Abstract

Context:

Traffic noise may contribute to depression and anxiety through higher noise annoyance (NA). However, little is known about noise sensitivity (NS) and mental health status as contextual factors.

Objective:

We tested three hypotheses: (1) Traffic noise is associated with mental ill-health through higher NA; (2) Mental ill-health and NS moderate the association between traffic noise and NA; and (3) NS moderates the indirect effect of traffic noise on mental ill-health.

Subjects and Methods:

We used a convenience sample of 437 undergraduate students from the Medical University in Plovdiv, Bulgaria (mean age 21 years; 35% male). Residential road traffic noise (LAeq; day equivalent noise level) was calculated using a land use regression model. Depression and anxiety symptoms were measured with the Patient Health Questionnaire 9-item (PHQ-9) and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7) scale, respectively. NA was measured using a 5-point verbal scale. The Noise Sensitivity Scale Short Form (NSS-SF) was used to measure NS. To investigate how these variables intertwine, we conducted mediation, moderation and moderated mediation analyses.

Results:

LAeq was indirectly associated with higher PHQ-9/GAD-7 scores through higher NA, but only in the low NS group. The relationship between LAeq and NA was stronger in students reporting depression/anxiety. While high NS was associated with high NA even at low noise levels, LAeq contributed to NA only in students low on NS.

Conclusions:

We found complex conditional relationships between traffic noise, annoyance and mental ill-health. Understanding respective vulnerability profiles within the community could aid noise policy and increase efficacy of interventions.

Keywords: Anxiety, depression, noise exposure, noise perception, perceived control psychoacoustics

INTRODUCTION

Depression and anxiety are common mental disorders associated with a considerable social and economic burden.[1,2] While they can partially be explained by genetic factors and heritability, evidence suggests that contextual factors can modify brain plasticity and function.[3,4] For example, adverse psycho-physiological reactions can be enhanced by urban living.[5,6] Traffic noise is a ubiquitous stressor among urban dwellers,[7] which triggers neuroendocrine stress and stimulates cortical structures involved in processing of auditory information.[8,9,10] Such chronic stress can take a toll on mental health via functional and structural alterations in the brain.[11] Noise annoyance (NA), a multifaceted construct representing negative evaluation of living conditions with respect to noise,[12,13] has been hypothesized to mediate mental health effects of traffic noise.[14] Traffic noise may also have a negative effect through NA as a constraint on restorative experiences in the residential environment.[15]

As a complex psychological construct, NA is contingent not only on noise exposure but also on various non-acoustic factors (cognitive, attitudinal, and behavioural).[12] Noise sensitivity (NS), in particular, has been conceptualized as a psycho-physiological internal state of an individual that increases the degree of reactivity to noise in general.[16,17] Although evidence of its correlations with personality characteristics is mixed,[17,18] some authors have linked it to neuroticism and negative affect.[16,18] Noise sensitive individuals have difficulty adapting to noise because they pay more attention to sounds perceived as threatening and beyond their control.[19] Therefore, NS may act as a moderator of the relationship between noise and NA, with highly sensitive individuals being more susceptible.[20,21,22] Evidence suggests that NS may also be a vulnerability factor for psychological ill-health of itself.[22,23] Likewise, people experiencing depression and/or anxiety may be particularly vulnerable to noise because of over-vigilance and perceived helplessness against aversive environmental stimuli.[24,25,26] Fyhri and Klaeboe[27] speculated that individual vulnerability to noise is reflected both in ill-health and in being sensitive to noise.

It is conceivable that highly noise sensitive individuals would already have high baseline level of NA, therefore, noise exposure may play a lesser role compared with individuals with low NS.[28] There is also growing recognition that mental health may be a context in which the effects of noise unfold, rather than simply an outcome of noise exposure.[29] This motivates reification of mental health as another moderator of the traffic noise − NA relationship. However, few studies have investigated these hypothesised contingencies.

Here we aim to investigate the conditional processes linking traffic noise exposure, NA, NS, and ill-mental. We test three complementary hypotheses: first, that traffic noise is associated with poor mental health through higher NA; second, that mental health and NS moderate the association between traffic noise and NA; and third, that NS moderates the indirect effect of traffic noise on mental health. To that end, we use a sample of undergraduate students whose occupation is characterized by high levels of attentional demands and stressors such as time pressure and deadlines that make them susceptible to impaired mental health.[30]

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Study design and sampling

Data were collected in October 2018 in Plovdiv, the second largest city in Bulgaria. We used a convenience sample of undergraduate students from all faculties of the Medical University in the city. They were recruited during classes and invited to participate in a survey on residential surroundings and quality of life. We invited students with different ethnic and cultural background and program enrolment to ensure sufficient variation in the data. To be included, they had to be aged from 18 to 35 years and, to ensure that they were familiar with their neighbourhood environment, had to be resident in their current home for at least one year prior to the study. Students who had lived in their home for less than a year, who did not report their address or were unable to clearly understand the questionnaire (e.g., foreign students whose English was not good) were excluded.[31]

Out of the 620 invited students, 581 agreed to take part in the survey (94%). After excluding 52 students who did not finish the questionnaire or provided insufficient residential data, and 92 students for whom traffic noise exposure could not be calculated because they did not live in the city of Plovdiv, 437 were retained for the main analyses (70%).

The survey included questions about sociodemographic factors, residential environment, noise perception, mental health, and the student’s current living address, which was needed for subsequent assignment of traffic noise level and other geographic variables. Questions about psychological states and evaluative judgements referred to the last month. The survey was administered in two languages − an English version for foreign students and a Bulgarian version for domestic students. Members of the research group were present so that participants had the opportunity to give feedback and receive clarifications about each question.

