Abstract

The influx of sodium (Na+) ions into a resting cell is regulated by Na+ channels and by Na+/H+ and Na+/Ca2+ exchangers, whereas Na+ ion efflux is mediated by the activity of Na+/K+‐ATPase to maintain a high transmembrane Na+ ion gradient. Dysfunction of this system leads to changes in the intracellular sodium concentration that promotes cancer metastasis by mediating invasion and migration. In addition, the accumulation of extracellular Na+ ions in cancer due to inflammation contributes to tumor immunogenicity. Thus, alterations in the Na+ ion concentration may potentially be used as a biomarker for malignant tumor diagnosis and prognosis. However, current limitations in detection technology and a complex tumor microenvironment present significant challenges for the in vivo assessment of Na+ concentration in tumor. 23Na‐magnetic resonance imaging (23Na‐MRI) offers a unique opportunity to study the effects of Na+ ion concentration changes in cancer. Although challenged by a low signal‐to‐noise ratio, the development of ultrahigh magnetic field scanners and specialized sodium acquisition sequences has significantly advanced 23Na‐MRI. 23Na‐MRI provides biochemical information that reflects cell viability, structural integrity, and energy metabolism, and has been shown to reveal rapid treatment response at the molecular level before morphological changes occur. Here we review the basis of 23Na‐MRI technology and discuss its potential as a direct noninvasive in vivo diagnostic and prognostic biomarker for cancer therapy, particularly in cancer immunotherapy. We propose that 23Na‐MRI is a promising method with a wide range of applications in the tumor immuno‐microenvironment research field and in cancer immunotherapy monitoring.

Level of Evidence

2

Technical Efficacy

Stage 2

Keywords: magnetic resonance imaging, biomarker, sodium, immunotherapy, prognosis, tumor micro‐environment, neoplasm

ALTERATIONS IN CELL MEMBRANE INTEGRITY cause dysfunction of transmembrane proteins involved in sodium (Na+) ion transport, which includes the sodium/potassium adenosine triphosphatase (Na+/K+‐ATPase), sodium/hydrogen exchanger 1 (NHE1), sodium/calcium exchanger (NCX), and sodium channels. The expression and function of these transmembrane proteins are altered in several tumor types, resulting in intracellular sodium concentration (ISC) changes. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8

Recently, it has been demonstrated that increased ISC promotes cellular behaviors such as invasion, migration, and endocytosis involved in metastasis, 2 , 3 , 9 , 10 , 11 (Table 1). For instance, upregulation of voltage‐gated sodium channel (VGSC) expression, often observed in malignant cells, is associated with an increase in inward, and reduction in outward, sodium currents, 11 showing that Na+/K+‐ATPase activity, and therefore cell integrity, are compromised. VGSC has therefore been suggested to be partially opened in metastasized cells, 11 resulting in a constant influx of Na+ ions that disrupts the transmembrane Na+ ion gradient and signaling pathways downstream (Table 1). Hence, significant research efforts have been invested in investigating the possibility of using Na+ ion transporters as anti‐metastatic targets 12 , 13 , 14 (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Voltage‐Gated Sodium Channels (VGSC) and Sodium Proton Exchanger 1(NHE1) Expression, Function, and Potential Inhibitors in Cancer

| Cancer Type | Sample | Protein | Function | Regulator | Pathway | Target | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast | Breast cancer cells | Nav1.5 | Enhance invasion | EGF | PI3K – dependent signaling | — | 107 |

| Weakly metastasized MCF‐7 | nNav1.5, Nav1.6, Nav1.7 | — | — | — | — | 6 | |

| Strongly metastasized MDA‐MB‐231 |

nNav1.5 upregulated Nav1.6, Nav1.7, |

Enhances motility, endocytosis' and invasion | — | — | — | 6 | |

| Primary culture of human Breast cancer | nNav1.5 upregulated | Promote cancer progression | — | — | — | 6 | |

| Strongly metastasized MDA‐MB‐231 | Inward current | Enhances invasion | — | — | — | 7 | |

| MDA‐MB‐231, MDA‐MB‐468 | NHE1‐ inhibition | Significantly reduced migration, invasion and anchorage‐independent colony growth | — | — | (μM) KR‐33028 | 13 | |

| Prostate | PC‐3 M cell line | VGSC Nav1.7 upregulated | Enhances tumor cells' migration, endocytosis' and invasion | EGF | — | — | 108 |

| Mat‐LyLu cells | VGSC ‐ inhibition | Inhibited lung metastasis | — | — | (μM) ranolazine | 12 | |

| Mat‐LyLu cells | VGSC ‐ inhibition | Down‐regulates Nav1.7 expression, reducing cell movement and metastasis | — | — | (μM) Naringenin | 14 | |

| Cervical and ovarian | ME180 cells | VGSC Nav1.6 upregulated | Enhance invasion | VEGF‐C | p38 MAPK signaling | — | 109 |

| C33A cells | VGSC Nav1.6 upregulated | Enhance invasion which involves MMP‐2 activity. | — | — | — | 2 | |

| Lung | H460 NSCLC | VGSC Nav1.7 upregulated | Enhance invasion | EGF | ERK1/2 signaling | — | 110 |

| H510 SCLC | Nav1.3, Nav1.5, Nav1.6, Nav1.9 | Promote endocytic membrane activity | — | — | — | 10 | |

| Colon | Patient biopsies, SW620, SW480, HT29 cell lines | VGSC Nav1.5 | Promotes invasion | — | ERK1/2 MAPK signaling | — | 9 |

| Gastric | Patients and tissue samples, BGC‐823, MKN‐28 cells | VGSC Nav1.7 upregulated | promotes progression through MACC1‐mediated upregulation of NHE1 | — | P38 signaling | — | 1 |

| patient biopsies, GES‐1, SGC‐7901 and MKN‐45 cells lines | NHE1‐upregulated | Enhance tumor cell proliferation promote migration and invasion through epithelial‐mesenchymal transition (EMT) proteins | — | — | — | 4 | |

| Brain | Primary human glioma cells, glioma xenografts and glioblastoma | NHE1‐inhibition | Combining temozolomide (TMZ) therapy with NHE1 inhibition suppresses GC migration and invasion, and also augments TMZ‐induced apoptosis | — | — | HOE 642 (cariporide) | 111 |

| Glioma models (SB28, GL26). | NHE1 ‐inhibition | NHE1 inhibition reduced glioma volume, invasion, and prolonged overall survival in mouse glioma models | — | — | HOE 642 (cariporide) | 104 | |

| Fibrosarcoma | HT‐1080 | NHE1 | Invadopodia formation | Hypoxia | p90RSK signaling | — | 112 |

In normal tissues, the ISC is ~10–15 mM, with a cell volume fraction (CVF) of 0.8 and is regulated by the Na/K‐ATPase, sodium channels, and exchangers. On the other hand, the extracellular sodium concentration (ESC) is ~140–150 mM, occupies an extracellular volume fraction (EVF) of 0.2, and is maintained by the blood pool and kidney. 15 Tissue sodium concentration (TSC) describes the distribution of Na+ ions in tissues and is calculated as follows 15 :

| (1) |

Increased TSC may result from compromised cell integrity (higher ISC) or from an increased interstitial space (EVF) due to tumor revascularization, necrosis, and/or apoptosis. 15 Inflammation, which plays an essential role in tumorigenesis, increases with ESC and hence osmolarity. Consequently, elevated osmotic stress due to inflammation promotes revascularization through the activation of macrophages, which secrete VEGF‐C to stimulate angiogenesis, resulting in increased EVF. 16 Increased ESC has also been demonstrated to prolong macrophage half‐life and also promote proinflammatory cytokine secretion, including interleukins and tumor necrotic factor‐alpha. 17 Again, in an increased ESC environment, there is also a potential reduction of antigen presentation capacity due to the possible induction of the peripheral macrophages to activate the anti‐inflammatory M2 phenotype with poor phagocytic efficiency, 18 suspected to promote tumor progression and tumor immune escape.

Nevertheless, given the limitations of the current technology, the assessment of in vivo and ex vivo Na+ ion concentrations in the tumor microenvironment remains challenging. ex vivo quantification of intracellular Na+ ions is usually performed using small‐molecule fluorescence probes with high selectivity and affinity for Na+ ions over other ions, especially K+. 19 , 20 However, the loading of these probes into live cells is difficult due to their bulky nature. Moreover, as they require short excitation wavelengths, which have very short penetration depth and high cellular autofluorescence, the application of Na+‐specific fluorescence probes in tissue imaging is limited. 20 Thus, although small‐molecule fluorescence probes are used extensively in real‐time imaging, they are unsuitable for detecting changes in Na+ ion concentration in the complex tumor microenvironment, particularly during therapy, due to its limitations in intact tissue imaging.

Alternatively, 23Na‐MRI offers a unique opportunity for accurately assessing in vivo the temporal and spatial dynamics of Na+ ions in tumors. This imaging technique complements proton magnetic resonance imaging (1H‐MRI) by providing direct quantitative biochemical information and enabling rapid in vivo visualization of the distribution of Na+ ion concentrations in tissues. Moreover, the limitations of 23Na‐MRI, such as low signal‐to‐noise ratio (SNR), poor spatial resolution, and long acquisition time, have been circumvented to a large extent by the development of ultrahigh magnetic field scanners, double‐tuned radiofrequency (RF) coils, specialized acquisition sequences, and improved software. These technical advances have allowed the generation of quantitative parameters (ISC, TSC, and EVF) (Table 2) that provide information essential for pathological diagnosis and prognosis. 21 In this review, we provide insights into the basis of 23Na‐MRI and discuss its potential as a direct noninvasive in vivo diagnostic and prognostic imaging biomarker for cancer therapy, as presented graphically in (Fig. 1).

TABLE 2.

