Abstract

Many people believe in equality of opportunity, but overlook and minimize the structural factors that shape social inequalities in the United States and around the world, such as systematic exclusion (e.g., educational, occupational) based on group membership (e.g., gender, race, socioeconomic status). As a result, social inequalities persist, and place marginalized social groups at elevated risk for negative emotional, learning, and health outcomes. Where do the beliefs and behaviors that underlie social inequalities originate? Recent evidence from developmental science indicates that an awareness of social inequalities begins in childhood, and that children seek to explain the underlying causes of the disparities that they observe and experience. Moreover, children and adolescents show early capacities for understanding and rectifying inequalities when regulating access to resources in peer contexts. Drawing on a social reasoning developmental framework, this paper synthesizes what is currently known about children’s and adolescents’ awareness, beliefs, and behavior concerning social inequalities, and highlights promising avenues by which developmental science can help reduce harmful assumptions and foster a more just society.

Keywords: social inequality, social exclusion, moral development

Despite the fact that many people believe in equality of opportunity, many also overlook the structural factors that shape social and economic disparities in the United States and around the world. These structural factors include, for example, historical and current exclusion from residential, educational, and occupational opportunities on the basis of gender, race, socioeconomic status, or other group memberships (Bullock, 2019; Kraus et al., 2019). As a result, excluded social groups continue to have fewer opportunities for upward mobility and experience elevated risk for negative emotional, learning, and health outcomes (Duncan & Mumane, 2011; Wilkinson & Pickett, 2017). Psychological science plays a crucial role in illuminating the processes that underlie people’s responses to social inequality. For example, research has shown that social inequalities persist in part because many people under-estimate their true magnitude, are not motivated to correct disparities that benefit their social groups, or hold negative stereotypes about marginalized groups (Arsenio, 2018; Lott, 2012; Roberts & Rizzo, 2020). In order to address the psychological roots of these inequalities, we need to know where these beliefs and attitudes come from, and how we might encourage a more equitable and just understanding of the causes and consequences of social inequalities. In this paper, we offer a developmental perspective that begins to address these two questions.

In the past decade, developmental scientists have been at the forefront of efforts to understand how youth develop an awareness of social inequalities, seek explanations for their causes, form judgments of their consequences, and enact behavioral responses, based on their personal experiences with social inequalities and the influences of micro (e.g., family, peer) and macro (e.g., school, media) social contexts (Arsenio, 2015; Ruck et al., 2019). Although children have few direct opportunities to influence societal-level inequalities (e.g., through voting, protesting), they regularly experience social inequalities in their peer and family contexts, and take on a range of different roles (e.g., perpetuator, rectifier, victim, witness) within these inequalities (Killen et al., 2018). As a result, research is beginning to uncover not only the developmental processes that exacerbate social inequalities, but also potential pathways for promoting greater consideration of equity in childhood. In fact, developmental science is uniquely positioned to illuminate the factors that motivate children and adults to either ignore, exacerbate, or challenge social inequalities in their everyday interactions.

Social Reasoning Developmental Model

One branch of current research on how youth conceptualize social inequalities is informed by the social reasoning developmental (SRD) model (Killen et al., 2018; Rutland et al., 2010). The SRD model focuses on reasoning, judgments, and decisions about moral and social issues, and how these processes change across development. It integrates concepts from social domain theory (e.g., how children reason about social-conventional, moral, and personal concerns) and social identity theory (e.g., how intra- and inter-group dynamics shape decisionmaking) to provide a framework for understanding how children make sense of moral issues (e.g., denial of resources) that occur in inter-group contexts.

