Abstract

Objective

Parents of seriously ill children worry about their vulnerable child contracting COVID-19, whether their child's palliative care providers will be able to continue to provide the same quality of care to their child, and who can be with the child to provide comfort. For providers, shifts in healthcare provision, communication formats, and support offerings for families facing distress or loss during the pandemic may promote providers’ moral distress. This study aimed to define the ways that the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted end-of-life care and approach to bereavement care in pediatric palliative care (PPC).

Method

The Palliative Assessment of Needed DEvelopments and Modifications In the Era of Coronavirus (PANDEMIC) survey was developed to learn about the PPC experience during COVID-19 in the United States. The survey was posted with permission on seven nationally focused Listservs.

Results

A total of 207 PPC team members from 80 cities within 39 states and the District of Columbia participated. In the majority of hospitals, admitted pediatric patients were only allowed one parent as a visitor with the exception of both parents or nuclear family at end of life. Creative alternatives to grief support and traditional funeral services were described. The high incidence of respondents’ depicted moral distress was often focused on an inability to provide a desired level of care due to existing rules and policies and bearing witness to patient and family suffering enhanced by the pandemic.

Significance of results

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a profound impact on the provision of end-of-life care and bereavement for children, family caregivers, and PPC providers. Our results identify tangible limitations of restricted personal contact and the pain of watching families stumble through a stunted grieving process. It is imperative that we find solutions for future global challenges and to foster solidarity in PPC.

Key words: Bereavement, COVID-19, End of life, Moral distress, Pediatric palliative care

Introduction

Months into the COVID-19 pandemic, patients and families are experiencing extensive changes to their healthcare and support networks, including in end of life (EoL) and bereavement. Cumulative multiplicity of loss; disruption of connectivity between patients, families, and healthcare professionals; and uncertainty are themes that were identified in studies of bereavement outcomes during previous pandemics (Downar and Seccareccia, 2010; Mayland et al., 2020). In the current pandemic, with early “stay at home” orders put into place, children have been experiencing the loss of connection with extended family and other forms of familiar support such as school, clubs, and community activities. Parents of seriously ill children, for whom personal connection and touch are so deeply valued, worry about their vulnerable child contracting COVID-19 (McElroy et al., 2020), and if so, whether they would receive the usual supportive treatment required with intensive care units (ICUs) being overwhelmed with adult patients. They also question whether their child's palliative care providers will be able to continue to provide the same quality of care to their child (Ekberg et al., 2020) in the inpatient or outpatient settings. Moreover, with hospitals limiting visitors, parents worry about who can be with the child to provide comfort and whether they, as parents, can be present with their child, particularly at the EoL. In the subsequent bereavement period, COVID has also limited accessibility of culturally respectful rituals for remembering and celebrating a loved one's life (Moore et al., 2020).

For providers, shifts in healthcare provision to ensure that patient and provider safety have created difficult professional situations, particularly for those working with children and families at the EoL and in bereavement (Haward et al., 2020). Compassion and connection have developed deeper meaning during this prolonged pandemic. However, care teams have been unable to rely on the same physical access to a patient's family and friends, potentially limiting a team's ability to provide the most meaningful care to both the patient at the EoL and their support network during bereavement. Furthermore, providers, as friends and loved ones themselves, must balance their professional commitment to treat patients with their right to protect those that they love (Bakewell et al., 2020). The dissonance between a need for community and the danger of gathering, or between a provider's duty and their safety, can promote moral distress and mental anguish (Greenberg et al., 2020), particularly for pediatric palliative care (PPC) teams tasked with helping families navigate the death of a child.

Originally described by Andrew Jameton in 1984 (Jameton, 1984), moral distress has traditionally been defined as a phenomenon experienced by nurses “when one knows the right thing to do, but institutional constraints make it nearly impossible to pursue the right course of action.” In an effort to establish “conceptual clarity” within the heterogeneous literature published on this subject over the past few decades, Morley et al. (2019) instead proposed that the following sequence of events leads to moral distress: “(1) the experience of a moral event, (2) the experience of psychological distress, and (3) a direct causal relationship between (1) and (2).” This more relativistic definition of moral distress covers a broader spectrum of healthcare provider experiences. Moreover, by focusing on the components of inciting events and triggered psychological responses, this definition better identifies discreet targets for measurement and intervention (Morley, 2018).

