Highlights

-

•

The deficits of joint position sense (JPS) and kinesthesia exist in the injured ankles of patients with chronic ankle instability (CAI).

-

•

When compared with the uninjured contralateral side, the kinesthesia, passive and active JPS of ankle inversion and the kinesthesia of ankle plantarflexion are impaired in patients with CAI.

-

•

When compared with healthy controls, the kinesthesia and active JPS of ankle inversion and eversion are impaired in patients with CAI.

-

•

The evidence of the proprioception deficits in knee and shoulder of patients with CAI is not enough.

Keywords: Chronic ankle instability, Joint position sense, Kinesthesia, Proprioception

Abstract

Background

Acute ankle injury causes damage to joint mechanoreceptors and deafferentation and contributes to proprioception deficits in patients with chronic ankle instability (CAI). We aimed to explore whether deficits of proprioception, including kinesthesia and joint position sense (JPS), exist in patients with CAI when compared with the uninjured contralateral side and healthy people. We hypothesized that proprioception deficits did exist in patients with CAI and that the deficits varied by test methodologies.

Methods

The study was a systematic review and meta-analysis. We identified studies that compared kinesthesia or JPS in patients with CAI with the uninjured contralateral side or with healthy controls. Meta-analyses were conducted for the studies with similar test procedures, and narrative syntheses were undertaken for the rest.

Results

A total of 7731 studies were identified, of which 30 were included for review. A total of 21 studies were eligible for meta-analysis. Compared with the contralateral side, patients with CAI had ankle kinesthesia deficits in inversion and plantarflexion, with a standardized mean difference (SMD) of 0.41 and 0.92, respectively, and active and passive JPS deficits in inversion (SMD = 0.92 and 0.72, respectively). Compared with healthy people, patients with CAI had ankle kinesthesia deficits in inversion and eversion (SMD = 0.64 and 0.76, respectively), and active JPS deficits in inversion and eversion (SMD = 1.00 and 4.82, respectively). Proprioception deficits in the knee and shoulder of patients with CAI were not statistically significant.

Conclusion

Proprioception, including both kinesthesia and JPS, of the injured ankle of patients with CAI was impaired, compared with the uninjured contralateral limbs and healthy people. Proprioception varied depending on different movement directions and test methodologies. The use of more detailed measurements of proprioception and interventions for restoring the deficits are recommended in the clinical management of CAI.

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Lateral ankle sprain is one of the most common sports injuries, and it has the highest recurrence rate among all lower-extremity musculoskeletal injuries.1,2 More than 2 million ankle sprains are treated in the UK and USA each year, which results in more than USD2 billion in health care costs.3 Following the initial sprain, about 40% of patients report repetitive bouts of the ankle “giving way” and recurring sprains or the feeling that the ankle joint is unstable. These bouts are termed chronic ankle instability (CAI).4,5 Fixing mechanical laxity through surgery is usually suggested for patients suffering persistent CAI symptoms, while other patients continue to experience poor ankle function.6,7 Therefore, exploring other factors that contribute to CAI is crucial for developing more closely targeted interventions.

To date, many studies have focused on sensorimotor deficits in CAI.8, 9, 10, 11, 12 The first proposed sensorimotor factor in ligament injuries was joint proprioception, which was originally defined as the perception of position and movement (referring to “position sense” and “kinesthesia”, respectively), but now includes other mechanical senses, such as force and vibration.13, 14, 15 The impaired proprioceptive nerve endings within the sprained joints have been widely blamed for the functional losses in ligament injuries.16,17 In addition, low proprioception is also associated with worse sports performance, higher risk of ankle-related sports injuries, and the progression of post-injury osteoarthrosis.13, 14, 15,18

Consistent results have been found in previous systematic reviews of non-specific proprioception tests in CAI, such as dynamic balance and posture-control deficits.11,12 However, original studies and reviews of specific tests of the originally defined proprioception in CAI have produced conflicting results.12,19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25 Munn et al.19 and Hiller et al.12 conducted meta-analyses of this content, but their results were inconsistent concerning joint position sense (JPS) deficits and failed to pool data on kinesthesia. Lack of studies and full considerations of test methodologies, including comparison types and movement directions, might be one of the key reasons for the inconsistency.26 Also, both studies focused only on the ankle, and there were pieces of evidence indicating that kinematics beyond the ankle could also be altered by CAI.27,28 As a result, an updated and comprehensive review of proprioception changes in CAI patients was necessary.

Thus, the aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to determine whether the originally defined proprioception (kinesthesia and JPS) was impaired in patients with CAI compared with the uninjured contralateral side or healthy controls. We hypothesized that proprioception deficits did exist in patients with CAI.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

This review was composed according to the guidelines for Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE).29 The protocol was prospectively registered in the PROSPERO platform (CRD42020169730).

2.2. Search strategy

Two authors (XX and TM) independently conducted a systematic literature search of 7 electronic databases—EMBASE, Web of Science, SPORTDiscus, PubMed, Scopus, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and Cochrane Library—with the time period set from inception to 18 February 2020. Reference lists of each included paper were also checked manually. The search strategy was made up of 3 strings of keywords grouped with “AND”. These keywords included (1) ankle-related terms, (2) injury-related terms, and (3) proprioception-related terms, and the terms within each string were grouped with “OR”. The full search strategy for PubMed can be found in online Supplementary Material 1.

2.3. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: peer-reviewed human studies in English that investigated joint proprioception (JPS and kinesthesia) in individuals with histories of ankle sprain and CAI symptoms compared with either the uninjured contralateral side or healthy controls. For the studies with interventions (e.g., taping, treatment, or fatigue), the data without any intervention (e.g., baseline or non-intervention control) had to be reported. If the studies used tests that mixed the joint movement directions or included bilaterally injured people using between-limbs comparison, they were excluded.

2.4. Article selections and data extraction

Studies were reviewed independently by 2 authors (XX and TM). If disagreements could not be resolved through discussion, a third reviewer (YH) was consulted. The same procedure was applied to the studies to extract the following information: demographic data, sample size, details of test methodology, joint proprioception results (mean and SD), and test reliability. The authors were contacted if numerical data were confusing or not reported.

To measure kinesthesia, the threshold of detection of passive movement (TTDPM) test was used, in which participants were asked to press a stop button when they perceived the passive movement, and the mean perceived angle was set as the kinesthesia score.21,30,31 To measure JPS, the joint position reproduction (JPR) test and the active movement extent discrimination assessment (AMEDA) tests were used. For the JPR test, participants were presented with a predetermined target joint angle and were then asked to reproduce that angle passively through stop bottoms or actively by themselves.15,32 There were 3 kinds of JPS scores in the JPR test: (1) absolute error (AE) was calculated from the average absolute deviation between the target and reproduced angle, representing the magnitude of errors, (2) constant error (CE) was calculated from the average deviation between the target and reproduced angle, representing both magnitude and direction of errors, and (3) variable error (VE) was calculated from the average deviation of reproduced angles, representing the consistency of errors.30 AE was accepted as the most sensitive error to reveal deficits in CAI, compared with CE, VE, and mean reproduced angles, and it was chosen as our main focus.26,30,33 For the AMEDA test, participants stood with free vision and were asked to experience several movement displacement distances and then judge the random orderly positions.34,35 The area under the curve of operating characteristic analysis was calculated as the JPS score for the AMEDA test.34,35

2.5. Quality and risk of bias assessment

All the authors discussed the standards for each item before formally rating them, and 2 authors (XX and TM) rated the included studies independently. The inter-rater agreements for the initial ratings were calculated, and a third reviewer (YH) was consulted when there were disagreements.

To assess the quality of the studies, the epidemiological appraisal instrument, which included 33 items for observational studies, was applied.36 Each item was scored as “Yes” (1 point), “Partial” (0.5 point), “No” (0 point), or “Unable to determine” (0 point).27,36 An average score was calculated for overall quality.27 To evaluate the risk of bias, a standardized tool recommended by the Non-Randomized Studies Group of the Cochrane Collaboration was applied; this tool included performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, selection bias, and control of confounding for details of tests and analysis.27,37 To assess the variability of patients with CAI, the recommendations of the International Ankle Consortium were applied.5 The standard CAI criteria included (1) at least 1 significant ankle sprain that occurred at least 12 months previously and resulted in pain, swelling, and an interruption of at least one day of desired physical activity, (2) the absence of any ankle injury in the past 3 months, and (3) the presence of at least one of the 3 classical symptoms of CAI: at least 2 episodes of “giving way” in the past 6 months, at least 2 sprains in the same ankle, and self-reported ankle instability confirmed by a validated questionnaire.5

2.6. Statistical analysis

A meta-analysis of the random-effects model was performed using Stata (Version14; Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA) for the studies that were similar in comparison type, proprioception type, test type, and movement direction. Subgroup analyses were conducted when appropriate. Narrative syntheses were undertaken for the rest of the studies.

The standardized mean difference (SMD) between patients with CAI and controls was calculated for all data, with 95% confidence intervals (95%CIs). Higher SMD represented larger joint proprioception deficits in patients with CAI; 0.2–0.5 were classified as weak effect size, >0.5–0.8 were classified as moderate effect size, and >0.8 were classified as large effect size.38,39 To evaluate heterogeneity, Q and I2 statistics were calculated, with p < 0.05 considered as statistically significant and I2 ≥ 75% considered as indicating high heterogeneity.27,40 Publication bias was quantitatively assessed by the Egger regression test, with p ≥ 0.1 indicating no significant publication bias.41 To find and remove the potential source of high heterogeneity and to test the stability of the pooled results, sensitivity analysis using the one-study-removed method was conducted for all included analyses.27

The kappa (κ) values of inter-rater agreements between the 2 reviewers (XX and TM) were calculated using SPSS Version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), with κ > 0.8 as almost perfect agreement.27,42

3. Results

3.1. Study selection and characteristics

The literature search identified 7731 potentially eligible studies, and 30 studies were included in the final review. The selection process and the reasons for exclusion are presented in a flow diagram (Fig. 1). Among the included articles, 27 studies investigated proprioception of the ankle, and 3 studies focused on other joints (2 on knees and 1 on shoulders). The mean age of patients with CAI ranged from 21.0 to 30.0 years, and the mean age of healthy participants (controls) ranged from 20.1 to 31.0 years. More study characteristics, including sample size, devices, details on the methodologies used, reliability, and summarized results are presented in online Supplementary Material 2.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the systematic review selection process. BL = between limbs; CAI = chronic ankle instability; CINAHL = Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature.

3.2. Quality and risk-of-bias assessment

For the quality assessment using the epidemiological appraisal instrument tool, 948 agreements were achieved from 990 items (κ = 0.937), and the rating score ranged from 0.45 to 0.64, with 0.50 as the median score. For the risk-of-bias evaluation, 204 agreements were achieved from 210 items (κ = 0.934), and all studies described demographic details, enrolled a representative “chronic ankle instability” population, and made an appropriate comparison. No significant publication bias (p ranged 0.10–0.78) was observed for the results of meta-analysis. For the variability of included patients with CAI, 229 agreements were achieved from 240 items (κ = 0.922). All studies required a history of sprain and at least one of 3 required symptoms as inclusion criteria. The detailed rating scales are presented in online Supplementary Material 3.

3.3. Proprioception

3.3.1. Ankle kinesthesia: between limbs

Five studies investigated kinesthesia between the injured ankle and the uninjured contralateral side. The data from 1 study of ankle kinesthesia, published in the 1980s, were based on judgments related to passive plantarflexion, and the sprained ankle showed significantly lower accuracy in both movement (p < 0.001) and non-movement (p < 0.05).43 The remaining 4 studies used TTDPM measurements, measured in degrees. For inversion, the pooled results revealed a weak effect for kinesthesia deficits (SMD = 0.41, I2 = 0.0%)21,44,45 (Fig. 2A). For plantarflexion, the pooled results show a large effect for kinesthesia deficits (SMD = 0.92, I2 = 0.0%)20,45 (Fig. 2B). We found no studies that investigated eversion or dorsiflexion.

Fig. 2.

Kinesthesia compared with the contralateral healthy limb in (A) inversion and (B) plantarflexion. Positive SMD indicates kinesthesia deficits in the injured ankle. CI = confidence interval; SMD = standardized mean difference; TTDPM = threshold to detection of passive motion test.

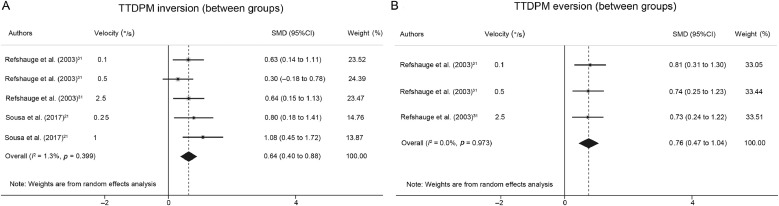

3.3.2. Ankle kinesthesia: between groups

Only 2 studies of kinesthesia enrolled healthy people as controls, and both of them applied TTDPM measurements. For inversion, the pooled results reveal a moderate effect for kinesthesia deficits (SMD = 0.64, I2 = 1.3%)21,31 (Fig. 3A). For eversion, only 1 study with 3 different velocities showed a moderate effect for kinesthesia deficits (SMD = 0.76, I2 = 0.0%)31 (Fig. 3B). We found no studies that investigated plantarflexion or dorsiflexion.

Fig. 3.

Kinesthesia compared with healthy people in (A) inversion and (B) eversion. Positive SMD indicates kinesthesia deficits in the injured ankle. CI = confidence interval; SMD = standardized mean difference; TTDPM = threshold to detection of passive motion test.

3.3.3. Ankle JPS: between limbs

Eleven studies compared JPS between injured ankles and the uninjured contralateral sides. All these studies used the JPR test to measure the AE directly, and 10 studies with AE were included in the pooled analyses. For inversion, the pooled results of active JPR show a large effect of deficits (SMD = 0.92, I2 = 81.5%),21,45, 46, 47 and the pooled results of passive JPR show a moderate effect of deficits (SMD = 0.72, I2 = 66.6%)21,22,45,48, 49, 50 (Fig. 4A). The only study with CE did not detect a significant difference (SMD = –0.12, 95%CI: –0.51 to 0.27).51 For eversion, only 1 study applied CE, which also revealed no significant difference (SMD = –0.04, 95%CI: –0.70 to 0.61).51 For plantarflexion, the pooled results of active JPR showed no significant difference (SMD = 0.68, I2 = 76.5%),45,52 whereas the pooled results of passive JPR show a large effect of deficits (SMD = 1.00, I2 = 65.1%)20,45,52 (Fig. 4B). We found no studies of dorsiflexion.

Fig. 4.

Joint position sense compared with the contralateral healthy limb in (A) inversion and (B) plantarflexion. Positive SMD indicates kinesthesia deficits in the injured ankle. CI = confidence interval; JPR = joint position reproduction test; SMD = standardized mean difference.

3.3.4. Ankle JPS: between groups

Seventeen studies investigated JPS and enrolled healthy participants as controls. Results from 2 studies that used the AMEDA test and 12 studies that directly measured JPR with AE were pooled. For inversion, the pooled results of active JPR showed a large effect of deficits (SMD = 1.00, I2 = 86.2%),47,53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58 whereas the pooled results of passive JPR showed no significant difference (SMD = 0.11, I2 = 0.0%)21,23,49,59 (Fig. 5A). As for the pooled results from the 2 studies using the AMEDA test, a large effect of lower accuracy to joint position (SMD = –1.04, 95%CI: –1.48 to –0.6; I2 = 16.2%) was observed.34,35 For eversion, the pooled results of active JPR showed a large effect of deficits (SMD = 4.82; I2 = 87.9%),54,57,58 whereas the pooled results of passive JPR showed no significant difference (SMD = 0.37, I2 = 12.4%)23,59 (Fig. 5B). For plantarflexion, the pooled results of both active JPR (SMD = 1.71, I2 = 97.5%) and passive JPR (SMD = 0.07, I2 = 81.9%) showed no significant difference23,54,55,57, 58, 59 (Fig. 5C). For dorsiflexion, the pooled results of both active JPR (SMD = 1.27, I2 = 95.8%) and passive JPR (SMD = 0.15, I2 = 20.2%) also showed no significant difference23,54,57, 58, 59 (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5.

Joint position sense compared with healthy people in (A) inversion, (B) eversion, (C) plantarflexion, and (D) dorsiflexion. Positive SMD indicates kinesthesia deficits in the injured ankle. a Percentage of individual maximal movement angles in each subject. CI = confidence interval; JPR = joint position reproduction test; SMD = standardized mean difference.

As for the studies with different units, the study with VE did not find a significant difference in inversion (SMD = 0.24, 95%CI: –0.63 to 1.11) or plantarflexion (SMD = 0.23, 95%CI: –0.64 to 1.1).55 One study with CE also did not find a significant difference in inversion (SMD = –0.38, 95%CI: –0.79 to 0.02).60 One study with mean reproduced angle showed a significant difference in inversion (SMD = 0.37, 95%CI: 0.06–0.67) and plantarflexion (SMD = –0.31, 95%CI: –0.62 to –0.01), but not in eversion (SMD = 0.29, 95%CI: –0.01 to 0.59) or dorsiflexion (SMD = –0.05, 95%CI: –0.25 to 0.35).24 One study using indirectly measured movement analysis found a significant difference in eversion (SMD = 1.46, 95%CI: 0.55–2.37), plantarflexion (SMD = 0.89, 95%CI: 0.05–1.74), and dorsiflexion (SMD = 1.10, 95%CI: 0.24–1.97) but not in inversion (SMD = 0.79, 95%CI: –0.05 to 1.62).61

3.3.5. Knee and shoulder proprioception

Two studies investigated the proprioception in the knee with JPR tests of knee flexion. One with VE found a significant difference (SMD = 1.27, 95%CI: 0.79–1.74 and SMD = 1.42, 95%CI: 0.31–2.54, between limbs and groups, respectively),28 whereas the other study with AE showed no significant difference between groups (SMD = 0.07, 95%CI: –0.46 to 0.6).62 One study of the shoulder with an external JPR test showed no significant difference between groups (SMD = –0.41, 95%CI: –1.16 to 0.34 and SMD = –0.38, 95%CI: –1.13 to 0.37, for the right and left sides, respectively). 63

3.4. Sensitivity analysis

For the potential source of high heterogeneity, the I2 of active inversion JPS between limbs turned from 81.5% to 0 when the study by Sousa et al.21 was removed. The heterogeneity in other analyses could not be explained by individual studies. For the stability of the analyses, the pooled results of active JPR in plantarflexion between limbs became significant when the study by Saavedra-Miranda et al.52 was removed (SMDremoved = 1.08, 95%CI: 0.15–2.01), and the pooled results of passive JPR in plantarflexion between limbs become insignificant when the study by Hanci et al.45 was removed (SMDremoved = 0.54, 95%CI: –0.09 to 1.16). The other analyses were unaffected by altering individual studies.

4. Discussion

The most important finding of this review was that the deficits of proprioception (JPS and kinesthesia) did exist in the ankles of patients with CAI and varied according to the differing test methodologies. An overview of the meta-analysis shows that kinesthesia, passive and active JPS of ankle inversion, and kinesthesia of ankle plantarflexion were impaired in CAI when compared with the uninjured contralateral side. Kinesthesia and active JPS of ankle inversion and eversion were impaired in CAI when compared with healthy controls.

Proprioceptive information is critical for the central nervous system to control both basic and skilled movements.15 For example, when an individual walks on an uneven road, kinesthesia can detect the potential changes of movements and adjust the motor plan properly, and JPS can help to turn the joints into a more suitable position before each touchdown, thus avoiding instability.64 For the morphological bases, Ruffini endings and Pacinian corpuscles (within the joint corpuscles and ligaments) contribute to JPS and kinesthesia, respectively, and muscle spindle is thought to play an important role in both of them.65,66 For the mechanism of deficits, sprain accidents could lead to tears of ligaments and muscles and damage the articular receptors and muscle spindles.16,17 In addition, the inflammation and edema after the injuries could also lead to partial deafferentation and influence the functions of proprioceptive receptors.16,17 Because the sensory inputs are altered, the motor outputs (including reflections and voluntary movements) are also altered, which could lead to function losses.16,67

4.1. Ankle kinesthesia

The earliest measurement of kinesthesia in CAI was the judgment of movement, and then TTDPM was widely applied.33,43 The only previous review of kinesthesia in CAI found a weak deficit between groups, but the review mixed movement directions and lacked available studies to synthesize.11 The results of our review indicated impaired kinesthesia, with weak effect in inversion and large effect in plantarflexion when compared with contralateral limb, and moderate effects in inversion and eversion when compared with healthy people. Although the test velocities varied among the studies, all of the included studies were highly homogeneous, and the results proved to be stable in our sensitivity analysis.

4.2. Ankle joint position sense

JPR was the most common test method for JPS.32 For the JPS between limbs, only the study by Mckeon and Mckeon26 revealed a significant deficit in CAI, but it mixed the movement directions. In this study, a large effect of active JPS deficit and a moderate effect of passive JPS deficit was observed in inversion, and the sensitivity analysis revealed that the high heterogeneity within this analysis came mainly from the study by Sousa et al.21 The potential reason might be that the measurement by Sousa et al.21 applied an additional supination to avoid the sensory input from joint receptors. As for plantarflexion, the large effect of passive JPS deficit proved to be unstable by sensitivity analysis and should be interpreted with caution.

For the JPS between groups, the previous study by Munn et al.19 indicated significant deficits in both passive and active JPS, while different directions were mixed. As for the study by Hiller et al.,12 the lack of available studies and the enrolment of bilaterally injured patients might have contributed to the insignificance between groups. To address these problems, our study analyzed the JPS in different directions separately and excluded the potential bilateral CAI patients. Our results indicated a large effect of impaired active JPS in inversion and eversion, which proved to be stable in our sensitivity analysis.

Contrary to the JPR test that tried to minimize confounders by using a non-weight-bearing posture and blocked vision, AMEDA was a newly developed measurement for evaluating active JPS and aimed to provide a natural condition for JPS evaluation.15,35 The result of pooled 2 studies by Witchalls et al.34,35 showed a large effect of JPS deficits in inversion with low heterogeneity, which suggested a potential application value in the evaluation of JPS in CAI.

4.3. Proprioception of other joints

For the secondary outcome of this review, the proprioception of other joints was also evaluated. Inconsistent results were observed in the 2 studies of the knee and 1 study of the shoulder.28,62,63 The evidence was not strong enough to conclude that the proprioception of joints other than the ankle in CAI was different from controls.28,62,63 Because deficits of other kinematics beyond the ankle, such as the strength of muscles around the knee, had been reported in CAI, testing whether the proprioception of joints other than the ankle might provide more information about the development and mechanisms at play in CAI.18,27,68 Further research on this issue is needed.

4.4. Clinical implications

Our study provides evidence that patients with CAI have impaired ankle proprioception, which highlights the importance of detailed measurements and targeted interventions into proprioceptive inputs in the clinical management of CAI. However, although proprioception deficits have been widely accepted as an important factor in functional loss in ligament injuries, some researchers still question the clinical meanings of these changes.17,69 During competitive sports, vision is occupied by targets, and attention demands are increased in order to manage skilled performance, so the central nervous system relies more on proprioceptive sources through central reweighting, and the influence of deficits is enlarged.68,70,71 Therefore, even a small deficit should not be overlooked in the management of sports injuries.

For interventions, although the ankle proprioceptive input is partially impaired by the initial injury, the overall proprioceptive performance also depends on the ability of the central nervous system to use other sensory inputs, including vision and other proprioception, which could, theoretically, be trained through learning and neuroplasticity mechanisms.30,68 Most of the current rehabilitation strategies for CAI, such as manual therapies and exercise therapies, are based on the training of non-specific balance rather than the specific sensory (e.g., kinesthesia and JPS), which might lead to a lower efficiency.72,73 We believe that, based on our results, more efficient interventions in kinesthesia and JPS can be developed for targeted CAI management.

4.5. Research implications

First, AMEDA is recommended for future studies because it simulates a more natural condition of exercise than traditional proprioception tests.15,69 Second, obvious differences between various comparison types were observed in this study, which indicates that the proprioception of the uninjured contralateral ankle might be different from that in healthy people. Some studies have reported on the bilateral influence of unilateral injuries,74 which could also exist in proprioceptive processing. Further exploration is needed.

4.6. Study limitations

There are some limitations to our study that should be acknowledged. First, the relationship between the test results and details, such as movement velocities and target angles, were not analyzed further due to the lack of available studies. Second, methodological quality and non-English studies were not considered for inclusion in our study. However, the low heterogeneities and the stability of the pooled results in our sensitivity tests supported the idea that these 2 shortages would not have influenced the reliability of our conclusions.26,27 Third, we applied a broader definition of CAI than is recommended by the International Ankle Consortium, but the individuals with ankle sprain histories and residual symptoms were representative enough for CAI, according to previous research.5,7,75

5. Conclusion

The main findings from this study indicate that kinesthesia, passive and active JPS of ankle inversion, and kinesthesia of ankle plantarflexion are impaired in CAI when compared with uninjured contralateral limbs, and kinesthesia and active JPS of ankle inversion and eversion are impaired in CAI when compared with healthy controls.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81871823). The authors gratefully acknowledge the help of Ximan Li from Beijing Sport University, Beijing, China, in conducting the literature search.

Authors’ contributions

XX carried out the study design, literature search and selection, data collection, quality rating, statistical analysis, and manuscript writing; TM carried out the study design, literature search and selection, data collection, quality rating, and manuscript reviewing; QL and YS carried out the study design and manuscript reviewing; YH carried out the study design, supervision of the literature search, data collection, quality rating, and manuscript reviewing. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript, and agree with the order of presentation of the authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Shanghai University of Sport.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.jshs.2020.09.014.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Fong DTP, Hong Y, Chan LK, Yung PSH, Chan KM. A systematic review on ankle injury and ankle sprain in sports. Sport Med. 2007;37:73–94. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200737010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yeung MS, Chan KM, So CH, Yuan WY. An epidemiological survey on ankle sprain. Br J Sports Med. 1994;28:112–116. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.28.2.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soboroff SH, Pappius EM, Komaroff AL. Benefits, risks, and costs of alternative approaches to the evaluation and treatment of severe ankle sprain. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1984;183:160–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anandacoomarasamy A, Barnsley L. Long-term outcomes of inversion ankle injuries. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39:e4. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2004.011676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gribble PA, Delahunt E, Bleakley C. Selection criteria for patients with chronic ankle instability in controlled research: a position statement of the International Ankle Consortium. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48:1014–1018. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-093175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doherty C, Bleakley C, Delahunt E, Holden S. Treatment and prevention of acute and recurrent ankle sprain: an overview of systematic reviews with meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51:113–125. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Song Y, Li H, Sun C. Clinical guidelines for the surgical management of chronic lateral ankle instability: a consensus reached by systematic review of the available data. Orthop J Sport Med. 2019;7 doi: 10.1177/2325967119873852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li HY, Zheng JJ, Zhang J, Cai YH, Hua YH, Chen SY. The improvement of postural control in patients with mechanical ankle instability after lateral ankle ligaments reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24:1081–1085. doi: 10.1007/s00167-015-3660-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li HY, Zheng JJ, Zhang J, Hua YH, Chen SY. The effect of lateral ankle ligament repair in muscle reaction time in patients with mechanical ankle instability. Int J Sports Med. 2015;36:1027–1032. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1550046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen H, Li HY, Zhang J, Hua YH, Chen SY. Difference in postural control between patients with functional and mechanical ankle instability. Foot Ankle Int. 2014;35:1068–1074. doi: 10.1177/1071100714539657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thompson C, Schabrun S, Romero R, Bialocerkowski A, van Dieen J, Marshall P. Factors contributing to chronic ankle instability: a systematic review and meta-analysis of systematic reviews. Sports Med. 2018;48:189–205. doi: 10.1007/s40279-017-0781-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hiller CE, Nightingale EJ, Lin CWC, Coughlan GF, Caulfield B, Delahunt E. Characteristics of people with recurrent ankle sprains: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45:660–672. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2010.077404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freeman MA, Dean MR, Hanham IW. The etiology and prevention of functional instability of the foot. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1965;47:678–685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sherrington CS. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1906. The integrative action of the nervous system. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han J, Waddington G, Adams R, Anson J, Liu Y. Assessing proprioception: a critical review of methods. J Sport Health Sci. 2016;5:80–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jshs.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Needle AR, Lepley AS, Grooms DR. Central nervous system adaptation after ligamentous injury: a summary of theories, evidence, and clinical interpretation. Sports Med. 2017;47:1271–1288. doi: 10.1007/s40279-016-0666-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim HJ, Lee JH, Lee DH. Proprioception in patients with anterior cruciate ligament tears: a meta-analysis comparing injured and uninjured limbs. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45:2916–2922. doi: 10.1177/0363546516682231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Witchalls J, Blanch P, Waddington G, Adams R. Intrinsic functional deficits associated with increased risk of ankle injuries: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46:515–523. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Munn J, Sullivan SJ, Schneiders AG. Evidence of sensorimotor deficits in functional ankle instability: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J Sci Med Sport. 2010;13:2–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marinho HVR, Amaral GM, de Souza Moreira B. Influence of passive joint stiffness on proprioceptive acuity in individuals with functional instability of the ankle. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2017;47:899–905. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2017.7030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sousa ASP, Leite J, Costa B, Santos R. Bilateral proprioceptive evaluation in individuals with unilateral chronic ankle instability. J Athl Train. 2017;52:360–367. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-52.2.08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cho BK, Park JK. Correlation between joint-position sense, peroneal strength, postural control, and functional performance ability in patients with chronic lateral ankle instability. Foot Ankle Int. 2019;40:961–968. doi: 10.1177/1071100719846114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nanbancha A, Tretriluxana J, Limroongreungrat W, Sinsurin K. Decreased supraspinal control and neuromuscular function controlling the ankle joint in athletes with chronic ankle instability. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2019;119:2041–2052. doi: 10.1007/s00421-019-04191-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee JH, Lee SH, Choi GW, Jung HW, Jang WY. Individuals with recurrent ankle sprain demonstrate postural instability and neuromuscular control deficits in unaffected side. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2020;28:184–192. doi: 10.1007/s00167-018-5190-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang YW, Wu HW. Effect of cryotherapy on ankle proprioception and balance in subjects with chronic ankle instability. Isokinet Exerc Sci. 2017;25:143–148. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mckeon JMM, Mckeon PO. Evaluation of joint position recognition measurement variables associated with chronic ankle instability: a meta-analysis. J Athl Train. 2012;47:444–456. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-47.4.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khalaj N, Vicenzino B, Heales LJ, Smith MD. Is chronic ankle instability associated with impaired muscle strength? Ankle, knee and hip muscle strength in individuals with chronic ankle instability: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54:839–847. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2018-100070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsiganos G, Kalamvoki E, Smirniotis J. Effect of the chronically unstable ankle on knee joint position sense. Isokinet Exerc Sci. 2008;16:75–79. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Röijezon U, Clark NC, Treleaven J. Proprioception in musculoskeletal rehabilitation: Part 1: Basic science and principles of assessment and clinical interventions. Man Ther. 2015;20:368–377. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2015.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Refshauge KM, Kilbreath SL, Raymond J. Deficits in detection of inversion and eversion movements among subjects with recurrent ankle sprains. J Orthop Sport Phys Ther. 2003;33:166–173. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2003.33.4.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goble DJ. Proprioceptive acuity assessment via joint position matching: from basic science to general practice. Phys Ther. 2010;90:1176–1184. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20090399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sefton JM, Hicks-Little CA, Hubbard TJ. Sensorimotor function as a predictor of chronic ankle instability. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2009;24:451–458. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Witchalls JB, Waddington G, Adams R, Blanch P. Chronic ankle instability affects learning rate during repeated proprioception testing. Phys Ther Sport. 2014;15:106–111. doi: 10.1016/j.ptsp.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Witchalls J, Waddington G, Blanch P, Adams R. Ankle instability effects on joint position sense when stepping across the active movement extent discrimination apparatus. J Athl Train. 2012;47:627–634. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-47.6.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Genaidy AM, LeMasters GK, Lockey J. An epidemiological appraisal instrument: a tool for evaluation of epidemiological studies. Ergonomics. 2007;50:920–960. doi: 10.1080/00140130701237667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reeves BC, Deeks JJ, Higgins JPT, Wells GA. Including non- randomized studies. In: Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Wiley-Blackwell; Chichester: 2008. pp. 391–432. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hart HF, Culvenor AG, Collins NJ. Knee kinematics and joint moments during gait following anterior cruciate ligament econstruction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50:597–612. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-094797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cohen J. Lawrence Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1988. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rothstein HR, Sutton AJ, Borenstein M. Comparison of two methods to detect publication bias in meta-analysis. Publ Bias Meta-Analysis Prev Assess Adjust. 2006;295:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gross MT. Effects of recurrent lateral ankle sprains on active and passive judgments of joint position. Phys Ther. 1987;67:1505–1509. doi: 10.1093/ptj/67.10.1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lentell G, Baas B, Lopez D, McGuire L, Sarrels M, Snyder P. The contributions of proprioceptive deficits, muscle function, and anatomic laxity to functional instability of the ankle. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1995;21:206–215. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1995.21.4.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hanci E, Sekir U, Gur H, Akova B. Eccentric training improves ankle evertor and dorsiflexor strength and proprioception in functionally unstable ankles. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;95:448–458. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000000421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Konradsen L, Olesen S, Hansen HM. Ankle sensorimotor control and eversion strength after acute ankle inversion injuries. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26:72–77. doi: 10.1177/03635465980260013001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nakasa T, Fukuhara K, Adachi N, Ochi M. The deficit of joint position sense in the chronic unstable ankle as measured by inversion angle replication error. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2008;128:445–449. doi: 10.1007/s00402-007-0432-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sekir U, Yildiz Y, Hazneci B, Ors F, Aydin T. Effect of isokinetic training on strength, functionality and proprioception in athletes with functional ankle instability. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15:654–664. doi: 10.1007/s00167-006-0108-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Santos MJ, Liu W. Possible factors related to functional ankle instability. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008;38:150–157. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2008.2524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cho BK, Hong SH, Jeon JH. Effect of lateral ligament augmentation using suture-tape on functional ankle instability. Foot Ankle Int. 2019;40:447–456. doi: 10.1177/1071100718818554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yokoyama S, Matsusaka N, Gamada K, Ozaki M, Shindo H. Position-specific deficit of joint position sense in ankles with chronic functional instability. J Sports Sci Med. 2008;7:480–485. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saavedra-Miranda M, Méndez-Rebolledo G. Measurement and relationships of proprioceptive isokinetic repositioning, postural control, and a self-reported questionnaire in patients with chronic ankle instability. Isokinet Exerc Sci. 2016;25:33–39. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Konradsen L, Magnusson P. Increased inversion angle replication error in functional ankle instability. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2000;8:246–251. doi: 10.1007/s001670000124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.You SH, Granata KP, Bunker LK. Effects of circumferential ankle pressure on ankle proprioception, stiffness, and postural stability: a preliminary investigation. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2004;34:449–460. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2004.34.8.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sefton JM, Yarar C, Hicks-Little CA, Berry JW, Cordova ML. Six weeks of balance training improves sensorimotor function in individuals with chronic ankle instability. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2011;41:81–89. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2011.3365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Iwao K, Masataka D, Kohei F. Surgical reconstruction with the remnant ligament improves joint position sense as well as functional ankle instability: a 1-year follow-up study. Sci World J. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/523902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim CY, Choi JD, Kim HD. No correlation between joint position sense and force sense for measuring ankle proprioception in subjects with healthy and functional ankle instability. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2014;29:977–983. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2014.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kim CY, Choi JD. Comparison between ankle proprioception measurements and postural sway test for evaluating ankle instability in subjects with functional ankle instability. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2016;29:97–107. doi: 10.3233/BMR-150603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brown CN, Ross SE, Mynark R, Guskiewicz KM. Assessing functional ankle instability with joint position sense, time to stabilization, and electromyography. J Sport Rehabil. 2004;13:122–134. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lim ECW, Tan MH. Side-to-side difference in joint position sense and kinesthesia in unilateral functional ankle instability. Foot Ankle Int. 2009;30:1011–1017. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2009.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lin CH, Chiang SL, Lu LH, Wei SH, Sung WH. Validity of an ankle joint motion and position sense measurement system and its application in healthy subjects and patients with ankle sprain. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2016;131:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2016.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Navarro-Santana MJ, Albert-Lucena D, Gomez-Chiguano GF. Pressure pain sensitivity over nerve trunk areas and physical performance in amateur male soccer players with and without chronic ankle instability. Phys Ther Sport. 2019;40:91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ptsp.2019.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Springer S, Gottlieb U, Moran U, Verhovsky G, Yanovich R. The correlation between postural control and upper limb position sense in people with chronic ankle instability. J Foot Ankle Res. 2015;8:23. doi: 10.1186/s13047-015-0082-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Proske U, Gandevia SC. The proprioceptive senses: their roles in signaling body shape, body position and movement, and muscle force. Physiol Rev. 2012;92:1651–1697. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00048.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wu X, Song W, Zheng C, Zhou S, Bai S. Morphological study of mechanoreceptors in collateral ligaments of the ankle joint. J Orthop Surg Res. 2015;10:92. doi: 10.1186/s13018-015-0215-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bali K, Dhillon MS, Vasistha RK, Kakkar N, Chana R, Prabhakar S. Efficacy of immunohistological methods in detecting functionally viable mechanoreceptors in the remnant stumps of injured anterior cruciate ligaments and its clinical importance. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20:75–80. doi: 10.1007/s00167-011-1526-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kapreli E, Athanasopoulos S. The anterior cruciate ligament deficiency as a model of brain plasticity. Med Hypotheses. 2006;67:645–650. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2006.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Han J, Anson J, Waddington G, Adams R, Liu Y. The role of ankle proprioception for balance control in relation to sports performance and injury. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/842804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gokeler A, Benjaminse A, Hewett TE. Proprioceptive deficits after ACL injury: are they clinically relevant? Br J Sports Med. 2012;46:180–192. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2010.082578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Williams AM, Davids K, Williams JG. Routledge; Eastbourne: 1999. Visual perception and action in sport. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Han J, Waddington G, Anson J, Adams R. Level of competitive success achieved by elite athletes and multi-joint proprioceptive ability. J Sci Med Sport. 2015;18:77–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2013.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Clark NC, Röijezon U, Treleaven J. Proprioception in musculoskeletal rehabilitation. Part 2: Clinical assessment and intervention. Man Ther. 2015;20:378–387. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2015.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tsikopoulos K, Mavridis D, Georgiannos D, Vasiliadis HS. Does multimodal rehabilitation for ankle instability improve patients’ self-assessed functional outcomes? A network meta-analysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2018;476:1295–1310. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000534691.24149.a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Heales LJ, Lim ECW, Hodges PW, Vicenzino B. Sensory and motor deficits exist on the non-injured side of patients with unilateral tendon pain and disability: implications for central nervous system involvement: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48:1400–1406. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hiller CE, Kilbreath SL, Refshauge KM. Chronic ankle instability: evolution of the model. J Athl Train. 2011;46:133–141. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-46.2.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.