Abstract

Uterine artery arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) are rare anomalies that may result in uterine hemorrhage. A 40-year-old G8P5126 woman presented with severe vaginal bleeding and an estimated 2000 mL of blood loss at home. Three weeks prior, she had a vaginal delivery of a term infant resulting in post-partum hemorrhage, with 2700 mL of blood loss. The patient had a history of ectopic pregnancy, placenta previa, and dilatation and curettage. Interventional radiology was consulted, and the patient underwent angiography of the internal iliac and uterine arteries revealing the presence of a uterine AVM, which was successfully embolized using a thick mixture of n-butyl cyanoacrylate and lipiodol. The patient experienced no further episodes of bleeding and was discharged within 24 hours. Recognition of typical symptoms and risk factors for uterine arteriovenous malformations can facilitate early diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

Keywords: Arteriovenous malformation, Postpartum hemorrhage, Embolization, Arteriogram

Introduction

Postpartum hemorrhage is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in women. Although rare, the presence of a uterine arteriovenous malformation (AVM) is a treatable cause of severe hemorrhage. While angiography is the gold standard for the diagnosis of uterine AVM, diagnosis can also be made non-invasively utilizing Doppler ultrasonography. Uterine artery embolization is the treatment of choice, though hysterectomy is also an effective, though more invasive method of treatment [1]. A variety of embolic agents have been utilized to effectively treat uterine AVMs in a minimally invasive fashion. Procedures involving uterine instrumentation are being performed more frequently, and thus the prevalence of uterine AVMs may increase in the future [1,2].

Case Report

A 40-year-old G8P5126 female had spontaneous vaginal delivery of a term infant that was complicated by 2700mL of acute blood loss, requiring the transfusion of four units of packed red blood cells. The pregnancy had been complicated by placenta previa on her second trimester anatomy scan, but this was shown to have resolved by the third trimester. The hemorrhage was controlled with uterotonics and the placement of a Bakri balloon. She stabilized and was discharged home on postpartum day two. Her past medical history was significant for postpartum hemorrhage due to uterine atony after her first delivery, placenta previa during her third pregnancy, a fifth ectopic pregnancy requiring surgery, and a seventh pregnancy resulting in a spontaneous abortion requiring dilatation and curettage.

