Summary

Sugar‐sweetened beverages (SSBs) are a primary source of added sugars in the American diet. Habitual SSB consumption is associated with obesity and noncommunicable disease and is one factor contributing to U.S. health disparities. Public health responses to address marketing‐mix and choice‐architecture (MMCA) strategies used to sell SSB products may be required. Thus, our goal was to identify original research about stocking and marketing practices used to sell SSB in U.S. food stores. We used Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) and the World Health Organization (WHO) protocol for rapid reviewing. We searched six databases and Google Scholar using key terms focused on store type and SSB products. We characterized results using an MMCA framework with categories place, profile, portion, pricing, promotion, priming or prompting, and proximity. Our search resulted in the identification of 29 articles. Most results focused on profile (e.g., SSB availability) (n = 13), pricing (e.g., SSB prices or discounts) (n = 13), or promotion (e.g., SSB advertisements) (n = 13) strategies. We found some evidence of targeted MMCA practices toward at‐risk consumers and differences by store format, such as increased SSB prominence among supermarkets. The potential for systematic variations in MMCA strategies used to sell SSB requires more research. We discuss implications for public health, health equity, and environmental sustainability.

Keywords: choice architecture, food environment, SSB, SSB marketing, SSB stocking, sugar‐sweetened beverage, sugary drinks

1. INTRODUCTION

Sugar‐sweetened beverages (SSB) or drinks with energy‐dense sweeteners (e.g., brown sugar, corn sweeteners and syrups, dextrose, fructose, glucose, honey, lactose, malt syrup, maltose, molasses, raw sugar, and sucrose) 1 , 2 are a main source of added sugars and discretionary kilocalories (kcals) in the American diet. 2 , 3 A 20 fluid‐ounce soda has around 264 kcals from 66 g or 16.5 teaspoons of added sugars, 4 exceeding American Heart Association (AHA) and 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA) daily intake recommendations in one container. 1 , 5 Specifically, the DGA advises less than 10% of total daily kcals come from added sugars (<200 kcals for an average 2000‐kcal diet), 1 and the AHA recommends daily added sugars intake not exceed six teaspoons for women and children and nine teaspoons for men. 5

Total added sugars from foods and beverages accounted for an estimated 14% of adults' and 17% of children's total daily kcals in 2012, with the majority coming from SSB products. 3 Around 54% of U.S. men and 45% of U.S. women have reported consuming at least one SSB per day, 6 with the highest frequency of consumption among at‐risk groups. 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 Habitual SSB consumption is associated with a high prevalence of obesity and noncommunicable disease (NCD), namely, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and some cancers. 5 , 13 , 14 , 15 Given intake differences, 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 SSB products are one variable driving inequitable health outcomes among U.S. rural, low‐income, and racial/ethnic minority populations. 7 , 8 , 9 , 16 Public health responses are required to improve consumer dietary quality and mitigate health disparities.

One mechanism to improve Americans' dietary quality is SSB taxation, which has been the focus of numerous reviews. Evidence has shown taxes to favorably change consumers' dietary behaviors, 17 , 18 , 19 even among at‐risk populations, 19 albeit issues with store management and consumer acceptability in some cities. 20 , 21 SSB taxation has also been shown to change consumer food environments by raising SSB purchase prices. 22 However, price is only one factor influential on consumer decision making. 23 , 24 Taxation could prompt SSB manufacturers and retailers to use comprehensive marketing‐mix and choice architecture strategies to improve sales. 22 U.S. beverage manufacturers and food retailers cater to consumer demand to maximize business profit, 25 although evidence suggests the prominence of energy‐dense and nutrient‐poor products within retail spaces drives the selection of affordable, palatable, and unhealthy choices beyond consumers' immediate awareness, 24 , 26 , 27 , 28 especially among at‐risk populations with fewer resources 29 , 30 who may be disproportionally targeted. 16 , 31 , 32

In the United States, consumers purchase the majority of SSB products from convenience, mass merchandizer, dollar, and drug stores, in addition to using traditional supermarkets or grocers. 33 These retailers are often authorized to accept federal nutrition assistance benefits, including the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and Special Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), providing a viable entry point for policy change 34 due to retailer stocking requirements for SNAP and/or WIC authorization. 35 , 36 We use a marketing‐mix and choice‐architecture (MMCA) framework 23 that combines marketing and behavioral economic principles to describe strategies used for food and beverage sales to explore SSB product stocking and marketing. For example, strategies used to sell SSB products in U.S. food stores might include 23 , 37 manipulations to the retail atmosphere or infrastructure, such as with music or through beverage cooler additions (MMCA category place); 38 SSB product availability or product nutrient characteristics (MMCA category profile); varied SSB product sizes (MMCA category portion); SSB advertisements (MMCA category promotion); SSB displays or labeling strategies to increase product prominence (MMCA category priming or prompting); and calculated SSB product placements in impulse selection areas (MMCA category proximity). 23 , 24 , 37 The purpose of our review was to understand MMCA strategies used to sell SSB products in U.S. food stores. This topic area is consistent with global public health and sustainability targets outlined in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 39 , 40 , 41 , 42

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

We used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) 43 and a policy‐oriented rapid reviewing protocol published by the World Health Organization. 44 We used these guidelines to inform opportunities for food retail changes to improve public health and highlight research areas needed to inform policy change. Before searches began, we registered a review protocol with International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) although we completed the review before registration processed. Coauthors are from multiple disciplines and are topic experts on issues relevant to nutrition, marketing, and economics.

2.1. Literature search

On the basis of results from preliminary search tests, we chose six academic databases (Table 1) and Google Scholar for systematic searching. We constructed key terms to search for relevant research in November 2019. Stakeholder feedback received during a preliminary results forum organized by the Center for Science in the Public Interest, The Food Trust, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, and Healthy Eating Research informed an updated key term strategy that was used for searching in January and in April 2020.

TABLE 1.

Key search terms used in academic databases a and Google Scholar b to identify literature relevant to stocking and marketing practices in U.S. food stores

| Key terms: Context | Key terms: Product |

|---|---|

| Supermarket OR grocery OR grocer OR bodega OR “full‐service store” OR “limited‐service store” OR “food store” OR store OR “food environment” OR “consumer food environment” OR “nutrition environment” OR “food retail” OR retail OR convenience OR dollar OR “drug store” OR pharmacy OR “super center” OR club OR “mass merchandiser” | “sugar‐sweetened beverage” OR SSB OR “sugary drink” OR soda OR pop OR juice OR “energy drink” OR “soft drink” OR “sport drink” OR “flavored milk” OR “chocolate milk” OR “strawberry milk” OR “sweet tea” OR “sweetened water” OR “sweetened beverage” OR “added sugar” OR “soda tax” c OR “beverage tax” c |

Academic Search Complete, Environment Complete, PubMed, PsycINFO, MEDLINE, and Business Source Complete.

Phrases using stated key terms were used to search the first 100 (November 2019) and 20 (April 2020) sources (due to lack of relevance observed on later search pages).

Stocking and marketing differences related to SSB taxation were of interest, although a review on this topic specific to product pricing was identified. 22 Therefore, data about SSB taxation and outcomes related to other marketing‐mix and choice‐architecture strategies aside from price (e.g., promotions) were of interest to review scope.

Key terms focused on context (store setting) and product (SSB type) (Table 1). When possible, the lead author (BH) searched databases concurrently to preremove duplications and restricted searches to include only U.S. peer‐reviewed articles published between January 2013 and April 2020 to reduce the number of sources requiring title/abstract review. The lead author (BH) extracted search results to EndNote X9 and reviewed source titles and abstracts to assess full‐text relevance. This procedure represents the main variation of the current study from traditional systematic review methods. 44 All authors reviewed reference lists of included articles to locate potential sources not identified in searches.

The year 2013 was chosen as a search parameter due to public policy and beverage industry campaigns that may have influenced SSB stocking and marketing practices in food stores. 45 In 2013, the Partnership for Healthier America launched the “Drink Up” campaign in coordination with industry partners to encourage U.S. consumers to purchase and consume more water (rather than SSB products). 46 , 47 In 2015, the American Beverage Association alongside The Coca‐Cola Company, Keurig Dr. Pepper, and PepsiCo launched the Balance Calories Initiative (BCI), 48 , 49 committing to responsible SSB product labeling and marketing practices.

