Abstract

This cross-sectional study measures clinicians’ time spent using electronic health records by specialty and the activities performed.

While electronic health records (EHRs) have been associated with positive effects, such as improved health care outcomes1 and reduced errors,2 they have also increasingly filled clinicians’ days and have been associated with negative downstream effects on satisfaction with work3 and well-being.4 Previous work has described EHR use patterns within specific specialties and time spent on various EHR functions during ambulatory patient encounters.5 However, there is less information available about differences in time spent on the EHR by specialty or the distribution of EHR activities across specialties.

In this cross-sectional study, we measured total and after-hours time spent actively using EHRs by specialty and the distribution of activities on which clinicians spend their time in the EHR.

Methods

The sample included 351 US-based ambulatory health care organizations that used the EHR vendor Epic Systems between January and August 2019, representing nearly all of Epic’s ambulatory care customer base. The sample included all clinicians with scheduled outpatient appointments, including physicians and advanced practice practitioners. To characterize specialty variation in EHR usage, we categorized the specialties present at each organization as surgical specialties, medical specialties, or primary care specialties. This study was deemed exempt by the institutional review board at Stanford University because it used deidentified data and was not human subject research.

Using methods previously described,6 we measured total daily time actively using the EHR per clinician and time spent after-hours per clinician. Active EHR time was categorized into clinical review, notes, in-basket messages, and orders. We additionally measured the average number of in-basket messages received per clinician per day, both overall and broken down by source. We compared these metrics across surgical vs medical vs primary care specialties. Finally, we performed multivariable linear regression to examine associations between total EHR active use time and after-hours EHR active use time and specialty type adjusting for observable health system characteristics. All analyses were conducted in Stata, version 16.1 (StataCorp).

Results

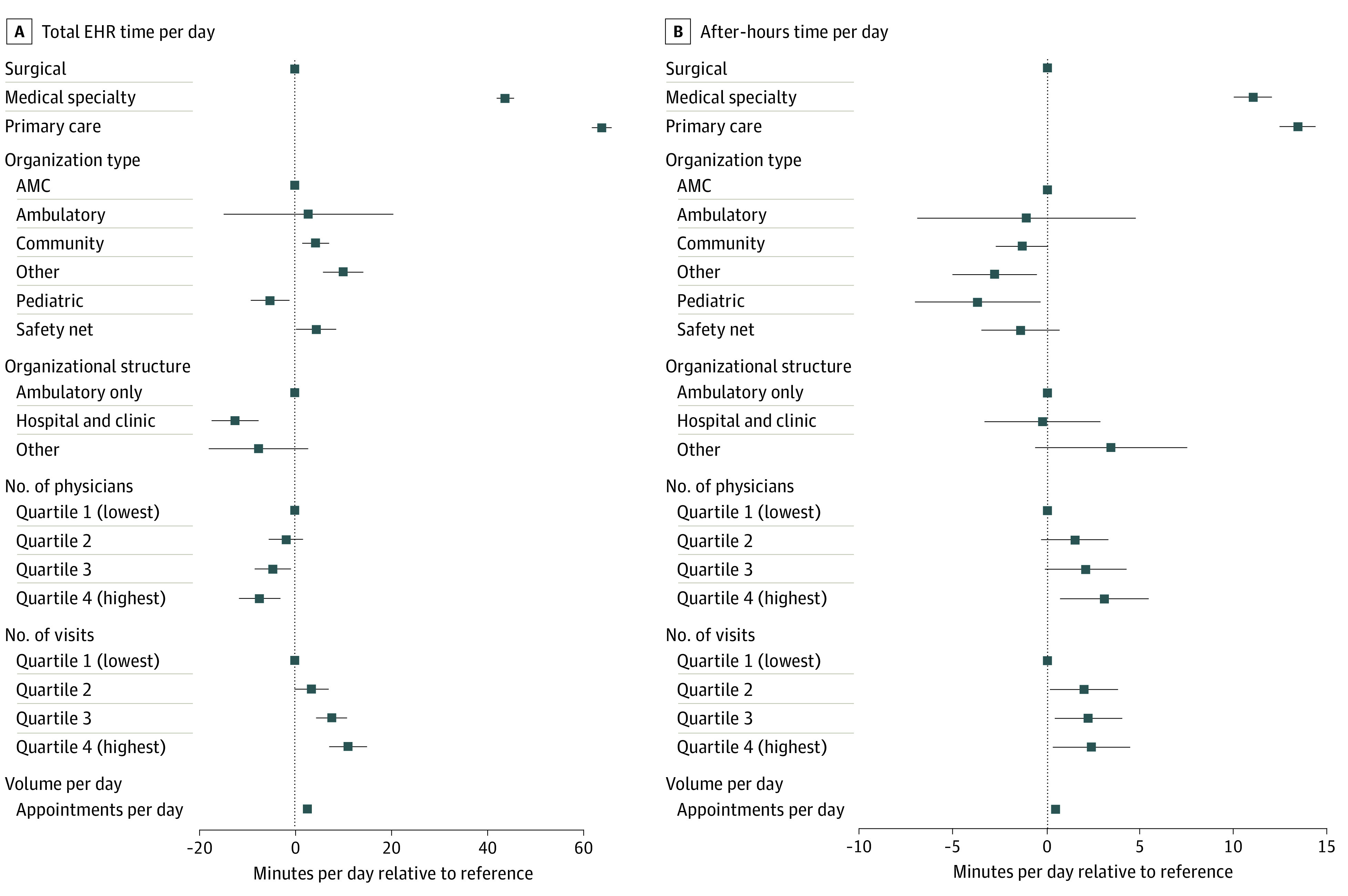

Mean (SD) total active daily EHR time was 45.6 (24.6) vs 85.7 (40.6) vs 115.0 (32.6) minutes for surgical vs medical vs primary care specialties, respectively. Mean (SD) after-hours active use time on the EHR was 16.0 (13.1) vs 26.2 (21.1) vs 29.8 (12.7) minutes, respectively. Differences in total and after-hours active use time spent on the EHR between groups persisted on multivariable linear regression controlling for organizational characteristics (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Comparisons of Total and After-hours Electronic Health Record (EHR) Active Use Time for 351 Health Systems.