Range of Observed Mean Tissue Sodium Concentration (TSC) and Intracellular Sodium Concentration (ISC) for Normal and Specific Cancer Tissues at Different Magnetic Field Strength

| Tissue | Therapy | Sample size | Mean TSC (mM) | Mean ISC (mM) | Field strength (T) | Acquisition sequence | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal rat brain | — |

Fisher rat N = 5 |

45 ± 4 | — | 4.7T | 3D radial projection | 35 |

| Normal rat brain | — | Fisher rat N = 3 | 44.4 ± 3.7 | — | 21.1T | 3D back‐projection | 113 |

| Rat glioma | Radiotherapy | Fisher rat N = 13 N = 4 | Treated: 65 ± 12 Untreated: 55 ± 3 | — | 3.0T | Twisted projection pulse sequence (TPI) | 41 |

| Normal human brain | — | Healthy volunteers N = 12 | Gray matter:51.5 ± 4.5 White matter: 40.9 ± 3.8 | — | 3.0T | 3D density‐adapted projection reconstruction | 70 |

| Normal human brain | — | Healthy volunteers N = 11 | –––– | Full brain:12.56 Gray matter:11.41 White matter:13.59 | 3.0T | FLORET sequence | 71 |

| Normal human brain | — | Healthy volunteers N = 11 | Gray matter: 52.1 ± 7.1 White matter: 41 ± 6.7 | — | 3.0T | 3D‐Cones | 72 |

| Human glioma | — | Patients N = 20 | Tumor: 103 ± 36 Gray matter: 61 ± 9 White matter: 71 ± 13 | — | 1.5T | 3D twisted‐projection imaging sequence | 57 |

| Neuroblastoma | — |

Nude mice N = 29 |

87 ± 29 | — | 1.9T | 3D multiple echo pulse sequence | 114 |

| Human glioma | ––––‐ | Patients N = 8 | Tumor: 59.21 ± 11.19White matter: 30.30 ± 3.53 | Tumor: 12.2 ± 5.89White matter: 10.47 ± 3.05 | 3.0T | FLORET (TSC sequence)FLORET with fluid suppression by inversion recovery (IR): (ISC sequence) | 58 |

| Glioma | ––––‐ | Patients N = 10 | IDH mutation: 58.7 ± 10.4IDH wild type:40.5 ± 24.0 | — | 4.0T | Simultaneous single quantum‐ and triple quantum‐filtered imaging of 23Na (SISTINA) sequence | 59 |

| Breast cancer | Preoperative systemic therapy | Patients N = 6 |

Responders Baseline: 55.2 Treatment:43

Non‐responders Baseline: 56.2 Treatment: 58.1 |

— | 1.5T | A modified projection imaging sequence | 67 |

| Breast cancer | Preoperative systemic therapy |

Patients N = 18 |

Responders Baseline: 66 ± 18 Treatment:48.4 ± 8 Non‐responders Baseline: 51.7 ± 7.6 Treatment: 56.5 ± 1.6 |

— | 1.5T | Projection imaging sequence | 68 |

| Breast cancer | –— |

Patients N = 4 |

Tumor: 47 ± 12 Glandular tissue: 28 ± 4 Fatty tissue:20 ± 2 |

— | 1.5T |

Twisted Projection Imaging (TPI) Sequence |

85 |

| Breast cancer | — |

Patients N = 17 |

Tumor Malignant:69 ± 10 Benign:47 ± 8

Normal tissue Glandular:35 ± 3 Adipose:18 ± 3 |

— | 7T | acquisition‐weighted stack of spirals sequence | 86 |

| Breast cancer | — |

Patients N = 22 |

Tumor Lesion: 53 ± 16

Normal tissue Glandular:34 ± 13 Adipose:16 ± 14 |

— | 1.5T | Twisted projection imaging sequence | 87 |

| Prostate cancer | — |

Patients N = 15 |

Tumor Peripheral zone: 45.0 Normal Peripheral zone: 39.2 Transition zone:32.9 |

Tumor Peripheral zone: 19.9 Normal Peripheral zone:17.5 Transition zone:11.7 |

3.0T |

3D‐Cones (TSC)

inversion recovery sequences (ISC) |

79 |

| Prostate cancer | — |

Patients N = 8 |

Tumor:46.6 Normal Peripheral zone: 39.2 Transition zone:33.9 |

— | 3.0T | 3D‐Cones | 81 |

| High grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSOC) | — |

Patients N = 12 |

Tumor: 56.8 ± 19.1 Skeletal muscle:33.2 ± 16.3 | Tumor: 30.8 ± 9.2 Skeletal muscle:20.5 ± 9.9 | 3.0T | 3D‐Cones (TSC) inversion recovery (ISC) | 31 |

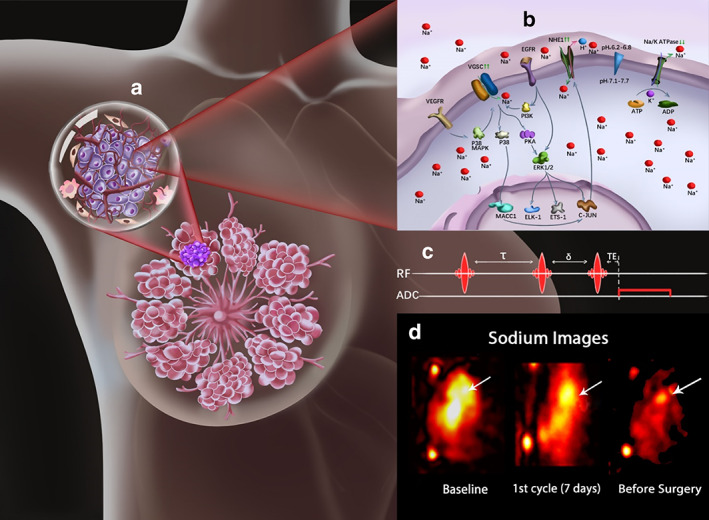

FIGURE 1.

23Na‐MRI as an imaging biomarker in cancer. The intracellular accumulation of sodium promotes metastasis through the upregulation (↑↑) of the voltage‐gated sodium channels (VGSC) and sodium hydrogen exchanger 1 (NHE1) as shown in the breast lesion and its projected tumor cell (a,b). Where b presents the pathways controlling VGSC upregulation (↑↑) through receptors such as EGFR via PI3K or VEGFR via P38MAPK resulting in the influx of Na+ ions. Other pathways also control transcriptional activities, where the upregulated VGSC induce alterations in invasion related gene expression through PKA/ERK activities with positive feedback and/or through MACC1 mediated upregulation of NHE1. Na/K ATPase is indicated to be downregulated (↓↓) in cancer cells, which results in its inability to pump out the accumulated intracellular Na+ ions. The application of UTE 23Na‐MRI (c) generates sodium images, with the arrows pointing to the tumor location (d). 68 These images enable the visualization of the spatial and temporal dynamics of in vivo sodium that characterize lesions by reflecting cell viability, tumor cellularity, metabolism, ion homeostasis, and treatment response.

Basis of 23Na‐MRI Techniques

The 23Na isotope has a quadrupole nucleus (spin 3/2), a gyromagnetic ratio of ~26.4%, and receptivity of 9.25 × 10−2 relative to 1H, and its MR signal strength in biological tissues is comparable to that of 1H. The 23Na nucleus undergoes a Zeeman effect in the presence of a static magnetic field, producing four energy states with a total angular momentum of j = 3/2; j = 1/2, and three possible transitions between these energy states. The central transition (1/2 ↔ −1/2) comprises about 40% of the 23Na signal, whereas the two outer satellite transitions (3/2 ↔ −1/2, −1/2 ↔ −3/2) each contain 30% of the signal. These transitions decay rapidly due to the interaction between the electric quadrupole moment of the 23Na nucleus and the surrounding electric field gradient and macromolecules, resulting in biexponential transverse relaxations with short relaxation times. 22 Signal loss due to these short relaxation times (T2long = 14–30 msec and T2short = 0.5–5 msec T1 = 10–40 msec) and to the low in vivo sodium ion concentration have direct consequences on SNR, resolution, and quantitative 23Na‐MRI accuracy. 23 However, these limitations can be controlled by using optimized imaging sequences, such as the ultrashort echo time (UTE) sequence. UTE sequences are non‐Cartesian k‐space (the spatial frequency domain in which the MR image data are acquired and stored) sampling methods, which exclude the phase‐encoding step required in the conventional Cartesian sampling method, permitting the acquisition of data immediately after the application of the RF pulse. 24 Thus, it reduces the echo time, allowing the acquisition of most of the signal due to the T2 short relaxation time, thereby increasing the SNR. The acquired image data are mostly reconstructed using the gridding algorithm, which first performs sampling density compensation before the Inverse Fourier Transform. 24 Another promising reconstruction technique, which is currently under study and yet to be adopted for clinical applications, is the sparse image reconstruction, which includes the compressed‐sensing reconstruction. 25 , 26 It is based on the notion that the MR image data can be compressed, since it contains some redundant information. Therefore, when the undersampling is performed in a way to capture the essential image information, the speed of image data acquisition and spatial resolution can be increased significantly. 27 Examples of UTE sequences include the 3D radial projection sequence, 28 which is the conventional k‐space sampling method for UTE. However, more advanced UTE sequences such as density adapted radial sequence, 29 twisted projection imaging, 30 3D cones, 31 , 32 and FLORET 33 , 34 result in an increased SNR and reduced blurring. Minimizing the readout bandwidth (5000 Hz) within a limit that T2 short decays slower than the dephasing induced by the readout gradient over a voxel further improves SNR and reduces blurring. 35

Additionally, current static magnets with ultrahigh magnetic field (UHF) strength (≥3T) have greatly improved sensitivity, specificity, and image resolution for 23Na‐MRI. 36 These achievements have been attained due to the linear relationship between SNR and B0.

Moreover, the increased strength and performance of gradient coils to meet the demand of UHF MRI have also contributed to a faster acquisition speed. 37 Notably, this reduction in acquisition time makes 23Na‐MRI particularly attractive for clinical applications.

Quantitative 23Na‐MRI

To ensure accurate quantitative 23Na‐MRI, parameters that influence the sodium signal intensity should be computed and corrected. Such parameters include but are not limited to the partial volume effect (PVE), static magnetic field (B0), and RF field (B1) inhomogeneity corrections. An overview of the evaluation and correction methods of these parameters is presented in the following subsections.

