Abstract

Fatty acid β‐oxidation (FAO) and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) are mitochondrial redox processes that generate ATP. The biogenesis of the respiratory Complex I, a 1 MDa multiprotein complex that is responsible for initiating OXPHOS, is mediated by assembly factors including the mitochondrial complex I assembly (MCIA) complex. However, the organisation and the role of the MCIA complex are still unclear. Here we show that ECSIT functions as the bridging node of the MCIA core complex. Furthermore, cryo‐electron microscopy together with biochemical and biophysical experiments reveal that the C‐terminal domain of ECSIT directly binds to the vestigial dehydrogenase domain of the FAO enzyme ACAD9 and induces its deflavination, switching ACAD9 from its role in FAO to an MCIA factor. These findings provide the structural basis for the MCIA complex architecture and suggest a unique molecular mechanism for coordinating the regulation of the FAO and OXPHOS pathways to ensure an efficient energy production.

Keywords: ACAD9, Cryo-EM, deflavination, FAD, mitochondrial complex I assembly complex

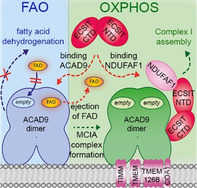

Fatty acid oxidation (FAO) and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) are key mitochondrial pathways for cellular energetics. However, the crosstalk between them is unclear. We show that the molecular architecture of the mitochondrial Complex I assembly (MCIA) complex, required for Complex I biogenesis and thereby for activation of OXPHOS, implies an allosteric deflavination mechanism that shuts down FAO.

Introduction

Mitochondria coordinate central functions in the cell and have a crucial role in energy metabolism. Fatty acid β‐oxidation (FAO) and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) are mitochondrial enzymatic pathways responsible for coupling redox reactions to ATP production. [1] The OXPHOS system, composed of the respiratory chain components embedded in the mitochondrial inner membrane, includes five multimeric enzymes, the first of which is Complex I (CI or NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase). [2] The redox reactions involved in ATP production generate reactive oxygen species (ROS), which have important roles in cell signalling and homeostasis but also cause oxidative damage to DNA, lipids and proteins including those in the respiratory chain itself. As the first enzyme of the respiratory chain, CI is the main source and target of ROS [3] and deficiencies in CI activity, which are often characterized by defects in the CI assembly process,[ 4 , 5 ] lead to the most common OXPHOS disorders in humans. [6] Mammalian CI is the largest (≈1 MDa) membrane protein complex, composed of 44 different subunits encoded by the nuclear and the mitochondrial genome. [7] While the atomic structure of CI is known,[ 7 , 8 , 9 ] the mechanisms of CI biogenesis involving the coordinated assembly of intermediate modules and insertion of cofactors to form a functional complex remain elusive.[ 10 , 11 ] CI biogenesis is assisted by assembly factors that ultimately dissociate from the final holoenzyme. [10]

The mitochondrial CI assembly (MCIA) complex has been recently described and is believed to participate in the assembly of early CI intermediate modules.[ 10 , 11 ] The MCIA complex itself is composed of three core subunits—NDUFAF1, ACAD9 and ECSIT—which seem to further associate with other membrane proteins such as TMEM126B, TIMMDC1, TMEM186 and COA1.[ 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 ] Knockdown of any of the core MCIA proteins in cultured cells leads to decreased levels of the other two partners and results in impaired CI assembly and activity.[ 14 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 ] However, the molecular details underlying the activity of the MCIA complex are unclear, partly because as well as participating in CI maturation, the individual components of the MCIA complex are also involved in other cellular functions.[ 21 , 22 ] Here, ECSIT, which is predicted to contain an ordered N‐terminal domain followed by a disordered C‐terminal region, [21] was initially identified as a cytoplasmic and nuclear signalling protein[ 23 , 24 ] while ACAD9 was annotated as an acyl‐CoA dehydrogenase (ACAD) enzyme due to its sequence homology with the very long chain acyl‐CoA dehydrogenase VLCAD, [14] which initiates the FAO pathway with the concurrent reduction of its FAD cofactor. [25] Although the biological relevance of ACAD9 function as a FAO enzyme has been controversial,[ 26 , 27 ] recent findings suggest physical interactions between FAO and OXPHOS proteins. [28] Molecular insights into the protein interactions linking these two pathways are thus crucial for understanding the pathogenesis of diseases entailing OXPHOS and FAO deficiencies, such as Alzheimer's disease (AD), with considerable evidence indicating a strong association between CI activity and amyloid‐beta (Aβ) toxicity. [29] Noteworthy, ECSIT has been identified as a molecular node interacting with enzymes producing Aβ,[ 30 , 31 ] implying a potential role in AD pathogenesis.

In this study, we provide the molecular characterisation of ECSIT as an interacting node of the MCIA complex together with the 3D architecture of C‐terminal ECSIT with ACAD9. We also report a novel deflavination mechanism mediated by ECSIT that antagonises ACAD9 enzymatic activity, switching ACAD9 from a role as an FAO enzyme to a CI assembly factor. Taken together, our results provide insights into MCIA complex biogenesis and suggest a possible mechanism for coordinating the regulation between OXPHOS and FAO protein complexes to ensure an efficient energy production.

