Abstract

Skin disease may be related with immunological disorders, external aggressions, or genetic conditions. Injuries or cutaneous diseases such as wounds, burns, psoriasis, and scleroderma among others are common pathologies in dermatology, and in some cases, conventional treatments are ineffective. In recent years, advanced therapies using human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) from different sources has emerged as a promising strategy for the treatment of many pathologies. Due to their properties; regenerative, immunomodulatory and differentiation capacities, they could be applied for the treatment of cutaneous diseases. In this review, a total of thirteen types of hMSCs used as advanced therapy have been analyzed, considering the last 5 years (2015–2020). The most investigated types were those isolated from umbilical cord blood (hUCB-MSCs), adipose tissue (hAT-MSCs) and bone marrow (hBM-MSCs). The most studied diseases were wounds and ulcers, burns and psoriasis. At preclinical level, in vivo studies with mice and rats were the main animal models used, and a wide range of types of hMSCs were used. Clinical studies analyzed revealed that cell therapy by intravenous administration was the advanced therapy preferred except in the case of wounds and burns where tissue engineering was also reported. Although in most of the clinical trials reviewed results have not been posted yet, safety was high and only local slight adverse events (mild nausea or abdominal pain) were reported. In terms of effectiveness, it was difficult to compare the results due to the different doses administered and variables measured, but in general, percentage of wound’s size reduction was higher than 80% in wounds, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index and Severity Scoring for Atopic Dermatitis were significantly reduced, for scleroderma, parameters such as Modified Rodnan skin score (MRSC) or European Scleroderma Study Group activity index reported an improvement of the disease and for hypertrophic scars, Vancouver Scar Scale (VSS) score was decreased after applying these therapies. On balance, hMSCs used for the treatment of cutaneous diseases is a promising strategy, however, the different experimental designs and endpoints stablished in each study, makes necessary more research to find the best way to treat each patient and disease.

Keywords: advanced therapy, cell therapy, dermatology, mesenchymal stem cells, skin diseases, skin injuries, stem cells, tissue engineering

Introduction

Human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) are non-hematopoietic multipotent adult progenitor cells that are found in multiple tissues. They can be easily harvested and expanded from the different tissues of adult donors, avoiding any potential ethical issues for the development of new therapies (Mushahary et al., 2018; Sierra-Sanchez et al., 2018).

The use of hMSCs for dermatological diseases seems to be interesting due to (1) their hypo-immunogenic properties, which allows its immediate use as prepared allogeneic cells without significant host reaction (Koppula et al., 2009; Liang et al., 2010; Lin and Hogan, 2011; Squillaro et al., 2016); (2) their anti-inflammatory capacity (Di Nicola et al., 2002), that can also be useful in dampening the inflammatory milieu of chronic non-healing wounds and aid in the healing process, as well as for the treatment of inflammatory chronic cutaneous diseases; and (3) their possibility to differentiate into both mesenchymal and non-mesenchymal lineages such as ectodermal keratinocyte-like cells (KLCs) (Seo et al., 2016) and dermal cells (He et al., 2007).

In addition, together with adult skin cells and skin stem cells, the role of hMSCs in normal wound healing is also important. They can contribute to re-epithelization by stimulating collagen production and reducing fibrosis and scar formation by releasing many growth factors such as epidermal growth factor (EGF), transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) (Stone Ii et al., 2018).

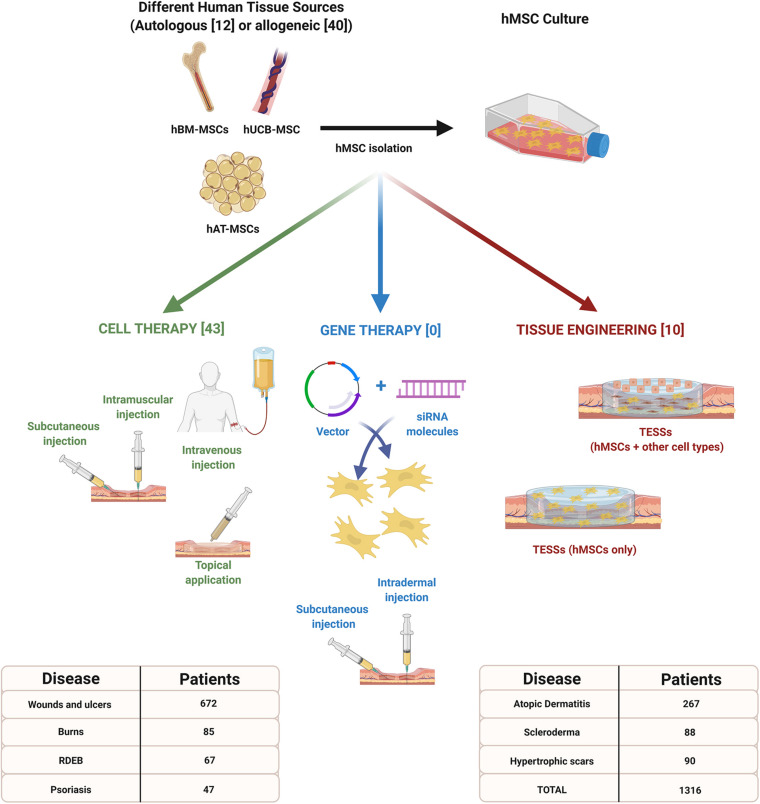

For these reasons, the development and research of hMSC based strategies in dermatology have increased in recent years (Figure 1). The objective of this review is to summarize the recent treatments (from 2015 to 2020) based on the use of hMSCs, under research or applied in patients, to treat the most common cutaneous injuries or diseases.

FIGURE 1.

Advanced therapy strategies based on the use of human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) for the treatment of different cutaneous injuries or diseases. Information included in brackets refers to the number of clinical studies reviewed between 2015 and 2020. This infographic also indicates the total number of patients expected to be recruited for each pathology. Created with Biorender.com.

Literature Search Methodology

A literature search was performed using PubMed® and ClinicalTrials.gov from 01/01/2015 to 31/12/2020. The following search terms were used: [(Mesenchymal Stem Cell) OR (Mesenchymal Stromal Cell)] AND [(Wound Healing) OR (Skin Wounds) OR (Skin Ulcers) OR (Burns) OR (Recessive Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa) OR (Psoriasis) OR (Atopic Dermatitis) OR (Scleroderma) OR (Hypertrophic Scars) OR (Skin Scars)].

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The search in PubMed® was limited to: (i) studies using hMSCs, (ii) used as advanced therapy for skin conditions, (iii) in animals or humans, and (iv) written in English or Spanish.

The search in ClinicalTrials.gov was limited to studies where recruitment status was: (Recruiting) OR (Not yet recruiting) OR (Active, not recruiting) OR (Completed) OR (Enrolling by invitation) OR (Suspended) OR (Terminated). Studies where recruitment status was (Withdrawn) OR (Unknown) were excluded.

Reviews, guidelines, protocols, and conference abstracts were excluded.

Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Cutaneous Injuries or Diseases

Wounds and Ulcers

Wound healing is a complex but well-orchestrated process divided in four overlapping phases (hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling) which plays a crucial role after a cutaneous injury, restoring function and appearance of damaged skin with minimal scarring (Reinke and Sorg, 2012). However, many factors and diseases can provoke a deregulation of the healing process, manifested as delayed wound healing (diabetes and radiation exposure) or excessive healing (hypertrophic scars) (Gurtner et al., 2008).

Preclinical in vivo Studies

At preclinical level (Table 1), since 2015, fourteen studies have analyzed the use of hMSCs for wound healing therapies in mouse or rat models. These cells have been isolated from different human tissues such as adipose tissue (hAT-MSCs) (Li et al., 2016; Hersant et al., 2019; Xiao et al., 2019; Zomer et al., 2020), bone marrow (hBM-MSCs) (He et al., 2019), umbilical cord blood (hUCB-MSCs) (Montanucci et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2017; Xu et al., 2019; Myung et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020), Wharton’s Jelly (hWJ-MSCs) (Ertl et al., 2018; Millán-Rivero et al., 2019), dermal papilla (hDP-MSCs) (Zomer et al., 2020), placenta (hP-MSCs) (Ertl et al., 2018), menstrual fluid (hMen-MSCs) (Cuenca et al., 2018), amnion (hA-MSCs) (Ertl et al., 2018), and jaw bone marrow (hJM-MSCs) (He et al., 2019). In one study the human source of hMSCs was not indicated (Chen et al., 2017). First conclusion is that all treatments based on hMSCs reported better results in terms of wound healing comparing with non-advanced or control therapies. Quantitave comparison of the effectiveness of the different hMSCs populations was difficult because in some cases the numeric information was not provided and also, the follow-up differed.

TABLE 1.

Preclinical in vivo studies of hMSCs used as advanced therapy for wounds and ulcers in the last 5 years.