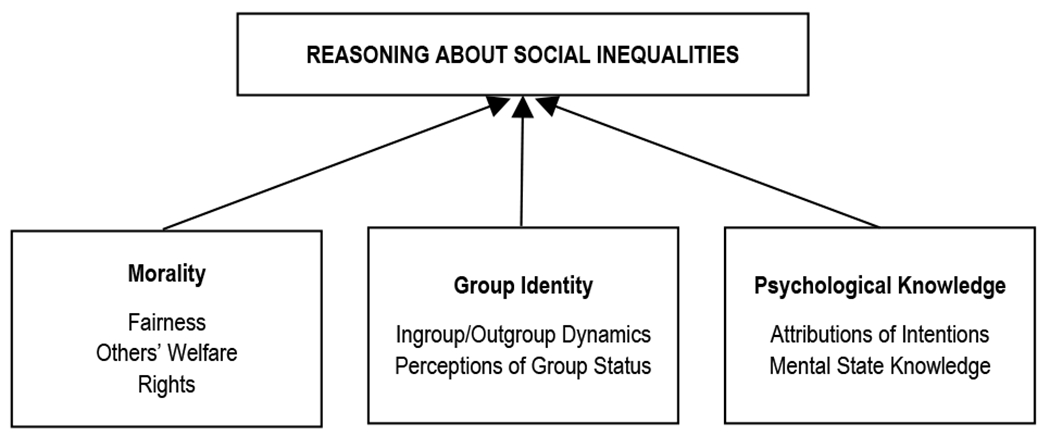

The SRD model takes a constructivist view in postulating that children’s social-cognitive development stems from their reflections and abstractions based on their everyday interactions which, in turn, enable them to infer, evaluate, and judge actions and events in their world (Killen & Rutland, 2011). In contrast to nativist or socialization perspectives, constructivist theories regarding the origins of social cognition emphasize the central role of the child in actively interpreting and making sense of their social world (Killen & Smetana, 2015; Turiel, 1983). Within this broader theoretical perspective, the SRD model proposes that reasoning about morality, group identity, and the psychological states of others emerges early in childhood and coexists throughout development (see Figure 1). Each of these domains of knowledge are brought to bear when children and adolescents consider complex issues, such as social inequalities. What changes across development is the complexity of children’s and adolescents’ moral reasoning, the depth of their understanding of social group dynamics, their awareness of others’ mental state capacities, and their ability to coordinate and balance these overlapping concerns.

Figure 1.

Social Reasoning Developmental (SRD) Model proposes that children and adolescents bring three forms of knowledge to bear on their reasoning about social inequalities: moral, group, and psychological.

In order to understand the orgins, development, and sources of influence on thinking about social inequalities, research from the SRD perspective has examined how children’s and adolescents’ understanding of moral, group, and psychological concepts are applied to their emerging: 1) awareness of social inequalities, 2) explanations for these inequalities, and 3) behavior aimed at increasing or reducing social inequalities. In this paper, we synthesize research from the SRD framework, as well as related research in developmental science, to outline what is currently known about children’s and adolescents’ awareness, beliefs, and behavior concerning social inequalities, and highlight promising avenues to encourage positive change.

Awareness of Social Inequalities

Being aware of social inequalities means recognizing the existence of disparities in access to resources or opportunities between social groups. On the most basic level, children are cognitively equipped to notice resource inequalities from early in development. Already in their first year of life, infants notice when someone has more toys than someone else (Sommerville, 2018). By the time they reach kindergarten, children attend to wealth inequalities, identifying their peers as “poor” or “rich”, alongside other forms of social categorization (e.g., gender, ethnicity) (Hazelbaker et al., 2018; Shutts, 2015). Over the course of adolescence, youth view U.S. society as increasingly economically stratified and also increasingly link economic status and race, associating White and Asian Americans with higher income and wealth than Black and Latinx Americans (Arsenio & Willems, 2017; Ghavami & Mistry, 2019). However, even adults under-estimate the true extent to which wealth is unequally distributed in society, as well as the true magnitude of current racial wealth gaps (Arsenio, 2018; Kraus et al., 2019).

Moreover, children’s own status or the status of their social group can lead them to deny or minimize the extent of social inequalities. For example, in one recent experiment, Rizzo and Killen (2020) randomly assigned 3- to 8 year-old children to either an advantaged group (had more resources than an outgroup) or a disadvantaged group (had fewer resources than an outgroup). Children assigned to the advantaged group were more likely to see the resource inequality as fair, support attempts to perpetuate the inequality, and keep more resources for their own group when given the chance.

