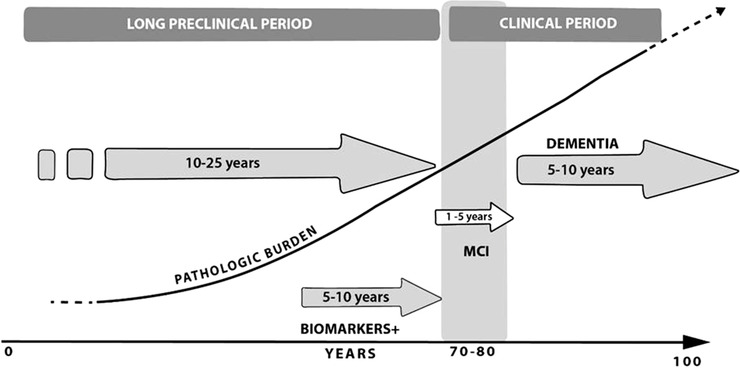

FIGURE 1.

Alzheimer's disease (AD) evolution. Presymtomatic, preclinical, and clinical periods. The diagram shows the evolution of a hypothetical AD case. The AD pathologic burden (neurofibrillary tangles and senile plaques) is represented in a rising line. The top of the figure express the AD evolution periods. The long preclinical period can be divided into pre‐symptomatic (only histological alterations) and true preclinical (positive AD biomarkers in cerebrospinal fluid or neuroimaging, without clinical manifestations). The AD clinical period is divided in the predementia state mild cognitive impairment (MCI) (gray stripe) and in the clinical dementia period. The years depicted must be considered standard ranges; moreover, the presymptomatic period could be probably >40 years in some cases, and the sporadic Alzheimer's disease dementia period could be from 3 months to 20 years. Taken from Bermejo‐Pareja, 2018 [2] with minor modifications

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT

Systematic review: We searched in PubMed for articles published in English up to November 2019 with the terms “Alzheimer's biomarkers”, “peripheral biomarkers”, “saliva proteins”, “saliva function”, “preclinical Alzheimer”, “Alzheimer prediction”, “lactoferrin”, “infections”, “immune system”, among others. In recent years, there have been intensified efforts in searching minimum or non‐invasive peripheral markers for the early diagnosis of AD, focused on blood and/or saliva. Findings have shown the association between AD and immune system, including virus, bacteria and yeast infections, which is associated with an increase inflammatory response. Moreover, it has been proposed that brain infections may be involved in the development of AD. The dissemination of oral microorganisms to the brain is controlled by antimicrobial peptides, as part of the innate immune system. In the last decade, several studies have explored the role of these antimicrobial peptides as potential biomarkers for AD. In 2017, we showed that salivary lactoferrin (Lf) discriminates between patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and AD and control subjects.

Interpretation: Findings from the main pathophysiological theories of sAD were reviewed here proposing the hypothesis that the reduced levels of salivary Lf could be related to immunological disturbances associated to sAD. This hypothesis is in agreement with two physiopathological explanations of the sAD as a downstream process determined by the early lesions of the hypothalamus and autonomic vegetative system (neurodegeneration), or as a consequence of low neuroinflammation and dysimmunity since the early life aggravated in the elderly (immunosenescence).

Future direction: Future work should confirm our results in other clinical cohorts and/or population‐based studies. This alternative theory of the sAD genesis needs more observational and experimental data to get a comprehensive understanding of the relationships between the nervous system and the immune system.

These two etiological hypotheses are the most accepted, but there are many others: the initial hypothesis of cerebral vascular hypoperfusion in sAD has been updated. 10 , 14 In addition, the popular “excessive aging” explanation for this disorder has supporters with well based scientific background; 15 Terry's “synaptic deficit”; and the “two hit hypothesis” (abnormal neuronal cell cycle re‐entry mitosis) due to oxidative stress or to other biological abnormalities have elicited many comments. 2 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 Apart from these hypotheses related to brain cell conformations there are others with more systemic underpinnings such as early fetal (or infant) stress due to inappropriate nutrition, toxins, or metabolic or infectious causes that support the Development Origin of Health and Disease (DOHaD) postulates of non‐transmissible disorders such as neurodegenerative disorders (NDD), including sAD. 2 , 17 There are more systemic‐based explanations for sAD risk based on metabolic derangements (mitochondrial oxidative stress) and metal action aberrations (calcium, aluminium, etc.). 2 , 6 , 14 , 16 None of these last mentioned hypotheses have been widely accepted. More recently, new hypotheses that implicate the gut‐brain axis or infectious agents 2 , 11 , 14 , 16 have had wide diffusion. These two hypotheses involve brain‐immunity relationships. Microbiota in the gut have immune system development functions, and anti‐infectious actions forming a biotic shield between our body and the outside world, but may contribute to low‐grade inflammation progress. 2 The infections and immunity activations have an increasing role as sAD risk factors in the literature. 11 , 18

