Abstract

Policy Points.

That child and adolescent mental health services needs are frequently unmet has been known for many decades, yet few systemic solutions have been sought and fewer have been implemented at scale.

Key among the barriers to improving child and adolescent mental health services has been the lack of well‐organized primary mental health care. Such care is a mutual but uncoordinated responsibility of multiple disciplines and agencies.

Achieving consensus on the essential structures and processes of mental health services is a feasible first step toward creating an organized system.

Keywords: mental health services, child, consensus, interdisciplinary communication

Mental health (mh) is a state of well‐being in which individuals realize their own abilities, can cope with the common stresses of life, can have fulfilling relationships with other people, can work productively, and fruitfully, and are able to make a contribution to their community. 1 Mental illness refers to the impairment of various roles and functions that take on different terms and meanings depending on the perspective from which one approaches the field. Depending on whether one is a psychiatrist, psychologist, social worker, pediatrician, educator, attorney, a child or adolescent, a parent, or someone else, a person's identification of a MH problem, its labeling, and its treatment goals and strategies will differ. This variability suggests that MH care for many children and adolescents is in disarray and that the services available to help them have serious shortcomings.

Children's Mental Health

Prevalence

Estimates of the prevalence of child MH conditions, utilization rates, and access to services vary depending on the data source, though most studies show roughly equivalent demographic patterns and ranges of occurrence. In 2016, 16.5% of the population had at least one mental health disorder nationally. 2 Another study found that approximately one‐fourth of youths had experienced a mental disorder during the previous year and about one‐third had had one during their lifetime. The forms of these disorders range from anxiety, depression, and behavioral problems to serious emotional disturbances that meet strict diagnostic criteria.

The rates of internalizing among adolescents have increased and require active outreach and screening to identify. 3 About one out of every ten youths is estimated to meet the criteria for a serious emotional disturbance, 4 and these conditions have driven most publicly funded system improvement efforts. The prevalence of emotional disorders varies according to children's ages and development, as well as their social circumstances. 5 Youth suicide rates, a relatively reliable measure of youth MH, is the second leading cause of death among youth aged 10 to 19. During the past two decades, the number of youth suicides has increased by 33%. 6 These rates and trends are receiving greater attention from the public and professionals as the concept of traumatic stressful experiences has become more familiar. 7

Utilization

The number of hospitalizations for child and adolescent mental disorders has risen as well. Between 2006 and 2011, this number increased by 86.2% for 5‐ to 9‐year‐olds, 79.4% for 10‐ to 14‐year‐olds, and 54.8% for 15‐ to 17‐year‐olds. All these age groups had a disproportionate increase in the number of hospitalizations for suicide and self‐injury. Moreover, for children aged 10 to 14, the number of inpatient hospitalizations for mental illness and substance abuse rose by 76.2%. 8 Similarly, during that same time period, the number of MH‐related emergency department (ED) visits was largely driven by a 60.9% increase in ED visits for behavioral disorders. The number of ED visits for suicide and self‐injury also increased: by 87.9% for 5‐ to 9‐year‐olds, 50.1% for 10‐ to 14‐year‐olds, and 27.8% for 15‐ to 17‐year‐olds. 8 , 9 We have less utilization data for younger children, probably because of their lower incidence of serious emotional disturbances, their more rapid development, and the heterogeneity of their sources of care.

Access and Unmet Need

The unmet need for MH services is an old and continuing reality, whether due to MH problems not being recognized or to services being unavailable or unused for various personal and social reasons. Study findings vary, but generally—even more than is the case for adults—most children and youths needing MH services do not receive them. 10 , 11 , 12 , 13

Children with more serious and thus more troublesome and evident diagnoses are more likely to receive care. 14 Nonetheless, it is estimated that of the two million youths aged 12 to 17 in 2007 who met the criteria for a major depressive episode, only 39% actually received services. A state‐level study found that nearly half (49.4%) of the children with a treatable MH condition did not receive needed treatment or counseling from a MH professional. 2 Another study of 13 states using different criteria also found a range of MH unmet need, from a low of 51.3% in Massachusetts to a high of 80.6% in California. 15

Modest racial differences in unmet needs exist, though perhaps more might be expected in the presence of structural racism in the United States. 16 , 17 The National Health Interview Survey found unmet needs for 80% of Black, 82% of Hispanic, and 72% of white children and youths, 10 although these differences largely disappear when adjusting for family income, insurance status, and state of residence. There are large differences in the use of services by family income, with the highest level of unmet needs among children of poor families. Even though the effect of state of residence exceeds the effect of either race/ethnicity or income, the differences in need across states are relatively small, especially after adjusting for sociodemographic differences. 18 The importance of sociodemographic differences and their associated health consequences 15 has been increasingly appreciated by health care providers as they are encouraged to consider the social determinants of their patients’ health.

Socioeconomic differences in the utilization of MH services and out‐of‐pocket expenditures 19 , 20 , 21 are often related to the sources and types of health insurance. 22 , 23 In addition, the economic downturn associated with the COVID‐19 pandemic and the associated increase in the need for mental health and social services are evidence of the strong relationship between socioeconomic status and health. 24 Clearly, differences in social, economic, and environmental circumstances lead to systemic health inequities. 25

The Current System

Despite these troubling levels of prevalence and unmet need and the serious impact of MH problems on children's functioning, the United States has failed to develop a comprehensive, systematic approach to the seemingly perennial crisis in children's MH. 26 Much like the services for children with other special health care needs, the child and adolescent mental health system is fragmented, controlled by professionals, oriented to treatment rather than prevention, inconsistently available, and inefficient. 27 In addition, despite much research on evidence‐based care, the availability of that care is the exception rather than the rule.

History

The substantial need for MH services for children and adolescents and the serious shortcomings of those services has been well documented 28 , 29 , 30 and long observed. Many of the current difficulties in providing appropriate MH services arose out of the generally well‐intended, though economically and politically influenced, deinstitutionalization of the mentally ill. 31 The intent was to create community‐based MH services, but these were plagued by inadequate funding and staffing, local politics, and issues of governance. 32 Over the past 50 years, both federal and state governments have made efforts to bolster community‐based services, especially to improve children's MH services.

