Abstract

Background

Cotton fiber is a model system for studying plant cell development. At present, the functions of many transcription factors in cotton fiber development have been elucidated, however, the roles of auxin response factor (ARF) genes in cotton fiber development need be further explored.

Results

Here, we identify auxin response factor (ARF) genes in three cotton species: the tetraploid upland cotton G. hirsutum, which has 73 ARF genes, and its putative extent parental diploids G. arboreum and G. raimondii, which have 36 and 35 ARFs, respectively. Ka and Ks analyses revealed that in G. hirsutum ARF genes have undergone asymmetric evolution in the two subgenomes. The cotton ARFs can be classified into four phylogenetic clades and are actively expressed in young tissues. We demonstrate that GhARF2b, a homolog of the Arabidopsis AtARF2, was preferentially expressed in developing ovules and fibers. Overexpression of GhARF2b by a fiber specific promoter inhibited fiber cell elongation but promoted initiation and, conversely, its downregulation by RNAi resulted in fewer but longer fiber. We show that GhARF2b directly interacts with GhHOX3 and represses the transcriptional activity of GhHOX3 on target genes.

Conclusion

Our results uncover an important role of the ARF factor in modulating cotton fiber development at the early stage.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12864-021-07504-6.

Keywords: Cotton, GhARF2b, Fiber elongation, Fiber initiation

Background

Cotton is the most important natural and renewable material for the textile industry in the world [1]. The primary cultivated species upland cotton (G. hirsutum L.) is grown in over 80 countries and accounts for more than 90% of global cotton fiber output. Cotton fibers are unusually long, single-celled epidermal seed trichomes and a model for plant cell growth research [2]. Fiber development can be divided into four overlapping stages: initiation, elongation, secondary cell wall biosynthesis and maturation [3]. The fiber length and density are both key traits that determine cotton quality and yield.

The study of cotton fiber development regulation provides not only valuable knowledge to understanding plant cell growth and cell wall biosynthesis, but also candidate genes for cotton molecular breeding [4]. To date a number of genes that function in cotton fiber cells have been identified, including homeodomain transcription factor GaHOX1, GhHOX3 and GhHD1 [5–7], bHLH transcription factor GhPRE1 [8], KNOX transcription factor knl1 [9], the sterol carrier gene [10], MYB transcription factors GhMYB25, GhMYB25-like, GhMML3 and GhMML4 [11–14], NAC transcription factor fsn1 [15], transcription factor WLIM1a gene [16], sucrose synthase gene [17], cotton actin1 gene [18], cotton BURP domain protein GhRDL1 [19], ethylene pathway related genes [20], fasciclin-like arabinogalactan protein, Ghfla1 [21], and TCP transcription factor GhTCP4 [22] etc. Among recent progresses are the characterizations of transcription factors which regulate the major events of cotton fiber development, such as MYBs and HD-ZIP IVs involved in cotton fiber initiation and elongation, as well as a number of other types of factors. The MIXTA type MYB transcription factors (GhMYB25, GhMYB25-like and GhMML4_D12) are master regulators of cotton fiber initiation [11, 13, 14] and lint fiber development [12], whereas the HD-ZIP IV transcription factor GhHOX3 plays a pivotal role in controlling fiber elongation [5], whose activity is regulated by the phytohormone gibberellin. In addition, NAC (GhFSN1) and TCP4 transcription factors positively regulates secondary cell wall biosynthesis [15, 22]. However, cotton fiber growth and development are complex processes involving cell differentiation, cell skeleton orientation growth, cell wall synthesis, and so on [23]. Currently the picture of the regulation network of cotton fiber is far from complete.

Auxin response factors (ARFs), a group of plant transcription factors, are composed of a conserved N-terminal DNA binding domain (DBD), a most case conserved C-terminal dimerization domain (CTD) and a non-conserved middle region (MR) [24]. The MR region has been proposed to function as a repression or an activation domain [25]. Arabidopsis thaliana contains 23 ARF genes and Oryza sativa has 25 [26, 27]. It has been reported that ARF2 negatively modulates plant growth in A. thaliana [26, 28–30] and tomato [31], yet functions of transcription factors can vary with tissues and more diversified in polyploid species, to date the role ARF2 in cotton fiber cells has not been explored.

In this study, we conducted a genome-wide analysis ARF genes in three cotton species (G. hirsutum, G. arboreum and G. raimondii), and classified them into four clades. In G. hirsutum most ARF genes were expressed in multiple cotton tissues, among which GhARF2b exhibited a preferential expression in developing cotton fiber cells, and it negatively affects cotton fiber elongation but plays a role in promoting fiber initiation.

Results

ARF transcription factors in G. arboreum and G. hirsutum

The genome sequences of G. raimondii and G. arboreum provide us data resources to conduct a genome-wide screen of the ARF genes in the extent diploid progenitors of the allotetraploid G. hirsutum. In the previous studies, Sun et al., (2015) identified 35 ARF genes in G. raimondii [32]. To mine more ARF transcription factors in cottons the conserved domain (Pfam ID: PF06507) was used to hmmersearch against the G. arboreum and G. hirsutum genome databases, which resulted in 36 and 73 genes in G. arboreum and G. hirsutum genomes, respectively. The 36 G. arboreum ARF genes were designated GaARF1–GaARF20, and the 73 G. hirsutum ARF genes in A- and D-subgenomes were designated as GhARF1A/D–GhARF21A/D (Table 1). As those of Arabidopsis, cotton ARF proteins are composed of three domain regions, including DBD (DNA-binding Domain), MI (Middle Region) and CTD (C-terminal Domain) (Additional file 1: Figure S1).

Table 1.

Ka, Ks and Ka/Ks analyses of GhARF genes compared with their corresponding progenitor homoeologs

| Locus Name | Gene Name | Chrom | Locus Name | Gene Name | Chrom | Ka | Ks | Ka/Ks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gh_A10G1402 | GhARF1_A | A10 | Cotton_A_31395 | GaARF1 | CA_chr1 | 0.0147 | 0.0261 | 0.5632 |

| Gh_D10G0803 | GhARF1_D | D10 | Gorai.011G091100.1 | GrARF1 | Chr11 | 0.0019 | 0.0108 | 0.1759 |

| Gh_A07G0411 | GhARF2a_A | A07 | Cotton_A_03644 | GaARF2a | CA_chr1 | 0.0035 | 0.0068 | 0.5147 |

| Gh_D07G0476 | GhARF2a_D | D07 | Gorai.001G054600.1 | GrARF2a | Chr1 | 0.0061 | 0.0169 | 0.3609 |

| Gh_A11G0358 | GhARF2b_A | A11 | Cotton_A_01955 | GaARF2b | CA_chr6 | 0.0015 | 0.0151 | 0.0993 |

| Gh_D11G0416 | GhARF2b_D | D11 | Gorai.007G044900.1 | GrARF2b | Chr7 | 0.0028 | 0.0045 | 0.6222 |

| Gh_D12G1909 | GhARF2c_D | D12 | Gorai.008G210200.1 | GrARF2c | Chr8 | 0.0083 | 0.0263 | 0.3156 |

| Gh_A11G1082 | GhARF2d_A | A11 | Cotton_A_08273 | GaARF2d | CA_chr4 | 0.0012 | 0.0021 | 0.5714 |

| Gh_D11G1233 | GhARF2d_D | D11 | Gorai.007G131900.1 | GrARF2d | Chr7 | 0.0058 | 0.0181 | 0.3204 |

| Gh_A08G0656 | GhARF2e_A | A08 | Cotton_A_22543 | GaARF2e | CA_chr10 | 0.0032 | 0.0000 | 2.0000 |

| Gh_D08G0758 | GhARF2e_D | D08 | Gorai.004G085400.1 | GrARF2e | Chr4 | 0.0098 | 0.0213 | 0.4601 |

| Gh_A10G0266 | GhARF3a_A | A10 | Cotton_A_03933 | GaARF3a | CA_chr9 | 0.0096 | 0.0167 | 0.5749 |

| Gh_D10G0266 | GhARF3a_D | D10 | Gorai.011G030900.1 | GrARF3a | Chr11 | 0.0038 | 0.0125 | 0.3040 |

| Gh_A06G2038 | GhARF3b_A | A06 | Cotton_A_40208 | GaARF3b | CA_chr8 | 0.0019 | 0.0060 | 0.3167 |

| Gh_D06G1415 | GhARF3b_D | D06 | Gorai.010G157400.1 | GrARF3b | Chr10 | 0.0089 | 0.0077 | 1.1558 |

| Gh_A05G1337 | GhARF3c_A | A05 | Cotton_A_11311 | GaARF3c | CA_chr10 | 0.0165 | 0.0140 | 1.1786 |

| Gh_D05G1506 | GhARF3c_D | D05 | Gorai.009G166100.1 | GrARF3c | Chr9 | 0.0018 | 0.0076 | 0.2368 |

| Gh_A09G0993 | GhARF4a_A | A09 | Cotton_A_01738 | GaARF4a | CA_chr11 | 0.0017 | 0.0116 | 0.1466 |

| Gh_A05G3908 | GhARF4b_A | A05 | Cotton_A_11048 | GaARF4b | CA_chr10 | 0.0027 | 0.0018 | 1.5000 |

| Gh_A01G0908 | GhARF5a_A | A01 | Cotton_A_27669 | GaARF5a | CA_chr13 | 0.0009 | 0.0110 | 0.0818 |

| Gh_D01G0951 | GhARF5a_D | D01 | Gorai.002G124400.1 | GrARF5a | Chr2 | 0.0032 | 0.0094 | 0.3404 |

| Gh_A05G1607 | GhARF5b_A | A05 | Cotton_A_16408 | GaARF5b | CA_chr8 | 0.0046 | 0.0079 | 0.5823 |

