Abstract

Under normal conditions, high sodium (Na+) in extracellular (Na+e) and blood (Na+b) compartments and low Na+ in intracellular milieu (Na+i) produce strong transmembrane (ΔNa+mem) and weak transendothelial (ΔNa+end) gradients respectively, and these manifest the cell membrane potential (Vm) as well as blood–brain barrier (BBB) integrity. We developed a sodium (23Na) magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging (MRSI) method using an intravenously-administered paramagnetic polyanionic agent to measure ΔNa+mem and ΔNa+end. In vitro 23Na-MRSI established that the 23Na signal is intensely shifted by the agent compared to other biological factors (e.g., pH and temperature). In vivo 23Na-MRSI showed Na+i remained unshifted and Na+b was more shifted than Na+e, and these together revealed weakened ΔNa+mem and enhanced ΔNa+end in rat gliomas (vs. normal tissue). Compared to normal tissue, RG2 and U87 tumors maintained weakened ΔNa+mem (i.e., depolarized Vm) implying an aggressive state for proliferation, whereas RG2 tumors displayed elevated ∆Na+end suggesting altered BBB integrity. We anticipate that 23Na-MRSI will allow biomedical explorations of perturbed Na+ homeostasis in vivo.

Subject terms: Cancer imaging, Cancer metabolism, Cancer microenvironment, Tumour biomarkers, CNS cancer, Tumour heterogeneity, Blood-brain barrier

Introduction

Sodium (Na+) concentration is normally low intracellularly (~ 10 mM) and high in blood and extracellular spaces (~ 150 mM)1–3, producing a strong transmembrane Na+ gradient (∆Na+mem ≈ 140 mM) and a weak transendothelial Na+ gradient (∆Na+end ≈ 0 mM). The ∆Na+mem is coupled to the cell membrane potential (Vm), nerve signaling1, muscle activity4 and osmoregulation5, while the ∆Na+end impacts bicarbonate and proton transport between extracellular and intravascular compartments2,6–8 to signify blood–brain barrier (BBB) integrity9,10.

The sodium–potassium pump transports Na+ against its electrochemical gradient by consuming adenosine triphosphate generated through oxidative phosphorylation11. In glioblastoma (GBM), glycolysis is upregulated in relation to oxidative phosphorylation even with sufficient oxygen12. Aerobic glycolysis generates excessive amounts of hydrogen ions and lactate, which are extruded into the extracellular milieu, lowering the pH of the tumor microenvironment13. Since both the cell membrane and BBB regulate the ionic composition of the extracellular fluid1,2, we posited that maintaining ∆Na+mem and ∆Na+end becomes unsustainable in the tumor neurovascular unit. Activity of voltage-gated sodium channels on the cancer cell membrane helps regulate proliferation, migration, and invasion rather than excitability14. Similar to pH dysregulation in cancer, electrolyte imbalance also has a role in tumorigenesis15,16. Thus, being able to measure [Na+] across different compartments in vivo could be considered as an important biomarker.

Hyperpolarized Vm corresponds to quiescent cell cycle stages (G0 phase), and depolarized Vm indicates proliferative/replicative stages (M phase)17–19. Therefore, ∆Na+mem is a biomarker for tumorigenicity and tumor aggressiveness. Determining [Na+] in the extracellular milieu usually involves inserting microelectrodes through the skull and reading voltage differences across cellular compartments20. In addition to issues of accurate microelectrode positioning and tissue penetration, such invasive techniques are challenging for human translation.

Angiogenesis is a crucial part of tumor growth21. Unlike normal tissues, the immature tumor vasculature exhibits saccular formations, hyperbranching, and twisted patterns that cause the BBB to be leaky. Prior cancer research avoided measuring [Na+] in blood presumably due to microhemorrhage concerns from ruptured blood vessels with microelectrodes. But given the gamut of anti-angiogenic therapies for GBM22, it is desirable to measure ∆Na+end non-invasively.

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) detects the isotope sodium-23 (23Na), a spin-3/2 quadrupolar nucleus. 23Na is 100% abundant and provides the second-strongest endogenous NMR signal in vivo, next to hydrogen (1H) which is a spin-1/2 non-quadrupolar nucleus23. 23Na magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has greatly impacted stroke and ischemia research24,25, but reflects total sodium (Na+T)26,27 because 23Na-MRI signals from blood (Na+ b), extracellular (Na+ e), and intracellular (Na+ i) compartments are difficult to separate. 23Na-MRI methods based on apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC), inversion recovery, and multiple quantum filtering (MQF) attempt to separate free (i.e., unbound or aqueous) and bound Na+ signals and their volume fractions, but suffer from low sensitivity. Moreover, diffusion methods necessitate large magnetic field gradients due to low gyromagnetic ratio (γNa) and short longitudinal/transverse relaxation times (T1/T2) for 23Na. These 23Na-MRI methods are somewhat limited for probing the aqueous Na+i signal because they cannot fully suppress major contributions from aqueous Na+b and Na+e, both of which dominate the Na+T signal26,28,29. Thus, quantification of transmembrane (ΔNa+mem = Na+e—Na+i) and transendothelial (ΔNa+end = Na+b—Na+e) gradients has been challenging with 23Na-MRI. While detecting Na+T is useful clinically, ∆Na+end and ∆Na+mem may help reveal relevant information about BBB viability and cellular proliferative/oncogenic potential in solid tumors.

Another approach to separate aqueous Na+ signals in vivo involves intravenous administration of an exogenous paramagnetic but polyanionic contrast agent (paraCAn-). The paraCAn- consists of a lanthanide(III) cation core bound to an anionic macrocyclic chelate30,31. Since the paraCAn- extravasates into extracellular space of most organs but does not enter cells, only Na+e and Na+b will be attracted to the paraCAn- and experience a shift in the 23Na resonance frequency (depending on degree of paraCAn- extravasation in each compartment) to separate the 23Na magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging (MRSI) signals between Na+b, Na+e and Na+i. While these paramagnetic effects will also shorten 23Na relaxation times slightly, the peak’s integral remains unaffected if data are acquired under fully relaxed conditions, and the peak’s shift can still be precise when there is marginal line broadening although integral bands will need to be widened so as to accurately estimate concentration. Proof-of-concept for this has been demonstrated in situ for the heart32 and liver33. Given the compromised BBB in tumors relative to healthy tissue, the 23Na-MRSI technique in conjunction with paraCAn- is particularly efficacious in studying brain tumors.

The most effective paraCAn- for aqueous compartmental 23Na separation is34 the thulium(III) cation (Tm3+) complexed with 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetrakis(methylenephosphonate) (DOTP8-) to form TmDOTP5− (Fig. 1a). TmDOTP5− has many applications in animal models, both with 1H-NMR35–38 and 23Na-NMR33,39, demonstrating that these Tm3+ agents are non-toxic at the doses presently being used. Particularly, TmDOTP5− has been infused intravenously to induce 23Na compartmental signal separation in healthy34,40 and tumor-bearing rats41. However, these studies only detected non-localized 23Na signals, and thus could not differentiate between Na+ across tissues. Our goal was to investigate ∆Na+mem and ∆Na+end in brain tumors and normal tissues in 3D using 23Na-MRSI with TmDOTP5- at high spatial resolution.

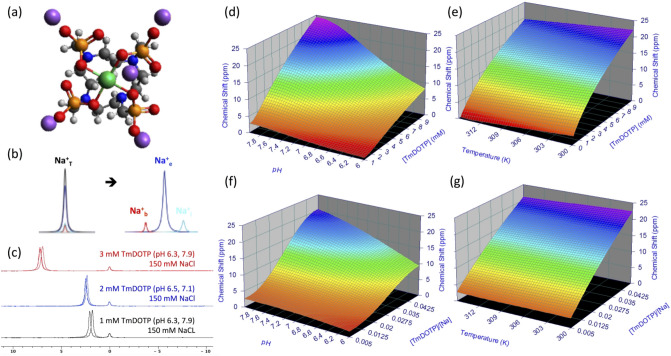

Figure 1.

Shifting mechanism of the 23Na resonance in vitro. (a) Chemical structure of sodium thulium(III) 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetrakis(methylenephosphonate) (Na5TmDOTP). The TmDOTP5− complex consists of the Tm3+ ion chelated with DOTP8−. Each phosphonate-containing pendant arm on TmDOTP5- has electron-donating groups on the oxygen atoms (red) to stabilize the Tm3+ conjugation with DOTP8−. The -5 charge simultaneously attracts five Na+ ions (purple), which experience a shift in the observed 23Na resonance that is dependent on [TmDOTP5−]. (b) In vivo, prior to TmDOTP5− administration (left), the 23Na spectrum yields only a single peak representing the total sodium (Na+T) comprising blood (Na+b), extracellular (Na+e), and intracellular (Na+i ) compartments. Following TmDOTP5− administration (right), the peaks become spectroscopically separable based on [TmDOTP5−] in each compartment. Integrals of these peaks will be representative of aqueous [Na+] in each compartment. (c) A two-compartment coaxial cylinder tube setup was employed for in vitro observation of the chemical shift separation scheme (Figure S1). The inner tube (smaller volume) was filled with 150 mM NaCl, while the outer tube (larger volume) was filled with the same solution in addition to various amounts of TmDOTP5−, each subject to different pH conditions. Thus, all 23Na spectra from this phantom setup displayed a small unshifted peak from the inner compartment and a larger shifted peak. The outer-to-inner volume ratio was 8.6, explaining the difference in sizes of the peaks. Exemplary traces of 23Na spectra show that the shift is much more sensitive to [TmDOTP5−] (2.77 ppm/mM) than to variations in pH (0.25 ppm/pH unit) or temperature (0.03 ppm/°C). The downfield peaks in the red, blue, and/or black spectra are shifted differently due to varying TmDOTP5− concentrations, and these shifts exceed those caused by pH, but all of these shifts are detectable independent of broadening caused by TmDOTP5− (see also Figure S1). Plots (d,e) show that temperature, pH, and [TmDOTP5−] all contribute to variations of the 23Na chemical shift. However, these plots depict ranges of pH and temperature that are unlikely for in vivo settings (i.e., changes over 2 full pH units and temperature changes over 15 °C). Moreover, [Na+] in vivo (~ 150 mM in blood and extracellular space) is extremely high compared to [TmDOTP5−]. Therefore, variations in 23Na chemical shift are primarily dependent on [TmDOTP5−]/[Na+] thereby rendering (f) pH and (g) temperature dependencies negligible. Data points were fit to Chebyshev rational polynomials using TableCurve 3D v4.0.05 (Systat Software, San Jose, CA, USA; https://systatsoftware.com/products/tablecurve-3d/).