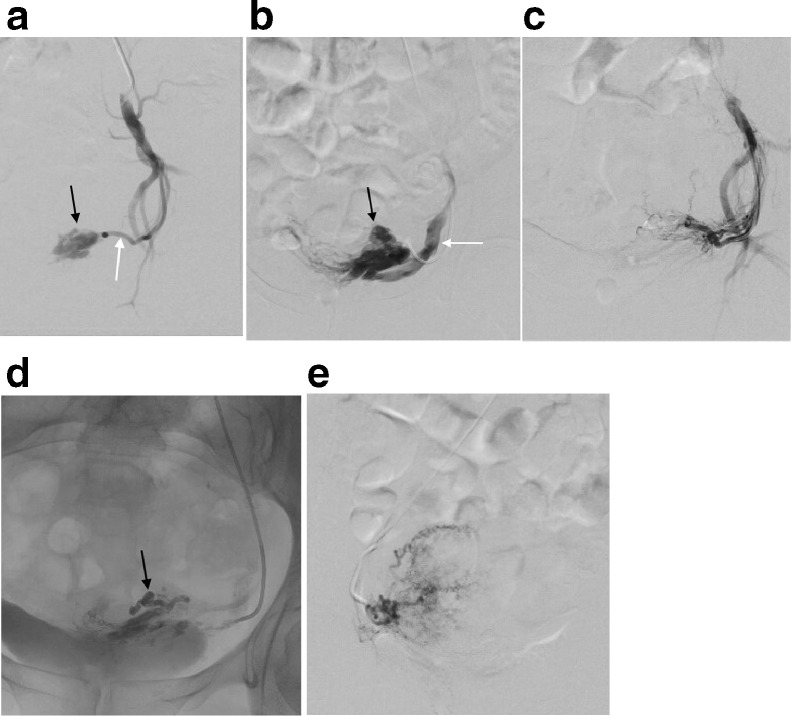

Three weeks later, the patient presented to the emergency department after experiencing severe vaginal bleeding and passing large clots. Her hemoglobin dropped from 12 g/dL to 10 g/dL and it was estimated that she had blood loss of approximately 2000mL at home. The interventional radiology service was consulted for consideration of uterine artery embolization. Via radial arterial access, a left internal iliac arteriogram was performed, revealing an enlarged, tortuous left uterine artery, a tangle of vessels representing a nidus, and early opacification of the internal iliac vein, compatible with uterine arteriovenous malformation (uterine AVM) (Fig. 1a, b). The decision was made to perform embolization of the uterine AVM, with obliteration of the nidus. Given the brisk blood flow through the AVM and desire to permanently fill and obliterate the AVM nidus, a thick glue mixture was utilized for embolization via a microcatheter placed in the left uterine artery. The mixture was composed of lipiodol (Guerbet, Villepinte, France) mixed with n-butyl cyanoacrylate (Histoacryl, B. Braun, Melsungen, Germany) in a 3:1 ratio. This allowed for complete filling of the nidus of the malformation, with resolution of early venous drainage and brisk shunting, confirmed by repeat arteriogram from the left uterine artery (Fig. 1c, d). Minimal if any of the thick glue mixture progressed into the internal iliac vein. An arteriogram of the right uterine artery was then performed, which did not reveal any filling of the uterine AVM or other discrete abnormality (Fig. 1e). The right uterine artery was empirically embolized using 500-700 µm nonabsorbable particles (Embosphere, Merit Medical, South Jordan, Utah, US), with stasis of blood flow within the right uterine artery confirmed on repeat angiography of the uterine artery. The patient experienced no further episodes of vaginal bleeding, and she was discharged to her home the next day. At her outpatient follow up appointment two weeks later, she did not report any further episodes of bleeding. The originally planned hysterectomy was cancelled. No further intervention was required.

Fig. 1.

(a) Left internal iliac arteriogram demonstrating a nidus of blood vessels (black arrow) arising from the left uterine artery (white arrow). (b) Arteriogram of the left uterine artery demonstrates the vascular nidus of the uterine AVM (black arrow) with early opacification of the left internal iliac vein (white arrow). (c) Following glue embolization of the uterine AVM, left uterine arteriogram demonstrates absence of opacification of the nidus. There is no early opacification of the left internal iliac vein. (d) Spot radiograph following embolization demonstrates the cast of glue within the nidus of the uterine AVM. € Arteriogram of the right uterine artery demonstrates normal postpartum appearance of the uterine arteries without visible supply to the uterine AVM. The right uterine artery was empirically embolized using particles.

Discussion

Arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) are abnormalities of the vascular system that consist of a tangle of abnormal blood vessels forming a nidus that allows for an abnormal, brisk communication between arteries and veins. Uterine AVMs are rarely encountered, with just over one-hundred reported cases [1]. Uterine AVMs typically present with symptoms such as menorrhagia, postpartum hemorrhage, and spontaneous abortions [3].

There are two types of uterine AVMs. Primary, or idiopathic, uterine AVMs are congenital developmental abnormalities. Secondary, or acquired, uterine AVMs are caused by reactive angiogenesis, pregnancy related changes, uterine procedures, or trophoblastic invasion [4]. Uterine instrumentation, such as dilatation and curettage or surgery, is considered one of the main causes of acquired uterine AVMs, since they cause inflammation and reactive angiogenesis [4]. An increase in uterine instrumentation and cesarean sections in recent years may lead to an increased incidence of uterine AVMs [1,2]. Diseases associated with the formation of uterine AVMs include endometrial carcinoma, cervical carcinoma, and trophoblastic disease [4].

The diagnosis of uterine AVM is typically made during angiography as part of a uterine artery embolization procedure for treatment of hemorrhage [1]. However, if a patient presents with the symptoms above, color Doppler ultrasonography could confirm the diagnosis of a uterine AVM noninvasively [5]. The use of ultrasound also allows the physician to evaluate for other entities that may cause similar symptoms, such as uterine fibroids, cancer, or endometrial hyperplasia. The gold standard for diagnosis remains digital subtraction angiography of the uterine arteries due to its ability to identify the nidus of blood vessels and evaluate the size and flow of the arteriovenous shunt associated with the AVM [1]. For larger AVMs, CT angiography or MR angiography may be used to examine the full extent of the AVM for preprocedure planning [5].

