Abstract

Chronic inflammation leads to bone loss and fragility. Proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) consistently promote bone resorption. Dietary modulation of proinflammatory cytokines is an accepted therapeutic approach to treat chronic inflammation, including that induced by space-relevant radiation exposure. As such, these studies were designed to determine whether an anti-inflammatory diet, high in omega-3 fatty acids, could reduce radiation-mediated bone damage via reductions in the levels of inflammatory cytokines in osteocytes and serum. Lgr5-EGFP C57BL/6 mice were randomized to receive diets containing fish oil and pectin (FOP; high in omega-3 fatty acids) or corn oil and cellulose (COC; high in omega-6 fatty acids) and then acutely exposed to 0.5-Gy 56Fe or 2.0-Gy gamma-radiation. Mice fed the FOP diet exhibited consistent reductions in serum TNF-α in the 56Fe experiment but not the gamma-experiment. The percentage osteocytes (%Ot) positive for TNF-α increased in gamma-exposed COC, but not FOP, mice. Minimal changes in %Ot positive for sclerostin were observed. FOP mice exhibited modest improvements in several measures of cancellous microarchitecture and volumetric bone mineral density (BMD) postexposure to 56Fe and gamma-radiation. Reduced serum TNF-α in FOP mice exposed to 56Fe was associated with either neutral or modestly positive changes in bone structural integrity. Collectively, these data are generally consistent with previous findings that dietary intake of omega-3 fatty acids may effectively mitigate systemic inflammation after acute radiation exposure and facilitate maintenance of BMD during spaceflight in humans.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY This is the first investigation, to our knowledge, to test the impact of a diet high in omega-3 fatty acids on multiple bone structural and biological outcomes following space-relevant radiation exposure. Novel in biological outcomes is the assessment of osteocyte responses to this stressor. These data also add to the growing evidence that low-dose exposures to even high-energy ion species like 56Fe may have neutral or even small positive impacts on bone.

Keywords: bone, inflammation, sclerostin, space radiation

INTRODUCTION

Exposure to galactic cosmic radiation (GCR) will be an additional hazard faced by future crew members on exploration class missions; thus it is imperative to gain an understanding of the attendant health risks this exposure will generate. Space-relevant radiation exposure leads to a rapid acceleration of osteoclastic bone resorption and some suppression of osteoblastic bone formation, resulting in diminished bone mineral density (BMD), bone strength, and bone microarchitecture. Simulated GCR, the primary radiation in space, via space-relevant doses of 2 Gray (Gy) or less, induces rapid and dramatic loss of cancellous bone (∼15–20%) in rodent models (1–4). Similar bone loss occurs in astronauts following 6 mo on the International Space Station (ISS) with exposure to an average of 0.08 to 0.16 Gy, depending on solar cycles (5–7). However, the skeletal unloading incurred in-flight is proposed to be the major contributor to bone loss (1, 3, 8). As estimated GCR exposure during an exploration class mission to Mars is estimated to be ∼1 Gy, it is critical to ascertain the extent to which GCR will contribute to inflammation and bone loss (6).

Studies centering on the effect of space-relevant radiation on bone predominantly utilize doses >1 Gy and encompass both high- and low-energy radiation types (e.g., protons, gamma, heavy ions like 56Fe). GCR is composed almost entirely of protons (∼99%) with high-energy, high-charge (HZE) ions accounting for the remaining 1% (2). Although only a small fraction of GCR ion species, HZE ions account for 41% of the biological dose equivalent, with 13% from iron (Fe) alone (2). Most accelerator facilities cannot provide a mixed ion beam to precisely imitate GCR; thus each ion species must be simulated independently.

Inflammation is one of the earliest responses of the body to radiation exposure (9), with rodents flown in space showing elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) (10–12). Prior work demonstrates TNF-α expression significantly increases in bone marrow within 24 h and in homogenized cortical bone samples within 3 days after whole body exposure to 2 Gy of gamma-radiation (1). Osteoclast activity is also significantly increased 3 days after exposure to 2 Gy of gamma-radiation (13). Mechanistically, TNF-α is a proinflammatory cytokine that communicates with osteocytes and influences both osteoclasts (14, 15) and osteoblasts (16, 17). TNF-α induces bone resorption by increasing RANKL production (14, 15, 17), stimulating osteoclastogenesis, and inhibiting bone formation via decreased production of osteogenic genes and differentiation factors required for bone formation, such as RUNX2 (18). Increased TNF-α, both systemically and locally in bone, is a key characteristic in several models of inflammatory-mediated bone loss, including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), type 2 diabetes, osteoporosis, and exposure to space-relevant radiation (1, 14, 15).

Osteocytes, derived from mesenchymal stem cells and embedded in mineralized bone matrix, are the most abundant cell type in bone and considered to be the master controllers of bone remodeling (19). Due to their location, osteocytes are positioned to be the primary coordinators of the coupled activity of both osteoclasts and osteoblasts (19). Osteocyte regulation of osteoblasts and osteoclasts occurs in response to a number of stimuli, including circulating proteins and cytokines like TNF-α (19). Osteocytes regulate bone formation via decreases in osteocyte-derived sclerostin expression, a negative regulator of bone formation upregulated by TNF-α (20), while bone resorption is stimulated via increases in the osteocyte-derived RANKL and TNF-α signaling (21). In rodent models of inflammation, TNF-α is increased in both serum and bone and is associated with significant clinical bone loss (22, 23). Currently, little is known regarding the role of osteocytes in the coordinated cellular response to radiation exposure.

Diets rich in omega-3 fatty acids are widely associated with reduced systemic inflammation and are linked with improved health outcomes in chronic inflammatory diseases such as cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, and IBD (24). The health benefits of consuming a diet high in omega-3 fatty acids have been demonstrated in both healthy and disease states and are associated with increased BMD in elderly humans (25, 26) and in C57Bl/6 mice (27). Fish oil, a rich source of omega-3 fatty acids, has been shown to prevent bone loss in ovariectomized rodents by attenuating loss of cancellous bone volume and decreased trabecular number (28–31). Furthermore, astronauts consuming an omega-3-rich diet experience attenuated reductions in BMD during 6-mo missions on the ISS (32).

A potential mechanism to explain these mitigations of bone loss is the reduction in circulating proinflammatory markers (33). A key class of anti-inflammatory mediators derive directly from omega-3 fatty acids (34, 35); thus consumption of omega-3 fatty acids reduces immune cell production of TNF-α and other inflammatory cytokines (36, 37). Omega-3 fatty acids also moderate inflammatory gene expression (38, 39), most notably by blocking nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-κB), a transcription factor upstream of TNF-α (40–42). A diet comprised of 5% fish oil decreased osteoclast number and activity and suppressed gene expression of NF-κB, RANKL, TNF-α, and IL-6 (29). Gene expression of PGE2, a proinflammatory cytokine and downstream target of omega-6 fatty acids, was also suppressed with a 5% fish oil diet versus a diet comprised of 5% corn oil, similar to the diets used in this study (29).

Despite numerous studies examining the effects of GCR on bone, many questions remain to be answered, including the time course of radiation-induced inflammation and the role of osteocytes in the inflammatory response. Furthermore, the capacity for a diet high in omega-3 fatty acids to mitigate the radiation-induced inflammatory response has not been described. Given the well-documented relationship between bone loss and inflammation, we hypothesized that a diet high in omega-3 fatty acids would mitigate radiation-induced bone loss and that this would associate with reduced TNF-α, an inflammatory cytokine, both systemically in serum and locally in bone osteocytes. Our secondary hypothesis was that increased osteocyte TNF-α would associate with increased osteocyte sclerostin, a negative regulator of osteoblast activity.

METHODS

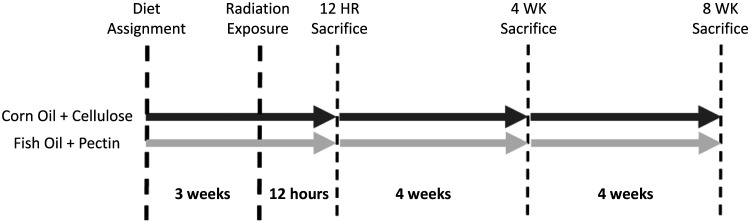

Adult (40.4 ± 7.4 wk) female Lgr5-EGFP C57BL/6 mice were generated in a breeding colony for use in these two experiments. Once mice approached 40 wk of age, they were randomly assigned to corn oil/cellulose (COC) or fish oil/pectin (FOP) diets and then block assigned (n = 4–6/group) to radiation groups to achieve balanced ages and body weights across COC and FOP groups and across gamma (γ)- and iron (56Fe) experiments (Table 1). All mice were acclimated to their new diets for 3 wk before radiation exposure and were maintained on those diets for the duration of the study. Those randomized to be exposed to 56Fe at National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA’s) Space Radiation Laboratory at Brookhaven National Laboratory (BNL; Upton, NY) were acclimated to their new diet for 2 wk and then shipped by overnight air from Texas A&M to the BNL animal facility and allowed 1 additional wk acclimation to the facility before radiation exposure (Fig. 1). Housing conditions (e.g., 12:12-h light-dark cycle and diet) were identical to those at Texas A&M University. Animals in each experiment were terminated 12 h, 4 wk, and 8 wk after irradiation. Animals randomized to the 12-h postexposure group in the 56Fe experiment were terminated at BNL facilities; those assigned to 4- and 8-wk time points were shipped from BNL in New York to Texas A&M via overnight air at least 4 days after radiation exposures and then housed at A&M animal facilities until their scheduled termination. Otherwise, the design of both experiments is identical.

Table 1.

