Abstract

Background

The response to immunotherapy can be impaired by several factors including external intervention such as drug interactions with immune system. We aimed to examine the immunomodulatory action of opioids, since immune cells express opioid receptors able to negatively influence their activities.

Methods

This observational, multicenter, retrospective study, recruited patients with different metastatic solid tumors, who have received immunotherapy between September 2014 and September 2019. Immunotherapy was administered according to the standard schedule approved for each primary tumor and line of treatment. The concomitant intake of antibiotics, antifungals, corticosteroids and opioids were evaluated in all included patients. The relationship between tumor response to immunotherapy and the oncological outcomes were evaluated. A multivariate Cox-proportional hazard model was used to identify independent prognostic factors for survival.

Results

One hundred ninety-three patients were recruited. Overall, progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were significantly shorter in those patients taking opioids than in those who didn’t (median PFS, 3 months vs. 19 months, HR 1.70, 95% CI 1.37–2.09, p < 0.0001; median OS, 4 months vs. 35 months, HR 1.60, 95% CI 1.26–2.02, p < 0.0001). In addition, PFS and OS were significantly impaired in those patients taking corticosteroids, antibiotics or antifungals, in those patients with an ECOG PS ≥ 1 and in patients with a high tumor burden. Using the multivariate analyses, opioids and ECOG PS were independent prognostic factors for PFS, whereas only ECOG PS resulted to be an independent prognostic factor for OS, with trend toward significance for opioids as well as tumor burden.

Discussion

Our study suggests that the concomitant administration of drugs as well as some clinical features could negatively predict the outcomes of cancer patients receiving immunotherapy. In particular, opioids use during immunotherapy is associated with early progression, potentially representing a predictive factor for PFS and negatively influencing OS as well.

Conclusions

A possible negative drug interaction able to impair the immune response to anti-PD-1/PD-L1 agents has been highlighted. Our findings suggest the need to further explore the impact of opioids on immune system modulation and their role in restoring the response to immunotherapy treatment, thereby improving patients' outcomes.

Keywords: Immunotherapy, Opioids, Opioid receptors, Prognostic factor, Predictive factor, Early progression

Background

The immune-checkpoint monoclonal antibodies inhibitors (ICIs), a class of drugs targeting the inhibitory immune-checkpoint receptors, have demonstrated significant improvement in overall survival (OS) in many cancer types and actually representing a revolutionary milestone in oncology [1]. The immune system is involved in the recognition and destruction of cancer cells, nevertheless tumor subclones with reduced immunogenicity, such as loss of antigen presentation, low levels of programmed death ligand-1 (PDL1) expression and IFN-γ secretion by T cells, can be selected2 avoiding immune destroy and leading to tumor growth and clinically evident disease [2, 3].

Several studies have demonstrated that, in a proportion of patients, ICIs can induce durable response, generating long-lasting specific immunological memory against tumor [4]. Thus, immunotherapy has become the standard of care in several solid tumors, including advanced melanoma [5, 6], no-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [7–10], renal cell carcinoma (RCC) [11, 12], Merkel carcinoma [13] and in colon-cancer patients with microsatellite instability–high (MSI-H) or mismatch repair–deficient (d-MMR) tumors [14].

Several studies will aim to understand which mechanisms, factors or tumor’ pathways generate inherently or acquired resistance to cancer immunotherapies [15]. Response to ICIs can be influenced by several factors: the molecular profile of cancer [16–19], histopathological features of tumor [20–22] and clinical characteristics of patient, such as site of metastases [23, 24], Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Performance Status (PS) [25, 26], previous treatments [27–30] or external intervention such as drug interactions with immune system [31]. While corticosteroids and antibiotics are already known to have an immunomodulatory effect [32–34], less well known is the effect of concomitant opioids therapy used in symptomatic patients for the treatment of uncontrolled pain [35].

The aim of our study is to explore the relationship between the administration of concomitant to immunotherapy drugs (such as opioids alone or in association with antibiotics/antifungals or corticosteroids), with the oncological outcomes in order to evaluate a possible negative drug interaction able to impair the immune response to anti-PD-1 / PD-L1 agents. The removal of concomitant drugs with immunoinhibitory action could play a decisive role in restoring the response to immunotherapy treatment, so improving patients' outcomes.

Materials and methods

Patients

This observational, multicenter, retrospective study, recruited patients with metastatic solid tumors, including NSCLC (squamous/non squamous histology), melanoma, RCC, urothelial cancer, Merkel carcinoma and colon-cancer, who have received immunotherapy from September 2014 to September 2019. The follow-up period was from October 2014 to January 2020.

Imaging evaluation based on contrast enhanced computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance (MRI) was performed in order to confirm the baseline disease setting and tumor burden.

