Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To assess whether previously observed brain and cognitive differences between children with type 1 diabetes and control subjects without diabetes persist, worsen, or improve as children grow into puberty and whether differences are associated with hyperglycemia.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

One hundred forty-four children with type 1 diabetes and 72 age-matched control subjects without diabetes (mean ± SD age at baseline 7.0 ± 1.7 years, 46% female) had unsedated MRI and cognitive testing up to four times over 6.4 ± 0.4 (range 5.3–7.8) years; HbA1c and continuous glucose monitoring were done quarterly. FreeSurfer-derived brain volumes and cognitive metrics assessed longitudinally were compared between groups using mixed-effects models at 6, 8, 10, and 12 years. Correlations with glycemia were performed.

RESULTS

Total brain, gray, and white matter volumes and full-scale and verbal intelligence quotients (IQs) were lower in the diabetes group at 6, 8, 10, and 12 years, with estimated group differences in full-scale IQ of −4.15, −3.81, −3.46, and −3.11, respectively (P < 0.05), and total brain volume differences of −15,410, −21,159, −25,548, and −28,577 mm3 at 6, 8, 10, and 12 years, respectively (P < 0.05). Differences at baseline persisted or increased over time, and brain volumes and cognitive scores negatively correlated with a life-long HbA1c index and higher sensor glucose in diabetes.

CONCLUSIONS

Detectable changes in brain volumes and cognitive scores persist over time in children with early-onset type 1 diabetes followed longitudinally; these differences are associated with metrics of hyperglycemia. Whether these changes can be reversed with scrupulous diabetes control requires further study. These longitudinal data support the hypothesis that the brain is a target of diabetes complications in young children.

Introduction

A growing body of evidence suggests that the brain is a target for diabetes complications. Reduced total, gray, and white matter volumes have been observed in type 1 diabetes (1), particularly in temporal and parieto-occipital regions (2). Regional brain differences have also been linked to severe hypoglycemia, higher lifetime HbA1c, disease duration, and severity of microangiopathy (2,3). Within a younger type 1 diabetes cohort (mean age 12.6 years), Perantie and colleagues (4,5) found that greater lifetime hyperglycemia was associated with decreased total gray and white matter volume in the occipital lobe. Although previous studies in older children and adults with type 1 diabetes have suggested that effects of hyper- and hypoglycemic exposure on brain structure are widely distributed, frontal and parietal-occipital cortical regions appear most vulnerable, particularly in individuals with early disease onset.

The human brain undergoes unique dynamic structural and functional changes during childhood and requires continuous delivery of glucose for brain function and growth (6). Whether dysglycemia in young children irreversibly compromises key neurodevelopmental processes is unknown. To address this question, our Diabetes Research in Children Network (DirecNet), a five-center National Institutes of Health–funded consortium, conducted structural and diffusion-weighted imaging studies in very young children with type 1 diabetes (aged 4 to <10 years at study entry) and in a group of age-matched control subjects without diabetes originally recruited >8 years ago. Unsedated structural brain MRIs as well as age-appropriate cognitive testing were performed; the diabetes group also had continuous glucose monitoring (CGM). Results from the first two time points over 18 months showed significant cross-sectional and longitudinal anatomical differences between our diabetes and control cohorts as demonstrated by volumetric and voxel-based morphometric methods and by diffusion tensor imaging (7–12). Subtle differences in specific cognitive domains compared with age-matched control subjects without diabetes were also detected (13,14). Moreover, in children with diabetes, there was slower growth of the hippocampus, which was associated with hyperglycemia and greater glycemic variability (15); differences in trajectories of brain growth in those with early severe diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) were also observed (16).

Remarkably, the biggest association of these reported differences has been with measures of hyperglycemia, as reflected by HbA1c and percent sensor glucose (% sensor glucose) above target as detected by CGM (7–16). Vulnerable brain areas in type 1 diabetes appear particularly localized to frontoparietal networks as well as components of networks involved in the processing of complex sensory information, sensorimotor function, and cognition. These results highlight the importance of longitudinal studies of brain growth in early-onset type 1 diabetes. We designed these new studies to determine whether abnormalities in total and regional gray and white matter volumes and white matter microstructure persist or worsen over longitudinal follow-up and whether these changes are associated with measures of glycemic control and neurocognitive metrics as children with type 1 diabetes grow and progress into puberty. We hypothesized that observed changes in the specific brain regions noted above would persist or worsen over time in children with type 1 diabetes, eventually negatively affecting cognition.

Research Design and Methods

Studies were approved by the institutional review boards (IRBs) of each of the five participating DirecNet centers, including Nemours Children’s Health System Jacksonville (IRB #588973), Stanford University (IRB #32179), University of Iowa (IRB #201501830), Washington University in St. Louis (IRB #201411074), and Yale University (IRB #1411014935), and by the study’s data safety monitoring board. Informed written consent from the parents/guardians and child assent were obtained as appropriate. Children with type 1 diabetes (n = 144) on insulin therapy for at least 1 month, ages 4–9 years at study onset, were recruited. At enrollment, participants were on stable insulin therapy and had no history of prematurity, other chronic illnesses, seizures, developmental delay, or psychiatric diagnosis. Participants were not excluded from the study if they developed any other conditions after enrollment. A group of 72 healthy, age-matched control subjects without diabetes and with similar inclusion/exclusion criteria was recruited. Siblings of children with diabetes were included if they had normal fasting glucose, HbA1c, and negative diabetes autoantibodies. All subjects had clinical and glycemic assessments, structural brain MRI, and neurocognitive testing performed at baseline. CGM and HbA1c data were obtained quarterly in the diabetes group, and cognitive and brain MRI were repeated after 18 months in all. All study subjects had a full physical examination and pubertal assessment done according to the standards of Tanner for breasts (females), genitalia (males), and pubic hair (both). Height was measured using a wall-mounted stadiometer, and weight was measured using a digital scale with light clothing. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data were used for percentiles and SDS. After securing renewal of grant funding, the initial cohorts of children were re-recruited whenever possible and studied again a third time for an average of 2.9 years (range 1.8–4.3 years) from the last assessment and again 2 years later for up to four separate evaluations. Subjects unable to complete the studies were replaced with new subjects matched for age, sex, HbA1c, and duration of diabetes who met the same inclusion/exclusion criteria.

