Structured Abstract

Purpose of review:

Each year in the United States there are over 2.5 million visits to emergency departments for traumatic brain injury, 300,000 hospitalizations, and 50,000 deaths. TBI initiates a complex cascade of events which can lead to significant secondary brain damage. Great interest exists in directly measuring cerebral oxygen delivery and demand after TBI to prevent this secondary injury. Several invasive, catheter-based devices are now available which directly monitor the partial pressure of oxygen in brain tissue (PbtO2), yet significant equipoise exists regarding their clinical use in severe TBI.

Recent findings:

There are currently three ongoing multicenter randomized controlled trials studying the use of PbtO2 monitoring in severe TBI: BOOST-3, OXY-TC, and BONANZA. All three have similar inclusion/exclusion criteria, treatment protocols, and outcome measures. Despite mixed existing evidence, use of PbtO2 is already making its way into new TBI guidelines such as the recent Seattle International Brain Injury Consensus Conference. Analysis of high-fidelity data from multimodal monitoring, however, suggests that PbtO2 may only be one piece of the puzzle in severe TBI.

Summary:

While current evidence regarding use of PbtO2 remains mixed, three ongoing clinical trials are expected to definitively answer the question of what role PbtO2 monitoring plays in severe TBI.

Keywords: Traumatic brain injury, brain tissue oxygenation, PbtO2

Introduction

Annually in the United States there are over 2.5 million visits to emergency departments for traumatic brain injury (TBI), of which nearly 300,000 result in hospitalization and over 50,000 in death (1). Mortality following severe TBI, defined as an initial Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) less than 9, is estimated to be 30-50%, with 80% of survivors reporting chronic sequalae from their injury (2–5). The lifetime economic cost of TBI was estimated to be approximately $76.5 billion in 2010 (1). Beyond primary injury, TBI also initiates a complex cascade of events that can lead to significant secondary injury in the hours to days following insult, posing significant challenges to patient care.

Significant research is ongoing regarding the best methods for detection, prevention, and treatment of secondary injury in severe TBI. Historically, much of this work has focused on intracranial hypertension, a known independent risk factor for morbidity and mortality in severe TBI. This association is related to its negative effect on cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP), as hypoperfusion and the resultant brain tissue hypoxia contribute to secondary injury. Because the brain has limited oxygen and glucose reserves, it depends on continuous adequate blood flow to meet its metabolic demand. Multiple clinical studies, however, have demonstrated that episodes of brain ischemia and hypoxia are common after TBI despite normalization of intracranial pressure (ICP) (6–9) and that brain hypoxia is associated with poor short-term outcome in severe TBI independent of elevated ICP, low CPP, and injury severity (10–12). These findings point to a more complex interplay between cerebral blood flow (CBF), cerebral metabolism, hypoxia, and secondary injury. Both polytrauma and acute brain injury can disrupt normal oxygen delivery and increase metabolic demand, either directly or by effect of arterial hyper/hypotension, low cardiac output, hypocapnia, systemic hypoxia, anemia, or hyperthermia. Because of this, great interest exists in directly measuring cerebral oxygen delivery and demand after TBI in an effort to correct any mismatch. Multiple different techniques have been employed including positron emission tomography, magnetic resonance spectroscopy, jugular venous oximetry, near-infrared spectroscopy, and cerebral microdialysis. These all have significant limitations and thus none have emerged as standard-of-care in management of severe TBI.

Text

Partial Pressure of Oxygen in Brain Tissue (PbtO2)

In addition to the methods mentioned above, several invasive, catheter-based devices are now available which can directly monitor partial pressure of oxygen in extracellular fluid of brain tissue (PbtO2). These include the Licox [Integra, Plainsboro (New Jersey), USA] and Neurovent [Raumedic, Helmbrechts, Germany] catheters, both of which have been shown to safely and reliably measure PbtO2 in an approximately one mm3 region around catheter tip (13–15). This information theoretically represents the balance between oxygen delivery and consumption, and is influenced by changes in capillary perfusion, distance from supplying capillaries (increased in the setting of brain edema), and other barriers to oxygen diffusion (16,17). While significant interest exists in using these devices to better match cerebral oxygen delivery to demand, the exact relationship between PbtO2, secondary injury, and clinical outcome remains unclear. PbtO2 is a product of CBF and cerebral arteriovenous oxygen tension gradients rather than a direct measurement of total oxygen delivery or cerebral oxygen metabolism (17). It remains a relatively crude measurement of complex and dynamic processes that occur after severe TBI, capturing data from only a small region of interest. Subsequently, clinical data regarding use of PbtO2 to guide management has been mixed (18). On one hand, PbtO2 values lower than 15 mmHg for more than 30 minutes have been shown to be an independent predictor of unfavorable outcome and death in single center, uncontrolled retrospective studies (7,9), and several cohort studies have shown an association between treatment of low PbtO2 with improved outcomes (19–21). Interventions such as hyperoxygenation (22,23), cerebral perfusion pressure augmentation (24,25), and transfusion (26) have all been demonstrated to increase systemic oxygen delivery and augment low PbtO2. Conversely, other studies (including the largest non-randomized studies) have demonstrated either negative results or an association with worse neurological outcome and increased hospital resource utilization (27–30). Regardless of outcome, most trials to this point have been small, single-center, non-randomized, retrospective analyses. As of this writing, the Brain Tissue Oxygen Monitoring and Management in Severe Traumatic Brain Injury Phase II (BOOST-II) trial is the only randomized controlled trial examining use of PbtO2 in clinical practice. BOOST-2 demonstrated a trend favoring PbtO2 monitoring on outcome but was not powered to assess efficacy of the intervention (14*). Beyond simple categorical utility, however, many additional questions still exist regarding correct timing and location for placement of these devices given their ability to measure only a limited area of the brain.

