Abstract

The intermolecular three-component alkene vicinal dicarbofunctionalization (DCF) reaction allows installation of two different carbon fragments. Despite extensive investigation into its ionic chemistry, the enantioseletive radical-mediated versions of DCF reactions remain largely unexplored. Herein, we report an intermolecular, enantioselective three-component radical vicinal dicarbofunctionalization reaction of olefins enabled by merger of radical addition and cross-coupling using photoredox and copper dual catalysis. Key to the success of this protocol relies on chemoselective addition of acyl and cyanoalkyl radicals, generated in situ from the redox-active oxime esters by a photocatalytic N-centered iminyl radical-triggered C-C bond cleavage event, onto the alkenes to form new carbon radicals. Single electron metalation of such newly formed carbon radicals to TMSCN-derived L1Cu(II)(CN)2 complex leads to asymmetric cross-coupling. This three-component process proceeds under mild conditions, and tolerates a diverse range of functionalities and synthetic handles, leading to valuable optically active β–cyano ketones and alkyldinitriles, respectively, in a highly enantioselective manner (>60 examples, up to 97% ee).

Subject terms: Homogeneous catalysis, Reaction mechanisms, Synthetic chemistry methodology

Vicinal dicarbofunctionalization (DCF) reactions of alkenes have been extensively explored in ionic chemistry but the enantioselective radical mediated version of DCF remains largely unexplored. Here, the authors demonstrate a radical vicinal DCF reaction of olefins by merging of radical addition and cross-coupling using photoredox and copper dual catalysis.

Introduction

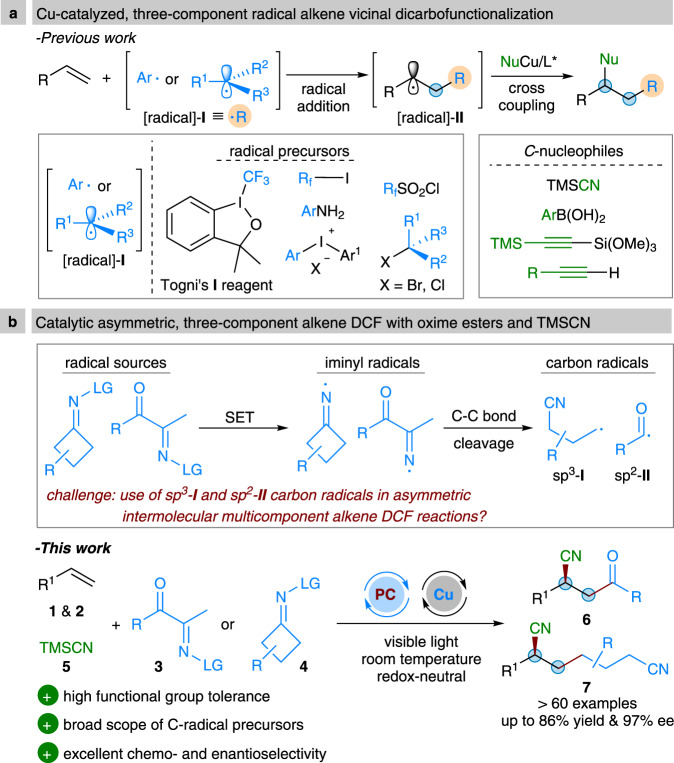

Alkenes are arguably one of the most privileged and versatile chemicals in organic synthesis because a diverse range of functional groups could be readily introduced across the C = C π system by many classic vicinal difunctionalization reactions1–4. In this context, one of the most investigated and fundamental transformations is the intermolecular three-component alkene vicinal dicarbofunctionalization (DCF) reaction, which allows installation of two different carbon fragments. While these reactions have been extensively explored in ionic chemistry, radical mediated, especially the enantioseletive versions of such reaction class remain largely unexplored5–10. Given the unique reactivity modes of radical species, the development of radical-mediated alkene vicinal DCF reactions would enable a wider variety of functional groups and synthetic handles to be incorporated, and hence produce valuable target molecules11–15. While particularly promising, controlling the stereoselectivity in radical alkene vicinal DCF reactions is a long-standing and fundamental challenge due to the intrinsically high reactivity and instability of radical intermediates16–18. In recent years, owing to their unique single-electron transfer (SET) ability and good coordination with chiral ligands, chiral copper catalysis opened a new and robust platform for the development of asymmetric radical-mediated alkene vicinal DCF reactions (Fig. 1a)19–21. For example, the Liu group disclosed that carbon-centered radicals, which are formed in situ by decarboxylative C–C bond cleavage of N-hydroxy-phthalimide esters22, or upon addition of CF3 and (fluoro)alkyl23–28 or aryl radicals29 to alkenes or enamides, could couple with TMSCN, boronic acid, or alkyne-derived chiral copper(II) complexes, leading to alkene vicinal DCF products with excellent enantiomeric excess. Recently, Zhang30 and Liu31–33 reported elegant examples of copper-catalyzed highly enantioselective radical alkene 1,2-DCF with diaryliodonium salts and alkyl halides as radical sources, respectively. Despite the broad synthetic applicability of these methods, however, the intrinsic redox potential window of copper catalysts, which is critical to the generation of radicals, still results in significant limitations on the scope of radical precursors.

Fig. 1. Catalytic asymmetric three-component radical dicarbofunctionalization reactions of alkenes.

a Cu-catalyzed, three-component radical alkene vicinal dicarbofunctionalization. b Catalytic asymmetric, three-component alkene DCF with oxime esters and TMSCN.

In recent years, visible-light photoredox catalysis has emerged as a powerful tool for organic chemists to develop many elusive radical-mediated chemical transformations with high levels of functional group tolerance34–37. This activation mode also provides a promising approach for the development of radical multicomponent reactions (in some cases with excellent stereoselectivity)38–43. For example, the Studer group recently developed an asymmetric three-component cascade reaction of quinolines or pyridines with enamides using α-bromo carbonyl compounds as radical precursors under photoredox and phosphoric acid dual catalysis44. Using this strategy, a range of chiral γ-amino acid derivatives could be achieved with high chemo-, regio-, and enantioselectivity. Recently, our group45–48 and others49–55 introduced readily accessible redox-active oxime derivatives as precursors to generate iminyl radicals under SET reduction or oxidation conditions (Fig. 1b). The resultant iminyl radicals further triggered smooth formation of sp3 cyanoalkyl and sp2 acyl56–58 radicals via a C–C bond cleavage process. Despite extensive synthetic utility of these carbon radicals, to our knowledge, their engagement in asymmetric multicomponent alkene vicinal DCF reactions is still challenging and unexplored59,60. As a result, we aimed at developing a catalytic asymmetric three-component radical vicinal DCF reaction of alkenes with oximes and TMSCN (Fig. 1b). This protocol would provide an efficient and general approach for preparation of valuable optically active β-cyano ketones and alkyldinitriles61–63.