MRI

Unsedated brain MRIs were performed using a desensitization protocol to minimize children’s movement, with excellent success as described (17). All sites used a Siemens 3T MAGNETOM Trio whole-body MRI, a standard 12-channel head coil, and an identical imaging protocol. Washington University in St. Louis transitioned to a Siemens Prisma scanner for the last 14 subjects in the trial; scan pulse sequences were designed and tested to be backwardly compatible. Within- and between-site calibrations were performed scanning the same adult phantoms on every machine across all sites (9). Sagittal T1 brain images were acquired using a magnetization-prepared rapid gradient-echo pulse sequence. Blood glucose was targeted between 70 and <300 mg/dL within 60 min before all scans and cognitive assessments. Cortical reconstruction and volumetric segmentation were performed with the FreeSurfer version 6.0 image analysis suite (https://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu), which calculates total gray and white matter volume of the cerebral cortex.

Neurocognitive Testing

In the context of a larger neurocognitive battery, all subjects completed age-appropriate intellectual testing (Wechsler Intelligence Scale). One parent per subject completed an abbreviated intelligence quotient (IQ) measure used as a covariate in the analysis. Tests were double scored at a centralized location (Nemours).

Glycemic Assessments

HbA1c was measured using a DCA 2000. All available HbA1c results since diagnosis of diabetes were collected, and a lifelong measure of dysglycemia was calculated using an HbA1c index (HbA1c area under the curve [AUC] >6%) that computed total AUC >6.0% using the trapezoidal rule divided by time between diagnosis and study assessment (10). Children with diabetes wore a blinded Medtronic IPro2 CGM quarterly during follow-up, including for 3–6 days within 4 weeks of the imaging and cognitive procedures; participants using Dexcom G5 or G6 clinically were allowed to use those instead. Severe hypoglycemia was defined as an episode where blood glucose was low (<40 mg/dL) with loss or near loss of consciousness or where function/cognition was impaired enough to need the assistance of others, the use of glucagon, or an emergency department visit.

Statistical Analysis

Statistics of demographic/metabolic variables are provided in Table 1. A sample size of 216 participants (144 with type 1 diabetes and 72 control subjects) was estimated to be sufficient to detect medium effects on the basis of univariate group comparison analysis. CGM sensor glucose data were analyzed by the Jaeb Center for Health Research (Tampa, FL); summary sensor data included mean, SD, percent on target (70 to <180 mg/dL), and percent >180, >250, <70, and <60 mg/dL.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of study subjects

| Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 3 | Time 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes (n = 144) | Control (n = 72) | Diabetes (n = 144) | Control (n = 70) | Diabetes (n = 144) | Control (n = 70) | Diabetes (n = 137) | Control (n = 66) | |

| Age (years) | 7.0 ± 1.7 | 7.0 ± 1.8 | 8.5 ± 1.7 | 8.5 ± 1.8 | 11.2 ± 1.9 | 11.6 ± 1.7 | 13.2 ± 1.9 | 13.6 ± 1.7 |

| Range | 4.0–10.0 | 4.1–10.0 | 5.4–11.5 | 5.6–11.5 | 7.4–14.4 | 7.5–14.8 | 9.5–16.4 | 9.6–16.8 |

| Female sex | 66 (46) | 34 (47) | 66 (46) | 33 (47) | 61 (42) | 34 (49) | 58 (42) | 33 (50) |

| Race/ethnicity* | ||||||||

| White | 117 (81) | 59 (82) | 117 (81) | 58 (83) | 120 (83) | 62 (89) | 115 (84) | 58 (88) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 10 (7) | 4 (6) | 10 (7) | 4 (6) | 10 (7) | 3 (4) | 9 (7) | 3 (5) |

| African American | 6 (4) | 4 (6) | 6 (4) | 4 (6) | 6 (4) | 3 (4) | 5 (4) | 3 (5) |

| Asian | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Other | 9 (6) | 2 (3) | 9 (6) | 2 (3) | 7 (5) | 1 (1) | 7 (5) | 1 (2) |

| Height (cm) | 121.9 ± 11.8 | 121.7 ± 11.5 | 130.4 ± 11.7 | 131.4 ± 11.2 | 147.1 ± 13.1 | 150.3 ± 12.4 | 158.4 ± 12.2 | 160.9 ± 12.2 |

| BMI percentile | ||||||||

| Median (25th, 75th) | 71.8 (58.9, 86.1) | 60.8 (34.5, 79.9) | 69.3 (52.3, 84.7) | 63.1 (33.3, 81.1) | 67.2 (47.7, 83.9) | 61.2 (34.0, 91.3) | 72.5 (44.7, 85.8) | 63.8 (41.0, 90.4) |

| Range | 4–99 | 4–99 | 10–96 | 0–99 | 7–99 | 1–100 | 2–100 | 0–100 |

| Breast Tanner stage (girls), % | ||||||||

| I | 100 | 100 | 91 | 91 | 38 | 27 | 12 | 12 |

| II–III | 0 | 0 | 9 | 9 | 41 | 44 | 14 | 27 |

| IV–V | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 21 | 29 | 72 | 61 |

| Genital Tanner stage (boys), % | ||||||||

| I | 100 | 100 | 91 | 91 | 58 | 44 | 24 | 24 |

| II–III | 0 | 0 | 9 | 9 | 31 | 36 | 32 | 27 |

| IV–V | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 19 | 38 | 49 |

| HbA1c | ||||||||

| % | 7.9 ± 0.9 | 5.2 ± 0.2 | 7.9 ± 0.9 | 5.2 ± 0.3 | 8.1 ± 1.0 | 5.3 ± 0.2 | 8.3 ± 1.3 | 5.4 ± 0.3† |

| Range | 6.3–10.2 | 4.7–5.8 | 6.0–10.8 | 4.6–5.8 | 5.6–10.9 | 4.6–5.9 | 5.5–13.9 | 4.8–6.1 |

| mmol/mol | 62 ± 12 | 34 ± 9 | 62 ± 15 | 33 ± 3 | 64 ± 12 | 34 ± 3 | 67 ± 14 | 35 ± 3 |

| Diabetes duration (years) | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||||

| Median (25th, 75th) | 2.4 (1.1, 4.4) | 3.9 (2.6, 5.8) | 6.4 (4.8, 8.6) | 8.5 (7.1, 10.8) | ||||

| Range | 0.1–7.9 | 1.5–9.5 | 0.9–11 | 3.4–13.7 | ||||

| Age at onset (years) | 4.1 ± 1.9 | NA | 4.1 ± 1.9 | NA | 4.5 ± 2.1 | NA | 4.4 ± 2.1 | NA |

