Abstract

Purpose

Chemotherapy and multi-targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) are important treatments for advanced soft tissue sarcomas, but the following treatment remains unclear after the failure of these drugs. This retrospective study investigated the efficacy and safety of multi-targeted TKI rechallenge in patients with advanced soft tissue sarcoma after the failure of previous TKI treatment.

Patients and Methods

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans and anaplastic lymphoma kinase translocation-positive inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor were excluded. Eligible patients included those diagnosed with advanced soft tissue sarcoma, progressed after the initial TKI treatment, and received the same or other TKI therapies. Treatment response, adverse events, median progression-free survival and overall survival were analyzed.

Results

Twenty-six eligible patients were included. Nineteen patients had previously received chemotherapy, and all patients had received at least 1.5 months of initial TKI treatment. During the TKI rechallenge, patients were treated with anlotinib (n =16), lenvatinib (n =3), apatinib (n =2), pazopanib (n =2), axitinib (n =2) or regorafenib (n =1). No patients achieved responses. Nine (34.6%) patients had stable disease confirmed by a second imaging scan, and 5 (19.2%) patients had stable disease that was not confirmed by a second scan. The estimated median progression-free survival and overall survival were 3.3 months and 11.7 months, respectively. Grade 3/4 adverse events occurred in 6 (23.1%) patients and were manageable.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that multi-targeted TKI rechallenge may provide potential clinical benefits for patients with advanced soft tissue sarcoma after their previous TKI treatment.

Keywords: soft tissue sarcoma, unresectable, metastatic, chemotherapy, tyrosine kinase inhibitor, rechallenge

Introduction

Soft tissue sarcomas (STS) are a group of rare malignant tumors with diverse and heterogeneous pathological features. Among patients with advanced STS, highly selective and effective tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) are available for a few histological subtypes, such as imatinib for gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans,1,2 and crizotinib for inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor with anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) translocation.3 For most advanced STS with non-specific pathological subtypes, doxorubicin-based chemotherapy has been the standard first-line treatment for decades.4,5 Following doxorubicin-based chemotherapy, treatment strategy also depends on pathological diagnosis: eribulin for liposarcoma,6 trabectedin for liposarcoma and leiomyosarcoma,7 gemcitabine-containing treatment for leiomyosarcoma,8 paclitaxel for angiosarcoma,9,10 and pembrolizumab for undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma,11 etc. Pazopanib and regorafenib are multi-targeted TKIs with activities against angiogenic signaling pathway (vascular endothelial growth factor receptor [VEGFR]) and against tumor cell kinases (eg, platelet-derived growth factor receptors [PDGFR], c-Kit and Ret), which could improve progression-free survival (PFS) in patients with non-adipocytic STS after the failure of standard chemotherapy.12,13 Anlotinib, a novel multi-targeted TKI, also has promising antitumor activity against refractory STS, including liposarcoma.14 However, treatment after the failure of these drugs remains unclear.

Recently, a placebo-controlled Phase II study showed that regorafenib prolonged the median PFS (2.1 vs 1.1 months, P =0.0007) in patients with non-adipocytic STS after both chemotherapy and pazopanib.15 Although the difference in PFS was statistically significant, the median PFS with regorafenib did not reach the expected PFS (3.6 months), and the improvement in median PFS appeared a little disappointing.15 Therefore, it is needed to carry out further study of rechallenge with multi-targeted TKI. This retrospective study summarized a single-center experience of the multi-targeted TKI rechallenge in patients with advanced STS after the failure of previous TKI treatment.

Patients and Methods

Study Design

This was a single-center retrospective study with the aim of investigating the efficacy and safety of the TKI rechallenge in patients diagnosed with unresectable or metastatic STS between February 2016 and March 2020. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee on Biomedical Research, West China Hospital of Sichuan University (reference number: 2020–627).

Patient Population and Data Collection

Eligible patients included those diagnosed with STS, had unresectable or metastatic lesions, progressed after the initial TKI treatment, and received the same or other TKI therapy. Most STS subtypes, including rhabdomyosarcoma and extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma, were allowed. Dedifferentiated chordoma was also allowed, because it was commonly managed as an STS. Meanwhile, GIST, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans and ALK-positive inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor were excluded.

