Abstract

Elevated tropospheric ozone concentration (O3) significantly reduces photosynthesis and productivity in several C4 crops including maize, switchgrass and sugarcane. However, it is unknown how O3 affects plant growth, development and productivity in sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L.), an emerging C4 bioenergy crop. Here, we investigated the effects of elevated O3 on photosynthesis, biomass and nutrient composition of a number of sorghum genotypes over two seasons in the field using free‐air concentration enrichment (FACE), and in growth chambers. We also tested if elevated O3 altered the relationship between stomatal conductance and environmental conditions using two common stomatal conductance models. Sorghum genotypes showed significant variability in plant functional traits, including photosynthetic capacity, leaf N content and specific leaf area, but responded similarly to O3. At the FACE experiment, elevated O3 did not alter net CO2 assimilation (A), stomatal conductance (g s), stomatal sensitivity to the environment, chlorophyll fluorescence and plant biomass, but led to reductions in the maximum carboxylation capacity of phosphoenolpyruvate and increased stomatal limitation to A in both years. These findings suggest that bioenergy sorghum is tolerant to O3 and could be used to enhance biomass productivity in O3 polluted regions.

Keywords: biomass, BWB model, chlorophyll fluorescence, MED model, photosynthesis, stomatal conductance

Short abstract

Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L.), a widely adapted and highly productive C4 grass, has potential as a bioenergy feedstock. In this study, we found that sorghum genotypes exhibit significant variability in plant functional traits, but a similar response to O3. Elevated O3 did not alter net CO2 assimilation (A), stomatal conductance (g s) and chlorophyll fluorescence in multiple genotypes of sorghum in both field and chamber experiments. We suggest that sorghum could be used to enhance biomass production for bioenergy in O3 polluted regions.

1. INTRODUCTION

Rapid population growth is predicted to increase global demand for both food and energy (Tilman et al., 2009). Renewable biofuels (largely ethanol) derived from bioenergy feedstocks have the potential to replace fossil energy and reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and contribute to economic growth and energy security over the long‐term (Reid, Ali, & Field, 2020; Tilman et al., 2009; Yuan, Tiller, AI‐Ahman, Stewart, & Stewart, 2008). Approximately 40% of the corn crop was used to produce ethanol in the United States over past 10 years (https://afdc.energy.gov/data/10339). However, ethanol can also be derived from other highly efficient C4 crops, such as sorghum, switchgrass and miscanthus (Calviño & Messing, 2012; Regassa & Wortmann, 2014; Rooney, Blumenthal, Bean, & Mullet, 2007; Schmer, Vogel, Mitchell, & Perrin, 2008; Wullschleger, Davis, Borsuk, Gunderson, & Lynd, 2010; Yuan et al., 2008). Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L.), a widely adapted and highly productive C4 grass, has been identified as a promising feedstock for conversion to biofuels with a low input cost (Calviño & Messing, 2012; Regassa & Wortmann, 2014; Rooney et al., 2007). Sorghum requires minimal water and nutrient supply for its growth and can be cultivated on marginal croplands where water deficits, salinity and other constraints exist (Regassa & Wortmann, 2014). In contrast to maize, which stores about 85% starch in grains, many sorghum genotypes produce high biomass and accumulate a large amount of sugar in the stem that can be directly used for biofuel production (Calviño & Messing, 2012; Regassa & Wortmann, 2014; Rooney et al., 2007). Although sorghum is well‐adapted to marginal environments and produces high biomass, the stability of production under atmospheric pollution, in particular O3 pollution, is unknown.

Tropospheric ozone (O3) is a major secondary air pollutant formed from photochemical reactions of carbon monoxide (CO), methane and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in the presence of nitrogen oxides (NOx) (Atkinson, 2000; Monks et al., 2015). Global O3 concentrations have significantly increased since the Industrial Revolution due to increased O3 precursor emissions (Monks et al., 2015; Young et al., 2013). Although O3 concentrations have decreased in the eastern United States and parts of Europe over the past 20 years due to reductions of anthropogenic emissions, they are predicted to increase rapidly in developing regions such as south and east Asia and urban areas where O3 concentration peaks of up to 120 nL L−1 are measured (Chang, Petropavlovskikh, Cooper, Schultz, & Wang, 2017; Gao et al., 2015; Verma, Lakhani, & Kumari, 2017). Tropospheric O3 is well recognized to have a deleterious impact on plant growth and development, resulting in a substantial loss of crop productivity and yield, as well as plant species diversity worldwide (Ainsworth, Yendrek, Sitch, Collins, & Emberson, 2012; Morgan, Mies, Bollero, Nelson, & Long, 2006; Wilkinson, Mills, Illidge, & Davies, 2012; Wittig, Ainsworth, Naidu, Karnosky, & Long, 2009). For example, it is estimated that up to 10% of maize yields are lost to O3 pollution in the United States (McGrath et al., 2015). In addition, O3 reduces global wheat yield by 85 Tg (million tonnes) and total crop yield (maize, soybean, rice and wheat combined) by 227 Tg annually (Mills et al., 2018a, 2018b). Therefore, there is strong evidence that decreased crop yield from O3 pollution portends a significant threat to global food and energy security.

As a powerful oxidant, O3 damages plants by entering the leaves through stomata. Once inside the leaf, O3 can instantly react with plasmalemma lipids to produce other reactive oxygen species (ROS), including superoxide, hydrogen peroxide and hydroxyl radical, which directly damage cells and eventually lead to programmed cell death or accelerated senescence (Ainsworth, 2017; Fiscus, Booker, & Burkey, 2005; Li, Harley, & Niinemets, 2017; Long & Naidu, 2002). In general, O3 exposure leads to reductions in the activity of ribulose‐1,5‐bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (Rubisco) in the chloroplast, thereby reducing net CO2 assimilation rate (A) and quantum yield of primary photochemistry, and increasing mitochondrial respiration which is associated with leaf senescence acceleration and yield loss (Ainsworth, 2017; Ainsworth et al., 2012; Fiscus et al., 2005; Flowers, Fiscus, Burkey, Booker, & Dubois, 2007; Li et al., 2017, 2018; Morgan, Bernacchi, Ort, & Long, 2004; Yendrek, Erice, et al., 2017). Exposure to O3 also results in decreased F v/F m, which represents the maximum quantum yield of PSII in dark‐adapted leaves, and actual photochemical efficiency of PSII (Fiscus et al., 2005; Flowers et al., 2007; Guidi, Degl'Innocentit, Martinelli, & Piras, 2009; Li et al., 2017, 2018). Previous studies have also observed that exposure to elevated O3 concentrations can alter leaf traits such as leaf mass per area (LMA) and leaf nitrogen (N) content, both of which strongly correlate to photosynthetic rate (Oikawa & Ainsworth, 2016; Oksanen, Riikonen, Kaakinen, Holopainen, & Vapaacuori, 2005). Despite the widely documented O3 effects in many species, there is less information about genotypic variation in responses to O3 in only a few species (Burkey, Booker, Ainsworth, & Nelson, 2012; Choquette, Ainsworth, Bezodis, & Cavanagh, 2020; Choquette et al., 2019; Frei, Tanaka, & Wissuwa, 2008; Yendrek, Eric, et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2017). Identifying genotypic differences in O3 tolerance is an important first step for breeding tolerant varieties that could be planted in high O3 concentrations.

Chronic O3 exposure may also cause incomplete stomatal closure, leading to greater water loss relative to net CO2 assimilation (lower water‐use efficiency) and decoupling of stomatal conductance (g s) and photosynthesis (Lombardozzi, Sparks, Bonan, & Levis, 2012; Paoletti & Grulke, 2010). Thus, understanding how O3 affects photosynthetic carbon gain and water‐use efficiency are crucial for improving O3 tolerance in crops (Ainsworth, 2017; Ainsworth, Rogers, & Leakey, 2008; Leakey et al., 2019). The Ball–Woodrow–Berry (BWB) model and Medlyn (MED) models mathematically describe the leaf‐level empirical relationship between photosynthesis, g s and environmental factors, and are widely used to predict carbon and water flux in both C3 and C4 plants under various field conditions such as different water availability and elevated CO2 (Ball, Woodrow, & Berry, 1987; Franks et al., 2018; Leakey, Bernacchi, Ort, & Long, 2006; Medlyn et al., 2011; Miner & Bauerle, 2017; Wolz, Wertin, Abordo, Wang, & Leakey, 2017). The BWB and MED models are also used to describe variation in stomatal behaviour across species or plant functional types (Franks et al., 2018; Lin et al., 2015; Wolz et al., 2017). More recently, the BWB model has been applied to estimate the effect of elevated O3 on the relationship between photosynthesis and g s. For example, elevated O3 changed the relationship between photosynthesis and g s by increasing the intercept of the BWB model in rice (Masutomi et al., 2019), but did not alter BWB model parameters in switchgrass (Li, Courbet, Ourry, & Ainsworth, 2019). However, it is unclear how elevated O3 concentration alters the parameters of these stomatal models in different sorghum lines.

Although much of our attention has been directed towards the negative responses of plant growth, development and productivity to O3 in C3 plants, the overall effects of O3 on C4 species remain less explored. Most C4 species have Kranz‐type leaf anatomy and accumulate Rubisco in the bundle sheath cells resulting in high water‐use efficiency and high productivity. In addition, C4 crops, such as corn and sorghum, may have a lower steady‐state or modelled maximal stomatal conductance, implying less O3 uptake than C3 crops such as sunflower or rice (Hoshika, Osada, de Marco, Peñuelas, & Paoletti, 2018; Lin et al., 2015; Zhen & Bugbee, 2020). Thus, C3 and C4 species might respond to O3 differently. A few studies of O3 response in maize (Zea mays) (Choquette et al., 2019, 2020; Leitao, Bethenod, & Biolley, 2007; Leitao, Maoret, & Biolley, 2007; Singh, Agrawal, Shahi, & Agrawal, 2014; Yendrek, Erice, et al., 2017; Yendrek, Tomaz, et al., 2017), switchgrass (Panicum virgatum) (Li et al., 2019) and sugarcane (Saccharum spp.) (Grantz & Vu, 2009; Grantz, Vu, Tew, & Veremis, 2012; Moura, Hoshika, Ribeiro, & Paoletti, 2018) have shown that elevated O3 negatively impacts photosynthetic performance and biomass in C4 species. With four species and numerous genotypes of maize and sugarcane examined, these studies have also shown that photosynthetic and yield responses to O3 can vary among species and genotypes (Choquette et al., 2019, 2020; Li et al., 2019; Yendrek, Erice, et al., 2017).

