Abstract

Introduction

In parallel to the clinical maturation of heart transplantation over the last 50 years, rejection testing has been revolutionized within the systems biology paradigm triggered by the Human Genome Project.

Areas Covered

We have co-developed the first FDA-cleared diagnostic and prognostic leukocyte gene expression profiling biomarker test in transplantation medicine that gained international evidence-based medicine guideline acceptance to rule out moderate/severe acute cellular cardiac allograft rejection without invasive endomyocardial biopsies. This work prompted molecular re-classification of intragraft biology, culminating in the identification of a pattern of intragraft myocyte injury, in addition to acute cellular rejection and antibody-mediated rejection. This insight stimulated research into non-invasive detection of myocardial allograft injury. The addition of a donor-organ specific myocardial injury marker based on donor-derived cell-free DNA further strengthens the non-invasive monitoring concept, combining the clinical use of two complementary non-invasive blood-based measures, host immune activity-related risk of acute rejection as well as cardiac allograft injury.

Expert Opinion

This novel complementary non-invasive heart transplant monitoring strategy based on leukocyte gene expression profiling and donor-derived cell-free DNA that incorporates longitudinal variability measures provides an exciting novel algorithm of heart transplant allograft monitoring. This algorithm’s clinical utility will need to be tested in an appropriately designed randomized clinical trial which is in preparation.

Keywords: heart transplantation, allograft rejection, endomyocardial biopsy, peripheral blood mononuclear cell transcriptome profiling, cell-free DNA, outcome prediction, organ dysfunction, biomarker, precision medicine, personalized medicine

1 -. THE HISTORICAL CONTEXT OF HEART TRANSPLANT REJECTION DIAGNOSTICS: HISTOLOGY & CLINICAL CHEMISTRY

Since the development of cardiac transplantation at Stanford University in the 1960’s [1] and implementation of endomyocardial biopsy (EMB) as standard test to monitor allograft rejection in the 1970’s [2], EMB has become the gold standard of rejection diagnostics and evolved to a consensus classification of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) in 1990 [3] that continued to be updated [4]. However, the lack of mechanistic insights and concordance between expert pathology reviewers [5,6] as well as the invasive nature and resource-intensity of EMB represent serious limitations. This procedure is expensive, painful and may lead to potential complications, such as puncture of the adjacent carotid artery during catheter insertion, cardiac perforation with tamponade, pneumothorax, damage to the tricuspid valve, air embolism, atrial arrhythmias, and prolonged bleeding [7-11].

These drawbacks gave rise to a variety of non-invasive rejection diagnostics over the last 40 years none of which has been in a position to completely replace EMB, including 1) on the phenome (organ function) level including electrocardiography [12], echocardiography [13-16], magnetic resonance tomography [17,18], 2) on the metabolome level [19], 3) on the proteome level including brain natriuretic peptide [20,21], troponin [22,23], SERCA-2 [24], C-reactive protein [25], cytokines [26], cell surface flow cytometry markers [27], donor-specific antibodies [28,29], exosomes [30], urinary proteins [31], plasma protein pipeline [32], 4) on the transcriptome level including PBMC gene expression profiling [33,34] and microRNA [35-43] profiling, and 5) on the genome level including donor-derived cell-free DNA [44,45].

The lack of close correlation of the ISHLT histological classification of rejection and cardiac allograft functional hemodynamic parameters gave rise to the hypothesis that reversible diastolic and systolic dysfunction following cardiac transplantation was primarily caused by inflammatory mediators that were to some degree independent of histological classes of rejection [15,27,46-50]. Subsequently the completion of the Human Genome Project [51-55] has made possible a revolutionary progress in medicine. This development allowed for the query into the relationship between genomic sequence variability, as well as transcriptomic variations/patterns of gene expression and proteomic patterns in different cell/tissue types and clinical phenotypes. Based on the research into these relationships, the potential arose for the development of novel clinical diagnostic/therapeutic strategies. In this review, the development over the last 25 years will be discussed.

2 -. NON-INVASIVE MULTI-OMIC PATIENT-SPECIFIC BIOMARKERS TO RULE OUT CONCURRENT ACUTE CELLULAR REJECTION OR FUTURE CARDIAC ALLOGRAFT DYSFUNCTION: THE ALLOMAP PROJECT

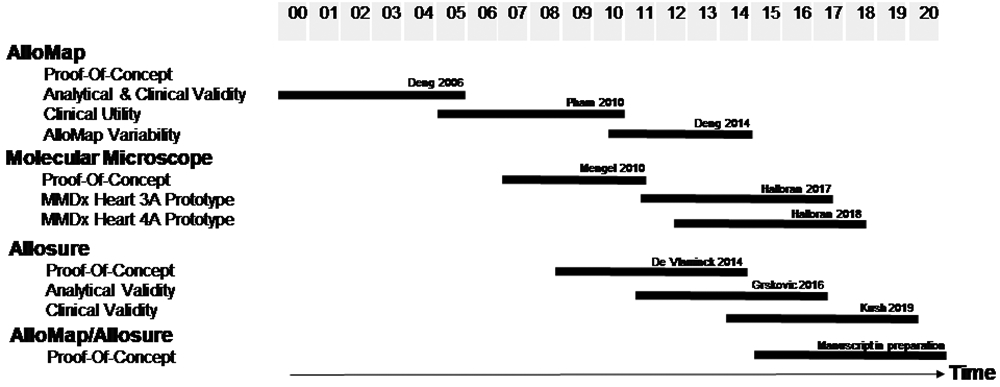

Over the last >25 years, we have co-conceptualized and co-developed the [26,27,33,46,47,56-58] first diagnostic and prognostic leukocyte (peripheral blood mononuclear cell=PBMC) gene expression profiling (GEP) biomarker test in transplantation medicine that gained US-FDA-regulatory clearance and international evidence-based medicine guideline acceptance [59] to rule out rejection without invasive biopsies. The timeline is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1:

Timeline and milestones (details see text).

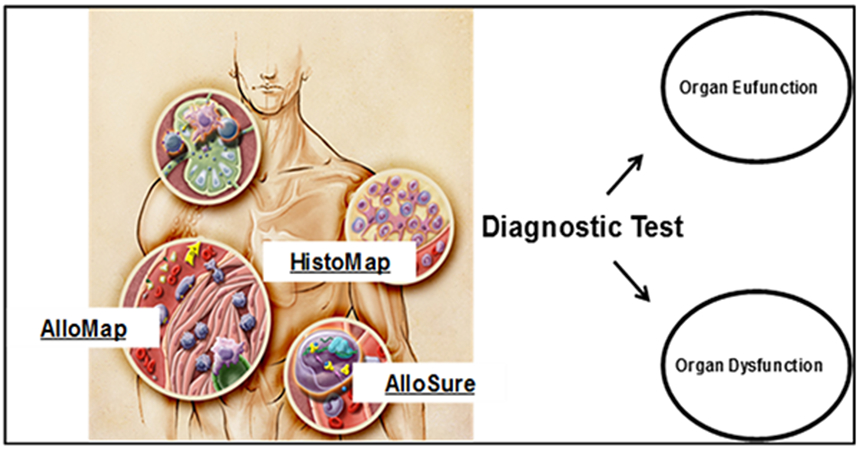

Acute cellular rejection involves the accumulation of mononuclear cells, specifically CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells, in the interstitial space of the allograft as a result of antigens on the donated organ being identified as foreign to the recipient. Based on the mechanistic insight that the allo-antigen presentation of the allograft initiates the allograft recipient’s allo-immune response [37,60] in a complementary key-lock pattern, the testable hypothesis evolved since 2000 in the AlloMap Study Group that the interaction between allograft cells and recipient immune cells should create an gene expression signature in the recipient immune cells, and those subsets of the recipient’s immune cells that re-circulated after allo-antigen contact should provide a peripheral blood gene expression profiling pattern that would elegantly (without accessing the allograft itself by biopsy) allow to identify states of either rejection or quiescence. This concept led to the development of the AlloMap test. Furthermore, since these T-cells initiate an immune cascade that leads to the apoptosis of the targeted allograft cells, these cells ultimately die, their nucleic acids become fragmented, resulting in approximately 120–160 base pair (bp) pieces of double-stranded cell-free DNA (cfDNA) that are released into the blood and ultimately excreted in the urine [61]. This concept subsequently led to the AlloMap complementary non-invasive test component, the AlloSure test. The conceptual framework for the evolution of heart transplant rejection testing is summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2:

Conceptual framework (details see text).

