Abstract

Background

The clinical use of patient-reported outcomes as compared to inflammatory biomarkers for predicting cancer survival remains a challenge in palliative care settings. We evaluated the role of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 15 Palliative scores (EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL) and the inflammatory biomarkers C-reactive protein (CRP), albumin (Alb), and neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) for survival prediction in patients with advanced cancer.

Methods

This was an observational study in terminally ill patients with cancer hospitalized in a palliative care unit between June 2018 and December 2019. Patients’ data collected at the time of hospitalization were analyzed. Cox regression was performed to examine significant factors influencing survival. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was performed to estimate cut-off values for predicting survival within 3 weeks, and a log-rank test was performed to compare survival curves between groups divided by the cut-off values.

Results

Totally, 130 patients participated in the study. Cox regression suggested that the QLQ-C15-PAL dyspnea and fatigue scores and levels of CRP, Alb, and NLR were significantly associated with survival time, and cut-off values were 66.67, 66.67, 3.0 mg/dL, 2.5 g/dL, and 8.2, respectively. The areas under ROC curves of these variables were 0.6–0.7. There were statistically significant differences in the survival curves between groups categorized using each of these cut-off values (p < .05 for all cases).

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that the assessment of not only objective indicators for the systemic inflammatory response but also patient-reported outcomes using EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL is beneficial for the prediction of short-term survival in terminally ill patients with cancer.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12885-021-08049-3.

Keywords: EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL, Inflammatory biomarkers, Survival prediction, Terminally ill cancer patients, Palliative care

Background

For patients with advanced cancer, the accurate prediction of survival is important for clinical and personal decision-making in the last months, weeks, and days of life. In clinical practice, the prognosis is based on various factors including symptoms and biomarker measurements [1, 2]. As the end of life approaches, the various distressing symptoms increase in severity [3], and the most significant include deterioration in performance status, dyspnea, delirium, and cancer cachexia syndrome [4, 5]. Therefore, multidimensional information about not only objective variables such as laboratory values but also subjective variables such as patients’ symptoms play an essential role in the accurate prediction of survival.

A patient-reported outcome (PRO) is a measurement based on a report from a patient without amendment or interpretation by a clinician or anyone else [6]. Some of the scales in PRO have been significantly associated with survival and identified as independent prognostic factors influencing survival in patients with advanced cancer [7–12]. However, despite previous studies supporting the added prognostic value of PROs, their systematic use during the cancer treatment and palliative care process remains unknown [11].

In palliative care settings, quality of life (QOL) is the most important outcome. One of the common instruments for assessing QOL is the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 15 Palliative Care (EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL), which is a shortened version of the EORTC Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 (QLQ-C30) [13, 14]. Lee et al. showed that the QLQ-C15-PAL can be an independent prognostic factor in inpatients with cancer near the end of life [8]. However, studies about the accuracy of prognoses estimated by QLQ-C15-PAL scores are limited. In addition, the adequate cut-off values of these scores have not been explored.

Moreover, terminally ill patients with cancer frequently experience symptoms associated with cancer cachexia, which is characterized by weight loss, muscle wasting, fatigue, and appetite loss [15, 16]. Cancer cachexia is considered a metabolic disorder driven by the systemic inflammatory response [17]. The presence of systemic inflammatory response, as evidenced by high C-reactive protein (CRP) [18, 19], low albumin (Alb) [20, 21], and high neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) [22–24], also has independent prognostic value in patients with advanced cancer. These inflammatory biomarkers have been shown to be reliable prognostic markers in cancer patients with numerous cancer sites [25]. The modified Glasgow Prognostic Score (mGPS) [26], assessing the magnitude of the systemic inflammatory response, is one of the validated prognostic tools based on objective criteria using a combination of CRP (> 1.0 mg/dL) and Alb levels (< 3.5 g/dL) [25–27]. However, a previous study reported that the prevalence of CRP ≥ 1.0 mg/dL was 79.6% in patients with advanced cancer in palliative care settings [18]. Therefore, the preferred cut-off value for terminally ill patients with cancer needs to be further investigated.

This study aimed to examine the role of QLQ-C15-PAL scores and the inflammatory biomarkers CRP, Alb, and NLR for survival prediction to help avoid discomfort and inappropriate therapies in terminally ill patients with cancer.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a prospective observational study of patients with advanced cancer hospitalized to receive palliative care in a palliative care unit from June 2018 to December 2019. The inclusion criteria were (1) consent to participate in the study and (2) the ability to complete the questionnaires. The exclusion criteria were inability to complete the questionnaires due to lack of consciousness or cognitive impairments. All participants provided verbal informed consent to use their data in the study and were followed until death or discharge during the study period. The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and the Ethical Guidelines for Epidemiology Research and was approved by the ethics committees at the hospital on May 15, 2018 and the university with which the authors were affiliated. The recruited patients in this study were the same as those included in a previously reported study [28].

