Abstract

A recent retrospective study has provided evidence that COVID-19 infection may be notably less common in those using supplemental melatonin. It is suggested that this phenomenon may reflect the fact that, via induction of silent information regulator 1 (Sirt1), melatonin can upregulate K63 polyubiquitination of the mitochondrial antiviral-signalling protein, thereby boosting virally mediated induction of type 1 interferons. Moreover, Sirt1 may enhance the antiviral efficacy of type 1 interferons by preventing hyperacetylation of high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), enabling its retention in the nucleus, where it promotes transcription of interferon-inducible genes. This nuclear retention of HMGB1 may also be a mediator of the anti-inflammatory effect of melatonin therapy in COVID-19—complementing melatonin’s suppression of nuclear factor kappa B activity and upregulation of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2. If these speculations are correct, a nutraceutical regimen including vitamin D, zinc and melatonin supplementation may have general utility for the prevention and treatment of RNA virus infections, such as COVID-19 and influenza.

Keywords: coronary artery disease, acute coronary syndrome, coronary vessels

Melatonin supplementation may reduce risk for COVID-19

A retrospective analysis of 791 intubated patients with COVID-19 has found that, after adjustment for pertinent demographics and comorbidities, those treated with melatonin had a markedly lower risk for mortality (HR: 0.131, 95% CI: 0.076 to 0.223)—suggestive of a profound anti-inflammatory benefit.1 Such an effect might be anticipated, in light of melatonin’s ability to upregulate expression of silent information regulator 1 (Sirt1)—a deacetylase that is known to suppress the activity of the proinflammatory nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kappaB) transcription factor—and also upregulate nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), which promotes the transcription of a range of antioxidant proteins.2–4 Moreover, recent epidemiology suggests that melatonin usage may reduce the risk for contracting COVID-19. A recent retrospective study, examining data from 26 799 subjects in a COVID-19 registry and using propensity score matching to account for a range of covariates, found that current supplementation with melatonin was associated with a significant 28% reduction in risk for serologically detectible COVID-19 infection. Among Black Americans, this reduction in risk was a remarkable 52% (OR=0.48, 95% CI 0.31 to 0.75).5 The basis of this decrease in risk for COVID-19 is unclear, especially since Sirt1 activity, which melatonin promotes, is known to transcriptionally upregulate expression of ACE2—the cellular membrane receptor for COVID-19.6 7

Melatonin-induced Sirt1 may boost virally mediated mitochondrial antiviral-signalling (MAVS) activation

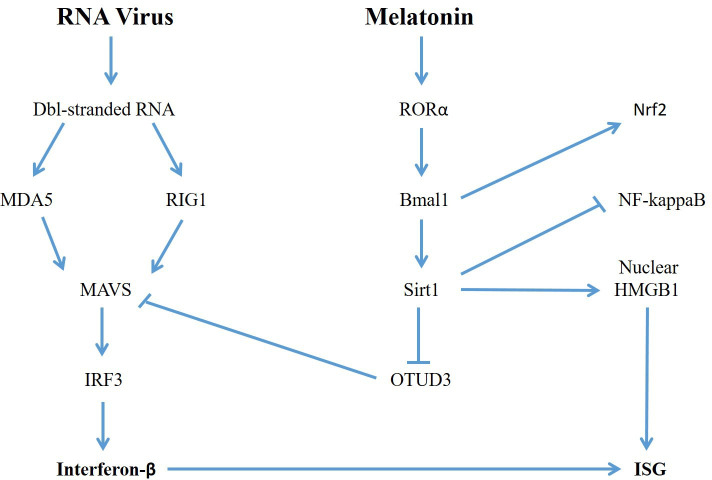

Here is a possible explanation. Melatonin, via its membrane receptors, induces nuclear translocation of the transcription factor retinoid-related orphan receptor alpha (RORα); RORα, in turn, promotes transcription of the gene encoding the clock transcription factor brain and muscle ARNT-like 1 (Bmal1). Bmal1 upregulates transcriptionally the expression of a number of proteins, including Sirt1 and Nrf2.2 8 9 The MAVS protein is a key mediator in the pathway of double-strand RNA sensing that leads to activation of interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) and induction of type 1 interferons; its K63 polyubiquitination via TRIM31 triggered by upstream detectors of cytosolic double-stranded RNA, such as melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5 and RIG1, enable it to form multimers that promote activating phosphorylation of IRF3, which in turn induces the type 1 interferons.10–12 But the ubiquitinase ovarian tumour ubiquitinase 3 (OTUD3) opposes this activation by deubiquitinating MAVS.13 The activity of OTUD3 in this regard hinges on acetylation of its Lys129; Sirt1 can remove this acetyl group, turn off OTUD3 activity and thereby upregulate viral activation of MAVS and type 1 interferon induction.13 For reasons still unclear, RNA viral infection causes Sirt1 to associate with OTUD3, such that the latter is deacetylated and thereby inactivated, enabling the K63 polyubiquitination of MAVS and subsequent multimer formation.13 figure 1 attempts to clarify these relationships.