The investigators of the Cardiac Allograft Rejection Gene Expression Observational (CARGO) study [33] and the team at CareDx (formerly XDx Inc) developed and validated this GEP test of PBMC based on comprehensive gene array analysis and DNA-library screening, real time PCR validation, and bioinformatics post processing (www.AlloMap.com). This test, developed against the reference phenotype of endomyocardial biopsy (EMB)-based monitoring [3-5], allows to identify stable heart transplant patients with a low probability of moderate/severe acute cellular cardiac allograft rejection.

The CARGO-study was initiated in 2001 and the results of the discovery of gene expression biomarkers, rejection classifier development and diagnostic validation were published online 2005 [33]. This publication led to an intense international discourse in the scientific community [33,62,63]. The original publication was cited >450 times until June 2020. In a stepwise process recently summarized [56], we 1) identified a well-defined reproducible practice-relevant consensus phenotype framework against which to develop the transcriptomic/genomic biomarker, 2) dichotomized the phenotype framework into “Moderate Rejection’ versus “No Rejection/Quiescence” to maximize probability to detect a differential transcriptomic/genomic biomarker signal, 3) utilized “mixed peripheral blood mononuclear cell population (PBMC)” versus “T-cell/B-Cell” versus “pan-leukocyte” panel, 4) emphasized “Rule Out” test performance characteristics for clinical utility in stable heart transplant patients, 5) performed stringent “Internal Candidate Gene Validation” by RT-PCR, 6) performed stringent Three-Stage “External Test Validation by independent Clinical Cohort” by the North-American CARGO 1 Cohort Study, “External Demographics Validation” by the European CARGO 2 Cohort Study, and “Non-Invasive Clinical Management Strategy Validation” by the IMAGE study, and 7) included a broad clinical adult US heart transplant patient cohort to maximize subsequent generalizability.

After CLIA-certification of the clinical reference laboratory in which the test was developed and validated, clinical implementation was initiated in 2005. Since then, the annual test frequency across the US grew rapidly. From 2006 to 2009, the annual test frequency across the 50 US-states and 130 heart transplant centers grew from 2000 2006) to 6000 (2007), and 13000 (2015). FDA-clearance in the in-vitro-diagnostic multivariate index assay (IVDMIA) category was granted in August 2008 (http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/reviews/K073482.pdf). By June 2020, more than 150,000 cumulative tests had been performed for more than 20,000 cardiac transplant recipients at over 90% of transplant centers in the US.

Based on the CARGO-study [33], a clinical algorithm comprised of routine surveillance clinical visits, noninvasive graft function testing by echocardiography, and AlloMap testing was implemented since 2005 in North America [64] and validated in Europe [65]. Beyond medical benefits, this approach has been suggested to result in healthcare cost savings [66]. While the potential of transcriptome-based testing seemed great, in the early implementation period, obstacles were encountered on four levels: 1) Scientific evidence, 2) Medico-legal concerns, 3) economic concerns, 4) center/investigator profile concerns. Among health-economic concerns were A) AlloMap pricing at 60-70% of EMB-pricing. B) Absence of EMB-related revenue in heart transplant programs [56]. The quest for additional scientific evidence led to the IMAGE-study testing the clinical utility of the AlloMap-based monitoring. In the Invasive-Monitoring Attenuation by Gene Expression (IMAGE) study, this GEP-based monitoring in direct comparison with an EMB-based strategy was non-inferior with respect to detection of clinical rejection, and at the same time improved patient satisfaction [34,67].

The rationale for the original proof-of-concept CARGO-study in 2000 and the clinical utility IMAGE–study in 2005, was to demonstrate the feasibility and clinical effectiveness of a non-invasive rejection-monitoring test in the context of less than optimal outcomes and latent dissatisfaction with the protocol EMB-based strategy. However, EMB had been the standard method of rejection monitoring for more than 30 years. There was near universal adoption and integration of the EMB method by most transplant cardiologists, cardiac surgeons, and pathologists. Although the broad use of EMB was based on tradition [68,69] with the lowest level of clinical evidence [level C-evidence] [70], during the early clinical implementation period starting 2006, there was strong reluctance of heart transplantation centers to abandon a protocol-EMB based rejection monitoring strategy for a novel blood test with only a brief period of clinical experience. Interestingly, this strong reluctance to abandon protocol EMB eased after the publication of IMAGE in 2010. Thus, one of the most challenging issues for the design of both the CARGO- and IMAGE-studies was that, on one hand, there was no abundance of clinical trial evidence demonstrating the superiority of EMB-based monitoring. On the other hand, there was a reluctance of heart transplantation centers to abandon an empirical low-grade evidence protocol-EMB based strategy. In other words, this clinical research was conducted in a domain of tradition [68].

The IMAGE study and its extension into the early post-transplant period E-IMAGE [71] led to a redefinition of rejection from a histology-based to a composite clinical endpoint. The randomized clinical trial study design implied that 1) the patient group assigned to GEP-monitoring would not have histologically defined rejection data, 2) the comparison of rejection endpoints between the IMAGE study arms needed to be defined on the organ function/clinical level, and, thus, the composite primary endpoint combined the organ function level (new onset allograft dysfunction with/without histologically defined rejection) and the clinical level (re-transplantation, death of any cause), and 3) the two rejection paradigms were not directly translatable into one another. Forced by the necessity of the IMAGE study design, we had to make decision to redefine “rejection” in the process of the AlloMap development [48].

It is important to recognize that the two rejection monitoring methods - GEP and EMB - are based on different concepts of rejection (Endomyocardial Biopsy: histology of the transplanted organ, AlloMap: PBMC gene expression profiles in the systemic rejection surveillance paradigm). An implication of leukocyte GEP as surveillance strategy component is that it focuses on the state of the recipient’s immune system rather on the state of the transplanted organ. While EMB addresses whether or not the transplanted organ has been invaded and damaged, the GEP addresses the question whether or not the recipient’s immune system is maintaining quiescence (preventing the invasion and damage from occurring). The GEP strategy focuses on the activation pattern of selected and validated leukocyte gene transcripts rather the light microscopic protein consequences of recipient leukocyte activation in the donor allograft myocardium. Therefore, GEP is most appropriate for a rule-out approach by identifying patients at low risk for rejection (thus characterized by high negative predictive value). In contrast, EMB is most appropriate when a rule-in strategy is needed, characterized by a presumably higher positive predictive value. The new AlloMap-based paradigm incorporated a multisystem level surveillance concept including clinical, graft, histological (as indicated) and molecular levels of information, each level contributing complementary information [48].

The Outcomes AlloMap Registry (OAR), an observational, prospective, multicenter study including patients aged ≥ 15 years and ≥ 55 days post-cardiac transplant, recorded in 1,504 US-patients, who were predominantly Caucasian (69%), male (74%), and aged 54.1 ± 12.9 years, the prevalence of moderate to severe acute cellular rejection (≥2R) (2.0% from 2 to 6 months and 2.2% after 6 months). In the OAR there was no association between higher GEP scores and coronary allograft vasculopathy, cancer, or non-cytomegalovirus infection. Survival at 1, 2, and 5 years post-transplant was 99%, 98%, and 94%, respectively. The composite outcome occurred in 103 patients during the follow-up period. GEP scores in dual-organ recipients (heart-kidney and heart-liver) were comparable to heart-alone recipients. This registry comprises the largest contemporary cohort of patients undergoing GEP for surveillance. It was concluded that among patients selected for GEP surveillance, survival is excellent, and rates of acute rejection, graft dysfunction, readmission, and death are low [72].

During the years of clinical implementation of noninvasive monitoring, we observed an association of low variability of gene expression profiling scores over time and the clinical stability of the individual [58]. Therefore, we hypothesized that the variability of gene expression profiling scores within individuals may predict risk of future allograft events. To test our hypothesis, we utilized the IMAGE study database, which provided independently adjudicated clinical outcome events observed during surveillance of 602 heart transplant recipients. Race, age at time of transplantation, and time post-transplantation were significantly associated with future events in the univariate analysis. In the multivariate analyses, gene expression profiling score variability, but not ordinal scores or scores over threshold, was independently associated with future clinical events. We concluded that 1) the variability of a heart recipient’s GEP test scores over time may provide prognostic utility, and 2) that this information is independent of the probability of ACR at the time of testing that is rendered from a single ordinal GEP test score. For the management of heart transplant patients, these results suggest that a recipient predicted to be at low risk for future events may become a candidate for further minimization of his/her immunosuppressive maintenance regimen. Conversely, an individual predicted to be at higher risk for future events may receive further evaluation to detect possible underlying causes of the variability such as overlooked infections or noncompliance to medications [57]. In an independent validation study on AlloMap variability (AMV) in the CARGO II cohort, the AMV concept was confirmed [73]. This data led to incorporation of AlloMap variability criteria into the clinical algorithm. The initial performance and cutoff characteristics were defined as use starting 315 days post-transplant, suggesting that patients with scores ≤0.6 may be at a lower risk of future events and patients with scores ≥1.6 may be at a higher risk of future events.

