Abstract

Skeletal progenitor/stem cells (SSCs) play a critical role in postnatal bone growth and maintenance. Telomerase (Tert) activity prevents cellular senescence and is required for maintenance of stem cells in self‐renewing tissues. Here we investigated the role of mTert‐expressing cells in postnatal mouse long bone and found that mTert expression is enriched at the time of adolescent bone growth. mTert‐GFP+ cells were identified in regions known to house SSCs, including the metaphyseal stroma, growth plate, and the bone marrow. We also show that mTert‐expressing cells are a distinct SSC population with enriched colony‐forming capacity and contribute to multiple mesenchymal lineages, in vitro. In contrast, in vivo lineage‐tracing studies identified mTert + cells as osteochondral progenitors and contribute to the bone‐forming cell pool during endochondral bone growth with a subset persisting into adulthood. Taken together, our results show that mTert expression is temporally regulated and marks SSCs during a discrete phase of transitional growth between rapid bone growth and maintenance.

Keywords: mTert, pluripotent, postnatal bone growth, skeletal stem cells, telomerase

In long bones, osteochondral progenitor cells function during rapid bone growth while osteoadipogenic progenitors act during bone maintenance. We showed that mTert is expressed in an age‐dependent manner and marks growth‐associated osteochondral progenitor cells during transitional growth, a discrete time period between rapid bone growth and bone maintenance.

1. INTRODUCTION

Postnatal bone formation relies on skeletal progenitor/stem cells (SSCs). 1 , 2 , 3 These cells also play a key role in maintaining the hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) niche. 4 , 5 , 6 Predominantly found in the metaphyseal stroma adjacent to the vasculature, 5 , 7 SSC populations have also been identified in nonvascular stromal regions as well as in the bone marrow (BM) near/adjacent to bone. 8 In addition, bone lining cells have been implicated as a major contributor to the osteoblast lineage in response to damage. 9 Furthermore, progenitor/stem cells are present within the periosteum and function in fracture repair. Finally, chondrogenic cells from both the growth plate and the perichondrium contribute to bone formation during rapid bone growth and in response to injury. 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14

SSCs were originally defined by their ability (a) to self‐renew, using an in vitro colony‐forming unit‐fibroblast (CFU‐F) assay, (b) to differentiate into osteoblasts, chondrocytes and adipocytes, the three major cellular components of skeletal tissue, and (c) to form bone and bone marrow following transplantation. 15 , 16 While these techniques, combined with cell surface marker expression, 17 , 18 were originally considered the gold standard for defining SSCs, the advent of lineage‐tracing has allowed for the identification and functional validation of progenitor/stem cells under physiological conditions, in vivo.

Recent lineage‐tracing data indicate that SSC populations are temporally and spatially regulated with distinct populations functioning during bone growth and maintenance. 7 , 13 , 17 , 19 In addition, growth‐associated SSCs have been suggested as the predecessors to adult SSCs, implying that the SSC population is highly complex, and that a hierarchy 7 , 13 may exist among the various progenitor/stem cell populations. 7 , 19 Although there is strong interest in identifying stem cells within the skeleton, and much has been done to understand these cells in vitro, these findings are tempered by the fact that the lineage potential of cells in vitro can differ from their capacity in vivo. 20 Going forward it will be imperative that markers, and the cell populations they identify, are validated in vivo before being accepted as a SSC population.

Telomerase (Tert) activity prevents cellular senescence and is required for maintenance of stem cells in self‐renewing tissues. 21 , 22 , 23 Previously, we showed that mTert expression marks embryonic stem (ES) cells, inducible pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, and self‐renewing tissue stem cells. 24 , 25 , 26 Prior studies also have shown that telomerase is necessary for SSC self‐renewal and differentiation 27 and that a decline in telomerase activity in humans correlates with a decrease in bone homeostasis resulting in osteoporosis. 28 In addition, ectopic expression of telomerase results in increased proliferation, enhanced osteoblast differentiation, and bone formation. 29 , 30 While these studies indicate that telomerase is important for SSC function and bone homeostasis, it remains unclear whether telomerase expression marks skeletal stem cells.

Here we report that mTert is expressed in an age‐dependent manner and marks growth‐associated osteochondral progenitor cells within the long bone during a discrete time period between rapid bone growth and bone maintenance.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Mice

mTert‐rtTA mice were generated using ES cell transgenesis by targeting a single copy of the M2rtTA reverse tetracycline transactivator driven by a 4.4 kb of the mTert promoter 25 , 26 , 31 to a flippase recombination target (FRT) site targeted into safe‐haven chromatin downstream of the Col1a1 locus. 32 Correctly targeted ES clones were further analyzed using an otet‐GFP reporter construct to demonstrate reversible doxycycline‐inducible activity. A single clone was then used to generate the mTert‐rtTA mouse line used in this study. For lineage‐tracing studies, these mice were crossed with otet‐Cre 33 and R26R flox (mT/mG) 34 mice to generate mTert‐rtTA:: otet‐Cre:: R26R flox(mT/mG) trigenic mice. To induce recombination, doxycycline (Sigma) was administered either in a single injection (15 μg/g body weight) or in the drinking water (2 mg/mL in 10 mg/mL sucrose water) for up to 5 or 7 days as indicated. Mice were gamma irradiated (7 Gy) to induce bone marrow adipogenesis. mTert‐GFP 25 and wild‐type mice (Jackson Laboratory) were also used in this study. All procedures were approved by the BCH IACUC.

2.2. Isolation and differentiation of marrow stromal cells

Long bones were collected and the BM was flushed by centrifugation to obtain marrow stromal cells. 35 Following red blood cell (RBC) lysis, 105 to 106 cells were plated in MesenCult MSC Basal Medium supplemented with MesenCult Mesenchymal Stem Cell Stimulatory Supplement (STEMCELL Technologies), glutamine and antibiotics. Adherent cells were analyzed after 24 hours and colonies were visualized after 2 weeks. To promote differentiation, cells were cultured to confluence and then the media was supplemented with either 50 μg/mL ascorbic acid (Sigma), 7 mM β‐glycerophosphate (Sigma), 10−8 dexamethasone (Sigma) for osteoblastogenesis, 20 ng/mL TGF‐β3 (PeproTech), 200 mM ascorbic acid for chondrogenesis or Adipogenic Stimulatory Supplement (Stem Cell Technologies) for adipogenesis. Differentiation media was changed twice a week and cells were cultured up to 4 weeks. Immunofluorescence was performed using rabbit perilipin antibody (Sigma, 5 μg/mL), goat collagen II antibody (Santa Cruz, 1:250) or rabbit osterix antibody (Abcam, 1:600) and Alexa Fluor 350, 633 or 647 secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes, 1:400) and imaged using an inverted Eclipse Ti (Nikon) or LSM 700 laser scanning confocal (Zeiss) microscope. Nuclei were stained using 4′,6‐diamidino‐2‐phenylindole (DAPI) (Sigma, 1:1000).