| Gh_D05G1792 | GhARF5b_D | D05 | Gorai.009G196100.1 | GrARF5b | Chr9 | 0.0067 | 0.0172 | 0.3895 |

| Gh_A10G0412 | GhARF6a_A | A10 | Cotton_A_02933 | GaARF6a | CA_chr9 | 0.0038 | 0.0159 | 0.2390 |

| Gh_D10G0426 | GhARF6a_D | D10 | Gorai.011G048200.1 | GrARF6a | Chr11 | 0.0019 | 0.0047 | 0.4043 |

| Gh_A05G1225 | GhARF6b_A | A05 | Cotton_A_26156 | GaARF6b | CA_chr10 | 0.0034 | 0.0095 | 0.3579 |

| Gh_D05G3848 | GhARF6b_D | D05 | Gorai.009G152700.1 | GrARF6b | Chr9 | 0.0107 | 0.0205 | 0.5220 |

| Gh_D07G1785 | GhARF8a_D | D07 | Gorai.001G204500.1 | GrARF8a | Chr1 | 0.0028 | 0.0091 | 0.3077 |

| Gh_A12G0813 | GhARF8b_A | A12 | Cotton_A_35443 | GaARF8b | CA_chr6 | 0.0017 | 0.0054 | 0.3148 |

| Gh_D12G0831 | GhARF8b_D | D12 | Gorai.008G097200.1 | GrARF8b | Chr8 | 0.0039 | 0.0049 | 0.7959 |

| Gh_A12G0483 | GhARF8c_A | A12 | Cotton_A_21333 | GaARF8c | CA_chr6 | 0.0235 | 0.0303 | 0.7756 |

| Gh_D12G0491 | GhARF8c_D | D12 | Gorai.008G054600.1 | GrARF8c | Chr8 | 0.0061 | 0.0167 | 0.3653 |

| Gh_A09G0074 | GhARF8d_A | A09 | Cotton_A_14740 | GaARF8d | CA_chr11 | 0.0030 | 0.0131 | 0.2290 |

| Gh_D09G0071 | GhARF8d_D | D09 | Gorai.006G008700.1 | GrARF8d | Chr6 | 0.0031 | 0.0150 | 0.2067 |

| Gh_A11G0231 | GhARF9a_A | A11 | Cotton_A_18937 | GaARF9a | CA_chr10 | 0.0108 | 0.0301 | 0.3588 |

| Gh_D11G0245 | GhARF9a_D | D11 | Gorai.007G026900.1 | GrARF9a | Chr7 | 0.0098 | 0.0198 | 0.4949 |

| Gh_A02G0979 | GhARF9b_A | A02 | Cotton_A_36154 | GaARF9b | CA_chr7 | 0.0013 | 0.0044 | 0.2955 |

| Gh_D03G0771 | GhARF9b_D | D03 | Gorai.003G078000.1 | GrARF9b | Chr3 | 0.0019 | 0.0064 | 0.2969 |

| Gh_A03G0274 | GhARF10a_A | A03 | Cotton_A_04263 | GaARF10a | CA_chr7 | 0.0013 | 0.0062 | 0.2097 |

| Gh_D03G1293 | GhARF10a_D | D03 | Gorai.003G142500.1 | GrARF10a | Chr3 | 0.0058 | 0.0171 | 0.3392 |

| Gh_A05G0895 | GhARF10b_A | A05 | Cotton_A_07064 | GaARF10b | CA_chr10 | 0.0038 | 0.0102 | 0.3725 |

| Gh_D05G0978 | GhARF10b_D | D05 | Gorai.009G107800.1 | GrARF10b | Chr9 | 0.0025 | 0.0185 | 0.1351 |

| Gh_A07G1254 | GhARF11_A | A07 | Cotton_A_31049 | GaARF11 | CA_chr1 | 0.0044 | 0.0105 | 0.4190 |

| Gh_A10G1836 | GhARF16a_A | A10 | Cotton_A_23397 | GaARF16a | CA_chr9 | 0.0019 | 0.0150 | 0.1267 |

| Gh_D10G2093 | GhARF16a_D | D10 | Gorai.011G238900.1 | GrARF16a | Chr11 | 0.0063 | 0.0193 | 0.3264 |

| Gh_A05G3576 | GhARF16b_A | A05 | Cotton_A_06107 | GaARF16b | CA_chr12 | 0.0097 | 0.0066 | 1.4697 |

| Gh_D04G0030 | GhARF16b_D | D04 | Gorai.012G004800.1 | GrARF16b | Chr12 | 0.0051 | 0.0087 | 0.5862 |

| Gh_A09G1401 | GhARF16c_A | A09 | Cotton_A_24047 | GaARF16c | CA_chr10 | 0.0031 | 0.0103 | 0.3010 |

| Gh_D09G1405 | GhARF16c_D | D09 | Gorai.006G166400.1 | GrARF16c | Chr6 | 0.0025 | 0.0081 | 0.3086 |

| Gh_A13G2013 | GhARF16d_A | A13 | Cotton_A_10518 | GaARF16d | CA_chr8 | 0.0080 | 0.0109 | 0.7339 |

| Gh_D13G2411 | GhARF16d_D | D13 | Gorai.013G267100.1 | GrARF16d | Chr13 | 0.0041 | 0.0223 | 0.1839 |

| Gh_A05G1991 | GhARF17a_A | A05 | Cotton_A_16138 | GaARF17a | CA_chr10 | 0.0030 | 0.0243 | 0.1235 |

| Gh_D05G3805 | GhARF17a_D | D05 | Gorai.009G241900.1 | GrARF17a | Chr9 | 0.0015 | 0.0121 | 0.1240 |

| Gh_A06G0332 | GhARF17b_A | A06 | Cotton_A_18446 | GaARF17b | CA_chr8 | 0.0030 | 0.0025 | 1.2000 |

| Gh_D06G0360 | GhARF17b_D | D06 | Gorai.010G046000.1 | GrARF17b | Chr10 | 0.0076 | 0.0099 | 0.7677 |

| Gh_A11G0886 | GhARF18a_A | A11 | Cotton_A_14407 | GaARF18a | CA_chr4 | 0.0041 | 0.0074 | 0.5541 |

| Gh_D11G1034 | GhARF18a_D | D11 | Gorai.007G109500.1 | GrARF18a | Chr7 | 0.0057 | 0.0133 | 0.4286 |

| Gh_A12G1016 | GhARF18b_A | A12 | Cotton_A_25871 | GaARF18b | CA_chr6 | 0.0045 | 0.0150 | 0.3000 |

| Gh_D12G1134 | GhARF18b_D | D12 | Gorai.008G126200.1 | GrARF18b | Chr8 | 0.0026 | 0.0201 | 0.1294 |

| Gh_A06G0710 | GhARF19.1a_A | A06 | Cotton_A_38575 | GaARF19.1a | CA_chr13 | 0.0048 | 0.0130 | 0.3692 |

| Gh_D06G0818 | GhARF19.1a_D | D06 | Gorai.010G091300.1 | GrARF19.1a | Chr10 | 0.0293 | 0.0343 | 0.8542 |

| Gh_A07G2353 | GhARF19.1b_A | A07 | Cotton_A_05677 | GaARF19.1b | CA_chr1 | 0.0042 | 0.0218 | 0.1927 |

| Gh_D07G0132 | GhARF19.1b_D | D07 | Gorai.001G017000.1 | GrARF19.1b | Chr1 | 0.0032 | 0.0113 | 0.2832 |

| Gh_A05G3541 | GhARF19.2_A | A05 | Cotton_A_06071 | GaARF19.2 | CA_chr12 | 0.0148 | 0.0254 | 0.5827 |

| Gh_D04G0067 | GhARF19.2_D | D04 | Gorai.012G009000.1 | GrARF19.2 | Chr12 | 0.0039 | 0.0040 | 0.9750 |

| Gh_A05G0264 | GhARF20_A | A05 | Cotton_A_27843 | GaARF20 | CA_chr9 | 0.0020 | 0.0121 | 0.1653 |

| Gh_D08G1407 | GhARF21_D | D08 | Gorai.006G045300.1 | GrARF21 | Chr6 | 0.1826 | 0.2293 | 0.7963 |

Phylogenetic analysis of Gossypium ARF proteins

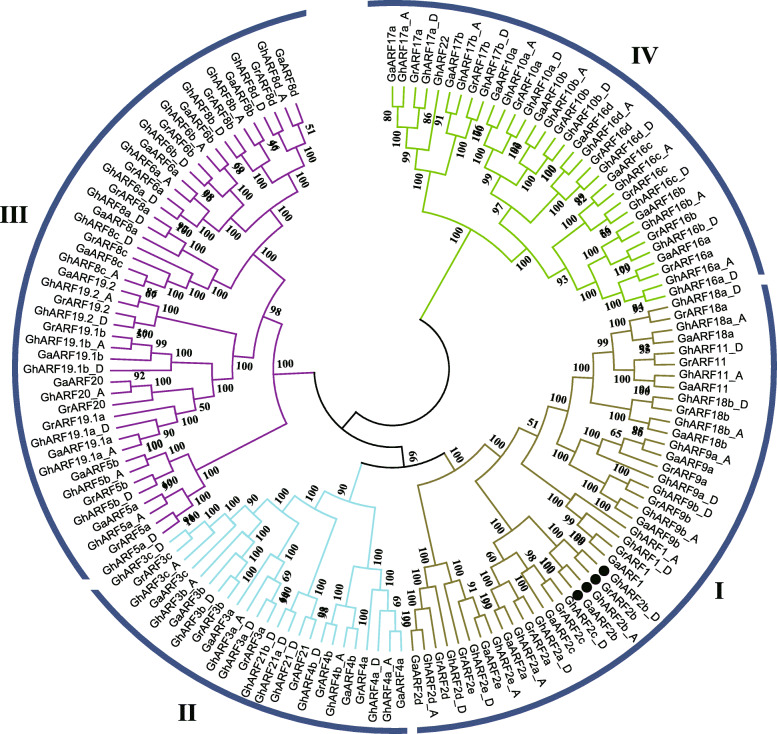

To illustrate the evolutionary relationships among the cotton ARFs, a phylogenetic tree was constructed using the protein sequences of 144 cotton ARFs, which were clustered into four clades (I–IV). The highest number of Gossypium ARFs are found in clade III and I, followed by clade IV and II (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic trees of Gossypium ARFs family. 144 Gossypium ARFs were divided into four clades. Black dots represent the ARF2b genes in three Gossypium species

Overall, the expected diploid-polyploid topology is reflected in the tree for each set of orthologous/homoeologous genes, indicating general preservation during divergence of diploids and through the polyploid formation. We found that the number of ARF genes in G. hirsutum are approximately twice that in G. raimondii and G. arboreum, with one At or Dt homoeologous copy corresponding to one ortholog in each of the diploid cottons. Further, as shown in Fig. 1, the orthologous paired genes of the A genome (G. arboreum) and At sub-genome, or from the D genome (G. raimondii) and Dt sub-genome, tend to be clustered together and share a sister relationship.