Clinical Outcomes

Treatment response and toxicity were evaluated according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (version 1.1) and the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 5.0), respectively. The interval of imaging scans was 6–9 weeks. The duration of stable disease should be at least 6 weeks. Clinical benefit rate was defined as the total percentage of complete response, partial response and stable disease confirmed by the second imaging scan.16 PFS was defined as the time interval from the beginning of TKI treatment to either disease progression or death of the patient as a result of any cause. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from the beginning of TKI treatment to death of the patient as a result of any cause.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are reported as the median and range. Categorical variables are presented in frequency counts and percentages. PFS and OS were estimated by using the Kaplan–Meier method, and survival curves were compared using the Log rank test. All data analyses were conducted using SPSS 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY), and a two-sided P < 0.05 was considered a statistically significant difference.

Results

Patient Characteristics

In total, 26 eligible patients were included in this study. The median age was 34 (range, 14–63) years, and 17 (65.4%) patients were male. The most common pathological subtypes were synovial sarcoma (n = 4, 15.4%), leiomyosarcoma (n = 4, 15.4%), extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma (n = 3, 11.5%), alveolar soft-part sarcoma (n = 3, 11.5%) and clear cell sarcoma (n = 2, 7.7%). Twenty-one (80.8%) patients had metastatic lesions. Before the TKI rechallenge, 19 (73.1%) patients had received at least one regimen of chemotherapy. Among the seven patients without chemotherapy history, two patients had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status score of 2–3, 3 patients were diagnosed with alveolar soft-part sarcoma, one with clear cell sarcoma, and one with aggressive fibromatosis. At the time of the data cutoff date (December 20, 2020), 13 (50.0%) patients died. The median follow-up time was 26.9 months (range, 9.0–51.2 months), and no patients were lost to follow-up. Patient characteristics are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Characteristics | No. of Patients (n) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 17 | 65.4 |

| Female | 9 | 34.6 |

| Age (years) | ||

| Median | 34 | |

| Range | 14–63 | |

| ECOG performance status | ||

| 0–1 | 18 | 69.2 |

| 2–3 | 8 | 30.8 |

| Pathological type | ||

| Synovial sarcoma | 4 | 15.4 |

| Leiomyosarcoma | 4 | 15.4 |

| Extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma | 3 | 11.5 |

| Alveolar soft-part sarcoma | 3 | 11.5 |

| Clear cell sarcoma | 2 | 7.7 |

| Desmoplastic small round cell tumor | 1 | 3.8 |

| Pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma | 1 | 3.8 |

| Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma | 1 | 3.8 |

| Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor | 1 | 3.8 |

| ALK-negative inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor | 1 | 3.8 |

| Solitary fibrous tumor, malignant | 1 | 3.8 |

| Dedifferentiated chordoma | 1 | 3.8 |

| Angiosarcoma | 1 | 3.8 |

| Aggressive fibromatosis | 1 | 3.8 |

| Undifferentiated sarcoma | 1 | 3.8 |

| Metastatic disease | ||

| Yes | 21 | 80.8 |

| No | 5 | 19.2 |

| Surgery history | ||

| Yes | 21 | 80.8 |

| No | 5 | 19.2 |

| Radiotherapy history | ||

| Yes | 10 | 38.5 |

| No | 16 | 61.5 |

| No. of previous chemotherapy regimens | ||

| 0 | 7 | 26.9 |

| 1 | 9 | 34.6 |

| 2 | 7 | 26.9 |

| ≥3 | 3 | 11.5 |

| Immunotherapy history | ||

| Yes | 7 | 26.9 |

| No | 19 | 73.1 |

Abbreviations: ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase translocation; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