Partial Volume Effect and Correction

In biological tissues, 23Na‐MRI is limited by lower SNR and poor spatial resolution compared to 1H‐MRI. This is due to its low concentration in biological tissues (C = 2000 times lower than 1H), nuclear spin quantum number , and gyromagnetic ratio (γ = 70.761 × 106 rad. S−1. T−1), which can be related as:

| (2) |

based on Eq. (2) it can be implied that the reduced sensitivity of the 23Na nuclei in tissue is partly due to its relatively low gyromagnetic ratio and concentration, which is not entirely compensated for by the 3/2 quadrupolar nucleus. Hence, the relative signal of the 23Na nucleus is in the range of 10−4 to 10−5, depending on its concentration in the organ or tissue of interest. 38 As a result, large voxel volume is often required during imaging to achieve a desirable SNR. However, this results in poor resolution and consequently partial volume effects (PVEs). In brief, full‐width at half maximum (FWHM) of the point spread function (PSF) is a property of the image acquisition sequence. The pulse sequence that permits the use of UTE is encouraged for 23Na‐MRI due to its short relaxation times. These pulse sequences, which employ a non‐Cartesian readout, have large FWHM of the corresponding PSF relative to the Cartesian sampling methods. Also, the broadening of the PSF is encountered due to the short T2 relaxation and the use of reconstruction filters. The combination of these factors leads to PVEs that affect the accuracy of quantitative 23Na‐MRI, especially in small volumes and structures. 39 The partial volume correction (PVC) algorithm for geometric transfer matrix (GTM) 40 used for PVC in positron emission tomography (PET) data performed very well upon its application in quantitative 23Na‐MRI (Fig. 2), and hence can be adopted for such purposes in 23Na‐MRI. However, this PVC method requires high‐resolution anatomical data for optimal performance. 39 Since the use of poor anatomical data leads to inaccurate registration and segmentation, resulting in a not fully corrected PVE.

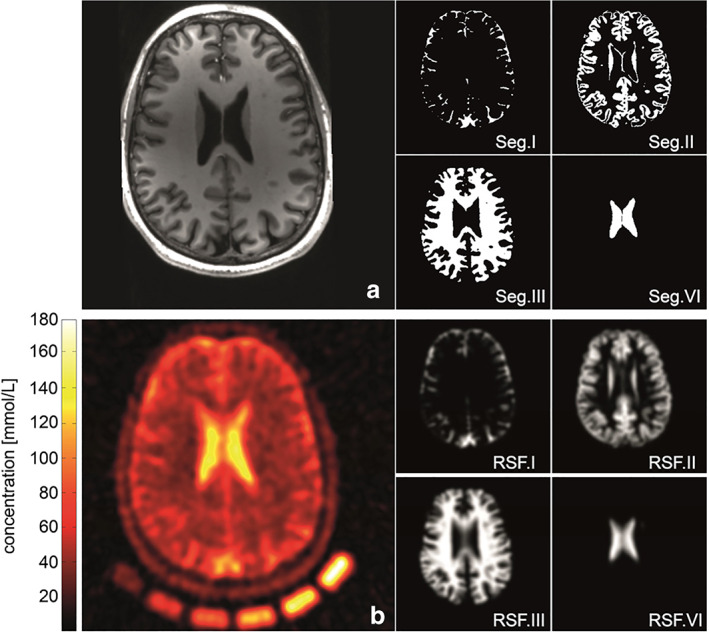

FIGURE 2.

Anatomical information (a) coregistered to quantitative sodium image (b) normalized by means of the external calibration cushion (nominal spatial resolution: (3 mm3), 3600 projections, TR = 200 msec, TE = 0.35 msec; a Hamming‐filter was used to reduce Gibbs ringing artifacts and to gain SNR (reduced shown FOV of 220 × 220 × 220 mm3). MPRAGE (a) and a CISS sequence were acquired to derive tissue masks. Segmentation was performed using the FSL toolkit (Jenkinson and Smith, 2001). The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) volume was divided into two separate compartments to enable an intrinsic correction control of the performed PVC. Example slices of used 3D‐segmentation masks used in the correction algorithm: (Seg.I) of outer CSF, (Seg.VI) inner CSF volume, (Seg.II) gray matter, and (Seg.II) white matter. Corresponding region spread function (RSFs) for the single compartments (RSF.I–RSF.IV). The calculated broadening of the single compartments is in good agreement with the observed blurring in the measured sodium image. Reproduced from Ref. 39 with permission from Elsevier, Neuroimage.

B1 and B0 Field Inhomogeneities Correction

The B1 field distribution at the sodium frequency can be mapped using the double angle method (DAM) or the phase‐sensitive method (PSM). DAM is the most commonly used method for B1 correction, where two sodium images (I1 and I2) are acquired with flip angles I1 = α = 45° and I2 = 2α = 90° from a large phantom that fills the whole RF coil volume and contains a known standard sodium concentration. 41 , 42 The actual flip angle (αactual) can be evaluated as:

| (3) |

B1 correction is then achieved by multiplying the 23Na signal intensity by the correction factor fB1;

| (4) |

where FA is the flip angle at which the TSC image of interest was acquired. However, under low SNR conditions, as observed in 23Na imaging, PSM has been demonstrated to have better performance compared to DAM over a wide range of flip angles 43 (Fig. 3). This B1 mapping technique is based on the phase difference of two images acquired with flip angle 2α along the x‐axis, followed by a flip angle α along the y‐axis. The actual flip angle (αactual) can be evaluated as:

| (5) |

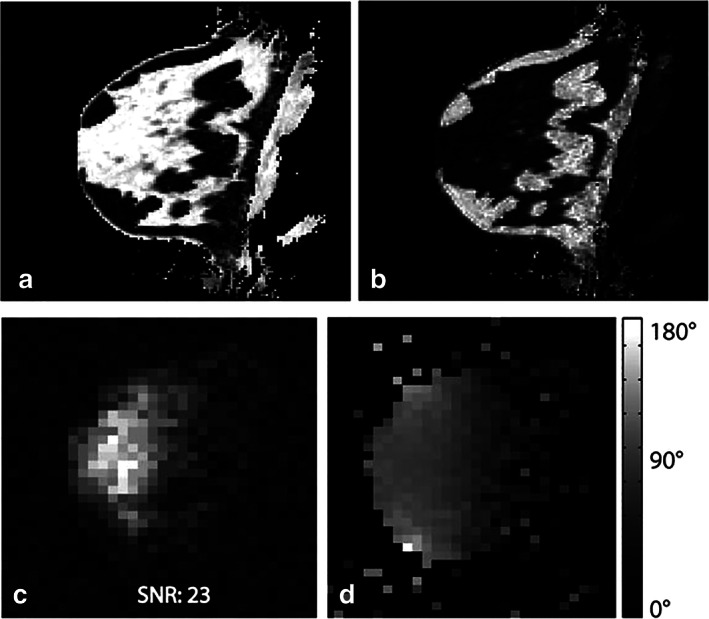

FIGURE 3.

Proton three‐point Dixon water (a) and fat (b) image of the breast of a healthy volunteer. The corresponding sodium magnitude image is shown in (c), showing a good correlation with breast anatomy (high sodium concentration in fibroglandular tissue and lower concentration in fatty tissue). A 3D sodium B1 map using the phase‐sensitive method is shown in (d). The phase‐sensitive method yields a high‐quality B1 map in vivo despite low sodium image SNR. Representative figure reproduced from Ref. 43, with permission from John Wiley & Sons, Magnetic Resonance in Medicine.

Considering B0 shimming, the low gyromagnetic ratio of the 23Na nucleus reduces spin dephasing that results in lesser off‐resonance artifacts. However, these artifacts still influence image quality at UHF strength. Hence, B0 shimming is performed through the 1H‐based signal. 44 B0 correction can be computed from two sodium images acquired with echo time values TE1 and TE2 using a 23Na‐UTE sequence. 45 The off‐resonance (∆ω) map is then generated from the phase difference (∅2 − ∅1) of the sodium images as:

| (6) |

After the evaluation and correction of PVE, B1 and B0 inhomogeneities, then the corrected 23Na signal intensity is converted into concentration using calibration reference solutions containing sodium ions of known standard concentrations (within the expected tissue range) placed in the field of view (FOV). 41 A calibration equation is then obtained from a linear fitting of signal intensities and their known concentrations.

In Vivo Quantification of Intracellular Sodium

Although a conventional UTE 23Na‐MRI sequence only permits the acquisition of TSC signals, 21 direct acquisition and quantification of the ISC signal can be achieved based on the resonance frequency shift of extracellular Na+ ions, and utilizes membrane‐impermeable paramagnetic frequency shift reagents. The negatively charged shift reagents form ion pair complexes with extracellular Na+ ions, thereby changing its resonance frequency. However, these shift reagents are limited to animal experiments due to their high toxicity and occasional inability to produce resolved resonance. 46 , 47

Instead, an inversion recovery (IR) sequence generates ISC signals based on the T1 relaxation of Na+ ions. In intra‐ and extracellular matrix isolation, the sodium T1 relaxation time in the denser intracellular matrix is significantly shorter 46 due to frequent interactions between Na+ ions and macromolecular structures. Signals weighted towards intracellular sodium are therefore isolated by suppressing the nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) signal with long T1 originating from the extracellular matrix. 24 However, IR is limited by the specific absorption rate (SAR). 48 SAR can be controlled by increasing the repetition time at the expense of SNR, or by increasing inversion pulse duration, since the dissipated power is inversely proportional to the RF pulse duration. 49

Alternatively, intra‐ and extracellular matrix isolation can be achieved by using a suitable multiple quantum filter (MQF) to separate the single and multiple quantum coherence (S/MQC) resulting from the Na+ nucleus' T2 biexponential relaxation. The triple quantum signal is believed to originate from the intracellular compartment and is typically filtered out of the MQC with either four or three nonselective RF pulses and a phase cycling scheme. 50 , 51 In the four‐pulse sequence, the first RF pulse applied creates the first‐order coherence, which evolves freely within the preparation time τ. Next, the second pulse refocuses the created coherence, and the third pulse creates the higher‐order coherence, which is then converted to an observable signal by the fourth pulse within an evolution time δ. 52 , 53 The omission of the refocusing pulse results in the three‐pulse TQF sequence. This sequence is more suitable for in vivo imaging than the conventional four‐pulse sequence due to its reduced dependency on the RF (B1) field. 53 , 54 However, the lack of the refocusing pulse makes the TQF signal more sensitive to B0 inhomogeneity, leading to signal loss. Nevertheless, this loss of signal can be regulated using a phase cycle scheme to separately acquire and recombine the individual coherence to avoid destructive interference. 53

Diagnostic and Prognostic Value of 23Na‐MRI as an Imaging Biomarker

Multiparametric MRI combines conventional 1H, diffusion‐weighted (DW) and dynamic contrast‐enhanced (DCE) MRI techniques to capture morphological and cellular changes in lesions. However, extra information on the tumor microenvironment is needed to personalize and improve treatment outcomes. Importantly, sodium accumulation associated with tumor progression can be visualized with 23Na‐MRI. In addition, ISC changes have been shown to occur early following therapy, and hence sodium detection may potentially capture cell integrity changes before morphological changes are detectable. 55 , 56 Tissue parameters obtained from 23Na‐MRI reflect cell viability, tumor cellularity, tumor immunogenicity, and activity of the transmembrane proteins involved in Na+ ion transport. Thus, 23Na‐MRI parameters describe apoptotic, immunosuppressive, and resistive (Fig. 4) changes occurring in tumor cells and the microenvironment, thereby allowing antitumor therapy efficacy monitoring. These studies suggest that 23Na‐MRI should be added to the MRI multiparametric systems for cancer diagnosis, detection of tumor malignancy and progression, and monitoring of treatment response.

