Abstract

Study objective

Opioid use disorder (OUD) is on the rise nationwide with increasing emergency department (ED) visits and deaths secondary to overdose. Although previous research has shown that patients who are started on buprenorphine in the ED have increased engagement in addiction treatment, access to on‐demand medications for OUD is still limited, in part because of the need for linkages to outpatient care. The objective of this study is to describe emergency and outpatient providers’ perception of local barriers to transitions of care for ED‐initiated buprenorphine patients.

Methods

Purposive sampling was used to recruit key stakeholders, identified as physicians, addiction specialists, and hospital administrators, from 10 EDs and 11 outpatient clinics in King County, Washington. Twenty‐one interviews were recorded and transcribed and then coded using an integrated deductive and inductive content analysis approach by 2 team members to verify accuracy of the analysis. Interview guides and coding were informed by the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR), which provides a structure of domains and constructs associated with effective implementation of evidence‐based practice.

Results

From the 21 interviews with emergency and outpatient providers, this study identified 4 barriers to transitions of care for ED‐initiated buprenorphine patients: scope of practice, prescribing capacity, referral incoordination, and loss to follow‐up.

Conclusion

Next steps for implementation of this intervention in a community setting include establishing a standard of care for treatment and referral for ED patients with OUD, increasing buprenorphine prescribing capacity, creating a central repository for streamlined referrals and follow‐up, and supporting low‐barrier scheduling and navigation services.

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Background

The United States is combatting an opioid epidemic, and emergency physicians are on the frontlines, with fatal opioid overdose rates and emergency department (ED) visits related to opioids on the rise. 1 , 2 Management of opioid use disorder (OUD) in the ED and linkage to ongoing care are critical to addressing this crisis. 3 , 4 , 5 , 6

Patients treated with medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) have improved survival and decreased rates of ED visits, overdose, and opioid use compared to those who do not receive medical intervention. 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 Current published guidelines for the treatment of OUD recommend initiating buprenorphine as soon as possible in the clinic or at home with self‐starts rather than waiting for a comprehensive psychosocial assessment. 11 D'Onofrio et al. demonstrated improved retention in treatment and reduced illicit opioid use in those who received ED‐initiated buprenorphine and referral to outpatient care. 3 A recent review emphasized that improving care for patients with OUD begins in the ED with medical management and a transition to care for ongoing treatment. 12 Despite this evidence, few patients receive MOUD, 13 with many emergency physicians citing insufficient training and inadequate linkages to care. 4

1.2. Importance

Accelerating the use of ED‐initiated buprenorphine coupled with a successful referral to outpatient care will improve the lives of those with OUD. Each institution plays its role. EDs screen eligible patients, dispense and/or prescribe buprenorphine, and then provide outpatient referrals; whereas, outpatient clinics accept referrals, continue buprenorphine, and retain patients in treatment. Although this transition of care involves a potentially complicated information exchange between the ED and outpatient clinics, previous research incompletely describes barriers to this handoff by including only the perspective of emergency physicians. 4 , 5 , 6 Through outpatient providerinput, we address this gap in the literature by identifying the obstacles in care coordination faced by patients once they leave the ED.

1.3. Goals of this investigation

The objective of this study is to describe emergency and outpatient providers’ perception of barriers to transitions of care for ED‐initiated buprenorphine patients. We define this intervention as the ED management of patients with OUD (eg, dispensing and/or prescribing buprenorphine), outpatient referral, and retention in ongoing care. These results will inform key stakeholders, promote the uptake of evidence‐based practice, and encourage the development of procedures that can be implemented locally and beyond.

The Bottom Line

The barriers to initiating buprenorphine in the ED with emergency physicians, addiction specialists and administrators were explored. The discussion included concerns about the appropriateness of this practice in the ED, issues with training requirements, availability of referrals, and concern about loss to follow up.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study design and setting

This qualitative study uses an integrated deductive and inductive content analysis approach 15 to assess the complexity of transitions of care for ED‐initiated buprenorphine patients by analyzing the perspectives of both emergency and outpatient providers. The interview guides were informed by the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR). 14 , 16 By providing a consistently applied set of analytical categories, consisting of “constructs” situated within “domains,” the CFIR simplifies processes, highlights barriers, and identifies potential areas of improvement. Because the intervention was described as the transition of care for ED‐initiated buprenorphine patients, this study took a novel approach by defining the inner setting as the healthcare institutions on both ends of the transition of care, emergency departments and outpatient clinics. Twenty‐one interviews were recorded, transcribed, and then coded deductively using existing CFIR 14 codes (ie, deductive approach) and codes created from reviewing a sample of ED and outpatient transcripts (ie, inductive approach). 17