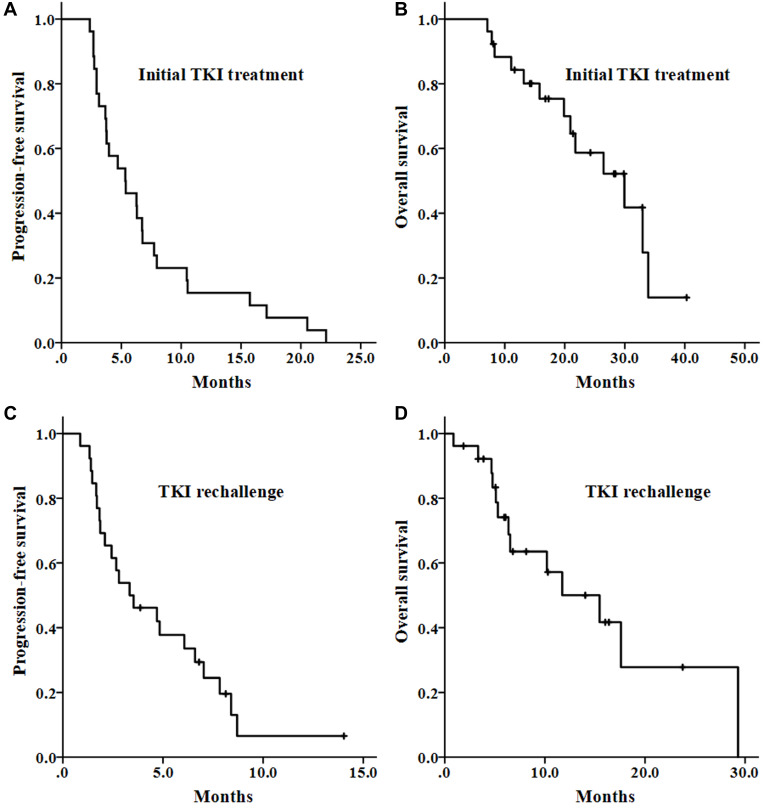

Efficacy of Initial TKI Treatment

All patients received at least 1.5 months of initial TKI treatment. Anlotinib was used in 14 (53.8%) patients, apatinib in 7 (26.9%) patients, pazopanib in 4 (15.4%) patients, and lenvatinib in 1 (3.8%) patient. No patients achieved a complete response. Partial responses occurred in one anlotinib-treated patient with alveolar soft-part sarcoma, one anlotinib-treated clear cell sarcoma and one apatinib-treated synovial sarcoma, and 11 patients had stable disease confirmed by a second imaging scan, so the clinical benefit rate was 53.8%. In addition, 7 (26.9%) patients had stable disease that could not be confirmed by a second scan. From the beginning of initial TKI treatment, the estimated median PFS (Figure 1A) and OS (Figure 1B) were 5.3 months and 29.9 months, respectively. Patients treated with anlotinib or other TKIs had similar median PFS (4.7 vs 5.3 months, P = 0.916) and OS (26.5 vs 29.9 months, P = 0.693). The reasons for discontinuing initial TKI treatment were as follows: disease progression (n =17, 65.4%), adverse events (n =2, 7.7%), palliative surgery (n =1, 3.8%) and personal reasons (n =4, 15.4%). Two (7.7%) patients did not discontinue TKI after disease progression, but received the same TKI therapy in combination with radiotherapy or immunotherapy.

Figure 1.

Survival curves of patients with unresectable or metastatic soft tissue sarcoma. (A and B) The progression-free survival and overall survival with the initial TKI treatment. (C and D) The progression-free survival and overall survival with the TKI rechallenge. TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Efficacy of the TKI Rechallenge

The median time interval between initial TKI treatment and TKI rechallenge was 0.9 (range, 0.1–21.0) months. Eight (30.8%) patients received systemic treatment between TKIs. The drugs used during the TKI rechallenge were anlotinib (n =16, 61.5%), lenvatinib (n =3, 11.5%), apatinib (n =2, 7.7%), pazopanib (n =2, 7.7%), axitinib (n =2, 7.7%) and regorafenib (n =1, 3.8%). Due to life-threatening lesions (symptomatic intracranial metastasis or cervical spinal cord compression) and specific subtypes (such as clear cell sarcoma, alveolar soft-part sarcoma, and multi-line treated extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma and rhabdomyosarcoma), 9 (34.6%) patients received TKI treatment in combination with other antitumor therapies, including immune checkpoint inhibitors (n =5), chemotherapy (n =2), radiotherapy (n =1), and immune checkpoint inhibitor + chemotherapy + radiotherapy (n =1).

