Abstract

Aim

Little is known about the pathophysiology of low anterior resection syndrome (LARS), and evidence concerning the management of patients diagnosed with this condition is scarce. The aim of the LARS Expert Advisory Panel was to develop practical guidance for healthcare professionals dealing with LARS.

Method

The ‘Management guidelines for low anterior resection syndrome’ (MANUEL) project was promoted by a team of eight experts in the assessment and management of patients with LARS. After a face‐to‐face meeting, a strategy was agreed to create a comprehensive, practical guide covering all aspects that were felt to be clinically relevant. Eight themes were decided upon and working groups established. Each working group generated a draft; these were collated by another collaborator into a manuscript, after a conference call. This was circulated among the collaborators, and it was revised following the comments received. A lay patient revised the manuscript, and contributed to a section containing a patient's perspective. The manuscript was again circulated and finalized. A final teleconference was held at the end of the project.

Results

The guidance covers all aspects of LARS management, from pathophysiology, to assessment and management. Given the lack of sound evidence and the often poor quality of the studies, most of the recommendations and conclusions are based on the opinions of the experts.

Conclusions

The MANUEL project provides an up‐to‐date practical summary of the available evidence concerning LARS, with useful directions for healthcare professional and patients suffering from this debilitating condition.

Keywords: colorectal surgery, complications, consensus, guidance, LARS, low anterior resection syndrome, rectal surgery

What does this paper add to the literature?

Low anterior resection syndrome has a severe impact on quality of life. Evidence on the condition is scarce. This manuscript represents a practical and balanced guide which will help clinicians and patients navigate the literature and choose the ideal treatment and associated consequences.

INTRODUCTION

Bowel function is significantly affected after rectal surgery. In the past, evidence suggested that a colostomy might be associated with worse quality of life compared with anal continence [1, 2], but bowel dysfunction is common after anatomical preservation of the sphincters. The spectrum of such dysfunction is broad, and can include incontinence, constipation and clustering of stool, all of which have a negative impact on health‐related quality of life (HRQoL) [3]. This wide range of complaints has been collated into a pragmatic definition, i.e. low anterior resection syndrome (LARS). Named after the surgical procedure commonly responsible for this clinical picture [4], LARS shows a high prevalence (60%–90%) and can last for years after surgical treatment [5]. Recently, a large international consensus trilingual Delphi process with patients as the major stakeholder refined the definition of LARS [6]. As disease‐free survival is regarded as the most important factor following curative rectal cancer surgery, the actual HRQoL and the potential ways to improve it are often overlooked [7].

Unfortunately, despite the growing interest, management of LARS is often empirical and symptom‐based, using existing therapies for faecal incontinence, faecal urgency and rectal evacuatory disorders. The evidence for defining the management of such a complex entity is very limited [8]. Only a small number of high‐quality trials have been conducted. However, as the rates of sphincter‐preserving rectal surgery are increasing, thanks to the technical and technological advances in the treatment of rectal diseases, there is an urgent need to provide a clinical pathway for clinicians who treat patients with LARS.

The aim of this project, led by experts in the emerging field of LARS, is to provide a balanced overview and practical guidance concerning the assessment of patients with LARS, the treatment options and some considerations to be taken into account when planning to set up an effective service, in order to meet the needs of these patients.

METHOD

A consensus group of experts (the LARS Expert Advisory Panel) in LARS assessment and treatment met in Copenhagen in March 2020. The group comprises experts, including gastroenterologists and colorectal surgeons, from several nations (Denmark, France, Austria, Italy, the Netherlands and the UK), who have a wide range of experience in the management of these patients.

During the first meeting of the group, the knowledge gaps were identified and the aims of the project were defined. The work was subdivided among several working groups devoted to specific sections, so that a comprehensive overview about LARS was produced. The project was named the ‘Management guidelines for low anterior resection syndrome’ (MANUEL) project.

A literature search strategy was agreed upon, and individual members led the article write‐up in the sections dealing with the topic in which they had particular expertise. Consensus was reached by round‐table discussions, which formed one of the scopes of this project. In fact, panellists were given the opportunity to brainstorm and exchange their opinions and preferences on specific management options. Based on the few high‐quality papers with strong evidence, and on clinical experience, each group drafted its own section. This was felt to be the most appropriate approach given the paucity of available literature and the poor quality of many studies.

The following sections were established: Section I, Pathophysiology: a mixed pathophysiological model for LARS; Section II, Identifying LARS and monitoring of treatment; Section III, Prevention of LARS; Section IV, Recommended work‐up; Section V, Best supportive care; Section VI, Transanal irrigation: indications, methods, troubleshooting; Section VII, When irrigation fails; Section VIII, The patient perspective; dissemination and future directions. A lay patient participated in the project, by revising the text and providing a personal insight which is reported in Section VIII.

Meetings were thereafter held via teleconferences, and the strategy to present the findings was agreed upon by all the members. All the sections were combined into a single manuscript that was circulated within the group. The manuscript was revised following comments from the participants, and the resulting manuscript, representing practical guidance suitable for patients with LARS, was again circulated and finalized for submission after approval during a final teleconference in September 2020.

Coloplast A/S facilitated the face‐to‐face meetings and teleconferences, but did not have any influence on the priorities of the MANUEL project or the final manuscript.

SECTION I: A MIXED PATHOPHYSIOLOGICAL MODEL FOR LARS

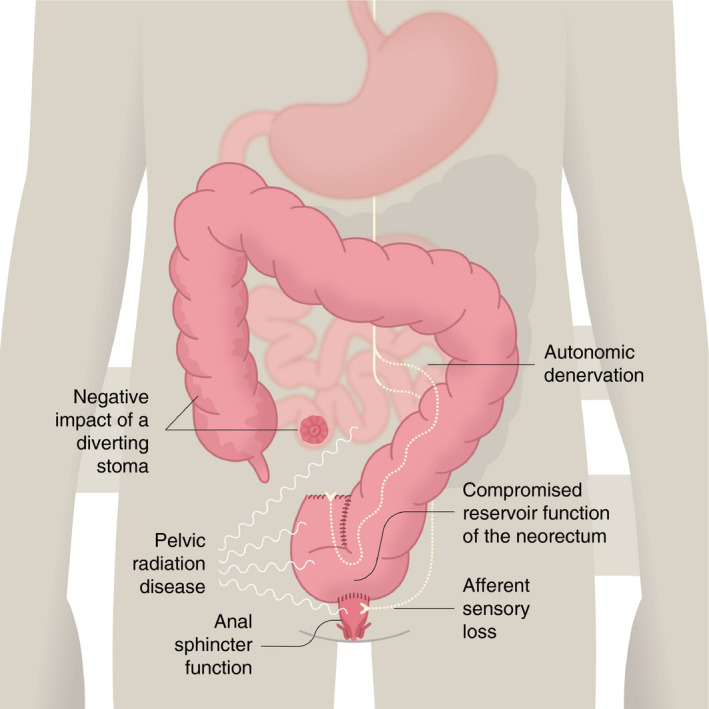

Anal continence is a complex interplay between the external anal sphincter, the internal anal sphincter, anorectal sensation, rectal compliance, rectal emptying and stool consistency. Treatment for rectal cancer may affect all of these to a varying extent. Therefore, LARS has a multifactorial aetiology with a complex anatomical, neurological, physiological and psychological background. Although the pathophysiological picture of LARS might seem slightly blurred, emerging evidence can be collected to form a mixed pathophysiological model for the condition (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Pathophysiology of low anterior resection syndrome (LARS). Schematic representation of the multifactorial aetiology of the syndrome. LARS is likely to result from a combination of several components

Reservoir function and evacuation of the neorectum

Standard rectal cancer treatment often involves total mesorectal excision (TME), with sphincter preservation if possible, with some patients requiring neoadjuvant therapy. Since the normal rectum plays an intricate part in both the storage and evacuation of flatus and stools, surgical resection of the rectum and the compromised physiological properties of the neorectum are thought to be the primary cause of LARS, due to change of reservoir function and impaired evacuation. Several efforts to restore reservoir function have been made in the form of coloplasty, side‐to‐end anastomosis and colonic J‐pouch. Side‐to‐end anastomosis and colonic J‐pouch improve function in the first 12–18 months [9], but their benefit seems to diminish thereafter [10]. Some studies have also shown that partial mesorectal excision (PME) is oncologically safe in selected patients and performs better than TME from a functional standpoint [3, 11, 12].

