Summary

The lack of an active neighbourhood living environment can impact community health to a great extent. One such impact manifests in walkability, a measure of urban design in connecting places and facilitating physical activity. Although a low level of walkability is generally considered to be a risk factor for childhood obesity, this association has not been established in obesity research. To further examine this association, we conducted a literature search on PubMed, Web of Science and Scopus for articles published until 31 December 2018. The included literature examined the association between measures of walkability (e.g., walkability score and walkability index) and weight‐related behaviours and/or outcomes among children aged under 18 years. A total of 13 studies conducted in seven countries were identified, including 12 cross‐sectional studies and one longitudinal study. The sample size ranged from 98 to 37 460, with a mean of 4971 ± 10 618, and the age of samples ranged from 2 to 18. Eight studies reported that a higher level of walkability was associated with active lifestyles and healthy weight status, which was not supported by five studies. In addition to reviewing the state‐of‐the‐art of applications of walkability indices in childhood obesity studies, this study also provides guidance on when and how to use walkability indices in future obesity‐related research.

Keywords: built environment, child, obesity, walkability index

1. INTRODUCTION

Obesity is a leading cause of morbidity and premature mortality worldwide. One major challenge of the global rise in obesity is its adverse effects on children. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the obesity rate among children and adolescents was less than 1% in 1975, but after nearly 40 years of economic development and nutritional improvement, the global obesity rate rose to 8% among boys and 6% among girls in 2016, leading to over 340 million children and adolescents with obesity. 1 Among developed countries, the United States has been the largest victim of the obesity epidemic, where nearly one‐third of all children and adolescents have overweight or obesity. 2 Additionally, childhood obesity has become an emerging issue in developing and underdeveloped countries and has become extremely critical in Asia. 3 For example, nearly half of Asian children under the age of 5 were diagnosed with obesity or overweight, 4 which implies a soaring obesity trend among the Asian population.

Childhood obesity is a chronic health outcome that can be introduced by a complex array of factors, including environment, genetics and ecological effects. 4 , 5 , 6 The etiology leading to childhood obesity is extremely complex: for example, the overconsumption of calories among children can be an intrinsic outcome of unhealthy diets, which could be driven by family and social influences, such as feeding styles 7 and the popularity of sugar‐sweetened beverages. 8 Another widely discussed contributor to childhood obesity is the built environment. Research on public health shows strong evidence that the built environment can shape the quality of individual life and the community's overall health by promoting physical activity (PA), providing proper nutrition and reducing toxic exposure. 9 Specifically, unfavourable built environments (e.g., the prevalence of fast‐food outlets and the lack of PA sites) play an obesogenic role by encouraging unbalanced diets and a sedentary lifestyle. 10 However, the connection between the built environment and childhood obesity remains convoluted as the change of weight status is inseparable from the dynamics of physical growth (e.g., height and weight), the early onset of genetic syndromes and the unshaped eating behaviours in child development. 4

Although it is extremely difficult to disentangle the myriad obesogenic factors in the built environment that implicitly contribute to childhood obesity, one underexplored metric is walkability. Although the term ‘walkable’ has been used since the 18th century, its extension to ‘walkability’ was relatively recent and also lacks clarity. 11 There are three clusters of definitions of walkability, focusing on the means or conditions to achieve a walkable environment, the outcomes or performance of having a walkable environment and the proxy for measuring the quality of a walkable environment. 11 The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) adopts the third definition, considering walkability as ‘the idea of quantifying the safety and desirability of the walking routes’. 12 This conceptualization of walkability, stemming from the scientific evidence that walking can boost metabolism, lower blood sugar and improve mental health, 13 has become a quantifiable variable to study health‐promoting effects of the built environment.

However, there are two existing challenges in elucidating the effects of walkable environments on childhood obesity. The first challenge is incongruities in methodology, as the metrics used to quantify walkability vary across studies. 14 , 15 One widely used walkability metric refers to the Walkability Audit Tool developed by the CDC, which is a seven‐step audit tool to evaluate outdoor walking surfaces. 12 The method evaluates an individual work environment with a relatively subjective, labour‐intensive nature; therefore, it cannot be effectively applied to large‐scale assessments. The advancement of geospatial technologies, particularly Geographical Information Systems (GIS), has facilitated the development of walkability metrics for large‐scale observations. 16 , 17 These GIS methods can be roughly split between two categories. One group of studies employs area‐based metrics, such as the density of restaurants, 18 , 19 food retailers 20 , 21 and built environmental features 6 within statistical units (e.g., census tracts and postal zones). The other group of studies employs network‐based metrics, considering walkability as a measure of accessibility to nearby amenities (e.g., stores, public transits and greenspaces) from residential locations or workplaces. 22 , 23 One popular proximity measure, called the Walk Score, 24 evaluates the walkability of more than 10 000 neighbourhoods in over 2800 cities in the United States, which further supports public inquiry about the livability of neighbourhoods. To date, there has been a lack of consensus in the selection of metrics for walkability assessment.