Thus, significant equipoise exists regarding use of PbtO2 monitors in clinical management of severe TBI patients. Despite this, many believe that PbtO2 monitoring may come to play a significant role in a multimodal therapeutic approach to TBI, aiding in optimization of CBF, oxygen delivery, and brain metabolism, ultimately improving outcomes in these patients. To this end, there are currently three ongoing multicenter randomized controlled trials aimed at helping answer these questions: Brain Tissue Oxygen Monitoring and Management in Severe Traumatic Brain Injury Phase III (BOOST-3) trial, Impact of Early Optimization of Brain Oxygenation on Neurological Outcome After Severe Traumatic Brain Injury (OXY-TC) trial, and Brain Oxygen Neuromonitoring in Australia and New Zealand Assessment (BONANZA) trial, each of which will be discussed in their own section below.

BOOST-3

To date, the BOOST-II trial remains the only randomized controlled trial investigating use of PbtO2 in TBI patients (14*). This multicenter phase II trial enrolled 119 severe TBI patients with a primary goal to assess safety and feasibility of both PbtO2 monitoring and a multi-tiered treatment protocol for low PbtO2 (and/or elevated ICP). The study achieved its primary outcome, demonstrating that patients in the intervention arm had had improved cerebral oxygenation through both a lower proportion and average amount of time with a PbtO2 < 20 mm Hg. The study also demonstrated a trend towards improved clinical outcomes favoring use of PbtO2. This has prompted a phase III trial, BOOST-3, which is currently enrolling patients.

BOOST-3 (31*) is a two-arm, single-blind, randomized controlled phase III multi-center trial in which the investigators hope to demonstrate reduced mortality and improved neurologic outcome with PbtO2 monitoring as measured by the extended Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOSE) (32). It is currently enrolling across 47 sites with a target enrollment of 1094 patients. All enrolled patients require both ICP and PbtO2 monitoring. In the control arm, treating physicians are blinded to PbtO2 data. The study allows treating physician to choose from a tiered system of interventions aimed at reducing ICP and/or augmenting PbtO2 in the event of an ICP spike or brain hypoxia (see figures 1 & 2). Interventions are based on current brain trauma foundation guidelines for management of severe TBI (33*). Eligibility criteria include age over 14 with non-penetrating brain injury, a GCS <9 on admission, and requirement for ICP monitor placement. Excluded are patients with a GCS motor score of 6 (patients with reliable neurologic examinations likely do not need ICP or PbtO2 monitors as their exam can provide sufficient information about neurologic status), bilaterally absent pupillary responses, non-survivable injuries, or systemic conditions which may confound PbtO2 measurement (profound systemic hypoxia, refractory systemic hypotension). The primary outcome is functional status at 6 months as assessed by the GOSE. Secondary outcome measures include functional, cognitive, and behavioral outcome at 6 months, adverse events associated with PbtO2 vs ICP directed therapy, survival at discharge, total brain hypoxia as measured by PbtO2, and correlation of total brain hypoxia with neurological outcome. Analysis will determine outcome based on a sliding dichotomy comparing actual outcome to a predicted prognosis (34).

Figure 1. BOOST-3 Clinical Condition Types.

This matrix provides the schema for the 4 clinical conditions encountered in patients with both ICP and PbO2 monitors in place. While it is specifically taken from the BOOST-3 protocol, it is is similar to that used in all three ongoing clinical trials and the new SIBICC guidelines. ‘Type A’ reflects normal values for both monitors and does not require treatment. ‘Type B’ involves ICP elevation but normal brain oxygen values, ‘Type C’ patients have hypoxic brains but normal ICP, and ‘Type D’ patients have both brain hypoxia and ICP elevation. Treatment algorithms for each specific condition are described in figure 2.