Collection of data regarding clinical parameters

The study was conducted as a part of the routine practice of health care professionals in the palliative care unit. All clinical parameters were measured at the time of patients’ hospitalization in the palliative care unit. Patients’ data, including those for age, sex, primary cancer type, presence of metastatic disease, Palliative Performance Scale scores (PPS), and the inflammatory biomarkers CRP, Alb, and NLR, were collected from their electronic medical records. The NLR was defined as the absolute neutrophil count divided by the absolute lymphocyte count [29]. The mGPS was calculated as follows: mGPS = 0 (CRP ≤ 1.0 mg/dL), 1 (CRP > 1.0 mg/dL and Alb ≥3.5 g/dL), and 2 (CRP > 1.0 mg/dL and Alb < 3.5 g/dL). These cut-off values are based on those used in previous studies examining the mGPS [26].

Measurements of QOL

Patients’ QOL and clinical symptoms were assessed using the Japanese version of the EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL. Patients completed the questionnaires at the time of hospitalization in the palliative care unit. The QLQ-C15-PAL consists of 15 questions pertaining to QOL and includes 2 multi-item functional scales (physical and emotional functioning), 2 multi-item symptom scales (fatigue and pain), 5 single-item symptom scales (dyspnea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation, and nausea/vomiting), and a question regarding overall QOL (global health status). Most responses were provided using a 4-point scale (1 = “not at all,” 2 = “a little,” 3 = “quite a bit,” and 4 = “very much”), and overall QOL was rated using a scale ranging from 1 (very poor) to 7 (excellent). All 10 scales were linearly transformed according to a previous publication [13, 30]; these transformed scores ranged from 0 to 100. Higher scores indicate better health-related QOL in the functional scales and the overall QOL scale and worse symptoms in the symptom scales.

Statistical analysis

Survival time was defined as the period from the date of admission to the palliative care unit to the date of death. Patients without available information regarding survival because they left the palliative care unit or remained in the palliative unit during the study period were considered to be censored. The Cox proportional hazard model was used to evaluate the influence of QLQ-C15-PAL scores and inflammatory biomarkers on survival times. We performed a univariate regression, individually entering the 10 transformed QLQ-C15-PAL scale scores and the inflammatory biomarkers CRP, Alb, and NLR as independent variables into the Cox model. In addition, we performed a multivariate regression, including only statistically significant variables with a p value < .05 in the univariate analysis. Missing data were excluded.

The cut-off values for detecting the risk of a short-term prognosis of < 3 weeks (21 days) for the statistically significant factors according to the results of univariate Cox regression were determined via receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis for patients for whom survival times were obtained. We selected 3 weeks because this term is clinically important for decision-making in end of life care [31]. We divided patients into 2 groups based on these cut-off values, and the survival curves were drawn using the Kaplan-Meier method, with the log-rank test used to compare survival times between the 2 groups. All analyses were performed using BellCurve® for Excel Version 2.15 (Social Survey Research Information Co., Ltd.), and p values < .05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

In total, 130 (60.7%) of the 214 patients hospitalized in the palliative care unit during the study period were included in the analysis. Of the 84 excluded patients, 75 (89.3%) were unable to complete the questionnaires (33 with worsening physical health, 29 with clouding of consciousness such as somnolence, 9 with neurocognitive disorders, and 4 with anxiety neurosis). In addition, 6 patients refused to participate, and 3 patients were hospitalized for only a short time, such as 2 days. Patients’ characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Patients’ median age was 74 years, and the lung was the most common primary cancer site (n = 31, 23.8%). The total number of metastases was highest in the liver (n = 54, 41.5%), followed by the lung (n = 52, 40.0%). At the end of the study period, 109 patients were confirmed dead, and information was missing for 18 and 3 patients because they left the hospital before death and remained hospitalized, respectively. Survival times were < 3 weeks for > 50% of patients (61/109; 56.0%). Table 1 also shows the baseline QLQ-C15-PAL scores and inflammatory biomarkers at the time of hospitalization. Regarding the symptom scales, the highest median scores were observed for fatigue (66.7) and appetite loss (66.7). Most patients showed abnormally high CRP (> 1.0 mg/dL, 105/126; 83.3%), abnormally low Alb (< 3.5 g/dL, 115/126; 91.3%), and an mGPS of 2 (98/126; 77.8%), indicating that the study population showed increased inflammation.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients in the study population