Divergence of ARF genes in allotetraploid G. hirsutum and its diploid progenitors

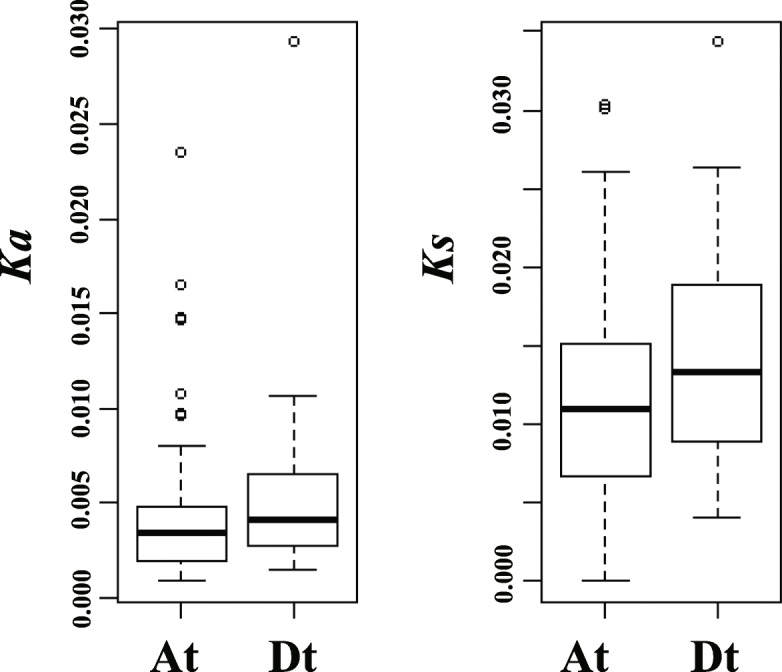

The ARF genes in the two diploid species were then compared with G. hirsutum At- and Dt-subgenome homoeologs (Table 1). To explore the evolutionary relationship and possible functional divergence of ARF genes between the allotetraploid cotton and its extend diploid progenitors, the nonsynonymous substitution (Ka) and synonymous substitution values (Ks) and the Ka/Ks ratios for each pair of the genes were calculated (Table 1). By comparing the Ka and Ks values of 66 orthologous gene sets between the allotetraploid and its diploid progenitor genomes, we found that the Ka and Ks values are higher in the Dt subgenome than in the At subgenome (Fig. 2). These results indicate that GhARF genes in the Dt subgenome tend to have experienced faster sequence divergence than their At counterparts, suggesting an inconsistent evolution of ARF genes in the two subgenomes (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Distribution of Ka and Ks values of ARF genes between the A and D subgenomes versus their corresponding diploid progenitor homoeologs

In addition, the Ka/Ks ratios of one Dt-subgenome genes (GhARF3b_D) and five At-subgenome gene (GhARF2e_A, GhARF3c_A, GhARF4b_A, GhARF16b_A and GhARF17b_A) are greater than 1 (Table 1), suggesting that these genes have under positive selections after divergence of G. hirsutum from diploid ancestors, and may have gained new functions.

Expression analysis of GhARF genes in different cotton tissues

The expression profile of a gene family can provide valuable clues to possible functions of each genes. Analysis of 73 GhARF genes showed that most genes have different spatial expression patterns. For instance, GhARF1, GhARF2a, GhARF2b and GhARF2c were expressed in all the tissues of cotton examined (Additional file 2: Figure S2), whereas GhARF3a and GhARF3c were expressed preferentially in the pistils and ovules. Compared to GhARF5b, GhARF5a showed higher expressions in the root, pistil and ovule organs. Transcripts of GhARF3c and GhARF4a, GhARF9a and GhARF9b were most abundant in stem and root, respectively. Over half of GhARF genes showed a relatively high level of transcript accumulation in leaf. Notably, there are more than 10 genes (including GhARF1, GhARF2a, GhARF2b, GhARF8a, GhARF9a, GhARF10b, GhARF11, GhARF16a, GhARF18 and GhARF19) that were highly expressed in cotton fiber cells at the fast elongation stage (5 dpa).

Among them, GhARF2 genes showed the highest expression in fiber (5 dpa) and were located in the Clade I of phylogenetic tree (Fig. 1), suggesting that they may function in cotton fiber development. Previous studies have demonstrated that ARF2 plays a role in transcriptional regulation in auxin-mediated cell division [30], leaf longevity [33], response to stress [34], regulation of fruit ripening [31] and so on. As GhARF2s shown pleiotropic effects on plant development [35], we decided to identify the major GhARF2s in regulation of cotton fiber elongation in subsequent experiments.

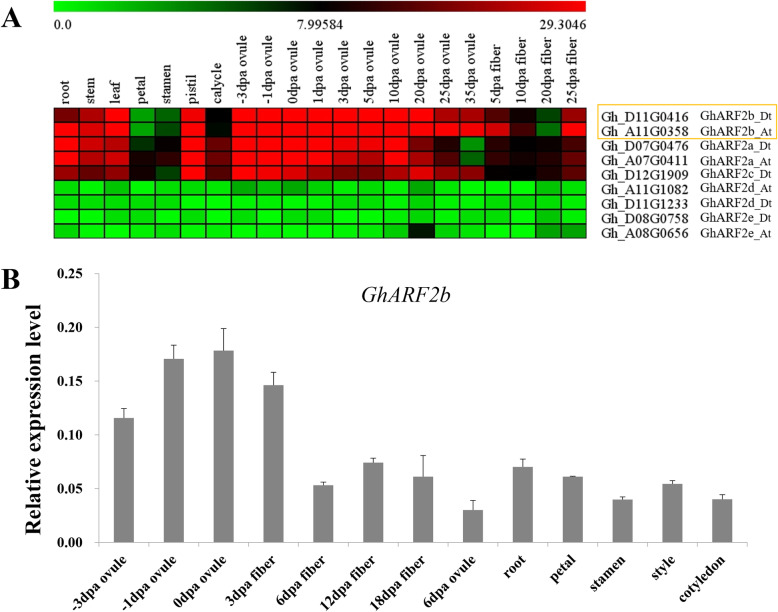

GhARF2 had a high expression pattern during fiber elongation process

There are nine ARF2 genes in G. hirsutum (GhARF2c_At not annotated), we first examined their expression profiles in different tissues in cotton (Fig. 3). Based on the RNA-seq data (Zhang et al., 2015), GhARF2a, GhARF2b and GhARF2c genes had higher expression levels in various tissues than GhARF2d or GhARF2e (Fig. 3a). Among them, in 5 dpa fiber, the expressions of GhARF2b were 1.1–37 folds to other four GhARF2 genes. Whereas in ovule (0dpa), GhARF2b showed 1.2–15 folds higher expressions than others. Thus, the transcripts of GhARF2b homoeologs (GhARF2b_At and GhARF2b_Dt) were enriched and abundant in cotton fiber and ovule cells (Fig. 3a). Subsequent quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) confirmed the expression pattern, and GhARF2b showed 3.6–9 folds higher expressions in fiber (3dpa) or ovule (0dpa) than other tissues (Fig. 3b). The highly up-regulated expression in fiber cell suggested that GhARF2b has been recruited to act primarily in cotton fiber.

Fig. 3.

Expression patterns of GhARF2 in different cotton tissues and fiber cells of different stages. a Expression profiles of nine GhARF2 genes based on the RPKM values of RNA-seq data. GhARF2b was highlighted in yellow box. b qRT-PCR analyses of GhARF2b expression across different cotton tissues. The expression is relative to GhHIS3. Error bar indicates stdev.s level of three qRT-PCR assays

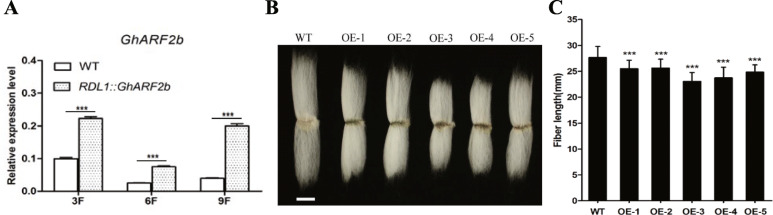

GhARF2b overexpression represses cotton fiber elongation

To test the function of GhARF2b, we constructed the vectors to over-express and down-regulate GhARF2b_Dt in G. hirsutum by using the fiber-specific GhRDL1 promoter [8, 19, 36]. The expression levels of GhARF2b in transgenic cotton were clearly elevated in the overexpression lines according to qRT-PCR analysis; for example, the GhARF2b transcript abundance was about two-fold higher in the OE-3 than in the wild-type cotton fiber cells (Fig. 4a). However, GhARF2b did not stimulate fiber cell elongation, rather, it resulted in shorter fiber (Fig. 4b, c).