No patients achieved a complete response or a partial response. Nine patients had stable disease that was confirmed by a second scan, with a clinical benefit rate of 34.6%. In addition, 5 (19.2%) patients had stable disease that could not be confirmed by a second scan. From the beginning of the TKI rechallenge, the estimated median PFS (Figure 1C) and OS (Figure 1D) were 3.3 months and 11.7 months, respectively. The median PFS was statistically similar irrespective of therapy: TKI monotherapy (3.5 months), combination treatment (3.3 months), anlotinib (4.7 months) or other TKIs (1.9 months). In seven patients who discontinued the initial TKI treatment due to non-progression reasons, the median PFS was 8.4 months, and the median OS was not reached. Achieving stable disease was the only factor associated with longer median PFS, while achieving stable disease and ECOG performance status score of 0–1 were associated with longer median OS.

Grade 3/4 Adverse Events During the TKI Rechallenge

Grade 3/4 adverse events occurred in 6 (23.1%) patients, including hypertension (n =4, 15.4%), anemia (n =1, 3.8%), anorexia (n =1, 3.8%), weight reduction (n =1, 3.8%) and intracranial hemorrhage (n =1, 3.8%). The patient who developed grade 3–4 hypertension and intracranial hemorrhage discontinued the TKI rechallenge, and was well supported by symptomatic management. Unfortunately, she died as a result of disease progression from pulmonary and intracranial metastases.

Discussion

In this study, we found that after the failure of initial TKI treatment, a third (34.6%) of patients with advanced STS could still achieve clinical benefit from the treatment with the same or different TKIs, with a median PFS of 3.3 months and a median OS of 11.7 months.

Pazopanib and regorafenib have been proved to improve PFS in patients with metastatic non-adipocytic STS who were previously treated with standard chemotherapy, with a median PFS of 4.0–4.6 months and a median OS of 12.5–13.4 months.12,13 Anlotinib has been newly approved for the treatment of patients with refractory advanced STS in China, with a median PFS of 5.6 months and a median OS of 12.0 months.14 In this study, we confirmed the clinical benefit of multi-targeted TKI treatment in advanced STS (Figure 1A and B). The 5.3-month median PFS with the initial TKI treatment was consistent with the reported data in the aforementioned studies. However, the median OS of 29.9 months seemed to be longer. One possible reason is that patients included in this study to have TKI rechallenge were those who might have relatively good prognosis.

The clinical benefit from the TKI rechallenge was discovered early in patients with advanced GIST after failure of imatinib, who could receive treatment with sunitinib and subsequently with regorafenib.17,18 Previous studies also provided a glimpse of antitumor activity with the TKI rechallenge in non-GIST sarcomas, in which although partial patients were naive from TKI, patients pretreated with TKI were also included.19–21 Recently, a placebo-controlled phase II trial showed that regorafenib improved the median PFS (2.1 vs 1.1 months, P =0.0007) in patients with non-adipocytic and non-GIST STS who were previously treated with both chemotherapy and pazopanib.15 This result suggests that rechallenge with TKI may display clinical values in advanced STS. Beyond pazopanib and regorafenib, more multi-targeted TKIs are available in clinical practices. In our study, initial TKI treatment included anlotinib, apatinib, pazopanib and lenvatinib. Rechallenged TKIs included anlotinib, lenvatinib, apatinib, pazopanib, axitinib and regorafenib, and yielded a median PFS of 3.3 months (Figure 1C) and a median OS of 11.7 months (Figure 1D). A third (34.6%) of patients achieved clinical benefits, with second-scan confirmed stable disease. This finding from the complex clinical practices further suggests that rechallenge with TKI may provide potential clinical value to the management of refractory advanced non-GIST STS.

The antitumor activity of the TKI rechallenge is not well known. One possible reason is that there are differences in targets and affinities of multi-targeted TKIs: pazopanib has high affinities with VEGFR1 (half inhibitory concentration of kinase phosphorylation assay: 10 nM) and VEGFR2 (30 nM)22; regorafenib with Ret (1.5 nM), Raf-1 (2.5 nM), VEGFR2 (4.2 nM) and c-Kit (7 nM)23; apatinib with VEGFR2 (1 nM) and Ret (13 nM)24; axitinib with VEGFR1 (0.1 nM), VEGFR2 (0.2 nM) and VEGFR3 (0.1–0.3 nM)25; lenvatinib with VEGFR3 (0.71 nM), VEGFR2 (0.74 nM), VEGFR1 (1.3 nM), Ret (1.5 nM) and fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2, 8.2 nM)26; and anlotinib with VEGFR2 (0.2 nM) and VEGFR3 (0.7 nM).27 Of them, axitinib, lenvatinib and anlotinib can inhibit VEGFR2 kinase at the sub-nanomolar concentrations. Another explanation is that this study included 7 (26.9%) patients who discontinued initial TKI treatment due to adverse events, palliative surgery or personal reasons. Of them, the 8.4-month median PFS with TKI rechallenge was encouraging although there was no significant difference because of a small sample size. It was consistent with the findings in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma, who discontinued previous TKI treatment due to non-progression reasons and could achieve a clinical benefit from the rechallenge with TKI following disease progression, with a disease control rate of 70–100%.28–30