| Range | 0.9–8.5 | 0.9–8.5 | 0.9–11.0 | 0.9–11.0 | ||||

| HbA1c AUC >6%‡ | 2.1 ± 0.7 | NA | 2.1 ± 0.7 | NA | 1.9 ± 0.7 | NA | 2.0 ± 0.7 | NA |

| Insulin dose (units/kg/day) | 0.7 ± 0.2 | NA | 0.8 ± 0.2 | NA | 0.9 ± 0.2 | NA | 0.96 ± 0.25 | NA |

| Pump users, % | 55 | NA | 72 | NA | 72 | NA | 79 | NA |

| Severe hypoglycemia history& | 24 (17) | NA | 28 (19) | NA | 22 (15) | NA | 25 (18) | NA |

| DKA history& | 51 (35) | NA | 52 (36) | NA | 46 (32) | NA | 48 (35) | NA |

| Sensor glucose (mg/dL) | 194 ± 37 | NA | 192 ± 33 | NA | 195 ± 40 | NA | 195 ± 35 | NA |

| % Glucose | ||||||||

| 70–180 | 45.8 ± 15.7 | NA | 45.1 ± 13.8 | NA | 43.8 ± 16.6 | NA | 44.7 ± 14.0 | NA |

| >180 | 49.6 ± 17.1 | 49.1 ± 15.4 | 50.6 ± 18.9 | 50.6 ± 16.2 | ||||

| >250 | 26.1 ± 15.3 | 25.5 ± 13.8 | 26.5 ± 16.1 | 25.6 ± 15.2 | ||||

| <70 | 4.6 ± 5.5 | 5.8 ± 5.7 | 5.6 ± 5.4 | 4.7 ± 5.2 | ||||

| <60 | 2.6 ± 4.3 | 3.5 ± 4.6 | 3.2 ± 3.7 | 2.5 ± 3.3 | ||||

| Parent education level | ||||||||

| <12th grade | 3 (2) | 3 (4) | 3 (2) | 3 (4) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| 12th grade | 28 (19) | 9 (13) | 28 (19) | 9 (13) | 23 (16) | 6 (9) | 22 (16) | 5 (8) |

| Associate | 27 (19) | 6 (9) | 27 (19) | 6 (9) | 29 (20) | 10 (14) | 29 (21) | 9 (14) |

| Bachelor’s | 48 (33) | 21 (30) | 48 (33) | 21 (30) | 48 (33) | 23 (33) | 46 (34) | 23 (35) |

| Master’s | 29 (20) | 18 (26) | 29 (20) | 18 (26) | 33 (23) | 18 (26) | 30 (22) | 17 (26) |

| Doctoral | 7 (5) | 4 (6) | 7 (5) | 4 (6) | 7 (5) | 9 (13) | 6 (4) | 8 (12) |

Data are mean ± SD or n (%) unless otherwise indicated. NA, not applicable.

The sum of percentages <100% in a category is due to missing data (e.g., race/ethnicity, education level).

One control subject who had done the study from the inception had an HbA1c of 6.1% at time 4, despite normal and postprandial glucoses and negative diabetes autoantibodies.

Average excess glucose since diagnosis, where excess glucose is HbA1c >6% integrated with trapezoidal rule across visits. Calculated as cumulative lifetime excess glucose divided by diabetes duration.

The numbers at each time 1–4 refer to the episodes since diagnosis.

Our primary analysis used longitudinal mixed-effects modeling, treating individual age at four assessment points using maximum likelihood estimation implemented in Mplus version 8, an advanced latent modeling program (https://www.statmodel.com/download/usersguide/MplusUserGuideVer_8.pdf). We used all available subjects, including 57 replacement subjects recruited at time 3 as long as they had at least one outcome measure; 271 individuals (181 with type 1 diabetes, 90 control subjects) were included in the longitudinal analyses. We assumed data were missing at random, a well-accepted practical approach in modern longitudinal analysis. Neurocognitive and brain outcomes were measured four times; CGM outcomes were measured up to 16 times. We allowed individual variations of when participants joined the study, where they started (random intercept) in terms of key outcome variables, and how they changed (random slope) as they aged. Mixed-effects modeling results were converted to group differences (diabetes vs. control) and correlations between outcomes assessed at ages 6, 8, 10, and 12 years. Neurocognitive test analyses were adjusted on parent IQ and assumed a linear longitudinal trend. For brain measures, we allowed a nonlinear (quadratic) longitudinal trend and conducted analyses conditional on sex. Correlations across domains (neurocognitive, brain imaging, glycemic) were based on longitudinal mixed-effects modeling using simultaneous longitudinal developments of different outcomes allowing for their correlations through random effects. Significance level (α = 0.05, two-tailed) was used in all analyses without correcting for multiple comparisons.

Results

Two hundred sixteen children were initially recruited (144 with type 1 diabetes, 72 control subjects); all but 2 in the control group returned for the 18-month assessments (10,11). Of these subjects, 74% were re-recruited and returned for a third assessment (107 diabetes, 50 control), and 57 children (37 diabetes, 20 control) were recruited as replacements; 95% of those studied at time 3 (137 diabetes, 66 control) returned for the fourth assessment 2 years later (Supplementary Fig. 1). Clinical characteristics are included in Table 1. There were 11 subjects diagnosed with asthma. Over the course of the study follow-up, we had nine subjects with thyroiditis who were on stable thyroid replacement; six had celiac disease. Two patients also reported issues related to anxiety and depression, and one subject had suicidal ideation. A few of the study subjects in both groups were diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder by their primary care providers across the span of the study (time 1: two diabetes; time 2: two diabetes; time 3: four diabetes, five control; time 4: two diabetes, one control).