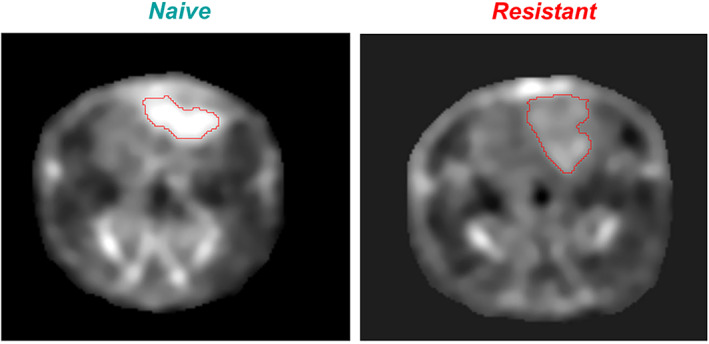

FIGURE 4.

Naive: sodium MRI of rat head with implanted naive glioma. The high concentration of sodium in glioma, visible as a bright spot on the image, indicates that tumor cells experience a large intracellular metabolic energy deficit and cannot maintain low intracellular sodium content, as seen in the normal brain around the glioma. These cancer cells are very sensitive to therapeutic interventions against tumors. The greater the sodium concentration in the tumor, the less resistant is the tumor. Resistant: sodium MRI of rat head with implanted resistant glioma (R1). The concentration of sodium inside the tumor is closer to the value in normal brain around the tumor. This small difference in sodium concentration indicates that the metabolic energy deficit is less dramatic in this tumor and they may have more cell density. Such tumor cells are more resistant to interventions, as is the case for normal cells around the tumor. Representative image reproduced from Ref. 55 with permission from John Wiley & Sons, NMR in Biomedicine.

Brain Cancer

23Na‐MRI has been clinically demonstrated to quantitatively characterize brain tumors by detecting elevated TSC, ISC, and EVF in tumors. 57 , 58 , 59 For instance, gliomas harboring IDH mutations have significantly higher TSC, TSC:ISC ratio, and TSC tumor:brain ratio when compared to IDH wildtype gliomas. 59 Moreover, the ISC:TSC ratio can classify gliomas with high specificity (94%) and sensitivity (86%), in addition to its being able to simultaneously predict progression‐free survival (PFS) and IDH mutation status. 29 Since IDH mutation status is a marker of positive prognosis, chemotherapy efficacy, and overall survival in glioma, 60 , 61 the ISC:TSC ratio could potentially be used for rapid therapy monitoring. Indeed, the ISC:TSC ratio has been suggested to be superior to IDH mutation status in tumor progression prediction. 29

Also, 23Na‐MRI quantified parameters have clinically demonstrated sensitivity to variations in treatment response between patients, and are therefore poised for treatment customization. 62 In addition, 1,3‐bis(2‐chloroethyl)‐1‐nitrosourea (BCNU)‐treated subcutaneous glioma 63 revealed lower TS and IS signal intensity in the treated group 5 days after therapy, when compared to untreated control tumors. The decreased IS signal was attributed to an improvement in cellular metabolism, assessed with 31P‐NMR. This observation suggests that BCNU treatment restores N+/K+ ATPase activity, thereby reducing ISC. Moreover, the reduction in TS signal may also result from a lower IS signal, as EVF was not significantly affected by chemotherapy. In a similar study on orthotopic 9L rat glioma treated with BCNU, effective therapy was marked by a drastic increase in TSC 7–9 days after treatment, with tumor shrinkage observed days later 56 (Fig. 5). Together, these studies demonstrate that TSC responds to treatment‐dependent changes in tumor cellularity before morphological changes occur, and similar results have also been obtained in clinical research. 64 However, it is important to note the differences in sodium concentration changes in response to therapy between these studies. Changes in ISC and/or EVF after therapy may result from a direct effect on the activities of the membrane ion transport system, as well as on mechanisms and pathways through which therapy induced apoptosis. 65 , 66 However, this is unlikely, as both studies used the same tumor model (9L rat glioma), chemotherapy drug (BCNU), and dosage (26.6 and 25 mg/kg). Hence, the reported variations in sodium concentration probably result from differences in tumor location, acquisition protocol, scanner type, and quantification method. While Schepkin et al 56 employed 23Na‐MRI at 9.4T to acquire sodium signal from orthotopic 9L rat glioma, Winter et al 63 used 23Na‐NMR spectroscopy at 9.4T on subcutaneously implanted 9L glioma. Nevertheless, a decreased TSC after therapy, as reported by Winter et al, is in agreement with results obtained with breast cancer chemotherapy. 67 , 68 It should also be considered that the brain typically exhibits high Na+ ion density, 69 which may have influenced the signal intensity detected in the orthotopic brain tumor model used by Schepkin et al. Therefore, more research is needed to clarify the response of 9L glioma to BCNU therapy.

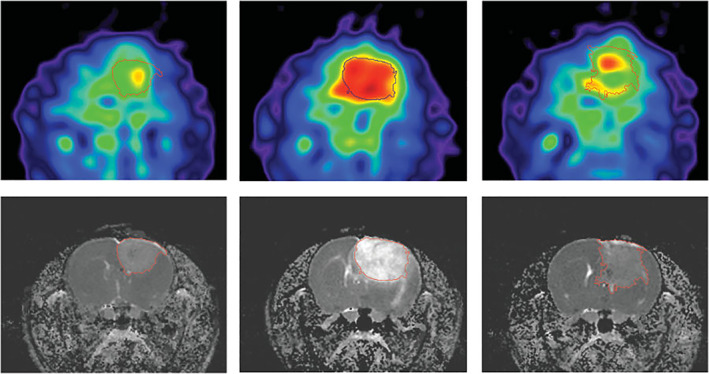

FIGURE 5.

BCNU‐treated 9L rat glioma. Sodium MRI (top) and proton ADC maps (bottom) acquired at days 0, 7, and 23 (left to right) after BCNU injection, performed at the 17th day from tumor implantation. Central Na image at day 7 illustrates the main feature for all treated animals: A dramatic Na concentration increase observed throughout the entire tumor area. The images on day 23 show tumor during regrowth after tumor‐shrinking started at day 9 and its maximum regression on day 16. Reproduced from Ref. 56 with permission from John Wiley & Sons, Magnetic Resonance in Medicine.

Radiotherapy plays a central role in cancer management, with approximately half of all cancer patients put on radiotherapy either as part of initial treatment to cure the patient or as palliative treatment to relieve the patient of symptoms and improving their quality of life. The ability to monitor such therapy in real time offers the opportunity to personalize therapy at an early stage of cancer management. The feasibility of monitoring radiotherapy with TSC has therefore been demonstrated on rat induced glioma. 41 The study revealed that TSC is sensitive to tumor progression and the consequent increase in both ISC and EVF. However, a single radiation dose of 20Gy failed to produce a consistent and measurable tumor response, which was attributed to the heterogeneity in the animal model as indicated by histopathology. 41 Additionally, the response of human glioblastoma to fractionated chemoradiotherapy using biological markers (tumor cell volume fraction, residual tumor volume, tumor cell kills) obtained from 23Na‐MRI‐acquired TSC demonstrated sensitivity to real‐time changes within the tumor volume. These markers also showed that there is variation in chemoradiotherapy treatment response in glioblastoma patients, 62 providing the option of switching nonresponding patients to the next alternative therapy. However, there was no correlation between the observed variation in tumor response to therapy and time to progression or overall survival.

Finally, clinical studies on 23Na‐MRI repeatability and reproducibility in assessing biochemical tissue parameters 70 , 71 , 72 indicate that changes in ISC and EVF greater than 50% can reliably be detected in brain‐related pathology. 71 Similarly, TSC also shows good repeatability and reproducibility, 70 both within and between sites and scanners. 72

Prostate Cancer

The three main treatment options available for localized prostate cancer management are surgery, radiotherapy, and active surveillance. Active surveillance is the regular monitoring of the disease and curative intervention initiated when disease progression is observed. 73 This treatment strategy is often used for low‐risk prostate cancers, as intervention often has effects on sexual, urinary, or bowel function, thereby affecting the patient's quality of life. 74 Active surveillance of disease progression is usually done through blood examinations (eg, prostate‐specific antigen [PSA] test), digital rectal examination (DRE), and image‐guided prostate biopsy, 75 , 76 and multiparametric MRI is a recent addition to these methods. 77 , 78 Since the comprehensive information provided by the combination of the various MRI tissue parameters improves diagnosis and prognosis, the addition of multiparametric MRI to the prostate cancer surveillance methods significantly increases the accuracy of the Gleason score and the detection specificity of clinically significant prostate cancers. Thus, multiparametric MRI reduces the frequency of biopsies needed to diagnose and monitor prostate cancer patients.

23Na‐MRI is a promising noninvasive biomarker for characterization and early detection of tumor progression in diagnosis and active monitoring of low‐risk prostate cancer. Studies in this area of research report an overall increase in TSC and ISC in prostate lesions when compared to normal tissues. 79 , 80 Moreover, clinical research reveals the peripheral zone is characterized by a higher TSC; hence, tumors in this region have elevated TSC compared to tumors located in the other regions of the prostate, 79 , 81 and therefore TSC levels characterize prostate lesions based on their location. However, lesions located in the transition zone exhibit lower TSC levels when compared to normal tissues in the same prostate region. This contradictory result may be due to the small sample size of the transition zone tumor lesions. A similar study 80 suggested that changes in TSC (ΔTSC) evaluated as the difference between TSC in lesion and healthy prostate tissue characterize prostate tumors. And a statistically significant correlation was found between ΔTSC and Gleason score (GS). 80 Thus, in addition to predicting Gleason score, ΔTSC may also contribute to personalized therapy through the characterization of individual lesions (Fig. 6). However, contrary to Broeke et al, 80 the correlation between TSC and Gleason score observed by Barrett et al 79 was not statistically significant, 79 therefore further studies are required to elucidate the potential of using TSC to predict Gleason score.