Results

ECSIT is the bridging component of the MCIA complex

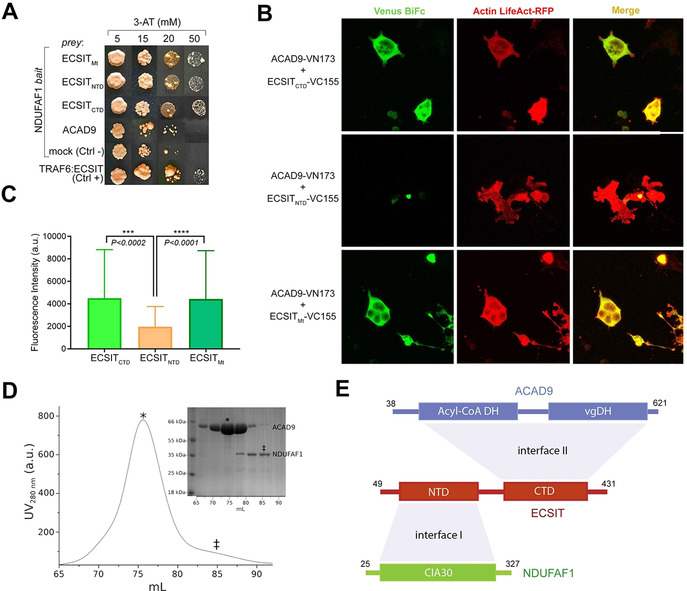

We examined the interactions between three MCIA complex core components NDUFAF1, ACAD9 and ECSIT in cellulo by yeast two‐hybrid (Y2 H) (Figure 1 A) and mammalian cell bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) (Figure 1 B,C) assays. While mitochondrial ECSIT (residues 49–431), as well as individual N‐ and C‐terminal fragments (ECSITNTD and ECSITCTD respectively, described below) were found to associate with NDUFAF1 (Figure 1 A), only ECSITCTD showed interaction with ACAD9 (Figure 1 B,C). No direct interaction between NDUFAF1 and ACAD9 was observed (Figure 1 A), as confirmed by in vitro interaction analysis with recombinant purified proteins (Figure 1 D).

Figure 1.

Identification of protein–protein interactions within the MCIA core complex. A) Y2H assays (NDUFAF1 as bait, different ECSIT and ACAD9 constructs as prey) indicate direct interactions between NDUFAF1 and mitochondrial (Mt, residues 49–431), N‐terminal domain (NTD, residues 49–252) or C‐terminal domain (CTD, residues 246–431) ECSIT constructs. No interaction is detected between NDUFAF1 and ACAD9. ECSIT and TRAF6 interaction was used as a positive control. B) BiFC assays in HEK293 human cells. Active reassembly of Venus (green signal) indicates that mitochondrial ECSIT (VC155‐ECSITMt) and the ECSIT C‐terminal domain (VC155‐ECSITCTD) interact with ACAD9 (ACAD9‐VN173). Red immunofluorescence from filamentous actin (LifeAct‐RFP) was used as a cell marker. Overlapping signals (yellow) confirm cells with positive interacting partners. C) Quantification of the signal using the FITC (green spectrum) or CY3.5 (red spectrum) filter settings. D) SEC chromatogram showing that ACAD9 (*) elutes as single peak separated from NDUFAF1 (≠), which suggests the absence of interaction between ACAD9 and NDUFAF1, as observed in Y2H assays. E) Domain interaction organization of MCIA complex proteins. ECSIT‐interacting interface regions with NDUFAF1 (I) and ACAD9 (II) respectively are shown in light grey. DH: dehydrogenase domain; vgDH: vestigial DH domain; CIA30: Complex I intermediate‐associated protein 30 domain.

The above observations suggest that ECSIT carries independent interaction sites for NDUFAF1 and ACAD9 (Figure 1 E). We therefore attempted to further examine the interaction of ECSIT with either ACAD9 or NDUFAF1. Here, the tendency of mitochondrial ECSIT purified from recombinant bacteria to form soluble aggregates (Figure S1) motivated us to apply ESPRIT (Expression of Soluble Proteins by Random Incremental Truncation) technology [32] in order to identify soluble and monodisperse ECSIT fragments (Figure S2). Whereas all N‐terminal fragments were insoluble, a C‐terminal fragment (ECSITCTD, residues 248–431) showed high expression and solubility (Figure S2). Interestingly, this fragment corresponds to the isoform ECSIT‐3, [23] an alternative splicing variant that has been observed at the transcript level. [24] Analyses of purified ECSITCTD both by size‐exclusion chromatography (SEC) coupled to multi‐angle laser light scattering (SEC‐MALLS) (Figure S3) and by small‐angle X‐ray scattering (SAXS) (Figure S4A, Table S1) yielded an approximate molecular mass of 46 kDa, suggesting that ECSITCTD is predominantly a dimer in solution. SAXS and 2D NMR data (Figure S4A, B) indicated that these dimers are elongated and only partially folded, consistent with the prediction of a highly disordered domain. Native mass spectrometry (native MS) confirmed that ECSITCTD forms dimers and revealed that these may further associate into tetramers and higher‐order multimers (Figure S4C).

