Abstract

Objective:

To identify unmet basic needs (BN) amongst women referred to colposcopy, to assess patient acceptability/satisfaction with assistance from a navigator to address unmet BN, and to estimate adherence to colposcopy.

Methods:

Women were recruited between 9/2017–1/2019 from two academic colposcopy centers, one serving a rural and one an urban area. BN were assessed by phone prior to colposcopy appointments and considered unmet if unlikely to resolve in one month. Colposcopy adherence pre- and post-study implementation were abstracted over 4–6 months from administrative records. After a lead-in phase of 25 patients at each site, a BN-navigator was offered to new participants with ≥1 unmet BN(s). Primary outcome was adherence to initial appointment.

Results:

Among 100 women, 59% had ≥1 unmet BN, with similar prevalence between urban vs. rural sites. Adherence to initial colposcopy was 83% overall, 72% at the rural clinic and 94% at the urban clinic (p=0.006). These adherence rates were improved from four months prior to study launch [30/59 (51%) rural clinic; and 68/137 (50%) urban clinic]. Although acceptability of BN navigation was >96% and women felt it helped them get to their colposcopy visit, having a navigator was not associated with adherence. Women reporting no unmet BN had the lowest adherence compared to women with ≥1 unmet BN regardless of navigator assistance (p=0.03).

Conclusions:

Disadvantaged women who need colposcopy have unmet BN and value navigator assistance for initial appointments. However, when appointment scheduling includes telephone reminders and inquiring about BN, a navigator may not add value.

Keywords: unmet basic needs, colposcopy adherence, cervical cancer prevention

Précis

Low-income women who need colposcopy may have unmet basic needs and value navigator assistance prior to their colposcopy visit.

INTRODUCTION

Cervical cancer screening is a necessary but insufficient initial step in current cancer prevention schemes, as downstream interventions including colposcopy and treatment of identified pre-cancers must also occur. This multistep process increases the risk for loss to follow-up. Approximately 3.5 million abnormal cervical screening results per year require medical follow-up, most commonly colposcopy; however, adherence rates are suboptimal, ranging from 37 to 77%.1–4 Women who fail to comply with colposcopy referral are at risk for preventable cervical cancer. An estimated 13,800 new cervical cancer cases and 4,290 deaths are expected to occur in the United States in 2020.5 These cases are especially prevalent among disadvantaged women and those in rural areas, where women have lower cervical cancer screening rates, more advanced stages at presentation, and higher cervical cancer mortality rates than women living in urban areas.6–12 Thus, disadvantaged urban women and rural women referred for colposcopy offer a unique target population for interventions aimed to reduce cancer disparities and improve outcomes in underserved areas by improving rates of colposcopy adherence.

Prior studies aimed at increasing colposcopy adherence have tested a diverse range of tools and resources focusing on patient education and counseling, patient reminder systems, and financial incentives including transportation vouchers.13 Lack of time, money or childcare are known barriers to cancer screening follow-up,13–15 and health navigators reduce these barriers to care by helping patients schedule appointments and arrange childcare or transportation.16 However, unmet basic needs (BN) extend far beyond just childcare and transportation. They also may include food, housing, safety, employment and ability to pay for utilities. Consequently, long- term health care needs, especially cancer prevention strategies, are often perceived as secondary to these immediate survival priorities.

The prevalence of unmet BN has not been explored among women who have been referred to colposcopy after abnormal cervical screening. Therefore, we implemented an outpatient program to identify unmet BN among both rural and low-income urban women in an effort to reduce barriers to colposcopy attendance. In addition to describing unmet BN, we aimed to assess the acceptability of BN assessment and the perceived effectiveness of a navigator in assisting women scheduled for colposcopy. Our primary outcome was to compare adherence to first colposcopy appointment among those who were exposed or not to a BN navigator who assisted patients by phone and connected them with community resources.

METHODS

The Institutional Review Boards at Washington University School of Medicine (WUSM) in St. Louis and Southern Illinois University School of Medicine (SIUM) approved this study under protocol# 201708116 and 17–105, respectively. This trial was registered in ClinicalTrials.gov (#NCT03317470).