This study also was conducted with community engagement as part of a larger initiative to improve care for patients with OUD in King County, Washington. The Emergency Department Opioid Learning Collaborative in King County was created in 2017 to develop a countywide approach to care for patients with OUD. It is composed of local emergency medicine physicians, ED medical directors, and public health officials. Similarly, the King County Quarterly MOUD Coordination Meeting, created in 2018, is a group of outpatient providers from behavioral health agencies, community‐based organizations, and health systems in the county tasked with reducing local opioid use through expanding access to treatment, decreasing and preventing opioid‐related overdoses, and improving opioid prescribing practices. Semi‐structured interviews were conducted with members of both organizations from February 2019 to July 2019. The study was reviewed by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board and determined to be exempt.

2.2. Selection of participants

Participants were physicians, addiction specialists, hospital administrators, pharmacists, and social workers, who were identified as leading their institutions’ efforts to improve the care of people with OUD. 6 Importantly, some did not describe themselves as champions of MOUD or harm reduction. Interviews took place with a range of 1–5 key stakeholders from all 10 hospitals in the Emergency Department Opioid Learning Collaborative and 11 outpatient clinics in the King County Quarterly MOUD Coordination Meeting (Table 1). The clinics were purposively selected based upon their existing relationship with Public Health‐Seattle & King County.

TABLE 1.

Demographics of participant organizations

| Emergency department | n = 10 |

|---|---|

| Location | |

| Urban | 5 (50%) |

| Suburban | 4 (40%) |

| Rural | 1 (10%) |

| Affiliation | |

| Academic | 2 (20%) |

| Community | 8 (80%) |

| Process | |

| Employ waivered emergency providers | 5 (50%) |

| Institute a protocol for ED induction of buprenorphine | 4 (40%) |

| Institute a protocol for home induction of buprenorphine | 2 (20%) |

| Refer patients to an outpatient clinic for ongoing buprenorphine | 4 (40%) |

| Outpatient clinics | n = 10 |

|---|---|

| Location | |

| Urban | 6 (55%) |

| Suburban | 5 (45%) |

| Affiliation | |

| Academic | 2 (20%) |

| Behavioral health agency | 4 (36%) |

| Federally qualified health center | 3 (27%) |

| Tribal | 2 (18%) |

| Public health | 1 (9%) |

| Process | |

| Mechanism for after‐hour referrals/appointments | 5 (45%) |

| Weekend hours | 2 (18%) |

2.3. Method of measurement

Semi‐structured interviews were conducted by phone or in‐person at a convenient location to the participant(s) by 2 members of the study team (CEF and BF). CEF is an emergency physician and buprenorphine prescriber and BF is a harm reductionist and strategic advisor for Public Health‐Seattle & King County. Both regularly participated in the Emergency Department Opioid Learning Collaborative. All interviews were audio recorded and then transcribed. The average interview time was 38.1 minutes with a standard deviation of 17.8 minutes. Interviews were conducted with key stakeholders from all EDs participating in the Emergency Department Opioid Learning Collaborative and purposively sampled outpatient clinics until data saturation was reached. This study used 2 separate but related interview guides for ED and outpatient providers (Appendix 1 and Appendix 2), composed of introductory inquiries about the interviewee's role within the organization and open‐ended questions informed by the CFIR theoretical framework. 14 We chose to focus our interviews on constructs situated within 4 of the 5 CFIR domains: intervention, outer setting, inner setting, and process. The questions were iteratively refined based on initial interviews and preliminary data analysis.

2.4. Primary data analysis

Data from public resources and interviews were analyzed using descriptive statistics to describe the location, affiliation, and process of the EDs and outpatient clinics involved in the study (Table 1). All interview transcripts were entered into qualitative data management software after the identifying features of interviewees were removed (Dedoose; SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC, Manhattan Beach, CA). Data were coded using an integrated deductive and inductive content analysis approach 15 , 18 by members of the research team (CEF, SCM, and LKW). 18 , 19 CEF provided context and depth to the analysis by engaging in both the interviews and coding. SCM is a research assistant with extensive training in qualitative methods. LKW is an emergency physician and public health researcher focused on ED‐based interventions for substance use disorders; she also participated in the Emergency Department Opioid Learning Collaborative.