Anal sphincter function

Anal sphincter function relies on the external and internal anal sphincters and nervous system interplay and control. Theoretically, the functioning of the internal anal sphincter can be affected by TME surgery with potential disruption of the recto‐anal inhibitory reflex arising in the ganglion cells in the rectal wall and mediated via axons that traverse the anorectal junction to serve the internal sphincter [13]. Some extrinsic autonomous nerve control also exists [14, 15], providing modulatory properties [16]. In practice, inconsistent findings suggest a lower resting and squeeze pressure in the anal canal following rectal resection, but impaired sphincter function in general has failed to show any significant correlation with LARS [17]. Indeed, ultralow coloanal resection (intersphincteric resection) destroys the intrinsic axis, the whole or parts of the internal anal sphincter and the extrinsic modulatory supply, with LARS occurring more often in patients with ultralow coloanal resection than in patients with TME [18]. Poor preoperative anal sphincter function is a strong predictor of LARS, and it should be taken into consideration at initial treatment planning.

Afferent sensory loss

The length of the retained rectal remnant, as measured on MRI scan, correlates with better functional outcome [19]. This beneficial effect is lost in irradiated patients. Both randomized control trials and epidemiological studies show a greatly increased risk of severe LARS following neoadjuvant therapy [3, 20, 21, 22, 23]. This suggests that neorectal function is highly dependent on afferent sensory input from the remaining mucosa distal to the anastomosis or from the pelvic sidewalls. Gas–stool discrimination is diminished and may cause frequent toilet visits. Furthermore, abnormal cortical processing of neorectal sensation has been shown in studies investigating the brain–gut axis, although the clinical importance of this remains unknown [24].

The negative impact of a diverting stoma

A temporary stoma is widely used after TME to avoid the consequences of an anastomotic leak. Emerging evidence shows that a diverting stoma may increase the risk of developing LARS [25, 26, 27], even when adjusted for tumour height [28], although the literature is still conflicting. The precise aetiology is not known, but it could be related to diversion colitis or to changes in epithelial function of the terminal ileum, causing bile acid malabsorption, small bowel bacterial overgrowth or bacterial recolonization of the colon after stoma reversal.

Autonomic denervation

Food intake strongly stimulates faecal urgency in LARS patients, and an accentuated gastrocolic reflex can be detected [29]. This is probably caused by autonomic denervation of the neorectum, even if the bowel has its own neural network that is able to work independently of extrinsic sympathetic or parasympathetic innervation. The integrated autonomic function relies on extrinsic innervation. In general, the sympathetic nerves inhibit peristalsis whereas the parasympathetic nerves promote it. After rectal resection, the bowel proximal to the anastomosis is left without parasympathetic and – to some extent – without sympathetic extrinsic innervation due to central vessel ligation, causing damage to the sympathetic supply from the superior hypogastric plexus in the proximity of the aorta. The increased motility of the colon due to the sympathetic denervation of the left colon seems to be a major cause of the fragmentation and urgency with LARS.

Chemotherapy and neoadjuvant radiotherapy

Chemotherapy often induces acute gastrointestinal symptoms. Although these are often reversible when chemotherapy is completed, it may contribute to chronic long‐term gastrointestinal symptoms. Neoadjuvant radiotherapy causes a more substantial impact on bowel function in most studies, even when confounding factors are removed [3, 28]. Although modern radiotherapy with intensity‐modulated radiation therapy and volumetric‐modulated arc therapy aims to diminish the area receiving radiation, scatter to adjacent structures, such as the small bowel, pelvic organs or pelvic sidewalls and bony structures, still occurs. In the longer term, radiation causes mucosal ischaemic and fibrotic changes, as well as initial mucosal inflammation. Cell death results in impairment of gastrointestinal physiological function and the development of chronic gastrointestinal disorders, such as small bowel bacterial overgrowth, bile acid malabsorption and pancreatic insufficiency; or it could unmask coeliac disease or lactose intolerance, causing diarrhoea, flatulence, bloating, pain or constipation [30].

SECTION II: IDENTIFYING LARS AND MONITORING OF TREATMENT

It is important to define the purpose of assessing LARS (e.g. for epidemiological use, for individual clinical use or for quality control and outcome research). LARS has been described as ‘disordered bowel function after rectal resection, leading to a detriment in quality of life’ [6]. Although pragmatic, this definition can incorporate a vast array of symptoms. A recent review revealed a list of more than 30 symptoms included in 18 different instruments to measure LARS. The most frequently reported outcomes were incontinence (97%), high stool frequency (80%), urgency (67%), evacuatory dysfunction (47%), problems with gas–stool discrimination (34%) and effects on HRQoL (80%) [31].

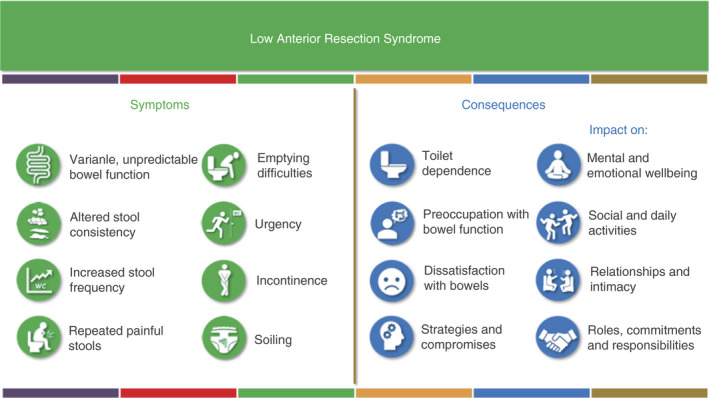

Recently, a large international consensus trilingual Delphi process with patients as the major stakeholders defined LARS as having at least one of eight symptoms resulting in at least one of eight consequences (Figure 2) after anterior resection [6].

FIGURE 2.

International consensus definition of low anterior resection syndrome (LARS). LARS is defined as one or more symptoms with one or more consequences following anterior resection [6]

Only two scoring systems address LARS specifically [31, 32, 33]: the MSKCC Bowel Function Instrument and the LARS score.

The MSKCC Bowel Function Instrument was developed and validated for patients following rectal resection. It can collect information on the complex symptomatology of LARS, especially for research purposes. It comprises 18 items resulting in three subscales, four single items and one total score for bowel function, and responses are given on a five‐point Likert scale, except for one question on the frequency of bowel movements. However, the instrument has no weighting for the different symptoms and is considered time‐consuming for both patients and healthcare professionals, and it may therefore be less useful in the clinical setting [32].

The LARS score comprises five simple questions with three or four answering categories, making it easy to use for both patients and healthcare professionals (Table 1) [11, 33]. The score can be used free of charge by anyone treating patients. The selection of items and the individual item impact of HRQoL was based on binomial regression analyses of a large patient survey. The score has a range of 0–42 points, and stratifies patients into ‘No LARS’, ‘Minor LARS’ and ‘Major LARS’ (Table 1) [11, 33]. The LARS score has been translated into more than 35 languages, validated in multiple different populations, and it has been used in many published and ongoing trials [33]. The LARS score was developed as a screening tool for identifying LARS, and in prospective cohorts it has been administered as a remote electronic monitoring tool with response rates >80% (personal communication). Due to its simplicity, it is also useful in the outpatient setting to articulate late adverse effects. The LARS score may be less useful as an outcome parameter in monitoring treatment effects, as its capability for detecting changes over time has been questioned.

TABLE 1.

| Add the scores from each 5 answers to one final score | ||

|---|---|---|

| Do you ever have occasions when you cannot control your flatus (wind)? | ||

| □ No, never | 0 | |

| □ Yes, less than once per week | 4 | |

| □ Yes, at least once per week | 7 | |

| Do you ever have any accidental leakage of liquid stool? | ||

| □ No, never | 0 | |

| □ Yes, less than once per week | 3 | |

| □ Yes, at least once per week | 3 | |

| How often do you open your bowels? | ||

| □ More than 7 times per day (24 h) | 4 | |

| □ 4–7 times per day (24 h) | 2 | |

| □ 1–3 times per day (24 h) | 0 | |

| □ Less than once per day (24 h) | 5 | |

| Do you ever have to open your bowels again within 1 h of the last bowel opening? | ||

| □ No, never | 0 | |

| □ Yes, less than once per week | 9 | |

| □ Yes, at least once per week | 11 | |

| Do you ever have such a strong urge to open your bowels that you have to rush to the toilet? | ||

| □ No, never | 0 | |

| □ Yes, less than once per week | 11 | |

| □ Yes, at least once per week | 16 | |

| Total Score: | ||

Interpretation: 0–20, no LARS; 21–29, minor LARS; 30–42, major LARS.