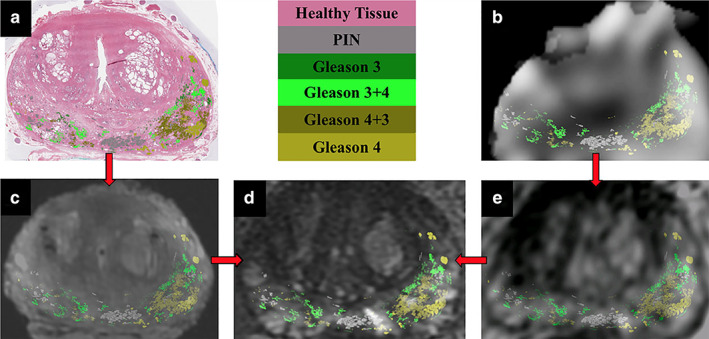

FIGURE 6.

Registration pipeline for all imaging data with Gleason contours overlaid. Whole‐mount histopathology (a) and the sodium‐MR image (b) are registered to the T2‐weighted ex vivo (c) and the lower‐resolution T2‐weighted in vivo images (e). The ex and in vivo images are individually registered to the high‐resolution T2‐weighted in vivo image (d). Gleason contour legends are shown in the upper middle panel. Figure reproduced from Ref. 80 with permission from John Wiley and Sons, Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging.

A chemotherapeutic study on prostate tumor xenograft mice showed that TSC can improve diagnosis and monitoring of tumor progression by distinguishing areas of viable and nonviable tumor cells. 82 ISC exhibits an acute response to therapy through an increase in IS signal intensity within 24 hours of treatment. This rapid increment in IS signal intensity may be a marker of the early stages of apoptosis, when cell membrane structural integrity is lost, ultimately leading to increased permeability to Na+ ions. On the other hand, a decline in IS signal intensity 48 hours after treatment indicates the last stages of apoptosis, when cell membranes finally rupture, resulting in reduced ISC 66 , 82 , 83 and consequently a decrease in TSC.

Breast Cancer

Early detection and classification of breast lesions increase the potential of survival due to early implementation of therapy. 84 However, the complexity of breast tissues requires detection methods with high specificity, accuracy, and more effective characterization of malignancy and early therapeutic efficacy. 23Na‐MRI is a promising and clinically feasible method for the assessment of early changes in tumor cellularity, biochemical properties, and energy metabolism in the breast tumor microenvironment. 67 , 68 , 85 , 86 This imaging technique can distinguish benign and normal glandular tissue from treatment‐naive breast malignant lesions, which showed significantly elevated TSC. 85 , 86 Consistent with this, Ouerkerk et al reported a more than 60% increase in TSC in malignant breast lesions relative to unaffected remote glandular tissue, whereas the TSC of benign lesions remained relatively on a par with that of glandular tissues. 87

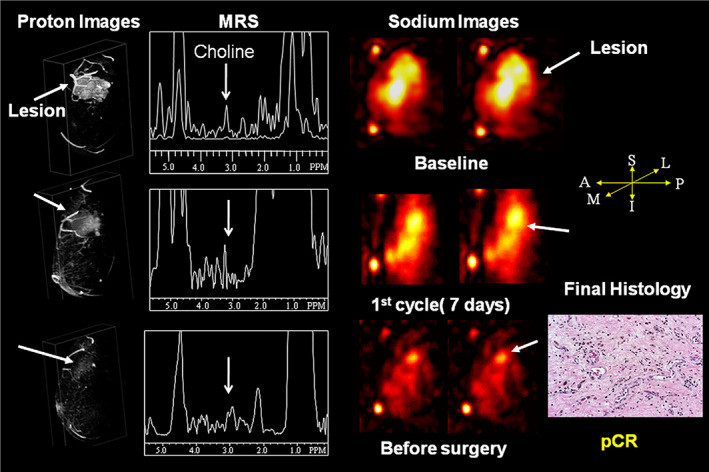

Chemotherapy response monitoring of induced breast tumors in rats with 23Na‐MRI revealed an increased IS signal intensity (34 ± 3%) 24 hours after Taxotere treatment. 88 Moreover, the treated breast tumors showed a reduced proliferation index (Ki‐67), low ISC/TSC ratio, and high apoptotic index, 88 in agreement with a previous report. 82 In a clinical study on breast cancer patients undergoing preoperative systemic therapy (PST), the treatment response was marked by a significant decrease in TSC, standardized uptake values (SUV), choline SNR, and proliferation index (Ki‐67) in responders (Fig. 7), whereas nonresponders showed an increase in TSC and Ki‐67. 67 , 68 The decrease in TSC after the first cycle of treatment may result from the rupture of cell membranes at the last stage of apoptosis, or from the restoration and activation of the Na+/K+ ATPase pump, ultimately leading to a reduction in ISC signal intensity. Since TSC is a weighted average of ISC and ESC, lower ISC signal intensity causes a decrease in TSC signal intensity, given that EVF remains unchanged. 63

FIGURE 7.

Demonstration of multiparametric and multinuclear magnetic resonance on a 54‐year‐old woman with T3N0M0 invasive ductal carcinoma on chemotherapy. At baseline contrast‐enhanced MRI showed a large tumor volume with markedly increased choline level and total tissue sodium concentration. After treatment, there were steady reductions in choline SNR, TSC, and tumor volumes beginning after the first cycle of treatment. At surgery, the patient was determined to have a pathologic complete response (pCR). Representative figure reproduced from Ref. 70 with permission from Elsevier, Academic Radiology.

Lung Cancer

Coagulative necrosis is often found at the core of rapidly growing malignant tumors due to an insufficient supply of oxygen (hypoxia) and nutrients caused by the inaccessibility of the blood vessels. 89 , 90 Necrosis is associated with poor prognosis and tumor aggression in cancers such as gastrointestinal stromal carcinoma, 91 colorectal cancer, 92 and non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). 90 Rapid visualization of tumor regions with limited oxygen supply (necrotic regions) and regions of viable tumor cells with TSC and ISC distribution maps could improve the planning of radiotherapy treatments, as hypoxic cells are more resistant to radiotherapy. Henzler et al 93 have shown that 23Na‐MRI can provide information on the distribution of tumor cell viability in lung cancer patients. High TSC signal intensity was detected in viable tumor regions, and the highest sodium signal intensity in the necrotic region. 93 However, as ISC measures sodium ions in intact cells before the cell membrane ruptures, it is likely a more sensitive marker of tumor cell viability. Thus, further studies should investigate the efficacy of using 23Na‐MRI tissue and intracellular sodium weighted sequences to detect tumor cell viability.

Ovarian Cancer

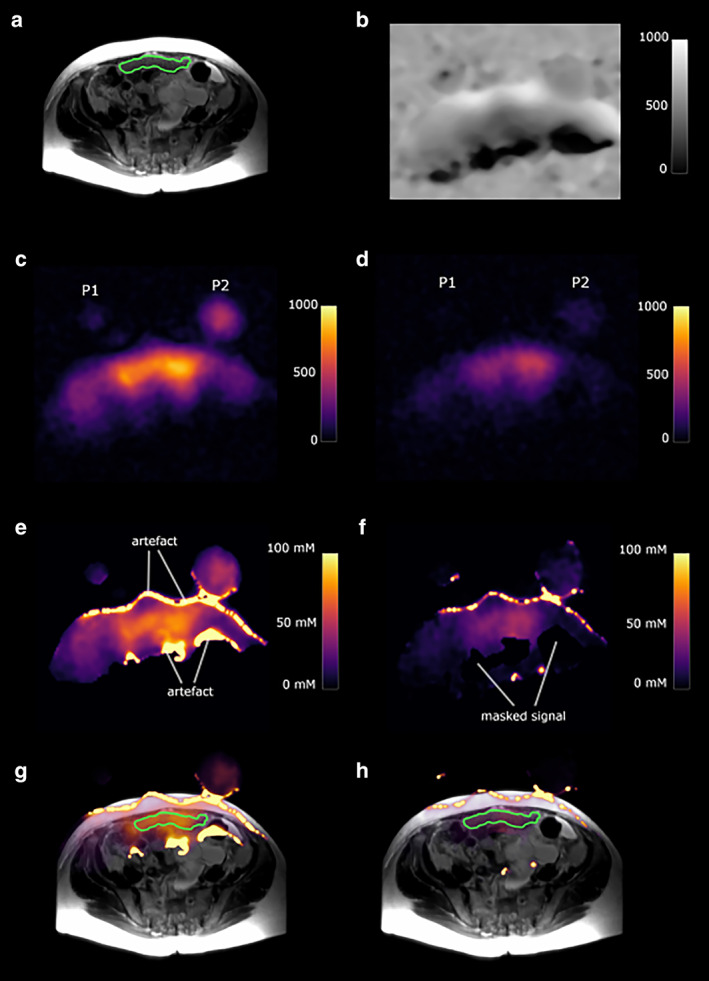

Intra‐ and intertumoral heterogeneity resulting from differences in the molecular makeup of cells within a tumor or between tumors 94 , 95 causes important variations in treatment response between patients, and even within a tumor in an individual patient. Ovarian cancer, particularly high‐grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSOC), 96 , 97 is characterized by inter‐ and intratumoral heterogeneity and is therefore often associated with treatment resistance and shorter overall and progression‐free survival. 97 The visualization and accurate quantification of tumor heterogeneity and dynamics during HGSOC treatment are essential for predicting treatment response and significantly improving patient management. TSC and ISC distribution maps generated from 23Na‐MRI reflect tumor heterogeneity by identifying regions of viable cells, necrosis and/or apoptosis, and tumor cell kill. 23Na‐MRI has been demonstrated to be clinically feasible in ovarian cancer through its application in the assessment of peritoneal deposits of HGSOC patients (Fig. 8), indicating a strong negative correlation between tumor cellularity and TSC. 31 The detection of tumor cellularity changes during therapy with 23Na‐MR is a promising technique for guiding treatment optimization in individual patients.

FIGURE 8.