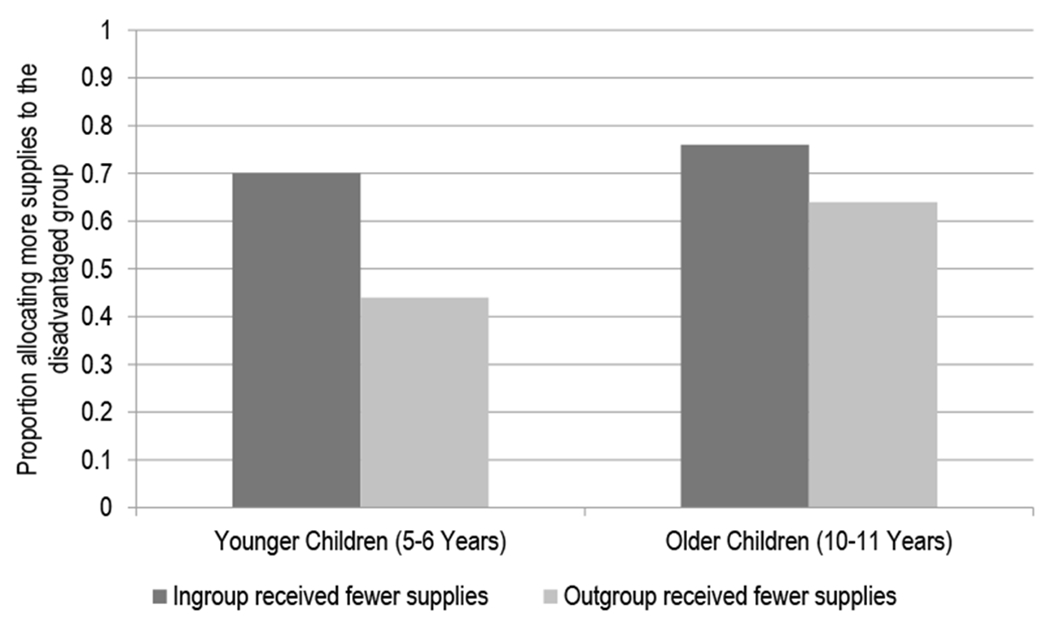

Similarly, Elenbaas and colleagues (2016) randomly assigned European-American and African-American children, ages 5- to 6 and 10- to 11 years, to witness an experimental inequality of school supplies that placed either their racial ingroup or outgroup at a disadvantage. Young children whose ingroup was disadvantaged judged the inequality to be unfair and took steps to correct it, but young children whose outgroup was disadvantaged did not (see Figure 2). Older children, by contrast, rectified the inequality under both conditions and reasoned about the importance of ensuring equal access to resources (e.g., “Both schools should have the same amount of supplies for learning”).

Figure 2.

Young children corrected a resource inequality that disadvantaged their racial ingroup but not an inequality that disadvantaged their outgroup.

From an SRD perspective, these results reveal what happens when children prioritize group concerns over moral concerns, and how the prioritization of these concerns develops during childhood. Whereas younger children in both studies struggled to balance concerns for ingroup benefit with concerns for equity, older children’s reasoning and decision-making reflected a more generalized concern for ensuring fair access to resources that took precedence over social preferences. Because ingroup concerns remain common throughout development, however, it is important to identify which social contexts enable children and adolescents to see the bigger picture and align their moral behavior with their moral judgments.

Explanations for Social Inequalities

Generating an explanation for a social inequality entails forming beliefs about how disparities in access to resources or opportunities between social groups came to be. Children and adolescents are able to consider multiple possible sources for social inequalities, and not all sources are perceived to be unfair (Arsenio & Willems, 2017; Flanagan et al., 2014; Starmans et al., 2017). For instance, many people –youth and adults– explain social inequalities in terms of traditions and authority, including the need to maintain a predictable status quo and the idea that it is normal or typical for some groups to succeed and others not to. Other explanations are moral in nature. For instance, social inequalities cause direct and indirect harm to members of marginalized groups as a result of systemic discrimination and are thus in need of rectification. Finally, many explanations weigh moral, societal (economic systems), and psychological rationales, including beliefs that economic systems are designed to give everyone an equal pportunity for upward mobility and that a certain amount of inequality in society is motivating for people.