In a recent article, Morley et al. (2020) explored hypothetical situations to describe how the COVID-19 pandemic might produce various types of moral distress in providers. However, Morley et al. does not incorporate direct provider experiences to bolster these descriptions nor comment on the specific situations encountered by pediatric providers. How the pandemic has impacted PPC teams in terms of their clinical role at the end of a child's life, their ability to facilitate bereavement rituals, and possible moral distress with the quality of support that they are able to provide in these endeavors has not yet been studied.

Palliative Assessment of Needed DEvelopments and Modifications In the Era of Coronavirus (PANDEMIC) Survey was developed to learn about the PPC experience during COVID-19 to inform past lessons and future direction. Notably, in our analysis of open-ended survey responses, we also discovered that many providers expressed varying degrees of distress with the quality of care provided during the pandemic. This paper addresses the ways that the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted EoL care and the approach to bereavement care and reveals a novel dimension of moral distress encountered by PPC providers in the current era.

Methods

Design and sample

Healthcare professionals from medical settings in the United States providing PPC were asked to complete the study survey. An announcement of the survey was posted with permission on seven nationally focused Listservs with interdisciplinary focus: the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine (AAHPM) Pediatric Palliative Care Special Interest Group; Palliative Care Research Cooperative (PCRC) Pediatric Group; Hospice and Palliative Nurse Association (HPNA) Pediatric Special Interest Group; Association of Pediatric Oncology Social Workers (APOSW), Social Work Hospice and Palliative Network (SWHPN), Pediatric Chaplains Network, a professional Pediatric Bereavement Care group, and a clinical Child Life group. Each Listserv posted one announcement with one follow-up reminder spaced between 7 and 14 days after initial announcement during the dates of May 1 to June 26, 2020. For further chain-referral sampling, the survey link was also e-mailed with one reminder message to PPC clinical faculty representative of 10–20 programs from each low, medium, and high COVID-19-burdened epidemiology geographies based on the Johns Hopkins University Coronavirus Resource Center map distribution in this same timeframe (US Map, 2020).

Measures

Survey questions were designed by a collaborative, interdisciplinary study team according to the Tailored Method of Survey Design (Dillman et al., 2014). The survey instrument consisted of 52 closed and 5 open-ended questions. The survey was independently reviewed, piloted, revised, and re-piloted by an interdisciplinary team (two physicians, two social workers, two nurse scientists, one chaplain, and one mixed methodologist) prior to administration on SurveyMonkey©.

Participants were asked to describe the ways that the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted pediatric EoL care and bereavement approaches. For children facing EoL, participants were specifically asked about visitation policies during inpatient stays and the availability of legacy interventions. Participants were also asked about funeral services and the impact on bereavement interventions since the beginning of the pandemic. Open-ended responses allowed us to capture additional thoughts and experiences not included within the survey questions.

Data collection and analysis

The Office of Human Subjects Research Protections at the National Institutes of Health determined that the survey format and content qualified as exempt from full Institutional Review Board review. A SurveyMonkey© questionnaire format was utilized for online data collection.

The analyses were descriptive and univariate in nature. The study team utilized counts for categorical variable responses. For missing responses due to skip patterns in the survey, the number of responders was used as the denominator (actual n). The study team evaluated free-text narrative responses according to three classifications related to moral distress using the following definitions: (1) moral-constraint: distress due to constraint from doing what one thinks is the ethically appropriate action; (2) moral-uncertainty: distress from uncertainty about whether one is doing the right thing (Morley et al., 2020); and (3) moral-observer: distress from observing (potentially) traumatic events but institutional or public health regulations make it impossible for a different action to be taken.

Results

Survey respondents included 207 PPC team members from 80 cities within 39 states and the District of Columbia representative of 38 northeastern, 51 southern, 58 midwestern, 34 western, and 23 southwestern regions as defined by National Geographic criteria. Respondents included physicians, nurses, child life specialists, social workers, chaplains, and psychologists.

Visitation policies

To assess visitation policies, participants were asked two questions: (1) What is the current hospital visitor policy for pediatric patients?: (a) no visitors, (b) one parent, (c) two parents, (d) nuclear (core) family members (parents, siblings), (d) extended family members, (e) other (please describe) (N = 114). (2) Does your center make an exception for visitors at the patient's end of life?: (a) yes, (b) no (N = 114). If yes, participants are asked, Under the visitor policy exception, how many/which visitors are allowed at the patient's end of life?: (a) one parent, (b) two parents, (c) nuclear (core) family members (parents, siblings), (d) extended family members, (e) other (please specify) (N = 108).

