Abstract

Topological structures are effective descriptors of the non-equilibrium dynamics of diverse many-body systems. For example, motile point-like topological defects capture the salient features of two-dimensional active liquid crystals composed of energy-consuming anisotropic units. We disperse force-generating microtubule bundles in a passive colloidal liquid crystal to form a three-dimensional active nematics. Light-sheet microscopy reveals the temporal evolution of the millimeter-scale structure of these active nematics with single-bundle resolution. The primary topological excitations are extended charge-neutral disclination loops that undergo complex dynamics and recombination events. Our work suggests a framework for analyzing the non-equilibrium dynamics of bulk anisotropic systems as diverse as driven complex fluids, active metamaterials, biological tissues and collections of robots or organisms.

One Sentence Summary:

Light sheet microscopy reveals the chaotic behavior of topologically neutral disclination loops in active nematics.

The sinuous change in the orientation of birds flocking is a common but startling sight. Even if one can track the orientation of each bird, making sense of such large data sets is difficult. Similar challenges arise in disparate contexts from magnetohydrodynamics (1) to turbulent cultures of elongated cells (2), where oriented fields coupled to velocity undergo complex dynamics. To make progress with such extensive three-dimensional data, it is useful to identify effective degrees of freedom that allow a coarse-grained description of the collective non-equilibrium phenomena. Promising candidates are singular field configurations locally protected by topological rules (3-9). Examples of such singularities in two dimensions are the topological defects that appear at the north and south poles when covering the Earth’s surface with parallel lines of longitude or latitude. These point-defects are characterized by the winding number of the corresponding orientation field.

The quintessential systems with orientational order are nematic liquid crystals, fluids composed of anisotropic molecules. In equilibrium, nematics tend to minimize energy by uniformly aligning their anisotropic constituents, which annihilates topological defects. By contrast, in active nematic materials, which are internally driven away from equilibrium, the continual injection of energy destabilizes defect-free alignment (10, 11). The resulting chaotic dynamics is effectively represented in two dimensions by point-like topological defects that behave as self-propelled particles (12-16). The defect-driven dynamics of 2D active nematics has been observed in many systems ranging from millimeter-sized shaken granular rods and micron-sized motile biological cells to nano-scale motor-driven biological filaments (17-23). Several obstacles have hindered generalizing topological dynamics of active nematics to three dimensions. The higher dimensionality expands the space of possible defect configurations. Discriminating between different defect types requires measurement of the spatiotemporal evolution of the director field on macroscopic scales using materials that can be rendered active away from surfaces.

The 3D active nematics we assemble are based on microtubules and kinesin molecular motors. In presence of a depleting agent these components assemble into isotropic active fluids which exhibit persistent spontaneous flows (17). Replacing a broadly acting depletant with a specific microtubule crosslinker, PRC1-NS, enabled assembly of a composite mixture of low density extensile microtubule bundles (~0.1% volume fraction) and a passive colloidal nematic based on filamentous viruses (Fig. 1A), a strategy that is similar to work on the living liquid crystal (21). ATP fueled stepping of kinesin motors generates microtubule bundle extension and active stresses that drive the chaotic dynamics of the entire system (Movie S1). Birefringence of the composite material indicates local nematic order, in contrast to active fluids lacking the passive liquid crystal component (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1:

Assembling 3D active nematics and imaging their director field. (A) Schematic of the 3D active nematic system: active stress generating extensile microtubule bundles are dispersed in a passive colloidal liquid crystal. (B) Active 3D nematic imaged with widefield fluorescent microscopy (left) and polarized microscopy (right). Birefringence indicates local nematic order. (C) Multi-view light sheet microscopy allows for 3D imaging of millimeter sized samples with single-bundle resolution. (D) (left) A 2D slice of fluorescent microtubule bundles, with highlighted elastic distortions. (right) Corresponding elastic distortion energy map, with an overlaid nematic director field (red). (E) Three-dimensional elastic distortion map reveals presence of curvilinear rather than point-like singularities. An entangled network of lines coexists with isolated loops. (F) Hybrid lattice Boltzmann simulations yield a similar structure of 3D active nematics. All experimental samples consist of passive fd viruses at 25mg/mL and microtubules at 1.33mg/mL.