By kindergarten, children believe that greater effort entitles an individual person to a greater share of rewards (e.g., someone who tries harder at a game deserves to keep their winnings) (Rizzo et al., 2016). However, when scaled up to the social group level, early-emerging judgments about merit can lead to negative stereotypes that marginalized and excluded groups “deserve” their status. For instance, young children stereotype poor peers as less competent than rich peers (Shutts et al., 2016). Similarly, children hold stereotypes that African-Americans are less hardworking than European-Americans and girls are less intelligent than boys (Bian et al., 2017; Pauker et al., 2016). In fact, although adolescents are more likely than children to generate structural explanations for social inequalities (e.g., systemic racism, classism, or sexism), these explanations typically exist alongside problematic assumptions about differences in social groups’ motivation, effort, and ingenuity, rather than replacing them (Flanagan et al., 2014; Godfrey et al., 2019).

Explaining the underlying causes of social inequalities is challenging because observing an existing disparity (e.g., a racial disparity in access to education) does not provide enough information to infer its cause, and because the messages that children receive (e.g., from adults, media sources) about the nature and origins of social inequalities are often incomplete or ambiguous. As a result, children’s awareness and understanding of the complex structural factors underlying social inequalities (e.g., political systems that exclude the poor, residential systems that exclude ethnic minorities, educational systems that exclude girls) is limited and interacts with other cognitive biases. For example, when children are asked to generate explanations for resource inequalities between novel groups (e.g., the Orps and the Blarks), children often assume that group differences resulted from internal factors (e.g., work ethic, natural ability) rather than external factors (e.g., discrimination) (Hussak & Cimpian, 2015).

Behavior in Contexts Involving Social Inequalities

Children’s and adolescents’ reasoning about the causes of social inequalities informs their thinking about what (if anything) should be done to address them. For example, in one experiment, Rizzo and colleagues (2018) tested 3- to 8-year-old children’s responses to individually-based inequalities (i.e., one peer received more prizes than another because they worked harder) or structurally-based inequalities (i.e., one peer received more prizes than another because the person giving out prizes had a gender bias). In response to the individually-based inequality, children gave more resources to the hardworking peer and reasoned about merit (e.g., “She did a better job at the activities”). In response to the structurally-based inequality, children gave more resources to the peer who had received less because of a gender bias and reasoned about equality (e.g., “They should get the same number”). These results confirm young children’s belief that individual effort should be rewarded, but also highlight emerging concerns for equity in response to structurally-based inequalities. When children had clear and unambiguous evidence that resources were allocated unjustly, they acted to correct the disparity.

