Abstract

The post-infection of COVID-19 includes a myriad of neurologic symptoms including neurodegeneration. Protein aggregation in brain can be considered as one of the important reasons behind the neurodegeneration. SARS-CoV-2 Spike S1 protein receptor binding domain (SARS-CoV-2 S1 RBD) binds to heparin and heparin binding proteins. Moreover, heparin binding accelerates the aggregation of the pathological amyloid proteins present in the brain. In this paper, we have shown that the SARS-CoV-2 S1 RBD binds to a number of aggregation-prone, heparin binding proteins including Aβ, α-synuclein, tau, prion, and TDP-43 RRM. These interactions suggests that the heparin-binding site on the S1 protein might assist the binding of amyloid proteins to the viral surface and thus could initiate aggregation of these proteins and finally leads to neurodegeneration in brain. The results will help us to prevent future outcomes of neurodegeneration by targeting this binding and aggregation process.

Keywords: COVID-19, Heparin, Heparin binding proteins, Neurodegeneration, Protein aggregation, SARS-CoV-2

1. Introduction

The long-term post-infection complications of COVID-19 can be associated with neurological symptoms of neurodegenerative diseases. The major risk factors for the COVID-19 includes age, heart disease, diabetes and hypertension [1]. Several studies suggested that SARS-CoV-2 infection increases the risk for neurodegenerative diseases [[2], [3], [4], [5]]. SARS-CoV-2 invasion to the CNS and the noticeable cytokine storm, metabolic changes, gut microbiome changes, neuroendocrine axis, and hypoperfusion during COVID-19 infection could be attributed to the different neurological distresses observed in the nervous system [[5], [6], [7]]. It has been shown that infection from human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), West Nile virus, herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), H1N1 influenza A virus, and respiratory syncytial virus causes several neurological manifestations, including encephalitis, protein aggregation, neurodegeneration, and Parkinson’s disease- or Alzheimer’s like symptoms [8]. H1N1 infection to dopaminergic neurons expressing α-synuclein resulted in aggregation of α-synuclein and inhibition of autophagy, and thus increased the susceptibility of neurodegeneration [9].

Very recently, Tavassoly et al. proposed a view that seeded protein aggregation by SARS-CoV-2 could be attributed to long-term post-infection complications including neurodegeneration [4]. They suggested that SARS-CoV-2 spike protein S1 region binds to heparin and heparin binding proteins (HBPs) present in brain which are prone to self-assembly, aggregation, and fibrillation processes. They also showed that the peptide from S protein (S–CoV-peptide; ∼150 aa) has more aggregation formation propensity than the known aggregation-prone proteins, suggesting that this peptide is prone to act as functional amyloid and form toxic aggregates. Thus, the heparin binding and aggregation propensity of S1 protein has been suggested the ability of S1 to form amyloid and toxic aggregates that can act as seeds to aggregate many of the misfolded brain proteins and can ultimately leads to neurodegeneration. It has been suggested that SARS-CoV-2 infection invades the CNS by controlling protein synthesis machinery, disturbs endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondrial function and increases the accumulation of misfolded proteins, thereby activates protein aggregation, mitochondrial oxidative stress, apoptosis and neurodegeneration [3,5,10].

Interestingly, it has been shown that HSV-1 spike protein binds to heparin and increases the aggregation of amyloid β (Aβ42) peptides on its surface spikes [11]. This study suggests that the heparin-binding site of the spike protein might act as a binding site for Aβ42 peptides and thus could dock to the viral surface and catalyze aggregation of Aβ42. As the receptor binding domain (RBD) of SARS-CoV-2, which is located within the S1 subunit of spike glycoprotein has several heparin binding sites [[12], [13], [14]], the same mechanism of aggregation of neurodegeneration causing proteins such as Aβ, α-synuclein, tau, prions, and TDP-43 can be observed in COVID-19 infection in the brain.

In this study, we have investigated the interactions of SARS-CoV-2 S1 RBD to different amyloid forming proteins including Aβ, α-synuclein, tau, prions, and TAR DNA binding protein-43 (TDP-43). We also examine the binding of S1 RBD to heparin and their complex to the different amyloidogenic proteins present in the brain. The insights will help us in understanding the heparin binding induced increase in association of HBPs observed in neurodegeneration and also to prevent future outcomes of neurodegeneration by targeting this association process.