Results

Optimization of reaction conditions

Our optimization began by reacting 2-vinylnaphthalene 1a with oxime ester 3a and TMSCN in a ratio of 1:3:3 in DMA under the dual photoredox and copper catalysis (Table 1). After some experimentation (see supporting information for more details), we found that the target three-component reaction indeed occurred to give a moderate yield of desired product 6aa with 88% ee, when using photocatalyst fac-Ir(ppy)3 (1 mol%), and a combination of Cu(CH3CN)4PF6 (0.5 mol%) and Box-type ligand L1 (0.6 mol%) under irradiation of purple LEDs (Table 1, entry 1). However, several competing processes were also involved. For example, in addition to 6aa, a significant amount of side products sp-1, sp-2, and sp-3 were also detected, which might result from acyl radical 3a-II-mediated two-component cross-coupling with 1a and TMSCN, or its own dimerization. A brief screening of typical solvents such as DMF, CH3CN, and THF showed that DMA was still the best of choice in terms of reaction efficiency (Table 1, entry 1 vs entries 2–5). Notably, when the catalyst loading of fac-Ir(ppy)3 was decreased to 0.8 mol%, a cleaner reaction was observed, and a 64% yield of 6aa was obtained without effect on the enantioselectivity (Table 1, entry 6). An extensive survey of other commonly used copper salts and chiral ligands established that the combination of Cu(CH3CN)4PF6 and Box-type ligand L1 were superior to others (Table 1, entries 6–8). Further optimization studies with respect to the loading of copper salt and concentration confirmed that a combination of 1.5 mol% of Cu(CH3CN)4PF6 and 2.25 mol% of ligand L1 with 0.8 mol% of fac-Ir(ppy)3 at a concentration of 0.04 M gave the best results, with 6aa being isolated with 74% yield and 90% ee (Table 1, entry 11). It was postulated that rational tuning of catalyst loading can help regulate the concentration of the reactive radical species, thus suppressing the competing side reaction pathways. Then, we examined other commonly used light sources including blue LEDs (2 × 3 W, λmax = 460 nm) and CFL lamp (40 W) in the model reaction (entries 12 and 13). Both reactions could also work to give the desired products with 90% ee, but in only moderate yields due to decreased conversion and formation of considerable amounts of byproducts. These results showed that the wavelength of the light has notable effect on the reaction efficiency. As expected, a series of control experimental results established that each component (light, photocatalyst, and copper salt) is critical to this asymmetric alkene vicinal DCF reaction (see supporting information for more details).

Table 1.

Optimization of the reaction conditions.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | x/y/z (mol%) | Solvent | sp-1/sp-2/sp-3 (%)a | Yield (%)a | ee (%)b |

| 1 | 0.5/0.6/1.0 | DMA (0.05 M) | 6/4/4 | 41 | 88 |

| 2 | 0.5/0.6/1.0 | DMF (0.05 M) | 2/5/1 | 39 | 89 |

| 3 | 0.5/0.6/1.0 | CH3CN (0.05 M) | 1/11/– | 6 | 90 |

| 4 | 0.5/0.6/1.0 | THF (0.05 M) | 1/9/– | 15 | 90 |

| 5 | 0.5/0.6/1.0 | CH2Cl2 (0.05 M) | 1/14/– | 9 | 90 |

| 6 | 0.5/0.6/0.8 | DMA (0.05 M) | 7/3/2 | 64 | 88 |

| 7c | 0.5/0.6/0.8 | DMA (0.05 M) | 6/7/3 | 51 | 85 |

| 8d | 0.5/0.6/0.8 | DMA (0.05 M) | 8/2/2 | 69 | 81 |

| 9e | 0.5/0.6/0.8 | DMA (0.05 M) | 10/1/6 | 16 | 68 |

| 10 | 1.5/2.25/0.8 | DMA (0.05 M) | 6/12/1 | 78 | 90 |

| 11 | 1.5/2.25/0.8 | DMA (0.04 M) | 3/3/2 | 88 (74) | 90 |

| 12 f | 1.5/2.25/0.8 | DMA (0.04 M) | 5/33/1 | 41 | 90 |

| 13 g | 1.5/2.25/0.8 | DMA (0.04 M) | 6/31/2 | 39 | 90 |

Reaction conditions: 1a (0.1 mmol), 3a (0.3 mmol), TMSCN (0.3 mmol), Cu(CH3CN)4PF6 (x mol%), ligand L1 (y mol%), fac-Ir(ppy)3 (z mol%), solvent (2.0–2.5 mL), 2 × 3 W purple LEDs, at room temperature.

CFL compact fluorescent lamp, ppy 2-phenylpyridine, DMA N,N-dimethylacetamide, DMF N,N-dimethylformamide.

aYields were determined by GC analysis, with isolated yield in parentheses.

bDetermined by HPLC analysis on a chiral stationary phase.

cWith CuCl.

dWith CuI.

eWith Cu(OTf)2.

fUnder the irradiation of 2 × 3 W blue LEDs (λmax = 460 nm) at room temperature.

gUnder the irradiation of CFL (40 W) at room temperature.

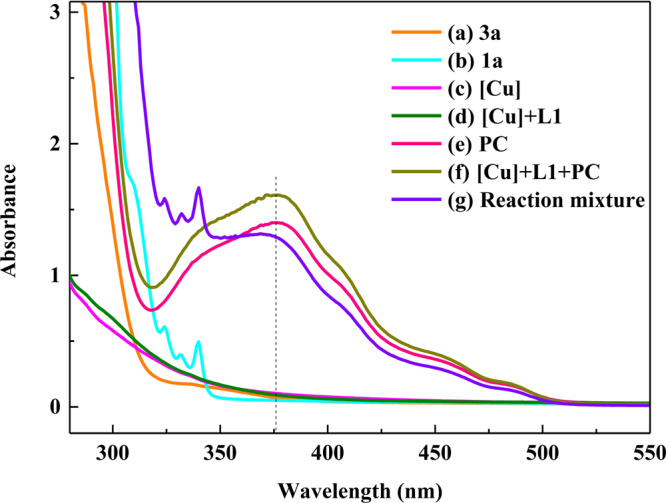

Then, we obtained UV–Vis spectra of the solution containing 3a, 1a, Cu(CH3CN)4PF6, and photocatalyst alone, equimolar mixtures of Cu(CH3CN)4PF6, L1, and photoctalyst, as well as the reaction mixture (Fig. 2). It was found that 3a, 1a, Cu(CH3CN)4PF6, and Cu(CH3CN)4PF6/L1 did not show any very strong absorption bands around the visible region. In contrast, the UV–Vis spectra of photocatalyst, mixture of Cu(CH3CN)4PF6/L1/PC and reaction mixture have the same absorption band at 375 nm, which implied that photocatalyst fac-Ir(ppy)3 could be more efficiently excited by purple LEDs (λmax = 390 nm) than by the blue LEDs (λmax = 460 nm).