Although not specifically intended to address children's and youths’ mental health needs, the enactment in 1965 of Title XIX, Medicaid, provided the financing platform for much of the subsequent mental health services. It followed a government study entitled One Third of a Nation: A Report on Young Men Found Unqualified for Military Service, which reported a 50% rejection rate among young men drafted into the military in 1962. The study documented pervasive evidence of treatable physical, mental, and developmental conditions. 33 In 1967, amendments to the Medicaid law singled out the needs of children and adolescents and created a special set of benefits entitled Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment to promote children's health and development. Additional amendments in 1989 broadened coverage to ensure full coverage for all physical, mental, and developmental conditions. Consequently, state Medicaid programs have become the dominant source of payment for child and adolescent mental health services.

In 1969, the Joint Commission on the Mental Health of Children commented, “Yet, we find ourselves dismayed by the violence, frustration, and discontent among our youth and by the sheer number of emotionally, mentally, physically and socially handicapped youngsters in our midst.” The commission recommended that an integrated network of community services be developed to better meet the needs of children and youths with a serious emotional disturbance. 34

The US education system tends to be the major player in the de facto system of care for children with MH problems. 35 This role began in 1975 with the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (Public Law 94–142), now known as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). Public Law 94–142 guaranteed free and appropriate public education for each child with a disability and initiated efforts to improve how children with disabilities were identified and educated. Amendments to the law in 1997 required that each student's individualized education plan (IEP) contain various elements, among which was referring students to appropriate community agencies for necessary services. IDEA added the expectation, not yet achieved, of an adequate supply of qualified teachers and other school staff, including but not limited to special education teachers, therapists, counselors, and psychologists. 36

IDEA also requires school districts to provide “related services” to assist children with a disability to benefit from special education. These include such things as speech‐language therapy and audiology services; interpreting services; psychological services; physical and occupational therapy; recreation, including therapeutic recreation; early identification and assessment of disabilities in children; counseling services; psychological and social work services; and medical services for diagnostic or evaluation purposes. IDEA further mandates that schools be the payers of last resort for related services, including MH‐related services. The Mental Health in Schools Act of 2015 and associated laws provide federal funding to establish school‐based MH services and to train school staff in MH‐related issues and services such as recognizing symptoms of common mental illnesses/substance use disorders, deescalating crisis situations, referring students to community resources, and creating school and community MH partnerships. Clearly, public policy leans heavily on the education system for MH services and for the integration of other services.

Despite IDEA, general funding for school‐based services is limited, and resources for mental health services are not a top priority for schools. In addition, billing for individual services is an administrative process for which most schools are not equipped, and dependence on low public‐sector reimbursement rates is a further barrier to services in this location. Schools are an attractive venue for population‐based preventive mental health services; while some schools are providing such interventions, costs and staffing limit their availability.

In 1977, President Jimmy Carter created the Presidential Commission on Mental Health. A review of this commission's report highlighted the way that social, political, and structural factors all combined to shape MH policy in unanticipated ways. The commission found that the existing decentralized and uncoordinated MH system was not providing integrated and comprehensive services to those with the greatest needs. 37 Hence there was increased interest in a systems approach that would forge links between the MH system, on one hand, and other health and human services, on the other.

Likewise, the publication of the book Unclaimed Children in 1982 38 also attracted interest nationally in improving gaps in MH services for children and led to the Child and Adolescent Service System (CASS) Program, launched by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). CASS provided funds for states to begin building children's MH systems that would incorporate a wide array of services, such as individualized care, the least restrictive environments possible for service provision, coordination among child‐serving agencies and programs, cultural and linguistic competence, and the meaningful participation of families and youth. 39 In 1984, federal funds were appropriated for the Child and Adolescent Service System Program to assist states in developing an infrastructure to coordinate services across multiple health and human services agencies. Propelling these reform efforts were the values and principles embedded in what was labeled the Systems of Care, which provided a conceptual framework for organizing and delivering MH services and treatments. 40

Systems of Care is generally referred to as a philosophy, and it has become a central driver of US child mental health policy. 41 This philosophy states that (1) children's MH services should be driven by the needs and preferences of the child and family using a strengths‐based approach in the least restrictive environment; (2) the focus and management of services should be in a multiagency collaborative environment and should be coordinated; (3) the services offered and the agencies involved should be responsive to the cultural context and characteristics of the population served; and (4) families should be the lead partners in planning and implementing the system of care and which should include early identification and intervention. 42

A 1986 report from the Office of Technology Assessment identified the major players in a child and adolescent mental health system:

The educational system, the general health care system, the child welfare system, and the juvenile justice system present important opportunities to identify and help troubled children. Yet evidence suggests that the MH problems of children involved with these systems are often poorly treated or not treated at all. The variety of MH programs potentially available to children would appear to require that such services be integrated across modalities, providers, settings, and systems, although in many cases there may be few services to integrate. 43

In 1992, through Public Law 102–321, the federal government launched a second wave of reform efforts through the Comprehensive Community Mental Health Services Program for Children and Their Families legislation, referred to as the Children's Mental Health Initiative (CMHI). This legislation provided funds to create and expand community‐based MH services for both children with serious emotional disturbances and their families based on the Systems of Care philosophy.

Wraparound services are intensive care coordination or case management services based on the provision of individualized services incorporated in a family‐centered, team‐based plan that includes the entire array of services and support that the child and family require. 44 The list of potential services is substantial and, in addition to psychotherapeutic interventions, can include special education services, family support, legal services, recreational therapy, and transportation. 45 , 46 Wraparound is closely aligned with the Systems of Care philosophy and often is the primary manifestation of that philosophy in community‐based child mental health programs. 47 Most states use some form of the “wraparound approach” to provide these services. 48 This program has improved children's emotional and behavioral functions and reduced the use of inpatient and juvenile justice facilities, but it has reached only a small portion of children and youths in need of MH services. 49

Not a change in public policy but the introduction of family systems therapy as a mode of mental health treatment in the 1960s and 1970s was an important shift away from individual child therapy. 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 Over the past decade, the number of publications on the topic has demonstrated an increased interest in this approach, which has implications for the design of child and adolescent mental health systems in, for example, access, training, and payment.

In 2000, the US surgeon general held a national conference to develop specific recommendations for a National Action Agenda on Children's Mental Health to ensure that our health system responds as readily to the needs of children's mental well‐being as it does to their physical well‐being. The conference concluded that one way to achieve this was to move the country toward a community health system that balanced MH promotion, illness prevention, early detection, and universal access to care. The conference set out eight goals with numerous action steps to provide a comprehensive blueprint to achieve this. Many of the recommendations looked to the education system to play a greater role. Notable was the recommendation to provide the infrastructure for cost‐effective, cross‐system collaboration and integrated care, including support for health care providers for identification, treatment coordination, and/or referral to specialty services, as well as the development of integrated community networks to increase appropriate referral opportunities. 54 , 55 Such an infrastructure remains to be fully described and developed.

