Abstract

Introduction

Advances in HIV treatment have proven to be effective in increasing virological suppression, thereby decreasing morbidity, and increasing survival. Medication adherence is an important factor in reducing viral load among people living with HIV (PLWH) and in the elimination of transmission of HIV to uninfected partners. Achieving optimal medication adherence involves individuals taking their medications every day or as prescribed by their provider. However, not all PLWH in the USA are engaged in care, and only a minority have achieved suppressed viral load (viral load that is lower than the detectable limit of the assay). Sexual and gender minorities (SGM; those who do not identify as heterosexual or those who do not identify as the sex they were assigned at birth) represent a high-risk population for poor clinical outcomes and increased risk of HIV transmission, as they face barriers that can prevent optimal engagement in HIV care. Research in dyadic support, specifically within primary romantic partnerships, offers a promising avenue to improving engagement in care and treatment outcomes among SGM couples. Dyadic interventions, especially focused on primary romantic partnerships, have the potential to have a sustained impact after the structured intervention ends.

Methods and analysis

This paper describes the protocol for a randomised control trial of a theory-grounded, piloted intervention (DuoPACT) that cultivates and leverages the inherent sources of support within primary romantic relationships to improve engagement in HIV care and thus clinical outcomes among persons who are living with HIV and who identify as SGM (or their partners). Eligible participants must report being in a primary romantic relationship for at least 3 months, speak English, at least one partner must identify as a sexual or gender minority and at least one partner must be HIV+ with suboptimal engagement in HIV care, defined as less than excellent medication adherence, having not seen a provider in at least the past 8 months, having a detectable or unknown viral load or not currently on antiretroviral therapy. Eligible consenting couples are allocated equally to the two study arms: a structured six-session couples counselling intervention (DuoPACT) or a three-session individually-delivered HIV adherence counselling intervention (LifeSteps). The primary aim is to evaluate the efficacy of DuoPACT on virological suppression among HIV+ members of SGM couples with suboptimal engagement in care. The DuoPACT study began its target enrolment of 150 couples (300 individuals) in August 2017, and will continue to enrol until June 2021.

Ethics and dissemination

All procedures are approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of California, San Francisco. Written informed consent is obtained from all participants at enrolment, and study progress is reviewed twice yearly by an external Safety Monitoring Committee. Dissemination activities will include formal publications and report back sessions with the community.

Trial registration number

Keywords: HIV & AIDS, preventive medicine, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The DuoPACT intervention has been piloted and tested and is currently in its final phase testing the efficacy of a couples-based intervention approach to increasing engagement in HIV care.

A couples-based approach has the potential to have lasting effects after the conclusion of the formal study intervention, as partners take on more active supportive roles that can have sustained and dynamic impact over time.

The study is designed to detect changes in laboratory-confirmed HIV viral load, whereas other studies use self-reported viral load data (prone to reporting bias) or health record extraction (prone to missing or suboptimally-timed data).

The study is located in one geographical area, which may limit generalisability.

Relationships can be volatile leading to break-ups at various points in the study, including after consent visit and prior to study enrolment.

Introduction

Engagement in HIV care, including high levels of adherence to antiretroviral treatment (ART), is essential for managing HIV infection and for ending the HIV epidemic.1 2 Consistent medication adherence is linked to viral suppression, which allows people living with HIV (PLWH) to live longer and healthier lives, and viral suppression can eliminate the potential for further transmission to uninfected sexual partners.3 Suboptimal medication adherence reduces the chances of suppressing HIV viral load in PLWH. The HIV care cascade (also referred to as the care continuum) conceptualises the level of engagement in care in PLWH throughout the USA and has been used as a framework to address the barriers many people face managing their health and HIV treatment.4 As of 2016, 49% of PLWH in the USA were estimated to be retained in care, and only 53% of those had achieved viral suppression.5 Barriers associated with successful medication adherence, a key component of the continuum, include medication fatigue, side effects from the medications and forgetfulness.6 7 In addition, there are gaps within other parts of the HIV care continuum, such as retention in care, that prevent PLWH from achieving viral suppression.8 9 Recent research has focused on social support between dyads, specifically among romantic partnerships, which shows promise in addressing some of these gaps.

Being in a primary relationship can provide health-promoting benefits through tangible and emotional support, and various kinds of social support are associated with positive outcomes for people living with chronic illnesses.10–19 Within the context of couples affected by HIV, there is evidence that social support from primary romantic partnerships is associated with better HIV care engagement, such as ART adherence, compared with social support from people other than romantic partners.20–24

Although the preponderance of evidence suggests an overall positive impact from partners on many outcomes in healthcare, being in a relationship can also present challenges to HIV care engagement. Partners may have different roles in the dyad, such as a caretaker, that may prevent a person from taking care of themselves while taking care of their partner, which includes preventing them from taking care of their own HIV infection or other health demands.25 Negative influences, such as substance use, conflict, abuse and violence can also prevent optimal engagement in care for one or both partners in the dyad.26

Overall, however, the evidence supports the premise that social support within a relationship dyad has more positive than negative impact on HIV and other health-related outcomes. By extension, interventions designed to improve communication, emotional support and involvement in healthcare within dyads can improve health behaviours such as engagement in care. This is particularly true for some subpopulations in the USA, in which the HIV epidemic continues to be concentrated, including sexual and gender minority (SGM) individuals and their sexual partners.27 As many as half to three-quarters of HIV transmissions among sexual minority persons likely occur within the context of primary romantic relationships.28 While there are not parallel modelling data for gender minority persons, the worldwide prevalence of HIV among transgender persons is 49 times higher than among other groups.29 Collectively, these data support a focus on continued innovation and intervention for preventing HIV and optimising treatment among SGM persons and their partners.