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included original, peer‐reviewed research articles published during or after the year 2013 about SSB stocking and marketing practices used in U.S. food stores. We referred to a 2017 USDA report to define “food store” (i.e., supermarkets, drug stores, mass merchandizers, supercenters, convenience stores, dollar stores, and club stores). 50 We limit the focus to the United States to allow for a discussion of U.S. policy implications, given a unique policy climate relative to other high‐income countries. We did not include restrictions by the type of research design or sample, although results were required to be specific only to SSB products. For example, results combining “unhealthy” products (e.g., SSB, candy, and confections) were not eligible if findings specific to SSB were not distinguishable. We did not include theses or dissertations and commentary or perspective pieces. We also excluded research describing the influence of environmental interventions 39 and taxation 17 , 18 , 19 , 22 on consumer SSB consumption or store pricing strategies, as these topics have been reviewed previously. However, we were interested in results about the use of other MMCA strategies (aside from price changes) resultant from SSB taxation, as this has not been a focus of previous reviews.

2.3. Main outcomes

We categorized data about SSB stocking and marketing practices by best fit using a MMCA framework, 23 including seven categories relevant to food store settings (i.e., place, profile, portion, pricing, promotion, priming or prompting, and proximity). 23 , 37 We provide brief examples of the framework throughout and direct readers to Kraak et al. (2017) for additional information. 23

We assessed article quality with the 2018 Mixed‐Method Appraisal Tool, 51 , 52 , 53 chosen based on tool capacity to assess quality among several research designs, including qualitative, nonrandomized, quantitative descriptive, and mixed‐method research. The tool characterizes study quality among seven indicators, and a higher number of “can't tell” or “no” versus “yes” responses were used to indicate reduced quality. 51 , 52 , 53 We used a standardized spreadsheet to extract outcome data, and agreement on all data extraction indicators was reached between two authors.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Search yields

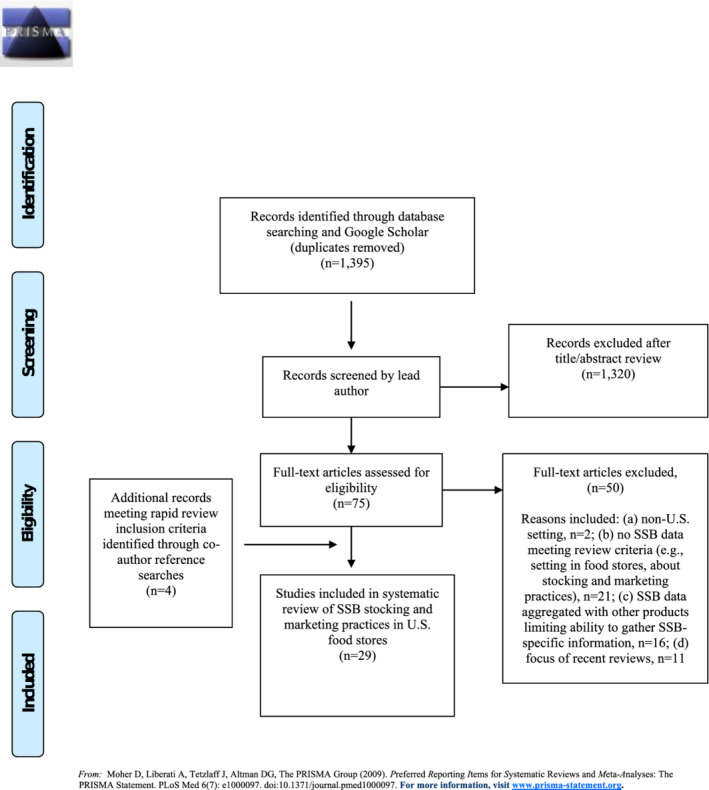

We identified 29 articles meeting review inclusion criteria. 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 80 , 81 Refer to Figure 1 for a flow diagram of search results. Most studies were classified as quantitative descriptive research (n = 24 articles; 83%) (Table 1). Data about SSB stocking and marketing practices were collected from at least 22,126 unique food stores (some did not specify store number), with stores located in urban areas represented more frequently than those in rural areas (Table 1). Data collected from store management (n = 12 participants), 57 caregiver–youth dyads (n = 847 dyads), 66 and parents (n = 49 participants) 71 were also included as results provided perceptions about stocking and marketing practices used in food stores. Study quality of included articles was generally high. Unfavorable (“can't tell” or “no”) responses using the Mixed‐Method Appraisal Tool ranged from 0 to 4 out of a possible 7 (mean 1.66). Table 2 includes study information extracted among all articles.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of articles identified for review inclusion using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) search guidelines

TABLE 2.

Original research included in a rapid review of sugar‐sweetened beverage (SSB) stocking and marketing practices in U.S. food stores (n = 29)

| First author and publication year | Design | Objective | Location a | Participant/store characteristics | Data collection measures | Definition of SSB used in study | Unfavorable quality review responses b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjoian, 2014 | Quantitative descriptive | To investigate SSB availability, marketing, and pricing among locations with higher and lower resident SSB consumption | Urban: New York City, NY. Higher and lower consumption areas: South Bronx; Central Harlem and Upper West Side (Manhattan); East New York and Greenpoint (Brooklyn); and Astoria (Queens) |

518 stores in higher consumption areas: corner stores, n = 443; chain; chain pharmacies, n = 12; grocery stores, n = 63 469 stores in lower‐consumption areas: corner stores, n = 365; chain pharmacies, n = 21; grocery stores, n = 83 |

Tool developed by study authors to measure availability, price, and advertisements in store exterior/interior. Pretested (n = 29) for feasibility and interrater reliability | Drinks with added caloric sweeteners, >25 kcals per 8 fluid‐ounce (fl. oz.) serving. SSBs included soda, sports drinks, energy drinks, iced tea, fruit drinks, and vitamin‐enhanced water (VITAMINWATER and True Colors) | 1 |

| Barnes, 2014 | Quantitative descriptive | To characterize advertisements for healthy and less healthy foods and beverages | Urban: Minneapolis–St. Paul, MN | 119 stores: corner/small grocery stores, n = 46; food/gas marts, n = 51; dollar stores, n = 9; pharmacies, n = 13 | Adapted food availability and marketing survey (CX3) to assess advertisements and product placement. Noted to have good interrater and test–retest reliability | Soft drinks and other sweetened beverages | 1 |

| Basch, 2016 | Quantitative descriptive | To characterize candy and snack food availability in checkout lanes | Urban: Kingston, NY | 2 department stores. Other stores were assessed that did not meet review inclusion criteria for food store | Presence of target products and their proximity to the cash register were recorded | Soft drinks/soda | 2 |

| Bogart, 2019 | Qualitative | To assess awareness and perceptions of the balance calories initiative (BCI) among key stakeholders | Urban and rural: Montgomery, AL (urban); North Mississippi Delta, MS (rural); and Eastern Los Angeles, CA (urban) | 6 managers of supermarkets and 6 of convenience stores. Other participants did not meet review inclusion criteria for food store | Semi‐structured interviewing using a think‐aloud process in response to BCI marketing materials | BCI‐represented SSB brands: Coca‐Cola Co.; PepsiCo, Inc.; Keurig; and Dr. Pepper | 0 |

| Cohen, 2015 | Quantitative descriptive | To observe placement and price reduction strategies in food retail outlets | Urban: Pittsburg, PA | 43 stores: supermarket, n = 8; neighborhood store, n = 18; supercenter/wholesale, n = 5; chain convenience, n = 4; dollar, n = 1; and specialty, n = 4 | Bridging the Gap Food Store Observation Form (BTG‐FSOF). Shown reliable | SSB not defined | 3 |

| Cohen, 2018 | Quantitative descriptive | To determine quantity and prominence of SSBs in stores exposed to the BCI | Urban and rural: Birmingham and Montgomery, AL (urban); Boyle Heights, Los Angeles, CA (urban); North and South Delta, MS (rural) | 52 supermarkets/grocers and 17 convenience stores among five study sites | Store scoresheet to measure SSB availability, marketing, and price. Interrater reliability (Kappa 0.96) tested among sample subset | Beverages with added sugar and >40 kcal/serving. Included flavored milk | 1 |

| Ethan, 2013 | Quantitative descriptive | To assess the nutritional quality of foods advertised in grocery store circulars | Urban: New York City, NY (Bronx) | 15 chain grocers | Coding scheme used to assess product, food group, price, processed/unprocessed, serving size, grams sugar/serving for SSB | SSBs including sodas, sports and energy drinks, fruit drinks, and other beverages like tea and coffee drinks, and sweetened milk or milk alternatives to which high‐fructose corn syrup or sucrose was added | 2 |

| Evans, 2018 | Quantitative descriptive | To assess cost of groceries by energy density and to determine costs differences by metric used | Urban and rural: Rochester, NY (urban) and surrounding area in Monroe County | 60 grocery stores | Standardized assessment of product price, brand, size, cost, and nutrition facts label information | SSBs chosen from What We Eat in America survey. Included fruit juice drinks (regular and reduced sugar), 25% juice, Gatorade® or generic sports drinks, soft drinks, and sweet tea | 1 |