2.3. Flow cytometry

BM cells were isolated from mTert‐GFP mice (n = 3). Hematopoietic cells and dead cells were excluded by staining with anti‐CD45‐APC (BD‐Pharmingen, 1:100) and propidium iodide (eBioscience, 1:500) as previously described. 25 Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry using either a MoFlo cytometer (Dako) or BD FACSAria.

2.4. Immunofluorescence

Isolated long bones were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, decalcified using 0.5 M EDTA in phospate buffered saline (PBS) then vibratome (100‐200 μm) or frozen (20‐25 μm) sectioned. Immunofluorescence was performed using chicken or rabbit GFP antibody (Abcam, 1:1000), rabbit osterix antibody (Abcam, 1:600), rat CD31 antibody (Pharmingen, 1:200), rat CD45 antibody (Pharmingen, 1:100), rabbit perilipin antibody (Sigma, 5 μg/mL), rabbit mTert antibody (Millipore, 1:150) or rabbit osteocalcin antibody (Abcam, 10 μg/mL) and Alexa Fluor 488, 594, 633, or 647 secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes, 1:400). LipidTOX Deep Red (ThermoFisher, 1:200) was used for lipid staining. Nuclei were stained using DAPI. Sections were imaged using either a 90i Eclipse (Nikon) or LSM 700 laser scanning confocal (Zeiss) microscope.

2.5. Quantitative Reverse Transcription PCR (qRT‐PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from long bones using TRI reagent (Sigma‐Aldrich) as per the manufacturer's protocol. cDNA was made using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcriptase kit (Applied Biosytems) and real time PCR was carried out using TaqMan PCR assays (Applied Biosystems). All the samples were run in triplicate and normalization was carried out using the 2ΔΔCT method relative to 18S or GAPDH as indicated in the figure legends.

2.6. Statistics

Two‐tailed Student's t test was used to compare groups of two‐ and one‐way analysis of variance was used for comparison of groups of three or more and differences among the means were evaluated using Tukey's post hoc test of contrast. Significance was set at P < .05 unless otherwise noted. *P < .05, **P ≤ .01, ***P < .001.

3. RESULTS

3.1. mTert expression in long bones is age‐dependent

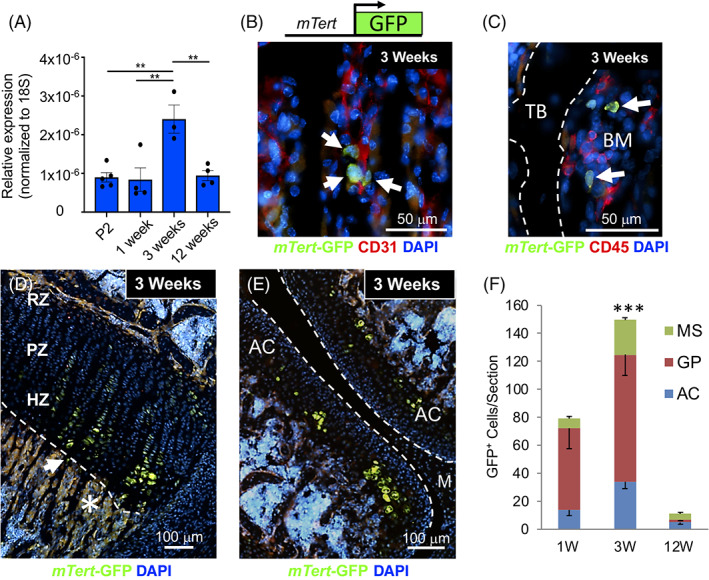

Recent studies indicate that discrete SSC populations function during the specific time periods that correspond to rapid bone growth and bone maintenance. 7 , 13 To investigate whether mTert is expressed during either of these time periods, we examined its expression in long bones at various ages by quantitative (q) RT‐PCR analysis (Figure 1A). Although mTert was detected at low levels during multiple time points, it was upregulated at the age of weaning (3‐4 weeks) suggesting that mTert + cells are temporally regulated and mark a discrete time period interposed between rapid bone growth and bone maintenance.

FIGURE 1.

mTert expression and localization in long bones. A, Quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT‐PCR) analysis of mTert expression in long bones at different postnatal ages. Data are presented as relative expression normalized to 18S. Dots represent individual samples. Three‐five mice were used per group. Mean ± SEM, **P < .01. B‐D, Localization of mTert‐GFP+ cells in 3‐week‐old long bones. GFP+ cells were identified adjacent to vascular (CD31+) cells in the metaphyseal stroma (B, arrows) and within the growth plate (C) and articular cartilage (D). E, Nonhematopoietic (CD45−) GFP+ cells were detected in the bone marrow (BM) near trabecular bone (TB). Representative merged images are shown. Asterisk and arrow in (D) demarcate autofluorescence and GFP+ cell, respectively. F, GFP+ cells in the articular cartilage, growth plate, and mesenchymal stroma of long bones were quantitated from 1‐, 3‐, and 12‐week‐old mTert‐GFP mice. Eight‐sixteen sections from 2 to 3 mice were analyzed at each time point. Bars represent total GFP+ cells per section. Mean ± SEM, ***P < .0001. The distribution of GFP+ cells within the metaphyseal stroma, growth plate, or articular cartilage is indicated within each bar. See also Figures S1 and S2. AC, articular cartilage; HZ, hypertrophic zone; M, meniscus; PZ, proliferative zone; RZ, resting zone

We next investigated the location of mTert‐expressing cells in 3‐week‐old long bones using our mTert‐GFP mouse model. 25 We have previously shown this reporter mouse line faithfully recapitulates endogenous telomerase activity in BM as well as the testis, heart and intestine. 25 , 26 , 36 mTert‐GFP+ cells were detected within the metaphyseal stroma (Figure 1B), with ~75% of 185 GFP+ cells analyzed residing adjacent to CD31+ vascular cells, consistent with the proposed location for SSCs. 1 In addition, a separate subpopulation of GFP+ CD45− BM cells were occasionally detected near the trabecular bone surface (Figure 1C), distinct from the previously described GFP+ CD45+ hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. 25 mTert‐GFP+ cells were also present within the hypertrophic zone of both the growth plate and articular cartilage and to a lesser extent in the resting and proliferative zones of the growth plate (Figure 1D,E), consistent with expression of endogenous mTert protein within the growth plate (Figure S1). Interestingly, mTert‐GFP+ cells were largely absent from the perichondrium, a site known to house SSCs during rapid bone growth. 8 , 13 Next, to investigate whether the increase in mTert expression at 3 weeks of age (Figure 1A) correlated with enhanced cell number, we quantified GFP+ cells within the articular cartilage, growth plate, and metaphyseal stroma of long bones at 1, 3, and 12 weeks of age (Figures 1F and S2). Consistent with our mTert gene expression data, the total number of GFP+ cells was highest at 3 weeks of age. In addition, at 1 and 3 weeks of age GFP+ cells were found within all three areas, with the majority present within the growth plate; in contrast, by 12 weeks of age the number of GFP+ cell was dramatically decreased, with few found in the growth plate. Similarly, endogenous mTert+ cells within the growth plate decreased at 12 weeks of age (Figure S1). Taken together, these data confirm that mTert expression, cell number, and distribution are temporally regulated in long bones.