Aim of the study

The primary objective of the DuoPACT study is to test a couple-level HIV intervention designed for SGM couples in sero-discordant or sero-concordant HIV-positive relationships that have evidence of poor engagement in care. The purpose of the intervention is to leverage and shape relationship dynamics to improve engagement in HIV care. Such an approach has the potential to be a powerful, cost-effective and sustainable tool to optimise treatment outcomes among couples affected by HIV. Due to lower viral loads being a quantitative element associated with better engagement in care, the study team uses HIV-1 RNA quantitative real-time PCR to analyse the trend of viral loads among participants living with HIV. The study will evaluate the efficacy of DuoPACT on the primary outcome of virological suppression among SGM PLWH in primary relationships.

Study specific aims

Primary aim

Evaluate the efficacy of DuoPACT on virological suppression among PLWH in primary relationships in which at least one partner identifies as sexual or gender minority.

Secondary aim

Explore the effect of DuoPACT on behavioural indicators of engagement in HIV care, including ART adherence and HIV care appointment attendance and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV-uninfected partners.

Explore the potential mediating effect of relationship variables DuoPACT has on patient and partner outcomes.

Methods and analysis

Study design

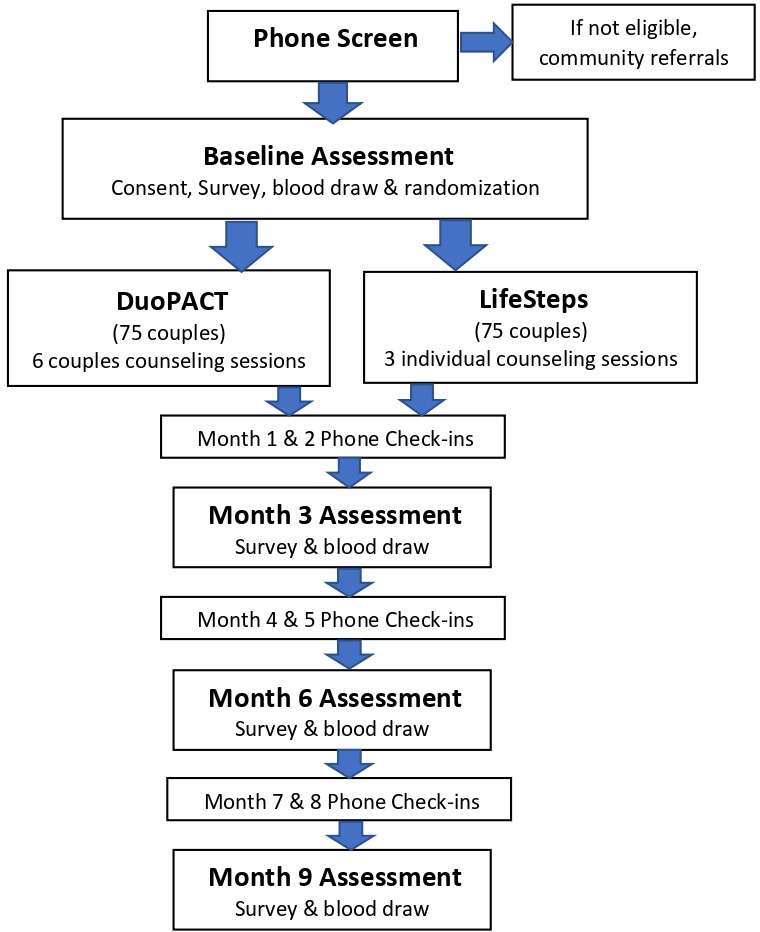

The study is a randomised control trial with 150 couples (300 individuals) in the San Francisco Bay Area in Northern California (figure 1). Recruitment began in August 2017 and will continue until June 2021, with final data collection complete in March 2022. Participation in the study takes a total of 9 months, with surveys conducted at baseline, 3, 6 and 9 months. The primary trial outcome is HIV virological suppression, as measured by laboratory assay. Secondary outcomes include behavioural indicators of engagement in HIV care, including ART adherence, HIV care appointment attendance, as well as use of PrEP for HIV-uninfected partners, a highly effective daily HIV medication that can prevent HIV infection following sexual exposure.

Figure 1.

Study Design.

The Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials statement (SPIRIT30; online supplemental form 1) provided guidance in implementing this protocol.

bmjopen-2020-037468supp001.pdf (4.3MB, pdf)

Study participants

The study sample consists of primary romantic couples, in which at least one partner identifies as SGM, both are age 18 or older and who describe each other as ‘a partner to whom they feel committed above anyone else and with whom they have had a sexual relationship’. At least one partner must be HIV+ and report suboptimal engagement in HIV care defined as one or more of the following: less than excellent medication adherence, having not seen a provider in at least the past 8 months, having a detectable or unknown viral load or is not currently (for the past 30 days) on ART. Less than excellent medication adherence is operationalised as reporting anything other than excellent on a validated single-item adherence rating scale that asks ‘Thinking back over the past 30 days, how would you rate your ability to take your HIV medications as prescribed?’ Response choices include excellent, very good, good, poor and very poor, with responses validated with viral load and electronic adherence measurements.31 32 See box 1 for full inclusion criteria.

Box 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria:

Both participants are 18+ years old.

Identifies as a sexual or gender minority.

In a primary romantic relationship for at least 3 months.

At least one partner is HIV+.

English-speaking.

Able to provide informed consent.

For HIV+ participants: Evidence of suboptimal engagement in HIV care, as indicated by one or more of the following: (1) Not on antiretroviral treatment (ART); (2) Reporting most recent viral load as detectable/unknown; or (3) If on ART, reporting less than excellent adherence on a validated adherence rating scale (report by self or partner); or (4) Reporting no HIV primary care appointments in the prior 8 months.

Exclusion criteria:

Evidence of severe cognitive impairment or active psychosis, as determined by the Principal Investigator (PI).

Unable to provide informed consent.

Relocating out of the Bay Area within 6 months of screening.

Participation as the same couple in the DuoPACT pilot.

