Abstract

Aim

The objective of this study was to describe social inequities in cardiovascular risk factors in women and men by autonomous regions in Spain.

Methods

We used data from 20,406 individuals aged 18 or older from the 2017 Spanish National Health Survey. We measured socioeconomic position using occupational social class and used data on self-reported cardiovascular risk factors: high cholesterol, diabetes, hypertension, obesity, and smoking. We estimated Relative Risk of Inequality (RII) using Poisson regression models. Analyses were stratified by men and women and by region (Autonomous Communities).

Results

Overall, the RRI was 1.02, 1.13, 1.06, 1.17 and 1.09 for high cholesterol, diabetes, hypertension, obesity, and current smoking, respectively. Ocuupational social class inequities in diabetes, hypertension, and obesity was stronger for women. Results showed a large regional heterogeneity in these inequities; some regions (e.g. Asturias and Balearic Islands) presented wider social inequities in cardiovascular risk factors than others (e.g. Galicia, Navarra or Murcia).

Conclusion

In Spain, we found marked social inequities in the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors, with wide regional and women/men heterogeneity in these inequities. Education, social, economic and health policies at the regional level could reduce health inequities in cardiovascular risk factors and, thus, prevent cardiovascular disease.

Keywords: epidemiology, cardiovascular risk factors, social determinants of health, health inequities, health disparities

RESUMEN

Objetivo

El objetivo de nuestro trabajo fue describir las desigualdades sociales en factores de riesgo cardiovascular en hombres y mujeres por Comunidad Autónoma en España.

Método

Los sujetos de estudio fueron 20.406 personas de 18 años o mayores que participaron en la Encuesta Nacional de Salud de 2017. Como medida de posición socioeconómica, se utilzó la clase social ocupacional, y se tomaron medidas auto-reportadas de factores de riesgo cardiovascular: hipercolesterolemia, diabetes, hipertensión, obesidad, y tabaquismo. Estimamos el Índice Relativo de Desigualdad (IRR) usando modelos de regresión de Poisson. Los análisis fueron estratificados por mujeres y hombres y por Comunidad Autónoma.

Resultados

El IRR fue de 1.02, 1.13, 1.06, 1.17 y 1.09 para hipercolesterolemia, diabetes, hipertensión, obesidad y tabaquismo, respectivamente. Las desigualdades por clase social ocupacional en diabetes, hipertensión y obesidad fueron más altas en mujeres. Se mostró una alta heterogeneidad en éstas desigualdades; algunas Comunidades Autónomas (p.ej. Asturias y las Islas Baleares) presentan IRR más altas en factores de riesgo cardiovascular que otras (p.ej. Galicia, Navarra o Murcia).

Conclusiones

En España encontramos marcadas desigualdades sociales en la prevalencia de factores de riesgo cardiovascular, con gran heterogeneidad por mujeres y hombres y por Comunidad Autónoma. Las políticas eductivas, sociales, económicas y de salud a nivel de Comunidad Autónoma podrían reducir las desigualdades sociales en factores de riesgo cardiovascular y, por tanto, prevenir enfermedades cardiovasculares.

Palabras clave: epidemiología, factores de riesgo cardiovascular, determinantes sociales de la salud, desigualdades sociales en salud, diferencias en salud

INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) are the leading cause of death in developing and developed nations1, and the social, medical, and economic burden of CVD is likely to increase over the next decades worldwide1. In Spain, there were 210,618 new cases of CVD in men and 220,957 in women in 20152.

The prevention of CVD requires a combination of population and individual-level approaches3, but very little research in CVD prevention in Spain has leveraged population approaches4. An understanding of social factors that influence CVD is key to designing and implementing these approaches. Socioeconomic position, as measured by several indicators including race, education, income, and social class, has been associated with CVD in several studies5-7. Importantly, inequities in CVD may be a reflection of similar inequities in CVD risk factors8, which may be more tractable and amenable to interventions to prevent the development of CVD. In Spain, there is evidence of unequal exposure to CVD risk factors such as smoking9, high blood pressure10, high cholesterol10, diabetes11 or obesity12 by socioeconomic status, along with higher mortality in people with established CVD and lower income13. However, very few of these studies have been conducted in nationally representative samples.

