Abstract

A host of different types of direct and indirect, primary and secondary injuries can affect different portions of the optic nerve(s). Thus, in the setting of penetrating as well as nonpenetrating head or facial trauma, a high index of suspicion should be maintained for the possibility of the presence of traumatic optic neuropathy (TON). TON is a clinical diagnosis, with imaging frequently adding clarification to the full nature/extent of the lesion(s) in question. Each pattern of injury carries its own unique prognosis and theoretical best treatment; however, the optimum management of patients with TON remains unclear. Indeed, further research is desperately needed to better understand TON. Observation, steroids, surgical measures, or a combination of these are current cornerstones of management, but statistically significant evidence supporting any particular approach for TON is absent in the literature. Nevertheless, it is likely that novel management strategies will emerge as more is understood about the converging pathways of various secondary and tertiary mechanisms of cell injury and death at play in TON. In the meantime, given our current deficiencies in knowledge regarding how to best manage TON, “primum non nocere” (first do no harm) is of utmost importance.

Keywords: optic neuropathy, trauma, traumatic optic neuropathy, steroids, optic canal decompression

Introduction

In the setting of penetrating as well as nonpenetrating head or facial trauma, a high index of suspicion should be maintained for the possibility of the presence of traumatic optic neuropathy (TON).

TON is a clinical diagnosis, with imaging frequently adding clarification to the full nature/extent of the lesion(s) in question. Each pattern of injury carries its own unique prognosis and theoretical best treatment; however, the optimum management of patients with TON remains unclear.

Pathophysiology

The mechanism of injury is one important way of classifying TON, with most authors using the terms “primary” and “secondary” to describe the mechanisms by which the optic nerve can be damaged. 1 2

Primary mechanisms are usually described as either “direct” (penetrating) or “indirect” (blunt trauma). Direct injuries are open injuries where an external object penetrates the tissues to impact the optic nerve. Indirect optic nerve injuries occur when the force of collision is imparted into the skull and this energy is absorbed by the optic nerve. 1

Direct injuries are less common than indirect injuries because of the protection offered by the orbit 3 and because a much larger surface area is available to receive the forces necessary for an indirect injury. Direct optic nerve injuries cause instantaneous and often irreversible damage to the portion of the nerve involved. Presumably this is due to transection of the retinal ganglion cell (RGC) axons. Even with treatment, direct injury to the optic nerve carries a poor prognosis. This is particularly true when the injured eye has no light perception immediately after the injury. 4 5

Indirect damage to the optic nerve occurs from a wide range of mechanisms. 6 7 8 9 Forces can be transmitted to the optic nerve in indirect injury in various ways, ranging from transmission of concussive forces directly to the tightly adherent nerve in the optic canal to transmission of forces from attached structures further away, such as may happen when rotational or translational forces are applied to the globe or brain (i.e., from a finger or a fall). 7 8 10 11 12 13 14 In particular, when the forehead or temporal region is struck, forces travel posteriorly through the optic canal, potentially injuring the optic nerve within the canal. 15 This may explain why it is much more common for frontal blunt trauma than occipital trauma to cause indirect TON. 7 16 17 In addition to forces applied to the skull or facial bones, forces applied directly to the globe (both high- and low-velocity mechanisms) can cause optic nerve damage, 14 18 19 20 although such damage is usually masked by severe trauma to the globe itself. In some cases, the blunt trauma is caused not by a direct blow to the skull but by a distant effect such as a blast wave. 21

In addition to primary direct or indirect optic nerve damage, further injury/exacerbation of injury can be caused by secondary mechanisms that occur after the moment of impact. Usually, visual loss is immediate; however, delayed visual loss, presumably from secondary mechanisms, occurs in at least 10% of cases. 22 Proposed mechanisms of secondary injury include vasospasm, edema, hemorrhage, and local compression of vessels or systemic circulatory insufficiency/failure leading to necrosis of the nerve. An extensive discussion of these secondary mechanisms is beyond the scope of this article.

Location of Injury

Both the anterior and posterior nerves can be injured by direct and indirect mechanisms as well as by one or more of the secondary mechanisms described earlier. 1

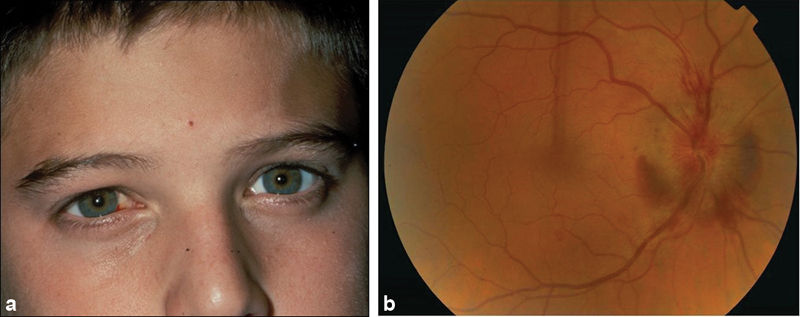

Anterior TON, whether of the direct or indirect variety, is characterized by optic disc swelling in the setting of other evidence of an optic neuropathy (e.g., decreased acuity, poor or absent color vision, a visual field defect, and a relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD) if the injury is unilateral or asymmetric). It usually is accompanied by injury to associated vasculature. This, in turn, can lead to retinal ischemia or infarction, central retinal vein occlusion, anterior ischemic optic neuropathy, or a combination of these phenomena ( Fig. 1 ). 23 24 In such cases, choroidal rupture can be an accompanying feature. 25

Fig. 1.