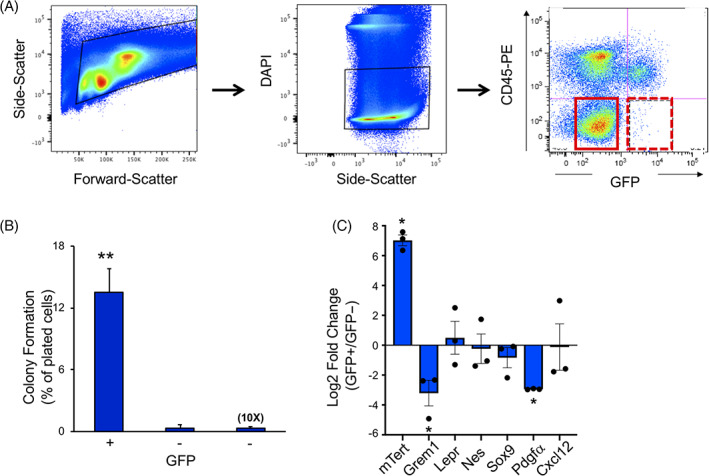

3.2. mTert marks a unique colony‐forming cell population

To investigate whether mTert + cells function as SSCs, we performed flow cytometric analysis on BM cells for GFP and CD45, which revealed a small population (<1%) of GFP+ CD45− cells (Figure 2A). To assess whether this population was enriched for SSCs, we isolated GFP+ CD45− cells by fluorescent activated cell sorting (FACS) and measured their capacity to form CFU‐Fs, a characteristic of SSCs. 37 Approximately 15% of FACS‐isolated GFP+ CD45− cells gave rise to colonies compared with only 0.5% of GFP− CD45− cells (Figure 2B). This colony formation rate of ~1 out of 6 cells is consistent with a previous report employing human SSCs. 5 As an additional control we analyzed 10 times the number of GFP− CD45− cells, which yielded a similarly low number of colonies (Figure 2B). These results demonstrate that mTert‐GFP+ cells exhibit a 30‐fold enrichment in their capacity to form CFU‐Fs compared with the main population of GFP negative cells and indicate that nearly all of the colony‐forming activity in the BM is found within the GFP+ cell population.

FIGURE 2.

Analysis of mTert‐GFP bone marrow cells. A, Representative fluorescent activated cell sorting (FACS) plot showing live GFP+ CD45− cells in hatched red box (arrow) and GFP− cells in solid red box. B, Percentage of colony formation of GFP+ and GFP− sorted cells. N = 3 mice. Mean ± SEM, **P < .005. C, Quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT‐PCR) analysis of SSC marker gene expression in mTert‐GFP+ cells. GAPDH was used as the internal control, data were analyzed using the 2−ddCt method and expressed as log 2‐fold change (GFP+/GFP−). Symbols represent individual samples. Cells were isolated from three mice. Mean ± SEM, *P < .05. SSC, skeletal stem cell

Given the temporal expression pattern of mTert + cells, we next assessed whether these cells represent a distinct SSC population. For this, we characterized the mTert + population with respect to other stem cell markers using flow cytometry and qRT‐PCR analyses of sorted mTert‐GFP+ and GFP− populations. Consistent with our findings in other tissues, 25 , 26 mTert expression was enriched in the GFP+ cells compared to GFP− cells (Figure 2C), further confirming that the GFP reporter faithfully marks endogenous mTert expression. We failed, however, to detect any enrichment in other known SSC markers which included Gremlin, Leptin receptor (LepR), Nestin, Sox9, PDGFRα as well as the perivascular stromal cell marker, Cxcl12. In fact, comparison between mTert‐GFP and the general SSC marker, PDGFRα, showed that mTert + cells represent less than 1% (0.48% ± 0.11%) of PDGFRα+ cells (145 of 31,660 PDGFRα+ cells analyzed, N = 3 mice). Furthermore, we found that mTert‐GFP+ cells do not coexpress the osteoprogenitor cell marker, Osterix (Osx) (0 of 144 GFP+ cells analyzed, N = 3 mice). Taken together, these data confirm that mTert expression marks a unique cell population at a distinct time period of bone growth.

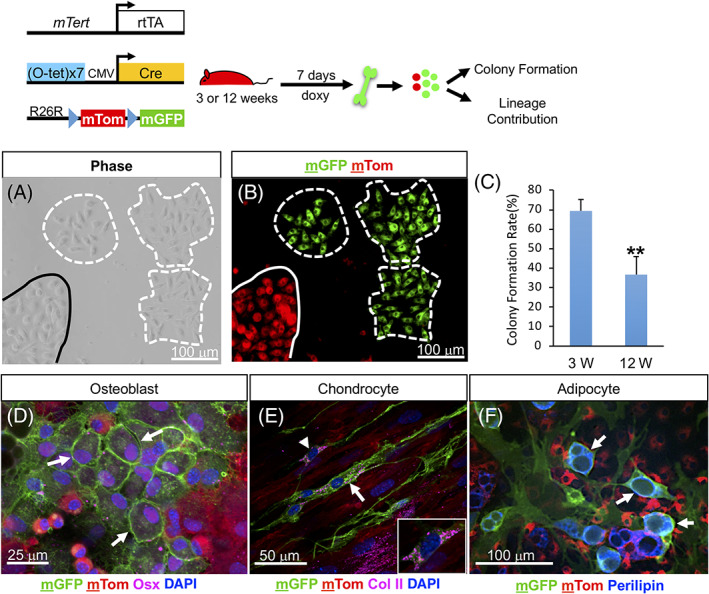

3.3. mTert expression marks multipotent progenitor/stem cells in vitro

To assess the functional capacity of mTert‐expressing cells, we generated a doxycycline‐inducible mouse model (mTert‐rtTA) (Figure S3A). These mice were subsequently crossed with otet‐Cre and R26R flox(mT/mG)/+ mice to generate mTert‐rtTA:: otet‐Cre:: R26R flox(mT/mG)/+ trigenic mice. We chose the mT/mG Cre‐reporter allele because of its high level of constitutive expression of membrane‐targeted Tomato (mTom) protein before Cre‐mediated recombination and membrane‐targeted GFP (mGFP) after recombination. 34 Analysis of long bones at 3 weeks of age, following a single injection of doxycycline, showed mGFP+ cells exhibit a distribution pattern similar to mTert‐GFP (Figure S3B, compare with Figure 1D). Doxycycline‐induced labeling was also dramatically decreased in 12‐week‐old mice (Figure S3C,E) consistent with mTert expression. No detectible doxycycline‐independent recombination was observed (Figure S3D).