The pathway between socioeconomic position and CVD risk factors might be different for each risk factor. For instance, inequities in diabetes, blood pressure and high cholesterol may be moderated by inequities in obesity14 or by inequities in treatment and control15. Some of these social inequities in CVD are heterogeneous by gender, in a phenomenon called intersectionality. For instance, the educational social gradient in smoking prevalence in Spain varies greatly by gender, and this variation has evolved through time9.

Despite the mounting evidence regarding the role of socioeconomic position and cardiovascular health in different settings, there is scarce information on studies looking at the sub-national heterogeneity in these. This is specially important in countries like Spain, which has a territorial organization with markedly autonomous regional governments (Autonomous Communities) with legislative power over numerous social welfare aspects, including healthcare and education. This territorial organization warrants the possibility to explore heterogeneity in aspects related to social and health inequities. Understanding which regions have wider inequities can be a powerful advocacy tool for improved, more egalitarian health promotion and disease prevention policies in those regions.

The objective of this study was to describe social inequities in cardiovascular risk factors in women and men by autonomous regions in Spain.

METHODS

Study population

We used data from the 2017 Spanish National Health Survey (n=23,089). We excluded participants from the Autonomous Cities of Ceuta and Melilla (N=255 and 281 respectively) due to low sample sizes, those aged <18 (N=538), and those with missing values in social class (N=579), high cholesterol (N=36), diabetes (N=12), hypertension (N=28), obesity (N=955) or smoking (N=18), leaving a final analytic sample of 20,406 individuals (10712 women, and 9694 men). Additional information about the sampling strategy and interview details of the Spanish National Health Survey can be found elsewhere16.

Exposures

We used occupational social class as our main measure of socioeconomic position. Survey participants were asked about their past or current occupation, which was then classified using the Spanish version of the International Standard Classification of Occupations17. Each occupation was assigned to a social class category, as suggested by Domingo-Salvany et al18: (I) Higher grade professionals, administrators, and officials; managers in large industrial establishments; (II) Lower grade professionals, administrators, and officials; higher grade technicians; managers in small industrial establishments; sportspeople and artists; (III) Intermediate occupations and own-account workers; (IV) Lower supervisory and technical occupations; (V) Skilled workers in primary production and other semi-skilled workers; (VI) Non-skilled workers.

In sensitivity analyses, we used education and household income as alternative proxies of socioeconomic position. Education was defined as the highest level of education achieved, and classified as: university degree or equivalent; advanced professional school; mid-level professional school; complete high school; first stage of secondary education complete; complete primary Education; incomplete primary education; and can’t read or write. Income was measured as monthly net household income (in euros), and classified as: ≥6000; 4500-5999; 3600-4499; 2700-3599; 2200-2699; 1800-2199; 1550-1799; 1300-1549; 1050-1299; 800-1049; 570-799; and <570 € per month.

Outcomes

We used data on 5 modifiable cardiovascular risk factors: high cholesterol, diabetes, hypertension, obesity, and current smoking. High cholesterol, diabetes, and hypertension were defined as someone who answered “Yes” to at least one of the questions “Have you ever suffered from…?” and “Has your doctor ever tell you that you suffer from… diabetes/high blood pressure/high cholesterol?”, respectively. Obesity was defined as a body mass index (BMI) ≥30 kg/m2; height and weight were self-reported. Individuals were classified as current smokers if they answered “Yes, daily” or “Yes, but not daily” to the question “Are you a current smoker?”.

Covariates

Data on age (in years), gender (women or men), and region (Autonomous Community) were self-reported.

Statistical analyses

First, we performed a descriptive analysis of sociodemographic characteristics and cardiovascular risk factors calculating survey-weighted means and proportions of continuous and categorical variables, respectively, overall and for women/men. We performed t-test (for continuous variables) and chi2 tests (for categorical variables) for women/men taking into account survey weights and stratification. We also described the distribution of occupational social class and each of the outcomes by Autonomous Community.