In 2002, The New Freedom Commission on Mental Health was established by executive order to conduct a comprehensive study of the US MH service delivery system and make recommendations based on its findings. 56 With regard to child MH, the commission found that the system was fragmented and in disarray, with gaps in care leading to unnecessary and costly disability, homelessness, school failure, and incarceration. 57

Since the mid‐1980s, child and adolescent health services have moved toward a community‐based Systems of Care model. The model is based on a flexible and individualized approach to service delivery for the child and family. In theory, it includes a comprehensive array of services with full utilization of the family's and the community's resources. 49 This model was originally proposed for the treatment of seriously emotionally disturbed children, 39 but following a growing appreciation of the ecological model 58 and the social determinants of health, 59 it has since been adopted as a general model for child MH care. Unfortunately, the availability of a model does not ensure its implementation.

The Mental Health Parity and Addition Equity Act was enacted in 2008. It has generally prevented group health plans and health insurers and, as amended in 2010, individual health insurance coverage from imposing less favorable benefit limitations on mental health services, when they offer such services, than on medical and surgical benefits. 60 This legislation offered great hope that by equating mental health and medical/surgical services that the systemic improvements enacted for medical care would be replicated for mental health care. Consequent to the law, utilization was not substantially changed, although access to services for children with autistic spectrum disorder increased, and individuals had lower out‐of‐pocket costs. 61 , 62 Unfortunately, the expectation of parity of benefits generally has not been fulfilled, and the two major branches of health care remained functionally divided. 63 During the past decade, however, there has been an increased call for integration of medical and behavioral health services, at least at the practice level. 64 , 65 Such integration will require structural changes in practice organizations and financing.

Throughout these several decades of efforts to improve systemic aspects of child and adolescent MH care has been an active effort to identify which approaches to assessment and treatment were effective in improving child outcomes. 67 , 68 , 69 This field of research on evidence‐based practices has been extremely productive, with much of the work supported by the National Institute of Mental Health, beginning in 1955 with the Mental Health Study Act authorizing studies of and recommendations for MH and mental illness in the United States. Most recently, the 21st Century Cures Act has emphasized the importance of evidence‐based programs at the federal level, and it created the National Mental Health and Substance Use Policy Laboratory to promote evidence‐based practices and service delivery models. The several meta‐analyses of previous research generally have found effective approaches to addressing child and adolescent MH service needs. But most often their effectiveness has not been replicated when implemented outside the research studies, owing to the lack of fidelity to procedures and complicating comorbidities, and extenuating social factors and cultural diversity, which have affected outcomes. 61 , 67 , 70 When these social determinants are not explicitly addressed in the treatment plan directing wraparound services, they may persist and continue to limit the effectiveness of evidence‐based practices. 23

Current Status

Although progress has been made in addressing children's MH, identification, assessment, and especially access to appropriate and effective treatment remain major problems in this country. Repeated recommendations to create interdisciplinary systems to reduce mental illness and to improve services have gone largely unheeded. 71 An important, though not necessarily well‐planned, result of increased awareness of problems is that many children receive MH services in non‐mental‐health systems such as education, primary care, juvenile justice, and child welfare. This pattern has led to more potential points of contact where children can be identified and treated, but it also has magnified the existing fragmentation and inadequacy of service delivery. Fragmentation and stratification of services can lead to mismatches between therapeutic needs and service availability and impede the provision of optimal care. High levels of unmet needs persist.

The early identification of child behavioral concerns is an opportunity for childcare providers to contribute to children's mental health. The education of most childcare providers and staff is weak in the basics of child development, however, with the documented expulsion of young children from childcare facilities as evidence. This is ironic, since a principal goal of these settings is to promote social and emotional development. Consequently, it is often only later, after parents become concerned, that a child's mental illness comes to professional attention in a doctor's office. Much of children's MH treatment is delivered during visits with a pediatrician or other primary care physician. 72 Yet many primary care pediatricians are reluctant to diagnose or treat mental illnesses, and referrals are limited by a lack of referral resources. Consequently, it is not entirely surprising that on the basis of a population‐based community survey, 31 70% to 80% of children who received MH services were seen in the education sector. Moreover, the education sector was the sole source of MH care for the majority of these children, despite the major shortcoming that schools tend to lack a system for early detection and prevention. 42 Similarly, the juvenile justice system tends to be the sole source of MH services for many of the seriously emotionally disturbed children it serves, 31 and the child welfare system is responsible for the hundreds of thousands of children who have been traumatized each year and are in need of therapy.

The roles of these multiple key entities—pediatrics, education, juvenile justice, social work and child welfare, psychiatry and psychology—which have responsibility for different populations of children and adolescents in different settings and circumstances—are unclear. Each does have a role, but each brings different goals, strategies, and cultures to its approach to MH services. Thus, what should be a rational, structured process of assessment and assignment of treatment responsibilities is instead a perverse manifestation of an ill‐defined, disorganized process.

Barriers

Numerous barriers prevent children from receiving timely and appropriate MH services, and gaps in the existing array of services are common. Looming large is that the eligibility criteria for MH services vary across different systems. The lack of coordination and access to quality MH care create problems in identifying and treating MH needs. Perhaps most important, the systems involved in providing MH services for children and families lack a coherent financial infrastructure to support the range of services needed, and this contributes both to a lack of available services and to difficulty accessing those that do exist. 73 Funding MH research has been falling for the past decade, 74 and smaller state budgets have led to reductions in provider reimbursement by Medicaid programs. Provider rates are known to be associated with access to care.

There is a long list of other barriers to achieving a well‐functioning system of MH services for children and adolescents. Often mentioned are a number of structural issues, such as a shortage of qualified professionals and lack of training, poor distribution of existing services, lack of awareness of available services and how to access them, poor interagency communication, disciplinary insularity, MH “carve‐outs” and restricted benefits by managed‐care plans, lack of reimbursement for care coordination, lack of services in the absence of a diagnosable condition, and confidentiality issues. Furthermore, the distinctions between the MH service needs of developing and dependent children and those of adults are sometimes overlooked. There are also “cultural” issues like the public's ambivalence about social programs, different attitudes toward mental illness and MH services among different racial and ethnic groups, social stigma, low priority for MH services within the larger health care field, and reluctance to change based on existing organizations and funding. Overriding nearly all these barriers is the growing appreciation of the social factors experienced by children and families that contribute to their emotional and behavioral disorders.