To confirm the self‐renewal potential of mTert‐rtTA‐marked cells, and/or their progeny, we next assessed the capacity of lineage‐marked mGFP+ BM cells to give rise to CFU‐Fs. Similar to our findings with mTert‐GFP+ cells, approximately 70% of mGFP+ BM cells isolated from 3‐week‐old mice were able to form CFUs (Figures 3A‐C ). In contrast, mGFP+ BM cells from 12‐week‐old mice showed a marked decrease in the frequency (~35%) of lineage‐marked CFU‐Fs (Figure 3C), despite no difference in the overall number of mGFP+ BM cells at the time of isolation (Figure S3F). These results indicate a decline in the progenitor/stem cell activity of mGFP+ BM cells with age. Finally, in vitro differentiation assays demonstrated that mGFP+ cells contribute to multiple mesenchymal lineages, indicating mTert‐rtTA expression marks SSCs (Figure 3D‐F).

FIGURE 3.

In vitro analysis of mTert + cells. A,B, Colony formation of BM cells isolated from 3‐week‐old trigenic mice treated for 7 days. Dashed lines outline mGFP+ cell derived CFU‐Fs; solid line demarcates a non‐mTert derived colony. C, Percentage of single mGFP+ BM cells at 3 and 12 weeks of age that formed colonies. N = 5, 3. Mean ± SEM, **P = .01. D‐F, In vitro differentiation analysis of mGFP+ cells isolated from 3‐week‐old trigenic mice treated for 7 days. Arrows indicate differentiated mGFP+ cells. The treatment schematic is shown above. See also Figure S3. BM, bone marrow; CFU‐F, colony‐forming unit‐fibroblast

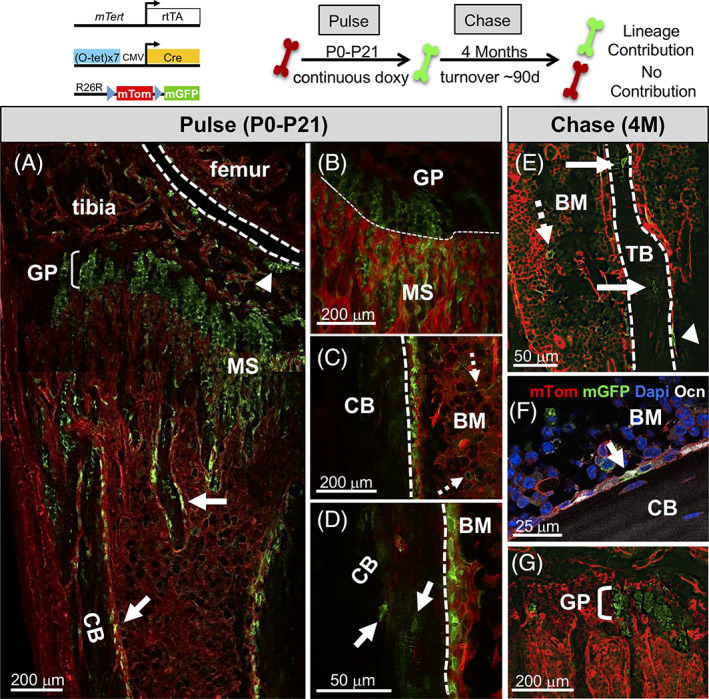

3.4. mTert expression marks osteochondroprogenitor cells in vivo

To establish the functional potential of the mTert + SSC cell population in vivo, lineage‐tracing analysis with trigenic mice was performed using a “pulse‐chase” paradigm (Figure 4). Analysis of long bones following an extended pulse of doxycycline revealed mGFP+ cells were present within the metaphyseal stroma (Figure 4A,B), BM (Figure 4C, dashed arrows), articular cartilage and growth plate (Figure 4A, arrowhead and bracket, respectively), consistent with our analysis of mTert‐GFP mice (Figures 1B‐E and S1). A similar pattern of mGFP+ cell distribution was observed following shorter treatment with doxycycline (Figure S4A). In addition, consistent with SSCs contributing to Osx+ osteoprogenitor cells, 13 we detected mGFP+ Osx+ cells following doxycycline administration (Figure S4G), indicating that mTert‐expressing cells can contribute to Osx+ cells. Furthermore, the presence of co‐positive cells within 24 hours is likely due to the rapid transit of chondrocytes through the growth plate as has been previously shown, 11 although it is possible that the two mouse models do not mark identical cell populations.

FIGURE 4.

mTert expression marks osteochondral progenitor cells in vivo. A‐D, Marked cells following an extended pulse of doxycycline. A composite image is shown (A). Arrows indicate mGFP+ cells lining trabecular and cortical bone (A). Marked metaphyseal stromal (A, B), bone marrow cells (C, dashed arrows) and osteocytes (D, arrows) are shown. Dashed lines demarcate the joint (A), growth plate (B), and cortical bone (C, D). Arrowhead (A) demarcates the articular cartilage. E‐G, Marked cells after an extended chase (4 months). mGFP+ cells lining trabecular (E, arrowhead) and cortical bone (F, arrow), in the BM (E, dashed arrow) and within the growth plate (G, bracket). Solid arrows in (E) indicate marked osteocytes. Ocn+ mGFP+ cell in (F) confirmed contribution to the osteoblast lineage. The treatment schematic is shown above. See also Figure S4. BM, bone marrow; CB, cortical bone; GP, growth plate; MS, metaphyseal stroma; TB, trabecular bone

The presence of Osx+ marked cells dramatically declined at 12 weeks suggesting a functional decline in mTert+ SSCs with age. In addition to increased osteoprogenitor cell marking, we also observed an increase in mGFP+ cells along both trabecular and cortical bone (Figure 4A, arrows), likely due to the extended pulse time as few cells were noted at these locations following exposure to doxycycline for shorter time periods (Figures S3B and S4A).

To assess the long‐term persistence and self‐renewal capacity of mTert‐rtTA marked cells, trigenic mice pulsed with doxycycline were chased for up to 4 months. The analysis revealed lineage‐marked cells lining the surfaces of both trabecular (Figure 4E, arrowhead) and cortical bone (Figure 4F, arrow denotes an osteocalcin [Ocn] + osteoblast) as well as osteocytes (Figure 4E, arrow). In addition, marked cells were still present within the growth plate (Figure 4G) demonstrating long‐term lineage contribution of mTert‐expressing cells to both bone and cartilage. These results are consistent with the hypertrophic chondrocyte's continual commitment to the osteogenic fate into adulthood. Given bone turnover occurs within ~90 days, 20 the presence of lineage‐marked cells after an extended period of chase demonstrates the self‐renewal potential and long‐term persistence of the mTert‐expressing cells. Consistent with mTert expression marking a subpopulation of HSCs, lineage‐marked cells were also observed in the BM (Figure 4E, dashed arrow). Similar findings were observed when mice were pulsed with doxycycline for a shorter period (Figure S4B‐F). Taken together, these data argue that mTert expression marks osteochondral progenitor cells in long bones.