Primary Cognitive and Structural Brain Outcomes

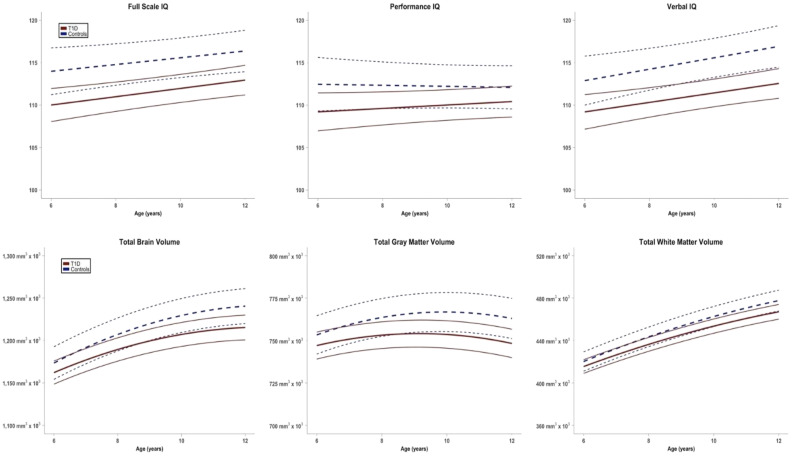

Full-scale IQ (FSIQ), performance IQ (PIQ), and verbal IQ (VIQ) showed significantly lower scores in the diabetes group than in the control group (Table 2 and Fig. 1). Widening or narrowing of group differences from age 6 to 12 years was not significant in any of the three neurocognitive measures, with the estimate of change in group differences from age 6 to 12 years of 1.04, 2.02, and −0.21 for FSIQ, PIQ, and VIQ, respectively (not statistically significant). Mean blood glucose was comparable among time points before the cognitive studies (188 ± 67, 202 ± 62, 200 ± 63, 185 ± 55 mg/dL for times 1–4, respectively). Glucose values were also comparable postcognitive studies (data not shown). Secondary analysis of the cognitive subscores is shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Table 2.

Differences in structural and cognitive metrics between diabetes and control groups estimated on the basis of longitudinal mixed-effects modeling

| Primary outcome | Group difference at age 6 years | Group difference at age 8 years | Group difference at age 10 years | Group difference at age 12 years | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est. | 95% CI | ES* | P value | Est. | 95% CI | ES* | P value | Est. | 95% CI | ES* | P value | Est. | 95% CI | ES* | P value | |

| Neurocognitive | ||||||||||||||||

| FSIQ | −4.15 | (−7.39, −0.92) | −0.31 | 0.012 | −3.81 | (−6.68, −0.93) | −0.32 | 0.009 | −3.46 | (−6.21, −0.70) | −0.30 | 0.014 | −3.11 | (−6.02, −0.20) | −0.26 | 0.036 |

| PIQ | −3.37 | (−7.24, 0.51) | −0.21 | 0.089 | −2.70 | (−6.03, 0.63) | −0.20 | 0.113 | −2.02 | (−5.04, 1.00) | −0.16 | 0.189 | −1.35 | (−4.38, 1.67) | −0.11 | 0.381 |

| VIQ | −3.83 | (−7.06, −0.60) | −0.29 | 0.020 | −3.90 | (−6.73, −1.06) | −0.33 | 0.007 | −3.97 | (−6.72, −1.22) | −0.35 | 0.005 | −4.04 | (−7.04, −1.03) | −0.32 | 0.008 |

| Structural MRI | ||||||||||||||||

| Total brain volume (mm3) | −15,410 | (−35,703, 4,883) | −0.18 | 0.137 | −21,159 | (−41,807, −511) | −0.24 | 0.045 | −25,548 | (−46,805, −4,291) | −0.29 | 0.018 | −28,577 | (−50,249, −6,906) | −0.32 | 0.010 |

| Gray matter (mm3) | −8,604 | (−20,711, 3,504) | −0.17 | 0.164 | −11,869 | (−23,883, 145) | −0.24 | 0.053 | −14,375 | (−26,730, −2,021) | −0.28 | 0.023 | −16,123 | (−28,662, −3,584) | −0.31 | 0.012 |

| White matter (mm3) | −6,426 | (−15,986, 3,133) | −0.16 | 0.188 | −8,486 | (−18,339, 1,367) | −0.21 | 0.091 | −10,430 | (−20,724, −136) | −0.24 | 0.047 | −12,259 | (−22,877, −1,640) | −0.28 | 0.024 |

ES, effect size; Est., estimated.

ES (Cohen d) were approximately calculated as 2 × t value / square root of (sample size − 1), where t values were calculated as point estimates of the group difference from mixed-effects modeling divided by their robust maximum likelihood SEs.

Figure 1.

Trajectory of changes in FSIQ, PIQ, VIQ, total brain volume, total gray matter volume, and total white matter volume in children with type 1 diabetes followed longitudinally compared to control subjects. T1D, type 1 diabetes.

Using FreeSurfer brain structural analysis, total, gray, and white matter volumes were not significantly different at baseline, but over time, group differences in brain structure became apparent, with lesser volume in the diabetes group. Differences were more pronounced as children got older, with significant widening of group differences from age 6 to 12 years in all structural measures (estimate of change in group differences from age 6 to 12 years for total brain volume −13,167 mm3 [P = 0.001], gray matter −7,519 mm3 [P = 0.029], white matter −5,833 mm3 [P = 0.007]) (Table 2 and Fig. 1). Mean blood glucose was comparable among time points before the MRI studies (185 ± 63, 176 ± 62, 175 ± 58, 184 ± 59 mg/dL for times 1–4, respectively). Glucose values were also comparable post-MRI studies (data not shown).

We conducted multivariate t tests to examine whether the original and replacement samples were different at times 3 and 4. The results showed no significant differences between the two in any of the cognitive and structural outcomes. To examine the sensitivity of our longitudinal analysis results to the replacement status, we repeated linear mixed-effects modeling of key outcome measures conditional on the replacement status. In these new analyses, the replacement status is modeled as a predictor of all growth parameters (intercept, linear slope, quadratic slope). We did not find any significant effect of the replacement status on growth parameters in any of our key cognitive and structural outcomes (Supplementary Table 2).

Association Between Brain and Neurocognitive Scores: Secondary Outcomes

Several significant positive correlations were found between total, gray, and white matter volumes (measured using FreeSurfer analysis) and cognitive measures, including FSIQ, PIQ, and VIQ, across the entire span of the longitudinal study. These correlations were stable throughout the mean 6.4 years of follow-up (Supplementary Table 3).

Glycemic Indices: Correlations With Brain Volume and Neurocognitive Scores

There was consistent hyperglycemia with % sensor glucose above target (>180 mg/dL) ∼50% of the time at all four time points, signaling persistent chronic exposure to hyperglycemia. The lifelong index of hyperglycemia (HbA1c AUC >6%) was also consistently high during the study. In aggregate, there was very little biochemical hypoglycemia documented throughout the study (Table 1).