Data including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), PS, comorbidities, were retrospectively collected. Primary tumor sites, previous lines of chemotherapy or target therapy and the tumor burden and the site of metastases (bone vs. visceral) were collected as well.

The concomitant intake of antibiotics, antifungals, corticosteroids and opioids were evaluated in all included patients. Based on the category of opioids, only patients receiving strong opioids were included into the analysis.

All patients provided a written informed consent, and the protocol approval of Local Ethics Committee was obtained [CE 5618].

Treatment and assessments

Immunotherapy was administered according to the standard schedule approved for each primary tumor and line of treatment. Nivolumab was administered at the standard dose of 240 mg intra-venously at 2-weeks interval, pembrolizumab at the standard dose of 200 mg intravenously at 3-weeks interval, Atezolizumab 1200 mg at 3-weeks interval and Avelumab 800 mg at 2-weeks interval.

Imaging assessment was performed after 12 weeks or before in case of evident clinical disease progression. Tumor response was assessed using immune-related Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (i-RECIST) [36, 37] and classified as complete response (RC), partial response (RP), stable disease (SD), and progressive disease (PD).

Treatment toxicity was assessed every 2/3 weeks, according to the National Cancer Institute-Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.0 (CTCAE version 4.03, 2010).

Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as the time from patient’s first administration of ICIs until the first progression or in-treatment death. Early progression disease was defined as a progression until 3 months from the beginning of immunotherapy treatment. The OS was defined as the time from patient registration to death from any cause. Tumor burden was defined as ‘low’ (≤ 2 metastatic sites) or ‘high’ (≥ 3metastatic sites).

Statistical analysis

In the descriptive analysis, quantitative variables were described as mean and range, while qualitative variables were reported as number and percentage. Univariate associations between clinicopathological features and opioids use were evaluated using the χ2 test. Survival curves were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and the log-rank test was used for the difference assessment. A multivariate Cox-proportional hazard model was used to identify independent prognostic factors for survival. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. SPSS statistical software, Version 25 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, Illinois, USA) was used.

Results

Patients

A total of 193 consecutive metastatic patients treated with ICIs in first, second line or beyond were enrolled in this study. The baseline clinical characteristics are reported in Table 1. One hundred and twenty patients (62%) were male, the median age was 70 years (range 24–91), 122 patients (63%) with less than 2 comorbidities and 94 (49%) with a good Baseline ECOG PS. The primary tumor was in 99 (51%) melanoma, in 59 (30%) NSCLC, in 28 (14%) clear cell RCC, in 5 (3%) urothelial cancer, in 1 (0.5%) Merkel carcinoma and in 1 (0.5%) colon cancer.

Table 1.

Clinical and pathological features of the study population

| Total | OPIODS | NO OPIODS | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N. (%) | N. (%) | N. (%) | |||

| 193 (100) | 42 (100) | 151 (100) | |||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 120 (62) | 25 (60) | 95(63) | 0.689 | |

