Abstract

Contemporary developments in molecular biology have been combined with discoveries on the analysis of the role of all non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) in human diseases, particularly in cancer, by examining their roles in cells. Currently, included among these common types of cancer, are all the lymphomas and lymphoid malignancies, which represent a diverse group of neoplasms and malignant disorders. Initial data suggest that non-coding RNAs, particularly long ncRNAs (lncRNAs), play key roles in oncogenesis and that lncRNA-mediated biology is an important key pathway to cancer progression. Other non-coding RNAs, termed microRNAs (miRNAs or miRs), are very promising cancer molecular biomarkers. They can be detected in tissues, cell lines, biopsy material and all biological fluids, such as blood. With the number of well-characterized cancer-related lncRNAs and miRNAs increasing, the study of the roles of non-coding RNAs in cancer is bringing forth new hypotheses of the biology of cancerous cells. For the first time, to the best of our knowledge, the present review provides an up-to-date summary of the recent literature referring to all diagnosed ncRNAs that mediate the pathogenesis of all types of lymphomas and lymphoid malignancies.

Keywords: long non-coding RNAs, microRNAs, B-cell lymphoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, Hodgkin lymphoma, multiple myeloma, biomarkers

1. Introduction

Lymphomas are a heterogeneous group of cancers; more specifically, they consist of a group of blood disorders derived from lymphocytes and are presented with multiple variations in clinical presentation, long-term prognosis and pathogenesis. They represent one of the most common types of cancer worldwide and affect numerous patients. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification report, there are approximately 100 different types of lymphoma. The two main categories of lymphomas are non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) (consisting 9 out of 10 of all lymphoma cases) and Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) (consisting 1 out of 10 of all lymphoma cases) (1–3). Furthermore, non-Hodgkin lymphomas can be grouped into B- and T-cell NHLs (TNHLs), which account for approximately 90 and 10% of NHLs, respectively (4,5). According to the WHO, two other categories are also considered as types of lymphoid tissue tumors: Multiple myeloma (MM) and immunoproliferative diseases (3).

Epidemiology

According to the WHO, there are the following lymphoma subtypes (WHO 2016): i) Mature B-cell neoplasms; ii) mature T-cell and natural killer (NK) cell neoplasms; iii) precursor lymphoid neoplasms; iv) HL; and v) immunodeficiency-associated lymphoproliferative disorders (4,5).

B-cell NHLs (BCNHLs) are tumors of B-cells that exhibit a heterogeneity that is attributed to the fact that these tumors are derived from different stages of mature B-cell differentiation. The main subtypes of BCNHLs are the following: i) diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL); ii) chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL); iii) follicular lymphoma (FL); iv) mantle cell lymphoma (MCL); v) Burkitt's lymphoma (BL); vi) marginal zone lymphoma (MZL); and vii) mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) (6). The majority of BCNHLs, such as DLBCL and FL, have passed the germinal center (GC) reaction, indicating that their immunoglobulin (IG) genes have been hypermutated. Other subtypes, such as MCL and CLL, are derived from GC-inexperienced B-cells (7).

The most common subtypes of TNHLs and NK-cell NHLS (NK-NHLs) are the following: i) Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas (mycosis fungoides, Sezary syndrome and others); ii) adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma; iii) angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma; iv) extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma; nasal type; vi) enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma; and vii) anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) (4).

Risk factors and diagnosis of lymphomas

The most common risk factors for HL are Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection and a family history of the disease (8). The most common risk factors for several types of NHLs include the following: i) Autoimmune diseases, such as Sjögren syndrome, celiac disease, rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus; ii) HIV/AIDS infection; iii) human T-lymphotropic virus infection; iv) Helicobacter pylori infection; v) HHV-8 infection; vi) hepatitis C virus infection; vii) medical treatments (patients who have been previously treated for Hodgkin lymphoma, methotrexate and the tumor necrosis factor-a inhibitors); viii) genetic diseases; and ix) certain chemical agents (benzene and certain herbicides and insecticides; weed- and insect-killing substances) (9–15). Some environmental agents, such as red meat consumption and tobacco smoking may also play a role in increasing the risk of developing NHL (11,12,16).

The diagnosis of lymphomas can be achieved due to the enlargement of lymph nodes, which can be determined by performing a lymph node biopsy (17). A lymph node biopsy commonly is followed by performing immunophenotyping, flow cytometry, fluorescence in situ hybridization testing, bone marrow aspiration and bone marrow biopsy (18). Imaging via computed tomography of the chest and upper-lower abdomen may then be performed to determine the possible expansion of the lymphoma throughout the human body (17).

Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs)

ncRNAs are RNAs that are not translated to proteins. Over the past ten years, a number of ncRNAs have been identified. Any of the three RNA polymerases (RNA Pol I, RNA Pol II or RNA Pol III) can perform the transcription of a ncRNA. The ncRNAs are divided into the following two main categories: Small ncRNAs, <200 bp in length and long ncRNAs (lncRNAs), >200 bp in length (19).

In these two categories, several individual categories of ncRNAs also exist. These include housekeeping ncRNAs [transfer RNAs (tRNAs) and some ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs)], which are essential for fundamental principles of cellular biology, small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs), and a number of recently observed RNAs which are associated with the transcription of genes into proteins (20).

MicroRNAs (miRNAs or miRs)

To date, miRNAs are the less extensively studied ncRNAs for their roles in cancer. Over the past years, a number of targeted reviews have been published (21–23), which have described a complex basic mechanism through which miRNAs can lead to the silencing of target gene expression; through the formation of a silencing complex induced by RISC-induced RNA, which uses proteins from the Argonaute family (such as AGO2) for the splicing of target mRNAs or for the suspension of the translation of these mRNAs (21). The patterns of expression of miRNAs in different cancer types have been well-observed, and studies have highlighted numerous miRNAs, such as miR-10b, let-7, miR-101 and miR-15a-16 complex-1, which have oncogenic or tumor-suppressive functions (22,23).

lncRNAs

Recent observations of new species of lncRNAs have led to the development of various possible candidates as lncRNAs. Although a number of RNAs have a length of >200 bp, such as repeat sequence transcripts and pseudogenes (24), the term lncRNA (also referred to as lincRNAs, for long transgenic ncRNAs) is not used in the same manner in all cases.

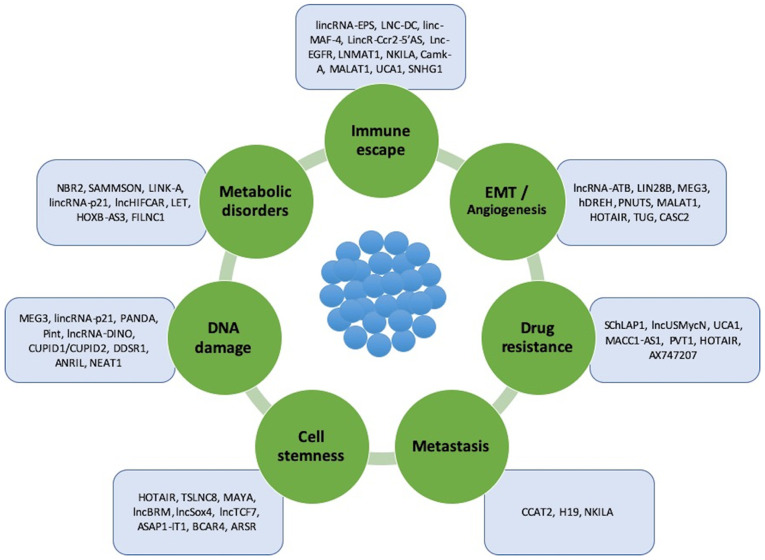

A number of common features of lncRNAs have been indicated to confirm their biological identity, such as the following: i) Epigenetic regulation as in a transcripted gene; ii) transcription performed by RNA polymerase II; iii) poly-adenylation to the 3′-untranslated region (3′-UTR); iv) frequent splicing of multiple exons through specific molecular patterns; v) regulation by classic transcription factors; and vi) frequent tissue-specific expression (24) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

lncRNAs involved in oncogenesis, tumor progression and metastasis. These lncRNAs can be divided into 7 subtypes based on the process/property in which they are involved: Immune system escape, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, and angiogenesis, drug resistance, metastasis, cell stemness, DNA damage and metabolic disorders. lncRNAs, long non-coding RNAs.

ncRNAs in normal B-cell differentiation and T-cell development

B-cell differentiation in adult humans begins within the bone marrow (BM) and is continued thereafter in the lymph nodes, tonsils and spleen (25). On the other hand, T-cells a derived from bone marrow hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), whose progenitors migrate to and colonize the thymus (26).

The most common lncRNAs affecting normal B-cells are the following: i) MYB-AS1, SMAD1-AS1 and LEF1-AS1, located on 6q23.3, 4q31.21 and 4q25, respectively, are involved in early B-cell development; ii) CRNDE, located on 16q12.2-involved in mitotic cell cycle related processes; and iii) RP11-132N15.3/lnc-BCL6-3, located on 3q27.3, and involved in the modulation of the GC reaction. However, data on the roles of lncRNAs in normal T-cells are limited (27–31).

miRNAs are also involved in lymphocyte development, as first described in 2004; it was demonstrated that miR-223, miR-181 and miR-142 were highly expressed in B-cells (32). miR-181 can also contribute to the regulation of the levels of CD69, BCL2 and TCR during T-cell development. In addition, miR-155 and miR-181 play key roles in the regulation of GC B-cell differentiation (33).