We chose three representative metrics of dysglycemia—HbA1c AUC >6%, % sensor glucose above target (>180 mg/dL), and SD of sensor glucose (a measure of variability)—to assess associations with brain metrics. Estimated correlations (Table 3) showed a highly significant negative relationship between measures of cognition, including FSIQ, PIQ, and VIQ, and HbA1c AUC >6%, % sensor glucose >180 mg/dL, and SD of sensor glucose across all time points. Similarly, there was a negative correlation between glycemic metrics and total and gray matter volume but mostly with HbA1c AUC >6%.

Table 3.

Correlations between neurocognitive scores and brain volume measures with three metrics of dysglycemia in the type 1 diabetes group (longitudinal mixed-effects modeling)

| Age | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 years | 8 years | 10 years | 12 years | |

| Neurocognitive metrics | ||||

| HbA1c AUC >6% | ||||

| FSIQ | −0.256 (0.086) P = 0.003 |

−0.270 (0.075) P = 0.000 |

−0.298 (0.074) P = 0.000 |

−0.303 (0.075) P = 0.000 |

| PIQ | −0.171 (0.095) P = 0.071 |

−0.214 (0.081) P = 0.008 |

−0.246 (0.079) P = 0.002 |

−0.261 (0.079) P = 0.001 |

| VIQ | −0.262 (0.081) P = 0.001 |

−0.268 (0.072) P = 0.000 |

−0.297 (0.071) P = 0.000 |

−0.299 (0.075) P = 0.000 |

| % Sensor glucose >180 mg/dL | ||||

| FSIQ | −0.396 (0.103) P = 0.000 |

−0.420 (0.078) P = 0.000 |

−0.382 (0.066) P = 0.000 |

−0.287 (0.082) P = 0.000 |

| PIQ | −0.279 (0.105) P = 0.008 |

−0.330 (0.083) P = 0.000 |

−0.314 (0.073) P = 0.000 |

−0.219 (0.085) P = 0.010 |

| VIQ | −0.365 (0.095) P = 0.000 |

−0.366 (0.074) P = 0.000 |

−0.350 (0.067) P = 0.000 |

−0.320 (0.086) P = 0.000 |

| SD sensor glucose | ||||

| FSIQ | −0.397 (0.083) P = 0.000 |

−0.420 (0.073) P = 0.000 |

−0.407 (0.069) P = 0.000 |

−0.327 (0.090) P = 0.000 |

| PIQ | −0.292 (0.088) P = 0.001 |

−0.304 (0.083) P = 0.000 |

−0.289 (0.082) P = 0.000 |

−0.202 (0.097) P = 0.037 |

| VIQ | −0.385 (0.083) P = 0.000 |

−0.413 (0.072) P = 0.000 |

−0.409 (0.069) P = 0.000 |

−0.393 (0.085) P = 0.000 |

| Brain structure metrics | ||||

| HbA1c AUC >6% | ||||

| Total brain volume | −0.171 (0.082) P = 0.036 |

−0.188 (0.076) P = 0.014 |

−0.203 (0.073) P = 0.005 |

−0.207 (0.071) P = 0.004 |

| Gray matter volume | −0.149 (0.083) P = 0.073 |

−0.195 (0.076) P = 0.011 |

−0.238 (0.073) P = 0.001 |

−0.263 (0.072) P = 0.000 |

| White matter volume | −0.188 (0.079) P = 0.018 |

−0.165 (0.076) P = 0.029 |

−0.145 (0.074) P = 0.052 |

−0.120 (0.074) P = 0.104 |

| % Sensor glucose >180 mg/dL | ||||

| Total brain volume | −0.003 (0.080) P = 0.969 |

−0.028 (0.071) P = 0.693 |

−0.057 (0.069) P = 0.404 |

−0.081 (0.076) P = 0.285 |

| Gray matter volume | −0.037 (0.083) P = 0.653 |

−0.071 (0.072) P = 0.328 |

−0.101 (0.070) P = 0.152 |

−0.114 (0.079) P = 0.150 |

| White matter volume | 0.031 (0.080) P = 0.702 |

0.025 (0.073) P = 0.730 |

0.002 (0.070) P = 0.981 |

−0.029 (0.076) P = 0.702 |

| SD sensor glucose | ||||

| Total brain volume | −0.238 (0.083) P = 0.004 |

−0.221 (0.078) P = 0.005 |

−0.174 (0.078) P = 0.027 |

−0.099 (0.088) P = 0.264 |

| Gray matter volume | −0.275 (0.082) P = 0.001 |

−0.265 (0.076) P = 0.000 |

−0.217 (0.076) P = 0.004 |

−0.130 (0.087) P = 0.136 |

| White matter volume | −0.174 (0.086) P = 0.044 |

−0.148 (0.082) P = 0.071 |

−0.106 (0.082) P = 0.194 |

−0.053 (0.088) P = 0.549 |

Conclusions

This longitudinal, observational study uses contemporary tools to assess the impact of diabetes in the developing brain of young children, providing a unique opportunity to investigate the effects of the disease over time. Differences in FSIQ and VIQ between groups were present from the start and were maintained throughout the study, indicating that early effects of diabetes are detectable and significant. Group differences from age 6 to 12 years were significant in all three major structural brain measures—total, gray, and white matter volumes—with increased between-group divergence over time. This is a potentially important finding that suggests cumulative effects on the developing central nervous system. These detected differences were mostly related to metrics of hyperglycemia.

Cognitive Assessments

Available data support the notion that cognitive decline is associated with type 1 diabetes and that poor metabolic control has a deleterious impact on cognitive functioning, with lower IQ, executive functions, and processing speed (18–20). Similar to adults, cross-sectional studies in youth with type 1 diabetes have shown lower IQ and deficits in executive functioning, particularly attention, episodic, and spatial working memory and processing speed, compared with control subjects (21–23). However, longitudinal studies of cognition in youth with type 1 diabetes have previously shown mixed results (24–26). A study from the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial showed no substantial declines in cognitive function in a large group with type 1 diabetes carefully followed for ∼18 years, despite relatively high rates of recurrent severe hypoglycemia (27). However, that study cohort (13–39 years old) did not include very young children, in whom the effects of diabetes on cognition are most pronounced. Variability in cognitive findings in type 1 diabetes is affected by age, disease duration, severity of hypoglycemia, degree of chronic hyperglycemia, earlier onset, and sensitivity of test batteries; many of these factors are intercorrelated (22,26,28,29). Our results indicate that patients diagnosed with diabetes at a very young age when the brain is undergoing rapid developmental changes may be at greatest risk for neurocognitive deficits (24,25,30,31).