Fig. 2. Absorption spectra.

a DMA solution of 3a. b DMA solution of 1a. c DMA solution of Cu(CH3CN)4PF6. d DMA solution of Cu(CH3CN)4PF6/L1. e DMA solution of fac-Ir(ppy)3. f DMA solution of Cu(CH3CN)4PF6/L1/fac-Ir(ppy)3. g Reaction mixture.

Substrate scope

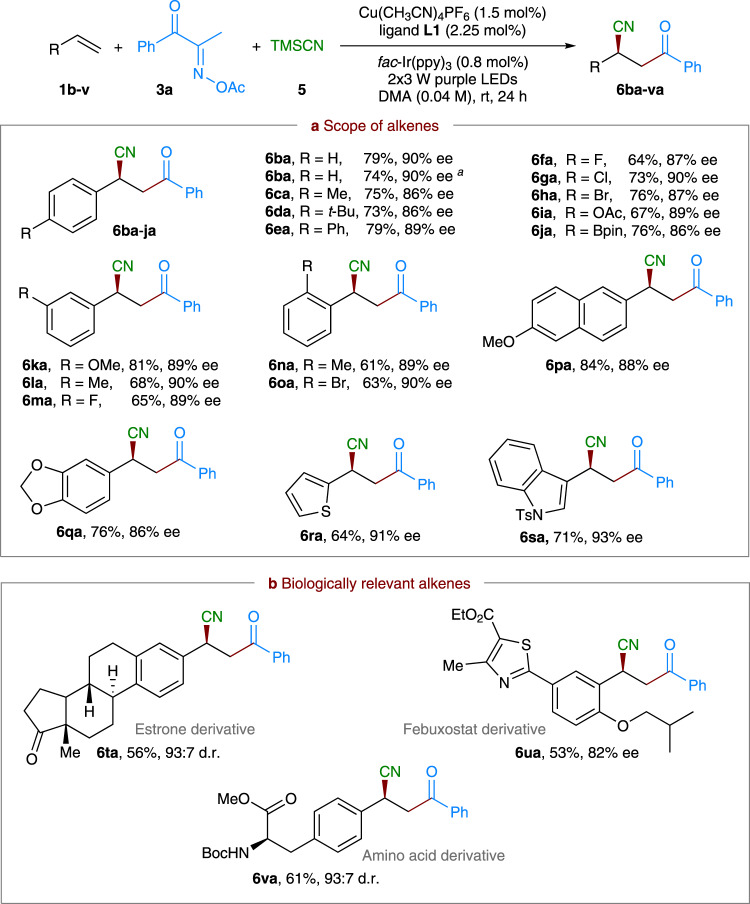

With optimized reaction conditions established, we first investigated the substrate scope of alkenes by reacting with 3a and TMSCN (Fig. 3). Notably, most of these alkenes are inexpensive and commercially available feedstock chemicals. As shown in Fig. 3a, aside from 1a, simple neutral styrene 1b and a range of styrene derivatives 1c–j with electron-donating (e.g., Me, tBu, and Ph) or electron-withdrawing (e.g., F, Cl, Br, OAc, and Bpin) functional groups at the para-position of the aromatic ring are well tolerated, furnishing the corresponding products 6ba–ja in 64–79% yields with 86–90% ee. Notably, halide substituents, F, Cl, and Br, as well as Bpin moiety remained intact after the reaction, thereby facilitating further modifications at their positions (e.g., products 6fa–ha and 6ja). A 1.0 mmol scale reaction of 1b also proceeded smoothly to give comparable results (6ba, 74% yield, 90% ee), demonstrating the scalability of this process. Moreover, the reactions with alkenes 1k–o bearing common substituents, such as methoxy, methyl, fluoro, and bromo at the meta- or ortho-positions also worked well; and the expected products 6ka–oa were isolated in 61–81% yields with 89–90% ee. 2-Vinylnaphthalene 1p having a methoxy group and heterocycle-containing alkenes 1q–s all proved to be suitable coupling partners, leading to 6pa–sa with good yields and 86–93% ee. Remarkably, this protocol can also be successfully extended to biologically relevant molecule and pharmaceutical-derived styrene analogues (Fig. 3b). For instance, estrone, febuxostat-, and simple amino acid-derived alkenes 1t–v reacted well to give the desired acylcyanation products 6ta, 6ua, and 6va with good stereoselectivity, respectively. As a result, our protocol should be of potential use for late-stage structural modification of drug and complex compounds. Unfortunately, the current catalytic system is not applicable to simple unactivated or electron-deficient alkenes.

Fig. 3. Scope of the alkenes in asymmetric three-component alkene acylcyanation.

Reaction conditions: 1 (0.1 mmol), 3a (0.3 mmol), TMSCN (0.3 mmol), Cu(CH3CN)4PF6 (1.5 mol%), ligand L1 (2.25 mol%), fac-Ir(ppy)3 (0.8 mol%), DMA (2.5 mL), 2 × 3 W purple LEDs, at room temperature. Isolated yields were reported. The ee and d.r. values were determined by HPLC analysis on a chiral stationary phase. a1.0 mmol scale reaction, 24 h. a Scope of alkenes. b Biologically relevant alkenes.