| Futrell Dunaway, 2017 | Nonrandomized | To conduct a financial analysis and evaluate an infrastructure project regarding the stocking of fruits and vegetables and consumer awareness | Urban: New Orleans, LA | 1 corner grocery store | Store‐intervention partnerships allowed sharing of inventory and sales data | All SSB, such as carbonated, uncarbonated, sports and energy drinks, teas, and coffees | 2 |

| Grigsby‐Toussaint, 2013 | Quantitative descriptive | To document the marketing of dietary products among stores frequented by mothers of young children | Urban: Urbana and Champaign, IL | 24 stores: grocery, n = 12; and convenience, n = 12 | Reliable and validated food store audit | Soda and juice | 2 |

| Harris, 2020 | Quantitative descriptive | To characterize child‐focused marketing for fruit drinks | Urban: eight U.S. diverse cities (not specified) | Supermarkets (n unknown) | Weekly sales data sourced from IRiWorldwide | Juice drinks (e.g., fruit‐flavored or juice drinks that contain added sugar) sold in ≤20 fl. oz. containers (e.g., child focus) | 2 |

| Isgor, 2016 | Quantitative descriptive | To assess outdoor exterior food and beverage advertisement prevalence respective to community characteristics | Urban and rural: nationwide sample | 8021 stores: supermarkets/grocers, n = 1684; and limited service with no fresh meat, n = 6337 | BTG‐FSOF to document availability, price, and promotion of foods and beverages. Shown reliable | Regular (nondiet) soda | 2 |

| Jilcott Pitts, 2016 | Quantitative descriptive | To examine promotional properties in support of healthy dietary behaviors | Urban and rural: Greenville (urban) and Kinston (rural), NC | 9 stores (not characterized by format) | BTG‐FSOF to document availability, price, and promotion of foods and beverages. Shown reliable | Juice drinks, regular soda, energy drinks, and isotonic sports drinks | 1 |

| Kern, 2016 | Quantitative descriptive | To examine variation in milk and soda prices and the price of milk relative to soda by community characteristics | Urban and rural: 41 states and Washington, DC | 1743 large U.S. chain supermarkets. | Price data from a market research group Information Resources, Inc | Brand‐name sugar‐sweetened sodas (e.g., Coke, Pepsi, Sprite) | 3 |

| Kumar, 2014 | Quantitative descriptive | To examine exposure to food and beverage marketing | Urban and rural: nationwide probability sample | 847 caregiver and youth (aged 12–17) dyads | Youth Styles Survey and the Consumer Styles Survey to measure frequency of advertisement exposure and exposure settings (i.e., school, supermarkets/grocers, convenience store/gas station, television, internet or cell phone) | Soda (Coke, Sprite, and Mountain Dew), fruit drinks (Capri Sun, Sunny Delight, and Hawaiian Punch), sports drinks (Gatorade or Powerade), and energy drinks (Red Bull, 5‐hour Energy, and NOS) | 2 |

| Leider, 2019 | Quantitative descriptive | To associate SSB prices with beverage, size, sale status, store type, and community characteristics | Urban: Cook County, IL; St. Louis, MO; and Oakland and Sacramento CA | 581 stores: supermarkets, n = 116; grocers, n = 66; chain convenience, n = 133, nonchain convenience, n = 199; small discount, n = 33; and drug/pharmacy, n = 78 | Beverage Tax Food Store Observation form adapted from two tools (BTG‐FSOF) and Illinois Prevention Research Center (IPRC) Nutrition and Obesity Policy Research Evaluation Network (NOPREN) Food Store Observation Form). Found reliable | Soda, sports drinks, energy drinks, non‐100% juice drinks, and ready‐to‐drink tea/coffee | 1 |

| López, 2014 | Quantitative descriptive | To assess online coupon incentives among retailers | Urban and rural: United States locations (unspecified) | 6 chain grocery stores | Online coupons intended for in‐store use were reviewed weekly. An adapted MyPlate was used to characterize coupons | Sodas, juices, and energy/sports drinks | 2 |

| Lucan, 2020 | Quantitative descriptive | To investigate changes over time in the food environment regarding food and drink product availability | Urban: New York City, NY | 17 food stores in 2016 and follow up in 2017 (n = 16 stores) | Observation form with in‐depth training and reliability checks used | Less‐healthful drinks, categorized as sugary drinks | 3 |

| Martin‐Biggers, 2013 | Quantitative descriptive | To use describe the types of products advertised in newspaper grocery sales circulars | Urban and rural: 50 states and Washington, DC | 51 top supermarket retailers based on data from 2011 | An instrument developed by study authors to assess the first page of circulars for product information and size of advertisements. Coding manuals, training, and multi‐coder agreement were used | SSB was categorized under “sweets” category and analyzed as a subgroup in a post hoc test | 0 |

| Moran, 2018 | Quantitative descriptive | To examine differences in beverage marketing during periods of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefit issuance overall and by community characteristics | Urban: Albany, Buffalo, and Syracuse, NY | 630 chain and 264 nonchain SNAP stores: convenience, n = 166; pharmacy, n = 77; large grocers, n = 47; small grocers, n = 231; and other (e.g., mass merchandizers), n = 109 | Scan of Nutrition Environment Measures Survey in Stores (NEMS‐S) and Retail Assessment of Tobacco Stores data for information about SSB availability, cost, and marketing | Nonalcoholic beverages containing added caloric sweeteners, >25 kcals/8 fl. oz | 3 |

| Penilla, 2017 | Qualitative | To understand parents' perceptions about environmental barriers to obesity prevention and child diet and physical activity behaviors | Urban: San Francisco, CA | 49 Latino (Mexican, Guatemalan or Salvadoran) parents: mothers, n = 27; fathers, n = 22 | Focus group questions related to soda consumption | Soda | 0 |

| Powell, 2016 | Quantitative descriptive | To characterize price promotions by product healthfulness, store type, and community characteristics | Urban and rural: U.S. communities (n = 468) representative of public middle and high school student | 8959 stores: supermarkets with fresh meat and multiple registers/service counters, n = 955; grocers with fresh meat, n = 870; and limited service (e.g., convenience, drug, dollar), n = 7134 | BTG‐FSOF to assess price promotions. Found reliable | SSB types included family and individual sizes of <50% juice drinks, ≤10% juice box/pouches, regular soda (i.e., Coca‐Cola or Pepsi), energy drinks, isotonic sports drinks, and enhanced water | 1 |

| Racine, 2016 | Quantitative descriptive | To document the types of dietary products available at SNAP‐authorized dollar stores and assess differences by chain and community characteristics | Urban and rural: 16 counties in southern and western areas of NC | 90 chain dollar stores: Dollar General, n = 30; Dollar Tree, n = 30; and Family Dollar, n = 30 | Adapted food environment observation tool used in other food store research to capture specified foods and beverages. Interrater reliability (88%) assessed among 5 stores for 100 variables | Multiserving size units of soda | 1 |

| Racine, 2017 | Quantitative descriptive | To characterize dietary products available in SNAP‐authorized drug stores by chain and community characteristics | Urban and rural: 25 counties in NC including Asheville, Charlotte, and Durham | 108 drug store chains: Rite Aid, n = 36; CVS, n = 36; and Walgreens, n = 36 | Adapted food environment observation tool used in other food store research to capture specified foods and beverages. Pilot tested for interrater reliability (84%) | Sports drinks, energy drinks, energy shots, regular soda, SSB (not soda) | 1 |

| Robles, 2019 | Mixed‐method | To provide information and details about lessons learned coordinating a SNAP‐Ed Small Corner Store Project regarding planning and programming | Los Angeles County, CA (urban) | 12 stores: convenience, n = 10; variety, n = 1; butcher (e.g., carniceria), n = 1. Convenience stores often also coded as variety stores, butcher, and/or liquor stores | Internally developed tool that assessed shelf space, internal and external ads, and produce varieties | SSB | 4 |

| Ruff, 2016 | Quantitative descriptive | To characterize adult shopping behaviors and store properties influential on consumer behavior | Urban: New York City, NY | 171 bodegas | Store assessment form to measure availability and location for produce, water, SSB, diet beverages, and alcohol. Pilot tested for usability | Carbonated or uncarbonated, manufacturer‐sweetened (nonalcoholic) beverages with sugar or other caloric sweeteners, >25 kcal/8 fl. oz. Milk not included | 1 |

| Singleton, 2017 | Quantitative descriptive | To capture the availability of foods and beverages in communities eligible for the Healthy Food Financing Initiative | Urban: Chicago and Rockford, IL. | 127 stores: small grocery, n = 34; and limited‐service sites with no fresh meat, n = 93 | IPRC‐NOPREN Food Store Observation Form. Found reliable | Juice (<50%) or juice drinks, regular soda, and enhanced water with sugar, sweeteners, artificial flavoring, vitamins, and/or minerals | 3 |