The second challenge is the lack of consistency in defining weight‐related behaviours and outcomes when evaluating the effects of walkability on childhood obesity. While living in a walkable community could promote engagement in PA and thus reduce the risks of obesity, this association cannot be elucidated without refining the choice of mediator variables. Variables used to characterize weight‐related behaviours and outcomes vary across childhood obesity studies. For example, for weight‐related behaviours, studies have examined PA, 25 moderate‐vigorous physical activity (MVPA) 26 and active commuting to school (ACS); 27 for weight‐related outcomes, studies have examined the obesity rate, 28 weight status 29 and body mass index (BMI) values. 30 In addition to these different variable choices, variations in study areas and age groups among children add another layer of uncertainty over the correlation analysis.

Because of these methodological uncertainties, associations between walkability and childhood obesity are rather inconsistent. For example, although the walkability score (e.g., intersection density and land use mix) was calculated and identified as positively correlated with PA among children in Spain, 25 , 27 Australia, 26 the United States 31 , 32 and New Zealand, 29 this correlation was not found in two other studies conducted in Scotland 30 and Germany. 33 Furthermore, the correlation between walkability scores and obesity is far from conclusive: Although the negative correlation between walkability scores and the childhood obesity index (e.g., BMI) was found to be significant in the United States 34 , 35 and Malaysia, 36 this correlation was not significant in Germany. 37 In addition, one study showed that the walkability score was positively associated with the risk of overweight or obesity in England. 38

Existing reviews on the relationships between walkability and weight‐related behaviours and outcomes are all focused on adults. 39 , 40 There have been no reviews of such relationships in children. To this end, we conducted a systematic review of existing literature focused on the walkability‐weight status behaviour/outcome relationship among children and adolescents. We first compiled an inclusive list of measures of walkability employed for studying childhood obesity. Then, we reviewed and categorized these studies with respect to the measure of walkability, weight‐related behaviour and weight‐related outcome. This review has important public health implications—by identifying the attributes and major findings of case studies, future research on childhood obesity can choose appropriate models and significant metrics to define walkability as one important built environmental variable. The summarized evidence about the effects of walkability can guide research on childhood obesity and solidify its scientific underpinnings.

2. METHODS

A systematic review and meta‐analysis were conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses. 41

2.1. Study selection criteria

Studies meeting all of the following criteria were included in the review: (a) study designs: longitudinal and cross‐sectional studies; (b) study subjects: children and adolescents aged under 18 years (studies with subjects aged under 19 years are partially included with explanations); (c) study outcomes: weight‐related behaviours (e.g., PA, sedentary behaviour and eating behaviour) and/or outcomes (e.g., weight status, BMI, waist circumference, waist‐to‐hip ratio and body fat); (d) article types: peer‐reviewed original research articles; (e) time of publication: from the inception of the electronic bibliographic database to 31 December 2018; and (f) language: articles written in English.

2.2. Search strategy

A keyword search was performed in three electronic bibliographic databases: PubMed, Web of Science and Scopus. The search strategy included all possible combinations of keywords from the three groups related to measures of walkability, children and weight‐related behaviours or outcomes. The specific search strategy is provided in Appendix S1.

The titles and abstracts of the articles identified through the keyword search were screened against the study selection criteria. Potentially relevant articles were retrieved for an evaluation of the full text. Two reviewers independently conducted the title and abstract screening and identified potentially relevant articles for the full‐text review. Discrepancies were compiled by A and screened by a third reviewer. Three reviewers jointly determined the list of articles for the full‐text review through a discussion. Then, two reviewers independently reviewed the full texts of all the articles in the list and determined the final pool of articles included in the review.

2.3. Data extraction and preparation

A standardized data extraction form was used to collect methodological and outcome variables from each selected study, including author names, year of publication, country, sampling strategy, sample size, age at baseline, follow‐up years, number of repeated measures, sample characteristics, statistical model, attrition rate, measures of walkability, measures of weight‐related behaviours, measures of body‐weight status and key findings on the association between walkability and weight‐related behaviours and/or outcomes. Two reviewers independently extracted data from each study included in the review, and discrepancies were resolved by the third reviewer.

2.4. Study quality assessment

We used the National Institutes of Health's Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross‐Sectional Studies 42 to assess the quality of each included study. This assessment tool rates each study based on a 14‐question criterion (Appendix S2). For each question, a score of one was assigned if ‘yes’ was the response, whereas a score of zero was assigned otherwise (i.e., an answer of ‘no’, ‘not applicable’, ‘not reported’ or ‘cannot determine’). A study‐specific global score ranging from 0 to 14 was calculated by summing up scores across all questions. The quality assessment helped measure the strength of scientific evidence but was not used to determine the inclusion of studies.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Study selection

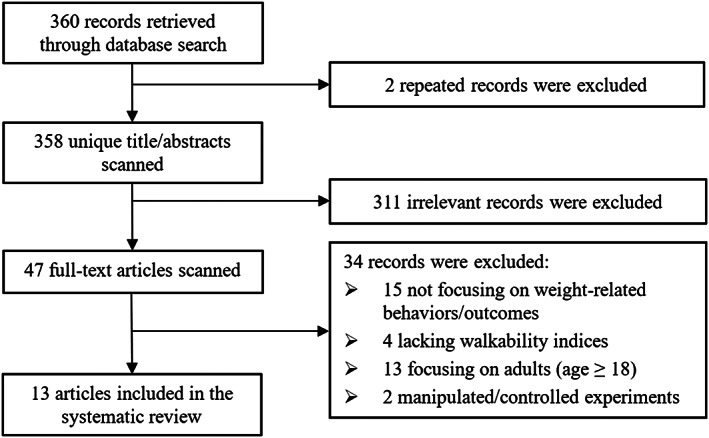

Figure 1 shows the flowchart of the study selection procedure. We identified a total of 368 articles through the keyword search. After undergoing title and abstract screening, 311 articles were excluded. The full texts of the remaining 55 articles were reviewed against the study selection criteria, after which 42 articles were further excluded. The remaining 13 studies that examined the relationship between walkability and children's weight‐related behaviours and/or outcomes were included in this review.