A codebook was developed using existing CFIR 14 codes deductively and codes created from reviewing a sample of ED and outpatient transcripts inductively. 17 This CFIR‐informed 14 codebook was tested subsequently by each member of the coding team using another sample of transcripts. Inconsistencies were addressed through discussion with frequent updates to the codebook. Once consensus was reached, 2 investigators (CEF and SCM) independently coded the rest of the transcripts, cross‐checked their work for validity, and applied the final codes to each transcript. Because an integrated deductive and inductive content analysis approach was used, the summation of these codes did not strictly follow the CFIR but instead resulted in themes that encompassed 4 major barriers to transitions of care. 17

3. RESULTS

We interviewed physicians, addiction specialists, and hospital administrators from 10 EDs and 11 outpatient clinics. Half of the EDs were suburban or rural, and many were located in community hospitals without x‐waivered providers or protocols for buprenorphine induction. The outpatient clinics were primarily urban behavioral health agencies and very few had a mechanism for after‐hour referrals or hours during the weekend (Table 1).

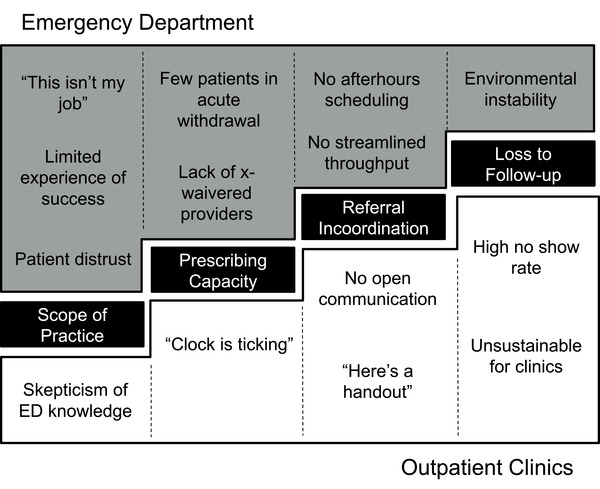

From the 21 interviews with emergency and outpatient providers, 4 major barriers around transitions of care for ED‐initiated buprenorphine patients were identified through integrated deductive and inductive content analysis: scope of practice, prescribing capacity, referral incoordination, and loss to follow‐up (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Barriers to transitions of care for ED‐initiated buprenorphine patients

3.1. Barrier 1: Scope of practice

Interviewees expressed concern that the treatment of OUD in the ED is outside their scope of practice, making this intervention seem incompatible with their perceived norms and values. Despite frequently caring for patients with addiction, many emergency providers embraced a “this isn't my job” attitude; they described OUD as a chronic condition like hypertension and diabetes mellitus, placing it under the purview of primary care and not acute care services. One explained, “It's actually something that people actively fought against, saying, ‘I don't do public health in the emergency department, that's what public health people do. This isn't my job. My job is to save heart attacks and put trauma people back together, not to get people off of drugs, that's somebody else's problem.’” Similarly, another expressed, “I'm here to take care of the acute stuff. We didn't start the problem [with the opioid crisis], and now all of a sudden we're trying to step in and fix this. I'm not sure if it's our role to fix.”

Emergency providers also were concerned about the effectiveness of OUD treatment in the ED because they see the adverse effects of OUD every day but rarely encounter those in recovery. One described, “It's always good to get feedback on what happens to these people, but we don't. That's emergency care. It's fractured. It would be good to get some positive feedback that it's actually helping.” An outpatient provider emphasized the differences in clinical environments by explaining, “And I think that the emergency medicine community … They see a highly enriched population of people who are continuing to struggle with their addiction. A lot of people who work outpatient benefit from a more balanced perspective. I see people in long‐term recovery, I see people still struggle. So [in the ED] you kind of get this skewed, ‘Nobody's getting better; this is futile.’”

Because of these biases, EDs have not historically been comfortable environments for patients with OUD. After describing how patients were inadequately treated for their acute withdrawal symptoms in the past, an emergency physician explained, “Interestingly, we don't get that many people in withdrawal. People on heroin are smart enough to [use] before they come in.” Another reported, “One of the barriers for patients is often being judged. I have to say physicians may not welcome those patients [with OUD] with open arms. We have to interrupt that prejudice and recognize this as a chronic disease, so patients may be more likely to be honest about their addiction and ask for help.”

Additionally, several outpatient clinicians expressed skepticism of the emergency providers’ training and expertise in addiction medicine based upon previous negative experiences with referred patients. One interviewee described discomfort in having to inform a referred patient that he could not be started on naltrexone or Vivitrol during his appointment because he was given a dose of buprenorphine in the emergency department the previous day. This provider explained, “I hope that the people doing the inductions in the EDs are aware and thinking about all the nuances with medication‐assisted treatment. It would be helpful if people who have some specialized experience or knowledge about the medications are able to engage with the clients and help them make informed treatment decisions even in the ED and it's not just an automatic: ‘Okay they're here for an opiate overdose, give them Suboxone.’”