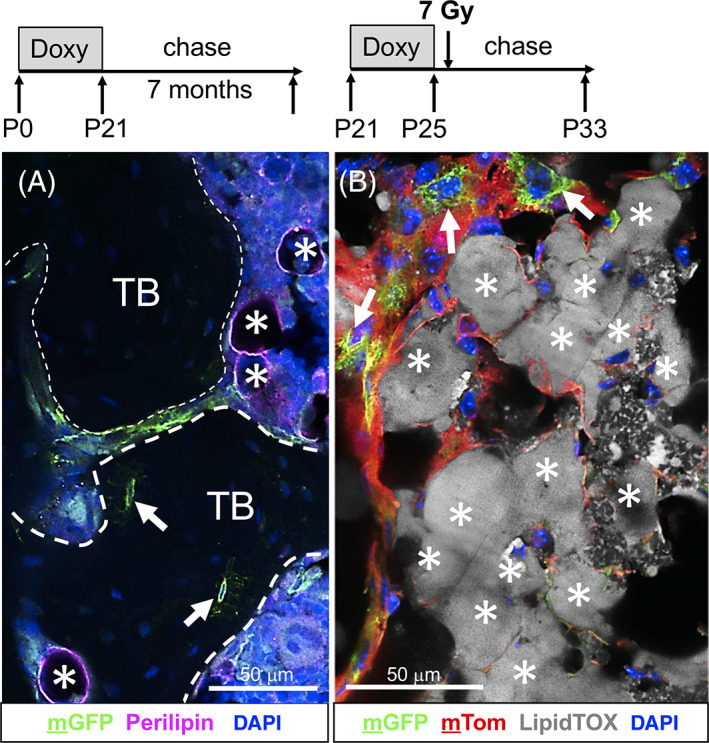

In contrast to the in vitro lineage analysis, we did not observe contribution of mTert‐expressing cells to the adipogenic lineage in these mice, as no colabeling of mGFP and perilipin+ adipocytes were detected even following a 7‐month chase (Figure 5A). To further confirm that mTert‐rtTA cells fail to contribute to the adipocyte lineage in vivo, we induced BM adipogenesis in 3‐week‐old trigenic mice using whole‐body irradiation, a known stimulus for marrow‐derived adipogenesis. Analysis of 624 LipidTOX‐stained adipocytes from three trigenic mice failed to detect colabeling with lineage‐marked mGFP+ cells (Figure 5B). Together, these data indicate that mTert + cells lack the capacity to contribute to adipocytes in vivo, consistent with a recent report that metaphyseal progenitor/stem cells are unable to differentiate into adipocytes. 8

FIGURE 5.

mTert‐rtTA marked cells do not contribute to the adipocyte lineage. A, Immunofluorescent analysis of the adipocytic marker, perilipin, following extended chase. Dashed lines outline trabecular bone; asterisks, perilipin+ adipocytes; arrows, mGFP+ osteocytes. Representative confocal image is shown. Treatment schematic is shown above. Briefly, trigenic (mTert‐rtTA:: otet‐Cre:: R26R flox(mT/mG)/+) mice were treated with doxycycline for 3 weeks from birth (P0‐P21) and then chased for 7 months at which time long bones were isolated and analyzed for lineage contribution. TB, trabecular bone. B, LipidTOX Deep Red staining of adipocytes in long bone sections following irradiation. Arrows demarcate nonadipocyte mGFP+ cells. Asterisks demarcate LipidTOX+ cells. A composite confocal image is shown. Treatment schematic is shown above. Briefly, trigenic (mTert‐rtTA:: otet‐Cre:: R26R flox(mT/mG)/+) mice were treated with doxycycline for 4 days and irradiated 24 hours later. Long bones were collected 7 days after irradiation. Scale bars = 50 μm

4. DISCUSSION

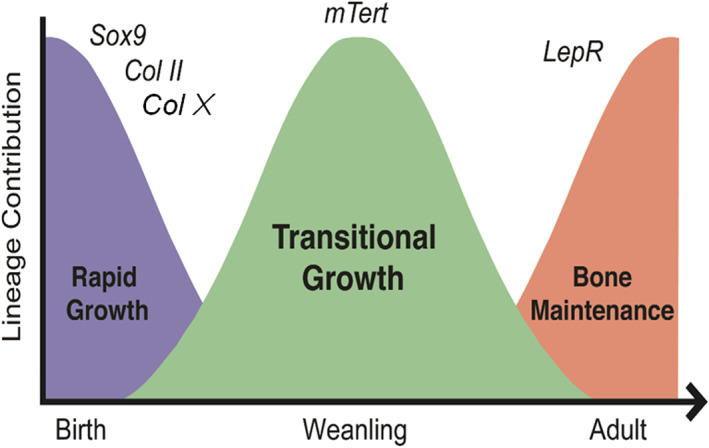

In summary, we have identified a population of osteochondral progenitor/stem cells, marked by mTert expression, that function during adolescent bone formation between the periods of rapid perinatal bone growth and adult bone maintenance (Figure 6). Our data are consistent with recent findings that bone formation is temporally controlled by discrete populations of SSCs. Our findings are unique in that mTert‐expressing SSCs are distinct and function at a later stage in postnatal bone growth than do cells marked by either Collagen II, Collagen X, or Sox9 but prior to cells marked by LepR. We have designated this time period as the phase of “transitional growth” and propose that it corresponds to the adolescent growth spurt in humans, since patients with defects in telomere length and stability fail to undergo this event. 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 Although our lineage‐tracing data demonstrate the functional capacity of mTert + SSCs, these studies are limited and additional analysis using transplantation assays would further enhance the significance of their role during transitional growth.

FIGURE 6.

mTert expression marks a distinct phase of transitional bone growth. Schematic model illustrating the presence of a period of bone growth designated as transitional growth separate from rapid growth and bone maintenance

4.1. mTert expressing cells are unique and function at a distinct time period

Over the last few years, multiple laboratories have identified SSCs in a variety of locations within long bones. While our findings show that mTert‐expressing cells mark regions known to house SSCs, their lack of enrichment in any of the other SSC markers indicates that these cells may constitute a unique SSC population, although it is also possible that the lack of SSC marker enrichment we observe in these cells is due to mTert expression marking multiple SSC populations or a subset of them. Additional coexpression studies are warranted in order to fully determine the distinct nature of mTert + cells. It is clear, however, that mTert‐expressing cells likely do not mark LepR+ SSCs based on the fact that mTert expression and cell number dramatically decline in adult bone (>12 weeks), the lack of enrichment in LepR+ cell comarkers, CXCL12 and PDGFRα as well as their inability to give rise to adipocytes, key characteristics of the LepR+ cells. 7

Exactly what factors regulate mTert expression during adolescent bone growth is not clear. Prior studies have shown that a variety of endocrine signals including growth hormone (GH), thyroid hormone, and sex steroids act on the growth plate to regulate bone growth, 42 and it is possible these factors play a role. In fact, GH has been shown to regulate mTert transcription both directly and indirectly, 43 , 44 and it is tempting to speculate that the increase in mTert expression during bone growth is mediated, in part, by GH. Alternatively, estrogen, a key regulator of the pubertal growth spurt, may also play a role in regulating mTert expression as it has been shown to transcriptionally upregulate hTERT in human cells. 45 Conversely, estrogen may mediate the decrease in mTert+ cell number at 12 weeks of age given previous findings that it accelerates growth plate senescence via depletion of growth plate progenitor cells. 42 It has also been reported that thyroid hormone enhances fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 expression which, in turn, negatively regulates Tert expression, telomerase activity, and bone elongation. 46 Based on these prior studies, it will be important to carefully define which factors are responsible for regulating the temporal expression pattern of mTert + cells in long bones.