| Thornton, 2013 | Quantitative descriptive | To investigate produce, snack food, and soft drink availability in checkouts and end‐aisle displays internationally | Urban: In the United States, Columbia, SC; Philadelphia, PA; and Bethesda/Washington, DC | 32 supermarkets: Acme, n = 1; Bi‐Lo, n = 3; Bottom Dollar, n = 1; Fresh Grocer, n = 2; Fresh Market, n = 1; Food Lion, n = 5; Giant, n = 4; Harris Teeter, n = 2; Kroger, n = 1; Piggly Wiggly, n = 3; Safeway, n = 4; Sams, n = 1; Save a Lot, n = 1; Shop n Bag, n = 1; Superfresh, n = 1; and Trader Joes, n = 1 | Standardized audit tool to measure product shelf space and availability. Implementer training used | Diet and regular soda | 2 |

| Zenk, 2020 | Nonrandomized | To understand changes to store marketing practices resulting from a 1 cent/fl. oz. SSB tax in Oakland, CA | Urban: Oakland and Sacramento, CA | 249 stores: supermarkets, n = 76; limited service, n = 173 | Beverage Tax Food Store Observation Form to assess exterior and interior advertisements and price promotions. Found reliable. | Regular soda, regular sports drinks, regular energy drinks, juice drinks, ready‐to‐drink coffees/teas with least 25 kcals/12 fl. oz | 1 |

When study site designation as urban or rural was unclear a database was used (https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/am‐i‐rural).

Quality assessed using the 2018 Mixed Method Appraisal Tool. Number of unfavorable responses indicates number of “no” or “can't tell” responses (rather than “yes”) noted among seven quality indicator questions by study design.

We observed variations in SSB stocking and marketing practices by store type (n = 12 articles; 41%) and by consumer sociodemographic characteristics, including income (n = 6 articles; 21%), race/ethnicity (n = 3 articles; 10%), location (n = 4 articles; 14%), and consumer SSB consumption patterns (n = 2 articles; 7%) (Table 3). Table 3 provides detailed results specific to MMCA categories place, profile, portion, pricing, promotion, priming or prompting, and proximity strategies used to sell SSB products.

TABLE 3.

Results specific to seven marketing‐mix and choice‐architecture (MMCA) categories regarding stocking and marketing practices used to sell sugar‐sweetened beverages (SSBs) in U.S. food stores

| MMCA category definition | References | Results |

|---|---|---|

|

Place Light, sound (esthetic), or cooler/shelving installation (infrastructure) used to stock SSB products 23 , 38 |

Bogart, 2019 57 | Managers explained beverage manufacturers might install the store coolers. Although some also indicated managers had final approval regarding the store location of manufacturer installments and could move coolers without informing the companies. |

|

Profile Stocked varieties of SSB products and/or the nutrient composition of available SSB products 23 , 38 |

Adjoian, 2014 54 | A mean of 11.0 SSB varieties were documented among stores compared with a mean of 4.7 low‐kcal beverage alternatives. |

| Bogart, 2019 57 | Manufacturers, in some cases, held formal stocking agreements for shelf space with store management. Some believed obesity reduction would only occur with reformulated SSB products with less sugar and a similar taste. | |

| Cohen, 2018 58 |

SSB products were the most prevalent beverages among study settings. Differences by community characteristics: East Los Angeles, California stores commonly had SSB varieties from Mexican brands. |

|

| Futrell Dunaway, 2017 61 | On average, 1142 SSB products were available in stores, which was less than snack items and “other” food/nonfood items. | |

| Grigsby‐Toussaint, 2013 62 |

Juice and soda were available in all stores that accepted Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) benefits. |

|

| Jilcott Pitts, 2016 64 | Most stores were found to have all SSB items available (range 6–7 out of a possible 0–7). | |

| Lucan, 2020 79 | No change in SSB availability between years 2016 and 2017, 100% of stores carried SSB (same for water products). | |

| Moran, 2018 70 | Differences by community characteristics: Stores in communities with a high proportion of residents enrolled in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) were found to have increased SSB product variety during SNAP benefit issuance periods in comparison to all other days (b = 0.63, 95% CI = 0.29, 0.97). | |

| Penilla, 2017 71 | Parents discussed the abundance of soda and believed SSB availability in community stores particularly influenced children's dietary choices. | |

| Racine, 2016 73 |

SSB products (1‐gallon, not soda) were available in most dollar stores (66.7%). Differences by store format: There were differences in availability by dollar store chain: SSB 1‐gallon (not soda) available in 100% of Dollar General stores, 3.3% of Dollar Tree stores, and 96.7% of Family Dollar stores; Soda, 2 L available in 100% of Dollar General stores, 3.3% of Dollar Tree stores, and 100% of Family Dollar stores. Soda, 2.5 or 3 L available in 96.7% of Dollar General stores; 96.7% of Dollar Tree stores; and 50% of Family Dollar store. (Statistically significant) |

|

| Racine, 2017 74 |

Sports drinks, energy drinks, regular soda, and other SSB products were available in all drug stores (regardless of community income or food desert status). Energy shots were also highly available (77.4%). Differences by store format: Energy shot availability significantly differed by chain: Walgreens (n = 30; 83.3%); Rite Aid (n = 29; 80.6%); CVS Health (n = 20; 55.6%). Differences by community characteristics: Higher availability of energy shots in community stores within high income residents (n = 33; 91.7%) vs. middle income residents (n = 22; 61.1%) (statistically significant). |

|

| Robles, 2019 75 | SSB shelf space ranged from 6.4% to 31.3% (mean 15.6%) and was proportionally higher than fruits/vegetables and/or junk food in all but three stores. | |

| Singleton, 2017 77 |

Almost all stores carried fruit punch/juice drinks (96.8%) and regular soda (97.6%) and were found in higher proportion than 100% juice varieties and diet soda, respectively. Enhanced water was documented in less than half of stores (42.7%) and was found in lower proportion than plain water. Differences by store format: More limited‐service stores had enhanced water than small grocers (48.4% vs. 27.3%) (statistically significant). Limited‐service stores were more likely than grocers to have healthier alternatives for SSB. (Not statistically significant) |

|

|

Portion Container size of SSB products that are stocked and marketed 23 , 38 |

Bogart, 2019 57 | Managers perceived reducing beverage container size could help reduce consumption. One convenience store manager shared experiences of strong consumer sales after negotiating a smaller SSB bottle size for store stocking with American Beverage Association manufacturers. |

| Cohen, 2018 58 |

Differences by store format: Mini‐cans were not available in observed convenience stores. Mini‐cans were predominantly brands of Balance Calories Initiative (BCI)‐participating companies and were found available in limited frequency among grocery stores. |

|

|

Pricing Costs (to consumers or retailers) associated with SSB products 23 , 38 |

Adjoian, 2014 54 | 18% of measured stores had sales for SSB. The majority (64%) (supermarkets and chain pharmacies; bodegas excluded) had sales for SSB while less than half had sales for healthier beverages. However, prices for SSB were not commonly posted among stores (e.g., of 883 stores, SSB prices were not posted in 524; additionally, in 40 stores, no pricing data were recorded). |

| Bogart, 2019 57 | Managers explained beverage companies commonly used coupons instead of store‐level interventions. They believed in‐store discounts on SSB were most effective for sales compared with other promotions. Coupons were described as less effective to sell SSB due to strict rules that might be confusing to consumers (e.g., expiration date). SSB was described to sell better than no/low‐kcal beverages, and management was not incentivized to target promotions at these types of beverages due to low demand (was a suggested BCI strategy). Last, management believed lower prices from beverage companies for low/no‐kcal beverages might increase consumer purchase due to their high price compared to SSB. | |

| Cohen, 2015 82 | Differences by store format: Price promotions most common in grocery stores (34%), followed by supercenter/wholesale (30%), and neighborhood stores (20%). Not identified in chain convenience, dollar, or specialty stores. (Descriptive data) | |