| Type of advanced therapy | Cells | Type of hMSC treatment evaluated | Type of wound analyzed | Follow-up | References |

| Cell therapy | hAT-MSCs | 1-hAT-MSC + SDF-1: intradermal injection around the wound bed of 106 cells pretreated with SDF-1 2-hAT-MSC: intradermal injection around the wound bed of 106 cells | Diabetic chronic skin wounds | 10 days | Li et al., 2016 |

| hMen-MSCs | 1-hMen-MSC group: intradermal injections around each wound of 106 cells | Excisional wounds | 14 days | Cuenca et al., 2018 | |

| hAT-MSCs | 1-hAT-MSC from non-diabetic patients: subcutaneous injection of 106 cells 2-hAT-MSC from diabetic patients: subcutaneous injection of 106 cells | Pressure ulcer wounds | 21 days | Xiao et al., 2019 | |

| hBM-MSCs and hJM-MSCs | 1-hBM-MSC: intravenous injection of 2 × 106 cells/mL 2-hJM-MSC: intravenous injection of 2 × 106 cells/mL | Full-thickness skin excision | 12 days | He et al., 2019 | |

| hAT-MSCs | 1-hAT-MSC: Injection in the wound of 2 × 105 cells 2-hAT-MSC + Plasma: Injection in the wound of 2 × 105 cells with 20% of PRP activated with 10% CaCl2 | Full-thickness skin excision | 10 days | Hersant et al., 2019 | |

| hUCB-MSCs | 1-hUCB-MSC: Injection in the wound of 5 × 106 cells 2-hUCB-MSC + Hydrogel: Injection in the wound of 5 × 106 cells with a thermo-sensitive gel | Incision wounds | 21 days | Xu et al., 2019 | |

| hUCB-MSCs | 1-Irradiated wound treated with hUCB-MSCs: Implantation onto the wound bed of 1 × 105 cells in 30 μL Matrigel and subcutaneous injection around the wound of 4 × 105 cells in 120 μL Matrigel 2-Irradiated wound treated with hUCB-MSCs and PRP: Implantation onto the wound bed of 1 × 105 cells in 30 μL PRP and subcutaneous injection around the wound of 4 × 105 cells in 120 μL PRP | Combined radiation and wound injury | 21 days | Myung et al., 2020 | |

| hUCB-MSCs | 1-hUCB-MSC: subcutaneous injection around the wounds of 106 cells | Diabetic skin wounds | 14 days | Zhang et al., 2020 | |

| Cell therapy and tissue engineering | hWJ-MSCs | 1-Injected hWJ-MSC: injection of 106 cells in 100 μl buffered saline solution 2-Skin substitute: wounds covered by cellularized silk fibroin scaffold (5 × 104 hWJ-MSC seeded onto the scaffold for 4 days before surgery) 3-Combined therapy: wounds treated with hWJ-MSCs injected at the edge (106) and also cellularized silk fibroin patches (5 × 104 hWJ-MSCs seeded onto the scaffold for 4 days before surgery) | Excisional wounds | 28 days | Millán-Rivero et al., 2019 |

| Tissue engineering | hUCB-MSCs | 1-Dermal equivalent (DE): Fibrin based scaffold mixed with 4 × 105 cells + 6 × 105 cells 2-Scaffold (S): Fibrin based scaffold mixed with 4 × 105 cells | Full-Thickness Lesions | 36 days | Montanucci et al., 2017 |

| hMSCs (not defined) | 1-h-MSC group: h-MSC cell sheets constituted of 10,000 cells/cm2 + Autograft 2-Prevascularized h-MSC group: h-MSC cell sheets constituted of 10,000 cells/cm2 + 20,000 HUVEC cells/cm2 on top + Autograft | Full thickness excision wounds | 28 days | Chen et al., 2017 | |

| hUCB-MSCs | 1- hUCB-MSCs + Plasma: Platelet poor plasma gel combined with amnion (PPPA) + 106 hUCB-MSCs 2- hUCB-MSCs injected: 106 hUCB-MSCs injected subcutaneously | Full-thickness excisional skin wounds | 14 days | Yang et al., 2017 | |

| hA-MSCs, hP-MSCs and hWJ-MSCs | 1-hMSC: Matriderm® + 3 × 105 cells (hA-MSCs alone, hP-MSCs alone or hWJ-MSCs alone) 2-Prevascularized + hMSCs: Matriderm® + PLECs mixed with the respective hMSC type in an established 80:20 ratio | Full-thickness wounds | 8 days | Ertl et al., 2018 | |

| hDP-MSCs and hAT-MSCs | 1-hDP-MSC: engrafment of Integra® associated with 106 cells 2-hAT-MSC: engrafment of Integra® associated with 106 cells | Excisional wounds | 60 days | Zomer et al., 2020 |

Cell therapy

Apart from the type of hMSCs, these studies were organized according to the advanced therapy analyzed in each case (Table 1). Most of the research used hMSCs as cell therapy (CT) (Li et al., 2016; Cuenca et al., 2018; He et al., 2019; Hersant et al., 2019; Xiao et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2019; Myung et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020). Mean follow-up for this strategy was 15.4 ± 4.9 days but routes of administration varied from direct application onto the wounds (Hersant et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2019; Myung et al., 2020), intradermal injection (Li et al., 2016; Cuenca et al., 2018), and subcutaneous injection (Xiao et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2020) to intravenous injection (He et al., 2019).

hAT-MSCs were used in three studies (Li et al., 2016; Hersant et al., 2019; Xiao et al., 2019). Li et al. (2016) compared the use of hAT-MSCs (106 cells), hAT-MSCs (106 cells) pretreated with stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1) and control group, demonstrating that SDF-1 provided a protective effect on hMSCs survival and, moreover, that increased wound closure potential of diabetic chronic wounds. Xiao et al. (2019) analyzed the diabetic or non-diabetic origin of hAT-MSCs, and their potential for pressure ulcer wounds treatment, reporting that both populations (106 cells of each) suppressed inflammatory response and improved wound skin regeneration but wound healing was better in the case of non-diabetic hAT-MSCs. Hersant et al. (2019) studied the use of hAT-MSCs alone (2 × 105 cells) or combined with 20% platelet-rich plasma (PRP) revealing that wound closure were significantly higher in the combined therapy, with more expression of human VEGF and SDF-1.

The another preferred hMSC population for these studies were hUCB-MSCs, which were investigated in three articles also (Xu et al., 2019; Myung et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020). Xu et al. (2019) compared the use of hUCB-MSCs alone (5 × 106 cells) or in combination with an hydrogel, however, significant differences in terms of wound healing were only observed against control treatment groups without cells. Myung et al. (2020) design a similar experiment but using PRP instead of and hydrogel. In this case, the number of hUCB-MSCs used was 105 cells and, only combined therapy (hUCB-MSCs + PRP) significantly accelerated wound closure and enhanced neovascularization. Interestingly, Zhang et al. (2020) analyzed the use of hUCB-MSCs (106 cells), medium derived from hMSC cultures and human fibroblasts (106 cells), demonstrating that hUCB-MSCs or culture medium treatments accelerated wound healing by enhancing angiogenesis.

Remaining studies which reported the use of hMSCs as CT only, analyzed lesser-used sources such as hMen-MSCs (Cuenca et al., 2018) or hJM-MSCs (He et al., 2019). In the first case, 106 hMen-MSCs were intradermally injected and compared with a control treatment group demonstrating that wound closure was higher and a well-defined vascular network was promoted by hMen-MSCs (Cuenca et al., 2018). He et al. (2019) analyzed the intravenous injection of hBM-MSCs (2 × 106 cells/mL) or hJM-MSCs (2 × 106 cells/mL) reporting better results in terms of wound closure against control group, but without significant differences between both hMSCs sources.

Tissue engineering

Tissue engineering (TE) is another type of advanced therapy which has been investigated for the treatment of wounds and ulcers (Table 1). From 2015, five studies have reported the use of hMSCs to evaluate their potential clinical benefits as tissue-engineered skin substitute (TESS) (Chen et al., 2017; Montanucci et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2017; Ertl et al., 2018; Zomer et al., 2020). Mean time of follow-up for this strategy was 29.2 ± 20.4 days and the hMSCs populations analyzed were hUCB-MSCs (Montanucci et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2017), hA-MSCs, hP-MSCs, hWJ-MSCs (Ertl et al., 2018), hDP-MSCs, hAT-MSCs (Zomer et al., 2020), and one where the source was not indicated (Chen et al., 2017).

In the case of hUCB-MSCs, different strategies were analyzed. Montanucci et al. (2017) reported their use as part of a fibrin-based scaffold only (4 × 105 cells) or culturing hUCB-MSCs over this scaffold (6 × 105 cells). These substitutes were transplanted onto full-thickness lesions, and wounds treated with both cell layers seemed to heal slower than those treated with fibrin-based scaffold only, although the wound outcome at the end of the study looked much better in the first case. Yang et al. (2017) also administered hUCB-MSCs and compared their use as part of a TESS constituted of platelet poor plasma gel, amnion and 106 cells or as CT (106 cells injected subcutaneously). Results revealed that thickness of the newly formed epidermis layer of the TESS group grew faster to cover the wounded skin tissue than the CT and control groups.

Ertl et al. (2018) compared different hMSCs sources (hA-MSCs, hP-MSCs, hWJ-MSCs) cultured over Matriderm® alone (3 × 105 cells) or in combination with placental endothelial cells (PLECs). Interestingly, single application of each hMSC type induced a better wound reduction than the co-applications with PLECs. The best results in terms of wound healing were reported by the use of hA-MSCs. Zomer et al. (2020) also compared two types of hMSCs (hDP-MSCs, hAT-MSCs – 106 cells) associated to Integra®, demonstrating that these groups presented significantly higher closure than control group (Integra®).

Finally, Chen et al. (2017) evaluated the use of hMSCs sheets (104 cells/cm2) pre-vascularized or not, as a support treatment for gold standard therapy (autografts). Grafts from pre-vascularized group preserved most skin appendages and supporting loose connective tissues and on balance, transplantation of autografts with hMSCs significantly accelerated wound healing.

Combined advanced therapy: cell therapy and tissue engineering

Interestingly, one study evaluated a combined therapy of cell therapy and tissue engineering (Table 1). In this research, hWJ-MSCs were injected (106 cells) around the wounds, cultured over a silk fibroin scaffold and transplanted (5 × 104 cells) or both treatments were evaluated together. Results revealed that combined therapy group displayed a collagen dermis organization that was more similar to that typically observed in the normal skin of mice and exhibited better wound healing capabilities as compared with both single treatments (Millán-Rivero et al., 2019).

Brief conclusion

On balance, potential benefits of these wound healing treatments have been evaluated for four types of skin injuries: diabetic chronic wounds (Li et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2020), excisional wounds (Cuenca et al., 2018; Ertl et al., 2018; He et al., 2019; Hersant et al., 2019; Millán-Rivero et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2019; Zomer et al., 2020), pressure ulcers wounds (Xiao et al., 2019), and combined radiation and wound injuries (Myung et al., 2020). Results revealed that both hMSCs’ strategies, CT or TE, reported better results in terms of re-epithelialization, wound closure and vascularization than control and other treatment groups (autograft, injection of buffered saline solution, or hydrogel without cells) (Table 1).

Clinical Studies

Considering the use of hMSCs for clinical purposes, sixteen studies or clinical trials have been reviewed (Table 2). According to the preclinical in vivo studies, advanced therapies preferred have been cell therapy (8 studies) and tissue engineering (8 studies). The main source of hMSCs analyzed was hAT-MSCs (7) although hWJ-MSCs (2), hUCB-MSCs (2), hBM-MSCs (1), hP-MSCs (1), and non-indicated source of hMSCs (3) were also analyzed. Considering the use of autologous or allogeneic cells, allogeneic source was applied in most of the studies (14).