Hospital policies during the initial weeks of the pandemic varied for pediatric patients, whereas the general standard for adult patients was a limitation of any and all visitors to include at active EoL. Few (2.6%, n = 3) allowed no visitors. The majority (54.4%, n = 62) allowed one parent, 1.9% (n = 25) allowed two parents, 1% allowed extended family members, while 20.2% (n = 23) based on their policies on individual circumstances. Comments from the open-ended responses about who is allowed under visitor policies focused on three distinct themes: the need to follow strict number guidelines (They can have two designated visitors. They have to designate them at the time of admission and that cannot be changed.); decisions made based on the visitor's relationship with the child (Two parents for duration of hospitalization, but only one in the building at a time.); and the ability to make exceptions to hospital policy with flexibility (we are able to make compassionate exceptions with inpatient floor's leadership team approval for patients at the EoL or for when two parents are needed for a crucial meeting regarding patient's care.)

Overall, most centers enforced only one core visitor being allowed. The majority of centers (95%, 108 of 114 total respondents) make an exception on visitor policies when the child is at the EoL, including limited sibling visits. Of those that make exceptions (N = 108), approximately a third (38%, n = 41) allow the nuclear (core) family to be with the child, 18.5% (n = 20) allow two parents, 7.4% (n = 8) allow some extended family members, and 36.1% (n = 39) described other variations of EoL exceptions. These include family decision (pretty much anyone the family feels they need), a specific number (a total of four visitors allowed, two at the bedside at a time), and flexibility on a case-by-case basis (depends on if the patient is from “endemic” area). Several participants described policies restricting visitors to those over 18 years, while others restricted sibling visitors even at the pediatric patient's active EoL or preparatory days prior to death.

Funeral services

To assess how funeral services have been impacted since the pandemic began, participants were asked, How have funeral services changed?: (a) families holding teleconference funerals, (b) life memorials delayed until people can gather again, (c) other (please describe) (N = 114). In most cases, families delayed life memorials until people can gather again (72.8%, n = 83). A little less than half of the families (42.1, n = 48%) also held teleconference funerals soon after death. Participants described a variety of creative alternatives to traditional funeral services, including meeting at outdoor locations, community “drive by” funerals held in the front yard, and community murals to celebrate a child's life. Several participants reported seeing smaller and more restricted funeral services (n = 11). Whereas 100% of participants reported attending a child's service or funeral prior to COVID-19, only 16.9% (n = 12) have done so since the pandemic started.

Bereavement interventions

To assess bereavement interventions, participants were asked two questions. (1) How have bereavement support groups been provided during COVID-19? Please check all that apply: (a) in-person, (b) canceled, (c) online, (d) by phone, (e) never had bereavement support groups, (f) other (please describe) (N = 114). (2) Please select all the forms of direct bereavement services that were systematically offered at your center prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Please check all that apply: (a) phone call from a healthcare team member, (b) phone call from a bereavement coordinator, (c) literature — child grief, (d) literature — adult grief, (e) cards, (f) attend service/funeral, (g) anniversary cards, (h) counseling in-person, (i) counseling online, (j) referral to a counselor/therapist, (k) referral to a support group, (l) other (please specify) (N = 111).

Over a third (37.3%, n = 43) never provided bereavement support groups. Of those who did, only one participant reported bereavement in-person groups continuing during COVID-19. Other bereavement support groups were canceled (18.4%, n = 21), provided online (31.6%, n = 36), or by phone (27.2%, n = 31). Additional responses (9.7%, n = 11) included a plan to offer programs online and referral to other programs that offer such programs.

Most other bereavement support services continued to be provided since the beginning of the pandemic (including a phone call from a healthcare team member, phone call from a bereavement coordinator, literature sent to the family about child and adult grief, a card sent to the home, or referral to a counselor/therapist as indicated). Some of these included modifications such as no longer handing the card around to multiple interdisciplinary team members for personal condolences but instead one assigned person sending all cards to minimize team members’ physical contact. All participants reported offering in-person counseling prior to the pandemic and this dropped to 11.1% (n= 5) since COVID-19.