Here we investigated the impacts of season‐long elevated O3 exposure on leaf photosynthetic traits and capacity, respiration, chlorophyll fluorescence, leaf functional traits, biomass and nutrient composition in several sorghum lines. Studies were conducted under fully open‐air field conditions using free‐air concentration enrichment (FACE) technology, which allows for long‐term, continuous exposure to elevated O3 and monitoring of plant traits under natural conditions with little or no perturbation of other environmental factors (Ainsworth & Long, 2005; Long, Ainsworth, Rogers, & Ort, 2004). In 2018, we studied 10 genotypes of sorghum grown at ambient and elevated O3, and in 2019, we investigated five of those genotypes a second time. We further examined photosynthetic response to elevated O3 in four genotypes which were used in both 2018 and 2019 in a growth chamber experiment that minimized variation in other environmental parameters. The genotypes were chosen from a panel of 229 diverse biomass sorghum lines with significant variation in agronomic and physiological traits (Ferguson et al., 2020; Valluru et al., 2019). Given that sorghum may show a similar O3 sensitivity as maize due to their close phylogenetic relationship (Lawrence & Walbot, 2007), we tested the hypotheses that elevated O3 would: (a) reduce photosynthetic traits and capacity, such as net CO2 assimilation, stomatal conductance, the maximum carboxylation capacity of phosphoenolpyruvate and CO2 saturated photosynthetic capacity; (b) alter the relationship between stomatal conductance and photosynthesis as predicted by the BWB and MED model; and (c) decrease biomass and nutrient composition in sorghum lines. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine how elevated O3 affects photosynthesis and biomass in bioenergy sorghum genotypes, and provides important information for exploring O3 sensitivity among C4 species and identifying O3 resistant bioenergy feedstocks.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Field site, plant materials and growth condition

Sorghum (S. bicolor L.) lines were studied at the FACE facility (40°02′N, 88°14′W; www.igb.illinois.edu/soyface/) in Champaign, IL in 2018 and 2019. The soil type at the FACE site is a Drummer, which is typical in central Illinois (Ainsworth, Rogers, Nelson, & Long, 2004). Fertilizer (N, 200 kg ha−1) was applied before planting each year. Seeds of 10 sorghum genotypes (Pl148093, Pl329597, Pl452577, Pl452891, Pl453336, Pl457183A, Pl665123, Pl665129, TAM08001 and TAM17800) and five genotypes (Pl329597, Pl452891, Pl457183A, Pl665123 and TAM17800) were planted with a row spacing of 0.76 m and length of 3.96 m at a density of 5 plants m−1 in four experimental blocks at the FACE facility on 10 May [DOY 130, also referred to as days after sowing (DAS) 0], 2018 and 31 May (DOY151/DAS 0), 2019, respectively. Each block consisted of two 20 m diameter octagonal plots, with one at ambient O3 concentration (30–50 nL L−1) and another fumigated to elevated O3 concentration (~100 nL L−1). After sorghum seeds were planted, the infrastructure for O3 enrichment was installed and elevated O3 plots were fumigated starting on 25 May (DOY 145/DAS 15) in 2018 and on 10 June (DOY 161/DAS 10) in 2019 (Figure S1). Operation of O3 fumigation to the elevated plots followed the previously published protocols by Choquette et al. (2019), Morgan et al. (2004), Yendrek, Eric, et al. (2017) and Yendrek, Tomaz, et al. (2017). O3 was generated by an O3 generator (CFS‐32G; Ozonia), mixed with air and delivered to the elevated plots with FACE technology. A chemiluminescence O3 sensor (Model 49i, Thermo Scientific, MA) was used to monitor O3 concentrations. The target O3 concentration set point at the centre of the elevated plots was 100 nL L−1, with 8 hrs (10:00–18:00) fumigation per day throughout the growing season except when leaves were wet and/or when wind speed was lower than 0.5 m s−1 (Choquette et al., 2019; Yendrek, Erice, et al., 2017; Yendrek, Tomaz, et al., 2017). O3 fumigation was stopped on 13 August (DOY 225/DAS 95), 2018 and on 15 September (DOY 258/DAS 107), 2019 (Figure S1). Other weather conditions (the daily maximum and minimum air temperature and daily total precipitation) were recorded with an on‐site weather station at the FACE facility (Figure S1).

2.2. Leaf photosynthetic characteristics measurement

In situ leaf midday gas exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence were measured at three time points in both 2018 and 2019. All measurements were conducted with fully expanded sun‐exposed leaves between 11:00 and 14:00 on sunny days following the protocols described in detail by Leakey, Uribelarrea, et al. (2006), Li et al. (2019) and Yendrek, Erice, et al. (2017). Considering strong variations in physiology and structure across leaf surface in large leaves (Li et al., 2013), all of the following measurements were made in the middle part of leaves. The third or fourth fully expanded leaf was selected for the first time point measurement in both 2018 and 2019. We used the same leaf for each of the following measurements, but if that leaf had senesced, then a younger leaf was measured. In 2018, the ninth leaf was measured on 2 and 3 July (DOY 183 and 184, referred to as DOY 183/DAS 53; time point A), the 9th or 10th leaf was measured on 23 and 24 July (DOY 204 and 205, referred to as DOY 204/DAS 74; time point B), and the 10th or 11th leaf was measured on 13 August (DOY 225/DAS 95; time point C) with portable photosynthesis systems (LI‐6400, LICOR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) (Figure S1). In 2019, the 10th leaf was measured on 24 and 25 July (DOY 205 and 206, referred to as DOY 205/DAS 54; time point A), the 11th leaf was measured on 8 and 9 August (DOY 220 and 221, referred to as DOY 220/DAS 69; time point B), and the 12th leaf was measured on 23 and 24 August (DOY 235 and 236, referred to as DOY 235/DAS 84; time point C) with portable photosynthesis systems (LI‐6800, LICOR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) (Figure S1). In all cases, the conditions within the leaf chamber cuvette were set to match the environmental ambient conditions (Table S1 for details). The measurements of the net CO2 assimilation rates (A), stomatal conductance to water vapour (g s), the ratio of leaf intercellular CO2 concentration to atmospheric CO2 concentration (c i:c a) and chlorophyll fluorescence [midday PSII maximum efficiency (F v′/F m′), quantum yield of PSII (ΦPSII), electron transport rate (ETR) and coefficient of photochemical quenching (qP)] under illumination were performed after stabilization of net photosynthesis for 3 ~ 5 min. The instantaneous water‐use efficiency (iWUE) was calculated as the ratio of A to g s. In all cases, measurements were taken on two to four different individuals of each genotype within each plot.

Following in situ midday gas exchange measurements, the response of A to c i was measured on 3–6 July 2018 and on 9–22 August 2019. Two leaves from different individuals of each genotype within each plot which were used for time point A (2018) and time point B (2019) leaf gas exchange measurement were selected to measure A/c i response curves. Early in the morning, leaves from each experimental block were labelled and excised, immediately recut under water and quickly transported to the laboratory with the cut ends placed in water. Prior to A/c i curve measurement, leaves were then placed in 50 mL tubes filled with water and were exposed to saturating light levels under ambient CO2 concentration for approximately 40 min to allow stomata to open and achieve a steady‐state. After leaf enclosure, the initial conditions in the leaf cuvette were maintained at light intensity of 1800 μmol m−2 s−1, CO2 concentration of 400 μmol mol−1 and relative humidity of 65%. In 2018, the leaf chamber cuvette temperature was 26°C during the measurements and the CO2 concentration was changed sequentially as follows: 400, 300, 200, 100, 50, 400, 600, 800, 1,000, 1,200 μmol mol−1. In 2019, the cuvette temperature was 28°C and CO2 concentrations were: 400, 300, 200, 100, 50, 400, 600, 800, 1,000, 1,200 and 1,500 μmol mol−1. The maximum carboxylation capacity of phosphoenolpyruvate (V pmax) was calculated based on the initial slope of the A/c i curve (von Caemmerer, 2000), and CO2 saturated photosynthetic capacity (V max) was estimated according to the horizontal asymptote of the A/c i curve by using a four‐parameter non‐rectangular hyperbolic function. Stomatal limitation to A (S l) was estimated for each genotype in ambient and elevated O3 using mean values of A/c i curves in combination with in situ midday c i as previously described by Long and Bernacchi (2003), Markelz, Strellner, and Leakey (2011) and Yendrek, Eric, et al. (2017). Mean values of in situ midday c i for each genotype measured at time point A in 2018 and time point B in 2019 were used to calculate S l.

Following A/c i curve measurements, the leaf was removed from the chamber cuvette and dark‐adapted for at least 50 min at room temperature. Afterwards, the leaf was enclosed in the leaf cuvette for 3 to 10 min, leaf dark respiration was measured under the following environmental conditions in the cuvette: leaf temperature was 28°C, light intensity was 0 μmol m−2 s−1, CO2 concentration was 400 μmol mol−1, and relative humidity was 70% in 2018, and leaf temperature was 30°C, light intensity was 0 μmol m−2 s−1, CO2 concentration was 420 μmol mol−1 and relative humidity was 65% in 2019. To assess the impact of elevated O3 on photosystem II (PS II) activity, the minimum (F 0) and maximum (F m) dark‐adapted fluorescence yield was measured by illuminating the leaf with a saturating irradiance of 7,000 μmol quanta m−2 s−1. The spatially averaged maximum dark‐adapted quantum yield of photosystem II [F v/F m = (F m‐F 0)/F m] was calculated from F 0 and F m.

2.3. Fitting BWB and MED models to leaf‐level midday gas exchange data

The BWB model is defined as Ball et al. (1987):

| (1) |

where g s is stomatal conductance to water vapour (mol m−2 s−1), A is net CO2 assimilation rate (μmol m−2 s−1), H s is relative humidity (unitless) and C s is CO2 concentration at the bottom of the leaf boundary layer (μmol mol−1) at the leaf surface. m is the slope which is directly related to the water‐use efficiency and g 0 is the y‐axis intercept which represents a minimum stomatal conductance.

The MED model (also known as stomatal optimization model) is defined by Medlyn et al. (2011):

| (2) |

where D is the atmospheric vapour pressure deficit (kPa). g M is the model coefficient related to the slope and g 0M is a minimum stomatal conductance similar to m and g 0, respectively, in Equation (1). It should be noted that the term is large and dominates the term (1+). Therefore, the linear relationship between g s and was predicted.

The values of A, g s, H s, C s and D were obtained from LI‐6400 in 2018 or LI‐6800 in 2019 at three time point measurements of midday gas exchange. The slope (m and g M) and intercept (g 0 and g 0M) were calculated based on the linear regression of BWB model and non‐linear regression of MED model.

2.4. Biomass, C and N content

All plants were harvested from 27–31 August 2018 and on 3 October 2019 (Figure S1). Three to five individuals of each genotype from each plot were randomly selected to estimate plant biomass, C and N content. The number of leaves of each plant was counted and the total leaf area of each plant was measured by an area metre (LI‐3100C, LICOR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE). Average leaf area was calculated as total leaf area/leaf number. Leaf and stem biomass were determined by weighing dry mass after drying at 70°C for 10 days. Plant biomass reported in this study is the sum of the leaf biomass and stem biomass. Leaf dry mass per area (LMA) was calculated as the ratio of leaf dry mass to total leaf area. Leaf and stem C and N concentrations were determined using a Costech 4010 elemental analyser (Costech Analytical Technologies, Inc., Valencia, CA). Leaf N content per unit area was calculated by multiplying mass‐based N concentration by LMA.

2.5. Growth chamber experiment

To further test the effects of elevated O3 on photosynthetic traits of sorghum lines under controlled environmental conditions, a growth chamber experiment was performed. Four genotypes (Pl329597, Pl452891, Pl457183A and Pl665123) of sorghum were planted in 7.5 L plastic pots containing a commercial potting mix (Berger 6, Berger, Canada) on 4 February 2019. Three pots per each genotype were placed in eight growth chambers (Environmental Growth Chamber, Chagrin Falls, OH) under 60% relative humidity, 25/22°C day/night temperature and light intensity at plant level of 800 μmol m−2 s−1 from 08:00 to 20:00 hr. Four growth chambers were set as controls with ambient O3 concentrations (30–50 nL L−1), while another four chambers were fumigated to an average elevated O3 concentration of 150 nL L−1 from 09:00 to 17:00 after sorghum seeds germinated. During the experiment, all plants were watered and fertilized as needed to maintain optimal growth conditions. O3 was generated by an O3 generator with UV light (HVAC 560 ozone generator, Crystal Air, Langley, Canada) and was monitored by a chemiluminescence O3 sensor (Model 49i, Thermo Scientific, MA).