Anterior indirect traumatic optic neuropathy in a young boy who was hit in the right eye while playing soccer.

Because of the severity of optic nerve and, often, intraocular damage that is usually associated with direct injury to the anterior optic nerve, the prognosis for anterior TON usually is poor in this setting, regardless of treatment. 26 The prognosis for anterior TON caused by indirect injury, however, is not as clear. Indirect anterior TON usually results from blunt forces applied to the globe. Rotational and translational forces as well as sudden shifts in intraocular pressure have all been implicated in the pathogenesis of the damage. In such instances, the main force to the optic nerve appears to be at the junction of the nerve and sclera, on the side opposite the impact. 14 In most of these cases, regardless of the nature of the forces, no treatment is likely to be of benefit in limiting optic nerve damage, let alone restoring vision ( Fig. 2 ). The one exception to this rule is the presence of a hemorrhage in the subdural or subarachnoid space surrounding the anterior optic nerve. In such a setting, which can be suspected by the clinical findings and confirmed with computed tomography (CT) scanning, magnetic resonance (MR) imaging, or ultrasonography, an urgent optic nerve sheath fenestration may be beneficial, particularly if it is clear that the patient had vision immediately after the injury and/or had a normal-appearing optic disc but then experienced progressive visual loss associated with the development of optic disc swelling. 27

Fig. 2.

Fatal indirect anterior traumatic optic neuropathy. Note subdural hematoma at the junction of the optic nerve and globe.

Posterior TON is much more common than anterior TON, with indirect trauma being much more common than direct trauma. As is the case with anterior TON, posterior TON caused by direct or penetrating trauma has a poor prognosis regardless of treatment; however, this is not necessarily the case with respect to posterior TON caused by indirect trauma.

In patients with posterior TON caused by indirect trauma, the canalicular portion of the optic nerve is most often the site of damage, with the next most common portion being the intracranial portion of the nerve as it passes beneath the falciform fold. 6 7 8 12 13 23 28 29 30 There are several reasons for this. First, as noted earlier, studies have shown that blunt trauma to the frontal region produces shock waves that travel posteriorly toward and often through the canal, at least in part because the conical shape of the orbit may funnel forces to this particular region ( Fig. 3 ). 15 16 This concussive force may or may not be associated with fractures of the optic canal that can also introduce a crushing or lacerating component to the initial trauma. In addition, the optic canal is the only location along the length of the optic nerve where the nerve is tightly tethered to a fixed structure—the bone of the canal (via the nerve sheath and periosteum; Fig. 4 ). Thus, not only are concussive forces more likely to be propagated via bone to this portion of the nerve than to any other portion, but also this portion of the nerve has less ability to respond to even minor primary damage.

Fig. 3.

Direction of concussive forces from blunt trauma to the forehead. Note that the lines of force can traverse either the ipsilateral or the contralateral optic canal.

Fig. 4.

Horizontal section through the canalicular portion of the left optic nerve. Note the tight attachment of the dura to the nerve within the canal.

The canalicular portion of the optic nerve is also vulnerable to subsequent secondary injury following the initial injury. The tight confines of the canal make this portion of the nerve particularly vulnerable to edema and hemorrhage, resulting in a compartment syndrome causing further ischemia and secondary damage. 8 Additionally, this region of the nerve is a watershed zone, unlike other portions of the nerve that receive blood via rich anastomoses. It is not clear how—or if—this watershed component plays a role in the prevalence and evolution of secondary injury in posterior indirect TON to this region of the nerve, but it certainly may be a factor.

Causes

Series that have evaluated TON in the setting of both blunt and penetrating head and facial injuries have found that it is present in 0.7 to 2.5% of cases. 7 31 32 33 In most series, the vast majority of affected patients are young adult males. 28 34 Motor vehicle accidents, bicycle accidents, falls, assaults, and sport injuries are the most common causes of TON. 3 28 34 The trauma is usually severe, with 34 to 75% of cases in both prospective and retrospective series being associated with loss of consciousness and 36 to 82% of affected eyes having no light perception. 28 34 35 The male prevalence and other presenting characteristics of TON are similar in the pediatric and adult populations. 36 37

Clinical Evaluation

TON initially is a clinical diagnosis, with imaging frequently adding clarification to the full nature and extent of the injury. As noted earlier, as up to 2.5% of patients with head injury have TON, a high index of suspicion should be maintained for this condition in that setting. Thus, once a patient who has experienced facial or head trauma is deemed stable from a cardiorespiratory and neurologic standpoint, an in-depth ocular history and examination should be performed.

