Abstract

Reduction of (CAAC)BBr2(NCS) (CAAC=cyclic alkyl(amino)carbene) in the presence of a Lewis base L yields tricoordinate (CAAC)LB(NCS) borylenes which undergo reversible E/Z‐isomerization. The same reduction in the absence of L yields deep blue, bis(CAAC)‐stabilized, boron‐doped, aromatic thiazolothiazoles resulting from the dimerization of dicoordinate (CAAC)B(NCS) borylene intermediates.

Keywords: aromaticity, borylenes, DFT, fused thiazaboroles, reduction

While the reduction of cyclic alkyl(amino)carbene‐stabilized isothiocyanatoboranes in the presence of a Lewis base yields tricoordinate isothiocyanatoborylenes, the reduction in the absence of a Lewis base yields the first examples of deep blue, boron‐doped, aromatic thiazolothiazoles.

Conjugated molecules and materials based on fused thiazolo[5,4‐d]thiazole (TzTz) building blocks have attracted much interest in the past decade because of their interesting optoelectronic properties and high thermal stability. [1] Theoretical studies have shown that the introduction of aromatic TzTz spacers into conjugated oligo‐ and polymers often enhances their π‐stacking ability and light‐harvesting efficiency, improves charge injection and transport, hinders charge recombination and increases dye regeneration. [2] These properties make TzTz‐based materials particularly suitable for applications in organic photovoltaic cells (OPVs), organic light‐emitting diodes (OLEDs), and organic field‐effect transistors (OFETs). [3] Furthermore, TzTz‐based luminescent materials and small molecules have been developed for chemical sensing, [4] photocatalysis, [5] live cell imaging, [6] and NIR‐II photothermal conversion and therapy. [7]

Studies have shown that the replacement of an endocyclic carbon unit [CR] (R=anionic substituent) by an isolobal boron unit [BR] in heteroaromatic molecules results in unique electronic properties owing to the strong electrophilic character of boron. [8] This enables new applications of boron‐heteroarenes in coordination chemistry, pharmacology, and materials science. While B,N‐heteroarenes have been intensively studied, [8] and there is an increasing interest in B,S‐heteroarenes owing to their potential use in electronic devices, [9] examples of B,N,S‐heteroarenes remain essentially limited to the stable 1,3,2‐benzothiazaborole motif, which is easily accessed through the reaction of borane precursors with o‐aminothiophenols [10] or benzothiazole derivatives. [11] In contrast, monocyclic thiazaboroles (Tzb) have only been studied theoretically, [12] in particular with regard to their potential as superhalogens, that is, aromatic molecules with an electron affinity higher than that of chlorine. [13] Consequently, studies on the applications of Tzb derivatives remain rare. Benzothiazaborolyl ligands have been used in transition metal chemistry [14] while benzothiazaborolates have been tested for their biocidal properties. [15] The successful use of oligomers containing aromatic benzo‐bis([1,3,2]Tzb) units in OFETs [16] also highlights the potential of fused Tzb building blocks in optoelectronic devices.

Herein, we report a straightforward synthetic route towards hitherto unknown fused [1,3,2]thiazaborolo[5,4‐d][1,3,2]thiazaboroles (TzbTzb) through the reductive dimerization and C−C coupling of transient isothiocyanatoborylenes of the form [LB(NCS)] (L=neutral donor ligand). Spectroscopic and computational studies highlight the differences and similarities with the parent TzTz unit.

Inspired by our previous study on the reduction of a cyclic alkyl(amino)carbene (CAAC)‐stabilized cyanoborane to a self‐stabilizing, tetrameric cyanoborylene, [(CAAC)B(CN)]4, which features a 12‐membered (BCN)4 ring, [17] we wondered if the reduction of a related (CAAC)‐stabilized boron isothiocyanate would yield a similar oligomeric, self‐stabilizing [(CAAC)B(NCS)]n species. To verify the viability of (CAACR)B(NCS) borylenes, their tricoordinate adducts with the N‐heterocyclic carbene (NHC) IiPr (1,3‐diisopropylimidazol‐2‐ylidene) were first synthesized by room temperature reduction of the (CAACR)BBr2(NCS) precursors (CAACMe=1‐(2,6‐diisopropylphenyl)‐3,3,5,5‐tetramethyl‐pyrrolidin‐2‐ylidene; CAACCy=2‐(2,6‐diisopropylphenyl)‐3,3‐dimethyl‐2‐azaspiro[4.5]decan‐1‐ylidene), 1Me and 1Cy, [18] with 2.2 equiv KC8 in benzene (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis and isomerization of CAAC–NHC‐stabilized (E)‐ and (Z)‐isothiocyanatoborylenes. Dip=2,6‐diisopropylphenyl.