| Female | 73 (38) | 17 (40) | 56 (37) | ||

| Age (years) | |||||

| Median | |||||

| < 65 | 61 (32) | 14 (33) | 47 (31) | ||

| 65–75 | 78 (40) | 21 (50) |

57 (38) 57 (38) |

||

| > 75 | 53 (53) | 7 (17) | 46 (31) | 0.171 | |

| Missed | 1 (1) | ||||

| Diagnosis | |||||

| NSCLC | 59 (30) | 21(62) | 33 (22) | < 0.0001 | |

| Melanoma | 99 (51) | 7 (17) | 92 (61) | ||

| Renal Cancer | 28 (14) | 5 (12) | 23 (15) | ||

| Urothelial Cancer | 5 (3) | 3 (7) | 2 (1) | ||

| Merkel Tumor | 1 (0.5) | 1 (2) | 0 | ||

| Colon Cancer | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 1 (1) | ||

| ECOG PS | |||||

| 0 | 94 (49) | 9 (21) | 85 (56) | ||

| ≥1 | 99 (51) | 33 (79) | 66 (44) | < 0.0001 | |

| Comorbidity | |||||

| 0–1 | 122 (63) | 29 (69) | 93 (62) | 0.375 | |

| ≥2 | 71 (37) | 13 (31) | 58 (38) | ||

| Immunotherapy, drug name | |||||

| Nivolumab | 121 (63) | 26 (62) | 95 (63) | 0.145 | |

| Pembrolizumab | 60 (31) | 11 (26) | 49 (32) | ||

| Atezolizumab | 11 (6) | 4 (10) | 7 (5) | ||

| Avelumab | 1 (0.5) | 1 (2) | 0 | ||

| Immunotherapy setting | |||||

| First line | 91 (47) | 11 (26) | 80 (53) | ||

| Second line | 69 (36) | 21 (50) | 48 (32) | 0.009 | |

| Beyond II-line | 33 (17) | 10 (24) | 23 (15) | ||

| Antibiotics/Antifungals | |||||

| Yes | 21 (11) | 8 (19) | 13 (9) | 0.055 | |

| Not | 172 (89) | 34 (81) | 138 (91) | ||

| Corticosteroids | |||||

| Yes | 44 (23) | 20 (48) | 24 (16) | < 0.0001 | |

| Not | 148 (77) | 22 (52) | 126 (84) | ||

| Opiods | |||||

| Yes | 42 (22) | - | - | ||

| Not | 151 (78) | - | - | ||

| Tumor burden | |||||

| Low | 91 (47) | 12 (29) | 79 (52) | ||

| High | 102 (53) | 30 (71) | 72 (48) | 0.006 | |

PS ECOG performance status, NSCLC non-small cell lung cancer, RCC renal cell carcinoma

Overall, the immunotherapy treatment was planned as first line in 91 patients (46%) while 69 (37%) of patients received immunotherapy as second and 33 (17%) as subsequent lines.

Nivolumab was the most frequently prescribed drug (123 patients, 63%), followed by pembrolizumab (60 patients, 31%), while the anti PD-L1 atezolizumab and avelumab were administered in 11 (6%) patients and 1 (0.5%) patient, respectively.

Twenty-one (11%), 44 (23%) and 42 (22%) patients received antibiotics/antifungals, corticosteroids and opioids before and/or during immunotherapy (Table 1).

As it is shown in Table 1, opioids use was significantly higher in patients affected by NSCLC (p < 0.0001), in patients with a worse ECOG PS (p < 0.0001), in second-line setting subgroup (p = 0.009), in patients taking corticosteroids (p < 0.0001) and in patients with a high tumor burden (p = 0.006).

Outcomes

With a median follow up of 12 months (95% CI 6.8–17.2 months), 114 (61%) disease progression and 82 (43%) deaths were reported. Early progression occurred in 101 pts (52.3%) and, considering only the concomitant medications, it was significantly associated with opioid use (p = 0.015) (Table 2).

Table 2.

association between several concomitant medications and the number of early progressions

| Early PD | ||

|---|---|---|

| N(%) | p | |

| Antibiotics/antimicotics | ||

| YES v NOT | 13 (52) v 94 (51) | 1 |

| Opioids | ||

| YES v NOT | 29 (69) v 72 (47) | 0.015 |

| Infections | ||

| YES v NOT | 8 (67) v 93 (51) | 0.379 |

The use of opioids resulted significantly associated with early progression. In bold p ≤ 0.05

PD progressive disease

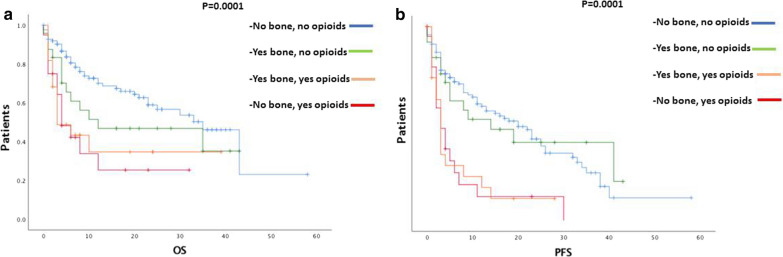

Overall, PFS and OS were significantly shorter in patients with an ECOG PS ≥ 1 compared to those with: ECOG PS = 0 (median PFS, 4 vs. 25 months, HR 1.65, 95% CI 1.36–1.99, p < 0.0001; median OS, 7 months vs. not reached, HR 2.25, 95% CI 1.74–2.90, P < 0.0001), to patients taking corticosteroids (median PFS, 3 vs. 18 months, HR 2.13, 95% CI 1.40–3.24, p < 0.0001; median OS, 6 vs. 35 months, HR 2.48, 95% CI 1.55–3.97, p < 0.0001), to patients taking opioids (median PFS, 3 vs. 19 months, HR 1.70, 95% CI 1.37–2.09, p < 0.0001; median OS, 4 vs. 35 months, HR 1.60, 95%CI 1.26–2.02, p < 0.0001, Fig. 1A/B) and patients with higher volume tumor burden (median, PFS 5 vs. 22 months, HR 1.79, 95% CI 1.22–2.62, p = 0.003; median OS, 10 vs. 43 months, HR 2.06, 95%CI 1.31–3.24, p = 0.002).

Fig. 1.

Association between opioids use and outcomes: OS (a) and PFS (b)

OS was significantly shorter also in patients who used antibiotics or antifungals (median OS, 6 vs. 33 months, HR 2.24, 95% CI 1.25–3.99, p = 0.006).

However, at the multivariate analyses, ECOG PS and opioids were independent prognostic factors for PFS (Table 3), whereas only ECOG PS resulted to be an independent prognostic factor for OS, but with trend toward significance for opioids as well as tumor burden (Table 3).

Table 3.

Univariate and Multivariate analysis for progression free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS)

| Cox-regression analysis for survival | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate (PFS) | Multivariate (PFS) | Univariate (OS) | Multivariate (OS) | |||||

| HR (95%CI) |

p | HR (95%CI) |

p | HR (95%CI) |

P | HR (95%CI) |

p | |

| Sex Female v Male |

0.9 (0.60–1.30) |

0.548 |

1.03 (0.65–1.58) |

0.934 | ||||

| Age categories | ||||||||

| > 75 v 65–75 v < 65 |

1.06 (0.83–1.34) |

0.633 |

1.19 (0.89–1.58) |

0.232 | ||||

| Baseline ECOG PS 31 v 0 |

1.65 (1.36–1.99) |

< 0.0001 |

1.46 (1.19–1.80) |

< 0.0001 |

2.25 (1.74–2.90) |

< 0.0001 |

1.99 (1.52–2.61) |

< 0.0001 |

| Comorbidities 32 v 0–1 |

0.84 (0.57–1.24) |

0.386 |

0.97 (0.62–1.54) |

0.918 | ||||

| Immunotherapy setting III- and beyond v II- v I-line |

0.956 (0.75–1.21) |

0.721 |

1.06 (0.81–1.42) |

0.606 | ||||

| Antibiotics antimicotics | ||||||||

| YES v NOT |

1.5 (0.82–2.73) |

0.187 |

2.24 (1.25–3.99) |

0.006 |

1.48 (0.80–2.73) |

0.201 | ||

| Corticosteroids | ||||||||

| YES v NOT |

2.13 (1.40–3.24) |

< 0.0001 |

1.42 (0.90–2.23) |

0.122 |

2.48 (1.55–3.97) |

< 0.0001 |

1.41 (0.84–2.35) |

0.19 |

| Opioids | ||||||||

| YES v NOT |

1.69 (1.37–2.09) |

< 0.0001 |

1.44 (1.15–1.79) |

0.001 |

1.6 (1.26–2.02) |

< 0.0001 |

1.24 (0.97–1.61) |

0.087 |

| Tumor burden | ||||||||

| High v Low |

1.79 (1.22–2.62) |

0.003 |

1.43 (0.97–2.11) |

0.071 |

2.06 (1.31–3.24) |

0.002 |

1.58 (0.98–2.52) |

0.057 |

mPFS median progression free survival, mOS median overall survival, HR hazard ratio, p p value. In bold p ≤ 0.05

In these analyses for survival we didn’t include primary tumor diagnosis among clinicopathological factors examined, according to the different tumor-intrinsic prognosis which does not make a direct comparison possible. As shown in Fig. 2, there is a statistical significance between opioids use and survival only in melanoma subgroup (p = 0.011).

Fig. 2.

Impact on survival of opioids in different types of cancer. a Non small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), b melanoma, c renal cell carcinoma (RCC). d Urothelial cancer

Both OS and PFS were significantly shorter in patients taking opioids regardless of the presence of bone metastases (p < 0.0001) [Fig. 3].

Fig. 3.

Impact on survival outcomes of opioids in patients with bone metastases. Oncological patients who need opioids during immunotherapy have worse OS (a) and PFS (b) regardless of they have or have not bone metastases

Discussion

Despite the success of immunotherapy in the cancer treatment, only a small percentage of patients presents long term benefit. So, the research of biomarkers represents an urgent need considering that only PD-L1 is routinely available to choose the treatment strategy of our patients. In this context, clinical features could drive the physicians for the definition of therapeutic strategy.

Our study, including different solid tumors, suggests that some clinical features such as ECOG PS and concomitant administration of opioids could negatively predict the outcomes of cancer patients receiving immunotherapy. In particular, opioids use is associated with early progression and could represent a predictive factor for PFS. Moreover, on multivariate analysis, the use of opioids appears to have a tendency to negatively influence OS as well.

ECOG PS has been confirmed to be one of the most important prognostic factors, indeed a worse PS is closely associated with high tumor burden and symptomatic disease requiring concomitant therapies. Corticosteroids are well known to have an immunosuppressive action however they are used for the treatment of adverse immune-related events of immunotherapy [37]. Indeed, corticosteroids are able to activate the glucocorticoids responsive elements (GRE) resulting in a inhibition in IL-1 and IL-6 transcription and in a reduction in T cell function [38].

On the other hand, also the link between opioids and immune system could play a crucial role to determine the resistance to immunotherapy due to the presence of opioids receptor on immune cells.