Aggravating these issues are some important gaps in current services, such as the failure to promote positive early childhood experiences, scant attention to preventive MH services, little emphasis on the early identification of both risk and early signs of MH problems, variable quality of MH services, failure to apply evidence‐based practices, inability to provide culturally competent services, and inadequate information sharing among child and family service providers. In sum, the structure of the current MH system is poorly designed to address these, problems.

The federal government, state governments, and local communities together must help create effective systems of care. But these three distinct levels of government and the multiple programs that each operates often lead to cost shifting and disagreements about assignments and assumption of responsibilities. State Medicaid programs are the largest payer of children's health services across many agencies, including school‐based health and MH services, and although they are taking greater interest in meeting MH needs, they have not been able alone to overcome the substantial structural and financial barriers to ensuring high‐quality care and achieving parity with other medical services.

Why a System of Care?

Throughout the history of studies on MH services for children, there have consistently been recommendations to create an organized, integrated system of care. Services are scattered across several disciplines and scores of public agencies, and many affected children receive services from multiple sources. Studies of various populations of children using some sort of MH services show that their service needs change not only with circumstances but also with developmental changes. Few children depend on a single system. 75 Yet each of these “systems” has its own goals, expertise, and strategies and rarely effectively plans or collaborates with the others. The result is that many services are inadequate; some are duplicative; and few children receive the care they need to gain, maintain, or regain MH.

The problem is not that children cannot be identified and appropriately served. Several decades of research has documented the beneficial effects of a broad range of interventions for children, including prevention programs to reduce the likelihood of youths’ problems and disorders and intervention programs to ameliorate problems and disorders. 67 , 76 Rather, the service system is currently unable to adequately prevent MH disorders, meet the needs of children with existing MH problems, or help promote positive MH and development. These shortcomings contribute to a variety of MH disparities and consequent social limitations of individuals and groups.

We have evidence that community‐based programs focusing on promotion and prevention in MH can be effective, with a central role identified for the education system. 77 But a comprehensive system that would meet children's many needs lacks an infrastructure. Here the term systems of care is defined as a coordinated network of interdependent, community‐based services and supports that are organized to promote the positive MH of all children and youths and to meet the challenges helping those with MH problems achieve a state of well‐being. 78

The National Institute of Mental Health has a mandate to support research to improve MH services for children, 26 and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration is charged with innovating and testing new service delivery approaches as well as helping local efforts to build an infrastructure to improve service delivery. The country seems far from achieving those goals.

An obvious but too often ignored reason for slow progress is that the majority of what are identified among children and youths as MH problems are social in origin. The social and environmental conditions under which children are raised directly impact their social and emotional development, 79 and specific adverse and traumatic childhood exposures, such as harsh parenting, parental drug and alcohol use, exposure to violence, experiencing racism, and living in poor communities, are risk factors for the development of MH problems. 80 Thus, while effective MH services need to identify and address the social factors impeding the optimal and positive MH of individuals, public policy must address the larger presence and impact of social determinants that affect health and well‐being. This will require financial support sufficient to ensure families’ economic security.

Desirable Characteristics of a System of Care

In a field as complex as children's MH, developing effective solutions requires a functioning interorganizational network and coordinated efforts within and across multiple disciplines. 81 A public health framework has been recommended to reconceptualize MH services. This framework would require a partnership among a wide variety of stakeholders to address mental illness and promote MH. 82 It would incorporate a strengths‐based approach and feature the promotion of MH, the prevention of mental illness, the treatment of existing emotional and behavioral disorders, and an understanding of the personal and social factors that contribute to each. All this is part of the Systems of Care philosophy. In addition, it expects a comprehensive array of treatments, services, and supports and the use of evidence‐based interventions when available. Achieving children's MH will require building a system beyond what currently exists. 24

Envisioning and building an efficient and organized human services system with sufficient resources is a requisite first step toward providing appropriate interventions. Building this system will require the collaboration and partnership of an array of individuals, groups, agencies, and professions. 83 One need only look to the recommendations of The Surgeon General's Conference on Children's Mental Health for specific guidance on the goals and content of a such system of children's MH services. 35

Awareness that children's physical and MH is often a direct reflection of their experiences in their home environments and communities is growing. 84 Yet too often treatment focuses on the individual child rather than the family unit and its circumstances. 85 This tendency is aggravated by an insurance system that provides coverage to individuals without adequate allowance for family‐oriented care and by a health care system that segregates patients by age. Developing an appropriate child and adolescent MH system will require integrating care for parents as well. 86 , 87

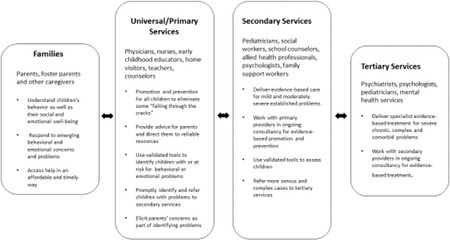

Figure 1 is derived from an Australian model of an integrated approach to MH services, showing how service responsibilities can be divided as well as shared and emphasizing a dynamic relationship among stakeholders at all levels of service. 74

Figure 1.

Dividing and Sharing Responsibilities for Mental Health Services in Communities74

Process and Rationale for System Design and Standards

There seems to be national consensus on the philosophy, values, and principles essential to create a high‐quality child MH system, which provides a valuable conceptual starting point for system redesign and development. But there is much less agreement on the actual form of this system and how responsibility for its implementation, financing, operation, performance, and governance would be assigned. To resolve these complex, interrelated issues will require time, planning, transformative leadership, and collaboration on many levels, 32 and their resolution will be strongly influenced by local resources, beliefs, values, funding streams and similar variables.

