SUMMARY:

3D printing is a new manufacturing technology that produces high-fidelity models of complex structures from 3D computer-aided design data. Radiology has been particularly quick to embrace the new technology because of the wide access to 3D datasets. Models have been used extensively to assist orthopedic, neurosurgical, and maxillofacial surgical planning. In this report, we describe methods used for 3D printing of the fetal brain by using data from in utero MR imaging.

The data used to produce the 3D printed fetal brain models were acquired by using a 3D in utero MR imaging volume acquisition. This was achieved by imaging the fetal brain by using an ultrafast, fully balanced steady-state sequence on a 1.5T whole-body MR imaging scanner as detailed in the Table.

Imaging sequence parameters for the 3D FIESTA acquisition

| 3D FIESTA Steady-State Balanced Gradient-Echo | |

|---|---|

| TR (ms) | 4.2 |

| TE (ms) | 2.1 |

| Flip angle | 60° |

| Bandwidth (Hz) | 125 |

| NEX | 0.75 |

| Section thickness/gap (mm) | 2.2/0 |

| No. of partitions | 26 |

| FOV (mm) | 340 × 270 |

| Matrix size | 320/256 |

| Interpolation phase/secondary phase | ZIP 512/ ZIP 2 |

| Scan time (sec) | 21 |

Note:—ZIP indicates interpolation values.

3D volume imaging has an inherently higher signal-to-noise ratio compared with 2D imaging because the whole-brain volume is excited at each repetition rather than section. In addition, the homogeneous excitation across the imaging volume results in more uniform section profiles compared with 2D imaging because partial saturation of signal between sections does not occur. These characteristics enable a smaller partition thickness and FOV to improve anatomic resolution, and the contiguous thin partitions permit postprocessing reconstruction for visualization of the anatomy in different planes. The contrast mechanism of steady-state imaging and flip angle determines the signal intensity from fluids, providing good tissue contrast between the fluid and brain interfaces, which assists in the creation of surface projections. We currently use a flip angle of 60°–70° because higher flip angles are associated with greater aliasing artifacts.1 Scan time is kept short by optimizing the bandwidth (to permit shorter TRs and TEs) and by partial Fourier techniques. These features allow acquisition during maternal suspended respiration leading to reduced movement artifacts.

Postacquisition Image Processing

The images from the 3D dataset are transferred onto a desktop PC and loaded into a free open-source software package, 3D Slicer (http://www.slicer.org), for segmentation.2 Once loaded into 3D Slicer, the brightness and contrast are user-selected to optimize visualization of the CSF/brain interfaces (both external and ventricular). Each brain is manually segmented on a section-by-section basis in the plane used for acquisition (usually axial), with other anatomic planes and fetal brain atlases used for cross-reference to improve accuracy.3,4 Manual outlining of the fetal brain anatomy takes approximately 50–60 minutes for second-trimester brains and 90–120 minutes for more mature fetuses; the longer time is due to the increased complexity of sulcation/gyration.

3D Slicer identifies anatomic areas by using labels, each represented by an index value and associated color. Once all the ROIs have been annotated, the software reconstructs electronic 3D surface models of the fetal brain by using the resultant labels. The surface model data are then saved in the correct file format (STereoLithography or .stl) required for 3D printing. The STereoLithography file cannot be edited, and the resultant 3D printed model is an exact representation of the generated 3D surface model; therefore, the latter should be examined for any extraneous parts to ensure that the contours are in keeping with anatomic detail. Laplacian smoothing can be applied at the model-building stage to smooth contours if necessary.

3D Printing Technique

“3D printing” is the collective term for a number of technologies that create parts in a layer-by-layer manner directly from 3D computer-aided design data without the need for tooling. The major benefits of 3D printing stem from the ability to produce complex geometries efficiently and effectively. Most 3D printing systems use data in the STereoLithography format, whereby the 3D object is reproduced as a triangulated surface.

The laser sintering process was chosen for models of the fetal brain described in this article. This is a powder bed fusion process, whereby a layer of powder is deposited and selectively scanned by a CO2 laser. Areas scanned by the laser melt and, on re-solidification, form the layers of the part. Laser sintering can produce parts from a range of materials, including metals and ceramics. In our examples, polymer material Nylon-12 (http://www.eos.info/material-p) was used to construct the models of the fetal brain. Specifically, the models were produced by using PA 2200 material on a Formiga P100 laser sintering system (EOS, Munich, Germany).

While high strength is not a key requirement for production of most models, they must be strong enough to endure handling by potentially large numbers of users. Parts produced via laser sintering generally have relatively high mechanical strength compared with other 3D printing processes, again making this a suitable process. While it is possible to build the model in 2 separate materials, most 3D printing processes only allow the production of parts in a single color. However, a number of processes allow the production of multiple colors and/or materials within a single part as demonstrated later.