2.2. Rationale

The immunological (and low inflammatory) alterations in sAD and in other NDD are well known. 19 The origin and intensity of these modifications attributed to sAD could be diverse. There are works indicating that early in the central nervous system (CNS) development, genetic and epigenetic modifications occur, and they are related to the immunological hypothesis. 18 , 20 Other authors suggest immunological derangements as contributing factors to the development of sAD 21 and there are other groups that consider that the immunological aberrations in sAD could be a secondary downstream phenomenon to brain lesions. 22 Recently, several authors have stressed that these immunological derangements are more accentuated during aging, 23 , 24 strengthen aging as the main risk factor of sAD. 15 In this scenario of relationships between sAD and a patient's immunological status, it is rational that a saliva component such as Lf, which has anti‐infectious and immunomodulatory functions, could be a biomarker of the immunological state of sAD, 1 as we will discuss.

3. UPDATED HYPOTHESIS

3.1. Early experimental or observational data

sAD is associated with early systemic alterations including immunological status. Two possible explanations could describe the observed immunological and low inflammatory alterations in sAD: First, an immunological “causal” explanation for sAD, by which nervous system development could be affected by early immunological deregulations and this would be maintained during the lifetime in a “low inflammatory state.” When aging the low inflammatory state would become higher and this would determine the sAD phenotype. 18 , 20 The second alternative would propose immunological alterations as a secondary downstream phenomenon caused by early affectations of the autonomous (or vegetative) nervous system regulating immunological system. 22 , 25 , 26 Then, a third, combined explanation could also be considered by which there are some connections between the other two proposed 27 or a network between the nervous system and the immune system. 28

3.1.1. Nervous system and immune system interactions

Previous dogma considered the nervous system and immune system as autonomous entities, but now the immune system is conceptualised as an integrated entity within the nervous system as both systems work in coordination in host defense or even other sensory structures of the brain. 28 Many authors suggest that the relationships between the two systems are bidirectional, very complex, but far from completely understood. 26 , 27 , 28 The tight communications between nervous system and immune system appear early in the evolution. The C. elegans elemental nervous system (302 neurons) includes a network of neurons able to aid and control the immunity of this invertebrate. 29 Segner et al reviewed the nervous system (hypothalamus‐hypopituitary reproductive axis)–immune system exchange in vertebrate evolution. 30 From this review it seems clear that the immune system is regulated by the nervous system along the evolution involving all cells related to innate immunity: eg, macrophage, natural killer (NK) cells, and dendritic cells (antigen‐presenting cells) that bridge innate and adaptive immune cells, and the adaptive immunity (T and B lymphocytes) that upon exposure to antigens act as specific immunity. 22 , 30 The relation between nervous system‐immune system may be explained as a bidirectional interaction, as most brain cells (neurons and glial cells) have receptors to cytokines produced by immune cells, and simultaneously immune cells have receptors to neuropeptides, neurotransmitters, and neurohormones, suggesting a common ancestral origin. 31

The nervous system control is clearly delineated at local, regional, and general levels in humans. 22 , 26 This regulation is locally performed by the “axon reflex,” which could be pro‐inflammatory or mitigating the inflammation. At regional and systemic levels, such regulation is mainly made by the autonomous nervous system, which controls all basic vegetative functions excluding the general muscular system. 32 This control is conducted by the sympathetic and parasympathetic (vagal nerve) that could be considered the immune system control “hard wiring,” and by neurohormones through the hypothalamic‐pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis and by neurotransmitters. In general, the nervous system activity promotes the immune system modulation until a homeostatic stable state is obtained. 26 , 28