It is essential knowledge that all ncRNAs may play a vital role as predictive and prognostic biomarkers in the pathogenesis and progression of lymphomas and lymphoid malignancies in general. The main aim of the present review was to provide an up-to-date summary of available information on all the known miRNAs and lncRNAs that participate in the development of all lymphoid disorders, with a main focus on their connection to each lymphoma subtype. Furthermore, these molecular biomarkers may be used, in the near future, in the therapeutic management of the majority of lymphomas. Thus, the present review summarizes all published data to date on ncRNAs, in order to shed light on the future perspectives of lymphoma management.

2. Literature search

A literature search was performed, including studies published up to August, 2020, using the following databases: Medline (PubMed), Science Direct, Web of Science and Google Scholar.

Systematic reviews, uncontrolled prospective, retrospective and experimental studies were included for each specific subject (total no. of studies, n=235). The following inclusion criteria were applied: Studies concerning ncRNAs, lncRNAs, miRNAs, cancer and lymphomas: HLs, and BCNHLs and TNHLs. All studies concerning the association of lncRNAs and miRNAs with NHLs and HLs were included.

3. Non-coding RNAs in lymphomas

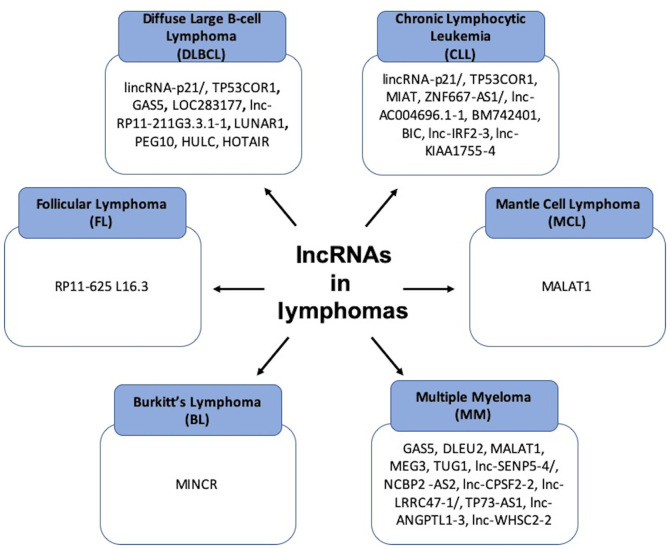

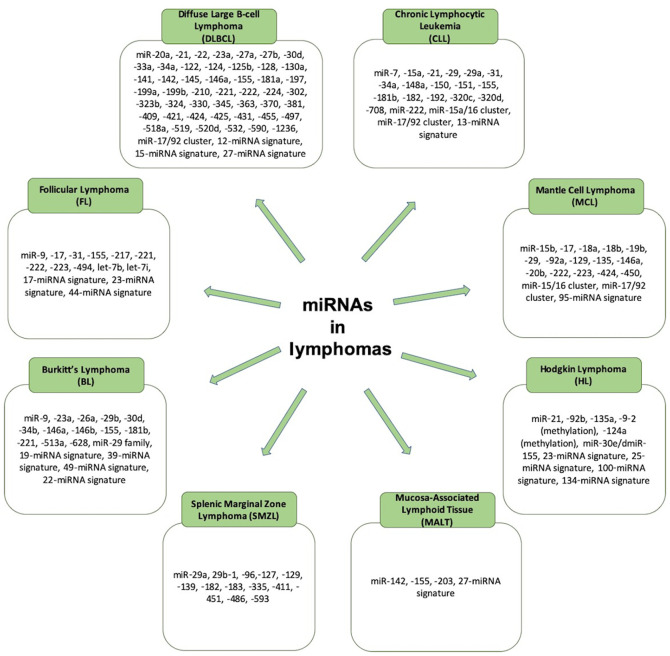

Over the past years, a number of studies have referred to the significance of lncRNAs and miRNAs in the pathophysiology of lymphomas, particularly B-cell NHLs. There are different non-coding RNAs that play a role in each subtype of lymphoma, and these are referred to the sections and tables below (Figs. 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

Summary of the major lncRNAs that are involved in different types of lymphomas. lncRNAs, long non-coding RNAs.

Figure 3.

Summary of the miRNAs that are involved in different types of lymphomas. miRNAs, microRNAs.

a) BCNHLs

DLBCL

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is the most common form of NHL among adults (34) and it occurs most often in older-aged individuals, with a median age of diagnosis approaching the seventh decade of a patient's life (35). There are 2 different molecular subtypes of DLBCL: GC B-cell like (GC-DLBCL) and activated B-cell like (ABC-DLBCL) (36,37).

Subtypes of DLBCLs with a distinctive morphology or immunophenotype are the following: i) T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma; ii) ALK+ large B-cell lymphoma; iii) plasmablastic lymphoma; iv) intravascular large B-cell lymphoma; and v) large B-cell lymphoma with IRF4 rearrangement (38,39).

Subtypes of DLBCLs with distinctive clinical issues are the following: i) Primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma; ii) primary cutaneous DLBCL, leg type; iii) primary DLBCL of the central nervous system; iv) DLBCL associated with chronic inflammation; v) lymphomatoid granulomatosis; and vi) primary effusion lymphoma (38,39).

Additionally, there are DLBCLs driven by viruses, such as the following: i) EBV-positive DLBCL, not otherwise specified; and ii) HHV8-positive DLBCL, NOS (Not otherwise specified). There are also DLBCLs driven by disorders related to DLBCL, such as: i) Helicobactor pylori-associated DLBCL; and ii) EBV-positive mucocutaneous ulcer (40,41).

In order for a B-cell to be developed or to progress into a DLBCL type, changes in the following genes need to occur: BCL2 (42), BCL6 (42), MYC (36), EZH2 (43), MYD88 (42), CREBBP (44), CD79A and CD79B (44) and PAX5 (44). Therefore, the neoplastic cells in DLBCL exhibit a pathologically overactivation of the nuclear factor (NF)-κB, phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), Janus kinase (JAK)/signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT), mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), B-cell receptor and Toll-like receptor pathways (42).

Concerning miRNAs in DLBCLs, it has been shown than in ABC-type DLBCL lymphoma, there is a high expression of miR-21, miR-146a, miR155, miR-221 and miR-363, while in GCB-type DLBCL, there is a high expression of miR-421 and the miR-17~92 cluster (45–50) (Table I). In serum samples of patients with DLBCL, increased levels of miR-21, miR-155 and miR-210 have been identified, along with increased levels of miR-124, miR-532-5p miR-15a, miR-16, miR-29c and miR-155. Decreased levels of miR-122, miR-128, miR-141, miR-145, miR-197, miR-345, miR-424 and miR-425 have been also found in the serum of patients with DLBCL. miR-27a, miR-142, miR-199b, miR-222, miR-302, miR-330, miR-425 and miR-519 seem to be associated with the overall survival of patients with DLBCL (50). In any case, miR-155, miR-34a, miRNA-21, miRNA-23a, miRNA-27b, miRNA-34a, 12-miRNA signature, 15-miRNA signature, 27-miRNA signature, miR-363, miR-518a, miR-181a, miR-590, miR-421 and miR-324-either in serum samples, or in tissue or cell line samples of patients with DLBCL, can be used as diagnostic biomarkers in patients with DLBCL (50–71) (Table I and Fig. 3).

Table I.

miRNAs and lncRNAs identified in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

| miRNA(s)/lncRNA | Genome location (if defined) | Role | Molecular mechanism/sample | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-155 | Diagnostic biomarker | Presence in serum | (51) | |

| miR-34a | Diagnostic biomarker | Presence in serum | (52) | |

| miR-17/92 cluster | Cell survival, prognostic biomarker | Subtyping | (53) | |

| miR-21, miR-23a, miR-27b, miR-34a | Poor overall survival, diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers | Presence in serum | (54–58) | |

| miR-20a, miR-30d, miR-22, miR-146a | Prognostic biomarkers | Presence in tissues | (59) | |

| miR-21, miR-210 | Diagnostic biomarkers | Presence in serum | (60) | |

| 12-miRNA signature, 15-miRNA signature, 27-miRNA signature | Diagnostic biomarkers | Presence in tissue | (61–64) | |

| miR-155, miR-221, miR-222, miR-21, miR-363, miR-518a, miR-181a, miR-590, miR-421, miR-324 | Diagnostic biomarkers | Presence in cell lines | (65) | |

| miR-124, miR-532, miR-122, miR-128, miR-141, miR-145, miR-197, miR-345, miR-424, miR-425 | Diagnostic biomarkers | Presence in plasma and exosomes | (66) | |

| miR-34a, miR-323b, miR-431 | Diagnostic biomarkers | Presence in serum | (67) | |

| miR-27a, miR-142, miR-199b, miR-222, miR-302, miR-330, miR-425, miR-519 | Predictive biomarkers | Presence in tissue | (46) | |

| miR-224, miR-455, miR-1236, miR-33a, miR-520d | Predictive biomarkers | Presence in serum | (68) | |

| miR-125b, miR-130a, miR-199a, miR-497, miR-370, miR-381, miR-409 | Predictive biomarkers | Presence in tissue, blood and cell lines | (69–71) | |

| lincRNA-p21/TP53COR1 | 17p13.1 (mouse) 6p21.2 (human) | Tumor-suppressor | Link to cyclin D1, CDK4 and p21 | (72–76) |

| GAS5 | 1q25.1 | Tumor-suppressor | Regulation of mTOR pathway | (77–86) |

| LOC283177 | 11q25 | Uncharacterized | Not described | (87) |

| lnc-RP11-211G3.3.1-1 | 3q27.3 | Uncharacterized | Not described | (88) |

| LUNAR1 | 15q26.3 | oncomiR progenitor | NOTCH1 regulation. Enhances IGF1R mRNA expression | (89,90) |

| PEG10 | 7q21.3 | oncomiR progenitor | Activated by c-MYC | (91–93) |

| HULC | 6p24.3 | oncomiR progenitor | Not described | (94–97) |

| HOTAIR | 12q13.13 | oncomiR progenitor | Regulation of the PI3K/AKT/NF-κB pathway | (98) |

lncRNA, long non-coding RNA; miRNA/miR, microRNA.