3.2. Barrier 2: Prescribing capacity

Because of their lack of prescribing capacity, EDs have not effectively integrated a streamlined transition of care for ED‐initiated buprenorphine patients into their workflow. Although all emergency providers can dispense single doses of buprenorphine to patients in acute withdrawal, there are very few opportunities to do this. Interviewees describe patients, distrustful of the healthcare system, using opioids immediately prior to presenting to the ED for fear of inadequate pain control and judgment of drug‐seeking behavior. An emergency physician remarked, “How do we address the needs of patients coming in with an abscess and obviously using IV heroin but they're not in active withdrawal? Those are much more common, I mean like 10 to 1, [than] the ones who come in withdrawal and asking for help. That [population is actually] a pretty small number [compared to] the ones who come in with their third abscess in a year.”

In order to truly address their patients’ needs, providers must undergo 8–24 hours of DATA 2000 (also known as x‐waiver) training to prescribe buprenorphine. Prescribing buprenorphine not only allows ED providers to reach more patients, since it permits them to treat individuals who are not in acute withdrawal, but it also relieves outpatient providers who often cannot immediately schedule referrals because of logistical constraints. An ED provider explained, “I feel like if [buprenorphine] was more available, people would be more likely to even take the referral. I feel like people with heroin addiction don't even take us up on it very often.” An outpatient provider emphasized the importance of prescribing rather than dispensing a single dose by stating, “I think dispensing is fine, but it's going to be hard to find next‐day access, and it really puts the crunch on the patient, too. It gives them very little flexibility. It's like a clock is ticking, but at least you have 3 days, or 5 days, or whatever the ER doc's willing to write for, compared to the half‐life of the med in their system. So, I think that getting the waiver is a big barrier.”

Emergency physicians, however, find it difficult to obtain these waivers due to the significant time commitment required for the training, their institution's prioritization of other issues, and the paucity of financial compensation. A medical director explained, “Do we get a handful of folks with x‐licenses to be able to prescribe? With the amount of work and paperwork and administrative time it would take to do that? No, we've got bigger fish to fry from that perspective.” Another interviewee stated, ”If there was money in this, this wouldn't be an issue.”

3.3. Barrier 3: Referral incoordination

Interviewees emphasized that referral incoordination is still a huge barrier to the integration of ED‐initiated buprenorphine and outpatient linkages to care into the current healthcare system. In order to ensure a safe transition of care for ED‐initiated buprenorphine patients, ED interviewees highlighted the need for a low‐barrier clinic that would take any patient regardless of their insurance status or social circumstance. One explained, “We spent a lot of time trying to find what I call the silver bullet, the perfect referral option, a place that I could actually do a registration and book someone in.”

Emergency physicians are available always to serve the most socially complicated patients in a chaotic and busy environment. For that reason, they advocated for assistance with care coordination outside normal business hours and streamlined throughput that would not add additional work to their already busy practices. An emergency physician clarified, “So at 2 in the morning, what do you do? How do I easily hand that patient off, so they can go get seen at 9 without waking up the clinic doc. There's not that easy transition.” Another stressed, “For it to work smoothly, it shouldn't be the physician that's doing all these phone calls and shopping the patient around.” One emergency physician offered a solution, explaining, “It would be good if I know how to send someone to someplace. If there was one phone number that I call, and they say, ‘There's [an opening] here and [an opening] there.’” These interviewees argue that streamlining referrals and follow‐up to low barrier outpatient providers through a centralized agency available 24/7 by phone would not only improve outpatient linkage to care but also increase emergency physician acceptance of the process.

Importantly, outpatient providers preferred to receive ED documentation regarding referred patients, but they do not currently have a consistent way to access this information. One clinician explained, “The thing that's needed in order to put somebody on buprenorphine or methadone is a diagnosis of opioid use disorder, and so any information gathered in the emergency room that will support that diagnosis will make it easier for the providers seeing the person here.” Instead, many have encountered patients instructed by the EDs to show up unannounced at their clinics with only an informational handout in their possession. An outpatient physician suggested, “I think it would be nice if there was a system in place where the ERs would send us the chart notes, especially since we're on a different [electronic health record, EHR], but that does not exist currently.” Emergency and outpatient providers must be able to openly communicate across differing healthcare systems, EHRs, and clinical hours in order to transition these patients into long‐term care.