TABLE 2.

Clinical studies of hMSCs used as advanced therapy for wounds and ulcers in the last 5 years.

| Type of advanced therapy | Cells | Type of clinical study | N (male/female) | Age (years)a | hMSC treatment | Safety (Treatment-related adverse events) | Indication | Affected areaa | Effectivenessa (wound’s size reduction) | Follow-upa | References |

| Cell Therapy | Allogeneic hBM-MSCs | Case Report | 1 (1/0) | 66 | hBM-MSCs at a concentration of 106 cells/ml was injected around and within the lesion | None | Chronic radiation-induced skin lesion | 48 cm2 | 100% | 2 years | Portas et al., 2016 |

| Allogeneic hWJ-MSCs | Case Report | 1 (0/1) | 41 | Intradermal injection around and within the lesion of 105 cells/cm2 | None | Chronic ulcers | 42 cm2 | 75% | 14 days | Mejía-Barradas et al., 2019 | |

| Allogeneic hUCB-MSCs | Phase I Randomized Clinical Trial (Parallel Assignment-Single Blind) | 110 | (8–12) | Skin grafting and application of hUCB-MSCs (injection) | – | Traumatic heel pad injuries | – | No results posted | 90 days | NCT04219657 (Comparison Between Skin Graft Versus Skin Graft and Stem Cell Application – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov)10 | |

| Allogeneic hMSCs (not defined) | Phase I/IIa Multicenter Clinical Trial (Single Group Assignment-Open Label) | 31 | (35–85) | hMSCs applied on the wound surface on Days 0 and Week 6 | – | Chronic venous leg ulcers | – | No results posted | 12 months | NCT03257098 (Allogeneic ABCB5-positive Stem Cells for Treatment of CVU – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov)2 | |

| Autologous hMSCs (not defined) | Phase I/IIa Clinical Trial (Single Group Assignment-Open Label) | 13 | (18–85) | Topical application of hMSCs on the wound surface | – | Chronic venous leg ulcers | – | No results posted | 12 months | NCT02742844 (Clinical Trial to Investigate Efficacy and Safety of the IMP in Patients With Non-Healing Wounds Originating From Ulcers – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov)9 | |

| Allogeneic hUCB-MSCs | Phase I Non- Randomized Clinical Trial (Sequential Assignment-Open Label) | 20 | Older than 18 | 3 doses of expanded allogeneic hUCB-MSCs | – | Diabetic foot ulcers | – | No results posted | 4 months | NCT04104451 (PHASE 1, OPEN-LABEL SAFETY STUDY OF UMBILICAL CORD LINING MESENCHYMAL STEM CELLS (CORLICYTE) TO HEAL CHRONIC DIABETIC FOOT ULCERS – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov)12 | |

| Allogeneic hMSCs (not defined) | Phase I/IIa Multicenter Clinical Trial (Single Group Assignment-Open Label) | 23 | (18–85) | Two doses of allogeneic hMSCs on patients wound | – | Diabetic foot ulcers | – | No results posted | 12 months | NCT03267784 (Allogeneic ABCB5-positive Stem Cells for Treatment of DFU “Malum Perforans” – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov)3 | |

| Allogeneic hP-MSCs | Phase I Non- Randomized Clinical Trial (Single Group Assignment-Open Label) | 43 | (18–75) | Single dose of hP-MSCs gel on the wound or multidose on six consecutive days | – | Diabetic foot ulcers | – | No results posted | 34 days | NCT04464213 (Human Placental Mesenchymal Stem Cells Treatment on Diabetic Foot Ulcer – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov)11 | |

| Tissue Engineering | Allogeneic hWJ-MSCs | Randomized Clinical Trial | 5 | (30–60) | Acellular amniotic membrane seeded with hWJ-MSCs | None | Chronic diabetic wounds | 0.71 cm2 | 96.7% | 30 days | Hashemi et al., 2019 |

| Allogeneic hAT-MSCs | Phase II Multicenter Randomized Clinical Trial (Parallel Assignment-Single Blind) | 22 (14/8) 17 (13/4) – Control Group | 59.9 ± 13.3 (26–80) 68.4 ± 9.9 (43–79) | Hydrogel sheet containing 106 hAT-MSCs | No serious adverse events were observed | Diabetic foot ulcers | 1–25 cm2 | Complete wound closure was achieved for 82% of patients in the treatment group and 53% in the control group at week 12 | 12 weeks | NCT02619877 (Clinical Study to Evaluate Efficacy and Safety of ALLO-ASC-DFU in Patients With Diabetic Foot Ulcers – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov)7 (Moon et al., 2019) | |

| Autologous hAT-MSCs | Prospective clinical analysis | 6 (3/3) | 66.3 ± 9.0 | Bio-membranes constituted of 107 hAT-MSCs + platelet-rich plasma applied topically on each ulcer | None | Chronic diabetic ulcers | 6.7 cm2 | 74.5 ± 32.5% | 90 days | Stessuk et al., 2020 | |

| Allogeneic hAT-MSCs | Phase II Randomized Clinical Trial (Parallel Assignment-Quadruple Blind) | 64 | (18–80) | Hydrogel sheet containing hAT-MSCs | – | Diabetic foot ulcers | – | No results posted | 36 weeks | NCT04497805 (Clinical Study of ALLO-ASC-SHEET in Subjects With Diabetic Wagner Grade II Foot Ulcers – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov)5 | |

| Allogeneic hAT-MSCs | Phase III Multicenter Randomized Clinical Trial (Parallel Assignment-Double Blind) | 164 | (18–75) | Hydrogel sheet containing hAT-MSCs | – | Diabetic Foot ulcers | – | No results posted | 12 weeks | NCT03370874 (Clinical Study to Evaluate Efficacy and Safety of ALLO-ASC-DFU in Patients With Diabetic Foot Ulcers. – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov)6 | |

| Allogeneic hAT-MSCs | Phase II Randomized Clinical Trial (Parallel Assignment-Double Blind) | 44 | (18–80) | Hydrogel sheet containing hAT-MSCs | – | Diabetic foot ulcers | – | No results posted | 36 weeks | NCT03754465 (Clinical Study of ALLO-ASC-SHEET in Subjects With Diabetic Foot Ulcers – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov)4 | |

| Allogeneic hAT-MSCs | Observational Sutdy of Phase I Clinical Trial | 4 | (18–80) | Hydrogel sheet containing hAT-MSCs | – | Diabetic foot ulcers | – | No results posted | 24 months | NCT03183726 (A Follow-up Study to Evaluate the Safety of ALLO-ASC-DFU in ALLO-ASC-DFU-101 Clinical Trial – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov)1 | |

| Allogeneic hAT-MSCs | Phase III Multicenter Randomized Clinical Trial (Parallel Assignment-Double Blind) | 104 | (19–75) | Hydrogel sheet containing allogeneic hAT-MSCs | – | Diabetic foot ulcers | – | No results posted | 12 weeks | NCT04569409 (Clinical Study to Evaluate Efficacy and Safety of ALLO-ASC-DFU in Patients With Diabetic Wagner Grade 2 Foot Ulcers. – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov)8 |

aExpression of measures: mean ± standard deviation (range).1A Follow-up Study to Evaluate the Safety of ALLO-ASC-DFU in ALLO-ASC-DFU-101 Clinical Trial – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03183726 [Accessed January 13, 2021].2Allogeneic ABCB5-positive Stem Cells for Treatment of CVU – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov Available at: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03257098?term=mesenchymal+stem+cells&cond=Wound+of+Skin&strd_s=01%2F01%2F2015&strd_e=12%2F31%2F2020&draw=2&rank=4 [Accessed January 11, 2021].3Allogeneic ABCB5-positive Stem Cells for Treatment of DFU “Malum Perforans” – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov Available at: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/study/NCT03267784?term=mesenchymal+stem+cells&cond=Skin+ulcer&strd_s=01%2F01%2F2015&strd_e=12%2F31%2F2020&draw=2&rank=19 [Accessed January 13, 2021].4Clinical Study of ALLO-ASC-SHEET in Subjects With Diabetic Foot Ulcers – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov Available at: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/study/NCT03754465?term=mesenchymal+stem+cells&cond=Skin+ulcer&strd_s=01%2F01%2F2015&strd_e=12%2F31%2F2020&draw=2&rank=13 [Accessed January 13, 2021].5Clinical Study of ALLO-ASC-SHEET in Subjects With Diabetic Wagner Grade II Foot Ulcers – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov Available at: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/study/NCT04497805?term=mesenchymal+stem+cells&cond=Skin+ulcer&strd_s=01%2F01%2F2015&strd_e=12%2F31%2F2020&draw=2&rank=10 [Accessed January 13, 2021].6Clinical Study to Evaluate Efficacy and Safety of ALLO-ASC-DFU in Patients With Diabetic Foot Ulcers. – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov Available at: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/study/NCT03370874?term=mesenchymal+stem+cells&cond=Skin+ulcer&strd_s=01%2F01%2F2015&strd_e=12%2F31%2F2020&draw=2&rank=12 [Accessed January 13, 2021].7Clinical Study to Evaluate Efficacy and Safety of ALLO-ASC-DFU in Patients With Diabetic Foot Ulcers – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov Available at: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/study/NCT02619877?term=mesenchymal+stem+cells&cond=Skin+ulcer&strd_s=01%2F01%2F2015&strd_e=12%2F31%2F2020&draw=2&rank=11 [Accessed January 13, 2021].8Clinical Study to Evaluate Efficacy and Safety of ALLO-ASC-DFU in Patients With Diabetic Wagner Grade 2 Foot Ulcers. – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov Available at: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04569409?term=mesenchymal+stem+cells&cond=Skin+ulcer&strd_s=01%2F01%2F2015&strd_e=12%2F31%2F2020&draw=2&rank=21 [Accessed January 13, 2021].9Clinical Trial to Investigate Efficacy and Safety of the IMP in Patients With Non-Healing Wounds Originating From Ulcers – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov Available at: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02742844?term=mesenchymal+stem+cells&cond=Wound+of+Skin&strd_s=01%2F01%2F2015&strd_e=12%2F31%2F2020&draw=1&rank=6 [Accessed January 11, 2021].10Comparison Between Skin Graft Versus Skin Graft and Stem Cell Application – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov Available at: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/study/NCT04219657?term=mesenchymal+stem+cells&cond=Wound+of+Skin&strd_s=01%2F01%2F2015&strd_e=12%2F31%2F2020&draw=2&rank=1 [Accessed January 11, 2021].11Human Placental Mesenchymal Stem Cells Treatment on Diabetic Foot Ulcer – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov Available at: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04464213?term=mesenchymal+stem+cells&cond=Skin+ulcer&strd_s=01%2F01%2F2015&strd_e=12%2F31%2F2020&draw=2&rank=3 [Accessed January 11, 2021].12PHASE 1, OPEN-LABEL SAFETY STUDY OF UMBILICAL CORD LINING MESENCHYMAL STEM CELLS (CORLICYTE®) TO HEAL CHRONIC DIABETIC FOOT ULCERS – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov Available at: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/study/NCT04104451?term=mesenchymal+stem+cells&cond=Skin+ulcer&strd_s=01%2F01%2F2015&strd_e=12%2F31%2F2020&draw=2&rank=6 [Accessed January 13, 2021].