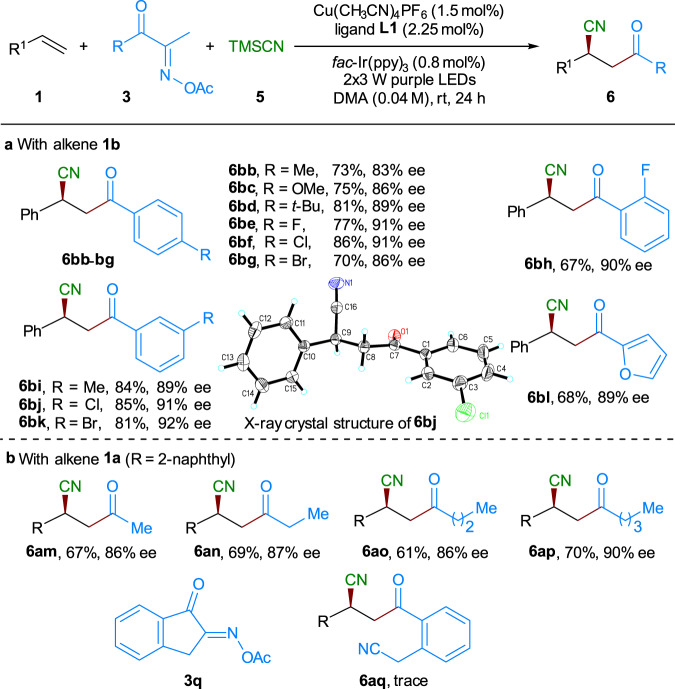

Then, we continued to evaluate the generality of this asymmetric three-component reaction by using a representative set of oxime esters, which can be easily prepared in two steps from the relevant ketone precursors. As shown in Fig. 4a, a range of aryl ketone-derived oxime esters 3b–g with electronically diverse functional groups (e.g., Me, OMe, tBu, F, Cl, or Br) at the para-position of the phenyl ring reacted well with 1b and TMSCN. And the expected alkene acylcyanation products 6bb–bg were obtained with good yields (70–86%) and excellent enantiomeric excess (83–92% ee). As shown in the cases of 3h–k, the change of the substitution pattern and steric hindrance of their phenyl ring has deleterious effect on the reaction efficiency or enantioselectivity, with the corresponding products 6bh–bk being obtained with 67–85% yields and 89–92% ee. Single crystals of product 6bj were obtained, and the absolute stereochemistry was determined to be S by X-ray crystallographic analysis (CCDC 2047031 (6bj) and 2047032 (7ja) contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif), and all other coupling products were tentatively assigned by analogy with 6bj. Remarkably, oxime esters 3m–p derived from aliphatic ketone with various lengths of alkyl chains also reacted well with 2-vinylnaphthalene 1a and TMSCN (Fig. 4b). The relative products 6am–ap were isolated with 61–70% yields and 86–90% ee. We also preliminarily examined the cyclic oxime ester 3q by reacting with 1a and 5 with slightly increased amounts of catalysts. Unfortunately, the reaction proceeded slowly, giving only trace amount of the desired product 6aq together with some byproducts (see supporting information for more details).

Fig. 4. Scope of the oxime esters in asymmetric three-component alkene acylcyanation.

Reaction conditions: 1 (0.1 mmol), 3 (0.3 mmol), TMSCN (0.3 mmol), Cu(CH3CN)4PF6 (1.5 mol%), ligand L1 (2.25 mol%), fac-Ir(ppy)3 (0.8 mol%), DMA (2.5 mL), 2 × 3 W purple LEDs, at room temperature. Isolated yields were reported. The ee and d.r. values were determined by HPLC analysis on a chiral stationary phase. a With alkene 1b. b With alkene 1a.

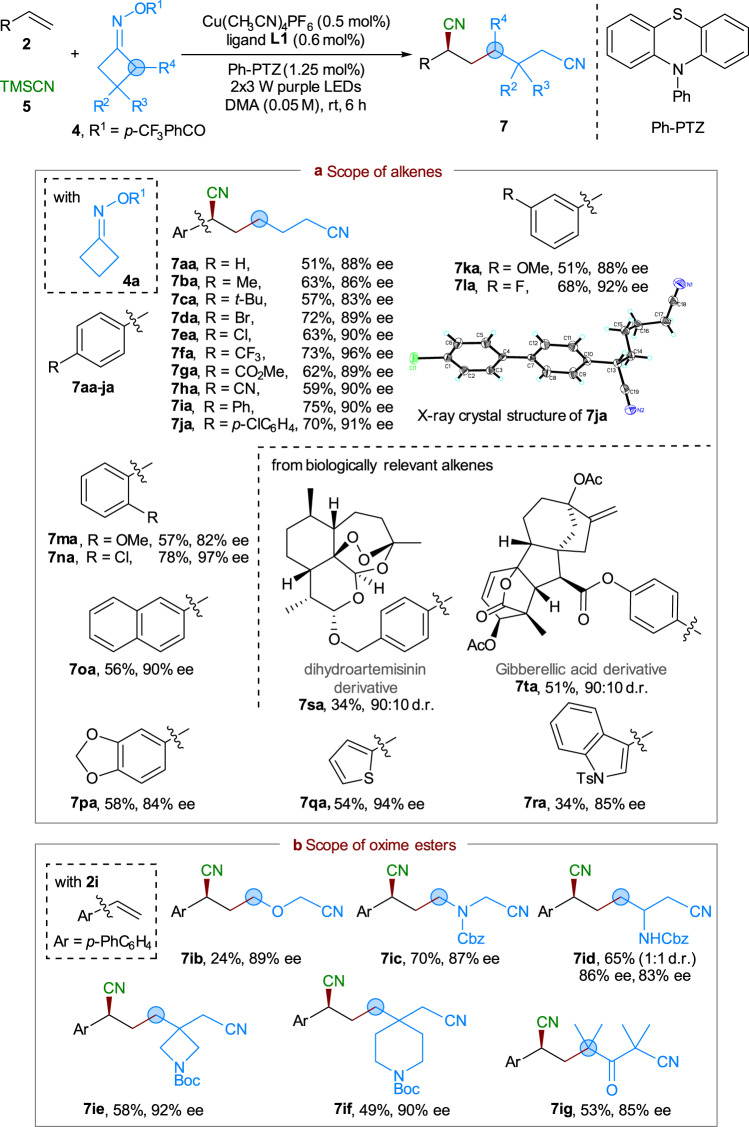

Encouraged by these results, we further attempted to extend the current dual photoredox and copper catalysis strategy to the asymmetric three-component vicinal DCF reaction of cycloketone-derived oxime esters, alkenes, and TMSCN (Fig. 5). Minor modification of the reaction conditions identified that a combination of organic photocatalyst Ph-PTZ (1.25 mol%) and Cu(CH3CN)4PF6 (0.5 mol%)/ligand L1 (0.6 mol%) enabled the desired reaction to proceed smoothly under irradiation of 2 × 3 W purple LEDs at room temperature (see supporting information for more details). This process also exhibited broad substrate scope and good functional tolerance with respect to both alkenes and oxime esters. As shown in Fig. 5a, a wide variety of commercially available styrenes containing neutral (2a), alkyl (2b and 2c), electron-withdrawing (2e–h), or aryl (2i–j) groups at the para-position of the phenyl ring could react well with oxime ester 4a. The corresponding dinitrile products 7aa–ja were obtained in 51–75% yields with 83–96% ee. The absolute stereochemistry of 7ja was also confirmed to be S-configuration by X-ray diffraction (CCDC 2047031 (6bj) and 2047032 (7ja) contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif). Again, as shown in the reactions of alkenes 2k–n, variation of the substitution pattern and steric hindrance of the aromatic ring could be well tolerated, leading to formation of products 7ka–na with 51–78% yields and 82–97% ee. Moreover, the reactions of 2-vinylnaphthalene 2o and substrates containing heterocycle-fused ring (2p) or heteroaryl groups (e.g., 2q, 2r) all proceeded well to give products 7oa–ra with moderate to good yields and excellent enantioselectivity (84–90% ee). Notably, styrenes (e.g., 2s and 2t) derived from dihydroartemisinin and gibberellic acid could also participate in the reaction with good stereoselectivity, suggesting that the method can potentially be used in the late-stage modification of pharmaceutically relevant compounds.