The net effect of Sirt1 on interferon-mediated antiviral immunity is however complicated by the fact that Sirt1 inhibits NF-kappaB’s transcriptional activity; NF-kappaB also functions downstream from MAVS to promote the induction of type 1 interferons.11 14 15 The cellular response to RNA viruses typically activates IRF3, NF-kappaB, ATF2 and c-Jun, all of which can bind to the promoter of the interferon-β gene and promote its transcription. However, there is evidence that activation of IRF3, in the absence of NF-kappaB, ATF2 or c-Jun activation, can drive transcription of the interferon-β gene.16 Notably, in HEK293T cells infected with Sendai virus, transfection with Sirt1 more than doubles the mRNA expression of interferon-β1, despite the potential inhibitory impact of Sirt1 on NF-kappaB activity.13 Analogously, resveratrol, a Sirt1 activator, doubles interferon-β mRNA induction in Huh7 cells infected with dengue virus.17

In light of the fact that melatonin enhances Sirt1 expression via activation of Bmal1, it is pertinent that knockout of Bmal1 in mice impairs their ability to control pulmonary infections with the Sendai and influenza RNA viruses.18

Sirt1 may also amplify response to interferons by preventing nuclear export of high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1)

Sirt1 activity may also boost the antiviral response triggered by type 1 interferons. In response to inflammatory signals or certain viral infections, the damage-associated molecular pattern protein HMGB1 is hyperacetylated, causing its export from the nucleus and enabling its release from the cell.19 The p300/CBP-associated factor acetylase complex can mediate this acetylation, as has been demonstrated in dengue virus-infected cells.20 By reversing such acetylation, Sirt1 tends to keep this protein confined to the nucleus, where it has been shown to boost the transcription of type 1 interferon-stimulated antiviral genes.17 21 22 In this regard, HMGB1 has been shown to associate with the promoter region of the interferon-stimulated gene MxA.17 Indeed, the acetylation of HMGB1, triggered by viral infection, may represent a viral stratagem for suppressing expression of these antiviral genes. Hence, measures which enhance Sirt1 activity may both potentiate RNA virus-mediated induction of interferon-β and also render cells more sensitive to the antiviral activity of this cytokine. Figure 1 summarises these pathways.

Figure 1.

How melatonin up-regulates induction of type 1 interferons and interferon-stimulated genes (ISG) by inhibiting OTUD3 and promoting nuclear retention of HMGB1, while combating inflammation via inhibition of NF-kB activity, up-regulation Nrf2, and prevention of extracellular release of HMGB1.

Release of HMGB1 from virally infected cells stimulates the inflammatory activation of nearby myeloid cells, as it can act as an agonist for toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2), toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) and receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) receptors.23 It has been credibly argued that HMGB1 release may play a key role in triggering or exacerbating pulmonary inflammation in COVID-19 infection.24–26 Sirt1-mediated nuclear retention of HMGB1 may represent one important mechanism whereby melatonin administration aids resolution of COVID-19 infection. Additionally, as noted, Sirt1 opposes synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines by its inhibitory impact on NF-kappaB activity—which is downstream from the receptors activated by HMGB1.

Clinically, Sirt1 activity can also be boosted by agents such as metformin that activate AMP-activated kinase; this reflects the ability of adenosine AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) to induce nicotinamide ribosyltransferase, the rate-limiting enzyme for biosynthesis of Sirt1’s obligate substrate NAD+.27 28 However, AMPK also suppresses mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) activity, which is required for type 1 interferon synthesis, and this effect appears to predominate.29 With respect to the phytochemical resveratrol, which is reported to activate Sirt1 in rodent studies, its pharmacokinetics when administered orally in humans are too poor for it to be clinically useful in this regard.30 31 Nonetheless, it is intriguing that this Sirt1 activator has shown antiviral effects against a range of viruses in rodent and cell culture studies.32

These considerations suggest that melatonin supplementation may help to prevent and control RNA virus infections via upregulation of virally mediated type 1 interferon induction; melatonin may also enhance the antiviral activity of these interferons by maintaining the nuclear localisation of HMGB1. These hypotheses should be readily testable in animal models of viral infection, and, if confirmed, could point toward another valuable clinical application for this safe and affordable neurohormone nutraceutical.

Toward nutraceutical prevention of viral infections

More generally, it might be feasible to define a simple nutraceutical regimen that could reduce the risk for COVID-19 and a range of other viral infections. There is growing evidence, both case–control and ecologic, that replete vitamin D status not only markedly improves the clinical course of COVID-19, but also is associated with decreased risk for clinically detectible infection.33 34 Arguably, this might reflect upregulated lung production of defensins such as cathelicidin, the production of which is driven by calcitriol, which can be synthesised in lung cells that express 25-hydroxyvitamin D 1-α hydroxylase in response to inflammation.35 36 Cathelicidin is not only bactericidal, but also disrupts enveloped viruses such as SARS-CoV-2 and influenzas.37–39 Epidemiologic studies have correlated higher vitamin D status with lower risk for influenza and upper respiratory infections.40 41 COVID-19 epidemiology also suggests that higher zinc status is associated with both a better clinical course in this disorder and lower risk for infection.42 43 Especially in the elderly, who are more prone to poor zinc status, zinc supplementation has been found to boost acquired, antigen-specific immunity, while also exerting an anti-inflammatory action; such supplementation of the elderly was associated with a marked decrease in total infections in a 12-month randomised controlled trial.44 45 More speculatively, supplementation with glucosamine or with high-absorption sources of quercetin may have potential for boosting the type-1 interferon response and reducing viral infection risk.46–49 Hence, it is not unreasonable to suggest that a supplementation programme incorporating vitamin D, zinc, melatonin and possibly additional nutraceuticals could reduce risk for and aid control of COVID-19 and a range of other viral infections.

In regard to melatonin dosing, it should be acknowledged that, when used in the context of virally induced cytokine storm, multiple daily doses may be appropriate to optimise its anti-inflammatory efficacy. Indeed, a recent case series of 10 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia noted that melatonin supplementation (36–72 mg per day given in four divided doses) was associated with a reduction in hospital stay, mortality and mechanical ventilation.50 The large retrospective study of melatonin use in intubated patients with COVID-19 cited above does not clarify the dosing schedules employed.1 Whereas, when used in a preventive mode, bedtime dosing is appropriate so as not to disrupt circadian rhythm.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: MM is an owner of a nutraceutical company. JJD is a director of Scientific Affairs for Advanced Ingredients for Dietary Products.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Ramlall V, Zucker J, Tatonetti N. Melatonin is significantly associated with survival of intubated COVID-19 patients. medRxiv 2020. 10.1101/2020.10.15.20213546. [Epub ahead of print: 18 Oct 2020]. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.García JA, Volt H, Venegas C, et al. Disruption of the NF-ΰB/NLRP3 connection by melatonin requires retinoid-related orphan receptor-α and blocks the septic response in mice. Faseb J 2015;29:3863–75. 10.1096/fj.15-273656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hardeland R. Melatonin and inflammation-Story of a double-edged blade. J Pineal Res 2018;65:e12525. 10.1111/jpi.12525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jung K-A, Kwak M-K. The Nrf2 system as a potential target for the development of indirect antioxidants. Molecules 2010;15:7266–91. 10.3390/molecules15107266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou Y, Hou Y, Shen J, et al. A network medicine approach to investigation and population-based validation of disease manifestations and drug repurposing for COVID-19. PLoS Biol 2020;18:e3000970. 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel VB, Zhong J-C, Grant MB, et al. Role of the ACE2/Angiotensin 1-7 axis of the renin-angiotensin system in heart failure. Circ Res 2016;118:1313–26. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.307708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McLachlan CS. The angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor in the prevention and treatment of COVID-19 are distinctly different paradigms. Clin Hypertens 2020;26:14. 10.1186/s40885-020-00147-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou B, Zhang Y, Zhang F, et al. CLOCK/BMAL1 regulates circadian change of mouse hepatic insulin sensitivity by SIRT1. Hepatology 2014;59:2196–206. 10.1002/hep.26992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Early JO, Menon D, Wyse CA, et al. Circadian clock protein BMAL1 regulates IL-1β in macrophages via NRF2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018;115:E8460–8. 10.1073/pnas.1800431115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang B, Li J, Zhang X, et al. RIG-1 and MDA-5 signaling pathways contribute to IFN-β production and viral replication in porcine circovirus virus type 2-infected PK-15 cells in vitro. Vet Microbiol 2017;211:36–42. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2017.09.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhu W, Li J, Zhang R, et al. TRAF3IP3 mediates the recruitment of TRAF3 to MAVS for antiviral innate immunity. Embo J 2019;38:e102075. 10.15252/embj.2019102075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu B, Zhang M, Chu H, et al. The ubiquitin E3 ligase TRIM31 promotes aggregation and activation of the signaling adaptor MAVS through Lys63-linked polyubiquitination. Nat Immunol 2017;18:214–24. 10.1038/ni.3641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Z, Fang X, Wu X, et al. Acetylation-Dependent deubiquitinase OTUD3 controls MAVS activation in innate antiviral immunity. Mol Cell 2020;79:304–19. 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen J, Zhou Y, Mueller-Steiner S, et al. SIRT1 protects against microglia-dependent amyloid-beta toxicity through inhibiting NF-kappaB signaling. J Biol Chem 2005;280:40364–74. 10.1074/jbc.M509329200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deng Hong‐Ji, Zhou Chen‐Hui, Huang Li‐Tian, et al. Activation of silent information regulator 1 exerts a neuroprotective effect after intracerebral hemorrhage by deacetylating NF‐κB/p65. J Neurochem 2020. 10.1111/jnc.15258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peters KL, Smith HL, Stark GR, et al. IRF-3-dependent, NFkappa B- and JNK-independent activation of the 561 and IFN-beta genes in response to double-stranded RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002;99:6322–7. 10.1073/pnas.092133199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zainal N, Chang C-P, Cheng Y-L, et al. Resveratrol treatment reveals a novel role for HMGB1 in regulation of the type 1 interferon response in dengue virus infection. Sci Rep 2017;7:42998. 10.1038/srep42998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ehlers A, Xie W, Agapov E, et al. BMAL1 links the circadian clock to viral airway pathology and asthma phenotypes. Mucosal Immunol 2018;11:97–111. 10.1038/mi.2017.24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonaldi T, Talamo F, Scaffidi P, et al. Monocytic cells hyperacetylate chromatin protein HMGB1 to redirect it towards secretion. Embo J 2003;22:5551–60. 10.1093/emboj/cdg516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ong SP, Lee LM, Leong YFI, et al. Dengue virus infection mediates HMGB1 release from monocytes involving PCAF acetylase complex and induces vascular leakage in endothelial cells. PLoS One 2012;7:e41932. 10.1371/journal.pone.0041932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wei S, Gao Y, Dai X, et al. SIRT1-mediated HMGB1 deacetylation suppresses sepsis-associated acute kidney injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2019;316:F20–31. 10.1152/ajprenal.00119.2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu W, Lu Y, Yao J, et al. Novel role of resveratrol: suppression of high-mobility group protein box 1 nucleocytoplasmic translocation by the upregulation of sirtuin 1 in sepsis-induced liver injury. Shock 2014;42:440–7. 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nogueira-Machado JA, de Oliveira Volpe CM. HMGB-1 as a target for inflammation controlling. Recent Pat Endocr Metab Immune Drug Discov 2012;6:201–9. 10.2174/187221412802481784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Street ME. HMGB1: a possible crucial therapeutic target for COVID-19? Horm Res Paediatr 2020;93:73–5. 10.1159/000508291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andersson U, Ottestad W, Tracey KJ. Extracellular HMGB1: a therapeutic target in severe pulmonary inflammation including COVID-19? Mol Med 2020;26:42. 10.1186/s10020-020-00172-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Çelebier M, Haznedaroğlu İbrahim Celalettin, Çelebier M. Could targeting HMGB1 be useful for the clinical management of COVID-19 infection? Comb Chem High Throughput Screen 2020. 10.2174/1386207323999200728114927. [Epub ahead of print: 27 Jul 2020]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fulco M, Cen Y, Zhao P, et al. Glucose restriction inhibits skeletal myoblast differentiation by activating SIRT1 through AMPK-mediated regulation of NAMPT. Dev Cell 2008;14:661–73. 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Costford SR, Bajpeyi S, Pasarica M, et al. Skeletal muscle NAMPT is induced by exercise in humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2010;298:E117–26. 10.1152/ajpendo.00318.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saenwongsa W, Nithichanon A, Chittaganpitch M, et al. Metformin-induced suppression of IFN-α via mTORC1 signalling following seasonal vaccination is associated with impaired antibody responses in type 2 diabetes. Sci Rep 2020;10:3229. 10.1038/s41598-020-60213-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Milne JC, Lambert PD, Schenk S, et al. Small molecule activators of SIRT1 as therapeutics for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Nature 2007;450:712–6. 10.1038/nature06261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chimento A, De Amicis F, Sirianni R, et al. Progress to improve oral bioavailability and beneficial effects of resveratrol. Int J Mol Sci 2019;20. 10.3390/ijms20061381. [Epub ahead of print: 19 Mar 2019]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abba Y, Hassim H, Hamzah H, et al. Antiviral activity of resveratrol against human and animal viruses. Adv Virol 2015;2015:1–7. 10.1155/2015/184241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mercola J, Grant WB, Wagner CL. Evidence regarding vitamin D and risk of COVID-19 and its severity. Nutrients 2020;12. 10.3390/nu12113361. [Epub ahead of print: 31 Oct 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mariani J, Giménez VMM, Bergam I, et al. Association between vitamin D deficiency and COVID-19 incidence, complications, and mortality in 46 countries: an ecological study. Health Secur 2020. 10.1089/hs.2020.0137. [Epub ahead of print: 14 Dec 2020]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Telcian AG, Zdrenghea MT, Edwards MR, et al. Vitamin D increases the antiviral activity of bronchial epithelial cells in vitro. Antiviral Res 2017;137:93–101. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pryke AM, Duggan C, White CP, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha induces vitamin D-1-hydroxylase activity in normal human alveolar macrophages. J Cell Physiol 1990;142:652–6. 10.1002/jcp.1041420327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tripathi S, Tecle T, Verma A, et al. The human cathelicidin LL-37 inhibits influenza A viruses through a mechanism distinct from that of surfactant protein D or defensins. J Gen Virol 2013;94:40–9. 10.1099/vir.0.045013-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brice DC, Diamond G. Antiviral activities of human host defense peptides. Curr Med Chem 2020;27:1420–43. 10.2174/0929867326666190805151654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beard JA, Bearden A, Striker R. Vitamin D and the anti-viral state. J Clin Virol 2011;50:194–200. 10.1016/j.jcv.2010.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grant WB, Lahore H, McDonnell SL, et al. Evidence that vitamin D supplementation could reduce risk of influenza and COVID-19 infections and deaths. Nutrients 2020;12:988. April 2. 10.3390/nu12040988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jolliffe DA, Camargo CA, Sluyter JD, et al. Vitamin D supplementation to prevent acute respiratory infections: systematic review and meta-analysis of aggregate data from randomised controlled trials. medRxiv 2020. 10.1101/2020.07.14.20152728. [Epub ahead of print: 25 Nov 2020]. November 25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arentz S, Hunter J, Yang G, et al. Zinc for the prevention and treatment of SARS-CoV-2 and other acute viral respiratory infections: a rapid review. Adv Integr Med 2020;7:252–60. 10.1016/j.aimed.2020.07.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mossink JP. Zinc as nutritional intervention and prevention measure for COVID-19 disease. BMJ Nutr Prev Health 2020;3:111–7. 10.1136/bmjnph-2020-000095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prasad AS, Beck FWJ, Bao B, et al. Zinc supplementation decreases incidence of infections in the elderly: effect of zinc on generation of cytokines and oxidative stress. Am J Clin Nutr 2007;85:837–44. 10.1093/ajcn/85.3.837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Almeida Brasiel PG. The key role of zinc in elderly immunity: a possible approach in the COVID-19 crisis. Clin Nutr ESPEN 2020;38:65–6. 10.1016/j.clnesp.2020.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Song N, Qi Q, Cao R, et al. MAVS O-GlcNAcylation is essential for host antiviral immunity against lethal RNA viruses. Cell Rep 2019;28:2386–96. 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.07.085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.DiNicolantonio JJ, Barroso-Aranda J, McCarty MF. Azithromycin and glucosamine may amplify the type 1 interferon response to RNA viruses in a complementary fashion. Immunol Lett 2020;228:83–5. 10.1016/j.imlet.2020.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.DiNicolantonio JJ, McCarty MF. Targeting casein kinase 2 with quercetin or enzymatically modified isoquercitrin as a strategy for boosting the type 1 interferon response to viruses and promoting cardiovascular health. Med Hypotheses 2020;142:109800. 10.1016/j.mehy.2020.109800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aucoin M, Cooley K, Saunders PR, et al. The effect of quercetin on the prevention or treatment of COVID-19 and other respiratory tract infections in humans: a rapid review. Adv Integr Med 2020;7:247–51. 10.1016/j.aimed.2020.07.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Castillo RR, Quizon GRA, Juco MJM, et al. Melatonin as adjuvant treatment for coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia patients requiring hospitalization (MAC-19 pro): a case series. Melatonin Res. 2020;3:297–310. 10.32794/mr11250063 [DOI] [Google Scholar]