Summary

Locomotion creates various patterns of optic flow on the retina, which provide the observer with information about their movement relative to the environment. However, it is unclear how these optic flow patterns are encoded by the cortex. Here, we use two-photon calcium imaging in awake mice to systematically map monocular and binocular responses to horizontal motion in four areas of the visual cortex. We find that neurons selective to translational or rotational optic flow are abundant in higher visual areas, whereas neurons suppressed by binocular motion are more common in the primary visual cortex. Disruption of retinal direction selectivity in Frmd7 mutant mice reduces the number of translation-selective neurons in the primary visual cortex and translation- and rotation-selective neurons as well as binocular direction-selective neurons in the rostrolateral and anterior visual cortex, blurring the functional distinction between primary and higher visual areas. Thus, optic flow representations in specific areas of the visual cortex rely on binocular integration of motion information from the retina.

Keywords: visual cortex, retina, direction-selective cells, optic flow, translation, rotation, two-photon calcium imaging, intrinsic signal optical imaging

Highlights

-

•

Translation- and rotation-selective neurons are abundant in higher visual areas

-

•

Optic-flow-selective neurons in V1 and RL/A rely on retinal direction selectivity

-

•

Retinal direction selectivity controls functional segregation between V1 and RL/A

-

•

Binocular integration of retinal motion information underlies optic flow selectivity

Locomotion creates different patterns of optic flow, but how these are encoded by the cortex is unclear. By mapping cortical activity in awake mice, Rasmussen et al. demonstrate that binocular integration of retinal motion direction selectivity causally influences optic flow selectivity of neurons residing in distinct areas of the visual cortex.

Introduction

The action of moving through an environment produces patterns of visual motion, known as optic flow, on the retina, which animals rely on to guide their behavior. Animal locomotion is largely described by a combination of forward-backward movements and left-right turning. Forward and backward movements induce translational optic flow (nasal-to-temporal or temporal-to-nasal motion in both eyes, respectively), whereas turning induces rotational optic flow (nasal-to-temporal motion in one eye and temporal-to-nasal in the other; Figures 1A and 1B). However, despite the increasing use of mice to study vision, it is unknown how these distinct optic flow patterns are encoded by the rodent cortex.

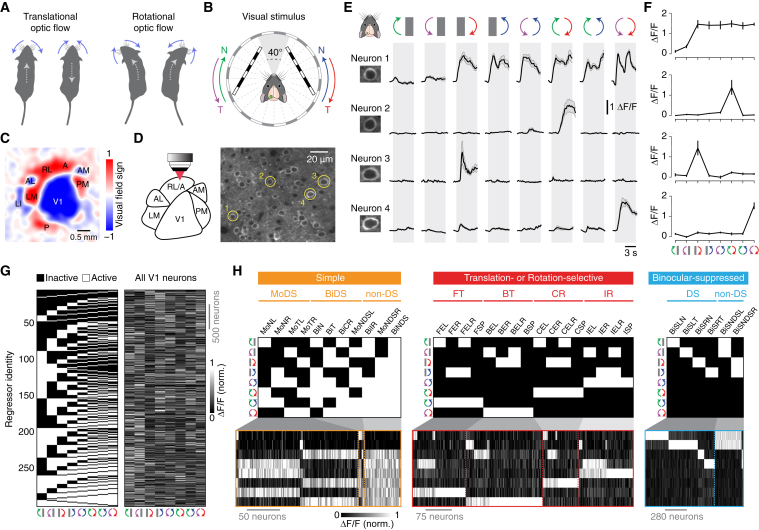

Figure 1.

Discrete neuronal responses to motion stimuli in monocular visual fields can be imaged in the visual cortex of awake mice

(A) Diagram illustrating optic flow patterns induced by self-motion. Forward and backward movements induce translational optic flow (left), and leftward and rightward turns induce rotational optic flow (right). Blue arrows indicate the dominant apparent motions in the visual space surrounding the mouse; gray dotted arrows indicate direction of locomotion.

(B) Diagram of the visual stimulus setup. Spherically corrected gratings moved in either nasal (N) or temporal (T) directions (10°/s or 40°/s with 0.03 cycles/°). The stimulus was not displayed in the binocular visual field (frontal 40°) to ensure stimulation of only the monocular visual fields. Imaging was performed in the visual cortex of the left hemisphere.

(C) Visual field sign map obtained with intrinsic signal optical imaging showing the location of visual cortical areas.

(D) (Left) Two-photon imaging was performed from identified visual cortical areas. (Right) Example image of GCaMP6f-expressing neurons in layer 2/3 of V1 is shown.

(E) Example trial-averaged fluorescence intensity (ΔF/F) time courses for the neurons highlighted in (D) in response to monocular and binocular motion at 10°/s. Error bars are mean ± SEM.

(F) Tuning curves of the neurons in (E). Error bars are mean ± SEM.

(G) (Left) Map of all 256 regressors. (Right) Response matrix of the tuning curves for all consistently responsive V1 neurons is shown.

(H) Regressor profiles and tuning curves for V1 neurons assigned to functional groups within the simple, translation- or rotation-selective, and binocular-suppressed response classes.

BiDS, binocular DS; BiS, binocular suppressed; BT, backward translational; CR, contraversive rotational; E, excited by; FT, forward translational; IR, ipsiversive rotational; L, left eye; MoDS, monocular DS; N, nasalward; NDS, non-DS; R, right eye; SP, specific; T, temporalward. See also Table S1, Figures S1–S4, and Video S1.

An extensive body of research has shown that neurons residing in brain areas involved in optic flow processing have complex receptive fields, often receive binocular inputs, and respond to both translational and rotational optic flow stimuli. Examples include the fly lobula plate (involved in course control),1,2 the zebrafish pretectal nuclei,3,4 the avian and mammalian accessory optic system (involved in gaze stabilization),5,6 and both the dorsomedial region of the medial superior temporal area and posterior parietal cortex (PPC) of monkeys (involved in spatial navigation).7, 8, 9 The mouse visual cortex contains a primary visual cortex (V1) and more than a dozen distinct higher visual areas (HVAs), each with unique sensitivities to visual features.10,11 The V1 receives retinal inputs via the lateral geniculate nucleus and distributes functionally specialized signals to different HVAs.12, 13, 14 Based on their anatomy, multi-sensory processing, and roles in spatial navigation, the rostrolateral (RL), anterior (A), and anteromedial (AM) HVAs are considered part of the PPC in mice,15, 16, 17, 18 raising the possibility that they contain neurons sensitive to binocular optic flow.

In rodents, visual motion computations are not exclusive to the cortex and start in the retina. The retina contains mosaic arrangements of direction-selective (DS) cells that preferentially respond to motion in one of the four cardinal directions (nasal, temporal, dorsal, and ventral).19, 20, 21 These cells fall into two canonical classes: ON DS cells (which project to the nuclei of the accessory optic system and mediate the optokinetic reflex) and ON-OFF DS cells (which project to the lateral geniculate nucleus and the superior colliculus).19,21, 22, 23 Although the role of ON DS cells for mediating gaze-stabilizing eye movements is well established, the functional role of ON-OFF DS cells is unclear. The Frmd7 mutant mouse (Frmd7tm), a model of congenital nystagmus,24 is a valuable experimental tool for studying the contribution of ON-OFF DS cells to visual cortical processing. Importantly, this mouse is characterized by impaired horizontal direction selectivity in both ON and ON-OFF DS cells, as a result of transition from asymmetric to symmetric inhibitory inputs from starburst amacrine cells.24 At this time, a handful of studies have tested cortical activity in response to monocular visual motion stimulation in the Frmd7tm mouse.13,25,26 One study found that a specific form of direction selectivity in layer 2/3 of V1, tuned to higher stimulus speeds and with a preference to posterior motion, was disrupted in Frmd7tm mice.25 Subsequent work expanded on this finding by showing that responses to posterior motion in layer 2/3 of the RL area, but not in the posteromedial (PM) area or layer 4 of V1, is also affected in this mouse.13 These data are suggestive of a segregated cortical pathway for processing signals originating from horizontally tuned ON-OFF DS cells. What might be the functional role of such a visual motion processing stream from the retina to the cortex? An intriguing hypothesis is that information from ON-OFF DS cells in the left and right eyes is systematically integrated in the cortex to create areas with distinct sensitivity to translational and rotational optic flow patterns.21,27 However, this has yet to be experimentally tested, and the cortical areas that might combine optic flow information from the left and right eyes remain unknown.

Here, we systematically map the responses of individual neurons across the visual cortex using two-photon calcium imaging during monocular and binocular optic flow stimulation within the monocular visual field of awake mice. We test the contribution of retinal horizontal direction selectivity to visual cortical activity using the Frmd7tm mice.13,24,25 Our data demonstrate that the mouse visual cortex contains an abundance of neurons that encode translational or rotational optic flow. Furthermore, our results suggest that information from retinal DS cells in each eye is integrated in the cortex as early as in V1, where it establishes response selectivity to backward translational optic flow, but that binocular retinal DS signaling for establishing selectivity to rotational optic flow is first integrated in the higher areas RL and A. These results support the hypothesis that retinal ON-OFF DS cell mosaics are specialized for detecting translational and rotational optic flow.27

Results

Discrete neuronal responses to monocular and binocular motion stimuli can be imaged in the visual cortex of awake mice

To identify individual areas of mouse visual cortex, we used intrinsic signal optical imaging.13,28 We first generated visual field sign maps from retinotopic maps, allowing us to identify V1 as well as the higher areas RL, A, AM, and PM (Figures 1C and S1). We chose to combine areas RL and A (RL/A), as these areas could not be clearly distinguished from each other in our dataset.10,29 For binocular animals to reliably detect different optic flow patterns, the brain must integrate motion signals from each eye. We therefore investigated the neuronal responses underlying binocular optic flow processing by presenting moving gratings to mice using a stimulus protocol that tests the repertoire of horizontal motions.3 The eight stimulus conditions in the protocol were generated by presenting gratings moving in a nasal or temporal direction to one eye at a time and then to both eyes to simulate the rotational (ipsiversive and contraversive) or translational (forward and backward) optic flow that the mouse would experience during locomotion (Figures 1A and 1B; Video S1; see STAR methods). To unambiguously probe the interaction of left and right retinal information in the cortex, the stimuli were presented only to the monocular visual fields and not to the frontal binocular visual field (Figure 1B). Our stimulus protocol did not effectively trigger the optokinetic reflex (Figure S2), likely due to the use of a low spatial frequency (0.03 cycles/°).30

Animation showing the visual stimulus protocol we employed for testing the full horizontal motion repertoire. This consisted of eight conditions, in which spherically corrected sinusoidal moving gratings were first presented to one eye at a time in either the nasal or temporal direction, and then presented to both eyes, mimicking the rotational (ipsiversive and contraversive) and translational (forward and backward) optic flow that the mouse would experience during locomotion (i.e., forward-backward straight movements and left-right turning). The mouse’s binocular visual field (central 40°) did not contain the visual stimulus, to ensure only stimulation of the monocular visual field. This animation shows the gratings moving at 10°/s (spatial frequency, 0.03 cycles/°).

The tuning properties of individual layer 2/3 neurons were characterized in awake mice by transfecting cortical neurons with the genetically encoded calcium sensor GCaMP6f (expression driven by the synapsin promoter) and measuring changes in two-photon fluorescence during stimulus presentation (Figures 1D and 1E). A typical field of view contained ∼100−150 neurons, and somatic calcium responses showed diverse but consistent patterns, depending on the eye being stimulated and the direction of motion (Figure 1E). Tuning curves for individual neurons were generated by plotting trial-averaged fluorescence changes as a function of stimulus conditions (Figure 1F). We systematically classified neurons into distinct functional types according to their tuning curves using regressor-correlation analysis.3 First, we generated a regressor map consisting of all possible all-or-none response combinations to the eight stimulus conditions, which resulted in 256 profiles (Figure 1G; see STAR methods). Next, the tuning curve for each neuron was assigned to the regressor with the highest correlation (Figures S3A–S3C). All tuning curves had high correlations with their assigned regressor (mean correlation coefficient; 0.91 ± 0.05; n = 26,712 neurons from 17 mice). These data confirm that we can reliably elicit responses to monocular and binocular motion stimuli, presented within the monocular visual field, in the visual cortex of awake mice and also robustly classify neurons into discrete response types.

The RL/A area of the visual cortex is enriched with optic-flow-selective neurons

We sought to investigate the response specificity of visual cortex neurons by sampling thousands of consistently responsive neurons in multiple areas of the visual cortex of nine mice (3,010 in V1, 4,165 in RL/A, 4,006 in AM, and 3,059 in PM; Table S1) and assigning them to regressors (Figures 1G and S4). To characterize the monocular and binocular optic flow coding properties of these neurons, we initially focused on three response classes: simple; translation or rotation selective;3 and binocular suppressed (Figures 1H and 2). The simple class comprised three groups that were characterized by their direction selectivity: monocular DS; binocular DS; and non-DS neurons. Translation- and rotation-selective neurons comprised four groups that were characterized by their response selectivity to either forward translational, backward translational, contraversive rotational, or ipsiversive rotational optic flow (Figures 1A, 1H, and 2). Binocular-suppressed neurons were characterized by a suppressed response during binocular motion stimulation and were further divided according to their DS or non-DS responses to monocular motion (Figures 1H and 2; see STAR methods). Within these three classes, the majority of neurons assigned to the same regressor had similar Ca2+ response time courses across stimulus conditions, and correlation strength distributions were generally unimodal, indicating no clear sign of further neuronal subpopulations (Figures S3D and S3E), although we did note minor response variability within the same regressor, which could result from heterogeneous spatiotemporal receptive field properties of the sampled neurons. Thus, to fully resolve whether subsets of neurons may have distinct response time course kinetics to certain stimulus conditions, future work should exhaustively probe the spatiotemporal receptive field properties of neurons within the three response classes.

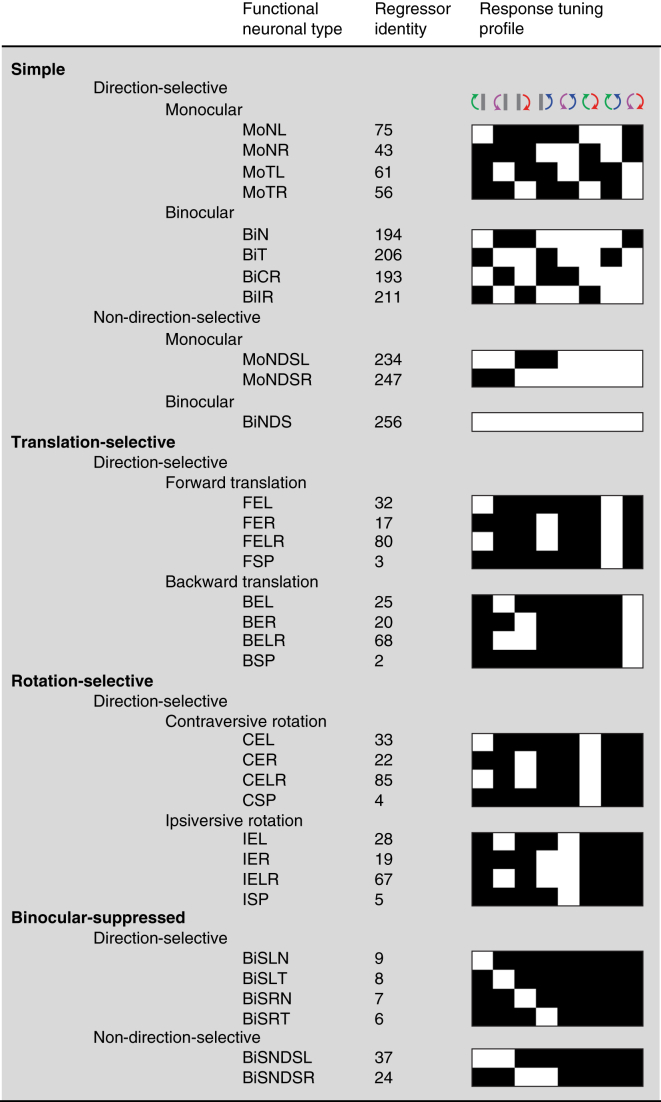

Figure 2.

Summary of response types and terminology

Figure providing an overview of the response classes, functional groups, and response types together with their corresponding regressor identity and response profile.

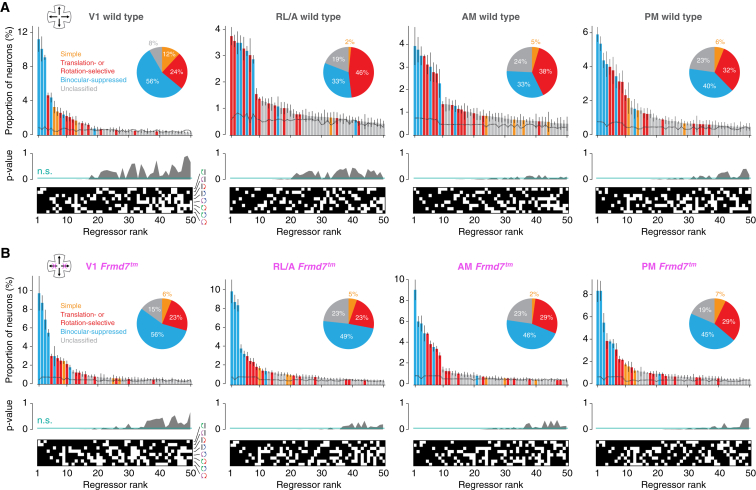

For all visual cortical areas, we counted neurons assigned to each regressor and ranked regressors according to their frequency (Figures 3A and S5). To identify significantly overrepresented regressors, we performed shuffling and bootstrap analyses (see STAR methods). Interestingly, in contrast to previous work in zebrafish,3 the most abundant neurons in V1 were binocular-suppressed neurons, which have been described in the primate V1.31 These neurons constituted as much as 38.6% of all responsive V1 neurons and 56% of the significantly overrepresented regressors (Figures 3A and S5B). In contrast, simple and translation- or rotation-selective neurons constituted only 8.8% and 19.7% of all responsive neurons, respectively. Neurons that could not be assigned to these three classes were considered unclassified and not investigated further.

Figure 3.

The RL/A area of the visual cortex is enriched with optic-flow-selective neurons in wild-type mice

Top: ranked distribution of the 50 most abundant response types and response classes in the V1, RL/A, AM, and PM areas of wild-type mice (A) and Frmd7tm mice with disrupted retinal direction selectivity along the horizontal axis (B). Dotted line denotes chance level obtained from averaging distributions from shuffled response profiles generated by bootstrapping (500 samples). Error bars are mean ± SEM. Middle: p values indicating the probability of proportions being higher in the shuffled than in the original dataset are shown. Values above the green line are not significant (n.s.) (p ≥ 0.05). Bottom: corresponding ranked regressor profiles are shown (white, active; black, inactive). Inset: pie chart shows proportion of neurons within response classes for the significantly overrepresented (p < 0.05) response types. See also Table S1 and Figures S3–S5.

The abundance of neuronal classes was different in the HVAs (Figure 3A). Translation- or rotation-selective neurons were the most abundant response class in the RL/A area—24% of all neurons and 46% of the significantly overrepresented regressors—whereas simple and binocular-suppressed neurons comprised only 2.5% and 14.8% of neurons, respectively. In area AM, translation- or rotation-selective neurons were again abundant and simple neurons were sparse (22.9% and 4% of neurons, respectively), but there was a higher proportion of binocular-suppressed neurons than in the RL/A area (17.8%). The PM area was characterized by an equal proportion of translation- or rotation-selective and binocular-suppressed neurons, constituting 24.4% and 25.3% of neurons, respectively.

These data establish that different areas of mouse visual cortex contain distinct distributions of monocular and binocular optic-flow-encoding neurons. In particular, the RL/A area is enriched with neurons encoding translational and rotational optic flow, whereas V1 is enriched with neurons activated by monocular motion but suppressed by binocular motion.

Retinal direction selectivity contributes to binocular optic flow processing in V1 and RL/A

To determine whether retinal direction selectivity contributes to the processing of optic flow in the visual cortex, we repeated our neuronal mapping in Frmd7 mutant (Frmd7tm) mice, which lack horizontal direction selectivity in the retina.13,24,25,26 Consistently responsive neurons were sampled in different areas of the visual cortex of eight mice (2,925 in V1, 3,125 in RL/A, 3,375 in AM, and 3,047 in PM; Table S1). This revealed a difference in the overall distribution of response classes in certain areas of Frmd7tm mice compared to wild-type mice (Figures 3A and 3B), which prompted us to examine the effects of direction selectivity on the proportions of monocular- and binocular-responsive neurons in each functional group or response type (Figures 4A–4D and S6A–S6D). In V1, the proportions of monocular DS and backward translation-selective neurons were reduced in Frmd7tm mice (Figure 4A). More strikingly, all groups of translation- or rotation-selective neurons, as well as binocular DS neurons, were reduced in the RL/A area of Frmd7tm mice (Figure 4B). In the AM area, only monocular and binocular DS neurons were reduced (Figure 4C). The proportion of DS and non-DS binocular-suppressed neurons was increased in both RL/A and AM areas of Frmd7tm mice (Figures 4B and 4C). Finally, none of the nine functional groups were significantly altered in the PM area of Frmd7tm mice (Figure 4D), underscoring previous work showing that motion processing in the PM area is independent of retinal DS signaling.13

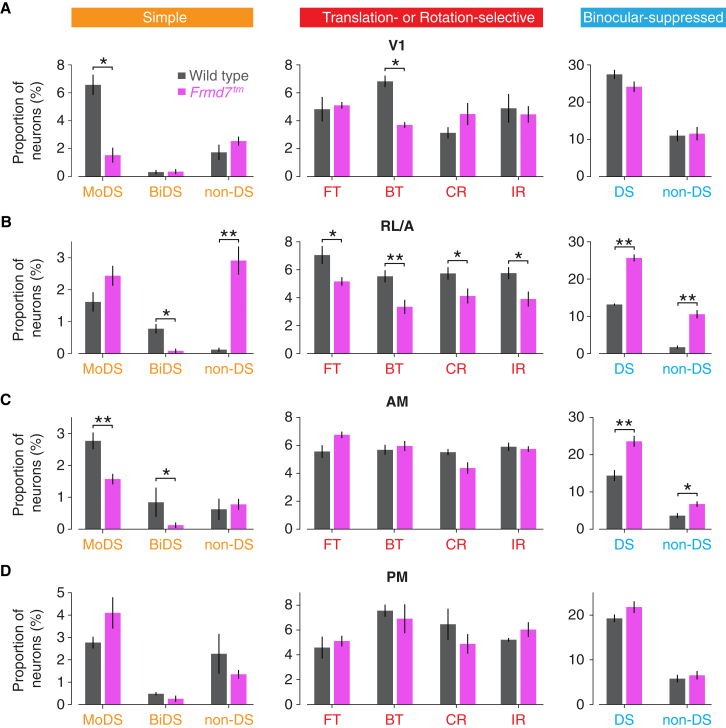

Figure 4.

Retinal direction selectivity contributes to optic-flow-selective responses in an area-specific manner

Proportion of V1 (A), RL/A (B), AM (C), and PM (D) neurons in simple, translation- or rotation-selective, and binocular-suppressed functional groups for wild-type and Frmd7tm mice. Error bars are mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; two-sided Mann-Whitney U test. See also Figure S6.

Together, these data show that simple and translation- or rotation-selective responses, but not binocular-suppressed responses, are impaired by disrupting retinal direction selectivity. Furthermore, we conclude that retinal direction selectivity contributes to binocular optic flow responses in the V1 and RL/A areas of the visual cortex.

Retinal direction selectivity establishes functional segregation between V1 and RL/A

Individual HVAs form distinct subnetworks, each of which represents a different information stream.10,32,33 We sought to find out how visual cortical areas are functionally organized with respect to their composition of optic-flow-sensitive neurons and whether retinal direction selectivity is involved in creating such an organization. To probe this, we used the mean proportion of neurons assigned to our functional response types to create an optic flow fingerprint for each visual area in wild-type and Frmd7tm mice and then we performed hierarchical clustering and correlation analyses (Figures 5A–5C; see STAR methods).

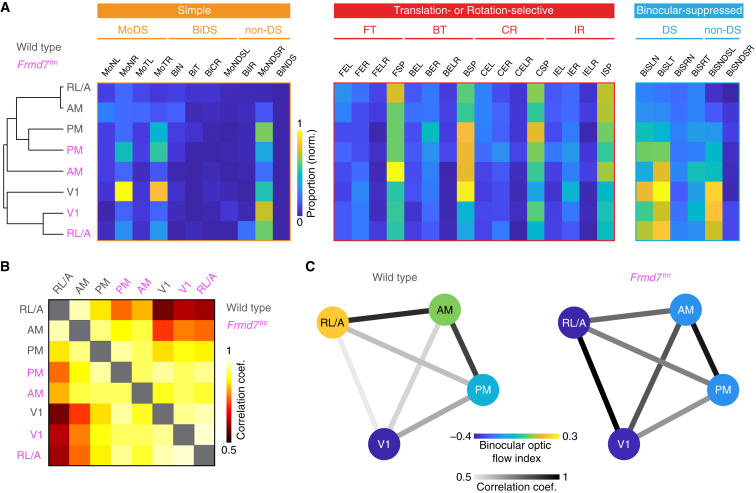

Figure 5.

Retinal direction selectivity establishes functional segregation between V1 and RL/A

(A) (Left) Hierarchy showing similarity in proportion of functional response types between visual areas in wild-type and Frmd7tm mice. (Right) Mean proportion of neurons in simple, translation- or rotation-selective, and binocular-suppressed functional response types between visual areas in wild-type and Frmd7tm mice is shown, sorted according to the similarity hierarchy (left).

(B) Correlation in functional response type proportions between visual areas and genetic groups.

(C) Diagram of the binocular optic flow index for each visual area, and the correlation in functional response type proportions between areas, in wild-type and Frmd7tm mice.

Hierarchical segregation (Figure 5A) together with a rather high correlation between optic flow representations (mean correlation coefficient, 0.81 ± 0.06; Figures 5B and 5C) were evident between the cortical areas of wild-type mice. In particular, V1 was noticeably separated from the RL/A, AM, and PM areas, suggesting functional specialization between V1 and the HVAs.10 In addition, the PPC areas (RL/A and AM) branched from both V1 and PM, indicating that the PPC has a distinct role in optic flow processing (Figure 5A). In contrast, there was little hierarchical segregation, and even more correlated optic flow representations, between visual areas in Frmd7tm mice (mean correlation coefficient, 0.93 ± 0.01; Figures 5A–5C). Notably, optic flow responses in area RL/A were remarkably similar to those in V1 in Frmd7tm mice (correlation coefficient 0.58 and 0.98 for wild-type and Frmd7tm mice, respectively; p < 0.001, Fischer’s transformation; Figure 5C), abolishing any functional segregation between these areas. In contrast, the PM area of both wild-type and Frmd7tm mice appeared on the same branch (Figure 5A), supporting the notion that motion processing in this area is independent of retinal direction selectivity.

To further investigate area specialization, we assessed the proportion of monocular- versus binocular-driven functional groups within each visual area and quantified the relationship with a selectivity index (Figure 5C; see STAR methods). In wild-type mice, the bias toward monocular or binocular motion differed between visual areas to the extent that RL/A emerged as a specialized area for binocular optic flow processing (binocular optic flow index, −0.39 for V1, 0.21 for RL/A, 0.059 for AM, and −0.11 for PM). In contrast, this functional diversity was absent in Frmd7tm mice, and monocular-driven neurons were overrepresented across the visual areas (binocular optic flow index, −0.38 for V1, −0.44 for RL/A, −0.18 for AM, and −0.19 for PM).

From these data, we conclude that retinal direction selectivity contributes to functional segregation and response specialization between the different areas of the visual cortex. The most striking effect of retinal direction selectivity disruption in Frmd7tm mice is the transformation of optic flow responses in the RL/A area into responses reminiscent of responses in V1, indicating a specific role for the RL/A area in binocular integration of motion information originating from retinal DS cells.

Discussion

Our study provides four major insights into how the processing of optic flow within the monocular visual field is functionally organized in the visual system of mice. First, translation- and rotation-selective neurons are abundant in areas RL/A, AM, and PM, whereas neurons suppressed by binocular motion are common in V1. Second, translation-selective neurons in V1 and translation- and rotation-selective neurons in the RL/A, but not AM and PM areas, rely on direction selectivity that is computed in the retina. Third, binocular-suppressed neurons, which would be efficiently activated by monocularly restricted motion but suppressed by self-motion-induced optic flow, do not rely on retinal direction selectivity. Fourth, retinal direction selectivity contributes to the functional segregation of optic flow responses between V1 and RL/A. Our results, therefore, demonstrate a causal link between retinal motion computations and optic flow representations in specific areas of the visual cortex. Furthermore, they establish a critical role for retinal direction selectivity in the cortical processing of whole-field optic flow, thereby answering a previously proposed hypothesis.27

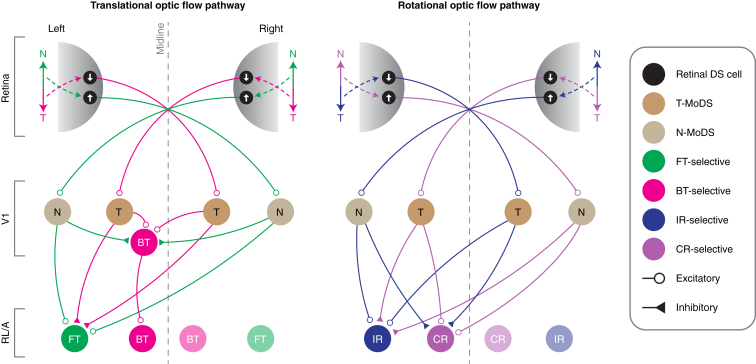

The altered optic flow representations in Frmd7tm mice imply potential functional circuits to link retinal horizontal DS cells and cortical layer 2/3 neurons with distinct optic flow response preferences (Figure 6). Our results suggest that information from retinal DS cells, tuned to motion in either the nasal or temporal direction, is propagated to layer 2/3 of the contralateral V1, where it contributes to establishing monocular DS responses tuned to horizontal motion. In turn, a fraction of backward translation-selective responses in V1 are likely synthesized from these monocular DS inputs, converging from V1 in both hemispheres via interhemispherically projecting neurons.34 In addition, a fraction of rotation-selective responses in area RL/A are likely synthesized from monocular nasal- and temporal-motion-preferring DS inputs converging from V1 in the same and opposite hemisphere, respectively. These hypotheses could be tested by functionally characterizing the presynaptic network of individual translation- or rotation-selective neurons using rabies-virus-based trans-synaptic tracing.35,36 Our data also suggest that translation- and rotation-selective neurons in V1 and RL/A are suppressed by visual motion in non-preferred directions on either retina (Figure 6). Such response suppression could be mediated by inhibitory monocular DS neurons or inhibitory interneurons activated by excitatory monocular DS neurons. In the present study, we sampled both excitatory and inhibitory neurons, but future studies could clarify this issue by genetically assigning imaged neurons into excitatory and inhibitory cell types.

Figure 6.

Proposed circuit model for translational and rotational optic flow processing

Left: FT optic flow activates nasal motion-preferring DS cells in the left and right retinas, mediating activity in nasal (N) motion-preferring MoDS (N-MoDS) neurons in V1 of both hemispheres, and subsequently their combination in FT-selective neurons in area RL/A. Activity in N-MoDS neurons also inhibits BT-selective neurons. BT optic flow activates temporal (T) motion-preferring DS cells in the left and right retinas, mediating activity in temporal motion-preferring MoDS (T-MoDS) neurons in V1 of both hemispheres, and subsequently their combination in BT-selective neurons in V1 and RL/A. Activity in T-MoDS neurons also inhibits FT-selective neurons. Right: IR optic flow activates temporal and nasal motion-preferring DS cells in the left and right retinas, respectively, mediating activity in N- and T-MoDS neurons in V1 of the left and right hemispheres, respectively. The signals from these V1 neurons, in turn, combine at IR-selective neurons in RL/A of the left hemisphere, and their activity inhibits CR-selective neurons in the left hemisphere. CR optic flow activates nasal and temporal motion-preferring DS cells in the left and right retinas, respectively, mediating activity in T- and N-MoDS neurons in V1 of the left and right hemispheres, respectively. The signals from these V1 neurons, in turn, combine at CR-selective neurons in RL/A of the left hemisphere, and their activity inhibits IR-selective neurons of the left hemisphere. The wiring diagram is expected to be mirror symmetric in relation to the midline.

Our results also offer insights into the cortical pathways that process visual motion independently of direction selectivity computed in the retina. Our analyses reveal that neuronal responses suppressed by binocular motion are common in V1 and HVAs and that these do not rely on retinal direction selectivity. This suggests that the V1 circuitry associated with binocular-suppressed neurons is functionally segregated from the circuitry processing retinal direction selectivity.12,13,25,26 Interestingly, the majority of binocular-suppressed neurons in V1 had a preference for motion in the ipsilateral eye (Figure 1H), suggesting that these neurons may combine the following two distinct types of input: (1) DS or non-DS excitatory inputs originating from non-DS cells in the ipsilateral eye via interhemispherically projecting neurons in the contralateral V1 and (2) non-DS inhibitory inputs driven by the activity of the contralateral eye. Our analyses also detected retinal DS cell-independent binocular optic flow responses in layer 2/3 of the visual cortex (Figures 3 and S6). Prior work in monkeys showed that binocular-suppressed and binocular-facilitated responses of monocular V1 neurons can be observed in the main visual input layer (layer 4).31 In mice, one form of de novo direction selectivity emerges in layer 4.37 Hence, it is plausible that retinal direction-selectivity-independent forms of binocular-suppressed and binocular-facilitated DS responses may arise in layer 4 from binocular interactions of DS signals originating from cortically computed direction selectivity. This idea is consonant with previous work in mice demonstrating that layer 4 neurons in V1 generate directionally tuned responses independent of inputs from retinal DS cells.13

Accumulating evidence suggests that areas RL and A are part of the PPC in mice15, 16, 17, 18—a key nexus of sensorimotor integration that is involved in decision making during spatial navigation,38 the encoding of body posture,39 global motion analysis,40,41 and representations of spatial information.42 Intriguingly, more than 50% of neurons in the RL area are multi-sensory in mice, integrating both tactile and visual sensory inputs.43 To advance our understanding of the behavioral function of area RL/A, it will thus be important to determine whether translation- and rotation-selective neurons display multi-sensory representations of self-motion (for example, whether they encode the direction of whisker deflections). Moreover, identifying the specific projection targets of these neurons might provide insight into how sensory self-motion information feeds into, for example, neuronal circuits for movement control. We speculate that area RL/A, as defined in our experiments, may be the functional correlate of the ventral intraparietal area of the PPC in monkeys, where multi-sensory representation of self-motion is utilized for goal-directed movements.44 Thus, an intriguing question that emerges from our results is whether responses to binocular optic flow in the PPC of monkeys rely on retinal direction selectivity, as they do in the RL/A area in mice. A first step toward addressing this would be to determine whether retinal DS cells exist in non-human primates, making it possible to define common principles of visual motion processing as well as the modifications that have occurred throughout the course of evolution.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| AAV2/1-Syn-GCaMP6f-WPRE | UPenn Vector Core | AV-1-PV2822 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Isoflurane (IsoFlo vet) | Zoetis | Cat# 199112 |

| Fentanyl | Hameln | Cat# 621062 |

| Midazolam (Dormicum) | Hameln | Cat# 516081 |

| Medetomidine (Dormitor) | Orion | Cat# 068824 |

| Flumazenil (Anexate) | Hameln | Cat# 55081 |

| Atipamezole (Antisedan) | Orion Pharma | Cat# 1639405 |

| Chlorprothexine | Sigma | Cat# C1671-1G |

| Jet Denture Repair Powder | Lang Dental | Item# 1230CLR |

| Super Glue Precision | Loctite | Cat# 2062278 |

| Ultrasound gel (NeurGel) | Spes Medica | Cat# NEURGEL250V |

| Silicone oil (10,000 molecular weight) | Lrp Hitemp | Cat# 68130 |

| Deposited data | ||

| Original datasets on GitHub | This paper | https://github.com/Neurune/OpticFlowCortex |

| Experimental models: organisms/strains | ||

| Mouse: C57BL/6J | Janvier Labs | C57BL/6JRj |

| Mouse: FRMD7tm1a(KOMP)Wtsi | KOMP Repository | Project ID: CSD48756 |

| Mouse: FRMD7tm1b(KOMP)Wtsi | KOMP Repository | Project ID: CSD48756 |

| Mouse: Edil3Tg(Sox2-cre)1Amc/J | Jackson Laboratory | Stock # 004783 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| MATLAB | The MathWorks | https://ch.mathworks.com/products/matlab |

| LabView | National Instruments | https://www.ni.com/labview/d/ |

| Psychophysics Toolbox | 45 | http://psychtoolbox.org/ |

| SciScan v1.3 | Scientifica | https://sciscan.scientifica.uk.com/ |

| EyeLoop | 46 | https://github.com/simonarvin/eyeloop |

| Spherical stimulus correction for mice | Spencer Smith, Labrigger | https://labrigger.com/blog/2012/03/06/mouse-visual-stim/ |

| Suite2p | 47 | https://github.com/cortex-lab/Suite2P |

| Quine and McCluskey algorithm | MathWorks File Exchange | https://se.mathworks.com/matlabcentral/fileexchange/37118-mintruthtable-tt-flags |

| Other | ||

| Borosilicate glass micropipettes | Sutter Instruments | Item# BF100-50-10 |

| Picospritzer III | Parker | Cat# 051-0530-900 |

| Feedback-controlled heating pad | World Precision Instruments | Item# ATC2000 |

| Titanium imaging chamber | This paper | Custom |

| Gelfoam sponges | Pfizer | Item# G50825 |

| Glass coverslips (0.15 mm thickness) | Warner Instruments | Cat# 64-0700 |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact Keisuke Yonehara (keisuke.yonehara@dandrite.au.dk).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and code availability

Original data and code have been deposited to GitHub (https://github.com/Neurune/OpticFlowCortex).

Experimental model and subject details

Mice

All experimental procedures were approved by the Danish National Animal Experiment Committee (2020-15-0201-00452) and were performed in compliance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Wild-type mice (C57BL/6J) were obtained from Janvier Labs. Frmd7tm mice were homozygous female or hemizygous male Frmd7tm1b(KOMP)Wtsi mice, obtained as Frmd7tm1a(KOMP)Wtsi from the Knockout Mouse Project (KOMP) Repository24,25: Exon 4 and the neo cassette flanked by loxP sequences were removed by crossing with female Cre-deleter Edil3Tg(Sox2-cre)1Amc/J mice (The Jackson Laboratory: stock 4783), as confirmed by PCR of genome DNA, and maintained in a C57BL/6J background. Experiments were performed on 9 male and female wild-type mice, and 8 female and male Frmd7tm mice. All mice were 12–18 weeks old during imaging experiments. Mice were kept on a reversed 12 h dark/light cycle and housed in groups of up to four littermates per cage.

Chronic cranial windows

Mice were anaesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of a Fentanyl (0.05 mg/kg body weight; Hameln), Midazolam (5.0 mg/kg body weight; Hameln), and Medetomidine (0.5 mg/kg body weight; Domitor, Orion) mixture. To prevent neural edema during or after surgery, dexamethasone (0.2 mg/kg body weight; Dexium, Bimeda) was injected subcutaneously. Body temperature was maintained using a feedback-controlled heating pad (ATC2000, World Precision Instruments) and eyes were protected from dehydration with eye ointment (Viscotears, Novartis). The scalp overlying the skull was removed, and a custom head-fixing imaging head-plate, with a circular 8 mm diameter opening, was mounted using a mixture of cyanoacrylate-based glue (Super Glue Precision, Loctite) and dental cement (Jet Denture Repair Powder). The center of the head-plate was positioned above V1 (stereotaxic coordinates: 2.5 mm lateral, 1 mm anterior of lambda). A 5 mm craniotomy was made in the center of the head-plate. After removing the skull flap, the cortical surface was kept moist with Ringer’s solution (in mM): 110 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1 CaCl2, 1.6 MgCl2, 10 glucose, and 22 NaHCO3. A 5 mm glass coverslip (0.15 mm thickness, Warner Instruments) was placed onto the brain to shield and gently compress the underlying cortex. The cranial window was sealed using a cyanoacrylate-based glue (Super Glue Precision, Loctite) mixed with black dental cement (Jet Denture Repair Powder mixed with iron oxide powdered pigment), to prevent light contamination from the visual display. In addition, a black O-ring was mounted on top of the head-plate to further prevent any light contamination during imaging. Mice were administered subcutaneous analgesia (0.1 mg/kg body weight; Temgesic, Indivior) and returned to their home cage after anesthesia was reversed with an intraperitoneal injection of a Flumazenil (0.5 mg/kg body weight; Hameln) and Atipamezole (2.5 mg/kg body weight; Antisedan, Orion Pharma) mixture.

Virus injections

Mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of a Fentanyl (0.05 mg/kg body weight; Hameln), Midazolam (5.0 mg/kg body weight; Hameln), and Medetomidine (0.5 mg/kg body weight; Domitor, Orion) mixture. To prevent neural edema during or after the surgery, dexamethasone (0.2 mg/kg body weight; Dexium, Bimeda) was injected subcutaneously. Three small 0.4 mm diameter craniotomies were made and ∼100−150 nL AAV2/1-Syn-GCaMP6f-WPRE (2.13 × 1013 vg/ml, Penn Vector Core #AV-1-PV2822) slowly injected (5 min/injection) at a depth of ∼275 μm below the dura. By using the pan-neuronal promoter, synapsin, this viral vector drives GCaMP6f expression in both excitatory and inhibitory neurons. Injections were made using a borosilicate glass micropipette (30 μm tip diameter) and a pressure injection system (Picospritzer III, Parker). The micropipette was advanced at a 20° angle relative to vertical to minimize compression of the brain. To prevent backflow during withdrawal, the micropipette was kept at the injection site for 10 min before it was slowly retracted. The skin was sutured shut and postoperative analgesia was administered subcutaneously (0.1 mg/kg body weight; Temgesic, Indivior). Mice were returned to their home cage after anesthesia was reversed with an intraperitoneal injection of a Flumazenil (0.5 mg/kg body weight; Hameln) and Atipamezole (2.5 mg/kg body weight; Antisedan, Orion Pharma) mixture.

Intrinsic signal retinotopic mapping

Before two-photon calcium imaging, cortical visual areas of each mouse were identified by intrinsic signal optical imaging as previously described13. Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (2−3% induction) and head-fixed in a custom holder. Chlorprothexine was administered intraperitoneally (2.5 mg/kg body weight; Sigma) as a sedative33, and isoflurane reduced to 0.5−1% during visual stimulation. Core body temperature was maintained at 37−38°C using a feedback-controlled heating pad (ATC2000, World Precision Instruments). The stimulated contralateral eye was kept lubricated by a thin layer of silicone oil. A 2 × air-objective (Olympus, 0.08 NA) was mounted on our Scientifica VivoScope, equipped with a CMOS camera (HD1-D-D1312-160-CL-12, PhotonFocus). The camera was connected to a Matrox Solios (eCL/XCL-B) frame-grabber via Camera Link. The microscope was defocused 400−600 μm down from the pial surface, where intrinsic signals were excited using a red LED (KL1600, Schott) delivered through a 610 nm long-pass filter (Chroma). Reflected light was captured through a 700 ± 50 nm band-pass filter (Chroma) positioned in front of the camera, and images were collected at 6 frames per second. The 47.65 × 26.87 cm (width × height) display was angled 30° from the midline of the mouse and the perpendicular bisector was 10 cm from the bottom of the display, centered on the display left to right, and 10 cm from the eye13,28. This resulted in a visual field coverage from –41.98° to 60.77° (total 102.75°) in elevation, and from –67.23° to 67.23° (total 134.46°) in azimuth. Retinotopic maps were generated by sweeping a spherically corrected full-field bar across the display (see Key Resources Table). The bar contained a flickering black-and-white checkerboard pattern on a black background. The width of the bar was 12.5° and the checkerboard square size was 25°. Each square alternated between black and white at 4 Hz. In each trial, the bar was drifted ten times in each of the four cardinal directions, moving at 8−9°/s. Usually, two to four trials resulted in well-defined retinotopic maps. From the raw image data, we used the response time course for each pixel and computed the phase and magnitude of the Fourier transform at the visual stimulus frequency48. The phase maps were then converted into retinotopic coordinates from the geometry of our setup. From this, we identified visual area borders based on the visual field sign maps and superimposed those borders with the anatomical blood-vessel images to accurately localize visual cortical areas.

Two-photon calcium imaging

Imaging was initiated two weeks after virus injections. Mice were awake during all imaging sessions as previously described13. To habituate mice to handling and the experimental conditions, one week after cranial window implantation, each mouse was head-fixed onto the imaging stage with its body restrained in a cylindrical cover, reducing struggling and overt body movements13. The habituation procedure was repeated for at least three days for each mouse at durations of 15, 30, and 60 min on days one, two, and three, respectively. At the end of each session, mice were rewarded with chocolate paste. Imaging session lasted 1−2 h. The area targeted for two-photon imaging was localized by previous intrinsic signal optical imaging. Imaging was performed from layer 2/3, 120–275 μm below the dura, using a Scientifica VivoScope with a 7.9 kHz resonant scanner running SciScan, and with dispersion-compensated 940 nm excitation provided by a mode-locked Ti:Sapphire laser (MaiTai DeepSee, Spectra-Physics) through an Olympus 25 × (1.05 NA) objective. The emitted fluorescence photons were reflected off a dichroic mirror (525/50 nm) and collected using a GaAsP photomultiplier tube (Scientifica). Clear ultrasound gel (NeurGel, Spes Medica) was used as immersion medium. To prevent light leakage from the visual stimulation, the objective was shielded with black tape, in addition to the O-ring mounted on top of the head-plate, and black cloth covered the microscope. Average excitation laser power varied from 40 to 65 mW. Images had 512 × 512 pixels, at 0.2 μm per pixel, and were acquired at 30.9 Hz using bidirectional scanning. We observed no sign of GCaMP6f bleaching during experiments. Each mouse was imaged repeatedly over the course of 2–3 weeks.

Visual stimulus for two-photon calcium imaging

For visual stimulation during two-photon calcium imaging experiments, two 47.65 × 26.87 cm (width × height) displays were angled 30° from the midline of the mouse on the left and right side; each display subtending 115.61° in azimuth and 80.95° in elevation (Figure 1B). The visual stimulus protocol employed was adapted from a previous study3. Full-field vertical sinusoidal gratings (100% contrast; spatial frequency of 0.03 cycles/°) with a spherical correction to simulate projection onto a virtual sphere moved horizontally at speeds of 10 or 40°/s. The horizontal transition consisted of eight separate conditions (6 s each, interspersed with 4 s of gray screen between conditions): 1) Left nasal, 2) Left temporal, 3) Right nasal, 4) Right temporal, 5) contraversive, 6) ipsiversive, 7) forward, 8) backward (Video S1). Conditions 1–4 and were thus monocular, and conditions 5–8 binocular, simulating the rotational and translational optic flow experienced during turning and straight movements, respectively. The sequence of eight conditions was repeated in six trials. The mouse’s binocular visual field (central 40°) did not contain the visual stimulus, to ensure only stimulation of the monocular visual field49.

Eye movement tracking

In a subset of experiments, we tracked eye movements in awake mice during presentation of our visual stimulus protocol (Figure S2). We employed an eye-tracking system developed in our laboratory and recently described in detail46. Briefly, a small 45° hot mirror was aligned above a CCD camera (Guppy Pro F-031, AlliedVision) lateral to the position of the mouse. The camera was positioned below the visual field. Behind the visual stimulus display, a near-infrared light source (SLS-02082-B, Mightex Systems) was angled at 45° to illuminate the recorded eye. The camera was connected to a PC via a dedicated frame grabber (FIW62, ADLINK) and images were collected at ∼65 frames per second. Using the eye-tracking software, EyeLoop, images were processed, and pupil and corneal reflection coordinates were computed46. From these, the angular eye coordinates ( and ) were calculated. Horizontal eye speed was obtained by taking the first derivative of the horizontal eye coordinates ( and ), and low pass filtering and with a 1 s moving average filter26. Saccades were identified as events with a speed > 20°/s. Stimulus-triggered horizontal eye speed and saccade rate traces were obtained by averaging over all trials.

Data analysis

Preprocessing of two-photon calcium imaging data

Imaging data were excluded from analysis if motion along the z axis was detected. Raw two-photon imaging movies were corrected for in-plane motion using a piecewise non-rigid motion correction algorithm implemented in MATLAB (Mathworks)50. To detect regions of interest (ROIs) we used the MATLAB implementation of Suite2p47. ROIs were automatically detected using the motion-corrected frames and afterward manually curated using the Suite2p graphical user interface. From the motion-corrected movies and detected ROIs, we extracted the fluorescence time courses within each ROI. To correct the calcium traces for contamination from the surrounding neuropil, we also extracted the fluorescence of the surrounding neuropil for each ROI. The time series of the neuropil decontaminated calcium trace, , was described by:

where is the somata calcium trace, is the neuropil trace, and is the contamination factor. The contamination factor was determined for each ROI as previously47. Briefly, and traces were first low pass filtered using the 8th percentile in a 180 s moving window, yielding and , respectively. These were then used to establish and . and were then used to determine as previously described47,51. Using the neuropil decontaminated calcium trace, baseline calcium fluorescence, was computed for each stimulus condition as the mean during the pre-stimulus period10. Fluorescence values were then converted to relative change compared to baseline according to: , where is the instantaneous neuropil decontaminated calcium trace and is the baseline calcium fluorescence. The mean neuronal responses were computed as the average response during the visual stimulus, and the mean and standard deviation across trials for each stimulus condition was computed for each neuron. To identify neurons for further in-depth analysis we used three inclusion criteria: 1) Neurons were defined as visually responsive if their mean to the preferred stimulus condition exceeded 10%; 2) A response reliability index, , was computed for each neuron as:

where and are the mean and standard deviations of the response to the preferred stimulus condition respectively, and and are the mean and standard deviations of the response to a blank stimulus respectively10. Neurons with exceeding 0.6 were defined as reliable; and 3) A signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) was computed for each neuron as:

where is the mean of the response to the preferred stimulus condition and is the mean of the standard deviation of the fluorescence trace during the baseline period (0.5 s before stimulus onset) for each trial52. Neurons with SNR exceeding 0.5 were defined as robustly responding. Only neurons that fulfilled all inclusion criteria at both stimulus speeds were included for further analysis procedures.

Response profile classification

In order to classify the response of individual neurons into separate functional groups, representing distinct response profiles, we employed regression analysis similar to previously described3. First, we summarized the response of each neuron by a tuning curve, including the mean for each of the eight stimulus conditions. We compiled this tuning curve for both stimulus speeds, and we determined the speed in which the highest mean was evoked; noted as the preferred speed of the neuron. By considering the response selectivity of a neuron to the eight stimulus conditions, we assumed that the response profile regressors could be described by an indicator function, , as follows:

where is the stimulus condition, and 28 (i.e., 256) possible regressors exist for (Figure 1G). These 256 regressors correspond to the possible response combinations from the monocular and binocular stimulations in the nasal and temporal directions. For each neuron we then computed the linear Pearson’s correlation for its tuning curve at the preferred speed against each of the 256 regressors and determined the regressor with the highest correlation (Figures S3A–S3C). All neuronal tuning curves had high correlation with its assigned response regressor (mean correlation coefficient, 0.91 ± 0.05, n = 26712 neurons from 17 mice). The response regressors were functionally described using a MATLAB implementation of the Quine and McCluskey algorithm (see Key Resources Table), in which the Boolean functions were minimized to find the logical function for each response profile that use only a small number of logical operations3. Here, we focused on the simple (MoDS, BiDS, and non-DS), binocular-suppressed (DS, and non-DS:), and translation-selective or rotation-selective (FT, BT, CR, and IR) response classes (Figure 2). The simple and translation- or rotation-selective response classes are responsive to both monocular and binocular motion stimulation, and these were identified and described in detail previously3. In this work, we identified the binocular-suppressed response class, characterized by only responding to monocular motion stimulation, in a DS or non-DS manner (Figure 2). The binocular-suppressed functional groups (regressor IDs) were described by the following Boolean logical operations:

where is the identity of the regressors, and and are nasal and temporal motion directions, respectively, and and are stimulation of the left and right eyes, respectively, and is a logical ”NOT” gate operator.

Response similarity analysis

To evaluate the similarity in response time courses of neurons assigned to their respective regressors, we computed the correlation of Ca2+ transients across the stimulus conditions. First, we computed the correlation strength between pairs of neurons assigned to the same regressor for each of the stimulus conditions that evoked responses in the particular regressor profile (for example, regressor #56: right temporal, contraversive rotational, and backward translational) as the peak amplitude in the cross-correlation :

where and indicate Ca2+ transients during stimulus condition and in neuron and , respectively, which are both assigned to regressor . From these correlation strength values we obtained distribution histograms of correlation strength for each regressor (Figure S3D).

Response profile shuffling analysis

To assess the empirical frequency distributions of neurons assigned to individual regressor profiles and response classes (Figures 3A and 3B), we carried out statistical investigations. First, we obtained shuffled response tuning curves for each neuron by randomly shuffling the mean values recorded during the eight stimulus conditions, added with noise from a normal distribution:

where is the de novo generated tuning curve of neuron from the shuffled pattern of , is the original tuning curve of neuron with the original pattern of , and is a noise value obtained from a normal distribution, , with a mean, , and standard deviation, , calculated from the original tuning curve of neuron . Next, we determined the frequency of each regressor profile using the shuffled response tuning curves. Using this, we estimated the false positive probability for each regressor by comparing the frequency of assigned neurons in the shuffled dataset to that in the original dataset using bootstrap sampling (500 samples). A false positive was defined by the frequency of assigned neurons being higher in the shuffled dataset compared to in the original dataset. If was lower than 0.05, the frequency of neurons assigned to a given response regressor was considered significantly higher than noise (or chance) levels.

Comparison of response classes and functional groups among visual cortical areas

To examine similarities and disparities in response class distributions across visual areas in wild-type and Frmd7tm mice, we performed a hierarchical clustering analysis. For this, we used the mean proportion of neurons assigned to each of the 33 response types (i.e., regressors) within the simple, translation- and rotation-selective, and binocular-suppressed response classes to create a monocular and binocular motion flow “fingerprint” for each visual area in wild-type and Frmd7tm mice. To create a hierarchical cluster tree, we used the linkage function in MATLAB, and visualized the result in a dendrogram (Figure 5A). For quantifying similarities and disparities across visual areas within wild-type and Frmd7tm mice (Figures 5B and 4C), we computed Pearson’s correlation coefficients using the motion flow fingerprint of each visual area. To quantify the proportions of monocular versus binocular functional groups within each visual cortical area, we computed a binocular optic flow index (BOFI). For this, we determined the proportion of monocular driven (simple MoDS and non-DS, and binocular-suppressed DS and non-DS) and binocular driven (simple BiDS, and FT, BT, CR, and IR) functional groups, and computed the BOFI as:

with a BOFI of 1 indicating that only binocular driven functional groups are represented, while a BOFI of –1 indicates only monocular driven groups are represented.

Quantification and statistical analysis

To statistically evaluate differences between functional groups or individual response types in wild-type and Frmd7tm mice, we used the two-sided Mann-Whitney U test. To compare the Pearson’s correlation coefficients obtained from two independent samples, i.e., wild-type and Frmd7tm mice, we used the Fischer’s r-to-z transformation and obtained the corresponding two-sided p value. To compare eye movement speeds, or saccade rates, before and during visual stimulation or between wild-type and Frmd7tm mice, we used two-sided Student’s t tests (paired or unpaired where appropriate). To compare stimulus-related changes in eye movement speeds, or saccade rates, across stimulus conditions, we used a repeated-measure analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by multiple comparison testing using the Tukey honestly significantly different post hoc test. Center and spread values are reported as mean ± SEM. We used no statistical methods to plan sample sizes but used sample sizes similar to those frequently used in the field10,13,17. Exact n (i.e., number of animals and neurons) is included in the Result section and Table S1. Data collection and analysis were not performed blind to the conditions of the experiments. No collected data were excluded from analysis. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05, where ∗ p < 0.05 and ∗∗ p < 0.01. All statistical analyses were carried out in MATLAB.

Acknowledgments

We thank Zoltan Raics for developing our visual stimulation system and Bjarke Thomsen and Misugi Yonehara for technical assistance. We also thank Eric Nicholas, Ubadah Sabbagh, Thomas Wheatcroft, and Lesley Anson for commenting on the manuscript. We acknowledge the following grants for financial support: Lundbeck Foundation PhD Scholarship (R230-2016-2326) to R.N.R.; Velux Foundation Postdoctoral Ophthalmology Research Fellowship (27786) to A.M.; and Lundbeck Foundation (DANDRITE-R248-2016-2518 and R252-2017-1060), Novo Nordisk Foundation (NNF15OC0017252), Carlsberg Foundation (CF17-0085), and European Research Council Starting (638730) grants to K.Y.

Author contributions

R.N.R. and K.Y. conceived the project and designed all experiments. R.N.R. performed all viral injections and surgeries. R.N.R. performed all intrinsic signal optical imaging and two-photon calcium imaging experiments. R.N.R. and S.A. performed eye movement recording experiments. R.N.R., S.A., and A.M. analyzed the data. K.Y. provided input on all aspects of the project. R.N.R., A.M., and K.Y. wrote the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: January 22, 2021

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2020.12.034.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Krapp H.G., Hengstenberg R., Egelhaaf M. Binocular contributions to optic flow processing in the fly visual system. J. Neurophysiol. 2001;85:724–734. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.2.724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farrow K., Haag J., Borst A. Nonlinear, binocular interactions underlying flow field selectivity of a motion-sensitive neuron. Nat. Neurosci. 2006;9:1312–1320. doi: 10.1038/nn1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kubo F., Hablitzel B., Dal Maschio M., Driever W., Baier H., Arrenberg A.B. Functional architecture of an optic flow-responsive area that drives horizontal eye movements in zebrafish. Neuron. 2014;81:1344–1359. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naumann E.A., Fitzgerald J.E., Dunn T.W., Rihel J., Sompolinsky H., Engert F. From whole-brain data to functional circuit models: the zebrafish optomotor response. Cell. 2016;167:947–960.e20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wylie D.R.W., Bischof W.F., Frost B.J. Common reference frame for neural coding of translational and rotational optic flow. Nature. 1998;392:278–282. doi: 10.1038/32648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simpson J.I., Leonard C.S., Soodak R.E. The accessory optic system of rabbit. II. Spatial organization of direction selectivity. J. Neurophysiol. 1988;60:2055–2072. doi: 10.1152/jn.1988.60.6.2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sunkara A., DeAngelis G.C., Angelaki D.E. Joint representation of translational and rotational components of optic flow in parietal cortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:5077–5082. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1604818113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duffy C.J., Wurtz R.H. Sensitivity of MST neurons to optic flow stimuli. I. A continuum of response selectivity to large-field stimuli. J. Neurophysiol. 1991;65:1329–1345. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.65.6.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanaka K., Saito H. Analysis of motion of the visual field by direction, expansion/contraction, and rotation cells clustered in the dorsal part of the medial superior temporal area of the macaque monkey. J. Neurophysiol. 1989;62:626–641. doi: 10.1152/jn.1989.62.3.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marshel J.H., Garrett M.E., Nauhaus I., Callaway E.M. Functional specialization of seven mouse visual cortical areas. Neuron. 2011;72:1040–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhuang J., Ng L., Williams D., Valley M., Li Y., Garrett M., Waters J. An extended retinotopic map of mouse cortex. eLife. 2017;6:18372. doi: 10.7554/eLife.18372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cruz-Martín A., El-Danaf R.N., Osakada F., Sriram B., Dhande O.S., Nguyen P.L., Callaway E.M., Ghosh A., Huberman A.D. A dedicated circuit links direction-selective retinal ganglion cells to the primary visual cortex. Nature. 2014;507:358–361. doi: 10.1038/nature12989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rasmussen R., Matsumoto A., Dahlstrup Sietam M., Yonehara K. A segregated cortical stream for retinal direction selectivity. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:831. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-14643-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glickfeld L.L., Andermann M.L., Bonin V., Reid R.C. Cortico-cortical projections in mouse visual cortex are functionally target specific. Nat. Neurosci. 2013;16:219–226. doi: 10.1038/nn.3300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lyamzin D., Benucci A. The mouse posterior parietal cortex: anatomy and functions. Neurosci. Res. 2019;140:14–22. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2018.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hovde K., Gianatti M., Witter M.P., Whitlock J.R. Architecture and organization of mouse posterior parietal cortex relative to extrastriate areas. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2019;49:1313–1329. doi: 10.1111/ejn.14280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Minderer M., Brown K.D., Harvey C.D. The spatial structure of neural encoding in mouse posterior cortex during navigation. Neuron. 2019;102:232–248.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilissen S.R.J., Farrow K., Bonin V., Arckens L. Reconsidering the border between the visual and posterior parietal cortex of mice. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhaa318. 2020.03.24.005462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dhande O.S., Huberman A.D. Retinal ganglion cell maps in the brain: implications for visual processing. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2014;24:133–142. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2013.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Borst A., Euler T. Seeing things in motion: models, circuits, and mechanisms. Neuron. 2011;71:974–994. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rasmussen R., Yonehara K. Contributions of retinal direction selectivity to central visual processing. Curr. Biol. 2020;30:R897–R903. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wei W., Feller M.B. Organization and development of direction-selective circuits in the retina. Trends Neurosci. 2011;34:638–645. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yonehara K., Ishikane H., Sakuta H., Shintani T., Nakamura-Yonehara K., Kamiji N.L., Usui S., Noda M. Identification of retinal ganglion cells and their projections involved in central transmission of information about upward and downward image motion. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e4320. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yonehara K., Fiscella M., Drinnenberg A., Esposti F., Trenholm S., Krol J., Franke F., Scherf B.G., Kusnyerik A., Müller J. Congenital nystagmus gene FRMD7 is necessary for establishing a neuronal circuit asymmetry for direction selectivity. Neuron. 2016;89:177–193. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.11.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hillier D., Fiscella M., Drinnenberg A., Trenholm S., Rompani S.B., Raics Z., Katona G., Juettner J., Hierlemann A., Rozsa B., Roska B. Causal evidence for retina-dependent and -independent visual motion computations in mouse cortex. Nat. Neurosci. 2017;20:960–968. doi: 10.1038/nn.4566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Macé É., Montaldo G., Trenholm S., Cowan C., Brignall A., Urban A., Roska B. Whole-brain functional ultrasound imaging reveals brain modules for visuomotor integration. Neuron. 2018;100:1241–1251.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sabbah S., Gemmer J.A., Bhatia-Lin A., Manoff G., Castro G., Siegel J.K., Jeffery N., Berson D.M. A retinal code for motion along the gravitational and body axes. Nature. 2017;546:492–497. doi: 10.1038/nature22818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Juavinett A.L., Nauhaus I., Garrett M.E., Zhuang J., Callaway E.M. Automated identification of mouse visual areas with intrinsic signal imaging. Nat. Protoc. 2017;12:32–43. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2016.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andermann M.L., Kerlin A.M., Roumis D.K., Glickfeld L.L., Reid R.C. Functional specialization of mouse higher visual cortical areas. Neuron. 2011;72:1025–1039. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kretschmer F., Tariq M., Chatila W., Wu B., Badea T.C. Comparison of optomotor and optokinetic reflexes in mice. J. Neurophysiol. 2017;118:300–316. doi: 10.1152/jn.00055.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dougherty K., Cox M.A., Westerberg J.A., Maier A. Binocular modulation of monocular V1 neurons. Curr. Biol. 2019;29:381–391.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang Q., Sporns O., Burkhalter A. Network analysis of corticocortical connections reveals ventral and dorsal processing streams in mouse visual cortex. J. Neurosci. 2012;32:4386–4399. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6063-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith I.T., Townsend L.B., Huh R., Zhu H., Smith S.L. Stream-dependent development of higher visual cortical areas. Nat. Neurosci. 2017;20:200–208. doi: 10.1038/nn.4469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramachandra V., Pawlak V., Wallace D.J., Kerr J.N.D. Impact of visual callosal pathway is dependent upon ipsilateral thalamus. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:1889. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15672-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wertz A., Trenholm S., Yonehara K., Hillier D., Raics Z., Leinweber M., Szalay G., Ghanem A., Keller G., Rózsa B. Presynaptic networks. Single-cell-initiated monosynapic tracing reveals layer-specific cortical network modules. Science. 2015;349:70–74. doi: 10.1126/science.aab1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yonehara K., Farrow K., Ghanem A., Hillier D., Balint K., Teixeira M., Jüttner J., Noda M., Neve R.L., Conzelmann K.-K., Roska B. The first stage of cardinal direction selectivity is localized to the dendrites of retinal ganglion cells. Neuron. 2013;79:1078–1085. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lien A.D., Scanziani M. Cortical direction selectivity emerges at convergence of thalamic synapses. Nature. 2018;558:80–86. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0148-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gold J.I., Shadlen M.N. The neural basis of decision making. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2007;30:535–574. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.113038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mimica B., Dunn B.A., Tombaz T., Bojja V.P.T.N.C.S., Whitlock J.R. Efficient cortical coding of 3D posture in freely behaving rats. Science. 2018;362:584–589. doi: 10.1126/science.aau2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Juavinett A.L., Callaway E.M. Pattern and component motion responses in mouse visual cortical areas. Curr. Biol. 2015;25:1759–1764. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rasmussen R., Yonehara K. Circuit mechanisms governing local vs. global motion processing in mouse visual cortex. Front. Neural Circuits. 2017;11:109. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2017.00109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Save E., Poucet B. Role of the parietal cortex in long-term representation of spatial information in the rat. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2009;91:172–178. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Olcese U., Iurilli G., Medini P. Cellular and synaptic architecture of multisensory integration in the mouse neocortex. Neuron. 2013;79:579–593. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bremmer F. Navigation in space--the role of the macaque ventral intraparietal area. J. Physiol. 2005;566:29–35. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.082552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brainard D.H. The Psychophysics Toolbox. Spat Vis. 1997;10:433–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arvin S., Rasmussen R., Yonehara K. EyeLoop: an open-source, high-speed eye-tracker designed for dynamic experiments. bioRxiv. 2020 2020.07.03.186387. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pachitariu M., Stringer C., Schröder S., Dipoppa M., Rossi L.F., Carandini M., Harris K.D. Suite2p: beyond 10,000 neurons with standard two-photon microscopy. bioRxiv. 2016:061507. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kalatsky V.A., Stryker M.P. New paradigm for optical imaging: temporally encoded maps of intrinsic signal. Neuron. 2003;38:529–545. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00286-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Scholl B., Pattadkal J.J., Priebe N.J. Binocular disparity selectivity weakened after monocular deprivation in mouse V1. J. Neurosci. 2017;37:6517–6526. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1193-16.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pnevmatikakis E.A., Giovannucci A. NoRMCorre: an online algorithm for piecewise rigid motion correction of calcium imaging data. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2017;291:83–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2017.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dipoppa M., Ranson A., Krumin M., Pachitariu M., Carandini M., Harris K.D. Vision and locomotion shape the interactions between neuron types in mouse visual cortex. Neuron. 2018;98:602–615.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.03.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Marques T., Nguyen J., Fioreze G., Petreanu L. The functional organization of cortical feedback inputs to primary visual cortex. Nat. Neurosci. 2018;21:757–764. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0135-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Animation showing the visual stimulus protocol we employed for testing the full horizontal motion repertoire. This consisted of eight conditions, in which spherically corrected sinusoidal moving gratings were first presented to one eye at a time in either the nasal or temporal direction, and then presented to both eyes, mimicking the rotational (ipsiversive and contraversive) and translational (forward and backward) optic flow that the mouse would experience during locomotion (i.e., forward-backward straight movements and left-right turning). The mouse’s binocular visual field (central 40°) did not contain the visual stimulus, to ensure only stimulation of the monocular visual field. This animation shows the gratings moving at 10°/s (spatial frequency, 0.03 cycles/°).

Data Availability Statement

Original data and code have been deposited to GitHub (https://github.com/Neurune/OpticFlowCortex).