Gas exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence measurements were conducted on 5 March (DOY 64) and 12 March (DOY 71) after 4 and 5 weeks of fumigation on two to three fully expanded leaves (third or fourth leaf from the top) of different individuals of each genotype within each chamber using infrared gas analysers (LI‐6800). The cuvette conditions were as follows: leaf temperature was 25°C, light intensity was 1,000 μmol m−2 s−1, CO2 concentration was 400 μmol mol−1, and relative humidity was 60%. A/c i response was measured on 6 March and 7 March using the same leaves and the microclimate of the cuvette was controlled with the following parameters: leaf temperature was 25°C, light intensity was 1,000 μmol m−2 s−1 and relative humidity was 60%. CO2 concentration in the leaf cuvette was changed sequentially to 400, 300, 200, 100, 50, 400, 400, 600, 800, 1,000, 1,200 μmol mol−1. V pmax and V max were calculated, and S l was estimated using the mean values of c i measured on 5 March. Dark‐adapted leaf respiration and F v/F m were also measured with leaf temperature at 25°C, light intensity at 0 μmol m−2 s−1, CO2 concentration at 400 μmol mol−1, and relative humidity at 60%, as described above. All plants were harvested on 18 March 2019. LMA, leaf and stem C and N concentrations were determined as described above.

2.6. Statistical analysis

The main effects of O3, genotype and DOY and their interactions on gas exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence parameters were assessed by three‐way ANOVA using multiplicative models followed by Tukey's post hoc test, separately for 2018, 2019 and for the growth chamber experiment using SPSS 16.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). The effects of O3, genotype and their interactions on A/c i curve parameters and growth parameters were assessed by two‐way ANOVA, followed by Tukey's post hoc test. Linear regression was applied to the relationships between g s and c i:c a, between g s and , between g s versus and between leaf N content and LMA. The differences in slope and intercept of relationships (g s vs. c i:c a, g s vs. , and leaf N vs. LMA) between ambient and elevated O3 among sorghum lines were tested with ANCOVA. The values of MED model parameters were estimated from leaf‐level gas exchange data fitted by non‐linear regression using SigmaPlot (Systat Software Inc., Chicago, IL) and the differences in slope and intercept of MED model were tested with dummy variables. All statistical tests were considered significant at p < .05.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Leaf gas exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence response to elevated O3

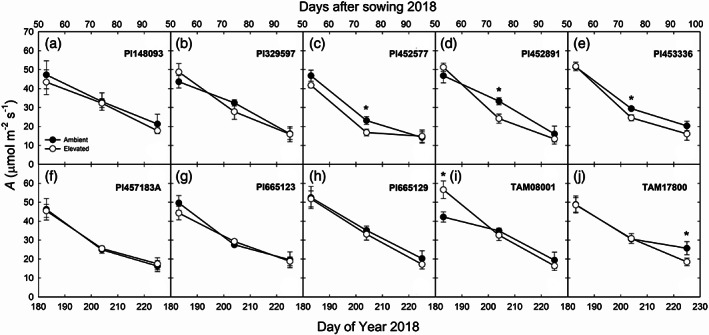

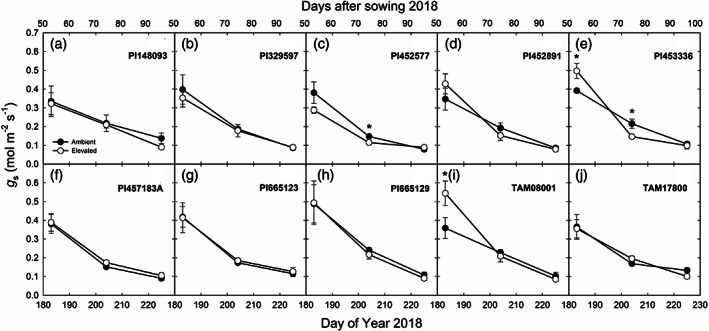

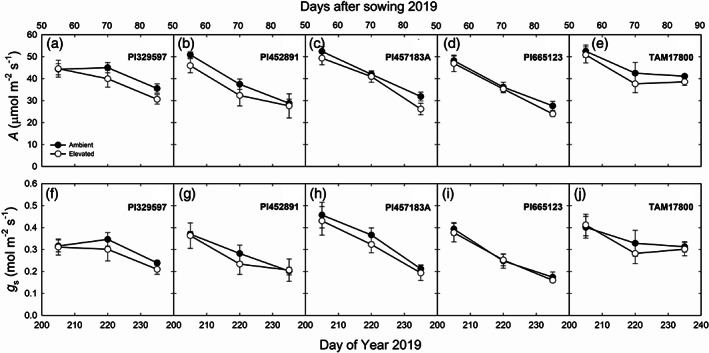

Field measurements of in situ midday A and g s showed that both parameters decreased as leaves aged in 2018 and 2019 (Figures 1, 2 and 3). The genotypes differed significantly in A and g s in both years (Table 1). A and g s were not significantly different in elevated compared to ambient O3 in most genotypes and at most time points (Figures 1, 2 and 3). c i:c a and iWUE were not consistently different in the sorghum genotypes or in ambient and elevated O3 (Table 1). In addition, genotypic and time‐dependent variation in chlorophyll fluorescence was observed for F v′/F m′, ΦPSII, ETR, and qP (Table 2). Growth in elevated O3 did not have an effect on fluorescence parameters (Table 2).

FIGURE 1.

In situ midday net CO2 assimilation rate (A) measured in 10 genotypes of sorghum grown at ambient and elevated O3 on DOY 183, 204 and 225 in 2018. Error bars show SEs (n = 4). Significant differences (p < .05) between ambient and elevated O3 are indicated by asterisk

FIGURE 2.

In situ midday stomatal conductance (g s) measured in 10 genotypes of sorghum grown at ambient and elevated O3 on DOY 183, 204 and 225 in 2018. Error bars show SEs (n = 4). Significant differences (p < .05) between ambient and elevated O3 are indicated by asterisk

FIGURE 3.

In situ midday net CO2 assimilation rate (A; a–e) and stomatal conductance (g s; f–j) measured in five genotypes of sorghum grown at ambient and elevated O3 on DOY 205, 220 and 235 in 2019. Error bars show SEs (n = 4)

TABLE 1.

Analysis of variance (F, p) of midday net CO2 assimilation rate (A), stomatal conductance (g s), the ratio of leaf intercellular CO2 concentration to atmospheric CO2 concentration (c i:c a), and instantaneous water‐use efficiency (iWUE) measured in 10 genotypes of sorghum grown at ambient and elevated O3 on DOY 183, 204 and 225 in 2018 and in 5 genotypes of sorghum grown at ambient and elevated O3 on DOY 205, 220 and 235 in 2019 at the FACE facility.

| A (μmol m−2 s−1) | g s (mol m−2 s−1) | c i: c a | iWUE (μmol mol−1) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 2019 | 2018 | 2019 | 2018 | 2019 | 2018 | 2019 | |

| O3 | 2.62, 0.11 | 7.93, 0.006 | 0.001, 0.97 | 2,09, 0.15 | 3.83, 0.052 | 1.53, 0.22 | 3.38, 0.067 | 0.001, 0.98 |

| Genotype (G) | 3.41, 0.001 | 5.99, <0.001 | 2.31, 0.018 | 4.36, 0.003 | 1.86, 0.06 | 4.06, 0.005 | 1.48, 0.16 | 2.59, 0.042 |

| O3 × G | 0.53, 0.85 | 0.081, 0.99 | 0.55, 0.84 | 0.11, 0.98 | 0.64, 0.76 | 0.65, 0.63 | 0.75, 0.67 | 0.54, 0.71 |

| Day of year (DOY) | 412.8, <0.001 | 86.7, <0.001 | 281.6, <0.001 | 43.9, <0.001 | 60.3, <0.001 | 1.41, 0.25 | 109.1, <0.001 | 2.62, 0.079 |

| O3 × DOY | 1.68, 0.19 | 0.18, 0.83 | 1.17, 0.31 | 0.29, 0.75 | 0.013, 0.99 | 1.76, 0.18 | 0.014, 0.99 | 1.49, 0.23 |

| G × DOY | 1.06, 0.40 | 2.66, 0.011 | 1.14, 0.32 | 2.39, 0.022 | 1.34, 0.17 | 2.27, 0.029 | 1.64, 0.054 | 2.28, 0.029 |

| O3 × G × DOY | 0.93, 0.55 | 0.31, 0.96 | 0.91, 0.57 | 0.12, 0.99 | 1.36, 0.16 | 0.37, 0.94 | 1.64, 0.055 | 0.31, 0.96 |

Note: Significant effects are shown in boldface.

TABLE 2.

Analysis of variance (F, p) of midday PSII maximum efficiency (F v′/F m′), quantum yield of PSII (ΦPSII), electron transport rate (ETR), and coefficient of photochemical quenching (qP) measured in 10 genotypes of sorghum grown at ambient and elevated O3 on DOY 183, 204 and 225 in 2018 and in 5 genotypes of sorghum grown at ambient and elevated O3 on DOY 205, 220 and 235 in 2019 at the FACE facility.

| F v′/F m′ | ΦPSII | ETR (μmol m−2 s−1) | qP | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 2019 | 2018 | 2019 | 2018 | 2019 | 2018 | 2019 | |

| O3 | 2.91, 0.09 | 1.12, 0.29 | 2.51, 0.12 | 1.28, 0.26 | 2.59, 0.11 | 1.26, 0.26 | 1.47, 0.23 | 0.86, 0.36 |

| Genotype (G) | 2.96, 0.003 | 1.63, 0.17 | 2.21, 0.024 | 6.12, 0.001 | 2.27, 0.02 | 7.74, <0.001 | 2.47, 0.011 | 6.40, <0.001 |

| O3 × G | 1.35, 0.22 | 0.45, 0.78 | 0.32, 0.97 | 1.25, 0.30 | 0.33, 0.97 | 1.24, 0.30 | 0.44, 0.91 | 1.79, 0.14 |

| Day of year (DOY) | 0.85, 0.43 | 35.5, <0.001 | 340.9, <0.001 | 41.2, <0.001 | 355.7, <0.001 | 68.4, <0.001 | 343.5, <0.001 | 20.5, <0.001 |

| O3 × DOY | 1.39, 0.25 | 0.27, 0.76 | 0.73, 0.48 | 0.67, 0.52 | 0.77, 0.47 | 0.82, 0.44 | 0.69, 0.50 | 1.01, 0.37 |

| G × DOY | 0.63, 0.87 | 1.87, 0.074 | 1.17, 0.29 | 2.16, 0.038 | 1.21, 0.26 | 2.97, 0.005 | 1.37, 0.15 | 2.13, 0.041 |

| O3 × G × DOY | 0.53, 0.94 | 0.23, 0.98 | 0.67, 0.84 | 0.32, 0.96 | 0.68, 0.83 | 0.29, 0.97 | 0.54, 0.94 | 0.30, 0.97 |

Note: Significant effects are shown in boldface.