Fig. 5. Scope of the alkenes and cycloketone oxime esters in asymmetric three-component alkene cyanoalkylcyanation reaction.

Reaction conditions: 2 (0.2 mmol), 4 (0.6 mmol), TMSCN (0.6 mmol), Cu(CH3CN)4PF6 (0.5 mol%), ligand L1 (0.6 mol%), Ph-PTZ (1.25 mol%), DMA (4.0 mL), 2 × 3 W purple LEDs, at room temperature. Isolated yields were reported. The ee and d.r. values were determined by HPLC analysis on a chiral stationary phase. a Scope of alkenes. b Scope of oxime esters.

Finally, we turned our attention to study the substrate scope of cyclobutanone oxime esters by reacting with styrene 2i and TMSCN (Fig. 5b). Both oxetan-3-one and 1-Cbz-3-azetidinone derived oxime esters 4b and 4c reacted well to afford 7ib and 7ic in moderate to good yields, with excellent enantioselectivity (87−89% ee). Monosubstituted oxime ester 4d could participate in the reaction smoothly to deliver product 7id as a mixture of diastereomers, with good yield and high enantioselectivity. Note that sterically demanding oxime esters 4e–g also proved to be compatible with the reaction, giving the expected products 7ie–ig in good yields with 85−92% ee.

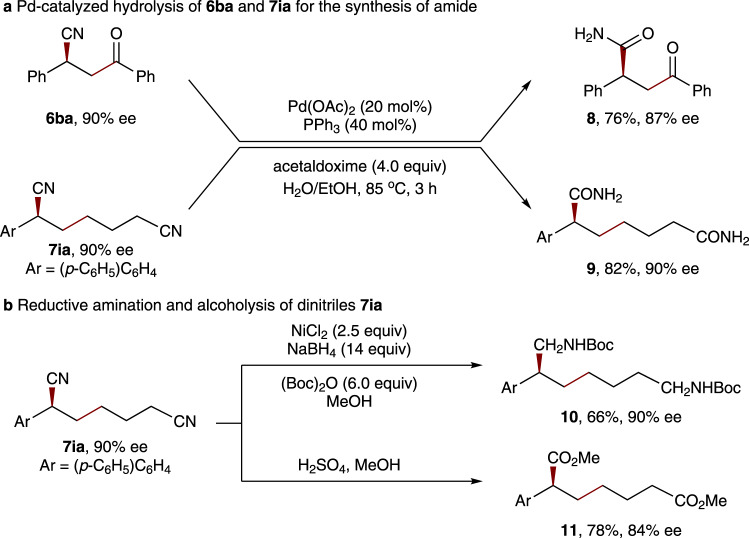

Synthetic applications

To showcase the potential synthetic utility of this asymmetric method in the construction of valuable skeletons, we performed diverse further transformations with the chiral β-cyano ketones and alkyldinitriles (Fig. 6)64,65. For example, the cyano group of 6ba and 7ia could be easily converted to amide group by Pd-catalyzed hydrolysis using stoichiometric acetaldoxime in refluxing aqueous EtOH, giving the corresponding products 8 and 9 with good yields, respectively (Fig. 6a). Moreover, treatment of 7ia with NiCl2/NaBH4 and Boc2O in MeOH allowed efficient sequential reduction and protection of both cyano groups, with aliphatic chiral amine 10 being obtained with 66% yield and 90% ee (Fig. 6b). The synthesis of chiral ester 11 can also be achieved by the treatment of 7ia with alcoholysis. Notably, no notable loss of optical purity was detected in these manipulations.

Fig. 6. Synthetic applications.

a Pd-catalyzed hydrolysis of 6ba and 7ia for the synthesis of amide. b Reductive amination and alcoholysis of dinitriles 7ia.

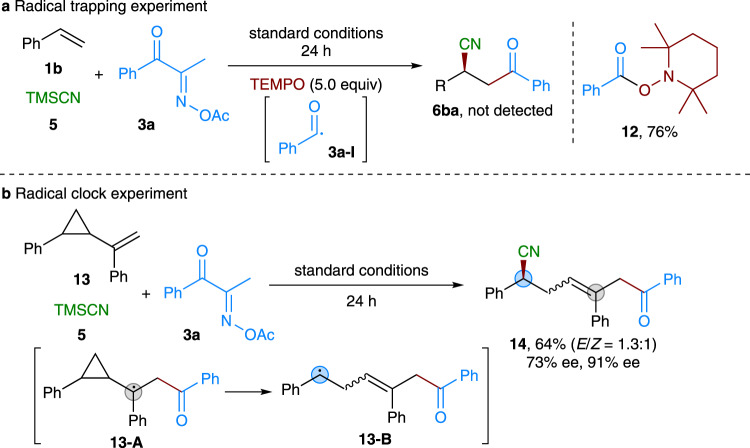

Mechanistic studies

To gain some insight into the mechanism, we carried out several control experiments by using the substrates 1b, 3a, and TMSCN (Fig. 7). The target three-component reaction was completely inhibited, when stoichiometric radical scavenger 2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-1-piperidinyloxy (TEMPO) was introduced (Fig. 7a). Instead, the relevant TEMPO-adduct 12 was obtained in 76% yield, suggesting the possible involvement of acyl radical 3a–I in this process. Moreover, the reaction of radical clock substrate 13 having a cyclopropyl moiety also proceeded smoothly to give ring-opening product 14 in 64% yield with good stereoselectivity (Fig. 7b). These results indicated the intermediacy of radical species 13-A and 13-B, as well as the radical property of the reaction. Similar control experimental results were also observed in the case of cycloketone oxime ester-based asymmetric three-component reaction63.

Fig. 7. Mechanistic studies.

a Radical trapping experiment. b Radical clock experiment.