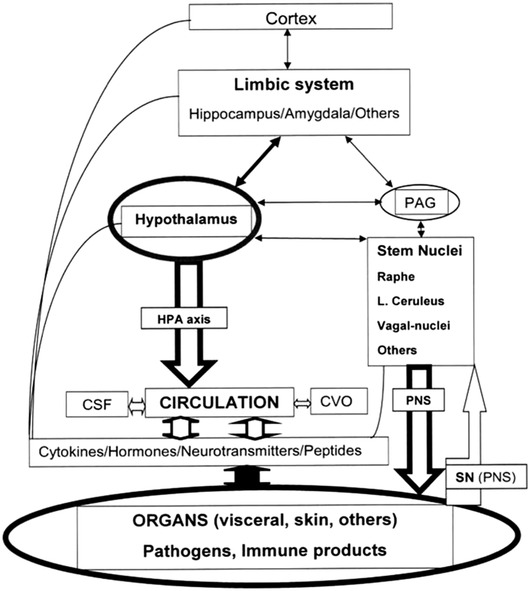

Recently, it has been considered that the third revolution in immunological thinking is the integration role of neurological feedback circuits that regulate the immune system. Axonal reflex is the most simplex determined by the local sensorial neurons without initial participation of the CNS. More complex is the reflex determined by autonomous nervous system (sympathetic, parasympathetic—vagal nerve‐ and enteric parts) integrated in the spinal cord (sympathetic nervous system) and in the brain stem (parasympathetic). 22 The afferent part of these reflexes is established at the local level by the sensorial neurons that sends its branches across the spinothalamic way to the brain stem (medullar and mesencephalon nuclei and network structures) reaching the thalamus. Brain stem structures also receive information from the autonomous nervous system (80% of the vagal nerve is sensorial) regulating basic functions (respiration, the heart, sleep, and immunity). Moreover, it has been suggested that the immunity function could be additionally integrated in the cortex conforming an “immunological homunculus,” with reminiscences from the sensory or motor cortical homunculus 22 (Figure 2). Efferent response in the CNS comes after a complex integration in the subcortical structures (brain stem structures, hypothalamus, and other parts of the limbic system), several thalamic nuclei, and the cortex. Sympathetic and parasympathetic systems (vagal nerve), the HPA hormones, and neurotransmitters mediate the efferent nervous system response. Also, it is well known that the vagal reflex or “inflammatory reflex,” a vagal nerve action (acetylcholine neurotransmission to the immunity cells of the spleen) in a complex interaction with the noradrenergic transmission and lymphocyte neurotransmitters, suppressing excessive inflammation. 26 Along the way, Besedovsky considered that the immune system actually works as a sensory system integrated with the other sensory systems (touch, sight, etc) of the nervous system where not only participate as neuron to neuron synapses but also astrocytes (“tripartite synapsis”) and possibly microglia. 28

FIGURE 2.

Interactions and regulation of nervous and immune systems. This diagram represents the close interaction between the nervous and immune system. The nervous system has many afferences from the immune system: by immune system transmitters: cytokines, peptides, and others, including immune cells (fine lines); the immune cells and their transmitters acceded to nervous system trespassing the blood‐brain barrier by circumventricular organs, capillary diapedesis, and cerebrospinal fluid inter‐neuronal‐glial space; and by nervous impulses via sensory neurons (spinothalamic tract) and peripheral nervous system, autonomous nervous system included (fine open arrow at left bottom). The main effectors of the nervous system to immune system are hypothalamic hormones (mainly by the hypothalamic‐pituitary adrenal axis), and peripheral nervous system (PNS), but also neurotransmitters (descending open bold arrows). Scheme designed with data mainly from references [22] and [25]. Other more complex explanations [28] are not represented

Summarizing, the nervous system decreases immune system overreaction to body insults (pathogens and other stressful situations), trying to re‐establish homeostasis. Locally, sensory neurons could potentiate, or at least modulate, general immune reactions. 26 , 28 Figure 2 further represents the nervous system and immune system interactions.