In the growth chamber experiment, there was significant genotypic and time‐dependent variation in the photosynthetic traits and chlorophyll fluorescence across four genotypes of sorghum (Table 3). Elevated O3 significantly reduced g s in Pl665123 but increased ΦPSII, ETR and qP in Pl457183A on DOY 64 (p < .05; Figure S2). However, elevated O3 did not alter photosynthetic traits and chlorophyll fluorescence across all genotypes (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Analysis of variance (F, p) of net CO2 assimilation rate (A), stomatal conductance (g s), the ratio of leaf intercellular CO2 concentration to atmospheric CO2 concentration (c i:c a), and instantaneous water‐use efficiency (iWUE), PSII maximum efficiency (F v′/F m′), quantum yield of PSII (ΦPSII), electron transport rate (ETR) and coefficient of photochemical quenching (qP) measured in four genotypes of sorghum grown at ambient and elevated O3 on DOY 64 and 71 in 2019 in the growth chambers

| A (μmol m−2 s−1) | g s (mol m−2 s−1) | c i: c a | iWUE (μmol mol−1) | F v′/F m′ | ΦPSII | ETR (μmol m−2 s−1) | qP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O3 | 0.014, 0.91 | 2.34, 0.13 | 5.09, 0.030 | 3.79, 0.059 | 0.36, 0.55 | 0.54, 0.47 | 0.54, 0.47 | 0.84, 0.36 |

| Genotype (G) | 4.38, 0.010 | 5.78, 0.002 | 3.96, 0.015 | 4.82, 0.006 | 7.69, <0.001 | 3.02, 0.042 | 3.02, 0.042 | 5.05, 0.005 |

| O3 × G | 0.86, 0.47 | 0.93, 0.44 | 0.28, 0.84 | 0.10, 0.96 | 1.34, 0.28 | 0.91, 0.45 | 0.91, 0.45 | 1.20, 0.32 |

| Day of year (DOY) | 37.5, <0.001 | 32.3, <0.001 | 0.037, 0.85 | 0.11, 0.74 | 13.9, 0.001 | 9.46, 0.004 | 9.46, 0.004 | 4.84, 0.034 |

| O3 × DOY | 0.12, 0.74 | 0.77, 0.39 | 0.0040, 0.95 | 0.033, 0.86 | 0.26, 0.61 | 0.97, 0.33 | 0.97, 0.33 | 0.90, 0.35 |

| G × DOY | 2,46, 0.077 | 1.66, 0.19 | 0.35, 0.79 | 0.32, 0.81 | 7.04, 0.001 | 4.61, 0.008 | 4.61, 0.008 | 2.70, 0.059 |

| O3 × G × DOY | 0.33, 0.81 | 0.68, 0.57 | 0.78, 0.51 | 0.93, 0.44 | 0.55, 0.65 | 0.40, 0.75 | 0.40, 0.75 | 0.28, 0.84 |

Note: Significant effects are shown in boldface.

3.2. Changes in A/c i curves, leaf respiration and dark‐adapted chlorophyll fluorescence

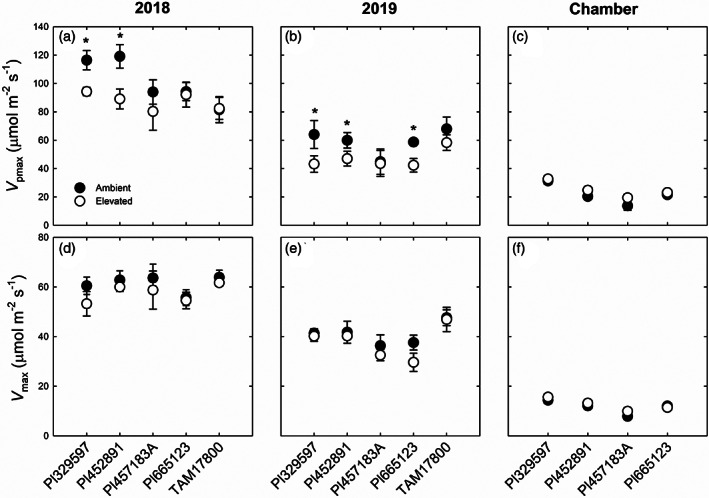

Elevated O3 led to a significant decrease in the maximum carboxylation capacity of phosphoenolpyruvate (V pmax) in both 2018 and 2019 (Table 4), with post hoc tests showing that V pmax was significantly lower in elevated O3 in Pl329597 and Pl452891 in both years (p < .05; Figure 4a,b). However, there was no significant effect of O3 on the CO2 saturated photosynthetic capacity (V max) in five genotypes of sorghum measured at FACE in 2018 and 2019 (Figure 4d,e and Table 4). There was no significant effect of elevated O3 on V pmax or V max in any genotype in the growth chamber experiment, where photosynthetic capacity was significantly lower than those measured in the field (Figure 4c,f).

TABLE 4.

Analysis of variance (F, p) of the maximum carboxylation capacity of PEPC (V pmax) and CO2‐saturated photosynthetic rate (V max) measured in five genotypes of sorghum grown at ambient and elevated O3 at FACE in 2018 and 2019 and in four genotypes of sorghum grown at ambient and elevated O3 in growth chamber

| 2018 | 2019 | Chamber | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| V pmax | O3 | 6.58, 0.016 | 10.2, 0.003 | 5.09, 0.036 |

| Genotype (G) | 3.09, 0.03 | 2.75, 0.047 | 21.8, <0.001 | |

| O3 × G | 1.25, 0.311 | 0.37, 0.83 | 0.55, 0.65 | |

| V max | O3 | 1.93, 0.18 | 2.13, 0.16 | 2.35, 0.14 |

| G | 1.24, 0.32 | 5.72, 0.002 | 17.5, <0.001 | |

| O3 × G | 0.17. 0.95 | 0.41, 0.80 | 0.82, 0.50 |

Note: Significant effects are shown in boldface.

FIGURE 4.

Maximum carboxylation capacity of PEPC (V pmax, a–c) and CO2‐saturated photosynthetic rate (V max, d–f) measured in five genotypes of sorghum grown at ambient and elevated O3 in 2018 (a,d) and 2019 (b,e), and in four genotypes of sorghum grown at ambient and elevated O3 in growth chamber (c,f). Error bars show SEs (n = 4). Significant differences (p < .05) between ambient and elevated O3 are indicated by asterisk

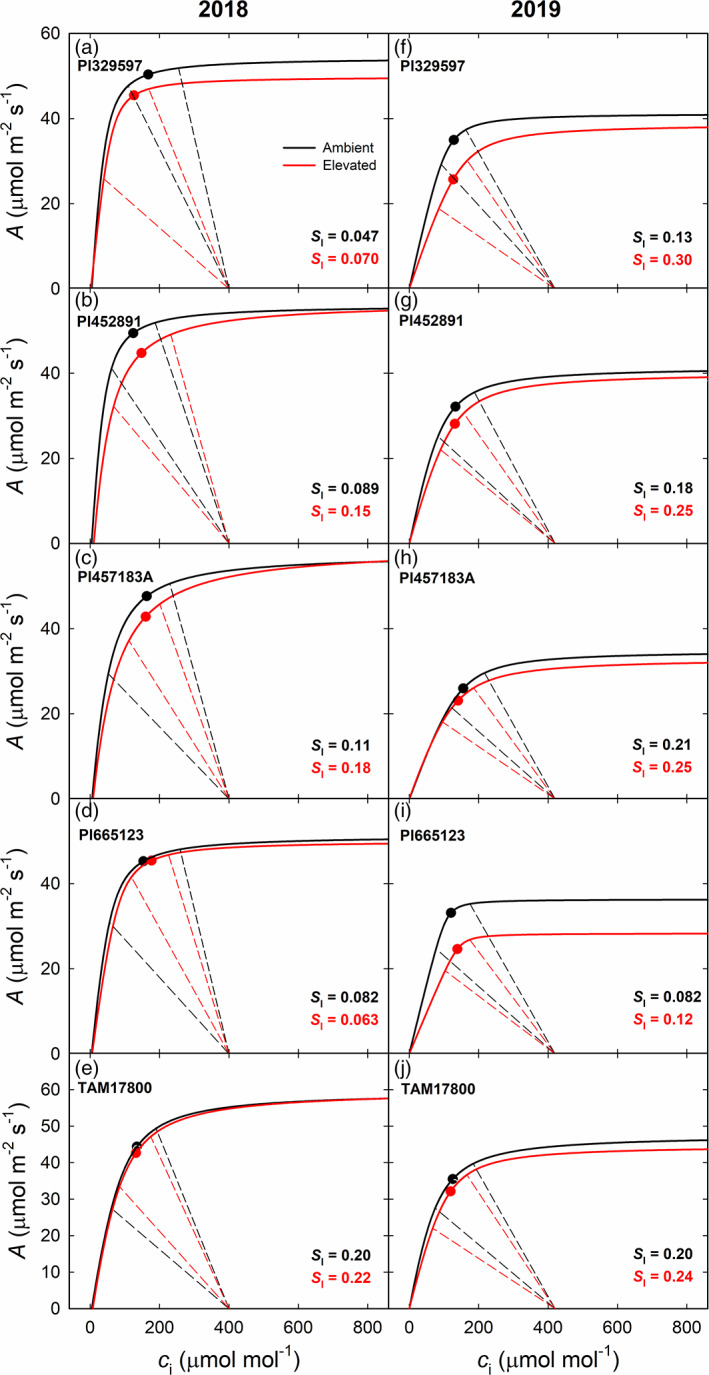

Stomatal limitation to A (S l) was also calculated from A/c i curves in combination with in situ midday c i. The mean c i was below the inflexion point of the A/c i curve in all genotypes in both years except for Pl329597 in 2018 (Figure 5). S l varied from 0.047 in Pl329597 to 0.20 in TAM17800 in ambient O3 conditions in 2018, and from 0.063 in Pl665123 to 0.22 in TAM17800 in elevated O3 (Figure 5a–e). S l varied about 2.5‐fold across genotypes in both ambient and elevated O3 in 2019 (Figure 5f–j). For most genotypes, the range of S l estimated in ambient and elevated O3 were completely overlapping, suggesting that there was not a biologically significant change in S l in elevated O3. In the growth chamber experiment, the mean c i was above the inflexion point of the A/c i curve in all genotypes under both ambient and elevated O3 and again the range of estimated S l values was totally overlapping in ambient and elevated O3 (Figure S3).

FIGURE 5.

Summary of A/c i response curves (solid lines) and CO2 supply functions (dashed lines) for five genotypes of sorghum grown at ambient O3 (black lines) and elevated O3 (red lines) in 2018 (a‐e) and 2019 (f‐j). The dashed lines represent the observed maximum and minimum midday c i, and the points indicate the mean values (n = 4) of midday c i which was measured under CO2 concentration of 400 μmol mol−1 at time point A in 2018 and 420 μmol mol−1 at time point B in 2019. Stomatal limitation (S l) for each genotype under ambient and elevated O3 is reported in each panel. For all A/c i regressions, r 2 > 0.98 and p < .0001 [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Leaf respiration and maximum dark‐adapted quantum yield of photosystem II (F v/F m) were not significantly different between ambient and elevated O3 or across 5 genotypes in 2018 and 2019 at the FACE experiment (Figure S4a,b,d,e and Table S4). A significant decrease in F v/F m in Pl457183A was detected in the growth chambers, resulting in a significant O3 × genotype treatment interaction (Figure S4f and Table S2).