Age and body weights at baseline

| Gamma Experiment |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham COC | Sham FOP | COC + γ | FOP + γ | |

| Age, wk | ||||

| 12 h | 39.46 ± 9.61 | 40.57 ± 11.05 | 40.54 ± 10.93 | 38.91 ± 9.61 |

| 4 wk | 42.17 ± 8.79 | 39.46 ± 7.15 | 39.96 ± 8.56 | 38.54 ± 7.15 |

| 8 wk | 40.39 ± 10.08 | 40.18 ± 9.74 | 39.14 ± 8.67 | 39.00 ± 8.43 |

| Body weight, g | ||||

| 12 h | 35.09 ± 3.65 | 32.91 ± 4.14 | 35.33 ± 6.63 | 33.80 ± 4.90 |

| 4 wk | 33.39 ± 5.10 | 33.33 ± 9.56 | 33.10 ± 7.10 | 34.29 ± 5.74 |

| 8 wk | 34.23 ± 8.71 | 32.34 ± 7.05 | 32.64 ± 7.56 | 30.16 ± 8.66 |

|

56Fe Experiment |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham COC | Sham FOP | COC + 56Fe | FOP + 56Fe | |

| Age, wk | ||||

| 12 h | 41.11 ± 4.52 | 39.64 ± 8.61 | 39.57 ± 8.30 | 39.43 ± 7.08 |

| 4 wk | 40.18 ± 2.87 | 40.79 ± 7.49 | 41.43 ± 7.73 | 39.71 ± 7.73 |

| 8 wk | 40.71 ± 6.87 | 38.61 ± 5.37 | 44.38 ± 7.00 | 42.60 ± 7.09 |

| Body weight, g | ||||

| 12 h | 26.98 ± 1.50 | 29.65 ± 3.53 | 29.23 ± 4.88 | 27.33 ± 4.56 |

| 4 wk | 26.73 ± 3.72 | 29.25 ± 4.81 | 29.83 ± 0.98 | 30.30 ± 5.20 |

| 8 wk | 30.36 ± 0.97 | 29.50 ± 6.07 | 29.10 ± 5.33 | 32.08 ± 8.60 |

Data are presented as means ± SD. Age (wk) and body weight (g) at baseline (day of irradiation) by group assignment are shown. COC, corn oil/cellulose; FOP, fish oil/pectin. N/group = 4–6. There were no statistical differences, assessed via two-way ANOVA, among groups for age or body weight within γ- and 56Fe experiments.

Figure 1.

Experimental timeline.

At each termination time point, animals were euthanized using carbon dioxide inhalation followed by cervical dislocation. Whole blood was collected via cardiac puncture after thoracotomy; left and right femora and tibiae were collected and stored appropriately for analyses, as described below. Animals terminated at 12 h were assessed only for serum TNF-α and localization of sclerostin and TNF-α in osteocytes by immunohistochemistry. Long bones from animals terminated at 4 and 8 wk after irradiation were additionally assessed for static histomorphometry measures of osteoblast and osteoclast activity and microcomputed tomography assessment of bone architecture, geometry, and volumetric bone mineral density (vBMD). All specimens within an analysis were assessed by one technician. Specimens were analyzed in a random order and the technician was blinded during the outcome assessment.

Animal Model

A breeding colony of Lgr5-EGFP-IRES-cre ERT2 knockin transgenic mice utilizing a C57BL/6 background was established at Texas A&M University with founder heterogeneous males and wild-type females. Breeder colony mice were maintained on 9% or 4% protein chow for breeders or maintenance, respectively. Mice were weaned and separated by sex at 21 days of age, and genotype status was determined via tail snip DNA. Transgenic mice were maintained on 4% protein chow until study onset. The Lgr5-EGFP-IRES-cre ERT2 mouse harbors a Lgr5-EGFP fluorescent tag and the potential for inducible loss-of-function through deletion of Lgr5, the latter of which was not performed in this study ensuring full functioning of Lgr5 in all animals used. Lgr5-EGFP C57BL/6 mice were required for the specific aims of the parent study for fluorescence-based analysis of stem cells in the gut epithelium postirradiation. Although no study has looked into the potential side effects of fluorescently labeled Lgr5 on bone, control Lgr5-EGFP C57Bl/6 mice in our study had a bone phenotype consistent with that of female, aged-matched wild-type C57Bl/6 mice (43). Wild-type C57BL/6 mice have been extensively used as a model for radiation-induced bone loss in humans (3). The majority of radiation studies published to date investigate the impact in male mice (1, 8, 44–46). As the number of female astronauts grow, it is imperative to assess the expected biological impact of radiation to bone; thus female mice were selected for this study.

This study was approved and followed all procedures set by the Texas A&M University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, as well as the BNL Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Brookhaven National Laboratory. All animals were housed up to five mice per cage after group assignment with 12-h light-dark cycles.

Diet

Animals were randomly assigned to an ad libitum diet: a corn oil and cellulose (COC) diet consisting of 6% cellulose and 5% corn oil, or a fish oil and pectin (FOP) diet consisting of 6% pectin, 4% fish oil, and 1% corn oil, with all other ingredients maintained across diets (Table 2). The COC diet is used to simulate a diet high in omega-6 fatty acids (similar to the average US citizen’s diet), while the FOP diet is rich in omega-3 fatty acids.

Table 2.

Experimental diet composition

| Ingredient | COC | FOP |

|---|---|---|

| Sucrose | 42.0% | 42.0% |

| Casein | 20.0% | 20.0% |

| Corn starch | 22.0% | 22.0% |

| AIN-76A salt mix | 3.5% | 3.5% |

| AIN-76A vitamin mix | 1.0% | 1.0% |

| dl-methionine | 0.3% | 0.3% |

| Choline chloride | 0.2% | 0.2% |

| Corn oil | 5.0% | 1.0% |

| Cellulose | 6.0% | 0.0% |

| Fish oil | 0.0% | 4.0% |

| Pectin | 0.0% | 6.0% |

Comparison of experimental diet composition (percent by weight). Diets differ in fiber and lipid sources. COC, corn oil/cellulose; FOP, fish oil/pectin.

Radiation Exposure

Animals were randomized within experiments to receive whole body exposures to high-energy 56Fe ionizing radiation (0.5 Gy of 1,000 MeV/n at 25 cGy/min) at BNL’s NASA Space Radiation Laboratory or to a biologically equivalent dose of gamma-radiation (2.0 Gy of γ at 25 cGy/min at Texas A&M University Nuclear Science Center) or to nonirradiated controls (sham). Animals exposed to radiation were restrained unanesthetized in plastic 50-mL conical centrifuge tubes for no more than 4 min. Sham-exposed animals were included at both locations and treated identically to irradiated animals but not subjected to tube restraint or radiation exposure.

Microcomputed Tomography of Bone Microarchitecture and Geometry

Microcomputed tomography (μCT) was performed at the distal metaphysis and middiaphysis of the right femur using a high-resolution imaging system (μCT 50, ScanCo, Bruttisellen, Switzerland) to assess bone geometry, density, and microarchitecture. Femora were fixed in 4% phosphate-buffered formalin and subsequently stored in 70% ethanol at 4°C until immediately before scanning. Distal and middiaphyseal femoral regions were scanned at 9-μm isotropic voxel size using 55 kVp, 114 mA, and 200 ms. Cancellous bone parameters analyzed included bone volume fraction (BV/TV; %), trabecular thickness (Tb.Th; mm), trabecular number (Tb.N; 1/mm), trabecular separation (Tb.Sp; mm), connectivity density (Conn.D; 1/mm3), and volumetric bone mineral density (vBMD; g/cm3). Analysis of cancellous bone regions was performed using a semiautomated contouring program that separated cancellous from cortical bone. The region started 0.5 mm proximal from the distal epiphyseal growth plate and extended 1.7 mm further in the proximal direction. Cortical bone was assessed in a 1 mm-long region centered at the middiaphysis. Cortical bone parameters analyzed included cortical area (Ct.Ar; mm2), cortical thickness (Ct.Th; mm), total area (Tt.Ar; mm2), and medullary area (Ma.Ar; mm2). Bone was segmented from soft tissue using the same threshold for all groups: 245 mg HA/cm3 for cancellous and 682 mg HA/cm3 for cortical bone. Due to technical difficulties, we calculated cortical area by subtracting the scanner-reported medullary area from total area and report this variable as Ct.Arcalc. Scan acquisition and all analyses were conducted by one technician in accordance with established guidelines for use of μCT in rodents (47).

Static Histomorphometry of Relative Osteoid and Osteoclast Surface

Static histomorphometry was performed at the distal femoral metaphysis to assess relative osteoid and osteoclast surfaces. Distal femora were fixed in 4% phosphate-buffered formalin for 24 h and subsequently stored in 70% ethanol at 4°C. Femora were then subjected to serial dehydration and embedded in methyl methacrylate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Samples were sectioned on a Leica microtome (RM 2255, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) to ∼5 μm thickness, mounted on gelatinized slides, and baked for ∼48 h at 37°C. Slides were subsequently treated with von Kossa stain and tetrachrome counterstain to measure osteoid (OS/BS; %) and osteoclast surfaces (Oc.S/BS; %) relative to total cancellous surface. Histomorphometric analyses were performed using OsteoMeasure Analysis System, version 3.3 (OsteoMetrics, Inc., Decatur, GA) interfaced with a light microscope and CCD camera (DP73, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). A defined region of interest was established, starting ∼500 μm from the growth plate and within an area of ∼4 mm2 at a magnification of ×400 within the endocortical borders. Osteoid and osteoclast-covered surfaces were visually identified and quantified manually. All procedures and terminology follow standard guidelines previously published (48).