3.4. Barrier 4: Loss to follow‐up

Given the complexity of their lives and social circumstances, patients with OUD often are lost to follow‐up. Participants emphasize that many patients have difficulty “connecting” to clinics because of transportation difficulties, inadequate insurance, and unstable housing despite low‐barrier access and walk‐in appointments. One outpatient provider explained, “Even if it's a next day walk‐in appointment, sadly a lot of folks just can't make it, which is understandable because there's just so much happening in the lives of those folks. So, we really do need to solve that connecting part.” Another listed the multiple factors that contribute to high no show rates, saying, “Insurance is always a huge issue. And then the other issues that come up are … It's all the usual issues. Like, people don't know where they're going to be living. They were staying with an aunt … but they want to move to somewhere else. Or they just got out of a custody situation and they're maybe staying work‐release for 3 months, but it might be 6 months.” Similarly, an emergency physician explained, “I can give someone an 800 number and that makes it very easy, but it doesn't make them do it. Same way that I can set up an appointment, but it doesn't actually get them to the appointment.”

Interviewees also report that the no‐show rate for patients with OUD is administratively incompatible with workflow and, for some clinics, economically unsustainable. An outpatient provider emphasized, “Because one of the challenges for primary care when [medications for OUD are prescribed] is that a lot of the patients don't show up or are like 2 hours late. In a primary care setting, that's very difficult to manage because schedules are full and providers are very busy.” Another expressed his concern, explaining, “It is already very unpredictable, with the no show rate on average 50%. But it's not like it's 50% every day. It's sometimes 80% no show, sometimes 10% no show. And those days, you're pulling your hair out, and frankly it becomes a little bit unsafe sometimes for patients because you're missing things and patients are waiting an hour and a half to be seen. It's really kind of ugly.”

3.5. Limitations

The objective of this study is to describe emergency and outpatient providers’ perception of local barriers to transitions of care for ED‐initiated buprenorphine patients in King County, Washington. However, the results may only represent the geographic location of the study population. Opioids have an important history in Washington. In order to combat the rising opioid death rate, the state has quickly adopted a number of public health reforms, including the Emergency Department Information Exchange (EDIE), 21 ED opioid‐prescribing guidelines, 22 legislation promoting access to naloxone, and increased access to low‐barrier buprenorphine. 23 Future research should examine the generalizability of these study findings in other areas of the country, particularly those impacted by the opioid epidemic but not as well‐resourced as King County. Participants in this qualitative study were also identified as leaders in their respective institutions’ efforts to improve the care of patients with OUD and may not reflect the views of their co‐workers. Additionally, the interview guide was guided by CFIR 20 and developed with input from emergency physicians and public health experts but was not pilot‐tested prior to use, which could have limited the specificity of the initial interviews. Lastly, understanding the patient perspective is critical to the successful implementation of an ED‐initiated buprenorphine program and transition of care for patients with OUD, but conducting patient interviews was outside the purview of this study.

4. DISCUSSION

The 4 major barriers to transitions of care for ED‐initiated buprenorphine patients from the perspective of both emergency physicians and outpatient providers are scope of practice, prescribing capacity, referral incoordination, and loss to follow‐up. OUD is a major public health problem, with ED visits for suspected overdose increasing by 30% from 2016 to 2017. 1 , 2 Buprenorphine and other MOUD decrease mortality, 7 increase retention in treatment, and reduce illicit opioid use, but are often not prescribed in the ED. 3 , 24 These obstacles are significant but surmountable with an investment in protocols, education, communication, and support services.

First, interviewees hoped to combat the perceptions around the limited scope of practice to treat OUD in EDs by creating a protocolized “standard of care.” Protocols for ED‐initiated buprenorphine have also been found to streamline care 4 within the ED without increasing ED visits for substance use treatment. 25 Regional standards around OUD treatment and referral may boost mission‐driven practice, gain patient trust, address outpatient providers’ skepticism, and reduce treatment disparities.

Second, interviewees wished to promote prescribing capacity through the elimination of the x‐waiver and expanding addiction education. Many agreed with the literature that reimbursing providers for time spent in training would incentivize x‐waiver enrollment, 26 and most argued for the elimination of the x‐waiver. However, 1 study found that the rate of ED‐initiated buprenorphine only increased when waivered providers also received a clinical decision support system and just‐in‐time training. 27 Recently trained ED providers are also more likely to believe OUD is similar to other chronic diseases and approve of ED‐initiated buprenorphine, highlighting the importance of education in expanding prescribing capacity. 6