The first step is agreeing on the essential structures and processes of a metasystem. These differ from what others have meant by the activities necessary to create a system. 74 Here “structure” is used much more simply; it is the pieces that make up a system. Although it has been tempting to jump to considering how a child and adolescent MH system should operate and how the pieces would fit together, that step depends on agreeing first on what those pieces are. Achieving consensus on the pieces of a system is possible, as it has been done to improve the health care systems responsible for serving children with chronic and complex physical health problems. 88 That work began by reviewing existing recommendations and standards based on research and expert opinions. With some modifications, this process could be replicated to build a better system to address children's MH needs. A first step might be to identify and reach consensus on the key domains of a children's MH care system. Table 1 is proposed as a start to that process. It lists possible domains, and the online appendix is provided as a starting point for developing the next level of their contents. These domains are presented as something to be responded to and modified by experts in child and adolescent MH, but many already have been considered by leaders in child MH. 89 The selection of domains is based on previous work on system standards. Using a PubMed search on “mental health services” limited to children and adolescents, these categories capture 81% of articles in that database.

Table 1.

Draft Domains of a Mental Health System for Children and Adolescents

| 1. Eligibility |

| 2. Accessibility |

| 3. Standardized Screening and Assessment |

| 4. Continuum of Care Services, Settings, and Providers |

| 5. System Integration |

| 6. Comprehensive Financing and Funding |

| 7. Public Awareness and Advocacy |

| 8. Family Engagement and Support |

| 9. Quality Assurance |

| 10. Technology |

There is some rationale for the many suggested domains:

Eligibility. In the past, priority has been given to serving children and youths with serious emotional disturbances, even though these disturbances make up only a fraction of those needing MH services. Too often, eligibility for services depends on the site or agency with which the child is associated. Because MH is a universal goal, children should be universally eligible for services.

Accessibility. Because of the pronounced disparities in access to MH services, reflecting racial, ethnic, and geographic differences in populations, the structure of an equitable system must address these differences in accessibility. Expanded use of telehealth is one strategy to be applied.

Standardized Assessment. The variability of MH services among agencies and disciplines begs for standardization in screening and assessment. A part of such standardization is agreement on the periodicity of screening and the use of validated instruments and assessment procedures.

Continuum of Care. Because the range of needs for MH services is extensive, the variety of available services modalities should be, too. Needs change as MH improves or declines, as well as when children develop. The various approaches to serving children need to be codified, and the transitions between them need to be anticipated as part of the structure of the system. Of special importance is ensuring that among the pieces comprising the system are sufficient resources directed toward preventing mental illness and promoting MH. In addition, a redesigned system needs to include structures that maximize the adoption and successful adaptation of evidence‐based practices.

Service Integration. Besides the plethora of therapeutic interventions, there are multiple disciplines, agencies, and organizations providing these services, often to the same children and families. Ideally, these system components would be rationally integrated to eliminate fragmentation of care and duplication of services. More realistically, yet still challenging, is designing a system in which the pieces are created and organized to provide clarity as to who is responsible for what. An additional challenge is to design a system with “no wrong door,” meaning that children and youth in need of services will be able to obtain those services, through appropriate assessment and referral, regardless of how they enter the MH system.

Financing. In addition to interdisciplinary fragmentation and competition around children's MH services, perhaps at its core, is dependence on multiple, unrelated funding streams, both public and private. While the health care system is experimenting with alternative payment models, it has not sufficiently considered those services provided by other systems, such as education and juvenile justice. In part because of the lack of integrated funding, different levels of provider reimbursement exist in different systems as well as in different settings. Ironically, despite its potential to reduce long‐term costs, funding for prevention and early intervention services is globally insufficient.

Public Awareness. For a variety of reasons, child and adolescent MH services have been assigned relatively low priority in the United States. Creating an effective system will require greater public awareness and advocacy. Much of this will rest on increasing the availability of reliable data on the prevalence of poor MH and its personal, social, and economic consequences. Similarly, data on the impact of good MH and thriving should be available.

Family Engagement. Nearly all the literature on child and adolescent MH services mentions, and generally emphasizes, family involvement and support. The majority of children's MH service needs result from or are influenced by their family and the social circumstances of their families. The system needs to be redesigned to adequately address family functioning, which will require different insurance benefits, reimbursement strategies, and staffing patterns. It will also require active engagement with families in planning and implementing treatment for their children. Perhaps of greatest importance, the redesign of the child and adolescent mental health system needs to be guided by the voice and experience of youth and families. 90

Quality Assurance. The long‐standing concern about the quality of MH services, including embedding evidence‐based practices in community‐based care, must be addressed as part of the system redesign. The system must have the capacity, through training, licensure, and monitoring, to ensure that providers’ competence is aligned with their assigned roles. In addition, as noted previously, we need clarity and agreement on the capacities and competencies, and thus the types of services, available at various sites of care, whether hospitals, offices, schools, foster homes, or others. Each setting should be capable of providing excellent care for the children and conditions for which they are responsible.

Technology. Advances in information technology offer new opportunities to improve access, care standardization, quality monitoring, outreach and follow‐up, family engagement, interdisciplinary communication, and service coordination. These technologies should be expected, visible components of a child and adolescent MH system.

Conclusions

The MH field cannot be held entirely responsible for the prevalence of emotional disorders among children and adolescents, except for its failure to commit fully to efforts to prevent adverse life experiences affecting their life course and to advocating for social policies to promote healthy social and emotional development. The MH field can be held accountable for failing to meet the needs for effective interventions in the presence of emotional distress and dysfunction. In this article, I have suggested an approach to addressing the latter failing by ensuring that the MH services delivery system can provide those services for which there is evidence of efficacy.

This work could begin by convening a national consensus work group of key stakeholder groups with meaningful youth and family leadership. The project could be managed by a nonpartisan, nonprofit organization or perhaps by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. It is important that the process is inclusive of all sectors involved with child and adolescent MH, such as education, public health, juvenile justice, child welfare, and social services, so that the possibility of moving toward system integration is addressed from the outset. Agreeing on and creating a structure able to support and provide essential services is a measurable first step. It is necessary but not sufficient. Having a structurally sound system does not in itself guarantee high‐quality care processes, but it does make them possible. A thoughtfully designed, comprehensive system that reflects the interdependence of its parts will facilitate the coordination and shared accountability of the many disciplines, agencies, institutions, and professionals that comprise that MH system on whom children and their families depend.

Funding/Support: None.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr. Schor completed the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. No conflicts were reported.