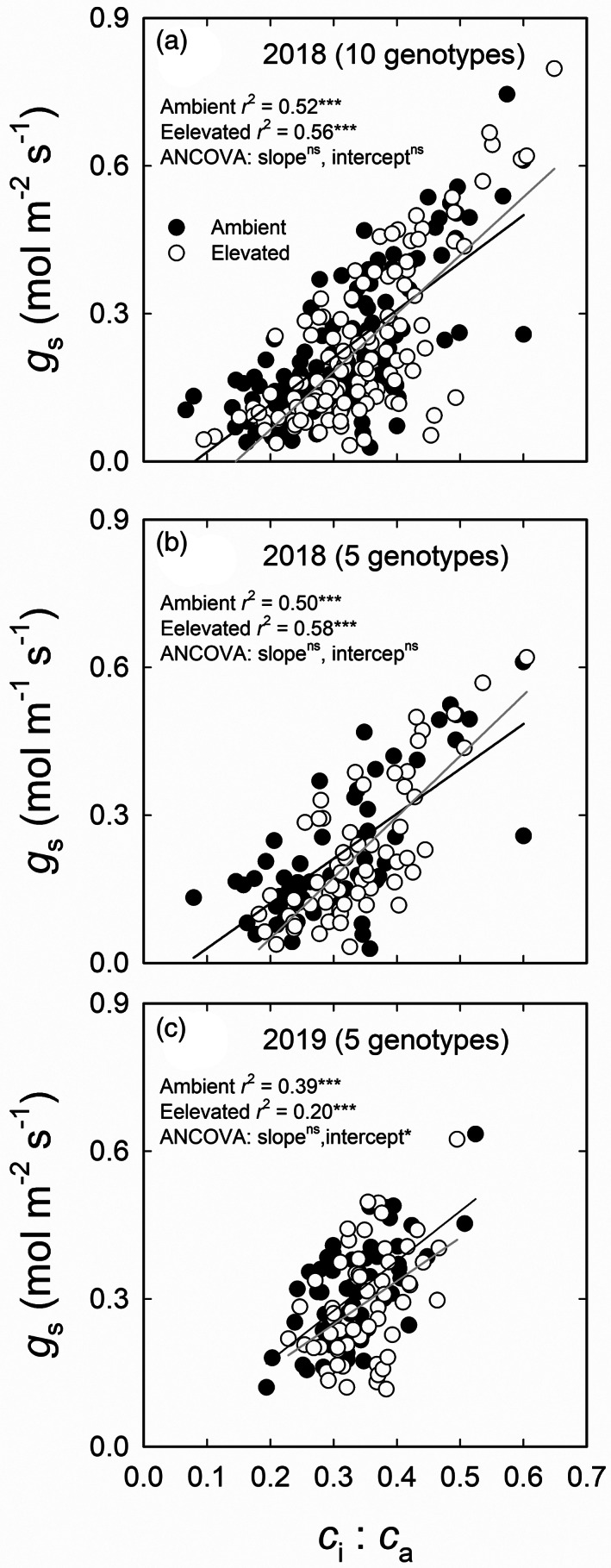

3.3. Relationship between g s and c i:c a

c i:c a showed a highly significant positive correlation with g s across 10 genotypes and 3 measurement dates under both ambient and elevated O3 in 2018 (p < .001; Figure 6a). The correlation was also significant when the data were subset to examine only the five genotypes that were measured in both 2018 and 2019 (p < .001; Figure 6b,c). In both years, elevated O3 did not alter the slope of the relationship between g s and c i:c a (Figure 6). A significant effect of O3 on the intercept was observed only in 2019 with all five genotypes (p < .05; Figure 6c). The relationship between g s and c i:c a was also tested at different time points to assess how prolonged exposure to O3 may have impacted the correlation. The correlation between g s and c i:c a weakened over time in both 2018 and 2019 (Figure S5). A significant decrease in intercept was detected only in time point C in 2019 (p < .05; Figure S5i). Independent analysis of the genotypes also revealed variation in the correlation between g s and c i:c a, but O3 did not alter the slopes or intercepts of the relationship in any individual genotype (Figure S6).

FIGURE 6.

The relationship between stomatal conductance (g s) and the ratio of leaf intercellular CO2 concentration to atmospheric CO2 concentration (c i:c a) in 10 genotypes (a) and 5 genotypes (b) of sorghum grown under ambient and elevated O3 measured on DOY 183, 204 and 225 in 2018 and in 5 genotypes (c) of sorghum grown under ambient and elevated O3 measured on DOY 205, 220 and 235 in 2019. The data were fitted by linear regressions. ns, no significant difference (p > .05); *p < .05; ***p < .001

3.4. Comparison of BWB and MED model parameters across genotypes

The BWB and MED models both empirically predict the relationship between g s and A under varying environmental conditions. g s was strongly correlated with and across all genotypes or different measurement dates in both ambient and elevated O3 (p < .001; Figures S7 and S8). Growth under elevated O3 did not alter the slope or intercept of the BWB and MED models across all genotypes in 2018 (Table 5), but a significant decrease in the intercept was observed in the BWB model in 2019 for five genotypes (p < .05; Table 5). In the growth chamber, both the slope and intercept were significantly affected by the O3 treatment across four genotypes in BWB and MED models (p < .05; Table 5). For the FACE experiments, there was no statistical difference in the slope or intercept of the BWB and MED models in ambient and elevated O3 measured in time point A in either year (Table S3). For both models, a reduction of the intercept of O3 exposed leaves was found in the measurement of 5 genotypes at time point B in 2018 (p < .05; Table S3) and 10 or 5 genotypes at time point C, when leaves were older in 2018 (p < .05; Table S3). Elevated O3 significantly decreased the intercept of BWB model, but increased the slope of MED model in the five genotypes measured in common at time point C in both 2018 and 2019 (Table S3). g s also showed a highly significant correlation with and in each genotype measured in both years, but a significant effect of O3 on the slope of both models was only observed in Pl329597 (p < .01; Table S4) in 2018 and Pl452891 (p < .05; Table S4) in 2019. In addition, O3 reduced the slope of the MED model in Pl452577 in 2018 (p < .05; Table S4). O3 did not alter the intercept of either the BWB or MED model in any individual genotype in 2018 or 2019 (Table S4). Both slope and intercept varied substantially among all genotypes in both models in 2018 and 2019. In 2018, the BWB model slope ranged across genotypes from 4.04 ± 0.43 to 5.46 ± 0.60 under ambient and from 3.44 ± 0.24 to 5.33 ± 0.70 under elevated O3, and the MED model slope varied from 1.25 ± 0.23 to 2.25 ± 0.26 under ambient and from 0.88 ± 0.15 to 2.13 ± 0.42 under elevated O3 (Table S4). In 2019, the slope of BWB model varied among genotypes from 3.23 ± 0.33 to 4.85 ± 0.64 and from 3.91 ± 0.28 to 4.50 ± 0.39 under ambient and elevated O3, respectively, and the MED model slope varied from 1.44 ± 0.27 to 3.37 ± 0.61 under ambient and from 2.10 ± 0.26 to 2.90 ± 0.30 under elevated O3 (Table S4).

TABLE 5.

BWB and MED model slope coefficients and minimum stomatal conductance derived from leaf‐level midday gas exchange measurements in 2018 and 2019 at the FACE and in 2019 in the growth chambers

| 2018 (10 genotypes) | 2018 (5 genotypes) | 2019 | Chamber | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BWB | Slope (±SE) | Amb | 4.64 (0.14) | 4.57 (0.20) | 3.99 (0.22) | 2.86 (0.38) |

| Ele | 4.57 (0.12) | 4.34 (0.15) | 4.22 (0.14) | 2.03 (0.28) | ||

| Intercept (±SE) | Amb | −0.016 (0.0084) | −0.017 (0.012) | −0.037 (0.020) | 0.0036 (0.011) | |

| Ele | −0.0057 (0.0075) | 0.0034 (0.0084) | −0.041 (0.011) | 0.013 (0.0086) | ||

| MED | Slope (±SE) | Amb | 1.62 (0.085) | 1.57 (0.12) | 2.18 (0.19) | 1.16 (0.30) |

| Ele | 1.65 (0.076) | 1.52 (0.087) | 2.35 (0.16) | 0.50 (0.38) | ||

| Intercept (±SE) | Amb | −0.052 (0.0091) | −0.052 (0.013) | −0.12 (0.025) | −0.00060 (0.012) | |

| Ele | −0.045 (0.0082) | −0.036 (0.0091) | −0.12 (0.019) | 0.011 (0.0090) |

Note: Significant differences (p < .05) between ambient and elevated O3 are shown in boldface.

Abbreviations: BWB, Ball–Woodrow–Berry; MED, Medlyn.

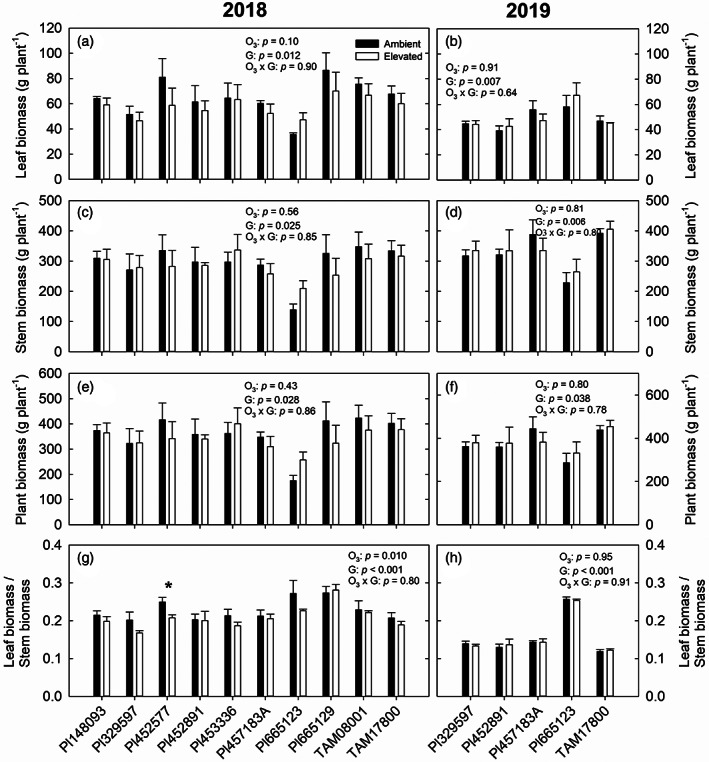

3.5. Elevated O3 had no effect on plant biomass but changed nutrient composition

Leaf number, leaf size and leaf biomass, stem biomass and plant height varied greatly across different genotypes in 2018 and 2019 (Figures 7 and S9). In 2018, elevated O3 significantly decreased the ratio of leaf biomass to stem biomass in Pl452577 (p < .05; Figure 7g) and average leaf area in Pl148093 (p < .05; Figure S9e), but increased leaf number and total leaf area in Pl665123 (p < .05 and p < .001; Figure S9a,c). Across all genotypes in 2018, the effect of elevated O3 was only observed in the ratio of leaf biomass to stem biomass (Figure 7g) and total leaf area (Figure S9c) and there was no significant elevated O3 × genotype interaction in any trait (Figures 7 and S9). These traits were not significantly different between ambient and elevated O3 across five genotypes in 2019 (Figures 7 and S9).

FIGURE 7.