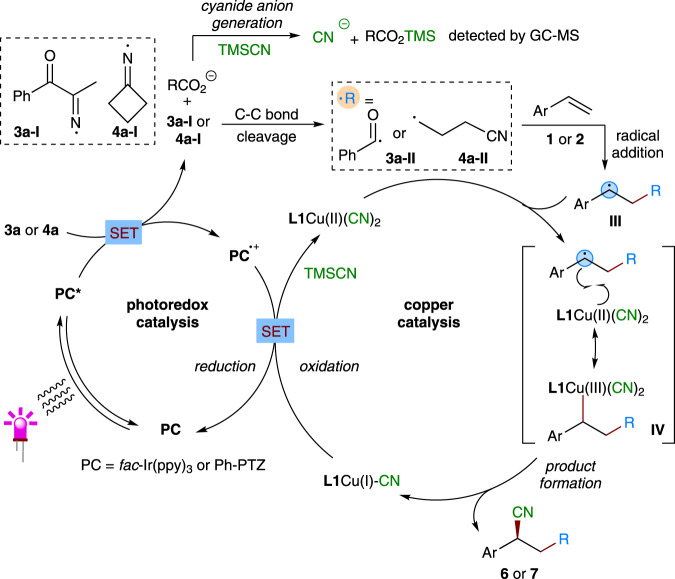

On the basis of these mechanistic studies and related literature19–21,45–48, we proposed a dual photoredox and copper-catalyzed mechanism for the present asymmetric three-component reaction as depicted in Fig. 8. The reaction starts with SET reduction of redox-active oxime esters 3a and 4a by the excited state photocatalyst to give iminyl radicals 3a–I and 4a–I, with release of carboxylic anion (RCO2−). Then, 3a–I and 4a–I undergoes C–C bond β-cleavage to form acyl and cyanoalkyl radicals 3a-II and 4a-II. Further facile trap of these carbon radicals by styrene derivatives 1 and 2 forms relatively more stable benzylic radicals III. On the other hand, the initially formed carboxylic anion (RCO2−) could also facilitate the ligand exchange between L1/copper(I) complex and TMSCN to form L1Cu(I)CN species. Such L1Cu(I)CN complex can further be oxidized by the oxidizing photocatalyst (PC•+) via a SET process, and undergoes another ligand exchange with TMSCN to form L1Cu(II)(CN)2 complex, regenerating ground-state photocatalyst to close the photoredox catalysis cycle. Finally, L1Cu(II)(CN)2 traps the prochiral benzylic radical III to form a chiral high-valent Cu(III) complex IV, which undergoes the reductive elimination to afford the coupled product 6 or 7, with regeneration of L1Cu(I)CN species to complete the copper catalysis cycle. It should be noted that an alternative process involving direct cyano transfer from the L1Cu(II)(CN)2 complex to the benzylic radical III through an outer-sphere pathway is also possible. Notably, the whole process is redox neutral and does not need any external stoichiometric oxidants or reductants.

Fig. 8. Proposed reaction mechanism.

SET single-electron transfer.

Discussion

In summary, we have developed an intermolecular, highly enantioselective three-component radical vicinal DCF reaction of alkenes, using oxime esters and TMSCN, by dual photoredox and copper catalysis. Key to the success of this protocol relies on chemoselective addition of acyl and cyanoalkyl radicals, generated in situ from the redox-active oxime esters by a photocatalytic N-centered iminyl radical-triggered C–C bond cleavage event, onto the alkenes to form new carbon radicals. Single-electron metalation of such carbon radicals to TMSCN-derived L1Cu(II)(CN)2 complex leads to asymmetric cross-coupling. This three-component reaction proceeds under mild conditions, and demonstrates broad substrate scope and high functional group tolerance, providing a general approach to optically active β–cyano ketones and alkyldinitriles. From a synthetic perspective, though the chiral products derived from acyclic ketone oxime esters can also be obtained by catalytic enantioselective conjugate addition strategies of cyanide to enones66–68, our three-component protocol provides a modular and generally applicable approach for the synthesis of structurally diverse chiral β–cyano ketones. Moreover, the products derived from cyclic ketone oxime esters cannot be easily synthesized by the previous methods. Many exciting extensions of this strategy to other radical precursors and nucleophiles can be envisaged; current investigations into these subjects are ongoing in our laboratory.

Methods

General procedure for the synthesis of products 6

In a flame-dried 10 mL Schlenk tube equipped with a magnetic stirrer bar was charged sequentially with Cu(CH3CN)4PF6 (0.56 mg, 0.0015 mmol) and chiral ligand L1 (0.80 mg, 0.00225 mmol), followed by the addition of DMA (2.5 mL). Then the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 30 min. To the resulting mixture were added 3 (0.30 mmol), 1 (0.10 mmol), and fac-Ir(ppy)3 (0.53 mg, 0.0008 mmol). Then, the resulting mixture was degassed (three times) under argon atmosphere. After that, TMSCN (0.3 mmol) was added into the mixture. At last, the mixture was stirred at a distance of ~1 cm from a 2 × 3 W purple LEDs at room temperature for 24 h until the reaction was completed, as monitored by TLC analysis. The reaction mixture was quenched with water (10 mL), diluted with EtOAc (3 × 10 mL), washed with NaCl (aq.), and dried over with anhydrous Na2SO4. After filtration and concentration, the residue was purified by silica gel chromatography affording the final products.

General procedure for the synthesis of products 7

In a flame-dried 10 mL Schlenk tube equipped with a magnetic stirrer bar was charged sequentially with Cu(CH3CN)4PF6 (0.001 mmol), chiral ligand L1 (0.0012 mmol), and organo-photocatalyst Ph-PTZ (0.0025 mmol), followed by the addition of DMA (4 mL). Then the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 30 min. To the resulting mixture were added 2 (0.20 mmol) and 4 (0.60 mmol). Then, the resulting mixture was degassed (three times) under argon atmosphere. After that, TMSCN (0.60 mmol) was added into the mixture. At last, the mixture was stirred at a distance of ~1 cm from a 2 × 3 W purple LEDs at room temperature 6 h until the reaction was completed, as monitored by TLC analysis. The reaction mixture was diluted with water (10 mL). The mixture was firstly extracted with EtOAc (3 × 10 mL), then washed with NaHCO3 (aq.; 15 mL), and finally washed with NaCl (aq.), dried over with anhydrous Na2SO4. After filtration and concentration, the residue was purified by silica gel chromatography afford the final products. Full experimental details and characterization of new compounds can be found in the Supplementary Methods.

Preprint

A previous version of this work was published as a preprint69.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 21971081, 91856119, 21772053, 21820102003, and 91956201), the Program of Introducing Talents of Discipline to Universities of China (111 Program, B17019), and the Excellent Doctoral Dissertation Cultivation Grant to P.Z.W. from CCNU.

Author contributions

P.-Z.W., Y.G., J.C. and X.-D.H. are responsible for the plan and implementation of the experimental work. J.-R.C. and W.-J.X. supervised the project and wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Data availability

The authors declare that the main data supporting the findings of this study, including experimental procedures and compound characterization, are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files. X-ray structural data of compounds 6bj and 7ja are available free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center under the deposition number CCDC 2047031 (6bj) and 2047032 (7ja). These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Wei Yu and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Peng-Zi Wang, Yuan Gao.

Contributor Information

Wen-Jing Xiao, Email: wxiao@mail.ccnu.edu.cn.

Jia-Rong Chen, Email: chenjiarong@mail.ccnu.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-021-22127-x.

