Abstract

Whether to administer purgative cleansing and oral antibiotics before colon surgery as a method to prevent postoperative infections, once standard of care, is now being considered unnecessary with today’s advancements of care. A new study questions the efficacy of this bowel preparation approach with a prospective randomized trial.

Across all specialties of surgery, the highest rate of surgical site infections (SSIs) following elective surgery are those that develop in patients undergoing colon surgery1. This finding is unsurprising given that the colon harbors the highest density of bacteria in the body. Given these circumstances, the concept and practice of ‘intestinal antisepsis’ emerged over 60 years ago and is attributed to iconic figures in surgery, including Dragsted, Goliger, Nichols and Condon, among others2,3. These surgeons pioneered the idea of purgative cleansing of the bowel combined with oral non-absorbable antibiotics to not only eliminate the stool mass from the operative site, but also to distribute the oral antibiotics so they decontaminate the colon of its SSI-related pathogens2,3. This process is now labelled mechanical bowel preparation or mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation (MOABP) and became widely applied across continents, following which surgeons witnessed historically low rates of SSIs4,5. Yet as the 1990s approached, new staplers and suture material, improved anesthesia and, most importantly, newer and more powerful intravenous antibiotics made some surgeons consider that MOABP perhaps was no longer necessary. As a result, surgeons became emboldened to abandon MOABP altogether with seemingly equivalent results to those patients that received it. Today, across various centers of excellence, MOABP seems to be under attack — many surgeons say you do not need it, various societal guidelines mandate it and, most importantly, patients hate it.

To establish whether a MOABP is still necessary in the current era of colon surgery, a new study published in the Lancet from four hospitals in Finland details a randomized prospective trial comparing patients undergoing elective colon surgery assigned to either MOABP or no bowel preparation (NBP)6. This trial is the first of its kind to settle this longstanding controversy. On the day before surgery, patients assigned to MOABP were prepared by drinking 2 L of polyethylene glycol (PEG) and 1 L of clear fluid before 18:00, and took 2 g of neomycin (an aminoglycoside antibiotic) orally at 19:00 and 2 g of metronidazole (antimicrobial drug active against anaerobic bacteria and protozoa) orally at 23:00 Although the use of PEG is standard in this protocol, a single dose of the chosen antibiotics is not; most centers administer them three times (every 8 h) over the course of the operation preparation. Results demonstrated that an SSI was detected in 13 (7%) of 196 patients randomly assigned to MOABP, and in 21 (11%) of 200 patients randomly assigned to NBP (odds ratio 1.65, 95% CI 0.80–3.40; P = 0.17). Anastomotic dehiscence was reported in 7 (4%) of 196 patients in the MOABP group and in 8 (4%) of 200 in the NBP group. Two patients died in the NBP group and none in the MOABP group within the 30 day follow-up period. Given the non-superiority of MOABP to reduce SSI rates in the current study, the authors concluded that “the current recommendations of using MOABP for colectomies to reduce SSIs or morbidity should be reconsidered.” Although the authors clearly state the primary limitation of the study — that it was powered to detect an 8% difference in SSI rates, and only detected a 4% difference and was, therefore, underpowered — the fact that 78% of the patients underwent laparoscopy, which itself is known to dramatically reduce SSI rates and that many of the cases were low-risk colon surgeries such as a right hemicolectomy, should be recognized. Yet, perhaps the most important point of this outstanding study for which the authors should be commended is the phrase “current recommendations of using MOABP for colectomies”, ‘current recommendations’ being the operative term.

To advance a discussion on whether use of MOABP in elective colon surgery is needed (or not) it is useful to consider the scientific premise upon which this procedure is based. Originally it was reasoned that the contiguous contamination by intestinal bacteria of otherwise sterile tissues (such as peritoneum, subcutaneous fat and skin) was the mechanism by which serious SSIs developed following colon surgery. Culture results at the species level seems to confirm this assertion, and, at that time (1970s–1980s), the combination of both purgative cleansing and oral antibiotics was the most effective strategy to reduce SSI-related pathogens in the colon7. Much of the impetus to eliminate the use of MOABP is based on the assumption that newer antibiotics are just as effective at eliminating the offending SSI-related pathogens — a yet unproven claim. However, shockingly absent from virtually every study on MOABP in colon surgery in the past several decades is culture-level evidence indicating that the most common SSI-related pathogens, that is those that are cultured from infected wound sites, are in fact eliminated by one regimen (MOABP) versus the other (NBP). For example, studies have suggested that up to 50% of the pathogens that are recovered from SSIs are resistant to the antibiotics used for prophylaxis8. This finding begs the following question, has the decades-old formulation of MOABP that we still use today become outdated?

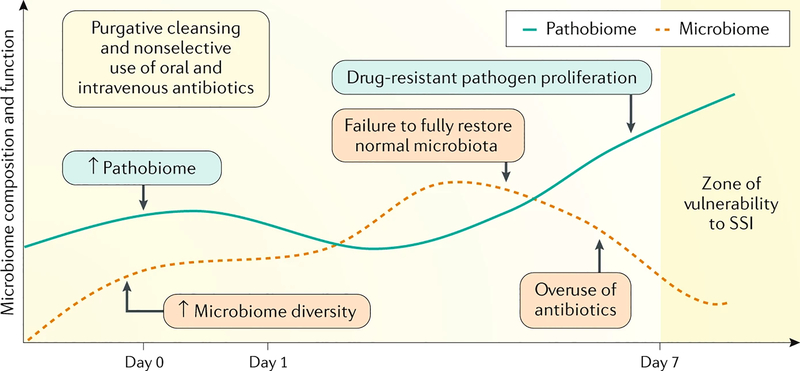

We agree with the authors’ conclusions that “the current recommendations of using MOABP for colectomies to reduce SSIs or morbidity should be reconsidered”, but here we assert that MOABP should not simply be eliminated, but rather recalibrated to emerging concepts in microbiology (Fig. 1). It is now well appreciated that the composition and function of the intestinal microbiota plays a key part in both health and disease9. Colon surgery is now being practiced in an era of routine consumption of high-fat and processed Western-style foods, and excessive exposure to antibiotics, both via our food and those that are promiscuously prescribed, and in patients with cancer who are increasingly exposed to preoperative chemotherapy and radiation. These variables dramatically influence the microbiome10, yet have remained completely unaccounted for when prescribing a one-size-fits-all MOABP. It is now an opportune time to apply next-generation technology to inform the development of a ‘Bowel Prep 2.0’ that can preserve the beneficial effects of the microbiome while simultaneously containing those pathogens that cause SSIs10. The first step in this process will require studies that depart from randomly assigning patients to a decades-old MOABP versus NBP to those that incorporate a detailed analysis of the microorganisms at play before, during and after surgery. Once this aspect has been achieved, then non-antibiotic approaches can be developed that provide a more eco-neutral approach to selectively contain SSI-related pathogens while preserving those members of the gut microbiota that actually benefit the host in terms of recovery10.

Figure 1. Preparing the bowel for surgery in the era of the microbiome.

When non-selective approaches to eliminate all potential pathogens from the gut are used before colon surgery such as with mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation, both the microbiome and pathobiome are affected. The downside of this approach is the disruption of the delicate balance between pathogen proliferation and its natural suppression by refaunation of the normal microbiota under such circumstances. On the other hand, empiric use of intravenous antibiotics alone might not eliminate surgical site infection (SSI)-related pathogens, especially those that have become antibiotic resistant. Genetic sequencing and dynamic tracking of the microbiome following surgery is needed to inform the development and design of ‘Bowel Prep 2.0’.

Acknowledgements

J.C.A. acknowledges support from NIHR Public Health Research Programme grant R01- GM062344–18.

References

- 1.Paulson EC, Thompson E & Mahmoud N Surgical site infection and colorectal surgical procedures: a prospective analysis of risk factors. Surg. Infect 18, 520–526 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenberg IL et al. Preparation of the intestine in patients undergoing major large-bowel surgery, mainly for neoplasms of the colon and rectum. Br. J. Surg 58, 266–269 (1971). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zelhart MD et al. Preoperative antibiotic colon preparation: have we had the answer all along? J. Am. Coll. Surg 219, 1070–1077 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McChesney SL et al. Current U.S. pre-operative bowel preparation trends: a 2018 survey of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons members. Surg. Infect 10.1089/sur.2019.125 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Battersby CLF, Battersby NJ, Slade DAJ, Soop M & Walsh CJ Preoperative mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation to reduce infectious complications of colorectal surgery - the need for updated guidelines. J. Hosp. Infect 101, 295–299 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koskenvuo L et al. Mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation versus no bowel preparation for elective colectomy (MOBILE): a multicentre, randomised, parallel, single-blinded trial. Lancet 394, 840–848 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nichols RL, Choe EU & Weldon CB Mechanical and antibacterial bowel preparation in colon and rectal surgery. Chemotherapy 51 (Suppl. 1), 115–121 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teillant A et al. Potential burden of antibiotic resistance on surgery and cancer chemotherapy antibiotic prophylaxis in the USA: a literature review and modelling study. Lancet Infect. dis 15, 1429–1437 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gilbert JA et al. Microbiome-wide association studies link dynamic microbial consortia to disease. Nature 535, 94–103 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alverdy JC et al. Preparing the bowel for surgery: learning from the past and planning for the future. J. Am. Coll. Surg 225, 324–332 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]