Recruitment strategy

Participants are recruited through venue-based and online strategies as well as referral. Flyers are posted in venues (LGBTQ resource centres, bars, coffee shops and so on), community-based organisations (CBOs), clinics, pharmacies and community bulletin boards. Staff distribute packets with study materials, including an information sheet outlining the basic eligibility criteria, flyers and postcards, to clinics and CBOs throughout the Greater Bay Area. Providers and CBOs are asked to place these materials in waiting areas where potential participants are likely to see them. Study advertisements are posted online on Craigslist and Facebook and through dating/hook-up applications such as Growlr and Grindr.

In-person study recruitment takes place in HIV clinic waiting rooms. Recruiters present the study at staff/provider meetings in clinics throughout the Bay Area that have a high number of patients living with HIV to facilitate referral to the study. Recruiters also staff tables at symposia, conferences and community events to continue collaboration with HIV healthcare providers as well as connect with members of the community that may be interested in participating in the study.

All recruitment materials include a toll-free number and a link to the study webpage. Interested potential participants are directed to call the number listed on the recruitment resources or fill out the Contact Us form to learn more about the study and initiate the screening process. Study staff are notified when a potential participant completes the form and contact within one business day to ensure a higher chance of contact.

Enrolled participants have the opportunity to refer couples to the study via a ‘snowball’ recruitment method. To maintain confidentiality of the enrolled participants, potential participants are asked ‘how did you hear about the study’ and must mention the name of the participant that referred them. To maintain confidentiality, staff cannot confirm nor deny whether the participant identified is enrolled in the study.

Screening procedures

To determine eligibility, callers undergo a phone screening procedure, in which staff relay background about the study and ask a series of questions to determine eligibility, as per the criteria outlined above. Both individuals in the dyad must separately complete the phone screening process to determine eligibility. We have found in previous studies that when some individuals who are screened out figure out the particular exclusion criteria, they may call again with altered information in order to qualify. To prevent the potential for such misrepresentation, individuals are screened to the end of the phone screen form so that ineligible individuals will not readily be able to discern the criteria that excluded them. If an individual is screened as ineligible, the study will not contact their partner for screening.

Couple status verification

With couple-level studies that offer remuneration for participation, there is a risk of potential participants attempting to fake their relationship status or other inclusion criteria to enrol in the study. Therefore, a series of questions have been adapted from McMahon and colleagues to increase confidence that the individuals are indeed in a primary romantic relationship with each other.33 In this screening, each individual has to corroborate details from each other’s lives such as: (1) Where did your partner live before living in the Bay Area? (2) When is your partner’s birthday? (or at least what month?) (3) How old is your partner? (4) If they report not living together, ‘What street does your partner live on?’ Similar to McMahon’s protocol, we are lenient on the answers given between the dyad, as some relationships may be as recent as 3 months, and it is not uncommon for couples to live separately. Because these procedures are not fool-proof, when inconsistencies in responses between the two members of a dyad emerge, interviewers consult with senior project leadership to determine whether answers were sufficient to verify couple status. Rarely, more in-depth questions about the dyad are asked.

Study enrolment

Eligible and interested couples are scheduled for an in-person enrolment visit, requiring that both members of the couple present together in person. They are directed to bring proof of HIV status, which can be an official list of medications from their pharmacy, their HIV medication bottle with their name on it or a letter of diagnosis from their provider. To minimise the possibility that one partner is pressuring the other to participate, partners are consented in separate rooms. Trained staff read and give a detailed explanation of what to expect in the study, potential risks, compensation, as well as their rights as a research participant. To continue with the enrolment process, both partners must independently agree to the study procedures and sign their respective consent forms (online supplemental form 2). Each participant is given a copy of the consent document and another copy is securely kept with the study file. After the participant provides informed consent, staff collect detailed contact information, and a medical records release authorisation form to contact HIV care providers is also obtained in order to secure CD4 and viral load results if needed. A baseline visit is scheduled for 2 weeks later to allow time for laboratory procedures.

Participants who are living with HIV are directed to have their blood drawn for viral load and CD4 count at their choice of 1 of 40 community laboratory centres located throughout the area prior to their baseline survey visit. Participants are oriented to the service centre locations and hours of operation and are given a requisition for laboratory assays, labelled with participants' study ID and date of birth to minimise error with specimen mix-ups. Additionally, if a participant loses a paper requisition, study staff can send it electronically to the laboratory via a secure laboratory database, and date of birth will allow laboratory staff to verify participant identity with this minimal identifier. Laboratory results are posted to a secure online system for controlled access by study staff.

At the in-person baseline survey visit, participants are separated into separate private rooms to complete their own computer-assisted personal interviewing survey using Qualtrics (Provo, Utah, USA). The survey contains a series of validated measures focusing on adherence, medication use, partner support, relationship dynamics, behavioural health issues, as well as other important factors in their overall engagement in healthcare. The survey focuses on the participant’s relationship with their partner, communication, intimacy, conflict, social support and the role of HIV medications in their relationship. Relationship quality and closeness are measured through the survey using the Kurdek Commitment Scale.34 Partner perceptions of closeness and autonomy were previously found to be significantly associated with adherence and virological suppression.35 36 Therefore, the survey includes questions about Inclusion of Other in the Self using a figure that has a set of circles with varying degree of overlap which best reflects their overall relationship and another set of circles which describes their engagement in each partner’s healthcare.37 The survey questions assess reports of medication adherence,31 38 the participant’s knowledge of their partner’s medication adherence,22 adherence self-efficacy39 and reports of recent HIV healthcare appointment attendance. The baseline survey takes 1.5–2 hours to complete.

