Abstract

Breast carcinoma grading is an important prognostic feature recently incorporated into the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. There is increased interest in applying virtual microscopy (VM) using digital whole slide imaging (WSI) more broadly. Little is known regarding concordance in grading using VM and how such variability might affect AJCC prognostic staging (PS). We evaluated interobserver variability amongst a multi-institutional group of breast pathologists using digital WSI and how discrepancies in grading would affect PS.

A digitally scanned slide from 143 invasive carcinomas was independently reviewed by 6 pathologists and assigned grades based on established criteria for tubule formation (TF), nuclear pleomorphism (NP), and mitotic count (MC). Statistical analysis was performed.

Interobserver agreement for grade was moderate (κ=0.497). Agreement was fair (κ=0.375), moderate (κ=0.491), and good (κ=0.705) for grades 2, 3, and 1, respectively. Observer pair concordance ranged from fair to good (κ=0.354 to 0.684) Perfect agreement was observed in 43 cases (30%). Interobserver agreement for the individual components was best for TF (κ=0.503) and worst for MC (κ=0.281). 17 of 86 (19.8%) discrepant cases would have resulted in changes in PS and discrepancies most frequently resulted in a PS change from IA to IB (n=9). For two of these nine cases, Oncotype DX results would have led to a PS of 1A regardless of grade.

Using VM, a multi-institutional cohort of pathologists showed moderate concordance for breast cancer grading, similar to studies using light microscopy. Agreement was the best at the extremes of grade and for evaluation of TF. Whether the higher variability noted for MC is a consequence of VM grading warrants further investigation. Discordance in grading infrequently leads to clinically meaningful changes in the prognostic stage.

Keywords: cancer, variability, concordance, digital pathology, whole slide imaging

Introduction

Breast carcinoma grading schemes have evolved over the last century and histologic grading is one of the most important prognostic features in the evaluation of early-stage breast carcinoma.(1–6) The Nottingham system, which has been endorsed by the College of American Pathologists and the World Health Organization utilizes three variables: gland formation, nuclear grade, and mitotic rate.(1) In the latest edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, in addition to the anatomic stage groups (based on TNM alone), breast carcinomas can be organized into prognostic stage groups based on additional information including grade, biomarker status (i.e. estrogen receptor [ER], progesterone receptor [PR] and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 [HER2]), and molecular testing results.(7) According to a recent publication, which attempted to validate the new staging system, grade was statistically associated with overall survival and the prognostic stage group system was shown to outperform TNM alone.(8)

For prognostic markers, such as histologic grade, to be robust, there must be high reproducibility and low interobserver variability. Studies have shown that interobserver variability in breast carcinoma grading ranges from fair to good based on kappa statistics.(9–13) Since the incorporation of grading into the AJCC manual, little is known about how variability in grading might affect prognostic stage groups.(14)

Advances in technology have led to the advent of virtual microscopy (VM) using digital whole slide imaging (WSI), in which glass slides are digitally scanned at a high resolution for viewing on a screen. While the technology has mostly been in the educational, research, image analysis, and quality assurance settings, there is increased interest in broadly applying VM to the clinical domain.(15–20) Some platforms have been approved by the Federal Drug Association for diagnostic use.(21) Data are limited regarding the variability in breast carcinoma grading using VM, however recent studies have shown moderate concordance between grading using VM versus light microscopy (LM).(12, 13)

Considering the recent changes to the AJCC staging manual and organization of breast carcinomas into prognostic stage groups, understanding the interobserver variability of breast cancer grading is critical. Furthermore, as the push for using VM rather than LM in primary sign out increases, it is important to evaluate pathologists’ concordance in this setting. We sought to evaluate interobserver variability amongst a multi-institutional group of academic breast pathologists using digital WSI. As a secondary measure, we also evaluated whether discordances in grading would affect prognostic stage groups.

Materials and Methods

Patient Cohort

Cases of consecutive invasive breast carcinoma from the calendar year 2016 were identified in the pathology files at New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medicine. Cases of microinvasive carcinoma, those with insufficient tumor area to perform formal mitotic counts, and those treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy were excluded. The final cohort consisted of 143 consecutive invasive breast carcinomas. Archived hematoxylin and eosin slides were reviewed by one pathologist (PSG) who selected one representative slide for each lesion to be scanned into the digital slide platform. Pertinent clinicopathologic variables including age, gender, laterality, hormone receptor status, HER2 status, tumor focality, tumor size, and lymph node involvement were obtained from a review of the patient’s surgical pathology reports. Institutional review board approval was obtained for all parts of this study.

Digital Whole Slide Scanning

Slides were scanned at a 40X magnification using a single z-plane via an Aperio AT2 whole slide scanner (Leica Biosystems, San Diego, CA, USA). Scanned digital WSI were evaluated for quality and to ensure that they were in focus. De-identified digital files in (.svs) format were stored on an image server for remote evaluation using the Aperio ImageScope application (Leica Biosystems, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA).

Pathologic Examination and Grading

The digital WSIs were independently reviewed by 6 pathologists (PSG, RI, TMD, SF, SJ, and MH). All pathologists were instructed to grade tumors based on established criteria for tubule formation (TF), nuclear pleomorphism (NP), and mitotic count (MC) according to the Nottingham Grading System.(1, 7) Since the area viewed on the digital slides differs based on screen size, browser size, etc. the pathologists were provided instructions for annotating areas corresponding to a total area of 2.38 mm2 which corresponds to the area in 10 high power fields evaluated using an eyepiece with a field diameter of 0.55 mm to perform mitotic counts. Within this area, MCs of <8, 9 to 17, and ≥18 were scored as 1, 2, and 3, respectively. All pathologists included in this study have subspecialty interest and/or fellowship training in breast pathology and years of attending level sign out experience range from 4 to 25 years (median: 14 years). Pathologists were blinded to the original LM grade as well as other clinicopathologic parameters.

Evaluation of Potential Confounders

Following VM grading, participants were invited to complete a questionnaire (Supplementary Fig. 1). Seven questions were used to assess the experience (number of years in practice), work environment (academic and/or nonacademic laboratory), daily work method (conventional light microscopy and/or digital pathology), weekly amount of time dedicated to breast pathology, the habit of reporting nuclear grade in cases with heterogeneity, the method used to determine the mitotic rate, and whether any tumors were graded based on the assumption that it represented a special type of carcinoma.

Statistical Analysis

Fleiss’ k for overall agreement amongst all observers was calculated for overall grade and individual components, pairwise comparison between individual pathologists, and for histopathologic types of invasive carcinoma. Levels of agreement based on the kappa statistic were defined as follows: ≤0.20 as slight, 0.21–0.40 fair, 0.41–0.60 moderate, 0.61–0.80 good, and 0.8–1.00 very good.(22, 23) The most common grade (statistical mode) was taken as the gold standard, and interobserver concordance was evaluated based on this grade. When appropriate, t-tests were performed to examine correlations between the degree of interobserver variability and any possible confounder mentioned in the questionnaire. A P value of <0.05 (two-tailed) was considered significant. All analyses were performed using statistical software CRAN.R irr package (version 3.6.1).

Results

Patient and Clinicopathologic Characteristics

143 consecutive invasive breast carcinomas from 135 patients were identified. Two patients had bilateral invasive carcinoma. Three patients had multiple morphologically distinct ipsilateral invasive carcinomas. Another patient had bilateral invasive carcinoma and had multiple morphologically distinct ipsilateral invasive carcinomas. The cohort included 134 female patients and one male patient with a mean age of 63 years (range; 29–98). 125 tumors were hormone receptor (HR)-positive, HER2-negative/equivocal, 7 tumors were HR-positive, HER2-positive, 10 tumors were triple-negative, and 1 tumor was HR-negative, HER2-positive. Additional histopathologic features are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic Features of Cohort

| Parameters | Number of Cases (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| Range | 29 – 98 |

| Mean | 63 |

| Median | 64 |

| Laterality | |

| Right | 67 (46.8) |

| Left | 76 (53.2) |

| Tumor Size (cm) | |

| Range | 0.4 – 5.5 |

| Mean | 1.5 |

| Median | 1.2 |

| Histologic Type | |

| Ductal-no special type | 108 (75.5) |

| Lobular | 23 (16.1) |

| Tubular/Cribriform | 4 (2.8) |

| Pure mucinous | 2 (1.4) |

| Invasive solid papillary | 2 (1.4) |

| Invasive mucinous with micropapillary features | 1 (0.7) |

| Invasive micropapillary carcinoma | 1 (0.7) |

| Invasive tubulolobular carcinoma | 1 (0.7) |

| Invasive carcinoma with squamous metaplastic features | 1 (0.7) |

| Estrogen receptor | |

| Positive | 131 (91.6) |

| Negative | 12 (8.4) |

| Progesterone receptor | |

| Positive | 122 (85.3) |

| Negative | 21 (14.7) |

| HER2 | |

| Positive | 8 (5.6) |

| Negative | 132 (92.3) |

| Equivocal | 3 (2.1) |

| pT Category | N=138 |

| (m) | 4 (2.9) |

| 1a | 8 (5.8) |

| 1b | 46 (33.3) |

| 1c | 53 (38.4) |

| 2 | 28 (20.3) |

| 3 | 2 (1.5) |

| 4 | 1 (0.7) |

| pN Category | N=138 |

| 0 | 101 (73.2) |

| 1mi | 1 (0.7) |

| 1a | 15 (10.9) |

| 2a | 5 (3.6) |

| 3a | 2 (1.5) |

| Unknown | 14 (10.1) |

cm = centimeters

Agreement in Breast Carcinoma Grading

Perfect agreement was observed in 43 cases (30%) (Figure 1). Perfect agreement was achieved in 14 of grade 1 carcinomas (9.7%), 14 of grade 2 carcinomas (9.7%), and 15 of grade 3 carcinomas (10.5%). Discordance between grades 1 and 2 was observed in 28 cases (19.6%) and between grades 2 and 3 were observed in 68 cases (47.6%). 4 cases demonstrated a discrepancy between grades 1 and 3 (2.8%), 3 of which also showed a 1 to 3 category discrepancy in mitotic rate. None of these cases showed a 1 to 3 category discrepancy in tubule formation. In 1 case, there was an even split between pathologists in terms of grade. Excluding the single case with an even split between grades, complete concordance amongst all pathologists was observed in 56% (14/25), 20% (14/70), and 32% (15/47) of tumors with a modal grade 1, 2, and 3, respectively (p=0.003, chi-squared=24.7).

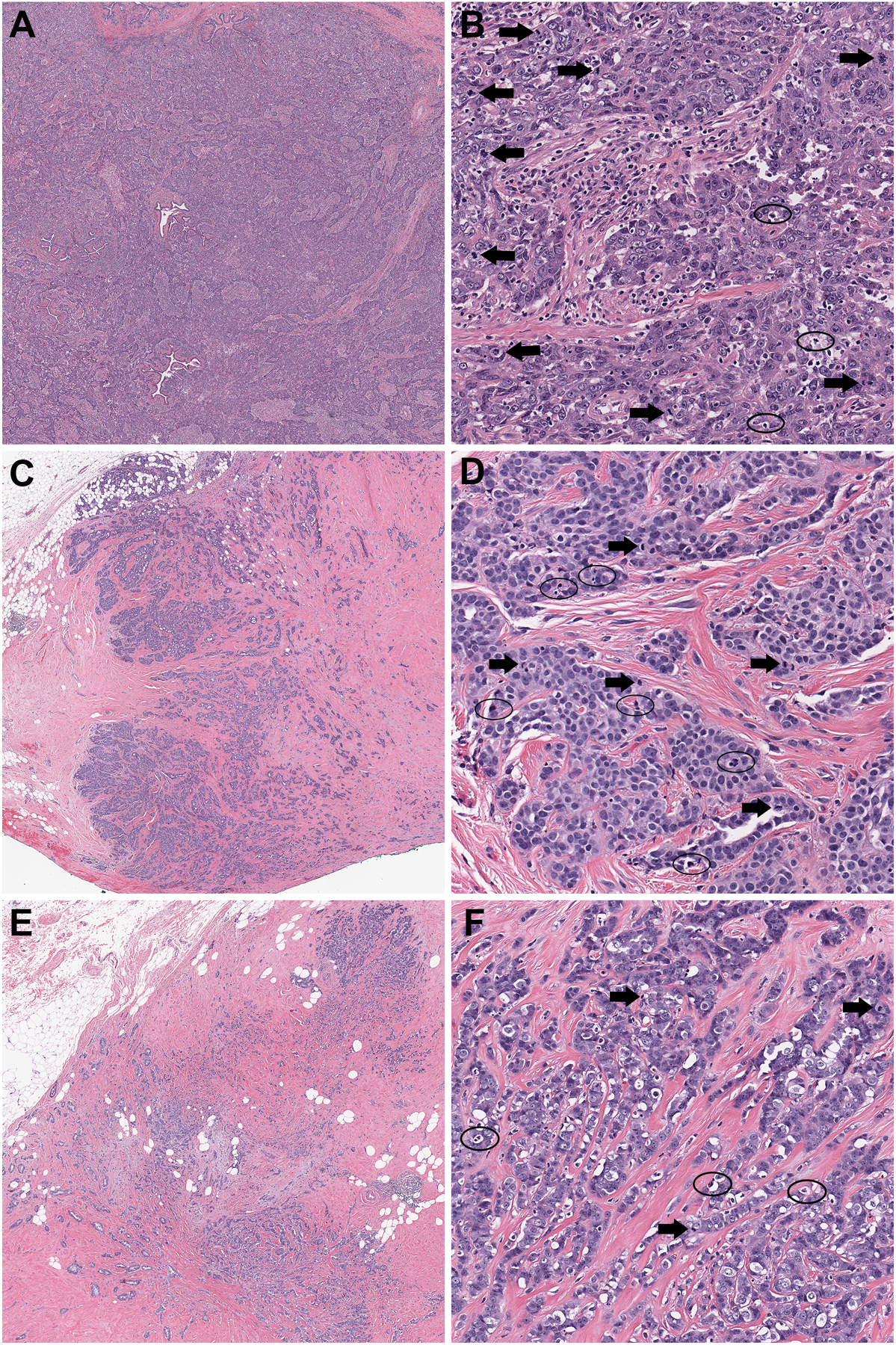

Figure 1.

Examples of Cases with Perfect and 2-step Discordance. (A) Whole slide scanned image of case with perfect overall grading concordance shows a homogenous tumor lacking any tubule formation. (B) On higher magnification, the carcinoma shows pronounced nuclear pleomorphism. The presence of apoptotic debris (circles) did not affect enumeration of the conspicuous mitoses (arrows). (C) Whole slide scanned image of case with 2-step overall grading discordance shows a tumor with variable tubule formation. (D) While nuclear pleomorphism was predominately intermediate, occasional higher grade cells were present (not shown). In this case, differentiating mitoses (arrows) from apoptotic debris (circles) likely contributed to a 2-step discordance in mitotic rates amongst the 6 pathologists. (E) Whole slide scanned image of case with 2-step overall grading discordance amongst pathologists shows a tumor with heterogeneous tubule formation. (F) Nuclear pleomorphism scoring was split evenly amongst pathologists between grades 2 and 3. Both heterogeneity in mitotic activity and difficulties in differentiating mitoses (arrows) from apoptotic debris (circles) likely contributed to a 2-step discordance in mitotic rates amongst the 6 pathologists.

For the individual components, perfect agreement was reached for tubule formation in 70 cases (49%), nuclear pleomorphism in 45 cases (31.5%), and mitotic activity in 28 cases (19.6%). Perfect agreement on grading was attained in 31 of 108 cases (28.7%) of invasive ductal (no special type) (IDC), 6 of 23 cases (26%) of invasive lobular (ILC), and 6 of 12 cases (50%) of special types of invasive carcinoma.

Overall Interobserver Variability in Breast Carcinoma Grading

Interobserver agreement for grade was moderate (κ=0.497), with the best agreement for grade 1 (κ=0.705), followed by grade 3 (κ=0.491), and only fair agreement for grade 2 (κ=0.375) (Table 2). For observer pairs, concordance ranged from fair to good (κ=0.354 to 0.684) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Interobserver Variability Based on Grade, Individual Grading Components, and Histopathologic Type

| Fleiss’ κa | |

|---|---|

| Histologic Grade | |

| 1 | 0.705 |

| 2 | 0.375 |

| 3 | 0.491 |

| Individual Grade Components | |

| Tubule Formation | 0.503 |

| Nuclear pleomorphism | 0.403 |

| Mitotic Rate | 0.281 |

| Tubule Formation | |

| 1 | 0.613 |

| 2 | 0.300 |

| 3 | 0.613 |

| Nuclear Pleomorphism | |

| 1 | 0.158 |

| 2 | 0.372 |

| 3 | 0.467 |

| Mitotic Rate | |

| 1 | 0.329 |

| 2 | 0.121 |

| 3 | 0.456 |

| Histopathologic Types | |

| IDC-NST | 0.490 |

| ILC | 0.092 |

| Other | 0.606 |

Fleiss’ κ scores denote levels of agreement: ≤0.20 = slight, 0.21–0.40 = fair, 0.41–0.60 = moderate, 0.61–0.80 = good, and 0.8–1.00 = very good

IDC = invasive ductal carcinoma-no special type; ILC = invasive lobular carcinoma

Table 3.

Pairwise Fleiss’ κa for Overall Grade Interobserver Variability

| P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | P6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 0.684 | 0.390 | 0.607 | 0.428 | 0.518 |

| P2 | 0.415 | 0.572 | 0.501 | 0.464 | |

| P3 | 0.354 | 0.563 | 0.430 | ||

| P4 | 0.469 | 0.617 | |||

| P5 | 0.532 |

Fleiss’ κ scores denote levels of agreement: ≤0.20 = slight, 0.21–0.40 = fair, 0.41–0.60 = moderate, 0.61–0.80 = good, and 0.8–1.00 = very good

Interobserver agreement was fair to moderate for the individual components with kappas of 0.281, 0.403, and 0.503 for mitotic rate, nuclear pleomorphism, and tubule formation, respectively (Table 2). For the individual categories of the grade components, the degree of agreement ranged from slight to good, with the least concordance for mitotic rate category 2 (κ=0.121) and the best concordance for tubule formation categories 1 and 3 (κ=0.613 each) (Table 2). Interobserver agreement was better for patients with invasive ductal (κ=0.490) than invasive lobular carcinomas (κ=0.092). Concordance was good for other types of invasive carcinomas (κ=0.606) (Table 2).

Impact of Interobserver Variability on Pathologic Prognostic Stage

Of the 143 cases, 127 were from patients with a single tumor evaluated for prognostic staging. For the 3 patients with bilateral tumors, both tumors were evaluated by prognostic staging. For the 4 patients with multiple histologically distinct ipsilateral tumors, the largest tumor was evaluated for prognostic staging. In 14 cases, lymph nodes were not submitted, precluding pathologic prognostic staging. These cases were excluded from the analysis. In all, 124 tumors were evaluated for the impact of interobserver variability on prognostic stage, of which 38 demonstrated complete agreement amongst pathologists in histologic grading of carcinoma. In all, there were 86 cases with discrepancies in histologic grading of carcinoma, of which 17 led to changes in prognostic staging (19.8%) (Table 4). Discrepancies in grading most frequently resulted in a change of stage from IA to IB (n=9; 10.4%), followed by IB to IIA (n=3, 3.5%), IB to IIB (n=3, 3.5%), and IIIA to IIIB (n=2, 2.3%). All of the cases in which discrepancies in grading lead to changes in the prognostic staging were HR-positive, HER2-negative/equivocal. Of the cases where discordances in grading lead to differences in prognostic stage, 8 cases had Oncotype DX testing performed. In two of these cases, the Oncotype DX recurrence score was <11, which would have resulted in a prognostic stage of 1A regardless of grade. For both of these cases, the discrepancy in grade resulted in a change from 1B to 1A.

Table 4.

Pathologic Prognostic Stage of Cases with Discordant Tumor Grades

Discrepancy resulted in change of prognostic stage

Confounders

Potential confounders that might affect variability were evaluated. These included experience, work setting (academic, nonacademic), type of microscope used (conventional LM, DM and conventional LM), time dedicated to breast pathology, nuclear grading in case of heterogeneity, the method used to determine the mitotic rate, and influence of special type classification on grading. No significant associations were observed for years of experience (when dichotomized based on ≤14 years versus >14 years) or the method used to determine the mitotic rate (P > 0.05) (Table 5). Since all the participating pathologists’ practice in a predominantly academic setting we cannot determine whether the interobserver agreement would differ in the community setting. The majority of pathologists in our study spent at least 40% of their time on breast sign-out so we cannot exclude the possibility that interobserver variability would be significantly different among pathologists that devote less than 40% of their time to breast sign-out. Finally, while we did not observe a difference in interobserver variability between pathologists that graded based on special type (i.e., cribriform, tubular, lobular, etc.) compared whose who did not, nor a difference in the habit of reporting nuclear grade in cases with heterogeneity, we lack the statistical power to confirm our observations.

Table 5.

Distribution of Answers of the 6 Participating Pathologists Regarding Potential Confounders that Might Influence the Degree of Interobserver Variability

| Question | Number (%) | P valuea |

|---|---|---|

| Provide years of experience (range: 4–25 years) | ||

| ≤14 years | 3 (50) | 0.42 |

| >14 years | 3 (50) | |

| Describe your work environment | ||

| Academic | 5 (83.3) | NA |

| Nonacademic | 0 | |

| Both academic and nonacademic | 1 (16.7) | |

| Describe your daily work method | ||

| Conventional light microscopy | 6 | NA |

| Digital and conventional microscopy | 0 | |

| Weekly amount of time dedicated to breast pathology | ||

| <20% (<1 day per week) | 0 | NA |

| ≥20 and <40% (between 1 and 2 days per week) | 1 (16.7) | |

| ≥40 and <60% (between 2 and 3 days per week) | 0 | |

| ≥60 and <80% (between 3 and 4 days per week) | 3 (50) | |

| ≥80 (>4 days per week | 2 (33.3) | |

| Which nuclear grade did you use in case of heterogeneity? | ||

| Highest grade | 4 (66.7) | NA |

| Predominant grade | 0 | |

| Both highest and predominant grade | 2 (33.3) | |

| What method did you use to determine mitotic rate? | ||

| Create Fixed Size Annotation - Score 10 Fixed Annotations | 3 (50) | 0.42 |

| Freehand Annotate Area to be Scored | 3 (50) | |

| Did you grade any tumors based on the fact that it represented a special type of invasive carcinoma? | ||

| Yes | 2 (33.3) | NA |

| No | 4 (66.7) |

P values calculated using t-test; NA = not applicable

Discussion

Breast cancer grading has been an important prognostic factor in breast carcinoma and with its incorporation into prognostic staging by the most recent AJCC staging manual continues to be a key pathologic feature used in the treatment of breast cancer patients.(6, 7, 24) The use of digital WSI and VM are increasingly being incorporated into routine clinical practice and may include sharing of digital WSIs in lieu of glass slides for second opinion diagnosis. As such, demonstrating reasonable concordance amongst pathologists using this platform, particularly at multiple institutions, is of the utmost importance. Refinements in breast carcinoma grading which include specific criteria for assessing tubule formation, nuclear pleomorphism, and mitotic scoring render this system amenable for assessing reproducibility amongst pathologists using digital WSI.(1, 5)

Many studies have been performed to evaluate the variability in pathologist breast carcinoma grading using LM. When compared to both single and multi-institution LM studies which have mostly demonstrated moderate to good levels of interobserver agreement, we found a similar rate of concordance in overall breast cancer grading using VM.(9, 14, 25–29) While our pairwise agreement which ranged from fair to good (κ=0.354 to 0.684) is similar to some studies,(30) others have demonstrated higher degrees of concordance.(14) Our results resembled those of other published studies wherein agreement for the individual components has mostly been fair to moderate.(9, 14) We too found that agreement for grade 2 tumors tended to fall below that of grade 1 and grade 3 tumors.(10, 28, 29) Similar to others, we found that variability was lowest for tubule formation.(14, 25, 26, 30) While some studies have also demonstrated the greatest variability for mitotic rate, (25, 26, 30) as was demonstrated in our study, others have observed greater variability in nuclear pleomorphism.(14, 28) Finally, this and other studies have shown that while discrepancies of one step (grade 1 versus grade 2, grade 2 versus grade 3) are common, with rare exceptions, discrepancies of more than one grade (i.e., grade 1 versus grade 3) were infrequent (1–5%).(9, 10, 12–14, 25, 30, 31) Our study showed that concordance using VM is not largely different from that observed in studies using LM.

Multi-institutional studies evaluating concordance of breast cancer grade using VM are limited.(32) In one such study, VM interobserver concordance performed on 40X magnification digital WSI for overall breast cancer grade was moderate and was similar to that observed using LM.(32) As for the individual components, agreement was greatest for tubule formation with moderate concordance (κ=0.54), followed by mitotic rate with fair concordance (κ=0.35), and worst for nuclear pleomorphism with only slight concordance (κ=0.15).(32) These results are mostly similar to our findings, however, the reason for the slight agreement for the nuclear pleomorphism component of the grading system in their study is unclear. Other studies that have evaluated breast cancer grading using VM primarily compared VM to LM grade and studied intraobserver variability using VM.(12, 13) In these studies, VM breast cancer grading performed on 20X magnification digital WSI was compared to the routinely reported grade using LM.(12, 13) Overall concordance between VM and LM was moderate (unweighted κ=0.51). In their study, Rahka et al. showed that VM tends to downgrade tumors, a finding that they attributed to a relatively reduced ability to identify mitotic counts on the screen, which in part could be due to scanning at 20X magnification.(12, 13) While we and others scanned slides at 40X magnification, only slight concordance for mitotic rate was observed. This is an interesting observation that may be related to the inability to assess different planes on VM, however, requires further consideration in future studies. While beyond the scope of this study, VM lends itself well to the use of artificial intelligence (AI) programs such as mitotic recognition software which may be useful in the future as a means to improve concordance in mitotic scoring.(33–35) This assertion is supported by a recent study that demonstrated improved accuracy, precision and sensitivity of counting mitoses by pathologists at all levels of experience with the assistance of AI software.(36) This certainly deserves further study. As there was no attempt to guide reviewers to a single designated area on the slide, it is also possible that some interobserver disagreement could be due to differences in the participating pathologists’ selection of the optimum area for mitotic counts. Since both the Fixed Size and Freehand Annotation methods for determining the mitotic rates were equally split amongst pathologists, it seems less likely that the method used influenced variability.

The impact of interobserver variability on breast cancer grading and it’s consequence on AJCC prognostic staging is limited.(14) One study showed that of 100 cases, discordance resulted in differences in prognostic staging in 25 and 29 cases during two rounds of scoring for an average rate of prognostic stage change of 27%. In both rounds, a change from stage IA to IB was the most common (18 and 21 cases, respectively). Less frequently changes from IA to IIA, IB to IIA, IB to IIB, and IIIB to IIIC were also observed.(14) We too found that discordant grading amongst pathologists leads to changes in prognostic staging at a rate of 19.8%. Similarly, we most frequently noted changes from IA to IB (10.4%) and fewer cases of IB to IIA (3.5%), IB to IIB (3.5%), and IIIA to IIIB (2.3%). While we found that changes in prognostic staging were limited to HR-positive, HER2-negative/equivocal tumors in this cohort, there are circumstances in which grading discrepancies can result in alterations in prognostic staging for triple-negative tumors (e.g. change from 1B to 1A in a triple-negative, grade 2–3 versus 1 tumor). While we did not observe alterations in prognostic stage due to grading discrepancies in triple-negative breast carcinoma, the limited number of cases in our cohort (n=10) likely contributed to this finding, and ought to be confirmed in a larger cohort. Finally, in contrast, HR-negative, HER2-positive tumors are not susceptible to prognostic staging changes based on grading discrepancies. While the Rabe et al. study was unable to evaluate the impact of Oncotype DX testing on prognostic staging in discordant cases, we found that for two cases where the discrepancy in grade resulted in a change from prognostic stage group 1B to 1A, Oncotype DX results would have also downgraded these cases to 1A. We only had Oncotype DX results from 8 of 17 cases with grading discrepancies that resulted in changes in prognostic stage groups. While Oncotype DX results may ultimately be used to determine PS despite grade in some cases, we must acknowledge that Oncotype DX and grading are two different tools used for prognostication and one cannot be used to mitigate the variability of other. Additional studies would be necessary to provide a more insight into the clinical significance of Oncotype DX results in cases with discrepancies in grading.

We were unable to determine the impact of work setting (academic, nonacademic), type of microscope used (conventional LM, DM and conventional LM), and time dedicated to breast pathology in grading variability due to the similarities in practice amongst the participating pathologists. We also lacked statistical power to evaluate other potential confounders such as differences in interobserver variability between pathologists that graded based on special type (i.e., cribriform, tubular, lobular, etc.) compared whose who did not, nor a difference in the habit of reporting nuclear grade in cases with heterogeneity. As we did not require pathologists to save annotations used for determining mitotic rates, we are unable to determine whether area selection influenced discordance in this parameter. We recognize that pathologists in our study were split in their approach to scoring nuclear grade in cases of heterogeneity, grading tumors of special type, and the approach used to determine mitotic rate by VM. This would suggest that further clarification regarding standardization of histologic grading in these settings, particularly when grading using VM would be beneficial to the pathology community at large and requires further study.

Our cohort was biased towards HR-positive, HER2-negative tumors, and there was a paucity of HR-negative tumors. This bias may have resulted in increased variability because HR-positive, HER2-negative tumors are commonly graded as grade 2 and also limited our ability to evaluate the effect of grading discordance on prognostic staging in the triple-negative breast carcinoma subtype.

Using VM, a multi-institutional cohort of pathologists showed moderate concordance for breast cancer grading, a finding similar to that seen in studies using light microscopy. Agreement was the best at the extremes of grade and for evaluation of tubule formation. How VM influences the variability of mitotic rate remains to be elucidated. The clinical relevance of how grading discrepancies affect prognostic staging and the impact of Oncotype DX results in determining PS in cases with grading discrepancies require further study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Translational Research Program at Weill-Cornell Medicine Pathology and Laboratory Medicine. This research was supported in part through the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748.

Footnotes

Disclosure/Conflict of Interest

The authors have no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

References:

- 1.Elston CW, Ellis IO. Pathological prognostic factors in breast cancer. I. The value of histological grade in breast cancer: experience from a large study with long-term follow-up. Histopathology 1991;19:403–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bloom HJ. Further studies on prognosis of breast carcinoma. Br J Cancer 1950;4:347–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bloom HJ. Prognosis in carcinoma of the breast. Br J Cancer 1950;4:259–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bloom HJ, Richardson WW. Histological grading and prognosis in breast cancer; a study of 1409 cases of which 359 have been followed for 15 years. Br J Cancer 1957;11:359–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elston CW. The assessment of histological differentiation in breast cancer. Aust N Z J Surg 1984;54:11–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rakha EA, El-Sayed ME, Lee AHS, Elston CW, Grainge MJ, Hodi Z, et al. Prognostic significance of Nottingham histologic grade in invasive breast carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:3153–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amin MB, American Joint Committee on Cancer., American Cancer Society. AJCC cancer staging manual. Eight edition / editor-in-chief, Amin Mahul B., MD, FCAP ; editors, Edge Stephen B., MD, FACS and 16 others ; Gress Donna M., RHIT, CTR - Technical editor ; Meyer Laura R., CAPM - Managing editor. ed. American Joint Committee on Cancer, Springer: Chicago IL, 2017. xvii, 1024 pages pp. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li X, Zhang Y, Meisel J, Jiang R, Behera M, Peng L. Validation of the newly proposed American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) breast cancer prognostic staging group and proposing a new staging system using the National Cancer Database. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2018;171:303–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meyer JS, Alvarez C, Milikowski C, Olson N, Russo I, Russo J, et al. Breast carcinoma malignancy grading by Bloom-Richardson system vs proliferation index: reproducibility of grade and advantages of proliferation index. Mod Pathol 2005;18:1067–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Delides GS, Garas G, Georgouli G, Jiortziotis D, Lecca J, Liva T, et al. Intralaboratory variations in the grading of breast carcinoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1982;106:126–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robbins P, Pinder S, de Klerk N, Dawkins H, Harvey J, Sterrett G, et al. Histological grading of breast carcinomas: a study of interobserver agreement. Hum Pathol 1995;26:873–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rakha EA, Aleskandarani M, Toss MS, Green AR, Ball G, Ellis IO, et al. Breast cancer histologic grading using digital microscopy: concordance and outcome association. J Clin Pathol 2018;71:680–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rakha EA, Aleskandarany MA, Toss MS, Mongan NP, ElSayed ME, Green AR, et al. Impact of breast cancer grade discordance on prediction of outcome. Histopathology 2018;73:904–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rabe K, Snir OL, Bossuyt V, Harigopal M, Celli R, Reisenbichler ES. Interobserver variability in breast carcinoma grading results in prognostic stage differences. Hum Pathol 2019;94:51–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Janabi S, Huisman A, Van Diest PJ. Digital pathology: current status and future perspectives. Histopathology 2012;61:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Allen TC. Digital pathology and federalism. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2014;138:162–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brachtel E, Yagi Y. Digital imaging in pathology--current applications and challenges. J Biophotonics 2012;5:327–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hedvat CV. Digital microscopy: past, present, and future. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2010;134:1666–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kayser K Introduction of virtual microscopy in routine surgical pathology--a hypothesis and personal view from Europe. Diagn Pathol 2012;7:48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rocha R, Vassallo J, Soares F, Miller K, Gobbi H. Digital slides: present status of a tool for consultation, teaching, and quality control in pathology. Pathol Res Pract 2009;205:735–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.FDA allows marketing of first whole slide imaging system for digital pathology. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-allows-marketing-first-whole-slide-imaging-system-digital-pathology. 2017.

- 22.Fleiss JL, Levin B, Paik MC. Statistical methods for rates and proportions. 3rd ed. J. Wiley: Hoboken, N.J., 2003. xxvii, 760 p. pp. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977;33:159–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Page DL, Gray R, Allred DC, Dressler LG, Hatfield AK, Martino S, et al. Prediction of node-negative breast cancer outcome by histologic grading and S-phase analysis by flow cytometry: an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study (2192). Am J Clin Oncol 2001;24:10–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boiesen P, Bendahl PO, Anagnostaki L, Domanski H, Holm E, Idvall I, et al. Histologic grading in breast cancer--reproducibility between seven pathologic departments. South Sweden Breast Cancer Group. Acta Oncol 2000;39:41–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chowdhury N, Pai MR, Lobo FD, Kini H, Varghese R. Impact of an increase in grading categories and double reporting on the reliability of breast cancer grade. APMIS 2007;115:360–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harvey JM, de Klerk NH, Sterrett GF. Histological grading in breast cancer: interobserver agreement, and relation to other prognostic factors including ploidy. Pathology 1992;24:63–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Longacre TA, Ennis M, Quenneville LA, Bane AL, Bleiweiss IJ, Carter BA, et al. Interobserver agreement and reproducibility in classification of invasive breast carcinoma: an NCI breast cancer family registry study. Mod Pathol 2006;19:195–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Postma EL, Verkooijen HM, van Diest PJ, Willems SM, van den Bosch MA, van Hillegersberg R. Discrepancy between routine and expert pathologists’ assessment of non-palpable breast cancer and its impact on locoregional and systemic treatment. Eur J Pharmacol 2013;717:31–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang R, Chen HJ, Wei B, Zhang HY, Pang ZG, Zhu H, et al. Reproducibility of the Nottingham modification of the Scarff-Bloom-Richardson histological grading system and the complementary value of Ki-67 to this system. Chin Med J (Engl) 2010;123:1976–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dalton LW, Pinder SE, Elston CE, Ellis IO, Page DL, Dupont WD, et al. Histologic grading of breast cancer: linkage of patient outcome with level of pathologist agreement. Mod Pathol 2000;13:730–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shaw EC, Hanby AM, Wheeler K, Shaaban AM, Poller D, Barton S, et al. Observer agreement comparing the use of virtual slides with glass slides in the pathology review component of the POSH breast cancer cohort study. J Clin Pathol 2012;65:403–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Balkenhol MCA, Tellez D, Vreuls W, Clahsen PC, Pinckaers H, Ciompi F, et al. Deep learning assisted mitotic counting for breast cancer. Lab Invest 2019;99:1596–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Couture HD, Williams LA, Geradts J, Nyante SJ, Butler EN, Marron JS, et al. Image analysis with deep learning to predict breast cancer grade, ER status, histologic subtype, and intrinsic subtype. NPJ Breast Cancer 2018;4:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Veta M, van Diest PJ, Willems SM, Wang H, Madabhushi A, Cruz-Roa A, et al. Assessment of algorithms for mitosis detection in breast cancer histopathology images. Med Image Anal 2015;20:237–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pantanowitz L, Hartman D, Qi Y, Cho EY, Suh B, Paeng K, et al. Accuracy and efficiency of an artificial intelligence tool when counting breast mitoses. Diagn Pathol 2020;15:80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.