The score is for use free of charge for anyone treating patients with LARS.

If one item is improved, another item might change in the opposite direction and thereby challenge the aggregated score value. A simple anchor question on how much bowel function affects HRQoL has been suggested to be added to improve the clinical information and responsiveness [34].

Furthermore, not all patients with a high LARS score consider themselves bothered by bowel dysfunction [28]. Younger patients are affected more often [28, 35] and there are pronounced gender differences. Although the LARS score was developed with weight values of each item according to the impact on HRQoL, it does not include any HRQoL metric for the individual taking the score.

It needs to be emphasized that treatment of rectal cancer also causes other organ‐specific symptoms such as sexual dysfunction, voiding dysfunction and pain, and such symptoms often coexist. Other nonorgan‐specific issues, such as generalized psychosocial late adverse effects of cancer treatment, fatigue, depression, anxiety and fear of recurrence, are also associated with rectal cancer treatment. In order to cover these aspects an additional questionnaire (e.g. EORTC QLQ‐C30) can be added to patient assessment in order to optimize the evaluation.

From the literature, one could be left with the impression that LARS affects HRQoL in every patient after sphincter‐saving surgery, but this is not the case. Personality is a strong predicting factor for how clinical factors affect HRQoL [36], as many patients are grateful for being disease‐free from rectal cancer and will adapt to the change in bowel function to live happily and relatively unaffected [28]. In addition, the coexistence of other clinical factors, such as sexual dysfunction, voiding dysfunction and psychosocial distress, also affect HRQoL [35].

Currently, the LARS International Collaborative Group is working to develop a more comprehensive scoring system [6]. The results are still pending on the scoring system. A simplified solution could be to score individual items and to follow their evolution over time and as a consequence of treatments.

SECTION III: PREVENTION OF LARS

Discussing risk with patient ahead of rectal surgery – shared decision‐making

Discussions must take place prior to the surgery so that patients can understand the consequences and risks of deciding whether a low anterior resection or an abdominoperineal excision would give them a better long‐term outcome in terms of function.

The POLARS study involved 463 UK and 938 Danish patients and reviewed the LARS score in a total of 1401 individuals [37]. A variety of predictors were selected, based on detailed literature review and advanced statistical methods. The following items were found to contribute to the likelihood of developing LARS: age, gender, TME versus PME, tumour height, use of a defunctioning stoma and preoperative radiotherapy.

It is hoped that the POLARS score could be a valuable tool for preoperative patient counselling, but it still lacks prospective validation.

Altering outcome

Type of anastomosis

As pointed out under Section I, the reconstruction technique (colonic J‐pouch or side‐to‐end) is a factor that is very much in the surgeon's control and has been shown to improve bowel function in the first 12–18 months [9].

Ileostomy – and the timing of closure

A defunctioning ileostomy is often used to protect a low anastomosis. However, as previously reported, it is thought that the use of an ileostomy may have an impact on long‐term bowel function and HRQoL. A systematic review [38] of four studies (227 participants) showed that having an ileostomy is associated with twice the risk of suffering from LARS. This may be due to a difference in height of the anastomosis and/or timing of the closure. Keane et al. [27] randomized 112 patients with defunctioning ileostomy after anterior resection to early (8–13 days) versus late closure (>12 weeks). Although the patients who had an early closure had fewer problems with soiling, no reduction in LARS was observed. Overall, 66% of patients in that study had major LARS. The low height of anastomosis might explain the correlation between a diverting ileostomy and bad outcomes.

Radiotherapy

Neoadjuvant radiotherapy for low rectal cancers is known to put patients at an increased risk of LARS when controlled for confounding factors [3, 28]. It is imperative that oncological results are not compromised in terms of treatment. However, there is a huge variation in guidelines for the use of neoadjuvant radiotherapy between countries, indicating a potential overuse. Emerging evidence now shows that selected patients with good prognosis do not benefit from neoadjuvant radiotherapy from an oncological point of view [39, 40], and may therefore benefit from a functional point of view by avoiding this. Further, many centres are introducing total neoadjuvant therapy (requiring a higher dose of chemoradiotherapy) in an attempt to induce a clinical complete response (cCR), which might avoid or defer the need for a resection.

In a study comparing HRQoL and functional outcomes with watchful surveillance and with resection, although function was better with the former, 36% of patients still experienced major LARS compared with 67% in the resected group at 2‐year follow‐up [41].

Long‐term follow‐up has suggested that cCR rates are variable (ranging from 10% to 78%) [7]. Those who recur or fail to respond end up having a resection, and may have a much higher risk of major LARS. This risk should be discussed with the patient before offering this approach.

Until the results of longer term trials are known it must be considered that the possibility of using a higher radiation dose may lead to an increased risk of major LARS. Good‐quality functional outcome data following watchful waiting strategies and including functional outcomes of salvage surgery when required are still needed.

Local excision of early rectal cancers

Another tempting approach to preserve rectal function in rectal cancer is local excision of early rectal cancers followed by close follow‐up. Such an approach needs to be oncologically safe but must also consider the long‐term functional outcomes. A randomized French study failed to show any advantage with a combined endpoint including functional outcomes [42], but ongoing studies on the same issue are awaited with interest [43].

SECTION IV: RECOMMENDED WORK‐UP

Safety concerns

Physicians should ensure that there is no underlying ‘organic’ lesion that may explain a patient's symptoms after surgery (e.g. radiation‐related mucosal lesions, anastomotic stricture, tumoural local recurrence). This needs a minimal work‐up, at least digital rectal examination and proctoscopy to rule out anastomotic strictures. Since most of these patients have been operated on for rectal cancer, the oncological follow‐up will detect any local recurrence or postoperative complication (e.g. anastomotic leakage) [44, 45].

The role of the gastroenterologist

The first step for all physicians taking care of a patient is to evaluate the patient's symptoms and their impact on HRQoL (see above). The gastroenterologist may also help to rule out any potential ‘organic’ lesions and specific cause of diarrhoea by appropriate investigations [30]. These also include perianal lesions related to soiling and/or radiation.

There are no data in the literature showing how preoperative bowel function may affect postoperative functional outcome. However, clinical experience shows that preoperative irritable bowel syndrome, functional diarrhoea or constipation may affect postoperative functional outcome in different ways: in some patients, surgery will result in the worsening of symptoms whereas in others it may have a more positive impact (e.g. a patient with distal constipation may improve after rectal excision). Physicians should also check for medications that may have a negative impact on intestinal transit. These medications may have been prescribed for misdiagnosed ‘diarrhoea’ (which is very often clustering rather than actual diarrhoea) or constipation (doses may be adapted), or for extraintestinal reasons (e.g. opioids, antidepressants). This is very important for the medical management of LARS.

Endoscopy

Apart from routine postoperative screening, endoscopy is not mandatory in all patients presenting with LARS. It may be useful when radiation‐induced colitis or local tumour recurrence is suspected. If the preoperative colonoscopy was not complete because of an obstructive tumour, a colonoscopy should be performed in the 6 months following rectal surgery in order to rule out a synchronous tumour or polyp that should be adequately treated. This is a rare situation. Anastomotic strictures can be easily diagnosed in coloanal anastomosis or if the anastomosis can be digitally assessed. In other cases, endoscopy may help to rule out anastomotic strictures and to perform endoscopic dilation [46].

Anorectal physiology

Anorectal manometry may be useful [17, 47, 48] not as a diagnostic tool but to guide biofeedback therapy. It may help to quantify anal sphincter contraction and determine whether duration and/or amplitude should be targeted by the biofeedback. Furthermore, it may demonstrate evidence of outlet obstruction that may benefit from biofeedback. However, the assessment of pouch/colonic sensitivity to balloon distension is not useful and should be performed cautiously.

Endoanal ultrasonography is not mandatory, since it rarely impacts the treatment strategy. Evidence of anal defect will very rarely justify a specific treatment. Moreover, in patients who underwent intersphincteric resection the presence of anal sphincter defects is useless. There is no room for specialized tests such as electromyography or nerve latency assessment in the context of LARS.

SECTION V: BEST SUPPORTIVE CARE

Patient motivation and expectations

Many patients have the perception prior to surgery or stoma reversal that their bowel function will return to normal. The focus at the beginning of treatment is on survival and cancer cure; patients rarely predict that they will have potential functional problems [7].

For these reasons, it has been reported that only one third of patients (32.7%) will visit a health professional for advice or treatment for bowel problems after surgery [49].

Moreover, rectal cancer specialists often do not have a thorough understanding of which symptoms of bowel dysfunction truly matter to the patient, or how these symptoms affect HRQoL. As an example, few specialists recognize the importance of flatus incontinence for patients. [5].