There was a sea change in clinical diagnostics development in parallel with development of the AlloMap testing service. Though formal validation phases were not commonly adopted, AlloMap pioneered a three-phase approach encompassing discovery (phase I), development (phase II) and clinical validation (phase III). Since development of AlloMap, a formal phased development of diagnostic tests analogous to the three phased development of drugs has been universally adopted. The three phases in diagnostic development are recognized as analytical validation, clinical validation and clinical utility. Analytical validity refers to how well the test predicts the presence or absence of an analyte or biomarker. In other words, can the test accurately detect whether a biomarker is present or absent? Clinical validity refers to how well the candidate biomarker is related to the presence, absence, or risk of a specific disease. Clinical utility refers to whether the test can provide information about diagnosis, treatment, management, or prevention of a disease that results in net differential outcomes in post-implementation medical practice key to clinician, patients and payers. The rigor of AlloMap development and more recently adopted phased development set a high bar for test development, as detailed in Institute of Medicine monograph “Evolution of Translational Omics: Lessons Learned and the Path Forward” [74].

3 -. IMPLICATIONS OF THE ALLOMAP PROJECT FOR INVASIVE PATIENT-SPECIFIC BIOMARKERS IN THE MOLECULAR MICROSCOPE PROJECT: INTRAGRAFT QUIESCENCE, REJECTION & INJURY

The completion of the AlloMap project led to renewed interest of dissecting intragraft molecular biology and re-conceptualizing the light-microscopy-based histological concepts of antigen-specific rejection and non-specific graft injury with cutting-edge contemporary research tools, specifically by Philip Halloran’s group in Edmonton. Following the publication of the CARGO-study [33], the group initially hypothesized that the parallel assessment of heart transplant EMBs by histological and molecular features compared to clinical features would offer an external comparison for the ISHLT classification and could show whether intragraft molecules could add insight into mechanisms and provide added diagnostic and prognostic information. Sharing the rationale of the AlloMap-study group and based on a histologic and microarray analysis on 105 EMB from 45 heart allograft recipients, the authors concluded that the histological grading system of the ISHLT for diagnosing rejection did not reflect the molecular phenotype in EMB and lacked clinical relevance and that the assessment of molecules in heart biopsy could guide improvements of current diagnostics [75].

From a historical and history-of-science perspective, it is interesting to note that an identical assessment of lack of clinical relevance of the histological ISHLT grading systems provided the motivation for the AlloMap Study group in 2000 [33,46,47] as well as for the Molecular Microscope Study Group in 2010. However, in contrast to the decision by AlloMap Study Group to develop a non-invasive blood test based on PBMC GEP to utilize the recently developed high-throughput technology of gene arrays and simultaneously overcome the side-effect of the invasive EMB, the Edmonton group decided to focus on the use of high throughput gene array technology within the classical framework of EMB.

From a systems biological perspective, the AlloMap concept was based on the assumption that intra-allograft immunological processes would be reflected in a complementary key/lock fashion in the circulating PBMC GEP. In fact, the findings by the Molecular Microscope group that “the transcript changes in EMBs from heart allografts revealed a stereotyped molecular disturbance in which increased expression of transcript sets reflecting inflammation (T cells, macrophages, c -interferon effects) were associated with injury-induced transcripts, endothelial transcripts and loss of transcripts expressed in normal myocardium…The correlations among these non-overlapping transcript sets reveal a complex linkage between inflammation, injury and tissue de-differentiation that is probably a general principal of tissue responses to stress, rather than specific for a disease state… the inflammatory histological and molecular phenotype was strongly associated with an increased expression of injury associated transcripts and a decrease in transcripts expressed in normal hearts, indicating that any inflammation is associated with injury and dedifferentiation of the myocardium” [75] were a reflection of the AlloMap final classifier biology [33]. Acknowledging principal limitations of the EMB-based approach, the Molecular Microscope team states that “sampling error is to a similar extent impeding on histology as it is on molecular measurement, that is cases where histology misses the relevant lesion while they are captured for gene expression analysis might be as frequent as vice versa” [75].

On a clinical utility perspective of moving towards non-invasive transplant diagnostics, the Molecular Microscope team predicted in 2010 the future perspective towards the combined AlloMap/AlloSure non-invasive monitoring by stating that “…once the molecular and histological phenotypes of the EMB are refined and validated, non-biopsy-based diagnostic tests can be reliably validated against them… in a progressive development of an improved diagnostic system in heart transplantation” [75].

In 2017, the Molecular Microscope team published a first-generation EMB-based diagnostic algorithm that was based on a 3-archetype analysis, which gave each biopsy a normalness score (S1-normal), a T-cell-mediated rejection (TCMR) score (S2-TCMR), and an antibody-mediated rejection (ABMR) score (S3-ABMR) describing its closeness to each of the 3 corresponding archetypes, which correlated with rejection in histology diagnoses, albeit with discrepancies as expected. Reflecting on methodological limitations, they note that it is “important to understand the constraints of each measurement platform. The U133 arrays used, for example, have limitations in dynamic range and, even with 54 000 probe sets, miss many potentially important features such as alternative promoters and splicing variants that would be captured by platforms with greater dynamic range and coverage” [76,77].

In a next step, the team sought to characterize the variance in transcript expression in EMBs that was not explained by rejection, hypothesizing that “molecular assessment offers an opportunity to explore the response to injury, and to determine whether injury is being mistaken for rejection in histology”. This elegant study used Affymetrix microarray data from 889 prospectively collected endomyocardial biopsies from 454 transplant recipients at 14 centers subjected to unsupervised principal component analysis and archetypal analysis to detect variation not explained by rejection. The resulting principal component and archetype scores were analyzed for their transcript, transcript set, and pathway associations and compared to the histology diagnoses and left ventricular function. Principal components 1 and 2 reflected T-cell-mediated rejection and antibody-mediated rejection. A novel principal component 3 was interpreted as injury-induced. These three principal components allowed to identify four molecular archetype scores, score 1 indicating normalness, score 2 indicating T-cell-mediated rejection, Score 3 indicating antibody-mediated rejection and – newly described- Score 4 indicating “unexplained variation correlating with expression of transcripts inducible in injury models, many expressed in macrophages and associated with inflammation in pathway analysis”. Score 4 injury scores were high in recent transplants, reflecting donation-implantation injury, and both Score 2 (T-cell-mediated rejection) and Score 4 (injury) were associated with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction. The authors discuss the possibility that the mechanisms causing “injury” supported by the notion of the distinct time courses and transcript associations of these scores compared with the rejection scores, however also state that “nevertheless, some EMBs with rejection can also have high injury-related molecular scores, which is compatible with the concept that rejection can induce injury, and some EMBs display severe rejection and severe injury. Some high Score 4 results were encountered in biopsies with rejection, particularly T-cell-mediated rejection, which is an interstitial process that directly affects the parenchyma”. The authors further discuss that “injury in kidney and heart transplants is extensive immediately after transplant and regresses toward normal, and can reappear in severe rejection states”, a finding that is now being mirrored in the combined AlloMap/AlloSure experience (see below). Comparing renal and heart transplant biology, the authors state that “cardiac parenchyma is inherently more fragile than kidney and evokes a more inflammatory response. For example, TCMR in heart transplants is associated with parenchymal necrosis” [78].