Moral distress associated with care provided

Throughout the open-ended questions, participants provided descriptions of experiences that exemplified different types of distress. Participant responses were extracted and coded from the following questions: (1) responded “other” to: Under the visitor policy exception, how many/which visitors are allowed at the patient's end of life?, (2) responded “other” to: How have funeral services changed?, (3) Can you tell us about an experience you have had related to COVID-19 that you feel will stay with you, always?, (4) What is something you have learned since COVID-19 that will impact your palliative practice going forward?, (5) What is something you wished you knew/learned prior to the COVID-19 pandemic that might have impacted how you approached palliative care during the pandemic?, (6) What is something you wish you knew/learned prior to the COVID-19 pandemic that might have impacted how you approached your personal family/family life during the pandemic?, (7) Please take this opportunity to share any other ways that your work has been impacted by COVID-19 that have not been captured in this.

Survey

Of reviewed open-ended responses, 21 responses described the situations of moral-constraint distress, often focusing on an inability to provide a desired level of care due to existing rules and policies. A similar number of responses (n = 18) identified moral-observer distress when bearing witness to patient and family suffering enhanced by the pandemic. Six (n = 6) responses described moral-uncertainty distress when struggling to determine whether the correct decisions were being made for patient care. Specific quotes and examples are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Type of distress and exemplary quotes from study respondents

|

Moral-Constraint Distressa One is feeling distressed because they are constrained from doing what they think is the ethically appropriate action N = 21 |

I will never forget telling a mama that her child would die, while the child's dad looked helplessly on via facetime, because he had not been allowed on campus due to new Covid-19 restrictions. It was heartbreaking. |

| Caring for dying children right now is much more difficult and sad. … Trying to balance which patients to check on from home and which need to be seen in person has led to a great deal of conflict within the team. That conflict and difficulty will stay with me for a long time. | |

| Have a mother crying and very upset about her dying infant and not being able to hug her. It will stick with me. I hated it. | |

| I had a child abuse case, likely due to stress of COVID-19, that ended in redirection of care. It was a terrible case, and to top it off we couldn't get Mom the additional support she needed during EoL care for her daughter. Also had a re-direction of care where grandfather facetimed from the lobby to say goodbye because he was not allowed to come to the room. | |

| I've learned how important touch is…especially during difficult conversations and at the end of life. | |

|

Moral-Observer Distress Observing (potentially) traumatic events but institutional or public health constraints make it impossible for a different action to be taken N = 18 |

Some families have held drive by funerals for teenagers and stood in their yards while the teens drove by to send love. Heart breaking to imagine. |

| A young mother facing removal of LST (extubation) of her toddler with only one other family member able to visit with her and their priest performing a ritual from the hospital parking lot. | |

| The despair of families who knew their child was approaching the end of their life and not be able to be all together as a family until the child was actively dying. | |

| The trauma inflicted upon siblings that were not able to visit their sibling as they died. | |

| How awful awful awful it is when a family is not whole, when only one parent can be with a child, how staggering the suffering is for all family members. | |

|

Moral-Uncertainty Distressa One is feeling distressed because they are uncertain about whether they are doing the right thing N = 6 |

I don't know if it's the larger grief and stress we are all facing, or the lack of my team members with me, or if people are making different choices than usual and deaths are clustering, or what the root of it is. |

| Decisions about furlough, salaries, hiring freezes will impact teams for years and are not easy ones to make. Even those, like myself who are experienced leaders find the uncertainty overwhelming at times. | |

| Big increase in personal anxiety — fear of going to people's homes, apartment buildings, etc. and worrying about bringing infection home to loved ones or other patients. |

Definitions from Morley et al. (2020).

Discussion

The results of the PANDEMIC survey revealed several new challenges imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic in fostering compassionate care to pediatric patients and their families at the EoL and through the subsequent bereavement process. The survey responses described several ways that institutions uniquely interpreted infectious control standards and translated public health priorities into variable visitation policies across settings (Andrist et al., 2020; Murray and Swanson, 2020). In the majority of hospitals, surveyed PPC providers noted that admitted pediatric patients were only allowed one parent as a visitor. At the EoL, a similar majority made exceptions, but maintained restrictions maintained to allow both parents only or nuclear family only. It has been posited that COVID-induced patient isolation likely leads to higher rates of complicated grief for bereaved families as this phenomenon is predicted by an inability to say “goodbye,” fragmented communication within families, lower social support, and lack of family preparation prior to death (Siddiqi, 2020; Wallace et al., 2020). Enhanced isolation at times of distress leads to higher rates of mental health problems and as much as an eight times higher rate of adverse events related to supportive care failures (Chochinov et al., 2020).