2. Methods

Protein-protein docking of SARS-CoV-2 S RBD (PDB ID:6M0J) with proteins Aβ (PDB ID:1Z0Q), α-synuclein (PDB ID:1XQ8), tau (PDB ID:6QJH), prion (PDB ID:1U5L), RNA recognition motifs of TDP-43 (PDB ID:4BS2) were performed with the HDOCK server (http://hdock.phys.hust.edu.cn/), which is based on a hybrid algorithm of template-based modeling and ab initio free docking [15]. The HDOCK server globally samples all possible binding modes between the two proteins through a fast Fourier transform (FFT)-based algorithm [16]. Then, all the sampled binding modes were evaluated by iterative knowledge-based scoring function ITScorePP [17]. Finally, the binding mode of macromolecules was evaluated by the binding energy and ranked them according to their docking energies.

The structure model with the lowest docking energy score and the highest ligand root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) was selected to analyse the binding energy scores (Kd) using PRODIGY server [18]. PRODIGY is a robust predictive system that utilises structural properties of protein-protein interactions, the number of interfacial contacts and non-interacting surfaces to calculate proteins binding affinity [19].

Further, the residual interactions of the three-dimensional model of protein complexes were analysed through PDBSUM server (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbsum). The bonded and non-bonded interacting residues between the protein-protein interactions were examined.

3. Results and discussion

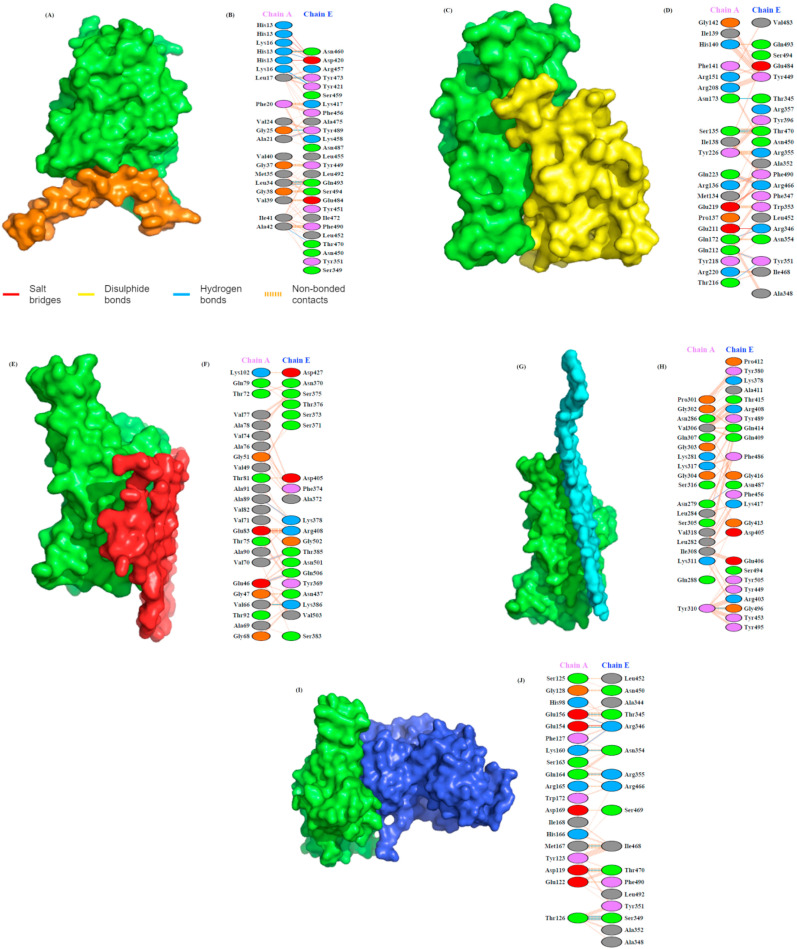

Many biological functions of protein depend upon the formation of protein-protein interactions. The HDOCK server [15] was used to estimate potential interactions between the amyloid-forming proteins (Aβ, α-Syn, tau, prion and TDP-43) and SARS-CoV-2 S1 RBD. This server generates 100 theoretical models of possible protein-protein (peptide) interactions and scores them based on docking energy. Model 1 with the highest docking energy score and the lowest ligand RMSD was selected. The docking results are summarized in Fig. 1 and Table 1, Table 2 .