After workup, fractional crystallization of each borylene from benzene afforded two consecutive crops of orange crystals, each showing a different 11B NMR resonance, the first at −2.6 ppm, the second at 3.8 ppm. In each case X‐ray crystallographic analyses identified the first crop (62–68 % yield of isolated product) as the (Z) isomer of the unsymmetrical isothiocyanatoborylene, (Z)‐2R, in which N1 and N4 are positioned on the same side of the C2=B3 double bond, and the second crop (ca. 10 % yield of isolated product) as the corresponding (E)‐2R isomer (see Figure 1 for (Z)‐2Me and (E)‐2Cy, and Figures S55 and S56 in the SI for molecular structures of (E)‐2Me and (Z)‐2Cy, respectively). These compounds display structural parameters typical for CAAC–NHC‐stabilized tricoordinate borylenes,[ 17 , 19 ] with trigonal planar boron centers and short B−CCAAC bonds (ca. 1.45 Å) with double bond character, indicating strong π backbonding from the borylene center to the π‐acidic CAAC ligand. The NHC rings are rotated almost perpendicularly to the borylene plane (torsion angle N4‐B3‐C7‐N8 73–85°) and coordinating as pure σ donors (B2−C7 ca. 1.59 Å). The B3−N4 distance (ca. 1.49 Å) suggests partial π donation from the NCS ligand to boron. [20]

Figure 1.

Crystallographically derived molecular structures of a) (Z)‐2Me (only one of the two molecules present in the asymmetric unit is represented) and b) (E)‐2Cy. [38] Atomic displacement ellipsoids drawn at 50 % probability level. Ellipsoids on the CAAC ligand periphery and hydrogen atoms omitted for clarity. Selected bond lengths (Å) in blue, selected angles (°) in red.

The ca. 5 ppm separation of the 11B NMR shifts of the two isomers, with (Z)‐2R at −2.6 ppm and (E)‐2R at 3.8 ppm, can be explained by Hirshfeld charge analysis, [21] which indicates slightly positive (ca. +0.003) and negative (ca. −0.012) boron atoms for (E)‐2R and (Z)‐2R, respectively. The different steric constraints were also apparent in the 1H NMR spectra, which showed symmetrical ligand resonances indicative of free B−CNHC bond rotation for (Z)‐2R and very broad ligand resonances split into two magnetically inequivalent sets, typical of hindered rotation, for (E)‐2R. [22] NMR spectroscopic analyses of the crude borylene solutions prior to recrystallization showed (E)/(Z) ratios of 22:78 and 15:85 for 2Me and 2Cy. In both cases the preference for the (Z) isomer is explained by the strong steric repulsion between the bulky CAAC‐Dip substituent and IiPr ligand. Heating of a C6D6 solution of isolated (E)‐2Me at 80 °C for 3 days resulted in 97 % conversion to the thermodynamically preferred (Z)‐2Me isomer. [23] Conversely, irradiation of isolated (Z)‐2Me under a UV lamp for 1 day afforded a 75:25 mixture of the (E) and (Z) isomers, respectively. The greater thermodynamic stability of the (Z) isomers is also corroborated by DFT calculations at the OLYP [24] /TZP level, with computed ΔG[(Z)‐(E)‐2R] values of −6.86 kcal mol−1 for R=Me and −5.01 kcal mol−1 for R=Cy. While the vast majority of unsymmetrical borylenes of the type (CAAC)(L)BR are formed exclusively as a single (Z) or (E) isomer, depending on the relative sterics of L and R,[ 19 , 25 ] a similar, thermally induced, reversible isomerization has been observed only recently for the first time in a (CAAC,PMe3)‐stabilized borylborylene, where it was likely induced by the thermal lability of PMe3. [26]