More specifically assessing family bereavement, PPC providers noted that the majority of families delayed funerals or life memorials. There were also dramatic restrictions on in-person bereavement groups; most were converted to either online or telephone meetings and nearly 20% of groups were canceled. It is thought that these changes to bereavement may lead to higher disenfranchized grief as families are unable to grieve following normal rituals and with expected support networks (Wallace et al., 2020). For bereaved parents, the importance of these rituals and experiences is amplified (Helton et al., 2020). A recent article published by Snaman et al. prior to the pandemic offered a conceptual framework for understanding the longitudinal complexity of bereaved parents following the death of a child (Snaman et al., 2020). The model identifies protective factors (social support, meaning making, comforting continuing bonds) and risk factors (prolonged grief, isolation, financial strain, decisional regret) undermined and enhanced, respectively, in the current climate.

These results call for further research and clinical interventions to address ongoing EoL care and bereavement needs for parents and families denied traditional supports in the context of the pandemic. Generally, efforts must seek to overcome novel (i.e., pandemic-related) challenges and now heightened preexisting barriers to providing care. For pediatric and adult patients and families, as noted by others, early integration of advance care planning discussions may help mitigate complex grief and allow for better planning of memorial services given current restrictions (Carr et al., 2020; Wallace et al., 2020). Another proposed way to enhance patient/family access to compassionate care is training of more “front-line” providers in palliative care core principles, as PPC teams or other care team members may either be restricted from seeing patients if deemed “non-essential” or over-extended due to high demand (Etkind et al., 2020; Radbruch et al., 2020).

Bereavement interventions have needed to shift as well, often to incorporate creative modalities for connection or online methods for support (Moore et al., 2020). There have been calls for a modified structure to bereavement outreach (Morris et al., 2020) and increased screening for mental health factors in bereaved individuals (Sun et al., 2020). Lichtenthal et al. have proposed conversation scripts that can be implemented with bereaved family members to assess risk for a possible grief disorder (Lichtenthal et al., 2020). The authors advocate for healthcare providers reaching out to bereaved families and asking the following to determine if a referral for more intensive psychiatric evaluation is needed: (1) whether or not grief is impacting ability to function day to day and (2) whether or not bereaved persons identify someone available in their lives for emotional support. Currently existing supports or proposed interventions for grieving families in the COVID-19 era likely need expansion or enhancement. With grief compounded by isolation and potential regret and/or self-doubt when forced to make suboptimal decisions at the EoL, parents and siblings of children who have died during this pandemic are a vulnerable group that deserve close follow-up and longitudinal evaluation to protect their well-being and to ensure that we best serve future generations in similar situations.

Distinct from patient and family experiences, our results partially elucidate the personal impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on PPC providers in their provision of EoL and bereavement care (Rosenberg et al., 2020). When reflecting on lasting, memorable experiences with providing EoL care and bereavement support to families in the first months of the pandemic, many providers shared negative memories of both passive witnessing of heightened family suffering (moral-observer distress) and feeling restricted from providing the best care (moral-constraint distress). Our results, support recent articles that have posited that the ethical challenges posed by the pandemic could lead to higher secondary traumatic distress or moral distress for providers (Chochinov et al., 2020; Wallace et al., 2020). While surveys have found a high prevalence of severe burnout amongst intensivists during the pandemic (Azoulay et al., 2020), our results suggest that interdisciplinary palliative care teams already at increased risk, are now at additional risk of similar outcomes (Kavalieratos et al., 2017) as moral distress is thought to be a root cause of burnout.