The authors acknowledge several limitations. Firstly, there was selection bias in this single-institution study related to its retrospective nature. Secondly, the study population existed heterogeneity in many respects (Table 1). Some subtypes such as aggressive fibromatosis, rhabdomyosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma and alveolar soft-part sarcoma are clearly different from other non-specific subtypes in treatment paradigms. Patients were not uniformly treated upfront or at the TKI rechallenge—some received combination therapy and others not, and they utilized different types of TKIs. Furthermore, the advantage population of the TKI rechallenge and the optimal sequence of multi-targeted TKI treatment were unclear because of the small sample size.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that after the failure of prior TKI treatment, there may be some clinical benefits for patients with advanced soft tissue sarcoma by the same or different TKI rechallenge if feasible and safe. However, more data are needed to confirm this finding and to explore a potential treatment sequence of multi-targeted TKIs.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all participants and their families in this study.

Funding Statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or nonprofit sectors.

Data Sharing Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the policy of the institution.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee on Biomedical Research, West China Hospital of Sichuan University. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments. Formal consent to participate was waived by the ethics committee due to the retrospective nature. Clinical data were collected by reviewing medical records. All data were anonymized and maintained with confidentiality in an encrypted and independent storage device. All identifiable information has been removed from the study reports.

Disclosure

All authors declare that no conflicts of interest exist in this study.

