Abstract

O-GlcNAcylation is an essential post-translational modification that has been implicated in neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders. O-GlcNAcase (OGA), the sole enzyme catalyzing the removal of O-GlcNAc from proteins, has emerged as a potential drug target. OGA consists of an N-terminal OGA catalytic domain and a C-terminal pseudo histone acetyltransferase (HAT) domain with unknown function. To investigate phenotypes specific to loss of OGA catalytic activity and dissect the role of the HAT domain, we generated a constitutive knock-in mouse line, carrying a mutation of a catalytic aspartic acid to alanine. These mice showed perinatal lethality and abnormal embryonic growth with skewed Mendelian ratios after day E18.5. We observed tissue-specific changes in O-GlcNAc homeostasis regulation to compensate for loss of OGA activity. Using X-ray microcomputed tomography on late gestation embryos, we identified defects in the kidney, brain, liver, and stomach. Taken together, our data suggest that developmental defects during gestation may arise upon prolonged OGA inhibition specifically because of loss of OGA catalytic activity and independent of the function of the HAT domain.

Keywords: O-GlcNAcylation, O-GlcNAcase, perinatal lethality, mouse genetics, in vivo imaging, microcomputed tomography, glycobiology, development, embryo

Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer's disease; CDG, congenital disorder of glycosylation; CpOGA, clostridium perfringens O-GlcNAcase; HAT, histone acetyltransferase; ID, intellectual disability; mESC, mouse embryonic stem cell; microCT, microcomputed tomography; OGA, O-GlcNAcase; OGT, O-GlcNAc transferase

O-GlcNAcylation is a dynamic co-/post-translational modification of serine/threonine residues with N-acetyl-d-glucosamine, responsible for modulating cellular functions, such as translation (1), protein stability (2, 3), and subcellular localization of proteins (4, 5). O-GlcNAcylation is dependent on the nutrient flux through the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway and coordinates transcription (6, 7, 8, 9) and differentiation (10, 11, 12) according to the metabolic status of the cell and organism. The entire O-GlcNAcome, over 4000 proteins, is established by O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) (13) that catalyzes the addition of N-acetylglucosamine and O-GlcNAcase (OGA) that mediates the removal of the modification (14).

O-GlcNAcylation and the O-GlcNAc cycling enzymes are critical for normal development in several organisms. In Drosophila, ogt, also known as super sex combs (sxc), is essential for viability and correct segment identity specification (15, 16). Ogt KO leads to impaired embryonic growth and cell viability in zebrafish (17). Deletion of either Ogt or Oga is lethal in mice (18, 19, 20). In mammals, OGT and OGA are ubiquitously expressed, and they regulate the development of several tissues (21, 22, 23). O-GlcNAcylation modification is particularly abundant in the mammalian brain (24, 25, 26), and both O-GlcNAc cycling enzymes are important for normal development and function of the central nervous system (27, 28, 29). Very recently, missense OGT mutations have been identified and characterized in patients affected with intellectual disability (ID) in association with developmental delay and brain anomalies (30). ID is a neurodevelopmental disorder that affects 1 to 2% of the population and is characterized by impaired cognitive function and adaptive behavior (31). Phenotypic characterization of several OGT variants gave rise to a new syndrome of congenital disorder of glycosylation named OGT-CDG; however, the mechanisms underlying the patient brain phenotypes remain unknown (30). Interestingly, a reduction of OGA expression was observed in several mouse embryonic stem cell (mESC) lines carrying OGT-CDG mutations (32, 33, 34, 35), suggesting that altered OGA expression may be associated with reduced OGT activity in some mutations and might contribute in part to the neuronal phenotype in these patients. OGA has been shown to contribute to proper brain function using several animal models. In flies, loss of OGA activity affects cognition and synaptic morphology (36). Viable heterozygous Oga+/− mice exhibit learning and memory impairment (29). In addition, a genome-wide association study using 14 independent epidemiological human cohorts has associated SNPs in OGA with intelligence and cognitive function (37), suggesting a role of OGA in human cognitive function.

Deregulation of O-GlcNAcylation has also been linked to neurodegenerative disease. However, it appears difficult to define a general neuroprotective or neurodegenerative role for O-GlcNAcylation. O-GlcNAc protein levels are found reduced in Alzheimer's disease (AD) while being increased in Parkinson's disease postmortem human brain tissues (38, 39). Many proteins associated with these diseases are O-GlcNAcylated, including tau, α-synuclein, and β-amyloid precursor proteins (40). Several studies have shown that reduction of O-GlcNAc levels leads to neurodegeneration. For example, the reduction of O-GlcNAcylation in forebrain excitatory neurons leads to progressive neurodegeneration associated with neuronal cell death, neuroinflammation, increased levels of hyperphosphorylated tau, and β-amyloid peptides in mice (41). Moreover, it has been shown that O-GlcNAc at specific sites reduced α-synuclein aggregation and cell toxicity using synthetic protein methodology (42). However, other studies have also suggested a role of increased O-GlcNAcylation in neurodegeneration. Increase of O-GlcNAc modification in the mouse hippocampus and neuronal precursor cells is associated with neuronal apoptosis (24, 43). In addition, elevation of O-GlcNAc levels through pharmacological OGA inhibition causes an increase of α-synuclein accumulation and a decrease of autophagic flux prior to neuronal cell death in rat primary neurons (38). Considering the number of O-GlcNAc-modified proteins in the brain, it is likely that the role of this protein modification depends on each specific substrate and the cellular, tissue, and disease contexts.

Nevertheless, emerging evidence suggests that elevation of O-GlcNAc levels through pharmacological inhibition of OGA may be a relevant therapeutic strategy for the treatment of AD. OGA inhibition through chronic treatment with OGA inhibitors reduces tauopathy phenotypes in several mouse AD models (44, 45, 46, 47). It has been hypothesized that O-GlcNAcylation of tau could prevent its phosphorylation and aggregation (48). Although a reduction in tau hyperphosphorylation and aggregation have been observed after OGA inhibition, it remains uncertain whether it is mediated directly through O-GlcNAcylation as increase in tau O-GlcNAcylation in vivo has only been observed in one study (44). It may be possible that the observed benefits are mediated through other O-GlcNAcylated substrates as global elevation of O-GlcNAcylation is achieved upon OGA inhibition. Considering that O-GlcNAcylation is important in regulating several biological functions, it is imperative to understand the molecular mechanisms and physiological consequences of prolonged OGA inhibition.

Despite the critical role of OGA, our understanding about how OGA activity participates in development and pathological process remains limited. OGA is a 103 kDa multidomain protein (Fig. 1A); it consists of an N-terminal O-GlcNAc hydrolase catalytic domain with sequence homology to glycoside hydrolase family 84, a middle, mostly disordered, “stalk” domain and a C-terminal domain showing sequence homology to GCN5-related histone acetyltransferases (HATs) (49). Initially, OGA was reported to possess HAT activity (50), but other studies failed to reproduce this observation (51, 52, 53). OGA most likely contains a pseudo-HAT domain because it lacks key amino acids required for acetyl coenzyme A binding (52) required for histone acetylation. Thus, it has been established that OGA only possesses OGA catalytic activity (52). Phenotypic comparison of OgaKO and catalytically dead OgaD133N Drosophila alleles, however, revealed differences in behavior and neuronal phenotypes that suggest nonenzymatic functions of the OGA protein backbone (36). These additional functions could be potentially dependent on the HAT domain whose function still remains unknown.

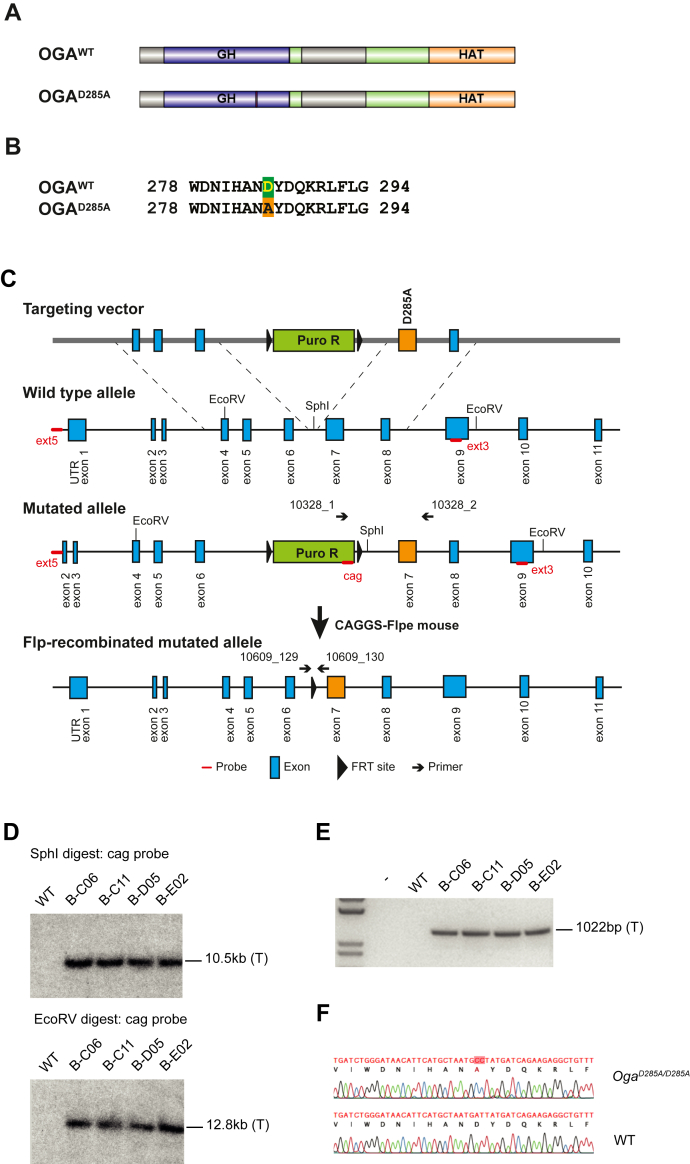

Figure 1.

Generation of the O-GlcNAcase catalytically dead OgaD285Aknock-in mouse line.A, schematic representation of OGA protein; purple glycosyl hydrolase (GH) domain, green stalk domain, and orange pseudo-histone acetyltransferase domain. Unstructured regions are colored gray. The OgaD285A allele expresses full-length OGA with a single D285A missense mutation in the GH domain (the mutation site is in orange). B, sequences of OGAWT and OGAD285A 278 to 294 residues highlighting the D285A site are shown in green/orange. C, schematic representation of the ∼10 kb OgaD285A transgene targeting exon 4 to 8 in the Oga gene used to generate OgaD285A mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs). Recombinant cell colonies, encoding FRT-flanked puromycin resistance gene, were isolated and injected into blastocysts. Highly chimeric progenies were crossed with Flp deleter (C57BL/6-Tg(CAG-Flpe)2Arte) mice to eliminate puromycin resistance. The locations of the enzymatic restriction sites, primers, and probes are also shown. D, southern blot of WT and four targeted mESC clones (named B-C06, B-C11, B-D05, and B-E02) with the cag probe shows correct homologous recombination at the 5’ side (upper panel) and 3’ side (lower panel) and single integration in all clones. The expected molecular weight bands for the targeted (T) allele are shown. E, PCR of WT and four targeted mESC clones shows insertion of the point mutation in all targeted clones. The expected molecular weight band for the targeted (T) allele is indicated. F, sequencing of genomic DNA from knock in OgaD285A/D285A and WT confirms the presence of single D285A point mutation (in red) in knock in animal. FRT, flippase recognition target; OGA, O-GlcNAcase.

OGA is indispensable for late embryonic development in mammals (19, 54). In two Oga KO (OgaKO) mouse models, embryos exhibited a reduction in size, and neonates died within 48 h after birth (19, 54). Although the precise causes of death remain unknown, the lethal phenotype was associated with abnormal lung histology marked with a reduction in prealveolar space in 18.5 dpc embryos (19), hypoglycemia, and impaired glycogen deposition in the liver of neonates (54). Mouse OgaKO studies using mouse embryonic fibroblasts or liver tissues from homozygous animals assigned these phenotypes to different cellular defects, specifically to mitotic abnormalities, cytokinesis failure (19), and altered metabolic signaling (54, 55). However, it remains unknown if these phenotypes are specifically because of the loss of OGA enzymatic activity or loss of the OGA protein.

To investigate the role of OGA catalytic activity in development and disease, we generated a knock-in Oga mouse model (OgaD285A), where a key residue for catalytic activity, D285, responsible for O-GlcNAc moiety binding and hydrolysis, is mutated to alanine (56). Therefore, the OgaD285A animals lack OGA activity while still expressing full-length OGA protein. This genetic strategy can model chronic inhibition of OGA activity in mouse, allowing the evaluation of the long-term effects of OGA inhibition and the investigation of the potential role of the HAT domain of OGA in vivo. We show that loss of OGA activity leads to perinatal lethality, organ defects, and tissue-specific disruption in O-GlcNAcylation homeostasis in embryos. These results highlight the essential role of the OGA domain during development independently of the HAT domain. Although the use of this model in adult animals is limited because of the lethality observed at the homozygous level, a similar strategy could be used to generate inducible mouse model carrying the OgaD285A mutation that will allow the future investigation of long-term adverse effects of prolonged OGA inhibition during adulthood in vivo.

Results

Loss of OGA catalytic activity leads to perinatal lethality

To dissect the role of OGA catalytic activity in mammalian development, we designed an Oga constitutive knock-in mouse model where OGA enzymatic activity is abolished (Fig. 1, A and B). Previous studies have shown that OGA Asp285 (D285) is essential for both O-GlcNAc hydrolysis and O-GlcNAc binding (56, 57, 58), whereas mutation to alanine causes nearly 100% loss of catalytic efficiency in vitro (59). We introduced the OGA D285A mutation into mESCs by homologous recombination (Fig. 1C). Correct single integration of the point mutation into mESCs was determined by Southern blotting (Fig. 1D) and PCR genotyping (Fig. 1E). Clones positive for the mutation were used for blastocyst injections to generate an OgaD285A mouse line lacking OGA enzymatic activity. DNA from positive offspring was sequenced to confirm the presence of the D285A mutation (Fig. 1F).

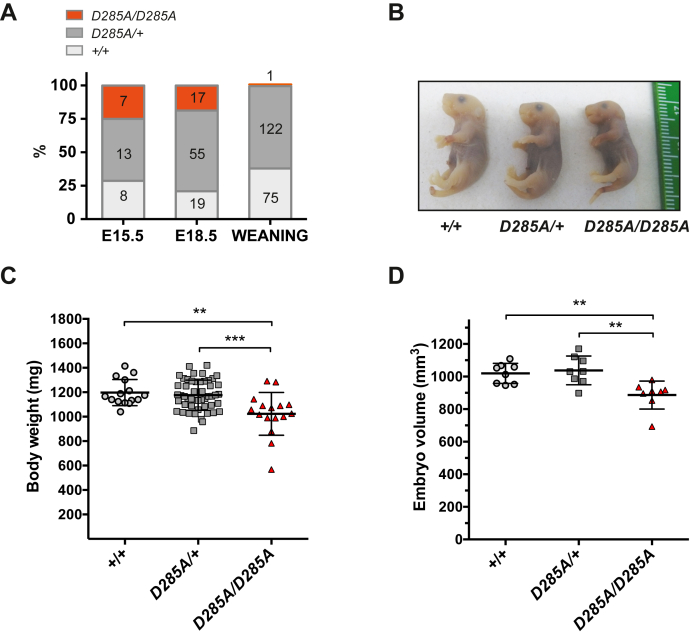

Previous studies have revealed that mice deficient in OGA protein (OgaKO) showed developmental delay and die perinatally (19, 54). Thus, we first tested the viability of homozygous OgaD285A animals by monitoring progeny of heterozygous breeding parents. No deviation from the expected Mendelian inheritance ratio of WT (25%), heterozygous (50%), and homozygous (25%) embryos at 15.5 and 18.5 dpc was observed, yet only a single homozygous animal (0.5% of 198 pups genotyped) survived to weaning stage (23–37 days after birth) (Fig. 2A). Homozygous OgaD285A embryos at 18.5 dpc showed no obvious anatomical defects, although they appeared smaller than their littermates (Fig. 2B). The weight and volume of homozygous OgaD285A 18.5 dpc embryos (weight: 1023 ± 175 mg, n = 15; volume: 887 ± 86 mm3, n = 8) were significantly reduced compared with WT (weight: 1197 ± 107.1 mg, n = 16; volume: 1020 ± 62 mm3, n = 8) and heterozygous embryos (weight: 1176 ± 124 mg, n = 50; volume: 1038 ± 88 mm3, n = 8) (Fig. 2, C and D). Taken together, these experiments show that catalytic deficiency of OGA leads to perinatal lethality and reduced growth.

Figure 2.

OgaD285A/D285Amice die perinatally.A, survival of OgaD285A/D285A animals compared with heterozygous and WT littermates at indicated time points. Numbers of each genotypes are shown on the graph. B, representative images of WT, heterozygous OgaD285A/+, and homozygous OgaD285A/D285A 18.5 dpc embryos. C, homozygous OgaD285A/D285A animals were markedly lighter (1023 ± 175 mg, n = 16) than their heterozygous OgaD285A/+ (1176 ± 124 mg, n = 50) and WT (1197 ± 107 mg, n = 15) littermates. Graph shows body weight of 18.5 dpc embryos of each genotype. Mean ± SD, ∗∗p = 0.001, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey's test. D, body volume of 18.5 dpc embryos of each genotype. Volumes of 18.5 dpc embryos were determined after microCT scan (n = 8). The OgaD285A/D285A animals were smaller (887 ± 86 mm3) than their heterozygous (1038 ± 88 mm3) and WT (1020 ± 62 mm3) littermates. (Oga+/+versus OgaD285A/D285A, ∗∗p = 0.008), (OgaD285A/+versus OgaD285A/D285A, ∗∗p = 0.003), one-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey's test.

O-GlcNAc homeostasis is altered in OgaD285A mice in a tissue-specific manner

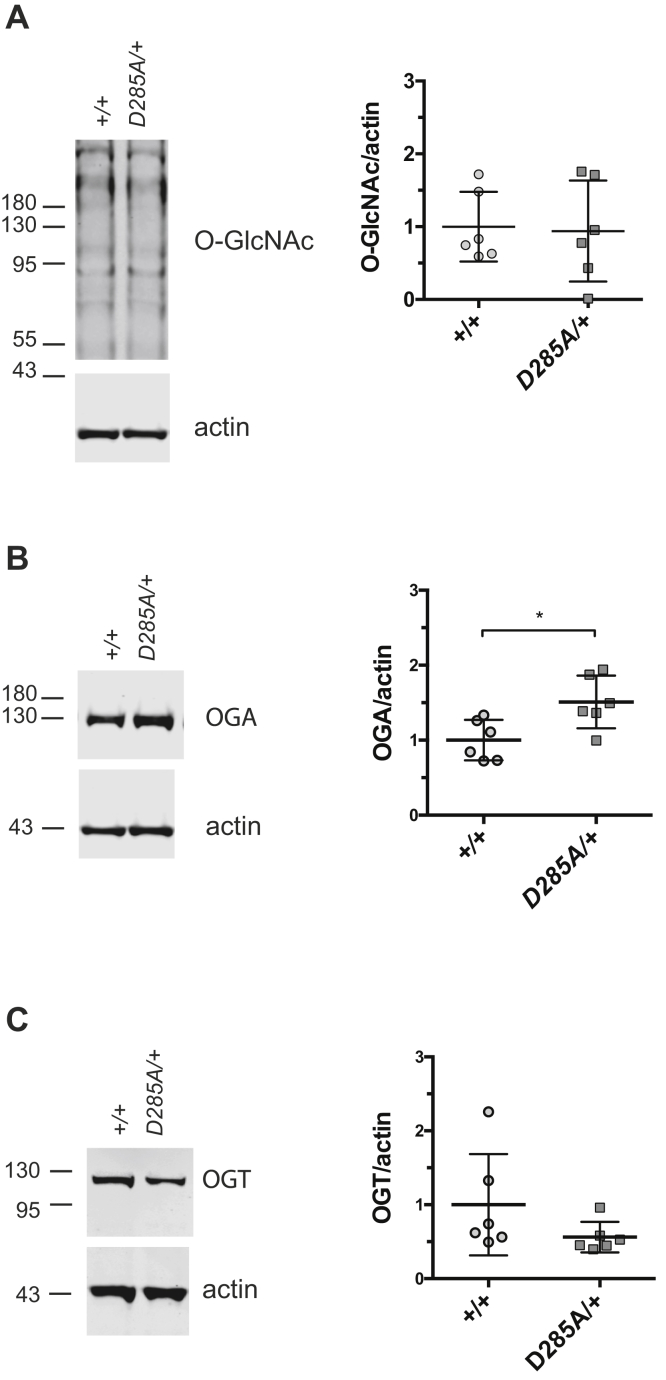

Although homozygous OgaD285A mice are not viable, the heterozygous OgaD285A/+ animals survived to adulthood. Previous studies have revealed increased protein O-GlcNAcylation in heterozygous OgaKO/+ hippocampus (29) and liver (54). We tested O-GlcNAc levels in the OgaD285A/+ mice to assess O-GlcNAc homeostasis. Mouse brain tissue obtained from 55- to 63-day-old WT and heterozygous OgaD285A/+ adult animals (n = 6 per group) were analyzed using an antibody specific for O-GlcNAcylated proteins. Protein O-GlcNAcylation was comparable in WT (mean ± SD fold change to WT, 1.1 ± 0.5 fold change) and heterozygous OgaD285A/+ samples (0.9 ± 0.7 fold change) (Fig. 3A). It has been established that OGT and OGA protein levels are sensitive to changes in protein O-GlcNAcylation in mammalian cells (34, 60). We next investigated such possible compensatory mechanisms by assessing OGA and OGT protein levels. Western blot revealed an increase of OGA protein level in heterozygous OgaD285A/+ animals (OGA: 1.5 ± 0.4 fold change) compared with WT animals (OGA: 1.0 ± 0.3 fold change). A decrease of OGT protein level in OgaD285A/+ (OGT: 0.6 ± 0.2 fold change) compared with WT (OGT: 1.0 ± 0.7 fold change) did not reach statistical significance (t test, p = 0.164). Our data indicate that heterozygous loss of OGA catalytic activity is compensated by altered OGA protein levels in adult heterozygous OgaD285A/+ animals to maintain normal level of protein O-GlcNAcylation (Fig. 3, B and C).

Figure 3.

O-GlcNAc levels are maintained in adult OgaD285A/+animals. Data were analyzed using unpaired t test, n = 6 for all genotypes. A, Western blot of adult brain samples probed with the RL2 monoclonal antibody raised against O-GlcNAc–modified nucleoporins and actin antibodies. Actin was used as a loading control. Quantification of O-GlcNAcylated proteins revealing no difference in adult heterozygous OgaD285A/+ animals compared with WT control (p = 0.865). B, Western blot probed with anti-OGA and actin antibodies. Quantification of OGA protein levels indicated that adult heterozygous OgaD285A/+ animals show an increase of OGA protein levels compared with WT control (∗p = 0.018). C, Western blot probed with anti-OGT and actin antibodies. Quantification of OGT protein levels reflecting no difference in adult heterozygous OgaD285A/+ animals compared with WT control (p = 0.164). OGA, O-GlcNAcase; OGT, O-GlcNAc transferase.

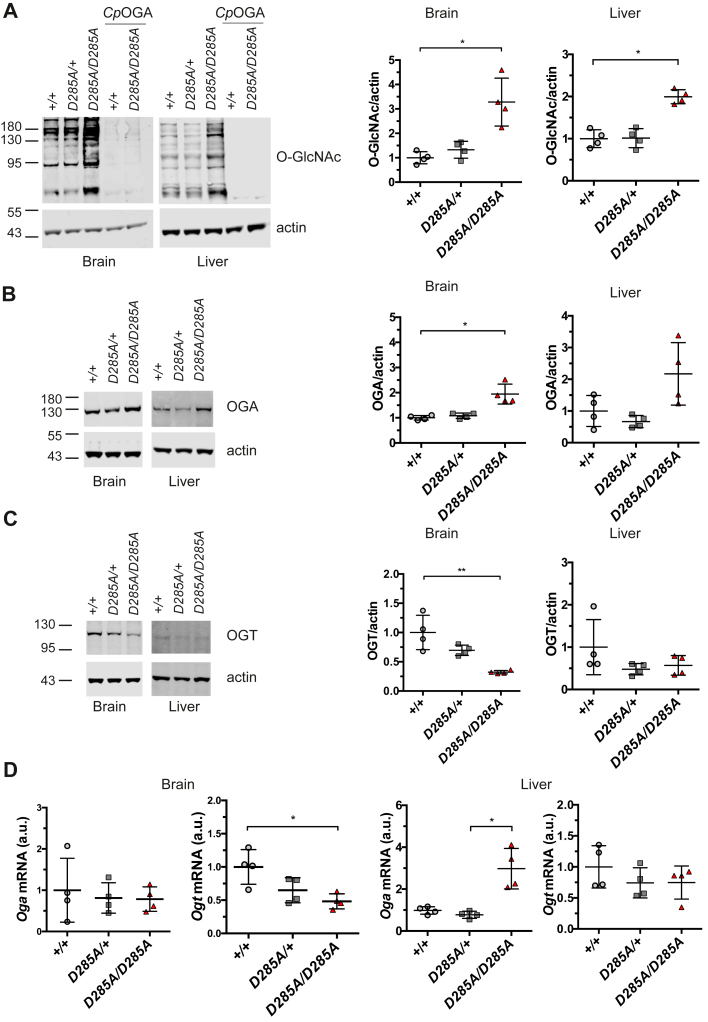

Next, we investigated the effect of the D285A mutation on protein O-GlcNAcylation in homozygous OgaD285A embryos. Previous mouse OgaKO studies showed global elevation of O-GlcNAc level defects in brain and liver (54, 55). Thus, brain and liver samples isolated from OgaD285A 15.5 dpc mouse embryos (n = 4 per group) were subjected to Western blotting. This revealed an increase of O-GlcNAcylation in brain tissues from homozygous OgaD285A/D285A embryos (3.3 ± 1.0 fold change), whereas O-GlcNAcylation levels were similar in WT (1.0 ± 0.2 fold change) and heterozygous OgaD285A/+ samples (1.3 ± 0.3 fold change) (Fig. 4A). Similarly, an increase of O-GlcNAc levels was observed in liver samples from homozygous OgaD285A/D285A embryos (2.0 ± 0.2 fold change), whereas O-GlcNAcylation was similar to WT level (1.0 ± 0.2 fold change) in heterozygous OgaD285A/+ liver samples (1.3 ± 0.2 fold change) (Fig. 4A). In the brain, a twofold increase of OGA protein levels and an approximately threefold reduction of OGT protein levels were detected in homozygous OgaD285A/D285A samples (OGA: 1.9 ± 0.4, OGT: 0.3 ± 0.03 fold change) compared with WT brain samples (Fig. 4, B and C). OGT and OGA protein levels appeared similar in WT samples (OGA: 1.0 ± 0.1, OGT: 1.0 ± 0.3 fold change) and heterozygous OgaD285A/+ samples (OGA: 1.1 ± 0.1, OGT: 0.7 ± 0.1 fold change). Next, we investigated Oga and Ogt mRNA levels. No detectable differences in brain Oga mRNA levels were observed between the three genotypes (Oga+/+: 1.0 ± 0.8, OgaD285A/+: 0.8 ± 0.4, and OgaD285A/D285A: 0.8 ± 0.3 fold change) (Fig. 4D). However, reductions of Ogt mRNA levels were apparent in homozygous OgaD285A/D285A (0.5 ± 0.1 fold change) and heterozygous OgaD285A/+ (0.6 ± 0.2 fold change) embryos, respectively, compared with WT samples (1.0 ± 0.3 fold change), although the differences between heterozygous and WT samples did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.35, Kruskal–Wallis multiple comparisons test) (Fig. 4D). In the embryo liver, an increase in OGA protein level was detected in homozygous OgaD285A/D285A samples (OGA: 2.2 ± 0.98) compared with WT liver samples. Although a reduction in OGT protein level (OGT: 0.6 ± 0.2) was apparent, the difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.51, Kruskal–Wallis multiple comparisons test). No difference in OGA and OGT protein levels was observed between heterozygous (OGA: 0.7 ± 0.2, OGT: 0.5 ± 1.1) and WT embryos (OGA: 1.0 ± 0.5, OGT: 1.0 ± 0.7) (Fig. 4, B and C). An increase of Oga mRNA levels was apparent in homozygous OgaD285A/D285A (3.0 ± 1.0) compared with WT samples (1.0 ± 0.2) and heterozygous OgaD285A/+ embryos (0.8 ± 0.2). No detectable differences in liver Ogt mRNA levels were observed between the three genotypes (Oga+/+: 1.0 ± 0.3, OgaD285A/+: 0.7 ± 0.2, and OgaD285A/D285A: 0.7 ± 0.3 fold change) (Fig. 4D). Taken together, these results suggest that loss of OGA catalytic activity leads to altered O-GlcNAc homeostasis in OgaD285A mice.

Figure 4.

O-GlcNAc homeostasis is altered in 15.5 dpc OgaD285A/D285Aembryos. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA with Kruskal–Wallis multiple comparisons test, n = 4 for all genotypes. A, western blot probed with the RL2 monoclonal antibody. The signal is specific to O-GlcNAc–modified proteins, as clostridium perfringens O-GlcNAcase treatment removed most of the signal. Quantification of O-GlcNAcylated proteins in brain and liver tissues revealing that homozygous OgaD285A/D285A embryos show increased O-GlcNAc levels compared with WT samples in both tissues (brain: 3.3-fold increase, ∗p = 0.018; liver: twofold increase, ∗p = 0.043) and heterozygous OgaD285A/+ samples (brain: 2.5-fold, p = 0.15; liver: twofold, p = 0.073). B, western blot probed with anti-OGA and actin antibodies. Quantification of OGA protein levels in brain and liver tissues indicates that homozygous OgaD285A/D285A samples have increased levels of OGA protein compared with WT control (brain: 1.9-fold increase, ∗p = 0.024; liver: 2.2-fold increase, p = 0.424) and heterozygous OgaD285A/+ samples (brain: 1.8-fold increase, p = 0.1186; liver: 3.3-fold increase, p = 0.056). C, western blot probed with anti-OGT and actin antibodies. Quantification of OGT protein levels in brain and tissues indicated that homozygous OgaD285A/D285A samples show a decrease in OGT protein levels compared with WT control (brain: threefold reduction, ∗∗p = 0.01; liver: twofold reduction, p = 0.51) and heterozygous OgaD285A/+ samples (brain: 2.2-fold reduction, p = 0.233; liver: 1.8-fold reduction, p > 0.999). D, quantification of Oga mRNA levels indicated no differences for all genotypes in the brain, whereas in the liver, Oga mRNA levels are increased in homozygous OgaD285A/D285A sample compared with WT control (threefold increase, p = 0.188) and heterozygous OgaD285A/+ samples (3.8-fold increase, ∗p = 0.013). Quantification of Ogt mRNA levels indicated that homozygous OgaD285A/D285A (twofold reduction, ∗p = 0.033) and heterozygous OgaD285A/+ (1.5-fold reduction, p = 0.35) samples show a decrease in Ogt mRNA levels compared with WT control in the brain, whereas no differences in Ogt mRNA levels were observed between all genotypes in the liver. OGA, O-GlcNAcase; OGT, O-GlcNAc transferase.

Microcomputed tomography reveals widespread organ defects in OgaD285A embryos

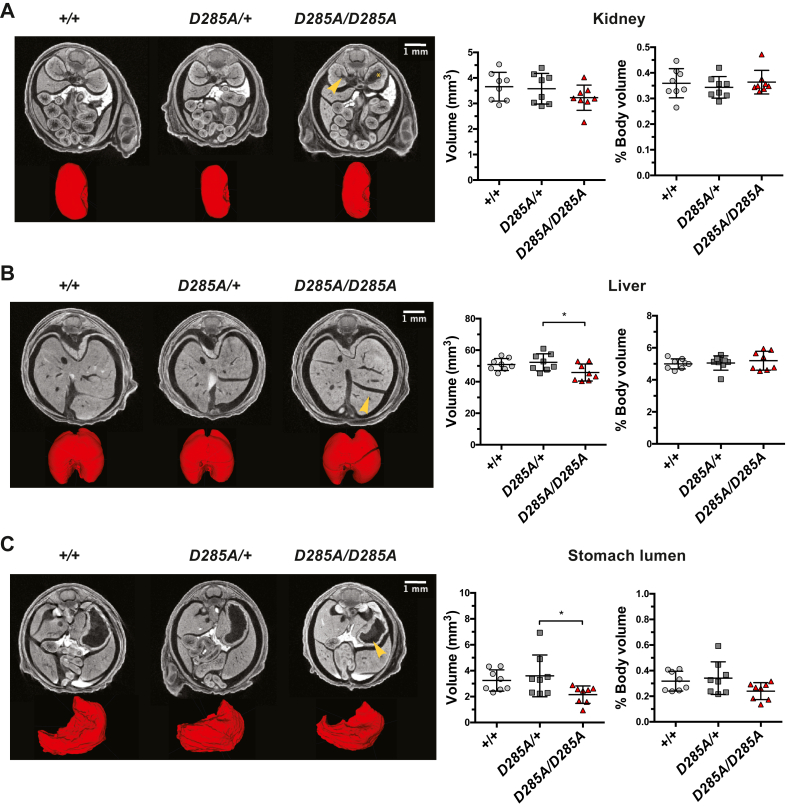

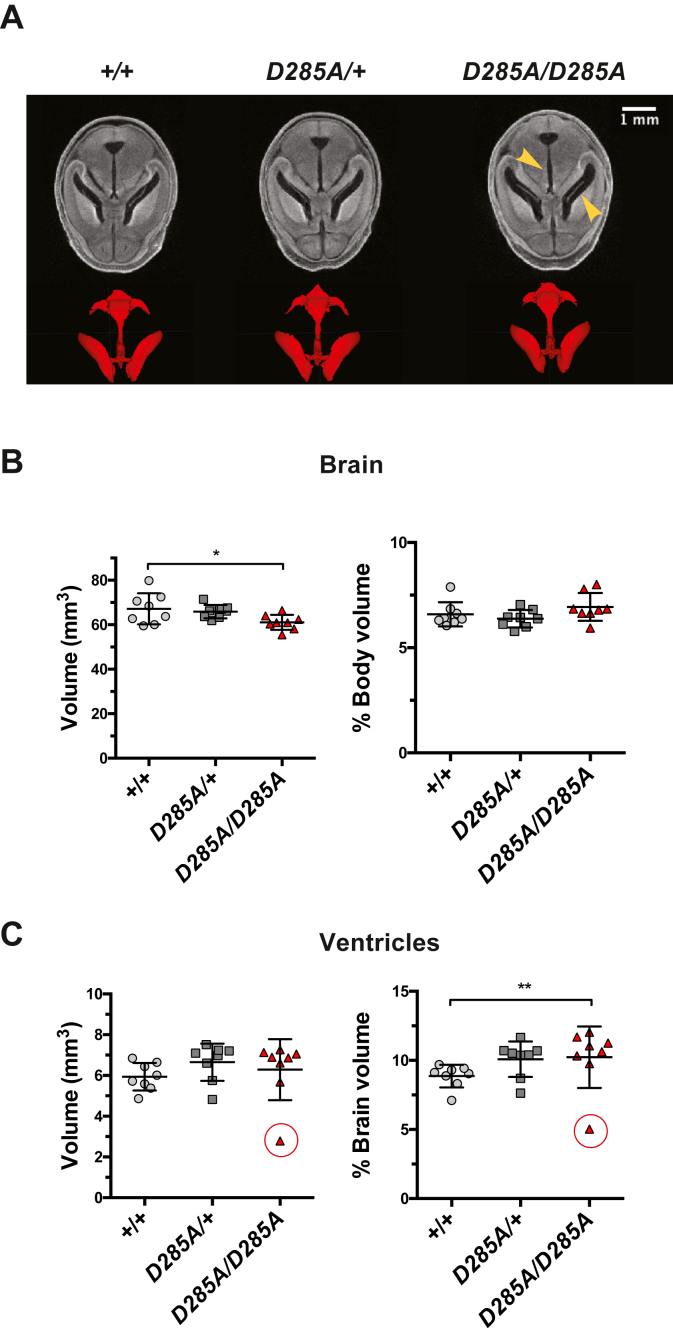

We next performed an unbiased in-depth analysis of growth and morphology on 18.5 dpc mouse embryos to identify organ defects that could explain perinatal lethality specific to loss of OGA catalytic activity. We employed X-ray microcomputed tomography (microCT) to capture the anatomy of intact whole embryos. In total, 70 anatomical structures were scored in WT, heterozygous, and homozygous embryos (n = 8 per group). Analysis of microCT imaging revealed anatomical abnormalities in 26 regions across all genotypes (Table S1). Two WT embryos showed a single abnormality, one in the brain and one in the heart. Three heterozygous OgaD285A/+ embryos exhibited morphological defects in eight regions, including heart, stomach, and kidney (Table S1). The majority of the abnormalities were observed in homozygous OgaD285A/D285A embryos with seven samples revealing defects in 21 areas (Table 1). For these regions, all WT Oga+/+ embryos appeared normal, whereas morphology of the stomach lumen (two cases) and kidney (one case) was affected in heterozygous OgaD285A/+ embryos. We decided to focus on essential organs that were affected in at least four OgaD285A/D285A samples, namely the kidneys, liver, stomach, and brain ventricles. Half of the embryos showed abnormalities in the kidneys exhibiting dilated renal pelvis that developed to advanced unilateral hydronephrosis in two OgaD285A/D285A embryos (Fig. 5A). Enlarged intralobular space in the liver was observed in 75% of OgaD285A/D285A animals, whereas in the two most severe cases, it was associated with reduced left/right and caudal lobes (Fig. 5B). The lumina of the stomach appeared reduced in half of the OgaD285A/D285A embryos (Fig. 5C). In addition, there were abnormalities in the fourth brain ventricles in five cases suggesting developmental defects in the brain (Fig. 6A).

Table 1.

List of abnormalities found in heterozygous OgaD285A/+ and homozygous OgaD285A/D285A embryos

|

The number of affected embryos (n = 8 per genotype) for each abnormality is reported. Green indicates no defects found, and yellow–red gradient indicates that abnormal features were detected.

Figure 5.

Microcomputed tomography (microCT) reveals widespread developmental defects in 18.5 dpc OgaD285Aembryos. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons test, n = 8 for all genotypes. The scale bars for the grayscale sections are represented. A, representative microCT images of axial sections of the abdomen region and 3D volume renderings of the right kidney (in red) from a WT, heterozygous OgaD285A/+, and homozygous OgaD285A/D285A 18.5 dpc embryos. The renal pelvis appeared dilated in the OgaD285A/D285A embryos (yellow arrow) and is associated with advanced unilateral hydronephrosis in two animals (yellow asterisk). Quantification of the volume of the right kidney showed no difference in kidney volume between all genotypes after normalization to whole embryo body. B, representative microCT images of axial sections and 3D volume renderings (in red) of the liver from a WT, heterozygous OgaD285A/+, and homozygous OgaD285A/D285A 18.5 dpc embryos. The intralobular spaces from the homozygous OgaD285A/D285A appeared enlarged as shown with yellow arrow compared with WT control. Quantification of the volume of the liver showed no difference in liver size between all genotypes after normalization to whole embryo body. C, representative microCT images of axial sections of the abdomen region and 3D volume renderings of the stomach lumen (in red) from WT, heterozygous OgaD285A/+, and homozygous OgaD285A/D285A 18.5 dpc embryos. The stomach lumen from the homozygous OgaD285A/D285A mice appeared reduced as shown with yellow arrow compared with WT and heterozygous OgaD285A/+ embryos. Quantification of the volume of the stomach lumen showed a possible reduced size of the lumen in homozygous OgaD285A/D285A compared with heterozygous OgaD285A/+ (p = 0.102) and WT (p = 0.243) embryos after normalization to whole embryo body although this did not reach statistical significance.

Figure 6.

OgaD285A/D285Aembryos show enlarged brain ventricles. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons test, n = 8 for all genotypes. The scale bars for the grayscale sections are represented. A, representative microcomputed tomography images of axial sections of the brain and 3D volume renderings of the ventricular system from a WT, heterozygous OgaD285A/+, and homozygous OgaD285A/D285A 18.5 dpc embryos. B, quantification of the volume of the brain showed no differences between all embryo genotypes after normalization to whole embryo body. C, quantification of the volume of the brain ventricles showing possible increases of the ventricular system in heterozygous OgaD285A/+ (p = 0.281) and homozygous OgaD285A/D285A embryos (p = 0.210) compared with WT control embryos after normalization to brain volume. A Dixon's Q test identified the smallest value (circled) in homozygous OgaD285A/D285A group as an outlier. Once this value is excluded from the analysis, the difference between OgaD285A/D285A and the WT control becomes statistically significant (∗∗p = 0.002) using one-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons test.

To explore possible volume differences in the affected organs, 3D segmentation was performed. We detected a reduction of volume for the liver, kidney, stomach lumen, and brain in the OgaD285A/D285A animals and an increase of volume in brain ventricles (Figs. 5 and 6). To compensate for the reduced body size of the OgaD285A/D285A animals, the volumes of these organs were then normalized to the volume of the whole embryo or to the volume of the brain in case of ventricle size analysis. No difference in kidney volume normalized to the embryo's whole-body volume was observed between genotypes (Oga+/+: 0.36 ± 0.06%, OgaD285A/+: 0.34 ± 0.04%, and OgaD285A/D285A: 0.36 ± 0.05% of whole-body volume) (Fig. 5A). Despite the apparent enlarged interlobular space, the relative size of the liver was not affected in OgaD285A/D285A mice (Oga+/+: 5.0 ± 0.3%, OgaD285A/+: 5.1 ± 0.4%, and OgaD285A/D285A: 5.2 ± 0.6% of whole-body volume) (Fig. 5B). However, a possible reduction in stomach lumina volume was observed in OgaD285A/D285A mice (Oga+/+: 0.32 ± 0.08%, OgaD285A/+: 0.34 ± 0.13%, and OgaD285A/D285A: 0.24 ± 0.07% of whole-body volume), although this did not reach statistical significance (Oga+/+ versus OgaD285A/D285A: p = 0.243) (Fig. 5C). Similarly, no difference in normalized brain volume was observed between genotypes (Oga+/+: 6.6 ± 0.6%, OgaD285A/+: 6.4 ± 0.4%, and OgaD285A/D285A: 6.9 ± 0.7% of whole-body volume) (Fig. 6B). These volumetric measurements suggested that the gross development of the liver, kidneys, stomach, and brain was proportional to the development of the whole in OgaD285A/D285A embryos. Next, we measured the volume of the brain ventricles, where a mild increase in OgaD285A/+ and OgaD285A/D285A embryos compared with WT animals was detected (Oga+/+: 8.8 ± 0.8%, OgaD285A/+: 9.8 ± 1.2%, and OgaD285A/D285A: 10.01 ± 2.4% of whole-brain volume), although the difference did not reach statistical significance (Oga+/+ versus OgaD285A/+: p = 0.281, Oga+/+ versus OgaD285A/D285A: p = 0.210) (Fig. 6C). In the OgaD285A/D285A group, one embryo showed very low ventricle volumes (circled value in Fig. 6C). This animal (identified as HOM1) appeared very small with a 24.1% reduction of body volume compared with the other OgaD285A/D285A embryos, and it displayed the most severe phenotypes within 16 anatomical regions (Table S1). This embryo also exhibited an overall underdeveloped state with reduced volume of the kidney, stomach, and brain. A Dixon's Q test on the ventricle unnormalized volume value of this embryo indicated that this data point may be considered as an outlier. Therefore, we performed the analysis on the data set where this embryo was excluded. Interestingly, the analysis indicated an enlargement of the brain ventricles in OgaD285A/D285A animals compared with WT animals with a difference reaching statistical significance (Oga+/+ versus OgaD285A/D285A: p = 0.002) suggesting abnormal neurodevelopment in OgaD285A/D285A embryos. Taken together, these results reveal widespread organ defects albeit with incomplete penetrance arisen in OgaD285A/D285A embryos as a consequence of catalytic deficiency of OGA.

Discussion

Previous studies have established that Oga is essential for mammalian development (19, 54). However, it is not known whether this is linked to OGA activity or functions of the other OGA domains. Similar to the OgaKO mouse models, the loss of OGA catalytic activity leads to reduced growth and perinatal lethality in our OGA catalytic-deficient model, suggesting that it is the loss of OGA enzymatic function that causes lethality and alteration in mouse embryonic development. In the OgaKO models, defects in lungs and liver tissues were observed in the homozygous embryos using classic histological techniques. Here, we used microCT to investigate whether other organ defects could arise from loss of OGA activity. We showed that OgaD285A/D285A pups, from the same mouse strain used for the OgaKO models, display various organ-specific defects with varying penetrance among the embryos that were not previously described. The most prominent abnormalities were found in the kidney exhibiting dilatation of the renal pelvis and advanced hydronephritis, the latter is associated with kidney infection and kidney failure (61) posing a significant risk of postnatal death (62). Defects in the liver, stomach, and brain were observed in parallel, and accumulation of abnormalities in several organs could contribute to perinatal lethality in the OgaD285A/D285A mice.

Loss of OGA activity resulted in increased global O-GlcNAc levels in homozygous OgaD285A/D285A embryos supporting that the D285A mutation impairs OGA activity in mouse. Increased protein O-GlcNAcylation has been associated with several chronic pathologies, including cancers, osteoarthritis, diabetes, diabetic vascular dysfunction, and diabetic nephropathy (63, 64, 65, 66, 67). Hyperglycemia is a hallmark of diabetes, and high glucose levels induce elevation of global O-GlcNAcylation by increased flux through the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway. Raised O-GlcNAc levels were found in tissues from diabetic animals and humans (68, 69, 70) as well as in pups of diabetic female mice (71). Several studies showed that O-GlcNAcylation contributes to hyperglycemia-induced tissue damage in heart and kidney of adult patients (69). Furthermore, maternal hyperglycemia causes developmental delay associated with congenital defects, also called as diabetic embryopathy, affecting the kidneys, central nervous system, heart, and skeletal system among others (72, 73). Inhibition of OGT blocked the negative impact of hyperglycemia or glucosamine supplementation on blastocyst formation, cell number, and apoptosis during mouse embryogenesis (74). Reduction of global O-GlcNAcylation through OGT inhibition in diabetic pregnant mice in vivo reduced neural tube defects in embryos (75). In our OgaD285A model, elevated O-GlcNAc levels independent of hyperglycemia were also associated with anomalies during mouse development, demonstrating a direct link between excess of O-GlcNAcylation and developmental defects.

Interestingly, we observed mild enlargement in the brain ventricles of both OgaD285A/+ and OgaD285A/D285A embryos indicating that the phenotypes observed previously in brain-specific OgaKO mice (55) are caused by the loss of catalytic activity of OGA. Ventricle enlargement, frequently associated with neurodevelopmental conditions including ID, originates from defects in neurogenesis, proliferation, or ciliary development (76, 77, 78). In the brain-specific OgaKO model, an imbalance between neuronal proliferation and disturbed neurogenesis was detected in neonates (55) that can be linked to hippocampal-dependent spatial learning and memory defects observed in adult heterozygous OgaKO/+−. A common hallmark in OGT-CDG mutations associated with ID is the reduction in OGA expression, suggesting a possible mechanism that might contribute in part to the pathogenesis of ID (30, 32, 33, 34, 35). Our model could be used to further examine the role of OGA and its activity in neurodevelopment and OGT-CDG pathogenesis.

Loss of OGA activity resulted in increased global O-GlcNAc levels accompanied with an increase in OGA protein levels and a decrease in OGT protein levels, providing further evidence for a compensatory molecular response to maintain O-GlcNAc homeostasis in the brain in both OgaD285A/+ adults and OgaD285A/D285A embryos. Although similar upregulation was observed for O-GlcNAc and OGA levels in the liver of embryos, OGT expression remained unchanged suggesting a tissue-specific response. Previous reports have shown that pharmacological inhibition of OGA activity led to an increase of Oga mRNA expression and OGA protein levels (60, 79, 80). Similarly, we detected increased Oga mRNA and OGA protein levels in liver samples from OgaD285A/D285A embryos. The primer set used to detect Oga mRNA levels flank exon 1, allowing the evaluation of mature Oga mRNA levels. The data suggest that transcriptional upregulation of Oga mRNA levels occurs to produce more proteins to compensate for loss of catalytic activity. However, the levels of Oga mRNA remained unchanged in the brain of OgaD285A/D285A embryos suggesting that OGA regulation in this tissue may occur at the post-transcriptional level. Interestingly, OGA is itself O-GlcNAcylated, which could provide a mechanism for such post-transcriptional regulation (81, 82).

The levels of OGT protein were reduced in the brain. Similarly, OGT protein levels were found decreased in association with reduction of OGA protein expression in models of two OGT-CDG mutations (32, 33). We showed that reduction of OGT protein levels was also associated with a reduction of Ogt mRNA levels. Taken together, these data indicate possible transcriptional control of OGT expression influenced by OGA activity. OGA-mediated regulation of Ogt transcription through cooperation with the HAT p300 and transcription factor CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein β has been described in vitro in WT primary mouse hepatocytes (83). In addition, elevated O-GlcNAc because of pharmacological inhibition of OGA promotes the retention of Ogt RNA intron 4 through the Ogt intronic splicing silencer leading to Ogt mRNA degradation (84). The primer set we used to evaluate the levels of Ogt mRNA levels flank exons 4/5, allowing the detection of the mature form of Ogt mRNA (85). Further experiments will be needed to evaluate whether the reduction of mature Ogt mRNA levels we observed in the brain is due to less Ogt mRNA produced or because of an increase in intronic retention leading to Ogt mRNA degradation. Together with our data, these studies suggest that loss of OGA activity induces alteration of Ogt transcription to maintain in vivo O-GlcNAc homeostasis in the brain but not in the liver during gestation. Although the precise mechanisms associated with OGA/OGT regulation in the OgaD285A mice remain to be explored, our results indicate that mechanisms for O-GlcNAc homeostasis maintenance may differ from one tissue to another or only occur in some tissues. A similar strategy could be used to generate a mouse model carrying an inducible OgaD285A allele to investigate the physiological consequences of prolonged OGA inhibition during adulthood.

A number of studies suggest that elevation of O-GlcNAcylation through pharmacological inhibition of OGA could provide therapeutic benefit for chronic neurological conditions, such as temporal lobe epilepsy (86), AD (44, 45, 46, 47), and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (87). The degree of OGA inhibition needed to achieve the desired biological response while minimizing any potential side effects is an important consideration. In the brain, at least 80% of OGA inhibition is necessary to achieve global protein O-GlcNAcylation elevation in vivo (44). This is in accordance with our results showing that heterozygous OgaD285A/+ mice displayed unchanged global O-GlcNAc levels. Although heterozygous OgaD285A/+ mice are viable and do not develop overt developmental phenotypes, complete loss of OGA activity in homozygous OgaD285A/D285A mice led to elevated O-GlcNAc levels, perinatal lethality, and abnormal development. The phenotypes observed in the OgaD285A/D285A mice suggest the possibility of adverse on-target side effects upon prolonged inhibition of OGA. Although the use of adult and embryo tissues is a different context and no apparent toxic effects have been reported to date because of prolonged exposure of OGA inhibitors in adult animals, the investigations are mainly limited to the brain (44, 47, 88), and the effects of long-term OGA inhibition in other tissues remain unclear.

Two splice variants of human OGA exist: (1) a full-length nucleocytoplasmic isoform that contains the N-terminal glycoside hydrolase domain together with the C-terminal HAT domain and (2) a short nuclear isoform that lacks the HAT domain and shows lower OGA activity compared with the full-length isoform (89, 90). OGA undergoes caspase-3 cleavage giving rise to two fragments that individually lack OGA catalytic activity. However, the two fragments can reassemble and restore fully functional OGA in cells (51). This suggests that the C-terminal part of OGA that includes the HAT domain may be important for catalytic activity. Although it remains unknown whether this domain possesses any additional functions, phenotypic comparison of OgaD285A and OgaKO mouse models reveals that the OGA domain is essential for late embryonic development and perinatal survival.

In summary, we generated a mouse model lacking OGA catalytic activity, providing a genetic model for prolonged inhibition of OGA in vivo. This model will be useful to study the role of O-GlcNAcylation in development and to understand the potential function of the noncatalytic OGA domains. We showed that loss of OGA activity leads to perinatal lethality, organ defects, and tissue-specific disruption in O-GlcNAcylation homeostasis in mice.

Experimental procedures

Generation of OgaD285A knock-in mice

OgaD285A knock-in (C57BL/6NTac-Mgea5tm3592(D285A)Arte) mice were generated by Taconic Artemis GmbH via insertion of the constitutive knock-in allele and subsequent Flpe-mediated deletion of a puromycin resistance cassette (Fig. 1C). First, OgaD285A mESCs were created via insertion of the knock-in allele via homologous recombination in C57BL/6NTac (Art B6 3.6) mESCs. The targeting vector coding for a ∼10-kb-sequence spanning exon 4 to 8 of the Oga gene was electroporated into mESCs. The construct also contained a flippase recognition target–flanked puromycin resistance cassette in the intronic region between intron 6 and 7 allowing for subsequent isolation of recombinant clones (Fig. 1C). Correct homologous recombination and single integration at both 5’ and 3’ sides in mESCs clones was validated using the cag probe that detects a region located within the puromycin selection cassette. The genomic DNA was digested with either SphI for the 5’ side or EcoRV for the 3’ side and analyzed by Southern blot. The presence of the D285A mutation and the single integration was determined by PCR using 10328_1 and 10328_2 primers followed by sequencing using the 10610_135 primer.

Then, 10 to 15 cells from three selected mESC colonies bearing the D285A mutation were injected into 3.5-days blastocysts from BALB/c female mice (BALB/cAnNTac; Taconic Artemis GmbH) in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 15% fetal calf serum under mineral oil. After recovery, 48 to 51 blastocysts were transplanted into nine pseudopregnant NMRI females (BomTac:NMRI; Taconic Artemis GmbH). Ten highly chimeric progenies (>50%) were selected based on their coat color and bred with flippase (Flp) deleter C57BL/6 mice (C57BL/6-Tg(CAG-Flpe)2Arte; Taconic Artemis GmbH) to eliminate the puromycin cassette. Eight pups heterozygous for the D285A mutation were used as colony founders. Primers used for genotyping and validation are listed in Table S2.

Animal husbandry and genotyping

Founder OgaD285A/+ heterozygous mice were crossed to C57BL/6J WT animals (Charles River UK Limited) inhouse. The line was initially bred by intercrossing heterozygous animals, then maintained by backcrossing to C57BL/6J background for two generations. Animals were housed in standard holding cages with water and food available ad libitum and 12/12 h light/dark cycles throughout the study. All animal studies and breeding were performed in accordance with the Animal (Scientific Procedures) Act of 1986 for the care and use of laboratory animals. Procedures were carried under United Kingdom Home Office Regulation with approval by the Welfare and Ethical Use of Animals Committee of University of Dundee.

Genotyping was performed by diagnostic PCR using Thermococcus kodakaraensis Hot Start DNA polymerase (EMD Millipore) on genomic DNA isolated from ear-notch biopsy with 10609_129 and 10609_130 primers (Table S2) that amplified 395 base pair fragment of the knock-in and 320 base pair fragment of the WT allele. Animals were genotyped after weaning at 23 to 37 days old.

Weight measurement

Weights of the embryos were determined after fixation on analytical scale. Excess liquid from the surface of the embryos was removed with paper towels prior to measurement. Statistical significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test.

Western blotting

Tissues were rapidly dissected, rinsed in cold PBS, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C. For immunoblotting, tissue was lysed in 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.4), 0.1 mM EGTA, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 50 mM sodium fluoride, 5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 0.27 M sucrose, 0.1% 2-mercaptoethanol supplemented with protease inhibitors (1 mM benzamidine, 0.2 mM PMSF, and 5 μM leupeptin), and 10 μM GlcNAcstatin G. Lysates were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 20 min at 4 °C, and the protein concentration was determined with Pierce 660 nm protein assay (Thermo Scientific). About 20 to 30 μg of protein was denatured in SDS loading buffer containing 1% 2-mercaptoethanol. Proteins were separated on precast 4 to 12% NuPAGE Bis–Tris Acrylamide gels (Invitrogen) and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. Membranes were incubated with primary antibodies in blocking buffer and 5% bovine serum albumin in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween-20 overnight at 4 °C. Anti-OGA (1:500 dilution; catalog no. HPA036141; Sigma), anti-O-GlcNAc (RL2) (1:500 dilution; NB300-524, Lot# A-2; Novus Biologicals), anti-OGT (F-12) (1:1000 dilution; sc-74546; Santa Cruz), and antiactin (1:2000 dilution; A2066; Sigma) antibodies were used. Next, the membranes were incubated with IR680/800-labeled secondary antibodies (Licor) at room temperature for 1 h. Blots were imaged using a Li-Cor Odyssey infrared imaging system (Li-Cor), and signals were quantified using Image Studio Lite software (Licor). Results were normalized to the mean of each corresponding WT replicates set and represented as a fold change relative to WT. Significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons test or Student's t test.

CpOGA treatment

Mouse embryo brain and liver lysates lacking GlcNAcstatin G were treated with recombinant clostridium perfringens O-GlcNAcase (CpOGA) to test the specificity of the anti-O-GlcNAc antibody (RL2). Recombinant glutathione-S-transferase–tagged CpOGA was expressed and purified as described earlier (91). Lysates containing 60 μg protein at 0.85 μg/ml concentration were incubated with 10 μg recombinant WT CpOGA for 60 min at 30 °C. The reaction was stopped by addition of SDS loading buffer containing 1% 2-mercaptoethanol and boiling the samples for 5 min.

Real-time quantitative PCR

Total RNA was purified using RNAeasy Kit (Qiagen), and then 1000 ng of sample RNA was used for reverse transcription with the qScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Quantabio). Quantitative PCR reactions were performed using the PerfeCTa SYBR Green FastMix for iQ (Quantabio) reagent, in the CFX Connect Real-Time PCR Detection System (BioRad), employing a thermocycle of one cycle at 95 °C for 30 s and then 40 cycles at 95 °C for 5 s, 60 °C for 15 s, and 68 °C for 10 s. Data analysis was performed using CFX Manager software (BioRad). Samples were assayed in biological quadruplicates with technical triplicates using the comparative Ct method. The threshold-crossing value was normalized to internal control transcripts (Gapdh, Actb, and Pgk1). Primers used are listed in Table S3. Results were normalized to the mean of each corresponding WT replicates set and represented as a fold change relative to WT. Statistical significance was evaluated using one-way ANOVA with Kruskal–Wallis multiple comparisons test on ΔCt values obtained for each biological replicate.

Sample preparation and imaging parameters for X-ray microCT

Crosses between heterozygous OgaD285A/+ female and OgaD285A/+ male mice were set up, and plug formation in the females was monitored to determine day 0.5 after fertilization. Pregnant females were sacrificed 18 days after plug formation with increasing concentration of carbon dioxide, and the femoral artery was severed. Embryos of 18.5 dpc were dissected into 6-well plate containing ice-cold PBS (pH 8). Embryos were washed twice with ice-cold PBS, and small tail samples were collected for genotyping. Embryos were fixed in ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffer solution for 7 days on roller at 4 °C. Fixed embryos were stored in 1% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffer until shipment and further processing. At MRC Harwell, samples were rinsed in distilled water, then placed in ∼15 ml 50% Lugol's solution prepared in MilliQ distilled water, and kept at room temperature on the rocker, in vials wrapped in tinfoil. About 50% Lugol's solution was changed every other day for 14 days to achieve contrasting. Embryos were rinsed with MilliQ distilled water for a minimum of 1 h before they were embedded in 1% w/v Iberose-High Specification Agarose (AGR-500) made in MilliQ distilled water and left at room temperature to set for 2 h. 3D imaging of samples was performed using a Skyscan 1172 microCT scanner (Bruker) with aluminium filter setting, scanning with 70 kV, the image pixel size set to 5 μm, employing a rotation step 0.25° while achieving 180° rotation along the anterior–posterior axis.

Image processing

Acquired images were reconstructed using NRecon Reconstruction (Bruker) software. Data were further cropped, and TIFF stacks were generated using Harwell Automated Recon Processor (HARP; Harwell) software. Image series were converted into .nrrd file format and viewed using open-source Fiji-based 3D Viewer and on 3D Slicer (version 4.10.1; https://www.slicer.org/), an open-source medical image processing and visualization system. Segmentation and 3D volume rendering for detailed morphological analysis were performed with the ITK-SNAP medical image segmentation tool (version 3.6.0 (92)). To eliminate bias, image stacks were renamed, and the genotype was blinded for the analysis. Statistical significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons test. The Dixon's Q test was performed for outlier identification in the sample groups according to Rorabacher (93). The experimental Q value (Qexp) was calculated from raw data using Qexp = (x2 − x1)/(xn − x1), where x1 is the value of interest, x2, the closest value to x1 in the data set, and xn the highest value in the data set. Qexp was next compared with the Q critical value (Qcrit) of 0.526 for n = 8 for a confidence level of 95% using the Q-table. Data that displayed a Qexp higher than the Qcrit of 0.526 were considered as an outlier at a confidence level of 95%.

Data availability

All data are contained in the article.

Supporting information

This article contains supporting information.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank our departmental support teams for their assistance (Medical Research Council Genotyping and Tissue Culture teams) and the School of Life Sciences Biological Services (all resource units) for the essential management, maintenance, and husbandry of mice. We thank Olawale Raimi for expressing and purifying clostridium perfringens O-GlcNAcase reagent and Andrew T. Ferenbach for assistance with sequencing data and molecular reagents.

Author contributions

V. M. and D. M. F. v. A. conceived the study; V. M. and F. A. performed experiments and analyzed data; Z. S.-K., L. T., and S. J. collected microCT data and assisted with data analysis; A. M., J. G., and R. J. M. assisted with mouse husbandry and sample collection; and V. M., F. A., and D. M. F. v. A. interpreted the data and wrote the article with input from all authors.

Funding and additional information

This work was funded by a Wellcome Trust Investigator Award (110061) to D. M. F. v. A.

Edited by Gerald Hart

Supporting information

References

- 1.Zhu Y., Liu T.W., Cecioni S., Eskandari R., Zandberg W.F., Vocadlo D.J. O-GlcNAc occurs cotranslationally to stabilize nascent polypeptide chains. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2015;11:319–325. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chu C.S., Lo P.W., Yeh Y.H., Hsu P.H., Peng S.H., Teng Y.C., Kang M.L., Wong C.H., Juan L.J. O-GlcNAcylation regulates EZH2 protein stability and function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014;111:1355–1360. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323226111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gambetta M.C., Muller J. O-GlcNAcylation prevents aggregation of the Polycomb group repressor polyhomeotic. Dev. Cell. 2014;31:629–639. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skorobogatko Y., Landicho A., Chalkley R.J., Kossenkov A.V., Gallo G., Vosseller K. O-linked beta-N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc) site thr-87 regulates synapsin I localization to synapses and size of the reserve pool of synaptic vesicles. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:3602–3612. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.512814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peng C., Zhu Y., Zhang W., Liao Q., Chen Y., Zhao X., Guo Q., Shen P., Zhen B., Qian X., Yang D., Zhang J.S., Xiao D., Qin W., Pei H. Regulation of the hippo-YAP pathway by glucose sensor O-GlcNAcylation. Mol. Cell. 2017;68:591–604.e595. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Constable S., Lim J.M., Vaidyanathan K., Wells L. O-GlcNAc transferase regulates transcriptional activity of human Oct4. Glycobiology. 2017;27:927–937. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwx055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lamarre-Vincent N., Hsieh-Wilson L.C. Dynamic glycosylation of the transcription factor CREB: A potential role in gene regulation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:6612–6613. doi: 10.1021/ja028200t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ranuncolo S.M., Ghosh S., Hanover J.A., Hart G.W., Lewis B.A. Evidence of the involvement of O-GlcNAc-modified human RNA polymerase II CTD in transcription in vitro and in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:23549–23561. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.330910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deplus R., Delatte B., Schwinn M.K., Defrance M., Mendez J., Murphy N., Dawson M.A., Volkmar M., Putmans P., Calonne E., Shih A.H., Levine R.L., Bernard O., Mercher T., Solary E. TET2 and TET3 regulate GlcNAcylation and H3K4 methylation through OGT and SET1/COMPASS. EMBO J. 2013;32:645–655. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andres L.M., Blong I.W., Evans A.C., Rumachik N.G., Yamaguchi T., Pham N.D., Thompson P., Kohler J.J., Bertozzi C.R. Chemical modulation of protein O-GlcNAcylation via OGT inhibition promotes human neural cell differentiation. ACS Chem. Biol. 2017;12:2030–2039. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.7b00232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jang H., Kim T.W., Yoon S., Choi S.Y., Kang T.W., Kim S.Y., Kwon Y.W., Cho E.J., Youn H.D. O-GlcNAc regulates pluripotency and reprogramming by directly acting on core components of the pluripotency network. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11:62–74. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swamy M., Pathak S., Grzes K.M., Damerow S., Sinclair L.V., van Aalten D.M., Cantrell D.A. Glucose and glutamine fuel protein O-GlcNAcylation to control T cell self-renewal and malignancy. Nat. Immunol. 2016;17:712–720. doi: 10.1038/ni.3439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kreppel L.K., Blomberg M.A., Hart G.W. Dynamic glycosylation of nuclear and cytosolic proteins. Cloning and characterization of a unique O-GlcNAc transferase with multiple tetratricopeptide repeats. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:9308–9315. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.14.9308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dong D.L., Hart G.W. Purification and characterization of an O-GlcNAc selective N-acetyl-beta-D-glucosaminidase from rat spleen cytosol. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:19321–19330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ingham P.W. A gene that regulates the bithorax complex differentially in larval and adult cells of Drosophila. Cell. 1984;37:815–823. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90416-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mariappa D., Selvan N., Borodkin V., Alonso J., Ferenbach A.T., Shepherd C., Navratilova I.H., van Aalten D.M.F. A mutant O-GlcNAcase as a probe to reveal global dynamics of protein O-GlcNAcylation during Drosophila embryonic development. Biochem. J. 2015;470:255–262. doi: 10.1042/BJ20150610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Webster D.M., Teo C.F., Sun Y., Wloga D., Gay S., Klonowski K.D., Wells L., Dougan S.T. O-GlcNAc modifications regulate cell survival and epiboly during zebrafish development. BMC Dev. Biol. 2009;9:28. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-9-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Donnell N., Zachara N.E., Hart G.W., Marth J.D. Ogt-dependent X-chromosome-linked protein glycosylation is a requisite modification in somatic cell function and embryo viability. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:1680–1690. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.4.1680-1690.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang Y.R., Song M., Lee H., Jeon Y., Choi E.J., Jang H.J., Moon H.Y., Byun H.Y., Kim E.K., Kim D.H., Lee M.N., Koh A., Ghim J., Choi J.H., Lee-Kwon W. O-GlcNAcase is essential for embryonic development and maintenance of genomic stability. Aging Cell. 2012;11:439–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2012.00801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keembiyehetty C. Disruption of O-GlcNAc cycling by deletion of O-GlcNAcase (Oga/Mgea5) changed gene expression pattern in mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) cells. Genom. Data. 2015;5:30–33. doi: 10.1016/j.gdata.2015.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim H.S., Park S.Y., Choi Y.R., Kang J.G., Joo H.J., Moon W.K., Cho J.W. Excessive O-GlcNAcylation of proteins suppresses spontaneous cardiogenesis in ES cells. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:2474–2478. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ishihara K., Takahashi I., Tsuchiya Y., Hasegawa M., Kamemura K. Characteristic increase in nucleocytoplasmic protein glycosylation by O-GlcNAc in 3T3-L1 adipocyte differentiation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010;398:489–494. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.06.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andres-Bergos J., Tardio L., Larranaga-Vera A., Gomez R., Herrero-Beaumont G., Largo R. The increase in O-linked N-acetylglucosamine protein modification stimulates chondrogenic differentiation both in vitro and in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:33615–33628. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.354241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu K., Paterson A.J., Zhang F., McAndrew J., Fukuchi K., Wyss J.M., Peng L., Hu Y., Kudlow J.E. Accumulation of protein O-GlcNAc modification inhibits proteasomes in the brain and coincides with neuronal apoptosis in brain areas with high O-GlcNAc metabolism. J. Neurochem. 2004;89:1044–1055. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cole R.N., Hart G.W. Cytosolic O-glycosylation is abundant in nerve terminals. J. Neurochem. 2001;79:1080–1089. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vosseller K., Trinidad J.C., Chalkley R.J., Specht C.G., Thalhammer A., Lynn A.J., Snedecor J.O., Guan S., Medzihradszky K.F., Maltby D.A., Schoepfer R., Burlingame A.L. O-linked N-acetylglucosamine proteomics of postsynaptic density preparations using lectin weak affinity chromatography and mass spectrometry. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2006;5:923–934. doi: 10.1074/mcp.T500040-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Francisco H., Kollins K., Varghis N., Vocadlo D., Vosseller K., Gallo G. O-GLcNAc post-translational modifications regulate the entry of neurons into an axon branching program. Dev. Neurobiol. 2009;69:162–173. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lagerlof O., Hart G.W., Huganir R.L. O-GlcNAc transferase regulates excitatory synapse maturity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2017;114:1684–1689. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1621367114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang Y.R., Song S., Hwang H., Jung J.H., Kim S.J., Yoon S., Hur J.H., Park J.I., Lee C., Nam D., Seo Y.K., Kim J.H., Rhim H., Suh P.G. Memory and synaptic plasticity are impaired by dysregulated hippocampal O-GlcNAcylation. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:44921. doi: 10.1038/srep44921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pravata V.M., Omelkova M., Stavridis M.P., Desbiens C.M., Stephen H.M., Lefeber D.J., Gecz J., Gundogdu M., Ounap K., Joss S., Schwartz C.E., Wells L., van Aalten D.M.F. An intellectual disability syndrome with single-nucleotide variants in O-GlcNAc transferase. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2020;28:706–714. doi: 10.1038/s41431-020-0589-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shaffer L.G., American College of Medical Genetics Professional Practice. Guidelines Committee American College of Medical Genetics guideline on the cytogenetic evaluation of the individual with developmental delay or mental retardation. Genet. Med. 2005;7:650–654. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000186545.83160.1e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Willems A.P., Gundogdu M., Kempers M.J.E., Giltay J.C., Pfundt R., Elferink M., Loza B.F., Fuijkschot J., Ferenbach A.T., van Gassen K.L.I., van Aalten D.M.F., Lefeber D.J. Mutations in N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc) transferase in patients with X-linked intellectual disability. J. Biol. Chem. 2017;292:12621–12631. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.790097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vaidyanathan K., Niranjan T., Selvan N., Teo C.F., May M., Patel S., Weatherly B., Skinner C., Opitz J., Carey J., Viskochil D., Gecz J., Shaw M., Peng Y., Alexov E. Identification and characterization of a missense mutation in the O-linked beta-N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc) transferase gene that segregates with X-linked intellectual disability. J. Biol. Chem. 2017;292:8948–8963. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.771030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pravata V.M., Gundogdu M., Bartual S.G., Ferenbach A.T., Stavridis M., Ounap K., Pajusalu S., Zordania R., Wojcik M.H., van Aalten D.M.F. A missense mutation in the catalytic domain of O-GlcNAc transferase links perturbations in protein O-GlcNAcylation to X-linked intellectual disability. FEBS Lett. 2019;594:717–727. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.13640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pravata V.M., Muha V., Gundogdu M., Ferenbach A.T., Kakade P.S., Vandadi V., Wilmes A.C., Borodkin V.S., Joss S., Stavridis M.P., van Aalten D.M.F. Catalytic deficiency of O-GlcNAc transferase leads to X-linked intellectual disability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2019;116:14961–14970. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1900065116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muha V., Fenckova M., Ferenbach A.T., Catinozzi M., Eidhof I., Storkebaum E., Schenck A., van Aalten D.M.F. O-GlcNAcase contributes to cognitive function in Drosophila. J. Biol. Chem. 2020;295:8636–8646. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA119.010312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Savage J.E., Jansen P.R., Stringer S., Watanabe K., Bryois J., de Leeuw C.A., Nagel M., Awasthi S., Barr P.B., Coleman J.R.I., Grasby K.L., Hammerschlag A.R., Kaminski J.A., Karlsson R., Krapohl E. Genome-wide association meta-analysis in 269,867 individuals identifies new genetic and functional links to intelligence. Nat. Genet. 2018;50:912–919. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0152-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wani W.Y., Ouyang X., Benavides G.A., Redmann M., Cofield S.S., Shacka J.J., Chatham J.C., Darley-Usmar V., Zhang J. O-GlcNAc regulation of autophagy and alpha-synuclein homeostasis; implications for Parkinson's disease. Mol. Brain. 2017;10:32. doi: 10.1186/s13041-017-0311-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu F., Iqbal K., Grundke-Iqbal I., Hart G.W., Gong C.X. O-GlcNAcylation regulates phosphorylation of tau: A mechanism involved in Alzheimer's disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:10804–10809. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400348101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ryan P., Xu M., Davey A.K., Danon J.J., Mellick G.D., Kassiou M., Rudrawar S. O-GlcNAc modification protects against protein misfolding and aggregation in neurodegenerative disease. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2019;10:2209–2221. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.9b00143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang A.C., Jensen E.H., Rexach J.E., Vinters H.V., Hsieh-Wilson L.C. Loss of O-GlcNAc glycosylation in forebrain excitatory neurons induces neurodegeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016;113:15120–15125. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1606899113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marotta N.P., Lin Y.H., Lewis Y.E., Ambroso M.R., Zaro B.W., Roth M.T., Arnold D.B., Langen R., Pratt M.R. O-GlcNAc modification blocks the aggregation and toxicity of the protein alpha-synuclein associated with Parkinson's disease. Nat. Chem. 2015;7:913–920. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yanagisawa M., Yu R.K. O-linked beta-N-acetylglucosaminylation in mouse embryonic neural precursor cells. J. Neurosci. Res. 2009;87:3535–3545. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hastings N.B., Wang X., Song L., Butts B.D., Grotz D., Hargreaves R., Fred Hess J., Hong K.K., Huang C.R., Hyde L., Laverty M., Lee J., Levitan D., Lu S.X., Maguire M. Inhibition of O-GlcNAcase leads to elevation of O-GlcNAc tau and reduction of tauopathy and cerebrospinal fluid tau in rTg4510 mice. Mol. Neurodegener. 2017;12:39. doi: 10.1186/s13024-017-0181-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yuzwa S.A., Shan X., Macauley M.S., Clark T., Skorobogatko Y., Vosseller K., Vocadlo D.J. Increasing O-GlcNAc slows neurodegeneration and stabilizes tau against aggregation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2012;8:393–399. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yuzwa S.A., Shan X., Jones B.A., Zhao G., Woodward M.L., Li X., Zhu Y., McEachern E.J., Silverman M.A., Watson N.V., Gong C.X., Vocadlo D.J. Pharmacological inhibition of O-GlcNAcase (OGA) prevents cognitive decline and amyloid plaque formation in bigenic tau/APP mutant mice. Mol. Neurodegener. 2014;9:42. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-9-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhu Y., Shan X., Safarpour F., Erro Go N., Li N., Shan A., Huang M.C., Deen M., Holicek V., Ashmus R., Madden Z., Gorski S., Silverman M.A., Vocadlo D.J. Pharmacological inhibition of O-GlcNAcase enhances autophagy in brain through an mTOR-independent pathway. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2018;9:1366–1379. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhu Y., Shan X., Yuzwa S.A., Vocadlo D.J. The emerging link between O-GlcNAc and Alzheimer disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:34472–34481. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R114.601351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schultz J., Pils B. Prediction of structure and functional residues for O-GlcNAcase, a divergent homologue of acetyltransferases. FEBS Lett. 2002;529:179–182. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03322-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Toleman C., Paterson A.J., Whisenhunt T.R., Kudlow J.E. Characterization of the histone acetyltransferase (HAT) domain of a bifunctional protein with activable O-GlcNAcase and HAT activities. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:53665–53673. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410406200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Butkinaree C., Cheung W.D., Park S., Park K., Barber M., Hart G.W. Characterization of beta-N-acetylglucosaminidase cleavage by caspase-3 during apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:23557–23566. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804116200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rao F.V., Schuttelkopf A.W., Dorfmueller H.C., Ferenbach A.T., Navratilova I., van Aalten D.M. Structure of a bacterial putative acetyltransferase defines the fold of the human O-GlcNAcase C-terminal domain. Open Biol. 2013;3:130021. doi: 10.1098/rsob.130021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.He Y., Roth C., Turkenburg J.P., Davies G.J. Three-dimensional structure of a Streptomyces sviceus GNAT acetyltransferase with similarity to the C-terminal domain of the human GH84 O-GlcNAcase. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2014;70:186–195. doi: 10.1107/S1399004713029155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Keembiyehetty C., Love D.C., Harwood K.R., Gavrilova O., Comly M.E., Hanover J.A. Conditional knock-out reveals a requirement for O-linked N-acetylglucosaminase (O-GlcNAcase) in metabolic homeostasis. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:7097–7113. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.617779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Olivier-Van Stichelen S., Wang P., Comly M., Love D.C., Hanover J.A. Nutrient-driven O-linked N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc) cycling impacts neurodevelopmental timing and metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 2017;292:6076–6085. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.774042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schimpl M., Schuttelkopf A.W., Borodkin V.S., van Aalten D.M. Human OGA binds substrates in a conserved peptide recognition groove. Biochem. J. 2010;432:1–7. doi: 10.1042/BJ20101338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dennis R.J., Taylor E.J., Macauley M.S., Stubbs K.A., Turkenburg J.P., Hart S.J., Black G.N., Vocadlo D.J., Davies G.J. Structure and mechanism of a bacterial beta-glucosaminidase having O-GlcNAcase activity. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2006;13:365–371. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rao F.V., Dorfmueller H.C., Villa F., Allwood M., Eggleston I.M., van Aalten D.M. Structural insights into the mechanism and inhibition of eukaryotic O-GlcNAc hydrolysis. EMBO J. 2006;25:1569–1578. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li J., Wang J., Wen L., Zhu H., Li S., Huang K., Jiang K., Li X., Ma C., Qu J., Parameswaran A., Song J., Zhao W., Wang P.G. An OGA-resistant probe allows specific visualization and accurate identification of O-GlcNAc-modified proteins in cells. ACS Chem. Biol. 2016;11:3002–3006. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.6b00678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang Z., Tan E.P., VandenHull N.J., Peterson K.R., Slawson C. O-GlcNAcase expression is sensitive to changes in O-GlcNAc homeostasis. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2014;5:206. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2014.00206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fujita H., Hamazaki Y., Noda Y., Oshima M., Minato N. Claudin-4 deficiency results in urothelial hyperplasia and lethal hydronephrosis. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang H., Li Q., Liu J., Mendelsohn C., Salant D.J., Lu W. Noninvasive assessment of antenatal hydronephrosis in mice reveals a critical role for Robo2 in maintaining anti-reflux mechanism. PLoS One. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Caldwell S.A., Jackson S.R., Shahriari K.S., Lynch T.P., Sethi G., Walker S., Vosseller K., Reginato M.J. Nutrient sensor O-GlcNAc transferase regulates breast cancer tumorigenesis through targeting of the oncogenic transcription factor FoxM1. Oncogene. 2010;29:2831–2842. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shi Y., Tomic J., Wen F., Shaha S., Bahlo A., Harrison R., Dennis J.W., Williams R., Gross B.J., Walker S., Zuccolo J., Deans J.P., Hart G.W., Spaner D.E. Aberrant O-GlcNAcylation characterizes chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2010;24:1588–1598. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zachara N.E. The roles of O-linked beta-N-acetylglucosamine in cardiovascular physiology and disease. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2012;302:H1905–1918. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00445.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Peterson S.B., Hart G.W. New insights: A role for O-GlcNAcylation in diabetic complications. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2016;51:150–161. doi: 10.3109/10409238.2015.1135102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tardio L., Andres-Bergos J., Zachara N.E., Larranaga-Vera A., Rodriguez-Villar C., Herrero-Beaumont G., Largo R. O-linked N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc) protein modification is increased in the cartilage of patients with knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2014;22:259–263. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Clark R.J., McDonough P.M., Swanson E., Trost S.U., Suzuki M., Fukuda M., Dillmann W.H. Diabetes and the accompanying hyperglycemia impairs cardiomyocyte calcium cycling through increased nuclear O-GlcNAcylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:44230–44237. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303810200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ma J., Hart G.W. Protein O-GlcNAcylation in diabetes and diabetic complications. Expert Rev. Proteomics. 2013;10:365–380. doi: 10.1586/14789450.2013.820536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Walgren J.L., Vincent T.S., Schey K.L., Buse M.G. High glucose and insulin promote O-GlcNAc modification of proteins, including alpha-tubulin. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003;284:E424–E434. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00382.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Parween S., Varghese D.S., Ardah M.T., Prabakaran A.D., Mensah-Brown E., Emerald B.S., Ansari S.A. Higher O-GlcNAc levels are associated with defects in progenitor proliferation and premature neuronal differentiation during in-vitro human embryonic cortical neurogenesis. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2017;11:415. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2017.00415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schwartz R., Teramo K.A. Effects of diabetic pregnancy on the fetus and newborn. Semin. Perinatol. 2000;24:120–135. doi: 10.1053/sp.2000.6363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mills J.L. Malformations in infants of diabetic mothers. Teratology 25:385-94. 1982. Birth Defects Res. A Clin. Mol. Teratol. 2010;88:769–778. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pantaleon M., Tan H.Y., Kafer G.R., Kaye P.L. Toxic effects of hyperglycemia are mediated by the hexosamine signaling pathway and o-linked glycosylation in early mouse embryos. Biol. Reprod. 2010;82:751–758. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.109.076661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kim G., Cao L., Reece E.A., Zhao Z. Impact of protein O-GlcNAcylation on neural tube malformation in diabetic embryopathy. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:11107. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-11655-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bergmann C., Zerres K., Senderek J., Rudnik-Schoneborn S., Eggermann T., Hausler M., Mull M., Ramaekers V.T. Oligophrenin 1 (OPHN1) gene mutation causes syndromic X-linked mental retardation with epilepsy, rostral ventricular enlargement and cerebellar hypoplasia. Brain. 2003;126:1537–1544. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ishihara K., Amano K., Takaki E., Shimohata A., Sago H., Epstein C.J., Yamakawa K. Enlarged brain ventricles and impaired neurogenesis in the Ts1Cje and Ts2Cje mouse models of Down syndrome. Cereb. Cortex. 2010;20:1131–1143. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Koschutzke L., Bertram J., Hartmann B., Bartsch D., Lotze M., von Bohlen und Halbach O. SrGAP3 knockout mice display enlarged lateral ventricles and specific cilia disturbances of ependymal cells in the third ventricle. Cell Tissue Res. 2015;361:645–650. doi: 10.1007/s00441-015-2224-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Slawson C., Zachara N.E., Vosseller K., Cheung W.D., Lane M.D., Hart G.W. Perturbations in O-linked beta-N-acetylglucosamine protein modification cause severe defects in mitotic progression and cytokinesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:32944–32956. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503396200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Slawson C., Lakshmanan T., Knapp S., Hart G.W. A mitotic GlcNAcylation/phosphorylation signaling complex alters the posttranslational state of the cytoskeletal protein vimentin. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2008;19:4130–4140. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-11-1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Khidekel N., Ficarro S.B., Clark P.M., Bryan M.C., Swaney D.L., Rexach J.E., Sun Y.E., Coon J.J., Peters E.C., Hsieh-Wilson L.C. Probing the dynamics of O-GlcNAc glycosylation in the brain using quantitative proteomics. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2007;3:339–348. doi: 10.1038/nchembio881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gorelik A., Bartual S.G., Borodkin V.S., Varghese J., Ferenbach A.T., van Aalten D.M.F. Genetic recoding to dissect the roles of site-specific protein O-GlcNAcylation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2019;26:1071–1077. doi: 10.1038/s41594-019-0325-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Qian K., Wang S., Fu M., Zhou J., Singh J.P., Li M.D., Yang Y., Zhang K., Wu J., Nie Y., Ruan H.B., Yang X. Transcriptional regulation of O-GlcNAc homeostasis is disrupted in pancreatic cancer. J. Biol. Chem. 2018;293:13989–14000. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.004709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Park S.K., Zhou X., Pendleton K.E., Hunter O.V., Kohler J.J., O'Donnell K.A., Conrad N.K. A conserved splicing silencer dynamically regulates O-GlcNAc transferase intron retention and O-GlcNAc homeostasis. Cell Rep. 2017;20:1088–1099. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tan Z.W., Fei G., Paulo J.A., Bellaousov S., Martin S.E.S., Duveau D.Y., Thomas C.J., Gygi S.P., Boutz P.L., Walker S. O-GlcNAc regulates gene expression by controlling detained intron splicing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:5656–5669. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sanchez R.G., Parrish R.R., Rich M., Webb W.M., Lockhart R.M., Nakao K., Ianov L., Buckingham S.C., Broadwater D.R., Jenkins A., de Lanerolle N.C., Cunningham M., Eid T., Riley K., Lubin F.D. Human and rodent temporal lobe epilepsy is characterized by changes in O-GlcNAc homeostasis that can be reversed to dampen epileptiform activity. Neurobiol. Dis. 2019;124:531–543. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2019.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]