Fig. 1.

SARS-CoV-2 spike protein S1 RBD domain interactions to amyloid forming HBPs. (A) Docking model of the interaction of heparin-binding domains of spike protein, S1 (green) and Aβ (brown). (B) Detailed molecular interactions between S1 (chain E) and Aβ (chain A) residues deduced by PDBsum. (C) Docking model showing the interaction of S1 (green) to Prion (yellow). (D) Molecular interactions of S1 (chain E) to prion protein (chain A). (E) Surface diagram of S1 (green)-α-Syn complex (red) model and (F) residual interactions of this complex. (G) Model of S1(green)-tau complex structure and (H) the molecular interactions between the tau (chain A) and the heparin-binding domain of spike protein S1 (chain E). (I) Docking model showing the interaction of S1 (green) with the RRM of TDP-43 (blue), and (J) detailed molecular interactions between spike protein S1 (chain E) and RRM (chain A). Key interactions between residues are shown as dotted lines. The key interactions are color coded as: salt bridges (red), disulfide bonds (yellow), hydrogen bonds (blue), and non-bonded contacts (orange). The number of lines indicates the potential number of bonds. For non-bonded contacts, the width of the striped line indicates the number of potential contacts.

Table 1.

Molecular docking of SARS-CoV-2 S1 RBD domain to amyloid forming proteins determined by HDOCK server.

| Protein-protein complex | Docking score | ΔG (kcal mol−1) | Kd (M) at 25.0 °C/40.0 °C |

|---|---|---|---|

| S1-Aβ | −262.91 | −12.4 | 8.5E-10/2.3E-09 |

| S1-PRION | −285.39 | −12.8 | 3.9E-10/1.1E-09 |

| S1-α-Syn | −230.93 | −13.1 | 2.3E-10/6.6E-10 |

| S1-TAU | −258.39 | −11.5 | 3.5E-09/8.8E-09 |

| S1-RRM | −238.26 | −12.3 | 9.7E-10/2.6E-09 |

| S1-FGF2 | −242.75 | −13.2 | 2.2E-10/6.4E-10 |

Table 2.

Molecular docking scores of heparin and heparin binding proteins and its comparison to the docking score of SARS-CoV-2 S1-heparin complex to amyloid forming proteins.

| Protein-heparin complex | Docking score | S1-heparin (S1–H)-Protein complex | Docking score |

|---|---|---|---|

| S1-Heparin | −282.57 | ||

| Aβ-Heparin | −235.28 | S1H-Abeta | −323.21 |

| Prion-Heparin | −276.48 | S1H-Prion | −310.39 |

| α-Syn-Heparin | −214.57 | S1H-α-Syn | −323.02 |

| TAU-Heparin | −233.68 | S1H-Tau | −257.20 |

| RRM-Heparin | −256.50 | S1H-RRM | −340.03 |

| FGF-Heparin | −220.74 |

The protein-protein docking suggests that the binding affinity of SARS-CoV-2 S1 towards the selected proteins is favourable with higher docking energy scores. On the basis of docking scores, the increasing affinity of proteins towards S1 is arranged as: Prion > Aβ>Tau > RRM> α-Syn (Table 1). Interestingly, interaction of heparin with S1 protein is also strong with the docking score of −282.57, much higher than all the proteins studied except prion protein. PDBSum is used to determine the interacting residues of protein complex. The interacting surfaces and the binding residues are shown in Fig. 1.

Docking results showed that interaction of S1 with Aβ (docking score: −262.91) is strongly mediated by five hydrogen bonds and one salt bridge. Fig. 1B illustrates that Aβ forms 8 H-bonds through His13, Lys16, Leu17, Ala21, Gly25, Leu34, and Ala42 Ala42 residues with Asp420, Tyr421, Asn460, Thr470, Tyr473, Tyr489, and Gln493 of S1 protein. His13 and Lys16 and Lys16 of Aβ form 4 salt bridges with Asp420 of S1. Prion protein forms seven H-bonds and two salt bridges with S1 protein (docking score: −285.39) (Fig. 1D). The prion residues involved in H-bonding are Asn173, Gln172, Gln212, Thr216, Gln223, and Ser135 with Thr345, Arg346, Tyr351, Arg466, and Thr470 of S1 protein. Glu211 and Glu219 of prion protein forms salt bridge with Arg346, and Arg466 of S1 protein.

S1-α-Syn complex (docking score: −230.93) shows four H-bonds and one salt bridge (Fig. 1F). The H-bonds are formed between Ala89, Val70, Val66, and Glu46 of Syn protein to Lys378, Thr385, Lys386, and Gln506 of S1 protein. The only one salt bridge form between Glu83 and Arg408. In the case of Tau-S1 protein complex (docking score: −258.39), two H-bonds are formed (Fig. 1H). The H-bond forms between Asn279, and Tyr310 of tau to Asn487, and Gly496 of S1 protein. TDP-43 RRMs (RRM1 and RRM2) form eleven H-bonds and one salt bridge interaction with S1 protein having docking score of −238.26 (Fig. 1J). The H-bonds formed between Glu156, Lys160, Glu154, Thr126, Lys160, Gln164, met167, and Asp119 of RRMs to Thr345, Arg346, Ser349, Asn354, Arg355, Ile468, and Thr470 of S1 protein. The only one salt bridge formed between Glu154 of RRM and Arg346 of S1 protein.

Furthermore, interaction of fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF2), a well characterised heparin-binding protein with S1 protein showed docking score of −242.75 significantly less than that of Aβ, prion, and tau protein but greater than α-Syn and TDP-43 RRM.

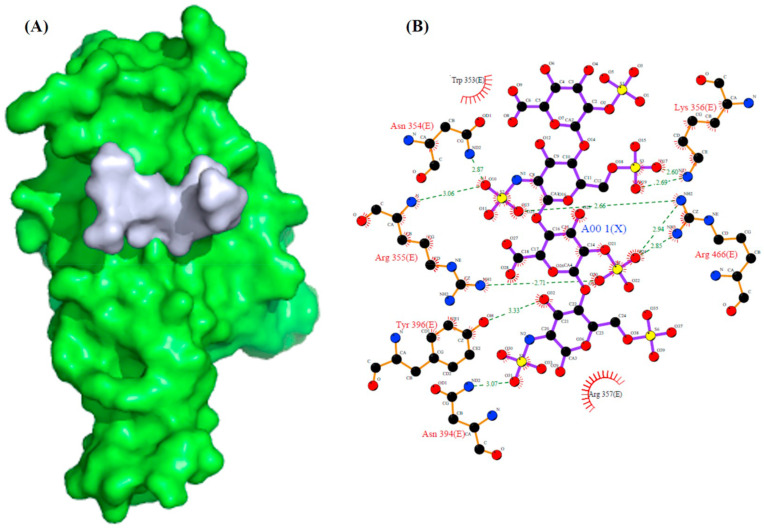

We have also analysed the interaction of SARS-CoV-2 S1 and amyloid forming HBPs to heparin (PDB ID: 1HPN) to analyse the binding interactions and affinity to heparin (Table 2). Docking results showed that interaction of S1 with heparin (docking energy score: −282.57) is strongly mediated by H-bonds formed by residues Asn354, Arg355, Lys 356, Asn394, Tyr396, and Arg466 (Fig. 2 ). Interestingly, the docking scores suggest that S1 interacts strongly to heparin compared to all of the amyloid forming proteins. Based on docking scores, the interaction between protein and heparin is arranged in order: S1-heparin > Prion-heparin > RRM-heparin > Aβ-heparin > Tau-heparin >α-Syn-heparin (Table 2). Also, the docking score of FGF2-heparin (−220.74) is less than all of these proteins, indicating that the neurodegeneration causing proteins and SARS-CoV-2 S1 protein binds more strongly to heparin.

Fig. 2.

SARS-CoV-2 spike protein S1 RBD domain interactions to Heparin. (A) Docking model of the interaction of heparin (grey) to heparin-binding domains of spike protein, S1 (green). (B) The Ligplot diagram showing the detailed molecular interactions between S1 and heparin as observed by PDBsum.

Next, we look for the interaction of S1-heparin complex to the amyloid forming HBPs (Table 2). Interestingly, the SARS-CoV-2 S1-heparin complex binds more strongly to these HBPs when compared to the docking strength of S1-HBPs complex. This result clearly suggests that heparin binding to S1 protein allows the amyloid forming HBPs to bind more strongly to S1 protein. The docking scores indicate that α-syn binds more strongly to S1-heparin complex followed by RRM > Aβ >Prion > Tau (Table 2).

Next, we calculated the binding affinities (Kd) of the docked structures using the PRODIGY server [18] (Table 1). The binding affinities of S1-complexes showed that S1-α-Syn complex has a stronger binding affinity (2.3 × 10−10 M) among other complexes, followed by S1-prion (3.9 × 10−10 M), S1-Aβ (8.5 × 10−10 M), S1-RRM (9.7 × 10−10 M), and S1-tau (3.5 × 10−9 M). This indicates that α-Syn has a more favourable binding affinity to SARS-CoV-2 S1 protein. The binding affinity of S1 to FGF2 indicates the favourable binding with the Kd of 2.2 × 10−10 M.

Further, the binding energy scores (Kd) of S1 complexes were predicted as a function of temperature. There was an obvious increase in Kd as the temperature increased from 25 °C to 40 °C, indicating a decrease in binding affinity for SARS-CoV-2 S1 protein complexes. At higher temperature also, α-Syn appeared to have stronger binding affinity for S1 protein (6.6 × 10−10 M) followed by Prion (1.1 × 10−9 M), Aβ (2.3 × 10−9 M), RRM (2.6 × 10−9 M), and Tau protein (8.8 × 10−9 M).

Furthermore, the predicted Kd for S1-α-Syn and S1-tau complex was less affected as the temperature increased from 25 °C to 40 °C, in contrast to Aβ, prion and RRM. Increase in temperature usually disrupts the noncovalent interactions between a protein-protein complex, despite that, the decrease in binding affinity across the temperatures was less apparent for the α-Syn complex with S1. This suggests a stable interaction between α-synuclein to SARS-CoV-2 S1 protein.

4. Conclusion

In summary, the findings reported here support the hypothesis that the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein can interact with heparin binding amyloid forming proteins. Our results indicate stable binding of the S1 protein to these aggregation-prone proteins which might initiates aggregation of brain protein and accelerate neurodegeneration. These findings might explain the possible neurological distresses associated with COVID-19. Therefore, targeting the interaction of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein with the brain proteins might be a suitable way to reduce the aggregation process and thus neurodegeneration in COVID-19 patients.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, V.K; experiments and graphics, D.I; writing, reviewing and editing, D.I, and V.K.

Declaration of competing interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Acknowledgments

V.K. and D.I. sincerely thank the Amity University, Noida and Shree Guru Gobind Singh Tricentenary University, Gurugram, Haryana, respectively for providing facilities.

References

- 1.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y., Zhang L., Fan G., Xu J., Gu X., Cheng Z., Yu T., Xia J., Wei Y., Wu W., Xie X., Yin W., Li H., Liu M., Xiao Y., Gao H., Guo L., Xie J., Wang G., Jiang R., Gao Z., Jin Q., Wang J., Cao B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. S0140-6736(20)30183-5 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Solomon I.H., Normandin E., Bhattacharyya S., Mukerji S.S., Keller K., Ali A.S., Adams G., Hornick J.L., Padera R.F., Jr., Sabeti P. Neuropathological features of covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2019373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lippi A., Domingues R., Setz C., Outeiro T.F., Krisko A. SARS-CoV-2: at the crossroad between aging and neurodegeneration. Mov. Disord. 2020;35:716–720. doi: 10.1002/mds.28084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tavassoly O., Safavi F., Tavassoly I. Seeding brain protein aggregation by SARS-CoV-2 as a possible long-term complication of COVID-19 infection. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2020;11:3704–3706. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.0c00676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dolatshahi M., Sabahi M., Aarabi M.H. Pathophysiological clues to how the emergent SARS-CoV-2 can potentially increase the susceptibility to neurodegeneration. Mol. Neurobiol. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s12035-020-02236-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leonardi M., Padovani A., McArthur J.C. Neurological manifestations associated with COVID-19: a review and a call for action. J. Neurol. 2020;267:1573–1576. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-09896-z10.1007/s00415-020-09896-z. [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khatoon F., Prasad K., Kumar V. Neurological manifestations of COVID-19: available evidences and a new paradigm. J. Neurovirol. 2020;26:619–630. doi: 10.1007/s13365-020-00895-410.1007/s13365-020-00895-4. [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou L., Miranda-Saksena M., Saksena N.K. Viruses and neurodegeneration. Virol. J. 2013;10:172. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-10-1721743-422X-10-172. [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dolatshahi M., Pourmirbabaei S., Kamalian A., Ashraf-Ganjouei A., Yaseri M., Aarabi M.H. Longitudinal alterations of alpha-synuclein, amyloid beta, total, and phosphorylated tau in cerebrospinal fluid and correlations between their changes in Parkinson’s disease. Front. Neurol. 2018;9:560. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prasad K., AlOmar S.Y., Alqahtani S.A.M., Malik M.Z., Kumar V. Brain disease network analysis to elucidate the neurological manifestations of COVID-19. Mol. Neurobiol. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s12035-020-02266-w10.1007/s12035-020-02266-w. [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ezzat K., Pernemalm M., Palsson S., Roberts T.C., Jarver P., Dondalska A., Bestas B., Sobkowiak M.J., Levanen B., Skold M., Thompson E.A., Saher O., Kari O.K., Lajunen T., Sverremark Ekstrom E., Nilsson C., Ishchenko Y., Malm T., Wood M.J.A., Power U.F., Masich S., Linden A., Sandberg J.K., Lehtio J., Spetz A.L., El Andaloussi S. The viral protein corona directs viral pathogenesis and amyloid aggregation. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:2331. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10192-210.1038/s41467-019-10192-2. [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tavassoly O., Safavi F., Tavassoly I. Heparin-binding peptides as novel therapies to stop SARS-CoV-2 cellular entry and infection. Mol. Pharmacol. 2020;98:612–619. doi: 10.1124/molpharm.120.000098molpharm.120.000098. [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clausen T.M., Sandoval D.R., Spliid C.B., Pihl J., Perrett H.R., Painter C.D., Narayanan A., Majowicz S.A., Kwong E.M., McVicar R.N., Thacker B.E., Glass C.A., Yang Z., Torres J.L., Golden G.J., Bartels P.L., Porell R.N., Garretson A.F., Laubach L., Feldman J., Yin X., Pu Y., Hauser B.M., Caradonna T.M., Kellman B.P., Martino C., Gordts P., Chanda S.K., Schmidt A.G., Godula K., Leibel S.L., Jose J., Corbett K.D., Ward A.B., Carlin A.F., Esko J.D. SARS-CoV-2 infection depends on cellular heparan sulfate and ACE2. Cell. 2020;183:1043–1057 e1015. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.09.033. S0092-8674(20)31230-7 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim S.Y., Jin W., Sood A., Montgomery D.W., Grant O.C., Fuster M.M., Fu L., Dordick J.S., Woods R.J., Zhang F., Linhardt R.J. Characterization of heparin and severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) spike glycoprotein binding interactions. Antivir. Res. 2020;181:104873. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104873. S0166-3542(20)30287-4 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yan Y., Zhang D., Zhou P., Li B., Huang S.Y. HDOCK: a web server for protein-protein and protein-DNA/RNA docking based on a hybrid strategy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:W365–W373. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx4073829194. [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yan Y., Huang S.Y. Pushing the accuracy limit of shape complementarity for protein-protein docking. BMC Bioinf. 2019;20:696. doi: 10.1186/s12859-019-3270-y10.1186/s12859-019-3270-y. [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang S.Y., Zou X. An iterative knowledge-based scoring function for protein-protein recognition. Proteins. 2008;72:557–579. doi: 10.1002/prot.21949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xue L.C., Rodrigues J.P., Kastritis P.L., Bonvin A.M., Vangone A. PRODIGY: a web server for predicting the binding affinity of protein-protein complexes. Bioinformatics. 2016;32:3676–3678. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw514. btw514 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vangone A., Bonvin A.M. Contacts-based prediction of binding affinity in protein-protein complexes. Elife. 2015;4 doi: 10.7554/eLife.07454e07454. [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]