Abstract

Comprehensive sexual health education increases sexual health knowledge and decreases adverse health outcomes and high-risk behaviors in heterosexual youth but lacks information relevant to gender and sexual minority youth. Universal access to comprehensive sexual health education that includes information relevant to gender and sexual minority individuals is lacking in the United States, leading to poor health outcomes for gender and sexual minority youth. The purpose of this review was to examine sexual health education programs in schools in the United States for the inclusion of information on gender identity and sexual orientation. The review provides information on current programs offered in schools and suggestions to make them more inclusive to gender and sexual minority youth.

Keywords: LGBTQ+, sex education, sexual health, gender minority, sexual minority

Is Sex Education for Everyone?: A Review

Gender and sexual minority youth (GSMY), youth who do not identify as heterosexual or their gender identity are non-binary, have increased sexual risk behaviors and adverse health outcomes compared to their heterosexual and cisgender peers (Kann et al., 2016; Rasberry et al., 2017, 2018). According to the 2017 YRBS youth that identified as a sexual minority (lesbian, gay, bisexual, or another non-heterosexual identity or reporting same-sex attraction or sexual partners) reported increased sexual partners, earlier sexual debut, the use of alcohol or drugs before sex, decreased condom and contraceptive use than their heterosexual peers (Rasberry et al., 2018). Comprehensive sexual health education increase sexual health knowledge and decreases adverse health outcomes, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), HIV, and pregnancy and high-risk behaviors in heterosexual youth, age of sexual initiation, the number of sex partners, sex without protection, sex while under the influence of drugs and alcohol (Bridges & Alford, 2010; Mustanski, 2011; Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States (SIECUS)., 2004; Steinke et al., 2017). Research conducted with heterosexual adolescents shows comprehensive sexual health education, medically accurate material that includes information on STIs, HIV, pregnancy, condoms, contraceptives as well as abstinence and sexual decision making, increases sexual health knowledge and decreases adverse health outcomes, STIs, HIV, and pregnancy and high-risk behaviors (Bridges & Alford, 2010; Mustanski, 2011; Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States (SIECUS)., 2004; Steinke et al., 2017). Most GSMY report receiving some form of sexual health education in school ranging from comprehensive to abstinence-only, however GSMY-inclusive sexual health education, education that includes information on all genders and sexual orientations, is out of reach for a majority of youth in the United States (Charest et al., 2016; Human Rights Campaign, 2015; Kosciw et al., 2018; Steinke et al., 2017). Not having access to GSMY-inclusive sex education, GSMY lack the information they need to understand their sexuality and gender concerns and to make informed sexual decisions (Charest et al., 2016; Steinke et al., 2017).

Most teens, 70%, report receiving some form of sexual health education in school; while the content varies widely, from abstinence-only to comprehensive, it is primarily penile-vaginal in nature (Human Rights Campaign, 2015; Lindberg et al., 2016). Universal access to comprehensive and GSMY-inclusive sexual health education is lacking in the United States and can lead to poor health outcomes for GSMY (Human Rights Campaign, 2015). Currently, only 27 states mandate sexual health and HIV education (Guttmacher Institute, 2020). Seventeen states require discussion of sexual orientation, with only 10 requiring information to be inclusive of gender and sexuality, and seven mandating only negative information be provided on homosexuality and positive information solely be provided on heterosexuality (Guttmacher Institute, 2020). These laws intended to prohibit the promotion of homosexuality, deny SGMY the sexual health information they need and serve to further stigmatize them for their gender identity and sexual orientation (Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network (GLSEN), 2018).

Significance of the Topic

Despite the effectiveness of comprehensive sexual health education in increasing sexual health outcomes in heterosexual youth, little research has been done on its effects on GSMY (Human Rights Campaign, 2015; Kosciw et al., 2018; Steinke et al., 2017). The sex education offered in schools primarily describes penile-vaginal intercourse and does not include information on oral, anal, or manual intercourse or ways to practice safe sex with these types of sexual activity. Less than 7% of GSMY in the United States report receiving sexual health education that was inclusive of both gender and sexual minorities (Charest et al., 2016; Human Rights Campaign, 2015; Kosciw et al., 2018; Steinke et al., 2017). Many GSMY look to the internet or pornography for information on sex, leading to misinformation or an unrealistic expectation of intercourse and relationships (Arbeit et al., 2016; Charest et al., 2016; Haley et al., 2019; Hobaica et al., 2019; Hobaica & Kwon, 2017; Roberts et al., 2019).