3.1.2. Sporadic Alzheimer's disease (sAD) preclinical periods

The cognitive decline in AD (familial and sporadic) is very slow, and in most patients is preceded by a clinical predementia state or preclinical sAD. This is known thanks to several survey studies such as the Framingham cohort and other European studies (ie, PAQUID study), which have demonstrated a long preclinical and very subtle cognitive decline. These cognitive changes were only detected in psychometric tests but not by the participants or their relatives. Later on, cognitive decline became apparent and turned to clear MCI or classical AD dementia prior to any clinical appearance. 2 Also, in the last decade of the 20th century, a descriptive pathological data study carried out on a German brain bank confirmed the slow tau neuron skeletal brain alterations above mentioned. 12 The study estimated the evolution of sAD Braak stages in about 16 years from stage I to stage II and around 14 years from stage II to stage III, when the first manifestations of cognitive deterioration appear. 12 Therefore, the most characteristic sAD pathological lesions evolve slowly over decades, in agreement with the clinical observations of subtle memory deterioration decades before the appearance of sAD. More recently, neuroimaging methods corroborated the clinical silent period of tau and Aβ deposition prior to the clinical appearance of sAD 33 (Figure 1). The preclinical period without clear cognitive decrease usually precedes a predementia period sAD. This period had several denominations, but the most commonly utilized was Petersen's MCI, considered an initial stage of AD. Later, it has been demonstrated that MCI could be a precursor of other types of dementia: neurodegenerative diseases (NDD), cerebrovascular, and psychiatric affections, including depression and others. 34 Conclusions from an international working group in a key symposium celebrated in 2003 in Stockholm clearly defined MCI and established different subtypes including the amnesic type, the most frequent form of MCI to be converted into AD. 34 , 35 In the last decade, intensive biomarker studies using CSF and neuroimaging data tried to detect the asymptomatic and MCI phases and established complex definitions of this period prior to sAD. 36 That resulted from the work of two recognized international groups: the National Institute on Aging/Alzheimer Association (NIA‐AA) and the International Working Group for New Research Criteria for the Diagnosis of AD. They have continuously revised several definitions of preclinical AD to perform treatment trials in cognitively asymptomatic people. 36 All these definitions are based on clinical series. The last definition of the NIA‐AA came out in the “biological Alzheimer's” research work only based on biomarkers of Aβ (senile plaques) and tau (neurofibrillary tangles) but not on clinical data. In the last study using a cohort from the Mayo Clinic population‐based registry, it was stated the biological Alzheimer's is overwhelmingly more frequently than the traditional clinically diagnosed sAD. The last prevalence study (three times more in 85‐year‐old people) has shown the discrepancy between the complex “biological definition” of AD and its traditional clinical diagnosis. 37

In summary, in the last two decades, strong evidences has shown that most of sAD cases have a long pre‐symptomatic evolution prior to clinical (MCI or dementia) beginning. A simple scheme of this evolution is shown in Figure 1.

3.1.3. Are there data of immunological alterations along the sAD preclinical periods?

Support for the immunological‐inflammatory cause of sAD is controversial. It is true that long ingestion of anti‐inflammatory medications is associated with low risk of sAD, including sAD mortality data, 38 but the anti‐inflammatory trials have produced negative results. 39 Contrarily, it is known that Down syndrome patients, considered a biological AD model, have a long‐standing decrease in their immunological status supporting the relationship between immunity and sAD. 40

3.1.4. Sporadic Alzheimer's diseases (sAD) and the predementia period, inflammatory and immunological deficits, hypothalamic and limbic lesions

It is not clear that behavioral abnormalities including irritability and depression are precognitive sAD manifestations but a decrease in the body mass index (BMI) and/or sleep disorders may clearly appear prior to any clinical symptoms of cognitive decline.

BMI and sleep alterations might indicate hypothalamic deficits. 41 Several sleep waking alterations have been described in sAD. There are many explanations for these findings described in sAD. Baloyannis et al demonstrated in early‐onset AD cases that several hypothalamic nuclei (suprachiasmatic, supraoptic, and paraventricular) showed pathological hallmarks including reduced neuronal population, dystrophic axons, abnormal Golgi, and synaptic spines without the characteristic AD pathology (neurofibrillary tangles and senile plaques) in these areas. 42 These alterations were present in the hypothalamus of brains from 12 sAD patients with clear sAD clinical pathological diagnosis suggesting that these morphological hypothalamic neuron alterations could appear very early in AD prior to Aβ and tau deposition. 12 Many authors recognize the hypothalamus as the most important autonomous nervous system engine, but others included other limbic structures such as the hippocampus. 27 , 32 Nevertheless, the most clinically detectable precognitive characteristics in AD, BMI decline and sleep alterations, are mainly due to hypothalamic dysfunctions and appear years before cognitive decline. BMI is commonly reduced in older adults, but a number of studies have shown that many years before clinical cognitive decline, sAD patients reported a BMI decline higher than the non‐sAD controls in community‐ and hospital‐based clinical series. 41 Similar findings were observed in preclinical dominant genetic AD where weight decline began one or two decades before clinical AD appearance. 43 Therefore, the origin of these two clinical alterations, BMI and sleep quality, is not well known but the existing data indicate alterations in hypothalamic and limbic structures that may be included as AD precognitive defects, suggest that functions of these brain structures (ie, systemic immunity control), could be affected in this disease at early stages. 22 , 32 , 41