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart of the study selection procedure

3.2. Study characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the basic characteristics of the 13 included studies, including one longitudinal study and 12 cross‐sectional studies. The articles included in this review were from seven different countries, including the United States (n = 6), Spain (n = 2) and one each from the United Kingdom, Canada, New Zealand, Germany and Malaysia. The sample size ranged from 98 to 37 460, with a mean of 4971 ± 10 618, and the age of the samples ranged from 2 to 18. The statistical models used for analysis included linear regressions (n = 5), correlation analyses (n = 4), logistic regressions (n = 2), separate regressions (n = 2), mixed models (n = 2) and generalized estimates equations (n = 1).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the studies included in the review

| First author (year) | Study area (scale) a | Study design b | Sample size | Age at baseline (years, range and/or mean ± SD)c | Sample characteristics | Statistical models |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cheah (2012) 36 | Kuching, Sarawak (C) | C | 316 | 14–16 | School children | Univariate correlation analysis |

| Molina‐García (2017) 27 | Valencia, Spain (C) | C | 325 | 14–18 (16.4 ± 0.8) in 2013–2015 | School children | Separate mixed effects regression models; generalized linear mixed models |

| Shahid (2015) 46 | Calgary, Canada (C) | L | 37 460 | 4.5–6 in 2005–2008 | School children (followed up from 2005 to 2008 with PHANTIM database) | Correlation; cross‐correlation analysis |

| Slater (2013) 34 | US (N) | C | 11 041 | Public school students at grades 8, 10 and 12 in 2010 | School children | Multivariable logistic regression |

| Molina‐García (2017) 25 | Spain (N) | C | 310 | 10–12 in 2015 | School children | Mixed model regression |

| Hinckson (2017) 29 | Auckland and Wellington, NZ (C2) | C | 524 | 12–18 (15.78 ± 1.62) in 2013 and 2014 | School children | Generalized additive mixed models |

| Noonan (2015) 43 | Liverpool, UK (C) | C | 194 | 9 and 10 in 2014 | School children | Analysis of covariance; linear regression |

| Rosenberg (2009) 44 | Boston, Cincinnati and San Diego, US (C3) | C | 458 | 5–18 in 2005 | School children | Single measure intraclass correlation coefficients; one‐way analysis of covariance |

| Lovasi (2011) 32 | New York City, US (C) | C | 428 | 2–5 in 2003–2005 | Preschool children | Generalized estimates equations |

| Graziose (2016) 47 | New York City, US (C) | C | 952 | 10.6 in 2012 and 2013 | School children | Multilevel linear models |

| Buck (2014) 33 | Delmenhorst, German (C) | C | 400 | 2–9 in 2007 and 2008 | Preschool and school children |

Gamma log regression Model |

| Kligerman (2006) 31 | San Diego County, US (CT) | C | 98 | 14.6–17.6 in 2005 | School children | Multiple linear regression; Pearson correlation; separate regression |

| Wasserman (2014) 45 | Kansas, US (S) | C | 12 118 | 4–12 (8.22 ± 1.77) in 2008 and 2009 | School children | Hierarchical linear modelling |

Study area: (N)—National, (CT)—County or equivalent unit, (CTn)—n counties or equivalent units, (C)—City; (Cn)—n cities.

Sample age: Age in baseline year for cohort studies or mean age in survey year for cross‐sectional studies.

3.3. Measures of walkability

The measures of walkability and weight‐related behaviours and/or outcomes in the included studies were summarized (Table 2). The level of walkability was calculated by using different statistical units, such as census blocks (n = 2), buffer zones around homes or workplaces (n = 5) and the school enrolment zone (n = 1). Four studies measured walkability by using the scoring criterion of the Neighborhood Environment Walkability Scale for Youth (NEWS‐Y). 29 , 36 , 43 , 44 Specifically, the NEWS‐Y is an aggregate measure with nine scoring components: diversity of the land use mix, neighbourhood recreation facilities, residential density, accessibility measures of the land use mix, street connectivity, walking/cycling facilities, neighbourhood aesthetics, pedestrian and road traffic safety and crime safety. 43 Seven studies evaluated walkability by some of these nine components. One study measured walkability by calculating the density of convenience stores, fast‐food restaurants, grocery stores, fitness facilities and parks within a 0.5‐mile radius of the school. 45 Another study evaluated the walkability of home addresses based on the distance‐weighted proximity to categorized amenities, including education, recreational, food, retail and entertainment. 46

TABLE 2.