Randomisation

Once participants complete the baseline surveys, they are brought back together and are randomised as a couple (stratified by couple-level HIV serostatus) to one of two study conditions: (1) the DuoPACT couple intervention, which comprises a series of six couple sessions delivered weekly; or (2) LifeSteps, a three-session individual intervention for HIV+ partners who meet inclusion criterion suggesting suboptimal engagement in HIV care. Couples are randomised to study conditions via a 1:1 allocation ratio. Reflecting the stratified nature of the study design, separate randomisation lists were created for HIV-discordant and HIV-concordant negative couples. Within each stratum, couples are randomised using randomly-permuted block sizes of 2, 4 and 6. Randomisation is done via Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap). REDCap is a secure platform that is HIPPAA compliant and stores highly sensitive information.40 The first counselling session is usually scheduled within the subsequent week.

Intervention conditions

Experimental intervention

The DuoPACT intervention comprises 6 weekly couples’ sessions. Each session lasts 60–90 min and focuses on communication in the relationship and support for each other’s health and adherence to medical regimens (both ART for treatment and PrEP). The partners learn and practice communication skills, work on aligning support tactics (eg, reminding to take medications, go to clinic appointment with partner) and set goals related to their own health and medication adherence as well as supporting their partner’s health. They also practice problem solving as a couple and amplifying positive moments in the relationship. In between sessions, the couples are asked to track times each of them felt supported by their partner around their health. See table 1 for the focus of the DuoPACT intervention.

Table 1.

Skills covered in counselling sessions

| Couples sessions | LifeSteps |

|

|

Comparison intervention

The LifeSteps arm consists of an adaptation of a previously-validated HIV treatment adherence enhancement intervention.41 For this study, three one-on-one meetings with a trained counsellor are delivered weekly and last 60–90 min each. The curriculum is an 11-step process designed to improve the participant’s adherence to HIV treatment and medication regimens. The counsellors help the participants identify and problem solve any existing barriers to maximising treatment. The participants also learn guided relaxation techniques and cue control strategies. See table 1 for an outline of the topics covered in the interventions.

Intervention quality assurance

The sessions in both study arms are facilitated by trained counsellors and are audio-recorded and systematically reviewed for fidelity to the intervention. Counsellors complete a structured training programme that includes directed readings, mock sessions and instruction in ethics of human subjects’ research.

The intervention staff make careful considerations during either arm of the intervention to determine if they feel the intervention is harming the participant. The participant is also given their participant rights during the consent process detailing if they feel the intervention is harming them in any way, they can discontinue the intervention.

Follow-up data collection

Participants living with HIV complete three follow-up blood draws, and all participants complete 3, 6 and 9 month surveys regardless of study arm. Once each follow-up blood draw has been completed, each participant is electronically sent a personal Qualtrics link to a follow-up survey that they complete on their own device at any WIFI enabled convenient location. Each participant is asked to complete the assessment separately. If a participant does not have email, or a WIFI enabled device/access, they can come to our study office to complete the follow-up survey on our tablet. Follow-up surveys take approximately 1 hour to complete and include the core measures from the baseline. The final (9 month) assessment also includes a satisfaction and acceptability measure based on the Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire.42

Break-ups

Participants who report breaking-up with their partner are encouraged to continue participation in the study as originally planned, with the exclusion of any remaining couple intervention sessions, which would be contraindicated following break-up. Survey questions following break-ups are adapted to include measures about the break-up and omit all relationship measures.

Retention

A significant number of participants are from marginalised communities throughout the San Francisco Bay Area. Some are unstably housed, financially impoverished and may have other life circumstances that make it difficult to engage throughout the course of the study. During the enrolment process, study staff collect a detailed list of contacts to maintain retention throughout the 9 months of study participation, including three personal contacts that do not have to live locally, as well as any social workers and case managers at organisations or clinics throughout the Bay Area.

To maintain contact with participants throughout their involvement in the study, study researchers conduct monthly phone check-ins between the follow-up activities (see figure 1). The check-ins are meant to maintain stable contact, to update contact information for each participant, break-ups and collect timely information about their overall engagement in HIV care (eg, recent medication adherence and medical provider appointments). Check-ins are also useful to learn about participant’s whereabouts, including incarceration or hospitalisations.

Incentives

Participants are compensated for their participation in each study procedure using Greenphire Clincards, a reloadable debit card that allows them to immediately receive payments for each study procedure. The incentives, ranging from US$20 for surveys to US$50 for blood draws, are designed to be enough to compensate for time and travel to study visits but not so high as to coerce enrolment.

Participant and public involvement

The current study builds on 10 years of formative work with participants, in which qualitative and quantitative data were used to guide the development of the intervention. This includes a pilot trial with participants, in which feedback on intervention components was solicited. Participants were involved in the pilot intervention, and their input was used to guide refinements in the protocol. They were not involved in the recruitment to and conduct of the study. At study exit, we assess qualitatively and quantitatively how patients perceived all aspects of the intervention and other study components. We ask participants if they would like to be sent reports and publications resulting from the study.

Confidentiality and data security

Participant data are identified only by a coded study number. Information collected on paper is kept in locked filing cabinets accessible only to study staff. Information collected on computer-assisted self-interviewing (CASI) computers or encrypted tablets is stored on a secure server behind secure firewalls and is accessible only to study staff. Any records linking study numbers to identifiers (such as tracking and contact information) are kept in a password protected database on a secure server and are accessible only to study staff members. All audio recordings are moved onto a secure password protected server and erased off the recorder immediately after the interview. Recordings are labelled with a coded study number.

Quality assurance

The Project Director and Data Manager/Statistician perform weekly data audits. Overall recruitment goals, missing data and follow-up failures are continuously tracked and audited and are reviewed. All surveys are administered via online methods using Qualtrics, which includes range checks and skip logic programming. The study’s biostatistician provides ongoing monitoring of study progress. Audio recordings of baseline assessments are reviewed on a weekly basis, and approximately 20% of the experimental and comparison intervention sessions are reviewed by the supervising clinician for intervention fidelity. In the event an emergency or adverse event arises, staff have been trained and have access to a Manual of Operations, which details the appropriate measures, and the supervising clinician will be consulted and the Principal Investigator, a licensed clinical psychologist, will be immediately notified.