In vitro studies established that the 23Na chemical shift is more sensitive to [TmDOTP5−] than other biological factors such as changes in pH (i.e., ~ 0.4 difference between tumor and healthy tissue35 and/or temperature variations (at most ~ 0.5 °C difference across regions36 (Fig. 1b–g); Supplementary: Theory). Upon in vivo administration of TmDOTP5−, three 23Na peaks were observed, corresponding to Na+b, Na+e, and Na+i. The Na+b peak was shifted the most, while the Na+i peak remained unshifted. Our in vivo results, consistent with prior studies of tumor cells in vitro19, demonstrated a significantly weakened ∆Na+mem and strengthened ∆Na+end within tumor tissue relative to healthy tissue as consequences of elevated Na+b and lowered Na+e, respectively. Additionally, the 23Na vascular results showed patterns similar to traditional vascular imaging by 1H-based dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI (1H-DCE-MRI)42. We describe the nuances of these novel measurements of disrupted Na+ homeostasis in cancer and their implications.

Results

In vitro studies for mechanistic separation of 23Na peaks

The goal of these studies was to separate the total Na+ signal (Na+T) into distinct signals for blood (Na+b), extracellular (Na+e), and intracellular (Na+i) pools (Fig. 1b). The shifting mechanism induced by exogenous TmDOTP5− and endogenous biological factors on the 23Na chemical shift in vitro is depicted in Fig. 1c–g. A two-compartment coaxial cylinder NMR tube setup in vitro was used to mimic Na+ in extracellular/intracellular pools (Figure S1). The inner (smaller) and outer (larger) compartments both contained 150 mM NaCl while the latter also contained TmDOTP5- at various concentrations. The whole setup was subjected to several different pH and temperature conditions. The inner compartment, which lacked TmDOTP5− to represent the intracellular space in vivo, produced a small but unshifted 23Na peak at 0 ppm. The larger 23Na peak was shifted downfield by TmDOTP5−, with the difference in peak integrals stemming from different compartment volumes (Figure S1). The feasibility of this approach to quantify Na+ signals from different compartments is demonstrated by switching the contents of the compartments and then repeating the above measurements (Figure S1).

In vitro 23Na spectra revealed that the chemical shift was most sensitive to [TmDOTP5−] changes, compared to pH and temperature variations (Fig. 1c). The 23Na shiftability for TmDOTP5− (=2.77 ppm/mM; Eq. (3) in Supplementary: Theory) was 11.1 × larger than the shiftability for pH (=0.25 ppm/pH unit) and 92.3 × larger than the shiftability for temperature (=0.03 ppm/°C). This means that addition of 1.1 mM TmDOTP5- would induce a ~ 3 ppm shift in the 23Na peak. Conversely, a maximal change of 0.4 in pH units, which is observed between normal and tumor tissues35, would induce only a ~ 0.1 ppm 23Na shift. A similar 23Na shift by temperature would require a 3.3 °C change, which is unlikely in vivo. Based on the pH and temperature ranges observed in vivo (including tumors), the effect from [TmDOTP5-] dominates the 23Na chemical shift (Eq. (2) in Supplementary: Theory) by 95%. Therefore, [TmDOTP5-] is several orders of magnitude more sensitive in shifting the 23Na resonance than typical in vivo factors. Furthermore, the 23Na shiftability arising from [TmDOTP5−] and pH/temperature effects is much larger than T2 broadening from TmDOTP5− (Figs. 1c and S1). Consequently, 23Na spectra displayed dependence mostly on [TmDOTP5−] (Fig. 1d,e). However for in vivo scenarios the ranges shown for pH (2 full pH units) and temperature (15 °C interval) are overestimated, and where [Na+] far exceeds [TmDOTP5-] based on prior experiments37. In blood and extracellular spaces, [Na+] is ~ 30–100 × greater than [TmDOTP5-]36. This suggests that the relative amount of TmDOTP5- (Fig. 1f,g) is the primary factor affecting 23Na chemical shift (Eq. (4) in Supplementary: Theory).

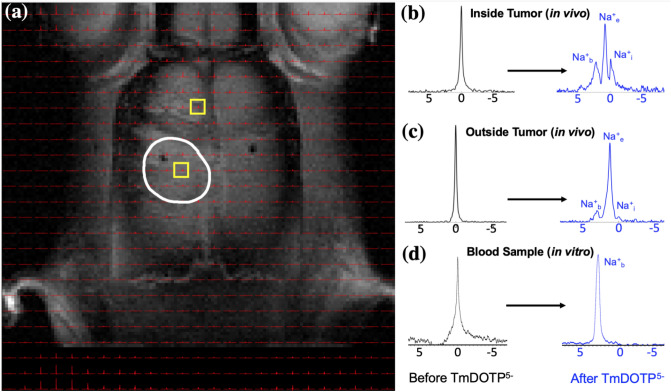

In vivo separation of 23Na peaks indicates compartmentalized Na+ pools

Interrogating individual voxels in the brain before and after TmDOTP5− administration (~ 1 µmol/g body weight (BW)) revealed clear 23Na signal separation, although to varying extents depending on the degree of TmDOTP5- extravasation from blood to the extracellular space. 23Na-MRSI data overlaid on 1H-MRI anatomy of rat brains bearing U251 tumors showed spectra in tumor and healthy tissue voxels (Fig. 2a), with candidate voxels inside (Fig. 2b) and outside (Fig. 2c) the tumor before and after TmDOTP5−. Before TmDOTP5- delivery, there was a single 23Na peak at 0 ppm corresponding to Na+T, observed ubiquitously both inside and outside the tumor. Upon TmDOTP5- delivery, compartmental 23Na peak separation was achieved. Within the tumor, the compromised BBB permitted greater TmDOTP5− extravasation and accumulation in the extracellular space, explicitly yielding three separate 23Na peaks emerging from the original single 23Na resonance. Each peak was associated with a compartment, with Na+i being the unshifted peak (0 ppm) because TmDOTP5− could not enter the intracellular compartment, and other peaks exhibiting [TmDOTP5-]-dependent shifts. In the tumor, the most-shifted peak was Na+b because the blood compartment had the largest [TmDOTP5−], which was corroborated by removing blood samples from the animal and observing the same chemical shift in vitro (Fig. 2d). In the tumor, the intermediate peak in the middle corresponded to the extracellular Na+e resonance (Fig. 2b). The splitting was also evident outside of the tumor (i.e., in healthy tissue) where TmDOTP5- extravasated to a much lesser extent compared to tumor tissue (Fig. 2c). The Na+b peak was still most-shifted, whereas the Na+i and Na+e peaks were less discernible. When there was significant overlap between adjacent peaks, instead of peak integrals we used the peak amplitudes to discriminate signals. The shifted bulk Na+e peak in healthy tissue confirmed that whatever degree of TmDOTP5- extravasation occurred was sufficient to affect the extracellular 23Na signals, albeit less pronounced than tumoral Na+e. The unshifted Na+i resonance was still at 0 ppm, but partially eclipsed by the bulk Na+e peak. These same patterns inside/outside the tumor were observed throughout the brain (see Figure S2 for other voxels in the same rat brain).

Figure 2.

Demonstration of 23Na peak separation in vivo following TmDOTP5− administration into a rat bearing a U251 tumor in the brain. (a) 1H-MRI of an axial slice displaying the anatomical tumor boundary (white outline). The 23Na-MRSI is overlaid on top of the 1H-MRI. Candidate voxels (b) inside and (c) outside the tumor are indicated (yellow boxes). Before TmDOTP5− delivery, a single 23Na peak was observed at 0 ppm, corresponding to total sodium (Na+T), both inside and outside the tumor (black spectra). Following TmDOTP5− delivery, compartmental peak separation was achieved to varying extents throughout the brain (blue spectra). (b) Within the tumor, this separation was most pronounced due to a compromised blood–brain barrier (BBB), which permits substantial accumulation of TmDOTP5− in the extracellular space. (c) Outside of the tumor, such a high degree of extravasation would not be possible, but some shifting is still observed. The TmDOTP5− distribution in the brain warrants labeling the most shifted peak as blood sodium (Na+b), which occurred consistently around 2 ppm. The unshifted peak, which has no access to TmDOTP5−, is intracellular sodium (Na+i). The intermediate peak, therefore, is extracellular sodium (Na+e), which is shifted more inside the tumor than outside in healthy tissue. Similar spectroscopic patterns are observed throughout all voxels in vivo. See Figure S2 for a slice below the present. (d) In vitro analysis of blood samples from the tumor-bearing rat show that the 23Na blood peak occurred around 2 ppm, which coincided with the most-shifted peak we observed in tumor voxels. This confirmed that the most-shifted peak in the observed 23Na spectra after TmDOTP5- comes from blood. All spectra were magnitude-corrected and line-broadened by 10 Hz.