We calculated the Relative Index of Inequality (RII)19 by estimating prevalence ratios (PRs) of each of the 5 cardiovascular risk factors for occupational class; we used Poisson regression models with robust standard errors, acknowledging the complex survey structure by including weights and stratification using R survey package. Social class was treated as an ordinal variable after exploratory analysis revealing a log-linear dose-response between risk factors and social class. RIIs above one indicate higher inequity, while RIIs below one indicate inverse social gradient. All models were adjusted for age and squared age and were for women/men by introducing an interaction term between social class and women/men. To assess regional differences in these associations, we then ran the same model for each of the 17 Autonomous Communities. We displayed RIIs for each risk factor-region-women/men combination. In sensitivity analyses, we estimated absolute prevalence differences by social class with the Slope Index of Inequality (SII)19, and repeated the analyses by Autonomous Community using education and household income as exposure variables. We conducted all analyses and plots with R V3.5.1.

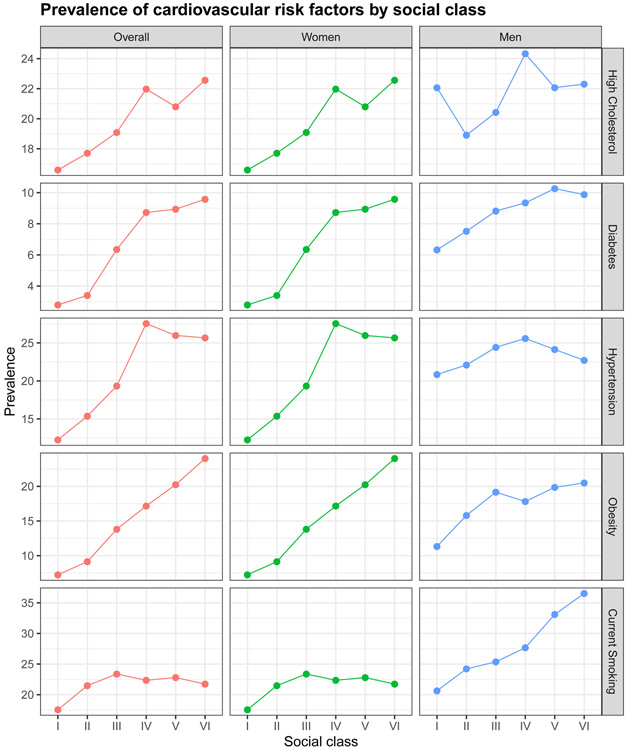

RESULTS

Table 1 describes the sociodemographic characteristics and prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in the sample. Mean age was 49.55 years, slightly higher in women (50.09) than in men (48.99). Approximately 11%, 8%, 19%, 15%, 34%, and 14% of participants belonged to social classes I through VI, respectively. These distributions were similar in men and women, with a higher proportion of women belonging to social class IV (lower supervisory and technical occupations) and a higher proportion of men belonging to social class VI (non-skilled workers). The prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors was: 24% for high cholesterol, 10% for diabetes, 27% for hypertension, 18% for obesity, and 24% for smoking. Men had a higher prevalence of smoking and obesity as compared to women (28% vs 21%, and 19% vs 17%). Supplementary tables I and II show the distribution of occupational social class and cardiovascular risk factors by Autonomous Community respectively. Figure 1 shows the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors by social class categories, where there was a linear dose-response relationship between occupational class and each of the risk factors. Supplementary file III shows the prevalence also stratified by age.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the participants (aged ≥18) from the Spanish National Health Survey (N=20,406)

| Individual characteristics1 | Total | Women | Men | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N=20406) | (N=10712) | (N=9694) | |||||

| Age (years), mean SD | 49.55 | 17.6 | 50.09 | 18.0 | 48.99 | 17.2 | <0.001 |

| Social class | |||||||

| I.Higher grade professionals, administrators and officials; managers in large industrial establishments | 2164 | 10.6% | 1109 | 10.4% | 1055 | 10.9% | 0.708 |

| II. Lower grade professionals, administrators and officials; higher grade technicians; managers in small industrial establishments; sportpeople and artists | 1577 | 7.7% | 839 | 7.8% | 738 | 7.6% | 0.625 |

| III. Intermediate occupations and own account workers | 3879 | 19.0% | 2104 | 19.6% | 1775 | 18.3% | 0.256 |

| IV. Lower supervisory and technical occupations | 3012 | 14.8% | 1393 | 13.0% | 1619 | 16.7% | <0.001 |

| V. Skilled workers workers in primary production and other semi-skilled workers | 6898 | 33.8% | 3574 | 33.4% | 3324 | 34.3% | 0.811 |

| VI. Non-skilled workers | 2876 | 14.1% | 1693 | 15.8% | 1183 | 12.2% | <0.001 |