The design and conduct of the study accorded with the general principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants signed informed consent forms agreeing that their personal information would be processed and stored according to the General Data Protection Regulation in the European Union. There were no incentives provided to students who consented to participate and no penalties for those who chose not to do so.

Traffic noise assessment

Residential noise (LAeq; day equivalent noise level) was calculated by applying a land use regression (LUR) model. The LUR was developed for an earlier study within the same student population and was based on the 2016 noise measurement campaign in Plovdiv. Measurements were conducted over the 12-hour period from 07.00 to 19.00 hours, according to the ISO 1996-2:1987. Predictor variables were derived from the Geographical Information System. The final LUR has an adjusted R 2 of 0.72 and leave-one-out cross validation R 2 of 0.65. Further details are reported elsewhere.[32]

Assessment of mental ill-health

Severity of depression and anxiety were measured with two screening instruments. The Patient Health Questionnaire 9-item (PHQ-9) taps symptoms of depression like anhedonia, hopelessness, sleep problems, fatigue, appetite changes, and thoughts of death. The items are based on the diagnostic criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders − IV for major depressive disorder. Response options ranged from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day) during the past two weeks.[33] Scores (sum of the item responses) could range from 0 to 27. Cronbach’s alpha in our sample was 0.77.

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7) scale was designed to assess how often during the past two weeks the person was bothered by common symptoms of anxiety, such as feeling nervous, worrying too much, having trouble relaxing, becoming easily annoyed, and feeling afraid that something bad might happen.[34] Response options ranged from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). Scores (sum of the item responses) could range from 0 to 21. Cronbach’s alpha in our sample was 0.87.

The PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scales were modelled as continuous variables for a more nuanced assessment of symptoms severity, and as dichotomized scores (cut-off ≥ 10) to define moderate depression[35] and generalized anxiety disorder.[36]

Noise annoyance

NA was measured using a single item mimicking the phrasing and response options of the 5-point verbal International Commission on Biological Effects of Noise (ICBEN) NA scale.[37] The question was formulated thus: “How much does road traffic noise in your neighbourhood bother, disturb, or annoy you?”. Possible responses were: “0 = Not at all”, “1 = Slightly”, “2 = Moderately”, “3 = Very”, and to “4 = Extremely”. Our approach differed from the standard ICBEN instructions in that we considered NA in the living environment, not just at home. This formulation was expected to better represent the potential of noise to decrease neighbourhood restorative quality.[15] NA was modelled as a continuous variable with higher scores indicating higher NA.

Noise sensitivity

The Noise Sensitivity Scale Short Form (NSS-SF) was used to measure NS.[38] The NSS-SF was developed as a more practical form of the classical Weinstein noise sensitivity scale,[39] and later translated to Bulgarian (BNSS-SF).[40] It has five items expressing attitudes toward noise in general and emotional reactions to environmental sounds encountered in the everyday life: “I find it hard to relax in a place that’s noisy”; “I get mad at people who make noise that keeps me from falling asleep or getting work done”; “I get annoyed when my neighbours are noisy”; “I get used to most noises without much difficulty” (reverse coded); and “I am sensitive to noise”. These items are measured on 6-point bipolar Likert scales (from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”), where higher mean scores indicate higher NS. Internal consistency of the BNSS-SF in our study was acceptable (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.80).

Other covariates

We collected information on factors that may relate to traffic noise and mental ill-health or modify the nature of their relationship. Questionnaire-elicited variables were age, gender, nationality (Bulgarian vs other), perceived income adequacy (“Having in mind your monthly income, how easy is it for you to ‘make ends meet’ and meet your expenses without depriving yourself?”; 0, very difficult to 5, very easy), and average time spent at home/day. To account for differences in students’ timetable and academic demands, we considered at which university faculty they were enrolled.

Geographic data included population density in the 500-m buffer around the residence and nitrogen dioxide (NO2), calculated as a proxy for residential air pollution. For population density, we used a map based on the 2011 Bulgarian Census (1 × 1 km grid).[32] For NO2, we employed a global LUR model constructed using data from air quality monitoring stations, which were predicted from satellite-based NO2 and other commonly used geographic variables related to air pollution.[41]

Statistical analyses

Missing values (<10% on any given variable) were missing at random, therefore, they were imputed using the expectation-maximization algorithm.[42] All variables included in the multivariate analysis models were also included in the imputation procedure.

T-test, chi-square test, Mood’s median test, and correlations (Pearson, point-biserial, and phi) were calculated to identify general patterns of association in the data. We employed the product-of-coefficients approach to mediation analysis[43] implemented in the PROCESS v 3.4. macro (model template 4).[44] We calculated the total effect of LAeq on GAD-7 and PHQ-9, as well as the direct and indirect effects through NA. Linear regression was used for the models with continuous GAD-7 and PHQ-9 scores, and logistic regression for the dichotomized GAD-7 and PHQ-9 scores. Models were adjusted for gender, age, nationality, income adequacy, population density, and university faculty. These models did not suffer from multicollinearity according to tolerance (>0.2) and Variance Inflation Factor (<5) values. Indirect effects were calculated as the product of the association of LAeq with NA and the association of NA with GAD-7/PHQ-9 controlling for LAeq. The indirect effect was then tested using the percentile bootstrap 95% CI (based on 5000 resamples), where an indirect effect that significantly exceeded zero was taken as evidence of mediation.[44] Continuous variables deviating from normal distribution were still analysed with parametric methods because parametric tests[45,46] and bootstrapping[47,48] are fairly robust against moderate violations of the normal distribution assumption.

