Abstract

Heart rate variability biofeedback (HRVB) has been used for a number of years to treat depressive symptoms, a common mental health issue, which is often comorbid with other psychopathological and medical conditions. The aim of the present meta-analysis is to test whether and to what extent HRVB is effective in reducing depressive symptoms in adult patients. We conducted a literature search on Pubmed, ProQuest, Ovid PsycInfo, and Embase up to October 2020, and identified 721 studies. Fourteen studies were included in the meta-analysis. Three meta-regressions were also performed to further test whether publication year, the questionnaire used to assess depressive symptoms, or the interval of time between T0 and T1 moderated the effect of HRVB. Overall, we analysed 14 RCTs with a total of 794 participants. The random effect analysis yielded a medium mean effect size g = 0.38 [95% CI = 0.16, 0.60; 95% PI = − 0.19, 0.96], z = 3.44, p = 0.0006. The total heterogeneity was significant, QT = 23.49, p = 0.03, I2 = 45%, which suggested a moderate variance among the included studies. The year of publication (χ2(1) = 4.08, p = 0.04) and the questionnaire used to assess symptoms (χ2(4) = 12.65, p = 0.01) significantly moderated the effect of the interventions and reduced heterogeneity. Overall, results showed that HRVB improves depressive symptoms in several psychophysiological conditions in adult samples and should be considered as a valid technique to increase psychological well-being.

Subject terms: Physiology, Psychology, Health care

Introduction

Depression is one of the most common mental health conditions, globally affecting about 265 million people of all ages (World Health Organization1). Low mood, loss of interest, sleep disturbances, reduced appetite, slowed thinking and lack of energy have been identified as potential risk factors for the onset and persistence of other diseases: people suffering from depression are more likely to have substance use issues, personality disorders, or other psychological problems (e.g., distress, anxiety)2.

A worldwide study conducted on 245,404 people from 60 different countries, showed that patients suffering from chronic diseases were more likely to show comorbidity with depression3. Moreover, depressive symptoms are often associated with poor health outcomes4, noncompliance with medications and treatments5, and are often comorbid with medical issues such as type 2 diabetes6 and dementia7.

Furthermore, depressive symptoms are associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular disease8,9. Patients with heart disease tend to show a higher prevalence of comorbid depression, while post-stroke survivors frequently report depressive symptoms up to 5 years after the cerebrovascular event10–12.

Several interventions have been developed to alleviate depressive symptoms: psychotherapy, antidepressant medication, and physical exercises being the most frequent treatments employed13–15. Beyond pharmacological treatment, the Health Evidence Network16 reported that the most effective psychotherapeutic interventions for the depression management are supportive counselling and psychodynamic, interpersonal or cognitive behavioural therapies (CBT). Specifically, different studies have shown that drugs and CBT are equally effective at reducing depressive symptoms in acute, short-term conditions17; while CBT has demonstrated greater mid-term and long-term effects than antidepressants14. In recent years, new psychotherapeutic approaches have focused on treating depression: mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT)—a combination of CBT and mindfulness meditation practice—and the so-called “third-wave” therapies have reported significant improvements in depressive symptoms18–20. However, these psychotherapeutic approaches do not directly focus on the regulation of physiological outcomes that are highly affected in depressive syndromes21–23. Besides psychosocial factors, negative emotional symptoms of depression are associated with autonomic nervous system responses, thus involving skin conductance, respiratory and heart rates21,24,25.

A key marker of the autonomous nervous system function and a potent predictor of physical morbidity and mortality is heart rate variability (HRV), a measure of the variation in time between each heartbeat. Greater variability indicates greater ability of the autonomic nervous system to regulate itself. This parameter may be used as a diagnostic and predictive bio-marker of depression, since more severe symptoms are significantly associated with reduced HRV26–28 and reduced HRV itself seems to be implicated in the risk of developing depression29.

HRV findings led to the implementation of a new technique widely used in several physical illnesses and mental disorders: HRV Biofeedback (HRVB), a non-invasive therapy training aiming at increasing heart rate oscillations through real time feedback and slow breathing training30. This intervention has been implemented for issues in regulating HRV, which were observed in depression treatment31,32. Previous studies demonstrated that HRVB improves HRV as measured by standard deviation of normal-to-normal intervals (SDNN), high-frequency power (HF) and low-frequency power/high-frequency power ratio (LF/HF). All of these physiological indices are associated with amelioration of depressive symptoms26,32,33.

Numerous studies have demonstrated the positive effect of HRVB in reducing physical and psychological symptoms and increasing wellbeing34–38. Furthermore, two meta-analyses were recently conducted to assess the efficacy of biofeedback on mental health.

Goessl et al. conducted a random-effects meta-analysis on the effects of HRVB on symptoms of anxiety and stress, finding that the HRVB is a useful and effective technique for improving self-reported stress and anxiety39.

Lehrer et al.40 recently performed a systematic and meta-analytic review on the efficacy of HRVB and/or paced breathing (approximately six breaths/min) on a wide range of psychological symptoms (including depressive symptoms), mental functions and complex behaviours (such as athletic/artistic performance). The investigators found a significant small effect of HRVB and paced breathing on depression24.

However, no meta-analyses have been specifically conducted on randomized controlled studies to investigate the specific effect of HRVB in adults with depressive symptoms (i.e. patients with depressive disorders or with depressive symptoms in comorbidity with other psychological or physical conditions). To fill this gap, the aim of our meta-analysis is to estimate the effect of HRVB in reducing depressive symptoms.

Material and methods

Search strategy and inclusion criteria

To identify potential studies for inclusion in the meta-analysis, we conducted a search of the published literature using the following scientific online databases: Pubmed (all years), Proquest (all years), Ovid PsycInfo (all years), and Embase (all years). Search criteria were: (“heart rate variability biofeedback” OR “HRV biofeedback”) AND (“depression” OR “depressive”). No time restrictions were applied. The full search strategies were reported in Online Appendix A.