Ethics and dissemination

All procedures are approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of California, San Francisco. Written informed consent is obtained from all participants at enrolment, and study progress is reviewed twice yearly by an external Safety Monitoring Committee.

If effective, this programme could be easily implemented in clinics and community settings. A high priority of this work is to make findings available and to export effective components of the intervention into real-world settings. In addition to traditional publications and presentations, we plan to create user-friendly ‘Science to Community’ publications. At the study’s conclusion, we will host forums in which we invite former participants, other researchers and clinic and agency staff to hear and discuss findings. Finally, we will make study materials available online and in print format. The Center for AIDS Prevention Studies (CAPS) Community Engagement Core is widely recognised for its dissemination activities.

Analysis plan

Preliminary analyses

Frequency tables for all variables and measures of central tendency and variability for continuous variables will characterise the sample and will be stratified by randomisation group (ie, intervention vs control) to check for imbalances. If the two groups differ significantly at baseline on one or more covariates (eg, on ART vs not), we will use methods based on the Rubin causal model (eg, propensity scores, double-robust estimation) to obtain the desired marginal effect estimates under the counterfactual assumption of balanced groups.43–47 We will address incomplete data with multiple imputation (MI)48 which makes the relatively mild assumption that incomplete data arise from a conditionally random (missing at random (MAR)) mechanism.49 Auxiliary variables will be included to help meet the MAR assumption50 51 and sensitivity analyses will be conducted with pattern-mixture models and weighted MI52 to assess the robustness of the MAR assumption.53 As part of the sensitivity analyses, we will also perform analyses using complete case analysis (CCA); if results from sensitivity analyses (including CCA) yield different substantive conclusions from the original MI-based analyses, both sets of results will be reported. SAS54 will be used to perform the proposed analyses.

Primary analyses to address specific aim 1

We hypothesise that, following the intervention, the odds of suppressed viral load will be higher for intervention participants than for control participants (Hypothesis 1). Our primary interest is to estimate the marginal or population-average effect of intervention participation on each outcome rather than the effect for a hypothetical average subject or couple.55 Moreover, within-subject and within-couple correlations among outcomes are considered nuisance parameters, not quantities of interest to be modelled explicitly. Finally, recent recommendations in the literature point to the superior performance of generalised estimating equations (GEE) relative to generalised linear mixed models for the analysis of dyadic data with categorical outcomes (eg, virological suppression).56 Accordingly, GEE will be used to perform the proposed primary analysis, which is a planned time-averaged comparison of post-baseline measurements across the intervention and control groups to test primary Hypothesis 1. Alpha will be set at 0.05 for this planned comparison. Any additional post-hoc comparisons (eg, paired comparisons of the two study arms at each time point) will maintain nominal α=0.05 through the use of simulation-based stepdown multiple comparison methods.57 The alternating logistic regression approach implemented in SAS PROC GENMOD can be used to address the three-level clustering of observations within participants and participants within dyads. Though GEE estimates are consistent even if the correlation structure is misspecified, GEE’s statistical efficiency improves as the working correlation structure more closely approximates the actual correlation structure,58 so various correlation structures suitable for the study’s design will be considered (eg, exchangeable; nested-1).59 The quasi-likelihood information criterion (QIC) statistic will be used to select the final correlation structure.60 Couple HIV serostatus will be included in all models as required by the stratified randomised design.61 Additional covariates such as couple cohabitation status and relationship length will be included if they improve QIC. Robust SEs will be used to obtain correct inferences even if the chosen correlation structure remains slightly misspecified. The primary analysis will be performed under the intention-to-treat principle.

Secondary analysis to address specific aim 2

To explore the effect of the intervention on hypothesised mechanisms of action, secondary analyses will evaluate whether participants assigned to the intervention report higher mean scores on theory-based constructs such as healthcare empowerment, adherence self-efficacy, adherence, social support, HIV treatment information and treatment beliefs and expectancies. These analyses will also investigate whether these constructs mediate the relationship between intervention group assignment and virological suppression and whether couple HIV-serostatus and cohabitation moderate these associations. Main and interaction effects of couple drug and alcohol use and racial concordance will also be evaluated in these models. Mediation and moderation will be assessed using the causal inference-based approach of Valeri and Vanderweele, which yields optimal estimates of indirect effects in the presence of binary outcomes and moderator–mediator interactions.62 Mplus will be used to fit causal mediation models because it can adjust SEs for nesting of participants within couples.63 Additional secondary analyses will consider the effects of intervention dose exposure on virological suppression as a main effect and as moderated and mediated by theory-based constructs described above to determine for whom and via which mechanisms of action intervention dosing is most efficacious. These secondary exploratory data analyses will be defined in a data analysis plan prior to conducting final analyses.

Secondary analysis to address specific aim 3

Analyses with intact dyads enable investigation of couple-based research questions that explore how relationship dynamics affect behaviour change in partnerships. We will extend the analyses described above to include actor and partner effects for continuous covariates and mediators. Actor effects describe the influence that one’s standing on independent or mediating variables of interest (eg, communication, intimacy) has on one’s own dependent variables (eg, self’s virological suppression) whereas partner effects describe the influence that one’s standing on independent variables has on the dependent variables of one’s partner (eg, partner’s virological suppression). This technique illuminates the effects that partners in intimate relationships can have on both their own and their partner’s behaviour. Actor and partner effects can be evaluated in models with either continuous64 (eg, healthcare empowerment, adherence self-efficacy) or categorical dependent variables (eg, virological suppression).65 A closely related approach uses sums and differences of continuous covariates and mediators to quantify within-couple and between-couple effects. For continuous dependent variables, within-couple hypotheses will be tested with a GEE model, in which couple-level difference scores on the outcome variable (eg, adherence self-efficacy) will be regressed onto both the couple-level difference and sum scores for the predictor variable (eg, communication).66 Computing sums and differences for categorical outcomes is not feasible, but it is still possible to investigate the effects of sums and differences of individuals’ continuous covariates and mediators on individual-level categorical responses (eg, virological suppression) to quantify the separate influences of between-couple and within-couple effects of continuous mediators on individuals’ categorical outcomes.67 These secondary exploratory data analyses will be defined in a data analysis plan prior to conducting final analyses.