Cell therapy

The use of hMSCs as CT for the treatment of wounds and ulcers is an interesting alternative against conventional therapies. In this sense, from 2015 to 2020, eight studies have reported their use (Table 2): two of them were case reports and results of efficiency, in terms of wound’s size reduction, were published (Portas et al., 2016; Mejía-Barradas et al., 2019).

Portas et al. (2016) evaluated the injection of 106 allogeneic hBM-MSCs/ml around and within chronic radiation-induced skin lesion of one patient (66 years old). After 3 months, wound size was completely reduced without non-adverse events. Moreover, the use of hBM-MSCs reduced inflammation process (marked decrease of β1 integrin expression on lymphocytes) and improved vasculature and quality of the skin.

Mejía-Barradas et al. (2019) studied the intradermal injection around and within the lesion of 105 allogeneic hWJ-MSCs/cm2, in one patient (41 years old) with chronic ulcers (42 cm2) reporting an effectiveness of 75%, considering wound size reduction after 14 days. Neo-vascularization and formation of collagen fibers were also observed in regenerated skin and the number of proinflammatory cytokines decreased.

Rest of studies reviewed were clinical trials (Phase I or Phase I/IIa), however, no published results are posted at this time. One of them analyzed the topical application of autologous hMSCs on the wound surface for the treatment of chronic venous leg ulcers (NCT02742844), meanwhile, the rest evaluated allogeneic cells such as hUCB-MSCs (NCT04219657 and NCT04104451), hP-MSCs (NCT04464213), or hMSCs (NCT03257098 and NCT03267784) for the treatment of different types of wounds (diabetic foot ulcers, traumatic heel pad injuries and chronic venous leg ulcers).

Considering protocols approved for all these studies, there is not a preferred source of hMSCs for the development of cell therapy strategies for wounds and ulcers, although in all cases, cells will be applied or injected around and into the wounds to evaluate their potential clinical safety and effect.

Tissue engineering

From 2015, eight studies have evaluated the use of hMSCs as a component of TESSs for the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers (Table 2). Until now, only three of them have published results of safety and effectiveness (Hashemi et al., 2019; Moon et al., 2019; Stessuk et al., 2020).

Seven studies evaluated the use of allogeneic hMSCs isolated from adipose tissue (6) or Wharton’s Jelly (1) and one study reported the use of autologous hAT-MSCs. Most of them were Phase I, II, or III clinical trials although one of them was an observational study (NCT03183726).

In all cases, strategy was based on manufacturing sheets of different biomaterials combined with the different hMSCs sources to evaluate their engraftment into diabetic foot ulcers. Those studies with published results applied different hMSCs: allogeneic hWJ-MSCs (Hashemi et al., 2019), allogeneic hAT-MSCs (Moon et al., 2019) and autologous hAT-MSCs (Stessuk et al., 2020).

Hashemi et al. (2019) evaluated the engraftment of an acellular amniotic membrane seeded with hWJ-MSCs in 5 patients. No adverse events were reported, and wound size after 9 days significantly declined (96.7% from original size).

Moon et al. (2019) (NCT02619877) manufactured hydrogel sheets containing 106 allogeneic hAT-MSCs/sheet for the treatment of 22 patients with diabetic foot ulcers and compared the results with a standard treatment (17 patients). Outcomes revealed that no serious adverse events were observed, complete wound closure was achieved for 82% in the treatment group and 53% in the control group at week 12 and Kaplan-Meier median times to complete closure were 28.5 and 63.0 days for the treatment group and the control group, respectively.

In a case where autologous hAT-MSCs were used to fabricate bio-membranes constituted of 107 hAT-MSCs and platelet-rich plasma, 6 patients were treated. Conclusions revealed that there was granulation tissue formation starting from 7 days after topical application and after 90 days, a healed and re-epithelialized tissue was observed. No adverse events were reported (Stessuk et al., 2020).

Remaining studies reviewed have not published results yet (NCT04497805, NCT03370874, NCT03754465, NCT03183726, and NCT04569409), but incorporation of hAT-MSCs into a hydrogel was the methodology selected in all cases.

Brief conclusion

On balance, preferred hMSC population for the treatment of wounds and ulcers are the allogeneic hAT-MSCs, mainly as tissue engineering strategy. Although information about the results is limited and the standardization of a cell dose is difficult, the use of hMSCs could improve the treatment of patients with these skin conditions, because published results are hopeful.

Considering only those studies were results were posted from 2015 to 2020, 35 patients have been treated (2 with CT strategy and 33 with TE strategy), all of them with chronic skin ulcers (associated to diabetes or not) and a range of wound size between 0.71 and 48 cm2. The weighted mean effectiveness, based on the wound’s size reduction, was of 87.5 ± 12.5% for the CT treatments (closure time: from 7 to 90 days) and 82.7 ± 5.8% for TE therapies (closure time: from 9 to 90 days).

Burn Injuries

The majority of burn injuries are minor and either do not require treatment or can be treated by any caregiver, however, in the case of severe burns they can lead to a profound systemic response and have serious long-term effects on patients (Porter et al., 2016). Moreover, failure to properly treat these injuries will lead to rapid development of organ failure and death (Greenhalgh, 2019).

Preclinical in vivo Studies

At preclinical level, five studies [one CT (Pourfath et al., 2018) and four TE strategies (Steffens et al., 2017; Kaita et al., 2019; Mahmood et al., 2019; Nazempour et al., 2020)] have evaluated the use of hMSCs for burn injuries in the last 5 years (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Preclinical in vivo studies of hMSCs used as advanced therapy for burns in the last 5 years.

| Type of Advanced Therapy | Cells | Type of hMSC treatment evaluated | Type of wound analyzed | Follow-up | References |

| Cell therapy | hWJ-MSCs | 1-hWJ-MSC: 5 × 105 cells using cell spray method | Third degree burns | 21 days | Pourfath et al., 2018 |

| Tissue engineering | hDT-MSCs | 1-hDT-MSCs + poly-D,L-lactic acid (PDLLA) + laminin-332 protein (lam): 105 cells + 105 keratinocytes + scaffold 2- hDT-MSCs + PDLLA: 105 cells + 105 keratinocytes + scaffold | Third degree burns | 9 days | Steffens et al., 2017 |

| hUCB-MSCs | 1-hUCB-MSC + plasma: 2.5 × 104 derived fibroblast cells + 3 × 104 derived keratinocyte cells + scaffold | Burn injury | 20 days | Mahmood et al., 2019 | |

| hAT-MSCs | 1-Fresh hAT-MSCs: 5 × 104 cells on artificial dermis 2-Frozen hAT-MSCs: 5 × 104 cells on artificial dermis | Third degree burn wound | 12 days | Kaita et al., 2019 | |

| hWJ-MSCs | 1-hWJ-MSC + acellular matrix: 2 × 106 hWJSCs seeded onto acellular dermal matrix scaffold | Third-degree burn | 21 days | Nazempour et al., 2020 |

Cell therapy

Pourfath et al. (2018) evaluated a cell spray application of 5 × 105 hWJ-MSCs over third degree burns. After 21 days of follow-up, wounds showed a higher degree of re-epithelialization compared to the control group, and hemorrhage was also completely ceased by the end of the second week post application (Table 3).

Tissue engineering

In this case, each of the four studies reported, used a different hMSCs population (Table 3): deciduous teeth (hDT-MSCs) (Steffens et al., 2017), hUCB-MSCs (Mahmood et al., 2019), hAT-MSCs (Kaita et al., 2019) and hWJ-MSCs (Nazempour et al., 2020). The average follow-up of these studies was 15.5 ± 5.9 days and third-degree burns in mice and rats was the preferred model, although the type of TESS evaluated varied.

Steffens et al. (2017) embedded hDT-MSCs into a poly-D, L-lactic acid (PDLLA) scaffold and included 105 keratinocytes. Apart from that, they also evaluated the incorporation, or not, of laminin-332 to the design. Considering average size of the lesions, no statistical difference between the different groups were observed, although those groups which incorporated laminin-332 reported a greater reduction.

Mahmood et al. (2019) analyzed an interesting approach where hUCB-MSCs were in vitro differentiated into fibroblasts and keratinocytes. Derived fibroblasts (2.5 × 104 cells) were embedded into a plasma scaffold and then, derived keratinocytes (3 × 104 cells) were overlaid. This was compared with a control group without any treatment, revealing that contraction was 97.6 ± 0.61% for hUCB-MSCs group against 87.57 ± 1.30% in control group and complete healing was faster for hUCB-MSCs group (20.00 ± 2.00 vs. 27.67 ± 2.51 days).

Kaita et al. (2019) studied if differences between fresh hAT-MSCs (5 × 104) or frozen hAT-MSCs (5 × 104) cultured over an artificial dermis exists. Results indicated that after day 12 post treatment, a significant difference in the percentage of wound closure was observed between the hAT-MSCs groups and control group but expression of Type I and III collagen was higher when frozen hAT-MSCs were used.