References

- 1.Kolb HC, VanNieuwenhze MS, Sharpless KB. Catalytic asymmetric dihydroxylation. Chem. Rev. 1994;94:2483–2547. doi: 10.1021/cr00032a009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McDonald RI, Liu G, Stahl SS. Palladium(II)-catalyzed alkene functionalization via nucleopalladation: stereochemical pathways and enantioselective catalytic applications. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:2981–3019. doi: 10.1021/cr100371y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cresswell AJ, Eey ST, Denmark SE. Catalytic, stereoselective dihalogenation of alkenes: challenges and opportunities. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:15642–15682. doi: 10.1002/anie.201507152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luo Y-C, Xu C, Zhang X. Nickel-catalyzed dicarbofunctionalization of alkenes. Chin. J. Chem. 2020;38:1371–1394. doi: 10.1002/cjoc.202000224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tang S, Liu K, Liu C, Lei A. Olefinic C-H functionalization through radical alkenylation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015;44:1070–1082. doi: 10.1039/C4CS00347K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu Q, et al. Recent advances on palladium radical involved reactions. ACS Catal. 2015;5:6111–6137. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.5b01469. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crossley SWM, Obradors C, Martinez RM, Shenvi RA. Mn-, Fe-, and Co-catalyzed radical hydrofunctionalizations of olefins. Chem. Rev. 2016;116:8912–9000. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu L, Ward RM, Schomaker JM. Mechanistic aspects and synthetic applications of radical additions to allenes. Chem. Rev. 2019;119:12422–12490. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bao X, Li J, Jiang W, Huo C. Radical-mediated difunctionalization of styrenes. Synthesis. 2019;51:4507–4530. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1690987. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang H, Studer A. Intermolecular radical carboamination of alkenes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020;49:1790–1811. doi: 10.1039/C9CS00692C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qin T, et al. A general alkyl-alkyl cross-coupling enabled by redox-active esters and alkylzinc reagents. Science. 2016;352:801–805. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf6123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kischkewitz M, Okamoto K, Muck-Lichtenfeld C, Studer A. Radical-polar crossover reactions of vinylboron ate complexes. Science. 2017;355:936–938. doi: 10.1126/science.aal3803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garcia-Dominguez A, Li Z, Nevado C. Nickel-catalyzed reductive dicarbofunctionalization of alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:6835–6838. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b03195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu L, et al. Fe-catalyzed three-component dicarbofunctionalization of unactivated alkenes with alkyl halides and Grignard reagents. Chem. Sci. 2020;11:8301–8305. doi: 10.1039/D0SC02127J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campbell MW, Compton JS, Kelly CB, Molander GA. Three-component olefin dicarbofunctionalization enabled by nickel/photoredox dual catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:20069–20078. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b08282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chatgilialoglu, C. & Studer, A. (eds) Encyclopedia of Radicals in Chemistry, Biology and Materials (Wiley, 2012).

- 17.Sibi MP, Manyem S, Zimmerman J. Enantioselective radical processes. Chem. Rev. 2003;103:3263–3296. doi: 10.1021/cr020044l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lipp A, Badir SO, Molander G. Stereoinduction in metallaphotoredox catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021;60:1714–1726. doi: 10.1002/anie.202007668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang F, Chen P, Liu G. Copper-catalyzed radical relay for asymmetric radical transformations. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018;51:2036–2046. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Z-L, Fang G-C, Gu Q-S, Liu X-Y. Recent advances in copper-catalyzed radical-involved asymmetric 1,2-difunctionalization of alkenes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020;49:32–48. doi: 10.1039/C9CS00681H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gu Q-S, Li Z-L, Liu X-Y. Copper(I)-catalyzed asymmetric reactions involving radicals. Acc. Chem. Res. 2020;53:170–181. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.9b00381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang D, Zhu N, Chen P, Lin Z, Liu G. Enantioselective decarboxylative cyanation employing cooperative photoredox catalysis and copper catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;44:15632–15635. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b09802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang F, et al. Enantioselective copper-catalyzed intermolecular cyanotrifluoromethylation of alkenes via radical process. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:15547–15550. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b10468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou S, et al. Copper-catalyzed asymmetric cyanation of alkenes via carbonyl-assisted coupling of alkyl-substituted carbon-centered radicals. Org. Lett. 2020;22:6299–6303. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.0c02085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang G, et al. Asymmetric coupling of carbon‐centered radicals adjacent to nitrogen: copper‐catalyzed cyanation and etherification of enamides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020;59:20439–20444. doi: 10.1002/anie.202008338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu L, et al. Asymmetric Cu-catalyzed intermolecular trifluoromethylarylation of styrenes: enantioselective arylation of benzylic radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:2904–2907. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b13299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu L, Wang F, Chen P, Liu G. Enantioselective construction of quaternary all-carbon centers via copper-catalyzed arylation of tertiary carbon-centered radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:1887–1892. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b13052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fu L, Zhou S, Wan X, Chen P, Liu G. Enantioselective trifluoromethylalkynylation of alkenes via copper-catalyzed radical relay. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:10965–10969. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b07436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhuang W, Chen P, Liu G. Enantioselective arylcyanation of styrenes via copper‐catalyzed radical relay. Chin. J. Chem. 2021;39:50–54. doi: 10.1002/cjoc.202000494. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lei G, Zhang H, Chen B, Xu M, Zhang G. Copper-catalyzed enantioselective arylalkynylation of alkenes. Chem. Sci. 2020;11:1623–1628. doi: 10.1039/C9SC04029C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin J-S, et al. Cu/chiral phosphoric acid-catalyzed asymmetric three-component radical-initiated 1,2-dicarbofunctionalization of alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:1074–1083. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b11736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dong X-Y, et al. Copper-catalyzed asymmetric radical 1,2-carboalkynylation of alkenes with alkyl halides and terminal alkynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020;142:9501–9509. doi: 10.1021/jacs.0c03130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dong X-Y, et al. Copper‐catalyzed asymmetric coupling of allenyl radicals with terminal alkynes to access tetrasubstituted allenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021;60:2160–2164. doi: 10.1002/anie.202013022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Albini, A. & Fagnoni, M. (eds) Photochemically Generated Intermediates in Synthesis (Wiley, 2013).