Furthermore, given that multiple cell populations within long bones express mTert, it is difficult to identify which of these mTert + cell subpopulations contribute to bone formation. Going forward it will be important to identify unique markers that will allow us to study each subpopulation independently. How mTert + cells vary from other SSC populations that function during this time also remains unclear. A more complete understanding of the relationship between these various SSC populations is necessary in order to fully decipher their role in bone biology as well as their potential use in the treatment of bone disease.

4.2. Stem cell hierarchy in long bones

Whether SSCs function at defined time periods during the lifetime of the skeleton or contribute to other populations resident in skeletal tissues remains unknown and is of high importance in the field. Our data, in combination with other reports, indicate that there are waves of stem cell activity in long bones. Exactly how many waves of SSCs exist within long bones, what controls their timing and functional lineage capacity, and their role in response to injury remains to be determined. It has been proposed that a hierarchical relationship exists between the different SSC populations. That is, SSCs present during embryonic or early postnatal life may be the precursors to those required for adult bone maintenance. To this end, lineage‐tracing studies in which Collagen II‐derived cells were detected well into adulthood 13 have led many to propose that LepR+ SSCs arise from cells present in embryos and young mice. However, definitive proof for this hypothesis is lacking. Given the heterogeneity of progenitor/stem cells within the BM, it is not likely that all bone cells arise from a common progenitor population. Therefore, going forward, it will be imperative to define the inter‐relationship of the various SSC populations.

4.3. Role of telomerase in chondrogenic cells

In humans, telomerase has been shown to predominantly mark hypertrophic chondrocytes within the growth plate and is required for endochondral bone growth. 47 In addition, telomerase activity declines with age, suggesting a possible role in growth plate closure. Our findings are consistent with this idea, as indicated by the presence of endogenous mTert protein and mTert‐GFP expression within murine hypertrophic chondrocytes, which declined with age. Of note, while immunohistochemical analysis suggests that mTert is expressed in all hypertrophic chondrocytes, mTert‐GFP was detected in fewer cells possibly suggesting (a) an artificially lower frequency of mTert+ cells or (b) discordance between mTert‐induced GFP and mTert protein stability. This difference is likely not due to the inefficiency of the mTert‐GFP mouse model given our prior findings 25 , 26 and Figure 2C. Going forward it will be important to determine the percentage of mTert+ hypertrophic chondrocytes and to determine what role telomerase plays in hypertrophic chondrocytes. This is especially important given hypertrophic chondrocytes can give rise to osteoblasts, either directly or via an intermediate progenitor/stem cell, during rapid bone growth and following injury, 10 , 11 , 12 raising the intriguing possibility that a subset of hypertrophic cells may represent SSCs. The presence of mTert+ cells, albeit to a lesser extent, within the resting and proliferative zones of the growth plate suggest an additional role for telomerase in cartilage biology. Whether these cells function as cartilage stem cells is unknown, although the presence of mTert‐marked cells in the resting zone, a region recently shown to house stem cells, 14 suggests this may be the case. Alternatively, mTert expression within the proliferative zone may function in sustaining chondrocyte proliferation as downregulation of human TERT has been linked with inhibition of chondrocyte proliferation. 47 Going forward it will be important to decipher the role of mTert and/or telomerase activity in the different regions of the growth plate. Finally, our data also show that mTert+ cells are present within the articular cartilage, which also has been shown to contain progenitor/stem cells. 48 Whether mTert expression marks these cells remains to be determined but prior studies have shown that articular progenitor/stem cells exhibit higher telomere length and telomerase activity 49 warranting further examination.

5. CONCLUSION

Our study has identified a distinct population of osteochondral progenitor cells, marked by mTert expression that function during a defined temporal period of bone growth. Future studies focused on understanding if alterations in this cell population during this growth period translate into disorders of linear growth or bone homeostasis (such as osteoporosis) are warranted. In addition, understanding what role physiological factors play in regulating both the temporal pattern of mTert + SSCs and their influence on the ability of these cells to participate in bone formation will be important. Given that the adolescence growth spurt represents the period of greatest bone mass accrual, understanding the requirement of SSCs during this period of transitional growth has important implications for understanding skeletal homeostasis.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

D.L.C., D.T.B.: supervision of research, study design, performed experiments, manuscript preparation; R.D.R‐W.: study design, performed experiments; L.T.D., A.T., L.J., D.M.A., B.E.M., M.S.S.: technical assistance with experiments; C.J.L.: study design, performed experiments; R.J.: supervision of research.

Supporting information

Supplementary Figure 1 Growth plate expression of mTert in long bones.

Representative immunostaining for mTert+ cells in the long bones at 3 and 12 weeks of age. Arrows demarcate mTert+ hypertrophic chondrocytes present at 3 weeks but absent at 12 weeks. Insets, enlarged image of growth plate demonstrating the presence of mTert‐expressing cells at 3 weeks but not at 12 weeks. No detectible signal was observed in 3 week old long bones lacking the primary antibody (−Ab). Dashed line demarcates the boundry between the growth plate (GP) and the metaphyseal stroma (MS). Scale bar, 50 μm

Supplementary Figure 2 Temporal expression of mTert‐GFP + cells in long bones.

(A‐F) Representative immunofluorescent images for GFP+ cells in the long bones at 1 week (A,B), 3 weeks (C,D) and 12 weeks (E,F) of age. (B) is a higher magnification of dashed box in (A). Arrows (D) demarcate GFP+ metaphyseal stromal cells; arrowheads (C,E) indicate labeled cells in the AC. Inset in (E), enlarged image of GFP+ cells in AC, demarcated by arrowhead. AC, articular cartilage; GP, growth plate; MS, metaphyseal stroma; BM, bone marrow. Scale bars, 100 μm

Supplementary Figure 3 Doxycycline‐inducible mTert mouse model.