In patients with LARS, the most frequently reported concerns are finding toilets when away from home, getting to the toilet in time, emitting odour in social situations, experiencing bowel accidents, having a sense of lack of bowel control and knowing what foods to eat when dining out [49].

Patients often develop their own strategies to help reduce the risk of incontinence and increase protection against leakage or soiling. Common strategies include antidiarrhoeal medication, dietary manipulation, skin care strategies and protection of underwear with pads, but also staying at home or near toilets if possible. ‘Trial and error’ essentially represents the strategy adopted by patients to discover the most effective way to manage LARS [8].

Diet, laxatives, constipating agents and medications

Up to 96% of patients report a change in diet. Changes usually involve intake of high‐fibre low‐fat food, avoidance of wine, cold beverages and spicy or stimulating food. However, a high content of insoluble fibre may worsen diarrhoea, the frequency of bowel movements and bloating [50]. Soluble fibre (bulking agents) should be preferred since it is better tolerated and may be beneficial in decreasing clustering and improving stool consistency, provided adequate doses are taken (clinical experience of the panel). The use of probiotics does not seem to alter the postoperative bowel function associated with LARS [51]. Inappropriate dietary habits should also be avoided, and patients might benefit from a consultation with a specialized dietician [52, 53, 54].

Loperamide is one of the most commonly used medications for bowel control, together with sitz bath or local ointments for perianal soreness or itching. Protection of underwear with pads or other absorbents is usually reported. Enemas are also used to optimize incomplete emptying or to plan defaecation.

5‐HT3 antagonists (Ramosetron, in particular) and bile acid sequestrants (colesevelam) have shown interesting preliminary results, but they still need further evaluation in patients with LARS [55].

Unfortunately, in the absence of structured guidance and due to a wide variability of symptoms with different effects on patients’ lives, conservative measures often yield inconsistent results. Their impact on patient satisfaction and HRQoL is doubtful and still poorly supported by evidence [56].

Pelvic floor rehabilitation

Although few studies have been published about rehabilitation in patients suffering from LARS, results are encouraging. The majority of studies reported improvement in stool frequency, incontinence episodes, severity of faecal incontinence and HRQoL after pelvic floor muscle training and biofeedback [57]. Moreover, irradiated patients show short‐ and long‐term results comparable to those of nonirradiated patients, despite the higher degree of incontinence at baseline [58]. Table 2 summarizes the potential benefits for patients with LARS of each component of pelvic floor rehabilitation.

TABLE 2.

Pelvic floor rehabilitation: possible benefits for patients with low anterior resection syndrome

| Component | Acronym | Expected benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Pelvic floor muscle training | PFMT | May reduce leakage by improving the structural support, timing and strength of automatic contractions |

| Biofeedback training | BF | Can help patients by optimizing their motor response through visual and hearing signals, lowering the threshold for the discrimination of a rectal sensation of distension and synchronizing voluntary contraction of the external anal sphincter in response to such distension |

| Rectal balloon training | RBT | May improve rectal sensitivity by stepwise reductions in rectal balloon distension, in order to distinguish smaller rectal volumes, tolerate urgency by using progressive distension or using a voluntary anal squeeze to counteract the recto‐anal inhibitory reflex in response to rectal filling |

Despite this, the different protocols used regarding duration of training, method and application modality still do not allow firm conclusions, in particular with respect to patient selection.

However, a multimodal approach, managing all the rehabilitative techniques according to the individual needs of the patient, could significantly improve symptoms more than a single technique alone [59].

SECTION VI: TRANSANAL IRRIGATION

Patient selection

Patient selection for transanal irrigation (TAI) as a treatment for LARS will depend on the severity of symptoms. Supportive care should have been initiated and shown to be insufficient, and any spontaneous improvement of the patient's situation should be ruled out [60].

Patient selection will also have to focus on the patient's mobility and physical ability to perform TAI on a regular basis. The irrigation process itself needs some training and mental capacity. For this reason, it is absolutely mandatory to provide patients with the support of experienced staff who will provide assistance not only during the hospital stay but (more importantly) also at home, until the patient is able to perform TAI autonomously [61].

Although perforation can be regarded as a rare complication [62], a rectal and endoscopic examination to exclude any anatomical anomalies will allow TAI to be safely undertaken. In order to keep this risk as low as possible intensive and standardized training should be mandatory. In patients with postoperative stenosis, the use of a soft Foley catheter as an alternative to the more rigid (commercially available) irrigation systems can be considered.

Studies dealing with TAI in patients with LARS or symptoms which could be attributed to LARS describe a significant effect of the treatment both in cases of long‐term history of LARS following rectal resection [63] and if it is used early as a prophylactic measure [64, 65, 66].

How to perform transanal irrigation

In general, all available products can be classified into the following categories: gravity‐based devices, pressure‐driven systems and electric‐driven systems (with a pump). The rectal catheter can be either cone shaped, as for colostomy irrigation, or a rectal balloon catheter. If a rectal balloon catheter is used in LARS patients it is advised only to inflate the balloon to a minimum to control leakage of irrigation fluid during instillation, due to the risk of inflating the balloon in the area of the anastomosis [67].

The acceptable rates of infusion are 200–300 ml/min [67]. A volume of 500 ml is recommended during the first sessions, which can gradually be increased to a maximum of 1 L; however, the definitive volume will be an individual decision and has to be decided on a case‐to‐case basis.

A practical guide to TAI is provided in Appendix 1. The most common problems (and possible solutions) that patients face at the beginning with TAI are summarized in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Problem‐solving in transanal irrigation (TAI)

| Problem | Solution |

|---|---|

| Introduction of the catheter | Check of the patency of the anastomosis |

| Exclusion of a possible stenosis | |

| Change the type of catheter | |

| Additional application of lubricant | |

| Hands‐on training with the therapist | |

| Uncontrolled loss of water during TAI | Additional insufflation of the balloon |

| Retraction of the catheter tip to the anus if it has been introduced too high | |

| Hands‐on training with the therapist | |

| Pain during irrigation | Exclusion of anatomical problems |

| Slower irrigation to avoid spasm of the colon | |

| Hand warm water | |

| Electric‐driven systems? | |

| Missing effect of TAI | Check if toilet time has been sufficiently long |

| Missing satisfaction by the patient | Increase irrigation volume or repeat TAI (2–3/day) |

| Addition of oral laxatives | |

| TAI disturbs daily activities | Discuss with the patient the activities which are impaired by TAI and toilet time |

| Educate patients to perform TAI at any time of the day (not only during their ‘old’ regular toilet times), in accordance with their plans (e.g. commitment early in the morning → TAI on the evening before, etc.) |

SECTION VII: WHEN IRRIGATION FAILS

The role of the team and the gastroenterologist

A multidisciplinary team (MDT), including a gastroenterologist, is recommended before, during and after TAI. In case of failure of TAI following appropriate troubleshooting for practical issues or the need for adjuvant use of medication, the gastroenterologist should readdress possible underlying gastrointestinal conditions contributing to LARS. If a specific cause is diagnosed and treated, TAI might successfully be reinitiated [30].

Antegrade irrigation

Antegrade irrigation can be performed through a percutaneous endoscopic colostomy (PEC), an appendicostomy or through an ileal neoappendicostomy. In a meta‐analysis of 17 studies on the treatment of faecal incontinence and constipation, antegrade irrigation was successful in 74% of patients [68].

Series of antegrade irrigation after rectal resection are small. Stenosis of the stoma in cases of appendicostomy or ileal neoappendicostomy are not infrequent. Percutaneous endoscopic caecostomy is a method to avoid this complication.

The largest published series of antegrade irrigation in LARS includes 25 patients. At the end of follow‐up, 16% of catheters were removed and the rate of definitive colostomy was 12%, meaning that 88% of the treated patients did not need a stoma in the long term. The LARS score decreased from 33 to 4 [69]. A second series with 10 patients was published in 2019 [70]. An improvement was shown in both incontinence (the Wexner score decreased from 14 to 3 after treatment) and the Gastrointestinal Quality of Life index (GIQLI) score (decreasing from 71 to 118). These 10 patients were included in the previously mentioned series [69]. Complications of antegrade enema are local pain and sweating, which occur in around one third of patients. Chronic abdominal pain is rare. In order to achieve the best results, the medical team must have the human and material resources to perform it adequately.

Sacral nerve modulation and tibial stimulation

Sacral nerve stimulation (SNS) or tibial nerve stimulation are two modalities of treatment that aim to improve symptoms through the modulation of sacral nerve.