Study design

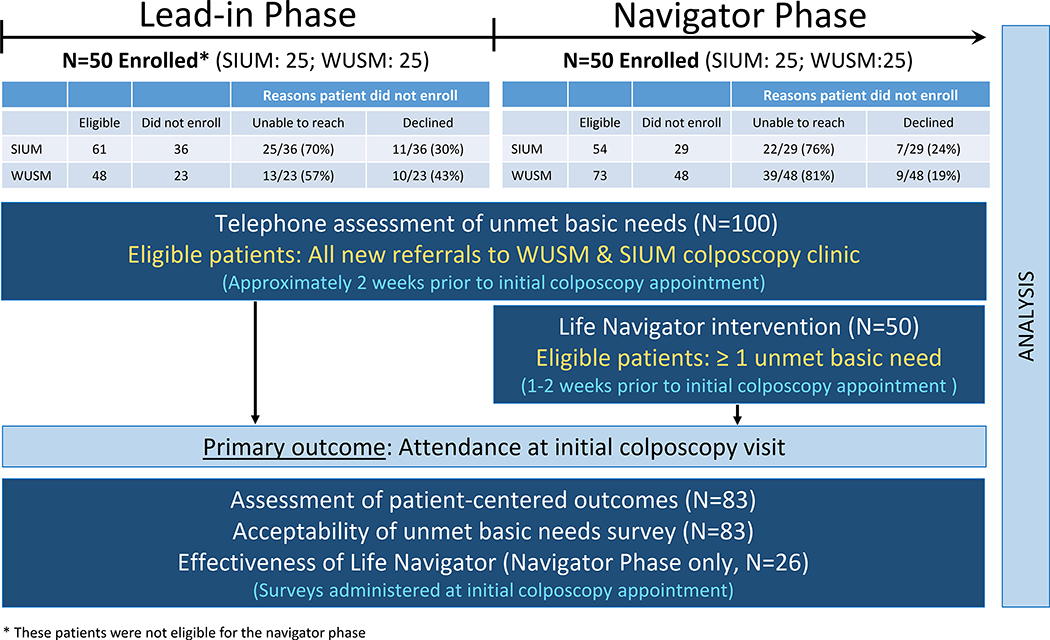

Schema of the study design is shown in Figure 1. This was a pilot, multicenter prospective cohort study conducted at SIUM and WUSM colposcopy clinics from September 2017 to January 2019. Prior to implementation of the study protocol, standardized clinic procedures were implemented for patient appointment reminders. All new patients referred for colposcopy received a telephone reminder of their appointment approximately two weeks in advance. During a patient telephone reminder call a trained research coordinator used a script to ask eligible patients for verbal consent to participate in our study. The script was uniquely tailored for each phase of the study.

Figure 1. Study design and patient flow diagram.

* These patients were not eligible for the navigator phase

SIUM: Southern Illinois University School of Medicine; WUSM: Washington University School of Medicine

The study was designed to have a lead-in phase (n=50 patients; 25 at each site) to allow for standardization of study procedures to gather prospective baseline data regarding colposcopy adherence, and to collect data regarding patients’ unmet BN to enhance preparedness of the BN navigator (licensed social worker, DB). Eligible patients were telephone screened with an 11-item, validated questionnaire about their BN (Supplemental Table 1). If a patient screened positive specifically for the question regarding personal safety, she was immediately offered referral to a 2–1-1 helpline to minimize her personal harm. United Way 2–1-1 is a federally designated dialing code available 24 hours a day to connect callers to local health and social services for assistance with BN. In the U.S., 2–1-1 coverage extends to 94% of the population, including 100% of those in the WUSM catchment area and slightly over 20% in the SIUM region. Following the lead-in period, we enrolled 50 additional patients, 25 at each site, and after completing the 11-item BN assessment, any patients who screened positive for ≥ 1 unmet BN was offered assistance by a BN navigator.

Study sites

Colposcopy clinics at SIUM and WUSM both serve predominantly low-income patients who are uninsured or insured by Medicaid and are staffed by their respective obstetric and gynecology residents and overseen by a department faculty member. WUSM serves a low-income urban population, while SIUM serves a low-income rural population. Consistent with published results, adherence to first colposcopy visit was suboptimal at both sites: during the four months preceding study launch, colposcopy adherence was similarly low at SIUM (30/59, 51%) and WUSM (68/137, 50%).