Fig. 4.

GhARF2b affects fiber length and fiber related gene expression in RDL1::GhARF2b transgenic cotton. a Expression of GhARF2b in 3, 6 and 9 dpa fibers in the RDL1::GhARF2b overexpression (OE) lines compared to wild-type (WT). b Fiber phenotype of RDL1::GhARF2b and wild-type (WT) cotton cultivated in farm on shanghai, bar = 10 mm. c Statistical analysis of RDL1::GhARF2b and wild-type (WT) mature fiber length. Error bar indicates standard deviation; *** denotes significant difference from wild type (Student’s t-test, P < 0.001, n = 30)

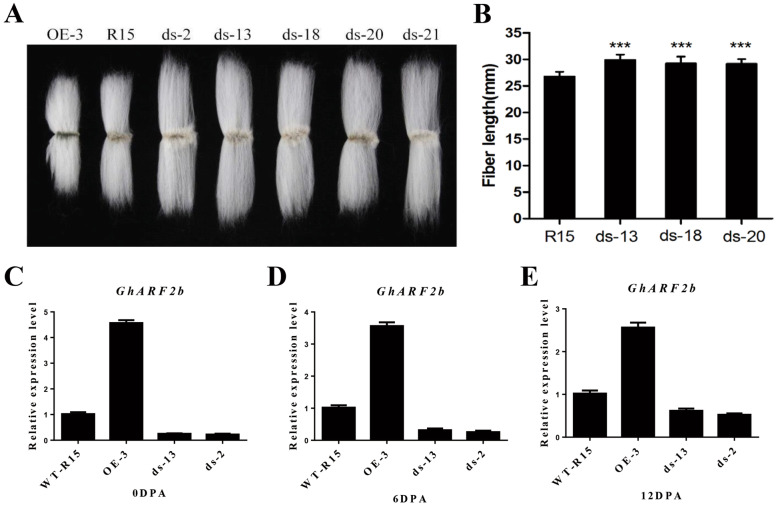

On the contrary, suppressing GhARF2b expression by RNAi resulted in longer fibers (Fig. 5a, b). The expression levels of GhARF2b in RNAi cottons in the RNAi lines were about 3 ~ 5-fold down-regulated in cotton fiber of 0DPA, 6DPA and 12DPA (Fig. 5c-e). Together, these data suggest that GhARF2b acted as a negative regulator of fiber cell elongation, at least when its expression exceeded the threshold. Alternatively, it may function in other aspects of cotton fiber development.

Fig. 5.

GhARF2b affects fiber length and gene expression in RDL1::GhARF2b RNAi transgenic cotton. a Fiber phenotype of RDL1::GhARF2b (OE), RDL1::GhARF2b RNAi (ds) and wild-type (R15) cotton cultivated in farm on shanghai, bar = 10 mm. b Statistical analysis of RDL1::GhARF2b RNAi (ds) lines and wild-type (WT) mature fiber length. Error bar indicates standard deviation; *** denotes significant difference from wild type (Student’s t-test, P < 0.001, n = 30). c Expression of GhARF2b in 0 dpa ovules in the overexpression (OE), RNAi (ds) lines compared to wild-type (WT). d Expression of GhARF2b in 6-dpa fibers in the overexpression (OE), RNAi (ds) lines compared to wild-type (WT). e Expression of GhARF2b in 12-dpa fibers in the overexpression (OE) and the RNAi (ds) lines compared to the wild-type (WT). Error bar indicates stdev.s level of three qRT-PCR assays

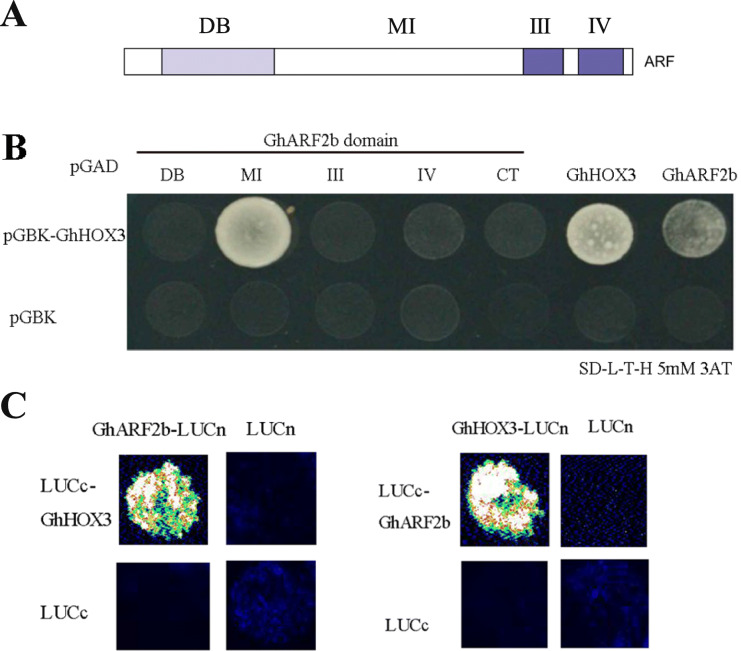

GhARF2b interacted with GhHOX3

The homeodomain-leucine zipper (HD-ZIP) transcription factor, GhHOX3, plays a determinant role in controlling cotton fiber elongation [5]. We used the yeast two-hybrid system (Y2H) to screen a cotton fiber cDNA library for GhHOX3 interacting proteins. GhARF2 was among the top five interacting factors of the target proteins. In further yeast two-hybrid assays, GhARF2b and GhARF2b middle region strongly interacted with GhHOX3 (Fig. 6a, b). We also used bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assays to confirm the interaction between GhARF2b and GhHOX3 (Fig. 6c).

Fig. 6.

Interaction of GhARF2b and GhHOX3. a Diagram of protein domains in ARF protein. b GhARF2b and GhARF2b middle region can interact with GhHOX3 in Y2H assay. The figure shows yeast grown on SD/−Leu-Trp-His with 5 mM 3AT (3-amino-1,2,4-triazole). c GhHOX3 and GhARF2b are interchangeably fused to the carboxyl- and amino-terminal of firefly luciferase (LUC, LUCc and LUCn), transiently co-expressed, and LUCc or LUCn was co-expressed with each other or with each unfused target protein as the control. Fluorescence signal intensities represent their binding activities

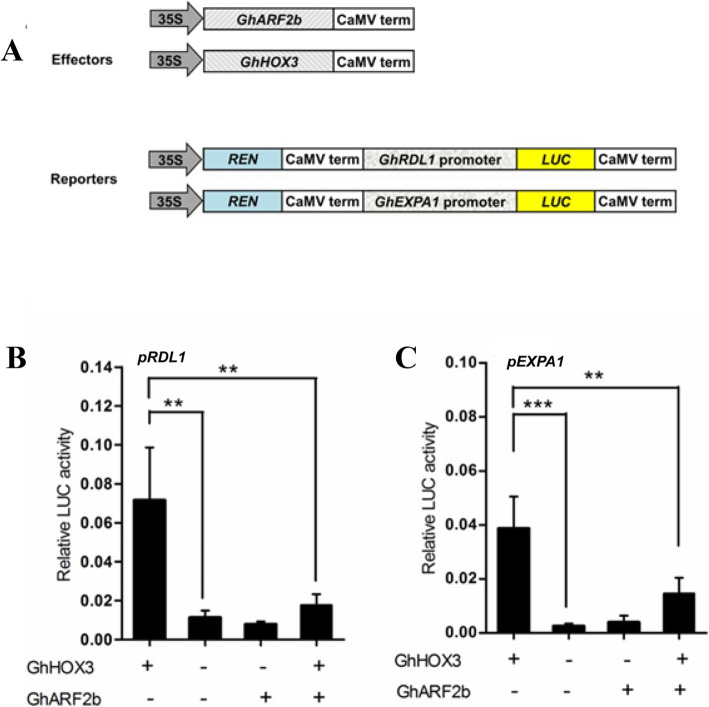

The transcriptional activities of GhHOX3 target genes were repressed by GhARF2b protein interactions

Given the fact that GhARF2b represses cotton fiber elongation, we tested the two protein interactions would affect the transcriptional activation of GhHOX3 target genes. Two cell wall protein coding genes [19, 36], GhRDL1 and GhEXPA1, are direct targets of GhHOX3 in promoting the fiber elongation [5]. We used a dual-luciferase assay system to study the effect of GhARF2b on activity of GhHOX3 protein (Fig. 7a). The level of the luciferase activity driven by GhRDL1 and GhEXPA1 promoters was significantly increased when GhHOX3 was expressed (Fig. 7b, c). In contrast, activation of GhHOX3 to GhRDL1 or GhEXPA1 promoters was significantly repressed by GhARF2b (Fig. 7b, c). These results further supported that interaction of GhARF2b with GhHOX3 results in a much lower activity of targets gene activation, thus cotton fiber elongation was disturbed.

Fig. 7.