Elucidating the spatial structure of a 3D active nematic requires measurement of the nematic director field on scales from microns to millimeters. Furthermore, uncovering its dynamics requires acquisition of the director field with high temporal resolution. To overcome these constraints, we used a multi-view light-sheet microscope (Fig. 1C) (24). The spatiotemporal evolution of the nematic director field n(x,t) was extracted from a stack of fluorescent images using the structure tensor method. Spatial gradients of the director field identified regions with large elastic distortions (Fig. 1D, Movie S2). Three-dimensional reconstruction of such maps revealed that large elastic distortions mainly formed curvilinear structures, which could either be isolated loops, or belong to a complex network of system-spanning lines (Fig. 1E, Movie S3). These curvilinear distortions are topological disclination lines characteristic of 3D nematics. Similar structures were observed in numerical simulations of 3D active nematic dynamics, using either a hybrid lattice Boltzmann method or a finite difference Stokes solver numerical approach (Fig. 1F) (25, 26).

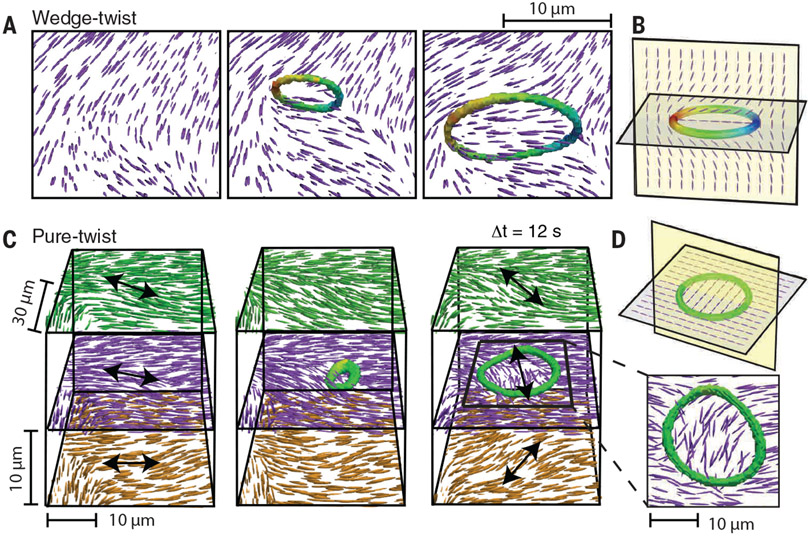

Reducing the ATP concentration slowed down the chaotic flows, which revealed the temporal dynamics of the nematic director field. In turn, this identified the basic events governing the dynamics of disclination lines (Movie S4). We focused on characterizing the closed-loop disclinations, as they are the objects seen to arise or annihilate in the bulk. Isolated loops nucleated and grew from undistorted, uniformly aligned regions (Fig. 2A; Fig. S1, S2; Movie S5). Likewise, loops also contracted and self-annihilated, leaving behind a uniform region (Fig. 2B, Fig. S1, S2, Movie S6). Furthermore, expanding loops frequently encountered and subsequently merged with the system-spanning network of distortion lines, while the distortion lines in the network self-intersected and reconnected to emit a new isolated loop (Fig. 2C,D, Fig. S1, S2; Movie S7, S8).

Fig. 2:

Dynamics of experimentally observed disclination loops. (A) Loop nucleation from a defect-free region. (B) Loop self-annihilation leaves behind a defect-free nematic. (C) A disclination line self-intersects, reconnects, and emits a loop. (D) A disclination loop intersects, reconnects and merges with a disclination line. Each bounding box is 30 μm *30 μm *38 μm. The time interval between two pictures is 12 seconds.

Topological constraints require that topological defects can only be created in sets that are, collectively, topologically neutral. Point-like defects in 2D active nematics thus always nucleate as pairs of opposite winding number (13). In 3D active nematics, a disclination loop as a whole has two topological possibilities: it can either carry a monopole charge or be topologically neutral, depending on its director winding structure. Since charged topological loops can only appear in pairs, nucleation of isolated loops as observed in our system implies their topological neutrality.