Study population

Eligible patients included all women newly referred to colposcopy clinics at SIUM and WUSM, who were 18 years or older, English-speaking and able to provide verbal consent. Abnormal cervical cancer screening results were confirmed by review of reports in the patient’s electronic health record. Women were excluded if they were established patients at either colposcopy clinic, had a known diagnosis of cancer; were pregnant, incarcerated, or unable to consent, or did not have access to a working contact phone number. Patients who reported no unmet BN were not offered the BN navigator intervention, but they were still asked to complete a follow-up survey at their colposcopy visit regarding acceptability of the BN survey, within a month of their initial phone call.

Basic needs navigator intervention

The goal of the patient navigator was to help women address their unmet BN prior to their scheduled colposcopy appointments. All interactions between the navigator and the patients were by telephone. We have previously demonstrated the ability to recruit, train, and retain highly skilled and motivated navigators for cancer prevention and control.17 The BN navigator for this study, DB, was a certified social worker who had extensive training and provided similar navigation services to hundreds of low-income smokers in a cessation trial.18 The BN navigator had the following objectives: (1) identify and assess women’s needs; (2) jointly generate solutions to address the needs; (3) develop plans to carry out the solutions; (4) help prioritize among multiple needs; (5) identify community resources that could help meet needs; (6) determine eligibility for services; (7) facilitate access to available resources through appointment scheduling and reminders; (8) prepare women to interact with service agencies and/or serve as an advocate on their behalf; (9) provide instrumental support such as arranging transportation; (10) actively intervene to resolve barriers to BN solutions; (11) oversee follow-up of problem solving actions; and (12) review progress made towards resolving unmet BN and adapt solutions accordingly. The number and frequency of calls was limited only by participants’ needs, interest and willingness to interact.

Measures

Sociodemographic characteristics were solicited from each study participant at the time of consent. The primary outcome for the current analysis was adherence to initial colposcopy appointment.

Unmet basic needs survey

BN were assessed using a screener developed by the study team and drawing upon Segal’s Personal Empowerment scale19 and items developed by Blazer et al.20,21 The questionnaire assessed participants’ perceived likelihood that their safety, housing, food, and financial needs would be met in the next month. Five questions beginning with: “How likely is it that…” included a) “…someone will threaten to hurt you physically in the next month?” b) “…you will have a place to stay all of next month”, c) “…you and others in your home will get enough to eat in the next month”; d) “…you will have enough money in the next month for necessities like food, shelter and clothing?”; e) “…you will have enough money in the next month to deal with unexpected expenses?” Answer choices for each of these five questions included: very likely, likely, unlikely, and very unlikely. Needs were considered unmet if reported as unlikely or very unlikely for items b-e, or likely or very likely for item a. The BN assessment also included a self-assessment of the safety of their neighborhood (very safe, safe, unsafe, very unsafe) and the amount of space in their home given the number of people living there (more than enough, about the right amount, not enough living space). For these specific questions, living in an “unsafe” or “very unsafe” neighborhood and/or reporting “not enough living space” were also considered an unmet BN. Prevalence of each type of unmet BN was reported using descriptive statistics.

Patient acceptability of basic needs survey and self-perception of effectiveness of the BN navigator

Patients who arrived to colposcopy appointments were asked during their clinic visit to complete a five item self-administered survey about their experiences discussing BN. Specific questions included: “Do you think it is okay to ask patients about their basic needs?”; “Was it hard for you to talk about your BN?”; “Did any of the questions hurt your feelings?”; “When you were answering these questions, how did it make you feel?”; and “Did you have trouble answering any of the questions about basic needs?”. We also asked seven questions assessing their perception of the effectiveness of the BN navigator: “Was the patient navigator helpful to you?”; “What could the navigator have done better?”; “Did you use any of the resources that the patient navigator told you about?”; “Would you recommend a patient navigator to a family member or friend?”; “Do you think the patient navigator helped you so that you could get to your clinic appointment”; “If available, would you find it helpful to talk to the patient navigator more?”.

Recognizing the time patients dedicated to answering both the BN survey by phone and the follow-up survey at their appointment (estimated total time of 15 minutes), we provided all study participants who arrived to their appointment with a $5 gift card to a local convenience or grocery store. Given that our primary outcome was adherence to initial colposcopy visit, in order to minimize participation bias, we did not disclose this incentive during the consent process or any time before colposcopy adherence was measured.