In the absence of a stabilizing Lewis base the twofold reduction of 1R with KC8 in benzene resulted in a color change to intense blue and a new downfield‐shifted 11B NMR resonance around 32 ppm. After workup, dark blue crystals of the bis(CAAC)‐stabilized thiazaborolo[5,4‐d]thiazaboroles 3Me and 3Cy were isolated in 38 % and 67 % yield, respectively. [27]

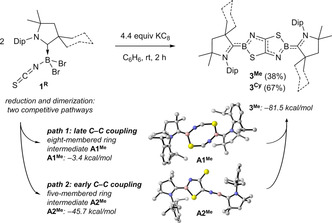

X‐ray crystallographic analyses of 3R (see Figure 2 a for 3Me and Figure S57 in the SI for 3Cy) show fully planar, centrosymmetric structures, with a central TzbTzb unit, formally resulting from dimerization of two dicoordinate (CAACR)B(NCS) borylenes through S→B adduct formation and C−C coupling at the C5 positions. The reaction is somewhat reminiscent of the coupling of four CO molecules at diborynes, which afforded fused bicyclic bis(boralactones). [28] We investigated plausible mechanistic pathways for the reductive cyclization of 1Me using DFT calculations, of which the main intermediates are shown in Scheme 2 (see Figures S62–S63 for a full description). In path 1, the eight‐membered ring A1Me is obtained after a sequence of stepwise S→B adduct formation, with barriers of 14.9 (TS1) and 9.2 kcal mol−1 (TS2′). A C−C coupling step from A1Me leads to 3Me, the formation of which is exergonic by a total of −81.5 kcal mol−1, and with a barrier (TS3′) of 10.3 kcal mol−1 from A1Me. Our calculations reveal a second viable pathway (path 2) where an early C−C coupling takes place after the first S→B adduct formation and leads to the stable intermediate A2Me. The corresponding energy barriers (TS2 and TS3) are lower than those of path 1. Our results thus indicate that both mechanisms are viable, with a preference for path 2, and suggest that the C−C coupling can also occur immediately after the first S→B adduct formation. Conversely, direct C−C coupling from two isolated borylenes is inaccessible, as this occurs via a barrier of 31.9 kcal mol−1 (TS4). Finally, the formation of A1Me from isolated borylenes through a concerted transition state also seems unlikely, and all attempts to optimize such a transition state converged directly to TS1.

Figure 2.

a) Crystallographically derived molecular structure of 3Me. [38] Ellipsoids on the CAAC ligand periphery and hydrogen atoms omitted for clarity. Selected bond lengths (Å) in blue, selected angles (°) in red. b) Plots of HOMO and LUMO of 3Me and 4 at the OLYP/TZP level of theory. c) Low‐energy fully delocalized π orbital of 3Me and [5Me]2+. d) ACID plot of 3Me (isosurface: 0.025).

Scheme 2.

Reductive cyclization of 1R in the absence of a Lewis base.

In comparison to the similarly planar structure of PhTzTzPh, [29] the presence of the boron atoms in the TzbTzb unit results in shortening of the C−N bonds and lengthening of the central C−C bond by less than 3 %, while the C−S bonds remain unaffected. The average N1−C2 (1.33 Å), C2−B3 (1.54 Å), B3−N4 (1.42 Å), N4−C5 (1.33 Å), and C5−C5′ (1.42 Å) bond lengths are all within the range of partial double bonds, indicating π electron delocalization over the entire (NCBNC)2 framework. The B−S distance of ca. 1.86 Å, however, is relatively long for a single bond (compare B(SPh)3: B−S 1.81 Å), [30] suggesting that the sulfur atoms participate less effectively in the delocalized π system of 3R. In order to investigate the role of π delocalization, we analyzed the electronic structure of 3Me and other sulfur‐containing heterocycles, particularly the TzTz analogue of 3Me, 2,5‐bis(2,2,4,4‐tetramethyl‐3,4‐dihydro‐2H‐pyrrol‐5‐yl)thiazolo‐[5,4‐d]thiazole, herein labelled 4, and its dicationic N‐arylated derivative, [5Me]2+, the latter being isoelectronic to 3Me. We show that the HOMO of 3Me, unlike that of 4, is π‐delocalized over the (NCBNC)2 framework with the exclusion of the sulfur atoms (Figure 2 b). Furthermore, analysis of the fully delocalized π orbital of 3Me and [5Me]2+ (Figure 2 c) reveals that delocalization is affected by the presence of the boron atoms due to the increase in energy mismatch between the participating 2p orbitals, [31] and becomes less prominent in 3Me. As a consequence, the aromaticity of the carbene‐stabilized BNC2S cycles is decreased relative to those of the corresponding thiazole rings. [32] Accordingly, calculations using the anisotropy of the induced current density (ACID) [33] method (Figure 2 d, see Section S10 for more details) revealed the presence of a diatropic, clockwise π electron circulation, typical of aromatic compounds, along the bicyclic central structure of 3Me. The attribution of a weak but distinct aromatic character for 3R is also supported by nucleus‐independent chemical shift (NICS) calculations, [34] with the NICS(0), NICS(1) and the zz tensor component at 1 Å above the ring, NICSzz(1), values for 3Me being −6.3, −7.0, and −12.5 ppm, respectively (see SI for comparison with other systems).