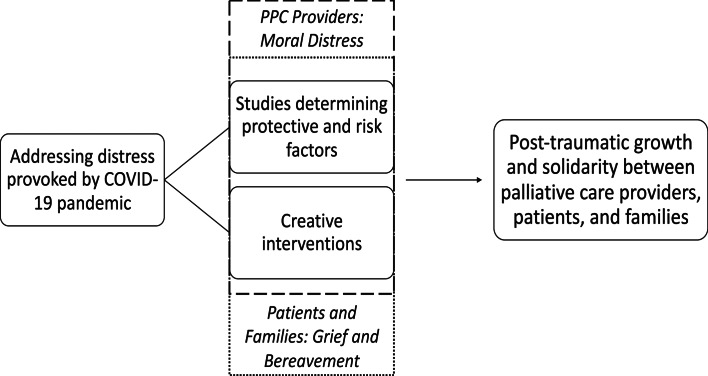

Efforts to address moral distress are essential to avoid widespread burnout, professional disillusionment, and moral injury. We provide two recommendations for further work in this area that couple with ongoing efforts to address the trauma inflicted by the COVID-19 pandemic on patients and families at the EoL (Figure 1). First, studies are needed to better characterize the breadth and depth of moral distress in PPC and other clinical teams, and identify factors associated with or protective against moral distress in these populations. Second, the field would benefit from the design of creative interventions that acknowledge and validate individual provider's experiences while delicately navigating the complex ethical terrain created by the pandemic. One recent article describes a production called “Theater of War for Frontline Medical Providers,” in which accomplished actors use an electronic platform to present dramatic readings from ancient Greek plays with the goal of “presenting free, easily accessible opportunities for medical providers, who may be struggling in isolation, to name and communalise their experiences, connecting with others who share them” (Rushton et al., 2020). Projects which seek to unify providers and derive power/community from shared, albeit tragic, experiences should be supported.

Fig. 1.

Process map for understanding and addressing multi-dimensional distress imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic on pediatric palliative care (PPC) providers, patients, and families.

Although our results provide insight into changes in EoL care and bereavement across many U.S. hospital systems, we do identify several important limitations. Foremost, as this study was completed early in the pandemic, the experience of providers may be different as hospital policies have shifted over the course of the pandemic. The exponential increase in the number of patients with COVID-19 and persistence of societal restrictions may compound the grief of bereaved families and the moral distress of providers. Alternatively, continued immersion in this changed world may promote better adaptive strategies and resilience. Changes in the distribution of COVID-19 cases between the time the survey was completed and now could also influence the generalizability of these results. Given the dynamic nature of the pandemic, it is hard to say the surveyed population would continue to be representative. While open-ended responses revealed moral distress in many providers, no questions directly asked respondents to reflect on distressing experiences. Therefore, we likely did not fully characterize this phenomenon.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a profound impact on the provision of EoL care and bereavement for children, family caregivers, and PPC providers. Moreover, our results not only identify concrete changes in practices but reveal providers’ experiences surrounding these changes, from the tangible limitations of restricted personal contact and gathering to the abstract and insidious pain of helplessly watching another family stumble through a stunted grieving process. As we continue to work to support patients, families, and ourselves during this evolving pandemic, it is imperative that we maintain perspective on how we have been changed inside this labyrinth in order to find solutions for future global challenges and to foster solidarity in PPC.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank our colleagues within the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine (AAHPM) Pediatric Palliative Care Special Interest Group; Palliative Care Research Cooperative (PCRC) Pediatric Group; Hospice and Palliative Nurse Association (HPNA) Pediatric Special Interest Group; Association of Pediatric Oncology Social Workers (APOSW); Social Work Hospice and Palliative Network (SWHPN); Pediatric Chaplains Network; a professional Pediatric Bereavement Care group; and a clinical Child Life group for their assistance with the survey distribution. We also wish to thank the pediatric palliative care clinicians who responded to the survey and provided their thoughtful perspectives. The authors acknowledge Drs. Erica Kaye, Kitty Montgomery, and Deb Fisher for their thoughtful additional reviews of the survey instrument.

Funding

This project was supported in part by the Intramural Program of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Cancer Institute (Dr. Wiener and Ms. Fry). Dr. Rosenberg is supported in part by the NIH (grant nos. R01 CA222486 and R01 CA225629).