Third, interviewees argued that transitions of care for patients with OUD should mirror other ED referrals for high‐risk conditions with many suggesting the establishment of a central agency to streamline communication. Because the ED specializes in the identification, acute treatment, and linkage to ongoing care for time‐sensitive conditions, there is ongoing work to establish a quality framework for ED management of OUD that mirrors the current processes for acute myocardial infarction, stroke, sepsis, and trauma. 28 ED providers in our study described no standardized, coordinated way to refer patients with OUD to outpatient clinics, particularly outside normal business hours, while outpatient providers expressed concern about the lack of communication and documentation from the ED regarding referred patients. Many recommended leveraging the EHR to improve care coordination and expanding the mandate of the already established Washington Recovery Helpline, a 24/7 information and referral resource that does not yet have the capacity to schedule appointments. Previous work has leveraged the EHR to provide computerized clinical decision support systems, which have improved rates of buprenorphine prescribing in the ED for patients with untreated OUD. 27 Additionally, patient privacy regulations surrounding health information, including patient records for the treatment of substance use disorders as guided by the 42 CFR Part 2 regulations, have recently been revised to facilitate coordination of care. 29 Streamlining referrals and follow‐up to low‐barrier outpatient providers through a centralized agency or with improved interoperability of the EHR would not only improve outpatient linkage to care but also increase emergency physician acceptance of the process.

Fourth, interviewees hope to use low‐barrier scheduling and navigation services to encourage retention of patients in outpatient treatment. Emergency physicians described frustration with the inability to successfully connect patients to ongoing care, while outpatient providers hoped that multidisciplinary care coordination with nurse managers, counselors, peer navigators, and social workers would combat high no‐show rates and increase retention in treatment. The recent implementation of an ED‐initiated buprenorphine program with a warm handoff to community providers facilitated by social work in a Colorado hospital was successful, with 61% of initiated patients presenting to their initial outpatient intake appointment and 39% remaining engaged in treatment after 30 days. 30 Low‐barrier scheduling and improved navigation services would not only combat the devastating effects of loss to follow‐up on outpatient clinics but also tremendously improve the transitions of care for ED‐initiated buprenorphine patients.

There are a number of barriers to translating evidence‐based practice around the transitions of care of ED‐initiated buprenorphine patients to a community setting. Next steps for implementation of this intervention include establishing regional protocols, increasing prescriber capacity, creating a central repository for streamlined referrals and follow‐up, and using low‐barrier scheduling and navigation services.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

CEF, HCD, BF, SCM, and LKW contributed to the research design and implementation, data analysis, and manuscript writing.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Biography

Callan Fockele, MD, MS, is an Acting Instructor of the Department of Emergency Medicine and Fellow of the Population Health Research Fellowship at the University of Washington in Seattle, Washington.

Appendix 1.

CFIR Guide: ED Key Stakeholders

Introduction

-

We would also like to get to know you before diving into the interview.

-

○

Tell me a little bit about your role in your organization.

-

○

Tension for Change: Tell me about the last memorable patient you treated with opioid use disorder in your ED (e.g., the last patient who overdosed on heroin or who was suffering from the sequelae of injection drug use).

-

■

Did you feel like you could appropriately treat this patient's addiction?

-

■

Did you dispense or prescribe naloxone or buprenorphine? If so, what was the process like?

-

■

Did you provide any outpatient referrals?

-

■

Was the patient asking for or willing to accept treatment and/or referral?

-

■

-

○

Intervention/Inner Setting

-

Who are the influential stakeholders (e.g., administrators, board members, pharmacists, nurses, and co‐workers) at your organization?

-

○

Formally Appointed Internal Implementation Leaders: Who will lead implementation of the intervention?

-

○

Champions: Are there people in your organization who are likely to partner/support or champion (go above and beyond what might be expected) the intervention?

-

○

-

Evidence Strength & Quality: What do these people at your organization think of this intervention?

-

○

Who else in your organization needs to support this intervention in order for it to be successful? How can they be brought on board?

-

○

-

Complexity: What concerns do you have about dispensing or prescribing buprenorphine from the ED?

-

○

Would this intervention be easy (or complicated) to start? Why or why not?

-

○

Compatibility: How well does the intervention fit with existing work processes and practices in your setting?

-

○

Culture: How do you think your organization's culture (general beliefs, values, assumptions that people embrace) will affect the implementation of the intervention?

-

○

Self‐efficacy: How confident do you think your colleagues feel about implementing the intervention and what gives them that level of confidence (or lack of confidence)? What would help build confidence?

-

○

Access to Knowledge & Information: What resources would need to be in place for you to feel comfortable dispensing or prescribing buprenorphine?

-

○

Outer Setting/Process

-

How well do you think the intervention will meet the needs of the individuals served by your organization?

-

○

Patient Needs & Resources: What barriers will patients face in participating in the intervention?