| Cohen, 2018 58 |

Six‐pack Coca‐Cola 8 fl. oz. glass bottles were the most expensive (range: $4.58–$5.49 or 9.5–11.4 cents/oz.). Mini‐cans noted as the next most expensive SSB that could be as low as $1.99 for six cans if on sale. On average, a 6‐pack of mini‐cans was $2.95 (6.6 cents/oz.), and an 8‐pack was $3.49 (5.8 cents/oz.). Coupons were available in one supermarket for 2 L and mini‐cans. Smaller SSB containers were higher cost than larger brand sizes (per ounce), and sales were mostly for multipack SSB products. (Descriptive data) Differences by community characteristics: 2‐L SSB bottles were as low as $1.00 (1.5 cents/oz.) in the southeastern United States (Mississippi and Alabama), with the highest cost $1.99 (2.9 cents/oz.) (average $1.51 (2.2 cents/oz.). In East Lost Angeles, California, a 2‐L bottle of Coca‐Cola was as low as $0.99, and 7‐Up was $0.89 (1.3 cents/oz.). Further, a case of 12 12‐oz. cans of Coca‐Cola ranged from $2.75 to 5.99, (1.9–4.2 cents/oz.) with an average cost of $4.21 (2.9 cents/oz.). (Descriptive data) |

|

| Ethan, 2013 59 | Of beverages offered in sale promotions, most (74%) were SSB. Promotions for multiple unit purchases were also common. | |

| Evans, 2018 60 | The unit price (per quart) was 24% lower among high energy density (ED) beverages (i.e., SSB) than low ED beverages. Energy cost (price/calories) was 30% lower among high ED beverages in comparison with low ED beverages. Cost per serving (price/serving) was 35% lower among high ED beverages than low ED beverages. High ED foods (inclusive of SSB) were found more expensive when cost was calculated per kilogram, although cheaper when calculated per calorie, per serving, and per quart. (Statistically significant) | |

| Futrell Dunaway, 2017 61 | SSB sales between July 2009 and June 2010 totaled US$ 26,085.00 and represented 9.2% of total store sales (US$ 282,541.00). Sales for SSB were observed to be higher than proportion of sales attributed to snack foods, fresh and frozen produce, and “other” food and nonfood products. Gross profit for SSB (sales/revenue – SSB product cost) was calculated as a net US$ 11,909.00 and represented 12.6% of total profits (US$ 94,441.00). Profit for SSB was higher than all other products except beer and tobacco. | |

| Harris, 2020 80 | Products with added sugars had a significantly higher percentage of sales from price reductions than products without added sugars. Child‐focused SSB products had double the sales attributed to price promotions than products without added sugar. (Statistically significant) | |

| Jilcott Pitts, 2016 64 |

SSB price ranged from $1.40 to 1.90 per unit (data not shown). Differences by community characteristics: Stores with higher‐priced SSB had consumers with higher reported SSB consumption. (Statistically significant) |

|

| Kern, 2016 65 |

Price of soda was always cheaper than the price of milk and did not vary by community characteristics. On average, one serving of soda was about 62% lower than a serving of milk, or a milk serving was 2.5 times more expensive than a serving of soda. (Statistically significant) Differences by community characteristics: Communities with a higher proportion of Hispanic/Black residents were associated with 65% lower soda prices and higher milk prices (adjusted model). Lower income areas associated with lower soda prices (magnitude of association small) with higher price of milk (adjusted model). In the southeastern United States, the price of soda relative to milk was lower, whereas the price of soda relative to milk was higher in northeast and Midwest U.S. regions. |

|

| Leider, 2019 67 |

On average, soda was documented as the cheapest SSB option. Mean price (cents/ounce) of SSB: SSB (4.8 ± 4.2); soda (3.4 ± 1.9); sports drink (4.8 ± 2.2); energy drink (19.9 ± 6.3); ready‐to‐drink coffee/tea (7.8 ± 6.3); juice drink (5.2 ± 3.3). Individual sizes were more expensive than larger family size products among SSB types. Artificially sweetened SSB products were usually comparable in price, and unsweetened options were less expensive, aside from 100% juice in comparison with the price of juice drinks. Adjusted model indicated sports drinks were on average less expensive than soda, and price is significantly, negatively associated with larger sizes. Sales lowered prices among SSB, soda, sports drinks, energy drinks (largest depth of sale, −3.74; 95% CI = −4.31, −3.17), and juice drinks. Differences by community characteristics: SSB store prices in majority (>50%) non‐Hispanic Black communities were significantly less expensive for all SSB, soda, and energy drinks than for the same products in majority non‐Hispanic White community stores. Sports and energy drinks were also less expensive among stores in communities with residents classified as “other.” A small positive association between income and soda price was found. (Statistically significant) Differences in SSB price were identified by location (reference site Cook County, Illinois). Oakland and Sacramento, California prices for all SSB, soda, and juice drinks were more expensive. Sports drinks were also identified as significantly more expensive in Oakland. Differences by store format: In comparison with supermarkets, all SSB, soda, and sports drinks were lower priced among general merchandize, grocery stores, and small discount stores than supermarkets. Also in comparison: Energy drinks were lower priced in general merchandize and grocery stores; juice drinks were lower priced among grocers; and small discount stores had lower prices for ready‐to‐drink tea/coffee and juice drinks. Chain convenience and drug/pharmacy stores all SSB, soda, and sports and juice drink products had higher prices than supermarkets, while energy drinks were higher in chain convenience stores only. Mean price for all SSB and certain categories were highest among chain convenience stores (adjusted model), followed by prices in supermarkets, nonchain convenience, and drug/pharmacy stores. |

|

| Lopez, 2014 68 | Of all store coupons, 12% were for beverages (n = 1056). Of these, 46% or 4% were for child‐focused drinks/juice, 16% or 2% were for soda, five were for sports drinks, and three were for energy drinks. Comparatively, 14% or 1% were for water. Mean number of coupons varied depending on the beverage: juice and child‐focused drinks (±7.7, range 0–22); soda (±2.7, range 0–12); sports drinks (±0.8, range 0–4); and energy drinks (±0.5, range 0–3). Comparatively, coupons for water were on average ±2.3 with a range of 0–8. | |

| Powell, 2016 72 |

Larger in comparison with smaller SSB product sizes had significantly more targeted price promotions. Price promotions were associated with significantly lower sports drinks (25.4–32.3% lower), energy drinks (11.7–18.4% lower), and enhanced water (19.8–25.2% lower) prices among all stores. Supermarkets price promoted sports drinks (26.9%), energy drinks (8.4%), and enhanced water (18.8%) more than bottled water (2.6%), and price promotions were more often for family‐sized than individual‐sized regular soda (22.6% vs. 2.5%) and larger rather than smaller juice drink containers (22.9% vs. 13.8%). Supermarket price promotions were linked with lower prices for larger family‐sized soda (17.2% lower, regular; 16.8% lower, diet) and juice drinks (21.2% lower; only 2.4 lower for 100% orange juice). (Statistically significant) Variations by community characteristics were not identified. Differences by store format: SSB price promotions in supermarkets (noted above) were generally more frequent than in grocery and limited‐service stores. (Statistically significant) |

|

| Zenk, 2020 81 | Regular soda had higher prevalence of price promotions in comparison with other SSB products. At 6‐month post‐tax, the odds of SSB price promotions fell 50% in Oakland and 22% in Sacramento. Price promotions for regular soda declined in Oakland post‐tax, by 47% at 6 months and 39% at 12 months (versus no change in Sacramento). The odds of SSB promotions fell by a similar magnitude as SSB in Oakland, 55% at 6 months and 53% at 12 months, which differed significantly from Sacramento. | |

|

Promotion Targeted signage or marketing materials for SSB products 23 , 38 |

Adjoian, 2014 54 | 93% of sampled stores advertised SSB, which was more frequent than other types of beverage advertisements. |

| Barnes, 2014 55 |

Of 117 (out of 119) stores found to have healthy product placement, 35% promoted energy drinks and 46% promoted soda; 55 stores (46%) were documented to have an exterior advertisement for a less healthy beverage, and 78 had at least one interior advertisement for a less healthy beverage. Differences by store format: 38 of 51 gas‐marts were found to have exterior advertisements for unhealthy beverages (SSB) in comparison with grocery (n = 16; 35%), dollar (n = 0), and pharmacy stores (n = 1; 8%). Gas‐marts were more likely to have at least one unhealthy beverage advertisement than other stores (n = 45; 88%). Interior SSB advertisements within gas‐marts commonly were positioned near the cash register (n = 31; 61%), below registers (n = 13; 25%); and on the floor or hanging from ceiling in comparison to other stores. (Statistically significant differences found for corner/small grocers and food‐gas marts in comparison to dollar and pharmacy stores). |

|

| Bogart, 2019 57 | Managers indicated stores were provided with BCI materials, without communication or engagement regarding their use from beverage companies. In‐store marketing for beverages was reportedly determined by corporate/headquarters. Management also perceived manufacturers used mainly national advertisements to increase consumer demand for SSB. These approaches were perceived to drive store sales. | |

| Ethan, 2013 59 | Among the first pages of store circulars, 2311 food and beverage products were identified. About 59% (n = 183) of featured beverages were SSB. | |