| Number (%) | |

|---|---|

| Total Number of Patients | 130 |

| Age, years (median, range) | 74 (32–97) |

| Sex (Male/Female) | 71 (54.6)/59 (45.4) |

| Primary Cancer Site | |

| Lung | 31 (23.8) |

| Colon | 26 (20.0) |

| Pancreas | 12 (9.2) |

| Liver | 7 (5.4) |

| Stomach | 7 (5.4) |

| Esophagus | 5 (3.8) |

| Breast | 5 (3.8) |

| Ovary | 4 (3.1) |

| Uterine | 4 (3.1) |

| Prostate | 3 (2.3) |

| Other | 23 (17.7) |

| Unknown | 3 (2.3) |

| Metastasis (total number) | |

| Liver | 54 (41.5) |

| Lung | 52 (40.0) |

| Bone | 40 (30.8) |

| Brain | 14 (10.8) |

| PPS | |

| ≥ 70 | 20 (15.4) |

| 40–60 | 74 (56.9) |

| ≤ 30 | 29 (22.3) |

| Unknown | 7 (5.4) |

| Survival, days (median, range) n = 109 | 18 (2–193) |

| QLQ-C15-PAL (median (Q1, Q3), mean (± SD)) | |

| Physical Functioning (n = 125) | 33.3 (20.0, 46.7), 37.0 ± 25.1 |

| Emotional Functioning (n = 129) | 66.7 (41.7, 83.3), 63.2 ± 28.3 |

| Dyspnea | 33.3 (0.0, 66.7), 39.5 ± 34.4 |

| Pain (n = 129) | 50.0 (16.7, 66.7), 47.3 ± 34.0 |

| Insomnia | 33.3 (0.0, 66.7), 40.0 ± 36.0 |

| Appetite Loss | 66.7 (33.3, 100), 57.7 ± 38.4 |

| Constipation (n = 128) | 33.3 (0.0, 66.7), 37.0 ± 35.3 |

| Fatigue (n = 129) | 66.7 (44.4, 100), 63.8 ± 29.7 |

| Nausea/Vomiting | 0.0 (0.0, 16.7), 18.7 ± 29.6 |

| QOL (n = 124) | 50.0 (16.7, 50.0), 38.7 ± 27.1 |

| Inflammatory Biomarkers (median, range) n = 126 | |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 3.9 (< 0.1–32.1) |

| Alb (g/dL) | 2.6 (1.2–3.9) |

| NLR (n = 122) | 7.6 (0.6–187) |

Alb albumin, CRP C-reactive protein, NLR neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio, PPS Palliative Performance Scale, QLQ-C15-PAL European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 15 Palliative Care, QOL quality of life

In the QLQ-C15-PAL, patients rated their symptoms using a 4-point scale (1 = not at all, 2 = a little, 3 = quite a bit, 4 = very much) for two functional domains and 7 symptom domains, and a 7-point scale (range: 1 = very poor to 7 = excellent) for overall QOL. All scale scores were linearly transformed, and the resultant scores ranged from 0 to 100. Q1: first quarter (25% quartile), Q3: third quarter (75% quartile), SD: standard deviation

Table 2 shows the results of the Cox proportional hazard model analysis of the dependence of survival times on QLQ-C15-PAL scores and inflammatory biomarkers. In the univariate analysis, statistically significant predictors of survival were the QLQ-C15-PAL dyspnea and fatigue scores and levels of the inflammatory biomarkers CRP, Alb, and NLR. Among the QLQ-C15-PAL scales, higher scores of dyspnea (hazard ratio, HR = 1.010) and fatigue (HR = 1.011) were significantly associated with shorter survival. Additionally, higher CRP (HR = 1.050) and NLR (HR = 1.017) or lower Alb (HR = 0.628) were significantly associated with shorter survival. A multivariate analysis showed that the dyspnea and fatigue scores and Alb and NLR levels were significantly related to survival.

Table 2.