Concerning lncRNAs in patients with DLBCLs, the following have been observed (Table I): i) lincRNA- p21/TP53COR1, located chromosome on 6p21.2 (human), acting as a tumor suppressor by linking to cyclin D1, CDK4 and p21 (72–76); ii) GAS5, located on chromosome 1q25.1, acting as a tumor suppressor by regulating the mTOR pathway (77–86); iii) LOC283177, located on chromosome 11q25, with an uncharacterized mode of action (87); iv) lnc-RP11-211G3.3.1-1, located on chromosome 3q27.3, with an uncharacterized mode of action (88); v) LUNAR1, located on chromosome 15q26.3, acting as an oncomiR progenitor by regulating NOTCH1 and enhancing insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF1R) mRNA expression (89,90); vi) PEG10, located on chromosome 7q21.3, acting as an oncomiR progenitor, and being activated by c-MYC (91–93); vii) HULC, located on chromosome 6p24.3, acting as an oncomiR progenitor (94–97); viii) HOTAIR, located on chromosome 12q13.13, acting as an oncomiR progenitor, via the regulation the of the PI3K/AKT/NF-κB pathway (98) (Fig. 2).

CLL

CLL is the most common form of leukemia affecting adults (99). In the case that along with CLL, there are enlarged lymph nodes, this clinical condition is referred to as small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL). The groups of CLL/SLL monoclonal B-cells are the following: Low-count CLL/SLL with a number of monoclonal B-cells <0.5×109 cells/liter (i.e. 0.5×109/l), and high-count CLL/SLL MBL with monoclonal B-cells ≥0.5×109/l but <5×109/l (99). A patient is diagnosed as having CLL if the number of monoclonal B-cells are >5×109/l (100,101). Classical CLL, according to the Matutes score (102), includes the expression of five different markers in the immunophenotype: These are CD5, CD23, FMC7, CD22 and immunoglobulin light chain (102–104).

Concerning miRNAs in CLL, miR-15a/16-1 acts as a tumor suppressor in patients with CLL and its expression is therefore found to be decreased (105,106), while miR-7-5p, miR-182-5p and miR-320c/d are regulated by p53, and are increased in patients with CLL (107,108). miR-181b expression is also low in patients with CLL (with a poor outcome) (109). miR-155 is overexpressed in patients with CLL and together with miR-21, lead to higher mortality levels in patients with CLL (110) (Table II and Fig. 3).

Table II.

miRNAs and lncRNAs identified in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

| miRNA(s)/lncRNA | Genome location (if defined) | Role/activation | Molecular mechanism/sample | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-15a/16 cluster, miR-7, miR-182, miR-320c/d, miR-29, miR-192 | Diagnostic biomarkers | Presence in PBMCs and cell lines | (107,108,115,116) | |

| miR-151, miR-34a, miR-31, miR-155, miR-150, miR-15a, miR-29a | Diagnostic biomarkers | Presence in serum | (113–114) | |

| miR-181b, miR-21, miR-155, miR-708, miR-17~92 cluster, 13-miRNA signature, miR-150, miR-155 | Prognostic biomarkers | Presence in PBMCs, cell lines, serum, blood cells | (115,133–135) | |

| miR-181b, miR-155, miR-21, miR-148a, miR-222 | Predictive biomarkers | Presence in PBMCs and cell lines | (133–135) | |

| DLEU2 | 13q14.3 | Tumor suppressor | NF-κB activation | (117–120) |

| NEAT1 | 11q13.1 | Tumor-suppressor | Induction by p53 | (121,122) |

| lincRNA-p21/TP53COR1 (mouse) 6p21.2 (human) | 17p13.1 | Tumor-suppressor | Induction by p53 | (72–76) |

| MIAT | 22q12.1 | Oncogene | Regulatory loop with OCT4 | (123–126) |

| ZNF667-AS1/lnc-AC004696.1-1 | 19q13.43 | Uncharacterized | Not described | (127,128) |

| BM742401 | 18q11.2 | Tumor-suppressor | Not described | (129,130) |

| BIC | 21q21 | oncomiR progenitor | Host of miR-155-5p and miR-155-3p | (131,132) |

| lnc-IRF2-3 | 4q35 | Uncharacterized | Not described | (128) |

| lnc-KIAA1755-4 | 20q11.23 | Uncharacterized | Not described | (128) |

lncRNA, long non-coding RNA; miRNA/miR, microRNA; PBMCs, peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

Additionally, patients with CLL are characterized by higher levels of miR-34a, miR-31, miR-155, miR-150, miR-15a and miR-29a; these can be used as diagnostic biomarkers (110–115). In particular, miR-192 is expressed in low levels in patients with CLL and can be thus used a diagnostic biomarker for CLL (116) (Table II).

Concerning lncRNAs in patients with CLL, the following have been observed (Table II): i) DLEU2, located on chromosome 13q14.3, acting as tumor suppressor by activating the NF-κB pathway (117–120); ii) NEAT1, located on chromosome 11q13.1, acting as a tumor suppressor via induction by p53 (121,122); iii) lincRNA-p21/TP53COR1, located on chromosome p21.2 (human), acting as a tumor suppressor via induction by p53 (72–76); iv) MIAT, located on chromosome 22q12.1, acting as an oncogene by forming a regulatory loop with OCT4 (123–126); v) ZNF667-AS1/lnc-AC004696.1-1, located on chromosome 19q13.43, with an uncharacterized mode of action (127,128); vi) BM742401, located on chromosome 18q11.2, acting as a tumor suppressor, with an uncharacterized mode of action (129,130); vii) BIC, located on chromosome 21q21, acting as an oncomiR progenitor by being a host of miR-155-5p and miR-155-3p (131,132); viii) lnc-IRF2-3, located on chromosome 4q35 with an uncharacterized mode of action (128); ix) lnc-KIAA1755-4, located on chromosome 20q11.23 with an uncharacterized mode of action (128) (Fig. 2).

Finally, in Table II, references are provided of all the other miRNAs used as predictive and prognostic biomarkers in clinical trials of patients with CLL (133–135).

FLs

FL is the second most common type of NHL, and the most common indolent NHL. It derives from the uncontrolled division of centrocytes and centroblasts of the follicles in the GCs of lymph nodes.

The genomic alterations that can be found in FL include the following: i) the t(14:18)(q32:q21.3) translocation (the majority of the cases); ii) 1p36 deletions (second most common genomic alteration in FL) that lead to the loss of TNFAIP3; iii) mutations in PRDM1; and iv) the same mutations observed in in situ FL (ISFL), including KMT2D, CREEBP, BCL2 and EZH2, as well as other mutations (45).

According to the WHO criteria, there are differences, which can be observed under a microscope, which can be used to diagnose and categorize FL into the following 3 grades, with grade 3 comprising A and B subtypes (46): Grade 1, follicles with <5 centroblasts per high-power field (hpf); grade 2, follicles with 6 to 15 centroblasts per hpf; grade 3, follicles with >15 centroblasts per hpf; grade 3A, grade 3 in which the follicles contain predominantly centrocytes; grade 3B, grade 3 in which the follicles consist almost entirely of centroblasts.

Low-grade FLs are grades 1 and 2, as well as grade 3A. Grade 3B is regarded as a highly aggressive FL, which can be easily transformed into a higher grade (46). The transformation of FL into a more aggressive state or other type of aggressive lymphoma is associated with specific genetic alterations, such as in the following genes: CREEBP, KMT2D, STAT6, CARD11, CD79, TNFAIP3, CD58, CDKN2A or CDKN2B, TNFRSF4 and c-MYC (45,46,136–138).

Concerning miRNAs in FLs, a number of studies have demonstrated that there is an increase in the levels of 6 particular miRNAs: miR-223, miR-217, miR-222, miR221, let-7i and let-7b in patients with FL, in which their lymphoma underwent a transformation. In addition, the miR-17~92 cluster can be used as a useful diagnostic biomarker found in patients with FL, while miR-20a/b and miR-194 can also be found in patients with FL. Other useful diagnostic biomarkers in patients with FL may be the following: miR-9, miR-155, miR-31, miR-17, miR-217, miR-221, miR-222, miR-223, let-7i, let-7b17-miRNA signature, 44-miRNA signature, miR-494 23-miRNA signature (136–140) (Table III and Fig. 3).

Table III.

miRNAs and lncRNAs identified in patients with follicular lymphoma.

| miRNA(s)/lncRNA | Genome location (if defined) | Role/activation | Molecular mechanism/sample | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RP11-625 L16.3 | 12 | Uncharacterized | Not described | (72) |

| miR-9, miR-155, miR-31, miR-17 | Diagnostic biomarkers | Presence in tissues | (136,137) | |

| miR-217, miR-221, miR-222, miR-223, let-7i, let-7b | Diagnostic biomarkers | Presence in tissues | (138,140) | |

| 17-miRNA signature, 44-miRNA signature, miR-494 | Diagnostic biomarkers | Presence in tissues | (138,139) | |

| 23-miRNA signature | Predictive biomarkers | Presence in tissues | (139) |

lncRNA, long non-coding RNA; miRNA/miR, microRNA.

