Abstract

Background:

Whereas it is plausible that unconventional natural gas development (UNGD) may adversely affect cardiovascular health, little is currently known. We investigate whether UNGD is associated with acute myocardial infarction (AMI).

Methods:

In this observational study leveraging the natural experiment generated by New York’s ban on hydraulic fracturing, we analyzed the relationship between age- and sex-specific county-level AMI hospitalization and mortality rates and three UNGD drilling measures. This longitudinal panel analysis compares Pennsylvania and New York counties on the Marcellus Shale observed over 2005-2014 (N=2,840 county-year-quarters).

Results:

A hundred cumulative wells is associated with 0.26 more hospitalizations per 10,000 males 45-54y.o. (95% CI 0.07,0.46), 0.40 more hospitalizations per 10,000 males 65-74y.o. (95% CI 0.09,0.71), 0.47 more hospitalizations per 10,000 females 65-74y.o. (95% CI 0.18,0.77) and 1.11 more hospitalizations per 10,000 females 75y.o.+ (95% CI 0.39,1.82), translating into 1.4-2.8% increases. One additional well per square mile is associated with 2.63 more hospitalizations per 10,000 males 45-54y.o. (95% CI 0.67,4.59) and 9.7 hospitalizations per 10,000 females 75y.o.+ (95% CI 1.92,17.42), 25.8% and 24.2% increases respectively. As for mortality rates, a hundred cumulative wells is associated with an increase of 0.09 deaths per 10,000 males 45-54y.o. (95% CI 0.02,0.16), a 5.3% increase.

Conclusions:

Cumulative UNGD is associated with increased AMI hospitalization rates among middle-aged men, older men and older women as well as with increased AMI mortality among middle-aged men. Our findings lend support for increased awareness about cardiovascular risks of UNGD and scaled-up AMI prevention as well as suggest that bans on hydraulic fracturing can be protective for public health.

Keywords: environmental health, cardiovascular health, unconventional natural gas development, fracking, industrial emissions

1. Introduction

There were an estimated 7.29 million acute myocardial infarctions (AMI) worldwide in 2015.1 In addition to established modifiable risk factors of AMI such as smoking, obesity, and high blood pressure, stress and air pollution are increasingly seen as contributing factors. A growing body of research demonstrates associations between stress and acute cardiac events, including AMI.2,3 Exposure to air pollution is recognized as a significant risk factor of cardiovascular disease by the American Heart Association4 and the European Society of Cardiology,5 based on empirical research confirming associations of specific air pollutants with cardiovascular disease, including AMI.6,7

Unconventional natural gas development (UNGD), commonly known as fracking, has boomed in the United States, especially Pennsylvania, and is a growing source of air pollution from particulate matter and volatile organic compounds8,9 as well as stress,10,11 including potential psychological stress and physical stressors such as noise and light,12,13 and may thus be harmful for cardiovascular health. There is growing evidence of adverse effects of UNGD on health;14-16,8,17 in particular, recent work has shown that the intensity of oil and gas development and production is positively associated with augmentation index, blood pressure, and inflammatory markers associated with stress and short-term air pollution exposure (IL-1β, TNF-α).18 However, the association of UNGD with AMI morbidity and mortality is largely unknown.

The objective of this observational study was to investigate how UNGD is associated with AMI hospitalizations and mortality. We leverage a natural experiment, generated by the New York state ban on hydraulic fracturing (a type of UNGD), to examine this relationship in Pennsylvania and New York. Pennsylvania’s Northern and Western counties experienced extensive drilling over the past two decades, whereas drilling in New York’s Southern Tier counties – though geologically possible – is prohibited. Given the potential pathways of air pollution and stress, we hypothesize that there is a positive association between UNGD and AMI.

2. Methods

We leveraged the natural experiment generated by differences in energy policy between Pennsylvania and New York. Large portions of both states sit atop the Marcellus Shale and have viable UNGD geology. Pennsylvania has experienced an extensive growth in UNGD in the last two decades (over eight thousand wells drilled by the end of 2014). The oil and gas industry projected intensive development of UNGD wells in New York, but faced a fierce political debate. At the community level, there were movements both in support of and against UNGD,19 leading multiple municipalities to enact local moratoria. New York imposed a state-wide moratorium on hydraulic fracturing in 2010 and banned the practice in 2014. Anti-fracking movements and the subsequent moratoria and bans were primarily politically driven.20-22 As a result of these regulations, New York’s Southern Tier counties, where UNGD is geologically possible, did not experience any unconventional drilling. This difference in energy policy presents a unique natural experiment in which the association between UNGD and health can be examined in demographically similar communities, thus countering a potential selection bias. With the ban being a product of political opposition to UNGD, it is largely exogenous to unobserved influences on health.

2.1. Study Population

We examined population aged 45y.o. and older, in whom incidence of AMI is non-trivial,23 in Pennsylvania and New York counties that overlay the Marcellus Shale. We obtained 2005-2014 data on hospital discharges from Pennsylvania Health Care Cost Containment Council (PHC4) and New York’s Statewide Planning and Research Cooperative System (SPARCS) and all-cause mortality data from the United States’ National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS).