A 73‐year‐old high‐grade serous ovarian cancer patient. P1 and P2 represent slices through the two sodium phantoms. The green outline shows a peritoneal cancer deposit. (a) T2‐weighted image. (b) Sodium B1 map; scale bar represents arbitrary units. (c) Total sodium image; scale bar represents image intensity. (d) Intracellular weighted sodium image; scale bar represents image intensity. (e) Masked total sodium concentration map; scale bar represents sodium concentration in mM. (f) Masked intracellular weighted sodium concentration map; scale bar represents sodium concentration in mM. (g) Fused T2W image and total sodium concentration map. (h) Fused T2W image and intracellular weighted sodium concentration map. Figure obtained from Ref. 31 with permission from Elsevier, European Journal of Radiology Open.

Retinoblastoma

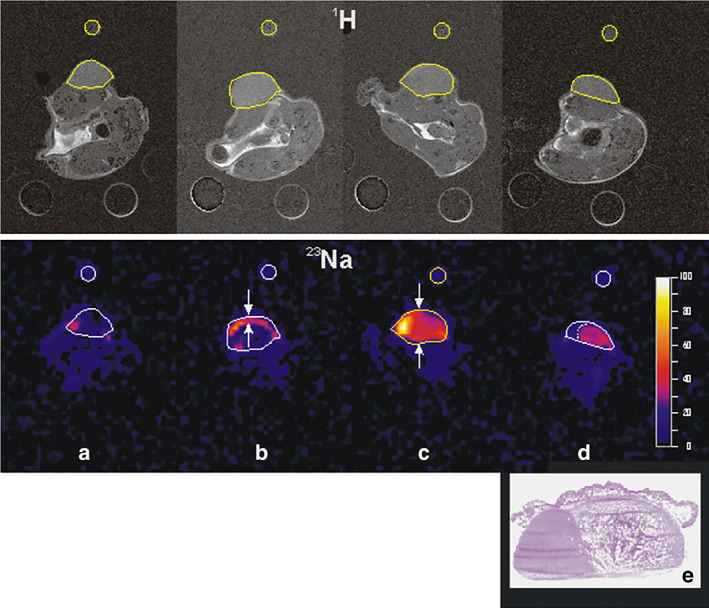

23Na can be used as an endogenous marker to characterize intra‐ and extracellular compartments, thereby providing information on cell packing through the generation of EVF and CVF maps. High cell density tissues can be distinguished by a relatively low EVF and reduced TSC, provided that ISC remains constant. However, therapy‐induced necrosis and/or apoptosis leads to a reduction in cell packing (low cell density), which is typically characterized by an increase in EVF and TSC. This effect was observed in retinoblastoma xenograft mice monitored with 23Na‐MRI within 2 hours after photodynamic therapy. 98 Indeed, a high TS signal in the tumor spread and covered almost the entire tumor volume within 24 hours (Fig. 9), which likely resulted from the activation of the apoptotic process.

FIGURE 9.

The double targeting DEG‐PDT protocol promotes massive necrosis of the tissue and reduction of the tumor volume. Longitudinal follow‐up using combined 1H‐ and 23Na MRI. Upper panel: 1H‐images (TE = 24 msec); lower panel: functional 23Na‐images (TE = 7 msec). Images (a) before treatment, (b) 2 hours after PDT, (c) 24 hours after PDT, and (d) 13 days after PDT. The high‐intensity regions visible in the 23Na‐images denote damaged structures of the tumor. (e) Histological analysis at the end of the experiment shows widespread necrosis of the tumor (75%). Representative figure reproduced from Ref. 98 with permission from Elsevier, Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy.

Immunotherapy

We speculate that TSC may potentially be used as a marker for immunotherapeutic response, as ESC increases with inflammation and is a promising modulator of immunity. Indeed, ESC has been shown to promote proinflammatory macrophage and T‐cell functions and simultaneously dampen their antiinflammatory potential. 99 Thus, the rise in ESC observed in cancer may play an essential role in its immunogenicity.

Moreover, extracellular acidification due to elevated ISC as a consequence of the dysfunction of NHE1 may promote cancer cell evasion of immune surveillance by impairing cytotoxic cells activation. For example, the cytotoxicity of the natural killer (NK) cells is inhibited under such conditions. 100 In addition, acidic microenvironments induce defects in T‐lymphocyte cell cycle progression due to their inability to secret T‐cell growth factor interleukin 2 (IL‐2) and interferon gamma (IFN‐γ). 101 Notably, recent studies reported the expression of NHE1 in tumor‐associated macrophages (TAM), which are known to promote disease progression. 102 , 103 Consistent with this, NHE1 has been involved in tumor–TAM communication, which contributes to the development of an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment. Moreover, NHE1 inhibition stimulates proinflammation activation of TAM and increases the infiltration of cytotoxic T cells into tumor cells. 103 , 104 Importantly, combined therapy of temozolomide (TMZ), anti‐PD‐1 antibody, and NHE1 inhibition significantly extended median survival in mouse glioma models. 103 Therefore, TSC may regulate immunotherapy response via a pH‐ or ESC‐dependent mechanism. In the light of these findings, we propose that the spatial and temporal dynamics of sodium visualized with 23Na‐MRI may be used as a marker of patient response to immunotherapy.

Perspectives

In recent years, growing evidence suggests that increased sodium accumulation in cancerous tissues measured by 23Na‐MRI is a reliable biomarker for metastasis, inflammation, and tumor progression. Several studies revealed a pronounced increase in tissue sodium concentration (TSC) in metastatic lesions, when compared to healthy tissues or benign lesions. Moreover, increased sodium concentration does not only characterize lesions, but also correlates with the MIB‐1 proliferation rate, 105 IDH mutation status, 29 tumor immunogenicity, 106 Gleason score, 80 and overall survival. 29 However, clinical research addressing the diagnostic and prognostic value of 23Na‐MRI is limited to a few cancer types, therapeutic methods, and patients, and only a handful of studies assessed treatment response. Also, large longitudinal clinical studies to assess treatment response to different therapy methods, and their correlation with conventional markers of progression and metastasis, are yet to be carried out. To date, the isolation of the extracellular sodium from the total tissue sodium in cancer is still limited. A direct assessment of increased extracellular sodium associated with cancer using 23Na‐MRI may enable the direct characterization of the extracellular space increment resulting from tumor revascularization, inflammation, immune suppression, and apoptosis and/or necrosis associated with tumor progression or therapeutic effects. 23Na‐MRI has recently seen significant improvements in software capabilities coupled with developments in magnetic field strength, specialized RF coils, enhanced gradient coils strength, and performance. Together, these technical advances boost SNR, sensitivity, and specificity up to clinical standards. However, despite this significant progress, 23Na‐MRI technology still faces important challenges. For instance, 23Na‐MRI cannot achieve precise differentiation between the intracellular and extracellular compartments, and sensitivity to B0 and B1 field inhomogeneities compromise the accuracy of sodium quantifications.

To conclude, 23Na‐MRI is a promising noninvasive imaging biomarker that may be used as an alternative to current invasive methods for cancer diagnosis and prognosis, thereby relieving patients from excessive discomfort. However, further research, including clinical studies, is necessary to overcome the limitations of this imaging technology and to translate it to oncology.

Contract grant sponsor: National Natural Science Foundation of China; Contract grant numbers: 81627901, 81471724, 81771903; Contract grant sponsor: National Basic Research Program of China; Contract grant number: 2015CB931800; Contract grant sponsor: Tou‐Yan Innovation Team Program of the Heilongjiang Province; Contract grant number: 2019‐15; Contract grant sponsor: Key Laboratory of Molecular Imaging Foundation (College of Heilongjiang Province).

Contributor Information

Kai Wang, Email: wangkai@hrbmu.edu.cn.

Xilin Sun, Email: wangkai@hrbmu.edu.cn, Email: sunxl@ems.hrbmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1. Xia J, Huang N, Huang H, et al. Voltage‐gated sodium channel Nav 1.7 promotes gastric cancer progression through MACC1‐mediated upregulation of NHE1. Int J Cancer 2016;139(11):2553‐2569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lopez‐Charcas O, Espinosa AM, Alfaro A, et al. The invasiveness of human cervical cancer associated to the function of NaV1.6 channels is mediated by MMP‐2 activity. Sci Rep 2018;8(1):12995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Khajah MA, Mathew PM, Luqmani YA. Na+/K+ ATPase activity promotes invasion of endocrine resistant breast cancer cells. PLoS One 2018;13(3):e0193779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Xie R, Wang H, Jin H, Wen G, Tuo B, Xu J. NHE1 is upregulated in gastric cancer and regulates gastric cancer cell proliferation, migration and invasion. Oncol Rep 2017;37(3):1451‐1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wang H, Long X, Wang D, et al. Increased expression of Na(+)/H(+) exchanger isoform 1 predicts tumor aggressiveness and unfavorable prognosis in epithelial ovarian cancer. Oncol Lett 2018;16(5):6713‐6720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fraser SP, Diss JK, Chioni A‐M, et al. Voltage‐gated sodium channel expression and potentiation of human breast cancer metastasis. Clin Cancer Res 2005;11(15):5381‐5389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Roger S, Besson P, Le Guennec JY. Involvement of a novel fast inward sodium current in the invasion capacity of a breast cancer cell line. Biochim Biophys Acta 2003;1616(2):107‐111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Grimes J, Fraser S, Stephens G, et al. Differential expression of voltage‐activated Na+ currents in two prostatic tumour cell lines: Contribution to invasiveness in vitro. FEBS Lett 1995;369(2–3):290‐294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. House CD, Wang BD, Ceniccola K, et al. Voltage‐gated Na+ channel activity increases colon cancer transcriptional activity and invasion via persistent MAPK signaling. Sci Rep 2015;5:11541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Onganer PU, Djamgoz MB. Small‐cell lung cancer (human): Potentiation of endocytic membrane activity by voltage‐gated Na(+) channel expression in vitro. J Membr Biol 2005;204(2):67‐75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Roger S, Rollin J, Barascu A, et al. Voltage‐gated sodium channels potentiate the invasive capacities of human non‐small‐cell lung cancer cell lines. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2007;39(4):774‐786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bugan I, Kucuk S, Karagoz Z, et al. Anti‐metastatic effect of ranolazine in an in vivo rat model of prostate cancer, and expression of voltage‐gated sodium channel protein in human prostate. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 2019;22:569‐579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Amith SR, Wilkinson JM, Fliegel L. KR‐33028, a potent inhibitor of the Na(+)/H(+) exchanger NHE1, suppresses metastatic potential of triple‐negative breast cancer cells. Biochem Pharmacol 2016;118:31‐39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Aktas HG, Akgun T. Naringenin inhibits prostate cancer metastasis by blocking voltage‐gated sodium channels. Biomed Pharmacother 2018;106:770‐775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bottomley PA. Sodium MRI in man: Technique and findings. Encyclopedia of Magnetic Resonance; 2012. New York: Wiley.