The literature search was conducted up to October 2020.

Study selection

One of the authors conducted a systematic literature search. Two other authors selected papers for full review based on inclusion and exclusion criteria and assessed their eligibility. Agreement was reached on the final selection of included studies.

Inclusion criteria were: (1) English-language publication, (2) work included an HRV biofeedback intervention, (3) randomized clinical trial (RCT), (4) peer-reviewed publication, and (5) work involved adult participants.

Review strategy and data extraction

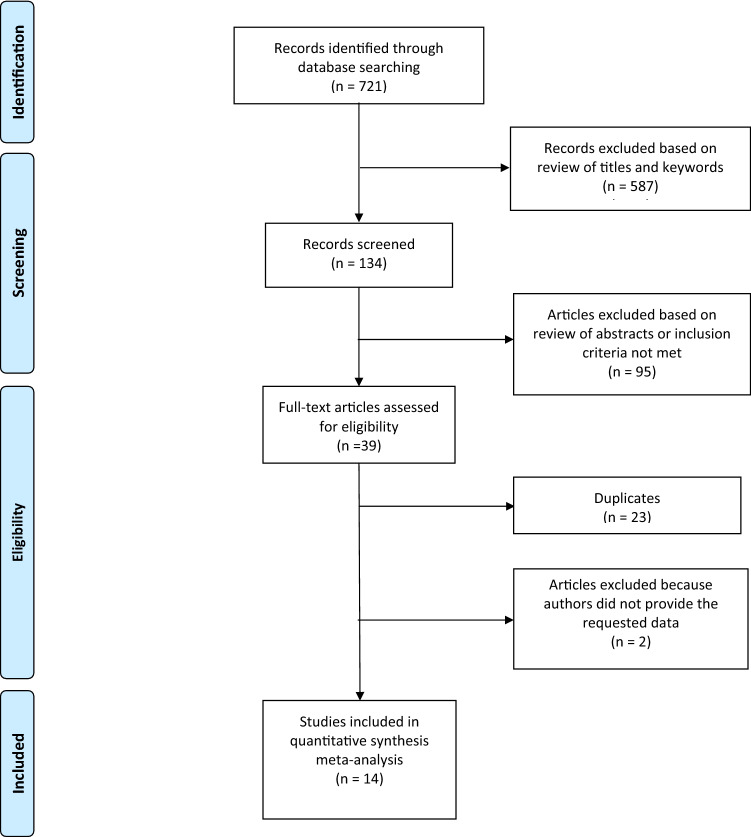

A total of 721 articles were identified and retrieved. After the first screening of title and abstract, 134 studies remained. After a full-text examination, 95 studies were excluded. 2 studies reported incomplete data41,42; corresponding authors were contacted, none provided the requested data, and those studies were therefore excluded. The remaining 14 studies were included in the present meta-analysis26,35,43–54.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were applied. The flowchart is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart illustrating study selection, review strategy and data extraction.

Effect size calculation

The level of depressive symptoms was our dependent variable of interest. From each study we extracted: sample size, and mean and standard deviation of participants’ scores in the various conditions for the variable of interest.

The effect size used was Hedges’ g55, which is a standardized mean difference that accounts for sampling variance difference between conditions. The effect size and variance calculation were performed using R-Studio (RStudio Team 2015) and its package compute.es56 using the command mes when mean and standard deviations were available or pes when only p-values were reported. Effect sizes were computed comparing participants measures at time 1 (T1) between intervention vs. control group. This criterion was violated only for one study45, in which T1 was at 2 weeks and time 2 (T2) at 5 weeks; in this case we used T2 values. We decided to use the data collected at T2 in order to improve timing coordination with the other included studies, which all had T1s at least at 4 weeks after the end of the training.