GhARF2b represses the function of GhHOX3. a Diagram of vectors used in this assay. b GhARF2b affects the activation of GhHOX3 to GhRDL1. c GhARF2b affects the activation of GhHOX3 to GhEXPA1. Data are presented as mean ± S.D., n = 3, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, Student’s t-test)

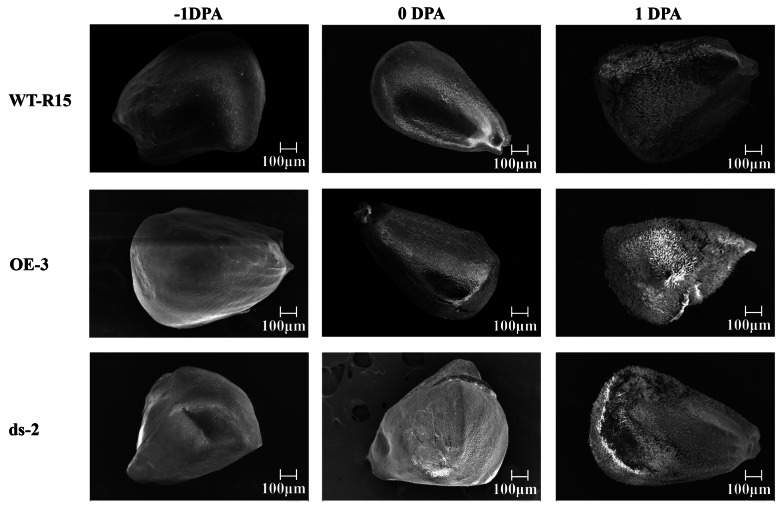

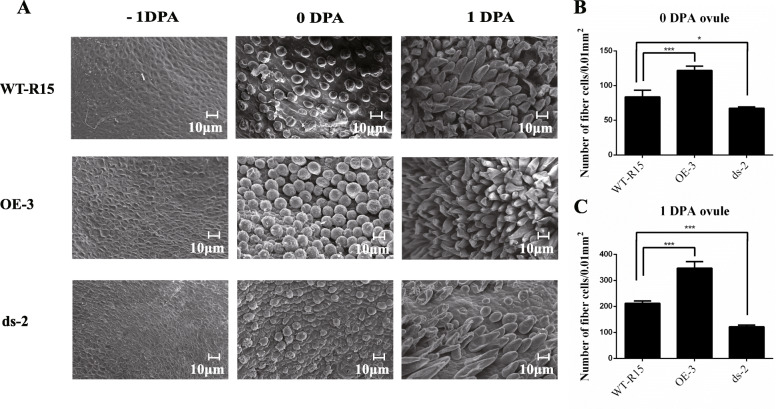

GhARF2b overexpression enhances cotton fiber initiation

Next, we examined the effects of GhARF2b up-regulation on cotton fiber initiation. The over-expression line OE-3 and RNAi line ds-2 were selected for analyses. The SEM with 60 × magnification of ovules of WT-R15, OE-3 and ds-2 collected at − 1, 0, 1 DPA were observed (Fig. 8). The cotton fiber initiation of the − 1-DPA ovules did not present differences among the three types of cottons, however, the 0- and 1-DPA ovules of OE-3 and ds-2 lines showed higher and lower densities of fiber initials compared to the wild-type control (Fig. 8). Further, we magnified the SEM views of ovules to 500–700× (Fig. 9). Obviously, at the fiber initiation stage (0, 1 DPA), the fiber initial density of the OE-3 was increased by about 1.5-fold compared with that of the wild-type, in contrast, the fiber initial density of the ds-2 line was reduced (Fig. 9a-c). These results support a role of GhARF2b in promoting cotton fiber cell initiation.

Fig. 8.

SEM images of WT-R15, OE-3 (over-expression line) and ds-2 (RNAi line) ovules at −1, 0 and 1 DPA. Bar = 100 μm [60 × magnification]

Fig. 9.

GhARF2b enhances the fiber initiation. a SEM images of WT-R15, OE-3 (over-expression line) and ds-2 (RNAi line) ovules at − 1, 0, 1 DPA. Bar = 100 μm [700 × magnification for ovules of − 1 and 0 DPA, 500 × magnification for 1-DPA ovules]. b Number of fiber cells per 0.01 mm2 of 0-DPA ovules in the overexpression (OE-3) and RNAi (ds-2) cotton lines compared to wild-type (WT-R15). Error bar indicates standard deviation; *** denotes significant difference from wild-type (Student’s t-test, P < 0.001, n = 30); * denotes significant difference from wild type (Student’s t-test, P < 0.05, n = 30). c Number of fiber cells per 0.01 mm2 of 1-DPA ovules in the overexpression (OE-3) and RNAi (ds-2) cotton lines compared to wild-type (WT-R15). Error bar indicates standard deviation; *** denotes significant difference from wild type (Student’s t-test, P < 0.001, n = 30)

Discussion

Currently, more than 20 cotton genome sequences have been assembled and released, including diploid G. raimondii [37, 38], G. herbaceum and G. arboreum [39–41] and tetraploid G. hirsutum, G. barbadense, G. tomentosum, G. mustelinum and G. darwinii [41–49]. These genome sequences provided a platform for dissecting gene functions by forward and reverse genetics and would accelerate the rate of molecular breeding in cotton. Here, based on these high-quality genome sequences, we additionally characterized 36 ARF genes in G. arboreum and 73 in G. hirsutum, adding valuable data to understanding the distribution and evolution of ARF genes in cotton plants.

After whole genome duplication, the amplified genes generally undergo the events of functional loss, or neofunctionalization or subfunctionalization [50]. In this study, we found that six GhARF genes (five from At subgenome) have experienced relatively faster positive selection compared to its diploid progenitors. Thus, duplicated genes from At and Dt subgenomes might be functionally diverged in the allotetraploid cotton after the merge of the two genomes. In addition, the GhARF genes expression profiles analyzed from the RNA-seq data showed subgenome-biased expression that might undergone functional divergence during the evolution. For instance, unequal expressions were observed in A and D-subgenome genes, including GhARF3c, GhARF16c, GhARF18a and GhARF20. These massive alterations in gene expression can cause distinct function and may just be one of the important features emerging from polyploid [8, 51]. During the evolution of allopolyploid, some duplicate gene pairs (homoeologs) are expressed unequally, as also proved in the allopolyploid cotton genome with the features of asymmetrical evolution [42]. The above results indicated that this suite of unequally expressed genes may be a fundamental feature of allopolyploids.

Previous studies showed that ARF family genes have been identified in many plant species, including 23 ARF genes in Arabidopsis thaliana [26], 25 in Oryza sativa [27], 39 in Populus trichocarpa [52], 31 in Zea mays [53], 15 in Cucumis sativus [54] and 35 in G. raimondii [32]. Auxin response factors (ARFs) are important in plant development as they play crucial roles in regulating a variety of signaling pathways [24, 25]. According to their functions, ARF proteins are divided into two classes: transcriptional activators and transcriptional repressors [24]. Many studies have revealed their regulatory roles in regulating various aspects of cellular activities [35, 55–57]. As transcriptional repressors, ARF2 was involved in the regulation of K+ uptake by repressing HAK5 transcription in Arabidopsis [34]. In addition, ARF2 is regulated by a variety of upstream factors at the transcription and protein levels, and participated in the pathways of auxin, gibberellin, oleoresin, ethylene and abscisic acid [28, 29, 31, 58].

In cotton, Zhang et al. uncovered that expression of the IAA biosynthetic gene, iaaM, can significantly increase IAA levels in the epidermis of cotton ovules at the fiber initiation stage, and increased the number of lint fibers and lint percentage in a 4-year field trial. They proved that the lint percentage of the transgenic cotton was increased in transgenic plants with a 15% increase in lint yield [59]. Han et al. found that the auxin response factor gene (GhARF3) was highly correlated with fibre quality by using the haplotype analysis and transcriptomic data. Above all, auxin signaling plays an essential role in regulating fibre development. In addition, Xiao et al. showed that G. hirsutum ARF genes promoted the trichome initiation in transgenic Arabidopsis plants [60]. They identified 56 GhARF genes in their study, including three GhARF2 genes [60]. They showed that GhARF2–1 could be exclusively expressed in trichomes, and overexpression of GhARF2–1 in Arabidopsis can enhance trichome initiation. But their study did not perform the cotton transformation to test the function of GhARF2–1 in cotton fiber cell.

Conclusions

In our study, we reported 73 GhARF genes in Gossypium hirsutum genome, including 9 GhARF2 genes. Among them, GhARF2b, was specifically higher expressed in developing fibers. Overexpression of GhARF2b represses fiber elongation, and RNAi silencing of GhARF2b promotes the fiber longer. Through yeast two-hybrid assays and the Dual-LUC experiment, GhARF2b plays a negative role in controlling cotton fiber elongation by interacting with GhHOX3. Further, GhARF2b was shown to promote the production of fiber initials, suggesting that auxin is an important player in controlling cotton fiber development. The auxin signaling pathways in developing cotton fiber cells deserve further investigation.

Methods

Identification of Gossypium species ARF factors

G. raimondii [37], G. arboreum [39], G. hirsutum [42] genome sequences were acquired from the CottonGen database [61]. We developed a Hidden Markov Model [62] profile matrix of ARF factors (Pfam ID: PF06507) via the hmmbuild program [63] with default parameters to identify Gossypium ARF transcription factor proteins. SMART conserved domain search tool [64] and Pfam databases [65] were used to identify the conserved domain.

Sequence alignment, Ka, Ks analyses and phylogenetic analyses

Gossypium ARF factor amino acids and nucleotide sequences were aligned by MAFFT software with the G-INS-i algorithm [66]. Ka, Ks and Ka/Ks values for each gene pairs between diploid and allotetraploid were calculated by DnaSP v5 [67]. The Neighbor-Joining (NJ) phylogenetic tree was drawn by MEGA 5.03 [68] by sampling 1000 bootstrap replicates based on the ARF whole protein sequences.