Supporting information

Draft Domains and Potential Content for Planning a Mental Health System for Children and Adolescents

References

- 1. World Health Organization . (2007). Mental health: strengthening mental health promotion. Fact sheet 220. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2007. https://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs220/en/. Accessed May 23, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Whitney DG, Peterson MD. US national and state‐level prevalence of mental health disorders and disparities of mental health care use in children. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(4):389‐391. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.5399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mojtbai R, Olfson M. National trends in mental health care for US adolescents. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020:77(7):703‐714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brauner CB, Stephens CB. Estimating the prevalence of early childhood serious emotional/behavioral disorders: challenges and recommendations. Public Health Rep. 2006;121:303‐310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Merikangeas, KR , Nakamura E, Kessler RC. Epidemiology of mental disorders in children and adolescents. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2009;11:7‐20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ruch DA, Sheftall AH, Schlagbaum P, etc. Trends in suicide among youth aged 10 to 19 years in the United States, 1975–2016. JAMA Network Open. 2(5):e193886. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.3886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Trauma. Washington, DC: SAMHSA‐HRSA Center for Integrated Health Solutions. https://www.integration.samhsa.gov/clinical-practice/trauma-informed. Accessed May 23, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Torio CM, Encinosa W, Berdahl T, McCormick MC, Simpson LA. Annual report on health care for children and youth in the United States: national estimates of cost, utilization and expenditures for children with mental health conditions. Acad Pediatr. 2015;15:19‐35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. National Research Council and Institute of Medicine . Preventing Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Disorders Among Young People: Progress and Possibilities. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2009:241. 10.17226/12480. Accessed May 23, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jensen PS, Goldman E, Offord D, et al. Overlooked and underserved: “action signs” for identifying children with unmet mental health needs. Pediatrics. 2011;128:970‐979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kataoka SH, Zhang L, Wells KB. Unmet need for mental health care among U.S. children: variation by ethnicity and insurance status. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1548‐1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ghandour RM, Sherman LJ, Vladutiu CJ, et al. Prevalence and treatment of depression, anxiety, and conduct problems in US children. J Pediatr. 2019;206:256‐267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang PS, Sherrill J, Vitiello B. Unmet need for services and interventions among adolescents with mental disorders. Am J Psychiatry, Psychiatry Online . January 2007. https://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/ajp.2007.164.1.1. Accessed May 23, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14. Ford T. Practitioner review: how can epidemiology help us plan and deliver effective child and adolescent MH services? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008:49:900‐914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sturm R, Ringel JS, Andreyeva T. Geographic disparities in children's mental health care. Pediatrics. 2003;112:e308‐e315. http://www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/112/4/e308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bailey AD, Krieger N, Agenor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. America: structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389:1453‐1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Priest N, Perry R, Ferdinand A, Paradies Y, Kelaher M. Experiences of racism, racial/ethnic attitudes, motivated fairness and mental health outcomes among primary and secondary students. J Youth Adolesc. 2014;43:1672‐1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Beck AF, Tshudy MM, Coker TR, et al. Determinants of health and pediatric primary care practices. Pediatrics. 2016;137:e20153673. 10.1542/peds.2015-3673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lê Cook B, Trink N‐H, Zhihui L, Hou SS‐Y, Progovac AM. Trends in racial‐ethnic disparities in access to mental health care, 2004–2012. Psychiatr Serv. 2017;68(1):9‐16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Locke J, Kang‐Yi CD, Pellecchia M, Marcus S, Hadley T, Mandell DS. Ethnic disparities in school‐based behavioral health service use for children with psychiatric disorders. J School Health. 2017;87(1):47‐54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Marrast L, Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S. Racial and ethnic disparities in mental health care for children and young adults: a national study. Int J Health Serv. 2016;46(4):810‐824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Walker HM, Nishioka VM, Zeller R, et al. Causal factors and potential solutions for the persistent under‐identification of students having emotional or behavioral disorders in the context of schooling. Assess Effective Intervention. 2000;26:29‐39. 10.1177/073724770002600105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bettenhausen JL, Richardson TE, Shah SS, et al. Medicaid expenditures among children with noncomplex chronic diseases. Pediatrics. 2018;142(5):e20180286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Krist AH, Davidson KW, Nego‐Metzger Q, Mills J. Social determinants as a preventive service: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force methods considerations for research. Am J Prev Med. 2019;12;57(6 Suppl. 1):S6‐S12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Whitehead M, Dahlgren G. Concepts and Principles for Tackling Social Inequities in Health: Levelling Up . Part 1. Copenhagen, Denmark: World Health Organization; 2006. https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/74737/E89383.pdf?ua=1. Accessed August 22, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Huang L, Stroul B, Friedman R, et al. Transforming mental health care for children and their families. Am Psychol. 2005;60:615‐627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. American Psychological Association , Task Force on Evidence‐Based Practice for Children and Adolescents. Disseminating evidence‐based practice for children and adolescents: a systems approach to enhancing care. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2008. https://www.apa.org/practice/resources/evidence/children-report.pdf. Accessed July 7, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Stagman S, Cooper JL. Children's mental health: What every policymaker should know. New York, NY: Columbia University, National Center for Children in Poverty; 2010. http://www.nccp.org/publications/pub_929.html. Accessed May 23, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Weisz JR, Han SS, Valeri SM. More of what? Issues raised by the Fort Bragg study. Am Psychol. 1997;52(5):541‐545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bickman L, Noser K, Summerfelt WT. Long‐term effects of a system of care for children and adolescents. J Behav Health Serv Res. 1999;26(2):185‐202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rochefort DA. Origins of the “Third Psychiatric Revolution”: The Community Mental Health Centers Act of 1963. J Health Polit Policy Law. 1984;9(1):1‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mechanic D, Rochefort DA. Deinstitutionalization: an appraisal of reform. Ann Rev Sociol. 1990;16:301‐327. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rosenbaum S, Mauery DR, Shin P, Hidalgo J. National security and U.S. child health policy: the origins and continuing role of Medicaid and EPSDT. Washington, DC: George Washington University, School of Public Health and Health Services, Department of Health Policy; 2005. https://hsrc.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1033&context=sphhs_policy_briefs. Accessed July 7, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Joint Commission on Mental Health of Children . Crisis in child MH: challenge for the 1970's. Final report. Washington, DC: Joint Commission on Mental Health of Children; 1969. https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/ext/document/101743403X98/PDF/101743403X98.pdf. Accessed May 23, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Burns BJ, Costello EJ, Angold A, et al. Children's mental health service use across service sectors. Health Aff. Data Watch. 1995;14:147‐159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. US Department of Education Office of Special Education Programs . History: twenty‐five years of progress in educating children with disabilities through IDEA. Washington, DC: US Department of Education Office of Special Education; 2005. https://www2.ed.gov/policy/speced/leg/idea/history.pdf. Accessed May 23, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Grob GN. Public policy and mental illnesses: Jimmy Carter's Presidential Commission on Mental Health. Milbank Q. 2005;83:425‐456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Knitzer J. Unclaimed Children: The Failure of Public Responsibility to Children and Adolescents in Need of Mental Health Services. Washington, DC: Children's Defense Fund; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Stroul BA, Blau GM, Sondheimer DL. Systems of care: a strategy to transform children's mental health care. In: Stroul BA, Blau GM, eds. The System of Care Handbook: Transforming Mental Health Services for Children, Youth, and Families. Baltimore, MD: Paul H Brookes; 2008:3‐23. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Stroul BA, Friedman RM. A system of care for severely emotionally disturbed children and youth. Washington, DC: Georgetown University, Child Development Center, CASSP Technical Assistance Center; June 1986. https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/Digitization/125081NCJRS.pdf. Accessed May 23, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hodges S, Ferreira K, Israel N, Mazza J. Systems of care, featherless bipeds, and the measure of all things. Eval Program Plann. 2010;33(1):4‐10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Stroul B, Blau G, Friedman R. Updating the system of care concept and philosophy. Washington, DC: Georgetown University, Center for Child and Human Development, National Technical Assistance Center for Children's Mental Health; 2010. https://gucchdtacenter.georgetown.edu/resources/Call%20Docs/2010Calls/SOC_Brief2010.pdf. Accessed May 23, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 43. US Congress, Office of Technology Assessment . Children's mental health: problems and services—a background paper. OTA‐BP‐H‐33. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1986. http://www.princeton.edu/~ota/disk2/1986/8603_n.html. Accessed May 23, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Walker JS, Bruns EJ, Penn M. Individualized services in systems of care: the wraparound process. In: Stroul BA, Blau GM, eds. The System of Care Handbook: Transforming Mental Health Services for Children, Youth, and Families. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes; 2008:127‐153. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rural Services Integration Toolkit . Module 2: evidence‐based and promising models. Wraparound. https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/toolkits/services-integration/2/care-coordination/wraparound. Accessed July 7, 2020.