Additionally, the lack of a requirement for tooling allows the production of small volumes (including production of single units) at no cost penalty. This can provide major advantages in personalization for medical use, whereby every individual may have different geometric or functional needs from a similar part. The ability to produce one-off models economically makes 3D printing highly suitable for the production of training models and demonstrators as discussed in this article. More comprehensive discussions of methods for and applications of 3D printing within the medical sector can be found elsewhere.5,6

Application of 3D Models of the Fetal Brain

One of the major applications we envisage for this technology is trying to improve anatomic understanding and training of radiologists to develop their skills in fetal neuroimaging. We have created a fetal brain teaching file available for review, which consists of a number of cases with sample reports and background of the condition, with images from both the 2D studies and 3D printed models produced via laser sintering. The abnormal brain models consist of several of the more common brain malformations at various gestational ages along with age-matched controls (Figs 1 and 2). It is also possible to transpose 2D images from in utero MR imaging studies onto 3D models to enhance the understanding of fetal anatomy further. The 3D volume images can be manipulated into the same plane as the 2D images, and those images are copied onto clear plastic with adhesive on 1 side to produce “transfers.” The STereoLithography file of the matched sections from the 3D printed model can be exported to produce a limited print of the model to produce discrete 3D printed sections of the fetal brain as shown in Fig 3. A further possibility is the production of models from multiple materials. For example in the case of the fetal brain models, it can be useful for showing clear differentiation of the ventricular system compared with the remainder of the brain parenchyma as shown in Fig 4. This is a 2-color part produced on an Objet Connex 500 Multi-Material 3D Printing system (https://www.mcad.com/3d-printing/objet-connex-printers/connex-500/).

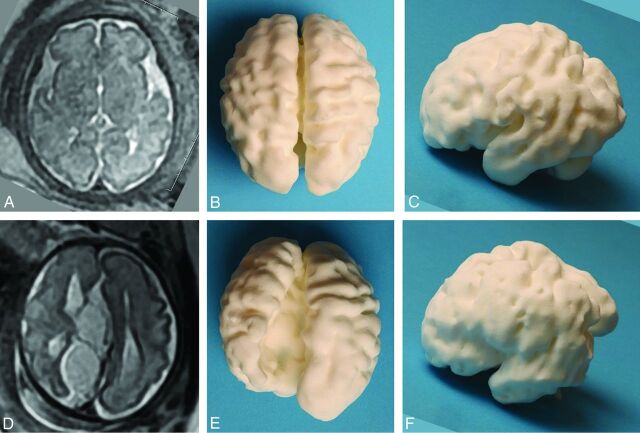

Fig 1.

Images of the 3D printed model produced via laser sintering from an in utero MR imaging study performed at 30 weeks' gestational age in a fetus with ventriculomegaly and an interhemispheric cyst recognized on ultrasonography, compared with an age-matched fetus with no brain abnormality. A 2D single-shot fast spin-echo image in the axial plane of the normal brain is shown (A), along with superior (B) and left lateral (C) views of the 3D printed model. D–F, The matching images from the fetus with agenesis of the corpus callosum and extra-axial cysts, which do not communicate with the ventricular system (type II cysts of Barkovich et al),7 are shown. Note that the orientation of the 2D image has been altered to match the 3D model for ease of interpretation. The left hemisphere contains widespread heterotopia, a feature that was confirmed at postmortem examination.

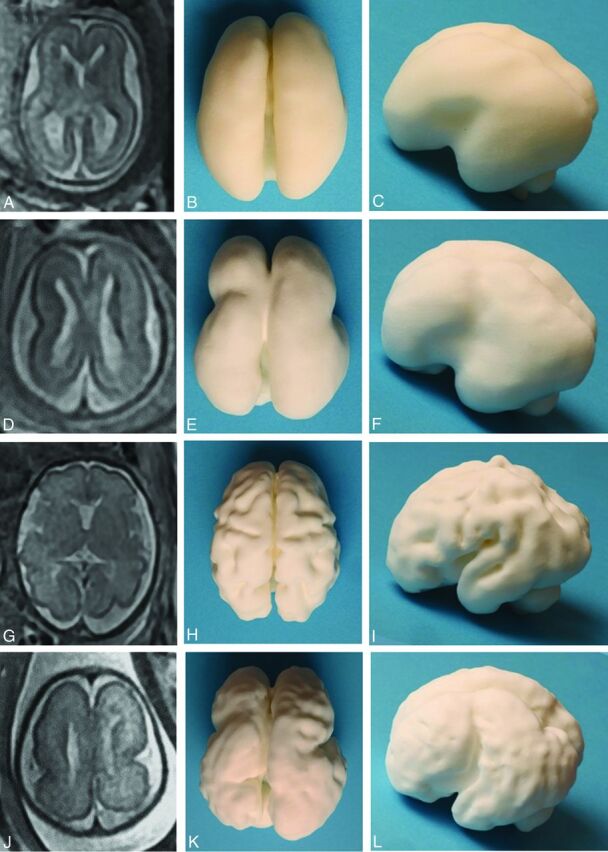

Fig 2.