Teens and young adults account for 21% of all new HIV cases in the United States, with 81% of newly diagnosed cases attributed to young men who have sex with men (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2019). Lindley & Walsemann, (2015) conducted a study of teens in New York and found that GSMY youth had between a two to seven times higher chance of being involved in a pregnancy than their heterosexual peers. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2018), young men who have sex with men have a higher incidence of gonorrhea, chlamydia, and syphilis compared to women and men who have sex with women only. The 2017 YRBS report revealed that GSMY reported significantly higher incidences of forced sex, dating violence, suicidal thoughts, attempted suicide, bullying, alcohol and drug use, earlier initiation into sex, more sexual partners, and were also less likely to use condoms during sexual intercourse than their heterosexual peers (Kann et al., 2018; Rasberry et al., 2018). To improve sexual health outcomes in GSMY, they need to receive sexual health education that is comprehensive and inclusive to all genders and sexual orientations at an early age.

The purpose of this review was to examine the sexual health education programs in public and private schools in the United States for the inclusion of information on gender identity and sexual orientation. Further, this review provides an understanding of the sexual health education needs of GSMY, how it is reflected in the programs offered to young adults, and what changes could be made. A review of studies published between 2010 and 2020 was conducted to evaluate the inclusion of gender and sexual minority information in sexual health education offered in schools.

Literature Search

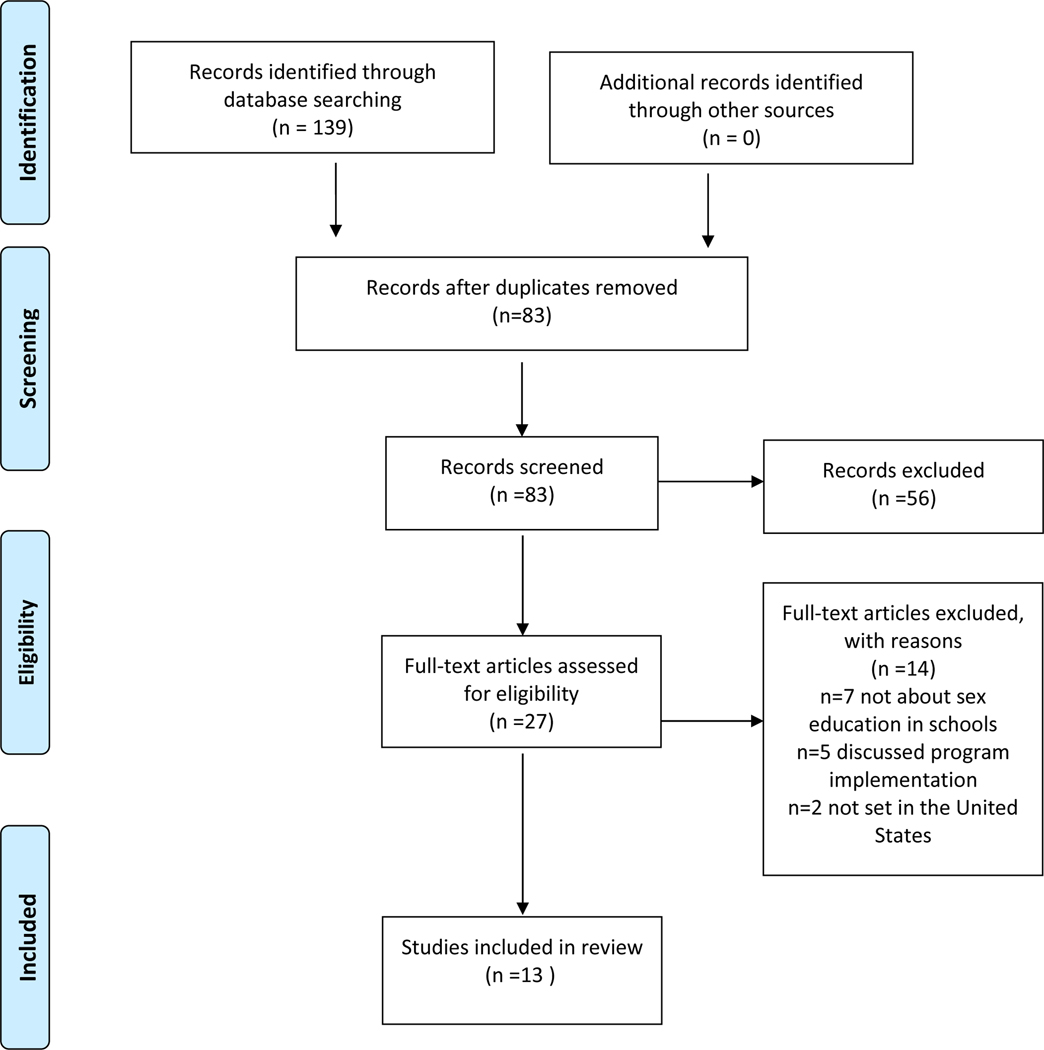

The review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systemic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al., 2009). The search was conducted using three online databases: CINAHL, PubMed, and Scopus. The search strategy for CINAHL was as follows: limits were set to include research articles published in English in peer-reviewed academic journals, age restriction set to “all child” major heading “sex education” and “sexual health”. The search date was set from January 2010 to March 2020. The reason for the 2010 start date was to get the latest information on sexual health education programs. The combinations of the search terms used were “sex education” and “sexual minority”; “sexual health education” and “sexual minority”; “inclusive” and “sex education” and “school”; “LGBT” and “sex education”. The same searches were conducted in each of the other databases. The process is illustrated in Figure 1. The initial searches yielded a total of 83 articles after duplicates were removed; 56 articles could be excluded after reading the title or abstract due to location or not discussing sex education in the primary or high school setting, 27 articles were viewed in full text. After reading the full-text articles, 14 articles were excluded for the following reasons: seven did not discuss sex education programs in school, five discussed program implementations, and two were not set in the United States. A total of 13 peer reviewed articles were included in this review (Table 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram showing search and screening process, and selection of studies for inclusion in the review.

Table 1.

Review of Studies Related to Inclusive Sexual Health Education

| Author | Purpose/Topic | Type of Study/Sample | Key Findings/recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arbeit et al. 2016 Arbeit, M. R., Fisher, C. B., Macapagal, K., & Mustanski, B. (2016). |

To analyze bisexual female perspectives of their experiences accessing sexual health information and services provided by schools and health providers. |

Mixed methods; n= 40 cisgender sexual minority females divided into 6 focus groups | Practitioners should include nonjudgmental questions regarding bisexuality into contraceptive and sexual health practices involving young females. Schools need to provide inclusive sex education. |

| Bodnar, K., & Tornello, S. L. (2019) | To explore how exposure and timing of sex education were associated with sexual health outcomes. | Quantitative; 2002 to 2013 collections of the National Survey of Family Growth n=5, 141 young women | Exposure to sex education resulted in poorer outcomes for sexual minority women. Sex education should be presented earlier and be inclusive. |

| Gowen, L. K., & Winges-Yanez, N. (2014). | To investigate the sexual health education experiences of LGBTQ youth and gather suggestions for improving the inclusiveness of sexuality education. curricula. |

Qualitative; n=5 semi-structured focus groups containing 30 LGBTQ adolescents | LGBTQ youth see current sex education as exclusive, not inclusive. Schools and policymakers need to make sure inclusive education is available to all youth. |

| Haley, S. G., Tordoff, D. M., Kantor, A. Z., Crouch, J. M., & Ahrens, K. R. (2019) | To use information from transgender and nonbinary youth and their parents to understand deficits in sexual health education and give recommendations for a comprehensive inclusive curriculum. | Qualitative; n=21 (n=11 transgender/nonbinary youth, n=5 parents of transgender/nonbinary youth; n=5 healthcare providers) | Most information taught in schools was irrelevant to transgender/nonbinary youth. Education needs to be inclusive and gender-affirming. |

| Hall, K. S., McDermott Sales, J., Komro, K. A., & Santelli, J. (2016) | To analyze the content of school-based sex education policies in the United States. | Commentary | There were no consistent policies regarding sex education in schools. Abstinence-only education was the prominent form of education taught. Few states mandated inclusive teaching and some mandated only negative information on homosexuality be taught. Sex education should be evidence-based. |

| Hobaica, S., & Kwon, P. (2017). | To explore sex-education policies and curriculum to determine if they could be adapted for sexual minority students. | Qualitative; n=12 sexual minority individuals who received sex education in school | Sex education was heteronormative and did not address the needs of sexual minority individuals potentially causing poorer physical and mental health outcomes. Education should be inclusive and be taught earlier. |

| Hobaica, S., Schofield, K., & Kwon, P. (2019). | To explore the experiences of trans students in sex education. | Qualitative; n=11 transgender individuals who received sex education in school | Most information taught in schools was cisgender and irrelevant to transgender/nonbinary youth. Education needs to be offered earlier and be gender-affirming to help prevent risky sexual behavior and gender dysphoria. |

| McCarty-Caplan, D. (2015). | To explore policy limitations and demonstrate how comprehensive sex education perpetuates the heteronormative nature of sex education in a way that continues to marginalize and harm LGB individuals. | Commentary | Comprehensive sex education programs do not provide substantial support for lesbian, bisexual, and gay individuals. |

| Pingel, E. S., Thomas, L., Harmell, C., & Bauermeister, J. (2013). | To investigate the sexual health education experiences of sexual minority young men and gather suggestions for improving the inclusiveness of sexuality education. curricula. |

Qualitative; n=30 young gay, bisexual and questioning men who had experience with school-based sex education. | Most information on sexual minorities was excluded from the sex-education taught in school. Many youths looked to the internet for sexual health information to fill the gap. Sexual health education should be inclusive. |

| Proulx, C. N., Coulter, R. W. S., Egan, J. E., Matthews, D. D., & Mair, C. (2019) | To explore whether LGBTQ inclusive sex education is associated with adverse mental health and school-based victimization. | Quantitative; 2015 Youth Risk Behavior Survey and 2014 School Health Profiles n=47,730 sexual minority youth. | Inclusive sex education had a protective effect against suicidal thoughts and plans. LGBTQ youth had lower odds of being bullied as the percentage of schools in the state offered inclusive education. States should offer inclusive education. |

| Rasberry, C. N., Condron, D. S., Lesesne, C. A., Adkins, S. H., Sheremenko, G., & Kroupa, E. (2017). | The purpose of this study was to help inform the development of school-centered strategies for connecting sexual minority young men with HIV and STD prevention services. | Mixed methods; n=415 web-based questionnaires and n=32 interviews of Black and Latino young sexual minority men. | School nurses were the people youth most talked to about STIs, HIV, or condom use but they would not talk to them about personal attraction. Many youths felt school staff lacked knowledge on LGBT issues. School nurses and staff need additional training on LGBT issues. |

| Roberts, C., Shiman, L. J., Dowling, E. A., Tantay, L., Masdea, J., Pierre, J., Lomax, D., & Bedell, J. (2019) | To conceptualize the barriers LGBTQ+ students of color face in learning about sexual health education in school. | Qualitative; n=27 LGBTQ students of color between the ages of 15–19 | Students reported receiving heteronormative sex education that was inadequate to their needs and left them feeling unrepresented, unsupported, stigmatized, and, bullied. Students filled these gaps by seeking information from external sources. Schools need to provide inclusive information. |

| Steinke, J., Root-Bowman, M., Estabrook, S., Levine, D. S., & Kantor, L. M. (2017). | To better understand what young people want from digital sexual health interventions. | Qualitative; n=92 gender and sexual minority youth | Education taught in schools was inaccurate and insufficient. Most participants looked for information online. Content and delivery of online sexual health information should be inclusive. |

Current Education Offered

Heteronormative Information

A majority of the research reported the content of the sexual health education offered in schools was heteronormative, the belief that heterosexuality and binary gender are the norms, and the intercourse discussed was penile-vaginal intercourse (Arbeit et al., 2016; Bodnar & Tornello, 2019; Gowen & Winges-Yanez, 2014; Haley et al., 2019; K. S. Hall et al., 2016; Hobaica et al., 2019; Hobaica & Kwon, 2017; Rasberry et al., 2017; Steinke et al., 2017). The lessons primarily consisted of information about puberty, the dangers of sex, penile-vaginal intercourse, STIs, and pregnancy; information the GSMY in the studies reported as irrelevant to them (Gowen & Winges-Yanez, 2014; Haley et al., 2019; Hobaica et al., 2019; Hobaica & Kwon, 2017; Pingel et al., 2013; Roberts et al., 2019). Of the 13 studies, eight mentioned students being taught about external condoms, one mentioned internal condoms, 1 discussed students being shown a condom demonstration and none reported information being given on dental dams or finger condoms. (Arbeit et al., 2016; Gowen & Winges-Yanez, 2014; Haley et al., 2019; K. S. Hall et al., 2016; Hobaica et al., 2019; Hobaica & Kwon, 2017; Rasberry et al., 2017; Roberts et al., 2019). In seven of the studies, participants reported their questions regarding gender identity or sexual orientation went unanswered in class. This was due to the teacher ignoring the question, the teacher lacking the information to answer, or the teacher not being allowed to answer due to school and state policy (Arbeit et al., 2016; Gowen & Winges-Yanez, 2014; Haley et al., 2019; K. S. Hall et al., 2016; Hobaica et al., 2019; Hobaica & Kwon, 2017; Mahdi et al., 2014; Pingel et al., 2013; Steinke et al., 2017).

Supplying only heteronormative education contributed to poorer mental outcomes for GSMY. Non-heterosexual, non-binary, and gender-nonconforming individuals and their behavior were often pathologized in the education presented, leading to internalized homophobia, increased depression, increased anxiety, and self-loathing in GSMY (Arbeit et al., 2016; Bodnar & Tornello, 2019; Gowen & Winges-Yanez, 2014; Hobaica et al., 2019; Hobaica & Kwon, 2017; Pingel et al., 2013; Steinke et al., 2017). The exclusion of information about gender and sexual minorities made GSMY feel confused about how they were feeling, made them feel something was wrong with them and made them feel like they did not exist (Gowen & Winges-Yanez, 2014; Haley et al., 2019; Hobaica et al., 2019; Hobaica & Kwon, 2017; Rasberry et al., 2017; Roberts et al., 2019). Lack of GSMY-inclusive information also led to an increase in bullying of GSMY in schools from both students and teachers (Arbeit et al., 2016; Gowen & Winges-Yanez, 2014; W. J. Hall et al., 2019; McCarty-Caplan, 2015; Roberts et al., 2019). Numerous studies described a decrease in bullying of GSMY in schools with GSMY-inclusive education, potentially due to a normalizing non-heterosexual, non-binary, and gender-nonconforming individuals, (Gowen & Winges-Yanez, 2014; Haley et al., 2019; Hobaica et al., 2019; Hobaica & Kwon, 2017; Proulx et al., 2019; Roberts et al., 2019).

Incomplete and Inaccurate Information

The negative impact an incomplete sex education had on GSMY health was a common theme in the literature (Bodnar & Tornello, 2019; Gowen & Winges-Yanez, 2014; Haley et al., 2019; Hobaica et al., 2019; Hobaica & Kwon, 2017; Pingel et al., 2013). Many of the lessons taught in school only covered the “mechanics” of penile-vaginal intercourse and the problems that can occur from that action, with few reporting receiving lessons about other types of sex (anal, oral, manual, masturbation), healthy relationships, consent, or the enjoyment of sex (Gowen & Winges-Yanez, 2014; Haley et al., 2019; Hobaica et al., 2019; Hobaica & Kwon, 2017; Roberts et al., 2019). No studies reported information being taught on transgender identity, non-binary identity, or use of proper pronouns (Haley et al., 2019; Hobaica et al., 2019; Roberts et al., 2019).

Several authors discussed inaccurate information being offered to students in schools (Haley et al., 2019; K. S. Hall et al., 2016; Hobaica et al., 2019; Hobaica & Kwon, 2017). Hobaica and Kwon (2017) reported in 2016 only 20 states required sexual health information provided to students in school to be medically accurate. Inaccurate information given to youth included inflated failure rates of condoms and birth control, inaccurate information on the transmission of STIs, and inaccurate representation of gender and sexual minority individuals (Haley et al., 2019; Hobaica et al., 2019; Hobaica & Kwon, 2017; Roberts et al., 2019; Steinke et al., 2017). Lack of information and inaccurate information contributed to GSMY making uninformed decisions about sex, leading to increased sexual experiences, increased number of partners, non-consensual sexual experiences, unprotected sex, sex while intoxicated, STIs, and pregnancy (Bodnar & Tornello, 2019; Gowen & Winges-Yanez, 2014; Hobaica et al., 2019; Hobaica & Kwon, 2017; Rasberry et al., 2017).

Timing of Information

The timing of education being offered to students occurred in middle school and high school (Bodnar & Tornello, 2019; Haley et al., 2019; Hobaica et al., 2019; Hobaica & Kwon, 2017). For some GSMY this information came too late to be helpful. Sexual minority youth report earlier initiation into sex and many received sex education after they had already become sexually active leading to early risky sexual behaviors and pregnancy (Arbeit et al., 2016; Bodnar & Tornello, 2019; Haley et al., 2019; Hobaica & Kwon, 2017). Gender minority and non-binary individuals recommended that information about gender and puberty start as early as 1st and 2nd grade to help with the problems associated with gender dysphoria.

Recommendations

There were many recommendations included in the literature on how to make sexual health education more inclusive and appropriate for GSMY. To be relevant to all students sexual health education must be inclusive of all genders and sexual orientations and it is important that affirming gender and sexuality inclusive language and pronouns are used when describing different subgroups of GSMY (Arbeit et al., 2016; Gowen & Winges-Yanez, 2014; Haley et al., 2019; Hobaica et al., 2019; Hobaica & Kwon, 2017; Pingel et al., 2013; Rasberry et al., 2017; Roberts et al., 2019; Steinke et al., 2017). It is important that the education provided be medically accurate and cover different types of sex acts, not just penile-vaginal intercourse, include information on the type of protection needed to have safe sex based on the sexual act being performed, and local resources where it can be obtained (Arbeit et al., 2016; Bodnar & Tornello, 2019; Hobaica et al., 2019; Hobaica & Kwon, 2017; Pingel et al., 2013; Roberts et al., 2019). Education should also include information on medical and non-medical gender-affirming interventions, information on relationships, consent, and reputable resources for healthcare and sexual health information (Gowen & Winges-Yanez, 2014; Haley et al., 2019; Hobaica et al., 2019; Hobaica & Kwon, 2017; Pingel et al., 2013; Roberts et al., 2019). There was a reported need for inclusion of historical gender and sexual minority individuals in the core curriculum. This would allow GSMY to have role models and would allow others could see gender and sexual minority individuals in a different light (Hobaica et al., 2019; Hobaica & Kwon, 2017; Pingel et al., 2013).

Discussion

This paper reviewed how sexual health education has been presented in schools over the past ten years. All studies reported participants receiving some form of sexual health education in school. However, the education presented was almost exclusively heteronormative and exclusive to GSMY needs leaving them feeling left out and lacking the information they needed to better understand themselves and make informed sexual health decisions (Bodnar & Tornello, 2019; Gowen & Winges-Yanez, 2014; Hobaica et al., 2019; Hobaica & Kwon, 2017; Rasberry et al., 2017).

School administrators need to be aware of the specific sexual health needs of GSMY and tailor education to meet the needs of all the students, not only cisgender, heterosexual students. Providing comprehensive GSMY-inclusive education improves the physical and mental health outcomes of all youth and decreases bullying of GSMY in school (Hobaica et al., 2019, 2019; Human Rights Campaign, 2015; Proulx et al., 2019; Roberts et al., 2019). GSMY-inclusive education has been shown to decrease negative mental health outcomes and bullying by normalize the LGBT experience (Gowen & Winges-Yanez, 2014; Proulx et al., 2019; Roberts et al., 2019) and potentially decrease pregnancy and STI rates, and increase the use of condoms and the age of sexual debut (Haley et al., 2019; Hobaica et al., 2019; Pingel et al., 2013). If school administrators are unable to provide GSMY-inclusive sex education due to policy at the local or state level, it is important to offer vetted outside resources for students and to work with politicians to change these stigmatizing laws (W. J. Hall et al., 2019; Human Rights Campaign, 2015; Steinke et al., 2017).

The needs of students should take precedent when creating sexual health education programs. Administration, faculty, and staff should be educated on the needs of GSMY. Curricula presented to students in schools must be evidence-based and facilitated by trained LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender) affirming educators (Gowen & Winges-Yanez, 2014; Hobaica et al., 2019; Hobaica & Kwon, 2017; Human Rights Campaign, 2015; Steinke et al., 2017).

Limitations

This review is not without limitations. The search databases used were health and medical and not educational in nature due to the author examining the physical and mental health aspects of sex education on GSMY. The number of articles included was small and more may have been included had educational databases been used. MeSH terms were not used in the search as they had a limiting effect on the results. Lastly, there is very little research on the long-term benefits of GSMY-inclusive sex education in the United States. One of the reasons for this is there is no consistent sex education offered to students, with instructional content often being based on state, local, mandate or teacher preference.

Conclusion

This review indicated that schools are still presenting sexual health education exclusive of gender and sexual minority needs. Sex education is a public health necessity, allowing individuals to make informed decisions concerning their sexual health and wellbeing, and GSMY are being overlooked, leading to poorer mental and physical health outcomes (Gowen & Winges-Yanez, 2014; Haley et al., 2019; Hobaica et al., 2019; Hobaica & Kwon, 2017; Rasberry et al., 2017; Roberts et al., 2019). Sex education in schools needs to be medically accurate, affirming, and reflect all genders and sexual orientations to help reduce health disparities and increase the quality of life for GSMY. Future research should focus on strategies to implement comprehensive and GSMY-inclusive sex education in schools to evaluate its impact on the health and wellness of all youth.

References

- Arbeit MR, Fisher CB, Macapagal K, & Mustanski B. (2016). Bisexual invisibility and the sexual health needs of adolescent girls. LGBT Health, 3(5), 342–349. 10.1089/lgbt.2016.0035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodnar K, & Tornello SL (2019). Does sex education help everyone?: Sex education exposure and timing as predictors of sexual health among lesbian, bisexual, and heterosexual young women. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 29(1), 8–26. 10.1080/10474412.2018.1482219 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges E, & Alford S. (2010). Comprehensive sex education and academic success: Effective programs foster student achievement. In Advocates for Youth. Advocates for Youth. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018). Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2017 (p. 168). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). HIV and youth. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/group/age/youth/cdc-hiv-youth.pdf

- Charest M, Kleinplatz PJ, & Lund JI (2016). Sexual health information disparities between heterosexual and LGBTQ+ young adults: Implications for sexual health. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 25(2), 74–85. http://proxy.mul.missouri.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,cookie,url,uid&db=aph&AN=117494153&site=ehost-live&scope=site [Google Scholar]

- Gay Lesbian and Straight Education Network (GLSEN). (2018). Laws prohibiting “Promotion of Homosexuality” in schools: Impacts and implications (Research Brief). GLSEN. https://www.glsen.org/activity/no-promo-homo-laws [Google Scholar]

- Gowen LK, & Winges-Yanez N. (2014). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning youths’ perspectives of inclusive school-based sexuality education. Journal of Sex Research, 51(7), 788–800. 10.1080/00224499.2013.806648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttmacher Institute. (2020). Sex and HIV education. Guttmacher Institute. https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/sex-and-hiv-education

- Haley SG, Tordoff DM, Kantor AZ, Crouch JM, & Ahrens KR (2019). Sex education for transgender and non-binary youth: Previous experiences and recommended content. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 16(11), 1834–1848. Scopus. 10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall KS, McDermott Sales J, Komro KA, & Santelli J. (2016). The state of sex education in the United States. Journal of Adolescent Health, 58(6), 595–597. Scopus. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.03.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall WJ, Jones BLH, Witkemper KD, Collins TL, & Rodgers GK (2019). State policy on school-based sex education: A content analysis focused on sexual behaviors, relationships, and identities. American Journal of Health Behavior, 43(3), 506–519. 10.5993/AJHB.43.3.6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobaica S, & Kwon P. (2017). “This is how you hetero:” Sexual minorities in heteronormative sex education. American Journal of Sexuality Education, 12(4), 423–450. Scopus. 10.1080/15546128.2017.1399491 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hobaica S, Schofield K, & Kwon P. (2019). “Here’s your anatomy…Good luck”: Transgender individuals in cisnormative sex education. American Journal of Sexuality Education. Scopus. 10.1080/15546128.2019.1585308 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Human Rights Campaign. (2015). A call to action: LGBTQ youth need inclusive sex education. Human Rights Campaign. https://assets2.hrc.org/files/assets/resources/HRC-SexHealthBrief-2015.pdf?_ga=2.60118445.1074231455.1540091154-1852658718.154009115 [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Queen B, Lowry R, Chyen D, Whittle L, Thornton J, Lim C, Bradford D, Yamakawa Y, Leon M, Brener N, & Ethier KA (2018). Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2017. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67(8), 1–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, Olson EO, McManus T, Harris WA, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Queen B, Lowry R, Chyen D, Whittle L, Thornton J, Lim C, Yamakawa Y, Brener N, & Zaza S. (2016). Sexual identity, sex of sexual contacts, and health-related behaviors among students in grades 9–12—United States and selected sites, 2015. MMWR. Surveillance Summaries, 65. 10.15585/mmwr.ss6509a1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw JG, Greytak EA, Zongrone AD, Clark CM, & Truong NL (2018). The 2017 National School Climate Survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer youth in our nation’s schools. Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network (GLSEN). [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg LD, Maddow-Zimet I, & Boonstra H. (2016). Changes in adolescents’ receipt of sex education, 2006–2013. Journal of Adolescent Health, 58(6), 621–627. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindley LL, & Walsemann KM (2015). Sexual orientation and risk of pregnancy among New York City high-school students. American Journal of Public Health, 105(7), 1379–1386. 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahdi I, Jevertson J, Schrader R, Nelson A, & Ramos MM (2014). Survey of New Mexico school health professionals regarding preparedness to support sexual minority students. Journal of School Health, 84(1), 18–24. Scopus. 10.1111/josh.12116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty-Caplan D. (2015). Sex education and support of LGB families: A family impact analysis of the personal responsibility education program. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 12(3), 213–223. Scopus. 10.1007/s13178-015-0189-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, & Altman DG (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ, 339. 10.1136/bmj.b2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B. (2011). Ethical and regulatory issues with conducting sexuality research with LGBT adolescents: A call to action for a scientifically informed approach. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40(4), 673. 10.1007/s10508-011-9745-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pingel ES, Thomas L, Harmell C, & Bauermeister J. (2013). Creating comprehensive, youth centered, culturally appropriate sex education: What do young gay, bisexual and questioning men want? Sexuality Research & Social Policy, 10(4). 10.1007/s13178-013-0134-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proulx CN, Coulter RWS, Egan JE, Matthews DD, & Mair C. (2019). Associations of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning–inclusive sex education with mental health outcomes and school-based victimization in U.S. High school students. Journal of Adolescent Health. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.11.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasberry CN, Condron DS, Lesesne CA, Adkins SH, Sheremenko G, & Kroupa E. (2017). Associations between sexual risk-related behaviors and school-based education on HIV and condom use for adolescent sexual minority males and their non-sexual-minority peers. LGBT Health, 5(1), 69–77. 10.1089/lgbt.2017.0111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasberry CN, Lowry R, Johns M, Robin L, Dunville R, Pampati S, Dittus PJ, & Balaji A. (2018). Sexual risk behavior differences among sexual minority high school students—United States, 2015 and 2017. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6736a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts C, Shiman LJ, Dowling EA, Tantay L, Masdea J, Pierre J, Lomax D, & Bedell J. (2019). LGBTQ+ students of colour and their experiences and needs in sexual health education: ‘You belong here just as everybody else.’ Sex Education. Scopus. 10.1080/14681811.2019.1648248 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States. (2004). Guidelines for comprehensive sexuality education. Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States. https://siecus.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Guidelines-CSE.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Steinke J, Root-Bowman M, Estabrook S, Levine DS, & Kantor LM (2017). Meeting the needs of sexual and gender minority youth: Formative research on potential digital health interventions. Journal of Adolescent Health, 60(5), 541–548. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.11.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]