Most important for the understanding of how this important work by the Molecular Microscope team on intragraft molecular systems biology has helped pave the way for the current non-invasive gold-standard of heart transplant rejection monitoring by the AlloMap/AlloSure combination summarized in the next paragraphs, is the authors’ conclusion that “the extensive injury changes in EMB and the association of these changes with reduced function adds a new dimension to our understanding of the clinical scenarios in heart transplants. The response to wounding is shared across tissues and species, as illustrated by the DAMP transcripts…Macrophage infiltration occurs within 3 days in injured organ isografts due to donation-implantation stress in the absence of allograft rejection, accompanied by parenchymal changes as a component of healing. Brain death has complex effects on cardiac hemodynamics and expression of inflammatory mediators, and has the potential to increase the immunogenicity of the heart and increase the probability of rejection…” The authors conclude that study limitations include lack of diastolic function parameters that may highlight additional clinical phenotypes, relationship between ischemic times and Score 4 injury scores in early postoperative biopsies, the absence of the source of injury other than rejection, persisting rejection-induced injury mistakenly called “refractory rejection” and causing unnecessary treatment [68,78].

The authors point out that the availability of a platform that can measure parenchymal injury opens opportunities to explore the inflammatory and injury phenotypes in primary heart diseases that diffusely affect the parenchyma, such as myocarditis, with the expectation that injury features will also probably correlate with impaired LVEF in such diseases, and could be useful in monitoring effects of treatment. Score 4 injury is expected to be associated with myocardial dysfunction because of myocyte response to injury and point towards a role of macrophages in human cardiac injury, repair, remodeling, and heart failure. Their discussion about the hypothetical mechanism how injury or death of cardiac myocytes attracts and activates macrophages, which then clear debris, promote healing, and potentially extend injury in some circumstances, making the macrophage a fundamental component of the cardiac response to wounding [78], leads directly into the rationale for the development of the original AlloMap concept [33].

Consequently, the authors state that “a key question for future studies is whether macrophages invading cardiac tissue in response to injury are merely associated with dysfunction, a contributor to dysfunction, or an important element in restoration of function and healing, and to define the mechanisms involved. The dualistic role of macrophages as both positive and negative agents involved in cardiac repair makes it difficult to draw actionable conclusions until these issues are resolved [78].

Based on the trajectory of the Molecular Microscope Project, CareDx, Inc. the maker of AlloMap and AlloSure, initiated a strategic partnership with NanoString to develop HistoMap, a gene expression profiling (GEP) solution to identify allograft rejection in transplant biopsy tissue in September 2019, utilizing NanoString’s nCounter® technology in conjunction with the newly introduced Human Organ Transplant panel, a 770-gene panel designed to evaluate the human immune response following organ transplantation through multimodality testing.

4 -. IMPLICATIONS OF INTRAGRAFT INJURY FOR NON-INVASIVE PATIENT-SPECIFIC INJURY BIOMARKERS: THE ALLOSURE PROJECT

The evolution of the Molecular Microscope project and renewed interest in different mechanisms and patterns of allograft injury, as reflected in a complementary key/lock pattern in the intragraft biology and peripheral blood mononuclear cell biology, led to incorporation of donor-derived Cell-free DNA termed AlloSure as complementary to AlloMap into a comprehensive non-invasive strategy. The pioneering work in the field, notably at Stanford, CareDx and NIH, took place over the last decade [44,79-85].

Since an organ transplant is also a genome transplant, the detection of allo-graft cell products and the underlying concept of the concept of comparing two genomes (termed by the authors the two genome method, implying that both recipient and donor genome were accessible or visible) called genome transplant dynamics (GTD) utilizes shotgun sequencing to determine informative genetic differences between the donor and recipient whereby, at a particular locus, the recipient ideally is homozygous for a single base and the donor is homozygous for a different base. In the initial clinical report, the percentage of donor-specific molecules was determined based on the total number of informative bases. In samples taken at the time of a biopsy-proven rejection event, the percentage of donor-specific single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) was increased to >3–4% during, or even immediately preceding, biopsy-proven rejection, which represented a significant increase in the amount of dd-cfDNA within the recipient’s blood in comparison to the percentage of dd-cfDNA within the recipient’s circulation in the absence of rejection which was <1% [44,83].

Since the difficulty and cost of establishing a pure reference donor genotype evolved as a major barrier to its widespread clinical implementation, a method that enables dd-cfDNA monitoring using shotgun sequencing without donor genotype information (termed by the authors one-genome method, implying that the recipient genome was accessible or visible while the donor genome was not accessible or hidden) was developed [86].

While these two versions of shotgun whole-genome sequencing have been used to detect and quantify dd-cfDNA, the complexity and cost of the analyses limited its application as a clinically relevant surveillance tool. To further develop a cost-effective method to quantify donor cfDNA in recipient plasma, a next methodological development step was based on using a panel of 124 high-frequency single nucleotide polymorphisms, next-generation (semiconductor) sequencing, and a novel mixture model algorithm [87]. Consecutively, a targeted amplification, next-generation sequencing assay (AlloSure®; CareDx, Inc.) has been analytically and clinically validated to quantify the percentage of dd-cfDNA in transplant recipients’ blood without the need for donor or recipient genotyping [81]. This assay uses 266 single-nucleotide polymorphisms to accurately quantify dd-cfDNA in transplant recipients without separate genotyping was analytically validated using 1117 samples comprising the National Institute for Standards and Technology Genome in a Bottle human reference genome, independently validated reference materials, and clinical samples. This assay termed AlloSure was able to quantify the fraction of dd-cfDNA in both unrelated and related donor-recipient pairs, reliably measure dd-cfDNA (limit of blank, 0.10%; limit of detection, 0.16%; limit of quantification, 0.20%) across the linear quantifiable range (0.2% to 16%) with across-run CVs of 6.8%. Precision was also evaluated for independently processed clinical sample replicates and was similar to across-run precision. Application of the assay to clinical samples from heart transplant recipients demonstrated increased levels of dd-cfDNA in patients with biopsy-confirmed rejection and decreased levels of dd-cfDNA after successful rejection treatment. This noninvasive clinical-grade sequencing assay is capable of being completed within 3 days, providing the practical turnaround time preferred for transplanted organ surveillance [81].

From the perspective of the developers of the Shotgun sequencing GTD method, this targeted-sequencing still suffers from a relatively high lower limit of detection (0.2% dd-cfDNA) and a relatively low upper limit of detection (25% dd-cfDNA) which, in their assessment, excludes application in liver, lung and bone marrow transplantation [79,85]. They conclude that Shotgun sequencing GTD has a larger dynamic range and is furthermore simultaneously informative of infection [88] and tissues-of-origin of cfDNA [89] and has a 0.33–0.5x cfDNA sequence coverage of the human genome sufficient to robustly quantify donor DNA at a cost of 40–60 USD [86].

From a clinical validity and utility perspective, donor-derived cell-free DNA (dd-cfDNA), detected in the blood of transplant recipients, has been proposed as a noninvasive marker of graft injury, which can be caused by various mechanisms including acute cellular ejection (ACR) as well as acute antibody-mediated rejection (AMR) and potentially conditions of over-immunosuppression such as myocarditis. Early dd-cfDNA studies were based on the hypothesis that acute rejection (AR) causes cell death in the allograft, which leads to increased levels of dd-cfDNA in the recipient’s bloodstream. Data from single-center studies have shown that elevated ddcfDNA levels can detect AR after heart transplantation (HT), and an increase in levels can occur before rejection is detected on endomyocardial biopsy [44,90,91].

The AlloSure assay was shown to detect ACR in kidney transplant in a prospective, multicenter trial [92]. First multi-center clinical results have been reported in HT [65,73]. The Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA-Outcomes AlloMap Registry (D-OAR) is an observational, prospective, multicenter registry that aimed to evaluate clinical outcomes in OHT recipients who were receiving regular allograft rejection surveillance. Venous blood was longitudinally sampled from 740 HT recipients from 26 US-centers. Plasma dd-cfDNA was quantified by using targeted amplification and sequencing of a single nucleotide polymorphism panel. The dd-cfDNA levels were correlated to paired events of biopsy-based diagnosis of rejection. The median dd-cfDNA was 0.07% in reference HT recipients (2164 samples) and 0.17% in samples classified as acute rejection (35 samples; P = .005). At a 0.2% threshold, dd-cfDNA had a 44% sensitivity to detect rejection and a 97% negative predictive value. In the cohort at risk for AMR (11 samples), dd-cfDNA levels were elevated 3-fold in AMR compared with patients without AMR (99 samples, P = .004). Interestingly, ACR grade 1R had a similar median level (0.08%) to grade 0 biopsies (0.07%), whereas ACR 2R (moderate) had a median dd-cfDNA level of 0.15%, and ACR 3R (severe) had a median dd-cfDNA level of 0.30%. dd-cfDNA levels differentiated ACR grade ≥ 2R (P = .004) from non-rejection samples. the PPV for ACR detection was 4.8% with an NPV of 98.6% [45]. In comparison, the NPV in the original CARGO-study developing the AlloMap test, was 99.2% [33].

