Abstract

Objectives

The degree of training and variability in the clinical brain death examination performed by physicians is not known.

Methods

Surveys were distributed to physicians (including physicians-in-training) practicing at 3 separate academic medical centers. Data, including level of practice, training received in completion of a brain death examination, examination components performed, and use of confirmatory tests were collected. Data were evaluated for accuracy in the brain death examination, self-perceived competence in the examination, and indications for confirmatory tests.

Results

Of 225 total respondents, 68 reported completing brain death examinations in practice. Most physicians who complete a brain death examination reported they had received training in how to complete the examination (76.1%). Seventeen respondents (25%) reported doing a brain death examination that is consistent with the current practice guideline. As a part of their brain death assessment, 10.3% of physicians did not report completing an apnea test. Of clinicians who obtain confirmatory tests on an as-needed basis, 28.3% do so if a patient breathes during an apnea test, a clinical finding that is not consistent with brain death.

Conclusions

There is substantial variability in how physicians approach the adult brain death examination, but our survey also identified lack of training in nearly 1 in 4 academic physicians. A formal training course in the principles and proper technique of the brain death examination by physicians with expert knowledge of this clinical assessment is recommended.

Formal brain death determination guidelines in an adult were initially published by the American Academy of Neurology in 1995,1 and were most recently updated in 2010.2 Despite a practical guideline being in place for more than 20 years, there remains substantial variability among institutional requirements for a brain death pronouncement in an adult,3 and the degree of formal training in completion of the examination is unknown.

The brain death examination was designed as a clinical assessment of brain function, and ancillary tests were not considered mandatory by the authors of the formal guideline1 but, rather, were intended to be an adjunct to a clinical brain death assessment if certain components of the examination could not be performed reliably. Despite this, in many countries, ancillary testing is required to pronounce a patient brain dead,3 and 6.5% of surveyed hospital policies in the United States required ancillary tests.4 Other hospital-specific policies in the United States specified instances in which ancillary tests were necessary, and included situations whereby the patient would not have met clinical criteria for brain death (e.g., ongoing presence of confounders, imaging did not explain the comatose state), and therefore physicians should not have proceeded with a brain death evaluation at all.4 This reported variability in the development of institution-specific policies that contradict the formal brain death guideline further complicate this diagnosis and may predispose clinicians to rely on imperfect ancillary tests as opposed to the clinical examination, potentially resulting in an incorrect determination of brain death.

Surveys of physicians on their understanding of the principles of brain death determination are nonexistent. In this project, we aimed to determine the rate of formal brain death training that physicians have received, the specific examination components each physician completes, reasons for ordering ancillary tests, and the preferred study when ancillary tests are considered necessary.

Methods

Physicians from 3 academic, tertiary care hospitals (Institution A, Institution B, and Institution C) were invited via e-mail to participate in this study.

An electronic survey was developed using REDCap, an online assessment tool and data repository. Data were collected and stored on the University of Kansas Medical Center site.

Potential participants were identified by sending an introductory e-mail with the common survey link to all individual department/division chairs and administrative assistants for distribution via their department e-mail listserv to all attending physicians, fellows, residents, and interns. Participants were asked if they performed brain death examinations on adults in clinical practice and what neurologic examination components they assessed as part of the brain death examination. In addition, the use of ancillary tests, rationale for when a test was ordered, and the preferred ancillary test was also solicited. Specific information requested via this survey is listed in the table.

Table.

Survey tool

Participants were excluded if they reported that they did not perform an adult brain death examination as a part of their clinical practice, regardless of their reported specialty. For responses provided in ranges (e.g., apnea test duration of 8–10 minutes), the shortest time indicated was used for data analysis.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

Informed consent was waived because accessing the survey was considered implied consent. The institutional review boards at each institution approved this study.

Statistical analysis

The frequency of specific answers to the survey questions are described by percentages with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The magnitudes of differences in responses between subgroups taking the survey are described by risk differences with 95% CIs. Statistical analysis was completed using Microsoft Excel, 2016 version (Microsoft, Redmond, WA).