DirecNet has now followed the pediatric cohort reported here for four time periods over a mean span of 6.4 ± 0.4 years (range 5.3–7.8 years), allowing us to assess the trajectory of change between the children with diabetes and age-matched control subjects. We previously reported that IQ and executive function scores trended lower in type 1 diabetes relative to control over an initial 18-month period of observation (13,14). In the present work, we now report results in this large cohort of children over two additional time periods, which altogether cover a mean span of 6.4 ± 0.4 years of follow-up. Our data at times 3 and 4 now clearly indicate statistically significant differences in neurocognitive function between the cohorts of children with and without type 1 diabetes. Specifically, using mixed-effects modeling covarying for parent IQ, the diabetes cohort shows lower IQ scores, with the most prominent effects observed for VIQ (Table 2 and Fig. 1) and the vocabulary subtest score (see Supplementary Table 1). Effects sizes ranged from 0.26 to 0.35 for these significant between-group results. Although children with diabetes were still functioning well, and the IQ scores were within the normal range, group differences amounted to an average of almost 4 IQ points. Even though in this particular high-functioning cohort this may not readily affect school performance or relational behaviors, this is well within the range observed in other conditions that affect the brain in children (32–34). Thus, as our type 1 diabetes cohort has matured through early adolescence and the duration of their disease lengthened, between-group neurocognitive differences have become readily detectable.

Structural Assessments

MRI data have shown prevalence of structural central nervous system abnormalities in children with early-onset type 1 diabetes compared with control subjects without diabetes (1,4,5,35,36). For example, Ho et al. (36) studied 62 children with type 1 diabetes (mean age 9.8 years) diagnosed before 6 years of age and showed a high prevalence of central nervous system structural abnormalities and mesial temporal sclerosis. When children with type 1 diabetes reported here were 4 to <10 years old, we observed increased gray matter volume in lateral temporofrontal and decreased volume in parieto-occipital regions compared with control subjects, findings supported by complementary vertex-based analyses (FreeSurfer) (9,11). Differences in white matter microstructure were also detected with diffusion tensor imaging in children with diabetes, with lower axial diffusivity, a measure of brain fiber coherence, in children with diabetes at baseline and at 18 months, indicating that these white matter differences persist over time (7,8). By 18 months, children with diabetes had slower total, gray, and white matter growth than control subjects (10), with specific gray matter regions (left precuneus; right temporal, frontal, and parietal lobes; right medial frontal cortex) showing reduced growth trajectories in diabetes, as did particular white matter areas (splenium of the corpus callosum, bilateral superior parietal lobe, bilateral anterior forceps, inferior frontal fasciculus). Frontal and parieto-occipital cortical regions appear most vulnerable, particularly in individuals with early age of onset.

We now extend our analysis across a mean span of 6.4 years (range 5.3–7.8 years) and observed significant slower growth of total, gray, and white matter volume in the cohort with diabetes versus the age-matched control cohort. Persistent volumetric differences across all four time points, along with detectable cognitive deficits compared with control subjects, suggest that the impact of diabetes in the brain begins early in the disease process.

Associations With Dysglycemia

In older children with type 1 diabetes, greater lifetime exposure to hyperglycemia was associated with decreased total gray matter volume during a 2-year follow-up (4) and decreased white matter volume in the occipital lobe with greater hypoglycemia exposure (5). Although severe hypoglycemia is well recognized as noxious to the brain, in our work to date in DirecNet, we have observed a consistent association between detected brain differences and metrics of hyperglycemia, including HbA1c AUC >6%, SD sensor glucose, % sensor glucose above target, and mean amplitude of glycemic excursions (7–16). The slower brain growth observed after 18 months of follow-up was associated with higher cumulative hyperglycemia and glucose variability but not with hypoglycemia (10). In the present study, we report in the diabetes group strong negative associations between FSIQ, PIQ, and VIQ and HbA1c AUC >6%, % sensor glucose >180 mg/dL, and SD of sensor glucose. Similarly, brain volumes (total, gray, and white matter) were reciprocally related to hyperglycemia, using the same metrics. The frequency of biochemical hypoglycemia was quite low in our studies (2.5–3% of all sensor glucose values), making it difficult to detect associations. Considering that ∼50% of sensor glucose values were >180 mg/dL throughout the mean 6.4 years of follow-up in the children with diabetes, these associations of hyperglycemia and detected changes in brain structure and cognition are concerning and support the notion that chronically elevated glucose is indeed noxious to the developing brain.

Recently, our group has performed functional MRI in our cohort using an executive function paradigm, the Go/No-Go task, and observed that despite equivalent task performance between groups, children with type 1 diabetes exhibited increased activation in executive control regions (37). We posited that this finding may represent a compensatory neural response to diabetes-related insult and facilitate cognitive and behavioral performance to levels equivalent to those of control subjects without diabetes. However, when these same children were given a more challenging visual-spatial working memory task (N back), the diabetes group exhibited reduced performance and greater modulation of activation compared with the healthy control group without diabetes (38). These differences were associated with earlier diabetes onset, suggesting that elevated glucose concentrations likely contribute to functional brain differences. These findings are supported further by recent functional MRI data gathered during euglycemic and hyperglycemic clamp conditions in adolescents with type 1 diabetes that showed lower spatial working memory capacity during acute hyperglycemia (39).

The mechanisms of changes in brain structure, cognition, and function in type 1 diabetes are unknown, but collectively, these and other reports suggest the possibility that glycosylation of brain proteins has a functional impact on neurocognitive function of affected children, especially those who are very young at diagnosis. Biessels and Reijmer (40) suggested that human cortical development from childhood to adolescence is affected in diabetes and that not only hypoglycemia but also hyperglycemia may affect developmental processes, leading to adverse cognitive outcomes in childhood or even later in life.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has considerable strengths, including the large cohort, the young age at study entry, the longitudinal nature of the repeated assessments, the strict standardization of the imaging equipment and image acquisition protocols used at all centers, the certification of all cognitive testers and central double scoring of all tests, and the availability of CGM data throughout the study. The need to replace 26% of the participants at time 3 is a limitation but one that is largely inevitable in longitudinal studies and one for which we planned because there was a >2-year gap between funding cycles and grant renewals. The fact that we were able to retain 74% of the original cohort is remarkable because these were laborious studies. The fact that replacements matched the lost study subjects well in terms of diabetes duration and control makes the aggregate data credible. Subanalysis of our results on the basis of further DKA or severe hypoglycemia episodes throughout the observation period was not possible because of the scarcity of those events after study initiation.