5 -. PERSPECTIVES: MULTI-OMIC NON-INVASIVE PATIENT-SPECIFIC LONGITUDINAL QUIESCENCE- AND INJURY-MONITORING

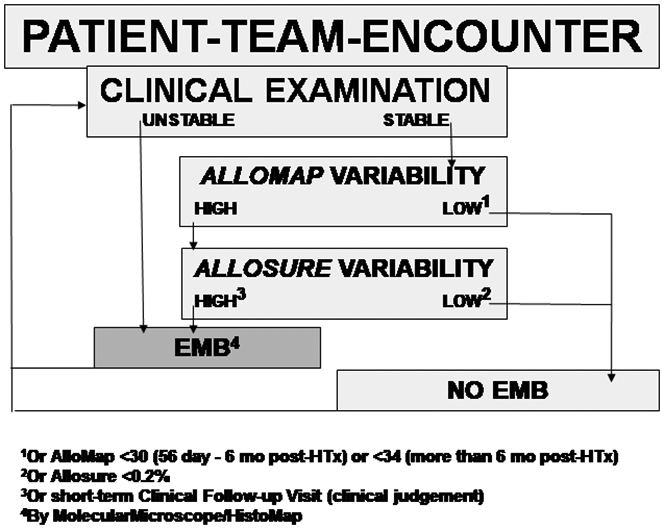

Integrating the AlloMap-based rejection rule-out function by monitoring the recipient’s immune system “quiescence” and the AlloSure-based injury rule-in function by monitoring the recipient’s graft injury pattern combines to a reliable non-invasive heart transplant rejection monitoring concept. First studies using the combined non-invasive strategy are being completed. In the evidence-based framework discussed in this review, the following proposed hypothetical algorithm (Figure 3) that needs to be tested in a randomized clinical trial design is represented by typical real-world (patients de-identified in original clinical AlloMap/AlloSure reports) clinical vignettes (Figure 4A-D).

Figure 3:

Proposed hypothetical algorithm (details see text).

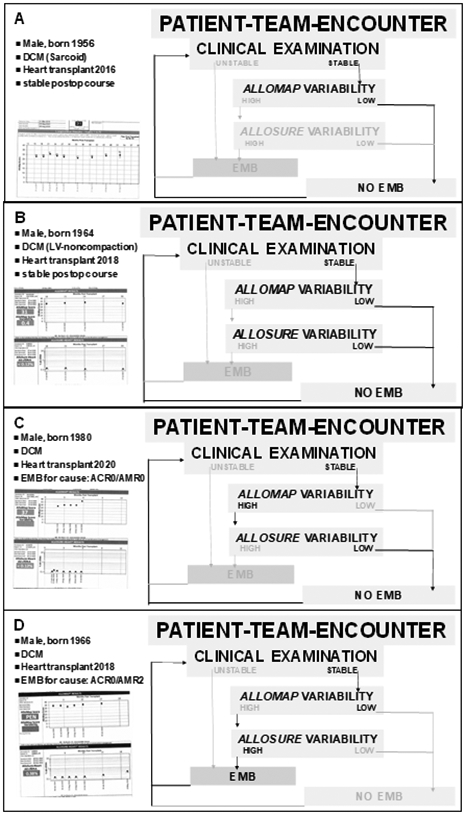

Figure 4:

Case vignettes (details see text).

In Figure 4A, non-invasive heart transplant rejection monitoring of a clinically stable patient based on current clinical recommendations using AlloMap without AlloSure is exemplified. It is important to note that the low AlloMap variability displayed in this patient is an important predictor of future clinical rejection and allograft dysfunction events.

In Figure 4B, non-invasive heart transplant rejection monitoring of a clinically stable patient based on current guidelines with AlloMap and, based on the results discussed in this review, additional myocardial allograft injury testing wit AlloSure, is summarized. In this example case, it is important to note that the AlloMap component ruling out concurrent and future rejection events is complemented by the AlloSure information making concurrent cardiac allograft injury from ANY CAUSE unlikely and therefore provides an additional – overlapping – safety net.

In Figure 4C, non-invasive heart transplant rejection monitoring of a clinically stable patient with the combination of AlloMap and AlloSure is displayed. In this case, the benefit of combined non-invasive monitoring with both, AlloMap and AlloSure, becomes even more apparent. While the AlloMap score and the AlloMap variability are rising, the AlloSure variability remains low, indicating no myocardial injury. Based on the combination data, the clinical conclusion was drawn to follow the patient without a for-cause EMB.

In Figure 4D, the power of the combined AlloMap/AlloSure monitoring becomes fully apparent. While the AlloMap score shows low variability, indicating absence of acute cellular rejection, the AlloSure variability is rising, suggesting myocardial injury from any cause. This constellation prompted a for-cause EMB, documenting antibody-mediated rejection (AMR2) which was then successfully treated.

In preparation for a randomized clinical trial testing the hypothesis that the algorithm summarized in Figure 3 is of higher clinical utility than the current non-invasive standard of care implemented following the randomized clinical trial conducted as IMAGE-study [34], since 2018, the combined monitoring with AlloMap and AlloSureHeart (termed HeartCare by CareDx) has been subjected to a large observational registry called Surveillance HeartCare® Outcomes Registry (SHORE). SHORE tests the primary hypothesis that prediction of the percentage of heart transplant patient who are alive at one, two and three years after heart transplantation can be optimized with the HeartCare strategy. The study design incudes a historical control group matched to the estimated 800 HeartCare group patients who complete at least two years of HeartCare surveillance use and inclusive of year 3 post-transplant clinical follow-up for outcome. The criteria for the matched controls is based on allograft donor type, age, sex, ethnicity/race, and other clinical factors using propensity score matching. One of the reasons why an observational study using propensity score matching requires a follow-up study such as an RCT for an unbiased assessment of the clinical utility effect is that propensity-score matching has the potential to increase model imbalance, inefficiency, model dependence, and bias [93].

6 -. EXPERT OPINION

The exciting evolution of heart transplant rejection diagnostics over the last quarter century allows to highlight specific aspects from my personal experience, having been involved in this process from the beginning:

It is deeply satisfying that the implementation of non-invasive monitoring of stable heart transplant recipients has improved heart transplant outcomes with significant improvement of quality of life while neither compromising the detection of acute rejection nor the probability of long-term survival.

The development of the AlloMap/AlloSure algorithm has paved the way for genomic precision medicine to become established in high tech modern medicine practice. The Institute of Medicine’s publication in 2012 highlights the translational science role model that the AlloMap Study Group provided for subsequent “omic” test development projects.

The successful completion of the AlloMap/AlloSure project provides a strong rationale for the clinical utility of Human Genome Project applications in major public health challenges such as advanced organ failure and cancer diagnostics.

The successful completion of the AlloMap/AlloSure project has helped redefine the collaborative “condition-sine-qua-non” network structure of interactions between academia, biotech industry, high risk venture capital and regulatory agencies. The societal discourse continues to unfold.

The AlloMap/AlloSure project provides a blue-print for the next generation of translational biomedical researchers. A research project examining the scientific process of “omic” test development termed “Science-in-the-making” has been initiated at UCLA.

As all paradigm-transforming concepts, the AlloMap/AlloSure project has initially been met with resistance in various domains. In my personal experience, these resistance domains obstacles are important to acknowledge as system level obstacles:

Scientific evidence concerns: The lack of a 1:1 translation of EMB-results into AlloMap/AlloSure results prompted an early skepticism of what was defined as acute cardiac allograft rejection and an associated reluctance to adopt the non-invasive practice algorithm. This skepticism eased over time with increasing practice experience and scientific data output.

Medico-legal concerns: In the early period of AlloMap implementation the argument “What if a false-negative AlloMap result leads to inappropriate under-treatment?” was raised. This concern eased with the publication of the AlloMap clinical utility data that suggested unnecessary and potentially harmful overtreatment of rejection episodes by up to 30% in the EMB-era.

Economic concerns: Several centers had initial concerns with respect to the reduced program income secondary to reduced EMB-reimbursement. Over time, this concern eased in light of the apparent clinical benefit of the non-invasive AlloMap/AlloSure strategy.