In contrast to planar ArTzTzAr compounds (Ar=phenyl, thienyl, thiazenyl, pyridyl), which are generally colorless to yellow,[ 28 , 35 ] 3Me and 3Cy absorb around 675 nm, accounting for the intense blue color (3Me: ϵ=66 200 m −1 cm−1; 3Cy: ϵ=83 300 m −1 cm−1), with secondary absorption maxima around 628 and 453 nm (see Figure S41 in the SI). TDDFT calculations for 3Me (see SI for more details and the relevant MOs) using the double‐hybrid functional B2PLYP [36] with the def2SVPD [37] basis set indicate that the features around 675 and 628 nm are the π→π* transitions HOMO→LUMO (93 %) and HOMO−1→LUMO (93 %), respectively. In turn, two states contribute to the band around 453 nm, namely S7 and S9. The former mainly results from the charge transfer excitation from HOMO−1 to LUMO+4 (88 %), while the latter is related to a n→π* transition (HOMO−7→LUMO, 44 %; HOMO−2→LUMO+1, 41 %). Substitution of the two carbon atoms in 4 with electron‐deficient boron atoms is followed by a significant reduction of the HOMO–LUMO gap of 3Me, and explains the pronounced red‐shift of its lowest‐energy absorption band. This highlights once more the significant electronic differences between the boron‐doped thiazolothiazole and its carbon analogue.

To conclude we have shown that the reduction of CAAC‐stabilized isothiocyanatoboranes in the presence of a Lewis base results in the formation of doubly base‐stabilized borylenes, whereas in the absence of a Lewis base dimerization and C−C coupling of two (NCS) units leads to [1,3,2]thiazaborolo[5,4‐d][1,3,2]thiazaboroles. While the latter are less aromatic than their thiazolothiazole counterparts, they display an intense blue coloration, whereas their carbon analogues are colorless. We are currently studying the reactivity and photophysics of these novel boron‐doped fused heterocycles and will report our findings in due course.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft for financial support. S.H. is grateful for a doctoral fellowship from the Studienstiftung des deutschen Volkes. F.F. thanks the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento Pessoal de Nível Superior and the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation for a CAPES‐Humboldt Research Fellowship. A.V. thanks the University of Sussex for financial support. Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

S. Hagspiel, M. Arrowsmith, F. Fantuzzi, A. Vargas, A. Rempel, A. Hermann, T. Brückner, H. Braunschweig, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 6446.

Dedicated to Professor Todd B. Marder on the occasion of his 65th birthday

References

- 1. Osaka I., Polym. J. 2015, 47, 18–25; [Google Scholar]; Bevk D., Marin L., Lutsen L., Vanderzandeab D., Maes W., RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 11418–11431; [Google Scholar]; Osaka I., Zhang R., Liu J., Smilgies D.-M., Kowalewski T., McCullough R. D., Chem. Mater. 2010, 22, 4191–4196. [Google Scholar]

- 2.

- 2a. Li R., Yang X., J. Phys. Chem. A 2019, 123, 10102–10108; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2b. Yan W., Chaitanya K., Sun Z.-D., Ju X.-H., J. Mol. Model. 2018, 24, 68; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2c. Moral M., Garzón A., Canales-Vázquez J., Sancho-García J. C., J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 24583–24596; [Google Scholar]

- 2d. Fitri A., Benjelloun A. T., Benzakour M., Mcharfi M., Sfaira M., Hamidi M., Bouachrine M., Res. Chem. Intermed. 2013, 39, 2679–2695. [Google Scholar]

- 3.