In summary, we report here the longest longitudinal study of brain structure and cognition using modern diabetes technology to assess glycemia in a group of young children with type 1 diabetes compared with an age-matched control group without diabetes (4 to <10 years of age at study entry) followed at four time points as they grew and progressed into puberty. Using a mixed-effects model longitudinal analysis, we observed significant differences in FSIQ and VIQ and lower total, gray, and white matter volumes in the diabetes group, differences that persist and, in the case of structural brain measures, increase over time. These changes are strongly related to short-term and long-term indices of hyperglycemia in the diabetes group. Whether these changes are reversible with scrupulous better control of glucose in these young children requires further study. In conclusion, the brain is a target of diabetes complications, even in young children. These data support the lowering of glycemic targets in children (41,42); acceptance of higher-than-normal blood sugars as adequate metabolic control in very young children needs to be revisited.

Article Information

Acknowledgments. The authors thank all the children and their families for participating in these studies. The authors thank the clinical and imaging staff at all the investigator sites as well as external collaborators for the use of imaging facilities, including University of Florida Shands Jacksonville Medical Center, University of California at San Francisco, and El Camino Hospital (Mountain View, CA). The authors also thank Karen Winer, program officer at the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, for advice and support; Roy Beck and the Jaeb Center for Health Research for glucose analytics; and the data and safety monitoring board, including Mark Sperling (chair) (Emeritus University of Pittsburgh), Dorothy M. Becker (University of Pittsburgh), Carla Greenbaum (Benaroya Research Institute), and Antoinette Moran (University of Minnesota). The authors are grateful to Medtronic for supplying the iPro2 CGM and to LifeScan for supplying the OneTouch Ultra 2 meter and test strips used in these studies.

Funding. This research was supported by National Institutes of Health Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grant R01-HD-078463 as well as grants U01-HD-41908, U01-HD-41915, U01-HD-41918, U01-HD-56526, and U01-HD-41906 (Washington University in St. Louis), and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services grants U54-HD-087011 (Washington University in St. Louis) and UL1-TR-001085 (Stanford University).

Duality of Interest. N.M. had institutional device supply agreements from Medtronic for CGM and LifeScan for test strips for the study, research support from Novo Nordisk, and pending institutional grants from Dexcom and Tandem Diabetes. B.B. had consultant agreements with Medtronic Diabetes, Novo Nordisk, Dexcom, ConvaTec, and Tolerion; has provided expert testimony for Dexcom; and has pending research grants with Insulet. E.T. had institutional research grants with AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novo Nordisk, Grifols Therapeutics, Takeda, and Amgen. S.A.W. had consultant agreements with Eli Lilly, Pfizer, and Zealand; institutional grant support from Medtronic, Insulet, and Tandem; and stocks in Insuline. L.A.F. had a device supply agreement with Dexcom. A.M.A. had a device supply agreement with Dexcom. M.T. had a data safety monitoring board agreement with Daiichi Sankyo. W.T. had consultant agreements with AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi and data safety monitoring board agreements with Eisai, MannKind, and Tolerion. K.E. had a consultant agreement with PicoLife Technology. No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Author Contributions. N.M. wrote the manuscript. N.M., B.B., N.H.W., E.T., S.A.W., L.A.F., T.A., A.M.A., M.T., and W.T. recruited and studied patients and reviewed and edited the manuscript. N.M. and A.L.R. are the principal investigators of the study and obtained funding. B.J., L.C.F.-R., H.S., P.M., and M.M. performed the statistical analysis and reviewed and edited the manuscript. A.C. and T.H. studied patients, analyzed cognitive data, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. K.E. is the study-wide project manager, studied patients, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. A.L.R. critiqued and edited the manuscript. N.M. and A.L.R. are the guarantors of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and A.L.R. takes responsibility for the accuracy of the data analysis.

Prior Presentation. Parts of this study were presented at the 79th Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes Association, San Francisco, CA, 7–11 June 2019, and the 13th International Conference on Advanced Technologies & Treatments for Diabetes, Madrid, Spain, 19–22 February 2020.

Footnotes

Clinical trial reg. no. NCT02351466, clinicaltrials.gov

This article contains supplementary material online at https://doi.org/10.2337/figshare.13549097.

A complete list of the Diabetes Research in Children Network (DirecNet) can be found in the supplementary material online.