Prior to the 1990s, the primary approach to treating uterine artery AVMs was with hysterectomy. Patients typically presented with bleeding, and the uterine AVM was diagnosed intraoperatively or with postoperative pathology. Today, uterine artery embolization (UAE) is the gold standard for treatment [4]. Trans-arterial embolization is a minimally invasive technique that can quickly control even catastrophic hemorrhage and effectively treat the lesion, while preserving the uterus. A variety of embolic agents can be utilized for this minimally invasive treatment, including particles, Gelfoam, and liquid embolic agents. The type of embolic agent chosen by the interventional radiologist performing the procedure varies, and depends on the size and flow rate of the shunt, as well as operator comfort and experience level with the different agents. Gelfoam is typically reabsorbed by the body in 10-14 days and can maintain fertility in reproductive age women [6]. A retrospective analysis published in 2014 examined a decade's worth of UAE procedures and identified 19 that were performed for acquired uterine AVMs. All 19 patients underwent bilateral UAE with Gelfoam, and 17 had successful resolution of the AVM following the procedure. Of the remaining 2, 1 had residual feeders into the AVM, but overall decreased flow, leading to the eventual regression of the AVM over 5 months. The second patient experienced uterine artery rupture requiring re-embolization. Embolization of the bilateral uterine arteries should be the preferred approach, since uterine AVMs most likely have feeding vessels arising from both sides [4].

In the case presented, the patient had a history of remote uterine instrumentation, spontaneous abortions, and both acute and delayed postpartum hemorrhage, making the presence of a uterine AVM more likely. She was diagnosed with placenta previa during her second trimester, and it is possible that the uterine artery AVM was seen on ultrasound at the time and mistaken for this. Her presentation of acute menorrhagia immediately after delivery and delayed recurrence of severe menorrhagia lead to her diagnosis using conventional angiography. Thick glue (n-butyl cyanoacrylate mixed with lipiodol) was chosen as the embolic agent because of the large nidus and brisk blood flow through the malformation. Glue is a permanent embolic agent, offering a durable treatment, which was important given the degree of hemorrhage that she had experienced. The contralateral uterine artery was embolized with particles to address any additional arteries that may have been supplying the malformation. The patient did not desire future fertility, which also influenced the choice to use these permanent embolic agents. This case report illustrates classic imaging findings of an acquired uterine AVM following uterine instrumentation resulting in severe delayed post-partum hemorrhage. Early recognition of this rare entity may facilitate prompt diagnosis and treatment with transarterial embolization, reducing risk related to recurrent hemorrhage and sparing these patients from hysterectomy.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient/patient's representative for publication of this case report.

Footnotes

Disclosures: No financial disclosures.

References

- 1.Grivell R.M., Reid K.M., Mellor A. Uterine arteriovenous malformations: a review of the current literature. Obstetr Gynecol Surv. 2005;60(11):761–767. doi: 10.1097/01.ogx.0000183684.67656.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosen Todd. Placenta accreta and cesarean scar pregnancy: overlooked costa of rising cesaren section rate. Clin Perinatol. 2008;35:519–529. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fleming H., Ostör A.G., Pickel H., Fortune D.W. Arteriovenous malformations of the Uterus. Obstetr Gynocol. 1989;72(2):209–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim T., Shin J.H., Kim J., Yoon H.K., Ko G.Y., Gwon D.I. Management of bleeding uterine arteriovenous malformation with bilateral uterine artery embolization. Yonsei Med J. 2014;55(2):367–373. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2014.55.2.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shim D.J., Choi S.J., Jung J.M., Choi J.H. Uterine arteriovenous malformation with repeated vaginal bleeding after dilation and curettage. Obstetr Gynecol Sci. 2019;62(2):142–145. doi: 10.5468/ogs.2019.62.2.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vilos A.G., Vilos G.A, Hollet-Caines J., Rajakumar C., Garvin G., Kozak R. Uterine artery embolization for uterine arteriovenous malformation in five women desiring fertility: pregnancy outcomes. Human Reprod. 2015;30(7):1599–1605. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]