Purified mature NDUFAF1 (residues 25–327) behaved as a monodisperse monomer in SEC‐MALLS and SAXS experiments (Figure S3, Table S1) whereas, in agreement with a previous study, [25] recombinant, purified ACAD9 (residues 38–621) was detected as a monodisperse homodimer by SEC‐MALLS (Figure S3). Negative‐stain electron microscopy (ns‐EM) (Figure S5A, B) and SAXS analysis (Figure S5B, Table S1) of ACAD9 revealed compact, rectangular envelopes (Figure S5A) consistent with a previously reported homology model of the ACAD9 dimer. [14] This model is based on the crystal structure of VLCAD, with which ACAD9 shares 47 % sequence identity (Figure S5B–D). Notably, SEC‐MALLS highlighted that VLCAD and ACAD9 share similar molecular weights but different elution profiles (Figure S5C), suggesting that ACAD9 occupies a larger hydrodynamic volume. A SAXS structural comparison confirmed that VLCAD folds into a more close‐packed conformation in solution (Figure S5D, Table S1).

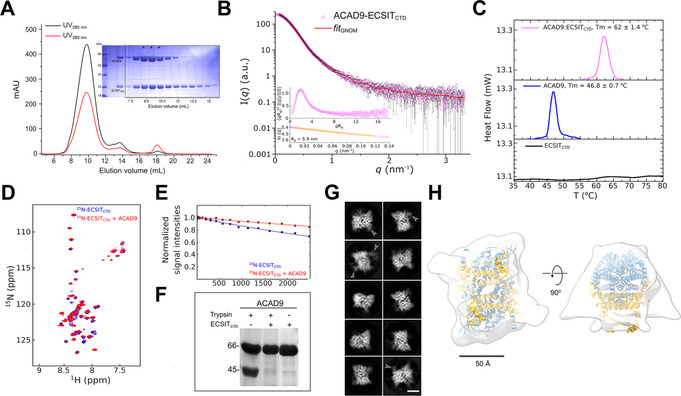

ECSITCTD forms a stable complex with ACAD9

In contrast to the interaction observed by Y2H (Figure 1 A), ECSITCTD did not bind NDUFAF1 in electrophoretic mobility shift assays (Figure S6A), suggesting that the N‐terminal domain of ECSIT is required for a high‐affinity interaction with NDUFAF1. Conversely, we were able to reconstitute a complex between ECSITCTD and ACAD9 (ACAD9‐ECSITCTD) in vitro that remained stably associated during SEC (Figure 2 A) and electrophoretic mobility shift assays (Figure S6B). Moreover, differential scanning calorimetry experiments showed that the presence of ECSITCTD (which has a poorly defined melting profile) enhanced the thermostability of ACAD9 by >15 °C (Figure 2 C).

Figure 2.

ECSITCTD forms a stable complex with ACAD9. A) SEC elution profile of the complex and loaded onto an SDS‐PAGE (*), showing a small adjacent peak of unbound ECSITCTD. B) SAXS scattering curve for the complex, with the GNOM fitting curve in red. Inset: normalized Kratky plot and close‐up of the Guinier region used to estimate the radius of gyration (Rg in nm) of the complex. C) Thermal denaturation profiles of ECSITCTD, ACAD9 and their complex determined by differential scanning calorimetry. Estimated T m values are indicated. A clear unfolding transition was not detected for ECSITCTD. D) 2D‐NMR interaction experiments of 15N‐labelled ECSITCTD and unlabelled ACAD9. Superimposed 1H‐15N correlation spectra of free ECSITCTD and ECSITCTD in complex with ACAD9 are shown in blue and red, respectively, in the region 8.5–7.5 1H ppm in the proton dimension. This highlights chemical shift perturbations in 11 out of 60 detected peaks in the amide region, indicating that ACAD9 interacts specifically with a few residues of ECSITCTD. E) 15N‐filtered DOSY‐NMR measurements on 15N‐ECSITCTD and ACAD9‐15N‐ECSITCTD complex. The exponential decay curves of ECSITCTD, in the absence and in the presence of ACAD9 are shown in blue and red, respectively. The units on the y‐axis are normalized values of the integrals of the signal measured in the amide proton region. The slower translational diffusion coefficient of ECSITCTD measured in the presence of ACAD9 is also consistent with ECSITCTD being part of an object larger than a single dimer (i.e. >40 kDa in size). F) Enhanced trypsin resistance of ACAD9 in the presence of ECSITCTD. ACAD9 subjected to trypsin digestion in the absence of ECSITCTD shows a 45 kDa proteolytic fragment. In contrast, ACAD9 is protected from proteolysis in the presence of ECSITCTD, further confirming the formation of a stable complex between ACAD9 and ECSITCTD. All proteolytic fragments are resolved by SDS‐PAGE. G) Selected cryo‐EM 2D class averages of the ACAD9‐ECSITCTD complex reveal a compact rectangular core with visible secondary structural features. Diffuse densities at defined locations on the ACAD9 core are indicated with arrowheads. Scale bar=50 Å. H) Top and side views of the 15 Å resolution cryo‐EM envelope of the ACAD9‐ECSITCTD complex displayed at low thresholds. The VLCAD‐based homology model of ACAD9 is fitted in the density, with dehydrogenase domains and the C‐terminal linker and vestigial domains shown in blue and gold, respectively. Scale bar=50 Å.

The stability of the ACAD9‐ECSITCTD interaction was further confirmed by the protection of ACAD9 from proteolytic cleavage upon ECSITCTD binding (Figure 2 F). However, SAXS analysis revealed a large molecular volume for the ACAD9‐ECSITCTD complex, implying a dynamic assembly process (Figure 2 B). Consistent with this finding, NMR analysis of 15N‐labelled ECSITCTD showed that the domain's random coil region remains largely unperturbed upon the addition of ACAD9, although a number of shift perturbations in the HSQC spectrum (Figure 2 D,E) suggests that ACAD9 interacts with specific residues within the ECSITCTD fragment. NDUFAF1 was unable to co‐elute with the ACAD9‐ECSITCTD complex (Figure S6C), consistent with the earlier observation that the N‐terminal domain of ECSIT is required for a high‐affinity interaction with NDUFAF1.