Concerning lncRNAs in patients with FL, studies have demonstrated that there are 3-fold as many lncRNAs that are upregulated than lncRNAs that are downregulated in patients with FL3A stage disease, without their biological functions being cleared yet. The only lncRNA that seems to be upregulated in patients with FL3A grade disease is RP11-625 L16.3, located on chromosome 12, with an uncharacterized mode of action (72) (Table III and Fig. 2).

MCLs

MCL is recognizable as an aggressive and incurable small B-cell lymphoma. It predominantly affects older-aged males (>60 years old), and sometimes it may be indolent in some patients. MCLs arise from the mantle zone of early B-cells of the lymph node follicle and they possess the t(11;14)(q13;q32) translocation with an overexpression of cyclin D1.MCL cells also exhibit CD5+ and CD23− and surface IgM/D expression (141,142).

Two types of clinically indolent variants have now been identified (140,141). Classical MCL with IGHV-unmutated or minimally mutated B-cells and SOX11 overexpression; usually presented in lymph nodes and other extranodal sites. Additional molecular/cytogenetic abnormalities may be presented in blastoid or pleomorphic MCL. Leukemic non-nodal MCL develops from IGHV-mutated SOX11 B-cells, and is usually presented in peripheral blood, BM and spleen (142).

Concerning miRNAs in MCLs, a number of studies have demonstrated the overexpression of miR-15/16 and miR-17~92 in MCL and that this is associated with an aggressive form of the disease (143,144). In addition, the inhibition of miR-29 has been demonstrated to lead to the progression of MCL (a potential prognostic marker for MCL) (143–145). Additionally, the 95-miRNA signature can be a diagnostic biomarker for MCL (145) (Table IV and Fig. 3).

Table IV.

miRNAs and lncRNAs observed in patients with mantle-cell lymphoma.

| miRNA(s)/lncRNA | Genome location (if defined) | Role/activation | Molecular mechanism/sample | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MALAT1 | 11q13 | Oncogene | Regulation of the bioavailability of TGF-β | (146–152) |

| miR-15/16, miR-17/92 | Diagnostic biomarker | Presence in cell lines | (141,142) | |

| 95-miRNA signature | Diagnostic biomarker | Presence in tissues | (143) | |

| miR-15b, miR-129, miR-135, miR-146a, miR-424, miR-450, miR-222, miR-17, miR-18a, miR-19b, miR-92a (miR-17/92 cluster) | Prognostic biomarkers | Presence in tissues | (144,153) | |

| miR-29, miR-20b, miR-18b | Prognostic biomarkers | Presence in cell lines and tissues | (154–156) | |

| miR-223 | Prognostic biomarkers | Presence in PBMCs and cell lines | (157) |

lncRNA, long non-coding RNA; miRNA/miR, microRNA; PBMCs, peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

Concerning lncRNAs in patients with MCL, it has been demonstrated that MALAT1 is overexpressed in human MCL tissues and cell lines compared to normal B-cells [a high international prognostic index (IPI) is present], and is associated with the lower overall survival of patients with MCL (146). Thus, MALAT1, located on 11q13 chromosome, can act as an oncogene in patients with MCL (regulation of the bioavailability of TGF-β) (146–152) (Table IV and Fig. 2).

Finally, in Table IV, references of all the other miRNAs that have been observed in patients with MCL and used as prognostic biomarkers in clinical trials are presented (153–157).

BL

BL is a type of aggressive B-NHL. It may be presented with any of three main clinical variants: Endemic BL, sporadic BL and the immunodeficiency-associated BL (158). In all types of BL, the dysregulation of the c-myc gene is observed (the gene is found at 8q24), presented with any one of the three known chromosomal translocations (159). The most common variant is t(8;14)(q24;q32), which involves c-myc and IGH (159).

The variant at t(2;8)(p12;q24) involves IGK and c-myc (160). The variant at t(8;22)(q24;q11) involves IGL and c-myc (160). In addition, a last variant of three-way translocation, t(8;14;18) has been identified (161).

Concerning miRNAs in patients with BL, it seems that MYC regulates and is regulated by numerous miRNAs (Table V), the most common of which are the following: miR-23a, miR-26a, miR-29b, miR-30d, miR-146a, miR-146b, miR-155, and miR-221 (162–165) [widely used as diagnostic biomarkers (166–173)] (Table V and Fig. 3).

Table V.

miRNAs and lncRNAs identified in patients with Burkitt's lymphoma.

| miRNA(s)/lncRNA | Genome location (if defined) | Role/activation | Molecular mechanism/sample | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MINCR | 8q24.3 | Uncharacterized | Induction of MYC | (173) |

| miR-23a, miR-26a, miR-29b, miR-30d, miR-146a, miR-146b, miR-155, miR-221 | Diagnostic biomarkers | Presence in tissues | (165) | |

| 22-miRNA signature, miR-513a, miR-628, miR-9 | Diagnostic biomarkers | Presence in tissues | (166,167) | |

| 39-miRNA signature, 19-miRNA signature, 49-miRNA signature | Diagnostic biomarkers | Presence in tissues | (168–171) | |

| miR-34b, miR-29 family, miR-181b | Diagnostic biomarkers | Presence in cell lines and tissues | (167,171–173) |

lncRNA, long non-coding RNA; miRNA/miR, microRNA.

Concerning lncRNAs in patients with BL, 13 lncRNAs have been identified thus far (173). The most well-identified lncRNA in patients with BL is MINCR, located on chromosome 8q24.3, with an uncharacterized role; but it seems that it causes the induction of myc and modulates its transcriptional program (173).

Other indolent BCNHLs

There are also two other types of BCNHLs which exhibit an indolent course. These are MALT lymphomas and MZL, particularly the splenic type (SMZL).

None of the lncRNAs has been thus far identified as playing a major role in the the activation or progression of a B-cell to transform in any of these types of B-cell lymphomas.

Concerning miRNAs in SMZL, miR-96, miR-129, miR-29a, miR-29b-1, miR-182, miR-183, miR-335 and miR-593 can be used as diagnostic biomarkers, although without sufficient data to date (174) (Table VI and Fig. 3).

Table VI.

miRNAs identified in patients with splenic marginal zone lymphoma B-cell lymphoma and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma.

| miRNA(s) | Disease type | Genome location | Role/activation | Molecular mechanism/sample | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-29a, miR-29b-1, miR-96, miR-129, miR-182, miR-183, miR-335, miR-593 | Splenic marginal zone lymphoma | Diagnostic biomarkers | Presence in tissues | (174) | |

| miR-127, miR-139, miR-335, miR-411, miR-451, miR-486 | Splenic marginal zone lymphoma | Diagnostic biomarkers | Presence in tissues | (175) | |

| 27-miRNA signature, miR-142, miR-155, miR-203 | Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue | Diagnostic biomarkers | Presence in tissues | (176,177) | |

| miR-142, miR-155 | Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue | Prognostic biomarkers | Presence in tissues | (177) |

miRNA/miR, microRNA.

As regards miRNAs in MALT lymphomas, miR-203 primarily, and secondly, miR-150, miR550, miR-124a, miR-518b and miR-539, have been widely recognizable as being present in gastric MALT lymphoma (175). Other miRNAs identified in MALT lymphomas are the following: The 27-miRNA signature, miR-142, miR-155, miR-203 miR-142 and miR-155 (176,177) (Table VI and Fig. 3).

b) HLs

There are two main types of HL: Classical Hodgkin lymphoma (9 out of 10 cases) and nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (1 out of 10 cases) (178,179). There is a differentiation in morphology, phenotype and molecular features between both these types. Furthermore, classical HL alone can be subclassified into 4 more pathologic subtypes: i) Nodular sclerosing HL; ii) mixed-cellularity subtype; iii) lymphocyte-rich; and iv) lymphocyte-depleted HL (180–182).

Compared to B-NHLs, only limited data are available on the expression of lncRNAs in HLs. As regards miRNAs in patients with HL Hodgkin, there are studies which show that low miR-135a levels lead to significantly poorer prognostic outcome in Hodgkin patients (183,184). The inhibition of let-7 and miR-9 leads to the prevention of plasma cell differentiation (184). In particular, the inhibition of miR-9 seems to lead to a decrease in cytokine production and a reduced ability in attracting inflammatory cells (185). In addition, miR-155, the 23-miRNA signature and 134- and 100-miRNA signature, 25-miRNA signature and miR-9-2 (methylation) can be used as diagnostic biomarkers in patients with HL (as they are presented in HL cell lines and tissues) (186–193) (Table VII and Fig. 3).

Table VII.

miRNAs identified in patients with Hodgkin lymphoma.

| miRNA(s) | Genome location (if defined) | Role/activation | Molecular mechanism/sample | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-155 | Diagnostic biomarkers | Presence in cell lines | (185,186) | |

| 23-miRNA signature, 134-miRNA signature, 100-miRNA signature | Diagnostic biomarkers | Presence in cell lines and tissues | (187,188) | |

| 25-miRNA signature and miR-9-2 (methylation) | Diagnostic biomarkers | Presence in tissues | (189,190) | |

| miR-135a | Prognostic biomarkers | Presence in tissues and cell lines | (191) | |

| miR-21, miR-30e/d, miR-92b, miR-124a (methylation) | Prognostic biomarkers | Presence in tissues | (192,193) |

miRNA/miR, microRNA.

c) T-NHLs and NK-NHLs

T-cell lymphomas affect T-cells and they are divided into 4 major types: i) Extranodal T-cell lymphoma; ii) cutaneous T-cell lymphomas: Sézary syndrome and Mycosis fungoides; iii) anaplastic large cell lymphoma; and iv) angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. There is also a clinical entity known as aggressive NK-cell leukemia with an aggressive, systemic proliferation of NK cells; it can also be termed aggressive NK-cell lymphoma (194,195).