Images of the 3D printed models produced via laser sintering from 2 in utero MR imaging studies performed at 2 gestational ages in a fetus with lissencephaly compared with an age-matched fetus with no brain abnormality. A 2D single-shot fast spin-echo image in the axial plane of the normal brain at 22 weeks' gestation is shown (A), along with superior (B) and left lateral (C) views of the 3D printed model. The same format is shown for a healthy 30-week fetus (D–F) and the fetus with lissencephaly (G–L).

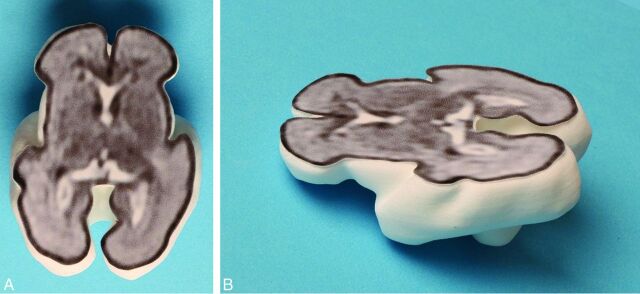

Fig 3.

A 3D printed model produced via laser sintering with the internal anatomy of the brain shown from an attached 2D single-shot fast spin-echo image to produce a section of the fetal brain—superior (A) and oblique (B) projections.

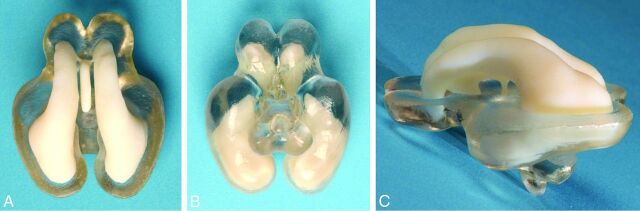

Fig 4.

Dual-material 3D printed brain produced on an Objet Connex 500 jetting system (manufactured courtesy of Professor Richard Bibb, Loughborough Design School, Loughborough, UK). Separate STereoLithography files were exported from 3D Slicer, one consisting of the segmented entire ventricular system and the other of part of the brain parenchyma. The ventricular system is printed in the same white material as the other brains, while the parenchyma is printed in a clear material. The superior (A), inferior (B), and left lateral (C) views show the relationship between the ventricles and brain to advantage.

In summary, we have outlined a method that can be used to produce 3D printed models and have described our approach to constructing 3D models of the fetal brain. The field is developing rapidly and presents a wide range of therapeutic and teaching opportunities for medicine and radiology in particular.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Paul D. Griffiths—UNRELATED: Grants/Grants Pending: research agreements with GE Healthcare* and Philips MS.* *Money paid to the institution.

References

- 1. Wu ML, Ko CW, Chen TY, et al. MR ventriculocisternography by using 3D balanced steady-state free precession imaging: technical note. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2005;26:1170–73 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fedorov A, Beichel R, Kalpathy-Cramer J, et al. 3D Slicer as an image computing platform for the Quantitative Imaging Network. Magn Reson Imaging 2012;30:1323–41 10.1016/j.mri.2012.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Griffiths PD, Morris J, Larroche JC, et al. Atlas of Fetal and Postnatal Brain MR. Philadelphia: Mosby/Elsevier; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bayer SA, Altman J. The Human Brain during the Third Trimester. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Eggbeer D, Bibb R, Paterson AM. Medical Modelling: The Application of Advanced Design and Rapid Prototyping Techniques in Medicine: Second Edition. Cambridge: Elsevier Imprint: Woodhead Publishing Series in Biomaterials; 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Matsumoto JS, Morris JM, Foley TA, et al. Three-dimensional physical modeling: applications and experience at Mayo Clinic. Radiographics 2015;35:1989–2006 10.1148/rg.2015140260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Barkovich AJ, Simon EM, Walsh CA. Callosal agenesis with cyst: a better understanding and new classification. Neurology 2001;56:220–27 10.1212/WNL.56.2.220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]