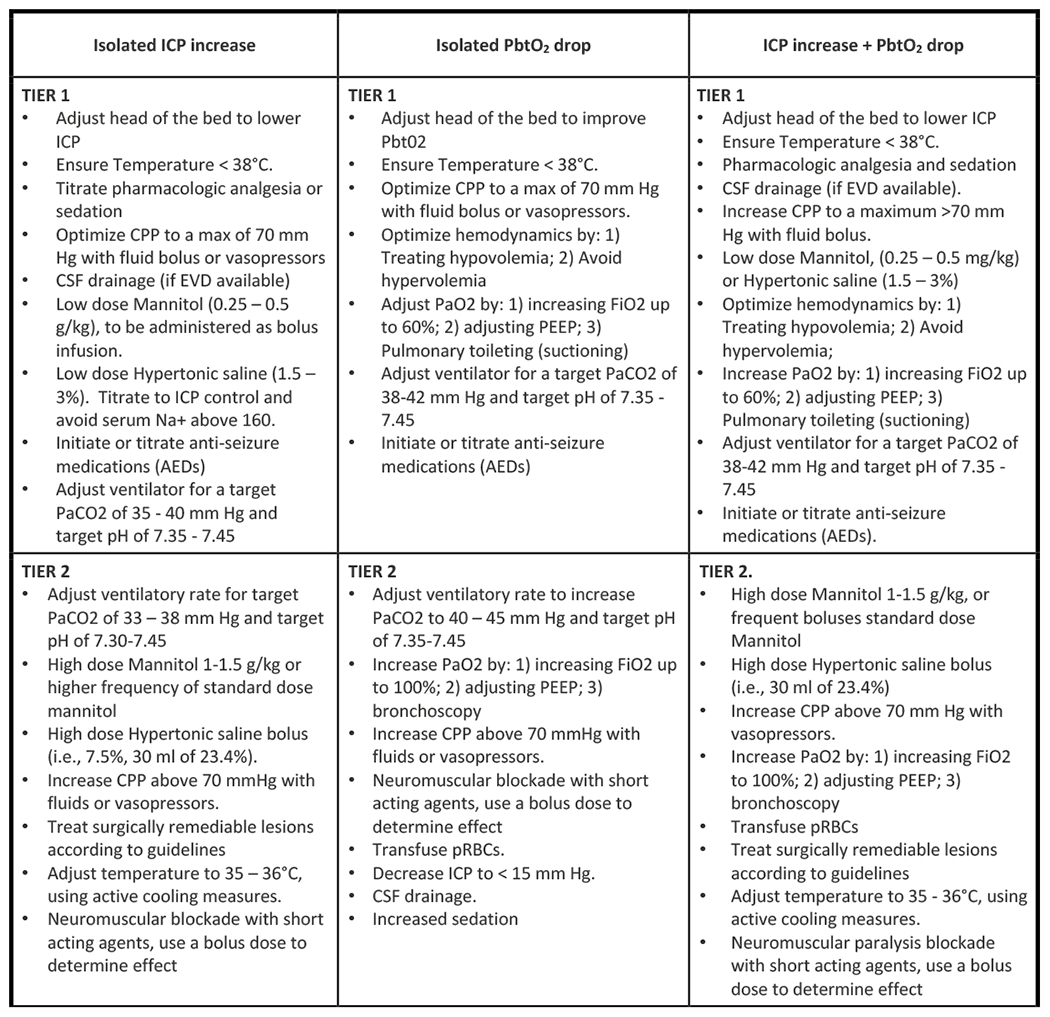

Figure 2. BOOST-3 protocol-driven treatment algorithms for patients with both ICP and PbO2 monitoring.

This figure taken from the BOOST-3 protocol shows the tiered treatment algorithms from which treating physicians may select an intervention based on patient condition as described in figure 1. Less important than the specific interventions is the tiered, protocol-driven approach and the fact that bedside physicians have a number of options to choose from in any given scenario. This protocol is pragmatic, recognizing the realities and complexity of clinical practice, especially in the TBI population. Although taken from the BOOST-3 protocol, this algorithm is also similar to those used in the other two ongoing trials, OXY-TC, and BONANZA.

OXY-TC

The OXY-TC study is a multicenter, open-labelled, randomized controlled superiority trial currently recruiting across 22 hospitals in France and aimed at assessing the impact of PbtO2 monitoring and treatment on mortality and neurologic outcomes as measured by GOSE (35**). OXY-TC aims to randomize 600 patients to either ICP monitoring alone or simultaneous ICP and PbtO2 monitoring (see figure 3). The ICP group is managed according to international guidelines to maintain ICP ≤20 mm Hg. The ICP + PbtO2 group is managed to maintain both ICP ≤20 mm Hg and PbtO2 ≥20 mm Hg. Choice of treatments is again selected by treating physicians from a pre-set list of options. Unlike BOOST-3, the study is non-blinded due to the presence or absence of the PbtO2 monitor. Inclusion criteria are similar to those of BOOST-3, capturing patients age 18-75 years admitted with non-penetrating TBI and a GCS <9 on admission who require ICP monitoring for at least 48 hours. OXY-TC further stipulates that patients must be mechanically ventilated with otherwise stable condition and excludes patients with apparent quadriplegia. Other exclusion criteria are similar to BOOST-3: GCS of 3 with bilateral fixed and dilated pupils, need for decompressive craniectomy prior to enrollment, persistent hemodynamic or respiratory instability, hypothermia, imminent mortality, or cardiac arrest on initial presentation. The primary outcome is also functional status at 6 months as assessed by GOSE. Secondary outcome measures include quality-of-life assessment, mortality, therapeutic intensity and incidence of critical events during the first 5 days. Analysis will be performed according to intention-to-treat principles and results are expected to be published in 2023.