As regards miRNAs in T-cell and NK-cell lymphomas, very little is known so far. MiRNA-21, miRNA-155, miRNA-150, miRNA-142 and miRNA-494 are present in various forms of cutaneous T-cell lymphomas, compared to related benign disorders (196,197). miRNA-146a and miRNA-155 are also present in patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphomas (1). miRNA-223, miRNA-BART-20, miRNA-BART-8, miRNA-BART-16 and miRNA-BART-9 are EBV-encoded and are associated with the activation of the EBV oncoprotein, LMP-1 (197–204) (Table VIII).

Table VIII.

miRNAs and lncRNAs identified in patients with T-cell and NK-cell lymphomas.

| miRNA(s)/lncRNA | Disease type | Genome location (if defined) | Role/activation | Molecular mechanism/sample | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miRNA-21 | NK-cell lymphoma-derived cell lines primary NKTCLs | New biomarker or target in thetreatment of NKTCL. | Regulation of apoptosis of NK-cell lymphoma cell lines via the PTEN/AKT signaling pathway | (199) | |

| miRNA-155 | NK-cell lymphoma cell lines Primary NKTCL specimens | Potential molecular marker of NKTCL | Regulation of inflammation, immune cells, and the differentiation and maturation of tumor cells | (200) | |

| miRNA-142 | Under-expression in NKTCLs lymphomas | Two different forms (miRNA-142-3p and miRNA-412-5p) miRNA-142-3p is a potential target of therapy | Downregulation of RICTOR | (201,202) | |

| miRNA-494 | NKTCLs | Potential target of therapy | Downregulation of PTEN | (202) | |

| miRNA-223 | NKTCLs | EBV infection | Downregulation of PRDM1 | (203) | |

| miRNA-16 | NKTCLs | Novel target in NKTCL treatment | Downregulation of CDKN1A | (197) | |

| miRNA-BART-20 | NKTCLs | EBV-encoded | Maturation of NK-cells | (204) | |

| miRNA-BART-8 | NKTCLs | EBV-encoded | Induction of apoptosis | (204) | |

| miRNA-BART-16 | NKTCLs | EBV-encoded | Induction of cell-cell adhesion | (204) | |

| miRNA-BART-9 | NKTCLs | EBV-encoded | Induction of cell proliferation | (204) | |

| MALAT1 | Various types of T and NK cell lymphomas | 11q13.1 | Overexpression Prognostic marker and therapeutic target in T and NK cell lymphomas. | Induction of BMI1 activation | (195) |

lncRNA, long non-coding RNA; miRNA/miR, microRNA; NKTCL, natural-killer/T cell lymphoma.

Concerning lncRNAs in various types of T-cell and NK-cell lymphomas, MALAT1, located on chromosome 11q13.1, has been identified as being overexpressed and leads to the induction of BMI1 activation (197); that is the reason why MALAT1 can be used as prognostic marker and therapeutic target in T- and NK-cell lymphomas (195) (Table VIII).

d) Other common B-cell malignancies

MM, also known as plasma cell myeloma, is a fatal malignant hematological disorder which lead to the proliferation of monoclonal antibody-secreting plasma cells; the main criterion is the presence of clonal plasma cells >10% in bone marrow biopsy or in a biopsy from other tissues (plasmacytoma). MM accounts for 10% of all hematological malignancies (205).

Compared to all types of B-cell Lymphomas, very little is known about miRNA expression in patients with MM. As regards lncRNAs in patients with MM, the following have been observed (Table IX): i) GAS5, located on chromosome 1q25.1, acting as a tumor-suppressor by regulating the mTOR pathway (77–86); ii) DLEU2, located on chromosome 13q14.3, acting as a tumor-suppressor by being a host of the miR-15a/16-1 cluster and targeting BCL2 (117–120); iii) 3) MALAT1, located on chromosome 11q13, acting as an oncogene by regulating the bioavailability of TGF-β (146–152); iv) MEG3, located on chromosome 14q32.2, acting as a tumor-suppressor by interacting with p53 and regulating p53 gene expression (206–209); v) TUG1, located on chromosome 22q12.2, acting as an oncogene by being induced by p53 (150,152); vi) lnc-SENP5-4/NCBP2-AS2, located on chromosome 3q29, with an uncharacterized mode of action (85); vii) 7) lnc-CPSF2-2, located on chromosome 14q32, with an uncharacterized mode of action (85); viii) lnc-LRRC47-1/TP73-AS1, located on chromosome 1p36, with an uncharacterized mode of action (85); ix) lnc-ANGPTL1-3, located on chromosome 1q25, with an uncharacterized mode of action (85); x) lnc-WHSC2-2, located on chromosome 4p16.3, with an uncharacterized mode of action (85).

Table IX.

lncRNAs identified in patients with multiple myeloma.

| lncRNA | Genome location | Role/activation | Molecular mechanism/sample | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAS5 | 1q25.1 | Tumor-suppressor | Regulation of mTOR pathway | (77–86) |

| DLEU2 | 13q14.3 | Tumor-suppressor | Host of miR-15a/16-1 cluster and targeting BCL2 | (117–120) |

| MALAT1 | 11q13 | Oncogene | Regulation of the bioavailability of TGF-β | (146–152) |

| MEG3 | 14q32.2 | Tumor-suppressor | Interaction with p53. | (206–209) |

| Regulation of P53 gene expression | ||||

| TUG1 | 22q12.2 | Oncogene | Induction by p53 | (150,152) |

| lnc-SENP5-4/NCBP2-AS2 | 3q29 | Uncharacterized | Not described | (85) |

| lnc-CPSF2-2 | 14q32 | Uncharacterized | Not described | (85) |

| lnc-LRRC47-1/TP73-AS1 | 1p36 | Uncharacterized | Not described | (85) |

| lnc-ANGPTL1-3 | 1q25 | Uncharacterized | Not described | (85) |

| lnc-WHSC2-2 | 4p16.3 | Uncharacterized | Not described | (85) |

lncRNA, long non-coding RNA.

4. Anti-ncRNA therapeutic strategies in lymphoid disorders

There are specific strategies that can be used in order to target ncRNAs in tumor management. These are the following: i) Antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), which can trigger RNaseH-mediated RNA degradation (210); ii) CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing technique which can effectively silence the transcription of the lncRNA-expressing loci (211,212); iii) viral vectors (adenovirus, lentivirus and retrovirus) which can be used as a RNA interference (RNAi) method and can lead to the knockdown of gene expression by neutralizing the targeted RNA through exogenous double-stranded RNA insertion (213–215); and iv) nanomedicine, including lipid-based nanoparticles (liposomes) (216), polymer-based nanoparticles and micelles (217), dendrimers (218), carbon-based nanoparticles (219), and metallic and magnetic nanoparticles, such as gold nanoparticles (220,221).

All these novel therapeutic strategies targeting ncRNAs, have been tested to date in preclinical models with lymphoid disorders. For example, a viral vector carrying miR-28 has been delivered in DLBCL and BL xenografts and in murine models with B-lymphoma, with acceptable prophylactic and therapeutic effects (222).

Furthermore, the ASO strategy, such as LNA-anti-miR-155, has been used in a B-cell lymphoma murine model, exhibiting a significant effect in murine models (223). An anti-miR-155 oligonucleotide with the trademark Cobomarsen is currently being clinically nowadays in patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (224).

Double-stranded RNAi and ASOs are the most commonly used lncRNA-targeted therapies. When the target lncRNA is localized in the nucleus, ASOs are the better therapeutic option (225).

The most important finding, by reviewing the literature, is that either the lncRNA expression signature or miRNA expression may help distinguish between the different lymphoma entities. In addition, as certain ncRNAs may be associated with the progression of lymphoma or drug resistance, these ncRNAs can be used as predictive and prognostic markers (225). However, the ncRNA regulatory network is complex and is not yet fully understood, as the majority of ncRNAs have not yet been thoroughly investigated. Nevertheless, ncRNA-based therapeutics can be combined, in the near future, with other techniques, such as chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell immunotherapy, the targeting of tumor cells, thus improving their therapeutic efficacy (226,227).

5. Conclusions and future perspectives

Contemporary developments in biology have been combined with insightful discoveries analyzing the role of ncRNAs, either miRNAs or lncRNAs in human tumors, particularly lymphomas, such as: BCNHLs, HLs, T-cell/NK cell NHLs (T-/NK-cell NHLs) and other B-cell malignancies, such as MM.

The present review aimed to provide a thorough summary of the current understanding of ncRNAs in lymphoid malignancies by summarizing, for the first time, to the best of our knowledge, the whole existing ncRNA (and not into different categories), miRNAs and lncRNAs, which are associated with lymphoid disorders.

The initial data suggest that mostly lncRNAs, play key roles in lymphangiogenesis, as a great number of them are deregulated in B-cell malignancies. However, this particular field is still in its infancy, with insufficient data; thus, further studies need to be performed.

Concerning the role of miRNAs as biomarkers in all lymphoid malignancies, ample data are available, although without immediate use in clinical practice. A number of miRNA biomarker studies to date on B-NHLs, HLs, T-/NK-NHLs and MM are not based on multi-center cooperations, and thus, in most cases, a number of reviews are non-overlapping and even contradictory.