Statistics

The clinical and demographic characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics. Continuous and categorical variables between groups were compared by a Kruskal-Wallis test and the Chi-square test or Fisher’s Exact test, respectively. Both Chi-square test and Cochran-Armitage Trend Test were used to test the difference across three time points: pre-study, during-study, and post-study. All statistical tests were two-sided using an α = 0.05 level of significance. SAS Version 9.4 (Cary, NC) was used to perform all statistical analyses.

Role of the Funding Source

This study was supported, in part, by a grant (P20CA192987) from the National Cancer Institute. Additional funding was provided by SIUM, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology. During the study period, Dr. Lindsay Kuroki received grant support as a KL2 career scholar from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Number KL2TR002346. The contents in this manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NCATS or NIH.

RESULTS

The mean age of the 100 women who completed the telephone BN survey was 37.7 years. 59% had at least one unmet BN with no differences between study sites in the median number of unmet BN (1, interquartile range 0–3 at WUSM, 0, range 0–2 at SIUM, p = 0.15). Table 1 lists the type and prevalence of unmet BN among our surveyed low-income women who needed colposcopy. There were no differences in the types of unmet BN based on whether women received navigator assistance (Supplemental Table 1).

Table 1.

Patients’ unmet basic needs assessed at time of telephone reminder for initial colposcopy visit

| Characteristic | Total N=100 |

|---|---|

| # of unmet basic need(s)a | 1 (0–2) |

| Type of unmet basic need | |

| Unexpected expenses | 51 |

| Utilities | 19 |

| Transportation | 17 |

| Food, shelter, clothing | 16 |

| Neighborhood safety | 11 |

| Food security | 5 |

| Personal safety | 4 |

| Childcare | 4 |

| Housing | 3 |

Data is presented as median (interquartile range).

Adherence to initial colposcopy appointment was 83% overall, 72% at SIUM and 94% at WUSM (p=0.006) (Table 2). These adherence rates were improved from those identified four months prior to study launch [30/59 (51%) for SIUM and 68/137 (50%) at WUSM]. After study closure, this rate was initially sustained at SIUM for six months; however, both sites eventually fell back to its approximate baseline adherence rates (Table 2). Analysis by Chi-square test comparing pre- vs. during- vs. post-study adherence rates were statistically significant at both sites; WUSM p<0.0001 and SIUM p=0.02. Analysis by Cochran-Armitage Trend Test over these same time points confirmed a significant increasing rate in colposcopy adherence at SIUM (p=0.02).

Table 2.

Patient adherence to initial colposcopy visit by study phase and site (N=100)

| Adherence rates | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-study | During study | Post-study | ||

| Study site | January-April 2017 | Lead-in Phase (no navigator) | Navigator Intervention | February-July 2019 |

| WUSM*** | 68/137 (50%) | 23/25 (92%) | 24/25 (96%) | 57/115 (50%) |

| SIUM* | 30/59 (51%) | 17/25 (68%) | 19/25 (76%) | 41/57 (72%) |

| Total | 98/196 (50%) | 83/100 (83%) | 98/172 (57%) | |

WUSM: Washington University School of Medicine, SIUM: Southern Illinois University School of Medicine

Analysis was performed by Chi-square test across three different time points for each study site: pre-study vs. during study vs. post-study.

p<0.05

p<0.001

We also analyzed adherence to initial colposcopy appointment stratified by unmet BN and navigator assistance (Table 3). Adherence rates were 71% (29/41) among women who reported no unmet BN, 91% (30/33) among women with ≥1 unmet BN with no navigator assignment, and 92% (24/26) among women who received navigator assistance for their ≥1 unmet BN (p=0.03). However, when women were grouped according to exposure to navigator assistance (navigator vs. no navigator) regardless of basic needs, there was no significant difference in colposcopy adherence.

Table 3.

Patient adherence to initial colposcopy visit by unmet basic needs and navigator assistance (N=100)

| Characteristic | Total N=100 | No navigator No unmet basic need N=41 | No navigator ≥1 unmet basic need N=33 | Navigator ≥1 unmet basic need N=26 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial colposcopy visit* | ||||

| Arrived* | 83 (83) | 29 (71) | 30 (91) | 24 (92) |

| Did not arrive | 17 (17) | 12 (29) | 3 (9) | 2 (8) |

| Adherence to follow-up recommendations* | ||||

| Yes | 31 (35) | 12 (39) | 12 (38) | 7 (27) |

| No | 28 (31) | 9 (29) | 15 (47) | 4 (15) |

| Not applicable | 30 (34) | 10 (32) | 5 (16) | 15 (58) |

Analysis was performed by Chi-square test across the three different study groups. The denominator for the percentages is the sum of patients by column, across all categories, excluding missing values.

Percentages are listed in parentheses and may not total 100% due to rounding

p<0.05

Demographics and unmet BN of patients who arrived to colposcopy visit and their acceptability of the BN questionnaire are presented in Table 4. Compared to women who arrived to their initial colposcopy appointment at WUSM, those who attended SIUM colposcopy clinic were respectively younger, more likely to be Caucasian, self-reportedly had more lifetime sexual partners (median 10 vs. 5), and had shorter intervals between colposcopy and their abnormal cervical cancer screen (31 vs. 44 months). Other demographic and medical characteristics did not differ by site (Table 4).

Table 4.

Demographics and unmet needs of patients who arrived to colposcopy visit and their acceptability of the basic needs questionnaire (N=83)

| Academic colposcopy referral center | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Total N=83 | Missing N | WUSM N=47 | SIUM N=36 |

| Age (years) | 38 ±10 | 0 | 39±12 | 36 ±9 |

| Race** | ||||

| White | 42 | 0 | 17 (36) | 25 (69) |

| Black | 40 | 29 (62) | 11 (31) | |

| Other/mixed | 1 | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Lifetime number of abnormal cervical cytology | 1 (1,2) | 2 | 1 (1,2) | 2 (1,2) |

| Gravidity | 3 (1, 4) | 0 | 3 (1,4) | 3 (2,4) |

| Number of lifetime sexual partners* | 6 (5,12) | 18 | 5 (4,9) | 10 (6,20) |

| Age at first intercourse | 16 ±2 | 23 | 16 ±2 | 16±3 |

| Received HPV vaccine | 2 | |||

| Yes | 13 (16) | 4 (9) | 9 (26) | |

| No | 59 (73) | 35 (76) | 24 (69) | |

| Unknown | 9 (11) | 7 (15) | 2 (6) | |

| HIV | 3 (4) | 8 | 3 (7) | 0 (0) |

| Current smoker | 32 (43) | 8 | 16 (39) | 16 (47) |

| Method of contraception | 0 | |||

| None | 28 (33) | 15 (32) | 13 (36) | |

| Long-acting reversible | 21 (26) | 13 (28) | 8 (22) | |

| Pill, patch, ring, condoms | 9 (11) | 7 (15) | 2 (6) | |

| Permanent sterilization | 23 (27) | 10 (21) | 13 (36) | |

| Mixed | 2 (2) | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | |

| High-grade cervical cytologya | 16 (19) | 0 | 10 (21) | 6 (17) |

| Time to colposcopy visit (days)* | 39 (29,66) | 0 | 44 (31,86) | 31 (23,47) |

| Number of unmet basic need(s) | 1 (0,2) | 0 | 1 (0,3) | 1 (0,2) |

| Unmet basic need(s) present | 50 (60) | 0 | 30 (64) | 20 (56) |

| Unexpected expenses | 46 (55) | 0 | 28 (60) | 18 (50) |

| Utilities | 17 (20) | 0 | 9 (19) | 8 (22) |

| Transportation | 15 (18) | 0 | 10 (21) | 5 (14) |

| Food, shelter, clothing | 13 (16) | 0 | 8 (17) | 5 (14) |

| Neighborhood safety | 9 (11) | 0 | 5 (11) | 4 (11) |

| Food security | 4 (5) | 0 | 3 (6) | 1 (3) |

| Personal safety | 4 (5) | 0 | 4 (9) | 0 (0) |

| Housing | 3 (4) | 0 | 1 (2) | 2 (6) |

| It is okay to ask a patient to talk about their basic needs | 80 (96) | 3 | 44 (100) | 36 (100) |

| It was hard to talk about my basic needs | 6 (8) | 3 | 5 (11) | 1 (3) |

| The questions hurt my feelings | 1 (1) | 3 | 1 (2) | 0 (0) |

| When answering the questions, I felt…b | ||||

| Fine, it did not bother me* | 60 (72) | 0 | 29 (62) | 31 (86) |

| Relieved | 23 (28) | 0 | 15 (32) | 8 (22) |

| Nervous | 5 (6) | 0 | 3 (6) | 2 (6) |

| Overwhelmed | 3 (4) | 0 | 3 (6) | 0 (0) |

| Sad | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Worried | 4 (5) | 0 | 2 (4) | 2 (6) |

| I had trouble answering questions about basic needs | 4 (5) | 4 | 3 (7) | 1 (3) |

WUSM: Washington University School of Medicine serves a low-income urban population; SIUM: Southern Illinois University School of Medicine serves a low-income rural population; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; HPV: human papillomavirus

The denominator for the percentages is the sum of patients by column, across all categories, excluding missing values. Percentages might not total 100% due to rounding. Data are mean ± standard deviation, median (Interquartile range), or n (%) by column.

High-grade cervical cytology included high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL), atypical squamous cells cannot exclude HSIL, and atypical glandular cells (AGC)

Not mutually exclusive

p<0.05

p<0.01

Among the 83 woman who attended their clinic visit, nearly all agreed that it was acceptable to discuss their unmet BN. When asked about how they felt when taking the survey, they were allowed to mark more than one answer and the majority responded they felt fine and/or relieved. Six percent disclosed that they had trouble answering questions about their BN. Nevertheless, 70% reported the navigator helped them so they could attend their colposcopy appointment (Table 5). The overwhelming majority said the navigator was helpful and they would recommend this service to a family member or friend. In fact 90% said it would be helpful to talk to the navigator more even though only 48% reported using the resource(s) that were recommended (Table 5).

Table 5.

Patient perception of usefulness of the basic needs navigator among those who had ≥1 unmet need (N=26)

| Survey question/response | Missing data | N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| The navigator helped me so that I could get to my clinic appointment | 6 | 14 (70) |

| The patient navigator was helpful | 4 | 21 (95) |

| What could the navigator have done better? | 0 | |

| Listen more to my needs | 0 (0) | |

| Have more knowledge about resources to help me | 2 (8) | |

| Have more patience | 0 (0) | |

| Called me at more convenient times | 3 (12) | |

| I used the resource(s) that the navigator told me about | 3 | 11 (48) |

| I would recommend this kind of helper to a family member or friend | 3 | 22 (96) |

| There were parts I didn’t like or didn’t find helpful | 4 | 0 (0) |

| It would be helpful to talk to the navigator more | 6 | 18 (90) |

DISCUSSION

Women referred for colposcopy after abnormal cervical screening results often have unmet BN. A simple intervention of a tailored phone call reminding patients of their appointment and assessing their unmet BN significantly improved colposcopy adherence by 60%, from 50% to 80% over the first five months of our study. After this lead-in phase, when we introduced a patient navigator to assist with unmet BN, colposcopy adherence plateaued at 86% over a 9-month period. Navigator assistance with unmet BN was acceptable and welcomed by women who needed colposcopy, but did not result in measurable further improvement in colposcopy adherence. Our results further demonstrated that women reporting no unmet BN had the lowest adherence compared to women with ≥1 unmet BN regardless of navigator assistance. Further dissemination and implementation research is warranted to leverage 2–1-1 to test whether referral to this BN helpline may improve colposcopy adherence, especially in low-resource settings that lack patient navigators.

We were unable to identify prior U.S. investigations specifically assessing unmet BN (Medline search for “colposcopy” and “basic needs”) or for incorporating 2–1-1 referral into efforts to improve colposcopy adherence (Medline search for “colposcopy” and “2–1-1”). Although patient navigation and BN navigation may appear to have some broad overlap, our study elevates the body of literature dedicated to social determinants of health and calls to action provider awareness of the impact unmet BN has on cervical cancer prevention strategies. Our findings pose the question whether there exists a ceiling effect phenomenon—perhaps individualized patient reminders of their appointment, assessments of needed resources and offers of help are the most effective components of any patient navigation and beyond that, additional elements may not contribute to improving adherence to colposcopy. Luckett and colleagues showed that implementation of a patient navigator program improved colposcopy adherence from 50% to 70%.22 Percac-Lima and associates targeted Latina women in Massachusetts with patient navigators and found that colposcopy adherence improved from 80% to 84% while also rising among women who did not receive navigators.23 However, assistance with unmet BN may not be sufficient to overcome all barriers to colposcopy adherence for high-risk women, as in this study also found that fear, information gaps, and concern about pain were common barriers to colposcopy in their Latina population.24 Despite our study exclusion of non-English speaking patients, given the increased risk of cervical cancer faced by Hispanic women,25 it would be imperative to study the effect of our intervention in this at-risk population using Spanish-speaking navigators to screen and assist with unmet BN in this population.

Our study had several limitations. Its small sample size may have precluded identification of meaningful improvements in adherence from the provision of navigators. Given that the focus of our research is to improve adherence to colposcopy, we acknowledge the inherent selection bias of those patients who were enrolled. Among eligible patients who did not enroll, many could not be reached via phone due to non-working number, no answer, or a full voice mailbox. Furthermore, given the two study sites are referral-based colposcopy centers, we were unable to perform any report/analysis comparing outcomes among patients who enrolled vs. those who declined enrollment. Unless patients attended their visit, clinical and demographic information could not be validated. Selection bias may have also impacted our secondary outcome of patient acceptability of the navigator. This was only assessed among women who attended their colposcopy appointment; it is possible that the women who did not attend their visit found navigators unacceptable, though our high adherence rate minimizes this bias. Although 2–1-1 provides referrals to local support agencies, many agencies lack the resources and capacity to help all who need it.26,27

Completing telephone contacts with women awaiting colposcopy can be difficult and is often automated. Nursing and social work staff often lack time for interviewing, counseling and referring women who have yet to attend a clinic assessment. Training staff in the execution of scripted interviews and referrals at the time of appointment reminder calls may be difficult, as front-desk staff may lack medical sophistication needed to address patient questions about cervical cancer risk and procedure steps. Yet, patients’ experiences with front desk staff is a strong predictor of positive patient-reported outcomes.28 Larger studies will be needed to validate our results and to identify efficient strategies for assessing and addressing unmet BN. Whether further assistance or patient navigation improves adherence to indicated treatment remains to be explored.

CONCLUSION

Disadvantaged women who need colposcopy often have unmet BN and value navigator assistance for initial appointments. The execution of our study at two clinics serving urban and rural populations show that executing a BN navigation program is feasible. Clinicians in cervical cancer prevention programs should assess the extent of unmet BN among their patients, explore innovative strategies for addressing these needs, and report their results.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Dr. Lindsay Kuroki is a KL2 scholar whose research is supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Number KL2TR002346. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

SUPPORT: This study was supported, in part, by a grant (P20CA192987) from the National Cancer Institute. Additional funding was provided by SIUM, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology. During the study period, Dr. Lindsay Kuroki received grant support as a KL2 career scholar from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Number KL2TR002346.

Abbreviations and acronyms

- BN

Basic needs

- WUSM

Washington University School of Medicine

- SIUM

Southern Illinois University School of Medicine

- HPV

human papillomavirus

- HSIL

high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion

- ASC-H

atypical squamous cells cannot exclude HSIL

- AGC

atypical glandular cells

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT: The authors report no conflict of interest.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

IRB APPROVAL: Obtained on August 29, 2017 by Washington University’s Human Research Protection Office (Institutional Review Board, IRB Project# 201708116) and by the Springfield Committee for Research Involving Human Subjects, Southern Illinois University School of Medicine’s Institutional Review Board (IRB # 17-105)

References

- 1.Block B, Branham RA. Efforts to improve the follow-up of patients with abnormal Papanicolaou test results. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1998;11(1):1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuroki LM, Bergeron LM, Gao F, Thaker PH, Massad LS. See-and-Treat Loop Electrosurgical Excision Procedure for High-Grade Cervical Cytology: Are We Overtreating? J Low Genit Tract Dis 2016;20(3):247–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marcus AC, Kaplan CP, Crane LA, et al. Reducing loss-to-follow-up among women with abnormal Pap smears. Results from a randomized trial testing an intensive follow-up protocol and economic incentives. Med Care 1998;36(3):397–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rojas C, Zhou MK, Khamis HJ, Amesse L. Analysis of patterns of patient compliance after an abnormal Pap smear result: the influence of demographic characteristics on patient compliance. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2013;17(3):298–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(1):7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benard VB, Johnson CJ, Thompson TD, et al. Examining the association between socioeconomic status and potential human papillomavirus-associated cancers. Cancer. 2008;113(10 Suppl):2910–2918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hall HI, Rogers JD, Weir HK, Miller DS, Uhler RJ. Breast and cervical carcinoma mortality among women in the Appalachian region of the U.S., 1976–1996. Cancer. 2000;89(7):1593–1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harris R, Leininger L. Preventive care in rural primary care practice. Cancer. 1993;72(3 Suppl):1113–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Newmann SJ, Garner EO. Social inequities along the cervical cancer continuum: a structured review. Cancer Causes Control. 2005;16(1):63–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rowland D, Lyons B. Triple jeopardy: rural, poor, and uninsured. Health Serv Res. 1989;23(6):975–1004. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh GK. Rural-urban trends and patterns in cervical cancer mortality, incidence, stage, and survival in the United States, 1950–2008. J Community Health. 2012;37(1):217–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yabroff KR, Lawrence WF, King JC, et al. Geographic disparities in cervical cancer mortality: what are the roles of risk factor prevalence, screening, and use of recommended treatment? J Rural Health. 2005;21(2):149–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khanna N, Phillips MD. Adherence to care plan in women with abnormal Papanicolaou smears: a review of barriers and interventions. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2001;14(2):123–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kupets R, Paszat L. Physician and patient factors associated with follow up of high grade dysplasias of the cervix: a population-based study. Gynecol Oncol.120(1):63–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lerman C, Hanjani P, Caputo C, et al. Telephone counseling improves adherence to colposcopy among lower-income minority women. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10(2):330–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paskett ED, Dudley D, Young GS, et al. Impact of Patient Navigation Interventions on Timely Diagnostic Follow Up for Abnormal Cervical Screening. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2016;25(1):15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kreuter MW, Eddens KS, Alcaraz KI, et al. Use of cancer control referrals by 2–1-1 callers: a randomized trial. Am J Prev Med 2012;43(6 Suppl 5):S425–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McQueen A, Roberts C, Garg R, et al. Specialized tobacco quitline and basic needs navigation interventions to increase cessation among low income smokers: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2019;80:40–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Segal SP, Silverman C, Temkin T. Empowerment and self-help agency practice for people with mental disabilities. Soc Work. 1993;38(6):705–712. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blazer DG, Sachs-Ericsson N, Hybels CF. Perception of unmet basic needs as a predictor of depressive symptoms among community-dwelling older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(2):191–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blazer DG, Sachs-Ericsson N, Hybels CF. Perception of unmet basic needs as a predictor of mortality among community-dwelling older adults. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(2):299–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luckett R, Pena N, Vitonis A, Bernstein MR, Feldman S. Effect of patient navigator program on no-show rates at an academic referral colposcopy clinic. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2015;24(7):608–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Percac-Lima S, Benner CS, Lui R, et al. The impact of a culturally tailored patient navigator program on cervical cancer prevention in Latina women. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2013;22(5):426–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Percac-Lima S, Aldrich LS, Gamba GB, Bearse AM, Atlas SJ. Barriers to follow-up of an abnormal Pap smear in Latina women referred for colposcopy. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(11):1198–1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heintzman J, Hatch B, Coronado G, et al. Role of Race/Ethnicity, Language, and Insurance in Use of Cervical Cancer Prevention Services Among Low-Income Hispanic Women, 2009–2013. Prev Chronic Dis 2018;15:E25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boyum S, Kreuter MW, McQueen A, Thompson T, Greer R. Getting help from 2–1-1: A statewide study of referral outcomes. J Soc Serv Res. 2016;42(3):402–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kreuter M, Garg R, Thompson T, et al. Assessing The Capacity Of Local Social Services Agencies To Respond To Referrals From Health Care Providers. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(4):679–688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaphingst KA, Weaver NL, Wray RJ, Brown ML, Buskirk T, Kreuter MW. Effects of patient health literacy, patient engagement and a system-level health literacy attribute on patient-reported outcomes: a representative statewide survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.