Conflict of interest

None of the authors have a financial or other conflict of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- Andrist E, Clarke RG and Harding M (2020) Paved with good intentions: Hospital visitation restrictions in the age of coronavirus disease 2019. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine 21(10), e924–e926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azoulay E, De Waele J, Ferrer R, et al. (2020) Symptoms of burnout in intensive care unit specialists facing the COVID-19 outbreak. Annals of Intensive Care 10(1), 110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakewell F, Pauls MA and Migneault D (2020) Ethical considerations of the duty to care and physician safety in the COVID-19 pandemic. Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine 22(4), 407–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr D, Boerner K and Moorman S (2020) Bereavement in the time of coronavirus: Unprecedented challenges demand novel interventions. Journal of Aging & Social Policy 32(4–5), 425–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chochinov HM, Bolton J and Sareen J (2020) Death, dying, and dignity in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Palliative Medicine 23(10), 1294–1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillman D, Smyth J and Christian L (2014) Internet, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method, 4th Ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Downar J and Seccareccia D (2010) Palliating a pandemic: “all patients must be cared for”. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 39(2), 291–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekberg K, Weinglass L, Ekberg S, et al. (2020) The pervasive relevance of COVID-19 within routine paediatric palliative care consultations during the pandemic: A conversation analytic study. Palliative Medicine 34(9), 1202–1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etkind SN, Bone AE, Lovell N, et al. (2020) The role and response of palliative care and hospice services in epidemics and pandemics: A rapid review to inform practice during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 60(1), e31–e40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg N, Docherty M, Gnanapragasam S, et al. (2020) Managing mental health challenges faced by healthcare workers during Covid-19 pandemic. BMJ 368, m1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haward MF, Moore GP, Lantos J, et al. (2020) Paediatric ethical issues during the COVID-19 pandemic are not just about ventilator triage. Acta Paediatrica 109(8), 1519–1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helton G, Wolfe J and Snaman JM (2020) “Definitely mixed feelings”: The effect of COVID-19 on bereavement in parents of children who died from cancer. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 60(5), e15–e20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jameton A (1984) Nursing Practice: The Ethical Issues. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Kavalieratos D, Siconolfi DE, Steinhauser KE, et al. (2017) “It Is like heart failure. It is chronic … and It will kill You”: A qualitative analysis of burnout among hospice and palliative care clinicians. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 53(5), 901–910.e901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthal WG, Roberts KE and Prigerson HG (2020) Bereavement care in the wake of COVID-19: Offering condolences and referrals. Annals of Internal Medicine 173(10), 833–835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayland CR, Harding AJE, Preston N, et al. (2020) Supporting adults bereaved through COVID-19: A rapid review of the impact of previous pandemics on grief and bereavement. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 60(2),e33–e39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElroy E, Patalay P, Moltrecht B, et al. (2020) Demographic and health factors associated with pandemic anxiety in the context of COVID-19. British Journal of Health Psychology 25(4), 934–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore KJ, Sampson EL, Kupeli N, et al. (2020) Supporting families in end-of-life care and bereavement in the COVID-19 era. International Psychogeriatrics 32(10),1245–1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morley G (2018) What is “moral distress” in nursing? How, can and should we respond to it? Journal of Clinical Nursing 27(19–20), 3443–3445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morley G, Ives J, Bradbury-Jones C, et al. (2019) What is “moral distress”? A narrative synthesis of the literature. Nursing Ethics 26(3), 646–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morley G, Sese D, Rajendram P, et al. (2020) Addressing caregiver moral distress during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine 87(10), 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris SE, Moment A and Thomas JD (2020) Caring for bereaved family members during the COVID-19 pandemic: Before and after the death of a patient. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 62(7), e70–e74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray PD and Swanson JR (2020) Visitation restrictions: Is it right and how do we support families in the NICU during COVID-19? Journal of Perinatology 40(10), 1576–1581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radbruch L, Knaul FM, de Lima L, et al. (2020) The key role of palliative care in response to the COVID-19 tsunami of suffering. Lancet 395(10235), 1467–1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg AR, Weaver MS, Fry A, et al. (2020) Exploring the impact of the coronavirus pandemic on pediatric palliative care clinician personal and professional well-being: A qualitative analysis of U.S. survey data. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management S0885-3924(20), 30788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushton CH, Doerries B, Greene J, et al. (2020) Dramatic interventions in the tragedy of the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 396(10247), 305–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqi H (2020) To suffer alone: Hospital visitation policies during COVID-19. Journal of Hospital Medicine 15(11), 694–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snaman J, Morris SE, Rosenberg AR, et al. (2020) Reconsidering early parental grief following the death of a child from cancer: A new framework for future research and bereavement support. Supportive Care in Cancer 28(9), 4131–4139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Bao Y and Lu L (2020) Addressing mental health care for the bereaved during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 74(7), 406–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Map (2020) Johns Hopkins University Coronavirus Resource Center. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data. Published 2020. Accessed May 1, 2020.

- Wallace CL, Wladkowski SP, Gibson A, et al. (2020) Grief during the COVID-19 pandemic: Considerations for palliative care providers. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 60(1), e70–e76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]