3.1.5. Hypothalamic dysfunctions in sAD may preclude immunity alterations, including salivary lactoferrin

It is well known that sAD evolution is associated with several immunity deficits, although some of them are only evident in late stages of disease. 23 , 24 These impairments may occur during the sAD preclinical stage and probably they facilitate sAD progression according to experimental and clinical findings. 21 Many authors suggest that immune system disturbances associated to sAD may be consequences of nervous system dysfunction determined by hypothalamic lesions. 22 , 27 This opinion is supported by experimental evidence using injured and/or stimulated animal models and probably is based on limbic system lesions (hippocampus, hypothalamus, and several brain stem nuclei), which represents a primitive hub controlling body functions regulated by the autonomous nervous system. 27 , 32 , 41 , 42 The hypothalamus integrates the majority of basic life functions: energy metabolism (feeding); fluid and electrolyte balance (drinking); thermoregulation, fever responses; wake‐sleep cycles; emergency response to stressors; reproduction (mating, pregnancy, birth); 32 and body immunity. 25 , 27 , 28 , 30

The integrated functions of nervous and immune systems could be affected during preclinical and early prodromal sAD, and later on during MCI and dementia stage of sAD, as hypothalamus and limbic structures have early AD lesions leading to loss of the nervous system and immune system homeostasis 26 , 44 (Figure 2). It has been described that the affected nervous system structures in sAD generate an upregulation of brain immunity, 45 and simultaneously a downregulation of the systemic immunity. The elderly decline in systemic immunity, now called “immunosenescency,” is frequently observed in humans 23 , 24 and animals, 46 but its origin is controversial. It is probably associated with hypothalamic functional decay as reported in experimental and human data. 23

In this scenario, we are interested in Lf. Lf is the main protein component in saliva. Lf is a highly conserved polypeptide chain (glycoprotein) contained in most mammalian exocrine secretions as milk, saliva, and tears, and also is found in blood neutrophils. Lf is a pleiotropic protein that could be considered the first line for defense against infections, including periodontal bacteria, and has several immunological properties (see Table 1). 47 , 48 , 49 Saliva is an easily accessible physiological fluid that can be collected in a non‐invasive way. It is well known that saliva has many physiological functions and its protein composition lends many anti‐infections and immunological properties. Because salivary Lf decrease appears early in the sAD development 1 , perhaps due to the early hypothalamic immunity dysregulation in sAD, we propose that Lf could be downregulated in sAD as other aspects of systemic immunity in sAD. For that reason, Lf may be a good biomarker candidate for initial and clinically established sAD. 1 However, further studies are needed to clarify several unresolved questions of importance for being a good sAD biomarker; for example, the fact that Lf is reduced in salivary secretions in AD cases and such reduction is not observed in Parkinson's disease (PD). 1 Although PD is a NDD affecting autonomous nervous system and several brain stem structures, PD alterations do not compromise the same hypothalamic and limbic system structures that are affected in sAD. Moreover, in PD brains main lesions affect early only the mesencephalic dopaminergic neurons. 50 Alternatively, we pointed out that the deficiency of salivary Lf in sAD might facilitate oral bacterial or viral proliferation, inducing periodontal infections, and the expansion of pathogens or their inflammatory products to the nervous system; therefore, it could be a risk factor for sAD. 49

TABLE 1.