To establish that the closed-loop distortions are nematic disclination loops with no net charge, we characterized their topological structure. In 2D nematics, point-like disclination defects are characterized by s, the winding number or a topological charge. The lowest-energy disclinations have s = ±1/2, which correspond to a π rotation of the director field in the same sense or the opposite sense, respectively, as the traversal of any closed path encircling only the defect of interest. In 3D nematics, point-like defects from 2D systems are generalized to disclination lines, where the director similarly has a π winding, affording a broader variety of director configurations. We define t to be the disclination line’s local tangent unit vector. The director field winds by π about a direction specified by Ω, the rotation vector, which can make an arbitrary angle β with t (27). If Ω points antiparallel or parallel to t, the local director field twists in the plane orthogonal to t, assuming the disclination profiles familiar from 2D nematics. These configurations where β is equal to 0 or π are said to locally have a wedge winding (Fig. 3A). If Ω is perpendicular to t, β = π /2 and the director forms a spatially varying angle away from the orthogonal plane, locally creating what is termed a twist winding. Because Ω may point in any direction relative to t, both Ω and β can vary continuously along a disclination line (Movie S9).

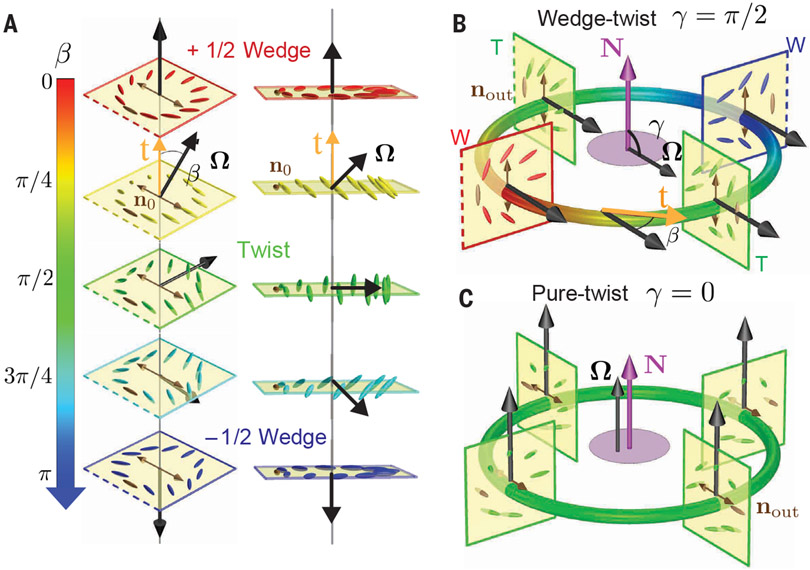

Fig. 3:

Structure of disclinations lines, wedge-twist and pure-twist loops. (A) Disclination line where a local +1/2 wedge winding continuously transforms into −1/2 wedge through an intermediate twist winding. The director field winds by π about the rotation vector Ω (black arrows), which makes angle β with the tangent t (orange arrow), and which is orthogonal to director field everywhere in each slice. For ±1/2 wedge windings, β=0 and π. β=π/2 indicates local twist winding. Reference director n0 (brown) is held fixed. Color map indicates angle β. (B) The wedge-twist loop where local winding as reflected by angle β varies along the loop. Ω is spatially uniform and forms an angle γ=π/2 with the loop’s normal, N. The winding in the four illustrated planes corresponds to the profiles of the same colors shown in (A), with dashed edges of squares aligned to show the local director field. Double-headed brown arrows indicate nout, the director just outside the loop. (C) Pure-twist loop, with Ω both uniformly parallel to loop normal N (γ=0) and perpendicular to the tangent vector.

For disclination lines forming loops, Ω can vary continuously providing it returns to its original orientation upon closure, leading to a broad range of possible winding variations. A family of loops of particular relevance to 3D active nematics is characterized by a spatially uniform Ω, interpolating between two emblematic geometries: wedge-twist and pure-twist loops. In the wedge-twist loop, Ω makes an angle γ = π/2 with the loop normal N (Fig. 3B). As the disclination’s tangent t rotates by 2π upon traveling around the loop, the angle β varies from 0 (+1/2 wedge) to π/2 (twist), to π (–1/2 wedge), then back to π/2 and returning to 0 (Movie S9) (27, 28). The pure-twist loop has Ω uniformly parallel to N, so γ = 0 and Ω is perpendicular to t (β = π/2, twist profile) at all points on the loop (Fig. 3C) (27, 29). In this family of loops, the director just outside the loop, nout, is also uniform. The lack of a winding of both Ω and nout implies that both wedge-twist and pure-twist loops are topologically neutral (30, 31).