Indeed, it has been shown, on mice spleen models, the presence of μ receptors on lymphocytes surface and in vitro experiments that the administration of morphine affected directly the lymphocytes proliferation and antibody formation, by binding to μ receptors [39–41].

Furthermore, morphine and buprenorphine, through the p38 MAPK and the calcium pathway, with a mechanism ligand dependent, induced substantial reduction of interleukin-4 mRNA and protein in T cells [42].

While methadone by acting on μ and δ receptors on lymphocytes is able to limit the immune system response, in vitro studies showed that at the transcription level this analgesic drug can decrease the proliferation and the activity of lymphocytes through down-regulation of G-protein- coupled opioid receptor gene. The consequent DNA methylation can suppress immune function [43].

It was pointed out that morphine decreases the ability of natural killer (NK) cells and in particular to induce apoptosis in a target tumor cell line, through both the classical opioid receptor and Toll-like receptor (TLR)-4 [44]. These studies, using purified primary human NK cells from peripheral blood and opioid receptor- or TL4 pathway-specific inhibitors, have shown that morphine appears to increase NK cell secretion of IL-6, granzyme A, and granzyme B. This production was so copious and unbalanced that cytotoxic efficiency of immune system was compromised [45].

It has been studied the role of Fentanyl in the perioperative period especially after 48 h after surgery, pointing out that when administered with large dose anesthesia, caused a suppression of NK cell function. The related mechanism though which this occurs consists in the impairment of the activity of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, resulting in lower levels of adrenocorticotropic hormone and cortisol or reduction in the production of cytokines such as IFN-y and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) [46].

Several studies investigated the role of opioid receptors on lymphocytes surface and their ability, after the binding with an agonist, to reduce the activity of the immune system. It has been proven that in addition to the three classical opioid receptors μ, k and δ, a fourth receptor is involved namely N/OFQ peptide receptor (NOP). This is present on several immune cell subtypes such as polymorphonuclear cells, B cells, T cells and monocytes and mast cells. Even if with little affinity, morphine binds to the NOP with the consequent inhibition of release of immunomodulatory neurotransmitters such as dopamine, histamine, noradrenaline and glutamate resulting in a reduction of immune activity [47].

Moreover, clinical and preclinical evidences suggest that opioids drugs are able to modify the GUT microbiota inducing microbial dysbiosis and bacterial translocation through the impairment of the mucosal barrier function. These changes in gut microbiota could trigger inflammation and abnormal immune response [48–50].

In literature, there are few clinical evidences about the effect of opioid use in cancer response to immunotherapy. In a retrospective study including 102 patients with advanced cancer in treatment with immunotherapy, antibiotic and opioids use were associated with poor outcome in term of PFS and OS [51]. To our knowledge, our study population is the most numerous among studies aimed at investigating the relationship between opioid therapy and outcomes during immunotherapy. Although the negative prognostic impact of bone metastases during immunotherapy is confirmed in literature, our results highlighted that patients with bone metastases taking opioids have the worst prognosis regardless all other site of metastasis [52–54], highlighting the prognostic independence of opioid-based therapy from prevalent metastatic site.

However, our study has several limitations due to its retrospective nature; it includes an heterogeneous population in terms of primary tumor, line of therapy, and kind of anti PD1/PD-L1 agent administered. Moreover, the use of analgesic treatment is more frequently used in patients with advanced cancer, in compromised general condition by the burden of disease and symptoms that all could act as possible confounding factors to the retrospective analysis. All patients in study population received strong opioids including morphine, fentanyl and oxycodone. Given the restrospective nature of the study, it was not possible to define the impact of the specific opiod on survival since most patients underwent opioid switch during immunotherapy, also experimenting with different dosages. The current clinical practice of opioids rotation would have created numerous biases in the retrospective analysis. It is desirable, given the strong biological rationale demonstrated, to conduct prospective studies to explore the impact of opioids on immune system modulation possibly trying to differentiate the actions and consequences of the different types of opioid drugs.

Moreover, concomitant poly-pharmacological therapies identify a class of patients characterized by worse general clinical conditions, heavily pre-treated, with a high burden of disease and comorbidities with a consequently a poor prognosis group so as to expect a poor outcome from immunotherapy.

Conclusion

In conclusion, before starting immunotherapy each patient should undergo to an overall multidisciplinary assessment in order to organize a safe therapeutic approach by identifying all the clinical aspects that may compromise the outcomes. A correct clinical evaluation together with new predictive molecular biomarkers will allow in the future to a better selection of patients and the personalization of treatments removing negative drug interactions and finally by applying the principle of precision medicine.