Main physiological actions of Lactoferrin

| Physiological actions | Mechanisms |

|---|---|

| Iron‐binding protein | Iron absorption, transport and sequestration |

| Host defence |

Activities against pathogens: antibacterial, antifungal, antiparasitic, antiviral Anti‐inflammatory and alarming Anti‐endotoxin Anticancer Inhibition of prion accumulation |

| Host activities |

Brain development and neuroprotection: alleviating psychological stress Bone formation Gastrointestinal development Immune actions (innate and adaptive): enhancer and modulator Wound healing |

| Metabolic |

Adipocytes differentiation Antioxidant: inhibiting lipid peroxidation Association with other proteins: osteopontin and others Decreasing vasoconstriction Enzymatic activities Glucose regulation (decreasing hyperglycemia) Gut microbiota modulation Transcriptional regulator |

| Miscellaneous |

Compounds or metabolites carrier (mainly into brain) Vaccine adjuvant Possible sAD biomarker |

3.2. Future experiments and validation studies

It would be desirable to determine whether the reported reduction of salivary Lf levels in sAD in our study will be confirmed in new research and particularly in population‐based studies. Our published study was carried out using MCI and AD cases clinically evaluated compared to healthy age‐matched controls; therefore, we consider it would be relevant to determine Lf levels in population‐based elderly cohorts to obtain more unbiased results. It will be useful to study the specificity of salivary Lf decrease in sAD, by analyzing the levels of this protein in other NDD such as PD and frontotemporal dementia (FTD). We consider these analyses very important because these two NDD are the main differential diagnostic entities from sAD. It is possible salivary Lf levels in these two NDD other than sAD remain unchanged compared to healthy subjects as brain structures in these diseases are different from those in AD: mesencephalic dopaminergic neurons in PD and cortical structures in FTD. In line with the specificity determination of salivary Lf, compared to other dementias, it would also be important to analyze salivary Lf in “pure” vascular dementia. On the other hand, salivary Lf determination in genetic AD and Down syndrome cases would also be important to fulfil the salivary Lf evaluation. Additionally, investigation of salivary Lf regulation and function in experimental animals (transgenic mice) carrying the human genetic AD mutations could confirm the early affectation.

4. MAJOR CHALLENGES FOR THE HYPOTHESIS

The major challenge of the Lf hypothesis as early biomarker of sAD is the confirmation of our results in other clinical cohorts and/or population‐based studies. The utility of Lf salivary determination in the elderly is based on our very good diagnostic capacity of Lf in early phase of clinical sAD (MCI and clinical apparent sAD dementia). It would be necessary to discard the reduction of salivary Lf levels as consequence of unknown mechanisms other than related to immunological modulation. Confirmation of our hypothesis would determine salivary Lf would be an easy and cheap biomarker that could be included in the biomarker's armamentarium of sAD.

5. LINKAGE TO OTHER MAJOR THEORIES

This hypothesis could be in agreement with the most accepted pathophysiological views of sAD. Salivary Lf decrease could be a downstream phenomenon consequence of early hypothalamic lesions and autonomous nervous system dysfunction in sAD. 22 , 27 , 32 , 44 The alternative hypothesis, the great pathophysiological importance of early low neuroinflammation and immunity impairments in the genesis and risk prolongation of sAD 18 , 20 that could be aggravated in the very elderly (“inflamm‐aging”) 23 , 24 adequately coupled with our findings. Our study agrees with the hypothesis that immune alterations and brain infections might play an initial role in the development of AD pathology. In this context, antimicrobial peptides, such as Lf, may control this dissemination to the brain. Thus, salivary Lf reduction may represent a reduced oral protection, exacerbating the risk of AD. It is obvious that in our opinion this alternative theory of the sAD genesis needs more observational and experimental data to overcome the traditional clinical‐pathological explanation of the sAD phenotype. Moreover, both explanations could interplay to explain our findings because the relationships between the nervous system and the immune system are tight and bidirectional. 27 , 28

This study was supported by grants from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (FIS15/00780, FIS18/00118), FEDER, Comunidad de Madrid (S2017/BMD‐3700; NEUROMETAB‐CM), and CIBERNED (PI2016/01).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Bermejo‐Pareja F, del Ser T, Valentí M, de la Fuente M, Bartolome F, Carro E. Salivary lactoferrin as biomarker for Alzheimer's disease: Brain‐immunity interactions. Alzheimer's Dement. 2020;16:1196–1204. 10.1002/alz.12107

[Correction added on June 24, 2020, after first online publication: A sentence was corrected in “Linkage to Other Major Theories” within the Abstract and in “Research in Context.”]