History

If the patient is unconscious or confused (as is often the case), history from witnesses should be sought. It is important to elicit from the history when the trauma happened, what the mechanism(s) were, what associated factors may have been present (any exposure to chemicals, etc.), and the nature and progression (or lack thereof) of visual deficits since the incident. This latter point is particularly important as it may indicate a secondary injury amenable to therapy.

Examination

The importance of the examination in the diagnosis of TON cannot be overemphasized, as patients are often unconscious or confused, with no witnesses available to provide an adequate history. General inspection of the eye and ocular adnexa is the first step. Any evidence of orbital or ocular penetrating injury should be noted, as should any periorbital swelling, ecchymosis, proptosis, and enophthalmos. 1 The orbital rim should be palpated gently for any fractures. When possible, a portable slit-lamp examination should be performed to determine if there is a hyphema or a lens dislocation, although the former can often be appreciated using a simple hand light.

If the patient is able to cooperate, his or her visual acuity should be assessed. It is usually significantly reduced, not infrequently to no light perception, light perception, or bare hand movements. For those eyes with better vision, delayed visual loss nevertheless may occur from secondary mechanisms (see above). Thus, serial assessments should be conducted in most settings. 28 34 Despite the importance of visual acuity (and, occasionally, color vision testing), the most important examination finding to look for in patients in whom TON is being considered is an RAPD, 36 as it will always be present unless there is anatomically symmetric trauma to both optic nerves. It is important to note, however, that an RAPD can be present in eyes with TON even when visual acuity is 20/20. Thus, although the finding of an RAPD in an eye without any visible retinal damage usually indicates TON, it does not necessarily correlate with the level of visual acuity. In addition, damage to the optic tract can also cause an RAPD. Thus, in a comatose or unresponsive patient, treatment—particularly surgical treatment (see later)—should not be initiated based solely on the presence of an RAPD. An RAPD can be detected, first, by simply assessing the pupillary reaction to light stimulation. In most cases, in the setting of isocoric pupils (i.e., both pupils are the same size), the failure of one pupil to constrict or the finding that one pupil constricts less briskly and more incompletely than the other suggests dysfunction of the afferent visual pathway. Next a “swinging flashlight test” should be performed, in which light is shined first in one eye for a few seconds and then in the other eye for the same length of time. 38 39 In all cases, the light source should be bright and focused. In questionable cases, a 0.3 log unit neutral density filter can be used to clarify the presence or absence of the defect, but if it takes a filter to determine that an RAPD is present, it is unlikely that the patient has profound visual loss. In patients with TON, the presence and degree of an RAPD appears to have a high correlation with both the initial and final visual acuities. 40 The severity of an RAPD can be measured objectively using neutral density filters. Alford et al found in a study of 19 consecutive patients with TON that no patients with an RAPD of ≥2.1 log units had better visual recovery than hand motions, whereas all patients with an RAPD of ≤1.5 log units recovered vision to 20/30 or better. 41

Visual fields also should be tested when possible. In many cases of known or suspected TON, the fields will have to be tested at the bedside using confrontation measures such as finger counting, finger wiggling, or hand waving, with more “formal” testing reserved for ambulatory, cooperative patients. There are no field defects that are pathognomonic for TON; however, if testing suggests or demonstrates homonymous or bitemporal defects that respect the vertical meridian, a process involving the optic chiasm or postgeniculate pathway may be present instead of, or in addition to, a TON. In addition to helping quantify initial visual function, formal visual field testing can also be used to monitor the vision over time. 7

A fundoscopic examination should be performed in all patients with known or suspected TON. In all cases, it is important before instilling any dilating agents to coordinate this plan with other providers, as at times, such as when the patient is being serially monitored for evidence of impending herniation, pupillary dilation may be contraindicated. When dilating agents are administered, both the agent and time instilled should be documented at the bedside and the information transmitted to both the physicians and the nurses caring for the patient. In addition, only short-acting agents should be used. 1 We have found it useful to place a sheet of paper over the patient's bed (and sometimes a piece of paper tape ON THE PATIENT'S FOREHEAD!) indicating the agents instilled and the time of instillation.

In patients with anterior TON, the fundus will always appear abnormal. If there has been a partial or complete evulsion of the globe from the nerve at the juncture of the lamina cribrosa, a partial or complete ring of hemorrhage will be seen or there will be a deep pit. 13 42 If the nerve has been injured between the globe and the entrance/exit of the central retinal artery/vein, evidence of a central retinal artery occlusion, central retinal vein occlusion, or both may be present. Disc swelling may also be seen acutely in patients with increased intracranial pressure, so this finding, particularly when bilateral, should be corroborated with other examination findings, such as the presence of an RAPD, before arriving at the diagnosis of anterior TON.

In fact, as the most common form of TON is posterior, the vast majority of patients with TON have a normal fundoscopic examination and, specifically, a normal-appearing optic disc. In such cases, the presence of an RAPD will be the only objective sign of optic nerve injury in a patient complaining of decreased vision in one eye or in a comatose or lethargic patient unable to undergo testing of visual acuity, color vision, and/or visual field.