Leaf biomass (a,b), stem biomass (c,d), plant biomass (e,f) and the ratio of leaf biomass to stem biomass (g,h) measured in sorghum genotypes grown at ambient and elevated O3 in 2018 (a,c,e,g) and 2019 (b,d,f,h). Error bars show SEs (n = 4). Significant differences (p < .05) between ambient and elevated O3 are indicated by asterisk

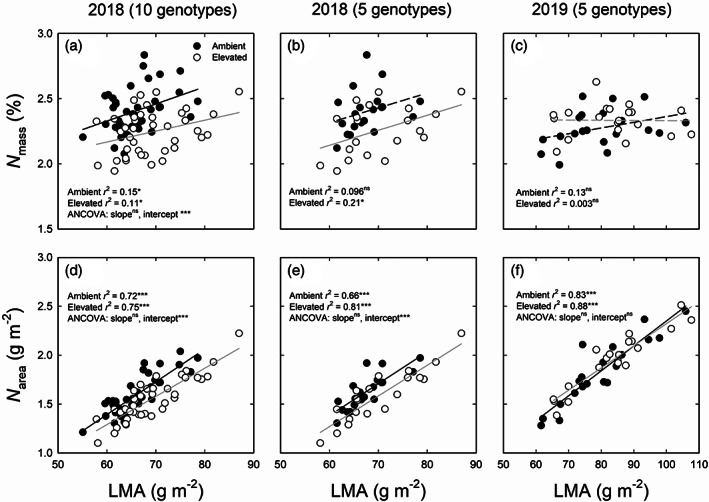

Genotypic variation in leaf mass per area (LMA), leaf and stem C and N was found in 2018, 2019 and the growth chamber experiment (Table 6). The elevated O3 impact on LMA, leaf and stem C and N in 2018 was not consistent with the lack of an effect on these traits in 2019 and in the growth chamber experiment (Table 6). In particular, leaf N tended to be greater in ambient compared to elevated O3 in 2018 (Figure 8a,b,d,e). The correlation between LMA and leaf N was examined on a mass (N mass) and an area (N area) basis. Both mass and area‐based concentrations of leaf N were positively correlated with LMA (Figure 8). However, correlations between LMA and N area were stronger than those between LMA and N mass (Figure 8). Elevated O3 decreased the intercept of the relationship between LMA and N area (Figure 8a) and between LMA and N mass (Figure 8d,e) in 2018 but did not change either the slope or the intercept of the correlation in five genotypes in 2019 (Figure 8f). In addition, no significant correlations were observed between LMA and N mass under ambient conditions and between LMA and N area under ambient and elevated O3 in the growth chamber experiment (Figure S10).

TABLE 6.

Analysis of variance (F, p) of LMA, leaf and stem nitrogen and carbon content measured in 10 genotypes of sorghum grown at ambient and elevated O3 in 2018 and in 5 genotypes of sorghum grown at ambient and elevated O3 in 2019

| LMA (g m−2) | Leaf N (g m−2) | Leaf N (%) | Leaf C (%) | Leaf C: N | Stem N (%) | Stem C (%) | Stem C: N | Leaf N/Stem N | Leaf C/Stem C | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | O3 | 7.38, 0.009 | 1.66, 0.203 | 39.62, <0.001 | 4.46, 0.039 | 44.68, <0.001 | 12.34, 0.001 | 4.83, 0.032 | 13.60, <0.001 | 4.40, 0.040 | 0.005, 0.94 |

| Genotype (G) | 4.62, <0.001 | 10.24, <0.001 | 10.822, <0.001 | 24.66, <0.001 | 7.62, <0.001 | 7.92, <0.001 | 5.02, <0.001 | 5.90, <0.001 | 8.33, <0.001 | 12.5, <0.001 | |

| O3 × G | 0.61, 0.78 | 0.81, 0.61 | 0.91, 0.52 | 0.46, 0.89 | 0.795, 0.62 | 0.78, 0.63 | 1.29, 0.26 | 0.81, 0.61 | 0.44, 0.91 | 0.82, 0.60 | |

| 2019 | O3 | 3.12, 0.084 | 6.09, 0.020 | 2.76, 0.11 | 1.20, 0.28 | 2.98, 0.094 | 2.33, 0.14 | 0.001, 0.98 | 3.27, 0.081 | 1.48, 0.23 | 0.71, 0.40 |

| G | 17.9, <0.001 | 28.9, <0.001 | 3.34, 0.021 | 134.1, <0.001 | 3.73, 0.014 | 38.9, <0.001 | 13.2, <0.001 | 38.3, <0.001 | 42.0, <0.001 | 47.9, <0.001 | |

| O3 × G | 0.47, 0.76 | 1.02, 0.41 | 1.74, 0.17 | 0.13, 0.97 | 1.68, 0.18 | 0.38, 0.82 | 0.22, 0.93 | 0.88, 0.49 | 1.58, 0.21 | 0.13, 0.97 | |

| Chamber | O3 | 4.70, 0.043 | 5.61, 0.029 | 1.06, 0.32 | 2.42, 0.14 | 1.14, 0.30 | 1.25, 0.28 | 3.14, 0.092 | 1.91, 0.18 | 0.15, 0.70 | 7.47, 0.013 |

| G | 15.8, <0.001 | 0.89, 0.46 | 2.07, 0.14 | 4.73, 0.013 | 2.22, 0.12 | 7.57, 0.002 | 18.6, <0.001 | 13.1, <0.001 | 9.44, <0.001 | 25.7, <0.001 | |

| O3 × G | 4.65, 0.013 | 1.59, 0.22 | 0.99, 0.42 | 6.82, 0.003 | 0.50, 0.69 | 0.31, 0.82 | 2.82, 0.067 | 0.94, 0.44 | 0.77, 0.53 | 10.1, <0.001 |

Note: Significant effects are shown in boldface.

Abbreviation: LMA, leaf mass per area.

FIGURE 8.

The relationship between leaf dry mass per area (LMA) and leaf nitrogen content expressed on a mass basis (LMA and N mass, a–c), and on an area basis (LMA and N area, d–f) in 10 genotypes (a,d) and 5 genotypes (b,e) of sorghum grown under ambient and elevated O3 measured in 2018 and in 5 genotypes (c,f) of sorghum grown under ambient and elevated O3 measured in 2019. The data were fitted by linear regressions. Significant correlations are indicated by solid lines. ns, no significant difference (p > .05); *p < .05; ***p < .001

4. DISCUSSION

Sorghum (S. bicolor L.), a highly productive C4 grass used for biofuel production, has not been examined for response to elevated O3 in the field. In this study, we exposed different genotypes of biomass sorghum to elevated O3 over two growing seasons in the field using FACE technology, and in a growth chamber experiment to test sorghum response to O3 in the absence of other stresses common in field environments. We found evidence of considerable variation among sorghum genotypes in photosynthesis, plant biomass and nutrient concentrations. Across all genotypes, we also found that elevated O3 did not alter photosynthetic characteristics, the BWB and MED relationship or plant biomass, despite reduced V pmax and decreased leaf nitrogen in 2018. However, O3 effects on nutrient composition were not consistent in both years at the FACE facility or with growth chamber measurements.

4.1. Effects of elevated O3 on photosynthetic characteristic

O3 is well known to negatively impact plant growth, development and productivity (e.g. Ainsworth et al., 2012; Fiscus et al., 2005; Morgan et al., 2006; Wilkinson et al., 2012; Wittig et al., 2009). Prior FACE studies with maize and switchgrass found that ~100 nL L−1 O3 significantly reduced net photosynthetic carbon assimilation (A) and stomatal conductance (g s) (Choquette et al., 2019, 2020; Li et al., 2019; Yendrek, Erice, et al., 2017). However, we found that elevated O3 (~100 nL L−1) did not alter either A or g s in most genotypes across three time points, and two field growing seasons (Figures 1, 2 and 3). In addition, there was no evidence of any effect of elevated O3 on midday chlorophyll fluorescence across all genotypes (Table 2), which is not consistent with prior observation with switchgrass at FACE (Li et al., 2019). Therefore, these results indicate that sorghum might have a greater O3 tolerance than other C4 species. However, historical maize yield loss due to O3 was greater in dry years with high temperatures (McGrath et al., 2015). This suggests that O3 sensitivity in maize is highly dependent on environmental conditions such as water availability and growing season temperature. Further work is needed to understand how O3 sensitivity varies across genotypes and C4 species in side‐by‐side experiments.

Long‐term exposure has been positively correlated with leaf damage and loss of stomatal control or stomatal sluggishness in ageing leaves (Paoletti & Grulke, 2010). However, both c i:c a and iWUE remained constant (Table 1) suggesting that there was no uncoupling of A and g s and stomatal limitations to A (S l) were minimized (Figure 5). It has been suggested that reductions in photosynthesis to O3 in soybean and maize were determined by biochemical limitation, not stomatal limitation (Choquette et al., 2020; Morgan et al., 2004; Yendrek, Eric, et al., 2017). In this study, elevated O3 led to increased S l in both years (Figure 5). However, the range of estimated S l values in ambient and elevated O3 completely overlapped, suggesting that changes in S l in elevated O3 were not biologically significant. There was a surprising result that V pmax was reduced by elevated O3 in Pl329597, Pl452891 and Pl665123 (Figure 4), yet this change in capacity did not result in lower photosynthetic performance. This could be because changes in V pmax were not sufficient to limit gas exchange. Furthermore, quantum yield of primary photochemistry in dark‐adapted leaves (F v/F m) did not change in response to elevated O3 in all genotypes (Figure S4 and Table S2), suggesting that photosystem II photochemistry was not damaged by a season‐long O3 exposure. In fact, no visible foliar injury was observed due to O3 on all genotypes in either year. Consistent with FACE studies, the growth chamber measurements provide further evidence that sorghum was tolerant to elevated O3, with no changes in photosynthetic capacity measured.

The correlation between CO2 fixation and g s and empirical relationship between A and g s are crucial in understanding how elevated O3 impairs photosynthetic capacity (Choquette et al., 2019; Li et al., 2019; Masutomi et al., 2019). c i:c a was positively correlated with g s in ambient and elevated O3 (Figure 6). Growth at elevated O3 reduced the intercept of relationship between c i:c a and g s across all genotypes in 2019 (Figure 6c). However, elevated O3 did not alter the slope or intercept of the relationship within each genotype in 2018 and 2019 (Figure S6). This further suggests that the genotypes have a similar O3 response.

The BWB and MED models provide information about the leaf‐level empirical relationship between A and g s with environmental factors (Ball et al., 1987; Medlyn et al., 2011). Previous studies reported that the BWB relationship was altered by elevated O3 in O3‐sensitive rice cultivars (Masutomi et al., 2019), but it was not affected in switchgrass (Li et al., 2019). Although the MED model has been increasingly used to determine terrestrial stomatal behaviour at a global scale because of its application of optimization principles (Franks et al., 2018; Lin et al., 2015), whether elevated O3 alters the MED parameters has not been tested. In this study, we investigated the slope parameter in both the BWB and MED models, and found that elevated O3 did not alter the slope of either model in any sorghum genotype across the growing season (Tables 5 and S3). This is consistent with no changes in iWUE at elevated O3 in 2018 and 2019 (Table 1). In addition, there was a similar O3‐induced reduction in the slope of both models as leaves aged in 2018 (Table S3). Furthermore, the changes in intercept by O3 were very similar when using either the BWB or MED model across all genotypes or all time point measurements (Tables 5, S3 and S4). Although the slope and intercept of both models varied substantially among all genotypes under ambient and elevated O3 in both 2018 and 2019, such similarities of BWB and MED suggest that both models would have a similar performance when fitted to leaf‐level midday gas exchange data and that all genotypes respond to O3 similarly. This is consistent with recent side‐by‐side comparisons in the predictive strength of the BWB and MED models for other species and environmental conditions (Franks et al., 2018; Wolz et al., 2017).