Center/investigator profile concerns: Initially, adoption of the non-invasive AlloMap/AlloSure strategy was – occasionally – hampered by heart transplant center team members who requested to be part of the research team and publications as prerequisite – and in order to facilitate - adoption of the clinical protocol.

Within the next five years, I anticipate the following projects to take shape:

Randomized clinical trial-testing of the added predictive power of the combined AlloMap/AlloSure variability score which is eagerly awaited by the international heart transplant community (Figure 3).

The expansion of this non-invasive testing concept A) to the early post-transplant period (day 1-56) during which AlloMap is not FDA-cleared and complementary GEP-approaches such as the HEARTBiT test by the University of British Columbia group of Bruce McManus have been proposed [94,95] and B) beyond single-organ transplantation which is being explored [72,96].

Interrogation of other nucleic acid molecules released from the transplanted organ including microRNAs, long non-coding RNA, and DNA-methylation patterns that are presently less well developed in comparison to cfDNA but may also represent potential novel biomarkers.

Key-lock pattern insights from genome/transcriptome patterns in combined biopsy/blood studies.

Cost-effectiveness studies with combined AlloMap/AlloSure-based monitoring in comparison to EMB-based and AlloMap-based monitoring that have already suggested benefits from the non-invasive approach [66,97].

“Big data” or artificial intelligence-based approach of post- transplant outcome prediction algorithms [28,98].

expansion of the multi-omics prediction algorithm technology including the use of artificial intelligence and network medicine strategies [99-102] to generalized advanced organ failure outcomes precision prediction of comparative survival benefit in one-genome settings, i.e. in persons with organ failure evaluated for various therapies including organ transplantation [89,103-109].

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS.

A novel complementary non-invasive heart transplant monitoring strategy based on leukocyte gene expression profiling and donor-derived cell-free DNA that incorporates longitudinal variability measures provides an exciting novel algorithm of heart transplant allograft monitoring. These are the key highlights of the development of this translational biomedical science project:

Twenty-five years of translational research timeline (Issue #1): It is a key insight in translational omic monitoring algorithm development to expect a A) multi-stakeholder/multi-expert, B) resource-intense, and C) standardized multi-stage consensus test development process.

Multi-omic prediction framework (Issue #2): It is a key insight that a combination of phenome, proteome, transcriptome and genome data provide superior diagnostic and predictive performance in comparison to single omic level algorithms.

Paradigm-challenging/transforming nature of the project (Issue #3): It is a key insight to anticipate the system challenges described below in undertaking this type of non-invasive algorithm development.

Research training model for research and clinical care (Issue #4): It is a key insight to appreciate the complementarity of the phenome, proteome, transcriptome and genome level not only in the non-invasive test development process, but also in clinical care.

Challenge for innovative cost-effectiveness and health economics metric development (Issue #5): The implementation of non-invasive monitoring provides a blueprint for novel longitudinal allograft outcomes studies.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the following philanthropic gifts to Mario Deng Advanced HF Research at Columbia University (Philip Geier, John Tocco and Robert Milo) and UCLA (Larry Layne, Juan Mulder, James and Candace Moose, Peter Schultz).

Funding

This paper was not funded.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

Mario C. Deng is co-founding equity holders of LeukoLifeDx, Inc., the developer of MyLeukoMAPTM biomarker test conceptualized in this manuscript. The author has no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Reviewers Disclosure

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

REFERENCES

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

* of interest

** of considerable interest

- 1.Clark DA, Schroeder JS, Griepp RB, et al. Cardiac transplantation in man. Review of first three years' experience. Am J Med. 1973. May;54(5):563–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caves PK, Stinson EB, Billingham ME, et al. Serial transvenous biopsy of the transplanted human heart. Improved management of acute rejection episodes. Lancet. 1974. May;1(7862):821–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Billingham ME, Cary NR, Hammond ME, et al. A working formulation for the standardization of nomenclature in the diagnosis of heart and lung rejection: Heart Rejection Study Group. The International Society for Heart Transplantation. J Heart Transplant. 1990. 1990 Nov-Dec;9(6):587–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stewart S, Winters GL, Fishbein MC, et al. Revision of the 1990 working formulation for the standardization of nomenclature in the diagnosis of heart rejection. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005. November;24(11):1710–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marboe CC, Billingham M, Eisen H, et al. Nodular endocardial infiltrates (Quilty lesions) cause significant variability in diagnosis of ISHLT Grade 2 and 3A rejection in cardiac allograft recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005. July;24(7 Suppl):S219–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crespo-Leiro MG, Zuckermann A, Bara C, et al. Concordance among pathologists in the second Cardiac Allograft Rejection Gene Expression Observational Study (CARGO II). Transplantation. 2012. December;94(11):1172–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khan H, Jaffar N, Rauramaa R, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness and nonfatalcardiovascular events: A population-based follow-up study. Am Heart J. 2017. February;184:55–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McMinn JF, Lang NN, McPhadden A, et al. Biomarkers of acute rejection following cardiac transplantation. Biomark Med. 2014;8(6):815–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raia F, Deng M. Relational Medicine: Person alizing Modern Healthcare: The Practice of High-Tech Medicine as a Relational Act. World Scientific; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baraldi-Junkins C, Levin HR, Kasper EK, et al. Complications of endomyocardial biopsy in heart transplant patients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1993. 1993 Jan-Feb;12(1 Pt 1):63–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mason JW. Techniques for right and left ventricular endomyocardial biopsy. The American journal of cardiology. 1978. May;41(5):887–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knosalla C, Grauhan O, Muller J, et al. Intramyocardial electrogram recordings (IMEG) for diagnosis of cellular and humoral mediated cardiac allograft rejection. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000. April;6(2):89–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park JW, Warnecke H, Deng M, et al. Early diastolic left ventricular function as a marker of acute cardiac rejection: a prospective serial echocardiographic study. Int J Cardiol. 1992. December;37(3):351–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lunze FI, Colan SD, Gauvreau K, et al. Tissue Doppler imaging for rejection surveillance in pediatric heart transplant recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013. October;32(10):1027–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Valantine HA. Rejection surveillance by Doppler echocardiography. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1993. 1993 May-Jun;12(3):422–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kindel SJ, Hsu HH, Hussain T, et al. Multimodality Noninvasive Imaging in the Monitoring of Pediatric Heart Transplantation. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2017. September;30(9):859–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Butler CR, Savu A, Bakal JA, et al. Correlation of cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging findings and endomyocardial biopsy results in patients undergoing screening for heart transplant rejection. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2015. May;34(5):643–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greenway SC, Dallaire F, Kantor PF, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of the transplanted pediatric heart as a potential predictor of rejection. World J Transplant. 2016. December;6(4):751–758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin F, Ou Y, Huang CZ, et al. Metabolomics identifies metabolite biomarkers associated with acute rejection after heart transplantation in rats. Sci Rep. 2017. November;7(1):15422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Almenar L, Arnau MA, Martínez-Dolz L, et al. Is there a correlation between brain naturietic peptide levels and echocardiographic and hemodynamic parameters in heart transplant patients? Transplant Proc. 2006. October;38(8):2534–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garrido IP, Pascual-Figal DA, Nicolás F, et al. Usefulness of serial monitoring of B-type natriuretic peptide for the detection of acute rejection after heart transplantation. The American journal of cardiology. 2009. April;103(8):1149–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahn KT, Choi JO, Lee GY, et al. Usefulness of high-sensitivity troponin I for the monitoring of subclinical acute cellular rejection after cardiac transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2015. March;47(2):504–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Erbel C, Taskin R, Doesch A, et al. High-sensitive Troponin T measurements early after heart transplantation predict short- and long-term survival. Transpl Int. 2013. March;26(3):267–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tarazón E, Ortega A, Gil-Cayuela C, et al. SERCA2a: A potential non-invasive biomarker of cardiac allograft rejection. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2017. December;36(12):1322–1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eisenberg MS, Chen HJ, Warshofsky MK, et al. Elevated levels of plasma C-reactive protein are associated with decreased graft survival in cardiac transplant recipients. Circulation. 2000. October;102(17):2100–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deng MC, Erren M, Kammerling L, et al. The relation of interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, IL-2, and IL-2 receptor levels to cellular rejection, allograft dysfunction, and clinical events early after cardiac transplantation. Transplantation. 1995. November 27;60(10):1118–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deng MC, Erren M, Roeder N, et al. T-cell and monocyte subsets, inflammatory molecules, rejection, and hemodynamics early after cardiac transplantation. Transplantation. 1998. May 15;65(9):1255–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bakir M, Jackson N, Han S, et al. Dynamic Phenomapping and HLA Class I and II Antibodies for Heart Transplant Outcomes. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. 2018;37(4):S416–S417. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reed EF, Demetris AJ, Hammond E, et al. Acute antibody-mediated rejection of cardiac transplants. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2006. February;25(2):153–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kennel PJ, Saha A, Maldonado DA, et al. Serum exosomal protein profiling for the non-invasive detection of cardiac allograft rejection. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2018. March;37(3):409–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang QF, Trenson S, Zhang ZY, et al. Urinary Proteomics in Predicting Heart Transplantation Outcomes (uPROPHET)-Rationale and database description. PloS one. 2017;12(9):e0184443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohen Freue GV, Meredith A, Smith D, et al. Computational biomarker pipeline from discovery to clinical implementation: plasma proteomic biomarkers for cardiac transplantation. PLoS Comput Biol. 2013. April;9(4):e1002963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deng MC, Eisen HJ, Mehra MR, et al. Noninvasive discrimination of rejection in cardiac allograft recipients using gene expression profiling. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2006. January;6(1):150–60.**Landmark paper reporting the clinical validity of peripheral blood mononuclear cell gene-expression profiling in heart transplant rejection diagnostics