Imaging

Imaging may be a valuable adjunct in the assessment of a patient with known or suspected TON. CT scanning is superb at outlining bony anatomy ( Fig. 5 ), whereas MR imaging is better for soft-tissue structure, although in patients with penetrating trauma, the presence of intraocular or intraorbital metallic objects must be assessed with either CT scanning or plain X-rays before MR imaging is performed.

Fig. 5.

CT scans from two patients with indirect retrobulbar traumatic optic neuropathy. Left: patient has a fracture of the left anterior clinoid process ( long arrow ) as well as the right skull base. Note that there is a soft-tissue shadow in the right sphenoid sinus, probably representing blood. Right: there is a fracture of the right anterior clinoid process extending to the optic canal.

Although imaging may help influence treatment in some cases, such as when diffuse or focal orbital hematomas, optic nerve sheath hematomas, or orbital emphysema are present, 43 44 imaging is performed in most cases to assess the overall neurologic and orbital status of the patients and to determine if there is any evidence of structural damage to the brain. There is no consensus on the significance of the presence of fractures or bony fragments in or near the optic canal or other areas of the orbit. Although some studies associate worse outcomes in patients with orbital fractures, 25 others do not. 40 Thus, in our opinion, the clinical picture still must guide management.

Management

Patients who experience direct trauma to the anterior and posterior optic nerve have a poor visual prognosis as do patients in whom there is indirect injury to the anterior optic nerve, regardless of the timing or type of intervention, although as noted earlier, a possible exception to this pessimistic prognosis is the association of an anterior TON with evidence of a subdural or subarachnoid hematoma adjacent to the orbital portion of the optic nerve. In such a setting, an urgent optic nerve sheath fenestration may be of benefit. 27

Currently, the most common management paradigms for patients with posterior indirect TON are observation without intervention, oral or intravenous corticosteroids of various doses, surgery, or a combination of surgery and steroid therapy. 45 In addition, there are a few other agents that have been suggested. Unfortunately, none of these options have been studied in any large, prospective, randomized clinical trials. 46 47 Thus, the optimum management of a patient with TON is unknown. 48 49 50 In the following sections, we will discuss the various management options in more detail.

Observation

Observation without intervention is a valid management option for patients with posterior TON. Many patients (>50% in some series) improve spontaneously, 23 28 34 51 and although patients with no light perception from TON have a worse visual prognosis than patients with some residual vision, 52 53 54 even patients with well-documented no light perception may improve to useful vision without treatment. 9 23 55 56 Indeed, there is no convincing evidence that any medical or surgical intervention is superior to observation. Observation without intervention is a particularly good choice when the patient is unconscious or unable to consent. Given that an RAPD can be present in the setting of 20/20 vision and that an RAPD need not be caused by optic nerve damage, even its presence does not necessarily indicate that a patient with a normal-appearing fundus has an optic neuropathy nor does it indicate the level of visual function unless the pupil is nonreactive to direct light but reacts normally consensually, in which case, one can be certain that the affected eye has no light perception.

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroid therapy came into vogue for the treatment of posterior TON in the early 1980s as it was thought that it could reduce edema and secondary inflammation following the injury. 57 Since then, varying dosing regimens of steroids have been suggested, ranging from low-dose (1–2 mg/kg/d) oral or intravenous administration to “high-dose” (1,000 mg/d) methylprednisolone in single or divided doses, to “megadose” (30 mg/kg of methylprednisolone as a bolus, followed by 5.4 mg/kg/h for 24–48 hours). 28 51 58 59

At the time of an exhaustive Cochrane review completed on May 21, 2013, 46 there had been only one small trial investigating the effects of systemic corticosteroids versus placebo in the treatment of TON in a prospective, randomized controlled fashion. This trial, performed by Entezari et al, 60 reported the visual outcome in 31 eyes of 31 patients with TON who were randomly assigned to either a treatment group (16 eyes) or a placebo group (15 eyes) within 7 days of initial injury. The treatment group received 250 mg of intravenously administered methylprednisolone every 6 hours for 3 days followed by 1 mg/kg/d of oral prednisolone for 14 days. The placebo group received 50 mL of normal saline intravenously every 6 hours for 3 days, followed by placebo for 14 days. An increase of at least 0.4 logMAR (Logarithm of the Minimum Angle of Resolution) in final visual acuity measured at 3 months was considered visual improvement. Although both groups showed significant improvement in final visual acuity compared with initial visual acuity ( p < 0.001 and 0.010, respectively), there were no significant differences in final acuity between the two groups. Indeed, 68.8% of the steroid-treated group had significant improvement in visual acuity compared with 53.3% of the placebo group ( p = 0.38). A more recent meta-analysis of treatment options for TON 61 concluded that the literature suggests that patients with TON who undergo early optic canal decompression have better visual outcomes compared with those who are observed or treated with steroids; however, the authors pointed out that the lack of a randomized controlled trial—and the inherent surgical selection and publication bias of the available reports—limits a direct comparison between surgical decompression and conservative management.