(A) Representative fluorescent and phase images of ES cells demonstrating the doxycycline‐inducible and reversible mTert‐rtTA construct. (B,C) Representative images of long bones from 3 week old (B) or 12 week old (C) trigenic (mTert‐rtTA:: otet‐Cre:: R26R flox(mT/mG)/+) mice 24 h after a single injection of doxycycline. mGFP+ cells are present within the growth plate and in the metaphyseal stroma (arrow) following doxycycline administration. No doxycycline control 3 week old is shown in (D). (E) mGFP+ cells per section at 3 weeks and 12 weeks of age following a single injection of doxycycline. N = 2,2. (F) The number of adherent mGFP+ BM cells isolated from 3 and 12 week old trigenic (mTert‐rtTA:: otet‐Cre:: R26R flox(mT/mG)/+) mice following a week of doxycycline administration. N = 5, 3. For bars, mean ± SEM is shown, n.s. = not significant, *P < 0.05. GP, growth plate

Supplementary Figure 4 mTert expression marks osteochondral progenitor cells following a short pulse

(A) Marked cells following 5 day pulse of doxycycline. mGFP+ cells were observed in the articular cartilage, growth plate and the metaphyseal stroma. (B‐F) Marked cells after an extended chase (4 months). mGFP+ cells were detected lining trabecular bone (B‐D, arrows), in the BM stroma (C, arrowheads) and the growth plate (B, E). Dashed lines demarcate the growth plate. Dashed arrows indicate marked osteocytes within trabecular (D) and cortical bone (F). The treatment schematic is shown above. AC, articular cartilage; GP, growth plate; MS, metaphyseal stroma; SOC, secondary site of ossification; TB, trabecular bone; CB, cortical bone; BM, bone marrow. Scale bars, 100 μm (A,B), 10 μm (C‐F) (G) Percentage of Osterix (Osx)+ mGFP+ cells within the metaphyseal stroma of long bones following doxycycline treatment at 3 and 12 weeks (W) of age. N = 2, 2. Bars shown are mean ± SEM *P < 0.05

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank members of the Breault lab and Dr Vicki Rosen for input on the manuscript. This work was supported by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research R21DE022420 and the National Institute on Aging R03AG054723 awarded to D.L.C. and the IDDRC P30HD18655 and the Timothy Murphy Fund.

Carlone DL, Riba‐Wolman RD, Deary LT, et al. Telomerase expression marks transitional growth‐associated skeletal progenitor/stem cells. Stem Cells. 2021;39:296–305. 10.1002/stem.3318

Funding information IDDRC, Grant/Award Number: P30HD18655; National Institute on Aging, Grant/Award Number: R03AG054723; National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, Grant/Award Number: R21DE022420; Timothy Murphy Fund

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bianco P, Robey PG. Skeletal stem cells. Development. 2015;142(6):1023‐1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Serowoky MA, Arata CE, Crump JG, Mariani FV. Skeletal stem cells: insights into maintaining and regenerating the skeleton. Development. 2020;147(5):dev179325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Matsushita Y, Ono W, Ono N. Skeletal stem cells for bone development and repair: diversity matters. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2020;18:189‐198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Owen M, Friedenstein AJ. Stromal stem cells: marrow‐derived osteogenic precursors. Ciba Found Symp. 1988;136:42‐60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sacchetti B, Funari A, Michienzi S, et al. Self‐renewing osteoprogenitors in bone marrow sinusoids can organize a hematopoietic microenvironment. Cell. 2007;131(2):324‐336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mendez‐Ferrer S, Michurina TV, Ferraro F, et al. Mesenchymal and haematopoietic stem cells form a unique bone marrow niche. Nature. 2010;466(7308):829‐834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhou BO, Yue R, Murphy MM, Peyer JG, Morrison SJ. Leptin‐receptor‐expressing mesenchymal stromal cells represent the main source of bone formed by adult bone marrow. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15(2):154‐168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Worthley DL, Churchill M, Compton JT, et al. Gremlin 1 identifies a skeletal stem cell with bone, cartilage, and reticular stromal potential. Cell. 2015;160(1‐2):269‐284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Matic I, Matthews BG, Wang X, et al. Quiescent bone lining cells are a major source of osteoblasts during adulthood. Stem Cells. 2016;34(12):2930‐2942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhou X, von der Mark K, Henry S, Norton W, Adams H, de Crombrugghe B. Chondrocytes transdifferentiate into osteoblasts in endochondral bone during development, postnatal growth and fracture healing in mice. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(12):e1004820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yang L, Tsang KY, Tang HC, Chan D, Cheah KSE. Hypertrophic chondrocytes can become osteoblasts and osteocytes in endochondral bone formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(33):12097‐12102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yang G, Zhu L, Hou N, et al. Osteogenic fate of hypertrophic chondrocytes. Cell Res. 2014;24(10):1266‐1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ono N, Ono W, Nagasawa T, Kronenberg HM. A subset of chondrogenic cells provides early mesenchymal progenitors in growing bones. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16(12):1157‐1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mizuhashi K, Ono W, Matsushita Y, et al. Resting zone of the growth plate houses a unique class of skeletal stem cells. Nature. 2018;563(7730):254‐258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bianco P. "Mesenchymal" stem cells. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2014;30:677‐704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bianco P, Cao X, Frenette PS, et al. The meaning, the sense and the significance: translating the science of mesenchymal stem cells into medicine. Nat Med. 2013;19(1):35‐42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chan CK et al. Identification and specification of the mouse skeletal stem cell. Cell. 2015;160(1‐2):285‐298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Morikawa S, Mabuchi Y, Kubota Y, et al. Prospective identification, isolation, and systemic transplantation of multipotent mesenchymal stem cells in murine bone marrow. J Exp Med. 2009;206(11):2483‐2496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mizoguchi T, Pinho S, Ahmed J, et al. Osterix marks distinct waves of primitive and definitive stromal progenitors during bone marrow development. Dev Cell. 2014;29(3):340‐349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Park D, Spencer JA, Koh BI, et al. Endogenous bone marrow MSCs are dynamic, fate‐restricted participants in bone maintenance and regeneration. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10(3):259‐272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Roake CM, Artandi SE. Regulation of human telomerase in homeostasis and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2020;21(7):384‐397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lee HW, Blasco MA, Gottlieb GJ, Horner JW II, Greider CW, DePinho RA. Essential role of mouse telomerase in highly proliferative organs. Nature. 1998;392(6676):569‐574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Serakinci N, Graakjaer J, Kolvraa S. Telomere stability and telomerase in mesenchymal stem cells. Biochimie. 2008;90(1):33‐40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stadtfeld M, Maherali N, Breault DT, Hochedlinger K. Defining molecular cornerstones during fibroblast to iPS cell reprogramming in mouse. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2(3):230‐240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Breault DT, Min IM, Carlone DL, et al. Generation of mTert‐GFP mice as a model to identify and study tissue progenitor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(30):10420‐10425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Montgomery RK, Carlone DL, Richmond CA, et al. Mouse telomerase reverse transcriptase (mTert) expression marks slowly cycling intestinal stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(1):179‐184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Liu L, DiGirolamo CM, Navarro PAAS, Blasco MA, Keefe DL. Telomerase deficiency impairs differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. Exp Cell Res. 2004;294(1):1‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pignolo RJ, Suda RK, McMillan EA, et al. Defects in telomere maintenance molecules impair osteoblast differentiation and promote osteoporosis. Aging Cell. 2008;7(1):23‐31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shi S, Gronthos S, Chen S, et al. Bone formation by human postnatal bone marrow stromal stem cells is enhanced by telomerase expression. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20(6):587‐591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Simonsen JL, Rosada C, Serakinci N, et al. Telomerase expression extends the proliferative life‐span and maintains the osteogenic potential of human bone marrow stromal cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20(6):592‐596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Armstrong L, Lako M, Lincoln J, Cairns PM, Hole N. mTert expression correlates with telomerase activity during the differentiation of murine embryonic stem cells. Mech Dev. 2000;97(1‐2):109‐116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Beard C, Hochedlinger K, Plath K, Wutz A, Jaenisch R. Efficient method to generate single‐copy transgenic mice by site‐specific integration in embryonic stem cells. Genesis. 2006;44(1):23‐28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Perl AK, Wert SE, Nagy A, Lobe CG, Whitsett JA. Early restriction of peripheral and proximal cell lineages during formation of the lung. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(16):10482‐10487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Muzumdar MD, Tasic B, Miyamichi K, Li L, Luo L. A global double‐fluorescent Cre reporter mouse. Genesis. 2007;45(9):593‐605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dobson KR, Reading L, Haberey M, Marine X, Scutt A. Centrifugal isolation of bone marrow from bone: an improved method for the recovery and quantitation of bone marrow osteoprogenitor cells from rat tibiae and femurae. Calcif Tissue Int. 1999;65(5):411‐413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Richardson GD, Breault D, Horrocks G, Cormack S, Hole N, Owens WA. Telomerase expression in the mammalian heart. FASEB J. 2012;26(12):4832‐4840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bianco P et al. Postnatal skeletal stem cells. Methods Enzymol. 2006;419:117‐148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chen L, Oshima J. Werner syndrome. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2002;2(2):46‐54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chang S, Multani AS, Cabrera NG, et al. Essential role of limiting telomeres in the pathogenesis of Werner syndrome. Nat Genet. 2004;36(8):877‐882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cheung HH, Liu X, Canterel‐Thouennon L, Li L, Edmonson C, Rennert OM. Telomerase protects werner syndrome lineage‐specific stem cells from premature aging. Stem Cell Reports. 2014;2(4):534‐546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Blasco MA. Telomere length, stem cells and aging. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3(10):640‐649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lui JC, Garrison P, Baron J. Regulation of body growth. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2015;27(4):502‐510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gomez‐Garcia L, Sánchez FM, Vallejo‐Cremades MT, de Segura IAG, del Campo EDM. Direct activation of telomerase by GH via phosphatidylinositol 3′‐kinase. J Endocrinol. 2005;185(3):421‐428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Emerald BS, Chen Y, Zhu T, et al. AlphaCP1 mediates stabilization of hTERT mRNA by autocrine human growth hormone. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(1):680‐690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cong YS, Wright WE, Shay JW. Human telomerase and its regulation. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2002;66(3):407‐425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Smith LB, Belanger JM, Oberbauer AM. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 effects on proliferation and telomerase activity in sheep growth plate chondrocytes. J Anim Sci Biotechnol. 2012;3(1):39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Morita M, Nakanishi K, Kawai T, Fujikawa K. Telomere length, telomerase activity, and expression of human telomerase reverse transcriptase mRNA in growth plate of epiphyseal articular cartilage in femoral head during normal human development and in thanatophoric dysplasia. Hum Pathol. 2004;35(4):403‐411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jiang Y, Tuan RS. Origin and function of cartilage stem/progenitor cells in osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2015;11(4):206‐212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Williams R, Khan IM, Richardson K, et al. Identification and clonal characterisation of a progenitor cell sub‐population in normal human articular cartilage. PLoS One. 2010;5(10):e13246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1 Growth plate expression of mTert in long bones.