Figure 3. OXT-TC Study Design.

The study design and flow of the OXY-TC trial. Unlike the BOOST-3 and BONANAZA trials, OXY-TC utilizes a non-blinded approach and patients in the control group do not have PbtO2 monitors placed. Other than this main difference, all three ongoing clinical trials have similar inclusion/exclusion criteria, treatment protocols, and outcome measures (namely GOSE at 6 months), allowing for relatively easy meta-analysis and validation of data.

BONANZA

There third and final ongoing clinical trial aimed at examining the potential clinical benefit of PbtO2 monitoring is the Australian BONANZA trial (36**). Conducted by the Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society Clinical Trials Group (ANZICS-CTG) across 15-18 sites internationally, enrollment has unfortunately been delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic. BONANZA is a two-arm, single-blind, randomized controlled multi-center trial aiming to enroll 860 patients. The study protocol is similar to BOOST-3: all enrolled patients will have PbtO2 monitors placed, but study participants will be randomized to either ICP management alone or ICP + PbtO2 management, with physicians being blinded to PbtO2 readings in the control group. The protocol again allows for treating physicians to choose from tiered, algorithm-based interventions aimed at augmenting PbtO2 and/or reducing ICP. Interventions are based on brain trauma foundation guidelines, with some minor modifications reflecting ANZICS-specific practices and the recent Seattle International Brain Injury Consensus Conference (SIBICC) (37*). Inclusion criteria are similar to the other two trials: qualifying patients are those age ≥17 with non-penetrating TBI and a GCS <9 requiring ICP monitoring. Patients must be unable to follow commands with reactive pupils and without refractory hypotension and/or hypoxia. BONANZA further excludes patients with coagulopathy as this may be a contraindication to intracranial bolt placement. The primary outcome is GOSE at 6 months, similar to both BOOST-3 and OXY-TC. It is worth noting again that all three ongoing clinical trials--BOOST-3, OXY-TC, and BONANZA--have similar inclusion/exclusion criteria, treatment protocols, and outcome measures (GOSE at 6 months), allowing for relatively easy meta-analysis and validation of data which will hopefully provide a definitive answer to the role of invasive parenchymal PbtO2 monitors in the near future.

Other Developments

With emerging evidence to support clinical use of PbtO2 monitoring, multiple reviews (38,39) and several guidelines have emerged in the last year describing use of PbtO2 monitoring in TBI patients. The previously mentioned SIBICC guideline used a Delphi-method-based consensus to draft a TBI treatment protocol based on a formalized consensus of 42 international, multidisciplinary neurotrauma experts for management of severe TBI patients, specifically guided by use of intracranial pressure monitors (40). They also developed a guideline for management of these patients utilizing both ICP and PbtO2 monitoring based on level III evidence and expert opinion (37*). These treatment protocols are tiered algorithms similar to those featured in the ongoing clinical trials mentioned above. Other groups have released similar consensus documents in the past year (41), endorsing PbtO2 monitoring as a safe and reliable technique for continuous point-of-care evaluation of brain oxygenation in the neurocritical patient. Pediatric guidelines for management of children with severe TBI also now include use of PbtO2 as of last year (42–44*), with level III evidence for use in appropriate patients. Other groups have also published recent guidelines for use of PbtO2 monitoring in other neurologic disease states such as subarachnoid hemorrhage (45,46).

Another recent focus in PbtO2 monitoring has been finding the ideal range for PbtO2 in severe TBI patients. In one study, detailed analysis of different PbtO2 thresholds found that 19 mmHg best discriminated patients by outcome, especially in the subacute phase (days 3-5) (47**). Furthermore, they found that it was not absolute PbtO2 values that correlated with clinical outcome, but proportion of time spent below this critical threshold. While a different single center retrospective analysis published earlier this year found that patients may benefit from higher PbtO2 thresholds (48), this second study included only 15 patients and was likely confounded by correlation of lower PbtO2 values with more severe injuries rather than suboptimal treatment, as patients were retrospectively categorized into those with high average PbtO2 (>28 mmHg) and low average PbtO2 (<28 mmHg).