- 3a. Chen N.-Y., Yue Q., Liu W., Zhang H.-L., Zhu X., J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 5234–5238; [Google Scholar]

- 3b. Lim D.-H., Jang S.-Y., Kang M., Lee S., Kim Y.-A., Heo Y.-J., Lee M.-H., Kim D.-Y., J. Mater. Chem. C 2017, 5, 10126–10132; [Google Scholar]

- 3c. Kudrjasova J., Van Landeghem M., Vangerven T., Kesters J., Heintges G. H. L., Cardinaletti I., Lenaerts R., Penxten H., Adriaensens P., Lutsen L., Vanderzande D., Manca J., Goovaerts E., Maes W., ChemistrySelect 2017, 2, 1253–1261; [Google Scholar]

- 3d. Reginato G., Mordini A., Zani L., Calamante M., Dessì A., Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 233–251; [Google Scholar]

- 3e. Zhang Z., Chen Y.-A., Hung W.-Y., Tang W.-F., Hsu Y.-H., Chen C.-L., Meng F.-Y., Chou P.-T., Chem. Mater. 2016, 28, 8815–8824; [Google Scholar]

- 3f. Lin Y., Fan H., Li Y., Zhan X., Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, 3087–3106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.

- 4a. Sayresmith N. A., Saminathan A., Sailer J. K., Patberg S. M., Sandor K., Krishnan Y., Walter M. G., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 18780–18790; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4b. Khatun A., Panda D. K., Sayresmith N., Walter M. G., Saha S., Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 12707–12715; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4c. Sathiyan G., Chatterjee G., Sen P., Garg A., Gupta R. K., Singh A., ChemistrySelect 2019, 4, 11718–11725. [Google Scholar]

- 5.

- 5a. Huang Q., Guo L., Wang N., Zhu X., Jin S., Tan B., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 15861–15868; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5b. Biswal B. P., Vignolo-González H. A., Banerjee T., Grunenberg L., Savasci G., Gottschling K., Nuss J., Ochsenfeld C., Lotsch B. V., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 11082–11092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Roy I., Bobbala S., Zhou J., Nguyen M. T., Nalluri S. K. M., Wu Y., Ferris D. P., Scott E. A., Wasielewski M. R., Stoddart J. F., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 7206–7212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tang B., Li W.-L., Chang Y., Yuan B., Wu Y., Zhang M.-T., Xu J.-F., Li L., Zhang X., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 15526–15531; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2019, 131, 15672–15677. [Google Scholar]

- 8.

- 8a. McConnell C. R., Liu S.-Y., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 3436–3453; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8b. Goettel J. T., Braunschweig H., Coord. Chem. Rev. 2019, 380, 184–200; [Google Scholar]

- 8c. Giustra Z. X., Liu S.-Y., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 1184–1194; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8d. Su B., Kinjo R., Synthesis 2017, 49, 2985–3034; [Google Scholar]

- 8e. Bélanger-Chabot G., Braunschweig H., Roy D. K., Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 4353–4368; [Google Scholar]

- 8f. Abbey E. R., Liu S.-Y., Org. Biomol. Chem. 2013, 11, 2060–2069; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8g. Bosdet M. J. D., Piers W. E., Can. J. Chem. 2009, 87, 8–29. [Google Scholar]

- 9.

- 9a. Su X., Baker J. J., Martin C. D., Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 126–131; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9b. Matsuo K., Yasuda T., Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 2501–2504; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9c. Yan Y., Sun Z., Li C., Zhang J., Lv L., Liu X., Liu X., Asian J. Org. Chem. 2017, 6, 496–502; [Google Scholar]

- 9d. Yruegas S., Martin C. D., Chem. Eur. J. 2016, 22, 18358–18361; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9e. Rohr A. D., Banaszak Holl M. M., Kampf J. W., A. J. Ashe III , Organometallics 2011, 30, 3698–3700; [Google Scholar]

- 9f. Kobayashi J., Kato K., Agou T., Kawashima T., Chem. Asian J. 2009, 4, 42–49; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9g. Agou T., Kobayashi J., Kawashima T., Chem. Eur. J. 2007, 13, 8051–8060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.