Acknowledgements

None

Abbreviations

- ICIs

Immune checkpoint inhibitors

- OS

Overall survival

- PDL1

Programmed death ligand-1

- NSCLC

No small cell lung cancer

- RCC

Renal cell carcinoma

- d-MMR

Mismatch repair–deficient

- MSI-H

Microsatellite instability–high

- ECOG

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

- PS

Performance status

- CT

Computed tomography

- MRI

Magnetic resonance

- BMI

Body mass index

- i-RECIST

Immune-related Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors

- RC

Complete response

- SD

Stable disease

- PD

Progressive disease

- PFS

Progression free survival

- CTCAE

Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version

- GRE

Glucocorticoids responsive elements

- NK

Natural killer

- TLR

Toll like receptor

- HPA

Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal

- TNFα

Tumor necrosis factor α

- NOP

N/OFQ peptide receptor

Authors' contributions

PM, SM and AB conceived the study. AB, SM and PM designed the work. GP, AC and SS wrote the manuscript. GP, FRDP and AC acquired the data. MR analyzed the data. AG, EC, GL, FDG and SM discussed results and implications of findings. Supervision, SM and PM. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Sapienza University of Rome.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All patients provided a written informed consent, and the protocol approval of Local Ethics Committee was obtained [CE 5618]. All the procedures performed were part of the routine care.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

PAOLO MARCHETTI (PM) has/had a consultant/advisory role for BMS, RocheGenentech, MSD,Novartis, Amgen, Merck Serono, Pierre Fabre, Incyte. The other authors declare they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Andrea Botticelli and Alessio Cirillo contributed equally to this work Silvia Mezi and Paolo Marchetti contributed equally to this work