-

○

-

Intervention Participants: Do you currently have a primary referral site for patients requesting medications for opioid use disorder? How do you see that being coordinated?

-

○

How do you currently (or how will you in the future) communicate to the outpatient providers at rapid access buprenorphine clinics about patient referrals?

-

○

-

What are the next steps in implementing this intervention at your hospital?

-

○

How do you foresee the King County Learning Collaborative streamline this process for you? Are there formal materials that would be useful to you? How you would like these materials distributed (paper, email, website, in‐person education)?

-

○

Provide examples of the ED Bridge and Yale SBIRT referral forms

-

○

Reflecting & Evaluating: What kind of information do you plan to collect as you implement the intervention?

Appendix 2.

CFIR Guide: Outpatient Key Stakeholders

Introduction

-

First, we would also like to get to know you.

-

○

Tell me a little bit about your role in the clinic.

-

○

What is your clinic's mission?

-

○

Who else works at your clinic (pharmacist, SW, CDP, bup prescribers)?

-

○

Describe the patients you see (how many are on MOUD).

-

○

Describe your EMR and its functionality specific to information exchange (EDIE, PMP, care everywhere)

-

○

How are patients referred to your clinic? What is the preferred way to receive a referral? (internal from same organization? ED referrals?)

Intervention Characteristics → Design Quality & Packaging

What constitutes a warm‐handoff (for any condition) from the ED?

-

What concerns do you have about caring for referred patients who have been initiated on buprenorphine from the ED?

-

○

Prompt: Some providers have expressed concerns about appropriate diagnosis of OUD or unrealistic expectations around care of other comorbidities. Does this seem like something you or your colleagues might be concerned about?

-

○

Some patients with OUD might be referred from the ED without starting meds. Can you describe your protocol for buprenorphine initiation at your site? Home induction/self‐start?

-

Describe the critical information (demographic information, drug usage, or laboratory testing) you need to receive about referred patients to your clinic for buprenorphine.

-

○

How would your clinic prefer to receive this information?

-

○

-

Do you have the capacity to see patients within 24‐72 hours of being seen in the ED?

-

○

If yes – what is the process for getting urgent/emergent appointments?

-

○

Does your clinic see walk‐in patients? Does your clinic have hours on the weekends?

-

○

-

How should emergency providers prepare patients being referred to your clinic/site for their first visit? Is there anything specific patients should know?

-

○

Prompt: Substance use prior to visit, insurance, wait time estimate, other site‐specific medical/social concerns.

-

○

Outer Setting

How well do you think the intervention (i.e., the warm handoff between patients initiated on buprenorphine in the ED to your clinic) meets the needs of your organization?

What information would you like to share with the King County Learning Collaborative about your clinic as it relates to ED‐initiated buprenorphine?

What role would you like the King County Learning Collaborative to have in providing information exchange and/or other help in implementing this intervention?

Inner Setting → Readiness for Implementation

What are the barriers to accepting ED‐referred patients?

-

What kind of support and/or barriers can you expect from leaders in your organization?

-

○

What kind of supporting evidence or proof is need about the effectiveness of this intervention to get staff on board?

-

○

Do you expect to have sufficient resources to implement and administer the intervention?

What kinds of information and materials (e.g., copies of materials like emails and brochures, personal contact, and internal information sharing like staff meetings) about the intervention are planned for individuals in your setting?

Process → Reflecting & Evaluating

What kind of information do you plan to collect as you implement the intervention?

Do you think it would be possible to give feedback to ED providers for QI purposes? How would this process occur at your organization?

Fockele CE, Duber HC, Finegood B, Morse SC, Whiteside LK. Improving transitions of care for patients initiated on buprenorphine for opioid use disorder from the emergency departments in King County, Washington. JACEP Open. 2021;2:e12408. 10.1002/emp2.12408