Finally, Nazempour et al. (2020) evaluated the use of 2 × 106 hWJ-MSCs seeded onto acellular dermal matrix scaffold and compared the results with a conventional treatment (silver sulfadiazine ointment). Wound size decreased in a better way in group where hWJ-MSCs were used (87.6%).

Brief conclusion

In conclusion, for burn injuries the purpose is to develop a TESS which could supply the lack of health tissue around the wounds. Although, there is not a preferred hMSCs source and more investigation to find the best scaffold is required, it is clear that the use of advanced therapy could improve the treatment of these injuries, even when frozen cells are used.

Clinical Studies

For clinical purposes, six studies or clinical trials have investigated the use of hMSCs for the treatment of burn injuries (Table 4). In contrast to the tendency observed in the case of preclinical in vivo studies analyzed, the advanced therapy most studied was CT (4 studies vs. 2 studies in the case of TE). Three sources of hMSCs were applied: hAT-MSCs (3), hBM-MSCs (2), and hUCB-MSCs (2). Allogeneic cells were used in four studies and autologous cells only in one. One clinical trial did not define the use of allogeneic or autologous hAT-MSCs (NCT03686449).

TABLE 4.

Clinical studies of hMSCs used as advanced therapy for burns in the last five years.

| Type of advanced therapy | Cells | Type of clinical study | N (male/female) | Age (years)a | hMSC treatment | Safety (treatment-related adverse events) | Indication | Total body surface area (TBSA) affecteda | Effectivenessa (Wound’s size reduction) | Follow-upa | References |

| Cell therapy | Allogeneic hBM-MSCs | Case Report | 1 (1/0) | 26 | Topical application of 106 cells per 100 cm2 | None | Severe thermal (flame) burns | 60% | — | 3 years | Mansilla et al., 2015 |

| Autologous hBM-MSCs Allogeneic hUCB-MSCs | Case-control Randomized prospective study | Autologous hBM-MSCs 20 | 23 ± 1.9 (20–27) | 2 injections in the burned area (105 hBM-MSC/ml) | 25% early complications 45% late complications | Thermal full thickness burns | 17 ± 2.94% (12–22) | — | 6 months | Abo-Elkheir et al., 2017 | |

| Allogeneic hUCB-MSCs 20 | 22.9 ± 2.73 (18–29) | Topical application and injection | 70% early complications 70% late complications | 15.95 ± 2.89% (10–20) | |||||||

| Control Group 20 | 25.3 ± 4.38 (18–35) | Early excision and graft-treated group | 50% early complications 95% late complications | 18.15 ± 2.87% (15–25) | |||||||

| Allogeneic hUCB-MSCs | Case Report | 1 | — | 3 × 106 cells/mL applied topically (4 mL) | Minimal hyperpigmentation and hypertrophic scarring | Severe burn injury | 70% | 97% | 6 years | Jeschke et al., 2019 | |

| hAT-MSCs | Randomized Clinical Trial (Parallel Assignment-Open Label) | 33 | Older than 18 | hAT-MSCs-autologous keratinocyte suspension | – | Burn with full-thickness skin loss | – | No results posted | 1 month | NCT03686449 (Autologous Keratinocyte Suspension Versus Adipose-Derived Stem Cell-Keratinocyte Suspension for Post-Burn Raw Area – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov)3 | |

| Tissue engineering | Allogeneic hAT-MSCs | Phase I Clinical Trial (Single Group Assignment- Open Label) | 5 | Older than 18 | Hydrogel sheet containing allogeneic hAT-MSCs | – | Second-degree burn wounds | – | No results posted | 4 weeks | NCT02394873 (A Study to Evaluate the Safety of ALLO-ASC-DFU in the Subjects With Deep Second-degree Burn Wound – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov)1 |

| Allogeneic hAT-MSCs | Observational Study of Phase I Clinical Trial | 5 | Older than 18 | Hydrogel sheet containing allogeneic hAT-MSCs | – | Second-degree burn wounds | – | No results posted | 24 months | NCT03183622 (A Follow-up Study to Evaluate the Safety of ALLO-ASC-DFU in ALLO-ASC-BI-101 Clinical Trial – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov)2 |

aExpression of measures: mean ± standard deviation (range).

1A Study to Evaluate the Safety of ALLO-ASC-DFU in the Subjects With Deep Second-degree Burn Wound – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov Available at: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02394873?term=mesenchymal+stem+cells&recrs=abdefgh&cond=burns&strd_s=01%2F01%2F2015&strd_e=12%2F31%2F2020&draw=2&rank=5 [Accessed January 13, 2021].

2A Follow-up Study to Evaluate the Safety of ALLO-ASC-DFU in ALLO-ASC-BI-101 Clinical Trial – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov Available at: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/study/NCT03183622?term=mesenchymal+stem+cells&recrs=abdefgh&cond=burns&strd_s=01%2F01%2F2015&strd_e=12%2F31%2F2020&draw=2&rank=6 [Accessed January 13, 2021].

3Autologous Keratinocyte Suspension Versus Adipose-Derived Stem Cell-Keratinocyte Suspension for Post-Burn Raw Area – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov Available at: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03686449?term=mesenchymal+stem+cells&recrs=abdefgh&cond=burns&strd_s=01%2F01%2F2015&strd_e=12%2F31%2F2020&draw=2&rank=4 [Accessed January 13, 2021].

Cell therapy

Since 2015, four studies have evaluated the use of CT for the treatment of severe burn thermal (or not) injuries where a full-thickness skin were lost (Table 4). Two research rereviewed were case report (Mansilla et al., 2015; Jeschke et al., 2019) and the other two were clinical trials (Abo-Elkheir et al., 2017) and (NCT03686449) although in the second case, no results were posted.

Mansilla et al. (2015) reported the use of allogeneic hBM-MSCs in one patient (26 years old) by topical application of 106 hBM-MSCs per 100 cm2, combined with autologous meshed skin grafting for severe thermal burns. No adverse events were observed and after 35 days of treatment, with two courses of hBM-MSCs, the complete epithelialization of the wounds were too slow. The other case report used allogeneic hUCB-MSCs for the treatment of severe burns injuries of one patient (Total Body Surface Area-TBSA-affected of 70%). 3 × 106 cells/mL were applied topically and results revealed that 97% of wounds were closed with minimal hyperpigmentation and hypertrophic scarring (Jeschke et al., 2019).

One of the clinical trials included, compared the use of a suspension constituted of hAT-MSCs and autologous keratinocytes with other alternative treatments, however, no results were posted (NCT03686449).

Abo-Elkheir et al. (2017) published the results of an interesting clinical trial where compared three types of treatments for thermal full thickness burns: autologous hBM-MSCs (2 injections in the burned area – 1 ml/cm2 of 105 hMSC/ml suspension), allogeneic hUCB-MSCs (topical application and injection) and early excision and graft-treated group (N = 20 for each group). Safety results revealed that in the case of hBM-MSCs; 25% of cases presented early complications (infection or partial loss of graft) and 45% late complications (hypo- or hyperpigmentation, contracture scar or hypertrophic scar), in the case of hUCB-MSCs; 70% of cases presented early complications and late complications and in the control group; 50% of cases presented early complications and 95% late complications. Percentage of burn extent was significantly reduced in both hMSC groups as compared to early control group.

Tissue engineering

Two clinical trials (interventional and observational) evaluated the use allogeneic hAT-MSCs as part of a hydrogel sheet for the treatment of second-degree burn wounds (NCT02394873 and NCT03183622), however, no results have been posted yet (Table 4).

Brief conclusion

On balance, at clinical level the preferred hMSC-based advanced therapy is CT in contrast with preclinical studies where the TE is the most investigated. This means that researches are focusing on develop TESS that mimics native skin in a better way, however, more investigation is required and for these reason the translation of CT therapies (which were more studied in the previous years) is more widespread.

Considering all clinical studies reviewed, 42 patients have been recruited to analyze the potential benefits of hMSCs for the treatment of burn injuries. Most of the studies used allogeneic hMSCs but, in some cases results, were not successful (Mansilla et al., 2015), in contrast to one case where the comparison between autologous or allogeneic CT strategy reported that the best wound closure was achieved when autologous hBM-MSCs were used. In the same study, safety parameters revealed that the use of autologous cells was less dangerous for the patient’s health (Abo-Elkheir et al., 2017). However, rest of studies which evaluated the use of allogeneic cells did not report the presence of adverse events. The weighted mean TBSA treated with hMSCs-based CT strategies has been 18.8 ± 10.4%, until now.

Recessive Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa

Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (DEB) is a genetic skin disorder that usually presents at birth. It is due to the presence of pathogenic variants of the gene COL7A1 and depending on inheritance pattern is divided into two types: dominant dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (DDEB) and recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (RDEB). In DDEB, blistering is often mild but nonetheless heals with scarring. In the case of RDEB, clinical disorders are severe including skin fragility manifest by blistering with minimal trauma that heals with milia and scarring, even in in the neonatal period and therefore, the lifetime risk of aggressive squamous cell carcinoma is higher than 90% (Pfendner and Lucky, 2018).

Preclinical in vivo Studies

Recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa is a rare disease and for this reason the number of studies in the last 5 years is limited (Table 5). In addition, due to their genetic etiology its study requires complex techniques of genetic engineering which long-term effect in humans is yet unknown.

TABLE 5.