- 34.Pham MX, Teuteberg JJ, Kfoury AG, et al. Gene-expression profiling for rejection surveillance after cardiac transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2010. May 20;362(20):1890–900.**Landmark paper reporting the clinical utility of peripheral blood mononuclear cell gene-expression profiling in heart transplant rejection diagnostics

- 35.Morita M, Chen J, Fujino M, et al. Identification of microRNAs involved in acute rejection and spontaneous tolerance in murine hepatic allografts. Sci Rep. 2014. October;4:6649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huo Q, Zhou M, Cooper DKC, et al. Circulating miRNA or circulating DNA-Potential biomarkers for organ transplant rejection. Xenotransplantation. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pattar SK, Greenway SC. Circulating nucleic acids as biomarkers for allograft injury after solid organ transplantation: current state-of-the-art. Transplant Research and Risk Management. 2019;11:17. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sukma Dewi I, Hollander Z, Lam KK, et al. Association of Serum MiR-142-3p and MiR-101-3p Levels with Acute Cellular Rejection after Heart Transplantation. PloS one. 2017;12(1):e0170842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bhatia AK, Phan JH, Mahle WT, et al. Identification of candidate MicroRNA as pathological markers of pediatric heart transplant rejection. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. 2015;34(4):S162. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wei L, Wang M, Qu X, et al. Differential expression of microRNAs during allograft rejection. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2012. May;12(5):1113–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang E, Nie Y, Zhao Q, et al. Circulating miRNAs reflect early myocardial injury and recovery after heart transplantation. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2013. July;8:165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Duong Van Huyen JP, Tible M, Gay A, et al. MicroRNAs as non-invasive biomarkers of heart transplant rejection. European heart journal. 2014. December;35(45):3194–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Di Francesco A, Fedrigo M, Santovito D, et al. MicroRNAs signature in heart transplant enhances diagnosis of different types of acute rejection. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. 2018;37(4):S39–S40. [Google Scholar]

- 44.De Vlaminck I, Valantine HA, Snyder TM, et al. Circulating cell-free DNA enables noninvasive diagnosis of heart transplant rejection. Science translational medicine. 2014. June;6(241):241ra77.**Landmark paper reporting the clinical validity of donor-derived cell-free DNA in heart transplant rejection diagnostics

- 45.Khush KK, Patel J, Pinney S, et al. Noninvasive detection of graft injury after heart transplant using donor-derived cell-free DNA: A prospective multicenter study. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2019. October;19(10):2889–2899.*Important multi-center paper reporting the clinical validity of donor-derived cell-free DNA in heart transplant rejection diagnostics

- 46.Deng MC, Baba HA, Erren M, et al. Can molecular techniques be applied to improve the endomyocardial biopsy diagnosis of acute rejection? Transplant Proc. 1998. May;30(3):881–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Deng MC, Bell S, Huie P, et al. Cardiac allograft vascular disease. Relationship to microvascular cell surface markers and inflammatory cell phenotypes on endomyocardial biopsy. Circulation. 1995. March;91(6):1647–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Deng MC, Cadeiras M, Reed EF. The multidimensional perspective of cardiac allograft rejection. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2013. October;18(5):569–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Valantine H, Johnson F, Dong C, et al. , editors. Cytokines as potential mediators of acute allograft diastolic dysfunction in cyclosporine-treated patients: a pilot study using in situ hybridization19945). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Deng MC. Detection of specific MRNA in formalin-fixed cardiac tissue by in-situ-hybridization with biotinylated oligonucleotides. J Histochem Cytochem. 1993;41:1121. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lander ES, Linton LM, Birren B, et al. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature. 2001. February;409(6822):860–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Venter JC, Adams MD, Myers EW, et al. The sequence of the human genome. Science. 2001. February;291(5507):1304–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dzau VJ, Ginsburg GS, Van Nuys K, et al. Aligning incentives to fulfil the promise of personalised medicine. Lancet. 2015. May;385(9982):2118–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Collins FS, Varmus H. A new initiative on precision medicine. N Engl J Med. 2015. February;372(9):793–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mensah GA, Kiley J, Mockrin SC, et al. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Strategic Visioning: setting an agenda together for the NHLBI of 2025. Am J Public Health. 2015. May;105(5):e25–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Deng MC. The AlloMap™ genomic biomarker story: 10 years after. Clinical Transplantation. 2017:e12900-n/a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Deng MC, Elashoff B, Pham MX, et al. Utility of Gene Expression Profiling Score Variability to Predict Clinical Events in Heart Transplant Recipients. Transplantation. 2014. January 31.**First report on gene expression variability measure to predict clinical outcomes in heart transplantation

- 58.Deng MC, Alexander G, Wolters H, et al. Low variability of intraindividual longitudinal leukocyte gene expression profiling cardiac allograft rejection scores. Transplantation. 2010. August;90(4):459–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Costanzo MR, Dipchand A, Starling R, et al. The International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation Guidelines for the care of heart transplant recipients. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. 2010;29(8):914–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cornell LD, Smith RN, Colvin RB. Kidney transplantation: mechanisms of rejection and acceptance. Annu Rev Pathol. 2008;3:189–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lehmann-Werman R, Neiman D, Zemmour H, et al. Identification of tissue-specific cell death using methylation patterns of circulating DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016. March;113(13):E1826–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Halloran PF, Reeve J, Kaplan B. Lies, damn lies, and statistics: the perils of the P value. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2006. January;6(1):10–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Deng MC, Eisen HJ, Mehra MR. Methodological challenges of genomic research--the CARGO study. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2006. May;6(5 Pt 1):1086–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Starling RC, Pham M, Valantine H, et al. Molecular testing in the management of cardiac transplant recipients: initial clinical experience. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2006. December;25(12):1389–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Crespo-Leiro MG, Stypmann J, Schulz U, et al. Clinical usefulness of gene-expression profile to rule out acute rejection after heart transplantation: CARGO II. European heart journal. 2016. September;37(33):2591–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Evans RW, Williams GE, Baron HM, et al. The economic implications of noninvasive molecular testing for cardiac allograft rejection. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2005. June;5(6):1553–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pham MX, Deng MC, Kfoury AG, et al. Molecular testing for long-term rejection surveillance in heart transplant recipients: design of the Invasive Monitoring Attenuation Through Gene Expression (IMAGE) trial. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2007. August;26(8):808–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jarcho JA. Fear of rejection--monitoring the heart-transplant recipient. N Engl J Med. 2010. May;362(20):1932–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mehra MR, Parameshwar J. Gene expression profiling and cardiac allograft rejection monitoring: is IMAGE just a mirage? J Heart Lung Transplant. 2010. June;29(6):599–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mehra MR, Canter CE, Hannan MM, et al. The 2016 International Society for Heart Lung Transplantation listing criteria for heart transplantation: A 10-year update. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2016. January;35(1):1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kobashigawa J, Patel J, Azarbal B, et al. Randomized pilot trial of gene expression profiling versus heart biopsy in the first year after heart transplant: early invasive monitoring attenuation through gene expression trial. Circ Heart Fail. 2015. May;8(3):557–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Moayedi Y, Foroutan F, Miller RJH, et al. Risk evaluation using gene expression screening to monitor for acute cellular rejection in heart transplant recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2019. January;38(1):51–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Crespo-Leiro M, Zuckermann A, Stypmann J, et al. Increased Plasma Levels of Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA Correlate With Rejection in Heart Transplant Recipients: The CARGO II Multicenter Trial. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. 2015;34(4):S31–S32. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Committee on the Review of Omics-Based Tests for Predicting Patient Outcomes in Clinical Trials BoHCS, Board on Health Sciences Policy, Institute of Medicine. Evolution of Translational Omics: Lessons Learned and the Path Forward. In: Micheel CM, Nass SJ, Omenn GS, editors. Evolution of Translational Omics: Lessons Learned and the Path Forward. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2012. p. 33–63.*Important monograph outlining developmental standards in omic diagnostic test development