Measures of walkability and weight‐related behaviors and/or outcomes in the included studies

| First Author (year) | Walkability indices | Other environmental factors adjusted for in the model | Measures of weight‐related behavior | Detailed measures of weight‐related outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cheah (2012) 36 | The sum of z‐scores of each of the nine perceived categories (residential density, land‐use mix diversity, land‐use mix access, street connectivity, infrastructure for walking, aesthetics, traffic safety, safety from crime, and neighborhood satisfaction) in the neighborhood on the basis of a modified questionnaire adapted from the NEWS‐Y | NA |

• PA (time spent outdoors per day collected through self‐reporting) • Physical fitness (using a maximal multistage 0.02‐km shuttle run test to determine the maximal aerobic power) |

• BMI based on measured height and weight • Overweight (between 85th percentile and 95th percentile) • Obesity (≥ 95th percentile) |

| Molina‐García (2017) 27 | (z‐score of intersection density) + (z‐score of net residential density) + (z‐score of land use mix) within a census block |

• Days per week living at the primary address • Distance to school (km) • Driver license (yes or no) • Number of children < 18 years old living in the household • Number of motor vehicles per licensed driver • Years at current address • Exercise equipment in or around home |

• MVPA (measured by ActiGraph accelerometers; ≥ 1148 counts per 30‐second epoch, MVPA; and ≤ 50 counts per 30‐second epoch, ST) • Physically active ≥ 60 min/day outside of school (days per week) • ACS (trips per week) • Number of sports teams or PA classes outside of school |

• BMI based on measured height and weight • Overweight (between 85th percentile and 95th percentile) • Obesity (≥ 95th percentile) • %BF analyzed by bioelectrical impedance, %BF dichotomized as low/high (using the cut points of 25% for boys and 30% for girls) |

| Shahid (2015) 46 | Walkscore™ index: the sum of the weighted straight‐line distances to the closest facilities in each of the five categories (education, recreational, food, retail, and entertainment), with a normalized value ranging from 0 to 100 (0 is the least walkable, and 100 is the most walkable) | NA | NA |

• BMI z‐score based on self‐reported height and weight • Overweight (between 85th percentile and 95th percentile) • Obesity (≥ 95th percentile) |

| Slater (2013) 34 | The proportion of streets in a community that have walkable features (mixed land use, sidewalks, sidewalk buffers, sidewalk/street lighting, other side‐walk elements, traffic lights, pedestrian signal at the traffic light, marked crosswalks, pedestrian crossings and other signage, and public transit) | NA | NA |

• BMI based on self‐reported height and weight (age‐ and gender‐specific) • Overweight (between 85th percentile and 95th percentile) • Obesity (≥ 95th percentile) |

| Molina‐García (2017) 25 | (z‐score of net residential density) + (z‐score of land use mix) + (z‐score of road intersection density) within a census block | NA | • ACS (the number of trips per week to and from school by walking, cycling or skateboarding) |

• BMI based on measured height and weight (calculated by the 2000 CDC growth charts) • BMI percentile adjusted for age and sex |

| Hinckson (2017) 29 |

• The sum of z‐scores of gross residential density and number of parks within a 2‐km home buffer • The sum of z‐scores of perceived land use mix‐diversity, street connectivity, and aesthetics |

NA |

• PA (the GT3X+ Actigraph accelerometer was used to estimate the minutes of PA and ST over a 7‐day period) • Average minutes per day of MVPA and ST |

NA |

| Noonan (2015) 43 | The sum of z‐scores of each of the nine perceived categories (land use mix‐diversity, neighborhood recreation facilities, residential density, land‐use mix‐access, street connectivity, walking/cycling facilities, neighborhood aesthetics, pedestrian and road traffic safety, and crime safety) perceived in the neighborhood on the basis of NEWS‐Y | NA |

• PA (assessed using the PA questionnaire) |

• BMI based on measured height and weight • Waist circumference |

| Rosenberg (2009) 44 | The sum of z‐scores of each of the nine perceived categories in the neighborhood, including eight standard categories (land use mix‐diversity, pedestrian and automobile traffic safety, crime safety, neighborhood aesthetics, walking/cycling facilities, street connectivity, land use mix‐access, and residential density) on the basis of NEWS‐Y and one additional category (recreation facilities within a 10‐min walk from home) | • Income |

• PA (walking to/from school at least once per week, Y/N) • PA (doing physical activity in the street at least once per week, Y/N) • PA (walking to a park at least once per week, Y/N) • PA (walking to shops at least once per week, Y/N) • PA (doing physical activity in a park at least once per week, Y/N) • MVPA (participant meeting the criterion of 60 min of activity for 5 days per week, Y/N) |

NA |

| Lovasi (2011) 32 | Five different measures within a 0.5‐km neighborhood buffer: population density of the census block group, land use mix constructed using the parcel‐level data (0: single land use; 1: mix uses), subway stop density, bus stop density, and intersection density |

• Number of rooms in the household • Neighborhood characteristics • Season |

• PA (assessed through placing Acti‐Watch accelerometers and using a 6‐day PA recall) |