Preclinical in vivo and clinical studies of hMSCs used as advanced therapy for recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa in the last 5 years.

| PRECLINICAL IN VIVO STUDIES | |||||||||||

| Type of Advanced Therapy | Cells | Disease model and Treatments | Animals | Type of wound analyzed | Follow-up | References | |||||

| Cell therapy | hBM-MSCs | 1–8 h after wounding, 2 × 106 hBM-MSCs were injected at the wound edges and this procedure was repeated 48 h after the first injection 2–8 h after wounding, PBS alone were injected at the wound edges and this procedure was repeated 48 h after the first injection | C7-hypomorphic mice and wild-type littermates | Two full thickness skin wounds were incised at the mid-back | 12 weeks | Kühl et al., 2015 | |||||

| Tissue engineering, cell therapy and gene therapy | hUCB-MSCs | 1-Skin substitute constituted of RDEB fibroblasts mixed with COL7A1-transduced MSCs at a 1:1 ratio. Primary RDEB keratinocytes were then seeded on top 2-Skin substitute constituted of RDEB fibroblasts alone. Primary RDEB keratinocytes were then seeded on top 3-Skin substitute constituted of wild type fibroblasts alone. Wild type keratinocytes were then seeded on top 4-After 6–8 weeks mice treated with human skin substitutes received two intradermal injections of 0.5 × 106 engineered MSCs in 50 ul buffered saline solution each or injected with 2 × 106 engineered MSCs in 150 ul buffered saline solution via tail vein. Controls without cells were also injected | 7 Immunod- eficient NOD-scid IL2Rgammanull mice | Full-thickness wound followed by devitalization of mouse skin | 8–10 weeks | Petrova et al., 2020 | |||||

| CLINICAL STUDIES | |||||||||||

| Type of advanced therapy | Cells | Type of clinical study | N (male/female) | Age (years)a | hMSC treatment | Safety (Treatment-related adverse events) | Total Body Surface Area (TBSA) affecteda | Effectivenessa | Follow-upa | References | |

| Cell therapy | Allogeneic hBM-MSCs | Phase I/II Clinical Trial (Single Group Assignment- Open Label) | 10 (5/5) | 4.8 ± 3.8 (1–11) | Three intravenous infusions of hBM-MSCs on Days 0, 7, and 28, at a dose of 1× 106 to 3 × 106 cells/kg | 78% of adverse events were not related to the hBM-MSCs infusions 2 severe events of DMSO odor Mild nausea and abdominal pain and bradycardia were observed during 2 infusions (each) | 23.2 ± 11.2% | Mean quality of life score (higher is worse) reported by parents was 41.9 at baseline vs. 39.0 at day 180 | 180 days | Petrof et al., 2015 | |

| Allogeneic hBM-MSCs | Randomized clinical trial (parallel assignment- double blind) | 7 (3/4) | 3.8 ± 2 (1–6) | Cyclosporine suspension in a dose of 5 mg/kg per day Intravenous injection of hBM-MSCs (from 70 to 150 × 106 cells/patient) | None | 67.1 ± 11.1% (50–80%) | The mean number of new blister formation decreased significantly after treatment from 43 ± 21.2 to 9 ± 10.97 in cyclosporine’s group and from 49 ± 1.8 to 13 ± 8.5 in placebo’s group | 1 year | El-Darouti et al., 2016 | ||

| 7 (3/4) | 7.7 ± 6.4 (2–20) | Placebo suspension without cyclosporine Intravenous injection of hBM-MSCs (from 70 to 150 × 106 cells/patient) | 64.3 ± 18.1% (40–80%) | ||||||||

| Allogeneic hBM-MSCs | Phase II Clinical Trial | 10 (5/5) | 9.1 ± 7 (1.8–22.1) | hBM-MSCs infusions | 16% of transplants complicated by veno-occlusive disease of the liver Low rates of acute (0%) and chronic (10%, n = 1) graft versus host disease | 49.5% | Reduction of surface area of blisters/erosion to 27.5% | 1 year | (Ebens et al., 2019) NCT02582775 (MT2015-20: Biochemical Correction of Severe EB by Allo HSCT and Serial Donor MSCs – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov)3 | ||

| Allogeneic hBM-MSCs | Phase I/II Clinical Trial (Single Group Assignment- Open Label) | 10 (5/5) | 36.1 ± 9 (26–55) | 2 intravenous infusions of hBM-MSCs (24 × 106 to 4 × 106 cells/kg) | None | - | There was a transient reduction in disease activity scores (8/10 subjects) and a significant reduction in itch | 1 year | (Rashidghamat et al., 2020) NCT02323789 (Mesenchymal Stromal Cells in Adults With Recessive Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov)2 | ||

| Allogeneic hUCB-MSCs | Phase I/II Clinical Trial (Single Group Assignment- Open Label) | 5 | (10–60) | Intravenous injection of 3 doses of 3 × 106 cells/kg | – | − | No results posted | 8 months | NCT04520022 (Safety and Effectiveness Study of Allogeneic Umbilical Cord Blood-derived Mesenchymal Stem Cell in Patients With RDEB – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov)4 | ||

| Allogeneic haploidentical hBM-MSCs | Phase I/II Clinical Trial (Single Group Assignment- Open Label) | 9 | (1–18) | Intravenous injection of 3 doses of 2× 106 to 3 × 106 cells/kg | − | − | No results posted | 5 years | NCT04153630 (Safety Study and Preliminary Efficacy of Infusion Haploidentical Mesenchymal Stem Cells Derived From Bone Marrow for Treating Recessive Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov)5 | ||

| Allogeneic hMSCs (not defined) | Phase I/IIa Multicenter Clinical Trial (Single Group Assignment- Open Label) | 16 | Up to 55 | Intravenous injection of 3 doses of 2 × 106 cells/kg | – | − | No results posted | 24 months | NCT03529877 (Allogeneic ABCB5-positive Stem Cells for Treatment of Epidermolysis Bullosa – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov)1 | ||

aExpression of measures: mean ± standard deviation (range).

1Allogeneic ABCB5-positive Stem Cells for Treatment of Epidermolysis Bullosa – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov Available at: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03529877?term=mesenchymal+stem+cells&recrs=abdefgh&cond=Recessive+Dystrophic+Epidermolysis+Bullosa&strd_s=01%2F01%2F2015&strd_e=12%2F31%2F2020&draw=2&rank=3 [Accessed January 13, 2021].

2Mesenchymal Stromal Cells in Adults With Recessive Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02323789 [Accessed February 14, 2021].

3MT2015-20: Biochemical Correction of Severe EB by Allo HSCT and Serial Donor MSCs – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02582775 [Accessed February 14, 2021].

4Safety and Effectiveness Study of Allogeneic Umbilical Cord Blood-derived Mesenchymal Stem Cell in Patients With RDEB – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov Available at: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04520022?term=mesenchymal+stem+cells&recrs=abdefgh&cond=Recessive+Dystrophic+Epidermolysis+Bullosa&strd_s=01%2F01%2F2015&strd_e=12%2F31%2F2020&draw=2&rank=1 [Accessed January 13, 2021].

5Safety Study and Preliminary Efficacy of Infusion Haploidentical Mesenchymal Stem Cells Derived From Bone Marrow for Treating Recessive Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov Available at: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04153630?term=mesenchymal+stem+cells&recrs=abdefgh&cond=Recessive+Dystrophic+Epidermolysis+Bullosa&strd_s=01%2F01%2F2015&strd_e=12%2F31%2F2020&draw=2&rank=2 [Accessed January 13, 2021].

At preclinical level (Table 5), only two studies have investigated the use of hBM-MSCs (Kühl et al., 2015) or hUCB-MSCs (Petrova et al., 2020). Interestingly, these studies show a different strategy to evaluate the potential effect of advanced therapies for RDEB. In the first case, Kühl et al. (2015) used a hypomorphic mouse model of dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa, meanwhile, Petrova et al. (2020) developed TESS manufactured with RDEB fibroblasts and keratinocytes and compared the results with a TESS fabricated with hUCB-MSCs transduced with COL7A1 gene.

Kühl et al. (2015) evaluated a cell therapy for 12 weeks where after provoking full thickness skin wounds, 2 × 106 hBM-MSCs were injected at the wound edges at 8 and 56 h after generating the wounds. Results revealed that after 3, 6, and 7 days, the MSC-injected wounds remained significantly smaller than PBS-injected wounds (day 3, 38.1 ± 2.7% vs. 59.3 ± 6.4%; day 6, 30.3 ± 2.4% vs. 39.7 ± 4.1%; and day 7, 21.8 ± 1.6% versus 31.8 ± 4.7%) and moreover, after 12 weeks, healed MSC-injected hypomorphic wounds contained 2.1 ± 0.5 immature anchoring fibrils/μm lamina densa with a thickness of 19.6 ± 1.3 nm which was lower than wild-type skin (3.8 ± 0.3 anchoring fibrils/μm lamina densa with an average maximal thickness of 32.5 ± 1.6 nm), but fibrils were clearly functional and stabilized the skin (Kühl et al., 2015).

Research by Petrova et al. (2020) combined CT, TE and gene therapy (GT) which are the three types of advanced therapies. In this case, full-thickness wounds were generated and then devitalized. Authors manufactured three types of TESSs: (i) RDEB fibroblasts mixed with COL7A1-transduced hUCB-MSCs at a 1:1 ratio and primary RDEB keratinocytes seeded on top; (ii) RDEB fibroblasts alone and primary RDEB keratinocytes seeded on top; and (iii) wild type fibroblasts alone and wild type keratinocytes seeded on top. In addition, after 6–8 weeks mice received two intradermal injections of 0.5 × 106 COL7A1-transduced hUCB-MSCs or 2 × 106 COL7A1-transduced hUCB-MSCs via tail vein (controls without cells were also injected). Results revealed that mice treated with TESSs constituted of hUCB-MSCs had an abundance of sublamina densa fibrillary structures that bore the ultrastructural characteristics of normal anchoring fibril. Evaluating cell therapy, small blisters were seen in the control intradermal-injected animals but not in the animals that received hUCB-MSCs intradermal injection. No evidence were observed that systematically injected hUCB-MSCs migrated to sites of skin grafts.

On balance, the use of hMSCs for the treatment of RDEB it is a promising strategy, however, due to genetic conditions of the disease, the combination of different advanced therapies seems to be the best option which implies more preclinical studies before translating to the clinical environment.

Clinical Studies

Since 2015, seven clinical trials have evaluated the use of hMSCs as CT strategy for the treatment of RDEB (Table 5). All of them used allogeneic hMSCs ant the most studied population was hBM-MSCs (5), although hUCB-MSCs (1) and not-defined hMSCs (1) were also analyzed.

Petrof et al. (2015) evaluated the application of three intravenous injections of allogeneic hBM-MSCs (1×106 cells/kg to 3 × 106 cells/kg) in 10 patients (4.8 ± 3.8 years old). They reported that most of the adverse events observed were not related to the hBM-MSCs and after 180 days of follow-up skin biopsies revealed no increase in type VII collagen expression and no new anchoring fibrils formation but quality of life increased and pain decreased.