Then, we conducted moderation analysis (PROCESS, model template 1) to test the hypothesis that the strength of the relationship between LAeq and NA was conditioned on NS and dichotomized GAD-7/PHQ-9. The BNSS-SF score was split at the median (<4 vs. ≥4) to define high and low NS. Because of the small sample size, the criterion for statistical consideration of interactions (LAeq×BNSS-SF and LAeq×GAD-7/PHQ-9) was relaxed to P < 0.1 (i.e., Type I error rate of 10%) to report relevant effect modification that might otherwise remain undetected.[49,50,51]

Next, we rendered a moderated mediation model (PROCESS, model template 7), in which the indirect effect of LAeq on GAD-7/PHQ-9 through NA was conditional on participant’s BNSS-SF score. We used the index of moderated mediation to test the difference between the conditional indirect effects across the low and high NS groups. That index is based on an interval estimate of the parameter of a function linking the indirect effect of LAeq to NS.[52]

In further analyses, we constructed multiplicative interaction terms to investigate possible moderation of the relationships of LAeq with NA and GAD-7/PHQ-9 by gender, nationality, time spent at home/day (<8 vs. ≥8 hours/day), and NO2.

Data were processed with SPSS (IBM Corp. Released 2015. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.). Associations were considered statistically significant at the P < 0.05 level, except for interactions in the moderation models.

RESULTS

Sample characteristics and univariate associations

Tables 1 and 2 shows descriptive characteristics of the sample. Evidence of at least moderate depression and anxiety was found for 19.7% and 14.2% of the students, respectively. Univariate tests indicated that depressive symptoms were more common in foreign students. Those with anxiety reported lower income adequacy. Presence of depression and anxiety was associated with markedly higher NS and NA.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics according to mental ill-health status (N = 437)

| Characteristics | Depression (PHQ-9 ≥ 10) | Anxiety (GAD-7 ≥ 10) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| No ( N = 351) | Yes ( N = 86) | No ( N = 375) | Yes ( N = 62) | |

| Age (median ± IQR) | 21.00 ± 2.00 | 21.00 ± 3.00 | 21.00 ± 2.00 | 21.00 ± 3.00 |

| Gender: male (N, %) | 125 (35.6) | 30 (34.9) | 133 (35.5) | 22 (35.5) |

| Nationality: Bulgarian (N, %) | 277 (78.9) | 59 (68.6)* | 293 (78.1) | 43 (69.4) |

| Income adequacy (mean ± SD) | 2.98 ± 1.16 | 2.75 ± 1.42 | 2.99 ± 1.17 | 2.61 ± 1.41* |

| LAeq [dB(A)] (mean ± SD) | 67.10 ± 1.59 | 67.12 ± 1.51 | 67.11 ± 1.58 | 67.08 ± 1.55 |

| Noise annoyance (median ± IQR | 1.00 ± 2.00 | 2.00 ± 1.11* | 1.00 ± 2.00 | 2.00 ± 2.00* |

| Noise sensitivity (mean ± SD) | 3.86 ± 1.25 | 4.36 ± 1.16* | 3.89 ± 1.25 | 4.38 ± 1.21* |

| Population (median ± IQR) | 9338 ± 3478 | 9338 ± 3779 | 9339 ± 3219 | 7718 ± 3411* |

| NO2 [µg/m3] (mean ± SD) | 19.61 ± 2.91 | 19.68 ± 2.94 | 19.63 ± 2.86 | 19.62 ± 3.24 |

| Time at home: > 8 hours/day (N, %) | 211 (60.1) | 48 (55.8) | 220 (58.7) | 39 (62.9) |

Note. Abbreviations: GAD-7–Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item, IQR − interquartile range, LAeq – equivalent daytime road traffic noise level, NO2–nitrogen dioxide, PHQ-9–Patient Health Questionnaire 9-item, SD − standard deviation.Percentages are reported within columns. T-test is used for comparison of means, chi-square test for proportions, and Mood’s median test for medians.*Statistically significant difference between participants below and above PHQ-9/GAD-7 threshold.

Table 2.

Bivariate associations between the main variables in the study

| Variable | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Depression (PHQ-9) | 1.00 | 0.69* | 0.03 | 0.13* | 0.16* |

| 2. Anxiety (GAD-7) | 1.00 | 0.03 | 0.14* | 0.17* | |

| 3. LAeq | 1.00 | 0.16* | -0.05 | ||

| 4. Noise annoyance | 1.00 | 0.21* | |||

| 5. Noise sensitivity | 1.00 |

Note. Abbreviations: GAD-7–Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item, LAeq − equivalent daytime road traffic noise level, PHQ-9–Patient Health Questionnaire 9-item.Coefficients are Pearson, point-biserial, and phi-correlation coefficients. All variables are measured on a continuous scale. *Correlation is significant at the P < 0.05 level.

The directions of correlations between GAD-7/PHQ-9 and other core variables in the model were in line with theory. Higher GAD-7/PHQ-9 scores related to higher NS and NA, while NA was positively correlated with LAeq and NS. NS and LAeq were not correlated.

Main analyses

Table 3 shows the total, direct and indirect effects of LAeq on PHQ-9 and GAD-7. Tests of the mediation models indicated that LAeq related to depression and anxiety only indirectly through higher NA. This effect was observed for both continuous and dichotomized PHQ-9/GAD-7.

Table 3.