Despite enthusiasm for PbtO2 monitoring, data has emerged that suggests this single value may not paint a complete picture in severe TBI. Recent studies using cerebral microdialysis have suggested that cerebral metabolic dysfunction may occur independent of PbtO2 and cerebral hypoxia after TBI. While one retrospective study of 115 patients with severe TBI found an association with higher systemic mean paO2 and improved markers of cerebral metabolism by microdialysis, they also failed to demonstrate a difference in clinal outcome (49*). Another small study of 20 patients published earlier this year demonstrated ongoing cerebral metabolic dysfunction with elevated lactate pyruvate ratios despite normal PbtO2(50**). Yet another study looked at the relationship between slow-wave fluctuations of ICP, MAP and PbtO2 and demonstrated that PbtO2 did not respond to ICP and MAP slow-wave fluctuations and therefore was not useful in derivation of cerebrovascular reactivity indices, which some believe to be the best predictors of outcome in TBI (51**, 52). This group further noted that most episodes of impaired reactivity seemed to occur in the presence of normal PbtO2 levels, an observation which supports the concept that PbtO2 may only be one part of the picture when it comes to secondary injury in TBI. Finally, a machine learning algorithm was recently created that can predict episodes of low PbtO2 prior to their occurrence (53**); should PbtO2 monitoring become more common, there is likely a significant amount to be learned from the further application of machine learning to the data collected from these monitors.

Conclusions/future research

Traumatic brain injury remains a significant clinical problem and a leading cause of death in young people. Brain hypoxia is common after TBI and great interests exists in use of PbtO2 monitoring for prevention of secondary injury after TBI. While current evidence for use of these monitors is limited, three ongoing clinical trials encompassing over 80 clinical sites and an expected 2254 patients seek to definitively answer the question of what role PbtO2 should play in management of severe TBI. In the meantime, multiple reviews and guidelines have been published in the last year detailing use of PbtO2 monitoring in clinical practice.

Key points.

While PbtO2 monitoring is a promising new tool in prevention of secondary injury after severe TBI, significant equipoise exists regarding use of PbtO2 monitors at beside.

BOOST-II, a Phase II study of PbtO2 guided management in severe TBI demonstrated the feasibility and safety of PbtO2 monitoring in these patients.

Three multi-center studies (BOOST-3, OXY-TC, and BONANZA) comparing management guided by PbtO2 and ICP measurements versus ICP alone are in progress.

International adult and pediatric guidelines now exist regarding use of PbtO2 in the clinical treatment of severe TBI patients.

Additional data from machine learning and cerebral microdialysis suggests that PbtO2 may only be one of many factors playing a role in secondary brain injury after TBI.

Acknowledgements:

2. Financial support and sponsorship: Dr. Shutter has salary support from the BOOST-3 study

Footnotes

Disclosures: Dr. Shutter is one of the principle investigators for BOOST-3, an ongoing randomized controlled trial investigating the use of PbO2 monitors in severe TBI, discussed extensively throughout this article. She is also an author on several other publications cited throughout the article, most notably BOOST-II and the SIBICC consensus guidelines.

Conflicts of Interests: Dr. Shutter is one of the principle investigators for BOOST-3, an ongoing randomized controlled trial investigating the use of PbtO2 monitors in severe TBI, discussed extensively throughout this article. She is also an author on several other publications cited throughout the article, most notably BOOST-II and the SIBICC consensus guidelines.

References:

- 1.Taylor CA, Bell JM, Breiding MJ, Xu L. Traumatic Brain Injury-Related Emergency Department Visits, Hospitalizations, and Deaths - United States, 2007 and 2013. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2017. March 17;66(9):1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roozenbeek B, Maas AIR, Menon DK. Changing patterns in the epidemiology of traumatic brain injury. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013. February 26;9(4):231–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jourdan C, Bosserelle V, Azerad S, Ghout I, Bayen E, Aegerter P, et al. Predictive factors for 1-year outcome of a cohort of patients with severe traumatic brain injury (TBI): results from the PariS-TBI study. Brain Inj. 2013. June 3;27(9):1000–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper DJ, Rosenfeld JV, Murray L, Arabi YM, Davies AR, D’Urso P, et al. Decompressive craniectomy in diffuse traumatic brain injury. N Engl J Med. 2011. April 21;364(16):1493–1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steyerberg EW, Wiegers E, Sewalt C, Buki A, Citerio G, De Keyser V, et al. Case-mix, care pathways, and outcomes in patients with traumatic brain injury in CENTER-TBI: a European prospective, multicentre, longitudinal, cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(10):923–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bouzat P, Sala N, Payen J-F, Oddo M. Beyond intracranial pressure: optimization of cerebral blood flow, oxygen, and substrate delivery after traumatic brain injury. Ann Intensive Care. 2013. July 10;3(1):23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van den Brink WA, van Santbrink H, Steyerberg EW, Avezaat CJ, Suazo JA, Hogesteeger C, et al. Brain oxygen tension in severe head injury. Neurosurgery. 2000. April;46(4):868–76; discussion 876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Longhi L, Pagan F, Valeriani V, Magnoni S, Zanier ER, Conte V, et al. Monitoring brain tissue oxygen tension in brain-injured patients reveals hypoxic episodes in normal-appearing and in peri-focal tissue. Intensive Care Med. 2007. December;33(12):2136–2142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang JJJ, Youn TS, Benson D, Mattick H, Andrade N, Harper CR, et al. Physiologic and functional outcome correlates of brain tissue hypoxia in traumatic brain injury. Crit Care Med. 2009. January;37(1):283–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oddo M, Levine JM, Mackenzie L, Frangos S, Feihl F, Kasner SE, et al. Brain hypoxia is associated with short-term outcome after severe traumatic brain injury independently of intracranial hypertension and low cerebral perfusion pressure. Neurosurgery. 2011. November 1;69(5):1037–45; discussion 1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bardt TF, Unterberg AW, Härtl R, Kiening KL, Schneider GH, Lanksch WR. Monitoring of brain tissue PO2 in traumatic brain injury: effect of cerebral hypoxia on outcome. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 1998;71:153–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valadka AB, Gopinath SP, Contant CF, Uzura M, Robertson CS. Relationship of brain tissue PO2 to outcome after severe head injury. Crit Care Med. 1998. September;26(9):1576–1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haitsma IK, Maas AIR. Advanced monitoring in the intensive care unit: brain tissue oxygen tension. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2002. April;8(2):115–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *14.Okonkwo DO, Shutter LA, Moore C, Temkin NR, Puccio AM, Madden CJ, et al. Brain Oxygen Optimization in Severe Traumatic Brain Injury Phase-II: A Phase II Randomized Trial. Crit Care Med. 2017. November;45(11):1907–1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The only randomized controlled trial studying PbtO2 monitoring as of this writing. Demonstrated safety and feasibility of PbO2 monitoring, but also a trend towards better clinical outcomes with PbO2 monitoring which did not achieve statistical significance.

- 15.Bailey RL, Quattrone F, Curtin C, Frangos S, Maloney-Wilensky E, Levine JM, et al. The Safety of Multimodality Monitoring Using a Triple-Lumen Bolt in Severe Acute Brain Injury. World Neurosurg. 2019. October;130:e62–e67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Menon DK, Coles JP, Gupta AK, Fryer TD, Smielewski P, Chatfield DA, et al. Diffusion limited oxygen delivery following head injury. Crit Care Med. 2004. June;32(6):1384–1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenthal G, Hemphill JC, Sorani M, Martin C, Morabito D, Obrist WD, et al. Brain tissue oxygen tension is more indicative of oxygen diffusion than oxygen delivery and metabolism in patients with traumatic brain injury. Crit Care Med. 2008. June;36(6):1917–1924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nangunoori R, Maloney-Wilensky E, Stiefel M, Park S, Andrew Kofke W, Levine JM, et al. Brain tissue oxygen-based therapy and outcome after severe traumatic brain injury: a systematic literature review. Neurocrit Care. 2012. August;17(1):131–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stiefel MF, Spiotta A, Gracias VH, Garuffe AM, Guillamondegui O, Maloney-Wilensky E, et al. Reduced mortality rate in patients with severe traumatic brain injury treated with brain tissue oxygen monitoring. J Neurosurg. 2005. November;103(5):805–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spiotta AM, Stiefel MF, Gracias VH, Garuffe AM, Kofke WA, Maloney-Wilensky E, et al. Brain tissue oxygen-directed management and outcome in patients with severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg. 2010. September;113(3):571–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Narotam PK, Morrison JF, Nathoo N. Brain tissue oxygen monitoring in traumatic brain injury and major trauma: outcome analysis of a brain tissue oxygen-directed therapy. J Neurosurg. 2009. October;111(4):672–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tolias CM, Reinert M, Seiler R, Gilman C, Scharf A, Bullock MR. Normobaric hyperoxia--induced improvement in cerebral metabolism and reduction in intracranial pressure in patients with severe head injury: a prospective historical cohort-matched study. J Neurosurg. 2004. September;101(3):435–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nortje J, Coles JP, Timofeev I, Fryer TD, Aigbirhio FI, Smielewski P, et al. Effect of hyperoxia on regional oxygenation and metabolism after severe traumatic brain injury: preliminary findings. Crit Care Med. 2008. January;36(1):273–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnston AJ, Steiner LA, Chatfield DA, Coles JP, Hutchinson PJ, Al-Rawi PG, et al. Effect of cerebral perfusion pressure augmentation with dopamine and norepinephrine on global and focal brain oxygenation after traumatic brain injury. Intensive Care Med. 2004. May;30(5):791–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnston AJ, Steiner LA, Coles JP, Chatfield DA, Fryer TD, Smielewski P, et al. Effect of cerebral perfusion pressure augmentation on regional oxygenation and metabolism after head injury. Crit Care Med. 2005. January 1;33(1):189–95; discussion 255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zygun DA, Nortje J, Hutchinson PJ, Timofeev I, Menon DK, Gupta AK. The effect of red blood cell transfusion on cerebral oxygenation and metabolism after severe traumatic brain injury. Crit Care Med. 2009. March 1;37(3):1074–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meixensberger J, Jaeger M, Väth A, Dings J, Kunze E, Roosen K. Brain tissue oxygen guided treatment supplementing ICP/CPP therapy after traumatic brain injury. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003. June;74(6):760–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adamides AA, Cooper DJ, Rosenfeldt FL, Bailey MJ, Pratt N, Tippett N, et al. Focal cerebral oxygenation and neurological outcome with or without brain tissue oxygen-guided therapy in patients with traumatic brain injury. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2009. November;151(11):1399–1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martini RP, Deem S, Yanez ND, Chesnut RM, Weiss NS, Daniel S, et al. Management guided by brain tissue oxygen monitoring and outcome following severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg. 2009. October;111(4):644–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Green JA, Pellegrini DC, Vanderkolk WE, Figueroa BE, Eriksson EA. Goal directed brain tissue oxygen monitoring versus conventional management in traumatic brain injury: an analysis of in hospital recovery. Neurocrit Care. 2013. February;18(1):20–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *31.BOOST-3 | SIREN [Internet]. [cited 2020 Oct 3]. Available from: https://siren.network/clinical-trials/boost-3; One of three ongoing randomized clinical trials aimed at determining whether PbtO2-guided treatment improves neurologic outcome. A two-arm, single-blind, randomized, controlled, phase III, multi-center trial comparing PbtO2 and ICP monitoring vs ICP monitoring alone.