Cryo‐EM analysis of the ACAD9‐ECSITCTD complex

We next investigated the structure of the ACAD9‐ECSITCTD complex by cryo‐electron microscopy (cryo‐EM) (Figure S7). Analysis of the 2D class averages (Figure 2 G) showed a strongly preferred orientation and revealed that the complex possesses a defined core with visible secondary structural features. While this core clearly corresponds to the ACAD9 dimer, consistent with the ns‐EM map (Figure S5B), some classes also show diffuse densities at the periphery of this core (Figure 2 G, white arrows), which we tentatively attribute to the largely unfolded parts of ECSITCTD. A standard image processing procedure aimed for higher resolution reconstruction would result in masking out these peripheral densities while focusing on the compact core. Here however, we first chose not to use a mask in order to obtain low resolution information on the global shape of the ACAD9‐ECSITCTD complex and define the ECSITCTD binding site. Comparison of the resulting 3D reconstruction with the ns‐EM map and the VLCAD‐based homology model of ACAD9 suggests that the extra densities that protrude out of the central ACAD9 dimer core may correspond to ordered segments of ECSITCTD (Figure 2 H, Figure S5B). The fact that only a small proportion of the bound ECSITCTD is visible in the cryo‐EM density is compatible with the NMR data (Figure 2 D), indicating that the disorder of ECSITCTD is mostly retained upon ACAD9 binding. Analysis of the sample used for cryo‐EM by native MS confirmed the presence of ECSITCTD in the complex, revealing two major species of mass 197.5 kDa and 219.45 kDa (Figure S8B), in contrast to a mass of 132 kDa for the ACAD9 homodimer (Figure S8A). These correspond to an ACAD9 dimer bound to 3 or 4 ECSITCTD monomers, respectively, suggesting that each ACAD9 monomer can bind either a monomer or dimer of ECSITCTD.

ECSIT recognises the vestigial dehydrogenase domain of ACAD9

ACAD9 comprises an N‐terminal dehydrogenase domain and a C‐terminal region, which, based on homology with VLCAD, includes: (i) a solvent exposed linker (residues 445–482) showing low sequence conservation with VLCAD; (ii) a vestigial domain (residues 493–587) that appears to have arisen by duplication of the N‐terminal domain but which has lost its catalytic activity;[ 14 , 33 ] (iii) a C‐terminal helix that stabilizes the homodimer (residues 588–621) (Figure S9A). Previous studies postulated that the solvent exposed linker was responsible for the ability of ACAD9, but not VLCAD, to participate in Cl assembly,[ 14 , 34 ] raising the possibility that this region might interact with ECSIT. Interestingly however, the densities tentatively attributed to ECSITCTD in our cryo‐EM map protrude from a different region of ACAD9 (Figure 2 H) formed by two structural elements within the vestigial dehydrogenase domain: a helix‐turn‐helix (residues 554–560) and a loop (residues 488–496) [14] (Figure S9, regions 1 and 2 respectively). Interestingly, both regions are highly conserved across ACAD9 orthologues and, independently, across VLCAD orthologues but are highly divergent between these two proteins (Figure S9B).

In order to test whether the helical stretch of ACAD9 (residues 445–482) located nearby the vestigial domain in the homology model (Figure S9A, highlighted in grey) is also important for binding ECSIT, [14] we designed and purified a chimeric protein, hereafter named ACAD9VLCAD, by replacing this stretch by the equivalent region of VLCAD (Figure S10A). SEC‐SAXS analysis showed that the global conformation of ACAD9VLCAD is similar to ACAD9 (Table S1). However, the chimera is still able to co‐elute with ECSITCTD (Figure S10C), in contrast to VLCAD (Figure S11C), confirming that the identity of the residues within this region is not required for the interaction with ECSIT (Figure S9A)