- 46. Schor EL. An almost complete list of services used by families and children with special health care needs. Palo Alto, CA; Lucile Packard Foundation for Children's Health; 2019. https://www.lpfch.org/publication/almost-complete-list-services-used-families-and-children-special-health-care-needs. Accessed July 7, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Coldiron JS, Bruns EJ, Quick H. A comprehensive review of wraparound care coordination research, 1986–2014. J Child Fam Stud. 2017;26:1245‐1265. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Malysiak, R. Exploring the theory and paradigm base for wraparound. J Child Fam Stud. 1997;6:399‐408. [Google Scholar]

- 49. US Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . The Comprehensive Community Mental Health Services for Children with Serious Emotional Disturbances program, report to Congress 2017. Washington, DC; 2017. https://store.samhsa.gov/product/The-Comprehensive-Community-Mental-Health-Services-for-Children-with-Serious-Emotional-Disturbances-Program-2017-Report-to-Congress/PEP20-01-02-001. Accessed May 23, 2020.

- 50. Minuchin S, Montalvo B, Guerney, Jr BG , Rosman BL, Schumer F. Families of the Slums. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Haley J. We became family therapists. In: Ferber A, Mendelsohn M, Napier A, eds. The Book of Family Therapy. New York, NY: Science House; 1972:1113‐1122. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Malone CA. Observations on the role of family therapy in child psychiatry training. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1974;13(3):437‐458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Huffman L. Foundations of Family Therapy: A Conceptual Framework for Systems Change. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 54. US Public Health Service , Office of the Surgeon General. Mental health: a report of the surgeon general. Rockville, MD: US Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General; 1999. https://www.webharvest.gov/peth04/20041015005717/http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/mentalhealth/home.html. Accessed May 23, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Olin SS, Hoagwood K. The surgeon general's national action agenda on children's mental health. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2002;4:101‐107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hogan MF. New Freedom Commission Report: the president's New Freedom Commission: recommendations to transform mental health care in America. Psychiatric Serv. Published online, November 1, 2003. 10.1176/appi.ps.54.11.1467. https://ps.psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/appi.ps.54.11.1467. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57. Pumariega AJ, Winters NC, Huffine C. The evolution of systems of care for children's mental health: forty years of community child and adolescent psychiatry. Community Ment Health J. 2003;39:399‐425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Bronfenbrenner U. Developmental research, public policy, and the ecology of childhood. Child Dev. 1974;45: 1‐5. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Marmot MG. Understanding social inequalities in health. Perspect Biol Med. 2003;46:S9‐23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services . The Mental Health Parity and Addition Equity Act (MHPAEA). Rockville, MD: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Programs-and-Initiatives/Other-Insurance-Protections/mhpaea_factsheet#Fact_Sheets_and_FAQs. Accessed May 23, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ettner SL, Harwood JM, Thalmayer A, et al. The Mental Health Parity and Addition Equity Act evaluation study: impact on specialty behavioral health utilization and expenditures among “care‐out” enrollees. J Health Econ. 2016; 50:131‐143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kennedy‐Hendricks A, Epstein AJ, Stuart EA, et al. Federal parity and spending for mental illness. Pediatrics. 2018;142(2):e20172618. 10.1542/peds.2017-2618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. McGuire TG. Achieving mental health parity might require changes in payments and competition. Health Aff. 2016;35(6):1029‐1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kolko DJ, Perrin E. The integration of behavioral health interventions in children's health care: services, science, and suggestions. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2014;43(2):216‐228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ader J, Stille CJ, Keller D, Miller BF, Barr MS, Perrin JM. The medical home and integrated behavioral health: advancing the policy agenda. Pediatrics. 2015;135(5):909‐917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Asarnow JR, Rozenman M, Wiblin J, Zeltzer L. Integrated medical‐behavioral care compared with usual primary care for child and adolescent behavioral health: a meta‐analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(10):929‐937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Hoagwood K, Burns BJ, Kiser L, Ringelsen H, Schoenwald SK. Evidence‐based practice in child and adolescent mental health services. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(9):1179‐1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Kazak AE, Hoagwood K, Weisz JR, et al. A meta‐systems approach to evidence‐based practice for children and adolescents. Am Psychol. 2010;65(2):85‐97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Garland AF, Haine‐Schlagel R, Brookman‐Frazee L, Baker‐Ericzen M, Trask E, Fawley‐King K. Improving community‐based mental health care for children: translating knowledge into action. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2013;40(1):6‐22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Angold A, Costello EJ, Erkanli A. Comorbidity. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1999;40(1):57‐87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Hoagwood KE, Kelleher KJ. A Marshall Plan for children's mental health after COVID‐19. Psychiatr Serv. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Sturm R, Ringel JS, Bao Y, et al. Mental health care for youth: Who gets it? How much does it cost? Who pays? Where does the money go? Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2001. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RB4541.html. Accessed May 23, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 73. Greenbaum PE, Dedrick RF, Friedman RM, et al. National Adolescent and Child Treatment Study (NACTS): outcomes for children with serious emotional and behavioral disturbance. J Emotional Behav Disorders. 1996;4:130‐146. [Google Scholar]