Interim analyses

No interim analyses are planned.

Statistical power analysis

Power analyses were generated using the two-group repeated proportions module in NCSS PASS68 to compute minimum detectable effect sizes for the primary analysis to address Hypothesis 1. The study will begin with 300 participants from 150 couples evenly assigned to the intervention and control groups. We further assume half of the couples will be HIV sero-discordant (N=150) and half will be sero-concordant (N=150). Under these assumptions, three-quarters (N=180) of the 240 participants will be living with HIV and therefore have virological suppression outcome data. Due to the clustered nature of the dyadic data, observations from participants who belong to the same couple who are living with HIV will be correlated. In our previous Duo observational study of couples, for instance, the average within-couple correlation of viral load measurements was r=0.23. Accordingly, we lowered the effective sample size (ESS) input for the power analyses to be ESS=N/DEFF for these couples, where DEFF is the design effect or variance inflation attributable to using correlated data. DEFF is computed as 1+(M–1)×r, where M is the number of participants per dyad (ie, two). Therefore DEFF=1+(2–1)×0.23=1.23, so ESS for HIV-concordant couples is 150 HIV participants in HIV-concordant couples/1.23=122. For HIV-discordant couples, 75 participants will be living with HIV and since their outcome values should be statistically independent, no design effect adjustment is required for this subset of couples. Thus, the total ESS for the proposed primary analysis incorporating members from both sero-concordant and sero-discordant couples is 122+75=197. Further assuming 20% attrition, the post-attrition ESS will be 197×(1–0.20)=158 for analysis at all time points. Assuming, α=0.05, power=0.80 and ESS=158, we computed the minimum detectable OR, proportion difference (pdiff) and standardised proportion difference (h) for the proposed time-averaged comparisons, assuming three post-baseline measurements and assuming a wide range within-subject correlation values, r, which were varied between 0.20 and 0.80. Because the virological suppression base rates P0 are also unknown, we considered several scenarios: low (P0=30%), medium (P0=50%) and high (P0=80%). Under these assumptions, the minimum detectable effect size estimates for our primary analyses range from 10.4% to 20.1% for raw pdiffs; standardised effect size estimates (h) range from 0.30 to 0.41, which are between published benchmarks of 0.20 and 0.50 for small and medium standardised effect sizes,69 respectively. These results suggest that our primary analysis will have sufficient power to detect effects that are between small and medium across a wide range of potential analytical scenarios (see table 2).

Table 2.

Minimum detectable effect sizes

| Within-subject correlation | Control group proportion | ||||||||

| P0=0.30 (low) | P0=0.50 (medium) | P0=0.80 (high) | |||||||

| ρ | OR | pdiff | h | OR | pdiff | h | OR | pdiff | h |

| 0.20 | 1.88 | 14.6% | 0.303 | 1.86 | 15.0% | 0.305 | 2.37 | 10.4% | 0.297 |

| 0.30 | 1.96 | 15.7% | 0.325 | 1.94 | 16.0% | 0.326 | 2.53 | 11.0% | 0.318 |

| 0.40 | 2.04 | 16.7% | 0.345 | 2.02 | 16.9% | 0.345 | 2.70 | 11.5% | 0.336 |

| 0.50 | 2.12 | 17.6% | 0.363 | 2.10 | 17.8% | 0.364 | 2.87 | 12.0% | 0.354 |

| 0.60 | 2.20 | 18.5% | 0.382 | 2.18 | 18.6% | 0.381 | 3.04 | 12.4% | 0.369 |

| 0.70 | 2.27 | 19.3% | 0.398 | 2.27 | 19.4% | 0.398 | 3.22 | 12.8% | 0.384 |

| 0.80 | 2.35 | 20.1% | 0.414 | 2.35 | 20.1% | 0.414 | 3.40 | 13.2% | 0.400 |

Discussion

HIV care is a lifelong process that can create challenges for PLWH. Dyadic support within couple relationships provides an opportunity for partners in primary romantic relationships to help address the barriers associated with their HIV care engagement. By developing an intervention that focuses on partner support, communication, problem solving as a couple, relationship strengths and social support, couples can develop important skills to maintain active and successful engagement in their HIV care. Couple-level interventions have the potential to continue to have a sustained impact after the formal intervention ends, as the partner takes on an active and sustained role in supporting target behaviours. Optimal engagement in care will subsequently lead to virological suppression, leading to increased survival and quality of life, decreased morbidity and reduced likelihood of transmission of HIV to previously uninfected partners.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the tireless efforts of study staff and the time and attention of the individuals who enrol in the study.

Footnotes

Contributors: APT took the lead on drafting the manuscript and is involved in study data recruitment, enrolment and data collection. LSC contributed to drafting and revising the manuscript and serves as project director for the project. DPO drafted sections of the manuscript and oversees intervention delivery and supervision. TBN drafted sections of the manuscript and is the senior statistician for the study. MOJ contributed conception of the study, contributed to drafting the protocol and provides scientific oversight of the project.