| Grigsby‐Toussaint, 2013 62 |

Soda had high frequency of marketing claims (83.33%; higher prevalence than claims for healthier products). Stores reportedly used by mothers were more likely to use soda marketing (83.3% vs. 62.2%). Soda products were always found to use marketing claims, although were less likely to feature child‐focused cartoons when compared with other healthier or less healthy items. Soda marketing claims: nutrition claim (e.g., low‐fat) (100%); taste (e.g., crisp, clean, and refreshing) (90%); fun (e.g., made for fun) (9.99%); suggested use (4.99%); and convenience (0%). Soda marketing claims by media giveaways: movie (4.99%); television (25%); cartoon (15%); toys (25%). Juice marketing claims (75% of all juices used claims): nutrition (75%); taste (60%); fun (19.99%); use (30%); and convenience (4.99%). Juice marketing claims by media giveaways: movie and television (0%); cartoon (46.66%); toys (6.66%). Differences by community characteristics: Marketing claims for soda were more frequent in Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) than non‐WIC authorized stores (100% vs. 62.23%). Juice marketing claims were more frequent in WIC stores (100%) than non‐WIC authorized stores (30.83%). (Statistically significant) Differences by store format: Marketing claims for soda were more prevalent among convenience (91.66%) in comparison with grocery stores (66.66%). (Statistically significant) |

|

| Isgor, 2016 63 |

Differences by community characteristics: Grocery store advertisements for regular soda were more prevalent in non‐Hispanic Black (30.5%) and Hispanic (24.4%) than in non‐Hispanic White communities (14.3%). (Statistically significant) Limited‐service store advertisements for regular soda were more prevalent in non‐Hispanic Black (48.1%) in comparison with non‐Hispanic White (42.2%) communities (no longer statistically significant when model controlled for income). Soda ads were more prevalent in supermarkets/grocers located in low‐income communities (25.1%) than those in higher income areas (middle income, 15.4%; high income, 10.4%) and within limited‐service stores in low‐income communities (47.7%) when compared with stores in middle‐ (41.1%) and high‐income (35.8%) areas. Further, a supermarket/grocer in a low‐income community was associated with higher odds of regular soda advertisements (OR = 2.14, CI = 1.32, 3.47), and a limited service store in a low‐income community was associated with 35% higher odds of regular soda advertisements in comparison with higher income areas. (Statistically significant) Differences by store format: Regular soda advertisements were found at 41.3% of limited service stores and 15.8% of supermarkets and grocery stores. (Statistically significant) |

|

| Kumar, 2014 66 |

Caregivers and adolescents reported exposure to food/beverage advertisements mostly on television (82.7% and 80.9%, respectively), followed by at the grocery store/supermarket (39.5% vs. 32.4%), on the internet/cell phone (26.4% vs. 24.5%), at the convenience store/gas station (21.3% vs. 14.8%), and at school (9.4% vs. 7.5%). Caregivers reported exposure to SSB ads at the grocery/supermarket and convenience store/gas station was significantly higher than exposure reported by adolescents. Differences by store format: SSB advertisements are perceived to be more common among grocery stores/supermarkets in relation to convenience stores. |

|

| Martin‐Biggers, 2013 69 | Differences by community characteristics: Significantly more space for SSB products in store circulars for sites located in the more than 30% obesity‐rate region than other regions (data not shown; specified SSB space more than two times higher than in other regions). Southeastern U.S. circulars tended to have more mean space dedicated to SSB products (data primarily included SSB; given two to six times as much advertising space in comparison with other regions). | |

| Moran, 2018 70 | Differences by community characteristics: Odds of SSB advertisements were 1.66 times higher during periods of SNAP benefit issuance in comparison with remainder of the month, and odds of SSB advertisements were 1.80 times higher during issuance periods in comparison to middle month dates. Settings within communities with high SNAP enrollment had 2.39 times higher odds of SSB advertisements in comparison with the remainder of the month. | |

| Penilla, 2017 71 | SSB advertisements were perceived by parents to be salient in community stores and outnumbered healthy product advertisements, in turn impacting children's consumption patterns. | |

| Robles, 2019 75 |

Number of SSB advertisements on store exterior and interior ranged from 0 to 5 (mean 2.7). This was higher than for other products in all but two stores (e.g., alcohol, water, fruits/vegetables, and/or junk food). |

|

| Ruff, 2016 76 | Number of outdoor or outward‐facing advertisements for SSB was on average 3.9 (although found not influential on consumer purchasing). This was higher than number of alcohol advertisements (average 2.4). | |

| Zenk, 2020 81 | Regular soda higher prevalence of promotions (interior and exterior) than other SSB products. 33.9% of advertisements for SSB on exterior, compared with 6.7% and 19.7% for artificial or unsweetened beverages; 63.7% of advertisements on interior for SSB vs. 43.5% and 46.8% for respective comparisons. Similar patterns in Sacramento, California. No significant differences in interior/exterior SSB advertisements at 6‐ and 12‐month post‐tax. Odds of interior advertisements for regular soda fell in Sacramento by 60% at 12‐month post‐tax. | |

|

Priming or prompting Environmental cues or product salience that prime consumer purchase of SSB products 23 , 38 |

Basch, 2016 56 | Differences by store format: In comparison with other sampled formats, department stores did not have corrals with SSB products near cash registers. |

| Bogart, 2019 57 | Managers described that beverage companies might initiate stocking agreements regarding floor displays. For example, sales representatives might suggest display placement, although store management had final authority and could choose not to use SSB displays without telling manufacturers. | |

| Cohen, 2015 82 | Differences by store format: Special floor displays for SSB most common among supercenters/wholesalers (11%), followed by grocery (7%), neighborhood (5%), and specialty (2%) stores. Not identified in chain convenience and dollar stores. | |

| Cohen, 2018 58 |

Differences by community characteristics: The potential exposure to SSB in grocery stores was higher in Mississippi and Alabama than Los Angeles, California stores (average number of SSB displays 92.1 vs. 88.9, respectively). Differences by store format: Among grocery stores, the potential for consumer exposure to SSB products was about 25 separate locations (less exposure in comparison with junk foods). Among convenience stores, potential SSB exposure occurred in about 5 locations. The majority of supermarket SSB displays (70–97%) had BCI‐branded products (Coca‐Cola, PepsiCo, Dr. Pepper/Snapple Group). About 59–100% of displays in convenience stores were from BCI brands. |

|

| Harris, 2020 80 | Products with added sugar had a significantly higher percentage of sales resulting from displays than products without added sugar. Child‐focused SSB products had double the sales attributed to displays than products without added sugar. | |

| Moran, 2018 70 | Differences by community characteristics: Found 0.40 more SSB product varieties on display during periods of SNAP benefit issuance in comparison to the remainder of month (95% CI = 0.18, 0.61). Retail settings had 1.88 times higher odds of having SSB displays during SNAP issuance and were 2.75 times higher during issuance in comparison with middle month dates. In areas with high SNAP enrollment, retailers had 4.35 times higher odds of SSB displays (95% CI = 1.93, 9.98) during issuance. | |

| Thornton, 2013 78 | Ranked number 1–8 regarding mean length of soft drink displays (on average 14 m; 95% CI = 12–16 m): Australia; the United States; the United Kingdom; Canada; Denmark; Netherlands; Sweden; and New Zealand. The proportion of U.S. soft drink aisle space was about 40% of all less healthy dietary products (e.g., chips, 40%; chocolate, 10%; confectionary, 10%), which was comparable with Australia and Canada regarding the countries with highest proportion of soft drink displays. | |

|

Proximity Location or placement of SSB products in high impulse purchasing areas 23 , 38 |