Results of Cox proportional hazard model analysis of survival data

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis (n = 112) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| variables | n | estimates | S.E. | HR | 95% CI | p | estimates | S.E. | HR | 95% CI | p |

| QLQ-C15-PAL | |||||||||||

| Physical Functioning | 125 | −0.001 | 0.004 | 0.999 | 0.991–1.006 | .738 | |||||

| Emotional Functioning | 129 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 1.001 | 0.994–1.008 | .809 | |||||

| Dyspnea | 130 | 0.010 | 0.003 | 1.010 | 1.005–1.016 | < .001** | 0.012 | 0.003 | 1.012 | 1.005–1.019 | < .001** |

| Pain | 129 | −0.0004 | 0.003 | 1.000 | 0.994–1.005 | .878 | |||||

| Insomnia | 130 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 1.001 | 0.996–1.006 | .608 | |||||

| Appetite Loss | 130 | 0.005 | 0.003 | 1.005 | 1.000–1.010 | .073 | |||||

| Constipation | 128 | 0.0003 | 0.003 | 1.000 | 0.995–1.006 | .922 | |||||

| Fatigue | 129 | 0.011 | 0.003 | 1.011 | 1.004–1.017 | .002** | 0.009 | 0.004 | 1.009 | 1.001–1.016 | .024* |

| Nausea/Vomiting | 130 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 1.002 | 0.995–1.008 | .597 | |||||

| QOL | 124 | −0.007 | 0.004 | 0.993 | 0.986–1.000 | .055 | |||||

| Inflammatory Biomarkers | |||||||||||

| CRP | 126 | 0.049 | 0.014 | 1.050 | 1.022–1.079 | < .001** | |||||

| Alb | 126 | −0.465 | 0.171 | 0.628 | 0.449–0.878 | .007** | −0.457 | 0.180 | 0.633 | 0.445–0.902 | .011* |

| NLR | 122 | 0.017 | 0.003 | 1.017 | 1.012–1.023 | < .001** | 0.015 | 0.003 | 1.015 | 1.009–1.021 | < .001** |

*p < .05, **p < .01; estimates = regression coefficients, S.E.: Standard errors of estimates; all QLQ-C15-PAL scale scores were linearly transformed, and the resultant scores ranged from 0 to 100. Alb albumin, CI confidence interval, CRP C-reactive protein, HR hazard ratio, NLR neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio, QLQ-C15-PAL European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 15 Palliative Care, QOL quality of life

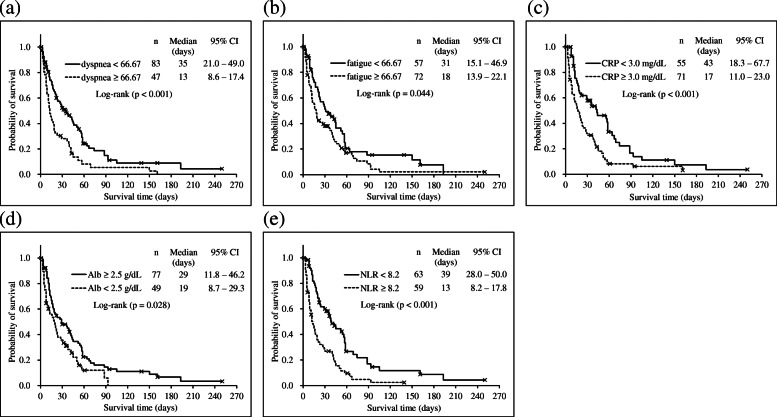

Results of the ROC analysis of the statistically significant variables to detect prognostic risk of < 3 weeks are summarized in Table 3. The cut-off values were estimated at 66.67 (dyspnea), 66.67 (fatigue), 3.0 mg/dL (CRP), 2.5 g/dL (Alb), and 8.2 (NLR). A transformed score of > 66.67 corresponds to the sum of raw scores (Q7 and Q11) of > 6 for fatigue and > 3 for dyspnea. The areas under ROC curves (AUCs) were 0.6–0.7 and statistically significant in all of those indicators except for Alb (p = .06), and both sensitivity and specificity were 0.5–0.7. Figure 1 shows the Kaplan-Meier curves of these indicators for the groups categorized using each of the cut-off values, and the log-rank test indicated significant differences between groups (p < .05 for all cases).

Table 3.

Cut-off values of each indicator for detecting risk of a prognosis of < 3 weeks

| Indicators | n a | Cut-off | Sensitivity | Specificity | AUC | 95% CI | p b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dyspnea | 109 | 66.67 | 0.508 | 0.729 | 0.661 | 0.560–0.761 | .002** |

| Fatigue | 108 | 66.67 | 0.683 | 0.542 | 0.691 | 0.593–0.789 | < .001** |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 106 | 3.0 | 0.678 | 0.489 | 0.612 | 0.504–0.720 | .043* |

| Alb (g/dL) | 106 | 2.5 | 0.593 | 0.638 | 0.604 | 0.496–0.713 | .060 |

| NLR | 102 | 8.2 | 0.667 | 0.644 | 0.699 | 0.598–0.801 | < .001** |

*p < .05, **p < .01; aNumber of patients whose survival time data were available. bp value derived according to the receiver operating characteristic curve analysis. All QLQ-C15-PAL scale scores were linearly transformed, and the resultant scores ranged from 0 to 100. Alb albumin, AUC area under the curve, CI confidence interval, CRP C-reactive protein, NLR neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio, QLQ-C15-PAL European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 15 Palliative Care

Fig. 1.