| High cholesterol | 4937 | 24.2% | 2548 | 23.8% | 2389 | 24.6% | 0.006 |

| Diabetes | 1986 | 9.7% | 921 | 8.6% | 1065 | 11.0% | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 5601 | 27.4% | 2873 | 26.8% | 2728 | 28.1% | 0.054 |

| Obesity | 3693 | 18.1% | 1861 | 17.4% | 1832 | 18.9% | 0.027 |

| Current smoker | 4972 | 24.4% | 2280 | 21.3% | 2692 | 27.8% | <0.001 |

Reported as n (%) unless specified. P-values correspond to t-test (for continuous variables) and chi2 tests (for categorical variables) by women/men. All statistical tests accounted for complex survey structure by including weights and stratification.

Figure 1. Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors by social class categories, overall, in women and men.

Social class classification: (I) Higher grade professionals, administrators, and officials; managers in large industrial establishments; (II) Lower grade professionals, administrators and officials; higher grade technicians; managers in small industrial establishments; sportspeople and artists; (III) Intermediate occupations and own-account workers; (IV) Lower supervisory and technical occupations; (V) Skilled workers in primary production and other semi-skilled workers; (VI) non-skilled workers

Table 2 shows the RII of cardiovascular risk factors for the entire Spanish territory. Overall, the RII was statistically significant for all risk factors; it was lowest for high cholesterol (RII=1.02; 95%CI 1.00-1.04), and highest for obesity (RII=1.16; 95%CI 1.12-1.19) and diabetes (RII=1.13; 95%CI 1.10-1.17). RIIs of diabetes, hypertension, and obesity were higher for women (interaction p=0.01, p<0.001, and p<0.001, respectively), while inequities in current smoking were stronger for men (interaction p<0.001).

Table 2.

Associations between social class (1-category decrease in social class) and cardiovascular risk factors prevalence. Model acknowledged the complex survey structure by including weights and stratification.

| Total | Women | Men | Interaction | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RII | CI 95% | RII | CI 95% | RII | CI 95% | p-value | |

| High Cholesterol | 1.02 | 1.00 ; 1.04 | 1.03 | 1.01 ; 1.06 | 1.01 | 0.99 ; 1.04 | 0.391 |

| Diabetes | 1.13 | 1.10 ; 1.17 | 1.20 | 1.14 ; 1.26 | 1.08 | 1.03 ; 1.13 | 0.010 |

| Hypertension | 1.06 | 1.04 ; 1.08 | 1.11 | 1.08 ; 1.13 | 1.02 | 0.99 ; 1.04 | <0.001 |

| Obesity | 1.16 | 1.14 ; 1.19 | 1.25 | 1.20 ; 1.29 | 1.10 | 1.06 ; 1.13 | <0.001 |

| Current Smoking | 1.09 | 1.07 ; 1.11 | 1.05 | 1.02 ; 1.08 | 1.13 | 1.10 ; 1.16 | <0.001 |

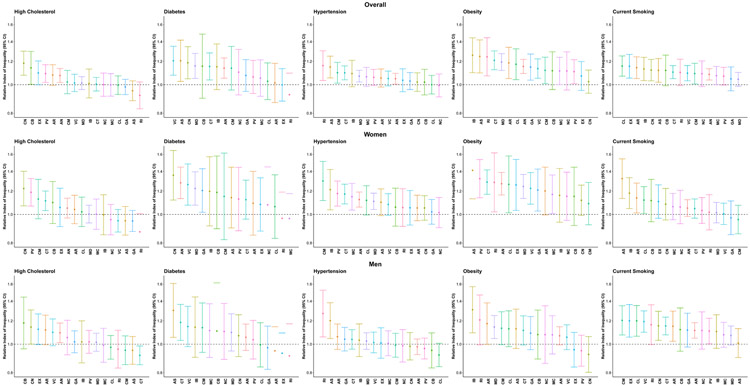

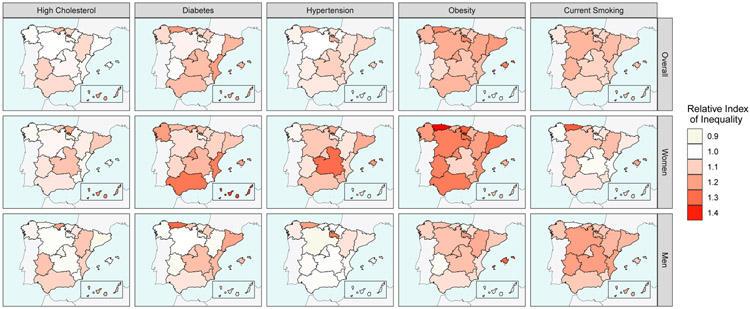

Figures 2 and 3 display the RIIs for each Spanish region. Regions with a RII further above from one are regions with wider health inequities. We observed heterogeneity by region and by women/men in the RIIs of cardiovascular risk factors by social occupational social class. In general, some regions (e.g. Asturias and Balearic Islands) presented higher RII than others (e.g. Galicia, Navarra or Murcia). For high cholesterol, Canarias had the highest RII overall and for women, and the second highest in men. In men, Catalunya had the lowest RII (RII=0.90), meaning that, for each 1-unit decrease in social class, the prevalence of high cholesterol decreases by 10%. For diabetes, RII tend to be higher in women; the regions with the highest RII were Comunitat Valenciana and Asturias. For hypertension, the RII ranged from 1.23 to 0.91, the highest being Castilla la Mancha (women), and La Rioja (men). Obesity had the highest RII of all risk factors, specially in women; for instance, women in Asturias had a RII of 1.41 (95% CI 1.13-1.76). For smoking, there was greater regional variability in RII for women (from 1.32 in Asturias to 0.94 in Castilla la Mancha) than men.

Figure 2. Regional heterogeneity in the the Relative Index of Inequality (RII) for high cholesterol, diabetes, hypertension, obesity and current smoking, sorted by RII.

Autonomous Communities: AN=Andalucia; AR=Aragon; AS=Asturias; IB=Balearic Islands; CN=Cannary Islands; CB=Cantabria; CL=Castilla y Leon; CM=Castilla la Mancha; CT=Catalonia; VC=Comunidad Valenciana; EX=Extramadura; GA=Galicia; MD=Madrid; MC=Murcia; NC=Navarra; PV=Basque Country; RI=La Rioja

Figure 3.

Map showing the spatial heterogeneity in the Relative Index of Inequality (RII) for high cholesterol, diabetes, hypertension, obesity and current smoking.

Supplementary files IV and V show the sensitivity analysis using the Slope Index of Inequality (SII), with similar results between the relative and the absolute measures in women and men. We also repeated the analysis by Autonomous Community changing the exposure to education (supplementary file VI) and household income (supplementary file VII), showing similar inferences as the main analysis.

DISCUSSION

We found strong inequities in cardiovascular risk factor prevalence by occupational social class in Spain: individuals of disadvantaged social class presented a higher prevalence of high cholesterol, diabetes, hypertension, obesity, and smoking, independent of age. Moreover, we found that social inequities in diabetes, hypertension, and obesity were stronger in women as compared to men, while the inequities in smoking were stronger in men as compared to women. Lastly, we found heterogeneity by region (Autonomous Communities), with some regions (e.g. Asturias and Balearic Islands) presenting wider social inequities in cardiovascular risk factors than others (e.g. Galicia, Navarra or Murcia).

Social inequities in cardiovascular risk factors by occupational social class and other measures of socioeconomic position have been reported previously in Spain10,12. Previous studies have reported inequities in cholesterol in Spain10; however, our results were modest and modified by age; as seen in supplementary material 3, in those <40, there was an inverse social gradient in high cholesterol that might reflect less frequent visits to healthcare providers. Social inequities in diabetes prevalence have been reported in Spain before20, and they might be moderated partially by inequities in obesity14. Regarding hypertension, Regidor et al21 found that the highest prevalence of hypertension was seen in subjects of disadvantaged occupational social class. Obesity inequities have been also found previously in Spain22; probably due to differences in the intermediate determinants of health (food availability and affordability, walkability), as well as the impact of marketing of unhealthy products, such as cars or fast food. Also, inequities by social class in smoking have been described before23, with a strong cohort effect and gender intersectionality. Our results were mostly consistent in the sensitivity analyses by education and household income, as another previous study showed12.

The RII for diabetes, hypertension, and obesity was stronger in women compared to men. The excess risk of CVD associated with disadvantaged socioeconomic position is greater for women compared to men24, potentially mediated by differences in risk factors7. Specifically, in Spain education inequities in CVD mortality are higher in women than in men25. Nonetheless, we also found that inequities in smoking were higher in men compared to women, consistent with pervious studies showing cohort effects in the association between socioeconomic status and smoking by gender, as the social inequity in smoking for women has only emerged in the last few decades9. Previous studies have found that absolute measures of inequity in diabetes mortality might be higher in men, and that relative measures are higher for women26; however, in our study, both absolute and relative measures were consistent. All of these observations lend support to the idea of considering the intersectionality of class and gender when studying and designing prevention strategies aiming to reduce health inequities27. Also, it should be noted that social inequities vary by age, with wider gaps in older ages (as seen in Supplementary File 3), as consistent with other studies10, and a complex relationship with gender in the case of smoking, also consistent with previous studies9.

We observed variation across Spanish Autonomous Communities in the magnitude of social inequities in cardiovascular risk factors. Previous studies have shown variability in social inequities in health between countries28. However, the information on sub-national heterogeneity of social inequities in health is scarce29. There might be many reasons, both in context and composition of Autonomous Communities, that could explain the regional variability in social inequities in CVD risk factors observed in our study.

Regarding differences in context, Mackenbach et al. suggested in a study of social inequities in 22 European countries28 that such regional differences might be a reflection of regional differences in educational opportunities, income distribution, or access to health care. This is a key policy issue in Spain, where education or health care competencies are decentralized at the regional (Autonomous Communities) level. In fact, Costa-Font et al29 analyzed determinants of health inequities between 1980-2001 in Spain and found that regional self-reported health status inequities appeared to be driven by income regional inequities, but not by differences in funding or health expenditure between Autonomous Communities. Nonetheless, health care competencies to the Autonomous Communities were not completely transferred until 2002, which was after the study period of the Costa-Font et al study. Access to healthcare might explain inequities in specific groups, such as undocumented migrants, as there are differences between Autonomous Communities in how their right to access healthcare is guaranteed30; however, it is not likely that this population is well-represented in the Spanish National Health Survey. Also, differences in health care might explain better the heterogeneity in inequities in blood pressure and cholesterol, which may be driven partially by screening inequities by socioeconomic position31. Moreover, public health policies and interventions aiming to improve health equity also might vary between Spanish regions; in fact, Borrell et al32 reviewed in 2005 all Autonomous Community-level health plans in Spain and found that the Basque Country was the Autonomous Community that had the most recognition for health equity in their plans. However, there is no comprehensive information and evaluation of the impact of public health programs on health equity. An additional contextual explanation might be the presence of non-health interventions that impact health equity, such as neighborhood and urban interventions. For instance, in Catalonia, the urban renewal intervention known as the Neighborhood Law (Llei de Barris), seemed to prevent poor mental health increases in both sexes and especially among the lowest social classes33. Regarding differences in composition, there is the possibility that there are differences in who gets to be in advantaged vs disadvantaged occupation social classes in the different regions. For instance, migrants tend to be of more disadvantaged social class34 and these populations have different cardiovascular risk profiles than local populations35; therefore, regions with a greater proportion of migrant residents might present different health inequities by social class. Catalunya, Murcia, Balearic Islands, and Madrid are the regions with more non-EU migrant residents (11.26%, 11.20%, 9.57%, and 8.85%, respectively36); however, these regions don’t have clearly higher or lower inequities in our study. Also, the length of stay should be taken into account as health status of migrants may vary by length of stay in the host country37. Future studies should test how regional characteristics (both contextual and compositional) could explain the heterogeneity of health inequities between regions.

We acknowledge that this study presents several limitations. First, this a descriptive cross-sectional study, so we cannot infer causality; however, the results of the study are consistent with previous findings, both in Spain and other countries. Second, caradiovascular risk factors measures were based on self-reported measures on previous diagnoses, which could introduce information bias; nevertheless, data on self-reported cardiovascular risk factors are a widely used cost-effective method for population health studies. Moreover, validity of health surveys might not vary by socioeconomic position38. Third, there might different use by social class in health care use which can bias knowledge about cardiovascular risk factors; however, the direction of the potential bias is difficult to estimate; on the one hand, people of disadvantaged social class in Spain visit general practitioners more frequently; on the other hand, men and women of advantaged social position use private health care services more frequently where they can have screening of cardiovascular risk factors39. Additionally, previous studies have shown that under-diagnosis of some cardiovascular risk factors, such as diabetes, might not follow a social gradient40. Last, we did not test for the mechanisms by which the regional differences are present, although we have attempted to discuss some of the key potential mechanisms involved. Future studies should look at these mechanisms.

This study may have important implications. Social class reflects experiences and exposures during the life course, representing access to material resources relevant for health, as well as aspects relevant to job characteristics, such as environmental exposures or physical risks. In this study, we found that social inequities in cardiovascular risk factors varied between regions. Autonomous Communities in Spain have political control over relevant aspects such as education or health; thus, encouraging social policies and strong cardiovascular preventive actions at the regional level may be effective equitable population prevention strategy3.

In conclusion, we found social inequities in the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors among the adult population in Spain. Individuals of disadvantaged social class showed a higher prevalence of high cholesterol, diabetes, hypertension, obesity, and smoking, as compared to individuals of higher social class. These social inequities were generally larger for women than for men calling for an intersectional approach between gender and social class. Also, we found heterogeneity by Autonomous Community with some presenting wider social inequities than others. Education, social, economic, and health policies at the regional level could reduce health inequities in cardiovascular risk factors and, thus, prevent cardiovascular diseases.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank all the participants of the Spanish National Health Survey as well as all the workers of the National Statistics Institute (INE) for making this research possible.

FUNDING

PG was supported by the 2018 Alfonso Martín Escudero Research Grant. UB was supported by the Office of the Director of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number DP5OD26429

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The Authos declare that there is no conflict of interest

REFERENCES

- 1.Beaglehole R, Bonita R. Global public health: a scorecard. Lancet. 2008;372:1988–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Timmis A, Townsend N, Gale C, et al. European Society of Cardiology: Cardiovascular disease statistics 2017. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:508–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rose G Sick Individuals and Sick Populations. Int J Epidemiol. 1985;14:32–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Franco M, Bilal U, Guallar E, et al. Systematic review of three decades of Spanish cardiovascular epidemiology: improving translation for a future of prevention. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2013. August 13;20:565–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Safford MM, Brown TM, Muntner PM, et al. Association of Race and Sex With Risk of Incident Acute Coronary Heart Disease Events. JAMA. 2012. November 7;308:1768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manrique-Garcia E, Sidorchuk A, Hallqvist J, et al. Socioeconomic position and incidence of acute myocardial infarction: A meta-analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65:301–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McFadden E, Luben R, Wareham N, et al. Occupational social class, risk factors and cardiovascular disease incidence in men and women: A prospective study in the European Prospective Investigation of Cancer and Nutrition in Norfolk (EPIC-Norfolk) cohort. Eur J Epidemiol. 2008;23:449–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferrario MM, Veronesi G, Kee F, et al. Determinants of social inequalities in stroke incidence across Europe: a collaborative analysis of 126 635 individuals from 48 cohort studies. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2017. December;71:1210–1216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bilal U, Beltrán P, Fernández E, et al. Gender equality and smoking: A theory-driven approach to smoking gender differences in Spain. Tob Control. 2016;25:295–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.López-González ÁA, Bennasar-Veny M, Tauler P, et al. Desigualdades socioeconómicas y diferencias según sexo y edad en los factores de riesgo cardiovascular. Gac Sanit. 2015. January;29:27–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bilal U, Hill-Briggs F, Sánchez-Perruca L, et al. Association of neighbourhood socioeconomic status and diabetes burden using electronic health records in Madrid (Spain): the HeartHealthyHoods study. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e021143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pérez-Hernández B, García-Esquinas E, Graciani A, et al. Social Inequalities in Cardiovascular Risk Factors Among Older Adults in Spain: The Seniors-ENRICA Study. Rev Española Cardiol. 2017;70:145–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cainzos-Achirica M, Capdevila C, Vela E, et al. Individual income, mortality and healthcare resource use in patients with chronic heart failure living in a universal healthcare system: A population-based study in Catalonia, Spain. Int J Cardiol. 2019;277:250–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Espelt A, Borrell C, Palència L, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in the incidence and prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus in Europe. Gac Sanit. 2013;27:494–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sivén SS, Niiranen TJ, Aromaa A, et al. Social, lifestyle and demographic inequalities in hypertension care. Scand J Public Health. 2015. May 27;43:246–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Encuesta Nacional de Salud de España 2017. 2018. [cited 2019 May 1]. Available from: https://www.mscbs.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/encuestaNacional/encuesta2017.htm

- 17.Connelly R, Gayle V, Lambert PS. A Review of occupation-based social classifications for social survey research. Methodol Innov. 2016;9:205979911663800. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Domingo-Salvany A, Bacigalupe A, Carrasco JM, et al. Propuestas de clase social neoweberiana y neomarxista a partir de la Clasificación Nacional de Ocupaciones 2011. Gac Sanit. 2013;27:263–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Regidor E Measures of health inequalities: Part 2. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58:900–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Espelt A, Kunst AE, Palència L, et al. Twenty years of socio-economic inequalities in type 2 diabetes mellitus prevalence in Spain, 1987-2006. Eur J Public Health. 2012;22:765–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Regidor E, Gutiérrez-Fisac JL, Banegas JR, et al. Association of adult socioeconomic position with hypertension in older people. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60:74–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Merino Ventosa M, Urbanos-Garrido RM. Disentangling effects of socioeconomic status on obesity: A cross-sectional study of the Spanish adult population. Econ Hum Biol. 2016;22:216–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bacigalupe A, Esnaola S, Martín U, et al. Two decades of inequalities in smoking prevalence, initiation and cessation in a southern European region: 1986-2007. Eur J Public Health. 2013;23:552–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Backholer K, Peters SAE, Bots SH, et al. Sex differences in the relationship between socioeconomic status and cardiovascular disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2017;71:550–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haeberer M, León-Gómez I, Pérez-Gómez B, et al. Desigualdades sociales en la mortalidad cardiovascular en España desde una perspectiva interseccional. Rev Española Cardiol. 2020;73:282–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vandenheede H, Deboosere P, Espelt A, et al. Educational inequalities in diabetes mortality across Europe in the 2000s: the interaction with gender. Int J Public Health. 2015;60:401–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bauer GR. Incorporating intersectionality theory into population health research methodology: Challenges and the potential to advance health equity. Soc Sci Med. 2014;110:10–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mackenbach JP, Stirbu I, Roskam AJR, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in health in 22 European countries. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2468–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Costa-Font J, Gil J. Exploring the pathways of inequality in health, health care access and financing in decentralized Spain. J Eur Soc Policy. 2009;19:446–58. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cimas M, Gullon P, Aguilera E, et al. Healthcare coverage for undocumented migrants in Spain: Regional differences after Royal Decree Law 16/2012. Health Policy (New York). 2016;120:384–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rodin D, Stirbu I, Ekholm O, et al. Educational inequalities in blood pressure and cholesterol screening in nine European countries. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66:1050–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Borrell C, Peiró R, Ramón N, et al. Desigualdades socioeconómicas y planes de salud en las comunidades autónomas del Estado español. Gac Sanit. 2005;19:277–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mehdipanah R, Rodríguez-Sanz M, Malmusi D, et al. The effects of an urban renewal project on health and health inequalities: a quasi-experimental study in Barcelona. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2014;68:811–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Borrell C, Muntaner C, Solà J, et al. Immigration and self-reported health status by social class and gender: the importance of material deprivation, work organisation and household labour. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cainzos-Achirica M, Vela E, Cleries M, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors and disease among non-European immigrants living in Catalonia. Heart. 2019. 105:1168–1174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Estadística del Padrón Continuo. 2019. [cited 2019 May 1]. Available from: www.ine.es [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gimeno-Feliu LA, Calderón-Larrañaga A, Diaz E, et al. The healthy migrant effect in primary care. Gac Sanit. 2015;29:15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Espelt A, Goday A, Franch J, et al. Validity of self-reported diabetes in health interview surveys for measuring social inequalities in the prevalence of diabetes. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012. July;66:e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garrido-Cumbrera M, Borrell C, Palència L, et al. Social Class Inequalities in the Utilization of Health Care and Preventive Services in Spain, a Country with a National Health System. Int J Heal Serv. 2010;40:525–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilder RP, Majumdar SR, Klarenbach SW, et al. Socio-economic status and undiagnosed diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2005;70:26–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.