Adjoian, 2014 54 |

About half (45%) of stores had SSB products located at one or more promotional locations (e.g., end caps of aisles, special displays, and within a refrigerator at checkout). This was less common for healthier beverage choices. Differences by community characteristics: In areas with higher rather than lower consumer SSB consumption, SSB products were more commonly available in two or more locations within stores (78% vs. 65%, respectively; statistically significant). Sugary drinks placed in 2 or more locations in grocery stores were 81% in high‐consumption areas and 46% in low‐consumption areas. (Statistically significant) Differences by store format: Placement of sugary drinks in impulse purchasing areas more common among grocery stores than bodegas (78% of grocers and 36% of bodegas had sugary drinks at one or more promotional locations). End caps of aisles were common promotional locations for sugary drinks in grocery stores (68%), followed by special displays (56%), and checkout (15%). Placement of sugary drinks in one or more promotional locations was more common among pharmacies (78%) than bodegas (36%). End caps of aisles were common promotion locations among pharmacies (68%), followed by special displays (56%) and checkout (15%). |

| Barnes, 2014 55 |

About half (55 of 119 or 46%) of store checkout areas had soda within reach of the cash register. Interior advertisements for less healthy beverages were commonly near (51 of 119) or below the cash register (17 or 119). Differences by store format: Dollar stores and pharmacies more often had soda within reach of the cash register than corner/small grocery stores (89% vs. 77% vs. 35%, respectively). (Statistically significant) |

|

| Bogart, 2019 57 | Managers described decision making regarding SSB placement a responsibility of corporate or headquarters. SSB was described to sell better than healthier alternatives, and therefore, managers were not incentivized to change the placement of healthier alternatives (was suggested as a BCI strategy) and rather focused on increasing SSB sales. | |

| Cohen, 2015 82 | Differences by store format: SSB cash register placement most often used in grocery stores (43%), followed by supercenter/wholesaler (38%) and specialty stores (18%) and was not identified among other formats. End aisle placement of SSB most common in convenience stores (77%), followed by neighborhood stores (42%), grocers (24%) supercenter/wholesaler (10%), and specialty (8%) stores. Not identified in the dollar store. | |

| Cohen, 2018 58 |

End‐aisle placement for SSB was common among sampled stores. Placement of SSB products was more frequent than placement of healthier alternatives or water products in assessed locations. Differences by community characteristics: In grocery stores located in the South, SSB displays were less common at end‐of‐aisle and along perimeter walls (50% vs. 72%) than in Los Angeles, California (24% vs. 43%). Cash register displays were more frequent in the South than in Los Angeles (67% vs. 62%). Results also mirrored availability of SSB brands that participated in the BCI. (Descriptive results) Differences by store format: SSBs were most placed at cash registers in grocery stores and along the perimeter of convenience stores. SSB located in store aisles was more common in convenience than grocery stores. Convenience stores were also more likely than grocers to use floor displays for SSB. Mini‐cans in grocery stores were available at end‐of‐aisle (3%), in aisles (4%), and by cash registers (2%). |

3.2. Evidence synthesis

3.2.1. Place

Place strategies could include changes to store atmosphere qualities (e.g., lighting) or structural additions (e.g., installing shelves or coolers) to support product stocking and encourage SSB purchases. 23 , 37 One study (3%) assessed store management perceptions of infrastructure installation to support SSB product stocking (Table 3), which was reportedly directed by manufacturers with discretion left to management regarding changes. 57

3.2.2. Profile

Thirteen studies (45%) provided information about SSB product availability or ingredient composition. 23 , 37 SSB products were generally highly available, 54 , 58 , 61 , 62 , 64 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 77 , 79 and researchers in one study observed no changes in SSB availability between years 2016 and 2017 (no intervention). 79 At times, SSB products were found less prevalent than other “junk” products in two smaller store investigations (Table 3). 61 , 77 Parents also believed SSB products were widely available in food stores. 71 Store managers described SSB product reformulation as required to reduce consumers' added sugar consumption and also indicated manufacturers contracted shelf space for SSB. 57

Limited‐service stores were the only sites observed to carry sugar‐sweetened water products in comparison with grocers in one study. 77 SSB stocking varied among chain store brands of the same format 73 , 74 and by store location. For example, stores near the Mexican border carried imported SSB brands not found in other regions. 58 Community stores with higher income consumers stocked energy shots more frequently than stores serving consumers with low income. 74 Additionally, one study found increased SSB product availability during monthly SNAP benefit issuance periods, 70 and another found a large proportion of SSB products to be child‐focused among sampled supermarkets. 80

3.2.3. Portion

Two studies (7%) reported results related to SSB container or portion size (Table 3). 23 , 37 In one study that measured the availability of SSB mini cans, smaller containers were available in only a few sampled grocers and not at all in convenience stores. 58 Qualitative evidence from a separate study among store management identified smaller SSB portions as a perceived opportunity to improve consumer dietary quality while maintaining sales (Table 3). 57

3.2.4. Pricing

Pricing strategies to sell SSB products include price promotions or store/regional product pricing strategies. 23 , 37 Information about SSB pricing was available in 13 studies (45%), and one study focused on SSB product profitability (Table 3). At one small store in New Orleans, Louisiana, SSB products accounted for about 13% of the store's total profit. 61 This percentage represented more than all other products except beer and tobacco. Other findings noted the affordability of SSB products in general and in comparison with healthier product alternatives. 58 , 60 , 64 , 65 , 67 SSB products in the southeastern United States 58 , 67 tended to be priced lower than SSB products for sale in other U.S. regions. There were also somewhat conflicting variations among community stores by consumer base. Specifically, SSB purchase prices were higher in areas with high SSB consumption 64 and lower in stores with majority racial/ethnic minority 65 , 67 and low‐income consumers. 65 SSB pricing variations by population were not found in two other studies. 67 , 72

Discount pricing strategies for SSB were also frequently used, outnumbering price reductions for healthier products among sampled stores in five studies. 54 , 59 , 68 , 72 , 80 Such promotions encouraged the purchase of SSB in high quantity (Table 3). 58 , 59 , 72 Two studies found price promotions more common among supermarkets than smaller stores. 72 , 82 One study suggested price promotions may be used more routinely to sell child‐focused SSB products. 80 Further, fewer SSB price promotions were applied after SSB taxation. 81 While store managers identified coupons as a popular promotion strategy, they deemed coupons less effective than in‐store discounts (Table 3). 57 Managers believed healthier alternatives required competitive pricing relative to SSB to encourage consumption. 57

3.2.5. Promotion

Use of advertisements or promotional strategies (aside from price promotions) 23 , 37 for SSB were found in 13 studies (45%) (Table 3). Such promotions were identified in the majority of sampled stores among two studies 54 , 55 and another found advertisements especially frequent for regular soda. 81 Interior and exterior signages 55 , 75 , 76 were used for SSB products in addition to store circulars 59 and SSB product claims (e.g., “Crisp, clean, and refreshing”). 62 There was also evidence of disproportionate use of SSB promotions among stores located in the southeastern United States 69 and among those with a high proportion of racial/ethnic minority and/or low‐income consumers. 62 , 63 , 70 SSB taxation was not found to change the prevalence of interior or exterior advertisements for SSB. 81

Gas‐marts or limited service stores had more advertisements for SSB than other sampled stores in two studies. 55 , 63 However, parents perceived supermarkets as a primary exposure site for SSB marketing compared with smaller convenience stores. 66 In another study, parents identified grocery and convenience stores as a primary place where children are exposed to SSB marketing, second only to television advertisements. 71 Furthermore, store management described SSB manufacturers most likely to prioritize national marketing campaigns over using store promotions for SSB. 57

3.2.6. Priming or prompting

Seven articles (24%) identified information about environmental cues (i.e., SSB product prominence) within stores (Table 3). 23 , 37 U.S. supermarkets had a higher proportion of shelf space for SSB products (ranked second behind Australia) than supermarkets in other high‐income countries (e.g., United Kingdom, Canada, and Denmark). 78 One study found displays for SSB products more common in southeastern U.S. stores, 58 and another noted less priming for SSB purchases in department stores (Table 3). 56 It was also reported SSB displays within supermarkets exceeded those in convenience stores, 58 and SSB display frequency in supermarkets was behind only supercenters/wholesalers. 82 Results of one study suggested displays may be used most frequently to sell SSB, especially child‐focused SSB products. 80 A higher frequency of SSB displays (or higher product prominence) was also identified during SNAP benefit issuance periods. 70 Displays were described by store management as initiated through manufacturer agreements but ultimately left the decision to managers. 57

3.2.7. Proximity

Five studies (17%) described the placement or location of SSB products in stores. 23 , 37 These studies often documented SSB products in multiple locations (Table 3). Grocery stores had SSB products placed in impulse purchasing areas (such as checkout areas) more often than smaller stores. 54 , 58 One study found SSB placement near cash registers more common in dollar and pharmacy stores than small grocers 55 and another found end‐aisle placement common in convenience stores. 82 There were some variations by geography. Checkout availability of SSB was higher in communities with residents reporting high SSB consumption. 54 Stores in the southeastern United States were found to have SSB products available on aisle end caps and around the perimeter more often than stores located in other measured regions. 58 Management described little incentive to change the placement of healthier beverage alternatives, as SSB products were perceived to sell better than no/low kcal options. 57 Additionally, corporate store stakeholders (rather than manufacturers) were described to plan SSB placements in stores. 57

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Main findings and importance

The purpose of our rapid review was to characterize MMCA strategies used to sell SSB products in U.S. food stores to inform public health research, practice, and policy approaches. Although not a main focus of many included studies, we found evidence of MMCA strategy variations based on store type and among stores with a high proportion of at‐risk consumers. Whether these differences can be attributed to store size and business model or systematic regional (e.g., southeastern United States) or community‐specific (e.g., low‐income) strategies for sales requires both additional investigation and the use of natural experiment or causal research designs. Likewise, as the majority of included studies relied on observational data, it is unknown to what extent diverse stakeholders (i.e., manufacturers, distributors, sales representatives, store managers, and employees) impact SSB stocking and marketing strategies in food stores. Additional research could inform opportunities for tailored policy and implementation strategies by store, region, stakeholder, and/or consumer demographics. Main findings are reported below with respect to MMCA strategies used for SSB sales.