- 10a. Morales H. R., Tlahuext H., Santiesteban F., Contreras R., Spectrochim. Acta Part A 1984, 40, 855–862; [Google Scholar]

- 10b. Niedenzu K., Dawson J. W., Fritz P. W., Weber W., Chem. Ber. 1967, 100, 1898–1901; [Google Scholar]

- 10c. Harris J. J., Rudner B., J. Org. Chem. 1962, 27, 3848–3851; [Google Scholar]

- 10d. Pailer M., Fenzl W., Monatsh. Chem. 1961, 92, 1294–1299; [Google Scholar]

- 10e. Dewar M. J. S., Kubba V. P., Pettit R., J. Chem. Soc. 1958, 3076–3079. [Google Scholar]

- 11.

- 11a. Padilla-Martínez I. I., Andrade-López N., Gama-Goicochea M., Aguilar-Cruz E., Cruz A., Contreras R., Tlahuext H., Heteroat. Chem. 1996, 7, 323–335; [Google Scholar]

- 11b. Uzarewicz I., Maringgele W., Meller A., Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 1990, 590, 151–160; [Google Scholar]

- 11c. Contreras R., Morales H. R., de L. Mendoza M., Dominguez C., Spectrochim. Acta Part A 1987, 43, 43–49. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dixit V. A., Goundry W. R. F., Tomasi S., New J. Chem. 2017, 41, 3619–3633. [Google Scholar]

- 13.

- 13a. Reddy G. N., Parida R., Jena P., Jana M., Giri S., ChemPhysChem 2019, 20, 1607–1612; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13b. Reddy G. N., Parida R., Giri S., Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 9942–9945; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13c. Reddy G. N., Giri S., RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 47145–47150. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Irvine G. J., Roper W. R., Wright L. J., Organometallics 1997, 16, 2291–2296. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Saxena C., Singh R. V., J. Inorg. Biochem. 1995, 57, 209–218; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Settepani J. A., Stokes J. B., Borkovec A. B., J. Med. Chem. 1970, 13, 128–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Takahiro K., Jun-ichi N., Shizuo T., Yoshiro Y., Chem. Lett. 2008, 37, 1122–1123. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Arrowsmith M., Auerhammer D., Bertermann R., Braunschweig H., Bringmann G., Celik M. A., Dewhurst R. D., Finze M., Grüne M., Hailmann M., Hertle T., Krummenacher I., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 14464–14468; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2016, 128, 14680–14684. [Google Scholar]

- 18.See the Supporting Information for details of the syntheses of all precursors and their crystallographically derived structures (Figures S50–S54).

- 19.

- 19a. Hermann A., Arrowsmith M., Trujillo-Gonzalez D. E., Jiménez-Halla J. O. C., Vargas A., Braunschweig H., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 5562–5567; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19b. Arrowsmith M., Schweizer J. I., Heinz M., Härterich M., Krummenacher I., Holthausen M. C., Braunschweig H., Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 5095–5103; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19c. Böhnke J., Arrowsmith M., Braunschweig H., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 10368–10373; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19d. Braunschweig H., Krummenacher I., Légaré M.-A., Matler A., Radacki K., Ye Q., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 1802–1805; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19e. Ruiz D. A., Melaimi M., Bertrand G., Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 7837–7839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Straub D. K., J. Chem. Educ. 1995, 72, 494–497. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hirshfeld F. L., Theor. Chim. Acta 1977, 44, 129–138. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Analysis of the coalescence of various 1H NMR resonances in the 25–70 °C temperature range provided an estimate of 15.8 kcal mol−1 for the Gibbs free energy of activation of the B−CNHC bond rotation (see details in Figure S38 and Table S1 in the SI). Additionally, low-temperature 1H NMR spectra were recorded that revealed sharpening of the signals of (E)-2Me upon cooling to 0 °C already. At −40 °C coalescence for the IiPr resonances could be observed, followed by new broadening of the signals of both isomers at −80 °C (see Figure S39 in the SI).

- 23.Because the time required to reach three half-lives for this reaction exceeded two days no kinetic analysis was performed.

- 24.