• BMI z‐score based on measured height and weight • Sum of skinfolds |

| Graziose (2016) 47 | The sum of z‐scores of four environmental measures in school neighborhood (land use mix, intersection density, residential population density, and retail floor area density) | NA | • PA (using FHC‐Q to access) | • BMI‐for‐age percentile and BMI z‐score based on measured height and weight |

| Buck (2015) 33 |

• The sum of z‐scores of three measures (residential density, land use mix, and intersection density) within a 1‐km home street‐network buffer • The sum of z‐scores of four measures (residential density, land use mix, intersection density, and public transit density) within a 1‐km home street‐network buffer |

• Hours of valid weartime • Season of the accelerometer measurement |

• MVPA (using accelerometer measurements) |

• Age‐ and sex‐specific BMI z‐score • Weight status |

| Kligerman (2007) 31 | The sum of z‐scores of each of the four categories (land use mix, retail floor area ratio or retail density, intersection density, and residential density) within a 0.8‐km home street‐network buffer |

NA |

• MVPA (average daily minutes collected by the Actigraph uniaxial accelerometer for a 7‐day period) |

• Height was measured with a portable stadiometer and weight on a calibrated digital scale • BMI based on measured height and weight |

| Wasserman (2014) 45 | The density of convenience stores, fast‐food restaurants, grocery stores, and fitness facilities within a 0.8‐km school buffer and of parks within a 1.6‐km school buffer, by referring to Walkscore™ website | • State of residence | NA |

• BMI based on measured height and weight • Overweight (≥ 95th percentile) • At risk of overweight (≥ 85th percentile) |

ACS – active commuting to school; BF – body fat; BMI – body mass index; CDC – Center for Disease Control and Prevention; GIS – Geographic Information Systems; MVPA – moderate‐vigorous physical activity; NA – not available; NEWS‐Y – Neighborhood Environment Walkability Scale‐Youth; PA – physical activity; ST – sedentary time.

3.4. Measures of weight‐related behaviours and outcomes

With respect to weight‐related behaviours, PA and MVPA were the most common behavioural measures (Table 2). 27 , 29 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 36 , 43 , 44 , 47 Nine studies measured PA or MVPA through accelerometers or self‐reporting. Two studies measured ACS. 25 , 27 One study measured physical fitness using a maximal multistage 20‐m shuttle run test to determine the maximal aerobic power. 36 One study measured the number of sports teams or PA classes outside of school. 30

With respect to weight‐related outcomes, BMI and BMI z‐score were the most common health outcome measures. 25 , 27 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 36 , 43 , 45 , 46 , 47 Eleven studies measured the BMI based on objectively measured or self‐reported heights and weights, whereas five of these studies used BMI as the criterion to determine obesity (i.e., BMI greater than 95% quantile) or overweight status. One study derived body fat percentage (%BF) through bioelectrical impedance analysis and dichotomized the measure into low/high categories using the thresholds of 25% for boys and 30% for girls. 30 Waist circumference 43 and the sum of skinfolds 32 were also employed as health outcome measures.

3.5. Associations between walkability and weight‐related behaviours and outcomes

Out of the 13 studies, seven studies reported a significant association between measures of walkability and weight‐related behaviours (Table S1). Four studies reported a positive association between the walkability score and one of the following weight‐related behaviours: MVPA (p = 0.035), 27 MVPA (β = 0.278, p < 0.01), 31 ACS (p < 0.001) 25 or independent mobility (β = 0.25, p < 0.01). 43 Other studies, albeit not explicitly targeting walkability, found that walkability‐related environmental factors are also associated with weight‐related behaviours. It was found that the density of public transit (β = 0.037, p = 0.01) and intersections (β = 0.003, p = 0.04) 33 was positively associated with the MVPA of school children. The diversity of the land use mix (β = 1.049, p = 0.010) and street connectivity (β = 1.063, p = 0.010) was also found to be positively associated with objectively measured MVPA. 29 Another study also found that land use mix was positively associated with PA (β = 26, p = 0.015). 32

The associations between walkability and weight‐related outcomes were mixed. Three studies reported a null association. Three other studies reported a negative association between the walkability score with one of the following weight‐related outcomes: the prevalence of overweight (odds ratio [OR] = 0.98, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.95, 0.99) and obesity (OR = 0.97, 95% CI: 0.95, 0.99), 34 obesity (p < 0.05) 46 and BMI z‐scores (d = 0.3, p < 0.01) and waist circumference (d = 0.3, p < 0.001). 27 Two studies employed alternative measures of walkability for the correlation analysis: one study focused on the association between the density of subway stops and adiposity (β = −1.2, p = 0.001), 32 and the other study considered walkability as the number of parks within the 1‐mile buffer of the household and then correlated it with overweight (OR = 0.94, 95% CI: 0.90, 0.98) and risk of overweight (OR = 0.95, 95% CI: 0.92, 0.99). 45

3.6. Study quality assessment

Table S2 summarizes the scoring results of the study quality assessment based on the National Institutes of Health's Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross‐Sectional Studies. 42 The studies included in the review scored 9.2 out of 14 on average, with a range from 7 to 11.