Mediation models of the relationship between road traffic noise (LAeq) and mental ill-health through noise annoyance

| Continuous symptoms score | Dichotomized symptoms score | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| Depression | Anxiety | Depression(PHQ-9 ≥ 10) | Anxiety(GAD-7 ≥ 10) | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| β (95% CI) | β (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Total effect | 0.13 (−1.20, 1.45) | 0.34 (−1.02, 1.70) | 0.86 (0.39, 1.93) | 1.16 (0.45, 2.99) |

| Direct effect | −0.17 (−1.51, 1.17) | −0.02 (−1.39, 1.36) | 0.71 (0.31, 1.61) | 0.93 (0.35, 2.46) |

| Indirect effect | 0.30 (0.01, 0.71) * | 0.35 (0.06, 0.76) * | 1.20 (1.03, 1.50) * | 1.20 (1.01, 1.52) * |

Note. Abbreviations: GAD-7–Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item, LAeq − equivalent daytime road traffic noise level, PHQ-9–Patient Health Questionnaire 9-item.The models are adjusted for gender, age, nationality, income adequacy, population density, and university faculty.Effect estimates of LAeq are reported per 5 dB(A) increase. Coefficients are unstandardized linear regression coefficients (β) and odds ratios (OR) with their 95% confidence intervals (CI). The indirect effects were tested using the percentile bootstrap 95% CI (based on 5000 resamples). Statistically significant associations (P-value<0.05) are denoted by an asterisk (*).

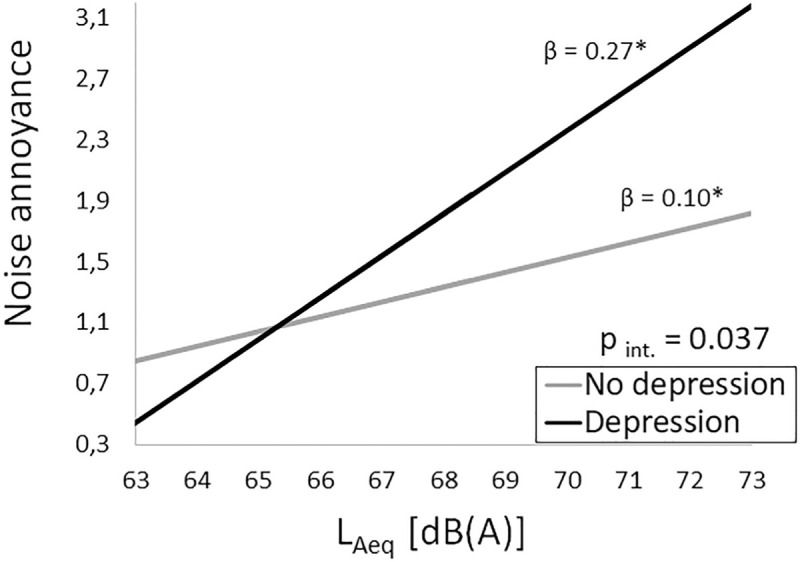

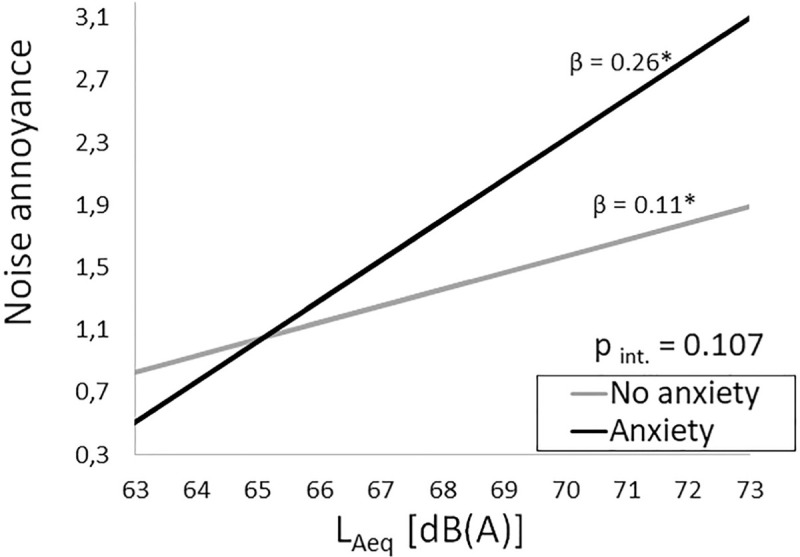

As can be seen in Figures 12, an increase in LAeq was associated with higher NA, but this association was stronger in participants with depression compared with their counterparts. The interaction term for LAeq and anxiety was borderline significant and in the same direction.

Figure 1.

Conditional effect of residential road traffic noise (LAeq) on noise annoyance depending on presence of depression symptoms. Note. Abbreviations: β − unstandardized linear regression coefficient for trend per 1 dB(A), p int. – p-value from test of interaction between LAeq and depression. Statistically significant associations between LAeq and noise annoyance (β, P-value<0.05) are denoted by an asterisk (*). The model is adjusted for gender, age, nationality, income adequacy, population density, and university faculty.

Figure 2.

Conditional effect of residential road traffic noise (LAeq) on noise annoyance depending on presence of anxiety symptoms. Note. Abbreviations: β − unstandardized linear regression coefficient for trend per 1 dB(A), p int. – p-value from test of interaction between LAeq and anxiety. Statistically significant associations between LAeq and noise annoyance (β, P-value<0.05) are denoted by an asterisk (*). The model is adjusted for gender, age, nationality, income adequacy, population density, and university faculty.