Immunohistochemical Staining of Osteocytes for Sclerostin and TNF-α

Femora were collected from animals at termination, fixed in 4% phosphate-buffered formalin for 24 h, and subsequently stored in 70% ethanol at 4°C. Bones were then decalcified in a sodium citrate/formic acid solution for ∼12 days before dehydration and processing using a Thermo-Scientific STP 120 Spin Tissue Processor and were paraffinized via a Thermo Shandon Histocenter 3 Embedding tool. Longitudinal sections of the femur were cut on a Leica microtome (RM2125, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) to ∼5-μm thickness, mounted on positively charged slides, and baked overnight at 37°C. Slides were later stained for proteins of interest using an avidin-biotin method. Briefly, heat-mediated antigen retrieval was performed when specified by manufacturer instructions using 1% triton in phosphate-buffered saline. Samples were rehydrated, peroxidase inactivated using 3% H2O2/methanol, permeabilized using 0.5% Triton-X 100 in phosphate-buffered saline, blocked with species-appropriate serum for 30 min at room temperature (Vectastain Elite ABC; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), and incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies: polyclonal rabbit anti-TNF-α (1:200; ab6671, research resource identifier: AB 305641; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) or polyclonal goat anti-SOST/Sclerostin (1:150; AF1589, research resource identifier: AB 2195345; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Sections were incubated at room temperature for 45 minutes with species-appropriate biotinylated anti-IgG secondary antibody. Peroxidase development was performed with an enzyme substrate kit (diaminobenzidine [DAB]; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Counterstaining was conducted with methyl green counterstain (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 2.5 min. Sections were then dehydrated into organic phase and mounted with xylene-based mounting media (Polysciences, Warrington, PA). Antibodies for TNF-α (49) and sclerostin/SOST (50) were previously validated in bone specimens and identified using an online repository and artificial intelligence assisted antibody selection tool (BenchSci, Ontario, Canada). Negative controls for all antibodies were completed by omitting only the primary antibody before analysis. Quantification of immunohistochemical analyses was performed using OsteoMeasure Analysis System, version 3.3 (OsteoMetrics, Inc., Decatur, GA) interfaced with a light microscope and CCD camera (DP73, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The proportion of all osteocytes stained positively for the protein of interest was quantified in metaphyseal cancellous bone, starting ∼500 μm from the growth plate within an area of ∼4 mm2 within the endocortical surfaces, and in cortical bone at middiaphysis, within an area of ∼1 mm2 per slide, at a magnification of ×400.

Serum Analysis of TNF-α

Immediately following collection at termination, whole blood was centrifuged at 4°C at 1,500 g for 15 minutes and serum was separated and stored at –80°C until analysis. Serum TNF-α was measured in a quantitative immunoassay ELISA (MTA00B; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) for all time points. Calculation of results was carried out according to manufacturer’s guidelines. Serum TNF-α was assessed across all termination time points. Two of the 203 samples run in duplicate met exclusion criteria with a coefficient of variation (CV) (computed using samples in duplicate) greater than 20%. The intra-assay CV was 4.72%, and the interassay CV was 12.89%.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed on all outcome measures using a two-way ANOVA (factors = diet, radiation) within each time point for each radiation type. Due to the low number per group, post hoc analysis could not be assessed. As such, significant differences between groups were assessed via t-tests within diet (e.g., COC sham vs. irradiated) and radiation (e.g., COC sham versus FOP sham) matched controls. Statistical significance reported in figures and tables, as well as in-text references to main effects and interactions, derives from results of ANOVAs. Statistical significance reported in-text referencing between group differences reflects results of unpaired t tests. Data were assessed for normality and outliers were excluded before ANOVAs were performed; outliers were defined as any value >2.5 SD above the mean within that group. The number of outliers was reasonably consistent across groups in 13 of the 16 outcome variables, with no more than 3 outliers per variable found per 70 total samples (4- and 8-wk analyses) and no more than 6 outliers found per 105 total samples (for variables assessed at all time points). An alpha-level of 0.10 was set a priori for all statistical analyses to achieve sufficient power (β = 0.80) with an n of 4–6 per group. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics software (IBM, Armonk, NY).

RESULTS

Cancellous Microarchitecture and Cortical Geometry

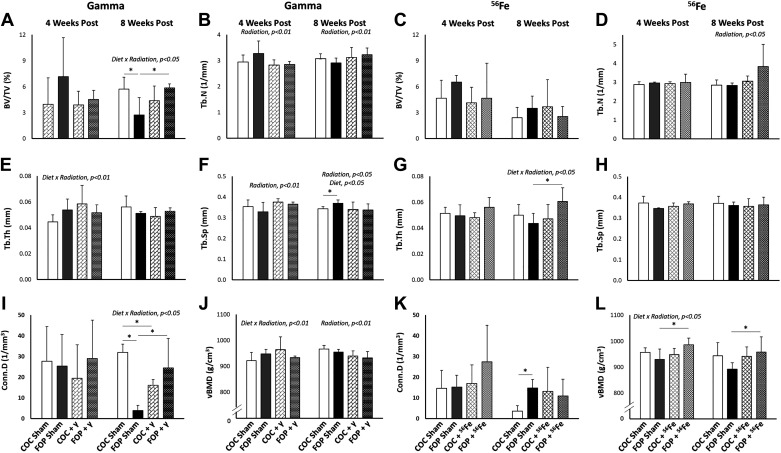

Gamma experiment.

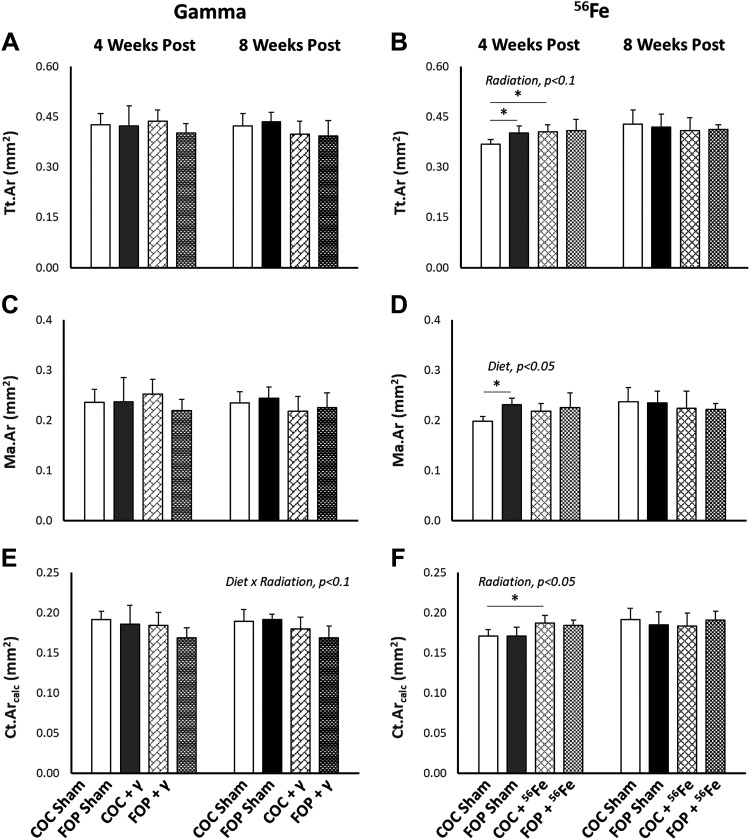

Four weeks after exposure to γ-radiation, a significant main effect of radiation was found for Tb.N (P = 0.081) and Tb.Th (P = 0.054), where 2.0 Gy γ-radiation significantly reduced Tb.N and increased Tb.Sp in both diet groups (Fig. 2). After 8 wk, there remained significant main effects of radiation on Tb.N (P = 0.082) and Tb.Sp (P = 0.029) but the directional impact reversed, with a small increase in Tb.N and small decrease in Tb.Sp in irradiated mice. No significant main effect of radiation was detected on distal femur cancellous BV/TV or Conn.D or on any aspect of cortical bone geometry at the femoral mid-diaphysis (Fig. 3). The only significant effect of diet detected was for Tb.Sp (P = 0.029) at 8 wk after exposure; sham-exposed FOP mice had significantly higher Tb.Sp than did COC-fed shams (P = 0.06).

Figure 2.

Microarchitecture of cancellous bone (assessed by microcomputed tomography) at the distal femoral metaphysis 4 and 8 wk after whole body exposure to 2-Gy γ-radiation or 0.5-Gy 56Fe radiation. A and C: bone volume fraction (BV/TV). B and D: trabecular number (Tb.N). E and G: trabecular thickness (Tb.Th). F and H: trabecular separation (Tb.Sp). I and K: connectivity density (Conn.D). J and L: volumetric bone mineral density (vBMD). FOP, fish oil and pectin; COC, corn oil and cellulose. N/group = 4–6. Results are expressed as means ± SD; data were assessed via two-way ANOVA with P value for significant main effects or interactions listed; significant between group comparisons assessed via t test are identified with a black horizontal line, *P < 0.1.

Figure 3.

Geometry of cortical bone (assessed by microcomputed tomography) at the femoral diaphysis 4 and 8 wk after whole body exposure to 2-Gy γ-radiation or 0.5-Gy 56Fe radiation. A and B: total area of the cortical cross section (Tt.Ar). C and D: marrow area (Ma.Ar). E and F: Ct.Arcalc, calculated cortical bone area. FOP, fish oil and pectin; COC, corn oil and cellulose. N/group = 4–6. Results are expressed as means ± SD; data were assessed via two-way ANOVA with P value for significant main effects or interactions listed; significant between group comparisons assessed via t test are identified with a black horizontal line. *P < 0.1.