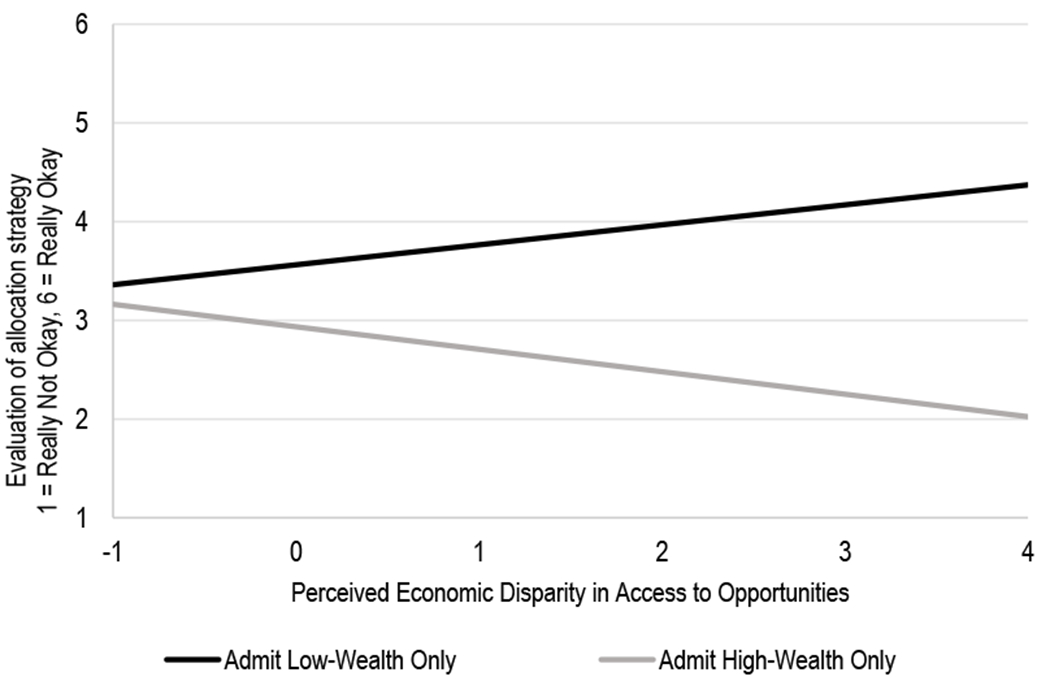

Similarly, one recent experiment informed early adolescents that access to an educational opportunity (a science summer camp) had historically been restricted such that only wealthy children or only poor children had attended (Elenbaas, 2019a). When they had the chance to determine who should attend the camp “this summer,” participants favored the group that had been excluded in the past, particularly when that group was poor. Moreover, the larger the economic “gap” in access to opportunities that participants perceived in broader society, the more they supported including poor peers in this particular opportunity (see Figure 3) and reasoned about fair access to learning (e.g., “Everyone has the right to education no matter what background they come from”).

Figure 3.

Early adolescents who perceived a larger economic “gap” in access to opportunities in favor of high-wealth peers were more supportive of including low-wealth peers in a learning opportunity.

These studies, both drawing on the SRD model to understand children’s and adolescents’ reasoning and behavior in contexts involving moral issues (differential access to resources and opportunities) on inter-group levels (involving gender or social class), have intriguing implications for how to reduce harmful stereotypes about the causes of social inequalities. When children know –from their own direct observations or from others’ testimony– that an inequality is rooted in structural discrimination or bias, most children support efforts to reduce it. The challenge is that children rarely receive this direct and unambiguous evidence. While the idea that anyone can achieve success with enough effort and ambition is widely available to children in national, social, and educational discourse, children receive far less consistent information about the historical and societal contexts for why some social groups are advantaged over others. However, this may offer a point of entry for adults interested in increasing children’s recognition of the complex structural causes of social inequalities.

Supporting Complex Reasoning about Social Inequalities

Providing opportunities for analysis and reflection on the sources and consequences of social inequalities may help youth develop a critical understanding of the social, economic, and political systems that they are a part of (Seider et al., 2018). For example, research on family racial-ethnic socialization indicates that conversations about discrimination can contribute to adolescents’ structural explanations for social inequalities (e.g., systemic racism) (Bañales et al., 2019). Similarly, research on civic engagement has shown that adolescents who frequently discuss current events with their parents have a better understanding of structural contributors to poverty (Flanagan et al., 2014). Likewise, research on critical consciousness indicates that discussions with parents, teachers, mentors, and peers can foster adolescents’ awareness of sociopolitical conditions and motivation to address social inequalities (Diemer et al., 2016). Although little research has examined the messages about social inequality that pre-adolescent children may receive, they, too, are becoming aware of social inequalities, and likely consider their parents’ and teachers’ opinions when forming beliefs about their causes.

Relationships with peers whose experiences differ from their own may also help youth reject stereotypes and develop a deeper understanding of social inequalities. For instance, research on inter-group contact indicates that having a friend from a different racial background is associated with lower racial stereotypes (Aboud & Brown, 2013). Similarly, cross-SES friendships may encourage children’s fairness reasoning. In one recent study, children from zupper-middle income families who reported more contact with peers from lower-income backgrounds were more likely to reason about differences in access to resources when sharing toys, and shared more equitably (Elenbaas, 2019b). Although, it is not yet known whether interactions with higher-SES peers have a similar impact on lower-SES children’s reasoning, these results point to how everyday interactions with friends may raise children’s consideration of the immediate consequences of resource disparities.

Future Directions for Research

Understanding children’s and adolescents’ thinking about social inequality is a new area of research in developmental science (Ruck et al., 2019). We now know that youth face challenges in becoming aware of the existence and extent of social inequalities, understanding their structural causes, and deciding how to address social inequalities. Moreover, both the potential for ingroup benefit and negative stereotypes about disadvantaged groups lead to more exclusive and inequitable behavior.