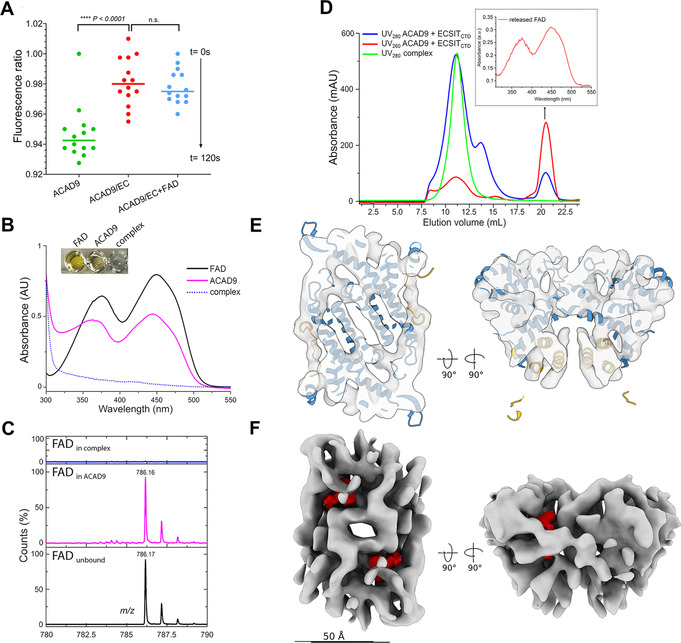

ECSIT induces the deflavination of ACAD9

To verify whether ECSITCTD affects the enzymatic activity of ACAD9, we analysed the acyl‐CoA dehydrogenase activity of ACAD9 alone and in complex with ECSITCTD. While purified homodimeric ACAD9 bound the FAD cofactor as expected [35] (Figure S12), its acyl‐CoA dehydrogenase activity was heavily impaired when bound to ECSITCTD (Figure 3 A). In contrast, the acyl‐CoA activity of VLCAD was not significantly altered in the presence of ECSITCTD, further confirming that ECSIT specifically interacts with ACAD9 (Figure S11A, B). Intriguingly, chimeric ACAD9VLCAD showed a perturbed FAD oxidation state that correlates with a reduced enzymatic activity (Figure S10A, B), suggesting that one or more specific residues within the helical region are important for catalytic efficiency.

Figure 3.

ECSIT induces the deflavination of ACAD9. A) Acyl‐CoA dehydrogenase (ACAD) activity of ACAD9 (in green) and the ACAD9‐ECSITCTD complex either in absence (red) or in presence (blue) of externally supplied FAD as determined by an ETF fluorescence reduction assay. After addition of the ACAD specific substrate palmitoyl‐CoA (C16:0), there is a clear loss of ETF fluorescence in ACAD9 alone but not in complex with ECSITCTD, over 120 s of reaction measurement. The addition of an excess of FAD to the reaction mixture containing the ACAD9‐ECSITCTD complex fails to rescue catalytic activity. B) UV visible spectra (FAD absorption region only) of free FAD (black), ACAD9 (magenta) and ACAD9‐ECSITCTD (blue dotted line) in the FAD absorption region. Inset: the coloured appearance of the different samples. C) ESI MS spectra recorded in the 780–790 m/z region showing free FAD standard as control (in black, observed m/z 786.17 Da), FAD released from ACAD9 (in magenta, observed m/z 786.16 Da) and absence of FAD signal in the ACAD9‐ECSITCTD complex (in blue). D) Release of FAD from the ACAD9 catalytic pocket upon reconstitution of the ACAD9‐ECSITCTD complex. Chromatographic elution profiles of the ACAD9‐ECSITCTD complex reconstituted upon mixing ACAD9 and ECSITCTD. A UV280nm peak at 21 mL (blue line, arrow) is visible, in contrast to the chromatography profile of the co‐purified complex with a single elution peak (green). The higher absorbance at UV260nm (red line) suggests that it corresponds to the FAD released from the reconstituted complex. Inset: UV visible spectra of the peak contents confirming the presence of FAD. E) Slices through the top (left) and side (right) views of the cryo‐EM reconstruction of the ACAD9‐ECSITCTD complex core. Consistent with its 7.8 Å resolution, the cryo‐EM map shows clear features corresponding to α‐helices. The VLCAD‐based homology model of ACAD9 is fitted into the cryo‐EM map as a rigid body, which explains slight discrepancies between the map and the model, while highlighting their overall good agreement that reflects structural conservation between VLCAD and ACAD9. The dehydrogenase domains and the C‐terminal linker and vestigial domains are shown in blue and gold, respectively. F) The cryo‐EM map is shown in the same orientations as in (E) but as an isosurface to better illustrate the lack of bound FAD (binding sites in the VLCAD‐based homology model are indicated in red). Scale bar=50 Å. A close‐up view is shown in Figure S13.

We then investigated the redox state of the FAD cofactor bound to the catalytic pocket of ACAD9, which typically shows a strong yellow colour when oxidized (Figure 3 B). Strikingly, the yellow colour was not observed during co‐purification of ACAD9 with ECSITCTD (Figure 3 B). Subsequent quantification of FAD content by UV spectroscopy and liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization (LC/ESI) MS measurements revealed the complete absence of FAD in ACAD9‐ECSITCTD (Figure 3 C). In addition, complex reconstitution by co‐incubating the purified proteins showed that FAD is actively released when ECSITCTD is added to ACAD9 (Figure 3 D). Furthermore, ECSITCTD prevents the reuptake of FAD by ACAD9 (Figure 3 A), indicating that ECSIT binding inhibits the reflavination of ACAD9. Finally, to obtain structural evidence for the unoccupied state of the FAD binding site, we refined the ACAD9‐ECSITCTD cryo‐EM reconstruction using a tight mask around the compact ACAD9 dimeric core to mitigate the contribution from the disordered ECSITCTD (Figure S7). The resulting cryo‐EM map at 7.8 Å resolution displayed clear secondary structural features consistent with the VLCAD‐based homology model, thus validating this procedure (Figure 3 E). Moreover, the resulting map revealed that the FAD binding site is clearly empty in the ECSIT‐bound state (Figure 3 F), in contrast to other cryo‐EM reconstructions of flavoproteins at similar resolution[ 36 , 37 ] and to the crystal structure of FAD‐bound VLCAD (PDB ID:3B96 [34] ) filtered to the resolution of our cryo‐EM map (Figure S13), corroborating the role of ECSIT in promoting ACAD9 deflavination and thereby, its loss of enzymatic activity.