SNS is a two‐stage surgical procedure. The first stage consists of a 2–4‐week testing period. If there is a good response, a second stage with implantation of the definitive neuromodulator is performed. It is a safe procedure with minimal morbidity. It is generally performed under local anaesthesia or mild sedation.

A positive response is defined as a reduction of more than 50% of the incontinence episodes, LARS score or the objective measure decided by the treatment group. There is difficulty in choosing the best method to evaluate response in patients with LARS (incontinence, urgency, fragmentation). This difficulty is increased by the fact that this treatment can take several months to show its complete effectiveness due to the multifactorial characteristics of LARS itself.

A systematic review of SNS in LARS patients showed an improvement of symptoms in 94% of patients overall (74% based on intention to treat) in those who underwent permanent implantation [71]. It also showed an improvement in the ability to defer defaecation and in HRQoL scores. However, this only comprised 43 patients from seven published studies. More evidence is needed to improve the selection criteria for this procedure. SNS must be offered only when other conservative measures have failed.

Tibial nerve stimulation consists of the stimulation of the tibial nerve at the ankle in 30‐min sessions. It is less invasive, simpler and cheaper than SNS. However, the results are less promising than SNS.

Tibial nerve stimulation can be either percutaneous or transcutaneous, with similar results with both approaches [72].

Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS) has been evaluated in two short series with varying results [73, 74]. In a recent randomized trial comparing PTNS with TAI, both treatments improved the LARS score but this was only significant in the TAI group [75].

Ongoing trials on nerve modulation in LARS are reported in Table 4.

TABLE 4.

Ongoing trials on nerve modulation in low anterior resection syndrome (LARS)

| Name | ID | Type of modulation | Site | Patients |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SANLARS Trial | NCT03598231 | SNS | Hospital Vall d’Hebron, Barcelona, Spain | 36 |

| RESTORE Trial | NCT04066894 | SNS | MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, USA | 60 |

| Tibial stimulation in LARS a | NCT02177084 | PTNS | St Orsola Hospital, Bologna, Italy | 12 |

| PTNS in LARS patients a | NCT02517853 | PTNS | Hospital Vall d’Hebron, Barcelona, Spain | 41 |

Abbreviations: PTNS percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation; SNS sacral nerve stimulation.

Terminated.

Which type of stoma in case of failure?

Stoma formation can be proposed to patients with severe LARS with refractory symptoms and impaired HRQoL as a final treatment option. The mechanism of action seems to be multifactorial and on an afferent and central level. A stoma can be performed both as a diverting ileostomy or colostomy (without excision of the neorectum) or as abdominoperineal excision with end colostomy. There is no evidence on what is the best option in this group of patients.

Patients must be informed that at least 20% of temporary stomas are never reversed when performed for acute or chronic complications of sphincter‐preserving surgery (including LARS).

Patients must have the evidence on each type of stoma to have real expectations. Discussion with patients who already have stomas could be very useful. Information must include advantages (no urgency, no incontinence, no anal pain) and disadvantages (parastomal hernia, prolapse, dermatitis, leakage). The information material must include the evidence of similar (and even increased) HRQoL scores of patients with stoma when compared with patients who developed complications after sphincter‐preserving surgery [76, 77]; however, patients should be aware that, until now, there is no evidence of a change in HRQoL in patients who undergo stoma formation due to refractory LARS.

Regarding stoma type, some other aspects must be discussed with patients (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Advantages and disadvantages associated with the different types of stoma

| Ileostomy | Colostomy |

|---|---|

|

A temporary ileostomy is easy to perform and does not endanger irrigation of the neorectum A temporary ileostomy is associated with increased dehydration, renal lithiasis, dermatitis, prolapse and hernia |

Formation or closure of a colostomy could endanger viability of neorectum due to injury to the marginal artery; therefore, a resection of the anastomosis and an intersphincteric rectal resection with closure of the anus is often needed. This is not easy and may cause pelvic complications A diverting colostomy of the left colon is not easy in patients with previous low anterior resection, and may endanger the irrigation of the neorectum with subsequent severe pelvic complications |

SECTION VIII: THE PATIENT PERSPECTIVE

The decision‐making process for patients suffering from LARS is particularly relevant in the UK following the Montgomery ruling in 2015 [78]. In essence, in the UK this has led to a sharing of decision‐making between clinician and patient. The risks and alternatives for any procedure or operation should be discussed with the patient. For anterior resection patients, it is therefore appropriate that some form of preoperative assessment about long‐term outcome should be undertaken.

Meeting the needs of patients suffering from LARS

Patients who meet the criteria for LARS should be told and receive clear explanation that their symptoms pertain to a proper ‘syndrome’, which might be useful for them in order to better come to terms with the huge range of issues they might be going through.

Patients value the possibility of having an open, honest and supportive dialogue with medical staff reviewing their treatments and progress, which can help them keep a ‘positive’ frame of mind. The priorities of each patient are likely to be different, but being able to live an active life, enjoying their hobbies and leisure activities, walking and socializing with family and friends are all aspects that need to be emphasized when it comes to achieve a reasonable HRQoL.

In terms of a ‘pattern’ of function, patients need to be advised that they might experience ‘no’ pattern, and the average number of visits might vary each day. Movements can be triggered by several factors or gestures that are commonly performed every day (e.g. eating, lying in a particular position when going to bed); their sleep can be interrupted, and cause them to feel exhausted. They need adequate support for such issues.

Healthcare professionals need to meet the needs of patients; leaving them alone looking for answers on the Internet and on uncredited or scientifically unsound sources, might cause them more anxiety. Support networks for colorectal patients should also include well written, clear literature, with good illustrations. Patients with LARS might have had or might need a stoma at some point; they will benefit from sources to learn about stoma care, diet and exercise. The chance to ‘try out’ a bag at home, before the surgery, can also help to calm their fears. Support from experienced nurses to explain, to listen and to answer questions is vital, and they should be available when needed. This can provide reassurance and support to those who are struggling. Setting up patient‐support networks can offer the opportunity to have direct conversations with those who have gone through the same operation or path, so that patients might be more prepared for the complications. Investment is needed to investigate all aspects of LARS that impact upon the everyday lives and social interactions of patients. Sleep disturbance, loss of libido and problems resuming a full sex life need more attention, and strategies should be planned to detect, treat and prevent them in a timely manner. The participation of patients is of crucial importance to make sure that all relevant aspects of LARS are considered.

Dissemination and future directions

LARS is a recognized problem worldwide that is caused by rectal cancer treatment and leads to severe impairment of HRQoL. The institutional recognition of the syndrome and, consequently, of the reimbursement for the available treatments, is variable among countries. Most clinicians treating patients with LARS are surgeons involved in rectal cancer treatment, but their knowledge about therapeutic solutions to deal with the specific problems is often poor and they may need help from other clinicians. Since the number of rectal cancer survivors has increased with the significant improvements in treatment and survival during the last decade, it is time for a paradigm shift in the follow‐up of colorectal cancer with increased focus on late adverse effects [79].

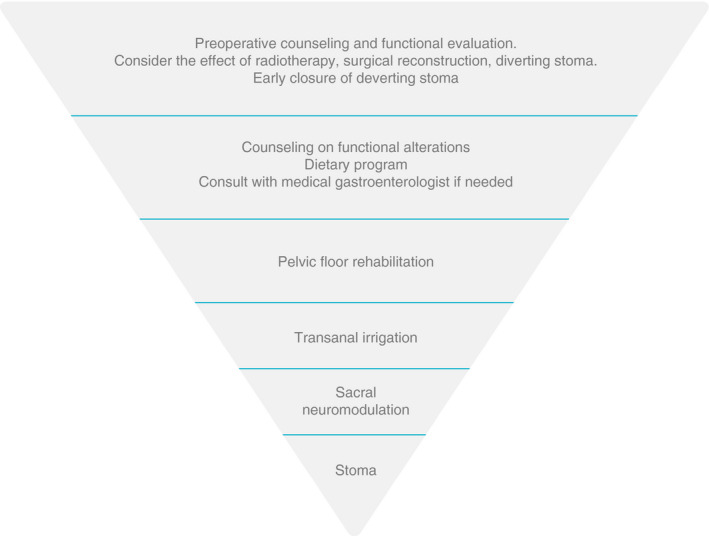

Although surgeons worldwide are informed about LARS by societies, congresses and the scientific literature, there are still large gaps in knowledge about the treatment of LARS. A limited number of randomized controlled trials for LARS, mainly carried out by surgeons, are available [75, 80, 81, 82] emphasizing the lack of sound evidence. The recommendation for the present guidance is therefore partly based on expert opinion. A potential treatment chart is provided in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

A suggested treatment chart for patients with low anterior resection syndrome

An easy‐to‐use, step‐up treatment algorithm has been proposed [56], giving an overview of treatments available. Surgeons are specialists in treating rectal cancer but not always specialists in functional colorectal diseases and may need to seek help from other clinicians.