Gene expression analyses based on transcriptome

Raw RNA-Seq data were downloaded from the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA248163) [42], including G. hirsutum seed, root, stem, leaf, torus, petal, stamen, ovary, calyx, ovule (− 3 dpa, − 1 dpa, 0 dpa, 1 dpa, 3 dpa, 5 dpa, 10 dpa, 20 dpa, 25dpa, 35dpa) and fiber (5 dpa, 10 dpa, 20 dpa, 25dpa). The method of gene expression analyses based on transcriptome was same to our previous study [69]. Differentially expressed genes were determined based on the following criteria: more than two-fold change and p-value less than 0.05. Multiple Experiment Viewer (MeV) [70] was used to display the gene expression values.

Plant materials and growth conditions

Gossypium hirsutum cv. R15 wild type plants were obtained from Institute of Cotton Research, Shanxi Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Yuncheng, Shanxi, China. Upland cotton R15 plants and its transgenic lines were grown in a greenhouse or in a field under standard farming conditions, which is in the experimental field of Chinese Academy of Sciences in Shanghai according to relevant national approvals for biotechnology research (China, http://pg.natesc.gov.cn/sites/pg/). The greenhouse is in a controlled environment at 28 °C day/20 °C night, a 16-h light/8-h dark photoperiod. Cotton tissues, including roots, cotyledon, petal, stamen, style, ovules (− 3, − 1, 0 and 6 dpa) and fiber (3, 6, 12 and 18 dpa) were collected for expression analyses. Fibers were collected by scraping the ovule in liquid nitrogen. All these tissues were frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately after sampling and stored at − 80 °C until RNA extraction. Three times were repeated for all these treatments.

qRT-PCR analyses

All cotton samples were ground in liquid nitrogen and total RNAs of these cotton tissues were extracted using the RNAprep pure plant kit (TIANGEN, Shanghai, China) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The method of qRT-PCR analyses was same to our previous study [69]. The forward and reverse primers of specific gene for quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analyses, were designed using the Primer5 software (Additional file 3: Table S1). Analyses were performed with SYBR-Green PCR Mastermix (TaKaRa) on a cycler (Mastercycler RealPlex; Eppendorf Ltd., Shanghai, China). The internal gene was G. hirsutum histone-3 (GhHIS3, AF024716), and the 2-∆∆Ct method was used to calculate the relative amount of amplified product [71]. Relative expression levels among different organs of G. hirsutum samples were normalized by calibrating with the WT samples.

Cotton transformation and fiber length analysis

The open reading frame (ORF) of GhARF2b was PCR-amplified from a G. hirsutum cv R15 fiber cDNA library with PrimeSTAR HS DNA polymerase (Takara Biomedical Technology Co. Ltd., Beijing, China) and inserted into the pCAMBIA2301 vector to construct RDL1::GhARF2b. For 35S::dsGhARF2b, sense and antisense: GhARF2b fragments, separated by a 120-bp intron of the RTM1 gene from A. thaliana, were cloned into pCAMBIA2301. Primers used in this investigation are listed in Additional file 3: Table S1. The binary constructs were transferred into Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Cotton transformation was conducted as reported in Shangguan et al. [72]. Transgenic cotton plants were grown in glasshouse or field. β-glucuronidase (GUS) staining and PCR amplification were performed to identify the transgenic lines of T0 and subsequent generations. Thirty seeds from each plant were harvested to statistics fiber length.

Yeast two-hybrid assay

Yeast two-hybrid analysis were carried out using the Matchmaker GAL4 Two-Hybrid System as performed previously [5]. Briefly, for the yeast two-hybrid assays, the full-length ORF of GhHOX3 inserted into pGBKT7 (Clontech) and GhARF2b or GhARF2b different domains into pGADT7 (Clontech). Plasmids were co-transferred into yeast strain AH109 by the LiCl-PEG method, and SD/−Leu/−Trp/−His selective plates containing 5 mM 3-AT (3-amino-1,2,4,-triazole) were used to detect the protein-protein interactions. pGADT7 and pGBKT7 empty vectors were used as controls. Three biological duplications for each transformation were performed.

BiFC and dual-luciferase (dual-LUC) assays

We performed the BiFC assays following previous reports [73, 74]. In summary, CDSs of GhARF2b and GhHOX3 were amplified and cloned into JW771 and JW772 vectors, respectively. Each gene was fused to the carboxyl-terminal half (cLUC-GhARF2b/GhHOX3) and the amino-terminal half (GhARF2b/GhHOX3-nLUC) of luciferase (LUC), respectively. cLUC and nLUC were used as controls. Assays were finished as described [5, 75].

The Dual-LUC assay was performed as reported [5, 76]. Briefly, the promoters containing intact L1-boxes of GhRDL1 and GhEXPA1 were inserted into pGreen-LUC vector with a firefly LUC reporter gene. Then, the constructs were transferred into Agrobacterium tumefaciens cell with a co-suppression repressor plasmid pSoup-P19. Transient transformation was conducted by infiltrating the A. tumefaciens cells into N. benthamiana leaves. The total protein was extracted from the infected area after 3 days. The Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) was used to detect the fluorescent values of LUC and REN with a luminometer (BG-1, GEM Biomedical Inc.). The value of LUC was normalized to that of REN. Three biological replicates were measured for each experiment.

Microscope observation

Images were generated with an optical microscope (BX51, Olympus). For scanning electron microscope images, cotton ovules (− 1, 0, 1DPA) were attached with colloidal graphite to a copper stub, frozen under vacuum and visualized with a scanning electron microscope (JSM-6360LV, JEOL).

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Multiple alignment of GrARF2 (Gossypium raimondii ARF2) and AtARF2 protein sequences.

Additional file 2: Figure S2. Expression patterns of ARF genes in G. hirsutum based on RNA-seq data. FPKM represents fragments per kilobase of exon model per million mapped reads. DPA, days post-anthesis.s.

Additional file 3: Table S1. List of forward and reverse primers used for this study.

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Tian-Zhen Zhang for providing the RNA-seq data and calculating the RPKM values and Prof. Xiao-Ya Chen participating in discussion and revising the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- ARFs

Auxin response factors

- Dpa

Days post anthesis

- FPKM

Fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped fragments

- G. arboreum

Gossypium arboreum

- G. hirsutum

Gossypium hirsutum

- G. raimondii

Gossypium raimondii

- WT

wild type

- OE

Overexpression

- ds

RNAi

- qRT-PCR

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

Authors’ contributions

ZWC, XFZ and LJW designed the research. ZWC, XFZ, JFC, CCH, XL and YGZ performed the experiments. XFZ, ZSZ, XXSG, LJW and ZWC contributed materials and analyzed data. ZWC wrote and revised the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work reported in this publication was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China through the Awards Nos. 31690092, 31571251, 31788103, the National Key R&D Program of China (2016YFD0100500) and the Ministry of Agriculture of China (2016ZX08005–003), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation through the Awards Nos. 2017 M621546 and 2018 T110411. The funding bodies did not participate in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The genome sequences of three cotton species and the genome annotation gff3 file were downloaded from the CottonGen database (https://www.cottongen.org/data/download) [59]. Raw RNA-Seq data for G. hirsutum seed, root, stem, leaf, torus, petal, stamen, ovary, calyx, ovule and fiber were downloaded from the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA248163) (NCBI Sequence Read Archive SRR1695173, SRR1695174, SRR1695175, SRR1695177, SRR1695178, SRR1695179, SRR1695181, SRR1695182, SRR1695183, SRR1695184, SRR1695185, SRR1695191, SRR1695192, SRR1695193,SRR1695194, SRR1768504, SRR1768505, SRR1768506, SRR1768507, SRR1768508, SRR1768509, SRR1768510, SRR1768511, SRR1768512, SRR1768513, SRR1768514, SRR1768515, SRR1768516, SRR1768517, SRR1768518 and SRR1768519) [30]. The G. hirsutum histone-3 (GhHIS3, AF024716) gene was downloaded from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database, which were used as internal references. The conserved domain of ARF transcription factors (Pfam ID: PF06507) was downloaded from the Pfam databases (http://pfam.xfam.org/family/PF06507#tabview=tab3). All other data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its Additional files.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Xiufang Zhang, Email: xfzhang1990@163.com.

Junfeng Cao, Email: caojunfeng@sibs.ac.cn.

Chaochen Huang, Email: jane525265016@sina.com.

Zishou Zheng, Email: zhengzishou@sippe.ac.cn.

Xia Liu, Email: liuxiaxj@esquel.com.

Xiaoxia Shangguan, Email: sgxx@sibs.ac.cn.

Lingjian Wang, Email: ljwang@sibs.ac.cn.

Yugao Zhang, Email: zhangyu@esquel.com.

Zhiwen Chen, Email: b1301031@cau.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Schell J. Cotton carrying the recombinant insect poison Bt toxin: no case to doubt the benefits of plant biotechnology. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1997;8(2):235–236. doi: 10.1016/S0958-1669(97)80108-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim HJ, Triplett BA. Cotton fiber growth in planta and in vitro. Models for plant cell elongation and cell wall biogenesis. Plant Physiol. 2001;127(4):1361–1366. doi: 10.1104/pp.010724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Graves DA, Stewart JM. Chronology of the differentiation of cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) fiber cells. Planta. 1988;175(2):254–258. doi: 10.1007/BF00392435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fang DD, Naoumkina M, Kim HJ. Unraveling cotton Fiber development using Fiber mutants in the post-genomic era. Crop Sci. 2018;58(6):2214–2228. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2018.03.0184. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shan CM, Shangguan XX, Zhao B, Zhang XF, Chao LM, Yang CQ, Wang LJ, Zhu HY, Zeng YD, Guo WZ, et al. Control of cotton fibre elongation by a homeodomain transcription factor GhHOX3. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5519. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guan XY, Li QJ, Shan CM, Wang S, Mao YB, Wang LJ, Chen XY. The HD-zip IV gene GaHOX1 from cotton is a functional homologue of the Arabidopsis GLABRA2. Physiol Plant. 2008;134(1):174–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2008.01115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walford SA, Wu Y, Llewellyn DJ, Dennis ES. Epidermal cell differentiation in cotton mediated by the homeodomain leucine zipper gene, GhHD-1. Plant J. 2012;71(3):464–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.05003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao B, Cao JF, Hu GJ, Chen ZW, Wang LY, Shangguan XX, Wang LJ, Mao YB, Zhang TZ, Wendel JF, et al. Core cis-element variation confers subgenome-biased expression of a transcription factor that functions in cotton fiber elongation. New Phytol. 2018;218(3):1061–1075. doi: 10.1111/nph.15063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gong SY, Huang GQ, Sun X, Qin LX, Li Y, Zhou L, Li XB. Cotton KNL1, encoding a class II KNOX transcription factor, is involved in regulation of fibre development. J Exp Bot. 2014;65(15):4133–4147. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Z, Ruan YL, Zhou N, Wang F, Guan X, Fang L, Shang X, Guo W, Zhu S, Zhang T. Suppressing a putative sterol carrier gene reduces Plasmodesmal permeability and activates sucrose transporter genes during cotton Fiber elongation. Plant Cell. 2017;29(8):2027–2046. doi: 10.1105/tpc.17.00358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wan Q, Guan X, Yang N, Wu H, Pan M, Liu B, Fang L, Yang S, Hu Y, Ye W, et al. Small interfering RNAs from bidirectional transcripts of GhMML3_A12 regulate cotton fiber development. New Phytol. 2016;210(4):1298–1310. doi: 10.1111/nph.13860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu H, Tian Y, Wan Q, Fang L, Guan X, Chen J, Hu Y, Ye W, Zhang H, Guo W, et al. Genetics and evolution of MIXTA genes regulating cotton lint fiber development. New Phytol. 2018;217(2):883–895. doi: 10.1111/nph.14844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Machado A, Wu Y, Yang Y, Llewellyn DJ, Dennis ES. The MYB transcription factor GhMYB25 regulates early fibre and trichome development. Plant J. 2009;59(1):52–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walford SA, Wu Y, Llewellyn DJ, Dennis ES. GhMYB25-like: a key factor in early cotton fibre development. Plant J. 2011;65(5):785–797. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang J, Huang GQ, Zou D, Yan JQ, Li Y, Hu S, Li XB. The cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) NAC transcription factor (FSN1) as a positive regulator participates in controlling secondary cell wall biosynthesis and modification of fibers. New Phytol. 2018;217(2):625–640. doi: 10.1111/nph.14864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han LB, Li YB, Wang HY, Wu XM, Li CL, Luo M, Wu SJ, Kong ZS, Pei Y, Jiao GL, et al. The dual functions of WLIM1a in cell elongation and secondary wall formation in developing cotton fibers. Plant Cell. 2013;25(11):4421–4438. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.116970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ruan YL, Llewellyn DJ, Furbank RT. Suppression of sucrose synthase gene expression represses cotton fiber cell initiation, elongation, and seed development. Plant Cell. 2003;15(4):952–964. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li XB, Fan XP, Wang XL, Cai L, Yang WC. The cotton ACTIN1 gene is functionally expressed in fibers and participates in fiber elongation. Plant Cell. 2005;17(3):859–875. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.029629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu B, Gou JY, Li FG, Shangguan XX, Zhao B, Yang CQ, Wang LJ, Yuan S, Liu CJ, Chen XY. A cotton BURP domain protein interacts with alpha-expansin and their co-expression promotes plant growth and fruit production. Mol Plant. 2013;6(3):945–958. doi: 10.1093/mp/sss112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shi YH, Zhu SW, Mao XZ, Feng JX, Qin YM, Zhang L, Cheng J, Wei LP, Wang ZY, Zhu YX. Transcriptome profiling, molecular biological, and physiological studies reveal a major role for ethylene in cotton fiber cell elongation. Plant Cell. 2006;18(3):651–664. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.040303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang GQ, Gong SY, Xu WL, Li W, Li P, Zhang CJ, Li DD, Zheng Y, Li FG, Li XB. A fasciclin-like arabinogalactan protein, GhFLA1, is involved in fiber initiation and elongation of cotton. Plant Physiol. 2013;161(3):1278–1290. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.203760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cao JF, Zhao B, Huang CC, Chen ZW, Zhao T, Liu HR, Hu GJ, Shangguan XX, Shan CM, Wang LJ, et al. The miR319-targeted GhTCP4 promotes the transition from cell elongation to wall thickening in cotton fiber. Mol Plant. 2020;13(7):1063–1077. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu Y, Wu S, Nowak J, Wang G, Han L, Feng Z, Mendrinna A, Ma Y, Wang H, Zhang X, et al. Live-cell imaging of the cytoskeleton in elongating cotton fibres. Nat Plants. 2019;5(5):498–504. doi: 10.1038/s41477-019-0418-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guilfoyle TJ, Hagen G. Auxin response factors. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2007;10(5):453–460. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tiwari SB, Hagen G, Guilfoyle T. The roles of auxin response factor domains in auxin-responsive transcription. Plant Cell. 2003;15(2):533–543. doi: 10.1105/tpc.008417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okushima Y, Overvoorde PJ, Arima K, Alonso JM, Chan A, Chang C, Ecker JR, Hughes B, Lui A, Nguyen D, et al. Functional genomic analysis of the AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR gene family members in Arabidopsis thaliana: unique and overlapping functions of ARF7 and ARF19. Plant Cell. 2005;17(2):444–463. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.028316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang DK, Pei KM, Fu YP, Sun ZX, Li SJ, Liu HQ, Tang K, Han B, Tao YZ. Genome-wide analysis of the auxin response factors (ARF) gene family in rice (Oryza sativa) Gene. 2007;394(1–2):13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vert G, Walcher CL, Chory J, Nemhauser JL. Integration of auxin and brassinosteroid pathways by Auxin response factor 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(28):9829–9834. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803996105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang L, Hua DP, He JN, Duan Y, Chen ZZ, Hong XH, Gong ZZ. Auxin response factor2 (ARF2) and its regulated homeodomain gene hb33 mediate abscisic acid response in arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 2011;7(7):e1002172. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schruff MC, Spielman M, Tiwari S, Adams S, Fenby N, Scott RJ. The AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR 2 gene of Arabidopsis links auxin signalling, cell division, and the size of seeds and other organs. Development. 2006;133(2):251–261. doi: 10.1242/dev.02194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Breitel DA, Chappell-Maor L, Meir S, Panizel I, Puig CP, Hao Y, Yifhar T, Yasuor H, Zouine M, Bouzayen M, et al. AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR 2 intersects hormonal signals in the regulation of tomato fruit ripening. PLoS Genet. 2016;12(3):e1005903. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun RR, Wang KB, Guo TL, Jones DC, Cobb J, Zhang BH, Wang QL. Genome-wide identification of auxin response factor (ARF) genes and its tissue-specific prominent expression in Gossypium raimondii. Function Integr Genom. 2015;15(4):481–493. doi: 10.1007/s10142-015-0437-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lim PO, Lee IC, Kim J, Kim HJ, Ryu JS, Woo HR, Nam HG. Auxin response factor 2 (ARF2) plays a major role in regulating auxin-mediated leaf longevity. J Exp Bot. 2010;61(5):1419–1430. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao S, Zhang ML, Ma TL, Wang Y. Phosphorylation of ARF2 relieves its repression of transcription of the K+ transporter gene HAK5 in response to low potassium stress. Plant Cell. 2016;28(12):3005–3019. doi: 10.1105/tpc.16.00684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Okushima Y, Mitina I, Quach HL, Theologis A. AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR 2 (ARF2): a pleiotropic developmental regulator. Plant J Cell Mol Biol. 2005;43(1):29–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang S, Wang JW, Yu N, Li CH, Luo B, Gou JY, Wang LJ, Chen XY. Control of plant trichome development by a cotton fiber MYB gene. Plant Cell. 2004;16(9):2323–2334. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.024844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paterson AH, Wendel JF, Gundlach H, Guo H, Jenkins J, Jin D, Llewellyn D, Showmaker KC, Shu S, Udall J, et al. Repeated polyploidization of Gossypium genomes and the evolution of spinnable cotton fibres. Nature. 2012;492(7429):423–427. doi: 10.1038/nature11798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang K, Wang Z, Li F, Ye W, Wang J, Song G, Yue Z, Cong L, Shang H, Zhu S, et al. The draft genome of a diploid cotton Gossypium raimondii. Nat Genet. 2012;44(10):1098–1103. doi: 10.1038/ng.2371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li F, Fan G, Wang K, Sun F, Yuan Y, Song G, Li Q, Ma Z, Lu C, Zou C, et al. Genome sequence of the cultivated cotton Gossypium arboreum. Nat Genet. 2014;46(6):567–572. doi: 10.1038/ng.2987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Du X, Huang G, He S, Yang Z, Sun G, Ma X, Li N, Zhang X, Sun J, Liu M, et al. Resequencing of 243 diploid cotton accessions based on an updated a genome identifies the genetic basis of key agronomic traits. Nat Genet. 2018;50(6):796–802. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0116-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang G, Wu Z, Percy RG, Bai M, Li Y, Frelichowski JE, Hu J, Wang K, Yu JZ, Zhu Y. Genome sequence of Gossypium herbaceum and genome updates of Gossypium arboreum and Gossypium hirsutum provide insights into cotton A-genome evolution. Nat Genet. 2020;52(5):516–524. doi: 10.1038/s41588-020-0607-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang T, Hu Y, Jiang W, Fang L, Guan X, Chen J, Zhang J, Saski CA, Scheffler BE, Stelly DM, et al. Sequencing of allotetraploid cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L. acc. TM-1) provides a resource for fiber improvement. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33(5):531–537. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen ZJ, Sreedasyam A, Ando A, Song Q, De Santiago LM, Hulse-Kemp AM, Ding M, Ye W, Kirkbride RC, Jenkins J, et al. Genomic diversifications of five Gossypium allopolyploid species and their impact on cotton improvement. Nat Genet. 2020;52(5):525–533. doi: 10.1038/s41588-020-0614-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li F, Fan G, Lu C, Xiao G, Zou C, Kohel RJ, Ma Z, Shang H, Ma X, Wu J, et al. Genome sequence of cultivated upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum TM-1) provides insights into genome evolution. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33(5):524–530. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu X, Zhao B, Zheng HJ, Hu Y, Lu G, Yang CQ, Chen JD, Chen JJ, Chen DY, Zhang L, et al. Gossypium barbadense genome sequence provides insight into the evolution of extra-long staple fiber and specialized metabolites. Sci Rep. 2015;5:14139. doi: 10.1038/srep14139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yuan D, Tang Z, Wang M, Gao W, Tu L, Jin X, Chen L, He Y, Zhang L, Zhu L, et al. The genome sequence of Sea-Island cotton (Gossypium barbadense) provides insights into the allopolyploidization and development of superior spinnable fibres. Sci Rep. 2015;5:17662. doi: 10.1038/srep17662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang M, Tu L, Yuan D, Zhu D, Shen C, Li J, Liu F, Pei L, Wang P, Zhao G, et al. Reference genome sequences of two cultivated allotetraploid cottons, Gossypium hirsutum and Gossypium barbadense. Nat Genet. 2019;51(2):224–229. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0282-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hu Y, Chen J, Fang L, Zhang Z, Ma W, Niu Y, Ju L, Deng J, Zhao T, Lian J, et al. Gossypium barbadense and Gossypium hirsutum genomes provide insights into the origin and evolution of allotetraploid cotton. Nat Genet. 2019;51(4):739–748. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0371-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang Z, Ge X, Yang Z, Qin W, Sun G, Wang Z, Li Z, Liu J, Wu J, Wang Y, et al. Extensive intraspecific gene order and gene structural variations in upland cotton cultivars. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):2989. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10820-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wendel JF. The wondrous cycles of polyploidy in plants. Am J Bot. 2015;102(11):1753–1756. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1500320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen ZW, Cao JF, Zhang XF, Shangguan XX, Mao YB, Wang LJ, Chen XY. Cotton genome: challenge into the polyploidy. Sci Bull. 2017;62(24):1622–1623. doi: 10.1016/j.scib.2017.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kalluri UC, Difazio SP, Brunner AM, Tuskan GA. Genome-wide analysis of aux/IAA and ARF gene families in Populus trichocarpa. BMC Plant Biol. 2007;7:59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-7-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xing H, Pudake RN, Guo G, Xing G, Hu Z, Zhang Y, Sun Q, Ni Z. Genome-wide identification and expression profiling of auxin response factor (ARF) gene family in maize. BMC Genomics. 2011;12(1):178. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu SQ, Hu LF. Genome-wide analysis of the auxin response factor gene family in cucumber. Genet Mol Res. 2013;12(4):4317–4331. doi: 10.4238/2013.April.2.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hardtke CS, Berleth T. The Arabidopsis gene MONOPTEROS encodes a transcription factor mediating embryo axis formation and vascular development. EMBO J. 1998;17(5):1405–1411. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.5.1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nemhauser JL, Feldman LJ, Zambryski PC. Auxin and ETTIN in Arabidopsis gynoecium morphogenesis. Development. 2000;127(18):3877–3888. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.18.3877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ellis CM, Nagpal P, Young JC, Hagen G, Guilfoyle TJ, Reed JW. AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR1 and AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR2 regulate senescence and floral organ abscission in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development. 2005;132(20):4563–4574. doi: 10.1242/dev.02012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Richter R, Behringer C, Zourelidou M, Schwechheimer C. Convergence of auxin and gibberellin signaling on the regulation of the GATA transcription factors GNC and GNL in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(32):13192–13197. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1304250110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang M, Zheng X, Song S, Zeng Q, Hou L, Li D, Zhao J, Wei Y, Li X, Luo M, et al. Spatiotemporal manipulation of auxin biosynthesis in cotton ovule epidermal cells enhances fiber yield and quality. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29(5):453–458. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xiao G, He P, Zhao P, Liu H, Zhang L, Pang C, Yu J. Genome-wide identification of the GhARF gene family reveals that GhARF2 and GhARF18 are involved in cotton fibre cell initiation. J Exp Bot. 2018;69(18):4323–4337. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ery219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yu J, Jung S, Cheng CH, Ficklin SP, Lee T, Zheng P, Jones D, Percy RG, Main D. CottonGen: a genomics, genetics and breeding database for cotton research. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(Database issue):1229–1236. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wong DC, Schlechter R, Vannozzi A, Holl J, Hmmam I, Bogs J, Tornielli GB, Castellarin SD, Matus JT. A systems-oriented analysis of the grapevine R2R3-MYB transcription factor family uncovers new insights into the regulation of stilbene accumulation. DNA Res. 2016;23:451–466. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsw028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mistry J, Finn RD, Eddy SR, Bateman A, Punta M. Challenges in homology search: HMMER3 and convergent evolution of coiled-coil regions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(12):e121. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Letunic I, Bork P. 20 years of the SMART protein domain annotation resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(D1):D493–D496. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Finn RD, Coggill P, Eberhardt RY, Eddy SR, Mistry J, Mitchell AL, Potter SC, Punta M, Qureshi M, Sangrador-Vegas A, et al. The Pfam protein families database: towards a more sustainable future. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(D1):D279–D285. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Katoh K, Standley DM. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30(4):772. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Librado P, Rozas J. DnaSP v5: a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(11):1451–1452. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28(10):2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cao J-F, Huang J-Q, Liu X, Huang C-C, Zheng Z-S, Zhang X-F, Shangguan X-X, Wang L-J, Zhang Y-G, Wendel JF, et al. Genome-wide characterization of the GRF family and their roles in response to salt stress in Gossypium. BMC Genomics. 2020;21(1):575. doi: 10.1186/s12864-020-06986-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Saeed AI, Sharov V, White J, Li J, Liang W, Bhagabati N, Braisted J, Klapa M, Currier T, Thiagarajan M, et al. TM4: a free, open-source system for microarray data management and analysis. Biotechniques. 2003;34(2):374–378. doi: 10.2144/03342mt01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(T) (−Delta Delta C) method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shangguan XX, Xu B, Yu ZX, Wang LJ, Chen XY. Promoter of a cotton fibre MYB gene functional in trichomes of Arabidopsis and glandular trichomes of tobacco. J Exp Bot. 2008;59(13):3533–3542. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gou JY, Felippes FF, Liu CJ, Weigel D, Wang JW. Negative regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis by a miR156-targeted SPL transcription factor. Plant Cell. 2011;23(4):1512–1522. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.084525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chen HM, Zou Y, Shang YL, Lin HQ, Wang YJ, Cai R, Tang XY, Zhou JM. Firefly luciferase complementation imaging assay for protein-protein interactions in plants. Plant Physiol. 2008;146(2):368–376. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.111740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Papp I, Mette MF, Aufsatz W, Daxinger L, Schauer SE, Ray A, van der Winden J, Matzke M, Matzke AJ. Evidence for nuclear processing of plant micro RNA and short interfering RNA precursors. Plant Physiol. 2003;132(3):1382–1390. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.021980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Liu H, Yu X, Li K, Klejnot J, Yang H, Lisiero D, Lin C. Photoexcited CRY2 interacts with CIB1 to regulate transcription and floral initiation in Arabidopsis. Science. 2008;322(5907):1535–1539. doi: 10.1126/science.1163927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Multiple alignment of GrARF2 (Gossypium raimondii ARF2) and AtARF2 protein sequences.

Additional file 2: Figure S2. Expression patterns of ARF genes in G. hirsutum based on RNA-seq data. FPKM represents fragments per kilobase of exon model per million mapped reads. DPA, days post-anthesis.s.

Additional file 3: Table S1. List of forward and reverse primers used for this study.

Data Availability Statement

The genome sequences of three cotton species and the genome annotation gff3 file were downloaded from the CottonGen database (https://www.cottongen.org/data/download) [59]. Raw RNA-Seq data for G. hirsutum seed, root, stem, leaf, torus, petal, stamen, ovary, calyx, ovule and fiber were downloaded from the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA248163) (NCBI Sequence Read Archive SRR1695173, SRR1695174, SRR1695175, SRR1695177, SRR1695178, SRR1695179, SRR1695181, SRR1695182, SRR1695183, SRR1695184, SRR1695185, SRR1695191, SRR1695192, SRR1695193,SRR1695194, SRR1768504, SRR1768505, SRR1768506, SRR1768507, SRR1768508, SRR1768509, SRR1768510, SRR1768511, SRR1768512, SRR1768513, SRR1768514, SRR1768515, SRR1768516, SRR1768517, SRR1768518 and SRR1768519) [30]. The G. hirsutum histone-3 (GhHIS3, AF024716) gene was downloaded from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database, which were used as internal references. The conserved domain of ARF transcription factors (Pfam ID: PF06507) was downloaded from the Pfam databases (http://pfam.xfam.org/family/PF06507#tabview=tab3). All other data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its Additional files.