4.2. Impact of elevated O3 on plant biomass and nutrient composition

A successful bioenergy crop requires biomass yield stability under a changing climate. How elevated O3 alters plant biomass in C4 crops is currently unclear. Previous studies have shown that O3 significantly reduced plant biomass in growth chamber maize and greenhouse sugarcane (Grantz & Vu, 2009; Leitao, Bethenod, & Biolley, 2007). In our study, we observed no changes in plant biomass to O3 across all sorghum genotypes in both years in the field (Figure 7), consistent with a past study of switchgrass using FACE technology (Li et al., 2019). This further suggests that sorghum is tolerant to O3 and biomass yield stability will not be influenced by O3 pollution. Since enclosure experiments may amplify downregulation of plant production in response to O3 due to differences in growth conditions including limited soil volume in pots and greater exposure of leaves O3 based on air flow within chambers (Ainsworth & Long, 2005; Long et al., 2004), further studies are needed to gain an insight into the effect of elevated O3 on plant biomass in more C4 species in the field.

Nitrogen (N) is a primary component of the nucleotides and proteins that are essential for photosynthetic apparatus and reactions (Evans, 1989). Elevated O3 typically reduces leaf N in many species, with the negative effects being counteracted by additional N treatment (Oikawa & Ainsworth, 2016; Yendrek, Leisner, & Ainsworth, 2013). In this study, reductions in both leaf and stem N to O3 in 2018 were observed (Table 6). Interestingly, the decline in N did not cause any changes in photosynthetic performance and plant biomass (Figure 7). In addition, no differences in leaf and stem N were found in ambient and elevated O3 across five genotypes in 2019 which is consistent with a previous study on switchgrass (Li et al., 2019). Given the different O3 effects on leaf and stem N in both years, it could be because LMA was only altered by O3 in 2018 (Table 6). In addition, sorghum genotypes under elevated O3 showed lower leaf N at a given LMA in 2018, implying higher photosynthetic N use efficiency compared to plants under ambient O3 (Figure 8).

Taken together, we found strong evidence of O3 tolerance in a range of sorghum biomass genotypes. In addition, our results suggest that sorghum might have a greater O3 tolerance than other C4 species. But what mechanisms underlie the great O3 tolerance in sorghum biomass genotypes? Morgan et al. (2004) suggested that O3 concentration varied with leaf position in the canopy because upper canopy leaves may have higher stomatal conductance and O3 uptake than lower canopy leaves. Biomass sorghum continuously added vegetative tissue throughout the growing season in central Illinois because of its photoperiod sensitivity (Maughan et al., 2012; Rooney & Aydin, 1999), in contrast to maize, which stops vegetative growth ~9 to 10 weeks after emergence (Bollero, Bullock, & Hollinger, 1996). Continuous development of vegetative tissue may be one of the reasons that biomass sorghum was observed to be more O3‐tolerant than maize grown at the same field site (Yendrek, Eric, et al., 2017). However, sorghum genotypes were also found tolerant to O3 in the growth chamber measurements where all leaves were exposed to similar O3 concentrations. This indicates that other factors contribute significantly to defence against O3 stress in sorghum.

It has been suggested that the detoxification capacity for O3 in plants is associated with the capacity of photosynthetic CO2 assimilation which provides energy for detoxification and repair and products for antioxidant biosynthesis (Massman, 2004; Musselman & Massman, 1999; Smirnoff, 2000). In addition, the balance between A and g s was assumed as a key factor determining the extent of the O3 response (Massman, 2004). Sorghum is less susceptible to drought than maize and has higher water‐use‐efficiency than other C4 crops (Farré & Faci, 2006; Katerji & Mastrorilli, 2014; Steduto et al., 1997; Zegada‐Lizarazu, Zatta, & Monti, 2012), indicating the potential for greater capacity for O3 detoxification relative to stomatal O3 uptake. However, other studies have shown that sorghum and maize have similar water‐use‐efficiency when water is non‐limiting (Farré & Faci, 2006; Roby, Fernandez, Heaton, Miguez, & VanLoocke, 2017). Overall, intraspecific variation in O3 tolerance is still unclear at a mechanistic level and will require future studies investigating plant response to O3 at both species and genotypic level.

4.3. Implications for bioenergy feedstock breeding

Sorghum has emerged as a promising bioenergy feedstock. Sorghum is more water‐ and nitrogen‐use efficient than corn and sugarcane, as well as being more drought tolerant and yielding more ethanol per unit area of land than many other biomass crops (Calviño & Messing, 2012; Regassa & Wortmann, 2014; Rooney et al., 2007). In addition, sorghum produces and stores fermentable sugar rather than starch in the stalks which can be metabolized by microbes to produce biofuels (Calviño & Messing, 2012; Regassa & Wortmann, 2014; Rooney et al., 2007). Previous studies have focused primarily on enhancement of sorghum biomass and sugar yield, conversion efficiency through genetic improvement, or agronomic management (Calviño & Messing, 2012; Carpita & McCann, 2008; Mullet et al., 2014; Regassa & Wortmann, 2014; Rooney et al., 2007). However, little effort has been directed towards investigating yield stability, which is the most important factor for continuous ethanol production. Large yield and biomass losses to O3 pollution in maize and sugarcane may lead to a significant decrease in ethanol production with rising O3 concentrations in the future (Grantz & Vu, 2009; McGrath et al., 2015). Although switchgrass is tolerant to O3 and can be a candidate bioenergy feedstock, it produces a lower biomass than sorghum (Li et al., 2019; Rooney et al., 2007; Schmer et al., 2008; Wullschleger et al., 2010). Our results provide evidence that sorghum genotypes exhibit greater O3 tolerance than other C4 bioenergy crops. Considering all the advantages of sorghum as a bioenergy crop, we suggest that sorghum can provide abundant and sustainable energy in the future.

5. CONCLUSIONS

This first study demonstrates that there is a significant variability in plant functional traits across sorghum genotypes and that all genotypes showed a similar response to O3. This study provides strong evidence that bioenergy sorghum genotypes are tolerant to O3 and maintain high photosynthetic capacity in elevated O3 concentrations. Furthermore, this study suggests that sorghum may have greater O3 tolerance than other previously studied C4 crops such as maize and switchgrass. These results have important implications for bioenergy feedstock development in response to climate changes. For instance, sorghum could be planted in regions with high O3 pollution where O3 concentrations cause a significant yield loss in other crops. Overall, the present results suggest that sorghum can produce high and stable biomass yields and provide sustainable energy under future climate scenarios.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Elizabeth A. Ainsworth and Shuai Li designed the study. Shuai Li, Christopher A. Moller and Noah G. Mitchell performed the measurements. Shuai Li performed the statistical analysis. Shuai Li, DoKyoung Lee and Elizabeth A. Ainsworth contributed to the interpretation of results. Shuai Li wrote the first version of the manuscript, which was reviewed and revised by all the authors.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Daily maximum and minimum air temperature (°C) and total precipitation (mm) in the 2018 and 2019 growing seasons.

Figure S2. Leaf photosynthesis and chlorophyll fluorescence at ambient and elevated O3 in sorghum genotypes in the growth chamber.

Figure S3. Summary of A/c i response curves and CO2 supply functions for 4 genotypes of sorghum grown at ambient and elevated O3 in the growth chamber.

Figure S4. Leaf respiration and maximum dark‐adapted quantum yield of photosystem II (F v/F m) measured in sorghum genotypes grown at ambient and elevated O3 in 2018, 2019, and growth chamber.

Figure S5. The relationship between g s c i:c a in sorghum genotypes grown under ambient and elevated O3 measured on three time points in 2018 and 2019.

Figure S6. The relationship between g s and c i:c a in each genotypes of sorghum grown under ambient and elevated O3 in 2018 and 2019.

Figure S7. The relationship between g s and in sorghum genotypes grown under ambient and elevated O3 measured on three time points in 2018 and 2019.

Figure S8. The relationship between g s and in sorghum genotypes grown under ambient and elevated O3 measured on three time points in 2018 and 2019.

Figure S9. Leaf number, total leaf area, average leaf area and plant height measured in sorghum genotypes grown at ambient and elevated O3 in 2018 and 2019.

Figure S10. The relationship between leaf dry mass per area (LMA) and leaf nitrogen content in 4 genotypes of sorghum grown under ambient and elevated O3 in growth chamber measured in 2019.

Table S1. The leaf chamber cuvette conditions for midday gas exchange measurement in 2018 and 2019 at the FACE.

Table S2. Analysis of variance (F, p) of leaf respiration and F v/F m measured sorghum genotypes grown at ambient and elevated O3 at FACE in 2018 and 2019 and in the growth chamber.

Table S3. Estimated slope and intercept values of BWB and MED model for each time point measurement from leaf midday gas exchange data in 2018 and 2019 at FACE.

Table S4. Estimated slope and intercept values of BWB and MED model for each species from leaf midday gas exchange data in 2018 and 2019 at FACE.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jesse McGrath, Aidan McMahon, John Ferguson, Nicole Choquette, Anthony Digrado, Chris Montes, Duncan Martin, Hannah Demler, Renan Umburanas, Seldon Kwafo and Yanquan Zhang for technical and field assistance. We also thank Dr Samuel B. Fernandes and Dr John Ferguson for providing plant seeds and Prof. Andrew Leakey for helpful discussions. We thank two anonymous referees for their helpful comments. This work was funded by the DOE Center for Advanced Bioenergy and Bioproducts Innovation (U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Biological and Environmental Research under Award Number DE‐SC0018420). Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Department of Energy or the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). Mention of trade names or commercial products in this publication is solely for the purpose of providing specific information and does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the USDA. USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer.

Li S, Moller CA, Mitchell NG, Lee DK, Ainsworth EA. Bioenergy sorghum maintains photosynthetic capacity in elevated ozone concentrations. Plant Cell Environ. 2021;44:729–746. 10.1111/pce.13962

Funding information U.S. Department of Energy, Grant/Award Number: DE‐SC0018420

REFERENCES

- Ainsworth, E. A. (2017). Understanding and improving global crop response to ozone pollution. Plant Journal, 90, 886–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth, E. A. , & Long, S. P. (2005). What have we learned from 15 years of free‐air CO2 enrichment (FACE)? A meta‐analytic review of the responses of photosynthesis, canopy properties and plant production to rising CO2 . New Phytologist, 165, 351–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth, E. A. , Rogers, A. , & Leakey, A. D. B. (2008). Targets for crop biotechnology in a future high‐CO2 and high‐O3 world. Plant Physiology, 147, 13–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth, E. A. , Rogers, A. , Nelson, R. , & Long, S. P. (2004). Testing the “source‐sink” hypothesis of down‐regulation of photosynthesis in elevated [CO2] in the field with single gene substitutions in Glycine max . Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, 122, 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth, E. A. , Yendrek, C. R. , Sitch, S. , Collins, W. J. , & Emberson, L. D. (2012). The effects of tropospheric ozone on net primary productivity and implications for climate change. Annual Review of Plant Biology, 63, 637–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, R. (2000). Atmospheric chemistry of VOCs and NOx. Atmospheric Environment, 34, 2063–2101. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, J. T. , Woodrow, I. E. , & Berry, J. A. (1987). A model predicting stomatal conductance and its contribution to the control of photosynthesis under different environmental conditions. In Biggins J. (Ed.), Progress in photosynthesis research (pp. 221–224). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Martinus Nijhoff. [Google Scholar]

- Bollero, G. A. , Bullock, D. G. , & Hollinger, S. E. (1996). Soil temperature and planting date effects on corn yield, leaf area, and plant development. Agronomy Journal, 88, 385–390. [Google Scholar]