Survival curves of the categorized groups according to the cut-off values for a dyspnea and b fatigue QLQ-C15-PAL scores, c C-reactive protein (CRP), d albumin (Alb), e neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR). The inserted numbers represent the number of patients (n), median of the survival day in each group, and a 95% confidence interval (CI)

Discussion

We performed an observational study to examine the role of QLQ-C15-PAL scores and the inflammatory biomarkers CRP, Alb, and NLR for survival prediction in terminally ill patients with cancer hospitalized in a palliative care unit. Our study identified that dyspnea and fatigue symptom scores in the QLQ-C15-PAL and all inflammatory biomarkers could be independent prognostic factors of short-term survival for terminally ill patients with cancer. We further revealed the cut-off values for each of the dyspnea and fatigue symptom scores for predicting prognosis.

Although previous studies [7, 9, 10] have reported that several scores in the QLQ-C30 were associated with survival, there are few reports regarding the QLQ-C15-PAL. Lee et al. [8] reported that multiple QLQ-C15-PAL scores can be independent prognostic factors of survival in patients with far advanced cancer; however, our results indicate only dyspnea and fatigue symptoms as the independent prognostic factors in QLQ-C15-PAL scores. Our study included patients with terminally ill cancer, many of whom had low PPS (≤ 60, 103/130; 79.2%) and short survival times of 18 days (median). These results suggest that the dyspnea and fatigue symptoms among QLQ-C15-PAL scores are independent prognostic factors, particularly in terminally ill patients with cancer.

Many previous studies have identified PROs as prognostic factors for survival of patients with cancer [7–11], but few have examined the cut-off values for PRO measurements to predict survival. Therefore, we examined the cut-off values of dyspnea and fatigue in the QLQ-C15-PAL for detecting the risk of a short-term prognosis of < 3 weeks (21 days). Both dyspnea and fatigue showed cut-off values of 66.67 (transformed QLQ-C15-PAL scores). However, severe fatigue was indicated with transformed QLQ-C30 scores of ≥66.67 in a previous study [32]. Meanwhile, in our study, more than 50% of patients showed severe fatigue according to the QLQ-C15-PAL scores. These results suggest that the cut-off values of transformed QLQ-C15-PAL scores, which can lead to severe levels of dyspnea and fatigue symptoms experienced by many terminally ill patients, are a predictive indicator of short-term prognosis.

The levels of CRP, Alb, and NLR are known prognostic indicators for patients with cancer [18–24], which was confirmed in the Cox analysis (Table 2). We also identified cut-off values for these markers to predict 3-week survival (Table 3). Considering the criteria for an mGPS of 2 (CRP > 1.0 mg/dL and Alb < 3.5 g/dL), our results indicate that a high cut-off value for CRP (3.0 mg/dL) and a low cut-off value for Alb (2.5 g/dL) are estimates from advanced cancer patients near the end of life. Additionally, approximately 80% of patients had a CRP > 1.0 mg/dL, and over 70% had an mGPS of 2 in our study. This is consistent with previous reports in palliative care settings [18, 33]; therefore, terminally ill cancer patients might be at greater risk for chronic inflammation. Moreover, in cancer cachexia, inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6 derived from cancer cells, act on hepatocytes to increase CRP production and increase protein catabolism [17]. The level of Alb, reflecting the visceral protein pool [34], is reduced in the presence of a systemic inflammatory response [34, 35].

NLRs have been reported as inflammatory biomarkers, based on neutrophil and lymphocyte counts [29]. A systematic review indicated that an NLR score of 4 was the best cut-off value for prognosis [24]. On the other hand, our study revealed that the cut-off value for the NLR was 8.2, and most patients had abnormally high NLR scores (> 4, 98/122; 80.3%). This is a similar finding to a previous study that reported scores of 9.21 in cancer patients who died within 4 weeks [23]. These findings also suggest increased inflammation in terminally ill patients with cancer. Although there are many biomarkers that can be influenced by systemic inflammatory responses, in our study, we chose only CRP, Alb, and NLR measurements because of strong evidence for their association with prognoses. In addition, it was impossible to measure all biomarkers related to inflammation. Therefore, we adopted the results of a univariate analysis and calculated cut-off values of each indicator. The current results suggest that the assessment of the systemic inflammatory response using these biomarkers is also useful in estimating prognoses for terminally ill patients with cancer.