Experimental measurements of the director field allowed the fully characterization the topological structure of the disclination loops (Fig 4). Analysis of the director field indicated that the distortion lines and loops have the π winding indicative of disclinations (Fig. 1E,F), with continuous variation of β which indicates the local winding. Furthermore, a majority of the analyzed loops were well approximated by the family of curves where Ω and nout varied little along the loop circumferences. Categorizing loops according to their γ values revealed that the entire continuous family from wedge-twist (Fig. 4A, B) to pure-twist (Fig. 4C) was represented, with later being more prevalent (Fig. 4D). Structural analysis revealed topological neutrality, as all 268 experimental loops and all 94 loops extracted from hybrid lattice Boltzmann simulations carried no charge. This demonstrates that among many possible configurations, topologically neutral loops are the dominant excitation mode of 3D active nematics. The same class of loop geometries also dominated the dynamics in our numerical simulations of bulk 3D active nematics and in confined active nematics (Fig. 4E, F) (32, 33). The phenomenology observed is a direct consequence of activity-induced flows and is insensitive to backflows induced by reactive stresses. This conclusion is supported by the agreement of results from the mechanical model considered in the hybrid lattice Boltzmann method and the purely kinematic Stokes method.

Fig. 4:

Structure of disclination loops in experiments and theory. (A) Two orthogonal views of an experimental wedge-twist loop overlaid onto a fluorescent image of the microtubules. The nematic director is in red. (B and E) Structure of wedge-twist disclination loops in experiments and simulation. (C and F) Structure of pure-twist disclination loops from experiment and simulation Panels show the director field’s winding in the corresponding cross-sections on the experimental loops. (D) Distribution of loop types extracted from experiment (N=268) and hybrid lattice Boltzmann simulations (N=94). ∣cos(γ)∣=0 for wedge-twist loops and 1 for pure-twist loops. Distributions of standard deviations of ∣cos(γ)∣ are shown in Fig. S3. The count of simulated loops includes analysis of some loops at multiple time points, as we do not track loop identity in the complex flow dynamics. Coloring of loops indicates the angle β. Scales and bounding boxes for the loops are shown in Fig. S4.

In 2D active nematics, self-amplifying bend distortions give rise to the nucleation of a pair of topological defects of opposite charge (12-18). Nucleation of isolated topologically neutral wedge-twist loops are the three-dimensional analog of defect creation process. Specifically, a cross-section through the +1/2 and −1/2 wedge profile recalls unbinding of a pair of point-disclinations in 2D (Fig. 5A,B). The +1/2 wedge profile typically appears on the side of the growing bend distortion, oriented away from the −1/2 wedge profile. Similarly, wedge-twist loops with the +1/2 wedge profile oriented inward towards the −1/2 wedge are driven to shrink by active and passive stresses. Unlike in 2D active nematics, after nucleation the wedge profiles remain bound to each other through a disclination loop that includes points with a local twist winding. It is possible that some analyzed pure-twist loop have evolved from wedge-twist loops by continuous deformation of local winding character. However, both simulations and experiments show cases of loop nucleation in nearly pure-twist γ≈0 geometries from previously defect-free regions. Local active nematic stresses alone are not expected to drive growth of a pure-twist loop (Fig 5D). One possibility is that long-range hydrodynamic flows built up twist distortions that locally relax through creation of a pure-twist loop (Fig. 5C, Movie S10).

Fig. 5:

Nucleation mechanism of wedge-twist and pure-twist loops. (A) Nucleation and growth of a wedge-twist disclination loop through a self-amplifying bend distortion. Purple rods represent the 2D director field through the local ±1/2 wedge profiles. (B) Schematic of a wedge-twist loop and the director field in the plane that intersects ±1/2 wedge profiles. (C) A pure-twist disclination loop nucleates and grows from a local twist distortion (Movie S10). Black arrows indicate the local buildup of the twist distortion. Insert shows the top view of a growing twist disclination loop. (D) Schematic of a pure-twist loop and the director field in the loop’s plane.

By coupling a flow field to an orientational order parameter with curvilinear topological defects, 3D active nematics display dynamics even more complex than the chaotic flows of 2D active systems. Combined with emerging theoretical work (32, 33), the developed experimental model system offers a platform to investigate the role of topology, dimensionality, and material order in the chaotic internally driven flows of active soft matter. Furthermore, the use of a multi-view light-sheet imaging technique demonstrates its potential to unravel dynamical processes in diverse non-equilibrium soft materials, such as relaxation of nematic liquid crystals upon a quench or their deformation under external shear flow (3, 34).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

We thank Bezia Lemma, Radhika Subramanian and Marc Ridilla for their help in protein purification. D.A.B. acknowledges S. Čopar, S. Žumer and M. Ravnik for helpful discussions on disclinations in 3D active nematics.