For all the above reasons, further multi-center studies are warranted with the establishment of a standardized approach and the use of the same techniques: RT-qPCR, microarrays or next-generation sequencing (NGS). This is mandatory step in order to explore more thoroughly the role and functions of lncRNAs in normal B-cells and malignant B-cells; as well as to perform a more in-depth miRNA biomarker analysis in order to ensure that these molecules can be effectively used in daily practice. These tasks are both compelling and challenging in the next future for the prognosis and potential therapeutic targeting of all lymphoid malignancies; leading to a better treatment plan.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article, as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Authors' contributions

GD developed, planned, supervised the review and wrote the manuscript. MG created the figure and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. VZ supervised the review, contributed to the writing and revisions of the manuscript. DAS and SA collected relevant literature. VZ and GD confirm the authenticity of all the raw data All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

DAS is the Editor-in-Chief for the journal, but had no personal involvement in the reviewing process, or any influence in terms of adjudicating on the final decision, for this article. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Bardia A, Seifter E. 1st edition. Jones and Bartlett Publishers, Inc.; 2010. Johns Hopkins Patients' Guide to Lymphoma; p. 138. [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Lymphoma Guide, corp-author. Leukemia and Lymphoma Society; New York, USA: 2013. Information for Patients and Caregivers. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. IARC Publications; Lyon, France: 2014. World Cancer Report 2014; pp. 348–528. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, Harris NL, Stein H, Siebert R, Advani R, Ghielmini M, Salles GA, Zelenetz AD, Jaffe ES. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 2016;127:2375–2390. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-01-643569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coiffier B. Monoclonal antibody as therapy for malignant lymphomas. C R Biol. 2006;329:241–254. doi: 10.1016/j.crvi.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:5–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Küppers R, Klein U, Hansmann ML, Rajewsky K. Cellular origin of human B-cell lymphomas. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1520–1529. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199911113412007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Cancer Institute, corp-author. General information about adult Hodgkin Lymphoma. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Cancer Institute, corp-author. General Information about adult Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu L, Luo D, Zhou T, Tao Y, Feng J, Mei S. The association between non-Hodgkin lymphoma and organophosphate pesticides exposure: A meta-analysis. Environ Pollut. 2017;231:319–328. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang L, Dong J, Jiang S, Shi W, Xu X, Huang H, You X, Liu H. Red and processed meat consumption increases risk for Non-Hodgkin lymphoma: A PRISMA-compliant meta-analysis of observational studies. Medicine. 2015;94:e1729. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Solimini AG, Lombardi AM, Palazzo C, De Giusti M. Meat intake and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Cancer Causes Control. 2016;27:595–606. doi: 10.1007/s10552-016-0745-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Cancer Institute, corp-author. Cancer Stat Facts: Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marcus R, Sweetenham J, Williams L, editors. Lymphoma: Pathology, diagnosis and treatment (2nd edition) Cambridge Medicine. 2014:326. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tepper JE, Niederhuber JO, Armitage JH, Doroshow MB, Kastan JE. Chapter. Vol. 97. Elsevier Inc.; 2014. Childhood Lymphoma (5th edition): Abeloff's Clinical Oncology. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamper-Jørgensen M, Rostgaard KG, Zahm SH, Cozen W, Smedby KE, Sanjosé S, Chang ET, Zheng T, La Vecchia C, Serraino D, et al. Cigarette smoking and risk of Hodgkin lymphoma and its subtypes: A pooled analysis from the International Lymphoma Epidemiology Consortium (InterLymph) Ann Oncol. 2013;24:2245–2255. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manli JN, Bennani N, Feldman AL. Lymphoma classification update: T-cell lymphomas, Hodgkin lymphoma, and histiocytic/dendritic cell neoplasms. Expert Rev Hematol. 2017;10:239–249. doi: 10.1080/17474086.2017.1281122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sheikhpour R, Pourhosseini F, Neamatzadeh H, Karimi R. Immunophenotype evaluation of Non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2017;31:121. doi: 10.14196/mjiri.31.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gibb EA, Brown CJ, Lam WL. The functional role of long non-coding RNA in human carcinomas. Mol Cancer. 2011;10:38. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-10-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taft RJ, Pang KC, Mercer TR, Dinger M, Mattick JS. Non-coding RNAs: Regulators of disease. J Pathol. 2010;220:126–139. doi: 10.1002/path.2638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prensner JR, Chinnaiyan AM. The emergence of lncRNAs in cancer biology. Cancer Discov. 2011;1:391–407. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cao Q, Mani RS, Ateeq B, Dhanasekaran SM, Asangani IA, Prensner JR. Coordinated regulation of Polycomb Group Complexes through microRNAs in Cancer. Cancer Cell. 2011;20:187–199. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.He Y, Vogelstein B, Velculescu VE, Papadopoulos N, Kinzler KW. The antisense transcriptomes of human cells. Science. 2008;322:1855–1857. doi: 10.1126/science.1163853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Faulkner GJ, Kimura Y, Daub CO, Wani S, Plessy C, Irvine KM. The regulated retrotransposon transcriptome of mammalian cells. Nat Genet. 2009;41:563–571. doi: 10.1038/ng.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pérez-Vera P, Reyes-León A, Fuentes-Pananá EM. Signaling proteins and transcription factors in normal and malignant early B cell development. Bone Marrow Res. 2011;2011:502751. doi: 10.1155/2011/502751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Walter P. Molecular Biology of the Cell. Garland Science; New York, NY: 2002. p. pg1367. T cells and B cells derive their names from the organs in which they develop. T cells develop in the thymus and B cells, in mammals, develop in the bone marrow in adults or the liver in fetuses. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petri A, Dybkaer K, Bogsted M, Thrue CA, Hagedorn PH, Schmitz A, Bodker JS, Johnsen HE, Kauppinen S. Long noncoding RNA expression during Human B-cell development. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0138236. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herzog S, Reth M, Jumaa H. Regulation of B-cell proliferation and differentiation by pre-B-cell receptor signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:195–205. doi: 10.1038/nri2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Graham LD, Pedersen SK, Brown GS, Ho T, Kassir Z, Moynihan AT, Vizgoft EK, Dunne R, Pimlott L, Young GP, et al. Colorectal Neoplasia differentially expressed (CRNDE), a novel gene with elevated expression in colorectal adenomas and adenocarcinomas. Genes Cancer. 2011;2:829–840. doi: 10.1177/1947601911431081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ellis BC, Molloy PL, Graham LD. CRNDE: A long NonCoding RNA involved in CanceR, neurobiology, and development. Front Genet. 2012;3:270. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2012.00270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ellis BC, Graham LD, Molloy PL. CRNDE, a long noncoding RNA responsive to insulin/IGF signaling, regulates genes involved in central metabolism. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1843:372–386. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen CZ, Li L, Lodish HF, Bartel DP. MicroRNAs modulate hematopoietic lineage differentiation. Science. 2004;303:83–86. doi: 10.1126/science.1091903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Yebenes VG, Belver L, Pisano DG, Gonzalez S, Villasante A, Croce C, He L, Ramiro AR. miR-181b negatively regulates activation-induced cytidine deaminase in B cells. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2199–206. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Teng G, Hakimpour P, Landgraf P, Rice A, Tuschl T, Casellas R, Papavasiliou FN. MicroRNA-155 is a negative regulator of activation-induced cytidine deaminase. Immunity. 2008;28:621–629. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith A, Howell D, Patmore R, Jack A, Roman E. Incidence of haematological malignancy by sub-type: A report from the Haematological malignancy research network. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:1684–1692. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li S, Young KH, Medeiros LJ. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Pathology. 2018;50:74–87. doi: 10.1016/j.pathol.2017.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lenz G, Wright GW, Emre NC, Kohlhammer H, Dave SS, Davis RE, Carty S, Lam LT, Shaffer AL, Xiao W, et al. Molecular subtypes of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma arise by distinct genetic pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:13520–13525. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804295105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sukswai N, Lyapichev K, Khoury JD, Medeiros LJ. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma variants: An update. Pathology. 2019;52:53–67. doi: 10.1016/j.pathol.2019.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shimada K, Hayakawa F, Kiyoi H. Biology and management of primary effusion lymphoma. Blood. 2018;132:1879–1888. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-03-791426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cheng Y, Xiao Y, Zhou R, Liao Y, Zhou J, Ma X. Prognostic significance of Helicobacter pylori-infection in gastric diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:842. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-6067-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kuo SH, Yeh KH, Chen LT, Lin CW, Hsu PN, Hsu C, Wu MS, Tzeng YS, Tsai HJ, Wang HP, Cheng AL. Helicobacter pylori-related diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the stomach: A distinct entity with lower aggressiveness and higher chemosensitivity. Blood Cancer J. 2014;4:e220. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2014.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abramson JS. Hitting back at lymphoma: How do modern diagnostics identify high-risk diffuse large B-cell lymphoma subsets and alter treatment? Cancer. 2019;125:3111–3120. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chavez JC, Locke FL. CAR T cell therapy for B-cell lymphomas. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2018;31:135–146. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2018.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu Y, Barta SK. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: 2019 update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and treatment. Am J Hematol. 2019;94:604–616. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roehle A, Hoefig KP, Repsilber D, Thorns C, Ziepert M, Wesche KO, Thiere M, Loeffler M, Klapper W, Pfreundschuh M, et al. MicroRNA signatures characterize diffuse large B-cell lymphomas and follicular lymphomas. Br J Haematol. 