Among the significant prognostic indicators, the sensitivity and specificity of patient-reported dyspnea and fatigue were comparable to that of the inflammatory biomarkers CRP, Alb, and NLR (Table 3). The measurements of PROs can be assessed directly by the patient themselves, even if no patients’ blood data were available. Near the end of life, the clinical prediction of survival requires simple, always-available prognostic indicators because the patient’s general condition rapidly deteriorates in the last month before death [3]. Therefore, the PRO score might be a more suitable prognostic indicator for short-term prognosis of 3 weeks as compared to laboratory values. The results of the present study suggest that monitoring QLQ-C15-PAL scores is necessary, along with measuring inflammatory biomarkers, in terminally ill patients with cancer.

This study had some limitations. First, it was conducted in a single hospital, and the sample size was not large enough to ensure generalizability. Second, we could not evaluate the details of various factors that could affect inflammation status, such as use of concomitant drugs like anti-inflammatory medication, nutritional intake, cancer type, and coexisting infections. Third, we could not evaluate the confounding factors likely to be associated with survival such as classification of cancer cachexia, cancer stage, age, other comorbidities. Finally, patients who were unable to answer the questionnaire were excluded, and thus, our finding might be different in patients with cognitive impairments or lacking consciousness.

Conclusion

We examined the survival predictability of QLQ-C15-PAL scores and inflammatory biomarkers in terminally ill patients with cancer and found that the QLQ-C15-PAL dyspnea and fatigue scores could be independent prognostic indicators comparable to the inflammatory biomarkers CRP, Alb, and NLR. The findings suggest that the assessment of not only objective indicators for the systemic inflammatory response but also PROs is useful for the prediction of short-term survival in terminally ill patients with cancer.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank patients participated in this study and palliative care nurses at the Palliative Care Unit, Higashisumiyoshi-Morimoto Hospital.

Abbreviations

- EORTC

European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer

- QLQ-C15-PAL

Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 15 Palliative

- CRP

C-Reactive Protein

- Alb

Albumin

- NLR

Neutrophil-Lymphocyte Ratio

- ROC

Receiver Operating Characteristic

- PRO

Patient-Reported Outcome

- QOL

Quality of Life

- QLQ-C30

Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30

- mGPS

modified Glasgow Prognostic Score

- PPS

Palliative Performance Scale

- HR

Hazard Ratio

- AUC

Areas Under ROC Curve

Authors’ contributions

All authors participated in the planning of the study design. In detail, NK, CM and YS conceptually designed the study and wrote the draft manuscript. KO who is a medical doctor, MS, HK, TN who are pharmacists and YE who is a nurse collected the relevant data during their routine work and followed up the patients. YY performed statistical analysis and interpretation of the data. All gave the final approval of the version to be published.

Funding

This work was partly supported by a KAKENHI Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) (No. 19 K10546) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. The funding body had no roles in this study.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the ethics committees at Tachibana Medical Corporation Higashisumiyoshi-Morimoto Hospital (approved on May 15, 2018) and Kyoto Pharmaceutical University (No.19–18-02) with which the authors are affiliated. The present study was a prospective observational study as part of daily practice without intervention at the treatment, therefore researchers are not necessarily required to receive written informed consent. However, a written form describing the objectives and methods of this study approved by the ethics committees was explained all study participants to obtain verbal consent and we prepared a record of the informed consent received.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Nanako Koyama, Email: kd17004@ms.kyoto-phu.ac.jp.

Chikako Matsumura, Email: chika-matsumura@mb.kyoto-phu.ac.jp.

Yoshihiro Shitashimizu, Email: ky15158@ms.kyoto-phu.ac.jp.

Morito Sako, Email: moritosako@yahoo.co.jp.

Hideo Kurosawa, Email: kurosawa_hp@yahoo.co.jp.

Takehisa Nomura, Email: tnomura.jni@gmail.com.

Yuki Eguchi, Email: mori_kanwa@yahoo.co.jp.

Kazuki Ohba, Email: m1280484@msic.med.osaka-cu.ac.jp.

Yoshitaka Yano, Email: yano@mb.kyoto-phu.ac.jp.