Data availability

Anonymized data will be shared on request from any qualified investigator.

Results

The survey was distributed to a total of 42 department or division chairs across 3 study sites, with respondents from 23 different departments/divisions responding, for an overall response rate of 54.8%. The specific number of survey recipients is unknown because the authors were unable to directly distribute the surveys to individuals.

Of 225 total surveys returned, 68 respondents (30.2%) reported that they complete brain death examinations in clinical practice and were included in the final data analysis. Attending physicians represented the majority of the responses (61.8%), followed by residents (29.4%), fellows (7.4%), and interns (1.5%). The distribution of medical specialties represented is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1. Specialty distribution of survey respondents.

In total, 16 respondents (23.9%) reported no training in performance of a brain death examination (95% CI 15.3–35.3). For those who did receive training, this occurred most often during residency (66.7%) or fellowship (19.6%).

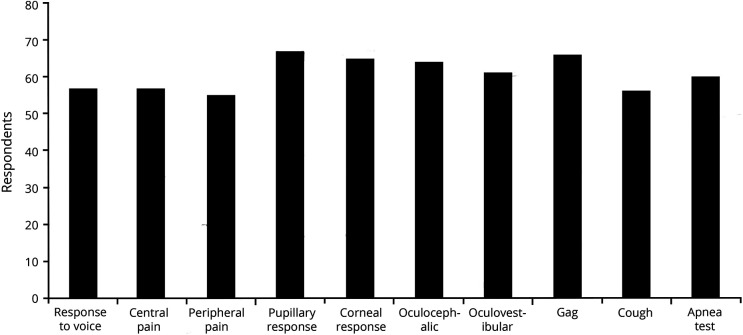

Figure 2 lists the frequencies physicians reported performing each component of the standard brain death examination, as outlined in the current American Academy of Neurology guideline.2 In addition, 2 examination components were listed on the survey but are not included in the standard brain death examination. For these examination findings, 26.5% of physicians reported checking peripheral reflexes (patellar, etc.) and 23.5% reported evaluation of the plantar response/Babinski sign during a brain death examination.

Figure 2. Frequency of completion of brain death examination components.

While the majority of respondents indicate they perform an apnea test as a part of a brain death assessment, 10.4% (7 of 67 respondents to this question, 95% CI 5.2–20.0) do not. Forty-seven physicians reported the duration of their apnea test, which averaged 10.09 minutes (range 2–60 minutes).

Fifty-eight physicians (85.3%) stated they felt competent when completing a brain death examination. Based on specialty, neurology and neurosurgery physicians rated themselves as competent 92.3% of the time as compared to 62.5% of non–neurology/neurosurgery responders (risk difference 29.8%, 95% CI 8.1–54.1). As a surrogate marker of competence, the rate of apnea test performance between neurology/neurosurgery physicians and non–neurology/neurosurgery physicians was evaluated. Neurology-based specialties performed an apnea test 86.3% of the time, while nonneurology specialties reported completing an apnea test 100% of the time (risk difference −13.7%, 95% CI −25.7 to 6.8).

Of physicians who perform brain death examinations in practice, 20 (30.3%) order ancillary testing as a part of their standard evaluation. Respondents were allowed to mark multiple reasons for ordering ancillary testing, and 10 reported it was required by their hospital policy, 10 reported it made them more comfortable with the diagnosis, 3 indicated it was done to protect them from liability, and 3 indicated other reasons (persistent metabolic abnormalities, family request, and “other individual situations”).

Forty-six physicians indicated they do not routinely order ancillary testing. Of these, 36 order testing when the clinical examination cannot be fully completed, 33 when they are uncertain of the diagnosis, 13 if the patient breathes during an apnea test, and 14 order additional testing because of family request. Six physicians listed other indications for ancillary testing, with the majority reporting an inability to perform an apnea test as the reason, and one physician using ancillary testing when there were persistent medication effects. The distribution of preferred ancillary tests is listed in figure 3. Respondents were allowed to select multiple options on this question as well.

Figure 3. Selection of ancillary tests.

CTA = CT angiography; MRA = magnetic resonance angiography; TCD = transcranial Doppler.

In total, 17 (25%) of the 68 respondents reported completing all the components of a brain death examination, including an 8- to 10-minute apnea test and excluding unnecessary examination components, as prescribed in the current American Academy of Neurology practice guideline.

When the apnea test duration was not considered, 20 physicians performed all recommended components of the brain death examination, while 15 others performed an appropriate examination, but included peripheral reflexes and/or plantar responses. Despite these more lenient requirements in considering a brain death examination to be correct, 33 physicians (48.5%) still did not perform a guideline-based examination.

In evaluation of responses made only by attending physicians, 13 (31.0%) completed an appropriate examination (apnea test duration not included in this analysis), 10 (23.8%) completed an appropriate examination but also evaluated peripheral reflexes and/or plantar responses, and 19 (45.2%) completed an incorrect examination.

Discussion

Few technical skills are as consequential as performing a completely reliable brain death examination. Our motivation was to perform a survey to evaluate whether more physician training in brain determination is necessary. Yet, our results demonstrate that there is substantial variability in how physicians approach this examination. The results of this survey should not be interpreted as a reflection of practice, which would require direct observation of performance.

In addition to omitting portions of the standardized assessment, multiple physicians also evaluated peripheral or spinal reflexes, which do not assess brain function, and likely only serve to confuse the examiner and family members who may witness an elicited movement due to a spinally mediated reflex in an otherwise brain dead patient. Of note, the presence of triple flexion to a painful stimulus, a spinally mediated reflex, may be present in a brain dead patient; however, any evidence of coordinated and typical decorticate or decerebrate (flexor or extensor) posturing implies brainstem function, and is not consistent with brain death.

While three-quarters of physicians reported receiving training in completion of a brain death examination and more than 85% self-reported competence in the examination, only one-quarter reported completing the examination correctly, according to the current practice guideline.2 Even when using more lenient criteria to consider an examination correct (the duration of an apnea test not being considered, as long as an apnea test was completed), only 29% of physicians were correct, and when permitting the evaluation of unnecessary examination components, this number rose to 51.5%. When physicians-in-training were omitted, attending physicians performed a correct examination 31.0% and 54.8% of the time, when using the less stringent criteria (did not consider apnea test duration and allowed for testing of unnecessary components).

The performance of an apnea test is the most technical and time-intensive portion of the brain death examination, but it is an indispensable requirement for a clinical brain death determination except in case of parenchymal lung disease, which makes the test unsafe. The carbon dioxide challenge through both CSF acidosis and hypercarbia places the ultimate stress on medullary chemoreceptors, and absence of respiratory effort during a proficiently conducted apnea test conclusively proves loss of lower brainstem function. Omission of this component of the examination is consistent with an incorrect determination of brain death.

With the high frequency of incorrectly performed examinations at academic medical centers, the likelihood of inaccurate and incomplete training for medical students, residents, and fellows is substantial, potentially propagating an improper examination technique.

Ancillary testing is considered a tool used to allow brain death determination when the clinical examination cannot be reliably completed or an apnea test cannot be safely performed.2 Within our cohort of respondents, one-third of physicians reported obtaining ancillary testing automatically, regardless of clinical examination findings. This behavior may result in situations whereby a clinical examination is consistent with brain death, but the ancillary test is inconclusive or falsely positive. Multiple physicians reported obtaining an ancillary test because it is a requirement based on their hospital policy. The policies at all surveyed sites were reviewed and none require automatic ancillary testing as a part of the brain death assessment in an adult, indicating unfamiliarity with local policies by some of the participating physicians.

In addition, 28.3% of physicians who obtain ancillary testing on an as-needed basis indicated they order the test if a patient breathes during the apnea test. By definition, a spontaneously breathing patient is not brain dead, and confirmatory tests should not be considered in this situation. The overuse of ancillary testing may predispose clinicians to underestimate the importance of the clinical examination and rely excessively on imperfect radiographic or electrophysiologic tests. Use of these tests, especially EEG, which is susceptible to substantial artifacts in the intensive care unit, increases the risk of a falsely positive result that may serve as a source of confusion when attempting to determine brain death.

A potential confounder in our results is the uncertainty regarding the overall level of experience with the brain death examination among the respondents. With a sizable minority of physicians-in-training in our cohort, it is likely that the average experience is generally low. Because our attending physician respondents performed only marginally better than the trainees, the authors speculate that overall experience among them is also limited, though the results may also simply reflect improper understanding of the concept of a brain death examination. Irrespective of experience level, the underlying theme is that physicians who indicate they perform brain death examinations in clinical practice may be performing the examination incorrectly, at least based on their responses to the survey. This is not fully unexpected based on prior reports of physicians observed in simulation centers, which may also be an effective means of formal education in this examination.5–7

Our survey-based study had several limitations. In order to distribute our e-mail, we were dependent on individual department chairs/division heads and department administrators to forward the information to the physician members of their department. Based on the demographics of our respondents, this occurred variably, though all neurology and neurosurgery departments at each site did respond, thus explaining the overrepresentation of physicians from these 2 specialties among our respondents. A low response rate impaired our ability to fully evaluate the current clinical practice across our study sites. It is possible that respondents did not interpret the phrase “central pain” as the authors intended on our survey—our intended meaning was assessment of supraorbital and mandibular joint pressure—and therefore answered this portion of the survey according to their own interpretation. There is the possibility that respondents misread components of the survey and inaccurately answered the questions as a result. We were also slightly limited in our data analysis by the fact that not all physicians answered every question included in the survey. Finally, we have no way of confirming whether the respondents who reported completing brain death examinations in their clinical practice actually do so unsupervised. This is a relevant caveat because at one of the 3 participating centers, all brain death examinations are conducted or supervised by a staff neurointensivist.

Our results indicate that physicians across multiple academic medical centers often fail to complete a guideline-based adult brain death examination, despite a self-perceived competence in performing the examination. This may potentially lead to inappropriate brain death determinations and improper teaching to physicians-in-training. We acknowledge that a guideline is not a mandate but should be considered best practice. The authors strongly recommend formal training in the completion of the brain death examination by experienced physicians with intimate knowledge of the nuances of the clinical brain death examination, and suggest use of a standardized checklist when completing the examination to prevent inadvertent omission of examination components. In addition, a simulation-based formal certification process overseen by a national or international group may be necessary to ensure proper technique and use of ancillary testing during brain death pronouncements.

Glossary

- CI

confidence interval

Appendix. Authors

Footnotes

Editorial, page 401

Study funding

Funding support for use and maintenance of the REDCap Server is provided by CTSA award UL1TR000001 at the University of Kansas.

Disclosure

The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Practice parameters for determining brain death in adults (summary statement): the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 1995;45:1012–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wijdicks EF, Varelas PN, Gronseth GS, Greer DM; American Academy of Neurology. Evidence-based guideline update: determining brain death in adults: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2010;74:1911–1918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wahlster S, Wijdicks EF, Patel PV, et al. Brain death declaration: practices and perceptions worldwide. Neurology 2015;84:1870–1879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greer DM, Wang HH, Robinson JD, Varelas PN, Henderson GV, Wijdicks EF. Variability of brain death policies in the United States. JAMA Neurol 2016;73:213–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braksick SA, Kashani K, Hocker S. Neurology education for critical care fellows using high-fidelity simulation. Neurocrit Care 2017;26:96–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hocker S, Schumacher D, Mandrekar J, Wijdicks EF. Testing confounders in brain death determination: a new simulation model. Neurocrit Care 2015;23:401–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacDougall BJ, Robinson JD, Kappus L, Sudikoff SN, Greer DM. Simulation-based training in brain death determination. Neurocrit Care 2014;21:383–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data will be shared on request from any qualified investigator.