References

- 1.Demetri GD, von Mehren M, Blanke CD, et al. Efficacy and safety of imatinib mesylate in advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(7):472–480. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rutkowski P, Van Glabbeke M, Rankin CJ, et al. Imatinib mesylate in advanced dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: pooled analysis of two phase II clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(10):1772–1779. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.7899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Butrynski JE, D’Adamo DR, Hornick JL, et al. Crizotinib in ALK-rearranged inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(18):1727–1733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1007056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elias A, Ryan L, Sulkes A, Collins J, Aisner J, Antman KH. Response to mesna, doxorubicin, ifosfamide, and dacarbazine in 108 patients with metastatic or unresectable sarcoma and no prior chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7(9):1208–1216. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1989.7.9.1208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Judson I, Verweij J, Gelderblom H, et al. Doxorubicin alone versus intensified doxorubicin plus ifosfamide for first-line treatment of advanced or metastatic soft-tissue sarcoma: a randomised controlled Phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(4):415–423. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70063-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schöffski P, Chawla S, Maki RG, et al. Eribulin versus dacarbazine in previously treated patients with advanced liposarcoma or leiomyosarcoma: a randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10028):1629–1637. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01283-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Demetri GD, von Mehren M, Jones RL, et al. Efficacy and safety of trabectedin or dacarbazine for metastatic liposarcoma or leiomyosarcoma after failure of conventional chemotherapy: results of a phase III randomized multicenter clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(8):786–793. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.4734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hensley ML, Maki R, Venkatraman E, et al. Gemcitabine and docetaxel in patients with unresectable leiomyosarcoma: results of a phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(12):2824–2831. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.11.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Penel N, Bui BN, Bay JO, et al. Phase II trial of weekly paclitaxel for unresectable angiosarcoma: the ANGIOTAX study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(32):5269–5274. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.3146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schlemmer M, Reichardt P, Verweij J, et al. Paclitaxel in patients with advanced angiosarcomas of soft tissue: a retrospective study of the EORTC soft tissue and bone sarcoma group. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(16):2433–2436. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.07.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tawbi HA, Burgess M, Bolejack V, et al. Pembrolizumab in advanced soft-tissue sarcoma and bone sarcoma (SARC028): a multicentre, two-cohort, single-arm, open-label, Phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(11):1493–1501. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30624-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van der Graaf WT, Blay JY, Chawla SP, et al. Pazopanib for metastatic soft-tissue sarcoma (PALETTE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2012;379(9829):1879–1886. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60651-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mir O, Brodowicz T, Italiano A, et al. Safety and efficacy of regorafenib in patients with advanced soft tissue sarcoma (REGOSARC): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(12):1732–1742. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30507-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chi Y, Fang Z, Hong X, et al. Safety and efficacy of anlotinib, a multikinase angiogenesis inhibitor, in patients with refractory metastatic soft-tissue sarcoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(21):5233–5238. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-3766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Penel N, Mir O, Wallet J, et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled randomized phase II trial assessing the activity and safety of regorafenib in non-adipocytic sarcoma patients previously treated with both chemotherapy and pazopanib. Eur J Cancer. 2020;126:45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2019.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirbe AC, Eulo V, Moon CI, et al. A phase II study of pazopanib as front-line therapy in patients with non-resectable or metastatic soft-tissue sarcomas who are not candidates for chemotherapy. Eur J Cancer. 2020;137:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Demetri GD, van Oosterom AT, Garrett CR, et al. Efficacy and safety of sunitinib in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumour after failure of imatinib: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;368(9544):1329–1338. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69446-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Demetri GD, Reichardt P, Kang YK, et al. Efficacy and safety of regorafenib for advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumours after failure of imatinib and sunitinib (GRID): an international, multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9863):295–302. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61857-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stacchiotti S, Mir O, Le Cesne A, et al. Activity of pazopanib and trabectedin in advanced alveolar soft part sarcoma. Oncologist. 2018;23(1):62–70. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2017-0161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilky BA, Trucco MM, Subhawong TK, et al. Axitinib plus pembrolizumab in patients with advanced sarcomas including alveolar soft-part sarcoma: a single-centre, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(6):837–848. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30153-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stacchiotti S, Simeone N, Lo Vullo S, et al. Activity of axitinib in progressive advanced solitary fibrous tumour: results from an exploratory, investigator-driven phase 2 clinical study. Eur J Cancer. 2019;106:225–233. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2018.10.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumar R, Knick VB, Rudolph SK, et al. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic correlation from mouse to human with pazopanib, a multikinase angiogenesis inhibitor with potent antitumor and antiangiogenic activity. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6(7):2012–2021. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilhelm SM, Dumas J, Adnane L, et al. Regorafenib (BAY 73-4506): a new oral multikinase inhibitor of angiogenic, stromal and oncogenic receptor tyrosine kinases with potent preclinical antitumor activity. Int J Cancer. 2011;129(1):245–255. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tian S, Quan H, Xie C, et al. YN968D1 is a novel and selective inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 tyrosine kinase with potent activity in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Sci. 2011;102(7):1374–1380. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.01939.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu-Lowe DD, Zou HY, Grazzini ML, et al. Nonclinical antiangiogenesis and antitumor activities of axitinib (AG-013736), an oral, potent, and selective inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinases 1, 2, 3. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(22):7272–7283. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamamoto Y, Matsui J, Matsushima T, et al. Lenvatinib, an angiogenesis inhibitor targeting VEGFR/FGFR, shows broad antitumor activity in human tumor xenograft models associated with microvessel density and pericyte coverage. Vasc Cell. 2014;6:18. doi: 10.1186/2045-824X-6-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xie C, Wan X, Quan H, et al. Preclinical characterization of anlotinib, a highly potent and selective vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 inhibitor. Cancer Sci. 2018;109(4):1207–1219. doi: 10.1111/cas.13536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Powles T, Kayani I, Sharpe K, et al. A prospective evaluation of VEGF-targeted treatment cessation in metastatic clear cell renal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(8):2098–2103. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Albiges L, Oudard S, Negrier S, et al. Complete remission with tyrosine kinase inhibitors in renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(5):482–487. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.2516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koo DH, Park I, Ahn JH, et al. Long-term outcomes of tyrosine kinase inhibitor discontinuation in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2016;77(2):339–347. doi: 10.1007/s00280-015-2942-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]