- 32.Weir J, Steyerberg EW, Butcher I, Lu J, Lingsma HF, McHugh GS, et al. Does the extended Glasgow Outcome Scale add value to the conventional Glasgow Outcome Scale? J Neurotrauma. 2012. January 1;29(1):53–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *33.Carney N, Totten AM, O’Reilly C, Ullman JS, Hawryluk GWJ, Bell MJ, et al. Guidelines for the management of severe traumatic brain injury, fourth edition. Neurosurgery. 2017. January 1;80(1):6–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Guideline from which the tiered, algorithm-based treatments for augmenting PbtO2 in the three ongoing clinical trials are derived.

- 34.Steyerberg EW, Mushkudiani N, Perel P, Butcher I, Lu J, McHugh GS, et al. Predicting outcome after traumatic brain injury: development and international validation of prognostic scores based on admission characteristics. PLoS Med. 2008. August 5;5(8):e165; discussion e165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **35.Payen J-F, Richard M, Francony G, Audibert G, Barbier EL, Bruder N, et al. Comparison of strategies for monitoring and treating patients at the early phase of severe traumatic brain injury: the multicentre randomised controlled OXY-TC trial study protocol. BMJ Open. 2020. August 20;10(8):e040550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; One of three ongoing randomized clinical trials aimed at determining whether PbtO2-guided treatment improves neurologic outcome. Two-arm, unblinded, randomized, controlled, phase III, multi-center trial being conducted across France.

- **36.BONANZA - ANZICS [Internet]. [cited 2020 Oct 3]. Available from: https://www.anzics.com.au/current-active-endorsed-research/bonanza/; One of three ongoing randomized clinical trials aimed at determining whether PbtO2-guided treatment improves neurologic outcome. A two-arm, single-blind, randomized, controlled, phase III, multi-center trial comparing PbO2 and ICP monitoring vs ICP monitoring alone.

- *37.Chesnut R, Aguilera S, Buki A, Bulger E, Citerio G, Cooper DJ, et al. A management algorithm for adult patients with both brain oxygen and intracranial pressure monitoring: the Seattle International Severe Traumatic Brain Injury Consensus Conference (SIBICC). Intensive Care Med. 2020. May;46(5):919–929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A consensus statement issued by a group 42 experienced and actively practicing TBI opinion leaders that aimed to establish a modern TBI protocol for adult patients with both ICP and PbtO2 monitors in place.