- 35.Prier CK, Rankic DA, MacMillan DWC. Visible light photoredox catalysis with transition metal complexes: applications in organic synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2013;113:5322–5363. doi: 10.1021/cr300503r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marzo L, Pagire SK, Reiser O, Konig B. Visible‐light photocatalysis: does it make a difference in organic synthesis? Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018;57:10034–10072. doi: 10.1002/anie.201709766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Crisenza GEM, Mazzarella D, Melchiorre P. Synthetic methods driven by the photoactivity of electron donor-acceptor complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020;142:5461–5476. doi: 10.1021/jacs.0c01416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garbarino S, Ravelli D, Protti S, Basso A. Photoinduced multicomponent reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:15476–15484. doi: 10.1002/anie.201605288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Courant T, Masson G. Recent progress in visible-light photoredox-catalyzed intermolecular 1,2-difunctionalization of double bonds via an ATRA-type mechanism. J. Org. Chem. 2016;81:6945–6952. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.6b01058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pantaine, L., Bour, C. & Masson, G. Photochemistry Vol. 46, 395–431 (Royal Society of Chemistry, 2019).

- 41.Silvi M, Melchiorre P. Enhancing the potential of enantioselective organocatalysis with light. Nature. 2018;554:41–49. doi: 10.1038/nature25175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang H-H, Chen H, Zhu C, Yu S. A review of enantioselective dual transition metal/photoredox catalysis. Sci. China Chem. 2020;63:637–647. doi: 10.1007/s11426-019-9701-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rigotti T, Alemán J. Visible light photocatalysis – from racemic to asymmetric activation strategies. Chem. Commun. 2020;56:11169–11190. doi: 10.1039/D0CC03738A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zheng D, Studer A. Asymmetric synthesis of heterocyclic gamma-amino-acid and diamine derivatives by three-component radical cascade reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019;58:15803–15807. doi: 10.1002/anie.201908987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu XY, Zhao QQ, Chen J, Xiao WJ, Chen JR. When light meets nitrogen-centered radicals: from reagents to catalysts. Acc. Chem. Res. 2020;53:1066–1083. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yu X-Y, et al. A visible-light-driven iminyl radical-mediated C-C single bond cleavage/radical addition cascade of oxime esters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018;57:738–743. doi: 10.1002/anie.201710618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yu XY, Zhao QQ, Chen J, Chen JR, Xiao WJ. Copper-catalyzed radical cross-coupling of redox-active oxime esters, styrenes, and boronic acids. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018;57:15505–15509. doi: 10.1002/anie.201809820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen J, et al. Enantioselective radical ring-opening cyanation of oxime esters by dual photoredox and copper catalysis. Org. Lett. 2019;21:9763–9768. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b03970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xiao T, Huang H, Anand D, Zhou L, Iminyl-radical-triggered C–C. bond cleavage of cycloketone oxime derivatives: generation of distal cyano-substituted alkyl radicals and their functionalization. Synthesis. 2020;52:1585–1601. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1690844. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Song C, Shen X, Yu F, He Y-P, Yu S. Generation and application of iminyl radicals from oxime derivatives enabled by visible light photoredox catalysis. Chin. J. Org. Chem. 2020;40:3748–3759. doi: 10.6023/cjoc202004008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhao B, Shi Z. Copper‐catalyzed intermolecular Heck‐like coupling of cyclobutanone oximes initiated by selective C−C bond cleavage. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017;56:12727–12731. doi: 10.1002/anie.201707181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dauncey EM, Morcillo SP, Douglas JJ, Sheikh NS, Leonori D. Photoinduced remote functionalisations by iminyl radical promoted C-C and C-H bond cleavage cascades. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018;57:744–748. doi: 10.1002/anie.201710790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fan X, Lei T, Chen B, Tung CH, Wu L-Z. Photocatalytic C-C bond activation of oxime ester for acyl radical generation and application. Org. Lett. 2019;21:4153–4158. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b01338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cheng Y-Y, et al. Visible light irradiation of acyl oxime esters and styrenes efficiently constructs β-carbonyl imides by a scission and four-component reassembly process. Org. Lett. 2019;21:8789–8794. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b03409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang T, et al. Enantioselective cyanation via radical-mediated C-C single bond cleavage for synthesis of chiral dinitriles. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:5373. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13369-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ruan L, Chen C, Zhang X, Sun J. Recent advances on the photo-induced reactions of acyl radical. Chin. J. Org. Chem. 2018;38:3155–3164. doi: 10.6023/cjoc201806009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Banerjee A, Lei Z, Ngai MY. Acyl radical chemistry via visible-light photoredox catalysis. Synthesis. 2019;51:303–333. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1610329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Raviola C, Protti S, Ravelli D, Fagnoni M. Photogenerated acyl/alkoxycarbonyl/carbamoyl radicals for sustainable synthesis. Green Chem. 2019;21:748–764. doi: 10.1039/C8GC03810D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chu X-Q, Ge D, Shen Z-L, Loh T-P. Recent advances in radical-initiated C(sp3)-H bond oxidative functionalization of alkyl nitriles. ACS Catal. 2017;8:258–271. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.7b03334. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wu W-B, Yu J-S, Zhou J. Catalytic enantioselective cyanation: recent advances and perspectives. ACS Catal. 2020;10:7668–7690. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.0c01918. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang Y, Du Y, Huang N. A survey of the role of nitrile groups in protein-ligand interactions. Future Med. Chem. 2018;10:2713–2728. doi: 10.4155/fmc-2018-0252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lopez R, Palomo C. Cyanoalkylation: alkylnitriles in catalytic C-C bond‐forming reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:13170–13184. doi: 10.1002/anie.201502493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hayrapetyan D, Khalimon AY. Catalytic nitrile hydroboration: a route to N,N‐diborylamines and uses thereof. Chem. Asian. J. 2020;15:2575–2587. doi: 10.1002/asia.202000672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yang S, et al. Copper-catalyzed asymmetric aminocyanation of arylcyclopropanes for synthesis of γ-amino nitriles. ACS Catal. 2019;9:716–721. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.8b03768. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Long J, Yu R, Gao J, Fang X. Access to 1,3-dinitriles by enantioselective auto-tandem catalysis: merging allylic cyanation with asymmetric hydrocyanation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020;59:6785–6789. doi: 10.1002/anie.202000704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tanaka Y, Kanai M, Shibasaki M. A catalytic enantioselective conjugate addition of cyanide to enones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:6072–6073. doi: 10.1021/ja801201r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kurono N, Ohkuma T. Catalytic asymmetric cyanation reactions. ACS Catal. 2016;6:989–1023. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.5b02184. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zheng K, Liu X, Feng X. Recent advances in metal-catalyzed asymmetric 1,4-conjugate addition (ACA) of nonorganometallic nucleophiles. Chem. Rev. 2018;118:7586–7656. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang, P.-Z. et al. Asymmetric three-component olefin dicarbofunctionalization enabled by photoredox and copper dual catalysis. Preprint at ChemRxiv10.26434/chemrxiv.13325669.v1 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that the main data supporting the findings of this study, including experimental procedures and compound characterization, are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files. X-ray structural data of compounds 6bj and 7ja are available free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center under the deposition number CCDC 2047031 (6bj) and 2047032 (7ja). These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.