Discussion

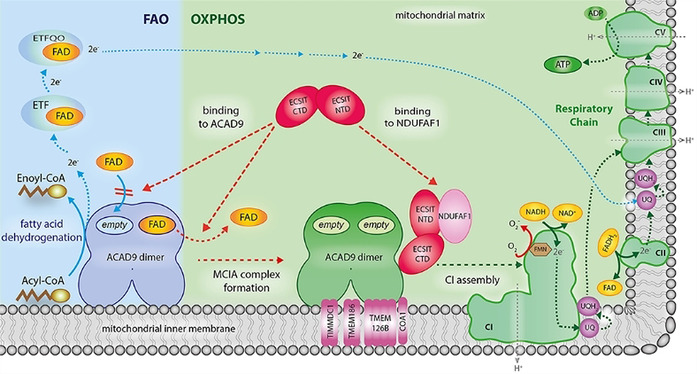

The mitochondrial Complex I assembly complex (MCIA) is required for the biogenesis of Complex I and is therefore crucial for the activation of the OXPHOS system. [11] FAO and OXPHOS are key pathways involved in cellular energetics. [1] Despite their functional relationship, evidence for a physical interaction between the two pathways is sparse. [38] Understanding how FAO and OXPHOS proteins interact and how defects in these two metabolic pathways contribute to mitochondrial disease pathogenesis is thus of potential importance for the development of new tailored therapeutic strategies. Here, we provide evidence that ECSIT, a protein involved in cytoplasmic and nuclear signalling pathways, acts as the central organising component of the MCIA complex (Figure 4). The modular nature of ECSIT, which is organised into N‐ and C‐terminal binding domains, enables recruitment of its MCIA partners NDUFAF1 and ACAD9 using independent interaction interfaces. We show that the C‐terminal region of ECSIT is largely disordered but forms a stable dimer and binds ACAD9 in the region of the latter's vestigial dehydrogenase domain. Strikingly, interaction with ECSIT induces ACAD9 to eject its FAD cofactor from the catalytic site. Our cryo‐EM analysis shows that ECSIT binds far from the ACAD9 FAD binding site. Therefore, the deflavination of ACAD9 presumably occurs via an allosteric mechanism, triggering the shutdown of dehydrogenase activity. Furthermore, this interaction prevents ACAD9 from reassociating with FAD and resuming its catalytic activity. Thus, upon binding to ACAD9, ECSIT actively antagonizes the FAO pathway and redirects ACAD9 to function as a CI assembly factor. A similar phenomenon recently reported for ETF dehydrogenase holoenzyme, whereby the binding of the ETF regulatory protein LYRM5 induces the efficient removal of FAD, [39] suggests that this negative regulatory mechanism may apply to diverse electron transfer flavoproteins.

Figure 4.

Proposed model of how deflavination of ACAD9 by ECSIT permits the coordinated regulation of the FAO and OXPHOS pathways. Clockwise from lower left: In the absence of ECSIT, ACAD9 acts as an acyl‐CoA dehydrogenase enzyme in the first step of the fatty acid β‐oxidation (FAO) pathway. To exert this function, ACAD9 needs the insertion of FAD prosthetic group into the catalytic pocket. Then, dehydrogenation of the acyl‐CoA substrate into an enoyl‐CoA intermediate metabolite is concomitant with the reduction of the FAD into FADH2 (solid blue lines). This allows the transfer of electrons to the FAD bound to electron transfer flavoprotein (ETF) and subsequently to the ETF‐ubiquinone oxireductase (ETF‐QO), ultimately allowing the electrons to reach the ubiquinone (UQ) pool in the respiratory chain (dashed blue lines). Lower left to lower right: ECSIT binding induces the ejection of FAD from ACAD9 and also inhibits the FAD reuptake step (dashed red lines), shutting down its dehydrogenase activity. This antagonizes the function of ACAD9 in FAO and results in its redeployment as a CI assembly factor. In parallel, the ability of ECSIT to recruit NDUFAF1 (dashed red line) allows formation of the entire MCIA holocomplex with the other membrane components TIMMDC1, TMEM186, TMEM126B and COA1. The latter is required for the assembly of a functional CI and subsequently for the activation of the respiratory chain as part of the OXPHOS system, implying the pumping of a proton gradient (H+, grey dashed lines) across the mitochondrial inner membrane that ultimately drives the generation of ATP (green dashed lines). For sake of clarity, only the binding of NDUFAF1‐ECSIT to one of the ACAD9 monomers is shown.

That our structural and biophysical analysis reveals that ECSIT stabilizes the ACAD9 homodimer through the vestigial dehydrogenase domain in the absence of FAD, suggests that this domain was co‐opted for protein interaction and may have evolved as a module for OXPHOS‐related functionality. In contrast, the solvent exposed region previously thought to mediate ACAD9‐ECSIT interactions is likely implicated in the catalytic function. Interestingly, however, this region connects the catalytic domain that binds FAD with the vestigial domain that binds ECSIT and might therefore participate in transmitting the allosteric signal from one binding site to the other or, as previously proposed, facilitate the association of ACAD9 with other MCIA membrane associated factors in the inner mitochondrial membrane.[ 10 , 11 , 15 , 17 , 27 , 35 ] This could explain why we observe a perturbed oxidation state of FAD when we swapped the residues in the chimera while the binding to ECSIT is maintained.