References

- 1.Glare PA, Sinclair CT. Palliative medicine review: prognostication. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(1):84–103. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.9992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hui D, Paiva CE, Del Fabbro EG, Steer C, Naberhuis J, van de Wetering M, et al. Prognostication in advanced cancer: update and directions for future research. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(6):1973–1984. doi: 10.1007/s00520-019-04727-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seow H, Barbera L, Sutradhar R, Howell D, Dudgeon D, Atzema C, Liu Y, Husain A, Sussman J, Earle C. Trajectory of performance status and symptom scores for patients with cancer during the last six months of life. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(9):1151–1158. doi: 10.1200/jco.2010.30.7173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maltoni M, Caraceni A, Brunelli C, Broeckaert B, Christakis N, Eychmueller S, Glare P, Nabal M, Viganò A, Larkin P, de Conno F, Hanks G, Kaasa S, Steering Committee of the European Association for Palliative Care Prognostic factors in advanced cancer patients: evidence-based clinical recommendations--a study by the steering Committee of the European Association for palliative care. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(25):6240–6248. doi: 10.1200/jco.2005.06.866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trajkovic-Vidakovic M, de Graeff A, Voest EE, Teunissen SC. Symptoms tell it all: a systematic review of the value of symptom assessment to predict survival in advanced cancer patients. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2012;84(1):130–148. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2012.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.US Department of Health and Human Services. Guidance for industry. Patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM193282.pdf. Accessed 5 Aug 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Quinten C, Martinelli F, Coens C, Sprangers MAG, Ringash J, Gotay C, Bjordal K, Greimel E, Reeve BB, Maringwa J, Ediebah DE, Zikos E, King MT, Osoba D, Taphoorn MJ, Flechtner H, Schmucker-von Koch J, Weis J, Bottomley A, on behalf of Patient Reported Outcomes and Behavioral Evidence (PROBE) and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Clinical Groups A global analysis of multitrial data investigating quality of life and symptoms as prognostic factors for survival in different tumor sites. Cancer. 2014;120(2):302–311. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee YJ, Suh SY, Choi YS, Shim JY, Seo AR, Choi SE, Ahn HY, Yim E. EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL quality of life score as a prognostic indicator of survival in patients with far advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22(7):1941–1948. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2173-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quinten C, Coens C, Mauer M, Comte S, Sprangers MAG, Cleeland C, Osoba D, Bjordal K, Bottomley A, EORTC Clinical Groups Baseline quality of life as a prognostic indicator of survival: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from EORTC clinical trials. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(9):865–871. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(09)70200-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braun DP, Gupta D, Staren ED. Predicting survival in prostate cancer: the role of quality of life assessment. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20(6):1267–1274. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1213-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mierzynska J, Piccinin C, Pe M, Martinelli F, Gotay C, Coens C, Mauer M, Eggermont A, Groenvold M, Bjordal K, Reijneveld J, Velikova G, Bottomley A. Prognostic value of patient-reported outcomes from international randomised clinical trials on cancer: a systematic review. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(12):e685–e698. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30656-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Batra A, Yang L, Boyne DJ, Harper A, Cheung WY, Cuthbert CA. Associations between baseline symptom burden as assessed by patient-reported outcomes and overall survival of patients with metastatic cancer. Support Care Cancer. Published online July 16. 2020;(3):1423–31. 10.1007/s00520-020-05623-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Groenvold M, Petersen MA, Aaronson NK, Arraras JI, Blazeby JM, Bottomley A, Fayers PM, de Graeff A, Hammerlid E, Kaasa S, Sprangers MAG, Bjorner JB. EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL: the new standard in the assessment of health-related quality of life in advanced cancer? Palliat Med. 2006;20(2):59–61. doi: 10.1191/0269216306pm1133xx. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miyashita M, Wada M, Morita T, Ishida M, Onishi H, Sasaki Y, Narabayashi M, Wada T, Matsubara M, Takigawa C, Shinjo T, Suga A, Inoue S, Ikenaga M, Kohara H, Tsuneto S, Shima Y. Independent validation of the Japanese version of the EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL for patients with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2015;49(5):953–959. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.11.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fearon K, Strasser F, Anker SD, Bosaeus I, Bruera E, Fainsinger RL, Jatoi A, Loprinzi C, MacDonald N, Mantovani G, Davis M, Muscaritoli M, Ottery F, Radbruch L, Ravasco P, Walsh D, Wilcock A, Kaasa S, Baracos VE. Definition and classification of cancer cachexia: an international consensus. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(5):489–495. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(10)70218-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mondello P, Mian M, Aloisi C, Famà F, Mondello S, Pitini V. Cancer cachexia syndrome: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and new therapeutic options. Nutr Cancer. 2015;67(1):12–26. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2015.976318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aoyagi T, Terracina KP, Raza A, Matsubara H, Takabe K. Cancer cachexia, mechanism and treatment. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2015;7(4):17–29. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v7.i4.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amano K, Maeda I, Morita T, Miura T, Inoue S, Ikenaga M, Matsumoto Y, Baba M, Sekine R, Yamaguchi T, Hirohashi T, Tajima T, Tatara R, Watanabe H, Otani H, Takigawa C, Matsuda Y, Nagaoka H, Mori M, Kinoshita H. Clinical implications of C-reactive protein as a prognostic marker in advanced cancer patients in palliative care settings. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2016;51(5):860–867. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahmoud FA, Rivera NI. The role of C-reactive protein as a prognostic indicator in advanced cancer. Curr Oncol Rep. 2002;4(3):250–255. doi: 10.1007/s11912-002-0023-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Asher V, Lee J, Bali A. Preoperative serum albumin is an independent prognostic predictor of survival in ovarian cancer. Med Oncol. 2012;29(3):2005–2009. doi: 10.1007/s12032-011-0019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feliu J, Jiménez-Gordo AM, Madero R, Rodríguez-Aizcorbe JR, Espinosa E, Castro J, Acedo JD, Martínez B, Alonso-Babarro A, Molina R, Cámara JC, García-Paredes ML, González-Barón M. Development and validation of a prognostic nomogram for terminally ill cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(21):1613–1620. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang LX, Wei ZJ, Xu AM, Zang JH. Can the neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-lymphocyte ratio be beneficial in predicting lymph node metastasis and promising prognostic markers of gastric cancer patients? Tumor maker retrospective study. Int J Surg. 2018;56:320–327. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakamura Y, Watanabe R, Katagiri M, Saida Y, Katada N, Watanabe M, Okamoto Y, Asai K, Enomoto T, Kiribayashi T, Kusachi S. Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio has a prognostic value for patients with terminal cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2016;14(1):148. 10.1186/s12957-016-0904-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Templeton AJ, McNamara MG, Šeruga B, Vera-Badillo FE, Aneja P, Ocaña A, et al. Prognostic role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in solid tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(6):dju124. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dolan RD, McSorley ST, Horgan PG, Laird B, McMillan DC. The role of the systemic inflammatory response in predicting outcomes in patients with advanced inoperable cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2017;116:134–146. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McMillan DC. The systemic inflammation-based Glasgow prognostic score: a decade of experience in patients with cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2013;39(5):534–540. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Proctor MJ, Morrison DS, Talwar D, Balmer SM, O’Reilly DSJ, Foulis AK, et al. An inflammation-based prognostic score (mGPS) predicts cancer survival independent of tumour site: a Glasgow inflammation outcome study. Br J Cancer. 2011;104(4):726–734. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6606087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsumura C, Koyama N, Sako M, Kurosawa H, Nomura T, Eguchi Y, Ohba K, Yano Y. Comparison of patient self-reported quality of life and health care professional-assessed symptoms in terminally ill patients with cancer. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. Published online July 24. 2020;(3):283–90. 10.1177/1049909120944157. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Guthrie GJ, Charles KA, Roxburgh CS, Horgan PG, McMillan DC, Clarke SJ. The systemic inflammation-based neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio: experience in patients with cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013;88(1):218–230. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Groenvold M, Petersen MA, Aaronson NK, Arraras JI, Blazeby JM, Bottomley A, Fayers PM, de Graeff A, Hammerlid E, Kaasa S, Sprangers MA, Bjorner JB, EORTC Quality of Life Group The development of the EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL: a shortened questionnaire for cancer patients in palliative care. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42(1):55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morita T, Tsunoda J, Inoue S, Chihara S. The palliative prognostic index: a scoring system for survival prediction of terminally ill cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 1999;7(3):128–133. doi: 10.1007/s005200050242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Minton O, Strasser F, Radbruch L, Stone P. Identification of factors associated with fatigue in advanced cancer: a subset analysis of the European palliative care research collaborative computerized symptom assessment data set. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2012;43(2):226–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miura T, Matsumoto Y, Hama T, Amano K, Tei Y, Kikuchi A, Suga A, Hisanaga T, Ishihara T, Abe M, Kaneishi K, Kawagoe S, Kuriyama T, Maeda T, Mori I, Nakajima N, Nishi T, Sakurai H, Morita T, Kinoshita H. Glasgow prognostic score predicts prognosis for cancer patients in palliative settings: a subanalysis of the Japan-prognostic assessment tools validation (J-ProVal) study. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(11):3149–3156. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2693-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Keller U. Nutritional laboratory markers in malnutrition. J Clin Med. 2019;8(6):775. doi: 10.3390/jcm8060775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cabrerizo S, Cuadras D, Gomez-Busto F, Artaza-Artabe I, Marín-Ciancas F, Malafarina V. Serum albumin and health in older people: review and meta analysis. Maturitas. 2015;81(1):17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.