- 16. Machnik A, Neuhofer W, Jantsch J, et al. Macrophages regulate salt‐dependent volume and blood pressure by a vascular endothelial growth factor‐C‐dependent buffering mechanism. Nat Med 2009;15(5):545‐552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schwartz L, Guais A, Pooya M, Abolhassani M. Is inflammation a consequence of extracellular hyperosmolarity? J Inflamm 2009;6:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Amara S, Whalen M, Tiriveedhi V. High salt induces anti‐inflammatory MPhi2‐like phenotype in peripheral macrophages. Biochem Biophys Rep 2016;7:1‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schreiner A, Rose C. Quantitative imaging of intracellular sodium. In: Méndez‐Vilas A, editor. Current microscopy contributions to advances in science and technology. Badajoz: Formatex Research Center; 2012. p 119‐129. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sarkar AR, Heo CH, Park MY, Lee HW, Kim HM. A small molecule two‐photon fluorescent probe for intracellular sodium ions. Chem Commun 2014;50(11):1309‐1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Madelin G, Kline R, Walvick R, Regatte RR. A method for estimating intracellular sodium concentration and extracellular volume fraction in brain in vivo using sodium magnetic resonance imaging. Sci Rep 2014;4:4763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Brahme A. Comprehensive biomedical physics. Oxford, UK: Newnes; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Madelin G, Lee JS, Regatte RR, Jerschow A. Sodium MRI: Methods and applications. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc 2014;79:14‐47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Konstandin S, Nagel AM. Measurement techniques for magnetic resonance imaging of fast relaxing nuclei. Magn Reson Mater Phys Biol Med 2014;27(1):5‐19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sandilya M, Nirmala S. Compressed sensing trends in magnetic resonance imaging. Eng Sci Technol Int J 2017;20(4):1342‐1352. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Huang J, Wang L, Zhu Y. Compressed sensing MRI reconstruction with multiple sparsity constraints on radial sampling. Math Probl Eng 2019;2019:1‐14. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yang AC‐Y, Kretzler M, Sudarski S, Gulani V, Seiberlich N. Sparse reconstruction techniques in MRI: Methods, applications, and challenges to clinical adoption. Invest Radiol 2016;51(6):349‐364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nielles‐Vallespin S, Weber MA, Bock M, et al. 3D radial projection technique with ultrashort echo times for sodium MRI: Clinical applications in human brain and skeletal muscle. Magn Reson Med 2007;57(1):74‐81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Biller A, Badde S, Nagel A, et al. Improved brain tumor classification by sodium MR imaging: Prediction of IDH mutation status and tumor progression. Am J Neuroradiol 2016;37(1):66‐73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lu A, Atkinson IC, Claiborne TC, Damen FC, Thulborn KR. Quantitative sodium imaging with a flexible twisted projection pulse sequence. Magn Reson Med 2010;63(6):1583‐1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Deen SS, Riemer F, McLean MA, et al. Sodium MRI with 3D‐cones as a measure of tumour cellularity in high grade serous ovarian cancer. Eur J Radiol Open 2019;6:156‐162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Riemer F, Solanky BS, Stehning C, Clemence M, Wheeler‐Kingshott CA, Golay X. Sodium (23 Na) ultra‐short echo time imaging in the human brain using a 3D‐cones trajectory. Magn Reson Mater Phys Biol Med 2014;27(1):35‐46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pipe JG, Zwart NR, Aboussouan EA, Robison RK, Devaraj A, Johnson KO. A new design and rationale for 3D orthogonally oversampled k‐space trajectories. Magn Reson Med 2011;66(5):1303‐1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Johnson KM. Hybrid radial‐cones trajectory for accelerated MRI. Magn Reson Med 2017;77(3):1068‐1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Christensen JD, Barrère BJ, Boada FE, Vevea JM, Thulborn KR. Quantitative tissue sodium concentration mapping of normal rat brain. Magn Reson Med 1996;36(1):83‐89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ladd ME, Bachert P, Meyerspeer M, et al. Pros and cons of ultra‐high‐field MRI/MRS for human application. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc 2018;109:1‐50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tang F, Liu F, Freschi F, et al. An improved asymmetric gradient coil design for high‐resolution MRI head imaging. Phys Med Biol 2016;61(24):8875‐8889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Harris RK, Becker ED, De Menezes SMC, Goodfellow R, Granger P. NMR nomenclature. Nuclear spin properties and conventions for chemical shifts (IUPAC recommendations 2001). Pure Appl Chem 2001;73(11):1795‐1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Niesporek SC, Hoffmann SH, Berger MC, et al. Partial volume correction for in vivo (23)Na‐MRI data of the human brain. Neuroimage 2015;112:353‐363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rousset OG, Ma Y, Evans AC. Correction for partial volume effects in PET: Principle and validation. J Nucl Med 1998;39(5):904‐911. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Thulborn KR, Davis D, Adams H, Gindin T, Zhou J. Quantitative tissue sodium concentration mapping of the growth of focal cerebral tumors with sodium magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Med 1999;41(2):351‐359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mirkes CC, Hoffmann J, Shajan G, Pohmann R, Scheffler K. High‐resolution quantitative sodium imaging at 9.4 Tesla. Magn Reson Med 2015;73(1):342‐351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Allen SP, Morrell GR, Peterson B, et al. Phase‐sensitive sodium B1 mapping. Magn Reson Med 2011;65(4):1125‐1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gai ND, Rochitte C, Nacif MS, Bluemke DA. Optimized three‐dimensional sodium imaging of the human heart on a clinical 3T scanner. Magn Reson Med 2015;73(2):623‐632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tsang A, Stobbe RW, Beaulieu C. Evaluation of B0‐inhomogeneity correction for triple‐quantum‐filtered sodium MRI of the human brain at 4.7 T. J Magn Reson 2013;230:134‐144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Winter PM, Bansal N. TmDOTP5–as a 23Na shift reagent for the subcutaneously implanted 9L gliosarcoma in rats. Magn Reson Med 2001;45(3):436‐442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gupta RK, Gupta P. Direct observation of resolved resonances from intra‐and extracellular sodium‐23 ions in NMR studies of intact cells and tissues using dysprosium (III) tripolyphosphate as paramagnetic shift reagent. J Magn Reson 1982;47:344‐350. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Madelin G, Lee JS, Inati S, Jerschow A, Regatte RR. Sodium inversion recovery MRI of the knee joint in vivo at 7T. J Magn Reson 2010;207(1):42‐52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Stobbe R, Beaulieu C. In vivo sodium magnetic resonance imaging of the human brain using soft inversion recovery fluid attenuation. Magn Reson Med 2005;54(5):1305‐1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Fleysher L, Oesingmann N, Inglese M. B(0) inhomogeneity‐insensitive triple‐quantum‐filtered sodium imaging using a 12‐step phase‐cycling scheme. NMR Biomed 2010;23(10):1191‐1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Benkhedah N, Bachert P, Semmler W, Nagel AM. Three‐dimensional biexponential weighted (23)Na imaging of the human brain with higher SNR and shorter acquisition time. Magn Reson Med 2013;70(3):754‐765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Boada F, Tanase C, Davis D, et al. Non‐invasive assessment of tumor proliferation using triple quantum filtered 23Na MRI: Technical challenges and solutions. In: 26th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. Volume 2: IEEE; 2004. pp 5238–5241. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53. Tanase C, Boada FE. Triple‐quantum‐filtered imaging of sodium in presence of B(0) inhomogeneities. J Magn Reson 2005;174(2):270‐278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hancu I, van der Maarel JR, Boada FE. A model for the dynamics of spins 3/2 in biological media: Signal loss during radiofrequency excitation in triple‐quantum‐filtered sodium MRI. J Magn Reson 2000;147(2):179‐191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Schepkin VD. Sodium MRI of glioma in animal models at ultrahigh magnetic fields. NMR Biomed 2016;29(2):175‐186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Schepkin VD, Ross BD, Chenevert TL, et al. Sodium magnetic resonance imaging of chemotherapeutic response in a rat glioma. Magn Reson Med 2005;53(1):85‐92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ouwerkerk R, Bleich KB, Gillen JS, Pomper MG, Bottomley PA. Tissue sodium concentration in human brain tumors as measured with 23Na MR imaging. Radiology 2003;227(2):529‐537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Nunes Neto LP, Madelin G, Sood TP, et al. Quantitative sodium imaging and gliomas: A feasibility study. Neuroradiology 2018;60(8):795‐802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Shymanskaya A, Worthoff WA, Stoffels G, et al. Comparison of [18 F] fluoroethyltyrosine PET and sodium MRI in cerebral gliomas: A pilot study. Mol Imaging Biol 2020;22(1):198‐207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Houillier C, Wang X, Kaloshi G, et al. IDH1 or IDH2 mutations predict longer survival and response to temozolomide in low‐grade gliomas. Neurology 2010;75(17):1560‐1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. SongTao Q, Lei Y, Si G, et al. IDH mutations predict longer survival and response to temozolomide in secondary glioblastoma. Cancer Sci 2012;103(2):269‐273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Thulborn KR, Lu A, Atkinson IC, et al. Residual tumor volume, cell volume fraction, and tumor cell kill during fractionated chemoradiation therapy of human glioblastoma using quantitative sodium MR imaging. Clin Cancer Res 2019;25(4):1226‐1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Winter PM, Poptani H, Bansal N. Effects of chemotherapy by 1, 3‐bis (2‐chloroethyl)‐1‐nitrosourea on single‐quantum‐and triple‐quantum‐filtered 23Na and 31P nuclear magnetic resonance of the subcutaneously implanted 9L glioma. Cancer Res 2001;61(5):2002‐2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Huang L, Zhang Z, Qu B, et al. Imaging of sodium MRI for therapy evaluation of brain Metastase with Cyberknife at 7T: A case report. Cureus 2018;10(4):e2502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Pistritto G, Trisciuoglio D, Ceci C, Garufi A, D'Orazi G. Apoptosis as anticancer mechanism: Function and dysfunction of its modulators and targeted therapeutic strategies. Aging 2016;8(4):603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Ouwerkerk R. Sodium MRI. Methods Mol Biol 2011;711:175‐201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Jacobs MA, Ouwerkerk R, Wolff AC, et al. Monitoring of neoadjuvant chemotherapy using multiparametric, 23Na MR, and multimodality (PET/CT/MRI) imaging in locally advanced breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2011;128(1):119‐126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Jacobs MA, Stearns V, Wolff AC, et al. Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging, spectroscopy and multinuclear (23Na) imaging monitoring of preoperative chemotherapy for locally advanced breast cancer. Acad Radiol 2010;17(12):1477‐1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Sengupta B, Faisal AA, Laughlin SB, Niven JE. The effect of cell size and channel density on neuronal information encoding and energy efficiency. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2013;33(9):1465‐1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Meyer MM, Haneder S, Konstandin S, et al. Repeatability and reproducibility of cerebral (23)Na imaging in healthy subjects. BMC Med Imaging 2019;19(1):26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Madelin G, Babb J, Xia D, Regatte RR. Repeatability of quantitative sodium magnetic resonance imaging for estimating pseudo‐intracellular sodium concentration and pseudo‐extracellular volume fraction in brain at 3T. PLoS One 2015;10(3):e0118692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Riemer F, McHugh D, Zaccagna F, et al. Measuring tissue sodium concentration: Cross‐vendor repeatability and reproducibility of (23) Na‐MRI across two sites. J Magn Reson Imaging 2019;50(4):1278‐1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Kinsella N, Helleman J, Bruinsma S, et al. Active surveillance for prostate cancer: A systematic review of contemporary worldwide practices. Transl Androl Urol 2018;7(1):83‐97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Hamdy FC, Donovan JL, Lane JA, et al. 10‐year outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2016;375(15):1415‐1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Mottet N, Bellmunt J, Briers E, Bolla MLB. EAU—ESTRO—ESUR—SIOG guidelines on prostate cancer. Presented at the EAU Annual Congress, Copenhagen; 2018.