We previously showed that ECSIT interacts with enzymes producing Aβ (e.g. presenilin 2 and apolipoprotein E) and might be involved in AD pathogenesis. [31] Recent studies have shown decreased levels of ECSIT in AD patient brains, with increased ROS and defective mitochondria. [40] Our results suggest that a potential sequestering of ECSIT by Aβ enzymes would thus compromise both the assembly of CI and also the regulation of FAO, a reprogramming of pathways that could lead to altered metabolism in brain mitochondria and ultimately to neurodegeneration. [41]

Conclusion

The work presented here reveals a unique role for ECSIT as an assembly and regulatory component of the MCIA complex. Here, ECSIT would direct the core MCIA complex to the inner mitochondrial membrane via ACAD9 to allow the formation of the MCIA holocomplex and would subsequently stabilise a CI intermediate module by its interaction with NDUFAF1 [11] (Figure 4). Furthermore, we suggest that the ECSIT‐mediated regulation of the dual functions of ACAD9 permits crosstalk between the FAO and OXPHOS pathways that contributes to the coordination of the pathways to ensure efficient energy production. On the one hand, the formation of the MCIA complex facilitates the assembly of membrane intermediates as part of CI biogenesis, while on the other, the release of FAD makes ACAD9 quiescent in the initiation of the β‐oxidation of fatty acids (Figure 4). More generally, this work enhances our understanding of the control and regulation mechanisms responsible for mitochondrial energy metabolism and should foster future studies into the pathogenesis of diseases entailing OXPHOS and FAO deficiencies. Considering that dimeric ACAD9 is unstable without FAD (Figure S12) [27] and a multifunctional FAO complex is intimately associated with OXPHOS supercomplexes or respirasomes,[ 2 , 42 ] deflavination might be an efficient metabolic switch at the crossroads of assembly and activation of these superstructures. [43] More generally, our work suggests that ECSIT may play the role of a molecular link in bioenergetics and therefore a potential biomarker for mitochondria‐targeted diagnostics, particularly for diseases entailing OXPHOS and FAO deficiencies like AD.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. S. Zucchelli (University of Piemonte Orientale) for the TRAF6 plasmid, Dr. U. Stelzl (University of Graz) for the MaV203 yeast strain and Dr. P. Fender (IBSG Grenoble) for HEK293 cells. We are grateful to Dr. C. Mas (IBSG Grenoble) for support with SEC‐MALLS and to Dr. M. Brennich (BM29‐BioSAXS beamline, EMBL Grenoble) for support with SAXS analyses. We thank Dr. C. Petosa and Dr. A. Desfosses (IBS Grenoble) for discussions. We thank Dr. G. Schoehn for providing training and support, and D. Fenel for preliminary ns‐EM observations. Funding: This work used the platforms of Partnership for Soft Condensed Matter (PSCM) with support from ESRF and ILL; and the platforms of the Grenoble Instruct Center (ISBG; UMS 3518 CNRS‐CEA‐UJF‐EMBL) with support from FRISBI (ANR‐10‐INSB‐05‐02) and GRAL (ANR‐10‐LABX‐49‐01) within the Grenoble Partnership for Structural Biology (PSB). The electron microscope facility (Polara electron microscope) is supported by the Rhône‐Alpes Region (CIBLE and FEDER), the FRM, the CNRS, the University of Grenoble and the GIS‐IBISA. We acknowledge the ESRF for provision of beam time on CM01. The ESRF in‐house Research Program supported this work. The EM work was funded by the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 647784 to IG. M.J. was supported by the CEA PhD Program. RB acknowledges funding support from the ESRF PhD Program. ESPRIT work has been supported by Instruct‐ERIC PID 1710.

G. Giachin, M. Jessop, R. Bouverot, S. Acajjaoui, M. Saïdi, A. Chretien, M. Bacia-Verloop, L. Signor, P. J. Mas, A. Favier, E. Borel Meneroud, M. Hons, D. J. Hart, E. Kandiah, E. Boeri Erba, A. Buisson, G. Leonard, I. Gutsche, M. Soler-Lopez, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 4689.

Contributor Information

Dr. Irina Gutsche, Email: irina.gutsche@ibs.fr.

Dr. Montserrat Soler‐Lopez, Email: solerlop@esrf.fr.