- 38.Rakhit S, Nordness MF, Lombardo SR, Cook M, Smith L, Patel MB. Management and challenges of severe traumatic brain injury. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2020. September 11; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ruhatiya RS, Adukia SA, Manjunath RB, Maheshwarappa HM. Current status and recommendations in multimodal neuromonitoring. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2020. May;24(5):353–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hawryluk GWJ, Aguilera S, Buki A, Bulger E, Citerio G, Cooper DJ, et al. A management algorithm for patients with intracranial pressure monitoring: the Seattle International Severe Traumatic Brain Injury Consensus Conference (SIBICC). Intensive Care Med. 2019. October 28;45(12):1783–1794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Domínguez-Roldán JM, Lubillo S, Videtta W, Llompart-Pou JA, Badenes R, Rivas JM, et al. International consensus on the monitoring of cerebral oxygen tissue pressure in neurocritical patients. Neurocirugia (Astur). 2020;31(1):24–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *42.Kochanek PM, Tasker RC, Bell MJ, Adelson PD, Carney N, Vavilala MS, et al. Management of Pediatric Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: 2019 Consensus and Guidelines-Based Algorithm for First and Second Tier Therapies. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2019;20(3):269–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Pediatric guidelines for the management of severe traumatic brain injury in children. These mark the first time such guidelines have included PbtO2 monitoring.

- 43.Appavu B, Burrows BT, Foldes S, Adelson PD. Approaches to multimodality monitoring in pediatric traumatic brain injury. Front Neurol. 2019. November 26;10:1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kochanek PM, Tasker RC, Carney N, Totten AM, Adelson PD, Selden NR, et al. Guidelines for the management of pediatric severe traumatic brain injury, third edition: update of the brain trauma foundation guidelines. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2019;20(3S Suppl 1):S1–S82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rass V, Solari D, Ianosi B, Gaasch M, Kofler M, Schiefecker AJ, et al. Protocolized brain oxygen optimization in subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care. 2019;31(2):263–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fiore M, Bogossian E, Creteur J, Oddo M, Taccone FS. Role of brain tissue oxygenation (PbtO2) in the management of subarachnoid haemorrhage: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open. 2020. September 15;10(9):e035521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **47.Hirschi R, Hawryluk GWJ, Nielson JL, Huie JR, Zimmermann LL, Saigal R, et al. Analysis of high-frequency PbtO2 measures in traumatic brain injury: insights into the treatment threshold. J Neurosurg. 2018. October 1;1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Prospective study analyzing high-frequency PbtO2 data which determined a therapeutic window for PbtO2 in TBI patients. Of note, the investigators found that it was not absolute PbtO2 values that correlated with clinical outcome, but proportion of time spent below a critical threshold, suggesting that traditional treatment thresholds may be suboptimal.

- 48.Patchana T, Wiginton J, Brazdzionis J, Ghanchi H, Zampella B, Toor H, et al. Increased brain tissue oxygen monitoring threshold to improve hospital course in traumatic brain injury patients. Cureus. 2020. February 27;12(2):e7115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *49.Wettervik TS, Engquist H, Howells T, Lenell S, Rostami E, Hillered L, et al. Arterial Oxygenation in Traumatic Brain Injury-Relation to Cerebral Energy Metabolism, Autoregulation, and Clinical Outcome. J Intensive Care Med. 2020. July 27;885066620944097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Retrospective study of 115 patients with severe TBI which found an association with higher mean paO2 and improved markers of cerebral metabolism by microdialysis, but which failed to demonstrate a difference in clinal outcome.

- **50.Marini CP, Stoller C, McNelis J, Del Deo V, Prabhakaran K, Petrone P. Correlation of brain flow variables and metabolic crisis: a prospective study in patients with severe traumatic brain injury. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2020. July 27; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Small European study which demonstrated that cerebral metabolic crisis as determined by microdialysis can still occur despite PbtO2 normalization. Severe metabolic crisis, however, was associated with low PbtO2 and correlated with a poor prognosis in this study.

- **51.Zeiler FA, Beqiri E, Cabeleira M, Hutchinson PJ, Stocchetti N, Menon DK, et al. Brain tissue oxygen and cerebrovascular reactivity in traumatic brain injury: A collaborative european neurotrauma effectiveness research in traumatic brain injury exploratory analysis of insult burden. J Neurotrauma. 2020. September 1;37(17):1854–1863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Study utilizing high frequency physiology data from a European cohort to look for markers of poor prognosis. While the study did find episodes of both elevated ICP and low PbtO2 correlated with poor prognosis, impaired cerebral reactivity indices appeared to display the most consistent associations with global outcome in TBI and the majority of the reactivity impairment occurred in the presence of normal PbtO2 levels.

- 52.Zeiler FA, Cabeleira M, Hutchinson PJ, Stocchetti N, Czosnyka M, Smielewski P, et al. Evaluation of the relationship between slow-waves of intracranial pressure, mean arterial pressure and brain tissue oxygen in TBI: a CENTER-TBI exploratory analysis. J Clin Monit Comput. 2020. May 16; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **53.Lazaridis C, Rusin CG, Robertson CS. Secondary brain injury: Predicting and preventing insults. Neuropharmacology. 2019;145(Pt B):145–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Article describing a machine learning-based predictive model able to predict physiologic crises in TBI patients prior to their occurrence based on ICP and PbtO2 data, theoretically offering the opportunity for earlier intervention.