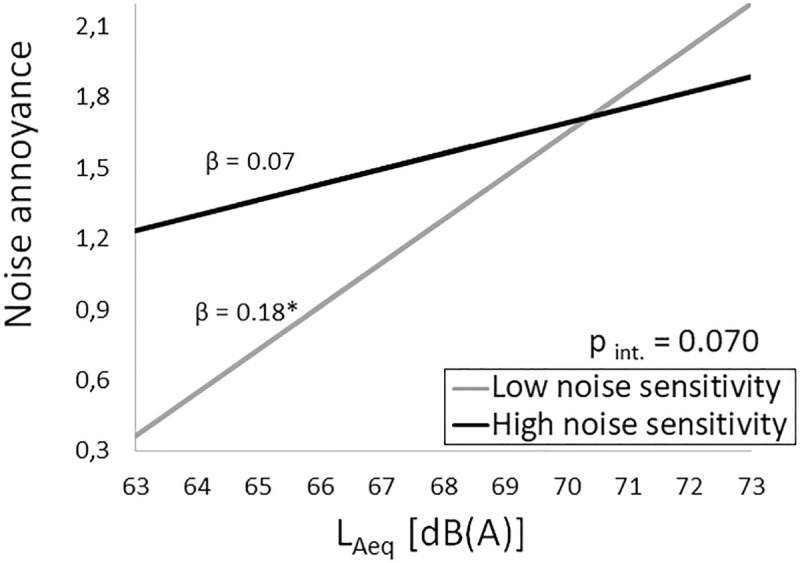

As can be seen in Figure 3, NS moderated the LAeq – NA relationship. While the average level of NA was higher in noise sensitive individuals, increase in LAeq was positively associated with NA only in those low on NS. In line with this finding, in the moderated mediation model LAeq only had an indirect effect on PHQ-9/GAD-7 in the low NS individuals [Table 4].

Figure 3.

Conditional effect of residential road traffic noise (LAeq) on noise annoyance depending on participant’s noise sensitivity. Note. Abbreviations: β − unstandardized linear regression coefficient for trend per 1 dB(A), p int. – p-value from test of interaction between LAeq and noise sensitivity. Statistically significant associations between LAeq and noise annoyance (β, P-value<0.05) are denoted by an asterisk (*). The model is adjusted for gender, age, nationality, income adequacy, population density, and university faculty.

Table 4.

Moderated mediation models of the relationship between residential noise (LAeq) and mental ill-health through noise annoyance, depending on participant’s noise sensitivity

| Continuous symptoms score | Dichotomized symptoms score | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| Depression | Anxiety | Depression | Anxiety | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| β (95% CI) | β (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Conditional indirect effects | ||||

| Low noise sensitivity (n = 222) | 0.42 (0.02, 0.96) * | 0.51 (0.11, 1.02) * | 1.29 (1.05, 1.74) * | 1.30 (1.01, 1.81) * |

| High noise sensitivity (n = 215) | 0.15 (−0.11, 0.56) | 0.18 (−0.12, 0.62) | 1.10 (0.94, 1.37) | 1.10 (0.94, 1.39) |

| Index of moderated mediationa | −0.27 (−0.81, 0.06) | −0.33 (−0.85, 0.05) | 0.85 (0.62, 1.03) | 0.85 (0.62, 1.04) |

Note. Abbreviations: LAeq – equivalent daytime road traffic noise level. The models are adjusted for gender, age, nationality, income adequacy, population density, and university faculty. aThe index of moderated mediation represents the difference between conditional indirect effects.Effect estimates of LAeq are reported per 5 dB(A) increase. Coefficients are unstandardized linear regression coefficients (β) and odds ratios (OR) with their 95% confidence intervals (CI). The indirect effects were tested using the percentile bootstrap 95% CI (based on 5000 resamples).Statistically significant associations (P-value<0.05) are denoted by an asterisk (*).

Further analyses

No interaction between LAeq and NO2 was observed. However, gender moderated the association between LAeq and PHQ-9 (p int. = 0.046), with a positive association observed in women (β per 5dB(A) = 1.15; 95% CI: −0.51, 2.81) and a negative association in men (β per 5dB(A) = −1.54; 95% CI: −3.65, 0.56). The association with NA was moderated by time spent at home (p int. = 0.006) and nationality (pint. = 0.033). It was more pronounced in foreign (β per 5dB(A) = 1.38; 95% CI: 0.63, 2.14) than in domestic students (β per 5dB(A) = 0.47; 95% CI: 0.10, 0.83). An increase in LAeq was associated with higher NA only in students spending > 8 hours/day at home (β per 5dB(A) = 1.09; 95% CI: 0.63, 1.54) but not in their counterparts (β per 5dB(A) = 0.19; 95% CI: −0.27, 0.64).

DISCUSSION

Key findings

This is one of the few studies investigating effects of road traffic noise on depression and anxiety.[53] No direct association was found between exposure to road traffic noise and mental ill-health. However, noise exposure was indirectly associated with symptoms of depression and anxiety through higher NA. Although NA is widely accepted as an intervening variable,[14] few other studies have formally tested mediation by NA of the noise − mental ill-health relationship.[27,32,54] Findings of recent systematic reviews on the topic yielded evidence of “very low quality”.[53,55] In a meta-analysis including ten studies on depression and five on anxiety, Dzhambov and Lercher observed 4% (95% CI: −3%, 11%) higher odds of depression and 12% (95% CI: −4%, 30%) of anxiety associated with a 10 dB(A) increase in day-evening-night noise level.[53] However, the authors noted that none of the reviewed studies had investigated underlying mechanisms.[53] As demonstrated here and in earlier research,[32] decomposition of the total effect of noise when multiple indirect pathways operate in opposite directions reveals a broader picture than focusing only on the total effect. Thus far, such path analysis has rarely been employed in the field[27,32,54] which could have resulted in inconsistent findings.

In line with previous research,[22] we observed moderation by NS of the indirect association between traffic noise exposure and mental ill-health. However, our findings expand the conventional view that individuals high on NS experience stronger adverse effects of noise.[20,21] To be sure, NA was considerably higher even at low noise levels in the high NS group − an aspect of this interaction that is usually of interest.[16,22] However, we believe that interpreting the difference in regression slopes across NS groups has greater applied value for predicting effectiveness of noise abatement interventions. In our case, increase in traffic noise contributed modestly to NA that was already high in the high NS group. On the other hand, in the low NS group, traffic noise had a pronounced positive association with NA. One angle to this could be that in highly noise sensitive people non-acoustic and contextual factors [56,57,58] outweigh the influence of noise exposure and act as risk factors in themselves. For example, noise sensitive people may tend to avoid noise exposure more and this avoidance behaviour may dilute the associations linking noise to mental ill-health.[22] They would either leave high noise areas or not move into these areas in the first place.[59] Hence, for them psychological and social interventions may confer greater health benefits than noise abatement through engineering approaches. There have been accounts of high NA persisting even after objective reduction in road traffic noise − a natural experiment found no reduction in NA and no change in mental health following reduction in noise exposure.[60] Conversely, physical reduction of noise level may effectively lower NA in individuals low on NS, for whom non-acoustic factors play a lesser role. Understanding these vulnerability profiles within the community could aid noise policy and increase efficacy of interventions.