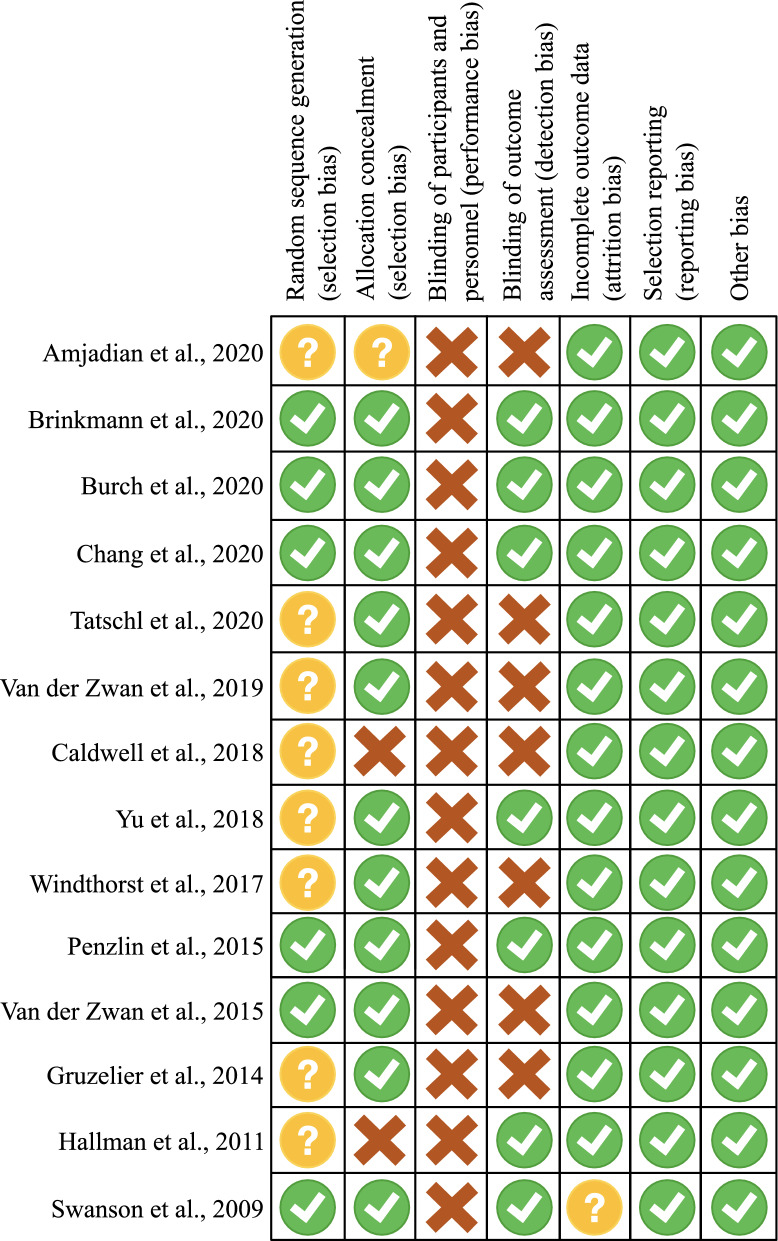

Risk of bias assessment

Risk of bias was assessed with the tool recommended by Cochrane guidelines57. Included RCTs were analysed according to random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other bias. Each source of bias was rated as yes (“low risk of bias”), no (“high risk of bias”), or unclear (“moderate risk of bias”). Disagreements in bias scoring were resolved by discussions among the two reviewers.

Data analysis

In order to assess whether HRVB can successfully reduce depressive symptoms and quantify the effect of the modulation, we performed one random-effects meta-analysis using the restricted maximum-likelihood estimation method. We also carried out three distinct meta-regressions to assess whether the year of publication of the study, the test used to evaluate depressive symptoms, or the timing of T1, moderated the observed effect.

The within-studies heterogeneity was evaluated using the Q-test. A significant p-value of the Q-test implies that the observed within-studies variance can be explained by other variables besides HRVB. In addition, we used as index of heterogeneity Higgins’ I258, which provides the percentage of the total variability in the effect size estimation that could be attributed to heterogeneity among the true effects (heterogeneity is considered high if I2 > 75%, Higgins et al.58). To further investigate heterogeneity, we also computed prediction intervals (PI) of the effect, which quantify the dispersion of effect. That is, 95% PI indicate the range of values that the effect size of a future study similar to those included should probably take (Borenstein et al.55).

Publication bias was evaluated using funnel plots and the trim-and-fill method (Duval 2005). The trim-and-fill method provides an estimate the number of studies missing from the meta-analysis due to the suppression of the most extreme results on one side (generally the left, i.e., non-significant results) of the plot. To further explore the publication bias, the Egger’s test59 was performed. The Egger’s test examines the correlation between the various effect sizes and their sampling variances (i.e., if the funnel plot is asymmetric), and a significant p-value indicates publication bias60. To explore the robustness of the results, we performed a leave-one-out analysis: this procedure evaluates the robustness of the effect excluding one study at a time. The meta-analyses performed, and the related plots were computed using the R-package metafor61.

Results

Summary of findings

The characteristics of the included trials are reported in Online Appendix B. The studies included in our meta-analysis were conducted between 2009 and 2020. The sample size varied from 20 to 134; all the studies used a between-subject design. A total of 14 RCTs were analysed on a total of 794 patients divided into experimental (M age = 46.17 SD = 7.72, 42.72% female) and control (M age = 46.81, SD = 7.17, 44.5% female) groups. Among the studies, two were conducted in Taiwan35,43, two in Netherlands44,47, three in the USA26,46,54, three in Germany45,49, one in the UK, one in Austria, one Iran and one in Sweden48,50,51,53. Nine studies were conducted on patients with cardiovascular disease, stress symptoms, cancer or alcohol disorder, while the remaining five studies focused on non-clinical samples26,44,47,48,52.

Of the 14 studies included, all evaluated depression with reliable instruments: six assessed depression through the BDI-II62, four through the DASS63, two through the HADS43, one employed the PHQ-964 and one the CED-S65. Overall, the time range of the follow up ranged from five weeks post end-of-intervention48,53, to 12 months after the intervention35,53.

Risk of bias

Figure 2 reported risk of bias assessment. None of the included studies withheld information on interventions from trial participants. Eight trials did not report how randomization was performed. In seven studies, the assessment of outcomes by researchers was blinded. Overall, most information was from trials at low or unclear risk of bias.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias assessment. Low risk of bias is represented with green dots, high risk of bias in red, unclear risk of bias in yellow.

HRVB and depressive symptoms

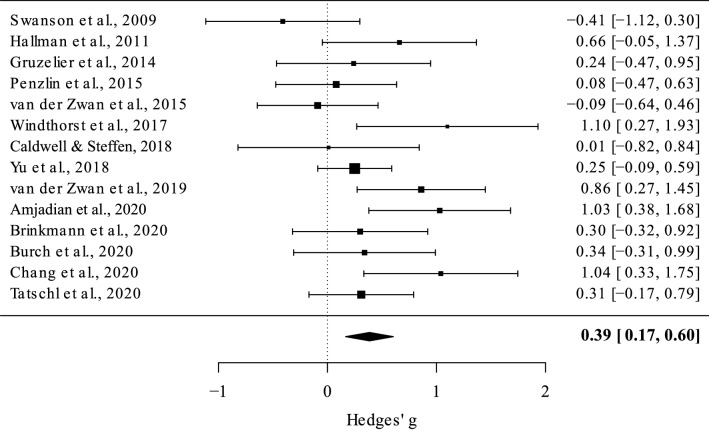

The random effect analysis (N = 14) showed a medium mean effect size, g = 0.38 [95% CI 0.16, 0.60; 95% PI = − 0.19, 0.96], z = 3.44, p = 0.0006, meaning that HRVB has a positive effect in reducing depressive symptoms. Total heterogeneity was significant, QT = 23.49, p = 0.03, I2 = 45%, suggesting moderate variance across the studies included (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Forest plot, each square corresponds to one study and the lines represent 95% confidence interval. The size of each square represents the weight of the study. The diamond at the bottom represents the cumulative effect size with 95% confidence interval. Higher positive values indicate greater effect of the HRVB intervention compared with the control group.

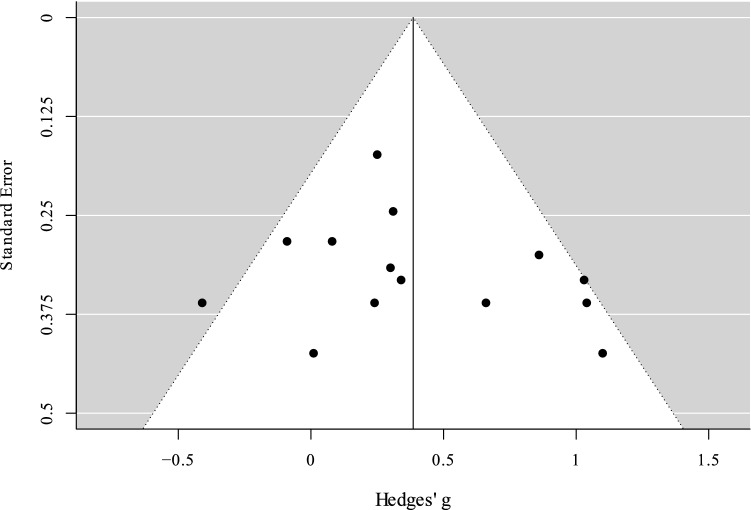

The sensitivity analysis showed that the effect size ranged between 0.33 and 0.42 (M = 0.38, SD = 0.03). The trim-and-fill method added no hypothetical missing studies on the left side of the funnel plot (Fig. 4). The Eggers test was not significant, z = 0.85, p = 0.39, suggesting no publication bias.

Figure 4.

Funnel plot. Black dots represent studies included in the present meta-analysis. The vertical line represents the effect size.

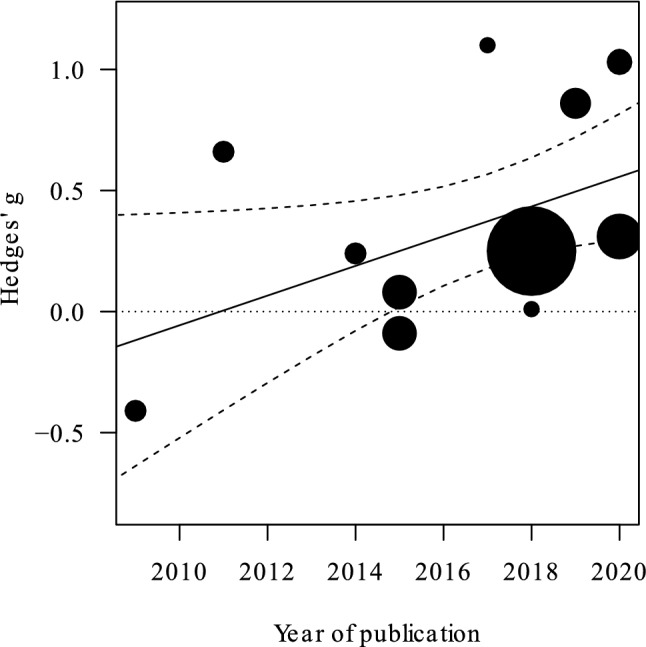

The meta-regression performed using the year of publication as moderator (N = 14) showed that the test on the moderator was significant, χ2(1) = 4.08, p = 0.04, estimate = 0.06. The heterogeneity became not significant, QT = 18.14, p = 0.11, and Higgins’ I2 decreased, I2 = 0%. The decrease in heterogeneity suggests that the year of publication plays a role in determining the differences in the effects reported by the various studies; in particular, most recent studies reported higher effect sizes (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Plot illustrating the relationship between year of publication and cumulative effect sizes. In particular, the most recent the study, the greater the effect size. The area of the points is proportional to study variances. Three studies published in 2020 are not reported due to overlapping positions. Dashed lines indicate 95% CI, the dotted line indicate Hedges' g = 0 (i.e., no difference between groups).

The meta-regression performed using the test used to evaluate depressive symptoms as moderator (N = 14) showed that the test on the moderator was significant, χ2(4) = 12.65, p = 0.01. The heterogeneity became not significant, QT = 10.23, p = 0.33, and Higgins’ I2 decreased, I2 = 7%. The decrease in heterogeneity suggests that the test used to evaluate depressive symptoms plays a role in determining the differences in the effects reported by the various studies. Critically, when depressive symptoms were assessed using CES-D, the effect size was not significantly different from zero, while when they were measured by means of BDI-II, DASS, HADS or PHQ-9 the effect size was significantly different from zero (Table 1).

Table 1.

Hedges’ g calculated using the questionnaire used to evaluate depressive symptoms as moderator.

| TEST | BDI-II | CES-D | DASS | HADS | PHQ-9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hedges’ g | 0.23 | − 0.41 | 0.48 | 0.85 | 1.10 |

| 95% CI | [0.01, 0.45] | [− 1.13, 0.31] | [0.17, 0.80] | [0.33, 1.36] | [0.25, 1.94] |

| Number of studies | N = 6 | N = 1 | N = 4 | N = 2 | N = 1 |

The meta-regression performed using the timing of T1 as moderator (N = 14) showed that the test on the moderator was not significant, χ2(1) = 1.40, p = 0.23, estimate = 0.09. The heterogeneity remained significant, QT = 21.30, p = 0.04, and Higgins’ I2 remained stable, I2 = 43%. The lack of effect of the moderator suggests that timing of T1 does not play a role in determining the differences in the effects reported by the various studies.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis of RCTs on the impact of HRVB on the reduction of depressive symptoms in different pathological conditions in adult samples.

We selected and analysed 14 published RCTs, including a total of 794 subjects, and examined the effectiveness of HRVB for symptoms of depression in adults compared to control conditions or other active treatments.

Overall, we observed that the HRVB exert a positive and statistically significant (moderate) effect in reducing depressive symptoms after intervention, compared to other control and active conditions. This is partially in line with the significant effect found in the recent meta-analysis on HRVB and/or paced breathing by Lehrer et al.40. Considering the previous recent meta-analysis, which found a significant yet small effect size of HRV on depression, we found a slightly higher effect. Such a difference might be due to the fact that Lehrer et al.40 assessed the efficacy of both HRVB and paced-breathing and that we included five recent studies43,51–54, which were not included in the previous meta-analysis.

We found statistically significant heterogeneity, indicating moderate variance across the included studies. However, when testing for the role of two (i.e., the year of publication of the study and the test used to evaluate depressive symptoms) of the three moderators included in the meta-regressions, heterogeneity decreased and became not significant. Conversely, the timing of T1 did not moderate the observed effect, a result which is in line with the previous meta-analysis40, which found that the length of interventions did not influence the effect size.

The effects of the moderators “year of publication” and “questionnaire used” were significant, suggesting that both predictors played a role in determining the effect of HRVB on depressive symptoms.

The year of publication moderated the effect of the intervention, in the direction of larger effect sizes for recent studies. The most recent studies we included had usual care and active control groups and conducted the interventions on participants with heterogeneous features (cardiovascular disease, psychiatric illnesses and no medical condition)43,51–54, thus it is unlikely that those specific features had an influence in moderating the effects.

It is possible that in recent years biofeedback devices may have become easier and more user-friendly for participants, capable of giving more sophisticated visual feedback, and thus contributing to increased effectiveness of HRVB.

Considering the effect of the test employed, we found that the significant positive Hedges’ g ranged from small to high effect sizes (0.23–1.10) and that the only questionnaire which was associated with a non-significant effect was CES-D. These findings should be interpreted with caution, since only one study employed CES-D as an instrument46 and it was the unique study that did not find an improvement of depressive symptoms. Thus, the numerosity of the studies using a specific questionnaire might have influenced the significance of the moderation. However, considering these results, we believe that future studies should be conducted in which the specific features of depression of interest to researchers and clinicians are carefully chosen, with particular consideration given to the time range of the interventions.

In the present meta-analysis, the questionnaires were designed to assess the presence, the severity or the frequency of depressive symptoms only (BDI-II, CES-D, PHQ-9) or of depressive signs together with other symptoms (HADS, DASS) in a time period ranging from 1 week prior to the administration (CES-D, HADS, DASS) to 2 weeks before (PHQ-9, BDI-II) among heterogenous samples. These might be among the reasons why questionnaires were found to moderate the efficacy of the interventions. We speculate that for HRVB studies, questionnaires that screen for the presence of symptoms within 1 week before the time of administration might provide a more precise picture of the efficacy of the interventions, since those that measure the presence of symptoms for 2 weeks before have a fair degree of overlap with the period of the intervention itself.

We consider the results of the present meta-analysis to be reliable, due to our test and adjustment for publication bias. Specifically, we utilized the rank-based trim-and-fill method, which assesses and adjusts results for publication bias depending on funnel plot asymmetry. According to the trim-and-fill method and to the Egger’s test, our results were minimally impacted by publication bias.

Furthermore, the robustness of results, evaluated through a sensitivity analysis, yielded results consistent with the conclusion that HRVB interventions have a positive effect on depressive symptoms. That is, the exclusion of one study at a time through the sensitivity analysis showed the results are not driven by the effect size of only one study. Indeed, the effect size ranged between.33 and 0.42 with a low standard deviation (SD = 0.03).

Additionally, consistent with our findings, two studies excluded in the selection procedure due to lack of data41,42 reported a decrease in depressive symptoms in biofeedback groups compared to the control group.

Clinical implications

Depression is one of the most widespread mental diseases, and it occurs in people of all ages across all world regions with more than 264 million people affected (World Health Organization1). Furthermore, people with multimorbidity are two to three times more likely to have depression compared to people without multimorbidity or those who have no chronic physical condition66.

Autonomic changes are often found in altered mood states and appear to be a central biological substrate linking depression to several physical dysfunctions23.

Among autonomic indexes, heart rate variability (HRV) is a significant health marker. Critically, the decrease in HRV that occurs during depression states does not return to normal levels as a consequence of existing psychotherapy or pharmacological treatment, even when the psychological outcome is positive26. It is worth noting that HRV may also inform research into the prevention and treatment of depression in later life24.

Our findings suggest that HRVB is an effective intervention for the reduction of depressive symptomatology when compared to control or active conditions and, even more importantly, HRVB yielded an effect size that is comparable to other broadly applied approaches (such as CBT)67. Interestingly, HRVB intervention is effective also in the treatment of anxiety and perceived stress, with a high reduction of symptoms (Hedges’ g = 0.83) in treated groups compared to controls39. As a consequence, HRVB might constitute a valuable intervention for patients with symptoms of both anxiety and depression, which often co-occur in the same individual and that can be considered bi-directional risk factor for one another68.

Furthermore, the possibility of treating depressive symptoms (and anxiety) among patients with other physical diseases, might render HRVB a suitable intervention for patients with both distressing physical conditions and an emotional burden, such as cancer patients69,70.

Limitations and future directions

To date, there is no specific evidence on which specific pathophysiological conditions, among those included in the present meta-analysis, might derive most benefit from HRVB intervention; nor can it be concluded which biofeedback protocol and devices yield the best results.

As things currently stand, conclusions on specific subsamples or on the severity of the symptoms cannot be drawn. More RCTs are warranted to clarify the effect on specific samples and to perform subgroup analyses according to clinical characteristics of the sample. Such analyses would lead to the possibility of personalizing the interventions based upon the particular characteristics of each individual patient71,72.

Furthermore, the measurements of depression in patients presently rely on a subjective scale, and even though we included studies which made use of reliable and standardized scales, the lack of objective assessment might have introduced a risk of bias in the measurement of the relevant outcomes. Thus, measurement tools that provide data with higher reliability and validity should be utilized in future studies, possibly employing objective measurements, such as neuroimaging data73. Furthermore, questionnaires might be used to assess which specific depressive features are alleviated by biofeedback (for example, somatic complaints and cognitive signs).

Conclusions

According to the present meta-analysis, HRVB offers a useful tool for treating depressive symptoms in patients with psychological or medical diseases, although its effectiveness on specific conditions remains unclear. Further studies are warranted to assess which specific HRVB protocols lead to greater results for treating depressive symptoms among adults.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Authors thank William Russell-Edu for the editing of the English language.