- 75.Mengel M, Sis B, Kim D, et al. The molecular phenotype of heart transplant biopsies: relationship to histopathological and clinical variables. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2010. September;10(9):2105–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Halloran PF, Potena L, Van Huyen JD, et al. Building a tissue-based molecular diagnostic system in heart transplant rejection: The heart Molecular Microscope Diagnostic (MMDx) System. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2017. November;36(11):1192–1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Halloran PF, Venner JM, Famulski KS. Comprehensive Analysis of Transcript Changes Associated With Allograft Rejection: Combining Universal and Selective Features. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2017. July;17(7):1754–1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Halloran PF, Reeve J, Aliabadi AZ, et al. Exploring the cardiac response to injury in heart transplant biopsies. JCI Insight. 2018. October;3(20).**Landmark paper reporting molecular injury phenotype as distinct pattern in heart transplant rejection diagnostics

- 79.De Vlaminck I, Martin L, Kertesz M, et al. Noninvasive monitoring of infection and rejection after lung transplantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015. October;112(43):13336–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gielis EM LK, De Winter BY, Del Favero J, Bosmans JL, Claas FH, Abramowicz D, Eikmans M. Cell-Free DNA: An Upcoming Biomarker in Transplantation. American Journal of Transplantation. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Grskovic M, Hiller DJ, Eubank LA, et al. Validation of a Clinical-Grade Assay to Measure Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients. J Mol Diagn. 2016. November;18(6):890–902.*Important paper reporting the analytical and clinical validity of donor-derived cell-free DNA in heart transplant rejection diagnostics

- 82.Kobashigawa J, Grskovic M, Dedrick R, et al. Increased Plasma Levels of Graft-Derived Cell-Free DNA Correlate with Rejection in Heart Transplant Recipients. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. 2014;33(4):S14. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Snyder TM, Khush KK, Valantine HA, et al. Universal noninvasive detection of solid organ transplant rejection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011. April;108(15):6229–34.**Landmark paper reporting the proof-of-concept using donor-derived cell-free DNA in organ transplant rejection diagnostics

- 84.Agbor-Enoh S, Tunc I, De Vlaminck I, et al. Applying rigor and reproducibility standards to assay donor-derived cell-free DNA as a non-invasive method for detection of acute rejection and graft injury after heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2017. September;36(9):1004–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Beck J, Bierau S, Balzer S, et al. Digital droplet PCR for rapid quantification of donor DNA in the circulation of transplant recipients as a potential universal biomarker of graft injury. Clin Chem. 2013. December;59(12):1732–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sharon E, Shi H, Kharbanda S, et al. Quantification of transplant-derived circulating cell-free DNA in absence of a donor genotype. PLoS Comput Biol. 2017. August;13(8):e1005629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gordon PM, Khan A, Sajid U, et al. An Algorithm Measuring Donor Cell-Free DNA in Plasma of Cellular and Solid Organ Transplant Recipients That Does Not Require Donor or Recipient Genotyping. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2016;3:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.De Vlaminck I, Khush KK, Strehl C, et al. Temporal response of the human virome to immunosuppression and antiviral therapy. Cell. 2013. November;155(5):1178–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Snyder MW, Kircher M, Hill AJ, et al. Cell-free DNA Comprises an In Vivo Nucleosome Footprint that Informs Its Tissues-Of-Origin. Cell. 2016. January 14;164(1-2):57–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hidestrand M, Tomita-Mitchell A, Hidestrand PM, et al. Highly sensitive noninvasive cardiac transplant rejection monitoring using targeted quantification of donor-specific cell-free deoxyribonucleic acid. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014. April;63(12):1224–1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Beck J, Oellerich M, Schulz U, et al. Donor-Derived Cell-Free DNA Is a Novel Universal Biomarker for Allograft Rejection in Solid Organ Transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2015. October;47(8):2400–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bloom RD, Bromberg JS, Poggio ED, et al. Cell-Free DNA and Active Rejection in Kidney Allografts. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017. July;28(7):2221–2232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.King G NR. Why propensity scores should not be used for matching. Political Analysis. 2019;27(4):435–454. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Shannon CP, Hollander Z, Dai DLY, et al. HEARTBiT: A Transcriptomic Signature for Excluding Acute Cellular Rejection in Adult Heart Allograft Patients. Can J Cardiol. 2020. August;36(8):1217–1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kim JV, Lee B, Koitsopoulos P, et al. Analytical Validation of HEARTBiT: A Blood-Based Multiplex Gene Expression Profiling Assay for Exclusionary Diagnosis of Acute Cellular Rejection in Heart Transplant Patients. Clin Chem. 2020. August;66(8):1063–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Carey SA, Tecson KM, Jamil AK, et al. Gene expression profiling scores in dual organ transplant patients are similar to those in heart-only recipients. Transpl Immunol. 2018. August;49:28–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hollander Z MT, Assadian S, et al. Cost - effectiveness of a blood - based biomarker compared to endomyocardial biopsy for the diagnosis of acute allograft rejection [abstract]. Journal of Heart Lung Transplant. 2016;35(4):[Abstract]. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Loupy A, Aubert O, Orandi BJ, et al. Prediction system for risk of allograft loss in patients receiving kidney transplants: international derivation and validation study. BMJ. 2019. September;366:l4923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Benincasa G, Mansueto G, Napoli C. Fluid-based assays and precision medicine of cardiovascular diseases: the 'hope' for Pandora's box? J Clin Pathol. 2019. December;72(12):785–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Benincasa G, Marfella R, Della Mura N, et al. Strengths and Opportunities of Network Medicine in Cardiovascular Diseases. Circulation journal : official journal of the Japanese Circulation Society. 2020. January;84(2):144–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Silverman EK, Schmidt HHHW, Anastasiadou E, et al. Molecular networks in Network Medicine: Development and applications. Wiley interdisciplinary reviews Systems biology and medicine. 2020. April:e1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Napoli C, Benincasa G, Donatelli F, et al. Precision medicine in distinct heart failure phenotypes: Focus on clinical epigenetics. Am Heart J. 2020. June;224:113–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Shahzad K, Fatima A, Cadeiras M, et al. Challenges and solutions in the development of genomic biomarker panels: a systematic phased approach. Current genomics. 2012. June;13(4):334–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bondar G, Cadeiras M, Wisniewski N, et al. Comparison of whole blood and peripheral blood mononuclear cell gene expression for evaluation of the perioperative inflammatory response in patients with advanced heart failure. PloS one. 2014;9(12):e115097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Bondar G, Xu W, Elashoff D, et al. Comparing NGS and NanoString platforms in peripheral blood mononuclear cell transcriptome profiling for advanced heart failure biomarker development. Journal of Biological Methods; Vol 7, No 1 (2020). 2020 January/03/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bondar G, Togashi R, Cadeiras M, et al. Association between preoperative peripheral blood mononuclear cell gene expression profiles, early postoperative organ function recovery potential and long-term survival in advanced heart failure patients undergoing mechanical circulatory support. PloS one. 2017;12(12):e0189420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wisniewski N, Bondar G, Rau C, et al. Integrative model of leukocyte genomics and organ dysfunction in heart failure patients requiring mechanical circulatory support: a prospective observational study. BMC Med Genomics. 2017. August 29;10(1):52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Deng MC. A peripheral blood transcriptome biomarker test to diagnose functional recovery potential in advanced heart failure. Biomark Med. 2018. June;12(6):619–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Deng MC. Multi-dimensional COVID-19 short-and long-term outcome prediction algorithm. Taylor & Francis; 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]