- 76. Sanda MG, Cadeddu JA, Kirkby E, et al. Clinically localized prostate cancer: AUA/ASTRO/SUO guideline. Part I: Risk stratification, shared decision making, and care options. J Urol 2018;199(3):683‐690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Brown LC, Ahmed HU, Faria R, et al. Multiparametric MRI to improve detection of prostate cancer compared with transrectal ultrasound‐guided prostate biopsy alone: The PROMIS study. Health Technol Assess 2018;22(39):1‐176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Boesen L. Multiparametric MRI in detection and staging of prostate cancer. Scand J Urol 2015;49:25‐34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Barrett T, Riemer F, McLean MA, et al. Quantification of total and intracellular sodium concentration in primary prostate cancer and adjacent normal prostate tissue with magnetic resonance imaging. Invest Radiol 2018;53(8):450‐456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Broeke NC, Peterson J, Lee J, et al. Characterization of clinical human prostate cancer lesions using 3.0‐T sodium MRI registered to Gleason‐graded whole‐mount histopathology. J Magn Reson Imaging 2019;49(5):1409‐1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Barrett T, Riemer F, McLean MA, et al. Molecular imaging of the prostate: Comparing total sodium concentration quantification in prostate cancer and normal tissue using dedicated 13C and 23Na endorectal coils. J Magn Reson Imaging 2019;51:90‐97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Kline RP, Wu EX, Petrylak DP, et al. Rapid in vivo monitoring of chemotherapeutic response using weighted sodium magnetic resonance imaging. Clin Cancer Res 2000;6(6):2146‐2156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Vangestel C, Peeters M, Mees G, et al. In vivo imaging of apoptosis in oncology: An update. Mol Imaging 2011;10(5):340‐358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Jacobs MA, Wolff AC, Macura KJ, et al. Multiparametric and multimodality functional radiological imaging for breast cancer diagnosis and early treatment response assessment. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2015;2015(51):40‐46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Jacobs MA, Ouwerkerk R, Wolff AC, et al. Multiparametric and multinuclear magnetic resonance imaging of human breast cancer: Current applications. Technol Cancer Res Treat 2004;3(6):543‐550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Zaric O, Pinker K, Zbyn S, et al. Quantitative sodium MR imaging at 7T: Initial results and comparison with diffusion‐weighted imaging in patients with breast tumors. Radiology 2016;280(1):39‐48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Ouwerkerk R, Jacobs MA, Macura KJ, et al. Elevated tissue sodium concentration in malignant breast lesions detected with noninvasive 23Na MRI. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2007;106(2):151‐160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Sharma R, Kline RP, Wu EX, Katz JK. Rapid in vivo Taxotere quantitative chemosensitivity response by 4.23 Tesla sodium MRI and histo‐immunostaining features in N‐methyl‐N‐nitrosourea induced breast tumors in rats. Cancer Cell Int 2005;5:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Lee SY, Ju MK, Jeon HM, et al. Regulation of tumor progression by programmed necrosis. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2018;2018:3537471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Gkogkou C, Frangia K, Saif MW, Trigidou R, Syrigos K. Necrosis and apoptotic index as prognostic factors in non‐small cell lung carcinoma: A review. Springerplus 2014;3(1):120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Yi M, Xia L, Zhou Y, et al. Prognostic value of tumor necrosis in gastrointestinal stromal tumor: A meta‐analysis. Medicine 2019;98(17):e15338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Vayrynen SA, Vayrynen JP, Klintrup K, et al. Clinical impact and network of determinants of tumour necrosis in colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 2016;114(12):1334‐1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Henzler T, Konstandin S, Schmid‐Bindert G, et al. Imaging of tumor viability in lung cancer: Initial results using 23Na‐MRI. Rofo 2012;184(4):340‐344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Hollis RL, Gourley C. Genetic and molecular changes in ovarian cancer. Cancer Biol Med 2016;13(2):236‐247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. de Lartigue J. Tumor heterogeneity: A central foe in the war on cancer. J Commun Support Oncol 2016;16(3):e167‐e174. [Google Scholar]

- 96. Testa U, Petrucci E, Pasquini L, Castelli G, Pelosi E. Ovarian cancers: Genetic abnormalities, tumor heterogeneity and progression, clonal evolution and cancer stem cells. Medicines 2018;5(1):16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Schwarz RF, Ng CK, Cooke SL, et al. Spatial and temporal heterogeneity in high‐grade serous ovarian cancer: A phylogenetic analysis. PLoS Med 2015;12(2):e1001789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Lupu M, Thomas CD, Maillard P, et al. 23Na MRI longitudinal follow‐up of PDT in a xenograft model of human retinoblastoma. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther 2009;6(3–4):214‐220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Schatz V, Neubert P, Schroder A, et al. Elementary immunology: Na(+) as a regulator of immunity. Pediatr Nephrol 2017;32(2):201‐210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Müller B, Fischer B, Kreutz W. An acidic microenvironment impairs the generation of non‐major histocompatibility complex‐restricted killer cells. Immunology 2000;99(3):375‐384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Bosticardo M, Ariotti S, Losana G, Bernabei P, Forni G, Novelli F. Biased activation of human T lymphocytes due to low extracellular pH is antagonized by B7/CD28 costimulation. Eur J Immunol 2001;31(9):2829‐2838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Allavena P, Mantovani A. Immunology in the clinic review series; focus on cancer: Tumour‐associated macrophages: Undisputed stars of the inflammatory tumour microenvironment. Clin Exp Immunol 2012;167(2):195‐205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Guan X, Hasan MN, Begum G, et al. Blockade of Na/H exchanger stimulates glioma tumor immunogenicity and enhances combinatorial TMZ and anti‐PD‐1 therapy. Cell Death Dis 2018;9(10):1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Guan X, Luo L, Begum G, et al. Elevated Na/H exchanger 1 (SLC9A1) emerges as a marker for tumorigenesis and prognosis in gliomas. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2018;37(1):255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Nagel AM, Bock M, Hartmann C, et al. The potential of relaxation‐weighted sodium magnetic resonance imaging as demonstrated on brain tumors. Invest Radiol 2011;46(9):539‐547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Amara S, Tiriveedhi V. Inflammatory role of high salt level in tumor microenvironment (review). Int J Oncol 2017;50(5):1477‐1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Pan H‐y, L‐h Z, Y‐m D, Chen H, Huang B. Epidermal growth factor upregulates voltage‐gated sodium channel/Nav1. 5 expression and human breast cancer cell invasion. Basic Clin Med 2011;31:388‐393. [Google Scholar]

- 108. Uysal‐Onganer P, Djamgoz MB. Epidermal growth factor potentiates in vitro metastatic behaviour of human prostate cancer PC‐3M cells: Involvement of voltage‐gated sodium channel. Mol Cancer 2007;6:76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Pan H‐Y, Zhao Q, Zhan Y, Zhao L‐H, Zhang W‐H, Wu Y‐M. Vascular endothelial growth factor‐C promotes the invasion of cervical cancer cells via up‐regulating the expression of voltage‐gated sodium channel subtype Nav1. 6. Tumor 2012;32(5):313‐319. [Google Scholar]

- 110. Campbell TM, Main MJ, Fitzgerald EM. Functional expression of the voltage‐gated Na(+)‐channel Nav1.7 is necessary for EGF‐mediated invasion in human non‐small cell lung cancer cells. J Cell Sci 2013;126(Pt 21):4939‐4949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Cong D, Zhu W, Shi Y, et al. Upregulation of NHE1 protein expression enables glioblastoma cells to escape TMZ‐mediated toxicity via increased H+ extrusion, cell migration and survival. Carcinogenesis 2014;35(9):2014‐2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Lucien F, Brochu‐Gaudreau K, Arsenault D, Harper K, Dubois CM. Hypoxia‐induced invadopodia formation involves activation of NHE‐1 by the p90 ribosomal S6 kinase (p90RSK). PLoS One 2011;6(12):e28851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Schepkin VD, Elumalai M, Kitchen JA, Qian C, Gor'kov PL, Brey WW. In vivo chlorine and sodium MRI of rat brain at 21.1 T. Magn Reson Mater Phys Biol Med 2014;27(1):63‐70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Summers RM, Joseph PM, Kundel HL. Sodium nuclear magnetic resonance imaging of neuroblastoma in the nude mouse. Invest Radiol 1991;26(3):233‐241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]