We also know, however, that children’s concerns for justice and fairness emerge early, and enable them to identify and work to correct instances of inequality within their sphere of influence. We suggest a continued research focus on the questions of origins and development that have framed a great deal of work in this area thus far, but also increased attention to the sources of influence on children’s thinking. Drawing on the constructivist perspective of the SRD model, we suggest that future studies investigate the joint and separate roles of interacting with diverse peers, interpreting conversations’ with parents and teachers, and reflecting on societal structures on children’s and adolescents’ reasoning, judgments, and behaviors in contexts of social inequality. Continued investigation of how children recognize, explain, and respond to social inequalities may provide a basis for ameliorating their detrimental outcomes and fostering a more just society.

Acknowledgements

Melanie Killen was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation, BCS1728918 and the National Institutes of Health, NICHDR01HD093698 while working on this paper.

References

- Aboud FE, & Brown CS (2013). Positive and negative intergroup contact among children and its effect on attitudes. In Hodson G & Hewstone M (Eds.), Advances in intergroup contact (pp. 176–199). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Arsenio WF (2015). Moral psychological perspectives on distributive justice and societal inequalities. Child Development Perspectives, 9(2), 91–95. 10.1111/cdep.12115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; A social domain theory perspective on how individuals understand and morally evaluate the distribution of societal resources

- Arsenio WF (2018). The wealth of nations: International judgments regarding actual and ideal resource distributions. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 27(5), 357–362. 10.1177/0963721418762377 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arsenio WF, & Willems C (2017). Adolescents’ conceptions of national wealth distribution: Connections with perceived societal fairness and academic plans. Developmental Psychology, 53(3), 463–474. 10.1037/dev0000263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bañales J, Marchand AD, Skinner OD, Anyiwo N, Rowley SJ, & Kurtz-Costes B (2019). Black adolescents’ critical reflection development: Parents’ racial socialization and attributions about race achievement gaps. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 30(S2), 403–417. 10.1111/jora.12485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bian L, Leslie SJ, & Cimpian A (2017). Gender stereotypes about intellectual ability emerge early and influence children’s interests. Science, 355(6323), 389–391. 10.1126/science.aah6524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock ΗE (2019). Psychology’s contributions to understanding and alleviating poverty and economic inequality: Introduction to the special section. American Psychologist, 74(6), 635–640. 10.1037/amp0000532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diemer MA, Rapa LJ, Voight AM, & McWhirter EH (2016). Critical consciousness: A developmental approach to addressing marginalization and oppression. Child Development Perspectives, 10(4), 216–221. 10.1111/cdep.12193 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, & Murnane RJ (Eds.). (2011). Whither opportunity? Rising inequality, schools, and children’s life chances. Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Elenbaas L (2019a). Perceptions of economic inequality are related to children’s judgments about access to opportunities. Developmental Psychology, 55(3), 471–481. 10.1037/dev0000550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elenbaas L (2019b). Interwealth contact and young children’s concern for equity. Child Development, 90(1), 108–116. 10.1111/cdev.13157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elenbaas L, Rizzo MT, Cooley S, & Killen M (2016). Rectifying inequalities in a resource allocation task. Cognition, 155, 176–187. 10.1016/j.cognition.2016.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan CA, Kim T, Pykett A, Finlay A, Gallay EE, & Pancer M (2014). Adolescents’ theories about economic inequality: Why are some people poor while others are rich? Developmental Psychology, 50(11), 2512–2525. 10.1037/a0037934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghavami N, & Mistry RS (2019). Urban ethnically diverse adolescents’ perceptions of social class at the intersection of race, gender, and sexual orientation. Developmental Psychology, 55(3), 457–470. 10.1037/dev0000572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey EB, Santos CE, & Burson E (2019). For better or worse? System-justifying beliefs in sixth grade predict trajectories of self esteem and behavior across early adolescence. Child Development, 90( 1), 180–195. 10.1111/cdev.12854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazelbaker T, Griffin KM, Nenadal L, & Mistry RS (2018). Early elementary school children’s conceptions of neighborhood social stratification and fairness. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 4(2), 153–164. 10.1037/tps0000153 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hussak LJ, & Cimpian A (2015). An early-emerging explanatory heuristic promotes support for the status quo. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109(5), 739–752. 10.1037/pspa0000033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killen M, Elenbaas L, & Rizzo MT (2018). Young children’s ability to recognize and challenge unfair treatment of others in group contexts. Human Development, 61(4), 281– 296. 10.1159/000492804. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; A social reasoning developmental perspective on how young children’s emerging understanding of group membershp and mental states prepares them to challenge the unfair treatment of peers.

- Killen M, & Rutland A (2011). Children and social exclusion: Morality, prejudice, and group identity. Wiley/Blackwell Publishers, 10.1002/9781444396317 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Killen M, & Smetana JG (2015). Origins and development of morality. In Lamb ME (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology and developmental science, Vol. 3 (7th ed., pp. 701–749). Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus MW, Onyeador IN, Daumeyer NM, Rucker JM, & Richeson JA (2019). The misperception of racial economic inequality. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14(6), 899–921. 10.1177/1745691619863049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lott B (2012). The social psychology of class and classism. American Psychologist, 67(8), 650–658. 10.1037/a0029369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauker K, Xu Y, Williams A, & Biddle AM (2016). Race essentialism and social contextual differences in children’s racial stereotyping. Child Development, 57(5), 1409– 1422. 10.1111/cdev.12592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo MT, Elenbaas L, Cooley S, & Killen M (2016). Children’s recognition of fairness and others’ welfare in a resource allocation task: Age related changes. Developmental Psychology, 52(8), 1307–1317. 10.1037/dev0000134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo MT, Elenbaas L, & Vanderbilt KE (2018). Do children distinguish between resource inequalities with individual versus structural origins? Child Development. 10.1111/cdev.13181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo MT, & Killen M (2020). Children’s evaluations of individually- and structurally-based inequalities: The role of status. Manuscript Submittedfor Publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts SO, & Rizzo MT (2020). The psychology of American racism. American Psychologist, 10.1037/amp0000642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruck MD, Mistry RS, & Flanagan CA (2019). Children’s and adolescents’ understanding and experiences of economic inequality: An introduction to the special section. Developmental Psychology, 55(3), 449–456. 10.1037/dev0000694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; An overview of a special section on youths’ perceptions, experiences, and reasoning about economic inequality.

- Rutland A, Killen M, & Abrams D (2010). A new social-cognitive developmental perspective on prejudice: The interplay between morality and group identity. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5(3), 279–291. 10.1177/1745691610369468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seider S, Kelly L, Clark S, Jennett P, El-Amin A, Graves D, Soutter M, Malhotra S, & Cabral M (2018). Fostering the sociopolitical development of African American and Latinx adolescents to analyze and challenge racial and economic inequality. Youth and Society, 1–39. 10.1177/0044118X18767783 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shutts K (2015). Young children’s preferences: Gender, race, and social status. Child Development Perspectives, 9(4), 262–266. 10.1111/cdep.12154 . [DOI] [Google Scholar]; A social categorization perspective on children’s attitudes about gender, race, and social class

- Shutts K, Brey EL, Dornbusch LA, Slywotzky N, & Olson KR (2016). Children use wealth cues to evaluate others. PLoS ONE, 77(3), e0149360. 10.1371/journal.pone.0149360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommerville JA (2018). Infants’ understanding of distributive fairness as a test case for identifying the extents and limits of infants’ sociomoral cognition and behavior. Child Development Perspectives, 12(3), 141–145. 10.1111/cdep.12283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starmans C, Sheskin M, & Bloom P (2017). Why people prefer unequal societies. Nature Human Behaviour, 7(4), 0082. 10.1038/s41562-017-0082 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turiel E (1983). The development of social knowledge: Morality and convention. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson RG, & Pickett KE (2017). The enemy between us: The psychological and social costs of inequality. European Journal of Social Psychology, 47(1), 11–24. 10.1002/ejsp.2275 [DOI] [Google Scholar]