Funding: Experimental work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, through award DE-SC0019733 (G.D., R.A. I.K. and Z.D.). G.D. and I.K. also acknowledge support of HFSP fellowships. R.A. acknowledges support of NSF-GRFP. Theoretical modeling was supported by NSF-DMR-1855914, NSF-MRSEC-1420382 and NSF-CBET-1437195 (D.A.B., M.P., M.V. Ar.B, Ap.B, M.F.H, R.P. and T. P.). Computational resources were provided by the NSF through XSEDE computing resources (MCB090163) and TU/e through the F&F computing cluster. We also cknowledge use of the Brandeis optical, HPCC, and biosynthesis facilities supported by NSF-MRSEC-1420382. D.B. was supported by FOM and NWO. V.V. was supported by Army Research Office under grant W911NF-19-1-0268. S.J.S. was supported by a NIH-R00 award (5R00HD088708-05). D.A.B. thanks the Isaac Newton Institute for Mathematical Sciences for support during the program “The mathematical design of new materials,” supported by EPSRC grant number EP/R014604/1.

Footnotes

References and Notes:

- 1.Galtier S, Introduction to Modern Magnetohydrodynamics. (Cambridge University Press, ed. 1, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blanch-Mercader C et al. , Turbulent Dynamics of Epithelial Cell Cultures. Phys Rev Lett 120, 208101 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowick MJ, Chandar L, Schiff EA, Srivastava AM, The cosmological Kibble mechanism in the laboratory: string formation in liquid crystals. Science 263, 943–945 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poulin P, Stark H, Lubensky T, Weitz D, Novel colloidal interactions in anisotropic fluids. Science 275, 1770–1773 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bausch A et al. , Grain boundary scars and spherical crystallography. Science 299, 1716–1718 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Irvine WT, Vitelli V, Chaikin PM, Pleats in crystals on curved surfaces. Nature 468, 947 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scheeler MW, van Rees WM, Kedia H, Kleckner D, Irvine WT, Complete measurement of helicity and its dynamics in vortex tubes. Science 357, 487–491 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martinez A et al. , Mutually tangled colloidal knots and induced defect loops in nematic fields. Nature materials 13, 258 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tkalec U, Ravnik M, Čopar S, Žumer S, Muševič I, Reconfigurable knots and links in chiral nematic colloids. Science 333, 62–65 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simha RA, Ramaswamy S, Hydrodynamic fluctuations and instabilities in ordered suspensions of self-propelled particles. Physical review letters 89, 058101 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marenduzzo D, Orlandini E, Cates M, Yeomans J, Steady-state hydrodynamic instabilities of active liquid crystals: Hybrid lattice Boltzmann simulations. Physical Review E 76, 031921 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shankar S, Ramaswamy S, Marchetti MC, Bowick MJ, Defect unbinding in active nematics. Physical review letters 121, 108002 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giomi L, Bowick MJ, Mishra P, Sknepnek R, Cristina Marchetti M, Defect dynamics in active nematics. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 372, 20130365 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gao T, Blackwell R, Glaser MA, Betterton MD, Shelley MJ, Multiscale polar theory of microtubule and motor-protein assemblies. Physical review letters 114, 048101 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thampi SP, Golestanian R, Yeomans JM, Instabilities and topological defects in active nematics. EPL (Europhysics Letters) 105, 18001 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shi X.-q., Ma Y.-q., Topological structure dynamics revealing collective evolution in active nematics. Nature Communications 4, (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanchez T, Chen DT, DeCamp SJ, Heymann M, Dogic Z, Spontaneous motion in hierarchically assembled active matter. Nature 491, 431 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Narayan V, Ramaswamy S, Menon N, Long-lived giant number fluctuations in a swarming granular nematic. Science 317, 105–108 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawaguchi K, Kageyama R, Sano M, Topological defects control collective dynamics in neural progenitor cell cultures. Nature 545, 327 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saw TB et al. , Topological defects in epithelia govern cell death and extrusion. Nature 544, 212 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou S, Sokolov A, Lavrentovich OD, Aranson IS, Living liquid crystals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 111, 1265–1270 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumar N, Zhang R, de Pablo JJ, Gardel ML, Tunable structure and dynamics of active liquid crystals. Science advances 4, eaat7779 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li H et al. , Data-driven quantitative modeling of bacterial active nematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116, 777–785 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krzic U, Gunther S, Saunders TE, Streichan SJ, Hufnagel L, Multiview light-sheet microscope for rapid in toto imaging. Nature methods 9, 730 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Experimental director field data, the code to detect and analyze the topological loops and the Stokes solver are available on data sharing platform Dryad accessible at 10.25349/D9CS31. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lattice Boltzmann code and director generated by this code are available at 10.4121/uuid:5c8ea40a-19d5-4ecb-893a-c93f238a494c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Friedel J, De Gennes P, Boucles de disclination dans les cristaux liquides. CR Acad. Sc. Paris B 268, 257–259 (1969). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Emeršič T et al. , Sculpting stable structures in pure liquids. Science advances 5, eaav4283 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Terentjev E, Disclination loops, standing alone and around solid particles, in nematic liquid crystals. Physical Review E 51, 1330 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alexander GP, Chen B. G.-g., Matsumoto EA, Kamien RD, Colloquium: Disclination loops, point defects, and all that in nematic liquid crystals. Reviews of Modern Physics 84, 497 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Čopar S, Žumer S, Quaternions and hybrid nematic disclinations. Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 469, 20130204 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Čopar S, Aplinc J, Kos Ž, Žumer S, Ravnik M, Topology of three-dimensional active nematic turbulence confined to droplets. Physical Review X 9, (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shendruk TN, Thijssen K, Yeomans JM, Doostmohammadi A, Twist-induced crossover from two-dimensional to three-dimensional turbulence in active nematics. Physical Review E 98, 010601 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lavine MS, Windle AH, Computational modelling of disclination loops under shear flow. Macromol. Symp 124, 35–47 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Castoldi M, Popov AV, Purification of brain tubulin through two cycles of polymerization–depolymerization in a high-molarity buffer. Protein expression and purification 32, 83–88 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hyman A et al. , in Methods in enzymology. (Elsevier, 1991), vol. 196, pp. 478–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.DeCamp SJ, Redner GS, Baskaran A, Hagan MF, Dogic Z, Orientational order of motile defects in active nematics. Nature materials 14, 1110 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martin DS, Fathi R, Mitchison TJ, Gelles J, FRET measurements of kinesin neck orientation reveal a structural basis for processivity and asymmetry. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107, 5453–5458 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chandrakar P et al. , Microtubule-based active fluids with improved lifetime, temporal stability and miscibility with passive soft materials. arXiv preprint arXiv:1811.05026, (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Subramanian R et al. , Insights into antiparallel microtubule crosslinking by PRC1, a conserved nonmotor microtubule binding protein. Cell 142, 433–443 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T, Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. (Cold spring harbor laboratory press, 1989). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barry E, Beller D, Dogic Z, A model liquid crystalline system based on rodlike viruses with variable chirality and persistence length. Soft Matter 5, 2563–2570 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Streichan SJ, Lefebvre MF, Noll N, Wieschaus EF, Shraiman BI, Global morphogenetic flow is accurately predicted by the spatial distribution of myosin motors. Elife 7, e27454 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schindelin J et al. , Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nature methods 9, 676 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Preibisch S et al. , Efficient Bayesian-based multiview deconvolution. Nature methods 11, 645 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rezakhaniha R et al. , Experimental investigation of collagen waviness and orientation in the arterial adventitia using confocal laser scanning microscopy. Biomechanics and modeling in mechanobiology 11, 461–473 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao J, Wang Q, Semi-discrete energy-stable schemes for a tensor-based hydrodynamic model of nematic liquid crystal flows. Journal of Scientific Computing 68, 1241–1266 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vanka SP, Block-implicit multigrid calculation of two-dimensional recirculating flows. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering 59, 29–48 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kleman M, Friedel J, Disclinations, dislocations, and continuous defects: A reappraisal. Reviews of Modern Physics 80, 61 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jänich K, Topological properties of ordinary nematics in 3-space. Acta Applicandae Mathematica 8, 65–74 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tran L et al. , Lassoing saddle splay and the geometrical control of topological defects. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113, 7106–7111 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lozano-Durán A, Borrell G, Algorithm 964: an efficient algorithm to compute the genus of discrete surfaces and applications to turbulent flows. ACM Transactions on Mathematical Software (TOMS) 42, 34 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Toriwaki J, Yonekura T, Euler number and connectivity indexes of a three dimensional digital picture. FORMA-TOKYO- 17, 183–209 (2002). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.