References

- 1.Ferguson SC, Blane A, Wardlaw J, et al. Influence of an early-onset age of type 1 diabetes on cerebral structure and cognitive function. Diabetes Care 2005;28:1431–1437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Musen G, Lyoo IK, Sparks CR, et al. Effects of type 1 diabetes on gray matter density as measured by voxel-based morphometry. Diabetes 2006;55:326–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wessels AM, Simsek S, Remijnse PL, et al. Voxel-based morphometry demonstrates reduced grey matter density on brain MRI in patients with diabetic retinopathy. Diabetologia 2006;49:2474–2480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perantie DC, Wu J, Koller JM, et al. Regional brain volume differences associated with hyperglycemia and severe hypoglycemia in youth with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2007;30:2331–2337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perantie DC, Koller JM, Weaver PM, et al. Prospectively determined impact of type 1 diabetes on brain volume during development. Diabetes 2011;60:3006–3014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mergenthaler P, Lindauer U, Dienel GA, Meisel A. Sugar for the brain: the role of glucose in physiological and pathological brain function. Trends Neurosci 2013;36:587–597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnea-Goraly N, Raman M, Mazaika P, et al.; Diabetes Research in Children Network (DirecNet) . Alterations in white matter structure in young children with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2014;37:332–340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fox LA, Hershey T, Mauras N, et al.; Diabetes Research in Children Network (DirecNet) . Persistence of abnormalities in white matter in children with type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia 2018;61:1538–1547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marzelli MJ, Mazaika PK, Barnea-Goraly N, et al.; Diabetes Research in Children Network (DirecNet) . Neuroanatomical correlates of dysglycemia in young children with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 2014;63:343–353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mauras N, Mazaika P, Buckingham B, et al.; Diabetes Research in Children Network (DirecNet) . Longitudinal assessment of neuroanatomical and cognitive differences in young children with type 1 diabetes: association with hyperglycemia. Diabetes 2015;64:1770–1779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mazaika PK, Weinzimer SA, Mauras N, et al.; Diabetes Research in Children Network (DirecNet) . Variations in brain volume and growth in young children with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 2016;65:476–485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hosseini SM, Mazaika P, Mauras N, et al.; Diabetes Research in Children Network (DirecNet) . Altered integration of structural covariance networks in young children with type 1 diabetes. Hum Brain Mapp 2016;37:4034–4046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cato MA, Mauras N, Ambrosino J, et al.; Diabetes Research in Children Network (DirecNet) . Cognitive functioning in young children with type 1 diabetes. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2014;20:238–247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cato MA, Mauras N, Mazaika P, et al.; Diabetes Research in Children Network . Longitudinal evaluation of cognitive functioning in young children with type 1 diabetes over 18 months. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2016;22:293–302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foland-Ross LC, Reiss AL, Mazaika PK, et al.; Diabetes Research in Children Network . Longitudinal assessment of hippocampus structure in children with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes 2018;19:1116–1123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aye T, Mazaika PK, Mauras N, et al.; Diabetes Research in Children Network (DirecNet) Study Group . Impact of early diabetic ketoacidosis on the developing brain. Diabetes Care 2019;42:443–449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barnea-Goraly N, Weinzimer SA, Ruedy KJ, et al.; Diabetes Research in Children Network (DirecNet) . High success rates of sedation-free brain MRI scanning in young children using simple subject preparation protocols with and without a commercial mock scanner--the Diabetes Research in Children Network (DirecNet) experience. Pediatr Radiol 2014;44:181–186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCrimmon RJ, Ryan CM, Frier BM. Diabetes and cognitive dysfunction. Lancet 2012;379:2291–2299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brands AM, Biessels GJ, de Haan EHF, Kappelle LJ, Kessels RPC. The effects of type 1 diabetes on cognitive performance: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2005;28:726–735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Musen G, Tinsley LJ, Marcinkowski KA, et al. Cognitive function deficits associated with long-duration type 1 diabetes and vascular complications. Diabetes Care 2018;41:1749–1756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gaudieri PA, Chen R, Greer TF, Holmes CS. Cognitive function in children with type 1 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2008;31:1892–1897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blasetti A, Chiuri RM, Tocco AM, et al. The effect of recurrent severe hypoglycemia on cognitive performance in children with type 1 diabetes: a meta-analysis. J Child Neurol 2011;26:1383–1391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stanisławska-Kubiak M, Mojs E, Wójciak RW, et al. An analysis of cognitive functioning of children and youth with type 1 diabetes (T1DM) in the context of glycemic control. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2018;22:3453–3460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Northam EA, Rankins D, Lin A, et al. Central nervous system function in youth with type 1 diabetes 12 years after disease onset. Diabetes Care 2009;32:445–450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin A, Northam EA, Rankins D, Werther GA, Cameron FJ. Neuropsychological profiles of young people with type 1 diabetes 12 yr after disease onset. Pediatr Diabetes 2010;11:235–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ly TT, Anderson M, McNamara KA, Davis EA, Jones TW. Neurocognitive outcomes in young adults with early-onset type 1 diabetes: a prospective follow-up study. Diabetes Care 2011;34:2192–2197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jacobson AM, Musen G, Ryan CM, et al.; Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications Study Research Group .Long-term effect of diabetes and its treatment on cognitive function. N Engl J Med 2007;356:1842–1852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hershey T, Perantie DC, Warren SL, Zimmerman EC, Sadler M, White NH. Frequency and timing of severe hypoglycemia affects spatial memory in children with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2005;28:2372–2377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Naguib JM, Kulinskaya E, Lomax CL, Garralda ME. Neuro-cognitive performance in children with type 1 diabetes--a meta-analysis. J Pediatr Psychol 2009;34:271–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fox MA, Chen RS, Holmes CS. Gender differences in memory and learning in children with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM) over a 4-year follow-up interval. J Pediatr Psychol 2003;28:569–578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCarthy AM, Lindgren S, Mengeling MA, Tsalikian E, Engvall JC. Effects of diabetes on learning in children. Pediatrics 2002;109:E9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meier MH, Caspi A, Ambler A, et al. Persistent cannabis users show neuropsychological decline from childhood to midlife. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012;109:E2657–E2664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sorensen LG, Neighbors K, Martz K, Zelko F, Bucuvalas JC, Alonso EM; Studies of Pediatric Liver Transplantation (SPLIT) Research Group and the Functional Outcomes Group (FOG) . Longitudinal study of cognitive and academic outcomes after pediatric liver transplantation. J Pediatr 2014;165:65–72.e224801243 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dion LA, Saint-Amour D, Sauvé S, Barbeau B, Mergler D, Bouchard MF. Changes in water manganese levels and longitudinal assessment of intellectual function in children exposed through drinking water. Neurotoxicology 2018;64:118–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Antenor-Dorsey JA, Meyer E, Rutlin J, et al. White matter microstructural integrity in youth with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 2013;62:581–589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ho MS, Weller NJ, Ives FJ, et al. Prevalence of structural central nervous system abnormalities in early-onset type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Pediatr 2008;153:385–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Foland-Ross LC, Buckingam B, Mauras N, et al.; Diabetes Research in Children Network (DirecNet) . Executive task-based brain function in children with type 1 diabetes: an observational study. PLoS Med 2019;16:e1002979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Foland-Ross LC, Tong G, Mauras N, et al.; Diabetes Research in Children Network (DirecNet) . Brain function differences in children with type 1 diabetes: a functional MRI study of working memory. Diabetes 2020;69:1770–1778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Šuput Omladič J, Slana Ozimič A, Vovk A, et al. Acute hyperglycemia and spatial working memory in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2020;43:1941–1944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Biessels GJ, Reijmer YD. Brain changes underlying cognitive dysfunction in diabetes: what can we learn from MRI? Diabetes 2014;63:2244–2252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.American Diabetes Association . 13. Children and adolescents: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2020. Diabetes Care 2020;43(Suppl. 1):S163–S182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.DiMeglio LA, Acerini CL, Codner E, et al. ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2018: glycemic control targets and glucose monitoring for children, adolescents, and young adults with diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes 2018;19(Suppl. 27):105–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]