- 24a. Lee C., Yang W., Parr R. G., Phys. Rev. B 1988, 37, 785–789; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24b. Miehlich B., Savin A., Stoll H., Preuss H., Chem. Phys. Lett. 1989, 157, 200–206; [Google Scholar]

- 24c. Handy N. C., Cohen A. J., Mol. Phys. 2001, 99, 403–412; [Google Scholar]

- 24d. Hoe W.-M., Cohen A. J., Handy N. C., Chem. Phys. Lett. 2001, 341, 319–328. [Google Scholar]

- 25.

- 25a. Hofmann A., Légaré M.-A., Wüst L., Braunschweig H., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 9776–9781; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2019, 131, 9878–9883; [Google Scholar]

- 25b. Légaré M.-A., Bélanger-Chabot G., Dewhurst R. D., Welz E., Krummenacher I., Engels B., Braunschweig H., Science 2018, 359, 896–900; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25c. Stoy A., Böhnke J., Jimenéz-Halla J. O. C., Dewhurst R. D., Thiess T., Braunschweig H., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 5947–5951; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 6055–6059; [Google Scholar]

- 25d. Arrowsmith M., Böhnke J., Braunschweig H., Celik M. A., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 14287–14292; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2017, 129, 14475–14480; [Google Scholar]

- 25e. Arrowsmith M., Auerhammer D., Bertermann R., Braunschweig H., Celik M. A., Erdmannsdörfer J., Kupfer T., Krummenacher I., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 11263–11267; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2017, 129, 11417–11421; [Google Scholar]

- 25f. Dahcheh F., Martin D., Stephan D. W., Bertrand G., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 13159–13163; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2014, 126, 13375–13379. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pranckevicius C., Weber M., Krummenacher I., Phukan A. K., Braunschweig H., Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 11055–11059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.The low crystalline yield of 3Me is due to the extremely high solubility of the compound even in minimal amounts of pentane at low temperature.

- 28.

- 28a. Böhnke J., Braunschweig H., Dellermann T., Ewing W. C., Hammond K., Kramer T., Jimenez-Halla J. O. C., Mies J., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 13801–13805; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 14006–14010; [Google Scholar]

- 28b. Braunschweig H., Dellermann T., Dewhurst R. D., Ewing W. C., Hammond K., Jimenez-Halla J. O. C., Kramer T., Krummenacher I., Mies J., Phukan A. K., Vargas A., Nat. Chem. 2013, 5, 1025–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Biswal B. P., Becker D., Chandrasekhar N., Seenath J. S., Paasch S., Machill S., Hennersdorf F., Brunner E., Weigand J. J., Berger R., Feng X., Chem. Eur. J. 2018, 24, 10868–10875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mock M. T., Potter R. G., Camaioni D. M., Li J., Dougherty W. G., Kassel W. S., Twamley B., DuBois D. L., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 14454–14465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Roy D. K., Tröster T., Fantuzzi F., Dewhurst R. D., Lenczyk C., Radacki K., Pranckevicius C., Engels B., Braunschweig H., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 10.1002/anie.202014557; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2020, 10.1002/ange.202014557. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Horner K. E., Karadakov P. B., J. Org. Chem. 2015, 80, 7150–7157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.

- 33a. Herges R., Geuenich D., J. Phys. Chem. A 2001, 105, 3214–3220; [Google Scholar]

- 33b. Geuenich D., Hess K., Köhler F., Herges R., Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 3758–3772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.

- 34a. Schleyer P. v. R., Maerker C., Dransfeld A., Jiao H., Hommes N. J. R. v. E., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 6317–6318; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34b. Chen Z., Wannere C. S., Corminboeuf C., Puchta R., Schleyer P. v. R., Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 3842–3888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.

- 35a. Dessì A., Calamante M., Mordini A., Zani L., Taddei M., Reginato G., RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 1322–1328; [Google Scholar]

- 35b. Tao T., Geng J., Hong L., Huang W., Tanaka H., Tanaka D., Ogawa T., J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 25325–25333; [Google Scholar]

- 35c. Wagner P., Kubicki M., Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C 2003, 59, o91–o92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Grimme S., J. Chem. Phys. 2006, 124, 034108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.

- 37a. Weigend F., Ahlrichs R., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7, 3297; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37b. Rappoport D., Furche F., J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 133, 134105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Deposition Numbers 2045415 ((Z)-2Me), 2045409 ((E)-2Cy), and 2045414 (3Me) contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data are provided free of charge by the joint Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre and Fachinformationszentrum Karlsruhe Access Structures service www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary