Abstract

Previous work from our group showed that certain engineered missense mutations to the α-synuclein (αS) KTKEGV repeat motifs abrogate the protein’s ability to form native multimers. The resultant excess monomers accumulate in lipid membrane-rich inclusions associated with neurotoxicity exceeding that of natural familial PD mutants such as E46K. We presented an initial characterization of the lipid-rich inclusions and found similarities to the αS- and vesicle-rich inclusions that form in baker’s yeast when αS is expressed. We also discussed, with some caution, a possible role of membrane-rich inclusions as precursors to filamentous Lewy bodies, the widely accepted hallmark pathology of Parkinson’s disease and other synucleinopathies. In the meantime, advances in the microscopic characterization of Lewy bodies have highlighted the presence of crowded organelles and lipid membranes in addition to αS accumulation. This prompted us to revisit the αS inclusions caused by our repeat motif variants in neuroblastoma cells. In addition to our previous characterization, we found that these inclusions can often be seen by brightfield microscopy, overlap with endogenous vesicle markers in immunofluorescence experiments, stain positive for lipid dyes and can be found to be closely associated with mitochondria. We also observed abnormal tubulation of membranes, which was subtle in inducible lines and pronounced in cells that transiently expressed high amounts of the highly disruptive KTKEGV motif mutant “KLKEGV”. Membrane tubulation had been reported before as an αS activity in reductionist systems. Our in-cellulo demonstration now suggests that this mechanism could possibly be a relevant aspect of aberrant αS behavior in cells.

Introduction

α-Synuclein (αS) is a 140 amino-acid protein highly expressed in neurons. It is implicated in several ‘synucleinopathies’ such as Parkinson’s disease (PD) and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB). These brain diseases are characterized by αS-rich lesions in somata (Lewy bodies) or neurites (Lewy neurites). Physiologically, αS is a protein that exhibits a complex dynamic behavior inside of live cells (reviewed by Yeboah et al., 2019). Recombinant αS in solution has been characterized as unfolded and monomeric (Weinreb et al., 1996). However, αS binding to curved membranes is also well-documented in reductionist systems and mediated by the formation of transient αS amphipathic helices (Davidson et al., 1998; Chandra et al., 2003; Jao et al., 2008). It seems that αS indeed exists in both soluble and membrane-associated forms in live cells, but the relative amounts are not easy to determine (Fortin et al., 2010) and may be cell type- and context-specific. Trans and cis factors have been shown to influence αS-membrane interactions: high membrane curvature, lipid unsaturation, and negative charges of lipid headgroup all seem to promote αS-membrane binding in trans (Nuscher et al., 2004). As far as cis factors are concerned, the fPD-linked αS variants A30P and G51D were shown to be enriched in the cytosol (Fares et al., 2014) while the E46K variant accumulates at membranes (Rovere et al., 2019). To complicate things further, a natively multimeric and soluble form of αS has been described in the soluble phase of cells (Bartels et al., 2011), which is likely to be in a dynamic equilibrium with monomers at the membrane and in the cytoplasm (Dettmer et al., 2013). Transient binding of monomers to membranes may be a prerequisite for the formation of folded multimers at the membrane that in turn become soluble (Rovere et al., 2018). In addition to vesicle membranes, lipid droplets (LDs) have been suggested to target organelles of αS inside of cells (Cole et al., 2002), consistent with a certain similarity between αS and the perilipins, a class of LD-binding proteins (Londos et al., 1999).

αS helix formation at membranes is promoted by hydrophobic amino acids interacting with the fatty acyl chains of membrane lipids and by lysine residues interacting with negatively charged phospholipid head groups (reviewed by Dettmer, 2018). The key structural element underlying this interaction is an 11-aa repeat motif with the core consensus sequence KTKEGV, which appears imperfectly 6–9 times in the first two-thirds of the protein (Maroteaux and Scheller, 1991). In previous work, we have shown that the αS-membrane interaction can be amplified by strategic point mutations in αS. It had been demonstrated that the additional lysine in fPD-linked αS E46K can stabilize the monomeric, membrane-associated amphipathic helix of αS by creating an additional electrostatic interaction with negatively charged lipid headgroups (Perlmutter et al., 2009). We therefore first developed an ‘amplified’ model of E46K by inserting analogous mutations into the immediately adjacent KTKEGV repeat motifs (Dettmer et al., 2015a). The resulting αS ‘3K’ (E35K+E46K+E61K) was indeed largely monomeric and enriched in membrane fractions. Second, we stabilized monomeric helical αS by strengthening the hydrophobic interaction between αS and fatty acid tails. One prominent such engineered mutation was αS ‘KLK’, in which we changed the core motif from KTKEGV to KLKEGV in 6 repeats (Dettmer et al., 2015b). This variant, too, was characterized as largely monomeric and membrane-bound, consistent with the stabilization of the αS amphipathic helix.

In a mouse model, pan-neuronal expression of αS 3K causes an L-DOPA-responsive motor phenotype closely resembling PD (Nuber et al., 2018). In cell culture, both αS 3K and KLK variants cause multiple biochemical and cytopathological phenotypes resembling features of PD, most importantly lipid/membrane-rich αS aggregation (Dettmer et al., 2017). Because we did not observe apparent fibrillar αS in the αS-rich aggregates in EM images, we discussed the relevance of the inclusions for LB formation with caution (Dettmer et al., 2017). Our observations were in agreement with certain earlier characterizations of LBs (Forno and Norville, 1976; Nishimura et al., 1994), but in disagreement with the classical view of the overwhelmingly fibrillar nature of αS in LBs (Spillantini et al., 1998). We speculated that the inclusions in our cells lines may represent what neuropathologists have referred to as pale bodies (Gibb et al., 1991); instead of being “Lewy-like” themselves, the lesions could represent precursors to classical fibrillar LBs. This, we reasoned, would be consistent with the idea of αS membrane interaction being a nucleation event in the aggregation of the αS protein (Galvagnion et al., 2015).

However, since then, unexpected recent data have suggested that Lewy-type inclusions indeed may be less filamentous than previously thought and consist of crowded organelles and lipid membranes to a considerable extent (Shahmoradian et al., 2019). These striking observations prompted us to revisit and characterize in more detail the cellular phenotypes that are evoked by our KTKEGV motif mutants. We provide novel insight into the co-localization of our ‘artificial’ αS lesions with lipid LDs and endogenous cellular vesicle markers as well as their proximity to mitochondria. Importantly, we include EM data on transiently transfected neuroblastoma cells that severely suffered from the expressed αS variants and show dramatic phenotypes, which are in general agreement with the LB characterization by Shahmoradian et al.: pronounced focal accumulation of αS amidst a ‘medley’ of lipid-rich organelles such as vesicles, LDs, and mitochondria. A special aspect of the lipid-rich lesions that we observed was an apparent tubulation activity of αS on vesicular membranes.

Results

αS ‘3K’ inclusions are visible by brightfield microscopy and overlap with lipid dye staining.

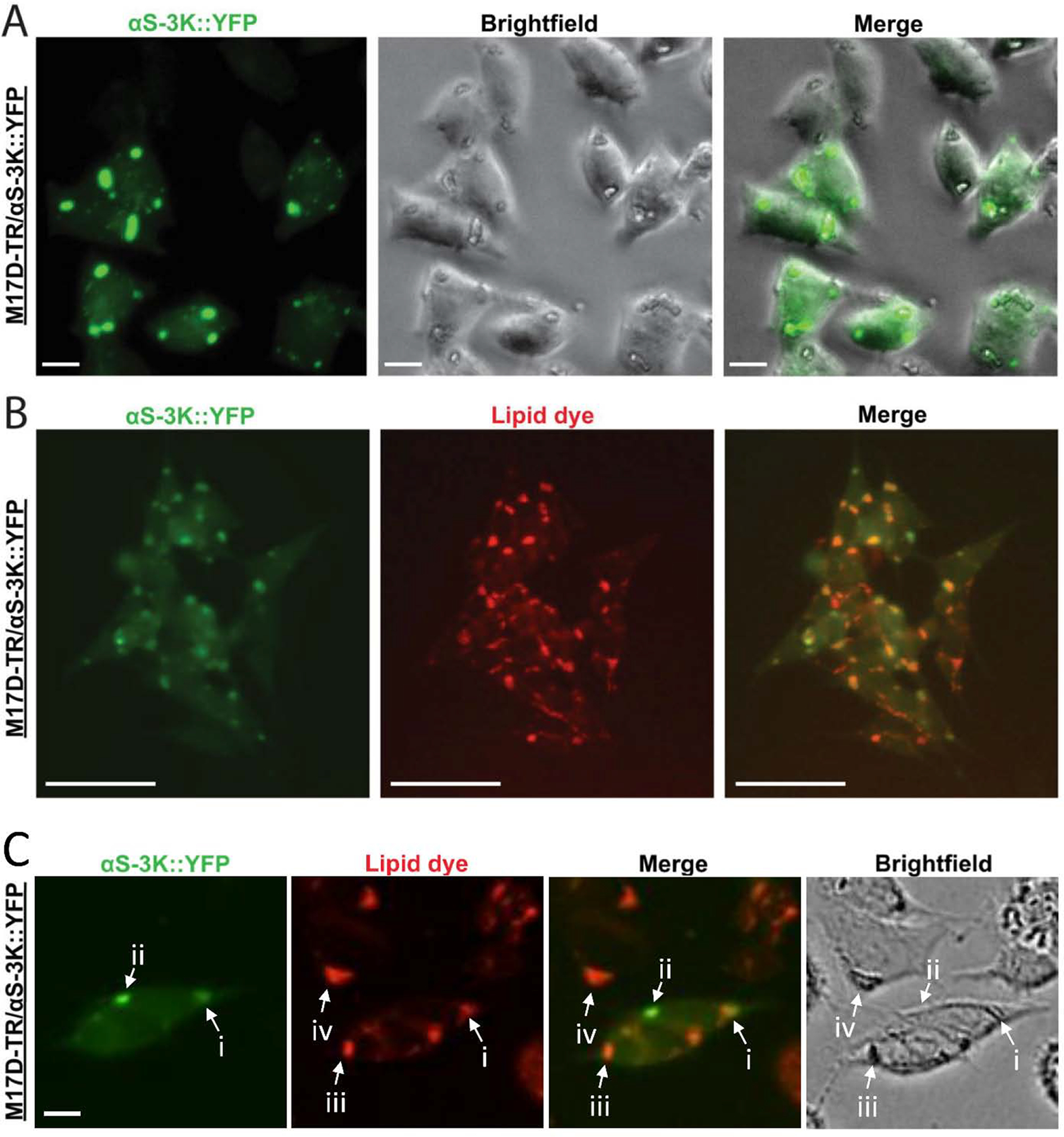

In previous work, we had introduced the ‘amplified E46K’ αS variant ‘3K’ (E35K+E46K+E61K) and reported that this mutant disrupts normal αS multimerization, accumulates at membranes, and exerts frank toxicity (Dettmer et al., 2015a). When fused to a YFP-tag, the αS-rich inclusions can easily be visualized in live cells: instead of the diffuse, ubiquitous staining of wt αS, strong focal accumulation can be observed for 3K::YFP (Dettmer et al., 2015a). The co-expression of marker proteins and EM analysis demonstrated that the αS-rich inclusions are also rich in vesicular membranes (Dettmer et al., 2017). While our EM images did not indicate the presence of large fibrillar protein aggregates, another frequent inclusion component were vacuole-like structures that we suggested to be LDs (Dettmer et al., 2017). To study this possible interaction between LDs and αS further, we compared YFP and brightfield images in inducible M17D neuroblastoma cells expressing αS-3K::YFP (Fig. 1A). We observed an overlap of the YFP-positive αS-3K foci (Fig. 1A, green channel) with distinct round or oval cellular structures visible by brightfield microscopy, which would be consistent with the presence of LDs in the inclusions (Fig. 1A, brightfield channel). We next compared the YFP signal (Fig. 1B, green channel) with a lipid dye that fluoresces in red (Fig. 1B, red channel), and we noticed a striking overlap between the two signals. Interestingly, however, not all droplet-like structures overlapped with inclusions, and cells without visible inclusions contained similar LD structures (Fig. 1C). These observations were consistent with αS 3K interacting with LDs, without necessarily inducing them or grossly changing their appearance. Similarly, the fact that some αS-rich inclusions did not overlap with LD-like structures indicated that LDs are not strictly required for αS inclusion formation in this model (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1. αS ‘3K’ (E35K+E46K+E61K) YFP+ inclusions overlap with LD-like structures in live cells.

A, 17D-TR/αS-3K::YFP neuroblastoma cells were induced to express mutant αS-3K::YFP for 48 h. Live cells underwent bright-field and fluorescence microscopy. αS-positive inclusions were detected in the green channel (left panel, the arrow points at an example inclusion). The cells contained round/oval structures that were visible in the brightfield channel (middle panel, the arrow points at an example structure). A merge image of YFP and brightfield channel demonstrates pronounced, but not complete, overlap between YFP+ inclusions and round/oval cellular structures (right panel, the arrow points at an example of pronounced overlap). B, αS-3K::YFP signal strongly colocalizes with a lipid dye (HCS LipidTOX™ deep red neutral lipid dye) within round/oval cellular inclusions. Note that many but not all YFP+ inclusions overlap with lipid dye staining and vice versa. Incucyte-based imaging. Scalebars: (A) 20 μm, (B) 50 μm. C, Examples of αS-rich inclusions that overlap with LDs (i), αS-rich inclusions that do not overlap with LDs (ii), LDs that do not overlap with αS-rich inclusions despite αS-3K::YFP expression in the same cell (iii), and LDs in non-αS-expressing cells (iv).

Membrane-enriched αS 3K accumulates together with endogenous vesicle marker proteins.

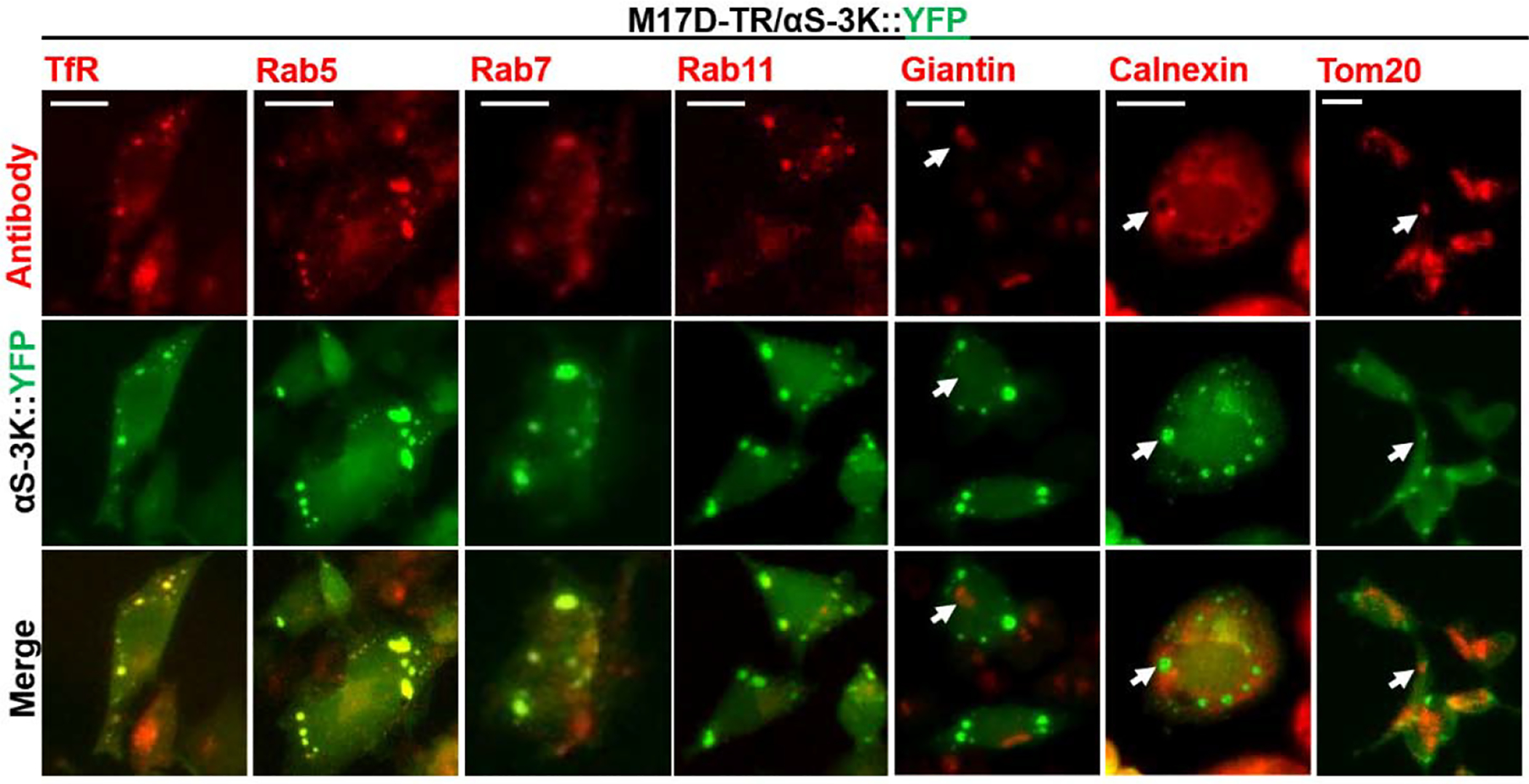

While LDs might be a frequent but not requisite component of the observed inclusions, we have not yet observed the focal accumulation of αS 3K (or other, engineered membrane-enriched αS variants) in the absence of accumulating vesicles. We have previously demonstrated the overlap of αS-3K::YFP with co-expressed RFP-tagged marker proteins: transferrin receptor, Rab5, Rab7, and Rab11 (all endosomal markers) as well as SitN5 (Golgi) and LAMP1 (lysosomal). Conversely, we did not observe overlap with non-vesicular membranes such as ER (Calnexin was tested) or mitochondria (Tom20) (Dettmer et al., 2017). Because co-localization data could have been confounded by overexpression artifacts, we now sought to confirm the overlap with endogenous proteins. We induced αS-3K::YFP expression in our neuroblastoma cells for 48 h and subjected fixed cells to immunofluorescence analysis. We saw strong overlap of the YFP signals with the endosomal marker proteins transferrin receptor, Rab5, Rab7, and Rab11 (Fig. 2). However, there was little overlap with the Golgi marker Giantin (Fig. 2, Giantin, the arrow indicates a Giantin-rich structure resembling a Golgi apparatus). Analogous to our previous work, we did not observe overlap between inclusions and ER; in fact, ER appeared excluded from the inclusions (Fig. 2, Calnexin, the arrow points at a region that is devoid of ER, but enriched in αS::YFP signal). Similarly, mitochondrial membranes were absent from the inclusions themselves, but we occasionally observed a possible association between mitochondria and inclusions (Fig 2, Tom20, the arrow indicates Tom20-enrichment and αS::YFP accumulation in close proximity). In summary, we confirmed the presence of vesicles as key components of αS-3K inclusions. Generally in line with previous work (Dettmer et al., 2017), in which we performed co-expression of RFP-tagged marker proteins, we highlight the overlap of the inclusions with endocytic vesicles, as evidenced by a strong overlap with TfR, Rab5, Rab7, and Rab11.

Figure 2. Endogenous vesicular markers stain αS-3K inclusions in αS-3K::YFP inducible cells.

Antibodies to Transferrin receptor (TfR), early endosomal Rab5, late endosomal Rab7, recycling endosomal Rab11, Golgi-localized Giantin, mitochondrial Tom20, and ER-localized Calnexin were utilized to understand the membrane contents of αS-positive inclusions. Vesicular markers TfR, Rab5, Rab7, and Rab11 colocalize with membrane-enriched inclusions, whereas Giantin, Tom20, and Calnexin largely exclude the inclusions. Scalebar: 20 μm.

αS-mediated membrane tubulation.

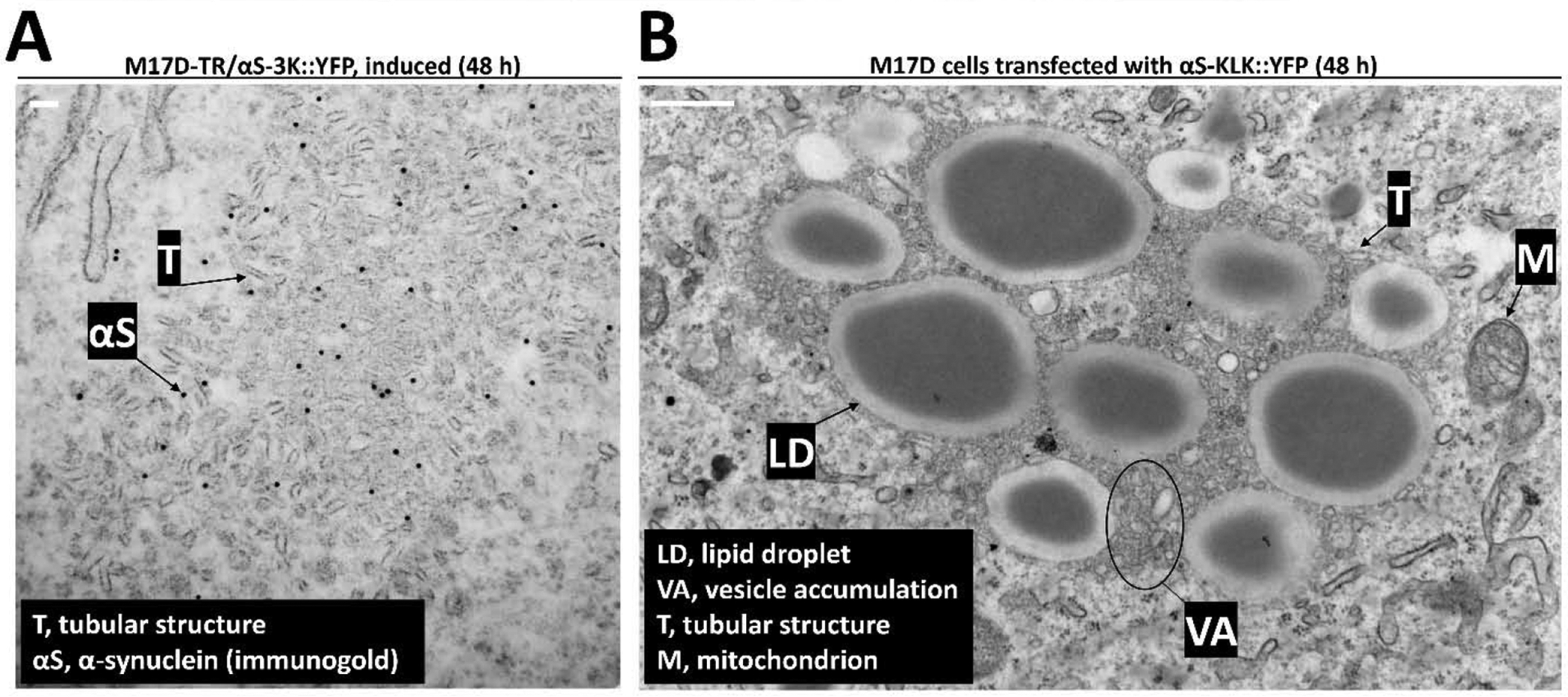

Our data thus far are consistent with αS-3K inclusions being a ‘medley’ of αS, LDs, and vesicular, but not ‘flat’, membranes such as ER. This notion is supported by our previous immunogold-EM characterization of αS-3K::YFP expressing cells (Fig. 2 in Dettmer et al, 2015a). In addition to round vesicles and LDs, we have observed short tubular structures in the inclusions. This is illustrated in Fig. 3A within induced 3K::YFP-expressing neuroblastoma cells that were subjected to immunogold EM: a variety of short tubular structures is seen, and anti-αS immunogold-EM confirms the vesicle and tubule medley as rich in αS (Fig. 3A, ‘T’ points at a pronounced tubular structure). Similar to previous work, we did not see evidence for clear-cut fibrillar αS either in or associated with the inclusions, indicating that there may be only small aggregates or that αS in the inclusions is not aggregated at all. Similar to αS 3K, we have seen such membranous, fibril-free inclusions in the case of the αS ‘KLK’ mutation, which changes the core motif of the characteristic αS 11-amino acid repeat from KTKEGV to KLKEGV, leading to enhanced membrane interaction similar to ‘3K’ (Dettmer et al., 2015b). Fig. 3B displays a large, vesicle- (‘VA’, vesicle accumulation) and LD-rich (‘LD’) αS-KLK inclusion that also contains tubular structures (‘T’) and mitochondria (‘M’). Importantly, such inclusions were never observed in control-transfected cells (empty vector; Suppl. Fig. 1).

Figure 3. In inducible cells membrane-enriched αS variants ‘3K’ and ‘KLK’ cause inclusions that are rich in vesicles, tubular structures, and LDs by electron microscopy.

A, Electron micrograph of inducible αS-3K::YFP-expressing cell exhibits a membranous inclusion consisting mainly of tubular structures (T). Immunogold labeling with the C20 antibody for αS (black arrow) shows punctate αS 3K decorating the membrane-enriched inclusion. Scale bar: 100 nm. B, Electron micrograph of inducible αS-KLK::YFP-expressing cell also shows the inclusion being composed of vesicle accumulation (VA), tubular structures (T), and lipid droplets (LD). In addition, there is a mitochondrion (M) in the inclusion periphery. Scale bar: 500 nm.

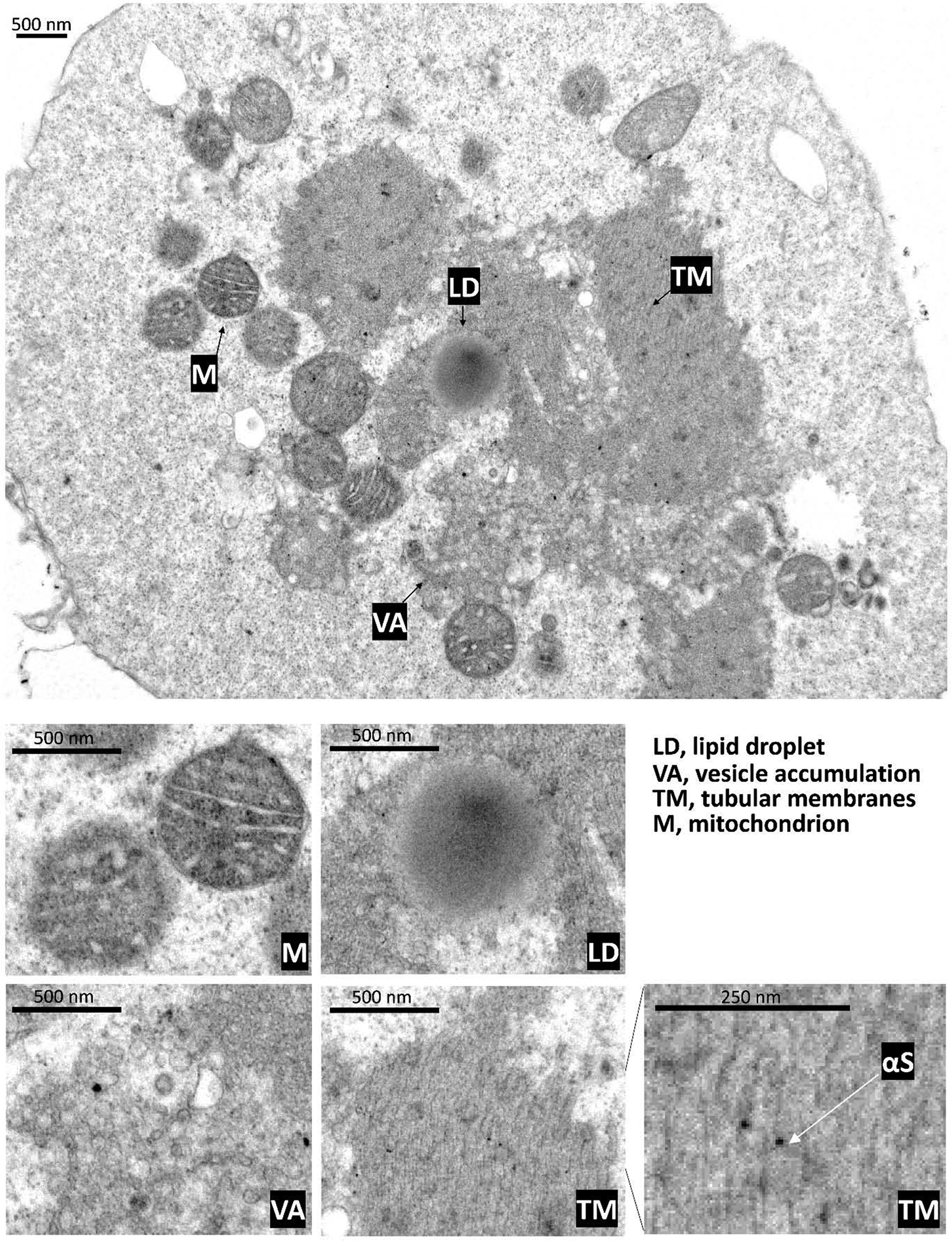

We have established in previous work that αS KLK causes strong phenotypes and even leads to pronounced cellular death, as evidenced by PARP cleavage, trypan blue inclusion, and adenylate-kinase release assays (Dettmer et al., 2015b). Thus, we reasoned that EM analysis of KLK-expressing, highly stressed cells might give us hints about how αS actually kills cells under disease conditions. Having observed before that transient transfection results in highest expression levels and pronounced toxicity, we decided to transiently transfect neuroblastoma cells with αS KLK, resulting in cultures that appeared ‘sick’ under the microscope (many rounded and floating cells were visible). We then subjected such cultures to immunogold EM analysis (Fig. 4). We again found large, abnormal, membrane/lipid-rich inclusions in such cells. The inclusion shown was associated with round-looking mitochondria (Fig. 4, ‘M’ in main image and zoom-in) and appeared to be centered around a LD (‘LD’ in main image and zoom-in). We also observed pronounced vesicle accumulation (‘VA’ in main image and zoom-in), but most strikingly the cell contained large areas of what appeared to be stacked tubular membranes (‘TM’ in main image and zoom-in 1 and 2). Immunogold-labeling identified αS to be associated with the tubular stacks, potentially localized in between two apparent tubular subunits (‘TM’ zoom-in images). Thus, it seemed that compared to inducible cells, which only contained smaller tubular structures associated with membranous inclusions (Fig. 3A), the acutely transfected and highly challenged cells were characterized by what appeared to be massive membrane tubulation.

Fig. 4. In transfected cells membrane-enriched αS variant ‘KLK’ cause inclusions that are rich in vesicles, lipid droplets, and massive stacked tubular structures by electron microscopy.

A transfected αS-KLK::YFP cell demonstrates by electron micrograph inclusion components of vesicle accumulation (VA), lipid droplets (LD), and peripheral mitochondria (M). Rather than single tubular structures, an expanse of tubular membranes (TM) are observed in these inclusions. These features are shown with zoomed-in images for, mitochondria (M), lipid droplet (LD), vesicle accumulation (VA), and tubular membranes (TM). Immunogold detection suggests that αS is associated with the tubular membranes. Scalebars as indicated.

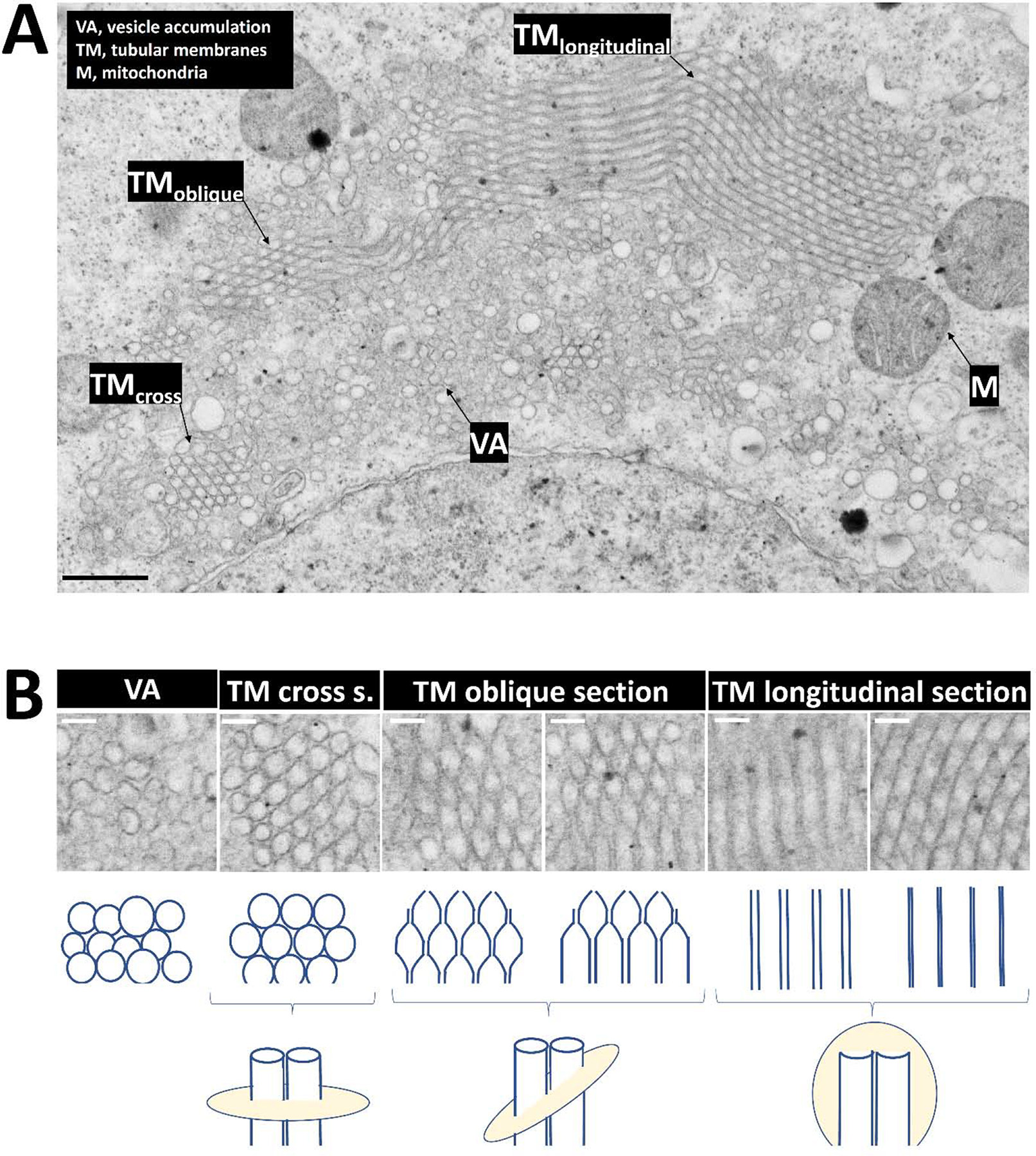

This raised the question about the relationship between vesicle accumulation and membrane tubulation, and we analyzed a larger number of EM images for a better understanding. EM analysis cannot answer questions about the kinetics of vesicle aggregation and tubular stack formation. However, a larger number of cells in the population contained vesicular accumulation and (stacked) tubular structures in close proximity, exemplified in Fig. 5: the concurrence of these structures would be consistent with a scenario, in which αS first leads to vesicle accumulation ‘VA’ in Figs. 5A,B), followed by clustered vesicles undergoing further remodeling and potentially membrane fusion events (transition from clustered vesicles to tubular membranes), eventually resulting in (stacked) tubular membranes (‘TM’ in Fig. 5A,B). These phenotypes suggest a remarkable ability of αS to remodel membranes and to cause lipid-rich inclusions, often associated with mitochondria (‘M’ in Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5. In transfected cells membrane-enriched αS variant ‘KLK’ causes tubular structures that may result from remodeling of vesicle membranes.

A, A transfected αS-KLK::YFP cell demonstrates by electron micrograph similar inclusion components of vesicle accumulation, LDs, and peripheral mitochondria. An expanse of tubular membranes (TM) is observed with variations in its appearance depending on the respective section (cross, oblique, longitudinal), as indicated. Scalebar: 500 nm. B, Zoom-in images of vesicle accumulation and of stacked tubular membranes (various sections as indicated, see Fig. 5A and main text for more details). Scalebars: 100 nm.

Discussion

Revisiting and expanding upon an aS-driven cell phenotype.

In earlier work, we engineered certain KTKEGV repeat-motif mutations to abolish the abundant ~60 kDa tetrameric assemblies (αS60) that are normally detected upon intact-cell crosslinking of wt αS (Dettmer et al., 2015a, 2015b). We reported that the mutant, monomeric αS proteins were relatively toxic, largely PBS-insoluble, and detected in round cytoplasmic inclusions. In a follow-up study, we focused on two KTKEGV repeat-motif mutants to characterize the striking inclusions that they form: a) αS 3K (E35K+E46K+E61K), which is an amplification of the fPD-linked E46K into the two adjacent KTKEGV motifs; and b) αS ‘KLK’, which is an engineered mutant that changes the KTKEGV core motif to KLKEGV in 6 repeats (Dettmer et al., 2017). By studying both variants in several neuronal systems, we showed that the round cytoplasmic inclusions arising from these KTKEGV motif mutations are comprised of clusters of vesicles and small tubules intimately associated with the focal αS accumulation (Dettmer et al., 2017). In the cytoplasm of human neural cells, the dense clusters of vesicles that developed upon expression of αS 3K or KLK were identified by co-expression of RFP-tagged marker proteins to be derived from diverse vesicular membranes (endocytic, lysosomal, Golgi), but no evidence for interactions with non-vesicle membranes such as mitochondria and ER were found. Since then, new work by Shahmoradian and colleagues has suggested that Lewy-type inclusions may indeed be less filamentous than previously thought and may largely consist of crowded organelles and lipid membranes (Shahmoradian et al., 2019). This prompted us to revisit the cellular phenotypes that are evoked by our KTKEGV motif mutants and characterize them in more detail. An important observation in this context was that αS-3K::YFP inclusions overlap in many cases with round structures inside cells that can be distinguished by brightfield microscopy (Fig. 1). A possible explanation seemed to be the co-localization with intracellular LDs, and indeed we found overlap between the signals of αS-3K::YFP and lipid dyes (Fig. 1). However, we also provide new data on the co-localization of our ‘artificial’ αS lesions with endogenous cellular vesicle markers (Fig. 2). When focusing on endogenous marker proteins instead of co-expressed ones (Dettmer et al., 2017), we found overlap with endosomal (TfR, Rab5/7/11), but not Golgi apparatus (Fig. 2). In agreement with Dettmer et al., 2017, we saw no overlap with mitochondria or ER membranes. ER was clearly excluded from the inclusions, which appeared ‘embedded’ in ER (Fig. 2, Calnexin, arrow). A certain portion of cellular mitochondria seemed associated with inclusions, in the absence of direct overlap (Fig. 2, Tom20, arrow). Importantly, we had noticed that neuroblastoma cells transiently transfected with 3K or KLK αS are markedly stressed, leading to a large population of rounded and floating cells (Dettmer et al., 2015a, 2015b). In the present study, we decided to specifically observe via EM analysis such highly challenged cells to elucidate what type of cell-biological events might be responsible for their poor health (Figs. 3–5). We observed pronounced focal accumulation of αS amidst highly pronounced ‘medleys’ of lipid-rich organelles such as vesicles and LDs, oftentimes surrounded by mitochondria, generally in agreement with the LB characterization by Shahmoradian et al. We again did not observe apparent fibrillar proteinaceous inclusions, indicating that the cells were highly challenged by events either upstream of or unrelated to αS amyloid formation. A striking characteristic of these cells was massive membrane tubulation, which we had not observed to be that pronounced in our previous, more subtle models.

The nature of brain Lewy bodies and the relevance of our models.

As mentioned above, EM images of our new model systems gave no indications of clear-cut β-sheet-rich αS amyloid fibrils, neither in our previous (Dettmer et al., 2017) nor present study including in highly challenged cells. This has been in disagreement with the traditional perception of LBs as largely proteinaceous, fibrillar lesions (Spillantini et al., 1998), and prompted us to discuss the newfound disease-relevance of our model systems. We mentioned, however, in our previous 2017 publication that i) early EM characterization of Lewy bodies had reported the presence of many vesicles in the periphery of granular Lewy bodies (Fig. 4 in Forno and Norville, 1976) and Lewy body-related swellings (Figs. 5 and 6 in Forno and Norville, 1976); ii) similar phenomena had been described by other researchers (Roy and Wolman, 1969; Dickson et al., 1989); iii) numerous cored vesicles but few Lewy body filaments had been found in an autopsy case of juvenile parkinsonism (Hayashida et al., 1993); iv) an association of synaptic proteins and LBs had been described (Nishimura et al., 1994). Since our 2017 publication, unexpected data from the Stahlberg, van de Berg, and Lauer laboratories (and collaborators) have suggested that Lewy-type inclusions indeed may be less filamentous than previously thought and consist of crowded organelles and lipid membranes to a considerable extent (Shahmoradian et al., 2019). Using correlative light and electron microscopy, these authors found lipids, membrane fragments, and membranous organelles such as vesicles and mitochondria to be associated with αS accumulation in the lesions. αS itself was detected to a high degree in a non-filamentous state within the lesions. These striking observations prompted us to reconsider the interpretation of the cellular phenotypes that we had reported for our KTKEGV motif mutants. Having previously interpreted the lesions triggered by our lesions as potential precursors to mature Lewy pathology, the question arises in how far lipid/organelle-rich αS accumulation itself can be considered “Lewy-like”. This may be semantics, but nonetheless, recent events have added validity to the cellular phenotypes that we are able to elicit via designed αS variants that accumulate as monomers at membrane, due to an enhanced propensity to form amphipathic helices. It should be noted that the debate about the disease-relevance of non-fibrillar Lewy bodies is ongoing (e.g., Lashuel, 2020). Our current study adds to the debate the observation that it appears to be possible to highly stress and kill neural cells by expressing large amounts of membrane-enriched αS that does not seem to form fibrillar aggregates in the course of the experiment. Similar observations have been made in αS-overexpressing yeast cells (Volles and Lansbury, 2007).

Excess αS-membrane interactions cause aberrant membrane tubulation.

A surprising aspect of the lipid-rich lesions that we observed in our study was the highly pronounced tubulation activity of αS on membranes. While not explicitly mentioned in Shahmoradian et al. as a feature of αS in LBs, αS-mediated membrane tubulation has been observed in mouse models of the human familial-PD linked αS variant A53T (Martin et al., 2006). It appears possible that the extreme tubulation observed in this study represents an exaggeration of αS’s normal function: similar to apolipoproteins and the N-BAR protein endophilin-1, it has been proposed that αS has membrane curvature-inducing activity (Varkey et al., 2010; Westphal and Chandra, 2013). It has been demonstrated that cytosol-enriched αS A30P does not exhibit membrane-remodeling activity (Westphal and Chandra, 2013), and it is tempting to speculate that membrane-enriched αS (such as our 3K and KLK variants) are ‘hyperactive’ molecules with regard to inducing membrane curvature and tubulation. It is presently unclear how membrane-enriched αS molecules that appear to be monomeric by several measures (Dettmer et al, 2015a, 2015b, 2017) can achieve pronounced vesicle clustering and massive membrane remodeling in the absence of direct αS-αS interactions. A possible mechanism could be a ‘double anchor’ scenario by which one αS molecule may interact with two different vesicles (Fusco et al., 2016). Increasing numbers of such connections could lead to larger and larger vesicle clusters and, ultimately, to remodeling of the vesicles in a way that leads to tubule formation (Figs. 4, 5). In an alternative model, αS monomers stabilized at membranes may multimerize (transiently), consistent with models of membrane-associated multimer formation that have been proposed by the Roy (Wang et al., 2014) and Suedhof (Burré et al., 2014, 2015) labs. More work will be needed to establish the relevance of αS-induced membrane “deformation” in synucleinopathy pathogenesis: does this mechanism play a role in impairing cellular trafficking? Does it contribute to proteinaceous αS aggregation? Would membrane tubulation enhance the likelihood of prion-type αS transfer between neurons? It will also be interesting to see what phenotypes acute, very high expression of our αS variants will elicit in cultured neurons (rather than neuroblastoma cells). Based on previous work in neurons (Dettmer et al, 2015a, 2015b, 2017) and animals (Nuber et al., 2018), we expect to observe similar vesicle clusters and tubulation, and it will be interesting to see if it is more pronounced in the soma or in synaptic compartments. Lastly, it will be interesting to study if the αS C-terminus plays a critical role in inducing membrane remodeling, e.g., by recruiting additional factors such as SNARE proteins (Burré et al., 2010).

Conclusion.

The ‘artificial’ membrane/lipid-rich αS lesions triggered by our membrane-affine αS KTKEGV repeat mutations may have more in common with mature Lewy pathology in disease than we originally thought. The possibility that excess αS membrane binding can kill neural cells in the absence of αS fibrillization is a contribution to an ongoing debate about the disease relevance of non-fibrillar Lewy lesions. Moreover, it may be worthwhile to critically test the observed membrane tubulation activity of αS in the lesions for its potential disease relevance.

Materials and Methods

All materials mentioned were purchased from Invitrogen unless stated otherwise.

cDNA constructs.

Plasmids pcDNA4/αS-3K::YFP (Dettmer et al., 2015a) and pcDNA4/αS-KLK::YFP (Dettmer et al., 2015b) have been described.

Cell culture and transfection.

Human neuroblastoma cells (BE (2)-M17, called M17D; ATCC number CRL-2267) were cultured at 37 °C in 5% CO2 in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% FBS, 50 units per mL penicillin, 50 μg per mL streptomycin, and 2 mM L-glutamine. Cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000.

Inducible cell lines.

Tet-on lines M17D-TR/αS-3K::YFP and M17D-TR/αS-KLK::YFP were generated by co-transfecting pcDNA6/TR and plasmids pcDNA4/αS-3K::YFP (Dettmer et al., 2015a) and pcDNA4/αS-KLK::YFP (Dettmer et al., 2015b), followed by Blasticidin (1 μg per mL) and Zeocin (200 ng per mL) selection. Expression was induced by adding 1 μg per mL (f.c.) doxycycline to culture media.

Immunocytochemistry and lipid dye.

Cells were grown on poly-D-lysine-coated surfaces, rinsed twice with HBSS with divalent cations, fixed 25 min at RT with 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS, then washed 3x for 5 min with PBS. Cells were then blocked and permeabilized with 5% BSA/0.25% Triton X-100/PBS. Cells were incubated with primary antibody in block-permeabilizing buffer for 2 h at RT or overnight at 4 °C. After incubation with primary antibody, cells were washed 3x for 5 min with PBS, then incubated 1–2 h at RT with Alexa Fluor 568-coupled secondary antibodies diluted 1:2000 in 5% BSA/PBS (no Triton). Cells were washed 3 × 10 min at RT with PBS, then analyzed directly in the dish. Cells were treated with lipid dye (HCS LipidTOX™ deep red neutral lipid dye) following the manufacturer’s manual.

Antibodies.

Antibodies used for IF were polyclonals ab84036 to TfR (abcam; 1:1000 in ICC), FL-145 to TOM20 (Santa Cruz; 1:400 in ICC), ab22595 to Calnexin (abcam; 1:200 in ICC), C8B1 to Rab5 (Cell Signaling; 1:200 in ICC), D95F2 to Rab7 (Cell Signaling; 1:200 in ICC), and D4F5 to Rab11 (Cell Signaling; 1:200 in ICC).

Fluorescence microscopy.

Fluorescence microscopy of cells in culture dishes was done on an AxioVert 200 microscope (AxioCam MRm camera; AxioVision Release 4.8.2; all by Zeiss, Jena, Germany). Images of YFP were collected using a GFP/FITC filter cube and are pseudo-colored. Confocal images were obtained on a Zeiss LSM710 system.

Live-cell imaging.

Cells were incubated (96 or 384 well plates) in the IncuCyte Zoom 2000 platform (Essen Biosciences) and images (green, red, bright field) were taken every 2 h. LDs were visualized using the HCS LipidTOX™ deep red neutral lipid dye following the manufacturer’s protocol.

Electron microscopy.

Cells were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde, 1.25% paraformaldehyde, 0.03% picric acid in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) for 1 h. Then they were washed 3x in 0.1 M Cacodylate buffer, postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide (OsO4)/1.5% potassium ferrocyanide (KFeCN6) for 30 min, washed in water 3x, and incubated in 1% aqueous uranyl acetate for 30 min followed by 2 washes in water and subsequent dehydration in grades of alcohol (5 min each; 50%, 70%, 95%, 2× 100%). Cells were embedded in TAAB Epon (TAAB Laboratories Equipment Ltd, https://taab.co.uk) and polymerized at 60 °C for 48 h. Ultra-thin sections (about 80 nm) were cut on a Reichert Ultracut-S microtome and picked up onto copper grids. For immunogold labeling, the sections were etched using a saturated solution of sodium metaperiodate in water for 5 min at RT. Grids were then washed 3x in water and floated on 0.1% Triton-X-100 for 5 min at RT. Blocking was carried out using 1% BSA+0.1% TX-100/PBS for 1 h at RT. Grids were incubated with anti-αS antibody C20 (1:50, Santa Cruz) in 1% BSA+0.1% TX-100/PBS overnight at 4 °C. Grids were washed three times in PBS to remove unbound antibody followed by incubation with 15 nm Protein A-gold particles (Department of cell biology, University Medical Center Utrecht, the Netherlands) for 1 h at RT. Grids were washed with PBS and water, stained with lead citrate, and examined in a JEOL 1200EX Transmission electron microscope (JEOL USA Inc. Peabody, MA USA). Images were recorded with an AMT 2k CCD camera.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

Engineered α-synuclein variants that exhibit increased membrane binding cause the formation of inclusions rich in cellular vesicles and lipid droplets

When acutely expressed at high levels, membrane-enriched α-synuclein variants lead to massive tubulation of cellular membranes

The ability to perturb and to accumulate with organelles/lipids/membranes is reminiscent of a recent characterization of human Lewy bodies

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of the Selkoe, Khurana, Nuber, and Bartels labs (Ann Romney Center for Neurologic Diseases) for many helpful discussions, and Elizabeth Terry-Kantor (Dettmer lab) for proofreading and feedback on the manuscript. This work was supported by NIH grant R01 NS099328 to UD. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Literature

- Bartels T, Choi JG, Selkoe DJ, 2011. α-Synuclein occurs physiologically as a helically folded tetramer that resists aggregation. Nature 477, 107–110. 10.1038/nature10324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burré J, Sharma M, Südhof TC, 2015. Definition of a Molecular Pathway Mediating α-Synuclein Neurotoxicity. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci 35, 5221–5232. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4650-14.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burré J, Sharma M, Südhof TC, 2014. α-Synuclein assembles into higher-order multimers upon membrane binding to promote SNARE complex formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 111, E4274–4283. 10.1073/pnas.1416598111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burré J, Sharma M, Tsetsenis T, Buchman V, Etherton MR, Südhof TC, 2010. Alpha-synuclein promotes SNARE-complex assembly in vivo and in vitro. Science 329, 1663–1667. 10.1126/science.1195227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra S, Chen X, Rizo J, Jahn R, Südhof TC, 2003. A broken alpha -helix in folded alpha -Synuclein. J. Biol. Chem 278, 15313–15318. 10.1074/jbc.M213128200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole NB, Murphy DD, Grider T, Rueter S, Brasaemle D, Nussbaum RL, 2002. Lipid droplet binding and oligomerization properties of the Parkinson’s disease protein alpha-synuclein. J. Biol. Chem 277, 6344–6352. 10.1074/jbc.M108414200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson WS, Jonas A, Clayton DF, George JM, 1998. Stabilization of alpha-synuclein secondary structure upon binding to synthetic membranes. J. Biol. Chem 273, 9443–9449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dettmer U, 2018. Rationally Designed Variants of α-Synuclein Illuminate Its in vivo Structural Properties in Health and Disease. Front. Neurosci 12, 623. 10.3389/fnins.2018.00623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dettmer U, Newman AJ, Luth ES, Bartels T, Selkoe D, 2013. In vivo cross-linking reveals principally oligomeric forms of α-synuclein and β-synuclein in neurons and non-neural cells. J. Biol. Chem 288, 6371–6385. 10.1074/jbc.M112.403311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dettmer U, Newman AJ, Soldner F, Luth ES, Kim NC, von Saucken VE, Sanderson JB, Jaenisch R, Bartels T, Selkoe D, 2015a. Parkinson-causing α-synuclein missense mutations shift native tetramers to monomers as a mechanism for disease initiation. Nat. Commun 6, 7314. 10.1038/ncomms8314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dettmer U, Newman AJ, von Saucken VE, Bartels T, Selkoe D, 2015b. KTKEGV repeat motifs are key mediators of normal α-synuclein tetramerization: Their mutation causes excess monomers and neurotoxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 112, 9596–9601. 10.1073/pnas.1505953112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dettmer U, Ramalingam N, von Saucken VE, Kim T-E, Newman AJ, Terry-Kantor E, Nuber S, Ericsson M, Fanning S, Bartels T, Lindquist S, Levy OA, Selkoe D, 2017. Loss of native α-synuclein multimerization by strategically mutating its amphipathic helix causes abnormal vesicle interactions in neuronal cells. Hum. Mol. Genet 26, 3466–3481. 10.1093/hmg/ddx227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson DW, Crystal H, Mattiace LA, Kress Y, Schwagerl A, Ksiezak-Reding H, Davies P, Yen SH, 1989. Diffuse Lewy body disease: light and electron microscopic immunocytochemistry of senile plaques. Acta Neuropathol. (Berl.) 78, 572–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fares M-B, Ait-Bouziad N, Dikiy I, Mbefo MK, Jovičić A, Kiely A, Holton JL, Lee S-J, Gitler AD, Eliezer D, Lashuel HA, 2014. The novel Parkinson’s disease linked mutation G51D attenuates in vitro aggregation and membrane binding of α-synuclein, and enhances its secretion and nuclear localization in cells. Hum. Mol. Genet 23, 4491–4509. 10.1093/hmg/ddu165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forno LS, Norville RL, 1976. Ultrastructure of Lewy bodies in the stellate ganglion. Acta Neuropathol. (Berl.) 34, 183–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusco G, Pape T, Stephens AD, Mahou P, Costa AR, Kaminski CF, Kaminski Schierle GS, Vendruscolo M, Veglia G, Dobson CM, De Simone A, 2016. Structural basis of synaptic vesicle assembly promoted by α-synuclein. Nat. Commun 7, 12563. 10.1038/ncomms12563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvagnion C, Buell AK, Meisl G, Michaels TCT, Vendruscolo M, Knowles TPJ, Dobson CM, 2015. Lipid vesicles trigger α-synuclein aggregation by stimulating primary nucleation. Nat. Chem. Biol 11, 229–234. 10.1038/nchembio.1750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibb WR, Scott T, Lees AJ, 1991. Neuronal inclusions of Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. Off. J. Mov. Disord. Soc 6, 2–11. 10.1002/mds.870060103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashida K, Oyanagi S, Mizutani Y, Yokochi M, 1993. An early cytoplasmic change before Lewy body maturation: an ultrastructural study of the substantia nigra from an autopsy case of juvenile parkinsonism. Acta Neuropathol. (Berl.) 85, 445–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jao CC, Hegde BG, Chen J, Haworth IS, Langen R, 2008. Structure of membrane-bound alpha-synuclein from site-directed spin labeling and computational refinement. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 105, 19666–19671. 10.1073/pnas.0807826105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lashuel HA, 2020. Do Lewy bodies contain alpha-synuclein fibrils? and Does it matter? A brief history and critical analysis of recent reports. Neurobiol. Dis 141, 104876. 10.1016/j.nbd.2020.104876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Londos C, Brasaemle DL, Schultz CJ, Segrest JP, Kimmel AR, 1999. Perilipins, ADRP, and other proteins that associate with intracellular neutral lipid droplets in animal cells. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol 10, 51–58. 10.1006/scdb.1998.0275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maroteaux L, Scheller RH, 1991. The rat brain synucleins; family of proteins transiently associated with neuronal membrane. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res 11, 335–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin LJ, 2006. Parkinson’s Disease -Synuclein Transgenic Mice Develop Neuronal Mitochondrial Degeneration and Cell Death. J. Neurosci 26, 41–50. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4308-05.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura M, Tomimoto H, Suenaga T, Nakamura S, Namba Y, Ikeda K, Akiguchi I, Kimura J, 1994. Synaptophysin and chromogranin A immunoreactivities of Lewy bodies in Parkinson’s disease brains. Brain Res. 634, 339–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuber S, Rajsombath M, Minakaki G, Winkler J, Müller CP, Ericsson M, Caldarone B, Dettmer U, Selkoe DJ, 2018. Abrogating Native α-Synuclein Tetramers in Mice Causes a L-DOPA-Responsive Motor Syndrome Closely Resembling Parkinson’s Disease. Neuron 100, 75–90.e5. 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.09.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuscher B, Kamp F, Mehnert T, Odoy S, Haass C, Kahle PJ, Beyer K, 2004. Alpha-synuclein has a high affinity for packing defects in a bilayer membrane: a thermodynamics study. J Biol Chem 279, 21966–75. 10.1074/jbc.M401076200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlmutter JD, Braun AR, Sachs JN, 2009. Curvature dynamics of alpha-synuclein familial Parkinson disease mutants: molecular simulations of the micelle- and bilayer-bound forms. J. Biol. Chem 284, 7177–7189. 10.1074/jbc.M808895200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rovere M, Powers AE, Jiang H, Pitino JC, Fonseca-Ornelas L, Patel DS, Achille A, Langen R, Varkey J, Bartels T, 2019. E46K-like α-synuclein mutants increase lipid interactions and disrupt membrane selectivity. J. Biol. Chem 10.1074/jbc.RA118.006551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rovere M, Sanderson JB, Fonseca-Ornelas L, Patel DS, Bartels T, 2018. Refolding of helical soluble α-synuclein through transient interaction with lipid interfaces. FEBS Lett. 10.1002/1873-3468.13047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy S, Wolman L, 1969. Ultrastructural observations in Parkinsonism. J. Pathol 99, 39–44. 10.1002/path.1710990106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahmoradian SH, Lewis AJ, Genoud C, Hench J, Moors TE, Navarro PP, Castaño-Díez D, Schweighauser G, Graff-Meyer A, Goldie KN, Sütterlin R, Huisman E, Ingrassia A, Gier Y. de, Rozemuller AJM, Wang J, Paepe AD, Erny J, Staempfli A, Hoernschemeyer J, Großerüschkamp F, Niedieker D, El-Mashtoly SF, Quadri M, Van IJcken WFJ, Bonifati V, Gerwert K, Bohrmann B, Frank S, Britschgi M, Stahlberg H, Van de Berg WDJ, Lauer ME, 2019. Lewy pathology in Parkinson’s disease consists of crowded organelles and lipid membranes. Nat. Neurosci 22, 1099–1109. 10.1038/s41593-019-0423-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spillantini MG, Crowther RA, Jakes R, Hasegawa M, Goedert M, 1998. alpha-Synuclein in filamentous inclusions of Lewy bodies from Parkinson’s disease and dementia with lewy bodies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 95, 6469–6473. 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varkey J, Isas JM, Mizuno N, Jensen MB, Bhatia VK, Jao CC, Petrlova J, Voss JC, Stamou DG, Steven AC, Langen R, 2010. Membrane curvature induction and tubulation are common features of synucleins and apolipoproteins. J. Biol. Chem 285, 32486–32493. 10.1074/jbc.M110.139576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volles MJ, Lansbury PT, 2007. Relationships between the sequence of alpha-synuclein and its membrane affinity, fibrillization propensity, and yeast toxicity. J. Mol. Biol 366, 1510–1522. 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.12.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Das U, Scott DA, Tang Y, McLean PJ, Roy S, 2014. α-synuclein multimers cluster synaptic vesicles and attenuate recycling. Curr. Biol. CB 24, 2319–2326. 10.1016/j.cub.2014.08.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinreb PH, Zhen W, Poon AW, Conway KA, Lansbury PT Jr, 1996. NACP, a protein implicated in Alzheimer’s disease and learning, is natively unfolded. Biochemistry 35, 13709–13715. 10.1021/bi961799n [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westphal CH, Chandra SS, 2013. Monomeric synucleins generate membrane curvature. J. Biol. Chem 288, 1829–1840. 10.1074/jbc.M112.418871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeboah F, Kim T-E, Bill A, Dettmer U, 2019. Dynamic behaviors of α-synuclein and tau in the cellular context: New mechanistic insights and therapeutic opportunities in neurodegeneration. Neurobiol. Dis 132, 104543. 10.1016/j.nbd.2019.104543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.