4.2. Profile, pricing, and promotion strategies to sell SSB products

Most of the studies we reviewed provided insight into profile, pricing, and promotion strategies used for SSB sales, which are widely available products in U.S. food stores given their long shelf‐life, consumer demand, and profitability. 25 , 37 , 61 However, research showing the potential for SSB product availability, priming, and promotions to further increase during periods of SNAP issuance is concerning. 70 This was also identified with regard to lower targeted SSB prices among at‐risk consumers 65 , 67 or in stores from regions with high consumer poverty and obesity (e.g., southeastern United States), 58 , 65 which are also populations observed to have higher rates of habitual SSB consumption. 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 These findings were somewhat contradictory regarding results from one reviewed study that identified higher SSB purchase prices in community stores with consumers reporting frequent SSB consumption. 64 Additionally, findings regarding the use of SSB advertisements mirror results about the use of pricing strategies, which seem targeted to at‐risk consumer groups. 63 , 69 , 70

These findings align with reports of targeted strategies used per population, 16 , 31 , 32 and results of this research suggest coordinated use of several MMCA strategies to push SSB sales among at‐risk U.S. consumer groups who experience health disparities. 7 , 8 , 9 More research is required, as few included studies were designed to capture disparities of in‐store MCCA strategy use by community factors such as income, location, race/ethnicity, obesity, or consumer consumption. These findings provide the most compelling argument for policy changes to influence stocking and marketing practices used to sell SSB products in U.S. food stores. Manufacturer/retailer targeting of at‐risk consumer groups in food store spaces is a public health concern given the association of frequent SSB intake with obesity and NCD. 5 , 13 , 14 , 15 Broadly, outcomes related to poor health are predicted to cost $94.9 trillion dollars (years 2015–2050) 83 and negatively impacts the broader U.S. population (e.g., beyond only those that consume SSB).

Corporate determinants of health 84 regarding variations in SSB stocking and marketing practices requires protective policy responses to mitigate health disparities, in conjunction with or beyond voluntary industry strategies. This review was designed around launch dates for two self‐regulatory campaigns, Drink Up and the BCI. No reviewed articles included information about SSB stocking and marketing practices used by Drink Up campaign food store partners. There is some evidence, however, that consumers exposed to the campaign purchased more bottled water. 85 One article described the prominence of BCI‐participating SSB brands throughout stores that seem contradictory to “balance intake” messages. 58 Further, managers described BCI as not well aligned with business models because no incentives were provided to make changes. 57 There is a lack of research about how and to what extent industry commitments influence the consumer food environment, 45 and more research to define the role of self‐regulatory and policy strategies to decrease consumer SSB consumption are required. Better evidence of how self‐regulation initiatives influence stocking and marketing practices could prompt industry stakeholders to better align their practices with stated commitments (e.g., BCI recognizing product prominence as an indicator of marketing and adjusting appropriately to favor consumer loyalty). 48 , 49

4.3. Place, portion, priming or prompting, and proximity strategies to sell SSB products

We found less evidence of the use of MMCA strategies place, portion, priming or prompting, and proximity to sell SSB products among reviewed articles. This is likely due to limitations of current food environment measures or tools to appropriately capture these properties. For example, no established tools include indicators for store atmosphere properties, such as music, which could be used to influence the purchase of unhealthy products more broadly (e.g., including SSB). 38 Future research could incorporate measures to assess store owners' and managers' perspectives 37 , 86 , 87 about their use of place strategies to sell SSB products to quantify these practices for further investigation.

Also, tools may not be designed to measure all available SSB product sizes available (e.g., mini‐cans, cases, 16/20 fluid‐ounce bottles, or 2‐L options), which limits the capacity to understand variations among product sizes regarding stocking and marketing practices. Beverage manufacturers have used mini‐cans to broaden their consumer base to include health‐conscious shoppers, 88 , 89 although it is unknown how MMCA strategies used to sell smaller portion sizes influences consumer purchase or SSB intake behaviors. Likewise, priming or prompting is a less‐clear‐cut indicator for measurement, although using exposure points (number of locations or displays of SSB) 58 or checklists to document the presence of shelf labels may be useful moving forward. Often, SSB products were located in impulse purchasing areas (e.g., end caps and checkouts), and current tools used in reviewed studies and elsewhere (e.g., BTG FSOF and GroPromo 90 ) require broader application to discern SSB placement differences by store type and community characteristics.

Our review results also suggest supermarkets may prime consumers more than smaller stores regarding the purchase of SSB products, although this may be related to store size (e.g., more space for numerous SSB displays and marketing strategies). This may be one reason supermarkets have been associated with the prevalence of obesity, 91 despite their historical use as an indicator of favorable community food access. Research has shown optimal food access more complex than supermarket distance, 92 , 93 , 94 and application of environmental tools and/or scanner purchasing data 95 to understand the influence of SSB MMCA strategies on consumers' purchase of healthy and less healthy beverages is warranted among varied store formats and communities. Such information could further inform policy strategies that change consumers' rather than community nutrition environments.

5. LIMITATIONS

Our review provides directions for future public health research, practice, and policy approaches to reduce the prominence of SSB products in U.S. food stores, although conclusions should be interpreted with respect to the following limitations. We found a low number of supporting articles with information about SSB stocking and marketing practices and the observational nature of the supporting research we did identify is a limitation. More robust analyses, such as with scanner purchasing data, 90 are required to understand the impact or effectiveness of MMCA strategies used to sell SSB products on U.S. consumers' purchase and consumption habits by store type and consumer demographics. However, retailers' use of these strategies suggests efficacy, given the importance of profit. 37 The measurement tools used in most studies also lacked information about validity testing, although most were found reliable and were accompanied with training.

The search approach we used could have been inadequate to identify all relevant peer‐reviewed research, although we did check references of included articles to identify missed sources, which resulted in identifying additional articles. Additionally, narrowing the review focus to assess stocking and marketing practices of only SSB products could be seen as a limitation given the DGA focus on dietary patterns rather than single, unfavorable food and beverage products or nutrients. 1 However, current public health responses have focused on SSB products rather than nutrients (a sugar tax) and may indicate strategies with a greater likelihood for success in the current political climate. 96 SSB consumption contributes to the majority of Americans' discretionary kcal and added sugar intake 97 and has been associated with poor dietary quality overall, 97 so reducing consumers' SSB intake may improve population dietary patterns. 97

6. FUTURE DIRECTIONS

In order to meet the goals outlined in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development 40 , 41 , 42 regarding actions to improve public health, health equity, and environmental sustainability, future research should investigate food environment approaches to reduce SSB consumption.

6.1. Public health

Ensuring more U.S. locations adopt SSB taxation strategies could reduce the use of SSB price promotions 81 (alongside resultant purchase price increases) without requiring additional policy strategies. 98 Overall, comprehensive strategies are likely needed, as well as understanding the impact of coordinated public health policy and self‐regulatory strategies with local‐level practice approaches (e.g., consumer education; policy, systems, and environmental change strategies). Implementation outcomes, such as the acceptability, appropriateness, and feasibility of practice and policy approaches to reduce SSB product prominence in U.S. food stores are also critical to inform practical approaches likely to initiate retail changes long term. 20 , 99 , 100 Finally, advocacy groups have proposed retail licensing approaches as a potential opportunity to reduce the prominence of SSB products in the food environment. 16 Such approaches have not yet been implemented in the U.S. and require stakeholder‐engaged investigations to inform licensing capacity to protect at‐risk consumers.

6.2. Health equity

Policy strategies should be investigated through SNAP and WIC‐authorization avenues, as SNAP and WIC participants have reported more frequent SSB consumption than nonparticipant populations. 10 , 11 Evidence suggests retailers can successfully adapt inventory to support changes to food package items, as with the WIC 2009 policy change, 100 and similar changes to SNAP could also impact stocking and marketing practices used in SNAP‐authorized stores. 34 However, any retail changes should coordinate with changes to allowable and non‐allowable SNAP purchasing, as there has been tremendous pushback to supply changes that do not address consumer demand. 99 Further, changes to SNAP benefit distribution schedules (e.g., distributed throughout the month, rather than specific timepoints) may deter targeted stocking and marketing strategies to sell SSB during times when SNAP shoppers are most likely to be in‐store. 70