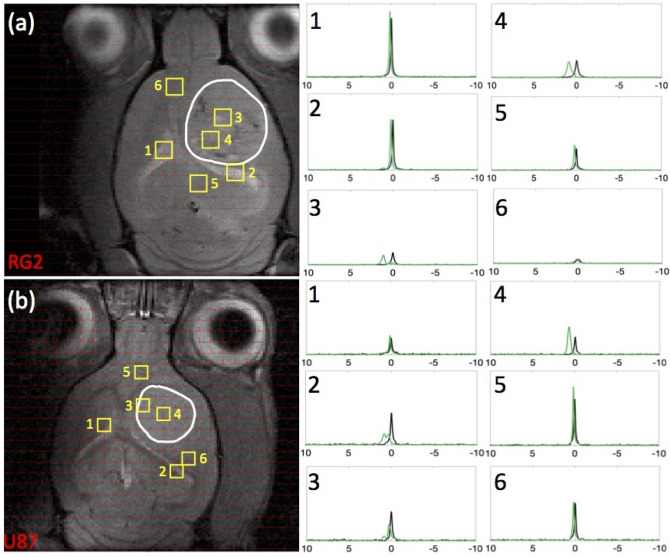

Figure 3 displays data from representative rats bearing (a) RG2 and (b) U87 tumors, with the array of 23Na-MRSI data overlaid on top of the 1H-MRI anatomy. The spectra from individual voxels placed throughout the brain confirmed only one 23Na peak prior to infusion (Fig. 3, black spectra), corresponding to Na+T, but upon TmDOTP5- infusion the single peak separated into two additional 23Na peaks (Fig. 3, green spectra).

Figure 3.

Comparison of 23Na peak separation in rats bearing RG2 and U87 tumors. For rats bearing an (a) RG2 and (b) U87 tumor, the tumor boundary is outlined in white, with voxels of interest indicated in yellow squares (with numbers), and spectra acquired before and after TmDOTP5− delivery shown in black and green, respectively. Tumor voxels 3 and 4 in (a) RG2 and (b) U87 tumor rats exhibited a fair amount of peak separation due to the leaky BBB. Na+b shift was consistently around 2 ppm, and Na+i shift was at 0 ppm, whereas Na+e shift in the tumor was in the range 0.5–1 ppm. Healthy tissue voxels 5 and 6 in (a) RG2 and (b) U87 tumor rats were slightly shifted in the downfield direction, suggesting the paramagnetic effects of TmDOTP5− reach the extracellular space even with limited extravasation. Ventricular voxels 1 and 2 in (a) RG2 and (b) U87 tumor rats displayed a single unshifted Lorentzian peak before and a shifted Lorentzian peak after TmDOTP5− injection. This is attributed to the dominant 23Na signal contribution in the ventricles coming from cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which contains free (i.e., unbound) aqueous Na+. The position of the shifted ventricle peak coincided with the Na+e peak position in other regions of the brain. This agrees with expectation because CSF is in physical contact with the extracellular space with free exchange of aqueous Na+ between the two compartments. Similar spectroscopic patterns are observed throughout all voxels in vivo. See Figure S3 for several slices for each rat shown here. All spectra were magnitude-corrected and line-broadened by 10 Hz.

Prior to TmDOTP5- infusion (Fig. 3, black spectra) ventricular voxels [1 and 2 in Fig. 3a,b] exhibited predominantly Lorentzian lineshapes characterized by a single T2, while those in the normal brain [5 and 6 in Fig. 3a,b] and tumor [3 and 4 in Fig. 3a,b] displayed super-Lorentzian lineshapes indicative of multiple T2 values. This was because the ventricles are comprised almost entirely of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), in which all Na+ ions are in aqueous media, whereas some Na+ ions in tissue can be bound. These observations agreed with prior 23Na-MRI results43–47.

Administration of TmDOTP5− resulted in the emergence of multiple 23Na peaks (Fig. 3, green spectra), particularly within the tumor. However, the downfield shifts seen in healthy tissue suggested the paramagnetic effects of TmDOTP5- were detectable, albeit not as clear as the tumor tissue. We found the most shifted peak sufficiently far from the other two peaks present and attributed it to only Na+b, with an integral () reflecting the blood sodium concentration [Na+]b. Likewise and measured [Na+]e and [Na+]i, respectively. Tumor voxels [3 and 4 in Fig. 3a,b] exhibited spectra where the three peaks were most notably present. Thus, the chemical shifts of the Na+b, Na+e, and Na+i peaks can be respectively placed at the same peak positions. Shifts of this nature were evident throughout the entire depth of the brain for both animals (Figure S3). Ventricular voxels [1 and 2 in Fig. 3a,b)] displayed only one Lorentzian peak shifted to the same extent as Na+e in healthy tissue voxels [5 and 6 in Fig. 3a,b)], albeit in the latter with super-Lorentzian lineshape. These shifts coincided because CSF and the extracellular space are physically in contact with unrestricted exchange of aqueous Na+. Given the shiftability is 2.77 ppm/mM measured in vitro (Fig. 1), the tumor vasculature contained no more than 0.7 mM TmDOTP5− based on the range of shifts observed. Since the blood 23Na signal experienced the greatest shift (Fig. 2d), the (extracellular) tissue therefore encountered even less TmDOTP5-, in agreement with prior observations37.

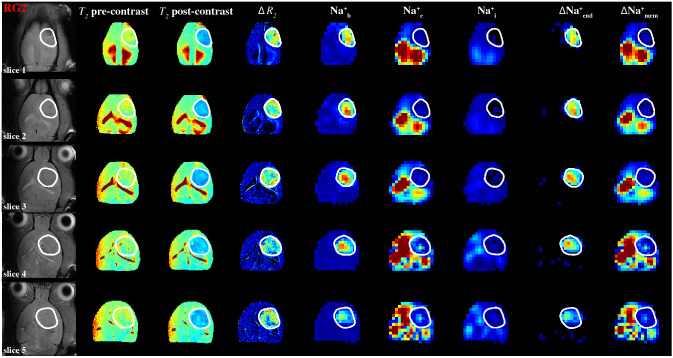

In vivo depiction of transmembrane and transendothelial Na+ gradients

Integration of compartmentalized 23Na spectra (Figs. 2, 3 and S2-S3) generated spatial maps which depicted relative [Na+] in each compartment from which the transmembrane (∆Na+mem = ∫Na+e—∫Na+i) and transendothelial (∆Na+end = ∫Na+b—∫Na+e) gradient maps could also be calculated, as shown in Fig. 4 for multiple axial slices from a rat brain bearing an RG2 tumor. This 3D high-resolution demonstration of the in vivo Na+ biodistribution divulged spatial heterogeneity, where the relative [Na+] of each compartment is a function of the compartment volume and the amount of Na+ in that compartment. It should be noted that TmDOTP5- extravasation under current conditions was sufficient to observe paramagnetic effects even in healthy brain tissue38, and as shown in the T2 maps and concomitant ∆R2 map (given by the difference between inverse T2 maps obtained after and before TmDOTP5- infusion) for RG2 (Fig. 4) and U87 (Figure S4) tumors. While ∆R2 can generally depict the difference between [TmDOTP5-] in healthy and tumor tissues58, it cannot separate [TmDOTP5-] in blood and extracellular compartments within the tumor. Therefore the ∆R2 map cannot fully quantify these separately, while 23Na-MRSI spectra can separate these two signals.

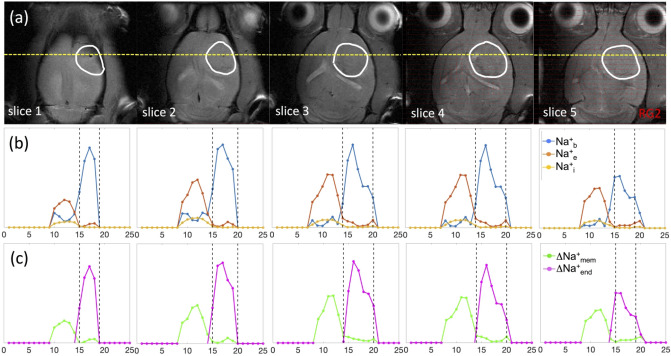

Figure 4.

Spatial distributions of compartmentalized 23Na signals (Na+b, Na+e, Na+i) as well as transendothelial (ΔNa+end) and transmembrane (ΔNa+mem) gradients in an RG2 tumor. The high-resolution 1H-MRI data are shown in the left four columns, whereas the lower resolution 23Na-MRSI data are shown in the next five columns on the right. The left column shows the tumor location (white outline) on the anatomical 1H-MRI (left), whereas the next two columns show the T2 maps (range shown: 0–100 ms) before and after TmDOTP5− injection, and the subsequent column depicts the ∆R2 map (i.e., difference between 1/T2 maps before and after, range shown: 0–30 s−1), which is proportional to [TmDOTP5-] in healthy and tumor tissues. Since ∆R2 values are more heterogeneous within the tumor, the 23Na-MRSI data are needed to separate the blood and extracellular compartment signals for the tumor. Since the integral of each 23Na peak represents the [Na+], the respective three columns show the integral maps of Na+b, Na+e, and Na+i from left to right (i.e., ∫Na+b, ∫Na+e, ∫Na+i). The last two columns on the right show ΔNa+end = ∫Na+b-∫Na+e and ΔNa+mem = ∫Na+e-∫Na+i. The ∫Na+b map reveals low values in healthy tissue compared to tumor tissue, and within the tumor boundary a high degree of heterogeneity. The ∫Na+e map reveals low values in tumor and normal tissues, but within the tumor boundary a small degree of heterogeneity is visible while ventricular voxels show very high values. The ∫Na+i map reveals low values ubiquitously except some ventricular voxels. The ΔNa+end map reveals dramatically high values within the tumor only. The ΔNa+end was driven primarily by an increase of ∫Na+b inside the tumor and which was more pronounced in superficial regions of the brain compared to deeper slices. The ΔNa+mem map shows low values in tumor tissue compared to normal tissue, although ventricular voxels show very high values. The ΔNa+mem is driven primarily by decreased ∫Na+e and thus shows similar level of heterogeneity as the ∫Na+e map. All maps use the same color scale and are relative. See Figure S4 for an example for a U87 tumor.