2008;142:732–744. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lawrie CH, Chi J, Taylor S, Tramonti D, Ballabio E, Palazzo S, Saunders NJ, Pezzella F, Boultwood J, Wainscoat JS, Hatton CS. Expression of microRNAs in diffuse large B cell lymphoma is associated with immunophenotype, survival and transformation from follicular lymphoma. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:1248–1260. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00628.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Caramuta S, Lee L, Ozata DM, Akçakaya P, Georgii-Hemming P, Xie H, Amini RM, Lawrie CH, Enblad G, Larsson C, et al. Role of microRNAs and microRNA machinery in the pathogenesis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood Cancer J. 2013;3:e152. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2013.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lawrie CH, Saunders NJ, Soneji S, Palazzo S, Dunlop HM, Cooper CD, Brown PJ, Troussard X, Mossafa H, Enver T, et al. MicroRNA expression in lymphocyte development and malignancy. Leukemia. 2008;22:1440–1446. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2405083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhong H, Xu L, Zhong JH, Xiao F, Liu Q, Huang HH, Chen FY. Clinical and prognostic significance of miR-155 and miR-146a expression levels in formalin-fixed/paraffin-embedded tissue of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Exp Ther Med. 2012;3:763–770. doi: 10.3892/etm.2012.502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chapuy B, Stewart C, Dunford AJ, Kim J, Kamburov A, Redd RA, Lawrence MS, Roemer MGM, Li AJ, Ziepert M, et al. Molecular subtypes of diffuse large B cell lymphoma are associated with distinct pathogenic mechanisms and outcomes. Nat Med. 2018;24:679–690. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0016-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhou K, Feng X, Wang Y, Liu Y, Tian L, Zuo Z, Yi S, Wei X, Song Y, Qiu L. miR-223 is repressed and correlates with inferior clinical features in mantle cell lymphoma through targeting SOX11. Exp Hematol. 2018;58:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2017.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bouteloup M, Verney A, Rachinel N, Callet-Bauchu E, Ffrench M, Coiffier B, Magaud JP, Berger F, Salles GA, Traverse-Glehen A. MicroRNA expression profile in splenic marginal zone lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2012;156:279–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fabbri M, Bottoni A, Shimizu M, Spizzo R, Nicoloso MS, Rossi S, Barbarotto E, Cimmino A, Adair B, Wojcik SE, et al. Association of a microRNA/TP53 feedback circuitry with pathogenesis and outcome of B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. JAMA. 2011;305:59–67. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hanke M, Hoefig K, Merz H, Feller AC, Kausch I, Jocham D, Warnecke JM, Sczakiel G. A robust methodology to study urine microRNA as tumor marker: microRNA-126 and microRNA-182 are related to urinary bladder cancer. Urol Oncol. 2010;28:655–661. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2009.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.He M, Gao L, Zhang S, Tao L, Wang J, Yang J, Zhu M. Prognostic significance of miR-34a and its target proteins of FOXP1, p53, and BCL2 in gastric MALT lymphoma and DLBCL. Gastric Cancer. 2014;17:431–441. doi: 10.1007/s10120-013-0313-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jia YJ, Liu ZB, Wang WG, Sun CB, Wei P, Yang YL, You MJ, Yu BH, Li XQ, Zhou XY. HDAC6 regulates microRNA-27b that suppresses proliferation, promotes apoptosis and target MET in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leukemia. 2017;32:703–711. doi: 10.1038/leu.2017.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gu L, Song G, Chen L, Nie Z, He B, Pan Y, Xu Y, Li R, Gao T, Cho WC, Wang S. Inhibition of miR-21 induces biological and behavioral alterations in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Acta Haematol. 2013;130:87–94. doi: 10.1159/000346441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zheng Z, Li X, Zhu Y, Gu W, Xie X, Jiang J. Prognostic significance of miRNA in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A meta-analysis. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2016;39:1891–1904. doi: 10.1159/000447887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pillar N, Bairey O, Goldschmidt N, Fellig Y, Rosenblat Y, Shehtman I, Haguel D, Raanani P, Shomron N, Siegal T. MicroRNAs as predictors for CNS relapse of systemic diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Oncotarget. 2017;8:86020–86030. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.20902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lawrie CH, Gal S, Dunlop HM, Pushkaran B, Liggins AP, Pulford K, Banham AH, Pezzella F, Boultwood J, Wainscoat JS, et al. Detection of elevated levels of tumourassociated microRNAs in serum of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2008;141:672–675. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bomben R, Gobessi S, Dal Bo M, Volinia M, Marconi D, Tissino E, Benedetti D, Zucchetto A, Rossi D, Gaidano G, et al. The miR-17~92 family regulates the response to Toll-like receptor 9 triggering of CLL cells with unmutated IGHV genes. Leukemia. 2012;26:1584–1593. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Calin GA, Ferracin M, Cimmino A, Di Leva GD, Shimizu M, Wojcik SE, Iorio MV, Visone R, Sever NI, Fabbri M, et al. A microRNA signature associated with prognosis and progression in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1793–1801. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ferrajoli A, Shanafelt TD, Ivan C, Ivan C, Shimizu M, Rabe KG, Nouraee N, Ikuo M, Ghosh AK, Lerner S, et al. Prognostic value of miR-155 in individuals with monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis and patients with B chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2013;122:1891–1899. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-01-478222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Iqbal J, Shen Y, Huang X, Liu Y, Wake L, Liu C, Deffenbacher K, Lachel CM, Wang C, Rohr J, et al. Global microRNA expression profiling uncovers molecular markers for classification and prognosis in aggressive B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2015;125:1137–1145. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-04-566778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ferracin M, Zagatti B, Rizzotto L, Cavazzini F, Veronese A, Ciccone M, Saccenti E, Lupini L, Grilli A, De Angeli C, et al. MicroRNAs involvement in fludarabine refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:123. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Khare D, Goldschmidt N, Bardugo A, Gur-Wahnon D, Ben-Dov IZ, Avni B. Plasma microRNA profiling: Exploring better biomarkers for lymphoma surveillance. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0187722. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0187722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Meng Y, Quan L, Liu A. Identification of key microRNAs associated with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by analyzing serum microRNA expressions. Gene. 2018;642:205–211. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2017.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Song G, Gu L, Li J, Tang Z, Liu H, Chen B, Sun X, He B, Pan Y, Wang S, Cho WC. Serum microRNA expression profiling predict response to R-CHOP treatment in diffuse large B cell lymphoma patients. Ann Hematol. 2014;93:1735–1743. doi: 10.1007/s00277-014-2111-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Leivonen SK, Icay K, Jäntti K, Siren I, Liu C, Alkodsi A, Cervera A, Ludvigsen M, Hamilton-Dutoit SJ, d'Amore F, et al. MicroRNAs regulate key cell survival pathways and mediate chemosensitivity during progression of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood Cancer J. 2017;7:654. doi: 10.1038/s41408-017-0033-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Thompson MA, Edmonds MD, Liang S, McClintock-Treep S, Wang X, Li S, Eischen CM. miR-31 and miR-17-5p levels change during transformation of follicular lymphoma. Human Pathol. 2016;50:118–126. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2015.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Leich E, Zamo A, Horn H, Haralambieva E, Puppe B, Gascoyne RD, Chan WC, Braziel RM, Rimsza LM, Weisenburger DD, et al. MicroRNA profiles of t(14;18)-negative follicular lymphoma support a late germinal center B-cell phenotype. Blood. 2011;118:5550–5558. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-361972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Peng W, Wu J, Feng J. LincRNA-p21 predicts favorable clinical outcome and impairs tumorigenesis in diffuse large B cell lymphoma patients treated with R-CHOP chemotherapy. Clin Exp Med. 2017;17:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s10238-015-0396-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Blume CJ, Hotz-Wagenblatt A, Hullein J, Sellner L, Jethwa A, Stolz T, Slabicki M, Lee K, Sharathchandra A, Benner A, et al. p53-dependent non-coding RNA networks in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2015;29:2015–2023. doi: 10.1038/leu.2015.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Huarte M, Guttman M, Feldser D, Garber M, Koziol MJ, Kenzelmann-Broz D, Khalil AM, Zuk O, Amit I, Rabani M, et al. A large intergenic noncoding RNA induced by p53 mediates global gene repression in the p53 response. Cell. 2010;142:409–419. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yoon JH, Abdelmohsen K, Srikantan S, Yang X, Martindale JL, De S, Huarte M, Zhan M, Becker KG, Gorospe M. LincRNA-p21 suppresses target mRNA translation. Mol Cell. 2012;47:648–655. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Peponi E, Drakos E, Reyes G, Leventaki V, Rassidakis GZ, Medeiros LJ. Activation of mammalian target of rapamycin signaling promotes cell cycle progression and protects cells from apoptosis in mantle cell lymphoma. The Am J Pathol. 2006;169:2171–2180. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mourtada-Maarabouni M, Williams GT. Role of GAS5 noncoding RNA in mediating the effects of rapamycin and its analogues on mantle cell lymphoma cells. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2014;14:468–473. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2014.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Coccia EM, Cicala C, Charlesworth A, Ciccarelli C, Rossi GB, Philipson L, Sorrentino V. Regulation and expression of a growth arrest-specific gene (gas5) during growth, differentiation, and development. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:3514–3521. doi: 10.1128/MCB.12.8.3514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mourtada-Maarabouni M, Pickard MR, Hedge VL, Farzaneh F, Williams GT. GAS5, a non-protein-coding RNA, controls apoptosis and is downregulated in breast cancer. Oncogene. 2009;28:195–208. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nakamura Y, Takahashi N, Kakegawa E, Yoshida K, Ito Y, Kayano H, Niitsu N, Jinnai I, Bessho M. The GAS5 (growth arrest-specific transcript 5) gene fuses to BCL6 as a result of t(1;3)(q25;q27) in a patient with B-cell lymphoma. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2008;182:144–149. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Qiao HP, Gao WS, Huo JX, Yang ZS. Long non-coding RNA GAS5 functions as a tumor suppressor in renal cell carcinoma. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:1077–1082. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2013.14.2.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shi X, Sun M, Liu H, Yao Y, Kong R, Chen F, Song Y. A critical role for the long non-coding RNA GAS5 in proliferation and apoptosis in non-small-cell lung cancer. Mol Carcinog. 2015;54(Suppl 1):E1–E12. doi: 10.1002/mc.22120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Williams GT, Mourtada-Maarabouni M, Farzaneh F. A critical role for non-coding RNA GAS5 in growth arrest and rapamycin inhibition in human T-lymphocytes. Biochem Soc Trans. 2011;39:482–486. doi: 10.1042/BST0390482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mourtada-Maarabouni M, Hasan AM, Farzaneh F, Williams GT. Inhibition of human T-cell proliferation by mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) antagonists requires noncoding RNA growth-arrest-specific transcript 5 (GAS5) Mol Pharmacol. 2010;78:19–28. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.064055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ronchetti D, Agnelli L, Taiana E, Galletti S, Manzoni M, Todoerti K, Musto P, Strozzi F, Neri A. Distinct lncRNA transcriptional fingerprints characterize progressive stages of multiple myeloma. Oncotarget. 2016;7:14814–14830. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kino T, Hurt DE, Ichijo T, Nader N, Chrousos GP. Noncoding RNA gas5 is a growth arrest- and starvationassociated repressor of the glucocorticoid receptor. Sci Signal. 2010;3:ra8. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Conde L, Riby J, Zhang J, Bracci PM, Skibola CF. Copy number variation analysis on a non-Hodgkin lymphoma case-control study identifies an 11q25 duplication associated with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. PLoS One. 2014;9:e105382. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lu Z, Pannunzio NR, Greisman HA, Casero D, Parekh C, Lieber MR. Convergent BCL6 and lncRNA promoters demarcate the major breakpoint region for BCL6 translocations. Blood. 2015;126:1730–1731. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-07-657999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Peng W, Feng J. Long noncoding RNA LUNAR1 associates with cell proliferation and predicts a poor prognosis in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Biomed Pharmacother. 2016;77:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Trimarchi T, Bilal E, Ntziachristos P, Fabbri G, DallaFavera R, Tsirigos A, Aifantis I. Genome-wide mapping and characterization of Notch-regulated long noncoding RNAs in acute leukemia. Cell. 2014;158:593–606. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Peng W, Fan H, Wu G, Wu J, Feng J. Upregulation of long noncoding RNA PEG10 associates with poor prognosis in diffuse large B cell lymphoma with facilitating tumorigenicity. Clin Exp Med. 2016;16:177–182. doi: 10.1007/s10238-015-0350-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ono R, Kobayashi S, Wagatsuma H, Aisaka K, Kohda T, Kaneko-Ishino T, Ishino F. A retrotransposon-derived gene, PEG10, is a novel imprinted gene located on human chromosome 7q21. Genomics. 2001;73:232–237. doi: 10.1006/geno.2001.6494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Li CM, Margolin AA, Salas M, Memeo L, Mansukhani M, Hibshoosh H, Szabolcs M, Klinakis A, Tycko B. PEG10 is a c-MYC target gene in cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:665–672. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Peng W, Wu J, Feng J. Long noncoding RNA HULC predicts poor clinical outcome and represents pro-oncogenic activity in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Biomed Pharmacother. 2016;79:188–193. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hammerle M, Gutschner T, Uckelmann H, Ozgur S, Fiskin E, Gross M, Skawran B, Geffers R, Longerich T, Breuhahn K, et al. Posttranscriptional destabilization of the liver-specific long noncoding RNA HULC by the IGF2 mRNA-binding protein 1 (IGF2BP1) Hepatology. 2013;58:1703–1712. doi: 10.1002/hep.26537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Xie H, Ma H, Zhou D. Plasma HULC as a promising novel biomarker for the detection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:136106. doi: 10.1155/2013/136106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Peng W, Gao W, Feng J. Long noncoding RNA HULC is a novel biomarker of poor prognosis in patients with pancreatic cancer. Med Oncol. 2014;31:346. doi: 10.1007/s12032-014-0346-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yan Y, Han J, Li Z, Yang H, Sui Y, Wang M. Elevated RNA expression of long noncoding HOTAIR promotes cell proliferation and predicts a poor prognosis in patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Mol Med Rep. 2016;13:5125–5131. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.5190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hallek M, Shanafelt TD, Eichhorst B. Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Lancet. 2018;391:1524–1537. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30422-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Tresckow JV, Eichhorst B, Bahlo J, Hallek M. The treatment of chronic lymphatic leukemia. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2019;116:41–46. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2019.0041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Choi SM, O'Malley DP. Diagnostically relevant updates to the WHO classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2018;37:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2018.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Matutes E, Owusu-Ankomah K, Morilla R, Garcia Marco J, Houlihan A, Que TH, Catovsky D. The immunological profile of B-cell disorders and proposal of a scoring system for the diagnosis of CLL. Leukemia. 1994;8:1640–1645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hallek M. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia: Update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and treatment. Am J Hematol. 2017;92:946–965. doi: 10.1002/ajh.24826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Deans JP, Polyak MJ. FMC7 is an epitope of CD20. Blood. 2008;111:2492. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-126243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Palumbo GA, Parrinello N, Fargione G, Cardillo K, Chiarenza A, Berretta S, Conticello C, Villari L, Di Raimondo F. CD200 expression may help in differential diagnosis between mantle cell lymphoma and B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Res. 2009;33:1212–1216. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2009.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Calin GA, Dumitru CD, Shimizu M, Bichi R, Zupo S, Noch E, Aldler H, Rattan S, Keating M, Rai K, et al. Frequent deletions and down-regulation of micro-RNA genes miR15 and miR16 at 13q14 in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:15524–15529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242606799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Sampath D, Liu C, Vasan K, Sulda M, Puduvalli VK, Wierda WG, Keating MJ. Histone deacetylases mediate the silencing of miR-15a, miR-16, and miR-29b in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2012;119:1162–1172. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-05-351510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Rossi S, Shimizu M, Barbarotto E, Nicoloso MS, Dimitri F, Sampath D, Fabbri M, Lerner S, Barron LL, Rassenti LZ, et al. MicroRNA fingerprinting of CLL patients with chromosome 17p deletion identify a miR-21 score that stratifies early survival. Blood. 2010;116:945–952. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-263889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Visone R, Veronese A, Balatti V, Croce CM. MiR-181b: New perspective to evaluate disease progression in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Oncotarget. 2012;3:195–202. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Cui B, Chen L, Zhang S, Mraz M, Fecteau JF, Yu J, Ghia EM, Zhang L, Bao L, Rassenti LZ, et al. MicroRNA-155 influences B-cell receptor signaling and associates with aggressive disease in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2014;124:546–554. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-03-559690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Caivano A, La Rocca F, Simeon V, Girasole M, Dinarelli S, Laurenzana I, De Stradis A, De Luca L, Trino S, Traficante A, et al. MicroRNA-155 in serum-derived extracellular vesicles as a potential biomarker for hematologic malignancies-a short report. Cell Oncol (Dordr) 2017;40:97–103. doi: 10.1007/s13402-016-0300-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Filip AA, Grenda A, Popek S, Koczkodaj D, Wojnowska MM, Budzyński M, Szczepanek EW, Zmorzyński S, Karczmarczyk A, Giannopoulos K. Expression of circulating miRNAs associated with lymphocyte differentiation and activation in CLL-another piece in the puzzle. Ann Hematol. 2017;96:33–50. doi: 10.1007/s00277-016-2840-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Gaidano G, Foà R, Dalla-Favera R. Molecular pathogenesis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:3432–3438. doi: 10.1172/JCI64101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Dohner H, Stilgenbauer S, Benner A, Leupolt E, Krober A, Bullinger L, Dohner K, Bentz M, Lichter P. Genomic aberrations and survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1910–1916. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200012283432602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Cimmino A, Calin GA, Fabbri M, Iorio MV, Ferracin M, Shimizu M, Wojcik SE, Aqeilan RI, Zupo S, Dono M, et al. miR-15 and miR16 induce apoptosis by targetinag BCL2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:13944–13949. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506654102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Fathullahzadeh S, Mirzaei H, Honardoost MA, Sahebkar A, Salehi M. Circulating microRNA-192 as a diagnostic biomarker in human chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer Gene Ther. 2016;23:327–332. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2016.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Klein U, Lia M, Crespo M, Siegel R, Shen Q, Mo T, Ambesi-Impiombato A, Califano A, Migliazza A, Bhagat G, Dalla-Favera R. The DLEU2/miR-15a/16-1 cluster controls B cell proliferation and its deletion leads to chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:28–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Lerner M, Harada M, Loven J, Castro J, Davis Z, Oscier D, Henriksson M, Sangfelt O, Grander D, Corcoran MM. DLEU2, frequently deleted in malignancy, functions as a critical host gene of the cell cycle inhibitory microRNAs miR-15a and miR-16-1. Exp Cell Res. 2009;315:2941–2952. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Garding A, Bhattacharya N, Claus R, Ruppel M, Tschuch C, Filarsky K, Idler I, Zucknick M, Caudron-Herger M, Oakes C, et al. Epigenetic upregulation of lncRNAs at 13q14.3 in leukemia is linked to the In Cis downregulation of a gene cluster that targets NF-kB. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003373. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Baer C, Oakes CC, Ruppert AS. Epigenetic silencing of miR-708 enhances NF-κB signaling in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Int J Cancer. 2015;137:1352–1361. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Clemson CM, Hutchinson JN, Sara SA, Ensminger AW, Fox AH, Chess A, Lawrence JB. An architectural role for a nuclear noncoding RNA: NEAT1 RNA is essential for the structure of paraspeckles. Mol Cell. 2009;33:717–726. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]