Significant diet × radiation interactions were found at 8 wk postexposure for metaphyseal BV/TV (P = 0.036) and Conn.D (P = 0.009), as well as for diaphyseal Ct.Ar (P = 0.064). Significant differences were detected between sham-exposed diet groups for BV/TV (P = 0.089) and Conn.D (P = 0.001), with FOP-fed sham-exposed mice exhibiting two and eightfold lower values, respectively, versus COC-fed sham-exposed mice. Interestingly, 2.0 Gy of γ-radiation led to significantly higher values for BV/TV (P = 0.056) and Conn.D (P = 0.065) in FOP mice, while COC-fed mice exhibited no impact of radiation exposure on BV/TV and a significant decrease in Conn.D (P = 0.007) versus COC shams. Group means for diaphyseal Ct.Ar at 8 wk suggest a slightly larger impact of γ-radiation on reducing Ct.Ar in FOP-fed versus COC-fed mice. A significant diet × radiation interaction was also detected for Tb.Th (P = 0.091) at the earlier 4-wk time point, such that FOP-fed mice exhibited no changes in these outcomes with 2.0 Gy of γ-radiation, while irradiated COC-fed mice exhibited the highest Tb.Th mean values.

Volumetric bone mineral density (vBMD) of the distal femur cancellous compartment provides another measure of cancellous bone mass. A significant effect of radiation was detected for vBMD (P = 0.052) at 8 wk after γ radiation, where vBMD was lower across both diet groups. A significant diet × radiation interaction was detected for vBMD (P = 0.086) at the earlier 4-wk time point, where the small increase in vBMD observed in COC-fed mice postradiation was not observed in FOP-fed mice.

Iron experiment.

A significant main effect of radiation was detected for only Tb.N (P = 0.042) among cancellous bone outcomes, where mice exposed to 0.5 Gy 56Fe had higher Tb.N than sham mice across both diets at 8 wk postexposure (Fig. 2). In cortical bone, significant effects of radiation were found for diaphyseal Ct.Ar (P = 0.008) and Tt.Ar (P = 0.082), where 0.5 Gy of 56Fe radiation led to higher values of Ct.Ar and Tt.Ar (Fig. 3) at 4 wk postexposure; however, within-diet comparisons were significant only for COC-fed mice. FOP-fed shams exhibited greater Tt.Ar than COC-fed shams (P = 0.067). The only significant main effect of diet was noted for diaphyseal Ma.Ar (P = 0.049) at 4 wk (Fig. 4D); sham FOP-fed mice had greater Ma.Ar than sham COC-fed mice (P = 0.024). These differences were not observed at 8 wk. There was a significant diet × radiation interaction (P = 0.047) for Tb.Th at 8 wk, such that irradiation led to significantly greater Tb.Th in FOP mice (P = 0.061), while COC-fed mice showed no apparent impact.

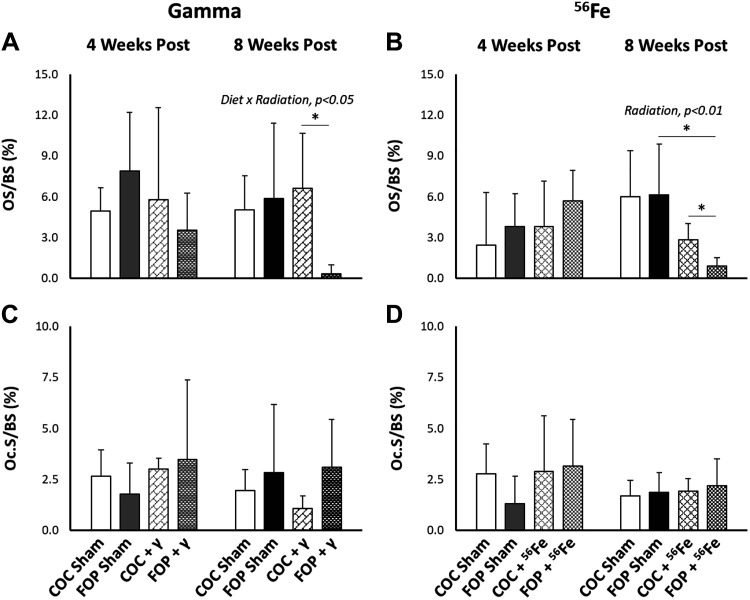

Figure 4.

Osteoid (OS/BS; A and B) and osteoclast surfaces (Oc.S/BS; C and D) relative to bone surface in cancellous bone at the distal femoral metaphysis at 4 and 8 wk postexposure to 2-Gy γ-radiation or 0.5-Gy 56Fe radiation. FOP, fish oil and pectin; COC, corn oil and cellulose. N/group = 4–6. Results are expressed as means ± SD; data were assessed via two-way ANOVA with P value for significant main effects or interactions listed; significant between group comparisons assessed via t test are identified with a black horizontal line. *P < 0.1.

A significant diet × radiation interaction was detected for cancellous vBMD (P = 0.041) at 4 wk after exposure to 0.5 Gy of 56Fe radiation, such that irradiated FOP-fed mice exhibited higher vBMD with COC-fed mice exhibiting no change with irradiation (P = 0.098). At 8 wk, cancellous vBMD was no longer significantly different due to diet or radiation, although irradiated FOP mice maintained significantly higher vBMD versus sham FOP mice (P = 0.088).

Relative Osteoid and Osteoclast Surfaces

Gamma experiment.

No significant main effects of radiation or diet were detected in relative osteoid surface (OS/BS, %) or relative osteoclast surface (Oc.S/BS; %) at 4- or 8 wk post exposure to γ radiation (Fig. 4, A and C). At 8 wk, a significant interaction of diet × radiation (P = 0.053) was found in OS/BS such that OS/BS in COC-fed mice was unchanged by irradiation, while OS/BS was significantly reduced in FOP mice exposed to 2.0 Gy of γ-radiation (P = 0.055).

Iron experiment.

A significant main effect of radiation (P = 0.002) was found in %OS/BS at 8 wk, with significantly lower values observed in both COC (P = 0.04) and FOP (P = 0.071) mice exposed to 0.5 Gy of 56Fe versus within-diet sham controls (Fig. 4B). No impact of diet was observed on either %OS/BS or %Oc.S/BS at either time point. No significant interactions of radiation and diet were detected for %OS/BS nor for %Oc.S/BS at 4 and 8 wk postexposure to 56Fe.

Serum TNF-α

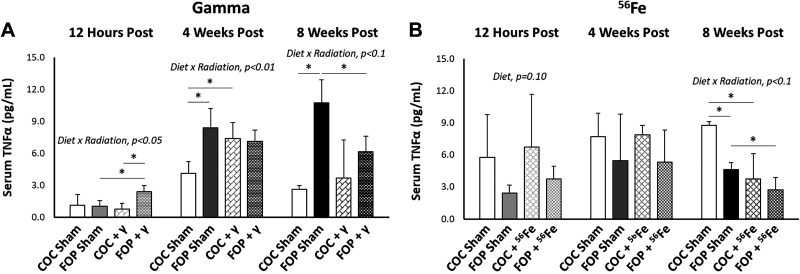

Gamma experiment.

A significant interaction of diet × radiation was found in mice exposed to 2.0 Gy of γ radiation (Fig. 5) at 12 h (P = 0.026), 4 wk (P = 0.004), and 8 wk (P = 0.077). At 12 h, irradiation in FOP mice led to increases in serum TNF-α versus sham FOP mice (P = 0.036), while serum TNF-α in COC-fed mice was unchanged by irradiation. Sham FOP-fed mice had significantly higher serum TNF-α than sham COC mice (P = 0.023). At 4 wk, serum TNF-α was significantly greater in irradiated COC mice (P = 0.033), while radiation had no significant impact in FOP mice. At 8 wk, sham FOP mice exhibited nearly fourfold higher serum TNF-α versus sham COC mice (P = 0.005). While COC-fed mice exhibited no apparent impact of irradiation, serum TNF-α was reduced by nearly half in irradiated FOP-mice versus sham FOP (P = 0.039).

Figure 5.

Serum TNF-α concentrations (pg/mL) at 12 h, 4 wk, and 8 wk postexposure to 2-Gy γ or 0.5-Gy 56Fe radiation. FOP, fish oil and pectin; COC, corn oil and cellulose. N/group = 4–6. Results are expressed as mean ± SD; data assessed via two-way ANOVA with P value for significant main effects or interactions listed; significant between group comparisons assessed via t test are identified with a black horizontal line. *P < 0.1.

Iron experiment.

A significant effect of diet was detected (P = 0.10) at 12 h postexposure to 56Fe, such that the FOP diet resulted in lower levels of serum TNF-α than the COC diet, irrespective of radiation exposure (Fig. 5). At 8 wk, a significant interaction of diet × radiation was found for serum TNF-α (P = 0.085), where sham FOP mice had significantly lower serum TNF-α than sham COC mice (P = 0.007), but irradiated diet groups were not different. Interestingly, irradiation led to significantly lower serum TNF-α in both COC (P = 0.021) and FOP (P = 0.043) mice compared to within-diet sham controls.

Immunohistochemistry Localization of TNF-α and Sclerostin in Osteocytes

TNF-α.

Gamma-experiment.

No significant main effects of radiation or diet or significant interactions were detected in the percentage of cancellous bone osteocytes staining positive for TNF-α (% + Ot-TNF-α) after exposure to γ-radiation (Table 3). For cortical bone %+Ot-TNF-α, no main effects of radiation or diet were observed. A significant interaction of diet × radiation was detected in % + Ot-TNF-α in diaphyseal cortical bone at 12 h (P = 0.018) and 4 wk (P = 0.033) postirradiation. At 12 h, FOP-fed mice did not exhibit a significant increase in % + Ot-TNF-α as did COC-fed mice (P = 0.04). Notably, at 12 h postirradiation, FOP mice exposed to γ-radiation exhibited significantly lower % + Ot-TNF-α than did COC mice (P = 0.058). At 4 wk, irradiated FOP-fed mice exhibited significantly lower % + Ot-TNF-α versus sham FOP mice (P = 0.088) and versus irradiated COC mice (P = 0.083), whereas there was no change postirradiation in COC-fed mice.

Table 3.

Percentage of osteocytes staining positive for TNF-α

| Gamma Experiment |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham COC | Sham FOP | COC + γ | FOP + γ | ANOVA | |||

| Cancellous | Diet | Radiation | Diet × radiation | ||||

| 12 h | 63.73 ± 11.30 | 66.09 ± 14.67 | 72.96 ± 15.17 | 60.37 ± 7.64 | |||

| 4 wk | 18.84 ± 4.92 | 16.39 ± 3.76 | 15.43 ± 10.65 | 11.94 ± 5.98 | |||

| 8 wk | 24.95 ± 1.69 | 23.09 ± 9.36 | 23.12 ± 9.83 | 33.33 ± 8.02 | |||

| Cortical | |||||||

| 12 h | 40.49 ± 13.72 | 60.54 ± 19.57 | 62.81 ± 3.81* | 39.67 ± 16.82† | P = 0.018 | ||

| 4 wk | 15.53 ± 4.53 | 19.02 ± 4.50 | 18.66 ± 3.95 | 12.10 ± 3.27*† | P = 0.033 | ||

| 8 wk | 22.49 ± 5.18 | 21.20 ± 4.83 | 18.55 ± 5.68 | 18.78 ± 5.36 | |||

|

56Fe Experiment |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham COC | Sham FOP | COC + 56Fe | FOP + 56Fe | ANOVA | |||

| Cancellous | Diet | Radiation | Diet × radiation | ||||

| 12 h | 62.57 ± 4.74 | 63.45 ± 27.89 | 49.55 ± 13.97 | 61.03 ± 5.68 | |||

| 4 wk | 54.58 ± 12.72 | 37.09 ± 17.80 | 58.96 ± 13.08 | 53.52 ± 23.99 | |||

| 8 wk | 45.42 ± 18.05 | 33.73 ± 7.93 | 39.11 ± 9.65 | 38.60 ± 7.34 | |||

| Cortical | |||||||

| 12 h | 24.63 ± 3.50 | 45.91 ± 7.24 | 34.79 ± 13.61 | 25.12 ± 5.31 | |||

| 4 wk | 37.08 ± 12.30 | 29.46 ± 9.18 | 34.44 ± 7.45 | 39.77 ± 11.13 | |||

| 8 wk | 27.71 ± 14.82 | 20.55 ± 1.96 | 20.29 ± 8.08 | 22.84 ± 13.73 | |||

Data are expressed as means ± SD. Percentage of osteocytes staining positive for TNF-α in metaphyseal cancellous and diaphyseal cortical bone at 12 h, 4 wk, and 8 wk postexposure to 2 Gy γ or 0.5 Gy 56Fe radiation. COC, corn oil/cellulose; FOP, fish oil/pectin. N/group = 3–6. Data were assessed via two-way ANOVA with between group comparisons assessed via t test; *vs. within diet sham, †vs. COC-matched treatment.

Iron experiment.

No significant main effects of radiation or diet or significant interactions were detected in % + Ot-TNF-α in cancellous or cortical bone at any timepoint following exposure to 56Fe (Table 3).

Sclerostin.

Gamma-experiment.

No significant main effects of radiation or diet or significant interactions were detected in the percentage of osteocytes staining positive for sclerostin (% + Ot-Scl), a negative regulator of bone formation upregulated by TNF-α, in either cancellous or cortical bone at any time point following exposure to 2.0 Gy of γ-radiation (Table 4).

Table 4.

Percentage of osteocytes staining positive for sclerostin

| Gamma Experiment |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham COC | Sham FOP | COC + γ | FOP + γ | ANOVA | |||

| Cancellous | Diet | Radiation | Diet × radiation | ||||

| 12 h | 75.34 ± 11.93 | 74.92 ± 4.29 | 74.77 ± 13.37 | 78.82 ± 7.41 | |||

| 4 wk | 45.49 ± 10.83 | 32.33 ± 19.80 | 28.55 ± 3.54 | 31.88 ± 17.32 | |||

| 8 wk | 25.69 ± 2.77 | 28.62 ± 10.41 | 28.86 ± 15.46 | 27.40 ± 7.67 | |||

| Cortical | |||||||

| 12 h | 86.97 ± 5.71 | 85.60 ± 2.17 | 84.48 ± 10.61 | 87.53 ± 1.89 | |||

| 4 wk | 58.39 ± 9.58 | 57.92 ± 1.80 | 47.20 ± 15.74 | 51.90 ± 4.65 | |||

| 8 wk | 45.50 ± 9.27 | 48.41 ± 4.15 | 46.80 ± 11.30 | 45.79 ± 8.01 | |||

|

56Fe Experiment |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham COC | Sham FOP | COC + 56Fe | FOP + 56Fe | ||||

| Cancellous | Diet | Radiation | Diet × radiation | ||||

| 12 h | 81.75 ± 11.98 | 64.04 ± 13.35 | 74.45 ± 13.44 | 69.23 ± 23.18 | |||

| 4 wk | 72.40 ± 13.43 | 70.25 ± 11.94 | 73.85 ± 12.65 | 56.33 ± 4.27 | |||

| 8 wk | 53.33 ± 1.41 | 72.17 ± 1.75 | 75.68 ± 10.63 | 61.94 ± 21.67 | |||

| Cortical | |||||||

| 12 h | 69.77 ± 16.85 | 69.73 ± 3.23 | 60.99 ± 6.43 | 70.84 ± 3.72 | |||

| 4 wk | 84.24 ± 10.75 | 85.98 ± 5.79 | 80.58 ± 11.20 | 74.40 ± 2.64* | P = 0.094 | ||

| 8 wk | 73.16 ± 28.04 | 77.84 ± 13.49 | 89.42 ± 5.56 | 86.87 ± 10.88 | P = 0.014 | P = 0.09 | |

Data are expressed as means ± SD. Percentage of osteocytes staining positive for sclerostin in metaphyseal cancellous and diaphyseal cortical bone at 12 h, 4 wk, and 8 wk postexposure to 2-Gy γ-radiation or 0.5-Gy 56Fe radiation. COC, corn oil/cellulose; FOP, fish oil/pectin. N/group = 3–6. Data were assessed via two-way ANOVA with between group comparisons assessed via t test; *vs. within diet sham.

Iron experiment.

No significant main effects of radiation or diet or significant interactions were found in cancellous bone % + Ot-Scl at any time point after exposure to 0.5 Gy 56Fe (Table 4). In midfemur cortical bone, there was a significant main effect of radiation detected for % + Ot-Scl at 4 wk (P = 0.094) and a significant diet × radiation interaction (P = 0.09) at 8 wk after 56Fe exposure. Mean values for cortical %+Ot-Scl were lower at 4 wk after 56Fe exposure (FOP sham vs. irradiated FOP; P = 0.036) but numerically higher at 8 wk postirradiation for both diet groups. No effect of diet was found for cortical bone % + Ot-Scl at any time point. Although differences between groups at this time point were not significant, the FOP diet resulted in slightly higher % + Ot-Scl values in sham-exposed mice and slightly lower values in irradiated animals.

DISCUSSION

These experiments were designed to test the hypothesis that a diet high in omega-3 fatty acids would mitigate radiation-induced bone loss by reducing the presence of inflammatory cytokines in bone osteocytes and serum. Unexpectedly, we observed relatively few negative (more often neutral and sometimes positive) impacts of these radiation exposures on bone mass and microarchitecture, so we were unable to test the original hypothesis as stated. In fact, 56Fe exposure in FOP-fed mice resulted in gains in middiaphyseal total and cortical bone area at 4 wk, although these gains were not maintained at 8 wk. Mice exposed to 56Fe also exhibited greater trabecular number in both diet groups, and, in FOP-fed mice, trabecular thickness increased as well. Surprisingly, γ-radiation led to both positive and negative changes in bone, with small radiation-induced declines in volumetric bone mineral density and cortical bone area and improvements in trabecular number and separation. That exposure to 56Fe resulted in neutral or positive changes in bone microarchitecture and geometry (as opposed to the generally negative or neutral impacts of γ-radiation) was unexpected, given the bulk of literature demonstrating heavy iron exposure can be more damaging (3, 44). It should be noted that the doses chosen for the γ- and 56Fe experiments were based on an estimate of ∼4 for the relative biological efficiency (RBE) of 56Fe on gut epithelium. We are unaware of established RBEs for bone structural outcomes; thus it may be that the 2.0-Gy γ-radiation exposure has greater biological impacts on bone cell activity (resulting some wk later in structural change) than does a 0.5-Gy 56Fe exposure.

Previous literature examining the impact of γ-radiation on bone microarchitecture and geometry typically reports significant detriments to cancellous bone and minimal impact on cortical bone (2, 3, 51). However, Bokhari et al. (52) report positive impacts of γ-radiation on bone in ∼48-wk-old female C57Bl/6 mice; it is important to note, in contrast to our study, the study of Bokhari et al. (52) utilized continuous, low-dose and low-dose-rate methodologies totaling 0.175-Gy exposure over 28 days, which may exert very different biological effects than acute, higher dose exposures such as used in the current experiment. Our findings and those of Bokhari et al. (52–56) are consistent with published data that space-relevant radiation may have neutral or even positive impacts on bone integrity. A potential explanation for the differences in radiation impact on bone in our and the aforementioned work may be animal age at irradiation, as the majority of studies documenting a significant detriment to bone utilize animals <4 mo in age, in contrast to the ∼10- to 12-mo-old animals used here to mimic average astronaut age during flight.

Studies investigating the impact of 56Fe on bone outcomes primarily use doses over 1 Gy, which is more applicable to radiation exposure due to a solar flare than GCR. Dosing of 2-Gy 56Fe typically exerts deleterious changes to trabecular microarchitecture (3, 44). Conversely, Bokhari et al. (54) exposed 4-mo-old female mice to 0.5-Gy 56Fe and found improved cancellous microarchitecture 21 days postexposure; cortical geometry was not assessed. Together with data from Bokhari et al, there appears to be a positive impact of low dose 56Fe exposure to bone parameters.

In a number of instances, the FOP diet high in omega-3 fatty acids did modify the alterations in cancellous microarchitecture and cortical geometry after radiation exposure. Given that omega-3 fatty acids reduce immune cell production of TNF-α (36, 37) and a diet comprised of 5% fish oil, similar to the FOP diet here, suppressed gene expression of TNF-α (29), we expected FOP-fed mice exposed to radiation to exhibit lesser inflammation-mediated impacts. Consistent with this, in gamma-irradiated mice, as noted above, distinctive gains in bone volume fraction and connectivity density at 8 wk postirradiation were found only in FOP-fed mice; COC-fed mice exhibited no change or declines, respectively, postirradiation in these two outcomes. However, interpretation of this is complicated by large declines observed in these metrics at 8 wk postradiation in FOP sham mice. On the other hand, the magnitude of the decline in cortical bone area (Ct.Ar) 8 wk following gamma-exposure appears to be slightly larger in FOP- versus COC-fed mice. Furthermore, 4 wk after gamma-exposure FOP-fed mice did not exhibit the gains in trabecular thickness and cancellous vBMD seen in COC-fed mice. Interestingly, in 56Fe-irradiated mice, the opposite result was observed 4 wk after irradiation: COC-fed mice exhibited no change postradiation in trabecular thickness and vBMD, whereas mice on the FOP diet exhibited gains in these parameters. As noted above, these two experiments used acute doses that may well not be biologically equivalent, so the results should be considered independently. Where the largest impairments occurred (bone volume fraction and connectivity density 4 wk after 2-Gy γ-exposure), this anti-inflammatory FOP diet conferred benefits.

We did demonstrate a consistent impact of the FOP diet in the 56Fe experiment, consistent with our hypothesis, on reducing serum TNF-α levels versus those observed in COC-fed mice at all time points. These comparisons gained statistical significance at the final 8-wk time point. Interestingly, in the γ-experiment both sham and irradiated mice fed the FOP diet generally had higher serum TNF-α than COC-fed mice. We have no explanation for these opposing effects of diet, particularly regarding sham mice, across the two experiments utilizing different radiation exposures. A potential explanation for the differing values in serum TNF-α in sham-exposed controls across the 56Fe and gamma-experiments is the extra stress incurred by overnight shipping exposures experienced by mice in the 56Fe experiment. Mice in the 4- and 8-wk timepoints were shipped twice within 2 wk. While likely more relevant for those mice terminated at the 12-h time point, it is possible this extra stress could impact serum TNF-α 4 to 8 wk later. There are no statistically significant differences in other variables (e.g., age, weight) that may account for these differences.

Earlier investigations have demonstrated that osteoclast activity is significantly increased at 3 days postexposure to 2 Gy of X-rays but decreased by 1 wk post (13, 57,58). Using primary cells harvested from mice exposed to 1-Gy X-ray, Lima et al. (51) demonstrated increased osteoclast differentiation, assessed via increased number of colony-forming units, alkaline phosphatase activity, and number of mineralized nodules, at 3 days after exposure, which was no longer apparent at 3 wk. Our data reveal no differences in relative osteoclast surface at 4 or 8 wk after exposure to γ and 56Fe, supporting previous data suggesting that the increase in osteoclast activity is likely transient following acute exposure.

At 8 wk postexposure in 56Fe-irradiated mice, relative osteoid surface (unmineralized new bone matrix) was dramatically reduced with radiation exposure irrespective of diet, consistent with data supporting reductions in osteoblast production and differentiation following irradiation leading to decreased production of new bone matrix and subsequent mineralization (13, 58). Interestingly, at 8 wk postexposure in gamma-irradiated mice, COC-fed mice exhibited no apparent impact of radiation exposure on relative osteoid surface while in FOP-fed mice there was almost undetectable osteoid surface. These same mice exhibited significant improvements in cancellous bone volume fraction and connectivity density at 8 wk post-γ-exposure, suggesting either increased bone formation and/or decreased bone resorption activity in the interim. This decline in new bone matrix formation at 8 wk may presage later decrements in cancellous bone integrity. We detected no differences in relative osteoclast surface across groups in γ- and 56Fe cohorts at either time points. These data are surprising given that previously published data indicate that high dietary omega-3 fatty acid intake is associated with attenuated reductions in bone mineral density and reduced inflammation (24, 28). Consumption of a 9% fish oil diet maintained femoral BMD in female 10-mo-old C57Bl/6 mice via reduced osteoclast formation and enhanced serum alkaline phosphatase and osteocalcin, markers of bone formation (24, 28). Similarly, 5% fish oil effectively suppressed TNF-α activation and osteoclast number and activity without altering osteoblast function after ovariectomy, leading to attenuated bone loss (29).

Despite the key regulatory role of osteocytes in bone, few studies to date have described the osteocyte response to space-relevant radiation exposure. A previous investigation did evaluate marrow cell gene expression, which reflects an average response of multiple cell types, documenting increased expression of TNF-α in response to 2 Gy of γ-radiation within 1 day of exposure, persisting for up to 3 days postexposure; no change in TNF-α expression was detected after exposure to 2.0 Gy of 56Fe (1). In the current study, γ-radiation exposure led 12 h later to more TNF-α-positive osteocytes in COC-fed mice in mid-femur cortical bone, although this impact was no longer evident at 4 wk. The FOP-fed mice exhibited fewer TNF-α-positive osteocytes in cortical bone at 12 h and 4 wk after γ-irradiation. Notably, at these time points in the γ-experiment, FOP-fed-irradiated mice exhibited increased or unchanged serum TNF-α, respectively. Interestingly, 56Fe-exposed mice exhibited no differences in %TNF-α-positive osteocytes in cancellous or cortical bone, despite reduced serum levels of TNF-α in FOP-fed mice at 12-h and 8-wk time points. The lack of coordination between serum levels of and osteocyte colocalization with TNF-α is interesting and suggests differential regulation of TNF-α locally and systemically.

Sclerostin, a downstream target of TNF-α and negative regulator of bone formation (20), would be expected to show a similar pattern to TNF-α. However, sclerostin and SOST gene transcription are influenced by a number of proteins, such as RUNX2 and bone morphogenic protein, which can be in turn be influenced by radiation exposure. Gamma-irradiated mice showed no difference in the proportion of sclerostin-positive osteocytes (% + Ot-Scl) among groups, despite significant differences in cortical bone osteocytes staining positive for TNF-α at 12 h and 4 wk postexposure. Macias et al. (59) irradiated female mice with up to 1-Gy X-rays and did not detect changes in % + Ot-Scl at 3 wk postexposure. Surprisingly, our 56Fe-exposed mice at 4 wk postirradiation exhibited lower % + Ot-Scl in cortical bone. This impact of radiation was reversed by 8 wk postexposure, with increased % + Ot-Scl in 56Fe-exposed mice. A reduction in sclerostin signaling is typically associated with greater bone formation rates, which could not be assessed in the current study. Our previous work demonstrated that exposure to acute and fractionated 0.5 Gy 28Silicon does increase % + Ot-Scl in cortical bone when assessed 3 wk postexposure (59), with concurrent reductions in %mineralizing surface, indicating declines in bone formation activity. Limited comparisons can be made with the current study, as different strains and ages of mice and different ion species were utilized.

A potential confounding factor regarding the dietary impact of omega-3 fatty acids studied here is the role of different types of fiber. Pectin was utilized in the FOP diet and cellulose in the COC diet. The primary difference between these two fiber types is fermentability; pectin is highly fermentable, producing a high level of short chain fatty acids (SCFA), while cellulose is only slightly fermentable. SCFA have been shown to modulate the gut-bone axis through several mechanisms, particularly via modulation of inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, and can directly inhibit osteoclastogenesis (reviewed in Ref. 60). Hence, the change in fiber source in the diet may have contributed to changes observed in TNF-α.

There exist several limitations to this study. First, due to the challenges of generating enough mice of the correct genotype and sex, there is a relatively small n and a fairly large age range within each group. While the mice utilized in this study ranged in age from 30 to 50 wk at the time of radiation, block randomization assured that mean ages were equivalent across all groups. A larger number per group would improve the power of statistical comparisons of this study; hence these results should be interpreted conservatively. Secondly, while the use of older mice to mimic the average age of astronauts during flight is advantageous for several reasons, the fact that older mice exhibit very low baseline cancellous bone mass (BV/TV) and bone turnover rates makes it more challenging to detect impacts of experimental treatments on those parameters (48). The challenges of smaller group sizes and low baseline BV/TV and turnover rates lend credence to the significant group differences we were able to detect. Third, a mixed beam with more precise approximations of GCR composition would provide a more accurate simulation of actual GCR effects on bone outcome. To our knowledge this is not currently feasible even at national laboratory facilities for high-energy ion species in one single exposure, although cells or animals can be exposed to several different species in sequence at NASA’s Space Radiation Laboratory. Lastly, anticipated GCR exposure during future planetary missions will involve long-term, continuous exposure to HZE ions at very low dose rates. Currently, it is not feasible to expose animals to accelerator beams for hours or days at a time. Differences in dose rates across minutes to days alters the biological impact of radiation exposure, as acute and chronic inflammatory responses may lead to different long-term outcomes. For example, our research group has demonstrated positive impacts on bone after continuous (28 days or more) exposure to very low dose-rate γ-radiation (52, 54), in contrast to literature demonstrating significant detriments after acute exposures to 2.0-Gy γ-radiation (3, 58).

These experiments do provide novel data informing our understanding of the impact of radiation on bone structure and cell activity. This study is to our knowledge the first to describe osteocyte responses to space-relevant doses of γ- and 56Fe radiation, which affected only osteocytes in cortical, but not cancellous, bone after radiation exposure. We could not verify a consistent relationship between proportions of cortical bone osteocytes positive for TNF-α and those staining positive for sclerostin. Second, the capacity for a diet high in omega-3 fatty acids to mitigate the serum TNF-α response to space-relevant radiation exposure has not been previously characterized. Interestingly, we found that 2.0-Gy γ-exposures had limited negative impact on bone microarchitecture and geometry up to 8 wk postirradiation; 0.5-Gy 56Fe exposures resulted in no detriments and a few small positive gains (increased cortical cross-sectional areas at 4 wk and increased trabecular number and cancellous vBMD at 8 wk postirradiation). Further research should be done to elucidate the impact of FOP on the response to continuous mixed-ion radiation exposure in male as well as female mice, with a particular emphasis on inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α. In conclusion, we did not demonstrate a negative impact of acute, low-dose exposure to γ or 56Fe radiation on bone structural integrity, though we did demonstrate mitigation of radiation-induced increases in serum TNF-α with a diet high in omega-3 fatty acids. Mitigating radiation-induced inflammatory changes with a low-cost, low-risk dietary intervention should be strongly considered for both clinical and space-explorer populations.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Aeronautics and Space Administration Grant NNX15AD64G (to N. D. Turner) for the parent protocol and Grant NNX17AC91G (to S. A. Bloomfield) and Sydney & J. L. Huffines Institute for Sports Medicine and Human Performance and the College of Education and Human Development awards (to S. E. Little-Letsinger, Texas A&M University).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

N.D.T., J.R.F., and S.A.B. conceived and designed research; N.D.T. and J.R.F. performed experiments; S.E.L. and L.J.S. analyzed data; S.E.L., L.J.S., and S.A.B. interpreted results of experiments; S.E.L. prepared figures; S.E.L. and S.A.B. drafted manuscript; S.E.L., N.D.T., and S.A.B. edited and revised manuscript; S.E.L., N.D.T., J.R.F., L.J.S., and S.A.B. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge and thank Drs. Derek Seidel and Kimberly Wahl for animal protocol execution; Drs. Rihana Bokhari, Corinne Metzger, and Heather Allaway for tissue collection/storage; and Alyssa Falck (L. Suva/D. Gaddy Laboratory) and Dr. Ken Muneoka (Veterinary Physiology and Pharmacology) for assistance with tissue processing for immunohistochemistry.

Present addresses: S. E. Little-Letsinger: Dept. of Medicine, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC; N. D. Turner, Dept. of Food Science and Human Nutrition, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alwood JS, Shahnazari M, Chicana B, Schreurs A, Kumar A, Bartolini A, Shirazi-Fard Y, Globus RK. Ionizing radiation stimulates expression of pro-osteoclastogenic genes in marrow and skeletal tissue. J Interf Cytokine Res 35: 480–487, 2015. doi: 10.1089/jir.2014.0152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bandstra ER, Pecaut MJ, Anderson ER, Willey JS, De Carlo F, Stock SR, Gridley DS, Nelson GA, Levine HG, Bateman TA. Long-term dose response of trabecular bone in mice to proton radiation. Radiat Res 169: 607–614, 2008. doi: 10.1667/RR1310.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamilton S, Pecaut MJ, Gridley DS, Travis ND, Bandstra ER, Willey JS, Nelson GA, Bateman TA. A murine model for bone loss from therapeutic and space-relevant sources of radiation. J Appl Physiol (1985) 101: 789–793, 2006. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01078.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lloyd SA, Bandstra ER, Travis ND, Nelson GA, Daniel J, Pecaut MJ, Gridley DS, Willey JS, Bateman TA. Spaceflight-relevant types of ionizing radiation and cortical bone: Potential LET effect? Adv Space Res 42: 1889–1897, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.asr.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lang T, Leblanc A, Evans H, Lu Y, Genant H, Yu A. Cortical and trabecular bone mineral loss from the spine and hip in long-duration spaceflight. J Bone Miner Res 19: 1006–1012, 2004. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). Space Radiation. 2018. https://www.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/atoms/files/space_radiation_ebook.pdf.

- 7.Vico L, Collet P, Guignandon A, Thomas T, Rehailia M. Effects of long-term microgravity exposure on cancellous and cortical weight-bearing bones of cosmonauts. Lancet 355: 1607–1611, 2000. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02217-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kondo H, Yumoto K, Alwood JS, Mojarrab R, Wang A, Almeida EA, Searby ND, Limoli CL, Globus RK. Oxidative stress and gamma radiation-induced cancellous bone loss with musculoskeletal disuse. J Appl Physiol (1985) 108: 152–161, 2010. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00294.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hall EJ, Giaccia AJ. Radiobiology for the Radiologist. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Wilkins & Williams, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borchers AT, Keen CL, Gershwin ME. Microgravity and immune responsiveness: implications for space travel. Nutrition 18: 889–898, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S0899-9007(02)00913-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crucian BE, Zwart SR, Mehta S, Uchakin P, Quiriarte HD, Pierson D, Sams CF, Smith SM. Plasma cytokine concentrations indicate that in vivo hormonal regulation of immunity is altered during long-duration spaceflight. J Interferon Cytokine Res 34: 778–786, 2014. doi: 10.1089/jir.2013.0129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gueguinou N, Huin-Schohn C, Bascove M, Bueb JL, Tschirhart E, Legrand-Frossi C, Frippiat JP. Could spaceflight-associated immune system weakening preclude the expansion of human presence beyond Earth’ s orbit? J Leukoc Biol 86: 1027–1038, 2009. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0309167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Willey JS, Lloyd SA, Nelson GA, Linda L, Bateman TA. Ionizing radiation and bone loss: space exploration and clinical therapy applications. Clin Rev Bone Min Metab 9: 54–62, 2011. doi: 10.1007/s12018-011-9092-8.Ionizing. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kobayashi BK, Takahashi N, Jimi E, Udagawa N, Takami M, Kotake S, Nakagawa N, Kinosaki M, Yamaguchi K, Shima N, Yasuda H, Morinaga T, Higashio K, Martin TJ, Suda T. Tumor necrosis factor alpha stimulates osteoclast differentiation by a mechanism independent of the ODF/RANKL–RANK Interaction. J Exp Med 191: 275–286, 2000. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.2.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lam J, Ross FP, Teitelbaum SL, Lam J, Takeshita S, Barker JE, Kanagawa O, Ross FP, Teitelbaum SL. TNF-a induces osteoclastogenesis by direct stimulation of macrophages exposed to permissive levels of RANK ligand. J Clin Invest 106: 1481–1488, 2000. doi: 10.1172/JCI11176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hofbauer LC, Lacey DL, Dunstan CR, Spelsberg TC, Riggs BL, Khosla S. Interleukin-1B and tumor necrosis factor-a, but not interleukin-6, stimulate osteoprotegerin ligand gene expression in human osteoblastic cells. Bone 25: 255–259, 1999. doi: 10.1016/S8756-3282(99)00162-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nanes MS. Tumor necrosis factor-a: molecular and cellular mechanisms in skeletal pathology. Gene 321: 1–15, 2003. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(03)00841-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaneki H, Guo R, Chen D, Yao Z, Schwarz EM, Zhang YE, Boyce BF, Xing L. Tumor necrosis factor promotes Runx2 degradation through up-regulation of Smurf1 and Smurf2 in osteoblasts. J Biol Chem 281: 4326–4333, 2006. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509430200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Florencio-Silva R, Rodrigues G, Sasso-Cerri E, Simões MJ, Cerri PS. Biology of bone tissue: structure, function, and factors that influence bone cells. Biomed Res Int 2015: 421746, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baek K, Hwang H, Park H, Kwon A, Qadir AS, Ko S, Woo KMI, Ryoo H, Kim G, Baek J. TNF-a upregulates sclerostin expression in obese mice fed a high-fat diet. J Cell Physiol 229: 640–650, 2014. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Franz-Odendaal TA, Hall BK, Witten PE. Buried alive: how osteoblasts become osteocytes. Dev Dyn 235: 176–190, 2006. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Metzger CE, Narayanan A, Zawieja DC, Bloomfield SA. Inflammatory bowel disease in a rodent model alters osteocyte protein levels controlling bone turnover. J Bone Miner Res 32: 802–813, 2017. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Metzger CE, Narayanan SA. The role of osteocytes in inflammatory bone loss. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 10: 1–7, 2019. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wall R, Ross RP, Fitzgerald GF, Stanton C. Fatty acids from fish: the anti-inflammatory potential of long-chain omega-3 fatty acids. Nutr Rev 68: 280–289, 2010. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2010.00287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Multhoff G, Radons J, Gaipl US. Radiation, inflammation, and immune responses in cancer. Front Oncol 2: 1–18, 2012. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2012.00058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Watkins BA, Li Y, Lippman HE, Feng S. Modulatory effect of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on osteoblast function and bone metabolism. Prostoglandins Leukot Essent Fat Acids 68: 387–398, 2003. doi: 10.1016/S0952-3278(03)00063-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bhattacharya A, Sun D, Rahman M, Fernandes G. Different ratios of eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic omega-3 fatty acids in commercial fish oils differentially alter pro-inflammatory cytokines in peritoneal macrophages from C57BL/6 female mice. J Nutr Biochem 18: 23–30, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bhattacharya A, Rahman M, Sun D, Fernandes G. Effect of fish oil on bone mineral density in aging C57BL/6 female mice. J Nutr Biochem 18: 372–379, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakanishi A, Iitsuka N, Tsukamot I. Fish oil suppresses bone resorption by inhibiting osteoclastogenesis through decreased expression of M-CSF, PU.1, MITF, and RANK in ovariectomized rats. Mol Med Rep 7: 1896–1903, 2013. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2013.1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sakaguchi K, Morita I, Murota S. Eicosapentaenoic acid inhibits bone loss due to ovariectomy in rats. Prostoglandins Leukot Essent Fat Acids 50: 81–84, 1994. doi: 10.1016/0952-3278(94)90151-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun D, Krishnan A, Zaman K, Lawrence R, Bhattacharya A, Fernandes G. Dietary n-3 fatty acids decrease osteoclastogenesis and loss of bone mass in ovariectomized mice. J Bone Miner Res 18: 1206–1216, 2003. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.7.1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zwart SR, Pierson D, Mehta S, Gonda S, Smith SM. Capacity of omega-3 fatty acids or eicosapentaenoic acid to counteract weightlessness-induced bone loss by astronauts. J Bone Miner Res 25: 1049–1057, 2010. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.091041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simopoulos AP. An increase in the omega-6/omega-3 fatty acid ratio increases the risk for obesity. Nutrients 8: 128, 2016. doi: 10.3390/nu8030128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kinsella J, Lokesh B, Broughton S, Whelan J. Dietary polyunsaturated fatty acids and eicosanoids: potential effects on the modulation of inflammatory and immune cells: an overview. Nutrition 6: 24–44, 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tilley SL, Coffman TM, Koller BH, Tilley SL, Coffman TM, Koller BH. Mixed messages: modulation of inflammation and immune responses by prostaglandins and thromboxanes. J Clin Investig 108: 15–23, 2001. doi: 10.1172/JCI200113416.Virtually. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kelley D, Taylor P, Nelson G, Schmidt PC, Ferretti A, Erickson KL, Yu R, Chandra RK, Mackey BE. Docosahexaenoic acid ingestion inhibits natural killer cell activity and production of inflammatory mediators in young healthy men. Lipids 34: 317–318, 1999. doi: 10.1007/s11745-999-0369-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee TH, Shihii C, Coreyll EJ, Lewis RA, Austens KF. Characterization and biologic properties of 5,12-dihydroxy derivatives of eicosapentaenoic acid, including leukotriene B5 and the double lipoxygenase product. J Biol Chem 259: 2383–2389, 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Calder PC. Dietary modification of inflammation with lipids. Proc Nutr Soc 61: 345–358, 2002. doi: 10.1079/PNS2002166, . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Calder PC. n-3 Polyunsaturated fatty acids, inflammation, and inflammatory diseases. Am J Clin Nutr 83: 1505S–1519S, 2006. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.6.1505S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lo C, Chiu KC, Fu M, Lo R, Helton S. Fish oil decreases macrophage tumor necrosis factor gene transcription by altering the NFkB. J Surg Res 82: 216–221, 1999. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1998.5524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Novak TE, Babcock TA, Jho DH, Helton WS, Espat NJ, Novak TE, Babcock TA, Jho DH, Helton WS, Espat NJ, Helton S, Espat NJ. NF-κB inhibition by ω-3 fatty acids modulates LPS-stimulated macrophage TNF-α transcription. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 284: L84–L89, 2003. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00077.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao Y, Joshi-Barve S, Barve S, Chen LH, Zhao Y, Joshi-Barve S, Barve S, Chen LH. Eicosapentaenoic acid prevents LPS-induced TNF-α expression by preventing NF-κB activation. J Am Coll Nutr 23: 71–78, 2004. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2004.10719345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Holguin N, Brodt MD, Sanchez ME, Silva MJ. Aging diminishes lamellar and woven bone formation induced by tibial compression in adult C57BL/6. Bone 65: 83–91, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alwood JS, Tran LH, Schreurs A-S, Shirazi-Fard Y, Kumar A, Hilton D, Tahimic CG, Globus RK. Dose- and ion-dependent effects in the oxidative stress response to space-like radiation exposure in skeletal system. Int J Mol Sci 18, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Willey JS, Lloyd SA, Robbins ME, Bourland JD, Smith-Sielicki H, Bowman LC, Norrdin RW, Bateman TA. Early increase in osteoclast number in mice after whole-body irradiation with 2 Gy X rays. Radiat Res 170: 388–392, 2008. doi: 10.1667/RR1388.1.Early. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yumoto K, Globus RK, Mojarrab R, Arakaki J, Wang A, Searby ND, Almeida EA, Limoli CL. Short-term effects of whole-body exposure to 56Fe ions in combination with musculoskeletal disuse on bone cells. Radiat Res 173: 494–504, 2010. doi: 10.1667/RR1754.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bouxsein ML, Boyd SK, Christiansen BA, Guldberg RE, Jepsen KJ, Mu R. Guidelines for assessment of bone microstructure in rodents using micro-computed tomography. J Bone Miner Res 25: 1468–1486, 2010. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dempster DW, Compston JE, Drezner MK, Kanis FH, John AM, Ott S, Malluche HM, Meunier PJ, Recker RR, Parfitt M. Histomorphometry nomenclature: a 2012 update of the report of the ASBMR histomorphometry nomenclature. J Bone Miner Res 28: 2–17, 2013. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1805.Standardized. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Raehtz S, Bierhalter H, Schoenherr D, Parameswaran N, McCabe LR. Estrogen deficiency exacerbates type 1 diabetes-induced bone TNF-a expression and osteoporosis in female mice. Endocrinology 158: 2086–2101, 2017. doi: 10.1210/en.2016-1821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Burt PM, Xiao L, Hurley MM. FGF23 regulates Wnt/B-catenin signaling-mediated osteoarthritis in mice overexpressing high-molecular-weight FGF2. Endocrinology 159: 2386–2396, 2018. doi: 10.1210/en.2018-00184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lima F, Swift JM, Greene ES, Allen MR, Cunningham DA, Braby LA, Bloomfield SA. Exposure to low-dose X-ray radiation alters bone progenitor cells and bone microarchitecture. Radiat Res 188: 433–442, 2017. doi: 10.1667/RR14414.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bokhari RS. Skeletal Impacts of Continuous Low-Dose-Rate Gamma Radiation Exposure During Simulated Microgravity. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bandstra ER, Thompson RW, Nelson GA, Willey JS, Judex S, Cairns MA, Benton ER, Vazquez ME, Carson JA, Bateman TA. Musculoskeletal changes in mice from 20-50 cGy of simulated galactic cosmic rays. Radiat Res 172: 21–29, 2009. doi: 10.1667/RR1509.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bokhari RS, Metzger CE, Black JM, Franklin KA, Boudreaux RD, Allen MR, Macias BR, Hogan HA, Braby LA, Bloomfield SA. Positive impact of low-dose, high-energy radiation on bone in partial- and/or full-weightbearing mice. NPJ Microgravity 5: 1–9, 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41526-018-0061-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Karim L, Judex S. Low level irradiation in mice can lead to enhanced trabecular bone morphology. J Bone Miner Metab 32: 476–483, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yu K, Doherty AH, Genik PC, Gookin SE, Roteliuk DM, Wojda SJ, Jiang ZS, McGee-Lawrence ME, Weil MM, Donahue SW. Mimicking the effects of spaceflight on bone: Combined effects of disuse and chronic low-dose rate radiation exposure on bone mass in mice. Life Sci Space Res (Amst) 15: 62–68, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.lssr.2017.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Willey JS, Grilly LG, Howard SH, Pecaut MJ, Obenaus A, Gridley DS, Nelson GA, Bateman TA. Bone architectural and structural properties after 56Fe26+ radiation-induced changes in body mass. Radiat Res 170: 201–207, 2008. doi: 10.1667/RR0832.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Willey JS, Lloyd SA, Nelson GA, Bateman TA. Space radiation and bone loss. Gravit Sp Biol Bull 25: 14–21, 2012. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Macias BR, Lima F, Swift JM, Shirazi-Fard Y, Greene ES, Allen MR, Fluckey J, Hogan HA. Simulating the lunar environment: partial weightbearing and high-LET radiation-induce bone loss and increase sclerostin-positive osteocytes. Radiat Res 263: 254–263, 2016. doi: 10.1667/RR13579.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zaiss MM, Jones RM, Schett G, Pacifici R. The gut-bone axis: how bacterial metabolites bridge the distance. J Clin Invest 129: 3018–3028, 2019. doi: 10.1172/JCI128521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]