4. DISCUSSION

Although the accumulated evidence supported associations between walkability and childhood obesity, few studies have reviewed such associations. In this study, we systematically reviewed 13 studies that evaluated the statistical relationships between walkability and weight‐related behaviours and/or outcomes among children and adolescents. Our review corroborates the conclusions of previous reviews. For instance, Rahman 48 concluded that children's built environment impacts their engagement in PA, which eventually lowers the risks of obesity; walkability, as one neighbourhood feature, plays an indispensable role in increasing the use of activity‐inducing amenities. Additionally, Booth 49 found that neighbourhoods with sufficient PA resources such as sidewalks are more likely to promote an active lifestyle. These previous reviews of obesity prevention factors, although relating to walkability, 48 , 49 have not systematically examined the effects on childhood obesity; it is this gap which our study aims to fill.

Although the majority of the studies in our review reported that higher levels of walkability in the built environment were associated with active lifestyles and healthy weight statuses, 25 , 27 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 36 , 46 other studies did not support this association. 29 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 47 These mixed findings, coupled with regional heterogeneity and a relatively small pool of qualified literature, do not permit us to draw a solid conclusion about the health‐promoting effects of living in walkable environments. This contraction can be explained by two methodological biases. First, actual environmental influences on human behaviour and health status have uncertainties, which arises as community‐based attributes, such as walkability, cannot entirely dictate people's daily activities, because a given community's influence is uncertain in both spatial and temporal scales. 50 It has been observed that people tend to travel out of their neighbourhoods for daily activities, so that factors affecting people's PA and weight status could exist beyond their immediate living environments. 51 One relevant example is that participants preferred to exercise in an activity‐inducing environment (e.g., inside a gym) rather than walking in their neighbourhood. 36 Second, the association with a walkability score alone does not permit us to justify the role of the built environment in facilitating walking. This statistical issue, known as the omitted‐variable bias, 52 occurs when one or more relevant variables are ignored in statistical analyses. Specifically, quantifying walkability using a predefined rubric cannot articulate other important qualitative variables, such as the aesthetics of the landscape, the presence of sidewalks or the quality of stores along the street. All of these variables could significantly affect young people's willingness to walk and exercise. 27 , 46 Also, another important factor omitted in some of these correlation analyses is the community's food environment, which could be health‐promoting (e.g., supermarkets) or health‐damaging (e.g., fast‐food restaurants). 53 For example, the inundation of unhealthy food provisioning in a community can offset the health benefits derived from PA. 46 The opportunities for and enjoyment of outdoor activities could also be affected by weather, seasonality and, more broadly, climate change. 54

This review has limitations. First, the majority of the walkability studies included in the review was cross‐sectional, with only one longitudinal study. This limitation on study inclusion weakens the ability to draw causal inferences to weight‐related behaviours and outcomes. 55 Second, because of the variety of walkability definitions, analysis methods and sample characteristics, we only summarized major findings in the review instead of adopting meta‐analysis in a comprehensive manner. Also, multiple statistical methods (e.g., generalized estimating equations, 33 linear regression 29 , 45 , 48 , 49 and logistic regression 25 , 34 ) were used to examine the associations differed across studies, which may lead to different results. These aspects can be improved by adopting rigorous reporting guidelines in the future. 56 Third, some studies 29 , 31 , 32 , 43 used self‐reported measures rather than objective measures to quantify weight‐related behaviours (e.g., PA, MVPA and sedentary time), which is prone to recall errors. 39 Fourth, confounding factors (e.g., family income, educational attainment, race and living conditions) varied across studies and could lead to the heterogeneity of correlation results. Although part of the confounders has been adjusted in the review, the adjustment could not be exclusive and could affect the accuracy of the results. Finally, studies included in the review only covered the United States and Europe; existing etiology about childhood obesity is mostly drawn from the evidence in urban areas of developed countries. Therefore, the conclusions found in these studies cannot be applied to the rural areas or regions in developing or underdeveloped countries, which often face a rising prevalence of obesity. 57

We expect this review to provide a sound reference for future studies on the associations between walkability and weight‐related behaviours and outcomes, thus helping to justify the health effects of community design in alleviating obesity. Future studies on childhood obesity should focus on ensuring consistency in measuring walkability to improve the quality of reporting. Also, longitudinal studies focused on a selected population group (e.g., African‐Americans) and areas with the greatest obesity challenges (e.g., developing countries) should be prioritized to justify public health interventions for improving neighbourhood walkability.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

We declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Data S1. Supporting Information

Table S1. Measures of walkability, weight‐related behaviors, and weight‐related outcomes in the studies included in the review

Table S2. Associations of walkability with weight‐related behaviors and/or outcomes in the studies included in the review

Table S3. Study quality assessment (based on the 14 questions in Appendix B)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the National Key R&D Program ‘Precision Medicine Initiative’ of China (2017YFC0907304), Sichuan Science and Technology Program (2019YJ0148), and the International Institute of Spatial Lifecourse Epidemiology (ISLE) for research support. [Correction added on 3 February 2021, after first online publication: Acknowledgements have been revised.]

Yang S, Chen X, Wang L, et al. Walkability indices and childhood obesity: A review of epidemiologic evidence. Obesity Reviews. 2021;22(S1):e13096. 10.1111/obr.13096

Shujuan Yang and Xiang Chen contributed equally to this work.

[Correction added on 3 February 2021, after first online publication: Peng Jia's correspondence details have been updated. Also, affiliations 9 and 10 were interchanged.]

[Correction added on 3 February 2021, after first online publication: Funding Information has been revised.]

Contributor Information

Yi Ning, Email: yi.ning@meinianresearch.com.