Author contributions

S.F.M.P. and C.M. conceived the initial idea for the study, performed the systematic literature search and systematized the data; S.F.M.P. and D.G. analysed and discussed the data, while D.M. supervised the systematic literature search, the analyses and contributed to the methodology. All the aforementioned authors wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. K.M. revised the initial draft, discussed the clinical implications of the study, and supervised the entire process. G.P. supervised and revised all the steps of the manuscript and the drafts. All the authors discussed every step of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-86149-7.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders Global Health Estimates. WHO; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hasin DS, Sarvet AL, Meyers JL, Saha TD, Ruan WJ, Stohl M, Grant BF. Epidemiology of adult DSM-5 major depressive disorder and its specifiers in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(4):336–346. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moussavi S, Chatterji S, Verdes E, Tandon A, Patel V, Ustun B. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: Results from the World Health Surveys. Lancet. 2007;370(9590):851–858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61415-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Penninx BWJH, Milaneschi Y, Lamers F, Vogelzangs N. Understanding the somatic consequences of depression: Biological mechanisms and the role of depression symptom profile. BMC Med. 2013 doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch. Intern. Med. 2000;160(14):2101–2107. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knol MJ, Twisk JWR, Beekman ATF, Heine RJ, Snoek FJ, Pouwer F. Depression as a risk factor for the onset of type 2 diabetes mellitus. A meta-analysis. Diabetologia. 2006;49(5):837–845. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0159-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Green RC, Cupples LA, Kurz A, Auerbach S, Go R, Sadovnick D, Duara R, Kukull WA, Chui H, Edeki T, Griffith PA, Friedland RP, Bachman D, Farrer L. Depression as a risk factor for Alzheimer disease: The MIRAGE study. Arch. Neurol. 2003;60(5):753–759. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.5.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Correll CU, Solmi M, Veronese N, Bortolato B, Rosson S, Santonastaso P, Thapa-Chhetri N, Fornaro M, Gallicchio D, Collantoni E, Pigato G, Favaro A, Monaco F, Kohler C, Vancampfort D, Ward PB, Gaughran F, Carvalho AF, Stubbs B. Prevalence, incidence and mortality from cardiovascular disease in patients with pooled and specific severe mental illness: A large-scale meta-analysis of 3,211,768 patients and 113,383,368 controls. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(2):163–180. doi: 10.1002/wps.20420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lett HS, Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, Sherwoob A, Strauman T, Robins C, Newman MF. Depression as a risk factor for coronary artery disease: Evidence, mechanisms, and treatment. Psychosom. Med. 2004;66:305–315. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000126207.43307.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang H-J, Kim S-Y, Bae K-Y, Kim S-W, Shin I-S, Yoon J-S, Kim J-M. Comorbidity of depression with physical disorders: Research and clinical implications. Chonnam Med. J. 2015;51(1):8–18. doi: 10.4068/cmj.2015.51.1.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roth DL, Haley WE, Sheehan OC, Liu C, Clay OJ, Rhodes JD, Judd SE, Dhamoon M. Depressive symptoms after ischemic stroke: Population-based comparisons of patients and caregivers with matched controls. Stroke. 2020;51(1):54–60. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.027039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davidson KW, Alcántara C, Miller GE. Selected psychological comorbidities in coronary heart disease: Challenges and grand opportunities. Am. Psychol. 2018;73(8):1019–1030. doi: 10.1037/amp0000239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kvam S, Kleppe CL, Nordhus IH, Hovland A. Exercise as a treatment for depression: A meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2016;202:67–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.03.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li JM, Zhang Y, Su WJ, Liu LL, Gong H, Peng W, Jiang CL. Cognitive behavioral therapy for treatment-resistant depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2018;268:243–250. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gordon BR, McDowell CP, Hallgren M, Meyer JD, Lyons M, Herring MP. Association of efficacy of resistance exercise training with depressive symptoms meta-analysis and meta-regression: Analysis of randomized clinical trials. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(6):566–576. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.0572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Möller H, Henkel V. What are the Most Effective Diagnostic and Therapeutic Strategies for the Management of Depression in Specialist Care? WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeRubeis RJ, Siegle GJ, Hollon SD. Cognitive therapy versus medication for depression: Treatment outcomes and neural mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2008;9(10):788–796. doi: 10.1038/nrn2345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hagen R, Hjemdal O, Solem S, Kennair LEO, Nordahl HM, Fisher P, Wells A. Metacognitive therapy for depression in adults: A waiting list randomized controlled trial with six months follow-up. Front. Psychol. 2017;8:31. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Donker T, Batterham PJ, Warmerdam L, Bennett K, Bennett A, Cuijpers P, Griffiths KM, Christensen H. Predictors and moderators of response to internet-delivered interpersonal psychotherapy and cognitive behavior therapy for depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2013;151(1):343–351. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seligman L, Reichenberg L. Theories of Counseling and Psychotherapy: Systems, Strategies, and Skills. Pearson Higher Education; 2014. pp. 354–356. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin HP, Lin HY, Lin WL, Huang ACW. Effects of stress, depression, and their interaction on heart rate, skin conductance, finger temperature, and respiratory rate: Sympathetic-parasympathetic hypothesis of stress and depression. J. Clin. Psychol. 2011;67(10):1080–1091. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kemp AH, Quintana DS, Felmingham KL, Matthews S, Jelinek HF. Depression, comorbid anxiety disorders, and heart rate variability in physically healthy, unmedicated patients: Implications for cardiovascular risk. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(2):e30777. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sgoifo A, Carnevali L, Pico Alfonso MDLA, Amore M. Autonomic dysfunction and heart rate variability in depression. Stress. 2015;18(3):343–352. doi: 10.3109/10253890.2015.1045868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown L, Karmakar C, Gray R, Jindal R, Lim T, Bryant C. Heart rate variability alterations in late life depression: A meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2018;235:456–466. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.04.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kidwell M, Ellenbroek BA. Heart and soul: Heart rate variability and major depression. Behav. Pharmacol. 2018;29(2):152–164. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0000000000000387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caldwell YT, Steffen PR. Adding HRV biofeedback to psychotherapy increases heart rate variability and improves the treatment of major depressive disorder. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2017;2018(131):96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2018.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hartmann R, Schmidt FM, Sander C, Hegerl U. Heart rate variability as indicator of clinical state in depression. Front. Psychiatry. 2019;9:735. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kemp AH, Quintana DS, Gray MA, Felmingham KL, Brown K, Gatt JM. Impact of depression and antidepressant treatment on heart rate variability: A review and meta-analysis. Biol. Psychiatry. 2010;67(11):1067–1074. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dell’Acqua C, Dal Bò E, Messerotti Benvenuti S, Palomba D. Reduced heart rate variability is associated with vulnerability to depression. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2020;1:100006. doi: 10.1016/j.jadr.2020.100006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lehrer PM, Vaschillo E, Vaschillo B. Resonant frequency biofeedback training to increase cardiac variability: Rationale and manual for training. Appl. Psychophysiol. Biofeedback. 2000;25:177–191. doi: 10.1023/A:1009554825745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lehrer PM, Gevirtz R. Heart rate variability biofeedback: How and why does it work? Front. Psychol. 2014;5:756. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin IM, Fan SY, Yen CF, Yeh YC, Tang TC, Huang MF, Liu TL, Wang PW, Lin HC, Tsai HY, Tsai YC. Heart rate variability biofeedback increased autonomic activation and improved symptoms of depression and insomnia among patients with major depression disorder. Clin. Psychopharmacol. Neurosci. 2019;17(2):222. doi: 10.9758/cpn.2019.17.2.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karavidas M. Heart Rate Variability Biofeedback for Major Depression. Biofeedback; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jimenez Morgan S, Molina Mora JA. Effect of heart rate variability biofeedback on sport performance, a systematic review. Appl. Psychophysiol. 2017;42(3):235–245. doi: 10.1007/s10484-017-9364-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu LC, Lin IM, Fan SY, Chien CL, Lin TH. One-year cardiovascular prognosis of the randomized, controlled, short-term heart rate variability biofeedback among patients with coronary artery disease. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2018;25(3):271–282. doi: 10.1007/s12529-017-9707-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Criswell SR, Sherman R, Krippner S. Cognitive behavioral therapy with heart rate variability biofeedback for adults with persistent noncombat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Perm. J. 2018 doi: 10.7812/TPP/17-207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Drury RL, Porges SW, Thayer JF, Ginsberg J. Editorial: Heart rate variability, health and well-being: A systems perspective. Front. Public Health. 2019;7:323. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yetwin A, Marks K, Bell T, Gold J. Heart rate variability biofeedback therapy for children and adolescents with chronic pain. J. Pain. 2012;13(4):S93. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.01.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goessl VC, Curtiss JE, Hofmann SG. The effect of heart rate variability biofeedback training on stress and anxiety: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 2017;47(15):2578–2586. doi: 10.1017/S0033291717001003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lehrer P, Kaur K, Sharma A, Shah K, Huseby R, Bhavsar J, Zhang Y. Heart rate variability biofeedback improves emotional and physical health and performance: A systematic review and meta analysis. Appl. Psychophysiol. 2020;45:109–129. doi: 10.1007/s10484-020-09466-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Climov D, Lysy C, Berteau S, Dutrannois J, Dereppe H, Brohet C, Melin J. Biofeedback on heart rate variability in cardiac rehabilitation: Practical feasibility and psycho-physiological effects. Acta Cardiol. 2014;69(3):299–307. doi: 10.1080/ac.69.3.3027833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meyer PW, Friederich HC, Zastrow A. Breathe to ease—Respiratory biofeedback to improve heart rate variability and coping with stress in obese patients: A pilot study. Ment. Health Prev. 2018;11:41–46. doi: 10.1016/j.mhp.2018.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chang WL, Lee JT, Li CR, Davis AHT, Yang CC, Chen YJ. Effects of heart rate variability biofeedback in patients with acute ischemic stroke: A randomized controlled trial. Biol. Res. Nurs. 2020;22(1):34–44. doi: 10.1177/1099800419881210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van der Zwan JE, Huizink AC, Lehrer PM, Koot HM, de Vente W. The effect of heart rate variability biofeedback training on mental health of pregnant and non-pregnant women: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2019 doi: 10.3390/ijerph16061051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Penzlin AI, Siepmann T, Illigens BMW, Weidner K, Siepmann M. Heart rate variability biofeedback in patients with alcohol dependence: A randomized controlled study. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2015;11:2619–2627. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S84798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Swanson KS, Gevirtz RN, Brown M, Spira J, Guarneri E, Stoletniy L. The effect of biofeedback on function in patients with heart failure. Appl. Psychophysiol. 2009;34(2):71–91. doi: 10.1007/s10484-009-9077-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van der Zwan JE, de Vente W, Huizink AC, Bogels SM, de Bruin EI. Physical activity, mindfulness meditation, or heart rate variability biofeedback for stress reduction: A randomized controlled trial. Appl. Psychophysiol. 2015;40(4):257–268. doi: 10.1007/s10484-015-9293-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gruzelier JH, Thompson T, Redding E, Brandt R, Steffert T. Application of alpha/theta neurofeedback and heart rate variability training to young contemporary dancers: State anxiety and creativity. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2014;93(1):105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Windthorst P, Mazurak N, Kuske M, Hipp A, Giel KE, Enck P, Niess A, Zipfel S, Teufel M. Heart rate variability biofeedback therapy and graded exercise training in management of chronic fatigue syndrome: An exploratory pilot study. J. Psychosom. Res. 2017;93:6–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hallman DM, Olsson EMG, Von Scheéle B, Melin L, Lyskov E. Effects of heart rate variability biofeedback in subjects with stress-related chronic neck pain: A pilot study. Appl. Psychophysiol. 2011;36(2):71–80. doi: 10.1007/s10484-011-9147-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Amjadian M, Bahrami Ehsan H, Saboni K, Vahedi S, Rostami R, Roshani D. A pilot randomized controlled trial to assess the effect of Islamic spiritual intervention and of breathing technique with heart rate variability feedback on anxiety, depression and psycho-physiologic coherence in patients after coronary artery bypass surgery. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry. 2020;19(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12991-020-00296-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brinkmann AE, Press SA, Helmert E, Hautzinger M, Khazan I, Vagedes J. Comparing effectiveness of HRV-biofeedback and mindfulness for workplace stress reduction: A randomized controlled trial. Appl. Psychophysiol. 2020;45:307. doi: 10.1007/s10484-020-09477-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tatschl JM, Hochfellner SM, Schwerdtfeger AR. Implementing mobile HRV biofeedback as adjunctive therapy during inpatient psychiatric rehabilitation facilitates recovery of depressive symptoms and enhances autonomic functioning short-term: A 1-year pre–post-intervention follow-up pilot study. Front. Neurosci. 2020;14:1–14. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.00738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Burch JB, Ginsberg JP, McLain AC, Franco R, Stokes S, Susko K, Hendry W, Crowley E, Christ A, Hanna J, Anderson A, Hébert JR, O’Rourke MA. Symptom management among cancer survivors: Randomized pilot intervention trial of heart rate variability biofeedback. Appl. Psychophysiol. 2020;45(2):99–108. doi: 10.1007/s10484-020-09462-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. Introduction to Meta-Analysis. Wiley; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Del Re, A. C. compute.es: Compute Effect Sizes. R package version 0.2–2. http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/compute.es. Accessed 5 Sept 2020 (2013).

- 57.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, Savović J, Schulz KF, Weeks L, Sterne JAC. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Br. Med. J. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Br. Med. J. 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lin L, Chu H. Quantifying publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2018;74(3):785–794. doi: 10.1111/biom.12817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor. J. Stat. Softw. 2010;36(3):1–48. doi: 10.18637/jss.v036.i03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. TX Psychol Corp; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lovibond SH, Lovibond PF. Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales. Psychology Foundation of Australia; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: The PHQ primary care study. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1999;282(18):1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1977;1:385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Read JR, Sharpe L, Modini M, Dear BF. Multimorbidity and depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2017;15(221):36–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cuijpers P, Berking M, Andersson G, Quigley L, Kleiboer A, Dobson KS. A meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioural therapy for adult depression, alone and in comparison with other treatments. Can. J. Psychiatry. 2013;58(7):376–385. doi: 10.1177/070674371305800702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jacobson NC, Newman MG. Anxiety and depression as bidirectional risk factors for one another: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol. Bull. 2017;143(11):1155–1200. doi: 10.1037/bul0000111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mitchell AJ, Chan M, Bhatti H, Halton M, Grassi L, Johansen C, Meader N. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder in oncological, haematological, and palliative-care settings: A meta-analysis of 94 interview-based studies. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(2):160–174. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70002-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mazzocco K, Masiero M, Carriero MC, Pravettoni G. The role of emotions in cancer patients’ decision-making. Ecancermedicalscience. 2019 doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2019.914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pravettoni G, Gorini A. A P5 cancer medicine approach: Why personalized medicine cannot ignore psychology. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2011;17(4):594–596. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2011.01709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kondylakis H, Kazantzaki E, Koumakis L, Genitsaridi I, Marias K, Gorini A, Mazzocco K, Pravettoni G, Burke D, McVie G, Tsiknakis M. Development of interactive empowerment services in support of personalised medicine. Ecancermedicalscience. 2014 doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2014.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Salvadore G, Nugent AC, Lemaitre H, Luckenbaugh DA, Tinsley R, Cannon DM, Neumeister A, Zarate CA, Drevets WC. Prefrontal cortical abnormalities in currently depressed versus currently remitted patients with major depressive disorder. Neuroimage. 2011;54(4):2643–2651. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.