2.2. Measures

We identified hospitalizations with the principal diagnosis of AMI (ICD-9-CM 410) and decedents with AMI as the recorded underlying cause of death (ICD-10 I21-I22). We grouped these into eight pre-specified categories by sex and the following age categories: 45-54y.o., 55-64y.o., 65-74y.o., and 75y.o.+, and calculated age- and sex-specific quarterly county-level hospitalization and mortality rates per 10,000 residents. Population estimates are from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program. There were missing values in age and gender in hospitalization data, constituting less than 0.01% individual records; these records were excluded from analyses. There were no missing values in variables of interest in mortality data.

For UNGD exposure metrics, we used county-level measures for drilled wells in a quarter-year (contemporaneous drilled wells) and two cumulative well measures: well count (total number of wells drilled up to the end of the quarter-year) and well density (cumulative well count divided by county land area in square miles). We focused on drilled wells because activities associated with unconventional drilling and its infrastructure produce air, noise, and light pollution. We obtained UNGD data from the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, who maintain detailed geocoded records on UNGD activity in Pennsylvania.24

In each age- and sex-specific model, adjustment was made for the proportion of the age-sex group in the total county population as well as the racial and ethnic composition of the age-sex group (using SEER program data). We also included annual county-level economic and health care factors: unemployment rate, poverty rate, median household income, and the total number of hospitals. Poverty estimates and median income data came from Small Area Income and Poverty Estimates (SAIPE) and unemployment rates from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Annual county-level hospital counts are from the Area Health Resource File.25 Finally, we adjusted for county-level uninsured rates in models for ages 45-54 and 55-64. The data on uninsured rates came from Small Area Health Insurance Estimates (SAHIE) Program. We added sex-specific uninsured rates among 40-64y.o. (the closest age group available in SAHIE data). SAHIE data do not include uninsured rate among those aged 65 and older because the uninsured rate in this population is negligible due to Medicare eligibility, and models for ages 65-74 and 75 and older do not include this variable. All covariates are year varying and data for 2005-2014 were used.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

We investigated the relationship between exposure to UNGD and AMI hospitalization and AMI mortality rates in a longitudinal panel analysis of Pennsylvania and New York counties with any Marcellus shale coverage. Our panel consists of 47 counties in Pennsylvania and 24 counties in New York observed over 40 quarter-years (2005-2014) (N=2,840 county-year-quarters). The list of counties is provided in Table S1. In addition to adjustment for time-varying county characteristics described above, our model includes quarter-year fixed effects, which account for time trends in the outcomes, and county fixed effects, which adjust for county-specific time-invariant characteristics. Additionally, we adjusted for state-specific time trends by including a state-by-year interaction. We report heteroscedasticity-robust (Huber-White) standard errors, clustered at county level.

We performed several sensitivity analyses. First, we sought to remove potential air pollution confounding in large urban areas by excluding central and fringe metropolitan counties based on the classification by the National Center for Health Statistics (remaining N=2,360 county-year-quarters).1 In another sensitivity check, we excluded counties with shale coverage of less than 30% (remaining N=2,480 county-year-quarters).2 Further, we excluded both large metropolitan counties and counties with shale coverage of less than 30% (remaining N=2,160 county-year-quarters). In another analysis, we excluded Southwestern Pennsylvania counties (remaining N=2,320 county-year-quarters),3 which have experienced historical conventional drilling and are more urban and densely populated than New York’s Southern Tier. Finally, we adjusted for county-level coal production because air pollution from the coal industry may affect cardiovascular health independently from UNGD. Mine-level coal production data came from the Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA).

We performed two additional analyses to present a more comprehensive picture on the relationship between UNGD and AMI. First, we examined the relationship between UNGD measures and AMI hospitalizations and mortality in Pennsylvania’s more exposed counties vs New York. Specifically, we retained Pennsylvania counties that by the end of 2014 had the number of wells above the median (over 20 wells), analyzing 23 Pennsylvania counties and 24 New York counties (remaining N=1,880 county-year-quarters). Second, we performed a within-Pennsylvania analysis, using Pennsylvania counties with any Marcellus Shale coverage (47 counties, N=1,880 county-year-quarters). While our main approach, which uses a natural experiment, should be less confounded, we present this analysis because this approach is in line with most of the prior studies on UNGD in Pennsylvania.14-16

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

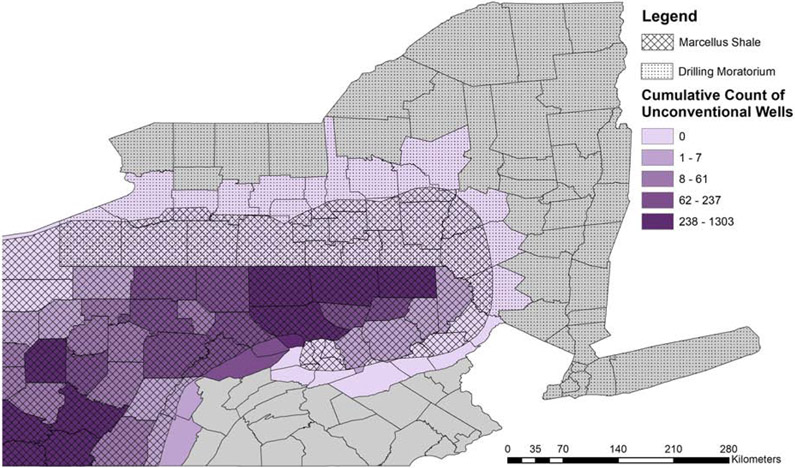

Descriptive statistics are reported in Table 1. While no unconventional wells were drilled in New York, unconventional drilling increased dramatically in Pennsylvania, from an average of 0.027 to 6.35 wells drilled in a quarter-year from 2005 to 2014. Cumulatively, the average cumulative number of drilled wells increased from 0.17 at the end of 2005 to 177.6 at the end of 2014, with considerable variation across counties (Figure 1). Between 2005 and 2014, average county-quarter AMI hospitalization and AMI mortality rates exhibited decreasing trends, in both states, with consistently higher rates in Pennsylvania (Table 1; Figures S1-2). Demographically, the two states appear comparable, with Pennsylvania’s counties on the Marcellus Shale being slightly less diverse than New York’s Southern Tier. The states are comparable in economic characteristics as well. The total number of hospitals decreased in both regions.

Table 1.

Summary Statistics, Pennsylvania and New York Counties on the Marcellus Shale, 2005 and 2014.

| Variables: Means (Std. Dev.) | PA | NY | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 2014 | 2005 | 2014 | |

| UNGD exposure measures | ||||

| Contemporaneous spudded wellsa | 0.027 (0.192) | 6.35 (14.62) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) |

| Cumulative well countb | 0.17 (0.56) | 177.6 (340.1) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) |

| Cumulative well density (per sq.mile)b | 0.0002 (0.0006) | 0.21 (0.38) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) |

| AMI hospitalization ratesa | ||||

| Male | ||||

| 45-54 y.o. | 10.24 (7.50) | 8.00 (5.95) | 7.64 (5.05) | 6.01 (4.31) |

| 55-64 y.o. | 17.10 (9.75) | 15.18 (8.16) | 14.18 (6.67) | 10.82 (6.24) |

| 65-74 y.o. | 28.88 (14.33) | 21.53 (10.36) | 24.37 (14.57) | 14.31 (8.86) |

| 75+ y.o. | 51.57 (26.52) | 40.35 (17.55) | 41.25 (19.37) | 25.85 (15.77) |

| Female | ||||

| 45-54 y.o. | 3.28 (4.29) | 3.23 (3.12) | 2.58 (2.66) | 2.55 (2.60) |

| 55-64 y.o. | 8.61 (6.81) | 5.73 (4.34) | 6.60 (4.21) | 4.58 (3.95) |

| 65-74 y.o. | 16.62 (12.15) | 12.53 (8.42) | 13.70 (9.78) | 8.03 (6.84) |

| 75+ y.o. | 39.89 (21.34) | 28.74 (12.92) | 34.14 (19.83) | 21.01 (12.88) |

| AMI mortality ratesa | ||||

| Male | ||||

| 45-54 y.o. | 1.67 (2.43) | 1.18 (2.17) | 0.81 (1.74) | 0.74 (1.68) |

| 55-64 y.o. | 3.58 (4.05) | 2.59 (3.79) | 3.03 (3.10) | 1.75 (2.23) |

| 65-74 y.o. | 8.03 (9.92) | 4.59 (5.05) | 5.36 (5.35) | 3.66 (4.00) |

| 75+ y.o. | 17.86 (11.98) | 13.22 (12.43) | 18.00 (16.13) | 13.49 (11.06) |

| Female | ||||

| 45-54 y.o. | 0.51 (1.89) | 0.29 (1.68) | 0.27 (0.76) | 0.21 (0.57) |

| 55-64 y.o. | 1.08 (1.64) | 0.99 (2.33) | 0.83 (1.62) | 0.56 (1.00) |

| 65-74 y.o. | 2.91 (4.01) | 2.05 (2.57) | 3.64 (4.75) | 2.02 (2.73) |

| 75+ y.o. | 13.82 (9.59) | 8.93 (6.68) | 14.94 (14.92) | 10.11 (8.63) |

| Demographic characteristicsc | ||||

| % white | 95.9 (3.6) | 94.7 (4.4) | 94.0 (4.4) | 92.6 (5.0) |

| % black | 3.2 (3.2) | 4.0 (3.9) | 4.1 (3.5) | 4.8 (3.7) |

| % other | 0.9 (0.8) | 1.3 (1.0) | 1.9 (1.8) | 2.6 (2.3) |

| % Hispanic | 1.7 (1.8) | 2.6 (2.7) | 2.8 (2.1) | 3.8 (2.7) |

| % Non-Hispanic | 98.3 (1.8) | 97.4 (2.7) | 97.2 (2.1) | 96.2 (2.7) |

| % female | 50.3 (2.4) | 49.7 (2.9) | 50.3 (1.4) | 50.1 (1.3) |

| % male | 49.7 (2.4) | 50.3 (2.9) | 49.7 (1.4) | 49.9 (1.3) |

| % 0-44 y.o. | 55.9 (3.4) | 51.6 (4.0) | 58.9 (3.0) | 54.3 (3.3) |

| % 45-54 y.o. | 15.4 (0.9) | 14.3 (1.0) | 15.1 (0.8) | 14.2 (1.1) |

| % 55-64 y.o. | 11.9 (1.1) | 14.9 (1.3) | 11.4 (1.0) | 14.4 (1.0) |

| % 65-74 y.o. | 8.3 (1.0) | 10.5 (1.4) | 7.3 (0.9) | 9.7 (1.1) |

| % 75+ y.o. | 8.5 (1.3) | 8.6 (1.1) | 7.2 (1.0) | 7.5 (0.9) |

| Total population, 45+ y.o. | 52,237 (80,807) | 55,932 (83,494) | 53,926 (78,497) | 58,704 (83,910) |

| Economic characteristicsc | ||||

| % in poverty | 12.9 (2.6) | 14.3 (2.5) | 13.3 (2.3) | 15.5 (2.4) |

| % unemployed | 5.6 (0.8) | 6.3 (0.9) | 4.9 (0.5) | 6.1 (0.6) |

| Median income ($2010) | 42,486 (5,296) | 43,157 (4,987) | 45,488 (3,818) | 44,950 (3,554) |

| Health care system characteristicsc | ||||

| Total number of hospitals | 3.1 (4.5) | 2.7 (4.0) | 2.7 (2.7) | 2.5 (2.3) |

Notes: Abbreviations: PA = Pennsylvania, UNGD = unconventional natural gas development, AMI = acute myocardial infarction, y.o. = years old, Std. Dev. = standard deviation.

Mean across county-quarters in each year and state (standard deviation in parentheses).

Mean across counties in quarter 4, i.e. at the end of the year (because UNGD measures are cumulative) (standard deviation in parentheses).

Mean across county-years (standard deviation in parentheses). Percentages do not add up to 100.0 in several cases due to rounding.

Figure 1. Cumulative Count of Unconventional Drilling Wells in Pennsylvania and New York through End of 2014.

Note: The map was created in ArcGIS

3.2. UNGD and AMI Hospitalizations

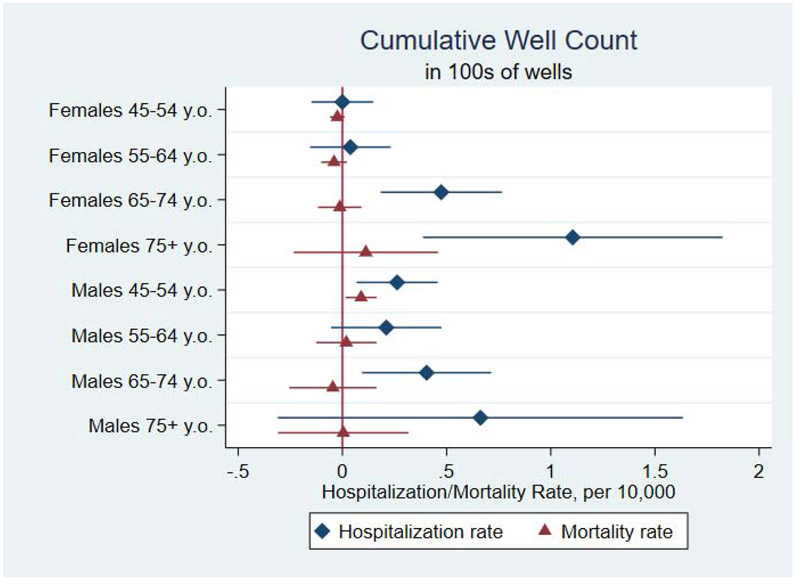

Figures 2-4 plot regression estimates from hospitalization and mortality models. Cumulative UNGD measures have a statistically significant positive association with AMI hospitalization rates among middle-aged men and older men and women. Figure 2 shows that for males aged 45-54, a hundred additional wells in a county is associated, on average, with 0.26 more hospitalizations per 10,000 (95% CI, 0.07, 0.46; P=.009), and for males aged 65-74, with 0.40 more hospitalizations per 10,000 (95% CI, 0.09, 0.71; P=.011). As for females, a hundred additional wells is associated with 0.47 more hospitalizations per 10,000 of 65-74y.o. (95% CI, 0.18, 0.77; P=.002), and 1.11 more hospitalizations per 10,000 of 75y.o. or older (95% CI, 0.39, 1.82; P=.003) (Figure 2). These estimates translate into 2.5% and 1.4% relative increases among the two male groups and 2.8% relative increases in both female groups. Figures S1 show unadjusted trends in AMI hospitalizations for the four groups by state.

Figure 2. Associations between UNGD Cumulative Well Count and AMI Hospitalization and Mortality Rates, by Sex and Age Group.

Note: Coefficients represent associations between one hundred cumulative wells and rates per 10,000 county residents in the age-by-sex group. Length of bars represents 95% confidence intervals.

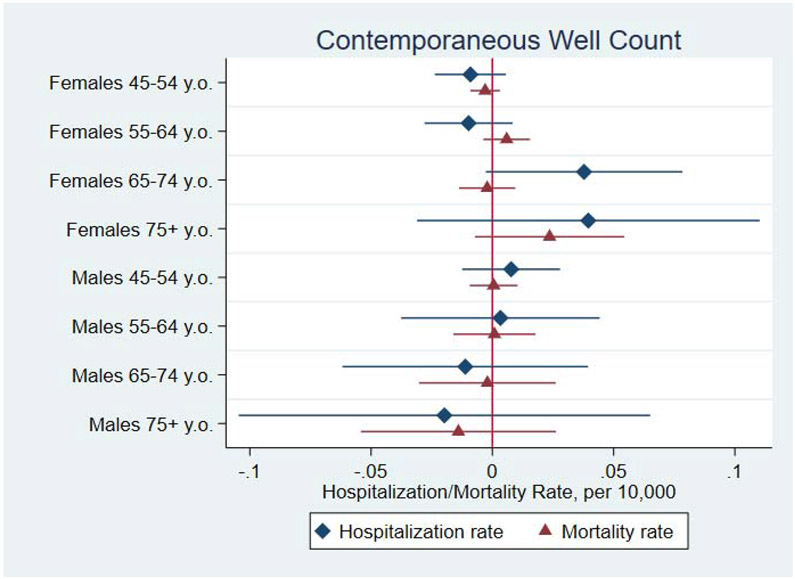

Figure 4. Associations between UNGD Contemporaneous Well Count and AMI Hospitalization and Mortality Rates, by Sex and Age Group.

Note: Coefficients represent associations between one contemporaneously drilled well and rates per 10,000 county residents in the age-by-sex group. Length of bars represents 95% confidence intervals.

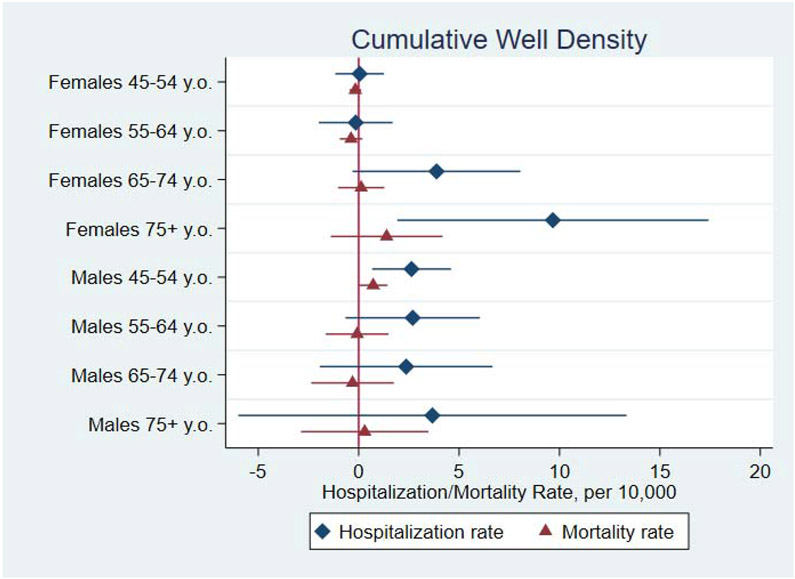

For cumulative well density (Figure 3), we found that an additional cumulative well per square mile is associated, on average, with 2.63 more hospitalizations per 10,000 males aged 45-54 (95% CI, 0.67, 4.59; P=.009) and 9.67 more hospitalizations per 10,000 females aged 75 or older (95% CI, 1.92, 17.42; P=.015), translating into 25.8% and 24.2% relative increases, respectively. These estimates were robust to all sensitivity analyses (Figures S3-4). As for the contemporaneous wells measure of UNGD, we did not find evidence of associations between with AMI hospitalizations in any age-by-sex groups (Figure 4).

Figure 3. Associations between UNGD Cumulative Well Density and AMI Hospitalization and Mortality Rates, by Sex and Age Group.

Note: Coefficients represent associations between one cumulative well per square mile and rates per 10,000 county residents in the age-by-sex group. Length of bars represents 95% confidence intervals.

3.3. UNGD and AMI Mortality

We found a statistically significant positive association between cumulative well count and AMI mortality rate among men 45-54y.o. A hundred additional cumulative wells in a county-quarter is associated, on average, with 0.09 more deaths per 10,000 males aged 45-54 (95% CI, 0.02, 0.16; P=.02) (Figure 2), a 5.4% relative increase. This estimate was robust in all sensitivity analyses (Figure S3). Associations between mortality and UNGD in other age-by-sex groups and in models with cumulative well density and contemporaneous well count were not statistically significant (Figures 2-4). Figures S2 show unadjusted trends in AMI mortality for the four groups by state.

3.4. Additional Analyses

When examining associations between UNGD and AMI hospitalizations and mortality using Pennsylvania counties with cumulative wells above the median, we did not find a convincing change in our key findings (Table S2, column 2). While for 65-74y.o. age groups, our findings are less statistically precise, which may be the product of the smaller number of observations, magnitudes of associations and 95% confidence intervals are comparable to our main specification findings. For females 75+y.o. and males 45-54y.o., findings from this model are consistent with our main analysis, both statistically and in magnitude. The within-Pennsylvania analysis findings are very similar to our main approach (Table S2, column 3), both statistically and in magnitude.

4. Discussion

We investigated how UNGD is associated with AMI hospitalizations and mortality. We found that long-term exposure to UNGD is associated with increased AMI hospitalization rates among middle-aged men and older men and women as well as increased AMI mortality rates among middle-aged men. A hundred cumulative unconventional wells drilled in a county is significantly associated with 1.4%-2.8% increases in AMI hospitalizations with varying magnitude in age-by-sex group and with a 5.4% increase in AMI deaths among men 45-54y.o.

To put this into perspective, three Pennsylvania counties – Bradford, Washington, and Susquehanna (comprising 313,798 people in 2010 over 7,320 km2 in total) – each had over a thousand unconventional wells by the end of 2014, with hundreds more drilled since then. Not coincidentally, these three counties are the ones with the most individual cardiovascular health complaints submitted to the Pennsylvania Department of Health between 2011 and February 2018.26

Our findings reflect the AMI age differentials by sex among Americans: average age at first MI is 65.3 years among males and 71.8 among females.23 With AMI mortality and hospitalizations decreasing between 2005 and 2014, our findings should be interpreted as reflecting attenuated decreases in AMI hospitalizations and deaths in areas with intensive UNGD. Although cardiovascular mortality has been declining for decades in the United States,27,28 the rate of decline was much lower in 2011-2014 than in 2000s.28,29

Our findings are consistent with the previous, though scarce, literature on the link between UNGD and cardiovascular hospitalizations. One small-scale study found relationships between cumulative wells and increased risk of cardiovascular hospitalizations.30 In our, larger-scale investigation, we show positive associations of cumulative UNGD measures with hospitalizations for AMI, a specific cardiovascular condition a priori hypothesized to be affected. Another previous study has examined UNGD and AMI hospitalizations among middle-aged and older adults.31 It reports associations of UNGD production with an increased risk of hospitalization among patients 45-64y.o. (P<0.05) and 65y.o. and older (P<0.10); however, these estimates were sensitive to alternative model specifications. The study found no evidence of association between drilling and hospitalizations, which is likely due to the use of a binary drilling measure (at least one well vs zero wells). Each drilled well generates pollution, and a binary drilling measure does not capture drilling intensity in places with multiple wells. Our study is able to capture how drilling intensity is associated with AMI. The most recent study on UNGD and cardiovascular hospitalizations found increased odds of hospitalizations for heart failure for most UNGD metrics.32 No study, to our knowledge, has examined cardiovascular mortality or mortality from any other cause.

Although we do not test specific mechanisms whereby UNGD may be affecting AMI incidence due to data limitations, one hypothesized pathway is the adverse effect of air pollution on cardiovascular health. Air pollution contributes to ischemic heart disease, and AMI in particular.4,5 The unconventional drilling phase involves several air polluting processes, such as emissions from the well and extensive truck traffic required to develop and maintain each unconventional well.33 Research has established linkages between UNGD and decreased air quality in surrounding communities.8,9 A recent study found positive associations between the intensity of oil and gas development and production and several indicators of cardiovascular disease (augmentation index, blood pressure) and inflammatory markers associated with stress and short-term air pollution exposure (IL-1β, TNF-α).18 Directly linking AMI incidence to specific UNGD pollutants is difficult without a prospective study design. Our approach follows the recommendation by the American Heart Association to focus on sources that emit mixtures of pollutants.4 The air pollution pathway, however, is further complicated by the stress that UNGD generates in nearby communities.10,11 UNGD has been associated with increased levels of light and noise pollution as well as other sources of stress, such as health concerns and community change.12,13,33 This multifaceted nature of the potential impact of UNGD on AMI makes an investigation of specific pathways difficult; and future research should address this challenge if possible.

Our findings should guide cardiovascular clinical practice and preventive care. First, general awareness of these potential effects of UNGD exposure on cardiovascular health in exposed communities and among clinicians is necessary. Targeted preventive efforts to limit additional AMI risk factors and a more streamlined system of referrals to specialists may be beneficial in communities with long-term exposure to UNGD. Both clinicians and public health professionals can play a particularly important role in disseminating the information on these potential risks. Although everyone experiencing AMI symptoms should seek immediate care, providers should have a heightened sensitivity for working up symptoms of AMI in middle-aged men and older adults living in areas with extensive UNGD. Associations between UNGD and AMI were most consistent among men aged 45-54y.o. in our study; this is the group most likely to be in the unconventional gas industry workforce and is probably the most exposed to UNGD air pollutants and stressors. While future research could test the hypothesis that male UNGD workers develop cardiovascular disease at higher rates than their non-UNGD worker counterparts, this demographic group should be a particular focus of cardiovascular preventive measures today. Being cognizant of the potential effects of UNGD on the risk of AMI is especially important given that the public’s knowledge about heart disease and its symptoms is limited, especially among men and older populations,34 and delays in seeking care for AMI are notoriously common.35 Further, cardiovascular health in the UNGD-exposed communities, which tend to be rural, may be further compromised by the increasing trends in rural hospital closures in the U.S.36 (the number of hospitals decreased in both NY and PA counties, see Table 1). Since UNGD tends to take place in rural areas and since travel times to a hospital are generally longer in rural communities, people that live in UNGD-exposed areas and suffer from cardiovascular disease may be at increased risk of adverse health outcomes, including death.

Our findings contribute to the body of evidence on adverse health effects of UNGD, lending support to health protective policies. Given the lack of a large body of causal evidence on the effects of UNGD on health at the time, three states – New York, Vermont, and Maryland – and several European countries have taken a precautionary approach and prohibited hydraulic fracturing, until and unless more is known. If causal mechanisms behind our findings are ascertained, our findings would suggest that bans on hydraulic fracturing can be protective for human health.

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

Our study has limitations to consider. First, the ecological design does not allow to capture individual exposure to UNGD. We are limited by data availability: hospitalization and mortality data do not have residential addresses, preventing us from calculating more precise, individual-level exposure metrics (e.g. number of wells within a radius). Another limitation is that we cannot rule out residual confounding. However, we minimized confounding to the best of our ability, by examining a natural experiment, specifying a model with a rich set of controls and fixed effects, and conducting several sensitivity analyses. Given the inability to differentiate specific types of AMI (ST-elevation MI or non-ST-elevation MI) with the use of ICD codes in our study period, we are also unable to comment specifically on these types of AMI. Further, our findings may not generalize to other UNGD contexts. Finally, as mentioned above, we are not able to ascertain by which specific mechanisms UNGD may be affecting cardiovascular health. However, our study is an important first step in evaluating associations between UNGD exposure and AMI. Future research studies could focus on identifying specific mechanisms behind the relationship between UNGD and AMI.

Our study has considerable strengths. This is the first study, to our knowledge, that uses the exogenous variation in energy policy between New York and Pennsylvania in a natural experiment to examine health effects. The two regions overlay the Marcellus Shale and have UNGD potential; New York’s ban is likely the strongest determinant of where unconventional wells are drilled. The natural experiment design allows us to counter selection bias. Our model specification also allows to account for both observable and unobservable time-invariant county characteristics (county fixed effects), time trends in the outcome (year-quarter fixed effects), and state-specific time trends (year-by-state interactions). Another significant strength is our use of continuous drilling metrics. The only other study linking UNGD to AMI hospitalizations used a binary drilling metric,31 which fails to capture associations of drilling intensity with health, and six Pennsylvania counties had over five hundred wells in 2014, reflecting enormous exposure. Last but not least, this is the first study evaluating the relationship between UNGD and mortality from any cause. This study is an important first step in the construction of a strong evidence base to inform decisions on environmental health policy.

5. Conclusions

In this observational study leveraging a natural experiment, we found statistically significant positive associations of cumulative UNGD with increased AMI hospitalization rates among middle-aged men and older men and women as well as with increased AMI mortality among middle-aged men. Although specific mechanisms are not yet ascertained, efforts should be made to increase awareness, scale up preventative programs to reduce AMI risk factors, and encourage timely care seeking for cardiovascular concerns in exposed communities.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

Long-term exposure to unconventional gas development increases heart attacks.

Heart attack hospitalizations increase 1.4-2.8%, depending on age and sex.

Heart attack mortality increases 5.4% in middle-aged men.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are thankful to Richard DiSalvo, PhD (Princeton University) for help with constructing the hospitalization database for Pennsylvania and Andrew Boslett, PhD (University of Rochester) for help with obtaining coal production data. They also thank the Pennsylvania Health Care Cost Containment Council (PHC4) for their support in obtaining access to the inpatient discharge records. PHC4 is an independent state agency responsible for addressing the problem of escalating health costs, ensuring the quality of health care, and increasing access to health care for all citizens regardless of ability to pay. PHC4 has provided data to this entity to further PHC4’s mission of educating the public and containing healthcare costs in Pennsylvania. PHC4, its agents, and staff have made no representation, guarantee, or warranty, express, or implied that the data - financial, patient, payor, and physician specific information - provided to this entity are error-free or that the use of the data will avoid differences of opinion or interpretation. This analysis was not prepared by PHC4. This analysis was done by Dr. Hill and her collaborators. PHC4, its agents, and staff bear no responsibility or liability for the results of the analysis, which are solely the opinion of this entity.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH): DP5OD021338 (AD, LL, ELH; PI: Hill), F31ES029801 (PI: Willis), TL1TR002371 (MDW; PI: Morris/Fryer), and P30 ES01247 (DC). The research presented in this paper is that of the authors and does not reflect the official policy of the NIH.

Footnotes

Part of this work was presented at AcademyHealth 2018 Annual Research Meeting, June 24-26, 2018 in Seattle, WA and the authors are grateful for the comments received there.

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

This project was reviewed by University of Rochester’s Institutional Review Board and found to be exempt as not human subjects research (#STUDY00000600).

We have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Excluded counties are Erie, Livingston, Ontario and Yates in New York and Allegheny, Armstrong, Beaver, Butler, Fayette, Pike, Washington and Westmoreland in Pennsylvania.

Excluded counties are Cayuga, Erie, Livingston, Oneida, Onondaga, Ontario and Yates in New York and Schuylkill and Snyder in Pennsylvania.

Excluded Pennsylvania counties are Allegheny, Armstrong, Beaver, Butler, Fayette, Washington, Westmoreland, Greene, Indiana, Cambria, Blair, Somerset and Bedford.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Roth GA, Johnson C, Abajobir A, et al. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases for 10 Causes, 1990 to 2015. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(1):1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.04.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ôunpuu S, et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. The Lancet. 2004;364(9438):937–952. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17018-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steptoe A, Kivimäki M. Stress and cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2012;9(6):360–370. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2012.45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brook Robert D, Sanjay Rajagopalan, Arden Pope C., et al. Particulate Matter Air Pollution and Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation. 2010;121(21):2331–2378. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181dbece1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newby DE, Mannucci PM, Tell GS, et al. Expert position paper on air pollution and cardiovascular disease. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(2):83–93. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brook RD, Franklin B, Cascio W, et al. Air Pollution and Cardiovascular Disease: A Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the Expert Panel on Population and Prevention Science of the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2004;109(21):2655–2671. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000128587.30041.C8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pope CA, Burnett RT, Thurston GD, et al. Cardiovascular Mortality and Long-Term Exposure to Particulate Air Pollution: Epidemiological Evidence of General Pathophysiological Pathways of Disease. Circulation. 2004;109(1):71–77. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000108927.80044.7F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.HEI - Energy Research Committee. Potential Human Health Effects Associated with Unconventional Oil and Gas Development: A Systematic Review of the Epidemiology Literature. Health Effects Institute; 2019. Accessed July 26, 2020. https://hei-energy.org/system/files/hei-energy-epi-lit-review.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 9.Czolowski Eliza D, Santoro Renee L, Tanja Srebotnjak, Shonkoff Seth BC Toward Consistent Methodology to Quantify Populations in Proximity to Oil and Gas Development: A National Spatial Analysis and Review. Environ Health Perspect. 125(8):086004. doi: 10.1289/EHP1535; PMCID: PMC5783652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher MP, Mayer A, Vollet K, Hill EL, Haynes EN. Psychosocial implications of unconventional natural gas development: Quality of life in Ohio’s Guernsey and Noble Counties. J Environ Psychol. 2018;55:90–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2017.12.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Casey JA, Wilcox HC, Hirsch AG, Pollak J, Schwartz BS. Associations of unconventional natural gas development with depression symptoms and disordered sleep in Pennsylvania. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):11375. doi:http://dx.doi.org.ezp.lib.rochester.edu/10.1038/s41598-018-29747-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blair BD, Brindley S, Dinkeloo E, McKenzie LM, Adgate JL. Residential noise from nearby oil and gas well construction and drilling. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. Published online May 11, 2018:1. doi: 10.1038/s41370-018-0039-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Radtke C, Autenrieth DA, Lipsey T, Brazile WJ. Noise characterization of oil and gas operations. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2017;14(8):659–667. doi: 10.1080/15459624.2017.1316386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hill EL. Shale gas development and infant health: Evidence from Pennsylvania. J Health Econ. 2018;61:134–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2018.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Willis MD, Jusko TA, Halterman JS, Hill EL. Unconventional natural gas development and pediatric asthma hospitalizations in Pennsylvania. Environ Res. 2018;166:402–408. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2018.06.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Denham A, Willis M, Zavez A, Hill E. Unconventional natural gas development and hospitalizations: evidence from Pennsylvania, United States, 2003–2014. Public Health. 2019;168:17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2018.11.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deziel NC, Brokovich E, Grotto I, et al. Unconventional oil and gas development and health outcomes: A scoping review of the epidemiological research. Environ Res. 2020;182:109124. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McKenzie LM, Crooks J, Peel JL, et al. Relationships between indicators of cardiovascular disease and intensity of oil and natural gas activity in Northeastern Colorado. Environ Res. 2019;170:56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2018.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maps of Fracking Support and Bans and Moratoria in New York State. FracTracker Alliance. Accessed January 30, 2021. https://www.fractracker.org/map/us/newyork/moratoria/ [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dokshin FA. Whose Backyard and What’s at Issue? Spatial and Ideological Dynamics of Local Opposition to Fracking in New York State, 2010 to 2013. Am Sociol Rev. 2016;81(5):921–948. doi: 10.1177/0003122416663929 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dodge J, Lee J. Framing Dynamics and Political Gridlock: The Curious Case of Hydraulic Fracturing in New York. J Environ Policy Plan. 2015;19(1):14–34. doi: 10.1080/1523908X.2015.1116378 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hall JC, Shultz C, Stephenson EF. The political economy of local fracking bans. J Econ Finance. 2018;42(2):397–408. doi: 10.1007/s12197-017-9420-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benjamin Emelia J, Blaha Michael J, Chiuve Stephanie E, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2017 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135(10):e146–e603. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Whitacre JV, Slyder JB. Carnegie Museum of Natural History Pennsylvania Unconventional Natural Gas Wells Geodatabase (v.2005-2014). Pittsburgh, PA: Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Published 2014. https://maps.carnegiemnh.org/index.php/projects/unconventional-wells/ [Google Scholar]

- 25.Data Downloads. Area Health Resources Files. Accessed January 30, 2021. https://data.hrsa.gov/data/download [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pennsylvania Department of Health. Oil and Natural Gas Production (ONGP) Health Concerns.

- 27.Ford ES, Ajani UA, Croft JB, et al. Explaining the Decrease in U.S. Deaths from Coronary Disease, 1980–2000. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(23):2388–2398. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa053935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma J, Ward EM, Siegel RL, Jemal A. Temporal Trends in Mortality in the United States, 1969-2013. JAMA. 2015;314(16):1731. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.12319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sidney S, Quesenberry CP, Jaffe MG, et al. Recent Trends in Cardiovascular Mortality in the United States and Public Health Goals. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1(5):594. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.1326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jemielita T, Gerton GL, Neidell M, et al. Unconventional Gas and Oil Drilling Is Associated with Increased Hospital Utilization Rates. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(7):e0131093. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peng L, Meyerhoefer C, Chou S-Y. The health implications of unconventional natural gas development in Pennsylvania. Health Econ. Published online March 13, 2018. doi: 10.1002/hec.3649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McAlexander TP, Bandeen-Roche K, Buckley JP, et al. Unconventional Natural Gas Development and Hospitalization for Heart Failure in Pennsylvania. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(24):2862–2874. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.10.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adgate JL, Goldstein BD, McKenzie LM. Potential Public Health Hazards, Exposures and Health Effects from Unconventional Natural Gas Development. Environ Sci Technol. 2014;48(15):8307–8320. doi: 10.1021/es404621d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dracup K Acute Coronary Syndrome: What Do Patients Know? Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(10):1049. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.10.1049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moser DK, Kimble LP, Alberts MJ, et al. Reducing delay in seeking treatment by patients with acute coronary syndrome and stroke: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council on cardiovascular nursing and stroke council. Circulation. 2006;114(2):168–182. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.176040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaufman BG, Thomas SR, Randolph RK, et al. The Rising Rate of Rural Hospital Closures. J Rural Health Off J Am Rural Health Assoc Natl Rural Health Care Assoc. 2016;32(1):35–43. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.