Data displayed represent point estimates and 95% CIs derived from multivariable regression. AMC indicates academic medical center.

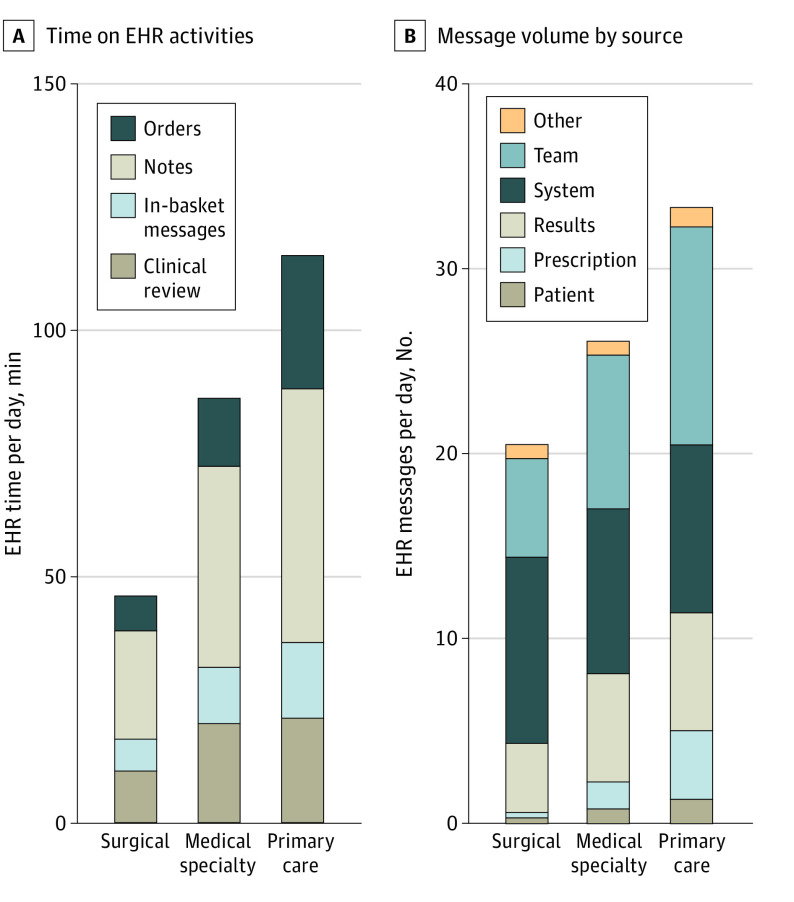

Clinicians spent the most time on notes, with surgical specialties spending a mean (SD) of 22.0 (13.9) minutes per day, vs 40.8 (22.6) minutes for medical specialties and 51.5 (14.4) minutes for primary care specialties. Clinical review and orders represented the next 2 biggest areas of time expenditure (Figure 2A). Team and system messages were the predominant sources of messages. Compared with surgical colleagues, primary care clinicians received more than twice as many team-derived messages, 5 times as many patient messages, and 15 times as many prescription messages each day (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Distribution by Specialty of Time on Electronic Health Record (EHR) Activities and Message Volume by Source for 351 Health Systems.

Discussion

We identified significant cross-specialty differences in daily EHR time, with clinicians in primary care and medical specialties spending significantly more time on the EHR than clinicians in surgical specialties. These differences persisted after adjustment for organizational factors. Additionally, there were interspecialty differences in time spent on notes and in-basket messages, as well as message sources.

Our study’s strengths include use of data from a broad set of institutions, practice types, and geographic locations, and the availability of granular information about usage patterns. Limitations include use of a measure of EHR work that considers only when clinicians are actively working (thus likely underestimating total time spent on the EHR), a focus on ambulatory practices, an inability to describe the breakdown of after-hours activity, and lack of accounting for time spent by scribes on documentation.

The interspecialty differences we have identified are important given the known associations between administrative burden and clinician burnout. Further investigation should seek to characterize the reasons underlying these differences and identify interventions that reduce the EHR burden.

References

- 1.Lin SC, Jha AK, Adler-Milstein J. Electronic health records associated with lower hospital mortality after systems have time to mature. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(7):1128-1135. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Radley DC, Wasserman MR, Olsho LEW, Shoemaker SJ, Spranca MD, Bradshaw B. Reduction in medication errors in hospitals due to adoption of computerized provider order entry systems. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013;20(3):470-476. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2012-001241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friedberg MW, Chen PG, Van Busum KR, et al. Factors affecting physician professional satisfaction and their implications for patient care, health systems, and health policy. Rand Health Q. 2014;3(4):1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tran B, Lenhart A, Ross R, Dorr DA. Burnout and EHR use among academic primary care physicians with varied clinical workloads. AMIA Jt Summits Transl Sci Proc. 2019;2019:136-144. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Overhage JM, McCallie D Jr. Physician time spent using the electronic health record during outpatient encounters: a descriptive study. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(3):169-174. doi: 10.7326/M18-3684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holmgren AJ, Downing NL, Bates DW, et al. Assessment of electronic health record use between US and non-US health systems. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(2):251-259. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.7071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]