Supervising Editor: Karl A. Sporer, MD

REFERENCES

- 1. Vivolo‐Kantor AM, Seth P, Gladden RM, et al. Vital signs: trends in emergency department visits for suspected opioid overdoses ‐ United States, July 2016‐September 2017. MMWR Morb Mort Wkly Rep. 2018;67(9):279‐285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Seth P, Scholl L, Rudd RA, et al. Overdose deaths involving opioids, cocaine, and psychostimulants ‐ United States, 2015–2016. MMWR Morb Mort Wkly Rep. 2018;67(12):349‐358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. D'Onofrio G, O'Connor PG, Pantalon MV, et al. Emergency department‐initiated Buprenorphine/naloxone treatment for opioid dependence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313(16):1636‐1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hawk KF, D'Onofrio G, Chawarski MC, et al. Barriers and facilitators to clinician readiness to provide emergency department‐initiated Buprenorphine. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(5):e204561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lowenstein M, Kilaru A, Perrone J, et al. Barriers and facilitators for emergency department Initiation of Buprenorphine: a physician survey. Am J Emerg Med. 2019;37(9):1787‐1790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Im DD, Chary A, Condella AL, et al. Emergency department clinicians' attitudes toward opioid use disorder and emergency department‐initiated Buprenorphine treatment: a Mixed‐Methods Study. West J Emerge Med. 2020;21(2):261‐271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Larochelle MR, Bernson D, Land T, et al. Medication for opioid use disorder after nonfatal opioid overdose and association with mortality: a Cohort Study. Ann Int Med. 2018;169(3):137‐145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lo‐Ciganic WH, Gellad WF, Gordon AJ, et al. Association between trajectories of buprenorphine treatment and emergency department and in‐patient utilization. Addiction. 2016;111(5):892‐902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schwartz RP, Gryczynski J, O'Grady KE, et al. Opioid agonist treatments and heroin overdose deaths in Baltimore, Maryland, 1995–2009. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(5):917‐922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wakeman SE, Larochelle MR, Ameli O, et al. Comparative effectiveness of different treatment pathways for opioid use disorder. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(2):e1920622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Crotty K, Freedman KI, Kampman KM. Executive summary of the focused update of the ASAM National Practice Guideline for the treatment of opioid use disorder. J Addict Med. 2020;14(2):99‐112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Duber HC, Barata IA, Cioe‐Pena E, et al. Identification, management, and transition of care for patients with opioid use disorder in the emergency department. Ann Emerge Med. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yedinak JL, Goedel WC, Paull K, et al. Defining a recovery‐oriented cascade of care for opioid use disorder: a community‐driven, statewide cross‐sectional assessment. PLoS Med. 2019;16(11):e1002963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, et al. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277‐1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32‐item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349‐357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lyon AR, Munson SA, Renn BN, et al. Use of human‐centered design to improve implementation of evidence‐based psychotherapies in low‐resource communities: protocol for studies applying a framework to assess usability. JMIR Res Protoc. 2019;8(10):e14990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ranney ML, Meisel ZF, Choo EK, et al. Interview‐Based qualitative research in emergency care part II: data collection, analysis and results reporting. Acad Emerge Med. 2015;22(9):1103‐1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Braun V, Clarke V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual Res Sport, Exerc Health. 2019;11(4). [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cfirguideorg. 2020, 2020.

- 21. Gore L, The American College of Emergency Physicians (A.C.E.P.) Exclusively Endorses Edie (A.K.A. Premanage Ed) Solution from Collective Medical Techonologies. 2017; http://newsroom.acep.org/news_releases?item=122817. Accessed June 25, 2018.

- 22. Neven DE, Sabel JC, Howell DN, et al. The development of the Washington state emergency department opioid prescribing guidelines. J Med Toxicol. 2012;8(4):353‐359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hood JE, Banta‐Green CJ, Duchin JS, et al. Engaging an unstably housed population with low‐barrier Buprenorphine treatment at a syringe services program: lessons learned from Seattle, Washington. Substance Abuse. 2019:1‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. D'Onofrio G, Chawarski MC, O'Connor PG, et al. Emergency department‐initiated buprenorphine for opioid dependence with continuation in primary care: outcomes during and after intervention. J Gen Int Med. 2017;32(6):660‐666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jennings LK, Bogan C, McCauley JJ, et al. Rates of substance use disorder treatment seeking visits after emergency department‐initiated Buprenorphine. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;38(5):975‐978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Foster SD, Lee K, Edwards C, et al. Providing incentive for emergency physician X‐waiver training: an evaluation of program success and postintervention buprenorphine prescribing. Ann Emerg Med. 2020;76(2):206‐214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Holland WC, Nath B, Li F, et al. Interrupted time series of user‐centered clinical decision support implementation for emergency department‐initiated Buprenorphine for opioid use disorder. Acad Emerg Med. 2020;27(8):753‐763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Samuels EA, D'Onofrio G, Huntley K, et al. A quality framework for emergency department treatment of opioid use disorder. Ann Emerge Med. 2019;73(3):237‐247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fact Sheet: SAMHSA 42 CFR Part 2 Revised Rule [press release]. 2020.

- 30. Kelly T, Hoppe JA, Zuckerman M, et al. A novel social work approach to emergency department Buprenorphine induction and warm hand‐off to community providers. Am J Emerge Medi. 2020;38(6):1286‐1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]