References

- 1.Sharma P, Allison JP. The future of immune checkpoint therapy. Science. 2015;348(6230):56–61. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa8172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Sullivan T, Saddawi-Konefka R, Vermi W, Koebel CM, Arthur C, White JM, et al. Cancer immunoediting by the innate immune system in the absence of adaptive immunity. J Exp Med. 2012;209(10):1869–1882. doi: 10.1084/jem.20112738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mandai M, Hamanishi J, Abiko K, Matsumura N, Baba T, Konishi I. Dual faces of IFNγ in cancer progression: a role of PD-L1 induction in the determination of pro- and antitumor immunity. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(10):2329–2334. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schadendorf D, Hodi FS, Robert C, Weber JS, Margolin K, Hamid O, et al. Pooled analysis of long-term survival data from phase II and phase III trials of Ipilimumab in unresectable or metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(17):1889–1894. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.2736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ascierto PA, Long GV, Robert C, Brady B, Dutriaux C, Di Giacomo AM, et al. Survival outcomes in patients with previously untreated braf wild-type advanced melanoma treated with nivolumab therapy: three-year follow-up of a randomized phase 3 trial. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(2):187–194. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.4514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, Grob JJ, Rutkowski P, Lao CD, et al. Five-year survival with combined nivolumab and ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(16):1535–1546. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reck M, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, Hui R, Csőszi T, Fülöp A, et al. Updated analysis of KEYNOTE-024: pembrolizumab versus platinum-based chemotherapy for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer with PD-L1 Tumor Proportion Score of 50% or greater. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(7):537–546. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.00149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gadgeel S, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Speranza G, Esteban E, Felip E, Dómine M, et al. Updated analysis from KEYNOTE-189: pembrolizumab or placebo plus pemetrexed and platinum for previously untreated metastatic nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(14):1505–1517. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.03136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.West H, McCleod M, Hussein M, Morabito A, Rittmeyer A, Conter HJ, et al. Atezolizumab in combination with carboplatin plus nab-paclitaxel chemotherapy compared with chemotherapy alone as first-line treatment for metastatic non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (IMpower130): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(7):924–937. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30167-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herbst RS, Garon EB, Kim DW, Cho BC, Perez-Gracia JL, Han JY, et al. Long-term outcomes and retreatment among patients with previously treated, programmed death-ligand 1-positive, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer in the KEYNOTE-010 Study. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(14):1580–1590. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Powles T, Plimack ER, Soulières D, Waddell T, Stus V, Gafanov R, et al. Pembrolizumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib monotherapy as first-line treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma (KEYNOTE-426): extended follow-up from a randomized, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(12):1563–1573. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30436-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, George S, Hammers HJ, Srinivas S, Tykodi SS, et al. Nivolumab versus everolimus in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma: Updated results with long-term follow-up of the randomized, open-label, phase 3 CheckMate 025 trial. Cancer. 2020;126(18):4156–4167. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.D'Angelo SP, Russell J, Lebbé C, Chmielowski B, Gambichler T, Grob JJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of first-line avelumab treatment in patients with stage IV metastatic merkel cell carcinoma: a preplanned interim analysis of a clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(9):e180077. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.0077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.André T, Shiu KK, Kim TW, Jensen BV, Jensen LH, Punt C, et al. Pembrolizumab in microsatellite-instability-high advanced colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(23):2207–2218. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2017699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O'Donnell JS, Long GV, Scolyer RA, Teng MW, Smyth MJ. Resistance to PD1/PDL1 checkpoint inhibition. Cancer Treat Rev. 2017;52:71–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2016.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frigola J, Navarro A, Carbonell C, Callejo A, Iranzo P, Cedrés S, et al. Molecular profiling of long-term responders to immune checkpoint inhibitors in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Mol Oncol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.12891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu-Lieskovan S, Lisberg A, Zaretsky JM, Grogan TR, Rizvi H, Wells DK, et al. Tumor characteristics associated with benefit from pembrolizumab in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(16):5061–5068. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-4275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Allen EM, Miao D, Schilling B, Shukla SA, Blank C, Zimmer L, et al. Genomic correlates of response to CTLA-4 blockade in metastatic melanoma. Science. 2015;350(6257):207–211. doi: 10.1126/science.aad0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rizvi NA, Hellmann MD, Snyder A, Kvistborg P, Makarov V, Havel JJ, et al. Cancer immunology. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Science. 2015;348(6230):124–128. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hellmann MD, Nathanson T, Rizvi H, Creelan BC, Sanchez-Vega F, Ahuja A, et al. Genomic features of response to combination immunotherapy in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Cell. 2018;33(5):843–852.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fumet JD, Truntzer C, Yarchoan M, Ghiringhelli F. Tumour mutational burden as a biomarker for immunotherapy: Current data and emerging concepts. Eur J Cancer. 2020;131:40–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.02.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Botticelli A, Mezi S, Pomati G, Cerbelli B, Cerbelli E, Roberto M, et al. Tryptophan catabolism as immune mechanism of primary resistance to anti-PD-1. Front Immunol. 2020;7(11):1243. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Botticelli A, Cirillo A, Scagnoli S, Cerbelli B, Strigari L, Cortellini A, et al. The agnostic role of site of metastasis in predicting outcomes in cancer patients treated with immunotherapy. Vaccines (Basel) 2020;8(2):203. doi: 10.3390/vaccines8020203.PMID:32353934;PMCID:PMC7349154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bilen MA, Shabto JM, Martini DJ, Liu Y, Lewis C, Collins H, et al. Sites of metastasis and association with clinical outcome in advanced stage cancer patients treated with immunotherapy. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):857. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-6073-7.PMID:31464611;PMCID:PMC6716879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang F, Markovic SN, Molina JR, Halfdanarson TR, Pagliaro LC, Chintakuntlawar AV, et al. Association of sex, age, and eastern cooperative oncology group performance status with survival benefit of cancer immunotherapy in randomized clinical trials: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(8):e2012534. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.12534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pluvy J, Brosseau S, Naltet C, Opsomer MA, Cazes A, Danel C, Khalil A, et al. Lazarus syndrome in nonsmall cell lung cancer patients with poor performance status and major leukocytosis following nivolumab treatment. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(1):1700310. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00310-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramakrishnan R, Gabrilovich DI. Mechanism of synergistic effect of chemotherapy and immunotherapy of cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2011;60(3):419–423. doi: 10.1007/s00262-010-0930-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Green DR, Ferguson T, Zitvogel L, Kroemer G. Immunogenic and tolerogenic cell death. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9(5):353–363. doi: 10.1038/nri2545.PMID:19365408;PMCID:PMC2818721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shurin GV, Tourkova IL, Kaneno R, Shurin MR. Chemotherapeutic agents in noncytotoxic concentrations increase antigen presentation by dendritic cells via an IL-12-dependent mechanism. J Immunol. 2009;183(1):137–144. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Botticelli A, Mezi S, Pomati G, Sciattella P, Cerbelli B, Roberto M, et al. The impact of locoregional treatment on response to nivolumab in advanced platinum refractory head and neck cancer: the need trial. Vaccines (Basel) 2020;8(2):191. doi: 10.3390/vaccines8020191.PMID:32326034;PMCID:PMC7349768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zeng X, Zhu S, Xu C, Wang Z, Su X, Zeng D, et al. Effect of comorbidity on outcomes of patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer undergoing anti-PD1 immunotherapy. Med Sci Monit. 2020;7(26):e922576. doi: 10.12659/MSM.922576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nagai H, Muto M. Optimal management of immune-related adverse events resulting from treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a review and update. Int J Clin Oncol. 2018;23(3):410–420. doi: 10.1007/s10147-018-1259-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weber JS, Kähler KC, Hauschild A. Management of immune-related adverse events and kinetics of response with ipilimumab. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(21):2691–2697. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.41.6750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buti S, Bersanelli M, Perrone F, Tiseo M, Tucci M, Adamo V, et al. Effect of concomitant medications with immune-modulatory properties on the outcomes of patients with advanced cancer treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: development and validation of a novel prognostic index. Eur J Cancer. 2021;142:18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pieniążek M, Pawlak P, Radecka B. Early palliative care of non-small cell lung cancer in the context of immunotherapy. Oncol Lett. 2020;20(6):396. doi: 10.3892/ol.2020.12259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Colle R, Radzik A, Cohen R, Pellat A, Lopez-Tabada D, Cachanado M, et al. Pseudoprogression in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors for microsatellite instability-high/mismatch repair-deficient metastatic colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2021;144:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seymour L, Bogaerts J, Perrone A, Ford R, Schwartz LH, Mandrekar S, et al. RECIST working group. iRECIST: guidelines for response criteria for use in trials testing immunotherapeutics. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(3):e143-e152. Doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30074-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Myers G. Immune-related adverse events of immune checkpoint inhibitors: a brief review. Curr Oncol. 2018;25(5):342–347. doi: 10.3747/co.25.4235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cortellini A, Tucci M, Adamo V, Stucci LS, Russo A, Tanda ET. Integrated analysis of concomitant medications and oncological outcomes from PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitors in clinical practice. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8(2):e001361. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-001361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tong W, Li X. Evidence for mu opioid receptor on mouse spleen lymphocyteds. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica [online] 1999;20(9):835–838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Machelska H, Celik MÖ. Opioid receptors in immune and glial cells-implications for pain control. Front Immunol. 2020;4(11):300. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00300.PMID:32194554;PMCID:PMC7064637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Okuyama K, Ide S, Sakurada S, Sasaki K, Sora I, Tamura G, et al. μ-opioid receptor-mediated alterations of allergen-induced immune responses of bronchial lymph node cells in a murine model of stress asthma. Allergol Int. 2012;61(2):245–258. doi: 10.2332/allergolint.11-OA-0304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Börner C, Lanciotti S, Koch T, Höllt V, Kraus J. μ opioid receptor agonist-selective regulation of interleukin-4 in T lymphocytes. J Neuroimmunol. 2013;263(1–2):35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Toskulkao T, Pornchai R, Akkarapatumwong V, Vatanatunyakum S, Govitrapong P. Alteration of lymphocyte opioid receptors in methadone maintenance subjects. Neurochem Int. 2010;56(2):285–290. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2009.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maher DP, Walia D, Heller NM. Suppression of human natural killer cells by different classes of opioids. Anesth Analg. 2019;128(5):1013–1021. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maher DP, Walia D, Heller NM. Morphine decreases the function of primary human natural killer cells by both TLR4 and opioid receptor signaling. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;83:298–302. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2019.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beilin B, Shavit Y, Hart J, Mordashov B, Cohn S, Notti I, Bessler H. Effects of anesthesia based on large versus small doses of fentanyl on natural killer cell cytotoxicity in the perioperative period. Anesth Analg. 1996;82(3):492–497. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199603000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kadhim S, Bird MF, Lambert DG. N/OFQ-NOP system in peripheral and central immunomodulation. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2019;254:297–311. doi: 10.1007/164_2018_203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Acharya C, Betrapally NS, Gillevet PM, Sterling RK, Akbarali H, White MB, et al. Chronic opioid use is associated with altered gut microbiota and predicts readmissions in patients with cirrhosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45(2):319–331. doi: 10.1111/apt.13858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Banerjee S, Sindberg G, Wang F, Meng J, Sharma U, Zhang L, et al. Opioid-induced gut microbial disruption and bile dysregulation leads to gut barrier compromise and sustained systemic inflammation. Mucosal Immunol. 2016;9(6):1418–1428. doi: 10.1038/mi.2016.9.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ren M, Lotfipour S. The role of the gut microbiome in opioid use. Behav Pharmacol. 2020;31:2. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0000000000000538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Iglesias-Santamaría A. Impact of antibiotic use and other concomitant medications on the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with advanced cancer. Clin Transl Oncol. 2020;22(9):1481–1490. doi: 10.1007/s12094-019-02282-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zheng XQ, Huang JF, Lin JL, Chen L, Zhou TT, Chen D, Lin DD, Shen JF, Wu AM. Incidence, prognostic factors, and a nomogram of lung cancer with bone metastasis at initial diagnosis: a population-based study. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2019;8(4):367–379. doi: 10.21037/tlcr.2019.08.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Abdel-Rahman O. Clinical correlates and prognostic value of different metastatic sites in patients with malignant melanoma of the skin: a SEER database analysis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2018;29(2):176–181. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2017.1360987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Santoni M, Conti A, Procopio G, Porta C, Ibrahim T, Barni S, et al. Bone metastases in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: are they always associated with poor prognosis? J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2015;34(1):10. doi: 10.1186/s13046-015-0122-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.