Based on currently available evidence, we agree with Steinsapir and Goldberg 45 that there is no role for “megadose” steroids in the treatment of TON, and also there is little evidence for the use of “high-dose” methylprednisolone.

Erythropoietin

The cytokine hormone erythropoietin (EPO), which had been long known and used as an agent to promote hematopoiesis, is able to reduce neuronal apoptosis and exert protective effect in experimental models of mechanical trauma, neuronal inflammation, cerebral and retinal ischemia, and oxidative stress, and optic nerve injury. Entezari et al 62 performed a small, prospective, nonrandomized study in patients with TON of <2 weeks' duration using EPO in a dose of 20,000 IU intravenously injected daily for 3 days and concluded that there was some benefit; however, Kashkouli et al 54 subsequently failed to show any difference in outcome between patients who were observed and patients treated with EPO or steroids.

Surgery

The results of surgery for TON have never been studied in a large, prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled fashion. 47 As noted earlier, visual loss from direct optic nerve trauma, in which the axons have been transected, cannot be reversed by any current surgical technique. Similarly, anterior indirect TON usually will not benefit from surgery, a possible exception being when there is compression of an otherwise intact optic nerve by a subdural or subarachnoid hematoma that can be evacuated via an optic nerve sheath fenestration. 27

As noted earlier, the most common site of injury to the optic nerve in posterior indirect TON is within the optic canal because the canalicular portion of the nerve is the most vulnerable region to trauma due to its being fixed via the dura to the periosteum of the canal. This portion of the nerve is also theoretically vulnerable to compressive and/or lacerating forces from fracture, hematoma expansion, swelling, etc. For this reason, optic canal decompression is sometimes advocated when a surgical lesion appears to be involving this portion of the nerve. Several approaches have been described, with the technique currently in favor being an endoscopic transnasal, transethmosphenoid approach. 63 64 If such surgery is thought to be appropriate, it probably should be performed immediately or no later than 2 to 3 days following the injury; however, regardless of the technique used, there are no convincing studies to date showing any clear benefit to optic canal decompression. 28 34 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71

Given the unclear benefit of optic canal decompression, it may be prudent to pursue this treatment only in instances in which the patient's vision is clearly normal immediately after the injury and then deteriorates or clearly is progressively worsening, the site of injury is clearly the optic canal, and, perhaps most importantly, the patient can consent to treatment even though he or she understands both the unproven benefits and the potential risks (e.g., further visual loss, damage to other neural or vascular structures). 66 As noted earlier, unconscious patients should not be considered surgical candidates as they cannot give consent and there is no way to assess their vision.

Recommendations

Given our current deficiencies in knowledge regarding how to best manage TON, we adhere to the dictum “primum non nocere” and emphasize that it is appropriate to observe any and all patients with TON, regardless of the level of vision in the affected eye. In addition, it is no longer appropriate to argue that “steroids can't hurt,” particularly “megadose” steroids. Although there is no evidence that “high-dose” steroids (e.g., 1,000 mg/d of methylprednisolone) are harmful to visual recovery in human TON, there certainly is no evidence that they are helpful. As far as surgery is concerned, in rare cases of a clear-cut compartment syndrome within the orbit or optic nerve sheath, particularly when new and/or progressive, immediate optic nerve fenestration should be performed. In select cases of known or presumed injury to the canalicular optic nerve, particularly when there is clear-cut delayed visual loss or worsening of vision, immediate decompression of the optic nerve within the canal may be reasonable, but only after a well-documented discussion with the patient and family. No treatment should be the default with unconscious patients with the possible exception of those in whom the pupil does not react directly but reacts consensually.

Case Examples

A 27-year-old man in excellent general health was riding his bicycle when he was hit by a car. He was thrown off his bike and hit his head on the pavement, whereupon he lost consciousness. He was taken by ambulance to the emergency department at a local hospital where he underwent a CT scan of the brain and orbits that showed a small right frontal subdural hematoma and a fracture of the right optic canal. He gained consciousness in the emergency room and noted that he could not see well. An ophthalmologist was consulted; visual acuity of bare light perception with the right eye and 20/15 with the left eye was found. There was a marked right RAPD. The eyes were white and quiet. Ophthalmoscopy revealed normal-appearing ocular fundi. A discussion was held with him regarding management options. It was elected to treat him with methylprednisolone 1 g/d. After 2 days, his vision had not improved. He was therefore given the option of being observed without intervention or undergoing an endoscopic, transnasal transethmoidal optic canal decompression, making it clear to him (and his wife who was in the room during the discussion) that there was no clear-cut evidence that this would result in visual improvement. He agreed and the surgery was performed the following day. Postoperatively, the patient's visual acuity improved to counting fingers at 3 feet; it did not improve further over the subsequent 3 months.

A 37-year-old woman was involved in a motor vehicle accident, sustaining blunt trauma to the left frontal region. She did not lose consciousness. She was taken to the emergency department at a local hospital where she was noted to have marked left upper lid swelling. A CT scan showed left ethmoid fractures but no fracture of either optic canal. The patient was not able to state if she had any change in her vision immediately after the accident. An ophthalmological examination revealed visual acuity of 20/20 with the right eye and 20/800 with the left eye. There was a left RAPD. The ocular fundi were normal in appearance. A discussion was held with the patient and her family regarding options of management and she elected to be observed without intervention. Her visual acuity improved to 20/100 over the following 2 weeks and then stabilized.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest None declared.

Pearls and Tips.

Always check for an RAPD in any patient complaining of decreased vision in one eye following head trauma.

Most cases of indirect TON are retrobulbar; thus, the ocular fundus will appear normal.

In patients with TON, CT scanning is superb at outlining bony anatomy, whereas MR imaging is better for soft-tissue structure.

In patients with penetrating trauma, the presence of intraocular or intraorbital metallic objects must be assessed with either CT scanning or plain X-rays before MR imaging is performed.

Patients with TON associated with imaging evidence of an optic canal fracture may be less likely to experience spontaneous visual improvement.

Patients with TON associated with no light perception vision have a worse prognosis compared with patients who have some residual vision; however, even patients with no light perception can experience significant spontaneous visual improvement.

There is no proven treatment for TON.

Megadose steroid therapy (30 mg/kg of methylprednisolone as a bolus, followed by 5.4 mg/kg/h for 24–48 hours) should never be used to treat TON as it may increase the risk of death.

References

- 1.Steinsapir K D, Goldberg R A. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005. Traumatic optic neuropathies; pp. 431–446. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levkovitch-Verbin H, Quigley H A, Martin K R, Zack D J, Pease M E, Valenta D F. A model to study differences between primary and secondary degeneration of retinal ganglion cells in rats by partial optic nerve transection. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44(08):3388–3393. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steinsapir K D, Goldberg R A. Traumatic optic neuropathy. Surv Ophthalmol. 1994;38(06):487–518. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(94)90145-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feist R M, Kline L B, Morris R E, Witherspoon C D, Michelson M A. Recovery of vision after presumed direct optic nerve injury. Ophthalmology. 1987;94(12):1567–1569. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(87)33245-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang B H, Robertson B C, Girotto J A. Traumatic optic neuropathy: a review of 61 patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107(07):1655–1664. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200106000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kline L B, Morawetz R B, Swaid S N. Indirect injury of the optic nerve. Neurosurgery. 1984;14(06):756–764. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198406000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turner J. Indirect injuries of the optic nerve. Brain. 1943;66:140–151. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walsh F B. Pathological-clinical correlations. I. Indirect trauma to the optic nerves and chiasm. II. Certain cerebral involvements associated with defective blood supply. Invest Ophthalmol. 1966;5(05):433–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lessell S. Indirect optic nerve trauma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1989;107(03):382–386. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1989.01070010392031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gross C E, DeKock J R, Panje W R, Hershkowitz N, Newman J. Evidence for orbital deformation that may contribute to monocular blindness following minor frontal head trauma. J Neurosurg. 1981;55(06):963–966. doi: 10.3171/jns.1981.55.6.0963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Purvin V. Evidence of orbital deformation in indirect optic nerve injury. Weight lifter's optic neuropathy. J Clin Neuroophthalmol. 1988;8(01):9–11. doi: 10.3109/01658108808996018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foster B SB, March G AG, Lucarelli M JM, Samiy N, Lessell S. Optic nerve avulsion. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997;115(05):623–630. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1997.01100150625008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsopelas N V, Arvanitis P G. Avulsion of the optic nerve head after orbital trauma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998;116(03):394–394. doi: 10.1001/archopht.116.3.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cirovic S, Bhola R M, Hose D R. Computer modelling study of the mechanism of optic nerve injury in blunt trauma. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90(06):778–783. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.086538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manson P N, Stanwix M G, Yaremchuk M J, Nam A J, Hui-Chou H, Rodriguez E D. Frontobasal fractures: anatomical classification and clinical significance. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(06):2096–2106. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181bf8394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spetzler R F, Spetzler H. Holographic interferometry applied to the study of the human skull. J Neurosurg. 1980;52(06):825–828. doi: 10.3171/jns.1980.52.6.0825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Sukhun J, Kontio R, Lindqvist C. Orbital stress analysis: part I—simulation of orbital deformation following blunt injury by finite element analysis method. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64(03):434–442. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fard A K, Merbs S L, Pieramici D J. Optic nerve avulsion from a diving injury. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;124(04):562–564. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70879-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bellezza A J, Hart R T, Burgoyne C F. The optic nerve head as a biomechanical structure: initial finite element modeling. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41(10):2991–3000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cirovic S, Bhola R M, Hose D R, Howard I C, Lawford P V, Parsons M AG. A computational study of the passive mechanisms of eye restraint during head impact trauma. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Engin. 2005;8(01):1–6. doi: 10.1080/10255840500062989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weichel E D, Colyer M H, Ludlow S E, Bower K S, Eiseman A S. Combat ocular trauma visual outcomes during operations iraqi and enduring freedom. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(12):2235–2245. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tso M O, Shih C Y, McLean I W. Is there a blood-brain barrier at the optic nerve head? Arch Ophthalmol. 1975;93(09):815–825. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1975.01010020703008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hughes B. Indirect injury of the optic nerves and chiasma. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp. 1962;111:98–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hedges T R, III, Gragoudas E S. Traumatic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Ann Ophthalmol. 1981;13(05):625–628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petrarca R, Saldana M. Choroidal rupture and optic nerve injury with equipment designated as “child-safe.”. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012:bcr2012006476. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2012-006476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levin L A. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2007. Traumatic optic neuropathy; pp. 45–46. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mauriello J A, DeLuca J, Krieger A, Schulder M, Frohman L. Management of traumatic optic neuropathy: a study of 23 patients. Br J Ophthalmol. 1992;76(06):349–352. doi: 10.1136/bjo.76.6.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levin L A, Beck R W, Joseph M P, Seiff S, Kraker R. The treatment of traumatic optic neuropathy: the International Optic Nerve Trauma Study. Ophthalmology. 1999;106(07):1268–1277. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(99)00707-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park J H, Frenkel M, Dobbie J G, Choromokos E. Evulsion of the optic nerve. Am J Ophthalmol. 1971;72(05):969–971. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(71)91699-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crowe N W, Nickles T P, Troost B T, Elster A D. Intrachiasmal hemorrhage: a cause of delayed post-traumatic blindness. Neurology. 1989;39(06):863–865. doi: 10.1212/wnl.39.6.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Edmund J, Godtfredsen E. Unilateral optic atrophy following head injury. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1963;41(06):693–697. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1963.tb03588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nau H E, Gerhard L, Foerster M, Nahser H C, Reinhardt V, Joka T.Optic nerve trauma: clinical, electrophysiological and histological remarks Acta Neurochir (Wien) 198789(1–2):16–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.al-Qurainy I A, Dutton G N, Ilankovan V, Titterington D M, Moos K F, el-Attar A. Midfacial fractures and the eye: the development of a system for detecting patients at risk of eye injury—a prospective evaluation. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991;29(06):368–369. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(91)90002-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee V, Ford R L, Xing W, Bunce C, Foot B. Surveillance of traumatic optic neuropathy in the UK. Eye (Lond) 2010;24(02):240–250. doi: 10.1038/eye.2009.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rajiniganth M G, Gupta A K, Gupta A, Bapuraj J R. Traumatic optic neuropathy: visual outcome following combined therapy protocol. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129(11):1203–1206. doi: 10.1001/archotol.129.11.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goldenberg-Cohen N, Miller N R, Repka M X. Traumatic optic neuropathy in children and adolescents. J AAPOS. 2004;8(01):20–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2003.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ford R L, Lee V, Xing W, Bunce C. A 2-year prospective surveillance of pediatric traumatic optic neuropathy in the United Kingdom. J AAPOS. 2012;16(05):413–417. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stanley J A, Baise G R. The swinging flashlight test to detect minimal optic neuropathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1968;80(06):769–771. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1968.00980050771016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bell R A, Waggoner P M, Boyd W M, Akers R E, Yee C E. Clinical grading of relative afferent pupillary defects. Arch Ophthalmol. 1993;111(07):938–942. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1993.01090070056019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tabatabaei S A, Soleimani M, Alizadeh M. Predictive value of visual evoked potentials, relative afferent pupillary defect, and orbital fractures in patients with traumatic optic neuropathy. Clin Ophthalmol. 2011;5:1021–1026. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S21409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alford M A, Nerad J A, Carter K D. Predictive value of the initial quantified relative afferent pupillary defect in 19 consecutive patients with traumatic optic neuropathy. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;17(05):323–327. doi: 10.1097/00002341-200109000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hillman J S, Myska V, Nissim S. Complete avulsion of the optic nerve. A clinical, angiographic, and electrodiagnostic study. Br J Ophthalmol. 1975;59(09):503–509. doi: 10.1136/bjo.59.9.503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jordan D R, White G L, Jr, Anderson R L, Thiese S M. Orbital emphysema: a potentially blinding complication following orbital fractures. Ann Emerg Med. 1988;17(08):853–855. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(88)80571-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wood B J, Mirvis S E, Shanmuganathan K. Tension pneumocephalus and tension orbital emphysema following blunt trauma. Ann Emerg Med. 1996;28(04):446–449. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(96)70014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Steinsapir K D, Goldberg R A. Traumatic optic neuropathy: an evolving understanding. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;151(06):928–93300. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yu-Wai-Man P, Griffiths P G. Steroids for traumatic optic neuropathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;6(06):CD006032. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006032.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yu-Wai-Man P, Griffiths P G. Surgery for traumatic optic neuropathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;6:CD005024. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005024.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arnold A.Symposium on the treatment of traumatic optic neuropathy resolved: corticosteroids should not be usedThe 2nd World Congress on Controversies in Ophthalmology (COPHy), Barcelona, Spain, March 3–6, 2011. Available at:http://www.comtecmed.com/cophy/2011/Uploads/assets/arnold.pdf

- 49.Berestka J S, Rizzo J FI., III Controversy in the management of traumatic optic neuropathy. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1994;34(03):87–96. doi: 10.1097/00004397-199403430-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Volpe N J, Levin L A. How should patients with indirect traumatic optic neuropathy be treated? J Neuroophthalmol. 2011;31(02):169–174. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0b013e31821c9b11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yip C C, Chng N W, Au Eong K G, Heng W J, Lim T H, Lim W K. Low-dose intravenous methylprednisolone or conservative treatment in the management of traumatic optic neuropathy. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2002;12(04):309–314. doi: 10.1177/112067210201200410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lai I-L, Liao H-T. Risk factor analysis for the outcomes of indirect traumatic optic neuropathy with no light perception at initial visual acuity testing. World Neurosurg. 2018;115:e620–e628. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.04.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang J, Chen X, Wang Z. Selection and prognosis of optic canal decompression for traumatic optic neuropathy. World Neurosurg. 2020;138:e564–e578. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kashkouli M B, Yousefi S, Nojomi M. Traumatic optic neuropathy treatment trial (TONTT): open label, phase 3, multicenter, semi-experimental trial. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2018;256(01):209–218. doi: 10.1007/s00417-017-3816-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hooper R S. Orbital complications of head injury. Br J Surg. 1951;39(154):126–138. doi: 10.1002/bjs.18003915406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wolin M J, Lavin P J. Spontaneous visual recovery from traumatic optic neuropathy after blunt head injury. Am J Ophthalmol. 1990;109(04):430–435. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)74609-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Anderson R L, Panje W R, Gross C E. Optic nerve blindness following blunt forehead trauma. Ophthalmology. 1982;89(05):445–455. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(82)34769-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Seiff S R. High dose corticosteroids for treatment of vision loss due to indirect injury to the optic nerve. Ophthalmic Surg. 1990;21(06):389–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bracken M B, Shepard M J, Collins W F. A randomized, controlled trial of methylprednisolone or naloxone in the treatment of acute spinal-cord injury. N Engl J Med. 1990;323(17):1207–1209. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199010253231712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Entezari M, Rajavi Z, Sedighi N, Daftarian N, Sanagoo M. High-dose intravenous methylprednisolone in recent traumatic optic neuropathy; a randomized double-masked placebo-controlled clinical trial. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2007;245(09):1267–1271. doi: 10.1007/s00417-006-0441-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Martinez-Perez R, Albonette-Felicio T, Hardesty D A, Carrau R L, Prevedello D M.Outcome of the surgical decompression for traumatic optic neuropathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis Neurosurg Rev 2020(e- pub ahead of print) 10.1007/s10143-020-01260-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Entezari M, Esmaeili M, Yaseri M. A pilot study of the effect of intravenous erythropoetin on improvement of visual function in patients with recent indirect traumatic optic neuropathy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2014;252(08):1309–1313. doi: 10.1007/s00417-014-2691-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yu B, Ma Y-J, Tu Y-H, Wu W-C. Newly onset indirect traumatic optic neuropathy-surgical treatment first versus steroid treatment first. Int J Ophthalmol. 2020;13(01):124–128. doi: 10.18240/ijo.2020.01.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yan W, Lin J, Hu W, Wu Q, Zhang J.Combination analysis on the impact of the initial vision and surgical time for the prognosis of indirect traumatic optic neuropathy after endoscopic transnasal optic canal decompression Neurosurg Rev 2020(e- pub ahead of print) 10.1007/s10143-020-01273-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wohlrab T-M, Maas S, de Carpentier J P. Surgical decompression in traumatic optic neuropathy. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2002;80(03):287–293. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.2002.800311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Onofrey C B, Tse D T, Johnson T E. Optic canal decompression: a cadaveric study of the effects of surgery. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;23(04):261–266. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e3180cac220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Goldberg R A, Steinsapir K D. Extracranial optic canal decompression: indications and technique. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;12(03):163–170. doi: 10.1097/00002341-199609000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Horiguchi K, Murai H, Hasegawa Y, Mine S, Yamakami I, Saeki N. Endoscopic endonasal trans-sphenoidal optic nerve decompression for traumatic optic neuropathy: technical note. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2010;50(06):518–522. doi: 10.2176/nmc.50.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sofferman R A. Transnasal approach to optic nerve decompression. Oper Tech Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;2(03):150–156. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Otani N, Wada K, Fujii K. Usefulness of extradural optic nerve decompression via trans-superior orbital fissure approach for treatment of traumatic optic nerve injury: surgical procedures and techniques from experience with 8 consecutive patients. World Neurosurg. 2016;90:357–363. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lin J, Hu W, Wu Q, Zhang J, Yan W.An evolving perspective of endoscopic transnasal optic canal decompression for traumatic optic neuropathy in clinic Neurosurg Rev 2019(e- pub ahead of print) 10.1007/s10143-019-01208-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]