Similar clinical studies were developed by Ebens et al. (NCT02582775) and Rashidghamat et al. (NCT02323789). In each clinical trial 10 patients received intravenous infusions of hBM-MSCs [2× 106 cells/kg to 4 × 106 cells/kg (Rashidghamat et al., 2020)]. In the case of Ebens et al. two of the transplants provoked veno-occlusive disease of the liver and 1 of the patients developed graft versus host disease (Ebens et al., 2019). After 1 year of follow-up, skin biopsies showed stable (n = 7) to improved (n = 2) type VII collagen protein expression and gain of anchoring fibril components (n = 3) (Ebens et al., 2019) and total blister count over the entire body surface area showed a decrease compared with baseline (Rashidghamat et al., 2020).

El-Darouti et al. (2016) also used hBM-MSCs for the treatment of RDEB but in this case, they compared the intravenous injection of these cells (70 × 106 cells to 150 × 106 cells) with or without a cyclosporine suspension (5 mg/kg) in 14 patients. No adverse events were observed in any of the and the mean number of new blister formation decreased from 43 ± 21.2 to 9 ± 10.97 in cyclosporine’s group and from 49 ± 1.8 to 13 ± 8.5 in the other group. After 1 year, improvement was continuous in two patients from cyclosporine’s group, whereas the remaining patients showed gradual loss of improvement.

Finally, other three clinical trials evaluated the use of allogeneic hUCB-MSCs (NCT04520022), allogeneic haploidentical hBM-MSCs (NCT04153630) and allogeneic hMSCs (NCT03529877). In all cases the route of administration was intravenous injection (3 doses of 2 × 106 cells/kg to 3 × 106 cells/kg), however, no results are posted.

On balance, advanced therapies based on the use of hMSCs for the treatment of RDEB seems to be a promising strategy, although more research is required. Until now, all clinical studies have evaluated the use of these cells as cell therapy, however, at preclinical level, one study has investigated the combination of CT, TE, and GE, but its translation to a clinical environment is still far from achieving. The genetic conditions of the disease and the lack of long-term information about genetic modification of cells are a big handicap. Considering the cell source, hBM-MSCs were the population most used (5/7) and the route of administration preferred was intravenous injection.

Psoriasis

Psoriasis is a long-term (chronic) inflammatory skin disease with a strong genetic predisposition and autoimmune pathogenic traits that causes erythematous, itchy scaly patches. Worldwide prevalence is about 2% (Christophers, 2001). Five types of psoriasis have been reported: (i) plaque psoriasis or psoriasis vulgaris; (ii) eruptive psoriasis, which is characterized by scaly teardrop-shaped spots; (iii) inverse psoriasis, also called intertriginous or flexural psoriasis that is usually found in folds of skin; (iv) pustular psoriasis; and (v) erythrodermic psoriasis, which is a rare but very serious complication of psoriasis (Boehncke and Schön, 2015).

Due to the etiology of the psoriasis, the anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory capacities of hMSCs (Di Nicola et al., 2002) have emerged as a useful tool for the development of possible advanced therapies, mainly CT. Their potential has been demonstrated in vitro, being capable of restoring the physiological phenotypical profile of psoriatic MSCs (Campanati et al., 2018).

Preclinical in vivo Studies

Since 2015, five in vivo studies have evaluated the potential use of hMSCs as CT for psoriasis (Table 6; Sah et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2017; Kim J.Y. et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2019; Imai et al., 2019). To that purpose, in all cases, researches induced the disease through the topical application of imiquimod (IMQ), except in the case of Yun-Sang et al. (Lee et al., 2017) where psoriasis was induced by intradermal injection of IL-23.

TABLE 6.

Preclinical in vivo studies of hMSCs used as advanced therapy for psoriasis in the last 5 years.

| Type of advanced therapy | Cells | Type of hMSC treatment evaluated | Animals | Disease models | Follow-up | References |

| Cell therapy and gene therapy | hUCB-MSCs | 1-hUCB-MSC group: 2 × 106 cells injected subcutaneously 24 h before and at day 6 of imiquimod application 2-hUCB-MSC-transduced group: 2 × 106 cells transduced with extracellular superoxide dismutase (SOD3) and injected subcutaneously 24 h before and at day 6 of imiquimod application 3-Control group: subcutaneous injections of an equal volume of phosphate-buffered saline at the same time points | – C57BL/6 mice | A mouse model of IMQ-induced psoriasis-like inflammation | 12 days | Sah et al., 2016 |

| Cell therapy | hUCB-MSCs | 1-hUCB-MSC group: 2 × 106 cells were injected subcutaneously on day 1 and 7 after induction of psoriasis-like skin 2-Control group: subcutaneous injections of an equal volume of phosphate-buffered saline at the same time points | – C57/BL6 male mice | IL-23-mediated psoriasis-like skin inflammation mouse model IMQ-induced psoriasis-like skin inflammation mouse model | 15 days | Lee et al., 2017 |

| hPT-MSCs | 1-hPT-MSC group: 106 cells via the mouse tail vein on days 1 and 3 of the imiquimod application period 2-Control group: Mice received an intravenous injection of an equal volume of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) via tail vein at the same time points | – Female C57BL/6 mice | IMQ-induced psoriasis-like skin inflammation mouse model | 7 days | Kim J.Y. et al., 2018 | |

| hA-MSCs | 1-hA-MSC group: 2 × 105 cells injected intravenously 2-Control group: mouse serum injected intravenously | – B6 mice | A mouse model of IMQ-induced psoriasis-like inflammation | 5 days | Imai et al., 2019 | |

| hUCB-MSCs | 1-hUCB-MSC group: 1 × 105 cells injected intravenously 2-Control group: phosphate-buffered saline injected intravenously | – Female BALB/c mice | A mouse model of IMQ-induced psoriasis-like inflammation | 13 days | Chen et al., 2019 |

Interestingly, one study combined CT with GT strategy (Sah et al., 2016) where 2 × 106 hUCB-MSCs injected subcutaneously were transduced with extracellular superoxide dismutase (SOD3) demonstrating that enhanced the immunomodulatory and antioxidant activities of hMSCs and therefore, prevented psoriasis development after 12 days of follow-up.

Rest of the reports studied hUCB-MSCs (Lee et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2019), palatine tonsil (hPT-MSCs) (Kim J.Y. et al., 2018) or hA-MSCs (Imai et al., 2019) as CT strategy for 10 ± 4.8 days. Studies which evaluated the use of hUCB-MSCs demonstrated that proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-17, and TNF-α were inhibited but IL-10 was significantly increased (Lee et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2019). Lee et al. (2017) injected subcutaneously 2 × 106 cells on days 1 and 7 after induction of psoriasis-like skin meanwhile, Chen et al. (2019) injected intravenously 1 × 105 cells, but in both cases, hUCB-MSCs did not only prevent but also treat psoriasis-like skin (Lee et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2019).

In the case where hPT-MSCs (106 cells) and hA-MSCs (2 × 105 cells) were applied, intravenous injection was the route of administration chosen and, in both cases, suppressed the development of psoriasis (Kim J.Y. et al., 2018; Imai et al., 2019).

On balance, results using hMSCs were better than control groups in all cases and two studies used the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI); demonstrating in both cases that after 7 to 8 days, PASI values were lower for hMSCs-treated groups (4.5) than non-treated groups (6.5) (Kim J.Y. et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2019).

Clinical Studies

Over the past 5 years, nine clinical studies have reported the use of hMSCs for the treatment of different types of psoriasis: psoriasis vulgaris (Chen et al., 2016; De Jesus et al., 2016) (NCT03765957), psoriatic arthritis (De Jesus et al., 2016), moderate to severe psoriasis (Comella et al., 2018) (NCT03265613, NCT03392311, and NCT04275024) and plaque psoriasis (Wang et al., 2020) (NCT02918123) (Table 7).

TABLE 7.

Clinical studies of hMSCs used as advanced therapy for psoriasis in the last 5 years.

| Type of advanced therapy | Cells | Type of clinical study | N (male/female) | Age (years)a | hMSC treatment | Safety (Treatment-related adverse events) | Indication | Effectivenessa | Follow-upa | References |

| Cell therapy | Allogeneic hUCB-MSCs | Case report | 2 (1/1) | 30.5 ± 6.4 | 1–3 infusions of hUCB-MSCs (106 cells/kg) | None | Psoriasis vulgaris | No symptoms of psoriatic relapse were observed | 4–5 years | Chen et al., 2016 |

| Autologous hAT-MSCs | Case report | 2 (1/1) | 43 ± 21.2 | 2–3 intravenous infusions of hAT MSCs at a dose of 0.5 –3.1 × 106 cells/kg | None | Psoriasis vulgaris (PV) and psoriatic arthritis (PA) | PASI changed from 21 to 9 and from 24 to 8.3 | 0.63 years | De Jesus et al., 2016 | |

| Autologous hAT-MSCs | Case report | 1 (1/0) | 43 | Intravenous injection of 3 – 6 × 107 hAT-MSCs in normal saline | None | Severe psoriasis | PASI score decreased from 50.4 to 0.3 | 1 year | Comella et al., 2018 | |

| Allogeneic hG-MSCs | Case report | 1 (1/0) | 19 | 5 bolus injections of hG-MSCs (3 × 106/kg/infusion) | None | Plaque psoriasis | After 3 years the disease was resolved | 3 years | Wang et al., 2020 | |

| Allogeneic hUCB-MSCs | Early Phase I clinical trial (Single Group Assignment- Open Label) | 12 | (18–65) | Different doses of hUCB-MSCs from 1.5 × 106 to 3 × 106 | – | Psoriasis vulgaris | – | 6 months | NCT03765957 (Clinical Research on Treatment of Psoriasis by Human Umbilical Cord-derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov)1 | |

| Allogeneic hAT-MSCs | Phase I/II Clinical Trial (Single Group Assignment- Open Label) | 7 | (18–65) | Intravenous injection of 5 × 105 cells/kg at week 0, week 4 and week 8 | – | Moderate to severe psoriasis | – | 12 weeks | NCT03265613 (Safety and Efficacy of Expanded Allogeneic AD-MSCs in Patients With Moderate to Severe Psoriasis – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov)4 | |

| Allogeneic hAT-MSCs | Phase I/II Clinical Trial (Single Group Assignment- Open Label) | 5 | Intravenous injection of 2 × 106 cells/kg at week 0, week 2, week 4, week 6 and week 8. In addition, calcipotriol ointment was topically applied twice daily | – | Moderate to severe psoriasis | – | 12 weeks | NCT03392311 (Efficacy and Safety of AD-MSCs Plus Calpocitriol Ointment in Patients With Moderate to Severe Psoriasis – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov)3 | ||

| Allogeneic hAT-MSCs | Clinical Trial (Single Group Assignment- Open Label) | 8 | (18–65) | Intravenous injection of 2 × 106 cells/kg at week 0, week 2, week 4, week 6 and week 8. In addition, oral PSORI-CM01 Granule plus calcipotriol ointment was topically applied twice daily | – | Moderate to severe psoriasis | – | 12 weeks | NCT04275024 (Efficacy and Safety of AD-MSCs Plus Calpocitriol Ointment and PSORI-CM01 Granule in Psoriasis Patients – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov)2 | |

| Allogeneic hUCB-MSCs | Phase I Clinical Trial (Single Group Assignment- Open Label) | 9 | (19–65) | Different doses of hUCB-MSCs from 5 × 107 to 2 × 108, subcutaneously injected | – | Moderate to severe plaque psoriasis | – | 144 weeks | NCT02918123 (Safety of FURESTEM-CD Inj. in Patients With Moderate to Severe Plaque-type Psoriasis – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov)5 |

aExpression of measures: mean ± standard deviation (range).