Peng Jia, Email: jiapengff@hotmail.com.

REFERENCES

- 1. WHO . Obesity and overweight. 2020.

- 2. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011‐2012. JAMA. 2014;311(8):806‐814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jia P, Ma S, Qi X, Wang Y. Spatial and temporal changes in prevalence of obesity among Chinese children and adolescents, 1985‐2005. Prev Chronic Dis. 2019;16:E160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kumar S, Kelly AS. Review of childhood obesity: from epidemiology, etiology, and comorbidities to clinical assessment and treatment. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(2):251‐265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wang Y, Jia P, Cheng X, Xue H. Improvement in food environments may help prevent childhood obesity: evidence from a 9‐year cohort study. Pediatr Obes. 2019;14:e12536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jia P, Xue H, Cheng X, Wang Y, Wang Y. Association of neighborhood built environments with childhood obesity: evidence from a 9‐year longitudinal, nationally representative survey in the US. Environ Int. 2019;128:158‐164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. El‐Behadli AF, Sharp C, Hughes SO, Obasi EM, Nicklas TA. Maternal depression, stress and feeding styles: towards a framework for theory and research in child obesity. Br J Nutr. 2015;113(Suppl):S55‐S71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Malik VS, Pan A, Willett WC, Hu FB. Sugar‐sweetened beverages and weight gain in children and adults: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98(4):1084‐1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Assuring the Health of the Public in the 21st Century . The Future of the Public's Health in the 21st Century. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Perdue WC, Stone LA, Gostin LO. The built environment and its relationship to the public's health: the legal framework. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(9):1390‐1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Forsyth A. What is a walkable place? The walkability debate in urban design. Urban Des Int. 2015;20(4):274‐292. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Smith L. Walkability Audit Tool. Workplace Health Saf. 2015;63(9):420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Barton J, Hine R, Pretty J. The health benefits of walking in greenspaces of high natural and heritage value. J Integr Environ Sci. 2009;6(4):261‐278. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jia P, Lakerveld J, Wu J, et al. Top 10 research priorities in spatial lifecourse epidemiology. Environ Health Perspect. 2019;127(7):74501. 10.1289/ehp4868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jia P, Yu C, Remais JV, et al. Spatial Lifecourse epidemiology reporting standards (ISLE‐ReSt) statement. Health Place. 2020;61:102243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kakwani N, Wagstaff A, Doorslaeff EV. Socioeconomic inequalities in health: measurement, computation, and statistical inference. J Econom. 1997;77(1):87‐103. 10.1016/s0304-4076(96)01807-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wagstaff A, Doorslaer EV. Income inequality and health: what does the literature tell us? Annu Rev Public Health. 2000;21(1):543‐567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Doorslaer EV, Wagstaff A, Bleichrodt H, et al. Income‐related inequalities in health: some international comparisons. J Health Econ. 1997;16:92‐112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Paola Roggero VM, Bustreo F, Rosati F. The health impact of child labor in developing countries: evidence from cross‐country data. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(2):271‐275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jia P, Luo M, Li Y, Zheng J‐S, Xiao Q, Luo J. Fast‐food restaurant, unhealthy eating, and childhood obesity: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Obes Rev. 2021;22(Suppl 1):e12944. 10.1111/obr.12944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Xin J, Zhao L, Wu T, et al. Association between access to convenience stores and childhood obesity: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2021; 22(Suppl 1):e12908. 10.1111/obr.12908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yitzhaki S. On an extension of the Gini inequality index. Int Econ Rev. 1983;24(3):617‐628. 10.2307/2648789 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kevin Johnston JMVH, Krivoruchko K, Lucas N. In: Kevin Johnston JMVH, Krivoruchko K, Lucas N, eds. Using ArcGIS Geostatistical Analyst; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Score W. Walk score methodology. 2020.