Contributor Information

Fernando Bartolome, Email: fbartolome.imas12@h12o.es.

Eva Carro, Email: carroeva@h12o.es.

REFERENCES

- 1. Carro E, Bartolome F, Bermejo‐Pareja F, et al. Early diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease based on salivary lactoferrin. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2017;8:131‐138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bermejo‐Pareja F. Alzheimer: Prevention from Childhood. Germany: LAP Lamberth Academic Publishing; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Naj AC, Schellenberg GD. Genomic variants, genes, and pathways of Alzheimer's disease: An overview. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2017;174:5‐26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Morris JK, Honea RA, Vidoni ED, Swerdlow RH, Burns JM. Is Alzheimer's disease a systemic disease? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1842:1340‐1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pedersen NL, Gatz M, Berg S, Johansson B. How heritable is Alzheimer's disease late in life? Findings from Swedish twins. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:180‐185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Medina M, Khachaturian ZS, Rossor M, Avila J, Cedazo‐Minguez A. Toward common mechanisms for risk factors in Alzheimer's syndrome. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;3:571‐578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bennett DA, Yu L, Yang J, Srivastava GP, Aubin C, De Jager PL. Epigenomics of Alzheimer's disease. Transl Res. 2015;165:200‐220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Xu W, Tan L, Wang HF, et al. Meta‐analysis of modifiable risk factors for Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2015;86:1299‐1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Satizabal CL, Beiser AS, Chouraki V, Chene G, Dufouil C, Seshadri S. Incidence of dementia over three decades in the Framingham Heart Study. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:523‐532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Drachman DA. The amyloid hypothesis, time to move on: amyloid is the downstream result, not cause, of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10:372‐380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Moir RD, Lathe R, Tanzi RE. The antimicrobial protection hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14:1602‐1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Braak H, Del Trecidi K. Neuroanatomy and pathology of sporadic Alzheimer's disease. Adv Anat Embryol Cell Biol. 2015;215:1‐162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stratmann K, Heinsen H, Korf HW, et al. Precortical phase of Alzheimer's disease (AD)‐related tau cytoskeletal pathology. Brain Pathol. 2016;26:371‐386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. de la Torre J. Alzheimer's Turning Point. A vascular Approach to Clinical Prevention. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing AG; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Whitehouse PJ , George D. The Myth of Alzheimer's. What You Aren't Being Told About Today's Most Dreaded Diagnosis. New York: St. Martin's Griffin Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cubinkova V, Valachova B, Uhrinova I, et al. Alternative hypotheses related to Alzheimer's disease. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2018;119:210‐216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Whalley L. Understanding Brain Aging and Dementia: A Life Course Approach. New York: Columbia University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Knuesel I, Chicha L, Britschgi M, et al. Maternal immune activation and abnormal brain development across CNS disorders. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10:643‐660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gendelman HE, Mosley RL. A Perspective on Roles Played by Innate and Adaptive Immunity in the Pathobiology of Neurodegenerative Disorders. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2015;10:645‐650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Eikelenboom P, Veerhuis R, van Exel E, Hoozemans JJ, Rozemuller AJ, van Gool WA. The early involvement of the innate immunity in the pathogenesis of late‐onset Alzheimer's disease: neuropathological, epidemiological and genetic evidence. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2011;8:142‐150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gao HM, Hong JS. Why neurodegenerative diseases are progressive: uncontrolled inflammation drives disease progression. Trends Immunol. 2008;29:357‐365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pavlov VA, Chavan SS, Tracey KJ. Molecular and Functional Neuroscience in Immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2018;36:783‐812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kim K, Choe HK. Role of hypothalamus in aging and its underlying cellular mechanisms. Mech Ageing Dev. 2019;177:74‐79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vida C, Martinez de Toda I, Garrido A, Carro E, Molina JA, De la Fuente M. Impairment of Several Immune Functions and Redox State in Blood Cells of Alzheimer's Disease Patients. Relevant Role of Neutrophils in Oxidative Stress. Frontiers in immunology. 2017;8:1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Haas HS, Schauenstein K. Neuroimmunomodulation via limbic structures–the neuroanatomy of psychoimmunology. Prog Neurobiol. 1997;51:195‐222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sternberg EM. Neural regulation of innate immunity: a coordinated nonspecific host response to pathogens. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:318‐328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wrona D. Neural‐immune interactions: an integrative view of the bidirectional relationship between the brain and immune systems. J Neuroimmunol. 2006;172:38‐58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Besedovsky HO. The immune system as a sensorial system that can modulate brain functions and reset homeostasis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2019;1437:5‐14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhang X, Zhang Y. Neural‐immune communication in Caenorhabditis elegans. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:425‐429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Segner H, Verburg‐van Kemenade BML, Chadzinska M. The immunomodulatory role of the hypothalamus‐pituitary‐gonad axis: Proximate mechanism for reproduction‐immune trade offs? Dev Comp Immunol. 2017;66:43‐60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kioussis D, Pachnis V. Immune and nervous systems: more than just a superficial similarity? Immunity. 2009;31:705‐710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wehrwein EA, Orer HS, Barman SM. Overview of the Anatomy, Physiology, and Pharmacology of the Autonomic Nervous System. Compr Physiol. 2016;6:1239‐1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Habib M, Mak E, Gabel S, et al. Functional neuroimaging findings in healthy middle‐aged adults at risk of Alzheimer's disease. Ageing Res Rev. 2017;36:88‐104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Winblad B, Palmer K, Kivipelto M, et al. Mild cognitive impairment–beyond controversies, towards a consensus: report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Intern Med. 2004;256:240‐246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bermejo‐Pareja F, Contador I, Trincado R, et al. Prognostic Significance of Mild Cognitive Impairment Subtypes for Dementia and Mortality: Data from the NEDICES Cohort. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;50:719‐731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Khachaturian ZS, Mesulam MM, Mohs RC, Khachaturian AS. Toward a consensus recommendation for defining the asymptomatic‐preclinical phases of putative Alzheimer's disease? Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12:213‐215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jack CR Jr., Therneau TM, Weigand SD, et al. Prevalence of Biologically vs Clinically Defined Alzheimer Spectrum Entities Using the National Institute on Aging‐Alzheimer's Association Research Framework. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(10):1174‐1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Benito‐Leon J, Contador I, Vega S, Villarejo‐Galende A, Bermejo‐Pareja F. Non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs use in older adults decreases risk of Alzheimer's disease mortality. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0222505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Heneka MT, Carson MJ, El Khoury J, et al. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's disease. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:388‐405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kusters MA, Verstegen RH, Gemen EF, de Vries E. Intrinsic defect of the immune system in children with Down syndrome: a review. Clin Exp Immunol. 2009;156:189‐193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ishii M, Iadecola C. Metabolic and Non‐cognitive manifestations of Alzheimer's disease: the hypothalamus as both culprit and target of pathology. Cell Metab. 2015;22:761‐776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Baloyannis SJ, Mavroudis I, Mitilineos D, Baloyannis IS, Costa VG. The hypothalamus in Alzheimer's disease: a Golgi and electron microscope study. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2015;30:478‐487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Muller S, Preische O, Sohrabi HR, et al. Decreased body mass index in the preclinical stage of autosomal dominant Alzheimer's disease. Sci Rep. 2017;7:1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Goldstein DS, Kopin IJ. Homeostatic systems, biocybernetics, and autonomic neuroscience. Auton Neurosci. 2017;208:15‐28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kawamata T, Tooyama I, Yamada T, Walker DG, McGeer PL. Lactotransferrin immunocytochemistry in Alzheimer and normal human brain. Am J Pathol. 1993;142:1574‐1585. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Peters A, Delhey K, Nakagawa S, Aulsebrook A, Verhulst S. Immunosenescence in wild animals: meta‐analysis and outlook. Ecol Lett. 2019;22:1709‐1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kruzel ML, Zimecki M, Actor JK. Lactoferrin in a context of Inflammation‐Induced Pathology. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mayeur S, Spahis S, Pouliot Y, Levy E. Lactoferrin, a Pleiotropic Protein in health and disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2016;24:813‐836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Leira Y, Dominguez C, Seoane J, et al. Is Periodontal disease associated with Alzheimer's disease? A systematic review with meta‐analysis. Neuroepidemiology. 2017;48:21‐31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Braak H, Del Tredici K. Neuroanatomy and pathology of sporadic Parkinson's disease. Adv Anat Embryol Cell Biol. 2009;201:1‐119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]