1Clinical Research on Treatment of Psoriasis by Human Umbilical Cord-derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov Available at: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03765957?term=mesenchymal+stem+cells&recrs=abdefgh&cond=Psoriasis&strd_s=01%2F01%2F2015&strd_e=12%2F31%2F2020&draw=2&rank=1 [Accessed January 13, 2021].

2Efficacy and Safety of AD-MSCs Plus Calpocitriol Ointment and PSORI-CM01 Granule in Psoriasis Patients – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov Available at: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04275024?term=mesenchymal+stem+cells&recrs=abdefgh&cond=Psoriasis&strd_s=01%2F01%2F2015&strd_e=12%2F31%2F2020&draw=1&rank=4 [Accessed January 21, 2021].

3Efficacy and Safety of AD-MSCs Plus Calpocitriol Ointment in Patients With Moderate to Severe Psoriasis – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov Available at: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03392311?term=mesenchymal+stem+cells&recrs=abdefgh&cond=Psoriasis&strd_s=01%2F01%2F2015&strd_e=12%2F31%2F2020&draw=1&rank=3 [Accessed January 21, 2021].

4Safety and Efficacy of Expanded Allogeneic AD-MSCs in Patients With Moderate to Severe Psoriasis – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov Available at: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03265613?term=mesenchymal+stem+cells&recrs=abdefgh&cond=Psoriasis&strd_s=01%2F01%2F2015&strd_e=12%2F31%2F2020&draw=2&rank=2 [Accessed January 21, 2021].

5Safety of FURESTEM-CD Inj. in Patients With Moderate to Severe Plaque-type Psoriasis – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov Available at: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02918123?term=mesenchymal+stem+cells&recrs=abdefgh&cond=Psoriasis&strd_s=01%2F01%2F2015&strd_e=12%2F31%2F2020&draw=1&rank=5 [Accessed January 21, 2021].

All studies applied CT strategies, two of them used autologous hAT-MSCs (De Jesus et al., 2016; Comella et al., 2018) and the others, evaluated the use of allogeneic cells from different sources: hUCB-MSCs (Chen et al., 2016) (NCT03765957, NCT02918123), hAT-MSCs (NCT03265613, NCT03392311, NCT04275024), and gingival mucosa MSCs (hG-MSCs) (Wang et al., 2020).

Results were reported in the four case reports analyzed (Chen et al., 2016; De Jesus et al., 2016; Comella et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2020) and despite of the fact that different hMSCs populations were used, adverse events were not observed in none of them.

Chen et al. (2016) evaluated the use of allogeneic hUCB-MSCs by 1–3 infusions (doses of 106 cells/kg) in 2 patients with psoriasis vulgaris. After a follow-up of 4–5 years no symptoms of psoriatic relapse were observed. Something similar occurred in the study of Wang et al. (2020) were hG-MSCs were administered by bolus injections (5 doses of 3 × 106/kg) in a patient with plaque psoriasis, demonstrating that after 3 years the disease was resolved.

In contrast, De Jesus et al. (2016) and Comella et al. (2018) applied autologous hAT-MSCs injected intravenously [2–3 doses of 0.5–3.1 × 106 cells/kg or a unique dose of 6 × 107 cells]. In the first case, significant improvement was noted in lesions of 2 patients with psoriasis vulgaris and psoriatic arthritis (PASI changed from 21 to 9 and from 24 to 8.3, respectively) and joint pain was reduced, meanwhile, in the second case, psoriasis area and severity PASI score decreased from 50.4 at baseline to 0.3 at 1-month follow-up (Comella et al., 2018).

Rest of studies reviewed were clinical trials, but no results have been posted yet. In these, allogeneic hAT-MSCs (3) or hUCB-MSCs (2) alone (NCT03765957, NCT03265613, and NCT02918123) or in combination with other treatments such as calcipotriol ointment (NCT033923119) or oral PSORI-CM01 Granule (NCT04275024) has been evaluated. Type of treatments varied from doses of 5 × 105 cells/kg to a unique injection of 2 × 108 cells and the preferred source of administration was intravenously although one study analyzed the application of subcutaneous injections (NCT02918123).

According to the investigations reviewed, at preclinical and clinical level, for the treatment of different types of psoriasis the best advanced therapy based on the use of hMSCs is cell therapy. Results in most of the cases demonstrated a decrease of the PASI values and in some patients, psoriasis disappeared. Considering the route of administration, intravenous injections are the most analyzed and the most promising hMSC populations are hAT-MSCs and hUCB-MSCs, although more research is required to standardize the dose and determine the autologous or allogeneic nature of the cells.

Atopic Dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis is a chronic inflammatory pruritic skin disease that affects a large number of children and adults (Akdis et al., 2006), although it can improve significantly, or even clear completely, in some children as they get older. The exact cause of atopic eczema is unknown, but the imbalance of Th2 to Th1 cytokines plays a crucial role (David Boothe et al., 2017).

Preclinical in vivo Studies

In the last 5 years, seven in vivo studies have reported the use of hMSCs as advanced therapy (Table 8; Kim et al., 2015, Kim J.M. et al., 2018; Shin et al., 2017; Sah et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2019; Park et al., 2019, Park H.H. et al., 2020). The disease model preferred to induce atopic dermatitis was the use of Dermatophagoides farina extract alone (Kim et al., 2015; Shin et al., 2017) or combined with other agents such as house dust mites (Park H.H. et al., 2020) and 4% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) (Lee et al., 2019). Other substances used were ovalbumin (Sah et al., 2018), acetone and 2, 4-dinitrochlorobenzene (DNCB): olive oil mixture (4:1 vol/vol) (Kim J.M. et al., 2018) and Aspergillus fumigatus extract (Park et al., 2019).

TABLE 8.

Preclinical in vivo and clinical studies of hMSCs used as advanced therapy for atopic dermatitis in the last 5 years.

| PRECLINICAL IN VIVO STUDIES | |||||||||||

| Type of advanced therapy | Cells | Type of hMSC treatment evaluated | Disease models | Follow-up | References | ||||||

| Cell therapy | hUCB-MSCs | 1-hUCB-MSCs group: 2 × 106 cells injected intravenously on days 2, 9, 16 and 23. 2-Muramyl dipeptide – hUCB-MSCs (intravenous) group: 2 × 106 injected intravenously on days 2, 9, 16 and 23 previous administration of muramyl dipeptide. 3-Muramyl dipeptide – hUCB-MSCs (subcutaneous) group: 2 × 106 injected subcutaneously on days 2, 9, 16 and 23 previous administration of muramyl dipeptide. | Dermatophagoides farinae-induced murine atopic dermatitis model | 30 days | Kim et al., 2015 | ||||||

| hAT-MSCs | 1-hAT-MSCs (low) group: 2 × 105 cells injected intravenously 2-hAT-MSCs (high) group: 2 × 106 cells injected intravenously 3-Fibroblasts group: Human dermal fibroblasts injected intravenously | Dermatophagoides farinae-induced murine atopic dermatitis model | 14 days | Shin et al., 2017 | |||||||

| hAT-MSCs | 1-hAT-MSCs group: 106 cells injected intravenously on days 0 and 11 2-Fibroblasts group: Human dermal fibroblasts injected intravenously | Acetone and 2, 4-dinitrochlorobenzene (DNCB): olive oil mixture (4:1 vol/vol) induced atopic dermatitis | 24 days | Kim J.M. et al., 2018 | |||||||

| hUCB-MSCs | 1-hUCB-MSCs group: subcutaneous administration of 106 cells 2-MC-hUCB-MSCs primed group: subcutaneous administration of 106 cells primed with mast cells granules 3-Fibroblasts group: subcutaneous administration of 106 cells | 4% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and Dermatophagoides farinae extract induced atopic dermatitis | 14 days | Lee et al., 2019 | |||||||

| hWJ-MSCs | 1-hWJ-MSCs group: subcutaneous administration of 2 × 106 cells 2-hWJ-MSCs-poly I:C group: subcutaneous administration of 2 × 106 cells primed with poly I:C 3-hWJ-MSCs- IFN-γ group: subcutaneous administration of 2 × 106 cells primed with IFN-γ | Aspergillus fumigatus extract to induce atopic dermatitis | 5 days | Park et al., 2019 | |||||||

| Cell therapy and gene therapy | hUCB-MSCs | 1-hUCB-MSCs group: 2 × 106 cells injected subcutaneous on day 20, 28 and 42 and one time on day 56 after the development of atopic dermatitis 2-hUCB-MSCs transduced group: 2 × 106 superoxide dismutase 3 (SOD3) transduced cells injected subcutaneous on day 20, 28 and 42 and one time on day 56 after the development of atopic dermatitis | Ovalbumin – atopic dermatitis induced mouse model | 56 days | Sah et al., 2018 | ||||||