- 25. Molina‐García J, Queralt A. Neighborhood built environment and socioeconomic status in relation to active commuting to school in children. J Phys Act Health. 2017;14(10):761‐765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chalikavada R, Broder JC, O'Hara RL, Xue W, Gasevic D. The association between neighbourhood walkability and after‐school physical activity in Australian schoolchildren. Health Promot J Austr. 2020;NA. 10.1002/hpja.356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Molina‐García J, Queralt A, Adams MA, Conway TL, Sallis JF. Neighborhood built environment and socio‐economic status in relation to multiple health outcomes in adolescents. Prev Med. 2017;105:88‐94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chaosheng Zhang YT, Xu X, Kiely G. Towards spatial geochemical modelling: Use of geographically weighted regression for mapping soil organic carbon contents in Ireland. Appl Geochem. 2011;26:1239‐1248. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hinckson E, Cerin E, Mavoa S, et al. Associations of the perceived and objective neighborhood environment with physical activity and sedentary time in New Zealand adolescents. Int J Behav Nutr Phy. 2017;14(1):145. 10.1186/s12966-017-0597-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. McCrorie P, Mitchell R, Macdonald L, et al. The relationship between living in urban and rural areas of Scotland and children's physical activity and sedentary levels: a country‐wide cross‐sectional analysis. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1‐11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kligerman M, Sallis JF, Ryan S, Frank LD, Nader PR. Association of neighborhood design and recreation environment variables with physical activity and body mass index in adolescents. Am J Health Promot. 2007;21(4):274‐277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lovasi GS, Jacobson JS, Quinn JW, Neckerman KM, Ashby‐Thompson MN, Rundle A. Is the environment near home and school associated with physical activity and adiposity of urban preschool children? J Urban Health. 2011;88(6):1143‐1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Buck C, Tkaczick T, Pitsiladis Y, et al. Objective measures of the built environment and physical activity in children: from walkability to moveability. J Urban Health. 2015;92(1):24‐38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Slater SJ, Nicholson L, Chriqui J, Barker DC, Chaloupka FJ, Johnston LD. Walkable communities and adolescent weight. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(2):164‐168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Stowe EW, Hughey SM, Hallum SH, Kaczynski AT. Associations between walkability and youth obesity: differences by urbanicity. Child Obes. 2019;15(8):555‐559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cheah WL, Chang CT, Saimon R. Environment factors associated with adolescents' body mass index, physical activity and physical fitness in Kuching South City, Sarawak: a cross‐sectional study. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2012;24(4):331‐337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhou Y, Buck C, Maier W, von Lengerke T, Walter U, Dreier M. Built environment and childhood weight status: a multi‐level study using population‐based data in the City of Hannover, Germany. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(8):2694. 10.3390/ijerph17082694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wilding S, Ziauddeen N, Smith D, Roderick P, Chase D, Alwan NA. Are environmental area characteristics at birth associated with overweight and obesity in school‐aged children? Findings from the SLOPE (studying lifecourse obesity predictors) population‐based cohort in the south of England. BMC Med. 2020;18:1‐13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Grasser G, Van Dyck D, Titze S, Stronegger W. Objectively measured walkability and active transport and weight‐related outcomes in adults: a systematic review. Int J Public Health. 2013;58(4):615‐625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lovasi GS, Grady S, Rundle A. Steps forward: review and recommendations for research on walkability, physical activity and cardiovascular health. Public Health Rev. 2012;33(4):484‐506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8(5):336‐341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. National Heart L, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) . Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross‐Sectional Studies. Bethesda: National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services; 2014:103‐111. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Noonan RJ, Boddy LM, Knowles ZR, Fairclough SJ. Cross‐sectional associations between high‐deprivation home and neighbourhood environments, and health‐related variables among Liverpool children. BMJ Open. 2016;6(1):e008693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rosenberg D, Ding D, Sallis JF, et al. Neighborhood environment walkability scale for youth (NEWS‐Y): reliability and relationship with physical activity. Prev Med. 2009;49(2‐3):213‐218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wasserman JA, Suminski R, Xi J, Mayfield C, Glaros A, Magie R. A multi‐level analysis showing associations between school neighborhood and child body mass index. Int J Obes (Lond). 2014;38(7):912‐918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Shahid R, Bertazzon S. Local spatial analysis and dynamic simulation of childhood obesity and neighbourhood walkability in a major Canadian City. AIMS Public Health. 2015;2(4):616‐637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Graziose MM, Gray HL, Quinn J, Rundle AG, Contento IR, Koch PA. Association between the built environment in school neighborhoods with physical activity among New York City children, 2012. Prev Chronic Dis. 2016;13:E110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rahman T, Cushing RA, Jackson RJ. Contributions of built environment to childhood obesity. Mt Sinai J Med. 2011;78(1):49‐57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Booth KM, Pinkston MM, Poston WS. Obesity and the built environment. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105(5 Suppl 1):S110‐S117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jia P, Xue H, Cheng X, Wang Y. Effects of school neighborhood food environments on childhood obesity at multiple scales: a longitudinal kindergarten cohort study in the USA. BMC Med. 2019;17(1):99. 10.1186/s12916-019-1329-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Chen X, Kwan MP. Contextual uncertainties, human mobility, and perceived food environment: the uncertain geographic context problem in food access research. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(9):1734‐1737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Richardson J, Wildman J, Robertson IK. A critique of the World Health Organisation's evaluation of health system performance. Health Econ. 2003;12(5):355‐366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Chen X, Yang X. Does food environment influence food choices? A geographical analysis through “tweets”. Appl Geogr. 2014;51:82‐89. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Jia P, Wang T, van Vliet AJH, Skidmore AK, van Aalst M. Worsening of tree‐related public health issues under climate change. Nat Plants. 2020;6(2):48. 10.1038/s41477-020-0598-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Jia P. Spatial lifecourse epidemiology. Lancet Planet Health. 2019;3(2):e57‐e59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Richard Rheingans OC, Anderson J, Showalter J. Estimating inequities in sanitation‐related disease burden and estimating the potential impacts of pro‐poor targeting 2012.

- 57. Zhang X, Zhang M, Zhao ZP, et al. Obesogenic environmental factors of adult obesity in China: a nationally representative cross‐sectional study. Environ Res Lett. 2020;15(4):044009. 10.1088/1748-9326/ab6614 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1. Supporting Information

Table S1. Measures of walkability, weight‐related behaviors, and weight‐related outcomes in the studies included in the review

Table S2. Associations of walkability with weight‐related behaviors and/or outcomes in the studies included in the review

Table S3. Study quality assessment (based on the 14 questions in Appendix B)