There was markedly increased ∫Na+b in the tumor, which was not observed elsewhere in normal brain. There was also high degree of heterogeneity within the tumor. The ∫Na+e map revealed the largest values in the ventricles (CSF) and smaller values in the tumor with a slight extent of heterogeneity. Outside the tumor, the bulk peak occurred in the integration band for Na+e. The ∫Na+i map unsurprisingly showed values that were about one order of magnitude lower throughout the brain compared to the ∫Na+b and ∫Na+e maps, since [Na+]i (~ 10 mM) is an order of magnitude smaller than [Na+]b and [Na+]e (~ 150 mM). Furthermore, the ∫Na+i values were not significantly different between the tumor and healthy tissue.

The ∆Na+mem values in the tumor were significantly lower compared to the healthy tissue (p < 0.05) and the map displayed a similar level of heterogeneity as the ∫Na+e map, suggesting that ∆Na+mem is driven primarily by the decrease in Na+e. Ventricular voxels still showed high values in ∆Na+mem, indicating the large magnitude of Na+e in CSF. Likewise, the significant elevation of ∆Na+end in the tumor was driven primarily by the Na+b increase, and ∆Na+end values were significantly larger in the tumor compared to healthy tissue (p < 0.05). This feature was more pronounced in superficial regions of the brain because draining veins run vertically down from cortical surface to white matter and some of these blood vessels are perpendicular to the main static magnetic field, thereby enhancing bulk magnetic susceptibility effect on surrounding tissue, which has been reported in vitro31. This phenomenon is similar to blood oxygenation level-dependent functional MRI contrast mechanisms48–50. For both ∆Na+mem and ∆Na+end gradients, statistical significance was achieved even after excluding ventricle values. These patterns could also be visualized by looking at slice projections of the compartmental and gradient values for the same RG2-bearing animal along a constant coronal position (Fig. 5). For the RG2 tumor, the tumoral increases in Na+b and ∆Na+end were highest superficially (slices 1–4). Conversely, peritumoral values of Na+e and ∆Na+mem increased with depth up to a point in the middle of the brain (slices 3–4) before diminishing. Intratumoral Na+e, however, did not vary significantly with depth. Na+i also decreased inside the tumor but not significantly. The ∆Na+mem and ∆Na+end respectively behaved similarly to Na+b and Na+e since they were the primary drivers of those gradients. Similar observations were made for U87 tumors (Figures S4-S5) regarding Na+ in each compartment and the corresponding gradients.

Figure 5.

Coronal projections of compartmentalized 23Na signals (Na+b, Na+e, Na+i) as well as transendothelial (ΔNa+end) and transmembrane (ΔNa+mem) gradients in an RG2 tumor. (a) Axial 1H-MRI indicating the tumor (white outline) across slices (same as Fig. 4), where the yellow line indicates the position for a coronal projection. (b) Spatially varying 23Na signals for Na+b, Na+e, and Na+i are shown with blue, orange, and yellow lines, respectively, where the vertical black lines indicate the tumor boundary. The Na+b signal (blue) is clearly elevated in the tumor, and most elevated in slices 1–4 (or superficially). Behavior of Na+b signal (blue) is inversely related to Na+e signal (orange), which is high outside the tumor and weaker inside the tumor. While intratumoral Na+b signal (blue) is high in slices 1–4, the peritumoral Na+e signal (orange) is highest in slices 3–4. Comparatively, the Na+i signal (yellow) does not vary significantly across slices, but slightly lower inside the tumor than outside the tumor. (c) Behaviors of ∆Na+mem (green) and ∆Na+end (magenta) signals closely mimic patterns of Na+e and Na+b signals, respectively, indicating that each of those Na+ compartments is the primary driver of the respective Na+ gradient. See Figure S5 for a similar example for a U87 tumor.

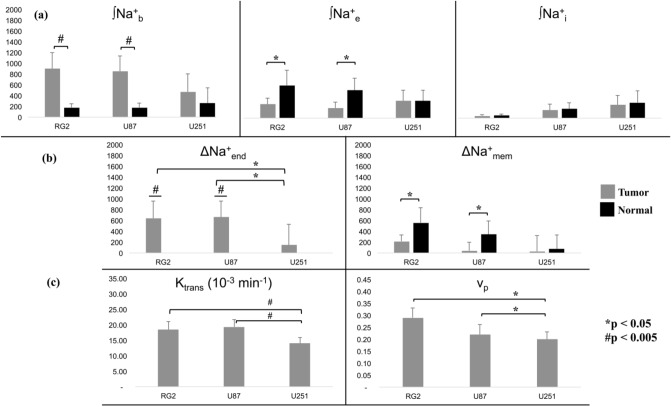

Throughout the entire cohort of rats (Fig. 6a,b), the mean ∫Na+b values were larger and mean ∫Na+e values were lower in the tumor compared to normal tissue. These trends were significant in RG2 (p < 0.005) and U87 (p < 0.05) tumors while there was no significant difference in ∫Na+i for all three tumors (Fig. 6a). Identical trends were also observed in ∆Na+end and ∆Na+mem, and significantly so in RG2 (p < 0.005) and U87 (p < 0.05) tumors. Moreover, ∆Na+end was significantly stronger in RG2 and U87 tumors compared to U251 (p < 0.05) (Fig. 6b).

Figure 6.

Statistical comparisons between intracellular, extracellular, and vascular compartments across RG2, U87, and U251 tumors with 23Na-MRSI and 1H-DCE-MRI. (a) Relation between ∫Na+b, ∫Na+e and ∫Na+i across tumor and healthy tissues. For the RG2 and U87 tumors, the ∫Na+b values were significantly higher than normal tissue (p < 0.005, #). Also for these tumors, the ∫Na+e values were significantly lower than normal tissue (p < 0.05, *). The mean values for the U251 tumor roughly followed the same trend but were not significant. Furthermore, there was no significant difference between ∫Na+i values in tumor and normal tissues for any of the three tumor types. (b) Relations between tumor and normal tissues for ∆Na+end and ∆Na+mem for the three tumor types. Tumor ∆Na+end values were significantly larger than normal values (p < 0.005, #), which were non-positive (data not shown). Moreover, ∆Na+end in RG2 and U87 tumors was significantly greater than in the U251 tumor (p < 0.05, *), indicative of vascular differences between the tumor types. ∆Na+mem values were, on average, weaker in tumor compared to normal tissue, but significant only in RG2 and U87 tumors (p < 0.05, *). Based on Figs. 5 and S5, it is clear that the relation between ∆Na+end and ∆Na+mem is negative. (c) 1H-DCE-MRI data for the volume transfer coefficient (Ktrans) and plasma volume fraction (vp) values, which are known to reveal information regarding vascular structure and function. Ktrans follows the same patterns as ∫Na+b and ∆Na+end across tumor types. Ktrans (p < 0.005, #) and vp (p < 0.05, *) were both significantly larger in RG2 and U87 tumors, compared to U251. See Figure S6 for the plasma flow rate (Fp) and the extracellular volume fraction (ve) 1H-DCE-MRI parameters for each tumor type. See Figure S7 for exemplary maps of 1H-DCE-MRI parameters for individual animals from each tumor type.

Since a strengthened ∆Na+end is indicative of impaired vascular integrity, we employed 1H-DCE-MRI to reliably image vascular function within the tumor core42. Of the four parameters which can be obtained by fitting 1H-DCE-MRI data from a two-compartment exchange model, the volume transfer constant (Ktrans) and plasma volume fraction (vp), as shown in Fig. 6c, both followed the trends of ∆Na+end across tumor types: in RG2 and U87 tumors compared to U251, there was a significant difference (Ktrans: p < 0.005 and vp: p < 0.05; for plasma flow rate (Fp) and extracellular volume fraction (ve) see Figure S6). Although significance was marginal for Fp, the mean values followed suit (Figure S6). The 1H-DCE-MRI data displayed regions of low Fp and larger ve within an exemplary slice of a U251 tumor, indicative of a necrotic core, which RG2 and U87 animals lacked (Figure S7). Reduced ∆Na+end in U251 tumor (Fig. 6b) could be a marker of necrosis presence as evidenced by lower Ktrans and higher vp in the core of U251 tumors. These results suggest that U251 tumors would have lower tissue and blood oxygenation compared to RG2 and U87 tumors. Additionally, beyond the core of U251 tumors ve on average was smaller than vp, indicating a high degree of tumor angiogenesis. These findings further substantiate the ∫Na+b and ∆Na+end results derived from the 23Na-MRSI studies. Given ve and vp heterogeneity, we attribute the minor 23Na peaks downfield of 2 ppm to agent pooling from ineffective agent clearance.

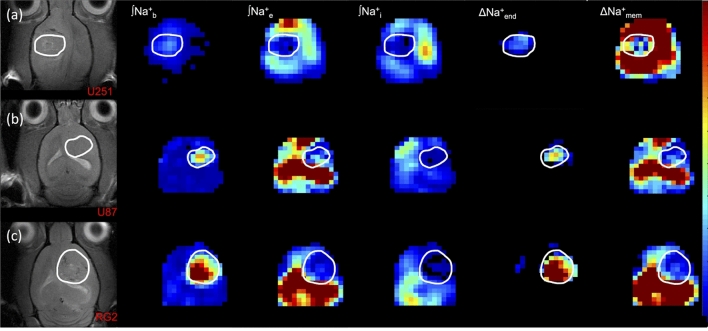

Figure 7 shows ∫Na+b, ∫Na+e, ∫Na+i, ∆Na+end, and ∆Na+mem maps across all tumor cell lines (RG2, U87, U251). The trends seen previously pervaded all animals, but to varying degrees based on the tumor type. The ∫Na+b elevation, and concomitant ∆Na+end strengthening, were most pronounced for the RG2 tumor, followed by U87 and then U251. Likewise, the decrease in ∫Na+e and weakening of ∆Na+mem followed the same order for the tumors. In all tumors, Na+b and Na+e patterns respectively drove the behaviors of ∆Na+end and ∆Na+mem.

Figure 7.

Representative maps of compartmentalized 23Na signals (Na+b, Na+e, Na+i) as well as transendothelial (ΔNa+end) and transmembrane (ΔNa+mem) gradients in U251, U87, and RG2 tumors. The left column shows the tumor location (white outline) on the anatomical 1H-MRI for animals bearing (a) U251, (b) U87 and (c) RG2 tumors. The respective three columns show ∫Na+b, ∫Na+e, and ∫Na+i maps. The last two columns on the right show the ΔNa+end and ΔNa+mem maps. In all tumors the ∫Na+b and ∫Na+e are high and low, respectively, and thus are the main drivers for a high ΔNa+end and a low ΔNa+mem.

Discussion

Implications of current findings

Our results enabled comparisons of Na+ physiology and distributions among RG2, U87, and U251 gliomas. Both U87 and U251 are human-derived cell lines, whereas RG2 is derived from rat glioma51,52. Experimentally the U251 tumor is most heterogeneous, since U251 cells grow erratically and anisotropically compared with RG2 and U87 cells. Additionally the U251 tumor is more invasive and infiltrative than U8753, and U251 cells display greater necrosis, expression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF1α) and of Ki67, indicating higher rates of proliferation54. U251 cells also test positive for glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and vimentin, and exhibit neovascularization and angiogenesis. U87 cells are also positive for vimentin and exhibit significant angiogenesis but do not develop necrosis. Neither U251 nor U87 exhibits endothelial proliferation, a common hallmark of human-derived GBM lines53. The RG2 tumor exhibits invasiveness and induces BBB disruption, producing edema surrounding the tumor where pericytes help promote angiogenesis to increase permeability of the tumor vasculature55. These data concur with our findings. We observed that the negative correlation between the transmembrane and transendothelial gradients were strong in the RG2 and U87 lines but weak for U251. The increase of the transendothelial gradient nearly matched the decrease of the transmembrane gradient in U87 tumors, and exceeded in RG2, which matched behavior regarding BBB permeability. Higher density of blood vessels or higher blood volume would explain higher 23Na signal but not necessarily higher Na+ concentration in the blood. Although the blood vessels are leaky to gadolinium (Gd3+) ions, the elevated transendothelial gradient suggests that the BBB is impermeable to Na+, which is well known2.

Alkylating chemotherapy agents attach an alkyl group to DNA of cancer cells to keep them from replicating. For example, temozolomide (TMZ) achieves cytotoxicity by methylating the O6 position of guanine. O6-methylguanine-DNA-methyltransferase (MGMT) is a DNA repair enzyme, which ordinarily repairs the naturally occurring DNA lesion O6-methylguanine back to guanine and prevents mistakes during DNA replication and transcription. Unfortunately, MGMT can also protect tumor cells by the same process and neutralize the cytotoxic effects of agents like TMZ. If the MGMT gene is silenced by methylation in tumor cells (i.e. MGMT-negative or MGMT-methylated), its DNA repair activity is diminished and the tumor’s sensitivity to chemotherapy is amplified. This suggests that MGMT-positive tumor cells become resistant to chemotherapy, and therefore would possess a depolarized Vm due to its proliferative state.

A recent study demonstrated higher MGMT mRNA expression for RG2 compared to U8756. Another study showed that the 50% inhibition concentration (IC50) of TMZ for U87 and U251 cells are comparable57. Together, these suggest that RG2 is most resistant to chemotherapy presumably due to its augmented proliferative/replicative state, and hence a depolarized Vm. These observations partially agree with our results, where RG2 and U87 tumors maintain a depolarized Vm for their proliferative/replicative state to persist.

Study highlights

In vitro 23Na shifts were most dependent on [TmDOTP5-] given its high shiftability (=2.77 ppm/mM), whereas shiftability due to pH and temperature effects were negligible within physiological ranges (=0.25 ppm/pH unit; =0.03 ppm/°C). The maximum pH difference between glioma and brain tissue is ~ 0.4 pH units35,38,58,59 whereas temperature differences of ~ 0.5 °C are extremely unusual in the brain60–62. Under these extreme conditions, the respective 23Na shift variations caused by pH and temperature would be 0.1 ppm and 0.015 ppm, respectively. Meanwhile, TmDOTP5- can reach in vivo concentrations close to 1–2 mM in blood and interstitial spaces36,37,63 which would cause 23Na shifts of 2.8–5.5 ppm. While we did not attempt to calculate [TmDOTP5-] in each voxel, the sodium shiftability was specifically used to discern that the most shifted peaks were from the blood and extracellular (or CSF) compartments, respectively. Given observed 23Na line widths in vivo on the order of ~ 0.4 ppm, TmDOTP5- concentration effects dominate the shifting effect (96–98%). Therefore, 23Na shiftability can be considered a univariate function of [TmDOTP5-] in vivo.

These observations enabled attributing individual 23Na peaks to specific in vivo pools for blood, extracellular and intracellular spaces arising from compartmental differences in [TmDOTP5-] upon intravenous administration (~ 1 µmol/g). The 23Na shifts in tumor tissue (~ 0.5–1 ppm) were more conspicuous compared to peritumoral tissue, but lower than in blood (~ 2 ppm), suggesting larger [TmDOTP5-] in the blood compartment. Additionally, the blood and extracellular peaks were separated by ~ 1.5 ppm, much larger than their line widths (~ 0.4 ppm), indicating minimal cross-compartmental contributions.

Integrating the separated 23Na peaks enabled spatial mapping of Na+ compartments and gradients in vivo. In the tumor, compared to normal tissue, the transendothelial Na+ gradient was stronger and the transmembrane Na+ gradient was weaker due to elevated blood and decreased extracellular 23Na signals. Current agent concentration does not affect the Na+ gradients, simply the chemical shift position of the 23Na peak for each compartment. However, an order of magnitude higher agent concentration would affect the estimation of the Na+ gradients due to amount of Na+ ions co-infused. The enhanced 23Na blood signals in tumors complied with dynamic 1H-DCE-MRI scans based on Gd3+ uptake, which revealed a higher degree of vascularity in RG2 and U87 tumors. Extracellular Na+ signal in the ventricles was also very high due to the presence of the agent in CSF63. However, ventricular 23Na peaks were Lorentzian because CSF contains primarily aqueous Na+ and thus a single T2 component, whereas tissue 23Na peaks appeared super-Lorentzian because semi-solid Na+ binding in tissue resulted in multiple T2 components64.

Comparison with previous work

The present in vitro data improve upon earlier attempts at quantifying 23Na shiftability using paraCAn- versus many parameters like pH, temperature and other cations65. However, the findings focused more on characterizing the dependence on each parameter (linear, sigmoidal, etc.) rather than considering relevant in vivo conditions. Additionally, the model was not employed in the context of the brain/other tissues. Our 23Na shiftability model does not require assessing the effects of cationic competition for attraction to TmDOTP5-66 because other cations are not present in blood and/or extracellular spaces in concentrations comparable to Na+67.

Prior in vivo 23Na-NMR spectroscopy studies utilizing TmDOTP5- in the brain failed to elucidate spatial information, and instead only focused on acquisition of either global data or localized voxels34,40. The findings reported two broadened peaks, an unshifted intracellular peak and a shifted extracellular peak. Based on two peaks over limited spatial regions, these studies could not comment specifically on the spatial distribution of transmembrane gradient. Furthermore, the blood 23Na signal was not separated so the transendothelial gradient could not be assessed. The shifting capability of TmDOTP5- for separating 23Na resonances in tumor tissue was demonstrated in situ, but still at a global level and without mention of Na+b specifically41,68.

Recently, 23Na-MRI methods have been preferred clinically over spectroscopic methods26. Such relaxometric modalities exploit differences in diffusion and relaxation behavior between Na+ ions inside/outside the cell, because intracellular ions are generally considered less mobile due to binding. Due to the spin-3/2 of 23Na, this binding amplifies the relative contribution of nuclear satellite transitions and permits the use of MQF techniques to isolate signals from individual in vivo compartments. However, these 23Na-MRI methods are currently limited for probing intracellular Na+ because they fail to completely suppress 23Na signals from the blood and extracellular compartments26. While 23Na-MRI results with MQF or ADC can be compared with 23Na-MRSI results, duration of all experimental measurements will require several hours and may put strain on animal’s physiology. However future studies can compare MRSI data with ADC and/or MQF data in different groups.

Our method avoids this practical 23Na-MRI limitation to provide physiological information about all relevant aqueous compartments, and thus enables estimation of transendothelial and transmembrane gradients. Overall, the 23Na-MRSI results agree with prior findings that a depolarized Vm (i.e., weakened transmembrane gradient) is responsible for tumor proliferation19. Given that both the cell membrane and BBB help to maintain the ionic level of the extracellular fluid1,2, our results also show that the transendothelial gradient is significantly enhanced in the same tumors that show compromised BBB integrity (i.e., RG2 and U87). Together these suggest that the current 23Na-MRSI scheme can be used to study the perturbed sodium homeostasis in vivo within the neuropil.

Technical limitations

This technique, while a crucial first step towards mapping the spatial distribution of Na+ in vivo, cannot yet absolutely quantify [Na+], although the ratios of the Na+b, Na+e, and Na+i integrals measured reflect the physiological ratios outside of the tumor, and are altered inside the tumor. Including a quantifiable standard can usually circumvent this limitation because 23Na-NMR has no endogenous species that can be used as a standard. However, using the strong CSF signal in vivo remains a possibility for future explorations. Setups involving Na+ phantoms with relatively large [TmDOTP5-] within the field-of-view (FOV) alongside the body region being imaged could be used, but these could hinder the shim around the subject’s body part being imaged, a technical necessity for the 23Na-MRSI method, and these components are difficult to cover with radio frequency (RF) surface coils. Additionally, broad point-spread functions make quantifications in external phantom standards challenging, though they are perhaps the best option presently69. Moreover, RF inhomogeneity was not directly addressed in this study. To partially circumvent this shortcoming, we used axial slices (parallel to the plane of the RF coil) to a depth of the brain where sufficient sensitivity was achievable. However, this limitation could be overcome with use of adiabatic RF pulses in the future.

Contrast agents with lanthanide(III) ions (Ln3+) are popular in molecular imaging with 1H-MRI13,70, but clinically the preference is probes with Gd3+ conjugated to linear or cyclical chelates71,72. The most biocompatible Gd3+ chelates are based on 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetate (DOTA4-) because they are both kinetically and thermodynamically stable73. A LnDOTA- carries a -1 charge. But if a phosphonate group is attached to each of the pendant arms in DOTA4-, then DOTP8- is formed and complexation with Ln3+ permits a -5 charge (e.g. TmDOTP5-). The majority of paraCAn- that will work for the type of 23Na-MRSI experiments described here are based on Ln3+ complexes, because these give rise to large 1H hyperfine shifts74. But there is growing attention on complexes with similar paramagnetic properties from transition(II) metal ions (Tn2+), such as Fe2+, Ni2+, or Co2+75. The Tn2+-based paraCAn- has the potential for clinical use because of superior biocompatibility. Some Tn2+ complexes designed could carry a -5 charge, but studies need to explore the safest and most effective paraCAn- for 23Na-MRSI experiments.

Another limitation is the infusion of a small amount of Na+ with the paraCAn- itself. TmDOTP5- exists commercially in the form Na5TmDOTP, so a small amount of Na+ is being added. Since [TmDOTP5-] does not exceed 2 mM in the brain vasculature (as determined by the maximum Na+b shift), there is at most ~ 1.3% increase of the endogenous [Na+] in blood/extracellular spaces. In regions with high [TmDOTP5-] and low [Na+], like necrotic core of tumors (e.g., U251 tumors), the infused Na+ may represent a larger percentage. However, necrotic cores can be identified with T2-weighted 1H-MRI scans. Since extracellular Na+ is shifted less than blood, it is highly doubtful that enough Na5TmDOTP extravasation occurs to significantly alter the relative Na+ levels between compartments and impact the conclusions drawn from this study. Future studies with selective BBB opening using focused ultrasound can resolve the uncertainties if intracellular Na+ is lower or higher in tumor compared to normal tissue. Furthermore, we are confident that this additionally infused Na+ does not enter the intracellular compartment and confound the results. Studies indicate that aggressive cancers express embryonic isoforms of voltage-gated sodium channels76–78. Since Vm during the embryonic state is depolarized19, this suggests there is little Na+ influx from the extracellular compartment.

Another confounding factor is the use of isoflurane during both the repeated 1H-MRI tumor monitoring scans, and the 23Na-MRSI imaging session. The use of anesthesia is necessary to reduce movement errors in awake animal MRI/MRSI experiments, but all precautions should be taken to reduce the period of anesthesia exposure. However accuracy of this 23Na-MRSI method is partly dependent on accurate estimation of [TmDOTP5-] per voxel. While T2 maps before and after TmDOTP5- injection can partly estimate [TmDOTP5-] in healthy and tumor tissues, this 1H-MRI approach cannot separate [TmDOTP5-] in blood and extracellular compartments within the tumor. However future spatial resolution improvements of 23Na-MRSI in relation to 1H-MRI could enable this approach to be implemented better for improved estimates of [TmDOTP5-] in blood and extracellular compartments within each voxel.

Conclusion

This study is the first to image the transformed transmembrane and transendothelial gradients of gliomas using TmDOTP5− for 3D 23Na-MRSI at high spatial resolution (1 µL/voxel). The in vivo data consistently revealed weakening transmembrane gradient and strengthening transendothelial gradient within tumors compared to normal tissue, which partially agree with prior findings19 and suggest that tumors experience a redistribution of Na+ across compartments. There is good evidence to propose that these measurements could potentially probe stages of the cell cycle (transmembrane gradient), and perhaps, angiogenic behavior (transendothelial gradient). The described 23Na-MRSI method could empower testing of novel chemotherapy and anti-angiogenic drugs for GBM models, which even at a preclinical level would be significant. This method could potentially be translated into patients by using Tn2+-based or Gd3+-based paraCAn- such that suitable therapies can be targeted based on MGMT screening in GBM patients.

Materials and methods

In vitro characterization

In vitro experiments were performed using a 2-compartment coaxial cylindrical 7-inch NMR tube setup from WilmadLabGlass (Vineland, NJ, USA). One compartment contained 150 mM NaCl and the other contained the same but with varying amounts of TmDOTP5− (1 − 10 mM) and 10% v/v 2H2O to lock the spectrometer frequency using the 2H2O signal (Figure S1). NaCl and 2H2O were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), and TmDOTP5− was purchased as the sodium salt Na5TmDOTP from Macrocyclics (Plano, TX, USA). The 5-mm opening of the NMR tube permitted an insert (the inner compartment) whose 50-mm-long tip had inner and outer diameters of 1.258 and 2.020 mm, respectively. The outer-to-inner volume ratio between the two compartments was 8.6. The geometry of the setup allowed 645 µL total in the outer compartment to fill around the tip. Each solution was pH-adjusted using HCl or NH4OH to give 5 different pH values.

23Na-NMR spectra were collected on a Bruker Avance III HD 500 MHz vertical-bore spectrometer (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA) interfaced with Bruker TopSpin v2.1 software. We used a Bruker 500 MHz TBO liquid broadband probe with z-gradient in all frequencies and an inner coil was used to detect X-nuclei. A single 23Na square pulse (50 µs) was used to globally excite the volume of interest (repetition time TR = 275 ms) collecting 2048 free induction decay (FID) points in the time domain with an acquisition time taq = 38.9 ms, averaged 4096 times. Each set of scans was repeated at a series of temperatures: 27, 30, 34, 37, and 40 °C. Spectra were analyzed using 10 Hz line broadening (for improved delineation of major peaks and reduction of baseline noise) and manual zeroth- and first-order phasing. Data points were fit to Chebyshev rational polynomials using TableCurve 3D v4.0.05 (Systat Software, San Jose, CA, USA).

In vivo studies

The in vivo protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care & Use Committee of Yale University, and all procedures were performed in accordance with these enforced guidelines and regulations, and in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines. Rats (athymic/nude and Fischer 344) were purchased through Yale University vendors. U251, U87 and RG2 GBM cell lines were purchased from American Type Culture Collections (Manassas, VA, USA). The U251, U87, and RG2 cells were cultured and grown in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C in either low-glucose (U251 cells) or high-glucose (U87 and RG2 cells) Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin. Cells for tumor inoculation were harvested upon reaching at least 80% confluence and were prepared in FBS-free DMEM. Athymic/nude rats were injected intracranially with 2 − 5 × 106 tumor cells either from the U251 (n = 6) or the U87 (n = 8) cell line (5-µL aliquot) while placed in a stereotactic holder on a heating pad. Fischer 344 rats were injected with 1.25 × 103 RG2 cells (n = 8). During the procedure, animals were anesthetized via isoflurane (Isothesia) inhalation (3 − 4%), purchased from Covetrus (Portland, ME, USA). Dissection was performed to the cranium, and a hole was drilled into the skull to allow for stereotactic needle insertion. Injections were performed using a 10-µL Hamilton syringe with a 26G needle into the right striatum for majority of the experiments, 3 mm to the right of the bregma and 3 mm below the dura. The cells were injected steadily at 1 µL/min over 5 min and the needle was left in place for an additional 5 min post-injection. The syringe was then gradually removed to preclude any backflow of cells. The hole in the skull was sealed with bone wax, and the incision site was sutured after removal of the syringe. Animals were given bupivacaine (2 mg/kg at incision site) and carprofen (5 mg/kg, subcutaneously) during the tumor inoculation to relieve pain. Carprofen was subsequently given once per day for two days post-inoculation.

Rats were weighed daily and kept on a standard diet of rat chow and water. Tumor growth was monitored every 3–4 days using 1H-MRI under isoflurane anesthesia. When the tumor had reached a minimum mean diameter of 3 mm at 20–24 days post-injection, each animal was imaged using 1H-MRI and 23Na-MRSI. An infusion line was first established through cannulation of the tail vein as a means to administer fluids and the paraCAn-. During the cannulation procedure, the rat was placed on a heating pad to maintain physiological body temperature. A 30G needle, fitted onto a PE-10 line, was inserted into the tail vein while the animal was under anesthesia (also isoflurane 2–3%). The animal was then given Puralube Vet Ointment (Dechra, Overland Park, KS, USA) over the eyes and then situated in a prone position underneath an in-house built 23Na/1H quad surface coil before being placed in the magnet. The 2.5-cm 23Na coil was placed directly on top of the head, and the two 5-cm 1H coils flanked the head on the left and right sides. Breathing rate was measured by placement of a respiration pad under the torso, and temperature was monitored through a rectal fiber-optic probe thermometer.

Imaging was conducted on a 9.4 T horizontal-bore Bruker Avance system (Billerica, MA), interfaced with Bruker ParaVision v6.0.1 software running on CentOS. Rats weighed 200–260 g at the time of imaging. Positioning and power optimizations for 1H signals were performed using Bruker-defined gradient-echo (GE) and fast spin-echo (FSE) sequences. Shimming was done on the 1H coils using an ellipsoid region (12 × 7 × 11 mm3) to bring the water linewidth to less than 30 Hz using B0 mapping with second-order shim corrections. Pre-contrast 1H anatomical MRI was first performed using a spin-echo sequence with 9 axial slices (FOV: 25 × 9 × 25 mm3, 128 × 128 in-plane resolution) over 10 echo times TE (10 − 100 ms) with TR = 4 s). The multiple echo times enabled voxel-wise calculations of 1H T2 values. 23Na power optimizations were then performed using a 2-ms 90° Shinnar-Le Roux (SLR) RF pulse over a 4096 Hz bandwidth (ν0Na = 105.9 MHz at 9.4 T), where the optimal 90° pulse power was achieved using less than 8 W.

23Na-MRSI in 3D was performed without slice selection using an SLR pulse, where the FOV was 25 × 19 × 25 mm3 using a nominal voxel size of 1.0 × 1.0 × 1.0 mm3 (i.e., point-spread function was ~ 2.24 × 2.24 × 2.24 mm3)60, with TR = 300 ms, and phase encoding (gradient duration = 1 ms, sweep width = 8 kHz, encoding steps = 1027, k-space radius factor = 0.55) was done in all three spatial dimensions to avoid chemical shift artifacts caused by slice-selective RF pulses. A preliminary 23Na-MRSI scan (same parameters/conditions) was run before administering paraCAn-. The in vivo 1H-MRI delineated the tumor and brain boundary and permitted co-registration with 23Na-MRSI data, both before and after infusion of paraCAn-, enabling anatomical localization of 23Na-MRSI spectra at the voxel level. All spectra were line-broadened by 10 Hz and magnitude-corrected.

The animals were then given ~ 1 µL/g BW probenecid using a syringe pump (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA, USA) for 10 min followed by a 20-min waiting period. Then Na5TmDOTP (1 µmol/g BW) was co-infused with probenecid (same dose) at a rate of 15 µL/min. This infusion protocol with probenecid has been shown to increase TmDOTP5- retention in vivo without the need for renal ligation, and yielded ~ 0.1 µmol TmDOTP5-/g BW in the cortex and subcortex38. Moreover, the slow infusion rate allows TmDOTP5- diffusion/clearance into other tissue during the infusion, and therefore TmDOTP5- does not accumulate and remain exclusively in the vasculature. Post-contrast 23Na-MRSI was performed 30 min after the start of infusion and repeated subsequently thereafter during the infusion. The imaging session was concluded with post-contrast 1H-MRI under identical conditions. Rats were sacrificed following imaging by isoflurane inhalation overdose (5%) while the animal was already unconscious during imaging. Death was ensured by inducing bilateral pneumothorax.

1H-MRI and 23Na-MRSI results were processed and analyzed using home-written code in MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA). Voxel-wise T2 values for 1H were calculated by fitting MRI voxel intensities versus the series of TE values to a monoexponential curve e−TE/T2. Pre-contrast and post-contrast 1H T2 values were used to qualitatively ascertain the success of paraCAn- infusion. 3D 23Na-MRSI data were reconstructed using Fourier transformation in all spatial and temporal dimensions after 10-Hz line-broadening. Individual 23Na peaks were identified and integrated in MATLAB, guided by the changes observed in R2 maps from the 1H-MRI data which is roughly proportional to [TmDOTP5-] within each voxel. Due to line broadening induced by TmDOTP5-, the integration range was different for each compartment to capture the majority of each peak. Integration bandwidths were chosen based on in vitro results and amount of peak separation. The shift for each 23Na peak was based on the amount of TmDOTP5- present in each compartment, i.e., most shifted and broadest for blood compartment compared to the extracellular compartment, whereas the intracellular compartment was unshifted and narrowest. The ∆Na+mem values were calculated by subtracting ∫Na+i from ∫Na+e, and ∆Na+end by subtracting ∫Na+e from ∫Na+b.

1H-DCE-MRI studies

To measure vascular parameters [Ktrans (volume transfer coefficient, min-1), Fp (plasma flow rate, min-1), ve (extracellular volume fraction, unitless), vp (plasma volume fraction, unitless)] from a two-compartment exchange model (2XCM), 1H-DCE-MRI was performed on a subset of RG2 (9.4 T), U87 (11.7 T) and U251 (11.7 T) tumors. 1H-DCE-MRI data used a 1H volume-transmit (8-cm)/surface-receive (3.5-cm) coil.

Baseline images for T1 mapping were acquired using a rapid acquisition with relaxation enhancement (RARE) sequence with six TR values (0.4, 0.7, 1, 2, 4, 8 s). Seven 1-mm slices covering the extent of the tumor were chosen and images were acquired with a 25 × 25 mm FOV, 128 × 128 matrix and TE of 10 ms. 1H-DCE-MRI acquisition consisted of a dynamic dual-echo spoiled GE sequence with a temporal resolution of 5 s. Images were acquired with TR = 39.1 ms, TE = 2.5/5 ms, flip angle = 15°, and one average. Three central slices of the tumor were chosen with identical positioning, FOV (25 × 25 mm), and matrix (128 × 128) to be co-registered to the T1 data. The sequence was repeated every 5 s over a 22 min period with 0.25 µmol/g gadobutrol (Bayer, AG), a gadolinium (Gd3+)-containing contrast agent, injected 2 min after the start of the sequence and then flushed with 100 µL heparinized saline. The multi-TR T1 sequence was then repeated at the end of the 1H-DCE-MRI acquisition to serve as a post-Gd3+ T1 mapping which was used to delineate tumor boundaries. Quantitative T1 maps were generated by fitting voxel-level data to a monoexponential function in MATLAB.

Measurements from T1-weighted images before Gd3+ injection were used to transform time-intensity curves into time-concentration curves after the bolus injection. The region of interest (ROI) was placed inside the tumor area, including the rim, as determined by the region of contrast enhancement/uptake. All analysis, including masking the ROI, was performed in MATLAB using the same home-written code. The arterial input function (AIF) was measured by collecting arterial blood samples at discrete time points post-injection. The raw AIF was fit to a bi-exponential curve with a linear upslope during injection of Gd3+. Plasma [Gd3+] was derived from the blood [Gd3+] using a hematocrit of 0.45. The time resolution and duration interval used downstream in the analysis pipeline were adjusted manually.

The exchange-model parameters were estimated by fitting each voxel using Levenberg–Marquardt regression. Because Ktrans fitting often converged on local minima instead of the desired global minimum, multiple starting values were used, ultimately choosing the one with the smallest residual. Other variables were less sensitive to the initial condition so a single starting value sufficed.

Statistics

All statistical comparisons were performed in MATLAB using a 2-sample Student’s t-test (i.e., data passed normality tests with Prism in GraphPad, San Diego, CA) whose null hypothesis claimed there was no difference between the means of the two populations being tested. The populations in our analysis were compartmental and gradient 23Na signal values (i.e., means and standard deviations of voxel-wise integrals) between tumor and normal tissue and between cohorts of different tumors. For 1H-DCE-MRI studies, the populations were different parameter values between different tumors. In all cases, a significance level of 0.05 was used.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Health awarded to F.H. (R01 EB-023366, R01 MH-067528) and J.J.W. (T32 GM007205, Yale Medical Scientist Training Program).

Author contributions

M.H.K., D.C. and F.H. designed experiments. M.H.K., J.J.W. and J.M.M. conducted experiments and conducted data analysis. M.H.K., J.J.W. and S.K.M. prepared tumor cells. D.C. and F.H. supervised experiments and analysis. M.H.K., J.J.W., J.M.M. and F.H. evaluated results and wrote the manuscript.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this manuscript are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained an error in Figure 4 where MRI images (far left column) had multiple white circles.

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

6/8/2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41598-021-91581-w

Contributor Information

Muhammad H. Khan, Email: muhammad.khan@yale.edu

Fahmeed Hyder, Email: fahmeed.hyder@yale.edu.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-85925-9.

References

- 1.Bean BP. The action potential in mammalian central neurons. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007;8:451–465. doi: 10.1038/nrn2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ennis SR, Ren XD, Betz AL. Mechanisms of sodium transport at the blood-brain barrier studied with in situ perfusion of rat brain. J. Neurochem. 1996;66:756–763. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.66020756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hannon MJ, Verbalis JG. Sodium homeostasis and bone. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2014;23:370–376. doi: 10.1097/01.mnh.0000447022.51722.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Juel C. Potassium and sodium shifts during in vitro isometric muscle contraction, and the time course of the ion-gradient recovery. Pflugers Arch. 1986;406:458–463. doi: 10.1007/BF00583367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stock C, Grønlien HK, Allen RD, Naitoh Y. Osmoregulation in Paramecium: In situ ion gradients permit water to cascade through the cytosol to the contractile vacuole. J. Cell Sci. 2002;115:2339–2348. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199808063390607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boron WF. Regulation of intracellular pH. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 2004;28:160–179. doi: 10.1152/advan.00045.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Green K, Cheeks L, Hull DS. Effect of ambient pH on corneal endothelial sodium fluxes. Invest Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1986;27:1274–1277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hladky SB, Barrand MA. Fluid and ion transfer across the blood-brain and blood-cerebrospinal fluid barriers; a comparative account of mechanisms and roles. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2016;13:19. doi: 10.1186/s12987-016-0040-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shah S, Kimberly WT. Today's approach to treating brain swelling in the neuro intensive care unit. Semin. Neurol. 2016;36:502–507. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1592109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stokum JA, Kurland DB, Gerzanich V, Simard JM. Mechanisms of astrocyte-mediated cerebral edema. Neurochem. Res. 2015;40:317–328. doi: 10.1007/s11064-014-1374-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erecinska M, Dagani F. Relationships between the neuronal sodium/potassium pump and energy metabolism. Effects of K+, Na+, and adenosine triphosphate in isolated brain synaptosomes. J. Gen. Physiol. 1990;95:591–616. doi: 10.1085/jgp.95.4.591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeBerardinis RJ, Chandel NS. Fundamentals of cancer metabolism. Sci. Adv. 2016;2:e1600200–e1600200. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1600200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hyder F, Manjura Hoque S. Brain tumor diagnostics and therapeutics with superparamagnetic ferrite nanoparticles. Contrast Med. Mol. Imaging. 2017;2017:6387217. doi: 10.1155/2017/6387217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roger S, Gillet L, Le Guennec JY, Besson P. Voltage-gated sodium channels and cancer: Is excitability their primary role? Front. Pharmacol. 2015;6:152. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2015.00152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alfarouk KO, et al. The interplay of dysregulated ph and electrolyte imbalance in cancer. Cancers. 2020 doi: 10.3390/cancers12040898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Onitilo AA, Kio E, Doi SA. Tumor-related hyponatremia. Clin. Med. Res. 2007;5:228–237. doi: 10.3121/cmr.2007.762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cone CD. Variation of the transmembrane potential level as a basic mechanism of mitosis control. Oncology. 1970;24:438–470. doi: 10.1159/000224545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnstone BM. Micro-electrode penetration of ascites tumour cells. Nature. 1959;183:411. doi: 10.1038/183411a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang M, Brackenbury WJ. Membrane potential and cancer progression. Front. Physiol. 2013 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petersen CCH. Whole-cell recording of neuronal membrane potential during behavior. Neuron. 2017;95:1266–1281. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Folkman J. Angiogenesis. Annu. Rev. Med. 2006;57:1–18. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.57.121304.131306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Batchelor TT, Reardon DA, de Groot JF, Wick W, Weller M. Antiangiogenic therapy for glioblastoma: Current status and future prospects. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014;20:5612–5619. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anderson CF, Record MT, Hart PA. Sodium-23 NMR studies of cation-DNA interactions. Biophys. Chem. 1978;7:301–316. doi: 10.1016/0301-4622(78)85007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hilal SK, et al. In vivo NMR imaging of tissue sodium in the intact cat before and after acute cerebral stroke. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 1983;4:245–249. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moseley ME, et al. In vivo sodium-23 magnetic resonance surface coil imaging: Observing experimental cerebral ischemia in the rat. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 1985;3:383–387. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(85)90402-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Madelin G, Lee J-S, Regatte RR, Jerschow A. Sodium MRI: Methods and applications. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2014;79:14–47. doi: 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Madelin G, Poidevin F, Makrymallis A, Regatte RR. Classification of sodium MRI data of cartilage using machine learning. Magn. Reson. Med. 2015;74:1435–1448. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Madelin G, Babb J, Xia D, Regatte RR. Repeatability of quantitative sodium magnetic resonance imaging for estimating pseudo-intracellular sodium concentration and pseudo-extracellular volume fraction in brain at 3 T. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0118692. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Madelin G, Kline R, Walvick R, Regatte RR. A method for estimating intracellular sodium concentration and extracellular volume fraction in brain in vivo using sodium magnetic resonance imaging. Nat. Publ. Group. 2014;4:4763. doi: 10.1038/srep04763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chu SC, et al. Aqueous shift reagents for high-resolution cationic nuclear magnetic resonance. III. Dy(TTHA)3−, Tm(TTHA)3−, and Tm(PPP)27−. J. Magn. Reson. 1984;56:33–47. doi: 10.1016/0022-2364(84)90189-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chu SC, Xu Y, Balschi JA, Springer CS. Bulk magnetic susceptibility shifts in NMR studies of compartmentalized samples: Use of paramagnetic reagents. Magn. Reson. Med. 1990;13:239–262. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910130207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weidensteiner C, Horn M, Fekete E, Neubauer S, von Kienlin M. Imaging of intracellular sodium with shift reagent aided 23Na CSI in isolated rat hearts. Magn. Reson. Med. 2002;48:89–96. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Colet, J.-M., Makos, J. D., Malloy, C. R. & Sherry, A. D. Determination of the Intracellular Sodium Concentration in Perfused Mouse Liver by 31P and 23Na Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. 155–159 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Bansal N, Germann MJ, Lazar I, Malloy CR, Sherry AD. In vivo Na-23 MR imaging and spectroscopy of rat brain during TmDOTP5- infusion. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging JMRI. 1992;2:385–391. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880020405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coman D, et al. Imaging the intratumoral-peritumoral extracellular pH gradient of gliomas. NMR Biomed. 2016;29:309–319. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coman D, Trubel HK, Hyder F. Brain temperature by biosensor imaging of redundant deviation in shifts (BIRDS): Comparison between TmDOTP 5âand TmDOTMA â. NMR Biomed. 2009 doi: 10.1002/nbm.1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coman D, Trubel HK, Rycyna RE, Hyder F. Brain temperature and pH measured by 1H chemical shift imaging of a thulium agent. NMR Biomed. 2009;22:229–239. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang Y, et al. Towards longitudinal mapping of extracellular pH in gliomas. NMR Biomed. 2016;29:1364–1372. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ronen I, Kim SG. Measurement of intravascular Na(+) during increased CBF using (23)Na NMR with a shift reagent. NMR Biomed. 2001;14:448–452. doi: 10.1002/nbm.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Winter PM, et al. Quantitation of intracellular [Na+] in vivo by using TmDOTP5—as an NMR shift reagent and extracellular marker. J. Appl. Physiol. 1998;85:1806–1812. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.85.5.1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Winter PM, Bansal N. TmDOTP(5-) as a (23)Na shift reagent for the subcutaneously implanted 9L gliosarcoma in rats. Magn. Reson. Med. 2001;45:436–442. doi: 10.1002/1522-2594(200103)45:3<436::AID-MRM1057>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sourbron SP, Buckley DL. Classic models for dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI. NMR Biomed. 2013;26:1004–1027. doi: 10.1002/nbm.2940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Driver ID, Stobbe RW, Wise RG, Beaulieu C. Venous contribution to sodium MRI in the human brain. Magn. Reson. Med. 2020;83:1331–1338. doi: 10.1002/mrm.27996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gilles A, Nagel AM, Madelin G. Multipulse sodium magnetic resonance imaging for multicompartment quantification: Proof-of-concept. Nat. Publ. Group. 2017;7:17435–17419. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-17582-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huhn K, Engelhorn T, Linker RA, Nagel AM. Potential of sodium MRI as a biomarker for neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation in multiple sclerosis. Front. Neurol. 2019;10:84. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.00084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Meyer MM, et al. Cerebral sodium (23Na) magnetic resonance imaging in patients with migraine—a case–control study. Eur. Radiol. 2019;29:7055–7062. doi: 10.1007/s00330-019-06299-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ridley B, et al. Distribution of brain sodium long and short relaxation times and concentrations: A multi-echo ultra-high field 23Na MRI study. Nat. Publ. Group. 2018;8:4357–4312. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-22711-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim S-G, Ogawa S. Biophysical and physiological origins of blood oxygenation level-dependent fMRI signals. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32:1188–1206. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ogawa S, et al. Functional brain mapping by blood oxygenation level-dependent contrast magnetic resonance imaging. A comparison of signal characteristics with a biophysical model. Biophys. J. 1993;64:803–812. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(93)81441-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ogawa S, Lee T-M. Magnetic resonance imaging of blood vessels at high fields: In vivo andin vitro measurements and image simulation. Magn. Reson. Med. 1990;16:9–18. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910160103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aas AT, Brun A, Blennow C, Strömblad S, Salford LG. The RG2 rat glioma model. J. Neurooncol. 1995;23:175–183. doi: 10.1007/BF01059948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jiang Y, et al. MAP30 promotes apoptosis of U251 and U87 cells by suppressing the LGR5 and Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway, and enhancing Smac expression. Oncol. Lett. 2018;15:5833–5840. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.8073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Candolfi M, et al. Intracranial glioblastoma models in preclinical neuro-oncology: Neuropathological characterization and tumor progression. J. Neurooncol. 2007;85:133–148. doi: 10.1007/s11060-007-9400-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Radaelli E, et al. Immunohistopathological and neuroimaging characterization of murine orthotopic xenograft models of glioblastoma multiforme recapitulating the most salient features of human disease. Histol. Histopathol. 2009;24:879–891. doi: 10.14670/HH-24.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hosono J, Morikawa S, Ezaki T, Kawamata T, Okada Y. Pericytes promote abnormal tumor angiogenesis in a rat RG2 glioma model. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2017;34:120–129. doi: 10.1007/s10014-017-0291-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lavon I, et al. Novel mechanism whereby nuclear factor kappaB mediates DNA damage repair through regulation of O(6)-methylguanine-DNA-methyltransferase. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8952–8959. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Qiu ZK, et al. Enhanced MGMT expression contributes to temozolomide resistance in glioma stem-like cells. Chin. J. Cancer. 2014;33:115–122. doi: 10.5732/cjc.012.10236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Maritim S, et al. Mapping extracellular ph of gliomas in presence of superparamagnetic nanoparticles: Towards imaging the distribution of drug-containing nanoparticles and their curative effect on the tumor microenvironment. Contrast Med. Mol. Imaging. 2017;2017:3849373. doi: 10.1155/2017/3849373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rao JU, et al. Temozolomide arrests glioma growth and normalizes intratumoral extracellular pH. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:7865. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-07609-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Coman D, de Graaf RA, Rothman DL, Hyder F. In vivo three-dimensional molecular imaging with Biosensor Imaging of Redundant Deviation in Shifts (BIRDS) at high spatiotemporal resolution. NMR Biomed. 2013;26:1589–1595. doi: 10.1002/nbm.2995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Coman D, Sanganahalli BG, Jiang L, Hyder F, Behar KL. Distribution of temperature changes and neurovascular coupling in rat brain following 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, "ecstasy") exposure. NMR Biomed. 2015;28:1257–1266. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Walsh JJ, et al. Dynamic thermal mapping of localized therapeutic hypothermia in the brain. J. Neurotrauma. 2020;37:55–65. doi: 10.1089/neu.2019.6485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Trübel HKF, Maciejewski PK, Farber JH, Hyder F. Brain temperature measured by 1H-NMR in conjunction with a lanthanide complex. J. Appl. Physiol. 2003;94:1641–1649. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00841.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]