References

- 1. Nsiah-Sefaa A., McKenzie M., Biosci. Rep. 2016, 36, e00313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Letts J. A., Sazanov L. A., Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2017, 24, 800–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lopez-Fabuel I., Le Douce J., Logan A., James A. M., Bonvento G., Murphy M. P., Almeida A., Bolanos J. P., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 13063–13068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ghezzi D., Zeviani M., Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2012, 748, 65–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Poole O. V., Hanna M. G., Pitceathly R. D., Discov. Med. 2015, 20, 325–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fassone E., Rahman S., J. Med. Genet. 2012, 49, 578–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vinothkumar K. R., Zhu J., Hirst J., Nature 2014, 515, 80–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fiedorczuk K., Letts J. A., Degliesposti G., Kaszuba K., Skehel M., Sazanov L. A., Nature 2016, 538, 406–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kampjut D., Sazanov L. A., Science 2020, 370, eabc4209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Guerrero-Castillo S., Baertling F., Kownatzki D., Wessels H. J., Arnold S., Brandt U., Nijtmans L., Cell Metab. 2017, 25, 128–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Formosa L. E., Muellner-Wong L., Reljic B., Sharpe A. J., Jackson T. D., Beilharz T. H., Stojanovski D., Lazarou M., Stroud D. A., Ryan M. T., Cell Rep. 2020, 31, 107541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vogel R. O., Janssen R. J., Ugalde C., Grovenstein M., Huijbens R. J., Visch H. J., van den Heuvel L. P., Willems P. H., Zeviani M., Smeitink J. A., Nijtmans L. G., FEBS J. 2005, 272, 5317–5326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vogel R. O., Janssen R. J., van den Brand M. A., Dieteren C. E., Verkaart S., Koopman W. J., Willems P. H., Pluk W., van den Heuvel L. P., Smeitink J. A., Nijtmans L. G., Genes Dev. 2007, 21, 615–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nouws J., Nijtmans L., Houten S. M., van den Brand M., Huynen M., Venselaar H., Hoefs S., Gloerich J., Kronick J., Hutchin T., Willems P., Rodenburg R., Wanders R., van den Heuvel L., Smeitink J., Vogel R. O., Cell Metab. 2010, 12, 283–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Heide H., Bleier L., Steger M., Ackermann J., Drose S., Schwamb B., Zornig M., Reichert A. S., Koch I., Wittig I., Brandt U., Cell Metab. 2012, 16, 538–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Guarani V., Paulo J., Zhai B., Huttlin E. L., Gygi S. P., Harper J. W., Mol. Cell. Biol. 2014, 34, 847–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sánchez-Caballero L., Guerrero-Castillo S., Nijtmans L., Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 2016, 1857, 980–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Formosa L. E., Dibley M. G., Stroud D. A., Ryan M. T., Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2018, 76, 154–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Andrews B., Carroll J., Ding S., Fearnley I. M., Walker J. E., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 18934–18939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Carneiro F. R. G., Lepelley A., Seeley J. J., Hayden M. S., Ghosh S., Cell Rep. 2018, 22, 2654–2666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Giachin G., Bouverot R., Acajjaoui S., Pantalone S., Soler-Lopez M., Front. Mol. Biosci. 2016, 3, 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fuhrmann D. C., Wittig I., Drose S., Schmid T., Dehne N., Brune B., Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2018, 75, 3051–3067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kopp E., Medzhitov R., Carothers J., Xiao C., Douglas I., Janeway C. A., Ghosh S., Genes Dev. 1999, 13, 2059–2071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Xiao C., Shim J. H., Kluppel M., Zhang S. S., Dong C., Flavell R. A., Fu X. Y., Wrana J. L., Hogan B. L., Ghosh S., Genes Dev. 2003, 17, 2933–2949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhang J., Zhang W., Zou D., Chen G., Wan T., Zhang M., Cao X., Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002, 297, 1033–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nouws J., Te Brinke H., Nijtmans L. G., Houten S. M., Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014, 23, 1311–1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schiff M., Haberberger B., Xia C., Mohsen A. W., Goetzman E. S., Wang Y., Uppala R., Zhang Y., Karunanidhi A., Prabhu D., Alharbi H., Prochownik E. V., Haack T., Haberle J., Munnich A., Rotig A., Taylor R. W., Nicholls R. D., Kim J. J., Prokisch H., Vockley J., Hum. Mol. Genet. 2015, 24, 3238–3247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wang T., Frangou C., Zhang J., Biotarget 2019, 3, 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Joh Y., Choi W. S., Dev. Reprod. 2017, 21, 417–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Soler-López M., Badiola N., Zanzoni A., Aloy P., Bioessays 2012, 34, 532–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Soler-Lopez M., Zanzoni A., Lluis R., Stelzl U., Aloy P., Genome Res. 2011, 21, 364–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mas P. J., Hart D. J., Methods Mol. Biol. 2017, 1586, 45–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kim J. J., Miura R., Eur. J. Biochem. 2004, 271, 483–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. McAndrew R. P., Wang Y., Mohsen A. W., He M., Vockley J., Kim J. J., J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 9435–9443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ensenauer R., He M., Willard J. M., Goetzman E. S., Corydon T. J., Vandahl B. B., Mohsen A. W., Isaya G., Vockley J., J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 32309–32316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cottevieille M., Larquet E., Jonic S., Petoukhov M. V., Caprini G., Paravisi S., Svergun D. I., Vanoni M. A., Boisset N., J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 8237–8249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Su M., Chakraborty S., Osawa Y., Zhang H., J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 1637–1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lim S. C., Tajika M., Shimura M., Carey K. T., Stroud D. A., Murayama K., Ohtake A., McKenzie M., Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Floyd B. J., Wilkerson E. M., Veling M. T., Minogue C. E., Xia C., Beebe E. T., Wrobel R. L., Cho H., Kremer L. S., Alston C. L., Gromek K. A., Dolan B. K., Ulbrich A., Stefely J. A., Bohl S. L., Werner K. M., Jochem A., Westphall M. S., Rensvold J. W., Taylor R. W., Prokisch H., Kim J. P., Coon J. J., Pagliarini D. J., Mol. Cell 2016, 63, 621–632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.A. Lepelley, L. S. Vaughn, A. Staniszewski, H. Zhang, F. Du, P. Koppensteiner, Z. Tomljanovic, F. R. G. Carneiro, A. F. Teich, I. Ninan, S. S. Yan, T. S. Postler, M. S. Hayden, O. Arancio, S. Ghosh, bioRxiv 2020, 2020.2001.2009.900407.

- 41. Montine T. J., Morrow J. D., Am. J. Pathol. 2005, 166, 1283–1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wang Y., Mohsen A. W., Mihalik S. J., Goetzman E. S., Vockley J., J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 29834–29841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hefti M. H., Vervoort J., van Berkel W. J., Eur. J. Biochem. 2003, 270, 4227–4242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary