Abstract

Background and Aims

Understanding impacts of altered disturbance regimes on community structure and function is a key goal for community ecology. Functional traits link species composition to ecosystem functioning. Changes in the distribution of functional traits at community scales in response to disturbance can be driven not only by shifts in species composition, but also by shifts in intraspecific trait values. Understanding the relative importance of these two processes has important implications for predicting community responses to altered disturbance regimes.

Methods

We experimentally manipulated fire return intervals in replicated blocks of a fire-adapted, longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) ecosystem in North Carolina, USA and measured specific leaf area (SLA), leaf dry matter content (LDMC) and compositional responses along a lowland to upland gradient over a 4 year period. Plots were burned between zero and four times. Using a trait-based approach, we simulate hypothetical scenarios which allow species presence, abundance or trait values to vary over time and compare these with observed traits to understand the relative contributions of each of these three processes to observed trait patterns at the study site. We addressed the following questions. (1) How do changes in the fire regime affect community composition, structure and community-level trait responses? (2) Are these effects consistent across a gradient of fire intensity? (3) What are the relative contributions of species turnover, changes in abundance and changes in intraspecific trait values to observed changes in community-weighted mean (CWM) traits in response to altered fire regime?

Key Results

We found strong evidence that altered fire return interval impacted understorey plant communities. The number of fires a plot experienced significantly affected the magnitude of its compositional change and shifted the ecotone boundary separating shrub-dominated lowland areas from grass-dominated upland areas, with suppression sites (0 burns) experiencing an upland shift and annual burn sites a lowland shift. We found significant effects of burn regimes on the CWM of SLA, and that observed shifts in both SLA and LDMC were driven primarily by intraspecific changes in trait values.

Conclusions

In a fire-adapted ecosystem, increased fire frequency altered community composition and structure of the ecosystem through changes in the position of the shrub line. We also found that plant traits responded directionally to increased fire frequency, with SLA decreasing in response to fire frequency across the environmental gradient. For both SLA and LDMC, nearly all of the observed changes in CWM traits were driven by intraspecific variation.

Keywords: Pinus palustris, Aristida stricta, specific leaf area, intraspecific variation, ecotone, fire, community-weighted means, longleaf pine, disturbance

INTRODUCTION

Abiotic disturbances are one of the key factors that affect how ecological communities assemble and persist. However, the location, frequency and intensity of disturbance are changing in response to anthropogenic activity, and wildfires in particular have increased in both frequency and intensity globally (Pechony and Shindell, 2010; Balch et al., 2017). Fire-adapted plant communities are expected to be resilient in the face of wildfire but alterations to fire regimes may drive changes in community structure (e.g. the presence or absence of woody species or grasses), composition and biodiversity. These changes can have cascading impacts on ecosystem function through changes in the distribution of plant functional traits within the community [e.g. alterations to specific leaf area (SLA) can directly impact decomposition rates within ecosystems; Cornwell et al., 2008]. These changes in trait expression are typically quantified using community-weighted means (CWMs) which sum the contribution of each species’ trait value weighted by its relative abundance in the community. Temporal shifts in CWMs can be driven by interspecific trait variation that results from changes in community composition (including both species turnover and change in species abundance), and by changes in trait values within species [i.e. intraspecific trait variation (ITV); Fig. 1]. Unlike changes in community composition (i.e. species presence and abundance) which can result in changes to metrics of species diversity and richness or lead to ecosystem state changes, ITV may buffer the species diversity of communities in the face of altered disturbance regimes. For example, fire-adapted species may shift trait expression rather than presence or abundance in response to changes in disturbance. At present, it is unclear which process is likely to more strongly shape trait expression in fire-adapted ecosystems under altered fire regimes.

Fig. 1.

Community weighted means (CWMs) can be calculated for a given trait using the presence and abundance of species on a plot. Here, hypothetical species in 2011 are denoted by shape, and trait values by the size of the shape. The CWM on a given plot can change over time, and in response to disturbance in one of three ways. In scenario A, the blue circles and orange squares have been extirpated, and black crosses and green triangles have immigrated, leading to species turnover and changes in CWMs. In scenario B, species abundance but not identity are altered, leading to changes in the CWM. Finally, in scenario C, the values of traits but not species identity change, driving changes in CWMs.

There is an abundance of research demonstrating that plant functional traits, quantified using CWMs, respond in predictable ways to changes in environmental conditions on continental scales (Swenson and Weiser, 2010) and from ecosystems as disparate as chaparral (Cornwell and Ackerly, 2009) and arctic tundra (Venn et al., 2011). Until recently, changes in trait expression within systems were expected to be driven primarily by species turnover in response to abiotic filtering (Violle et al., 2012; Albert, 2015). Differences in traits between species were expected to be much higher than differences within species (McGill et al., 2006), and thus changes in trait values within communities were believed to be primarily driven by the loss or addition of species, or through changes in species abundance (Pescador et al., 2015), and the role of ITV could be safely ignored (McGill et al., 2006). However, ITV has been shown both to be substantial (Albert et al., 2010) and to play a critical role in assembly processes within ecosystems (Jung et al., 2010; Violle et al., 2012). Recent research at global scales has indicated that ITV is important in shaping community assembly processes (Siefert et al., 2015) and must be considered when attempting to understand community patterns (Albert et al., 2011; Albert, 2015). Changes in trait values within communities driven by ITV have been demonstrated in response to alterations in fertilization (Siefert and Ritchie, 2016), grazing (Niu et al., 2016) and in epiphytic species in response to reductions in fertility (Asplund and Wardle, 2014). However, the extent of change in CWM trait values in response to disturbance that can be attributed to changes in ITV, rather than changes in species presence or abundance, is unknown.

Strong filters such as intense grazing, reduced precipitation and frequent fire are expected to reduce variation in functional traits both within and across species, and select for trait ‘syndromes’ that promote survival (Díaz and Cabido, 1997; Reich et al., 2003; Diaz et al., 2007; Brussel et al., 2018). However, global change and anthropogenic activities are altering fire return intervals in forest ecosystems, which have been demonstrated to have measurable consequences for species diversity (Bowman et al., 2014; Fairman et al., 2017) primarily due to species loss and turnover. In several fire-adapted systems, these changes have been tied directly to plant functional traits, particularly resprouting ability (Enright et al., 2014; Fairman et al., 2019). The importance of functional traits for predicting both the response of, and effect on, ecosystems to altered disturbance regimes is widely recognized, but the role of ITV in systems experiencing altered disturbance regimes is still poorly understood.

Longleaf pine (Pinus palustris)–wiregrass (Aristida stricta) forests in the Southeastern USA are widely recognized to be fire-adapted systems (Noss, 1989; Peet and Allard, 1993). The structure of the forest understorey, driven by dominance of either grasses or shrubs, is primarily shaped by fire frequency (Hodgkins, 1958; Glitzenstein et al., 2003; Outcalt and Brockway, 2010) and, historically, frequent fire return intervals (1–8 years) maintained grass dominance in longleaf pine forest understoreys (Clewell, 1989). Changes in fire frequency and intensity in these systems have been shown to affect the diversity and composition of species in the understorey, with reduced fire frequency favouring dominance and regeneration of shrubs (Brockway and Lewis, 1997; Thaxton and Platt, 2006). In addition to shaping composition and structure, Ames et al. (2016) showed that trait expression, and CWMs of SLA and LDMC were controlled in part by the time since the previous fire in plots experiencing a long-term 3 year burn rotation. Intriguingly, they found that detecting fire effects on CWMs of SLA and LDMC required using plot-level trait data rather than landscape-level species means, highlighting the potential importance of ITV in mediating community-level responses to fire. Specific leaf area and LDMC are commonly measured functional traits that represent fundamental trade-offs between photosynthesis and construction of structural tissues (Shipley et al., 2006). Leaf dry matter content has been shown to contribute to flammability (Cornelissen et al., 2003; Pérez-Harguindeguy et al., 2013) and is a key predictor of post-fire recovery (Saura-Mas et al., 2009). Specific leaf area, highly variable (Bloomfield et al., 2018) and strongly tied to leaf life span and plant relative growth rate (Reich et al., 2003; Wright et al., 2004), is expected to respond to fire if plants alter growth strategies in response to fire frequency.

Using a trait-based approach, we simulate hypothetical scenarios which allow species presence, abundance or trait values to vary over time and compare these with observed traits to understand the relative contributions of each of these three processes to observed trait patterns at the study site. While these factors are unlikely to vary completely independently from one another in natural systems, a sensitivity analysis approach allows us to examine each driver independently. With these data and these simulations, we examine the responses of the vegetation community to experimentally altered fire regimes. We ask the following three questions. (1) How do changes in the fire regime affect community composition, structure and community-level trait responses? (2) Are these effects consistent across a gradient of soil moisture and fire intensity? (3) What are the relative contributions of species turnover, changes in abundance and changes in intraspecific trait values to observed changes in CWM traits in response to altered fire regime?

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study site

This study was conducted on the eastern seaboard of the USA, in the state of North Carolina, between the summer of 2011 and 2014 on Fort Bragg (35°8'21''N, 78°59'57''W). This site is located in the North Carolina Sandhills and is characterized by its rolling topography and longleaf pine (Pinus palustris)/wiregrass (Aristida stricta) ecosystem (Sorrie et al., 2006). The upper reaches of the many drainages formed by the rolling topography typically support two fire disturbance-dependent communities; ericaceous shrub-dominated stream head pocosins and cane-dominated (Arundinaria spp.) stream head canebrakes (see Gray et al., 2016 for a detailed discription of the vegetation of these communities, and Supplementary data Table S1 for a list of species at the site). The former is dominated by an understorey of ericaceous shrubs and develops under relatively lower fire frequency than that within switch cane- (Arundinaria tecta) dominated stream head canebrakes. These two very different communities can displace each other within a decade depending on the fire frequency (Gray et al., 2016).

The study area has been divided into burn units (mean = 45 ha), which have been burned on average every 3 years since 1991, typically during the vegetation dormant season, mimicking historic fire return intervals (Frost, 1998; Stambaugh et al., 2011). This historic burn regime has been shown to maximize understorey biodiversity in longleaf systems (Glitzenstein et al., 2003). Prescribed burning at this site is done using low-intensity backing fires to maximize control of the fires and prevent them from escaping into the tree crowns. As a result, low-lying wet areas burn infrequently despite prescribed burning (Weakley and Schafale, 1991; Just et al., 2016).

At the beginning of the 2011 growing season, we established 30 research sites located within a 16 km diameter area within Fort Bragg, each spanning the dry, grass-dominated to moist, shrub-dominated ecotone located within the study site (Supplementary data Fig. S1). Site locations were distributed across burn units in order to span the entire available burn gradient (0–4 years). To capture the full range of understorey community variation at each site, we situated a 3 × 5 m monitoring plot at the ecotone where the plant community transitioned from grass dominated to shrub dominated (hereafter called ‘ecotone’ plots), then placed one plot 10 m directly upslope from the ecotone plot (hereafter called ‘upland’ plots), and additional plots every 10 m downslope until reaching the wet, lowland areas (hereafter called lowland plots), resulting in a variable number (3–7) of monitoring plots at each site spanning a distance of 30–80 m (Supplementary data Fig. S2). This yielded a total of 30 upland plots, 30 ecotone plots and 45 lowland plots. Available burn records only specify the quantity of acreage burned in each burn block (i.e. site) but do not provide detailed burn maps. Because of this, and the fact that areas deep in lowland areas burn infrequently (Weakley and Schafale, 1991; Just et al., 2016), we restricted our analyses to open-canopy plots located where understorey burning is generally complete, for a total of 88 plots. For each monitoring plot, we quantified its elevation above the stream head in centimetres as described in Ames et al. (2016). We also measured soil moisture repeatedly (an average of 16 samples per plot) in the top 15 cm of soil using a reflectometry probe in each plot; plot soil moisture ranged from 2 to 80 %.

Experimental fire regime manipulation

Starting in 2011, research plots were assigned to one of three burn treatments: annual burn, control (i.e. continuing on the historically applied 3 year burn rotation) and suppression. We assessed each plot for whether or not it burned annually, as fire treatments were applied at the site level, but fires did not always completely burn all plots located within a site. Additionally, assigned burn treatments were not followed at all sites due to the occurrence of a wildfire at a suppression site and cases where sites did not burn when assigned due to logistical constraints. Furthermore, sites in the control treatment varied in the number of fires they experienced during the study period depending on where they were in the burn cycle when the study began. As a result, rather than treating burn treatment as a categorical variable applied at the site level, we opted to quantify the number of fires experienced by a plot during the experimental period as our metric of burn regime. The number of fires experienced for a given plot was highly correlated with the number of days since burned.

Vegetation measurements

Within each monitoring plot, four 1 m2 sub-plots were installed and aerial cover was visually estimated for all plant species between 1 and 17 June 2011 and between 28 July and 21 August 2014. For the analyses, cover data for each species were aggregated across the sub-plots and divided by total plot cover to obtain relative cover estimates for each plot. To quantify whether burn frequency affected the position of the ecotone, during the 2014 surveys, we measured the distance from the upslope plot to the position of the shrub line (initially 10 m along the slope when the plots were set up in 2011).

Trait measurement

We focus on SLA and LDMC, which are known to reflect fundamental trade-offs in resource use strategies (Shipley et al., 2006), to respond to alterations in fire regimes (Saura-Mas et al., 2009; Anacker et al., 2011; Laughlin et al., 2011; Ames et al., 2016), and to directly drive ecosystem processes such as flammability and decomposition (Grootemaat et al., 2015). Within each plot, we ranked all species by relative abundance and sampled as many of the most abundant species as required to account for at least 75 % of the total cover in each plot. For each species in each monitoring plot, we randomly selected five mature, healthy leaves from different individuals in the plot whenever possible following standard protocols (Garnier et al., 2001; Cornelissen et al., 2003). In cases where fewer than five individuals were present, we collected multiple leaves from individual plants located within the plot. Leaf samples for each species were sealed in plastic bags, placed on ice and returned immediately to the lab, where they were weighed and digitally imaged within 1 h of collection. Image processing was conducted using WinFolia Software (Régent Instruments, Quebec, Canada). Leaf samples were dried at 40 °C for a minimum of 1 week and reweighed. Leaf dry matter content was calculated as leaf dry mass (g) divided by leaf fresh mass (g), and SLA was calculated as leaf area per unit of dry mass (cm2 g–1). Extreme outliers, defined as those values more than three interquartile ranges below the first or above the third quartile for each species (Tukey, 1977), were removed prior to analysis. Community-weighted mean trait values for each plot (CWM) were calculated as the mean trait value of each species in the plot (calculated using only data from the plot in question) weighted by its relative abundance in the plot.

Statistical analyses

Magnitude of compositional change and trait shifts.

To assess the effect of the number of burns during the experimental period on community composition, we first calculated the Bray–Curtis distance (McCune and Grace, 2002) between 2011 and 2014 for each plot. These data were then log transformed to correct for heteroskedasticity. We used R (v. 4.0.2) and lme4 (Bates et al., 2012) to characterize the impact of fire on the magnitude of compositional change; we constructed mixed-effects models using elevation, number of burns and elevation × number of burns as fixed effects, and site as a random effect. We then used Akaike’s information criterion (AIC) and backward elimination to identify the most parsimonious model. We used an identical approach to model the effects of fire on the CWM of SLA and LDMC (Supplementary data Table S2). To test for the significance of the interaction between fire and elevation and the main effects of fire, we obtained P-values using likelihood ratio tests of the full model with the effect in question against the model without the effect in question. Marginal R2 values for models were calculated using the MuMIn function in R (Barton, 2016).

Ecotone movement.

To assess the impact of number of burns on the location of the ecotone (which can only be assessed at the site level), we used a generalized linear model with the ecotone elevation (m) as a dependent variable, and number of burns as the predictor variable.

Drivers of trait response.

The CWM is calculated using the equation:

| (1) |

where the CWM of a given trait (X) on a given plot (i) is equal to the product of the trait value (X) and relative abundance (P) summed over all species (S) present on the plot. To assess the relative importance of species turnover, changes in abundance and ITV for trait expression, we first calculated the observed difference in CWM for each trait between 2011 and 2014 using the species and trait values observed in each plot. We then calculated CWMs under a sequence of hypothetical scenarios to generate CWM trait values that we would expect to be driven by three ecological processes: changes in species presence within the community (CWMTURNOVER), changes in species abundance within the community (CWMABUNDANCE) and changes in trait values without changes in presence or abundance (CWMITV; Table 1; Fig. 1). Community-weighted means generated from these hypothetical scenarios were then subtracted from CWM2014 to quantify the proportion of change in calculated CWM between 2011 and 2014 that was explained by each ecological process.

Table 1.

Variables and data used to calculate community-weighted means for observed and alternative trait models

| Community-weighted mean | Species set | Abundance values | Trait values |

|---|---|---|---|

| CWM2014 | All | Final | Final |

| CWM2011 | All | Initial | Initial |

| CWMTURNOVER | Constant | Final | Final |

| CWMABUNDANCE | Constant | Initial | Final |

| CWMITV | Constant | Final | Initial |

‘All’ refers to all species that occurred on the plot. ‘Constant’ refers only to those species which were present in both 2011 and 2014. ‘Final’ refers to abundance or trait values measured in 2014, while ‘Initial’ is abundance or trait values measured in 2011.

Specifically, to assess the effect of species turnover on observed CWMs [a change only in the S term of eqn (1), Fig. 1A], we used only species present in both time points (i.e. in both 2011 and 2014) to calculate CWMs for each plot using trait values measured in 2014. This generates an estimate of the CWM of the trait we would observe if there was no species turnover. Thus, the difference between CWM2014 and the CWMTURNOVER (CWM2014 – CWMTURNOVER) represents the magnitude of the effect of species turnover on CWM values.

To assess the effect of changes in relative abundance on observed trait values [a change only in the P term of eqn(1), Fig. 1B], we again calculated CWMs using only the species present in plots in both 2011 and 2014 (to avoid accounting for turnover twice). We then calculated the difference between the CWMs calculated using the abundance of species and trait values in the final time point and the CWMs calculated using the abundance of species in the initial time point but trait values from the final time point. This assumes that there are no changes in trait values between 2011 and 2014, and no addition or loss of species to the community. The change in the value of the calculated CWM would be due only to changes in abundance of species present in 2011 and 2014.

To assess the effects of ITV on observed trait values [a change only in the X value of eqn (1), Fig. 1C], we again used only the set of species present at both time points, and abundances measured in 2014. This assumes that there is no change in species presence or abundance over time. We then calculated the difference between the CWMs using the trait values of species at the final time point and the CWMs using the trait values at the initial time point to estimate the magnitude of the effect of changes on CWM values.

RESULTS

Community-level responses to fire

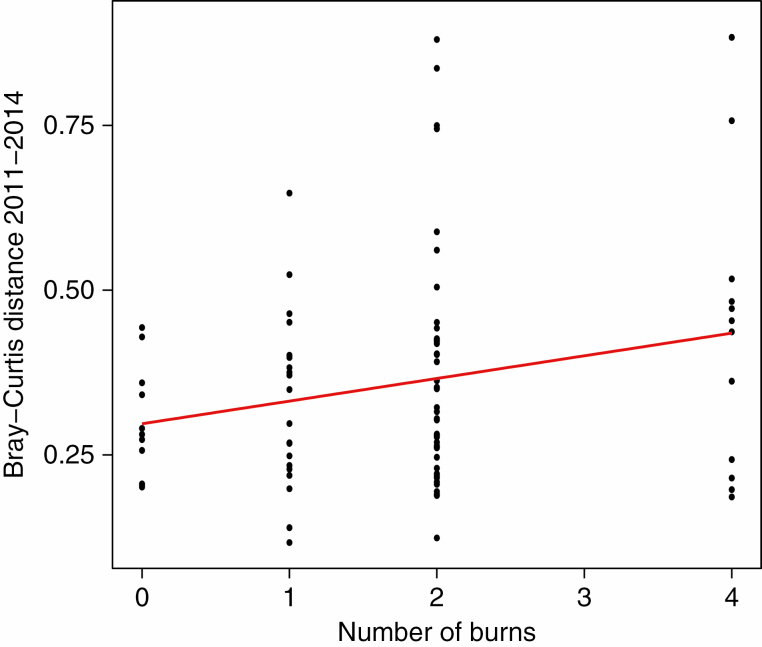

We observed a marginally significant effect of the number of burns on the distance that plots moved in community space over the course of the experiment [χ 2(1), P = 0.06, Table 2]. There was no indication of an interaction with elevation. Both the mean distance and the variance in distance moved increased as the number of burns experienced increased (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Full model set comparisons for the effects of elevation and number of times burned on compositional shift, CWM of SLA and shifts in CWM of SLA due to changes in traits

| Model | Elevation | No. of burns | Elevation × no. of burns | Marginal R2 | AIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community shift | |||||

| Full model | 0.0001 | 0.14 | –0.0002 | 0.05 | 105.5 |

| No interaction | –0.0003 | 0.08 | * | 0.05 | 104.1 |

| No elevation | * | 0.08 | * | 0.04 | 103.0 |

| No. of burns | –0.0003 | * | * | 0.01 | 105.8 |

| Site only | * | * | * | * | 104.5 |

| CWM of SLA | |||||

| Full model | –0.06 | –39.1 | 0.08 | 0.13 | 943.5 |

| No interaction | 0.05 | –19.2 | * | 0.10 | 944.4 |

| No elevation | * | –19.32 | * | 0.10 | 943.5 |

| No. of burns | 0.06 | * | * | 0.01 | 946.9 |

| Site only | * | * | * | * | 946.2 |

| Trait shift driver of CWM of SLA | |||||

| Full model | –0.04 | –33.3 | 0.04 | 0.17 | 900.3 |

| No interaction | 0.02 | –22.4 | * | 0.17 | 899.7 |

| No elevation | * | –22.1 | * | 0.16 | 898.1 |

| No. of burns | 0.02 | * | * | 0.002 | 905.9 |

| Site only | * | * | * | * | 904.2 |

| CWM of LDMC | |||||

| Full model | –7.1e-06 | –0.003 | 1.9e-05 | 0.05 | –173.2 |

| No interaction | 2.1e-5 | 0.024 | * | 0.05 | –175.1 |

| No elevation | * | 0.025 | * | 0.05 | –177.1 |

| No. of burns | 2.8e-05 | * | * | 0.001 | –174.8 |

| Site only | * | * | * | * | 946.2 |

| Trait shift driver of CWM of LDMC | |||||

| Full model | –7.5 e-5 | 0.03 | 1.7 e-6 | 0.15 | –244.6 |

| No interaction | –7.3 e-5 | 0.03 | * | 0.15 | –246.6 |

| No elevation | * | -0.03 | * | 0.12 | –408.9 |

| No. of burns | –6.8 e-5 | * | * | 0.01 | –235.7 |

| Site only | * | * | * | * | –395.5 |

The baseline model included only a random effect of site, while the full model included fixed terms for number of burns, elevation and the interaction between number of burns and elevation, as well as a random effect of site.

The table lists the coefficients for terms included in each model, marginal R2 and the AIC for each individual model. Model(s) with the lowest AIC in each model set are in bold

Fig. 2.

Change in community composition from 2011 to 2014 in response to the number of fires in a plot as quantified by the Bray–Curtis dissimilarity.

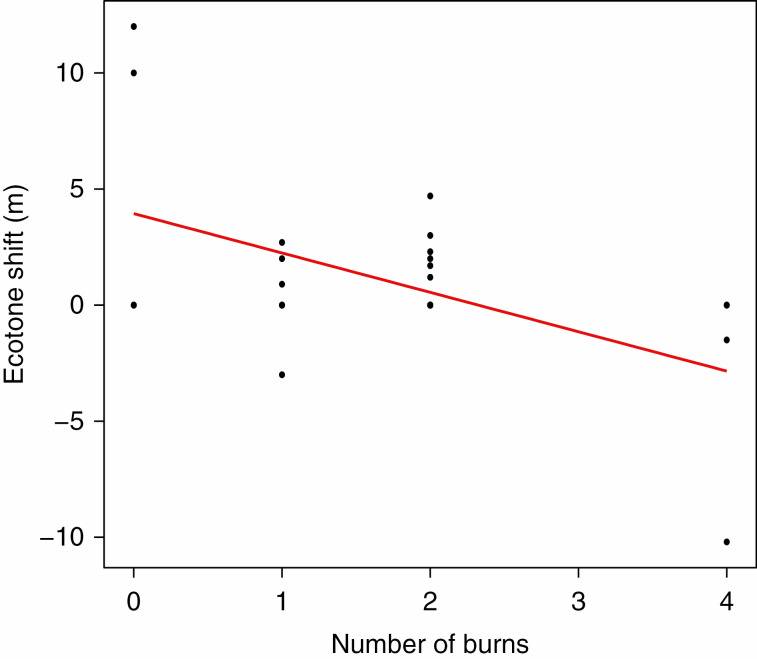

Ecotone movement

The elevation of the shrub line showed strong and significant responses to changes in prescribed burn frequency (P = 0.003, Fig. 3; Supplementary data Table S3). Fire suppression caused the position of the shrub line to move on average almost 5 m towards the uplands, while at the sites experiencing the most frequent burns the shrub line moved downslope toward the lowlands over 2.5 m on average.

Fig. 3.

Change in the position of the ecotone (shrub line) along the elevational gradient in response to the number of fires experienced between 2011 and 2014.

Effects on community-weighted mean of leaf traits

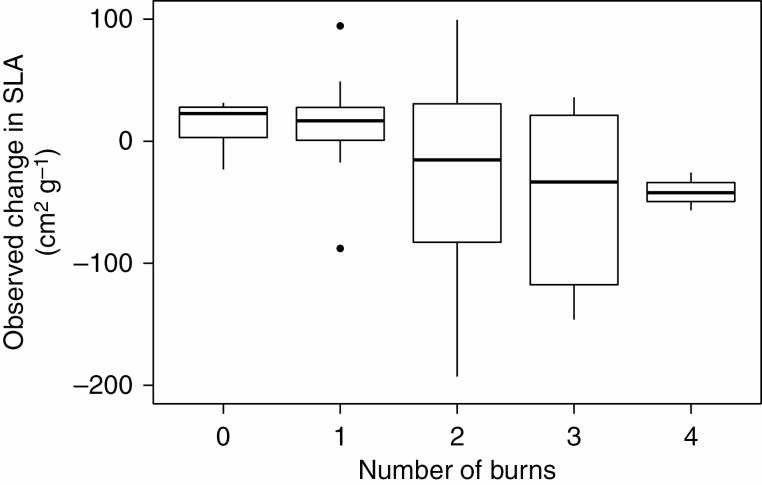

First, we saw a significant effect of number of times burned on the change in CWM of SLA independent of elevation of the plot [χ 2(1), P = 0.03, Table 2]. Plots that had experienced no burns tended to increase in SLA, with an average increase of 14.7 ± 5.3 cm2 g–1 (mean ± s.e.), while plots that had experienced four burns decreased in CWM of SLA by about 41.4 ± 9.0 cm2 g–1 (Fig. 4). Plots that had experienced no burns showed no change in LDMC (0.04 ± 0.02 %) while plots that experienced four burns increased in LDMC by 0.15 ± 0.06% (Supplementary data Fig. S3). However, there was no overall significant effect of number of burns on the CWM of LDMC [χ 2(1), P = 0.12, Table 2].

Fig. 4.

Change in CWMSLA in response to the number of fires between 2011 and 2014.

Differences between CWM2014 and CWMTURNOVER showed a much smaller range of variability than the observed changes in CWM of SLA, and showed no differences across burn frequencies, suggesting that the proportion of change in CWM of SLA caused by changes in species composition is minimal (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, across all plots, the observed shifts in CWM of SLA were not predicted by the amount of shift due to compositional turnover (Fig. 5B). Likewise, differences between CWMTURNOVER and CWMABUNDANCE showed a narrower range of variability than observed changes in CWM of SLA and no differences across burn frequencies, and again there was no relationship between observed shifts and the shifts predicted due to changes in relative abundance (Fig. 5C, D). Together these results suggest that the proportion of observed change in CWM of SLA driven by changes in relative abundance is also minimal. However, differences between CWMTURNOVER and CWMITV shows a similar range of variability as in the observed data. Furthermore, these differences are significantly affected by burn frequency [χ 2(1), P = 0.005, Table 2] and show the same pattern as the observed data (Fig. 5E). The relationship between observed changes and the predicted changes due to shifts in intraspecific trait values at the plot level is significant and positive (slope = 0.84, R2 = 0.90, P < 0.001, Fig. 5F). The same patterns were observed for the relative importance of the different mechanisms to explain changes in CWM of LDMC (Supplementary data Fig. S4). Differences in LDMC CWMTURNOVER are significantly affected by burn frequency [χ 2(1), P < 0.001, Table 2] and show the same pattern as the observed data.

Fig. 5.

The amount of change in CWMSLA ascribed to changes in species abundance (A and B), species turnover (C and D) and trait values (E and F).

DISCUSSION

In light of the extent and importance of ITV, there has been a recent push to disentangle the drivers shaping trait expression across environmental gradients and in response to environmental change. Species can respond to environmental change in one of three ways: phenotypic plasticity; evolution in place via selection on traits; or dispersal. The recent focus on ITV typically captures the first two processes simultaneously, as ITV can be generated by phenotypic plasticity responses to environmental change or selection for genotypes pre-adapted to new conditions (Grime et al., 2008; Poorter et al., 2009; Violle et al., 2012; Wright et al., 2016; Funk et al., 2017). Our results, taken together, demonstrate that in this fire-adapted system, ITV is the primary way that species’ leaf traits respond to alterations in disturbance regimes, at least over the near term. While there was some evidence of structural (shrub vs. grass dominance) shifts in the plant community (i.e. the elevation of the ecotone shifted significantly in response to the number of fires; Fig. 3), we also found that the magnitude of change in community composition in response to number of fires (quantified using the Bray–Curtis distance; Fig. 2) was only marginally significant. The CWM of SLA, on the other hand, showed significant responses to the number of fires experienced, with significantly lower CWM SLA values in plots that had experienced more burns and higher SLA values in less frequently burned sites, indicating a shift away from rapid growth and toward conservative growth as the number of fires increased (Fig. 4). When we decomposed the potential drivers of this trait shift using sensitivity analysis, our results indicated that ITV, rather than changes in abundance or species turnover, was the primary driver of changes in trait values at the community level (Fig. 5). While LDMC did not show a statistically significant response to number of fires experienced, we did find that, like SLA, the majority of measured change in CWMs of LDMC were due to ITV, rather than changes in species presence or abundance (Supplementary data Fig. S4).

We also found that, as the number of fires experienced in a plot increased, the magnitude of compositional change also increased (i.e. composition differed more in plots that had burned four time vs. once). These results largely agree with findings stemming from other systems, both fire prone and fire sensitive. Increased fire is expected to select for families and species best adapted to coping with fire (Bond and Keeley, 2005; Cavender-Bares and Reich, 2012), and altered fire regimes are expected to impact woody species most severely (Enright et al., 2015). For example, in fire-sensitive sagebrush steppe, repeated fires led to dramatic shifts in the composition and structure of vegetation, with loss of woody reseeding species and increased cover of resprouting shrubs and invasive grass species in repeatedly burned areas (Davies et al., 2012). In boreal black spruce- (Picea mariana) dominated ecosystems, repeated, short-interval fires significantly reduced recruitment of seedlings compared with infrequent fire (Brown and Johnstone, 2012). In fire-prone ecosystems, such as California chaparral and longleaf pine forests, frequent fire has reduced the cover of dominant shrub species and altered composition, and in the former increased the presence of invasive species in the system (Thaxton and Platt, 2006; Keeley and Brennan, 2012). Even in fire-dependent serotinous systems, an increased number of fires has been shown to negatively impact the structure and composition of the ecosystem (Buma et al., 2013). In our study, movement of the ecotone, as quantified by changes in the shrub line, mirror these findings. As fire number increased in our system, the shrub line moved down the elevation and soil moisture gradient, toward wetter sites, indicating reduced recovery of upland woody species in response to repeated fire.

Previous work in this system has demonstrated that fire can have profound impacts on functional trait expression (Ames et al., 2016), and we found that as the number of fires in a plot increased, CWM of SLA values decreased (i.e. higher leaf mass per unit area) while the CWM of LDMC responded in the opposite direction, though this shift was not statistically significant. Previous research in fire-adapted systems has found mixed responses of SLA to fire. For example, in California chaparral, SLA was higher on recently burned sites (Anacker et al., 2011), while Australian mesic savannah plants showed reduced SLA in response to repeated wildfire (de Souza et al., 2016). High values of SLA are generally linked to rapid growth in resource-rich sites, while lower values are linked to slower growth and a resource-conserving strategy (Wright et al., 2004). Frequent, repeated fire may reduce soil nutrient profiles, pushing surviving species toward slower growth and reduced SLA. Furthermore, frequent fire has been demonstrated to favour resprouting species over reseeding species (Midgley, 1996; Bell, 2001; Ojeda et al., 2005; Clarke et al., 2015; Hammill et al., 2016), and reduced CWM SLA in our fire-adapted, perennial-dominated system may reflect depletion of root resources after repeated resprouting efforts.

Several mechanisms have been identified as drivers of shifts in CWM trait values, with the majority of previous research focused on changes in trait values due to changes in species abundance or turnover (e.g. Cornwell and Ackerly, 2009; Kraft and Ackerly, 2010; Messier et al., 2010). Our results, comparing observed results with three simulated scenarios using sensitivity analysis, indicate that these processes are likely to play a smaller role in shaping trait expression in this plant community over short temporal scales than previously expected (Fig. 5). The majority of the observed changes in SLA and LDMC were explained by changes in trait values due to ITV (Fig. 5E, F; Supplementary data Fig. S4), while only a small amount of variation could be ascribed to either changes in abundance or turnover (Fig. 5A–D; Supplementary data Fig. S4). Previous research has demonstrated that there is substantial variation in SLA and LDMC for species in this system, and this variability may be leveraged to better cope with prevailing environmental conditions (Mitchell et al., 2017). While similar patterns have been documented in response to fertilization (Siefert and Ritchie, 2016), drought (Jung et al., 2014) and grazing (Niu et al., 2016), nearly all of these studies have taken place in grassland communities, and none in response to fire. Our results demonstrate that, in this perennial-dominated, fire-adapted system, the primary response to altered disturbance regimes is through intraspecific trait variability.

There are several potential explanations for why ITV may be the primary mechanism for these species in response to increased fire frequencies. This ecosystem is fire adapted and had been exposed to a relatively short fire return interval (3 years) prior to the start of this experiment. This management practice may have already extirpated species that were not adapted to this fire regime from the community and fundamentally altered the structure of the system (Bond et al., 2005; Bond and Keeley, 2005; Cavender-Bares and Reich, 2012; Keeley, 2016). Thus, species which would have quickly been lost from the system or dramatically reduced in abundance in response to experimentally altered fire frequency may have already been absent. Previous research in longleaf pine savannas has demonstrated that shrubs in the understorey are very resilient to repeated fire, resprouting from rootstock at similar or increased densities after fire (Olson and Platt, 1995; Drewa et al., 2002). This resilience may preclude dramatic changes in community composition or abundance in response to fire regime change imposed over relatively short periods, leaving species to cope with increased fire return intervals via altered physiological function and captured as change in trait values at the species level.

Future work in this system should focus on the processes governing ITV in these species. At present, it is unknown whether observed ITV is driven primarily by genotypic diversity or phenotypic plasticity, as both processes can drive the patterns observed in this study (Wright et al., 2016). In addition, while we controlled for elevation, a proxy for soil texture and soil moisture in this study, additional factors should be investigated that may covary or act synergistically with fire to alter community assembly processes in this system. For example, the effects of canopy openness were not quantified in this study. Specific leaf area has been demonstrated to respond strongly to light availability (Westoby, 1998; Reich et al., 2003; Poorter et al., 2009; Mason et al., 2011; Mitchell and Bakker, 2014) and thus light availability may interact with fire frequency to shape assembly processes. However, given that the fires in this system are primarily ground level, we do not expect that the changes in fire frequency induced in this study were likely to induce systematic changes in canopy cover. Finally, the role of climate, and specifically interactions between climate and fire intensity, should be examined as species traits may respond differently to higher and lower intensity fires.

Conclusions

Our results demonstrate that, in a fire-adapted ecosystem, increased fire frequency altered plant community composition and the structure of the ecosystem through changes in the position of the shrub line, which retreated toward higher soil moisture in response to increased fire frequency. We also found that plant traits responded directionally to increased fire frequency, with SLA decreasing in response to fire across the environmental gradient. Importantly, using a sensitivity analysis, we revealed that changes in observed trait values driven by ITV was the primary mechanism by which traits responded to changes in the fire regime. While the mechanisms underlying ITV are not yet clear in this system, these results argue that maintaining high levels of ITV might be an important management goal to allow communities to respond to future shifts in fire regimes.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available online at https://academic.oup.com/aob and consist of the following. Figure S1: map of burn units and research sites located at Fort Bragg, NC, USA. Figure S2: experimental design and location of monitoring plots along the ecotone. Figure S3: CWMLDMC in response to the number of burns. Figure S4: amount of change in CWMLDMC ascribed to changes in species abundance, species turnover and ITV. Table S1: species list for the study area. Table S2: full model set comparisons for the effects of elevation and number of times burned on species richness, composition shift and shift in CWM of SLA. Table S3: model results for analysis of the effects of number of fires on distance of ecotone shift.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the U.S. Army Engineer Research Development Center, Construction Engineering Research Laboratory (ERDC-CERL) for funding for this project; Janet Gray from the Fort Bragg Endangered Species Branch for logistical support; and John Ward for administering the experimental burns. S. Anderson and E. Unberg provided invaluable field assistance. Matthew Hohmann and Wade Wall provided helpful input on this manuscript.

FUNDING

Construction Engineering Research Laboratory (ERDC-CERL): cooperative agreement W9132T-11-2-0008.

LITERATURE CITED

- Albert CH. 2015. Intraspecific trait variability matters. Journal of Vegetation Science 26: 7–8. [Google Scholar]

- Albert CH, Thuiller W, Yoccoz NG, Douzet R, Aubert S, Lavorel S. 2010. A multi-trait approach reveals the structure and the relative importance of intra- vs. interspecific variability in plant traits. Functional Ecology 24: 1192–1201. [Google Scholar]

- Albert CH, Grassein F, Schurr FM, Vieilledent G, Violle C. 2011. When and how should intraspecific variability be considered in trait-based plant ecology? Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics 13: 217–225. [Google Scholar]

- Ames GM, Anderson SM, Wright JP. 2016. Multiple environmental drivers structure plant traits at the community level in a pyrogenic ecosystem. Functional Ecology 30: 789–798. [Google Scholar]

- Anacker B, Rajakaruna N, Ackerly D, Harrison S, Keeley J, Vasey M. 2011. Ecological strategies in California chaparral: interacting effects of soils, climate, and fire on specific leaf area. Plant Ecology and Diversity 4: 179–188. [Google Scholar]

- Asplund J, Wardle DA. 2014. Within-species variability is the main driver of community-level responses of traits of epiphytes across a long-term chronosequence. Functional Ecology 28: 1513–1522. [Google Scholar]

- Balch JK, Bradley BA, Abatzoglou JT, Nagy RC, Fusco EJ, Mahood AL. 2017. Human-started wildfires expand the fire niche across the United States. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 114: 2946–2951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates D, Mäachler M, Bolker B. 2011. lme4: linear mixed-effects models using s4 classes. http://cran.R-project.org/package=lme4. R package version 0.999375-42.

- Barton K. 2016. MuMIn: Multi-Model Inference.http://R-Forge.R-project.org/projects/mu?min/.

- Bell DT. 2001. Ecological response syndromes in the flora of southwestern Western Australia: fire resprouters versus reseeders. Botanical Review 67: 417–440. [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield KJ, Cernusak LA, Eamus D, et al. 2018. A continental-scale assessment of variability in leaf traits: within species, across sites and between seasons. Functional Ecology 32: 1492–1506. [Google Scholar]

- Bond WJ, Keeley JE. 2005. Fire as a global ‘herbivore’: the ecology and evolution of flammable ecosystems. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 20: 387–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond WJ, Woodward FI, Midgley GF. 2005. The global distribution of ecosystems in a world without fire. New Phytologist 165: 525–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman DM, Murphy BP, Neyland DL, Williamson GJ, Prior LD. 2014. Abrupt fire regime change may cause landscape-wide loss of mature obligate seeder forests. Global Change Biology 20: 1008–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockway DG, Lewis CE. 1997. Long-term effects of variable frequency fire on plant community diversity, structure and productivity in a longleaf pine wiregrass flatwoods ecosystem. Forest Ecology and Management 96: 167–183. [Google Scholar]

- Brown CD, Johnstone JF. 2012. Once burned, twice shy: repeat fires reduce seed availability and alter substrate constraints on Picea mariana regeneration. Forest Ecology and Management 266: 34–41. [Google Scholar]

- Brussel T, Minckley TA, Brewer SC, Long CJ. 2018. Community-level functional interactions with fire track long-term structural development and fire adaptation. Journal of Vegetation Science 29: 450–458. [Google Scholar]

- Buma B, Brown C, Donato D, Fontaine J, JohnStone J. 2013. The impacts of changing disturbance regimes on serotinous plant populations and communities. BioScience 63: 866–876. [Google Scholar]

- Cavender-Bares J, Reich PB. 2012. Shocks to the system: community assembly of the oak savanna in a 40-year fire frequency experiment. Ecology 93: S52–S69. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke PJ, Lawes MJ, Murphy BP, et al. 2015. A synthesis of postfire recovery traits of woody plants in Australian ecosystems. The Science of the Total Environment 534: 31–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clewell AF. 1989. Natural history of wiregrass (Aristida stricta Michx. Gramineae). Natural Areas Journal 9: 223–233. [Google Scholar]

- Cornelissen JHC, Lavorel S, Garnier E, et al. 2003. A handbook of protocols for standardised and easy measurement of plant functional traits worldwide. Australian Journal of Botany 51: 335. [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell WK, Ackerly DD. 2009. Community assembly and shifts in plant trait distributions across an environmental gradient in coastal California. Ecological Monographs 79: 109–126. [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell WK, Cornelissen JH, Amatangelo K, et al. 2008. Plant species traits are the predominant control on litter decomposition rates within biomes worldwide. Ecology Letters 11: 1065–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies GM, Bakker JD, Dettweiler-Robinson E, et al. 2012. Trajectories of change in sagebrush steppe vegetation communities in relation to multiple wildfires. Ecological Applications 22: 1562–1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz S, Cabido M. 1997. Plant functional types and ecosystem function in relation to global change. Journal of Vegetation Science 8: 463–474. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz S, Lavorel S, McIntyre S, et al. 2007. Plant trait responses to grazing – a global synthesis. Global Change Biology 13: 313–341. [Google Scholar]

- Drewa PB, Platt WJ, Moser EB. 2002. Fire effects on resprouting of shrubs in headwaters of southeastern longleaf pine savannas. Ecology 83: 755–767. [Google Scholar]

- Enright NJ, Fontaine JB, Lamont BB, Miller BP, Westcott VC. 2014. Resistance and resilience to changing climate and fire regime depend on plant functional traits. Journal of Ecology 102: 1572–1581. [Google Scholar]

- Enright NJ, Fontaine JB, Bowman DMJS, Bradstock RA, Williams RJ. 2015. Interval squeeze: altered fire regimes and demographic responses interact to threaten woody species persistence as climate changes. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 13: 265–272. [Google Scholar]

- Fairman TA, Bennett LT, Tupper S, Nitschke CR. 2017. Frequent wildfires erode tree persistence and alter stand structure and initial composition of a fire-tolerant sub-alpine forest. Journal of Vegetation Science 28: 1151–1165. [Google Scholar]

- Fairman TA, Bennett LT, Nitschke CR. 2019. Short-interval wildfires increase likelihood of resprouting failure in fire-tolerant trees. Journal of Environmental Management 231: 59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost CC. 1998. Presettlement fire frequency regimes of the United States. Proceedings of the 20th Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference 2: 70–81. [Google Scholar]

- Funk JL, Larson JE, Ames GM, et al. 2017. Revisiting the Holy Grail: using plant functional traits to understand ecological processes. Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 92: 1156–1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnier E, Laurent G, Bellmann A, et al. 2001. Consistency of species ranking based on functional leaf traits. New Phytologist 152: 69–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glitzenstein J, Streng D, Wade D. 2003. Fire frequency effects on longleaf pine (Pinus palustris P. Miller) vegetation in Southern Carolina and Northeast Florida, USA. Natural Areas Journal 23: 22–37. [Google Scholar]

- Gray JB, Sorrie BA, Wall W. 2016. Canebrakes of the Sandhills Region of the Carolinas and Georgia: fire history, canebrake area, and species frequency. Castanea 81: 280–291. [Google Scholar]

- Grime JP, Fridley JD, Askew AP, Thompson K, Hodgson JG, Bennett CR. 2008. Long-term resistance to simulated climate change in an infertile grassland. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 105: 10028–10032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grootemaat S, Wright IJ, van Bodegom PM, Cornelissen JHC, Cornwell WK. 2015. Burn or rot: leaf traits explain why flammability and decomposability are decoupled across species. Functional Ecology 29: 1486–1497. [Google Scholar]

- Hammill K, Penman T, Bradstock R. 2016. Responses of resilience traits to gradients of temperature, rainfall and fire frequency in fire-prone, Australian forests: potential consequences of climate change. Plant Ecology 217: 725–741. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkins EJ. 1958. Effects of fire on undergrowth vegetation in upland Southern pine forests. Ecology 39: 36–46. [Google Scholar]

- Jung V, Violle C, Mondy C, Hoffmann L, Muller S. 2010. Intraspecific variability and trait-based community assembly. Journal of Ecology 98: 1134–1140. [Google Scholar]

- Jung V, Albert CH, Violle C, Kunstler G, Loucougaray G, Spiegelberger T. 2014. Intraspecific trait variability mediates the response of subalpine grassland communities to extreme drought events. Journal of Ecology 102: 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Just MG, Hohmann MG, Hoffmann WA. 2016. Where fire stops: vegetation structure and microclimate influence fire spread along an ecotonal gradient. Plant Ecology 217: 631–644. [Google Scholar]

- Keeley JE. 2016. Seed germination and life history syndromes in the California chaparral. The Botanical Review 57: 81–116. [Google Scholar]

- Keeley JE, Brennan TJ. 2012. Fire-driven alien invasion in a fire-adapted ecosystem. Oecologia 169: 1043–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraft NJB, Ackerly DD. 2010. Functional trait and phylogenetic tests of community assembly across spatial scales in an Amazonian forest. Ecological Monographs 80: 401–422. [Google Scholar]

- Laughlin DC, Moore MM, Fulé PZ. 2011. A century of increasing pine density and associated shifts in understory plant strategies. Ecology 92: 556–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason NWH, de Bello F, Doležal J, Lepš J. 2011. Niche overlap reveals the effects of competition, disturbance and contrasting assembly processes in experimental grassland communities. Journal of Ecology 99: 788–796. [Google Scholar]

- McCune B, Grace JB. 2002. Analysis of ecological communities. Gleneden Beach, OR: MjM Software Design. [Google Scholar]

- McGill BJ, Enquist BJ, Weiher E, Westoby M. 2006. Rebuilding community ecology from functional traits. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 21: 178–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messier J, McGill BJ, Lechowicz MJ. 2010. How do traits vary across ecological scales? A case for trait-based ecology. Ecology Letters 13: 838–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midgley JJ. 1996. Why the world’s vegetation is not totally dominated by resprouting plants; because resprouters are shorter than reseeders. Ecography 19: 92–94. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell RM, Bakker JD. 2014. Intraspecific trait variation driven by plasticity and ontogeny in Hypochaeris radicata. PLoS One 9: e109870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell RM, Wright JP, Ames GM. 2017. Intraspecific variability improves environmental matching, but does not increase ecological breadth along a wet-to-dry ecotone. Oikos 126: 988–995. [Google Scholar]

- Niu K, He J, Lechowicz MJ. 2016. Grazing-induced shifts in community functional composition and soil nutrient availability in Tibetan alpine meadows. Journal of Applied Ecology 53: 1554–1564. [Google Scholar]

- Noss RF. 1989. Longleaf pine and wiregrass: keystone components of an endangered ecosystem. Natural Areas Journal 9: 211–213. [Google Scholar]

- Ojeda F, Brun FG, Vergara JJ. 2005. Fire, rain and the selection of seeder and resprouter life-histories in fire-recruiting, woody plants. New Phytologist 168: 155–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson MS, Platt WJ. 1995. Effects of habitat and growing season fires on resprouting of shrubs in longleaf pine savannas. Vegetatio 119: 101–118. [Google Scholar]

- Outcalt KW, Brockway DG. 2010. Structure and composition changes following restoration treatments of longleaf pine forests on the Gulf Coastal Plain of Alabama. Forest Ecology and Management 259: 1615–1623. [Google Scholar]

- Pechony O, Shindell DT. 2010. Driving forces of global wildfires over the past millennium and the forthcoming century. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 107: 19167–19170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peet RK, Allard DJ. 1993. Longleaf pine-dominated vegetation of the southern Atlantic and eastern Gulf Coast region, USA. In: Hermann SM, ed. Proceedings of the Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference No. 18. The Longleaf Pine Ecosystem: Ecology, Restoration and Management. Tallahassee, FL: Tall Timbers Research Station, 45–81. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Harguindeguy N, Díaz S, Garnier E, et al. 2013. New handbook for standardised measurement of plant functional traits worldwide. Australian Journal of Botany 167–234. [Google Scholar]

- Pescador DS, De Bello F, Valladares F, Escudero A. 2015. Plant trait variation along an altitudinal gradient in Mediterranean high mountain grasslands: controlling the species turnover effect. PLoS One 10: e0118876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poorter H, Niinemets Ü, Poorter L, Wright IJ, Villar R. 2009. Causes and consequences of variation in leaf mass per area (LMA): a meta-analysis. New Phytologist 182: 565–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich PB, Wright IJ, Cavender-Bares J, et al. 2003. The evolution of plant functional variation: traits, spectra, and strategies. International Journal of Plant Sciences 164: S143–S164. [Google Scholar]

- Saura-Mas S, Shipley B, Lloret F. 2009. Relationship between post-fire regeneration and leaf economics spectrum in Mediterranean woody species. Functional Ecology 23: 103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Shipley B, Lechowicz MJ, Wright I, Reich PB. 2006. Fundamental trade-offs generating the worldwide leaf economics spectrum. Ecology 87: 535–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siefert A, Ritchie ME. 2016. Intraspecific trait variation drives functional responses of old-field plant communities to nutrient enrichment. Oecologia 181: 245–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siefert A, Violle C, Chalmandrier L, et al. 2015. A global meta-analysis of the relative extent of intraspecific trait variation in plant communities. Ecology Letters 18: 1406–1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorrie BM, Grey JB, Crutchfield PJ. 2006. The vascular flora of the longleaf pine ecosystem of Fort Bragg and Weymouth Woods, North Carolina. Castanea 71: 127–159. [Google Scholar]

- de Souza MC, Rossatto DR, Cook GD, et al. 2016. Mineral nutrition and specific leaf area of plants under contrasting long-term fire frequencies: a case study in a mesic savanna in Australia. Trees - Structure and Function 30: 329–335. [Google Scholar]

- Stambaugh MC, Guyette RP, Marschall JM. 2011. Longleaf pine (Pinus palustris Mill.) fire scars reveal new details of a frequent fire regime. Journal of Vegetation Science 22: 1094–1104. [Google Scholar]

- Swenson NG, Weiser MD. 2010. Plant geography upon the basis of functional traits: an example from eastern North American trees. Ecology 91: 2234–2241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thaxton JM, Platt WJ. 2006. Small-scale fuel variation alters fire intensity and shrub abundance in a pine savanna. Ecology 87: 1331–1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tukey JW. 1977. Exploratory data analysis. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Venn SE, Green K, Pickering CM, Morgan JW. 2011. Using plant functional traits to explain community composition across a strong environmental filter in Australian alpine snowpatches. Plant Ecology 212: 1491–1499. [Google Scholar]

- Violle C, Enquist BJ, McGill BJ, et al. 2012. The return of the variance: intraspecific variability in community ecology. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 27: 244–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weakley AS, Schafale MP. 1991. Classification of pocosins of the Carolina coastal plain. Wetlands 11: 355–375. [Google Scholar]

- Westoby M. 1998. A leaf-height-seed (LHS) plant ecology strategy scheme. Plant and Soil 199: 213–227. [Google Scholar]

- Wright IJ, Reich PB, Westoby M, et al. 2004. The worldwide leaf economics spectrum. Nature 428: 821–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright JP, Ames GM, Mitchell RM. 2016. The more things change, the more they stay the same? When is trait variability important for stability of ecosystem function in a changing environment. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 371: 20150272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.