Funding: This project is supported by grant NINR - R01NR10187.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

References

- 1.Fauci AS, Redfield RR, Sigounas G, et al. Ending the HIV epidemic: a plan for the United States. JAMA 2019;321:844–5. 10.1001/jama.2019.1343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Volberding PA. Hiv treatment and prevention: an overview of recommendations from the IAS-USA antiretroviral guidelines panel. Top Antivir Med 2017;25:17–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson MO, Catz SL, Remien RH, et al. Theory-guided, empirically supported avenues for intervention on HIV medication nonadherence: findings from the healthy living project. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2003;17:645–56. 10.1089/108729103771928708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gardner EM, McLees MP, Steiner JF, et al. The spectrum of engagement in HIV care and its relevance to test-and-treat strategies for prevention of HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis 2011;52:793–800. 10.1093/cid/ciq243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Understanding the HIV care continuum . Centers for disease control and prevention, 2019. Available: www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/factsheets/cdc-hiv-care-continuum.pdf

- 6.Saberi P, Neilands TB, Vittinghoff E, et al. Barriers to antiretroviral therapy adherence and plasma HIV RNA suppression among AIDS clinical Trials Group study participants. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2015;29:111–6. 10.1089/apc.2014.0255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sauceda JA, Neilands TB, Johnson MO, et al. An update on the barriers to adherence and a definition of self-report Non-adherence given advancements in antiretroviral therapy (art). AIDS Behav 2018;22:939–47. 10.1007/s10461-017-1759-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mugavero MJ. Elements of the HIV care continuum: improving engagement and retention in care. Top Antivir Med 2016;24:115–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giordano TP, Gifford AL, White AC, et al. Retention in care: a challenge to survival with HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis 2007;44:1493–9. 10.1086/516778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arden-Close E, McGrath N. Health behaviour change interventions for couples: a systematic review. Br J Health Psychol 2017;22:215–37. 10.1111/bjhp.12227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ayotte BJ, Yang FM, Jones RN. Physical health and depression: a dyadic study of chronic health conditions and depressive symptomatology in older adult couples. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2010;65:438–48. 10.1093/geronb/gbq033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barr AB, Simons RL. A dyadic analysis of relationships and health: does couple-level context condition partner effects? J Fam Psychol 2014;28:448–59. 10.1037/a0037310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beverly EA, Wray LA. The role of collective efficacy in exercise adherence: a qualitative study of spousal support and type 2 diabetes management. Health Educ Res 2010;25:211–23. 10.1093/her/cyn032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blanchard VL, Hawkins AJ, Baldwin SA, et al. Investigating the effects of marriage and relationship education on couples' communication skills: a meta-analytic study. J Fam Psychol 2009;23:203–14. 10.1037/a0015211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burman B, Margolin G. Analysis of the association between marital relationships and health problems: an interactional perspective. Psychol Bull 1992;112:39–63. 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ell K, Nishimoto R, Mediansky L, et al. Social relations, social support and survival among patients with cancer. J Psychosom Res 1992;36:531–41. 10.1016/0022-3999(92)90038-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Funch DP, Marshall J. The role of stress, social support and age in survival from breast cancer. J Psychosom Res 1983;27:77–83. 10.1016/0022-3999(83)90112-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.House JS, Landis KR, Umberson D. Social relationships and health. Science 1988;241:540–5. 10.1126/science.3399889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maunsell E, Brisson J, Deschênes L. Social support and survival among women with breast cancer. Cancer 1995;76:631–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldenberg T, Clarke D, Stephenson R. "Working together to reach a goal": MSM's perceptions of dyadic HIV care for same-sex male couples. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013;64 Suppl 1:S52–61. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182a9014a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldenberg T, Stephenson R. "The more support you have the better": partner support and dyadic HIV care across the continuum for gay and bisexual men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2015;69 Suppl 1:S73–9. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson MO, Dilworth SE, Neilands TB. Partner reports of patients' HIV treatment adherence. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2011;56:e117–8. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31820bd2ce [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson MO, Dilworth SE, Taylor JM, et al. Primary relationships, HIV treatment adherence, and virologic control. AIDS Behav 2012;16:1511–21. 10.1007/s10461-011-0021-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wrubel J, Stumbo S, Johnson MO. Male same sex couple dynamics and received social support for HIV medication adherence. J Soc Pers Relat 2010;27:553–72. 10.1177/0265407510364870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Revenson TA, Schiaffino KM, Majerovitz SD, et al. Social support as a double-edged sword: the relation of positive and problematic support to depression among rheumatoid arthritis patients. Soc Sci Med 1991;33:807–13. 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90385-P [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tan JY, Campbell CK, Conroy AA, et al. Couple-Level dynamics and multilevel challenges among black men who have sex with men: a framework of Dyadic HIV care. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2018;32:459–67. 10.1089/apc.2018.0131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Hiv surveillance report, vol. 28: diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2016: US department of health and human services, 2017. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2016-vol-28.pdf [Accessed 13 Aug 2018].