Representative immunostaining for mTert+ cells in the long bones at 3 and 12 weeks of age. Arrows demarcate mTert+ hypertrophic chondrocytes present at 3 weeks but absent at 12 weeks. Insets, enlarged image of growth plate demonstrating the presence of mTert‐expressing cells at 3 weeks but not at 12 weeks. No detectible signal was observed in 3 week old long bones lacking the primary antibody (−Ab). Dashed line demarcates the boundry between the growth plate (GP) and the metaphyseal stroma (MS). Scale bar, 50 μm

Supplementary Figure 2 Temporal expression of mTert‐GFP + cells in long bones.

(A‐F) Representative immunofluorescent images for GFP+ cells in the long bones at 1 week (A,B), 3 weeks (C,D) and 12 weeks (E,F) of age. (B) is a higher magnification of dashed box in (A). Arrows (D) demarcate GFP+ metaphyseal stromal cells; arrowheads (C,E) indicate labeled cells in the AC. Inset in (E), enlarged image of GFP+ cells in AC, demarcated by arrowhead. AC, articular cartilage; GP, growth plate; MS, metaphyseal stroma; BM, bone marrow. Scale bars, 100 μm

Supplementary Figure 3 Doxycycline‐inducible mTert mouse model.

(A) Representative fluorescent and phase images of ES cells demonstrating the doxycycline‐inducible and reversible mTert‐rtTA construct. (B,C) Representative images of long bones from 3 week old (B) or 12 week old (C) trigenic (mTert‐rtTA:: otet‐Cre:: R26R flox(mT/mG)/+) mice 24 h after a single injection of doxycycline. mGFP+ cells are present within the growth plate and in the metaphyseal stroma (arrow) following doxycycline administration. No doxycycline control 3 week old is shown in (D). (E) mGFP+ cells per section at 3 weeks and 12 weeks of age following a single injection of doxycycline. N = 2,2. (F) The number of adherent mGFP+ BM cells isolated from 3 and 12 week old trigenic (mTert‐rtTA:: otet‐Cre:: R26R flox(mT/mG)/+) mice following a week of doxycycline administration. N = 5, 3. For bars, mean ± SEM is shown, n.s. = not significant, *P < 0.05. GP, growth plate

Supplementary Figure 4 mTert expression marks osteochondral progenitor cells following a short pulse

(A) Marked cells following 5 day pulse of doxycycline. mGFP+ cells were observed in the articular cartilage, growth plate and the metaphyseal stroma. (B‐F) Marked cells after an extended chase (4 months). mGFP+ cells were detected lining trabecular bone (B‐D, arrows), in the BM stroma (C, arrowheads) and the growth plate (B, E). Dashed lines demarcate the growth plate. Dashed arrows indicate marked osteocytes within trabecular (D) and cortical bone (F). The treatment schematic is shown above. AC, articular cartilage; GP, growth plate; MS, metaphyseal stroma; SOC, secondary site of ossification; TB, trabecular bone; CB, cortical bone; BM, bone marrow. Scale bars, 100 μm (A,B), 10 μm (C‐F) (G) Percentage of Osterix (Osx)+ mGFP+ cells within the metaphyseal stroma of long bones following doxycycline treatment at 3 and 12 weeks (W) of age. N = 2, 2. Bars shown are mean ± SEM *P < 0.05

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.