We may need to think of different approaches to the management of LARS, given the mixed aetiological factors underlying the condition (see Section I). As stated above, in current practice, LARS patients are often treated as one entity, but we could think of separate treatment pathways for faecal incontinence, clustering and constipation. It is imaginable that different pathways could be treated by different specialists and a multidisciplinary team is desirable. Multidisciplinary teams might avoid inappropriate treatments, and lead to tailored patient approach.

All members of the multidisciplinary team need to be educated about LARS: gastroenterologists, radiation oncologists, pelvic floor nurses and patients. An international education programme with a multidisciplinary board to help treat difficult cases can be used as a platform to share experiences and to develop new therapies and techniques. Troubleshooting videos to educate specialists and to inform patients could also be a useful resource that could be developed by scientific societies and entities, potentially with the collaboration and support of medical companies, to spread knowledge about LARS diagnosis and treatment all over the world. Apps represent another poorly explored tool that could be of help in all these aims, ideally with the input and support of international scientific societies. Such platforms could collect data and help in specific research questions, and therefore stimulate high‐quality research on the effects of individual treatments in order to fill the gaps in the current treatment of LARS.

ETHICAL APPROVAL AND INFORMED CONSENT

Ethics approval, patient consent and clinical trial registration are not applicable/not relevant. Permissions to reproduce Figure 2 was obtained from the author – pending from Wiley (open access publication).

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

KPN and HR are members of the scientific board for transanal irrigation of Coloplast. CIMB served as speaker for Coloplast and Medtronic. FZ has served as consultant/speaker for Coloplast, Takeda, Allergan, Biocodex, Vifor Pharma, Mayoly Spindler, Ipsen, Abbott, Reckitt Benckiser and Alfasigma. PC is an Advisory Board member of Coloplast A/S and Wellspect Inc., and received a research grant from MBH International. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to report. The panel was offered external support by Coloplast for planning the meetings and for the organization of the work. Coloplast A/S facilitated the face‐to‐face meetings and teleconferences, but did not have any influence on the priorities of the MANUEL project and final manuscript.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

The manuscript has been written in collaboration and with participation of the entire MANUEL group

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Aelwen Emmett for serving as the lay expert.

APPENDIX 1. PRACTICAL GUIDANCE FOR TRANSANAL IRRIGATION (TAI)

WHEN SHOULD TAI BE INITIATED?

In a joint Austrian/Swiss study, patients were included with a median duration of LARS of 19 (9–48) months before TAI was started [64]. More recently there has been more emphasis on an earlier introduction of TAI following rectal resection. Martellucci et al. [83] evaluated the severity of LARS 30–40 days after completion of rectal resection or closure of the protective stoma, before proceeding to TAI treatment.

In an attempt to prevent severe problems from LARS, a recent multicentre randomized clinical trial [65] tried to evaluate the effect of TAI as a ‘prophylactic’ measure started after ileostomy closure in patients following resection for ultralow rectal cancer and a median anastomotic height of 3 cm from the dentate line. Patients receiving TAI showed a higher number of defaecation episodes per daytime at 1‐week follow‐up compared with the control group. However, after 1 and 3 months, patients with TAI showed significantly better results compared with patients on supportive therapy only, thus indicating that a certain period after the start of bowel motility should have passed before TAI is started.

TIME REQUIRED AND THE MOST APPROPRIATE INTERVALS BETWEEN IRRIGATION SESSIONS

Most patients suffering from LARS complain about the high number of unproductive stool episodes at any time of the day (and night) and the sudden strong faecal urgency, which impair HRQoL. Only a sufficient emptying of the colon and neorectum will improve this situation. It has been shown that TAI is capable of achieving an emptying up to the transverse colon [84]. Appropriate time for evacuation is an important prerequisite for a successful outcome after TAI. In the randomized clinical trial of ‘prophylactic’ TAI [65], a median time of 47 min (range 22–70 min) on the toilet at 1 week, 44 min (30–65 min) at 1 month and 45 min (30–60 min) at 3 months, were reported after irrigation with 1000 ml of water. Although a significant reduction of defaecation episodes during day and night could be observed, a further evaluation after 12 months showed that nine patients in the TAI group decided to stop TAI and changed to supportive therapy only between 3 and 12 months. Eight patients reported the long duration of the emptying process as the reason for their decision to stop TAI [66]. Furthermore, after 12 months, the median volume of water used for irrigation in the remaining TAI patients was 600 ml (range 200–1000 ml) compared to 1000 ml/24 h according to the protocol used for the first 3 months [66]. Five patients were performing irrigations every 24 h, three patients every 48 h and two patients not on a regular schedule but at least twice a week. In general, it must be accepted that there are no strict recommendations regarding the volume and intervals of irrigations. It might be advisable to make the final decision based on the patient's individual situation (e.g. profession, family situation, daily activities) [85]. Reduction of irrigation volume will be associated most probably with a shorter toilet time, but also with shorter intervals between irrigations. In this context, it might be desirable to gain more information about the correlation between irrigation volume and the intervals between irrigation procedures.

SHOULD TAI IN PATIENTS WITH LARS BE REGARDED AS A LIFELONG THERAPY OR CAN IT BE TERMINATED AT SOME POINT?

Spontaneous recovery from LARS can be expected within a period of 6–12 months, which raises the question on how long patients will need to use TAI. Since most studies dealing with TAI as a therapy for LARS included patients who already had a longer history, and in whom a spontaneous recovery could not be expected, it must be taken into account that there might be a subset who will require TAI as a lifelong measure to ensure an acceptable HRQoL. However, in patients in whom TAI was started immediately (or very early) after rectal resection, there is some evidence that they might be able to stop the procedure after a certain period [66]. Of note, it has been proposed that the use of TAI might have a rehabilitative effect on the colon, leading to a recovery of the disturbed motility following rectosigmoid resection. However, this needs to be further elucidated.

PATIENT EDUCATION, TROUBLESHOOTING, PRACTICE GUIDANCE, PATIENT EMPOWERMENT

The regular use of TAI means a significant change for the life of every patient. Therefore, successful application of TAI is strongly related to an intensive counselling, hands‐on training and continuous support from an experienced medical staff. A positive compliance with this treatment is mainly dependent on the presence and aid of specially trained stoma/incontinence therapists who can instruct and accompany patients [65, 66, 76, 77].

Funding information

None.

Contributor Information

Peter Christensen, Email: petchris@rm.dk, @PeterCh12345.

Eloy Espín‐Basany, @eloiespin.

Gianluca Pellino, @GianlucaPellino.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

REFERENCES

- 1. Renner K, Rosen HR, Novi G, Hölbling N, Schiessel R. Quality of life after surgery for rectal cancer: do we still need a permanent colostomy? Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42(9):1160–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pachler J, Wille‐Jørgensen P. Quality of life after rectal resection for cancer, with or without permanent colostomy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD004323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Emmertsen KJ, Laurberg S, Rectal Cancer Function Study Group . Impact of bowel dysfunction on quality of life after sphincter‐preserving resection for rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2013;100(10):1377–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bryant CL, Lunniss PJ, Knowles CH, Thaha MA, Chan CL. Anterior resection syndrome. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:e403–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chen TY, Emmertsen KJ, Laurberg S. Bowel dysfunction after rectal cancer treatment: a study comparing the specialist's versus patient's perspective. BMJ Open. 2014;4(1):e003374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Keane C, Fearnhead NS, Bordeianou L, Christensen P, Basany EE, Laurberg S, et al. International consensus definition of low anterior resection syndrome. Colorectal Dis. 2020;22:331–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. van der Heijden JAG, Thomas G, Caers F, van Dijk WA, Slooter GD, Maaskant‐Braat AJG. What you should know about the low anterior resection syndrome – clinical recommendations from a patient perspective. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2018;44(9):1331–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) . Colorectal cancer NICE guideline [NG151]. [E2] Optimal management of low anterior resection syndrome. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng151 (accessed 23 November 2020). [PubMed]

- 9. Parc Y, Ruppert R, Fuerst A, Golcher H, et al. Better function with a colonic J‐pouch or a side‐to‐end anastomosis? A randomized controlled trial to compare the complications, functional outcome, and quality of life in patients with low rectal cancer after a J‐pouch or a side‐to‐end anastomosis. Ann Surg. 2019;269(5):815–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Machado M, Nygren J, Goldman S, Ljungqvist O. Functional and physiologic assessment of the colonic reservoir or side‐to‐end anastomosis after low anterior resection for rectal cancer: a two‐year follow‐up. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48(1):29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Juul T, Ahlberg M, Biondo S, Emmertsen KJ, Espin E, Jimenez LM, et al. International validation of the Low Anterior Resection Syndrome Score. Ann Surg. 2014;259(4):728–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Juul T, Elfeki H, Christensen P, Laurberg S, Emmertsen KJ, Bager P. Normative data for the low anterior resection syndrome score (LARS Score). Ann Surg. 2019;269(6):1124–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. O'Kelly TJ. Nerves that say NO: a new perspective on the human rectoanal inhibitory reflex. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1996;78(1):31–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kinugasa Y, Arakawa T, Murakami G, Fujimiya M, Sugihara K. Nerve supply to the internal anal sphincter differs from that to the distal rectum: an immunohistochemical study of cadavers. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2014;29(4):429–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stelzner S, Böttner M, Kupsch J, Kneist W, Quirke P, West NP, et al. Internal anal sphincter nerves – a macroanatomical and microscopic description of the extrinsic autonomic nerve supply of the internal anal sphincter. Colorectal Dis. 2018;20(1):O7–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mills K, Chess‐Williams R. Pharmacology of the internal anal sphincter and its relevance to faecal incontinence. Auton Autacoid Pharmacol. 2009;29(3):85–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lee SJ, Park YS. Serial evaluation of anorectal function following low anterior resection of the rectum. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1998;13(5–6):241–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kupsch J, Jackisch T, Matzel KE, Zimmer J, Schreiber A, Sims A, et al. Outcome of bowel function following anterior resection for rectal cancer‐an analysis using the low anterior resection syndrome (LARS) score. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2018;33(6):787–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bondeven P, Emmertsen KJ, Laurberg S, Pedersen BG. Neoadjuvant therapy abolishes the functional benefits of a larger rectal remnant, as measured by magnetic resonance imaging after restorative rectal cancer surgery. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41(11):1493–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chen TY, Wiltink LM, Nout RA, Meershoek‐Klein Kranenbarg E, Laurberg S, Marijnen CA, et al. Bowel function 14 years after preoperative short‐course radiotherapy and total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: report of a multicenter randomized trial. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2015;14(2):106. e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Juul T, Ahlberg M, Biondo S, Espin E, Jimenez LM, Matzel KE, et al. Low anterior resection syndrome and quality of life: an international multicenter study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57(5):585–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bregendahl S, Emmertsen KJ, Fassov J, et al. Neorectal hyposensitivity after neoadjuvant therapy for rectal cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2013;108(2):331–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bregendahl S, Emmertsen KJ, Lous J, Laurberg S. Bowel dysfunction after low anterior resection with and without neoadjuvant therapy for rectal cancer: a population‐based cross‐sectional study. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15(9):1130–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Haas S, Faaborg PM, Gram M, et al. Cortical processing to anorectal stimuli after rectal resection with and without radiotherapy. Tech Coloproctol. 2020;24(7):721–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Floodeen H, Lindgren R, Hallbook O, Matthiessen P. Evaluation of long‐term anorectal function after low anterior resection: a 5‐year follow‐up of a randomized multicenter trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57(10):1162–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gadan S, Floodeen H, Lindgren R, Matthiessen P. Does a defunctioning stoma impair anorectal function after low anterior resection of the rectum for cancer? A 12‐year follow‐up of a randomized multicenter trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2017;60(8):800–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Keane C, Park J, Öberg S, et al. Functional outcomes from a randomized trial of early closure of temporary ileostomy after rectal excision for cancer. Br J Surg. 2019;106(5):645–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sandberg S, Asplund D, Bisgaard T, Bock D, González E, Karlsson L, et al. Low anterior resection syndrome in a Scandinavian population of patients with rectal cancer: a longitudinal follow‐up within the QoLiRECT study. Colorectal Dis. 2020;22(10):1367–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Emmertsen KJ, Bregendahl S, Fassov J, Krogh K, Laurberg S. A hyperactive postprandial response in the neorectum–the clue to low anterior resection syndrome after total mesorectal excision surgery? Colorectal Dis. 2013;15(10):e599–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Andreyev J. Gastrointestinal symptoms after pelvic radiotherapy: a new understanding to improve management of symptomatic patients. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8(11):1007–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Keane C, Wells C, O'Grady G, Bissett IP. Defining low anterior resection syndrome: a systematic review of the literature. Colorectal Dis. 2017;19(8):713–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Temple LK, Bacik J, Savatta SG, Gottesman L, Paty PB, Weiser MR, et al. The development of a validated instrument to evaluate bowel function after sphincter‐preserving surgery for rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48(7):1353–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Emmertsen KJ, Laurberg S. Low anterior resection syndrome score: development and validation of a symptom‐based scoring system for bowel dysfunction after low anterior resection for rectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2012;255(5):922–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Battersby NJ, Juul T, Christensen P, Janjua AZ, Branagan G, Emmertsen KJ, et al. Predicting the risk of bowel‐related quality‐of‐life impairment after restorative resection for rectal cancer: a multicenter cross‐sectional study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2016;59(4):270–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kupsch J, Kuhn M, Matzel KE, Zimmer J, Radulova‐Mauersberger O, Sims A, et al. To what extent is the low anterior resection syndrome (LARS) associated with quality of life as measured using the EORTC C30 and CR38 quality of life questionnaires? Int J Colorectal Dis. 2019;34(4):747–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Siassi M, Weiss M, Hohenberger W, Lösel F, Matzel K. Personality rather than clinical variables determines quality of life after major colorectal surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52(4):662–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Battersby NJ, Bouliotis G, Emmertsen KJ, et al. Development and external validation of a nomogram and online tool to predict bowel dysfunction following restorative rectal cancer resection: the POLARS score. Gut. 2018;67(4):688–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Keane C, Sharma P, Yuan L, et al. Impact of temporary ileostomy on long‐term quality of life and bowel function: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. ANZ J Surg. 2020;90(5):687–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Taylor FG, Quirke P, Heald RJ, Moran B, Blomqvist L, Swift I, et al. MERCURY study group. Preoperative high‐resolution magnetic resonance imaging can identify good prognosis stage I, II, and III rectal cancer best managed by surgery alone: a prospective, multicenter, European study. Ann Surg. 2011;253(4):711–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kennedy ED, Simunovic M, Jhaveri K, Kirsch R, Brierley J, Drolet S, et al. Safety and feasibility of using magnetic resonance imaging criteria to identify patients with ‘good prognosis’ rectal cancer eligible for primary surgery: the phase 2 nonrandomized QuickSilver clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(7):961–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hupkens BJP, Martens MH, Stoot JH, et al. Quality of life in rectal cancer patients after chemoradiation: watch‐and‐wait policy versus standard resection – a matched‐controlled study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2017;60(10):1032–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rullier E, Rouanet P, Tuech JJ, Valverde A, Lelong B, Rivoire M, et al. Organ preservation for rectal cancer (GRECCAR 2): a prospective, randomised, open‐label, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;390(10093):469–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rombouts AJM, Al‐Najami I, Abbott NL, Appelt A, Baatrup G, Bach S, et al. Can we Save the rectum by watchful waiting or TransAnal microsurgery following (chemo) Radiotherapy versus Total mesorectal excision for early REctal Cancer (STAR‐TREC study)?: protocol for a multicentre, randomised feasibility study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(12):e019474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yokota M, Ito M, Nishizawa Y, Kobayashi A, Saito N. The impact of anastomotic leakage on anal function following intersphincteric resection. World J Surg. 2017;41(8):2168–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Qin Q, Ma T, Deng Y, Zheng J, Zhou Z, Wang H, et al. Impact of preoperative radiotherapy on anastomotic leakage and stenosis after rectal cancer resection: post hoc analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2016;59(10):934–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lee SY, Kim CH, Kim YJ, Kim HR. Anastomotic stricture after ultralow anterior resection or intersphincteric resection for very low‐lying rectal cancer. Surg Endosc. 2018;32(2):660–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gong X, Jin Z, Zheng Q. Anorectal function after partial intersphincteric resection in ultra‐low rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14(12):e802–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ihnát P, Slívová I, Tulinsky L, Ihnát Rudinská L, Máca J, Penka I. Anorectal dysfunction after laparoscopic low anterior rectal resection for rectal cancer with and without radiotherapy (manometry study). J Surg Oncol. 2018;117(4):710–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Nikoletti S, Young J, Levitt M, King M, Chidlow C, Hollingsworth S. Bowel problems, self‐care practices, and information needs of colorectal cancer survivors at 6 to 24 months after sphincter‐saving surgery. Cancer Nurs. 2008;31(5):389–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Yin L, Fan L, Tan R, et al. Bowel symptoms and self‐care strategies of survivors in the process of restoration after low anterior resection of rectal cancer. BMC Surg. 2018;18:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Stephens JH, Hewett PJ. Clinical trial assessing VSL#3 for the treatment of anterior resection syndrome. ANZ J Surg. 2012;82(6):420–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Jimenez‐Gomez LM, Espin‐Basany E, Marti‐Gallostra M, Sanchez‐Garcia JL, Vallribera‐Valls F, Armengol‐Carrasco M. Low anterior resection syndrome: a survey of the members of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (ASCRS), the Spanish Association of Surgeons (AEC), and the Spanish Society of Coloproctology (AECP). Int J Colorectal Dis. 2016;31(4):813–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sun V, Crane TE, Slack SD, Yung A, Wright S, Sentovich S, et al. development, and design of the Altering Intake, Managing Symptoms (AIMS) dietary intervention for bowel dysfunction in rectal cancer survivors. Contemp Clin Trials. 2018;68:61–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Jeong H, Park J. Factors influencing changing bowel habits in patients undergoing sphincter‐saving surgery for rectal cancer. Int Wound J. 2019;16(Suppl 1):71–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Dulskas A, Smolskas E, Kildusiene I, Samalavicius NE. Treatment possibilities for low anterior resection syndrome: a review of the literature. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2018;33(3):251–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Martellucci J. Low anterior resection syndrome: a treatment algorithm. Dis Colon Rectum. 2016;59:79–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Visser WS, te Riele WW, Boerma D, van Ramshorst B, van Westreenen HL. Pelvic floor rehabilitation to improve functional outcome after a low anterior resection: a systematic review. Ann Coloproctol. 2014;30:109–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Allgayer H, Dietrich CF, Rohde W, Koch GF, Tuschhoff T. Prospective comparison of short‐ and long‐term effects of pelvic floor exercise/biofeedback training in patients with fecal incontinence after surgery plus irradiation versus surgery alone for colorectal cancer: clinical, functional and endoscopic/endosonographic findings. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:1168–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Pucciani F, Ringressi MN, Redditi S, Masi A, Giani I. Rehabilitation of fecal incontinence after sphincter‐saving surgery for rectal cancer: encouraging results. Dis Colon rectum. 2008;51(10):1552–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Ribas Y, Aguilar F, Jovell‐Fernández E, Cayetano L, Navarro‐Luna A, Muñoz‐Duyos A. Clinical application of the LARS score: results from a pilot study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2017;32(3):409–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Bildstein C, Melchior C, Gourcerol G, Boueyre E, Bridoux V, Verin E, et al. Predictive factor for compliance with transanal irrigation for the treatment of defecation disorders. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23(11):2029–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Christensen P, Krogh K, Perrouin‐Verbe B, Leder D, Bazzocchi G, Petersen J, et al. Global audit on bowel perforations related to transanal irrigation. Tech Coloproctol. 2016;20(2):109–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Juul T, Christensen P. Prospective evaluation of transanal irrigation for fecal incontinence and constipation. Tech Coloproctol. 2017;21(5):363–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Rosen H, Robert‐Yap J, Tentschert G, Lechner M, Roche B. Transanal irrigation improves quality of life in patients with low anterior resection syndrome. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13(10):e335–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Rosen HR, Kneist W, Fürst A, Krämer G, Hebenstreit J, Schiemer JF. Randomized clinical trial of prophylactic transanal irrigation versus supportive therapy to prevent symptoms of low anterior resection syndrome after rectal resection. BJS Open. 2019;3(4):461–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Rosen HR, Boedecker C, Fürst A, Krämer G, Hebenstreit J, Kneist W. ‘Prophylactic' transanal irrigation (TAI) to prevent symptoms of low anterior resection syndrome (LARS) after rectal resection: results at 12‐month follow‐up of a controlled randomized multicenter trial [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 19]. Tech Coloproctol. 2020;24(12):1247–53. 10.1007/s10151-020-02261-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Emmanuel AV, Krogh K, Bazzocchi G, Crétolle C, Santacruz BG, Frischer J, et al. Consensus review of best practice of transanal irrigation in adults. Spinal Cord. 2013;51(10):732–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Chan DS, Delicata RJ. Meta‐analysis of antegrade continence enema in adults with faecal incontinence and constipation. Br J Surg. 2016;103(4):322–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Didailler R, Denost Q, Loughlin P, Chabrun E, Ricard J, Picard F, et al. Antegrade enema after total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: the last chance to avoid definitive colostomy for refractory low anterior resection syndrome and fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2018;61(6):667–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Ricard J, Quénéhervé L, Lefevre C, Le Rhun M, Chabrun E, Duchalais‐Dassonneville E, et al. Anterograde colonic irrigations by percutaneous endoscopic caecostomy in refractory colorectal functional disorders. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2019;34(1):169–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Ramage L, Qiu S, Kontovounisios C, Tekkis P, Rasheed S, Tan E. A systematic review of sacral nerve stimulation for low anterior resection syndrome. Colorectal Dis. 2015;17(9):762–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Rimmer CJ, Knowles CH, Lamparelli M, Durdey P, Lindsey I, Hunt L, et al. Short‐term outcomes of a randomized pilot trial of 2 treatment regimens of transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation for fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58(10):974–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Altomare DF, Picciariello A, Ferrara C, Digennaro R, Ribas Y, De Fazio M. Short‐term outcome of percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation for low anterior resection syndrome: results of a pilot study. Colorectal Dis. 2017;19(9):851–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Vigorita V, Rausei S, Troncoso Pereira P, Trostchansky I, Ruano Poblador A, Moncada Iribarren E, et al. A pilot study assessing the efficacy of posterior tibial nerve stimulation in the treatment of low anterior resection syndrome. Tech Coloproctol. 2017;21(4):287–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Enriquez‐Navascues JM, Labaka‐Arteaga I, Aguirre‐Allende I, Artola‐Etxeberria M, Saralegui‐Ansorena Y, Elorza‐Echaniz G, et al. A randomized trial comparing transanal irrigation and percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation in the management of low anterior resection syndrome. Colorectal Dis. 2020;22(3):303–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Kasparek MS, Hassan I, Cima RR, Larson DR, Gullerud RE, Wolff BG. Quality of life after coloanal anastomosis and abdominoperineal resection for distal rectal cancers: sphincter preservation vs quality of life. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13(8):872–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Silva MMRL, Junior SA, de Aguiar PJ, Santos ÉMM, de Oliveira FF, Spencer RMSB, et al. Late assessment of quality of life in patients with rectal carcinoma: comparison between sphincter preservation and definitive colostomy. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2018;33(8):1039–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Chan SW, Tulloch E, Cooper ES,Smith A, Wojcik W, Norman JE. Montgomery and informed consent: where are we now? BMJ. 2017;357:j2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Laurberg S, Juul T, Christensen P, Emmertsen KJ. Time for a paradigm shift in the follow‐up of colorectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2020;00:1–4. 10.1111/codi.15401. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Garfinkle R, Loiselle CG, Park J, Fiore JF Jr, Bordeianou LG, Liberman AS, et al. Development and evaluation of a patient‐centred program for low anterior resection syndrome: protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2020;10(5):e035587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Hajibandeh S, Hajibandeh S, Maw A. Meta‐analysis and trial sequential analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing high and low ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery in rectal cancer surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2020;63(7):988–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Kalkdijk‐Dijkstra AJ, van der Heijden JAG, van Westreenen HL, Broens PMA, Trzpis M, Pierie JPEN, et al. Pelvic floor rehabilitation to improve functional outcome and quality of life after surgery for rectal cancer: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial (FORCE trial). Trials. 2020;21(1):112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Martellucci J, Sturiale A, Bergamini C, Boni L, Cianchi F, Coratti A, et al. Role of transanal irrigation in the treatment of anterior resection syndrome. Tech Coloproctol. 2018;22(7):519–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Christensen P, Olsen N, Krogh K, Bacher T, Laurberg S. Scintigraphic assessment of retrograde colonic washout in fecal incontinence and constipation. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:68–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]