In light of our findings about NS, the latter cannot explain why the relationship between traffic noise and NA was considerably stronger in participants with symptoms severity consistent with depression/anxiety. Individuals with poor mental health have limited resources to cope with noise [61] beyond their high NS. Mental disorders are characterised by dysfunctional cognitive schemas, such as feelings of loss of control over one’s environment and ensuing perceived helplessness,[62,63] which could make the individual more susceptible to noise. We could not explore those factors here, but empirical evidence lends support to this conjecture. Riedel et al. [64] found that the value residents ascribed to being able to control noise exposure moderated the potential indirect effect of road traffic noise on NA through perceived noise control. Relatedly, over-vigilance to danger signals may also precipitate vulnerability to environmental noise.[65,66] In specific phobia, for instance, auditory cues can trigger arousal and negative emotional response.[67] Depression may also be characterized by genetic hypersensitivity to the biological effect of stress, which may extent to environmental noise.[19] Thus, our findings support an earlier proposition that the effect of noise is contingent on individual’s mental health status.[29]

Finally, we found stronger associations with depression in women and with NA in foreign students and those spending more time at home. Evidence about gender differences in the noise and health literature is mixed and inconclusive.[18] As for being a foreign student in Plovdiv, that entails daily mobility largely limited to the residential neighbourhood, which could have reduced exposure misclassification. The same applies to spending more leisure time at home.

Limitations

This study has a number of limitations. First, a cross-sectional design can only capture a snapshot of a truly longitudinal effect; therefore, causal inferences are hindered. The stronger temporal predictor in the potentially reciprocal association between NA and mental ill-health could not be established.[61]

Second, due to limited data availability, we only considered the daytime LAeq indicator. Yet, alternative noise indicators for exposure to multiple sound sources may perform better and yield stronger exposure-response relationships in noise and health research.[68,69] Further, the quality of LUR models is lower than sophisticated propagation models,[70,71] therefore exposure misclassification could have attenuated the association with depression/anxiety. Unfortunately, the EU strategic noise map of Plovdiv only reports noise levels in 5-dB isophones and lacks precision. Therefore, we preferred to use the LUR noise estimates.

Third, our sample was from a very specific setting (i.e., medical university), so it was not representative of all young adults in Plovdiv. The internal validity of our study should still be high though, because we controlled for sociodemographic and residential factors.

Fourth, we relied on self-reported measures of depression/anxiety symptoms. While objective indicators like psychiatric diagnoses and information on psychotropic mediation use eliminate self-report bias and facilitate standardization, self-reports still provide relevant information about subthreshold conditions that often remain undiagnosed.

Fifth, we only considered a narrow set out of a multitude of intertwined processes and contextual influences.[58,72] Effects of other co-exposures and protective resources, which shape the cycles of stress and restoration in the residential environment,[73] should be explored further. In order to inform stakeholders and develop viable public health strategies for mitigating non-auditory traffic noise effects, research on potential mechanisms and their contingencies should continue. Through the lens of life-course epidemiology, critical developmental periods for counteracting these processes can be identified.[74]

CONCLUSIONS

Road traffic noise exposure was indirectly associated with depression and anxiety through higher noise annoyance, but only among those low on noise sensitivity. While high noise sensitivity was associated with high noise annoyance even at low noise levels, increase in traffic noise contributed to noise annoyance only in those low on noise sensitivity. The relationship between noise and annoyance was stronger in those reporting mental ill-health. Understanding these vulnerability profiles within the community could aid noise policy and increase efficacy of interventions.

Financial support and sponsorship

National program “Young Scientists and Postdoctoral Candidates” of the Ministry of Education and Science, Bulgaria.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to the participating students for making this study possible. Angel Dzhambov’s work on this publication was partially supported by the National program “Young Scientists and Postdoctoral Candidates” of the Ministry of Education and Science, Bulgaria.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stansfeld S, Clark C, Bebbington P, King M, Jenkins R, Hinchliffe S. Common mental disorders. Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenzweig MR, Krech D, Bennett EL, Diamond MC. Effects of environmental complexity and training on brain chemistry and anatomy: a replication and extension. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1962;55:429–37. doi: 10.1037/h0041137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lovden M, Wenger E, Martensson J, Lindenberger U, Backman L. Structural brain plasticity in adult learning and development. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013;37:2296–310. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uher R. Gene-environment interactions in severe mental illness. Front Psychiatry. 2014;5:48. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Os J, Kenis G, Rutten BP. The environment and schizophrenia. Nature. 2010;468:203–12. doi: 10.1038/nature09563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO. Environmental Noise Guidelines for the European Region. WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Westman JC, Walters JR. Noise and stress: a comprehensive approach. Environ Health Perspect. 1981;41:291–309. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8141291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ising H, Kruppa B. Health effects caused by noise: evidence in the literature from the past 25 years. Noise Health. 2004;22:5–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hahad O, Prochaska JH, Daiber A, Münzel T. Environmental noise-induced effects on stress hormones, oxidative stress, and vascular dysfunction: key factors in the relationship between cerebrocardiovascular and psychological disorders. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 2019:4623109. doi: 10.1155/2019/4623109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lupien SJ, Juster RP, Raymond C, Marin MF. The effects of chronic stress on the human brain: From neurotoxicity, to vulnerability, to opportunity. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2018;49:91–105. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2018.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guski R. Personal and social variables as co-determinants of noise annoyance. Noise Health. 1999;1:45–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guski R, Felscher-Suhr U, Schuemer R. The concept of noise annoyance: how international experts see it. J Sound Vib. 1999;223:513–27. [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Kamp I, Davies H. Environmental noise and mental health: Five year review and future directions. Proceedings of 9th International Congress on Noise as a Public Health Problem (ICBEN), Foxwoods, CT. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.von Lindern E, Hartig T, Lercher P. Traffic-related exposures, constrained restoration, and health in the residential context. Health Place. 2016;39:92–100. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heinonen-Guzejev M. Noise sensitivity − medical, psychological and genetic aspects [PhD thesis] University of Helsinki. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shepherd D, Heinonen-Guzejev M, Hautus MJ, Heikkilä K. Elucidating the relationship between noise sensitivity and personality. Noise Health. 2015;17:165–71. doi: 10.4103/1463-1741.155850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hill EM. Noise sensitivity and diminished health: the role of stress-related factors [Ph.D. thesis] Auckland University of Technology. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stansfeld SA. Noise, noise sensitivity and psychiatric disorder: epidemiological and psychophysiological studies. Psychol Med. 1992;22:1–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Kamp I, Job RFS, Hatfield J, Haines M, Stellato RK, Stansfeld SA. The role of noise sensitivity in the noise-response relation: a comparison of three international airport studies. J Acoust Soc Am. 2004;116:3471–9. doi: 10.1121/1.1810291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miedema HM, Vos H. Noise sensitivity and reactions to noise and other environmental conditions. J Acoust Soc Am. 2003;113:1492–504. doi: 10.1121/1.1547437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stansfeld S, Clark C, Smuk M, Gallacher J, Babisch W. Noise sensitivity, health and mortality − a review and new analyses. Proceedings of 12th ICBEN Congress on Noise as a Public Health Problem, 18-22 June 2017, Zurich. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park J, Chung S, Lee J, Sung JH, Cho SW, Sim CS. Noise sensitivity, rather than noise level, predicts the non-auditory effects of noise in community samples: a population-based survey. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:315. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4244-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mogg K, Bradley BP. A cognitive-motivational analysis of anxiety. Behav Res Ther. 1998;36:809–48. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00063-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clark DA, Beck AT. Cognitive Therapy of Anxiety Disorders. Science and Practice. New York: The Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stecker R. Motivational consequences of environmental stress. J Environ Psychol. 2004;24:143–65. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fyhri A, Klaeboe R. Road traffic noise, sensitivity, annoyance and self-reported health − a structural equation model exercise. Environ Int. 2009;35:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tarnopolsky A, Watkins G, Hand DJ. Aircraft noise and mental health: I. Prevalence of individual symptoms. Psychol Med. 1980;10:683–98. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700054982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Kamp I, van Kempen E, Baliatsas C, Houthuijs D. Mental health as context rather than health outcome of noise: competing hypotheses regarding the role of sensitivity, perceived soundscapes and restoration. In: INTER-NOISE Conference Proceedings, Innsbruck. Institute of Noise Control Engineering. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ribeiro ÍJS, Pereira R, Freire IV, de Oliveira BG, Casotti CA, Boery EN. Stress and quality of life among university students: A systematic literature review. Health Profes Educ. 2018;4:70–77. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dzhambov AM, Hartig T, Tilov B, Atanasova V, Makakova DR, Dimitrova DD. Residential greenspace is associated with mental health via intertwined capacity-building and capacity-restoring pathways. Environ Res. 2019;178:108708. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2019.108708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dzhambov AM, Markevych I, Tilov B, Arabadzhiev Z, Stoyanov D, Gatseva P, et al. Pathways linking residential noise and air pollution to mental ill-health in young adults. Environ Res. 2018;166:458–65. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2018.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manea L, Gilbody S, McMillan D. Optimal cut-off score for diagnosing depression with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9): a meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2012;184:E191–E196. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.110829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Plummer F, Manea L, Trepel D, McMillan D. Screening for anxiety disorders with the GAD-7 and GAD-2: a systematic review and diagnostic metaanalysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2016;39:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fields JM, de Jong RG, Gjestland T, Flindell IH, Job RFS, Kurra S, et al. Standardized General-Purpose Noise Reaction Questions for Community Noise Surveys: Research and a Recommendation. J Sound Vib. 2001;242:641–79. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Benfield JA, Nurse AG, Jakubowski R, Gibson AW, Taff BD, Newman P, et al. Testing noise in the field: A brief measure of individual noise sensitivity. Environ Behav. 2012;20:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weinstein ND. Individual differences in reactions to noise: a longitudinal study in a college dormitory. J Appl Psychol. 1978;63:458–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dzhambov AM, Dimitrova DD. Psychometric properties of the Bulgarian translation of noise sensitivity scale short form (NSS-SF): implementation in the field of noise control. Noise Health. 2014;16:361–7. doi: 10.4103/1463-1741.144409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Larkin A, Geddes JA, Martin RV, Xiao Q, Liu Y, Marshall JD, et al. Global land use regression model for nitrogen dioxide air pollution. Environ Sci Technol. 2017;51:6957–64. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.7b01148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dempster AP, Laird NM, Rubin DB. Maximum likelihood estimation from incomplete data via the EM algorithm (with discussion) J Royal Stat Assoc. 1977;B39:1–38. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alwin DF, Hauser RM. The decomposition of effects in path analysis. Am Sociol Rev. 1975;40:37–47. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hayes A. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. 2nd Edition. New York: Guilford Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schmider E, Ziegler M, Danay E, Beyer L, Bühner M. Is it really robust? Reinvestigating the robustness of ANOVA against violations of the normal distribution assumption. Meth Eur J Res Meth Behav Soc Sci. 2010;6:147–51. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Blanca MJ, Alarcón R, Arnau J, Bono R, Bendayan R. Non-normal data: is ANOVA still a valid option? Psicothema. 2017;29:552–7. doi: 10.7334/psicothema2016.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Haukoos JS, Lewis RJ. Advanced statistics: bootstrapping confidence intervals for statistics with “difficult” distributions. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:360–5. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2004.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kelley K. The effects of nonnormal distributions on confidence intervals around the standardized mean difference: bootstrap and parametric confidence intervals. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2005;65:51–69. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Selvin S. Statistical Analysis of Epidemiologic Data. New York: NY: Oxford University Press; 1996. pp. 213–214. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Greenland S, Rothman KJ. Chapter 18: Concepts of Interaction. In: Rothman KJ, Greenland S, editors. Modern Epidemiology. 2nd ed. New York: Lippincott-Raven; 1998. pp. 329–42. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marshall SW. Power for tests of interaction: effect of raising the Type I error rate. Epidemiologic Perspectives and Innovations. 2007 doi: 10.1186/1742-5573-4-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hayes AF. An Index and Test of Linear Moderated Mediation. Multivar Behav Res. 2015;50:1–22. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2014.962683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dzhambov AM, Lercher P. Road traffic noise exposure and depression/anxiety: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:4134. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16214134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dzhambov A, Tilov B, Markevych I, Dimitrova D. Residential road traffic noise and general mental health in youth: The role of noise annoyance, neighborhood restorative quality, physical activity, and social cohesion as potential mediators. Environ Int. 2017;109:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2017.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Clark C, Paunovic K. WHO Environmental Noise Guidelines for the European Region: A Systematic Review on Environmental Noise and Quality of Life, Wellbeing and Mental Health. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:2400. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15112400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lercher P. Environmental noise and health: An integrated research perspective. Environ Int. 1996;22:117–29. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lercher P. Environmental noise: A contextual public health perspective. In: Luxon D, Prasher LM, editors. Noise and its effects. London: Wiley; 2007. pp. 345–377. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lercher P, De Coensel B, Dekonink L, Botteldooren D. Community response to multiple sound sources: Integrating acoustic and contextual approaches in the analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14:663. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14060663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nijland HA, Hartemink S, van Kamp I, van Wee B. The influence of sensitivity for road traffic noise on residential location: does it trigger a process of spatial selection? J Acoust Soc Am. 2007;122:1595. doi: 10.1121/1.2756970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stansfeld SA, Haines MM, Berry B, Burr M. Reduction of road traffic noise and mental health: an intervention study. Noise Health. 2009;11:169–75. doi: 10.4103/1463-1741.53364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schreckenberg D, Meis M, Kahl C, Peschel C, Eikmann T. Aircraft noise and quality of life around Frankfurt Airport. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2010;7:3382–405. doi: 10.3390/ijerph7093382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Evans GW. The built environment and mental health. J Urban Health. 2003;80:536–55. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jtg063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hatfield J, Job RS, Hede AJ, Carter NL, Peploe P, Taylor R, et al. Human response to environmental noise: The role of perceived control. Int J Behav Med. 2002;9:341–59. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0904_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Riedel N, Köckler H, Scheiner J, van Kamp I, Erbel R, Loerbroks A, et al. Urban road traffic noise and noise annoyance-a study on perceived noise control and its value among the elderly. Eur J Public Health. 2019;29:377–9. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cky141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Somerville LH, Wagner DD, Wig GS, Moran JM, Whalen PJ, Kelley WM. Interactions between transient and sustained neural signals support the generation and regulation of anxious emotion. Cereb Cortex. 2013;23:49–60. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shepherd D, Hautus MJ, Lee SY, Mulgrew J. Electrophysiological approaches to noise sensitivity. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2016;38:900–12. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2016.1176995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schröder A, Vulink N, Denys D. Misophonia: diagnostic criteria for a new psychiatric disorder. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54706. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lercher P, Boeckstael A, De Coensel B, Dekoninck L, Botteldooren D. The application of a notice-event model to improve classical exposure-annoyance estimation. J Acoust Soc Am. 2012;131:3223. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lercher P, De Coensel B, Dekoninck L, Botteldooren D. Alternative traffic noise indicators and its association with hypertension. In: Proceedings of EuroNoise. Hersonissos, Crete, Greece, 27-31. May 2018. pp. 457–464. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Aguilera I, Foraster M, Basagaña X, Corradi E, Deltell A, Morelli X, et al. Application of land use regression modelling to assess the spatial distribution of road traffic noise in three European cities. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2015;25:97–105. doi: 10.1038/jes.2014.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ragettli MS, Goudreau S, Plante C, Fournier M, Hatzopoulou M, Perron S, et al. Statistical modeling of the spatial variability of environmental noise levels in Montreal, Canada, using noise measurements and land use characteristics. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2016;26:597–605. doi: 10.1038/jes.2015.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lovasi GS, Mooney SJ, Muennig P, DiMaggio C. Cause and context: place-based approaches to investigate how environments affect mental health. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51:1571–9. doi: 10.1007/s00127-016-1300-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Riedel N, Köckler H, Scheiner J, Berger K. Objective exposure to road traffic noise, noise annoyance and self-rated poor health − framing the relationship between noise and health as a matter of multiple stressors and resources in urban neighbourhoods. J Environ Plan Manage. 2015;58:336–56. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kuh D, Ben-Shlomo Y, Lynch J, Hallqvist J, Power C. Life course epidemiology J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57:778–83. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.10.778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]