- 74. Hoagwood KE, Atkins M, Kellher K, et al. Trends in children's mental health services research funding by the National Institute of Mental Health from 2005 to 2015: a 42% reduction. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2018;57(1):10‐13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Kazak AE, Hoagwood K, Weisz JR, et al. A meta‐system approach to evidence‐based practice for children and adolescents. Am Psychol. 2010;65: 85‐97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Greenberg MT, Domitrovich C, Bumbarger B. Preventing mental disorders in school‐age children: A review of the effectiveness of prevention programs. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University, Prevention Research Centre for the Promotion of Human Development; 2000. https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/49081141/mentaldisordersfullreport.pdf?1474709890=&response-content-disposition=inline/3B/filename/3DPreventing_mental_disorders_in_school-ag.pdf&Expires=1594084414&Signature=NbeMHa7~27xBFNTHn1YYFIvt2IlYwbS-p6IrHVug9AI0orOe1kmdvR1ojFz7ldOeypiCiT375iHW5hnDwB-gu8NSQ1VoAY-YIdbt0nvxkSuuIwU366YwPQW-NP-kEuFmCyiek-iEJslIWsD58F3bTSlU6ALTcqRCD7h7HsD9q2FCvQP7U9g90yxtBu-h5jqPX1r5uoOh6p-a3eM3qInRD1GfEJCHwiWFnmhgDFhQ2lbbiQRa-yp0iQLWfkPNbJntHqn2Ta7z2WEQF0ZLrqyTWv5WloDHm9KeCfBNEugYG1t-R6Elo27EhZjlbQFIq2DcjnSz7ZbWJ2kzfLtNvT7D9g__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAJLOHF5GGSLRBV4ZA. Accessed May 23, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 77. Moore TG, Arefadib N, Deery A, West S. The first thousand days: an evidence paper. Parkville, Victoria, Australia: Centre for Community Child Health, Murdoch Children's Research Institute; 2017. https://blogs.rch.org.au/ccch/2017/09/25/the-first-thousand-days/. Accessed May 23, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 78. Pires SA. Building systems of care: a primer. Washington, DC: Georgetown University, Child and Human Development Center, National Technical Assistance Center for Children's Mental Health; 2002. https://gucchd.georgetown.edu/products/PRIMER_CompleteBook.pdf. Accessed May 23, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 79. Centre for Community Child Health . Child mental health: a time for innovation, policy brief number 29. Parkville, Victoria, Australia: Royal Children's Hospital, Murdoch Children's Research Institute; 2018. 10.25374/MCRI.6263990. Accessed May 23, 2020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80. National Institute of Mental Health, National Advisory Mental Health Council, Workgroup on Child and Adolescent Mental Health Intervention Development and Deployment. Blueprint for change: research on child and adolescent mental health. Washington, DC: National Institute of Mental Health; 2001. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/advisory-boards-and-groups/namhc/reports/blueprint-for-change-research-on-child-and-adolescent-mental-health.shtml. Accessed May 23, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 81. Miles J, Espiritu RC, Horen NM, Sebian J, Waetzig E. A public health approach to children's mental health: a conceptual framework. Washington, DC: Georgetown University, Center for Child and Human Development; 2010. https://gucchd.georgetown.edu/products/PublicHealthApproach.pdf. Accessed May 23, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 82. Anderson JA, McIntyre JS, Rotto KI, Robertson DC. Developing and maintaining collaboration in systems of care for children and youths with emotional and behavioral disabilities and their families. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2002;72:514‐525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Pires SA. Building systems of care: Critical processes and structures. In: Stroul BA, Blau GM, eds. The System of Care Handbook: Transforming Mental Health Services for Children, Youth, and Families. Baltimore, MD: Paul H Brookes; 2008:97‐126. [Google Scholar]

- 84. Braverman P, Barclay C. Health disparities beginning in childhood: A life‐course perspective. Pediatrics. 2009;124:S163‐S175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Schor E. Family pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2003;111(6), part 2:1539‐1587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Carr A. Family therapy and systemic interventions for child‐focused problems. The current evidence base. J Fam Ther. 2019;41:153‐213. 10.1111/1467/6427.12226. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Biel MG, Tang MH, Zuckerman B. Pediatric mental health care must be family mental health care. JAMA Pediatr, Published online, April 6, 2020. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.0065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Association of Maternal and Child Health Programs (AMCHP) . Developing structure and process standards for systems of care serving children and youth with special health care needs. Washington, DC: Association of Maternal and Child Health Programs; 2014. https://www.lpfch.org/sites/default/files/field/publications/developing_structure_and_process__white_paper_and_standards.pdf. Accessed May 23, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 89. Hoagwood K, Kelleher K, Hogan M. Redesigning federal health insurance policies to promote children's mental health. Philadelphia, PA: Scattergood Foundation; 2018. https://www.ideas4kidsmentalhealth.org/uploads/7/8/5/3/7853050/publication_redesigning-federal-health-insurance-policies-to-promote-childrens-mental-health.pdf. Accessed July 7, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 90. Kilmer RP, Cook JR, Munsell EP. Moving from principles to practice: recommended policy changes to promote family‐centered care. Am J Community Psychol. 2010;46:332‐341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Draft Domains and Potential Content for Planning a Mental Health System for Children and Adolescents