- 28.Sullivan PS, Salazar L, Buchbinder S, et al. Estimating the proportion of HIV transmissions from main sex partners among men who have sex with men in five us cities. AIDS 2009;23:1153–62. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832baa34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baral SD, Poteat T, Strömdahl S, et al. Worldwide burden of HIV in transgender women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2013;13:214–22. 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70315-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chan A-W, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, et al. Spirit 2013: new guidance for content of clinical trial protocols. The Lancet 2013;381:91–2. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62160-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu M, Safren SA, Skolnik PR, et al. Optimal recall period and response task for self-reported HIV medication adherence. AIDS Behav 2008;12:86–94. 10.1007/s10461-007-9261-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feldman BJ, Fredericksen RJ, Crane PK, et al. Evaluation of the single-item self-rating adherence scale for use in routine clinical care of people living with HIV. AIDS Behav 2013;17:307–18. 10.1007/s10461-012-0326-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McMahon JM, Tortu S, Torres L, et al. Recruitment of heterosexual couples in public health research: a study protocol. BMC Med Res Methodol 2003;3:24. 10.1186/1471-2288-3-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kurdek LA. Assessing multiple determinants of relationship commitment in cohabiting gay, cohabiting Lesbian, dating heterosexual, and married heterosexual couples. Fam Relat 1995;44:261–6. 10.2307/585524 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gamarel KE, Neilands TB, Golub SA, et al. An omitted level: an examination of relational orientations and viral suppression among HIV serodiscordant male couples. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014;66:193–6. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gamarel KE, Starks TJ, Dilworth SE, et al. Personal or relational? examining sexual health in the context of HIV serodiscordant same-sex male couples. AIDS Behav 2014;18:171–9. 10.1007/s10461-013-0490-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aron A, Aron EN, Smollan D. Inclusion of other in the self scale and the structure of interpersonal closeness. J Pers Soc Psychol 1992;63:596–612. 10.1037/0022-3514.63.4.596 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walsh JC, Mandalia S, Gazzard BG. Responses to a 1 month self-report on adherence to antiretroviral therapy are consistent with electronic data and virological treatment outcome. AIDS 2002;16:269–77. 10.1097/00002030-200201250-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnson MO, Neilands TB, Dilworth SE, et al. The role of self-efficacy in HIV treatment adherence: validation of the HIV treatment adherence self-efficacy scale (HIV-ASES). J Behav Med 2007;30:359–70. 10.1007/s10865-007-9118-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Patridge EF, Bardyn TP. Research electronic data capture (REDCap). Jmla 2018;106:142–4. 10.5195/JMLA.2018.319 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Safren SA, Otto MW, Worth JL, et al. Two strategies to increase adherence to HIV antiretroviral medication: life-steps and medication monitoring. Behav Res Ther 2001;39:1151–62. 10.1016/S0005-7967(00)00091-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ware JE, Snyder MK, Wright WR, et al. Defining and measuring patient satisfaction with medical care. Eval Program Plann 1983;6:247–63. 10.1016/0149-7189(83)90005-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Luellen JK, Shadish WR, Clark MH. Propensity scores: an introduction and experimental test. Eval Rev 2005;29:530–58. 10.1177/0193841X05275596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rubin DB. On principles for modeling propensity scores in medical research. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2004;13:855–7. 10.1002/pds.968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seaman S, Copas A. Doubly robust generalized estimating equations for longitudinal data. Stat Med 2009;28:937–55. 10.1002/sim.3520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shadish WR, Luellen JK, Clark MH. Propensity Scores and Quasi-Experiments: A Testimony to the Practical Side of Lee Sechrest. : Bootzin RR, McKnight PE, . Strengthening research methodology: psychological measurement and evaluation. Washington DC, US: American psychological association, 2006: 143–57. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weitzen S, Lapane KL, Toledano AY, et al. Principles for modeling propensity scores in medical research: a systematic literature review. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2004;13:841–53. 10.1002/pds.969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: our view of the state of the art. Psychol Methods 2002;7:147–77. 10.1037/1082-989X.7.2.147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Little JWA, Rubin DA. Statistical analysis with missing data. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Collins LM, Schafer JL, Kam CM. A comparison of inclusive and restrictive strategies in modern missing data procedures. Psychol Methods 2001;6:330–51. 10.1037/1082-989X.6.4.330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Graham JW. Adding Missing-Data-Relevant variables to FIML-Based structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 2003;10:80–100. 10.1207/S15328007SEM1001_4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Carpenter JR, Kenward MG, White IR. Sensitivity analysis after multiple imputation under missing at random: a weighting approach. Stat Methods Med Res 2007;16:259–75. 10.1177/0962280206075303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hedeker D, Gibbons RD. Application of random-effects pattern-mixture models for missing data in longitudinal studies. Psychol Methods 1997;2:64–78. 10.1037/1082-989X.2.1.64 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.SAS Institute . Sas on-line Doc, version 9.0. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, Inc, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Young ML, Preisser JS, Qaqish BF, et al. Comparison of subject-specific and population averaged models for count data from cluster-unit intervention trials. Stat Methods Med Res 2007;16:167–84. 10.1177/0962280206071931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Loeys T, Molenberghs G. Modeling actor and partner effects in dyadic data when outcomes are categorical. Psychol Methods 2013;18:220–36. 10.1037/a0030640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Westfall PH, Young SS. Resmpling based multiple testing: examples and methods for p-value adjustment. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hardin J, Hilbe J. Generalized estimating equations. New York: Chapman & Hall/CRC, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shults J, Sun W, Tu X, et al. A comparison of several approaches for choosing between working correlation structures in generalized estimating equation analysis of longitudinal binary data. Stat Med 2009;28:2338–55. 10.1002/sim.3622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pan W. Akaike's information criterion in generalized estimating equations. Biometrics 2001;57:120–5. 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2001.00120.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kahan BC, Morris TP. Improper analysis of trials randomised using stratified blocks or minimisation. Stat Med 2012;31:328–40. 10.1002/sim.4431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Valeri L, Vanderweele TJ. Mediation analysis allowing for exposure-mediator interactions and causal interpretation: theoretical assumptions and implementation with SAS and SPSS macros. Psychol Methods 2013;18:137–50. 10.1037/a0031034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Muthén BO. Applications of causally Dened direct and indirect effects in mediation analysis using SEM in mPLUS, 2011. Available: http://www.statmodel.com/examples/penn.shtml#extendSEM [Accessed 12 Mar 2013].

- 64.Campbell L, Kashy DA. Estimating actor, partner, and interaction effects for dyadic data using proC mixed and HLM: a user-friendly guide. Pers Relatsh 2002;9:327–42. 10.1111/1475-6811.00023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.McMahon JM, Pouget ER, Tortu S. A guide for multilevel modeling of dyadic data with binary outcomes using SAS proC NLMIXED. Comput Stat Data Anal 2006;50:3663–80. 10.1016/j.csda.2005.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Allison P. Fixed effects regression methods for longitudinal data using SAS. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Neuhaus JM, Kalbfleisch JD, Hauck WW. A comparison of cluster-specific and population-averaged approaches for analyzing correlated binary data. International Statistical Review / Revue Internationale de Statistique 1991;59:25–35. 10.2307/1403572 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.NCSS Statistical Software . NCSS PASS 2008 [program]. 2008 version. Kaysville, Utah, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Crosby RA, Rothenberg R. In STI interventions, size matters. Sex Transm Infect 2004;80:82–5. 10.1136/sti.2003.007625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-037468supp001.pdf (4.3MB, pdf)