- Burkey, K. O. , Booker, F. L. , Ainsworth, E. A. , & Nelson, R. L. (2012). Field assessment of a snap bean ozone bioindicator system under elevated ozone and carbon dioxide in a free air system. Environmental Pollution, 166, 167–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calviño, M. , & Messing, J. (2012). Sweet sorghum as a model system for bioenergy crops. Current Opinion in Biotechnology, 23, 323–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpita, N. C. , & McCann, M. C. (2008). Maize and sorghum: Genetic resources for bioenergy grasses. Trends in Plant Science, 13, 415–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, K.‐L. , Petropavlovskikh, I. , Cooper, O. R. , Schultz, M. G. , & Wang, T. (2017). Regional trend analysis of surface ozone observations from monitoring networks in eastern North America, Europe and East Asia. Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene, 5, 50. [Google Scholar]

- Choquette, N. E. , Ainsworth, E. A. , Bezodis, W. , & Cavanagh, A. P. (2020). Ozone tolerant maize hybrids maintain Rubisco content and activity during long‐term exposure in the field. Plant Cell & Environment, 43, 3033–3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choquette, N. E. , Ogut, F. , Wertin, T. M. , Montes, C. M. , Sorgini, C. A. , Morse, A. M. , … Ainsworth, E. A. (2019). Uncovering hidden genetic variation in photosynthesis of field‐grown maize under ozone pollution. Global Change Biology, 25, 4327–4338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans, J. R. (1989). Photosynthesis and nitrogen relationships in leaves of C3 plants. Oecologia, 78, 9–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farré, I. , & Faci, J. M. (2006). Comparative response of maize (Zea mays L.) and sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L. Moench) to deficit irrigation in a Mediterranean environment. Agricultural Water Management, 83, 135–143. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, J. N. , Fernandes, S. B. , Monier, B. , Miller, N. D. , Allan, D. , Dmitrieva, A. , … Leakey, A. D. B. (2020). Machine learning enabled phenotyping for GWAS and TWAS of WUE traits in 869 field‐grown sorghum accessions. BioRvix. 10.1101/2020.11.02.365213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiscus, E. L. , Booker, F. L. , & Burkey, K. O. (2005). Crop responses to ozone: Uptake, modes of action, carbon assimilation and partitioning. Plant Cell & Environment, 28, 997–1011. [Google Scholar]

- Flowers, M. D. , Fiscus, E. L. , Burkey, K. O. , Booker, F. L. , & Dubois, J.‐J. B. (2007). Photosynthesis, chlorophyll fluorescence, and yield of snap bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) genotypes differing in sensitivity to ozone. Environmental and Experimental Botany, 61, 190–198. [Google Scholar]

- Franks, P. J. , Bonan, G. B. , Berry, J. A. , Lombardozzi, D. L. , Holbrook, N. M. , Herold, N. , & Oleson, K. W. (2018). Comparing optimal and empirical stomatal conductance models for application in earth system models. Global Change Biology, 24, 5708–5723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frei, M. , Tanaka, J. P. , & Wissuwa, M. (2008). Genotypic variation in tolerance to elevated ozone in rice: Dissection of distinct genetic factors linked to tolerance mechanisms. Journal of Experimental Botany, 59, 3741–3752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J. , Zhu, B. , Xiao, H. , Kang, H. , Hou, X. , & Shao, P. (2015). A case study of surface ozone source apportionment during a high concentration episode, under frequent shifting wind conditions over the Yangtze River Delta, China. Science of the Total Environment, 544, 853–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grantz, D. A. , & Vu, H. B. (2009). O3 sensitivity in a potential C4 bioenergy crop: Sugarcane in California. Crop Science, 49, 643–650. [Google Scholar]

- Grantz, D. A. , Vu, H. B. , Tew, T. L. , & Veremis, J. C. (2012). Sensitivity of gas exchange parameters to ozone in diverse C4 sugarcane hybrids. Crop Science, 52, 1270–1280. [Google Scholar]

- Guidi, L. , Degl'Innocentit, E. , Martinelli, F. , & Piras, M. (2009). Ozone effects on carbon metabolism in sensitive and insensitive Phaseolus cultivars. Environmental and Experimental Botany, 66, 117–125. [Google Scholar]

- Hoshika, Y. , Osada, Y. , de Marco, A. , Peñuelas, J. , & Paoletti, E. (2018). Global diurnal and nocturnal parameters of stomatal conductance in woody plants and major crops. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 27, 257–275. [Google Scholar]

- Katerji, N. , & Mastrorilli, M. (2014). Water use efficiency of cultivated crops. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, C. J. , & Walbot, V. (2007). Translational genomics for bioenergy production from fuelstock grasses: Maize as the model species. The Plant Cell, 19, 2091–2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leakey, A. D. B. , Bernacchi, C. J. , Ort, D. R. , & Long, S. P. (2006). Long‐term growth of soybean at elevated [CO2] does not cause acclimation of stomatal conductance under fully open‐air conditions. Plant, Cell & Environment, 29, 1794–1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leakey, A. D. B. , Ferguson, J. N. , Pignon, C. P. , Wu, A. , Jin, Z. , Hammer, G. L. , & Lobell, D. B. (2019). Water use efficiency as a constraint and target for improving the resilience and productivity of C3 and C4 crops. Annual Review of Plant Biology, 70, 781–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leakey, A. D. B. , Uribelarrea, M. , Ainsworth, E. A. , Naidu, S. L. , Rogers, A. , Ort, D. R. , & Long, S. P. (2006). Photosynthesis, productivity, and yield of maize are not affected by open‐air elevation of CO2 concentration in the absence of drought. Plant Physiology, 140, 779–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitao, L. , Bethenod, O. , & Biolley, J.‐P. (2007). The impact of ozone on juvenile maize (Zea mays L.) plant photosynthesis: Effect on vegetative biomass, pigmentation, and carboxylases (PEPc and rubisco). Plant Biology, 9, 478–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitao, L. , Maoret, J.‐J. , & Biolley, J.‐P. (2007). Changes in PEP carboxylase, rubisco and rubisco activase mRAN levels from maize (Zea mays) exposed to a chronic ozone stress. Biological Research, 40, 137–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, S. , Courbet, G. , Ourry, A. , & Ainsworth, E. A. (2019). Elevated ozone concentration reduces photosynthetic carbon gain but does not alter lead structural traits, nutrient composition or biomass in switchgrass. Plants, 8, 85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, S. , Harley, P. C. , & Niinemets, Ü. (2017). Ozone‐induced foliar damage and release of stress volatiles is highly dependent on stomatal openness and priming by low‐level ozone exposure in Phaseolus vulgaris . Plant, Cell & Environment, 40, 1984–2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, S. , Tosens, T. , Harley, P. C. , Jiang, Y. , Kanagendran, A. , Grosberg, M. , … Niinemets, Ü. (2018). Glandular trichomes as a barrier against atmospheric oxidative stress: Relationships with ozone uptake, leaf damage, and emission of LOX products across a diverse set of species. Plant, Cell & Environment, 41, 1263–1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, S. , Zhang, Y.‐J. , Sack, L. , Scoffoni, C. , Ishida, A. , Chen, Y.‐J. , & Cao, K.‐F. (2013). The heterogeneity and spatial patterning of structure and physiology across the leaf surface in giant leaves of Alocasia macrorrhiza . PLoS One, 8, e66016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.‐S. , Medlyn, B. E. , Duursma, R. A. , Prentice, I. C. , Wang, H. , Baig, S. , … Wingate, L. (2015). Optimal stomatal behaviour around the world. Nature Climate Change, 5, 459–464. [Google Scholar]

- Lombardozzi, D. , Sparks, J. P. , Bonan, G. , & Levis, S. (2012). Ozone exposure causes a decoupling of conductance and photosynthesis: Implications for the Ball–Berry stomatal conductance model. Oecologia, 169, 651–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long, S. P. , Ainsworth, E. A. , Rogers, A. , & Ort, D. R. (2004). Rising atmospheric carbon dioxide: Plants FACE the future. Annual Review of Plant Biology, 55, 591–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long, S. P. , & Bernacchi, C. J. (2003). Gas exchange measurements, what can they tell us about the underlying limitations to photosynthesis? Procedures and sources of error. Journal of Experimental Botany, 54, 2393–2401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long, S. P. , & Naidu, S. L. (2002). Effects of oxidants at the biochemical, cell and physiological levels. In Bell J. M. B. & Treshow M. J. (Eds.), Air pollution and plants (pp. 69–88). London, England: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Markelz, R. J. C. , Strellner, R. S. , & Leakey, A. D. B. (2011). Impairment of C4 photosynthesis by drought is exacerbated by limiting nitrogen and ameliorated by elevated [CO2] in maize. Journal of Experimental Botany, 62, 3235–3246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massman, W. J. (2004). Toward an ozone standard to protect vegetation based on effective dose: A review of deposition resistances and a possible metric. Atmospheric Environment, 38, 2323–2337. [Google Scholar]

- Masutomi, Y. , Kinose, Y. , Takimoto, T. , Yonekura, T. , Oue, H. , & Kobayashi, K. (2019). Ozone changes the linear relationship between photosynthesis and stomatal conductance and decreases water use efficiency in rice. Science of the Total Environment, 655, 1009–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maughan, M. , Voigt, T. , Parrish, A. , Bollero, G. , Rooney, W. , & Lee, D. K. (2012). Forage and energy sorghum responses to nitrogen fertilization in central and southern Illinois. Agronomy Journal, 104, 1032–1040. [Google Scholar]

- McGrath, J. M. , Betzelberger, A. M. , Wang, S. , Shook, E. , Zhu, X.‐G. , Long, S. P. , & Ainsworth, E. A. (2015). An analysis of ozone damage to historical maize and soybean yields in the United States. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112, 14390–14295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medlyn, B. E. , Duursma, R. A. , Eamus, D. , Ellsworth, D. S. , Prentice, I. C. , Barton, C. V. M. , … Wingate, L. (2011). Reconciling the optimal and empirical approaches to modelling stomatal conductance. Global Change Biology, 17, 2134–2144. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, G. , Sharps, K. , Simpson, D. , Pleijel, H. , Broberg, M. , Uddling, J. , … Dingenen, R. V. (2018a). Ozone pollution will compromise efforts to increase global wheat production. Global Change Biology, 24, 3560–3574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills, G. , Sharps, K. , Simpson, D. , Pleijel, H. , Frei, M. , Burkey, K. , … Agrawal, M. (2018b). Closing the global ozone yield gas: Quantification and cobenefits for multistress tolerance. Global Change Biology, 24, 4869–4893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miner, G. L. , & Bauerle, W. L. (2017). Seasonal variability of the parameters of the Ball–Berry model of stomatal conductance in maize (Zea mays L.) and sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) under well‐watered and water‐stresses conditions. Plant, Cell & Environment, 40, 1874–1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monks, P. S. , Archibald, A. T. , Colette, A. , Cooper, O. , Coyle, M. , Derwent, R. , … Williams, M. L. (2015). Tropospheric ozone and its precursors from the urban to the global scale from air quality to short‐lived climate forcer. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 15, 8889–8973. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, P. B. , Bernacchi, C. J. , Ort, D. R. , & Long, S. P. (2004). An in vivo analysis of the effect of season‐long open‐air elevation of ozone to anticipated 2050 levels on photosynthesis in soybean. Plant Physiology, 135, 2348–2357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]